User login

AGA President Brings Forth “Message Of Inclusivity”

“I was always interested in medicine. From a relatively early age I thought that’s what I would be doing,” said Dr. Kim. When his father became disillusioned with his own career as a pathologist, he encouraged his son to look in other directions.

“In college I had the opportunity to study and learn broadly and I became interested in public policy and eventually majored in that discipline,” he said.

The mentorship of the late Uwe Reinhardt, a well-respected health economist at Princeton University, had a major impact on Dr. Kim during his senior year of college. Reinhardt told him that physicians are afforded a special position in society. “They have a moral responsibility to take the lead in terms of guiding and shaping healthcare. His message made a big impression upon me,” said Dr. Kim.

Ultimately, he decided to go into clinical medicine, but maintained his interest in healthcare policy. Experiences outside of the standard approach to medicine “helped me stay in the big picture of healthcare, to make a difference beyond just my individual patients. And that’s played a big part in keeping me involved in organized medicine,” said Dr. Kim, who began his term as AGA president in May 2025.

Dr. Kim is also a partner at South Denver Gastroenterology, a 33-provider, independent gastroenterology practice in Colorado. As the first physician in Colorado with fellowship training in endoscopic ultrasound, he introduced this service line into South Denver’s advanced endoscopy practice.

Dr. Kim has served in numerous roles with AGA, among them the co-director of the AGA Clinical Congress, the Partners in Quality program, and the Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Course. He is a Digestive Disease Week® abstract reviewer, has served as AGA representative to the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care and to the Alliance of Specialty Medicine. He has also served on the AGA Governing Board as clinical private practice councilor and secretary treasurer.

He discussed the high points of his career in an interview, revealing his plans as AGA president for unifying the sectors of GI medicine and fostering GI innovation and technology.

As the new AGA president, what are your goals for the society?

Dr. Kim: I want to put out a message of inclusivity. I think what’s special about AGA is that we’re the society for all gastroenterologists. Among all the other GI organizations, I think we really have the biggest tent and we work to unite clinicians, educators, and researchers – all gastroenterologists, regardless of their individual practice situation. These days, there is a tendency toward tribalism. People are starting to gravitate toward limiting their interactions to others that are from the same backgrounds. But as gastroenterologists we have more that unites us than divides us. It’s only by working together that we can make things better for everyone.

I think the second point is that we’re on the cusp of some important transformations in gastroenterology. The screening colonoscopy model that has sustained our specialty for decades is rapidly evolving. In addition, there is an increasing ability for patients as consumers to direct their own care through advances in technology, such as virtual health platforms. We’re seeing this as patients increasingly adopt things like complementary and alternative medicine outside of the standard model of physician-directed healthcare. These are two important trends that gastroenterologists need to be aware of and learn how to manage and to adapt to. I think AGA’s role is to help guide that evolution and to give physicians the tools to be able to respond.

We want to focus on innovation and we want to focus on practical solutions.

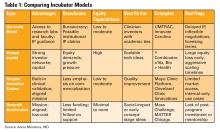

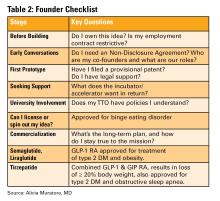

In terms of fostering innovation in gastroenterology, we’re the first medical professional society to create an incubator for new technologies. Not only do we provide that resource to our members, but we’re also putting our money where our mouth is. Through venture capital initiatives such as our GI Opportunity Fund, we directly invest in companies that we’re helping to develop.

On the practice side, we have been engaging directly with payers to foster improved communication and address pain points on both sides. I think we’re the only medical society that’s taking this type of approach and moving away from the traditional adversarial approach to dealing with payers. Recently, we had a very productive discussion with UnitedHealthcare around some of their upcoming formulary changes for inflammatory bowel disease. We used that opportunity to highlight how nonmedical switching between existing therapies can adversely impact patients, as well as increasing burden of red tape for practices.

Your practice was one of the original groups that formed the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DPHA). What accomplishments of the association are you most proud of?

