User login

Urinary Metals Linked to Increased Dementia Risk

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This multicenter prospective cohort study included 6303 participants from six US study centers from 2000 to 2002, with follow-up through 2018.

- Participants were aged 45-84 years (median age at baseline, 60 years; 52% women) and were free of diagnosed cardiovascular disease.

- Researchers measured urinary levels of arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, copper, lead, manganese, tungsten, uranium, and zinc.

- Neuropsychological assessments included the Digit Symbol Coding, Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument, and Digit Span tests.

- The median follow-up duration was 11.7 years for participants with dementia and 16.8 years for those without; 559 cases of dementia were identified during the study.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower Digit Symbol Coding scores were associated with higher urinary concentrations of arsenic (mean difference [MD] in score per interquartile range [IQR] increase, –0.03), cobalt (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), copper (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), uranium (MD per IQR increase, –0.04), and zinc (MD per IQR increase, –0.03).

- Effects for cobalt, uranium, and zinc were stronger in apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele (APOE4) carriers vs noncarriers.

- Higher urinary levels of copper were associated with lower Digit Span scores (MD, –0.043) and elevated levels of copper (MD, –0.028) and zinc (MD, –0.024) were associated with lower global cognitive scores.

- Individuals with urinary levels of the nine-metal mixture at the 95th percentile had a 71% higher risk for dementia compared to those with levels at the 25th percentile, with the risk more pronounced in APOE4 carriers than in noncarriers (MD, –0.30 vs –0.10, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“We found an inverse association of essential and nonessential metals in urine, both individually and as a mixture, with the speed of mental operations, as well as a positive association of urinary metal levels with dementia risk. As metal exposure and levels in the body are modifiable, these findings could inform early screening and precision interventions for dementia prevention based on individuals’ metal exposure and genetic profiles,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arce Domingo-Relloso, PhD, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York City. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data may have been missed for patients with dementia who were never hospitalized, died, or were lost to follow-up. The dementia diagnosis included nonspecific International Classification of Diseases codes, potentially leading to false-positive reports. In addition, the sample size was not sufficient to evaluate the associations between metal exposure and cognitive test scores for carriers of two APOE4 alleles.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Several authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and consulting fees, editorial stipends, teaching fees, or unrelated grant funding from various sources, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This multicenter prospective cohort study included 6303 participants from six US study centers from 2000 to 2002, with follow-up through 2018.

- Participants were aged 45-84 years (median age at baseline, 60 years; 52% women) and were free of diagnosed cardiovascular disease.

- Researchers measured urinary levels of arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, copper, lead, manganese, tungsten, uranium, and zinc.

- Neuropsychological assessments included the Digit Symbol Coding, Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument, and Digit Span tests.

- The median follow-up duration was 11.7 years for participants with dementia and 16.8 years for those without; 559 cases of dementia were identified during the study.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower Digit Symbol Coding scores were associated with higher urinary concentrations of arsenic (mean difference [MD] in score per interquartile range [IQR] increase, –0.03), cobalt (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), copper (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), uranium (MD per IQR increase, –0.04), and zinc (MD per IQR increase, –0.03).

- Effects for cobalt, uranium, and zinc were stronger in apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele (APOE4) carriers vs noncarriers.

- Higher urinary levels of copper were associated with lower Digit Span scores (MD, –0.043) and elevated levels of copper (MD, –0.028) and zinc (MD, –0.024) were associated with lower global cognitive scores.

- Individuals with urinary levels of the nine-metal mixture at the 95th percentile had a 71% higher risk for dementia compared to those with levels at the 25th percentile, with the risk more pronounced in APOE4 carriers than in noncarriers (MD, –0.30 vs –0.10, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“We found an inverse association of essential and nonessential metals in urine, both individually and as a mixture, with the speed of mental operations, as well as a positive association of urinary metal levels with dementia risk. As metal exposure and levels in the body are modifiable, these findings could inform early screening and precision interventions for dementia prevention based on individuals’ metal exposure and genetic profiles,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arce Domingo-Relloso, PhD, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York City. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data may have been missed for patients with dementia who were never hospitalized, died, or were lost to follow-up. The dementia diagnosis included nonspecific International Classification of Diseases codes, potentially leading to false-positive reports. In addition, the sample size was not sufficient to evaluate the associations between metal exposure and cognitive test scores for carriers of two APOE4 alleles.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Several authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and consulting fees, editorial stipends, teaching fees, or unrelated grant funding from various sources, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This multicenter prospective cohort study included 6303 participants from six US study centers from 2000 to 2002, with follow-up through 2018.

- Participants were aged 45-84 years (median age at baseline, 60 years; 52% women) and were free of diagnosed cardiovascular disease.

- Researchers measured urinary levels of arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, copper, lead, manganese, tungsten, uranium, and zinc.

- Neuropsychological assessments included the Digit Symbol Coding, Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument, and Digit Span tests.

- The median follow-up duration was 11.7 years for participants with dementia and 16.8 years for those without; 559 cases of dementia were identified during the study.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower Digit Symbol Coding scores were associated with higher urinary concentrations of arsenic (mean difference [MD] in score per interquartile range [IQR] increase, –0.03), cobalt (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), copper (MD per IQR increase, –0.05), uranium (MD per IQR increase, –0.04), and zinc (MD per IQR increase, –0.03).

- Effects for cobalt, uranium, and zinc were stronger in apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele (APOE4) carriers vs noncarriers.

- Higher urinary levels of copper were associated with lower Digit Span scores (MD, –0.043) and elevated levels of copper (MD, –0.028) and zinc (MD, –0.024) were associated with lower global cognitive scores.

- Individuals with urinary levels of the nine-metal mixture at the 95th percentile had a 71% higher risk for dementia compared to those with levels at the 25th percentile, with the risk more pronounced in APOE4 carriers than in noncarriers (MD, –0.30 vs –0.10, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“We found an inverse association of essential and nonessential metals in urine, both individually and as a mixture, with the speed of mental operations, as well as a positive association of urinary metal levels with dementia risk. As metal exposure and levels in the body are modifiable, these findings could inform early screening and precision interventions for dementia prevention based on individuals’ metal exposure and genetic profiles,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arce Domingo-Relloso, PhD, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York City. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data may have been missed for patients with dementia who were never hospitalized, died, or were lost to follow-up. The dementia diagnosis included nonspecific International Classification of Diseases codes, potentially leading to false-positive reports. In addition, the sample size was not sufficient to evaluate the associations between metal exposure and cognitive test scores for carriers of two APOE4 alleles.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Several authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and consulting fees, editorial stipends, teaching fees, or unrelated grant funding from various sources, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity Drug Zepbound Approved for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the obesity treatment tirzepatide (Zepbound, Eli Lilly) for treating moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults with obesity.

The new indication is for use in combination with reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. The once-weekly injectable is the first-ever drug treatment for OSA.

“Today’s approval marks the first drug treatment option for certain patients with obstructive sleep apnea,” said Sally Seymour, MD, director of the Division of Pulmonology, Allergy, and Critical Care in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This is a major step forward for patients with obstructive sleep apnea.”

Excess weight is a major risk factor for OSA, in which the upper airways become blocked multiple times during sleep and obstruct breathing. The condition causes loud snoring, recurrent awakenings, and daytime sleepiness. It is also associated with cardiovascular disease.

Tirzepatide, a dual glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist, was initially approved with brand name Mounjaro in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and as Zepbound for weight loss in November 2023.

The new OSA approval was based on two phase 3, double-blind randomized controlled trials, SURMOUNT-OSA, in patients with obesity and moderate to severe OSA, conducted at 60 sites in nine countries. Results from both were presented in June 2024 at the annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association and were simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The first trial enrolled 469 participants who were unable or unwilling to use PAP therapy, while the second included 234 who had been using PAP for at least 3 months and planned to continue during the trial. In both, the participants randomly received either 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide or placebo once weekly for 52 weeks.

At baseline, 65%-70% of participants had severe OSA, with more than 30 events/h on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and a mean of 51.5 events/h. By 52 weeks, those randomized to tirzepatide had 27-30 fewer events/h, compared with 4-6 fewer events/h for those taking placebo. In addition, significantly more of those on tirzepatide achieved OSA remission or severity reduction to mild.

Those randomized to tirzepatide also averaged up to 20% weight loss, significantly more than with placebo. “The improvement in AHI in participants with OSA is likely related to body weight reduction with Zepbound,” according to an FDA statement.

Side effects of tirzepatide include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal discomfort and pain, injection site reactions, fatigue, hypersensitivity reactions (typically fever and rash), burping, hair loss, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In an editorial accompanying The New England Journal of Medicine publication of the SURMOUNT-OSA results, Sanjay R. Patel, MD, wrote: “The potential incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment algorithms for obstructive sleep apnea should include consideration of the challenges of adherence to treatment and the imperative to address racial disparities in medical care.”

Patel, who is professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, and medical director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Comprehensive Sleep Disorders program, pointed out that suboptimal adherence to continuous PAP therapy has been a major limitation, but that adherence to the GLP-1 drug class has also been suboptimal.

“Although adherence to tirzepatide therapy in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was high, real-world evidence suggests that nearly 50% of patients who begin treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist for obesity discontinue therapy within 12 months. Thus, it is likely that any incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment pathways for obstructive sleep apnea will not diminish the importance of long-term strategies to optimize adherence to treatment.”

Moreover, Patel noted, “racial disparities in the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists among patients with diabetes arouse concern that the addition of tirzepatide as a treatment option for obstructive sleep apnea without directly addressing policies relative to coverage of care will only further exacerbate already pervasive disparities in clinical care for obstructive sleep apnea.”