Dr. Kim: DHPA formed about 10 years ago as an advocacy organization to combat a specific perceived threat, which was the in-office ancillary exception. This is the legislative pathway that allows gastroenterologists to provide ancillary services within their practice. An example of this is pathology for endoscopic procedures, which is an incredible value to patients and improves quality of care. This was under a significant legislative threat at that time. As independent physicians, DHPA took the lead in advocating against eliminating that exception.

I think the larger accomplishment was it demonstrated that gastroenterologists, specifically independent community practice gastroenterologists, could come together successfully and advocate for issues that were of importance to our specialty. AGA and DHPA have worked very well together, collaborating on shared policy interests and have worked closely on both legislative as well as regulatory issues. We’ve sponsored joint meetings that we’ve programmed together and we’re looking forward to continuing a robust partnership.

You have introduced several new clinical practice and practice management models. Can you discuss the part-time partnership model and what it has achieved?

Dr. Kim: Like many practices, South Denver Gastroenterology historically required physician partners to work full time. This conflicted with our desire and our need to attract more women gastroenterologists into our practice. The process involved careful analysis of our direct and indirect expenses, but more importantly it required a negotiation and a meeting of the minds among our partners. A lot of this ultimately came down to trust. It helped a great deal that our practice has always had strong cohesiveness. That helped us to build that trust that partners would stay engaged in the practice even if they worked part time.

Our practice has also always prioritized work-life balance. We were able to come up with a formula that allows partners to work three days per week, retaining their partnership interest and their participation in practice decisions. They stay involved but are also financially sustainable for the practice. It’s been very successful. It’s been a big draw, not just for women, but it has allowed us to create a situation where women are fully one third of our partnership. It’s something we’re all extremely proud of.

How did you get involved in AGA?

Dr. Kim: One of the first projects I participated in was the Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. This was an initiative to help prepare GI practices for value-based care. We did things like develop quality measure sets for GI conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and hepatitis C. We published a bundled payment model for screening colonoscopies. We also created a model for obesity management by gastroenterologists. This was 15 years ago, and I think it was about 15 years ahead of its time! It’s interesting to see how many of these changes in GI practice that we envisioned are slowly coming to pass.

I saw that AGA was interested in me as a community-based clinician. They focused on trying to develop those practical tools to help me succeed. It’s one of the reasons I’ve stayed engaged.

What is your approach to patient communication and education?

Dr. Kim: There are two things that I always tell both my staff as well as young people who come to me asking for advice. I think the first and most important is that you should always strive to treat your patients the way that you would want your family treated. Of course, we’re not perfect, but when that doesn’t happen, look at your behavior, the way that you’re interacting, but also the way the system is treating your patients and try to improve things within your own practice. And then the other thing that I tell folks is try to spend more time listening to your patients than talking or speaking at them.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about GI?

Dr. Kim: We’re not just about colonoscopies! I went into GI not just because I enjoy performing procedures, but because our specialty covers such a broad spectrum of physiology and diseases. We also have the ability as gastroenterologists to develop long-term relationships with our patients. I’ve been in practice now more than 25 years, and the greatest satisfaction in my career doesn’t come from the endoscopy center, although I still enjoy performing procedures. It comes from the clinic; it comes from the patients whom I’ve known for decades, and the interaction and conversations that I can have with them, the ability to see their families, their parents, and now in some cases their kids or even their grandkids. It’s incredibly satisfying. It makes my job fun.

What advice would you give to aspiring medical students?

Dr. Kim: One of the things I would say is stay involved in organized medicine. As physicians, we are endowed with great trust. We also have a great responsibility to help shape our healthcare care system. If we work together, we really can make a difference, not just for our profession, but also for society at large and for the patients whom we serve.