Patel reported consulting for Apnimed, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Lilly USA, NovaResp Technologies, Philips Respironics, and Powell Mansfield. He is a fiduciary officer of BreathPA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the obesity treatment tirzepatide (Zepbound, Eli Lilly) for treating moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults with obesity.

The new indication is for use in combination with reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. The once-weekly injectable is the first-ever drug treatment for OSA.

“Today’s approval marks the first drug treatment option for certain patients with obstructive sleep apnea,” said Sally Seymour, MD, director of the Division of Pulmonology, Allergy, and Critical Care in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This is a major step forward for patients with obstructive sleep apnea.”

Excess weight is a major risk factor for OSA, in which the upper airways become blocked multiple times during sleep and obstruct breathing. The condition causes loud snoring, recurrent awakenings, and daytime sleepiness. It is also associated with cardiovascular disease.

Tirzepatide, a dual glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist, was initially approved with brand name Mounjaro in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and as Zepbound for weight loss in November 2023.

The new OSA approval was based on two phase 3, double-blind randomized controlled trials, SURMOUNT-OSA, in patients with obesity and moderate to severe OSA, conducted at 60 sites in nine countries. Results from both were presented in June 2024 at the annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association and were simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The first trial enrolled 469 participants who were unable or unwilling to use PAP therapy, while the second included 234 who had been using PAP for at least 3 months and planned to continue during the trial. In both, the participants randomly received either 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide or placebo once weekly for 52 weeks.

At baseline, 65%-70% of participants had severe OSA, with more than 30 events/h on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and a mean of 51.5 events/h. By 52 weeks, those randomized to tirzepatide had 27-30 fewer events/h, compared with 4-6 fewer events/h for those taking placebo. In addition, significantly more of those on tirzepatide achieved OSA remission or severity reduction to mild.

Those randomized to tirzepatide also averaged up to 20% weight loss, significantly more than with placebo. “The improvement in AHI in participants with OSA is likely related to body weight reduction with Zepbound,” according to an FDA statement.

Side effects of tirzepatide include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal discomfort and pain, injection site reactions, fatigue, hypersensitivity reactions (typically fever and rash), burping, hair loss, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In an editorial accompanying The New England Journal of Medicine publication of the SURMOUNT-OSA results, Sanjay R. Patel, MD, wrote: “The potential incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment algorithms for obstructive sleep apnea should include consideration of the challenges of adherence to treatment and the imperative to address racial disparities in medical care.”

Patel, who is professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, and medical director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Comprehensive Sleep Disorders program, pointed out that suboptimal adherence to continuous PAP therapy has been a major limitation, but that adherence to the GLP-1 drug class has also been suboptimal.

“Although adherence to tirzepatide therapy in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was high, real-world evidence suggests that nearly 50% of patients who begin treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist for obesity discontinue therapy within 12 months. Thus, it is likely that any incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment pathways for obstructive sleep apnea will not diminish the importance of long-term strategies to optimize adherence to treatment.”

Moreover, Patel noted, “racial disparities in the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists among patients with diabetes arouse concern that the addition of tirzepatide as a treatment option for obstructive sleep apnea without directly addressing policies relative to coverage of care will only further exacerbate already pervasive disparities in clinical care for obstructive sleep apnea.”

Patel reported consulting for Apnimed, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Lilly USA, NovaResp Technologies, Philips Respironics, and Powell Mansfield. He is a fiduciary officer of BreathPA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the obesity treatment tirzepatide (Zepbound, Eli Lilly) for treating moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults with obesity.

The new indication is for use in combination with reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. The once-weekly injectable is the first-ever drug treatment for OSA.

“Today’s approval marks the first drug treatment option for certain patients with obstructive sleep apnea,” said Sally Seymour, MD, director of the Division of Pulmonology, Allergy, and Critical Care in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “This is a major step forward for patients with obstructive sleep apnea.”

Excess weight is a major risk factor for OSA, in which the upper airways become blocked multiple times during sleep and obstruct breathing. The condition causes loud snoring, recurrent awakenings, and daytime sleepiness. It is also associated with cardiovascular disease.

Tirzepatide, a dual glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist, was initially approved with brand name Mounjaro in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and as Zepbound for weight loss in November 2023.

The new OSA approval was based on two phase 3, double-blind randomized controlled trials, SURMOUNT-OSA, in patients with obesity and moderate to severe OSA, conducted at 60 sites in nine countries. Results from both were presented in June 2024 at the annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association and were simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The first trial enrolled 469 participants who were unable or unwilling to use PAP therapy, while the second included 234 who had been using PAP for at least 3 months and planned to continue during the trial. In both, the participants randomly received either 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide or placebo once weekly for 52 weeks.

At baseline, 65%-70% of participants had severe OSA, with more than 30 events/h on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and a mean of 51.5 events/h. By 52 weeks, those randomized to tirzepatide had 27-30 fewer events/h, compared with 4-6 fewer events/h for those taking placebo. In addition, significantly more of those on tirzepatide achieved OSA remission or severity reduction to mild.

Those randomized to tirzepatide also averaged up to 20% weight loss, significantly more than with placebo. “The improvement in AHI in participants with OSA is likely related to body weight reduction with Zepbound,” according to an FDA statement.

Side effects of tirzepatide include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal discomfort and pain, injection site reactions, fatigue, hypersensitivity reactions (typically fever and rash), burping, hair loss, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In an editorial accompanying The New England Journal of Medicine publication of the SURMOUNT-OSA results, Sanjay R. Patel, MD, wrote: “The potential incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment algorithms for obstructive sleep apnea should include consideration of the challenges of adherence to treatment and the imperative to address racial disparities in medical care.”

Patel, who is professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, and medical director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Comprehensive Sleep Disorders program, pointed out that suboptimal adherence to continuous PAP therapy has been a major limitation, but that adherence to the GLP-1 drug class has also been suboptimal.

“Although adherence to tirzepatide therapy in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was high, real-world evidence suggests that nearly 50% of patients who begin treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist for obesity discontinue therapy within 12 months. Thus, it is likely that any incorporation of tirzepatide into treatment pathways for obstructive sleep apnea will not diminish the importance of long-term strategies to optimize adherence to treatment.”

Moreover, Patel noted, “racial disparities in the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists among patients with diabetes arouse concern that the addition of tirzepatide as a treatment option for obstructive sleep apnea without directly addressing policies relative to coverage of care will only further exacerbate already pervasive disparities in clinical care for obstructive sleep apnea.”

Patel reported consulting for Apnimed, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Lilly USA, NovaResp Technologies, Philips Respironics, and Powell Mansfield. He is a fiduciary officer of BreathPA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reality of Night Shifts: How to Stay Sharp and Healthy

Laura Vater remembers sneaking into her home after 12-hour night shifts during medical training while her husband distracted their toddler. The stealthy tag-teaming effort helped her get enough undisturbed sleep before returning to an Indiana University hospital the following night to repeat the pattern.

“He would pretend to take out the trash when I pulled in,” said Vater, MD, now a gastrointestinal oncologist and assistant professor of medicine at IU Health Simon Cancer Center in Indianapolis. “I would sneak in so she [their daughter] wouldn’t see me, and then he would go back in.”

For Vater, prioritizing sleep during the day to combat sleep deprivation common among doctors-in-training on night shifts required enlisting a supportive spouse. It’s just one of the tips she and a few chief residents shared with this news organization for staying sharp and healthy during overnight rotations.

While the pace of patient rounds may slow from the frenetic daytime rush, training as a doctor after the sun goes down can be quite challenging for residents, they told this news organization. From sleep deprivation working while the rest of us slumbers to the after-effects of late-night caffeine, learning to manage night rotations requires a balance of preparation and attention to personal health while caring for others, the residents and adviser said.

Compromised sleep is one of the biggest hurdles residents have to overcome. Sleep loss comes with risks to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, among other heath conditions, according to Medscape Medical News reports. And night shift workers who sleep 6 or fewer hours a night have at least one sleep disorder.

Sleep deprivation associated with overnight call schedules also can worsen a resident’s mood and motivation while impairing their judgment, leading to medical errors, according to a new study published in JAMA Open Network. The study proposed shorter consecutive night shifts and naps as ways to offset the results of sleep loss, especially for interns or first-year residents.

Residency programs recently have been experimenting with shorter call schedules.

Catching Zzs

Working the night shift demands a disciplined sleep schedule, said Nat deQuillfeldt, MD, a Denver Health chief resident in the University of Colorado’s internal medicine residency program.

“When I was on night admissions, I was very strict about going to sleep at 8 AM and waking at 3 PM every single day. It can be very tempting to try to stay up and spend time with loved ones, but my husband and I both prioritized my physical well-being for those weeks,” said deQuillfeldt, a PGY-4 resident. “It was especially challenging for me because I had to commute about 50 minutes each way and without such a rigid schedule I would have struggled to be on time.”

deQuillfeldt doesn’t have young children at home, a noisy community, or other distractions to interrupt sleep during the day. But it was still difficult for her to sleep while the sun was out. “I used an eye mask and ear plugs but definitely woke up more often than I would at night.”

Blackout curtains may have helped, she added.

“Without adequate sleep, your clinical thinking is not as sharp. When emergencies happen overnight, you’re often the first person to arrive and need to be able to make rapid, accurate assessments and decisions.”

As a chief resident, she chooses never to sleep during night shifts.

“I personally didn’t want to leave my interns alone or make them feel like they were waking me up or bothering me if they needed help, and I also didn’t want to be groggy in case of a rapid response or code blue.”

But napping on night shift is definitely possible, deQuillfeldt said. Between following up on overnight lab results, answering nurses’ questions, and responding to emergencies, she found downtime on night shift to eat and hydrate. She believes others can catch an hour or 2 of shut eye, even if they work in the intensive care unit, or 3-4 hours on rare quiet nights.

Vater suggests residents transitioning from daytime work to night shift prepare by trying to catch an afternoon nap, staying up later the night before the change, and banking sleep hours in advance.

When he knows he’s starting night shifts, Apurva Popat, MD, said he tries to go to sleep an hour or so later nights before to avoid becoming sleep deprived. The chief resident of internal medicine at Marshfield Clinic Health System in Marshfield, Wisconsin, doesn’t recommend sleeping during the night shift.

“I typically try not to sleep, even if I have time, so I can go home and sleep later in the morning,” said Popat, a PGY-3 resident.

To help him snooze, he uses blackout curtains and a fan to block out noise. His wife, a first-year internal medicine intern, often works a different shift, so she helps set up his sleeping environment and he reciprocates when it’s her turn for night shifts.

Some interns may need to catch a 20- to 30-minute nap on the first night shift, he said.

Popat also seeks out brighter areas of the hospital, such as the emergency department, where there are more people and colleagues to keep him alert.

Bypass Vending Machines

Lack of sleep makes it even more difficult to eat healthy on night shift, said Vater, who advises residents about wellness issues at IU and on social media.

“When you are sleep deprived, when you do not get enough sleep, you eat but you don’t feel full,” she said. “It’s hard to eat well on night shift. It’s harder if you go to the break room and there’s candy and junk food.”

Vater said that, as a resident, she brought a lunch bag to the hospital during night shifts. “I never had time to prep food, so I’d bring a whole apple, a whole orange, a whole avocado or nuts. It allowed me to eat more fruits and vegetables than I normally would.”

She advises caution when considering coffee to stay awake, especially after about 9 PM, which could interfere with sleep residents need later when they finish their shifts. Caffeine may help in the moment, but it prevents deep sleep, Vater said. So when residents finally get sleep after their shifts, they may wake up feeling tired, she said.

To avoid sleepiness, Popat brings protein shakes with him to night shifts. They stave off sugar spikes and keep his energy level high, he said. He might have a protein shake and fruit before he leaves home and carry his vegetarian dinner with him to eat in the early morning hours when the hospital is calm.

Eating small and frequent meals also helps ward off sleepiness, deQuillfeldt said.

Take the Stairs

Trying to stay healthy on night shifts, Vater also checked on patients by taking the stairs. “I’d set the timer on my phone for 30 minutes and if I got paged at 15, I’d pause the timer and reset it if I had a moment later. I’d get at least 30 minutes in, although not always continuous. I think some activity is better than none.”

Vater said her hospital had a gym, but it wasn’t practical for her because it was further away from where she worked. “Sometimes my coresidents would be more creative, and we would do squats.”

Popat tries to lift weights 2 hours before his night shift, but he also takes short walks between patients’ rooms in the early morning hours when it’s quietest. He also promotes deep breathing to stay alert.

Ask for a Ride

Vater urges those coming off night shifts, especially those transitioning for the first time from daytime rotations, not to drive if they’re exhausted. “Get an Uber. ... Make sure you get a ride home.”

The CU residency program covers the cost of a ridesharing service when doctors-in-training are too tired to drive home, deQuillfeldt said. “We really try to encourage people to use this to reduce the risk of car accidents.”

Promoting Mental Health

The residency program also links residents with primary care and mental health services. People who really struggle with shift work sleep disorder may qualify for medications to help them stay awake overnight, in addition to sleep hygiene apps and sleep aides.

“Night shifts can put a strain on mental health, especially when you’re only working, eating, and sleeping and not spending any time with family and friends,” deQuillfeldt said. “My husband works late afternoons, so we often would go weeks seeing each other for 15-20 minutes a day.”

“Sleeping when the sun is out often leads to a lack of light exposure which can compound the problem. Seeking mental health support early is really important to avoiding burnout,” she said.

She also recommended planning a fun weekend activity, trip, or celebration with friends or family after night shifts end “so you have something to look forward to…It’s so important to have a light at the end of the tunnel, which will allow you to enjoy the sense of accomplishment even more.”

For more advice on the subject, consider the American Medical Association guide to managing sleep deprivation in residency or Laura Vater’s tips for night shifts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Laura Vater remembers sneaking into her home after 12-hour night shifts during medical training while her husband distracted their toddler. The stealthy tag-teaming effort helped her get enough undisturbed sleep before returning to an Indiana University hospital the following night to repeat the pattern.

“He would pretend to take out the trash when I pulled in,” said Vater, MD, now a gastrointestinal oncologist and assistant professor of medicine at IU Health Simon Cancer Center in Indianapolis. “I would sneak in so she [their daughter] wouldn’t see me, and then he would go back in.”

For Vater, prioritizing sleep during the day to combat sleep deprivation common among doctors-in-training on night shifts required enlisting a supportive spouse. It’s just one of the tips she and a few chief residents shared with this news organization for staying sharp and healthy during overnight rotations.

While the pace of patient rounds may slow from the frenetic daytime rush, training as a doctor after the sun goes down can be quite challenging for residents, they told this news organization. From sleep deprivation working while the rest of us slumbers to the after-effects of late-night caffeine, learning to manage night rotations requires a balance of preparation and attention to personal health while caring for others, the residents and adviser said.

Compromised sleep is one of the biggest hurdles residents have to overcome. Sleep loss comes with risks to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, among other heath conditions, according to Medscape Medical News reports. And night shift workers who sleep 6 or fewer hours a night have at least one sleep disorder.

Sleep deprivation associated with overnight call schedules also can worsen a resident’s mood and motivation while impairing their judgment, leading to medical errors, according to a new study published in JAMA Open Network. The study proposed shorter consecutive night shifts and naps as ways to offset the results of sleep loss, especially for interns or first-year residents.

Residency programs recently have been experimenting with shorter call schedules.

Catching Zzs

Working the night shift demands a disciplined sleep schedule, said Nat deQuillfeldt, MD, a Denver Health chief resident in the University of Colorado’s internal medicine residency program.

“When I was on night admissions, I was very strict about going to sleep at 8 AM and waking at 3 PM every single day. It can be very tempting to try to stay up and spend time with loved ones, but my husband and I both prioritized my physical well-being for those weeks,” said deQuillfeldt, a PGY-4 resident. “It was especially challenging for me because I had to commute about 50 minutes each way and without such a rigid schedule I would have struggled to be on time.”

deQuillfeldt doesn’t have young children at home, a noisy community, or other distractions to interrupt sleep during the day. But it was still difficult for her to sleep while the sun was out. “I used an eye mask and ear plugs but definitely woke up more often than I would at night.”

Blackout curtains may have helped, she added.

“Without adequate sleep, your clinical thinking is not as sharp. When emergencies happen overnight, you’re often the first person to arrive and need to be able to make rapid, accurate assessments and decisions.”

As a chief resident, she chooses never to sleep during night shifts.

“I personally didn’t want to leave my interns alone or make them feel like they were waking me up or bothering me if they needed help, and I also didn’t want to be groggy in case of a rapid response or code blue.”

But napping on night shift is definitely possible, deQuillfeldt said. Between following up on overnight lab results, answering nurses’ questions, and responding to emergencies, she found downtime on night shift to eat and hydrate. She believes others can catch an hour or 2 of shut eye, even if they work in the intensive care unit, or 3-4 hours on rare quiet nights.

Vater suggests residents transitioning from daytime work to night shift prepare by trying to catch an afternoon nap, staying up later the night before the change, and banking sleep hours in advance.

When he knows he’s starting night shifts, Apurva Popat, MD, said he tries to go to sleep an hour or so later nights before to avoid becoming sleep deprived. The chief resident of internal medicine at Marshfield Clinic Health System in Marshfield, Wisconsin, doesn’t recommend sleeping during the night shift.

“I typically try not to sleep, even if I have time, so I can go home and sleep later in the morning,” said Popat, a PGY-3 resident.

To help him snooze, he uses blackout curtains and a fan to block out noise. His wife, a first-year internal medicine intern, often works a different shift, so she helps set up his sleeping environment and he reciprocates when it’s her turn for night shifts.

Some interns may need to catch a 20- to 30-minute nap on the first night shift, he said.

Popat also seeks out brighter areas of the hospital, such as the emergency department, where there are more people and colleagues to keep him alert.

Bypass Vending Machines

Lack of sleep makes it even more difficult to eat healthy on night shift, said Vater, who advises residents about wellness issues at IU and on social media.

“When you are sleep deprived, when you do not get enough sleep, you eat but you don’t feel full,” she said. “It’s hard to eat well on night shift. It’s harder if you go to the break room and there’s candy and junk food.”

Vater said that, as a resident, she brought a lunch bag to the hospital during night shifts. “I never had time to prep food, so I’d bring a whole apple, a whole orange, a whole avocado or nuts. It allowed me to eat more fruits and vegetables than I normally would.”

She advises caution when considering coffee to stay awake, especially after about 9 PM, which could interfere with sleep residents need later when they finish their shifts. Caffeine may help in the moment, but it prevents deep sleep, Vater said. So when residents finally get sleep after their shifts, they may wake up feeling tired, she said.

To avoid sleepiness, Popat brings protein shakes with him to night shifts. They stave off sugar spikes and keep his energy level high, he said. He might have a protein shake and fruit before he leaves home and carry his vegetarian dinner with him to eat in the early morning hours when the hospital is calm.

Eating small and frequent meals also helps ward off sleepiness, deQuillfeldt said.

Take the Stairs

Trying to stay healthy on night shifts, Vater also checked on patients by taking the stairs. “I’d set the timer on my phone for 30 minutes and if I got paged at 15, I’d pause the timer and reset it if I had a moment later. I’d get at least 30 minutes in, although not always continuous. I think some activity is better than none.”

Vater said her hospital had a gym, but it wasn’t practical for her because it was further away from where she worked. “Sometimes my coresidents would be more creative, and we would do squats.”

Popat tries to lift weights 2 hours before his night shift, but he also takes short walks between patients’ rooms in the early morning hours when it’s quietest. He also promotes deep breathing to stay alert.