I really hope that young people don’t lose their optimism. We hear a lot these days about how much negativity and pessimism there is about the future, especially among young people in our society. But I think it’s a great time to be in medicine. Advances in medical science have made huge strides in our ability to make real differences for our patients. And the pace of technology progress is only going to continue to accelerate. Sure, there are lots of shortcomings in the practice of medicine, but honestly, that’s always been the case. I have faith that as a profession, we are smart people, we’re committed people, and we will be successful in overcoming those challenges. That’s the message that I have for young folks.

Lightning Round

Coffee or tea?

Coffee, black

What’s one hobby you’d like to pick up?

Anything except pickleball

What’s your favorite season of the year?

Winter, I’m a skier

What’s your favorite way to spend a weekend?

Doing anything outside

If you could have dinner with any historical figure, who would it be?

Ben Franklin

What’s your go-to karaoke song?

You don’t want to hear me sing

What’s one thing on your bucket list?

Skiing in South America

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Follow your heart

“I was always interested in medicine. From a relatively early age I thought that’s what I would be doing,” said Dr. Kim. When his father became disillusioned with his own career as a pathologist, he encouraged his son to look in other directions.

“In college I had the opportunity to study and learn broadly and I became interested in public policy and eventually majored in that discipline,” he said.

The mentorship of the late Uwe Reinhardt, a well-respected health economist at Princeton University, had a major impact on Dr. Kim during his senior year of college. Reinhardt told him that physicians are afforded a special position in society. “They have a moral responsibility to take the lead in terms of guiding and shaping healthcare. His message made a big impression upon me,” said Dr. Kim.

Ultimately, he decided to go into clinical medicine, but maintained his interest in healthcare policy. Experiences outside of the standard approach to medicine “helped me stay in the big picture of healthcare, to make a difference beyond just my individual patients. And that’s played a big part in keeping me involved in organized medicine,” said Dr. Kim, who began his term as AGA president in May 2025.

Dr. Kim is also a partner at South Denver Gastroenterology, a 33-provider, independent gastroenterology practice in Colorado. As the first physician in Colorado with fellowship training in endoscopic ultrasound, he introduced this service line into South Denver’s advanced endoscopy practice.

Dr. Kim has served in numerous roles with AGA, among them the co-director of the AGA Clinical Congress, the Partners in Quality program, and the Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Course. He is a Digestive Disease Week® abstract reviewer, has served as AGA representative to the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care and to the Alliance of Specialty Medicine. He has also served on the AGA Governing Board as clinical private practice councilor and secretary treasurer.

He discussed the high points of his career in an interview, revealing his plans as AGA president for unifying the sectors of GI medicine and fostering GI innovation and technology.

As the new AGA president, what are your goals for the society?

Dr. Kim: I want to put out a message of inclusivity. I think what’s special about AGA is that we’re the society for all gastroenterologists. Among all the other GI organizations, I think we really have the biggest tent and we work to unite clinicians, educators, and researchers – all gastroenterologists, regardless of their individual practice situation. These days, there is a tendency toward tribalism. People are starting to gravitate toward limiting their interactions to others that are from the same backgrounds. But as gastroenterologists we have more that unites us than divides us. It’s only by working together that we can make things better for everyone.

I think the second point is that we’re on the cusp of some important transformations in gastroenterology. The screening colonoscopy model that has sustained our specialty for decades is rapidly evolving. In addition, there is an increasing ability for patients as consumers to direct their own care through advances in technology, such as virtual health platforms. We’re seeing this as patients increasingly adopt things like complementary and alternative medicine outside of the standard model of physician-directed healthcare. These are two important trends that gastroenterologists need to be aware of and learn how to manage and to adapt to. I think AGA’s role is to help guide that evolution and to give physicians the tools to be able to respond.

We want to focus on innovation and we want to focus on practical solutions.

In terms of fostering innovation in gastroenterology, we’re the first medical professional society to create an incubator for new technologies. Not only do we provide that resource to our members, but we’re also putting our money where our mouth is. Through venture capital initiatives such as our GI Opportunity Fund, we directly invest in companies that we’re helping to develop.