Ask for a Ride

Vater urges those coming off night shifts, especially those transitioning for the first time from daytime rotations, not to drive if they’re exhausted. “Get an Uber. ... Make sure you get a ride home.”

The CU residency program covers the cost of a ridesharing service when doctors-in-training are too tired to drive home, deQuillfeldt said. “We really try to encourage people to use this to reduce the risk of car accidents.”

Promoting Mental Health

The residency program also links residents with primary care and mental health services. People who really struggle with shift work sleep disorder may qualify for medications to help them stay awake overnight, in addition to sleep hygiene apps and sleep aides.

“Night shifts can put a strain on mental health, especially when you’re only working, eating, and sleeping and not spending any time with family and friends,” deQuillfeldt said. “My husband works late afternoons, so we often would go weeks seeing each other for 15-20 minutes a day.”

“Sleeping when the sun is out often leads to a lack of light exposure which can compound the problem. Seeking mental health support early is really important to avoiding burnout,” she said.

She also recommended planning a fun weekend activity, trip, or celebration with friends or family after night shifts end “so you have something to look forward to…It’s so important to have a light at the end of the tunnel, which will allow you to enjoy the sense of accomplishment even more.”

For more advice on the subject, consider the American Medical Association guide to managing sleep deprivation in residency or Laura Vater’s tips for night shifts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Laura Vater remembers sneaking into her home after 12-hour night shifts during medical training while her husband distracted their toddler. The stealthy tag-teaming effort helped her get enough undisturbed sleep before returning to an Indiana University hospital the following night to repeat the pattern.

“He would pretend to take out the trash when I pulled in,” said Vater, MD, now a gastrointestinal oncologist and assistant professor of medicine at IU Health Simon Cancer Center in Indianapolis. “I would sneak in so she [their daughter] wouldn’t see me, and then he would go back in.”

For Vater, prioritizing sleep during the day to combat sleep deprivation common among doctors-in-training on night shifts required enlisting a supportive spouse. It’s just one of the tips she and a few chief residents shared with this news organization for staying sharp and healthy during overnight rotations.

While the pace of patient rounds may slow from the frenetic daytime rush, training as a doctor after the sun goes down can be quite challenging for residents, they told this news organization. From sleep deprivation working while the rest of us slumbers to the after-effects of late-night caffeine, learning to manage night rotations requires a balance of preparation and attention to personal health while caring for others, the residents and adviser said.

Compromised sleep is one of the biggest hurdles residents have to overcome. Sleep loss comes with risks to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, among other heath conditions, according to Medscape Medical News reports. And night shift workers who sleep 6 or fewer hours a night have at least one sleep disorder.

Sleep deprivation associated with overnight call schedules also can worsen a resident’s mood and motivation while impairing their judgment, leading to medical errors, according to a new study published in JAMA Open Network. The study proposed shorter consecutive night shifts and naps as ways to offset the results of sleep loss, especially for interns or first-year residents.

Residency programs recently have been experimenting with shorter call schedules.

Catching Zzs

Working the night shift demands a disciplined sleep schedule, said Nat deQuillfeldt, MD, a Denver Health chief resident in the University of Colorado’s internal medicine residency program.

“When I was on night admissions, I was very strict about going to sleep at 8 AM and waking at 3 PM every single day. It can be very tempting to try to stay up and spend time with loved ones, but my husband and I both prioritized my physical well-being for those weeks,” said deQuillfeldt, a PGY-4 resident. “It was especially challenging for me because I had to commute about 50 minutes each way and without such a rigid schedule I would have struggled to be on time.”

deQuillfeldt doesn’t have young children at home, a noisy community, or other distractions to interrupt sleep during the day. But it was still difficult for her to sleep while the sun was out. “I used an eye mask and ear plugs but definitely woke up more often than I would at night.”

Blackout curtains may have helped, she added.

“Without adequate sleep, your clinical thinking is not as sharp. When emergencies happen overnight, you’re often the first person to arrive and need to be able to make rapid, accurate assessments and decisions.”

As a chief resident, she chooses never to sleep during night shifts.

“I personally didn’t want to leave my interns alone or make them feel like they were waking me up or bothering me if they needed help, and I also didn’t want to be groggy in case of a rapid response or code blue.”

But napping on night shift is definitely possible, deQuillfeldt said. Between following up on overnight lab results, answering nurses’ questions, and responding to emergencies, she found downtime on night shift to eat and hydrate. She believes others can catch an hour or 2 of shut eye, even if they work in the intensive care unit, or 3-4 hours on rare quiet nights.

Vater suggests residents transitioning from daytime work to night shift prepare by trying to catch an afternoon nap, staying up later the night before the change, and banking sleep hours in advance.

When he knows he’s starting night shifts, Apurva Popat, MD, said he tries to go to sleep an hour or so later nights before to avoid becoming sleep deprived. The chief resident of internal medicine at Marshfield Clinic Health System in Marshfield, Wisconsin, doesn’t recommend sleeping during the night shift.

“I typically try not to sleep, even if I have time, so I can go home and sleep later in the morning,” said Popat, a PGY-3 resident.

To help him snooze, he uses blackout curtains and a fan to block out noise. His wife, a first-year internal medicine intern, often works a different shift, so she helps set up his sleeping environment and he reciprocates when it’s her turn for night shifts.

Some interns may need to catch a 20- to 30-minute nap on the first night shift, he said.

Popat also seeks out brighter areas of the hospital, such as the emergency department, where there are more people and colleagues to keep him alert.

Bypass Vending Machines

Lack of sleep makes it even more difficult to eat healthy on night shift, said Vater, who advises residents about wellness issues at IU and on social media.

“When you are sleep deprived, when you do not get enough sleep, you eat but you don’t feel full,” she said. “It’s hard to eat well on night shift. It’s harder if you go to the break room and there’s candy and junk food.”

Vater said that, as a resident, she brought a lunch bag to the hospital during night shifts. “I never had time to prep food, so I’d bring a whole apple, a whole orange, a whole avocado or nuts. It allowed me to eat more fruits and vegetables than I normally would.”

She advises caution when considering coffee to stay awake, especially after about 9 PM, which could interfere with sleep residents need later when they finish their shifts. Caffeine may help in the moment, but it prevents deep sleep, Vater said. So when residents finally get sleep after their shifts, they may wake up feeling tired, she said.

To avoid sleepiness, Popat brings protein shakes with him to night shifts. They stave off sugar spikes and keep his energy level high, he said. He might have a protein shake and fruit before he leaves home and carry his vegetarian dinner with him to eat in the early morning hours when the hospital is calm.

Eating small and frequent meals also helps ward off sleepiness, deQuillfeldt said.

Take the Stairs

Trying to stay healthy on night shifts, Vater also checked on patients by taking the stairs. “I’d set the timer on my phone for 30 minutes and if I got paged at 15, I’d pause the timer and reset it if I had a moment later. I’d get at least 30 minutes in, although not always continuous. I think some activity is better than none.”

Vater said her hospital had a gym, but it wasn’t practical for her because it was further away from where she worked. “Sometimes my coresidents would be more creative, and we would do squats.”

Popat tries to lift weights 2 hours before his night shift, but he also takes short walks between patients’ rooms in the early morning hours when it’s quietest. He also promotes deep breathing to stay alert.

Ask for a Ride

Vater urges those coming off night shifts, especially those transitioning for the first time from daytime rotations, not to drive if they’re exhausted. “Get an Uber. ... Make sure you get a ride home.”

The CU residency program covers the cost of a ridesharing service when doctors-in-training are too tired to drive home, deQuillfeldt said. “We really try to encourage people to use this to reduce the risk of car accidents.”

Promoting Mental Health

The residency program also links residents with primary care and mental health services. People who really struggle with shift work sleep disorder may qualify for medications to help them stay awake overnight, in addition to sleep hygiene apps and sleep aides.

“Night shifts can put a strain on mental health, especially when you’re only working, eating, and sleeping and not spending any time with family and friends,” deQuillfeldt said. “My husband works late afternoons, so we often would go weeks seeing each other for 15-20 minutes a day.”

“Sleeping when the sun is out often leads to a lack of light exposure which can compound the problem. Seeking mental health support early is really important to avoiding burnout,” she said.

She also recommended planning a fun weekend activity, trip, or celebration with friends or family after night shifts end “so you have something to look forward to…It’s so important to have a light at the end of the tunnel, which will allow you to enjoy the sense of accomplishment even more.”

For more advice on the subject, consider the American Medical Association guide to managing sleep deprivation in residency or Laura Vater’s tips for night shifts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Finally, a New Drug for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?

A drug that combines the atypical antipsychotic brexpiprazole and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline provides significantly greater relief of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms than sertraline plus placebo, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

The medication is currently under review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and if approved, will be the first pharmacologic option for PTSD in more than 20 years.

The trial met its primary endpoint of change in the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) (CAPS-5) total score at week 10 and secondary patient-reported outcomes of PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression.

“And what is really cool, what’s really impactful is the combination worked better than sertraline plus placebo on a brief inventory of psychosocial functioning,” study investigator Lori L. Davis, a senior research psychiatrist, Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Alabama, said in an interview.

“We can treat symptoms but that’s where the rubber meets the road, in terms of are they functioning better,” added Davis, who is also an adjunct professor of psychiatry, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The findings were published online on December 18 in JAMA Psychiatry and reported in May 2024 as part of a trio of trials conducted by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, codevelopers of the drug.

Clinically Meaningful

“This study provides promising results for a medication that may be an important new option for PTSD,” John Krystal, MD, director, Clinical Neuroscience Division, National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “New PTSD treatments are a high priority.”

Currently, there are two FDA-approved medication treatments for PTSD — sertraline and paroxetine.

“They are helpful for many people, but patients are often left with residual symptoms or tolerability issues,” noted Krystal, who is also professor and chair of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

“New medications that might address the important ‘effectiveness gap’ in PTSD could help to reduce the remaining distress, disability, and suicide risk associated with PTSD.”

The double-blind, phase 3 trial included 416 adults aged 18-65 years with a DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD and symptoms for at least 6 months prior to screening. Patients underwent a 1-week placebo-run in period followed by randomization to daily oral brexpiprazole 2-3 mg plus sertraline 150 mg or daily sertraline 150 mg plus placebo for 11 weeks.

Participants’ mean age was 37.4 years, 74.5% were women, and mean CAPS-5 total score was 38.4, suggesting moderate to high severity PTSD, Davis said. The average time from the index traumatic event was 4 years and three fourths had no prior exposure to PTSD prescription medications.

At week 10, the mean change in CAPS-5 score from randomization was –19.2 points in the brexpiprazole plus sertraline group and –13.6 points in the sertraline plus placebo group (95% CI, –8.79 to –2.38; P < .001).

Asked whether the 5.59-point treatment difference is clinically meaningful, Davis said there is no widely agreed definition for change in CAPS-5 total score but that a within-group reduction of more than 10-13 points is most-often cited as being clinically meaningful.

The key secondary endpoint of least square mean change in the patient-reported Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Function total score from baseline to week 12 was –33.8 with the combination vs –21.8 with sertraline plus placebo (95% CI, –19.4 to –4.62; P = .002).

“That’s clinically meaningful for me as a provider and a clinician and a researcher when you’re getting the PTSD symptom change differences in parallel with the improvement in functional outcome,” she said. “I see that as the clinically meaningful gauge.”

In terms of safety, 3.9% of the participants in the brexpiprazole/sertraline group and 10.2% of those in the sertraline/placebo group discontinued treatment because of adverse events.

In both the combination and control groups, the only treatment-emergent adverse event with an incidence of more than 10% was nausea (12.2% vs 11.7%, respectively).

At the last visit, the mean change in body weight from baseline was an increase of 1.3 kg for brexpiprazole plus sertraline vs 0 kg for sertraline alone. Rates of fatigue (6.8% vs 4.1%) and somnolence (5.4% vs 2.6%) were also higher with brexpiprazole plus sertraline.

A Trio of Clinical Trials

The findings are part of a larger program reported by the drug makers that includes a flexible-dose brexpiprazole phase 2 trial that met the same CAPS-5 primary endpoint and a second phase 3 trial (072 study) that did not.

“We’ve looked at that data and the sertraline/placebo response was a lot higher, so it was not due to a lack of response with the combination but due to a more robust response with the active control,” Davis said. “But we want to point out for that 072 study, there was still important separation between the combination and sertraline plus placebo on the functional outcome.”

All three trials ran for 12 weeks, so longer-term efficacy and safety data are needed, she said. Other limitations of the published phase 3 study are the patient eligibility criteria, restrictions on concomitant therapy, and lack of non-US sites, which many limit generalizability, the authors noted.

“Specifically, the exclusion of patients with a current major depressive episode is both a strength (to show a specific effect on PTSD) and a limitation (given the high prevalence of comorbid depression in PTSD),” they added.

Kudos, Caveats

Reached for comment, Vincent F. Capaldi, II, MD, ScM, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences School of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, said the exclusion of these patients is a limitation but that the study was well designed and conducted in a large sample across the United States.

“The findings suggest that brexpiprazole plus sertraline is a more effective treatment for PTSD than sertraline alone,” he said. “This finding is significant for our service members, who suffer from PTSD at higher rates than the general population.”

Additionally, the significant improvement in psychosocial functioning at week 12 “is important because PTSD is known to cause significant social and occupational disability, as well as quality-of-life issues,” he said.

Capaldi pointed out, however, that the study was conducted only at US sites and did not specifically target military/veteran persons, which may limit applicability to these unique populations.

“While subgroup analyses were generally consistent with the primary analysis, the study was not powered to detect differences between subgroups,” he added. “These subgroup analyses are quite important when considering military and veteran populations.”

Further research is needed to explore whether certain traumas are more responsive to combination treatment, the efficacy of augmenting existing sertraline therapy, and the specific mechanisms of brexpiprazole driving the improved outcomes, Capaldi said.

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, which was involved in the design, conduct, and data analysis. Davis reported receiving advisory board fees from Otsuka and Boehringer Ingelheim; lecture fees from Clinical Care Options; and grants from Alkermes, the Veterans Affairs, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Department of Defense, and Social Finance. Several coauthors are employees of Otsuka. Krystal reported serving as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Aptinyx, Biogen, IDEC, Bionomics, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Clearmind Medicine, Cybin IRL, Enveric Biosciences, Epiodyne, EpiVario, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Perception Neuroscience, Praxis Precision Medicines, Springcare, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Krystal also reported serving as a scientific advisory board member for several companies and holding several patents.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A drug that combines the atypical antipsychotic brexpiprazole and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline provides significantly greater relief of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms than sertraline plus placebo, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

The medication is currently under review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and if approved, will be the first pharmacologic option for PTSD in more than 20 years.

The trial met its primary endpoint of change in the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) (CAPS-5) total score at week 10 and secondary patient-reported outcomes of PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression.

“And what is really cool, what’s really impactful is the combination worked better than sertraline plus placebo on a brief inventory of psychosocial functioning,” study investigator Lori L. Davis, a senior research psychiatrist, Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Alabama, said in an interview.

“We can treat symptoms but that’s where the rubber meets the road, in terms of are they functioning better,” added Davis, who is also an adjunct professor of psychiatry, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The findings were published online on December 18 in JAMA Psychiatry and reported in May 2024 as part of a trio of trials conducted by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, codevelopers of the drug.

Clinically Meaningful

“This study provides promising results for a medication that may be an important new option for PTSD,” John Krystal, MD, director, Clinical Neuroscience Division, National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “New PTSD treatments are a high priority.”

Currently, there are two FDA-approved medication treatments for PTSD — sertraline and paroxetine.

“They are helpful for many people, but patients are often left with residual symptoms or tolerability issues,” noted Krystal, who is also professor and chair of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

“New medications that might address the important ‘effectiveness gap’ in PTSD could help to reduce the remaining distress, disability, and suicide risk associated with PTSD.”

The double-blind, phase 3 trial included 416 adults aged 18-65 years with a DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD and symptoms for at least 6 months prior to screening. Patients underwent a 1-week placebo-run in period followed by randomization to daily oral brexpiprazole 2-3 mg plus sertraline 150 mg or daily sertraline 150 mg plus placebo for 11 weeks.

Participants’ mean age was 37.4 years, 74.5% were women, and mean CAPS-5 total score was 38.4, suggesting moderate to high severity PTSD, Davis said. The average time from the index traumatic event was 4 years and three fourths had no prior exposure to PTSD prescription medications.

At week 10, the mean change in CAPS-5 score from randomization was –19.2 points in the brexpiprazole plus sertraline group and –13.6 points in the sertraline plus placebo group (95% CI, –8.79 to –2.38; P < .001).

Asked whether the 5.59-point treatment difference is clinically meaningful, Davis said there is no widely agreed definition for change in CAPS-5 total score but that a within-group reduction of more than 10-13 points is most-often cited as being clinically meaningful.

The key secondary endpoint of least square mean change in the patient-reported Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Function total score from baseline to week 12 was –33.8 with the combination vs –21.8 with sertraline plus placebo (95% CI, –19.4 to –4.62; P = .002).

“That’s clinically meaningful for me as a provider and a clinician and a researcher when you’re getting the PTSD symptom change differences in parallel with the improvement in functional outcome,” she said. “I see that as the clinically meaningful gauge.”

In terms of safety, 3.9% of the participants in the brexpiprazole/sertraline group and 10.2% of those in the sertraline/placebo group discontinued treatment because of adverse events.

In both the combination and control groups, the only treatment-emergent adverse event with an incidence of more than 10% was nausea (12.2% vs 11.7%, respectively).

At the last visit, the mean change in body weight from baseline was an increase of 1.3 kg for brexpiprazole plus sertraline vs 0 kg for sertraline alone. Rates of fatigue (6.8% vs 4.1%) and somnolence (5.4% vs 2.6%) were also higher with brexpiprazole plus sertraline.

A Trio of Clinical Trials

The findings are part of a larger program reported by the drug makers that includes a flexible-dose brexpiprazole phase 2 trial that met the same CAPS-5 primary endpoint and a second phase 3 trial (072 study) that did not.

“We’ve looked at that data and the sertraline/placebo response was a lot higher, so it was not due to a lack of response with the combination but due to a more robust response with the active control,” Davis said. “But we want to point out for that 072 study, there was still important separation between the combination and sertraline plus placebo on the functional outcome.”

All three trials ran for 12 weeks, so longer-term efficacy and safety data are needed, she said. Other limitations of the published phase 3 study are the patient eligibility criteria, restrictions on concomitant therapy, and lack of non-US sites, which many limit generalizability, the authors noted.

“Specifically, the exclusion of patients with a current major depressive episode is both a strength (to show a specific effect on PTSD) and a limitation (given the high prevalence of comorbid depression in PTSD),” they added.

Kudos, Caveats

Reached for comment, Vincent F. Capaldi, II, MD, ScM, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences School of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, said the exclusion of these patients is a limitation but that the study was well designed and conducted in a large sample across the United States.

“The findings suggest that brexpiprazole plus sertraline is a more effective treatment for PTSD than sertraline alone,” he said. “This finding is significant for our service members, who suffer from PTSD at higher rates than the general population.”

Additionally, the significant improvement in psychosocial functioning at week 12 “is important because PTSD is known to cause significant social and occupational disability, as well as quality-of-life issues,” he said.

Capaldi pointed out, however, that the study was conducted only at US sites and did not specifically target military/veteran persons, which may limit applicability to these unique populations.