On the practice side, we have been engaging directly with payers to foster improved communication and address pain points on both sides. I think we’re the only medical society that’s taking this type of approach and moving away from the traditional adversarial approach to dealing with payers. Recently, we had a very productive discussion with UnitedHealthcare around some of their upcoming formulary changes for inflammatory bowel disease. We used that opportunity to highlight how nonmedical switching between existing therapies can adversely impact patients, as well as increasing burden of red tape for practices.

Your practice was one of the original groups that formed the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DPHA). What accomplishments of the association are you most proud of?

Dr. Kim: DHPA formed about 10 years ago as an advocacy organization to combat a specific perceived threat, which was the in-office ancillary exception. This is the legislative pathway that allows gastroenterologists to provide ancillary services within their practice. An example of this is pathology for endoscopic procedures, which is an incredible value to patients and improves quality of care. This was under a significant legislative threat at that time. As independent physicians, DHPA took the lead in advocating against eliminating that exception.

I think the larger accomplishment was it demonstrated that gastroenterologists, specifically independent community practice gastroenterologists, could come together successfully and advocate for issues that were of importance to our specialty. AGA and DHPA have worked very well together, collaborating on shared policy interests and have worked closely on both legislative as well as regulatory issues. We’ve sponsored joint meetings that we’ve programmed together and we’re looking forward to continuing a robust partnership.

You have introduced several new clinical practice and practice management models. Can you discuss the part-time partnership model and what it has achieved?

Dr. Kim: Like many practices, South Denver Gastroenterology historically required physician partners to work full time. This conflicted with our desire and our need to attract more women gastroenterologists into our practice. The process involved careful analysis of our direct and indirect expenses, but more importantly it required a negotiation and a meeting of the minds among our partners. A lot of this ultimately came down to trust. It helped a great deal that our practice has always had strong cohesiveness. That helped us to build that trust that partners would stay engaged in the practice even if they worked part time.

Our practice has also always prioritized work-life balance. We were able to come up with a formula that allows partners to work three days per week, retaining their partnership interest and their participation in practice decisions. They stay involved but are also financially sustainable for the practice. It’s been very successful. It’s been a big draw, not just for women, but it has allowed us to create a situation where women are fully one third of our partnership. It’s something we’re all extremely proud of.

How did you get involved in AGA?

Dr. Kim: One of the first projects I participated in was the Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. This was an initiative to help prepare GI practices for value-based care. We did things like develop quality measure sets for GI conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and hepatitis C. We published a bundled payment model for screening colonoscopies. We also created a model for obesity management by gastroenterologists. This was 15 years ago, and I think it was about 15 years ahead of its time! It’s interesting to see how many of these changes in GI practice that we envisioned are slowly coming to pass.

I saw that AGA was interested in me as a community-based clinician. They focused on trying to develop those practical tools to help me succeed. It’s one of the reasons I’ve stayed engaged.

What is your approach to patient communication and education?

Dr. Kim: There are two things that I always tell both my staff as well as young people who come to me asking for advice. I think the first and most important is that you should always strive to treat your patients the way that you would want your family treated. Of course, we’re not perfect, but when that doesn’t happen, look at your behavior, the way that you’re interacting, but also the way the system is treating your patients and try to improve things within your own practice. And then the other thing that I tell folks is try to spend more time listening to your patients than talking or speaking at them.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about GI?

Dr. Kim: We’re not just about colonoscopies! I went into GI not just because I enjoy performing procedures, but because our specialty covers such a broad spectrum of physiology and diseases. We also have the ability as gastroenterologists to develop long-term relationships with our patients. I’ve been in practice now more than 25 years, and the greatest satisfaction in my career doesn’t come from the endoscopy center, although I still enjoy performing procedures. It comes from the clinic; it comes from the patients whom I’ve known for decades, and the interaction and conversations that I can have with them, the ability to see their families, their parents, and now in some cases their kids or even their grandkids. It’s incredibly satisfying. It makes my job fun.

What advice would you give to aspiring medical students?

Dr. Kim: One of the things I would say is stay involved in organized medicine. As physicians, we are endowed with great trust. We also have a great responsibility to help shape our healthcare care system. If we work together, we really can make a difference, not just for our profession, but also for society at large and for the patients whom we serve.

I really hope that young people don’t lose their optimism. We hear a lot these days about how much negativity and pessimism there is about the future, especially among young people in our society. But I think it’s a great time to be in medicine. Advances in medical science have made huge strides in our ability to make real differences for our patients. And the pace of technology progress is only going to continue to accelerate. Sure, there are lots of shortcomings in the practice of medicine, but honestly, that’s always been the case. I have faith that as a profession, we are smart people, we’re committed people, and we will be successful in overcoming those challenges. That’s the message that I have for young folks.

Lightning Round

Coffee or tea?

Coffee, black

What’s one hobby you’d like to pick up?

Anything except pickleball

What’s your favorite season of the year?

Winter, I’m a skier

What’s your favorite way to spend a weekend?

Doing anything outside

If you could have dinner with any historical figure, who would it be?

Ben Franklin

What’s your go-to karaoke song?

You don’t want to hear me sing

What’s one thing on your bucket list?

Skiing in South America

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Follow your heart

“I was always interested in medicine. From a relatively early age I thought that’s what I would be doing,” said Dr. Kim. When his father became disillusioned with his own career as a pathologist, he encouraged his son to look in other directions.

“In college I had the opportunity to study and learn broadly and I became interested in public policy and eventually majored in that discipline,” he said.

The mentorship of the late Uwe Reinhardt, a well-respected health economist at Princeton University, had a major impact on Dr. Kim during his senior year of college. Reinhardt told him that physicians are afforded a special position in society. “They have a moral responsibility to take the lead in terms of guiding and shaping healthcare. His message made a big impression upon me,” said Dr. Kim.

Ultimately, he decided to go into clinical medicine, but maintained his interest in healthcare policy. Experiences outside of the standard approach to medicine “helped me stay in the big picture of healthcare, to make a difference beyond just my individual patients. And that’s played a big part in keeping me involved in organized medicine,” said Dr. Kim, who began his term as AGA president in May 2025.

Dr. Kim is also a partner at South Denver Gastroenterology, a 33-provider, independent gastroenterology practice in Colorado. As the first physician in Colorado with fellowship training in endoscopic ultrasound, he introduced this service line into South Denver’s advanced endoscopy practice.

Dr. Kim has served in numerous roles with AGA, among them the co-director of the AGA Clinical Congress, the Partners in Quality program, and the Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Course. He is a Digestive Disease Week® abstract reviewer, has served as AGA representative to the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care and to the Alliance of Specialty Medicine. He has also served on the AGA Governing Board as clinical private practice councilor and secretary treasurer.

He discussed the high points of his career in an interview, revealing his plans as AGA president for unifying the sectors of GI medicine and fostering GI innovation and technology.

As the new AGA president, what are your goals for the society?

Dr. Kim: I want to put out a message of inclusivity. I think what’s special about AGA is that we’re the society for all gastroenterologists. Among all the other GI organizations, I think we really have the biggest tent and we work to unite clinicians, educators, and researchers – all gastroenterologists, regardless of their individual practice situation. These days, there is a tendency toward tribalism. People are starting to gravitate toward limiting their interactions to others that are from the same backgrounds. But as gastroenterologists we have more that unites us than divides us. It’s only by working together that we can make things better for everyone.

I think the second point is that we’re on the cusp of some important transformations in gastroenterology. The screening colonoscopy model that has sustained our specialty for decades is rapidly evolving. In addition, there is an increasing ability for patients as consumers to direct their own care through advances in technology, such as virtual health platforms. We’re seeing this as patients increasingly adopt things like complementary and alternative medicine outside of the standard model of physician-directed healthcare. These are two important trends that gastroenterologists need to be aware of and learn how to manage and to adapt to. I think AGA’s role is to help guide that evolution and to give physicians the tools to be able to respond.