“While subgroup analyses were generally consistent with the primary analysis, the study was not powered to detect differences between subgroups,” he added. “These subgroup analyses are quite important when considering military and veteran populations.”

Further research is needed to explore whether certain traumas are more responsive to combination treatment, the efficacy of augmenting existing sertraline therapy, and the specific mechanisms of brexpiprazole driving the improved outcomes, Capaldi said.

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, which was involved in the design, conduct, and data analysis. Davis reported receiving advisory board fees from Otsuka and Boehringer Ingelheim; lecture fees from Clinical Care Options; and grants from Alkermes, the Veterans Affairs, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Department of Defense, and Social Finance. Several coauthors are employees of Otsuka. Krystal reported serving as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Aptinyx, Biogen, IDEC, Bionomics, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Clearmind Medicine, Cybin IRL, Enveric Biosciences, Epiodyne, EpiVario, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Perception Neuroscience, Praxis Precision Medicines, Springcare, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Krystal also reported serving as a scientific advisory board member for several companies and holding several patents.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A drug that combines the atypical antipsychotic brexpiprazole and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline provides significantly greater relief of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms than sertraline plus placebo, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

The medication is currently under review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and if approved, will be the first pharmacologic option for PTSD in more than 20 years.

The trial met its primary endpoint of change in the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) (CAPS-5) total score at week 10 and secondary patient-reported outcomes of PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression.

“And what is really cool, what’s really impactful is the combination worked better than sertraline plus placebo on a brief inventory of psychosocial functioning,” study investigator Lori L. Davis, a senior research psychiatrist, Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Alabama, said in an interview.

“We can treat symptoms but that’s where the rubber meets the road, in terms of are they functioning better,” added Davis, who is also an adjunct professor of psychiatry, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The findings were published online on December 18 in JAMA Psychiatry and reported in May 2024 as part of a trio of trials conducted by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, codevelopers of the drug.

Clinically Meaningful

“This study provides promising results for a medication that may be an important new option for PTSD,” John Krystal, MD, director, Clinical Neuroscience Division, National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “New PTSD treatments are a high priority.”

Currently, there are two FDA-approved medication treatments for PTSD — sertraline and paroxetine.

“They are helpful for many people, but patients are often left with residual symptoms or tolerability issues,” noted Krystal, who is also professor and chair of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

“New medications that might address the important ‘effectiveness gap’ in PTSD could help to reduce the remaining distress, disability, and suicide risk associated with PTSD.”

The double-blind, phase 3 trial included 416 adults aged 18-65 years with a DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD and symptoms for at least 6 months prior to screening. Patients underwent a 1-week placebo-run in period followed by randomization to daily oral brexpiprazole 2-3 mg plus sertraline 150 mg or daily sertraline 150 mg plus placebo for 11 weeks.

Participants’ mean age was 37.4 years, 74.5% were women, and mean CAPS-5 total score was 38.4, suggesting moderate to high severity PTSD, Davis said. The average time from the index traumatic event was 4 years and three fourths had no prior exposure to PTSD prescription medications.

At week 10, the mean change in CAPS-5 score from randomization was –19.2 points in the brexpiprazole plus sertraline group and –13.6 points in the sertraline plus placebo group (95% CI, –8.79 to –2.38; P < .001).

Asked whether the 5.59-point treatment difference is clinically meaningful, Davis said there is no widely agreed definition for change in CAPS-5 total score but that a within-group reduction of more than 10-13 points is most-often cited as being clinically meaningful.

The key secondary endpoint of least square mean change in the patient-reported Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Function total score from baseline to week 12 was –33.8 with the combination vs –21.8 with sertraline plus placebo (95% CI, –19.4 to –4.62; P = .002).

“That’s clinically meaningful for me as a provider and a clinician and a researcher when you’re getting the PTSD symptom change differences in parallel with the improvement in functional outcome,” she said. “I see that as the clinically meaningful gauge.”

In terms of safety, 3.9% of the participants in the brexpiprazole/sertraline group and 10.2% of those in the sertraline/placebo group discontinued treatment because of adverse events.

In both the combination and control groups, the only treatment-emergent adverse event with an incidence of more than 10% was nausea (12.2% vs 11.7%, respectively).

At the last visit, the mean change in body weight from baseline was an increase of 1.3 kg for brexpiprazole plus sertraline vs 0 kg for sertraline alone. Rates of fatigue (6.8% vs 4.1%) and somnolence (5.4% vs 2.6%) were also higher with brexpiprazole plus sertraline.

A Trio of Clinical Trials

The findings are part of a larger program reported by the drug makers that includes a flexible-dose brexpiprazole phase 2 trial that met the same CAPS-5 primary endpoint and a second phase 3 trial (072 study) that did not.

“We’ve looked at that data and the sertraline/placebo response was a lot higher, so it was not due to a lack of response with the combination but due to a more robust response with the active control,” Davis said. “But we want to point out for that 072 study, there was still important separation between the combination and sertraline plus placebo on the functional outcome.”

All three trials ran for 12 weeks, so longer-term efficacy and safety data are needed, she said. Other limitations of the published phase 3 study are the patient eligibility criteria, restrictions on concomitant therapy, and lack of non-US sites, which many limit generalizability, the authors noted.

“Specifically, the exclusion of patients with a current major depressive episode is both a strength (to show a specific effect on PTSD) and a limitation (given the high prevalence of comorbid depression in PTSD),” they added.

Kudos, Caveats

Reached for comment, Vincent F. Capaldi, II, MD, ScM, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences School of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, said the exclusion of these patients is a limitation but that the study was well designed and conducted in a large sample across the United States.

“The findings suggest that brexpiprazole plus sertraline is a more effective treatment for PTSD than sertraline alone,” he said. “This finding is significant for our service members, who suffer from PTSD at higher rates than the general population.”

Additionally, the significant improvement in psychosocial functioning at week 12 “is important because PTSD is known to cause significant social and occupational disability, as well as quality-of-life issues,” he said.

Capaldi pointed out, however, that the study was conducted only at US sites and did not specifically target military/veteran persons, which may limit applicability to these unique populations.

“While subgroup analyses were generally consistent with the primary analysis, the study was not powered to detect differences between subgroups,” he added. “These subgroup analyses are quite important when considering military and veteran populations.”

Further research is needed to explore whether certain traumas are more responsive to combination treatment, the efficacy of augmenting existing sertraline therapy, and the specific mechanisms of brexpiprazole driving the improved outcomes, Capaldi said.

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, which was involved in the design, conduct, and data analysis. Davis reported receiving advisory board fees from Otsuka and Boehringer Ingelheim; lecture fees from Clinical Care Options; and grants from Alkermes, the Veterans Affairs, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Department of Defense, and Social Finance. Several coauthors are employees of Otsuka. Krystal reported serving as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Aptinyx, Biogen, IDEC, Bionomics, Boehringer Ingelheim International, Clearmind Medicine, Cybin IRL, Enveric Biosciences, Epiodyne, EpiVario, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Perception Neuroscience, Praxis Precision Medicines, Springcare, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Krystal also reported serving as a scientific advisory board member for several companies and holding several patents.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