We want to focus on innovation and we want to focus on practical solutions.

In terms of fostering innovation in gastroenterology, we’re the first medical professional society to create an incubator for new technologies. Not only do we provide that resource to our members, but we’re also putting our money where our mouth is. Through venture capital initiatives such as our GI Opportunity Fund, we directly invest in companies that we’re helping to develop.

On the practice side, we have been engaging directly with payers to foster improved communication and address pain points on both sides. I think we’re the only medical society that’s taking this type of approach and moving away from the traditional adversarial approach to dealing with payers. Recently, we had a very productive discussion with UnitedHealthcare around some of their upcoming formulary changes for inflammatory bowel disease. We used that opportunity to highlight how nonmedical switching between existing therapies can adversely impact patients, as well as increasing burden of red tape for practices.

Your practice was one of the original groups that formed the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DPHA). What accomplishments of the association are you most proud of?

Dr. Kim: DHPA formed about 10 years ago as an advocacy organization to combat a specific perceived threat, which was the in-office ancillary exception. This is the legislative pathway that allows gastroenterologists to provide ancillary services within their practice. An example of this is pathology for endoscopic procedures, which is an incredible value to patients and improves quality of care. This was under a significant legislative threat at that time. As independent physicians, DHPA took the lead in advocating against eliminating that exception.

I think the larger accomplishment was it demonstrated that gastroenterologists, specifically independent community practice gastroenterologists, could come together successfully and advocate for issues that were of importance to our specialty. AGA and DHPA have worked very well together, collaborating on shared policy interests and have worked closely on both legislative as well as regulatory issues. We’ve sponsored joint meetings that we’ve programmed together and we’re looking forward to continuing a robust partnership.

You have introduced several new clinical practice and practice management models. Can you discuss the part-time partnership model and what it has achieved?

Dr. Kim: Like many practices, South Denver Gastroenterology historically required physician partners to work full time. This conflicted with our desire and our need to attract more women gastroenterologists into our practice. The process involved careful analysis of our direct and indirect expenses, but more importantly it required a negotiation and a meeting of the minds among our partners. A lot of this ultimately came down to trust. It helped a great deal that our practice has always had strong cohesiveness. That helped us to build that trust that partners would stay engaged in the practice even if they worked part time.

Our practice has also always prioritized work-life balance. We were able to come up with a formula that allows partners to work three days per week, retaining their partnership interest and their participation in practice decisions. They stay involved but are also financially sustainable for the practice. It’s been very successful. It’s been a big draw, not just for women, but it has allowed us to create a situation where women are fully one third of our partnership. It’s something we’re all extremely proud of.

How did you get involved in AGA?

Dr. Kim: One of the first projects I participated in was the Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. This was an initiative to help prepare GI practices for value-based care. We did things like develop quality measure sets for GI conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and hepatitis C. We published a bundled payment model for screening colonoscopies. We also created a model for obesity management by gastroenterologists. This was 15 years ago, and I think it was about 15 years ahead of its time! It’s interesting to see how many of these changes in GI practice that we envisioned are slowly coming to pass.

I saw that AGA was interested in me as a community-based clinician. They focused on trying to develop those practical tools to help me succeed. It’s one of the reasons I’ve stayed engaged.

What is your approach to patient communication and education?

Dr. Kim: There are two things that I always tell both my staff as well as young people who come to me asking for advice. I think the first and most important is that you should always strive to treat your patients the way that you would want your family treated. Of course, we’re not perfect, but when that doesn’t happen, look at your behavior, the way that you’re interacting, but also the way the system is treating your patients and try to improve things within your own practice. And then the other thing that I tell folks is try to spend more time listening to your patients than talking or speaking at them.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about GI?

Dr. Kim: We’re not just about colonoscopies! I went into GI not just because I enjoy performing procedures, but because our specialty covers such a broad spectrum of physiology and diseases. We also have the ability as gastroenterologists to develop long-term relationships with our patients. I’ve been in practice now more than 25 years, and the greatest satisfaction in my career doesn’t come from the endoscopy center, although I still enjoy performing procedures. It comes from the clinic; it comes from the patients whom I’ve known for decades, and the interaction and conversations that I can have with them, the ability to see their families, their parents, and now in some cases their kids or even their grandkids. It’s incredibly satisfying. It makes my job fun.

What advice would you give to aspiring medical students?

Dr. Kim: One of the things I would say is stay involved in organized medicine. As physicians, we are endowed with great trust. We also have a great responsibility to help shape our healthcare care system. If we work together, we really can make a difference, not just for our profession, but also for society at large and for the patients whom we serve.

I really hope that young people don’t lose their optimism. We hear a lot these days about how much negativity and pessimism there is about the future, especially among young people in our society. But I think it’s a great time to be in medicine. Advances in medical science have made huge strides in our ability to make real differences for our patients. And the pace of technology progress is only going to continue to accelerate. Sure, there are lots of shortcomings in the practice of medicine, but honestly, that’s always been the case. I have faith that as a profession, we are smart people, we’re committed people, and we will be successful in overcoming those challenges. That’s the message that I have for young folks.

Lightning Round

Coffee or tea?

Coffee, black

What’s one hobby you’d like to pick up?

Anything except pickleball

What’s your favorite season of the year?

Winter, I’m a skier

What’s your favorite way to spend a weekend?

Doing anything outside

If you could have dinner with any historical figure, who would it be?

Ben Franklin

What’s your go-to karaoke song?

You don’t want to hear me sing

What’s one thing on your bucket list?