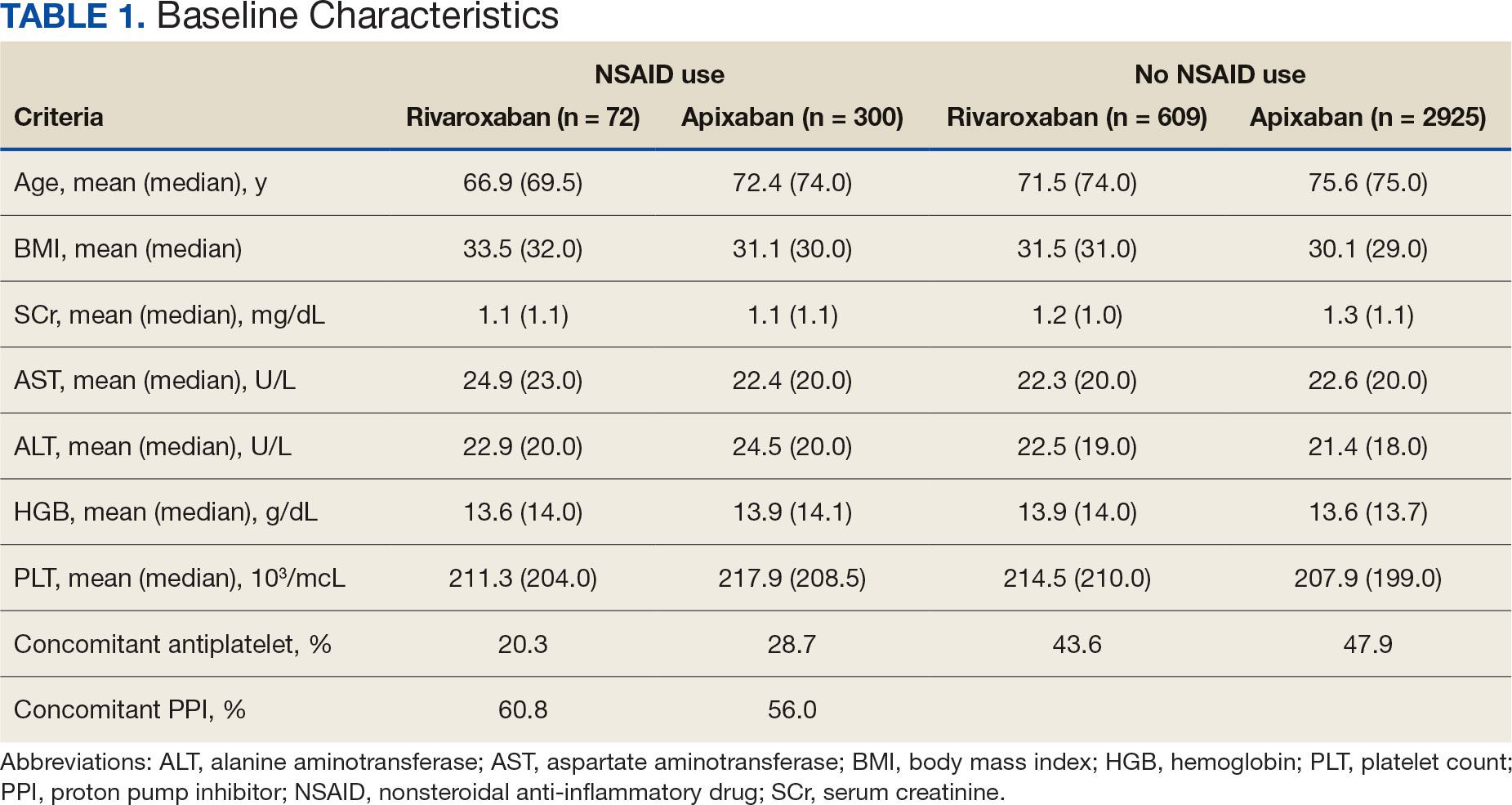

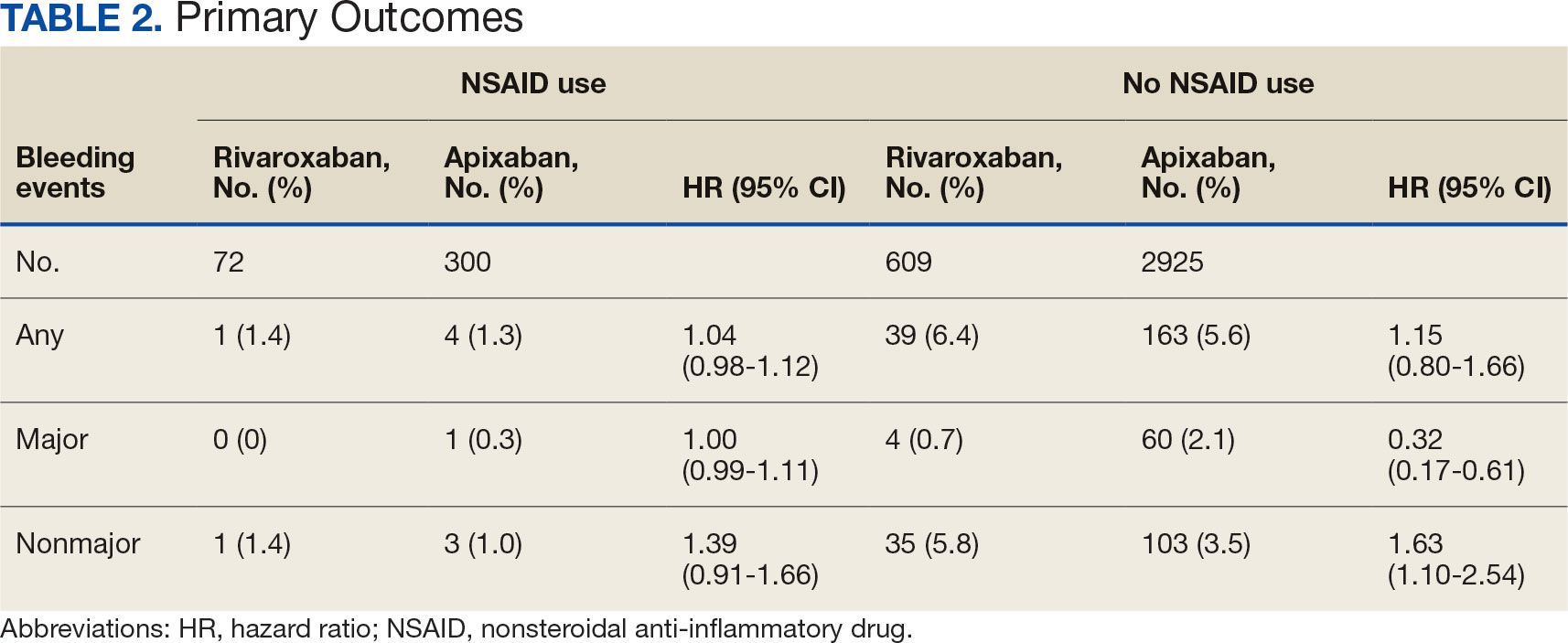

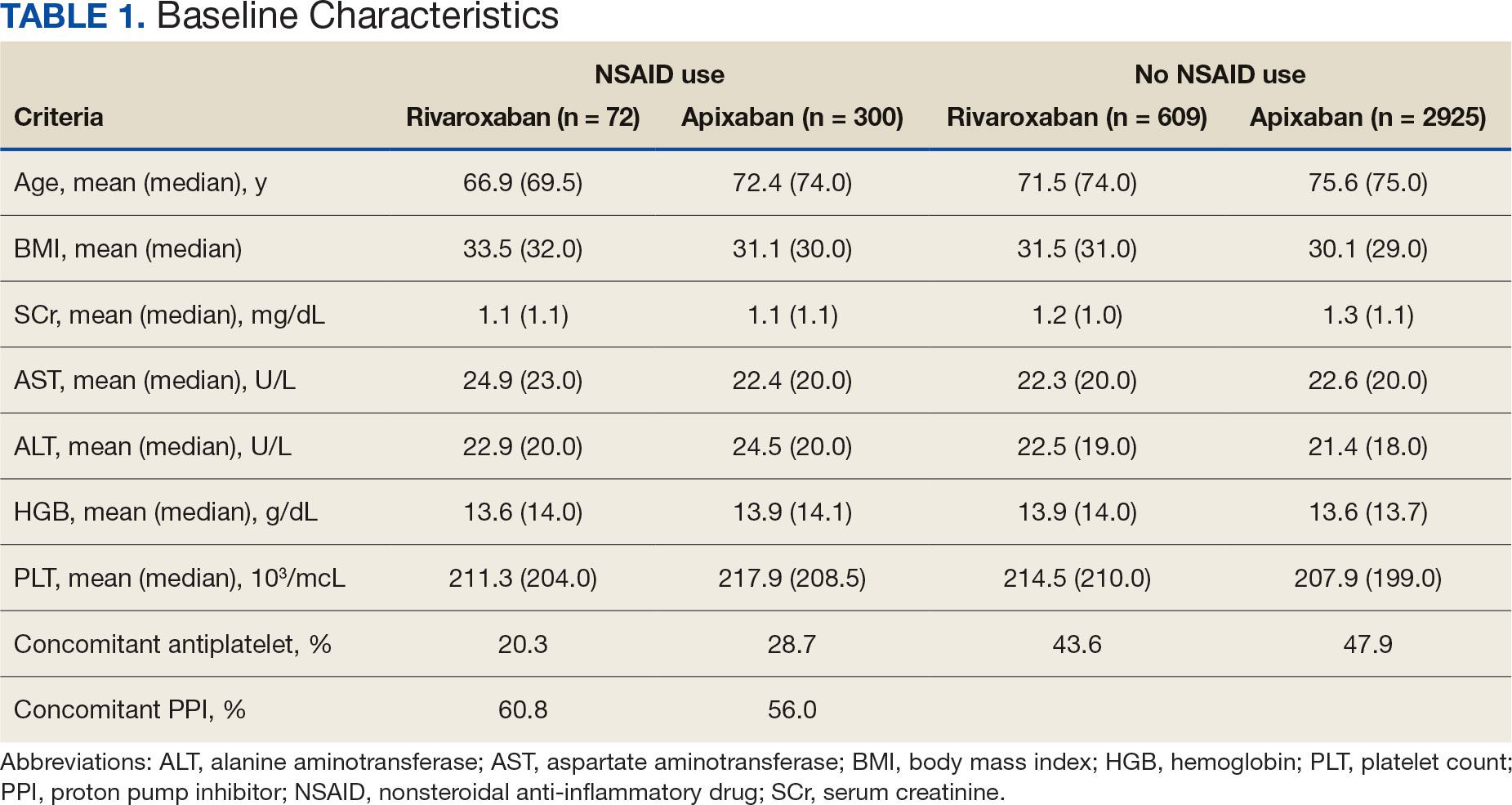

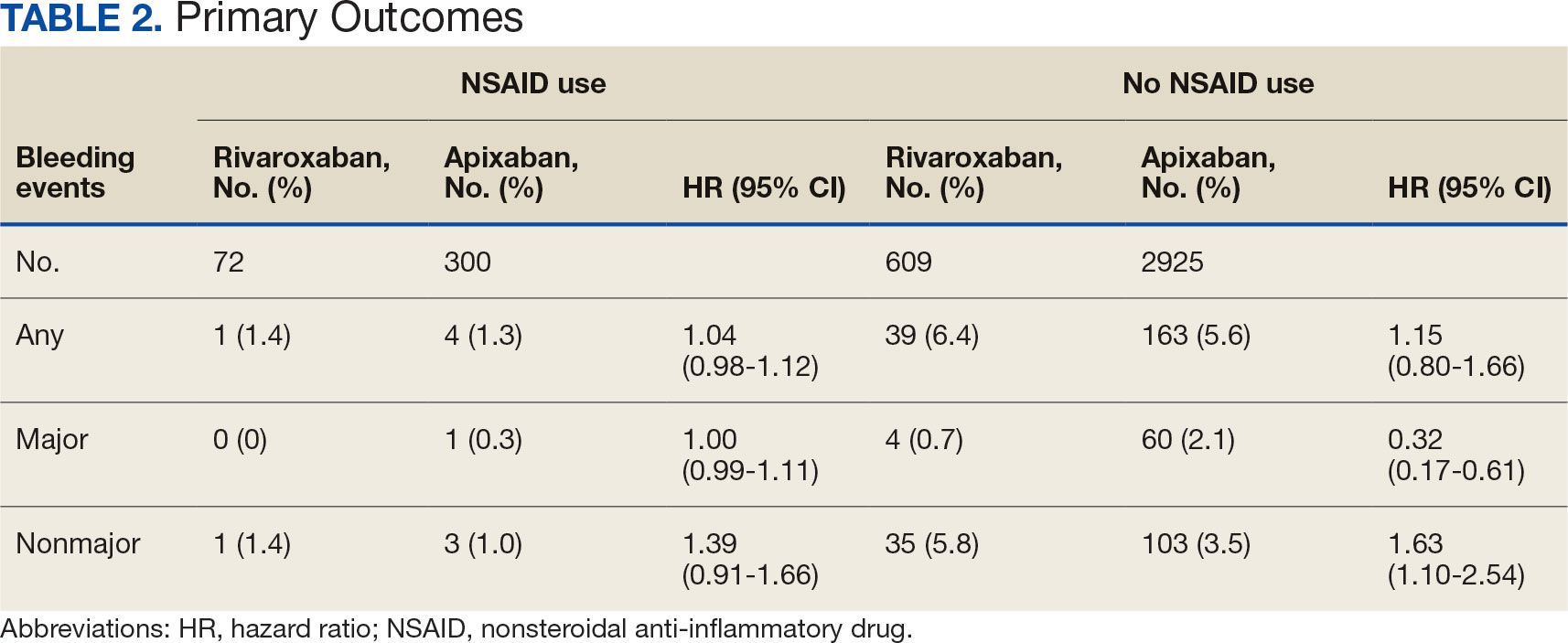

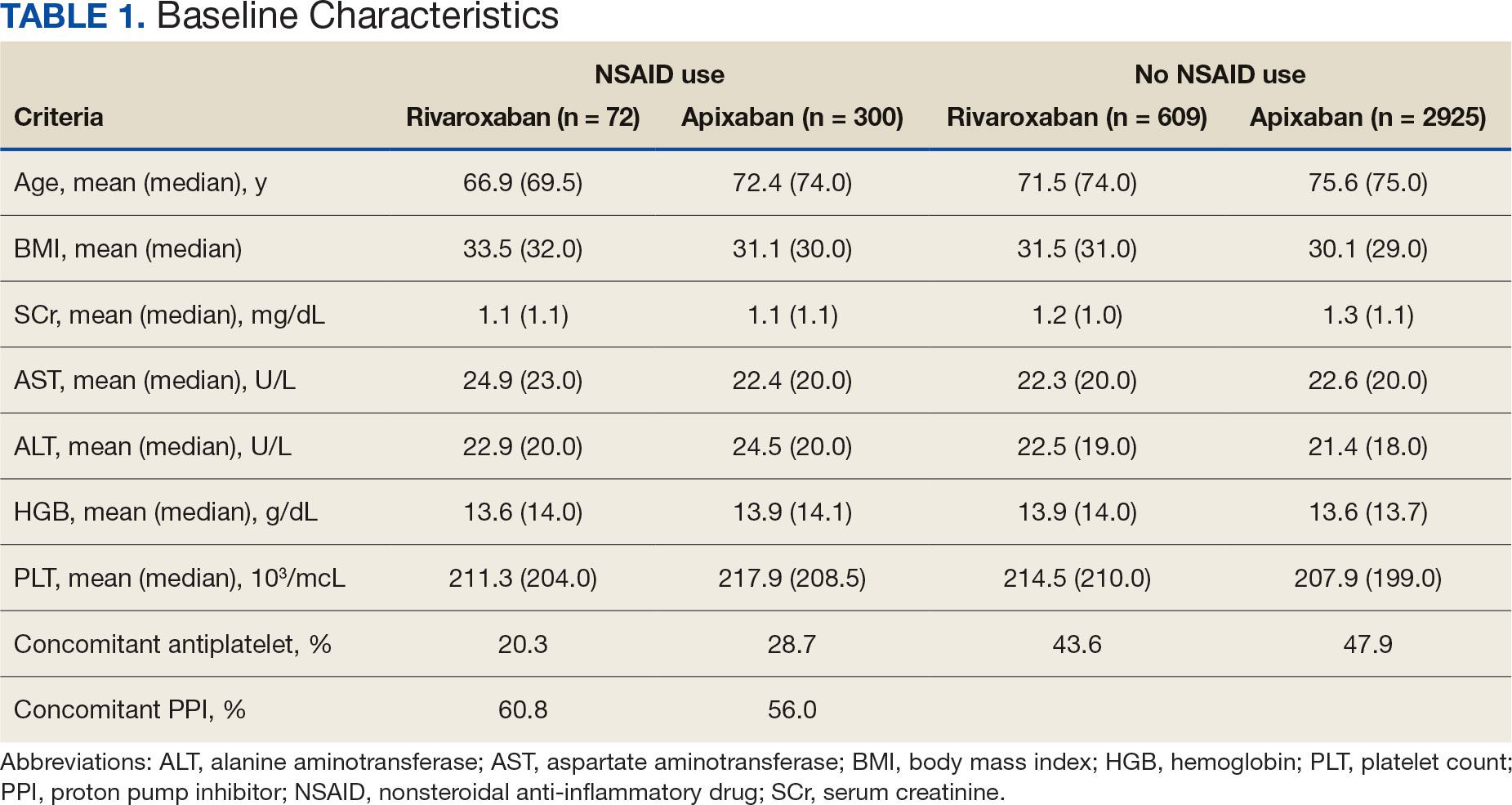

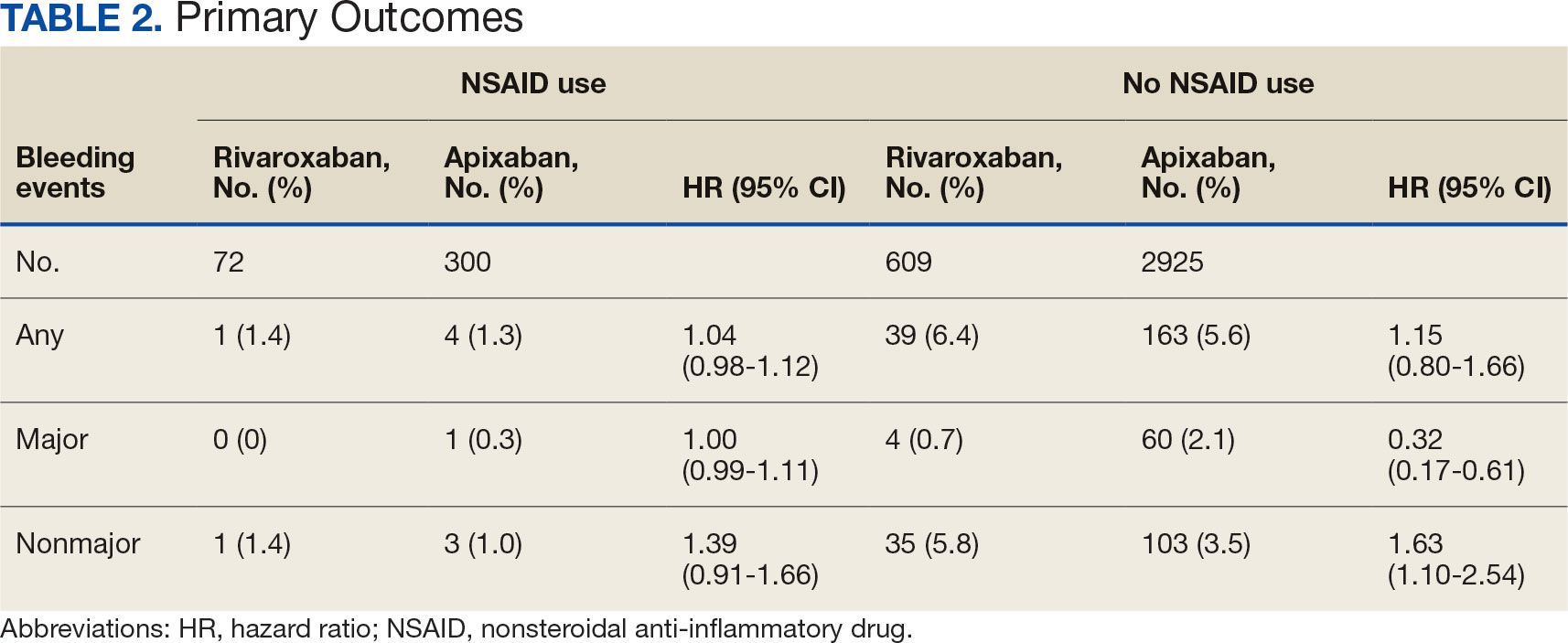

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Clinical practice has shifted from vitamin K antagonists to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for atrial fibrillation treatment due to their more favorable risk-benefit profile and less lifestyle modification required.1,2 However, the advantage of a lower bleeding risk with DOACs could be compromised by potentially problematic pharmacokinetic interactions like those conferred by antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3,4 Treating a patient needing anticoagulation with a DOAC who has comorbidities may introduce unavoidable drug-drug interactions. This particularly happens with over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs used for the management of pain and inflammatory conditions.5

NSAIDs primarily affect 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme isomers, COX-1 and COX-2.6 COX-1 helps maintain gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa integrity and platelet aggregation processes, whereas COX-2 is engaged in pain signaling and inflammation mediation. COX-1 inhibition is associated with more bleeding-related adverse events (AEs), especially in the GI tract. COX-2 inhibition is thought to provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties without elevating bleeding risk. This premise is responsible for the preferential use of celecoxib, a COX-2 selective NSAID, which should confer a lower bleeding risk compared to nonselective NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen.7 NSAIDs have been documented as independent risk factors for bleeding. NSAID users are about 3 times as likely to develop GI AEs compared to nonNSAID users.8