Skiing in South America

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Follow your heart

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

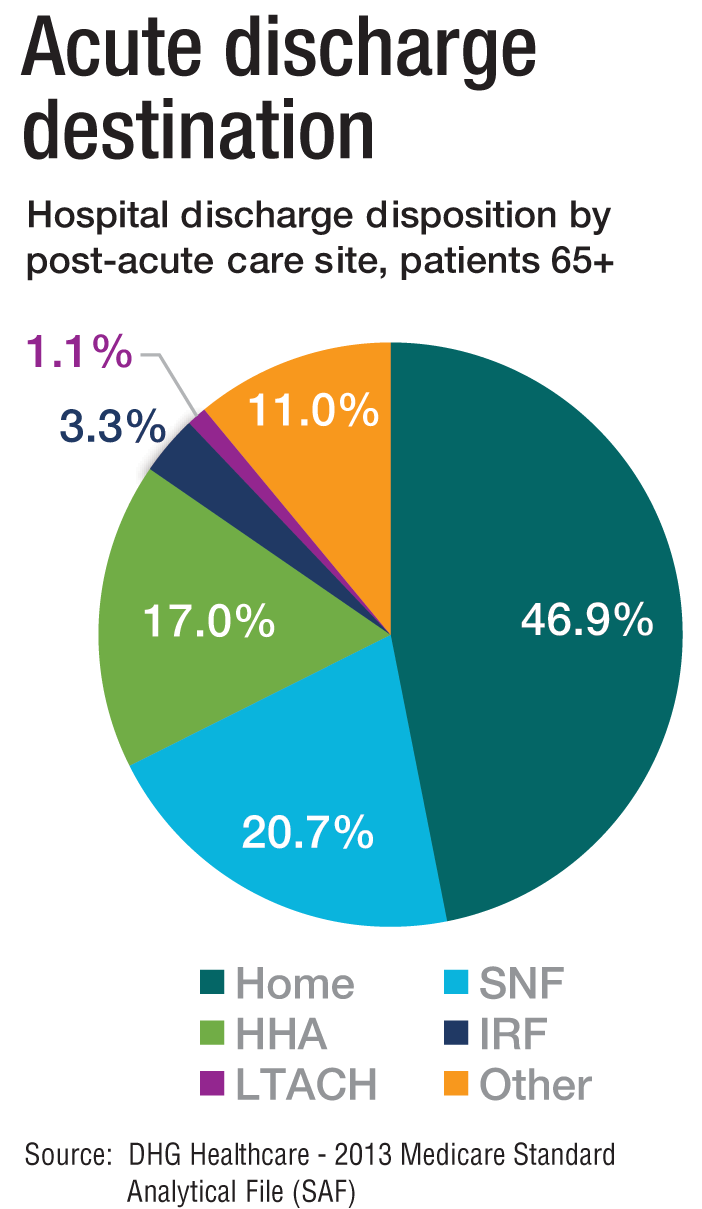

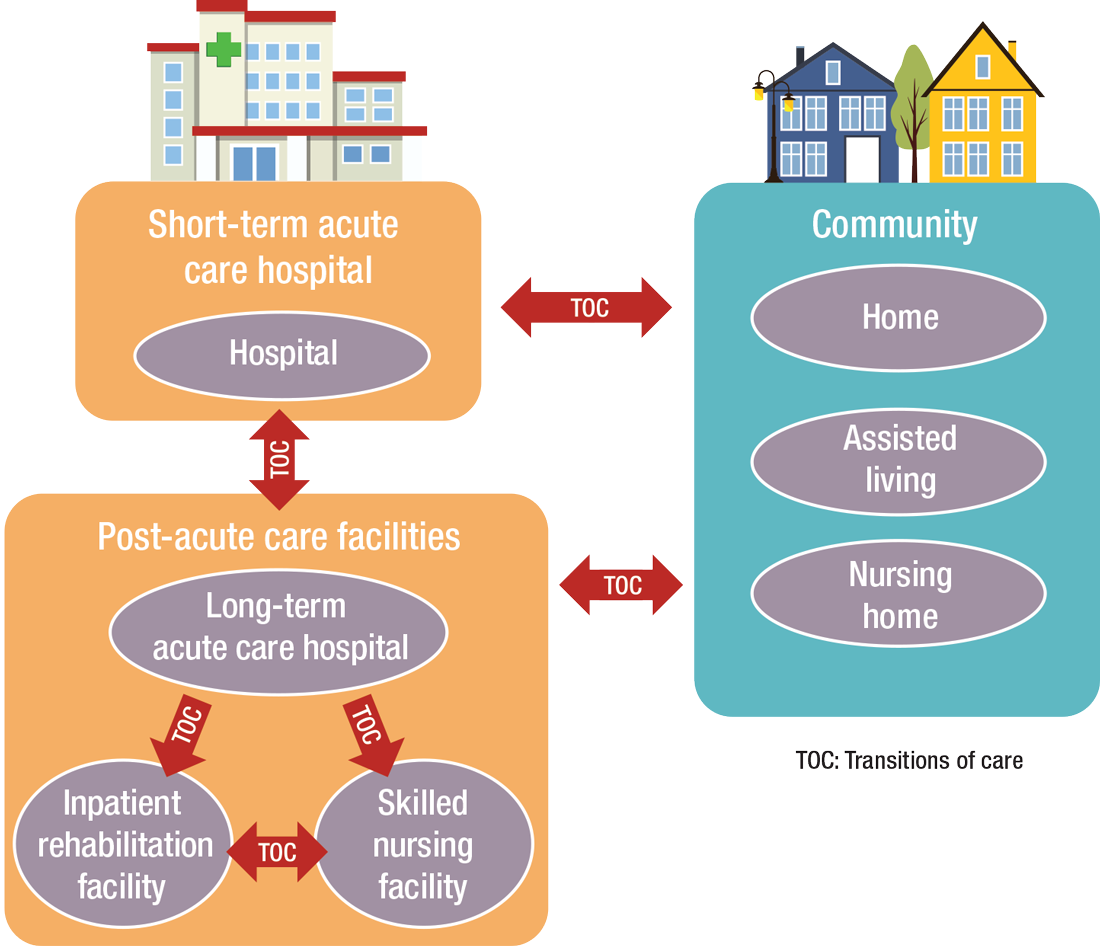

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Special Report II: Tackling Burnout

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81