User login

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

PRACTICE POINTS

- Direct care practices may be the new horizon of health care.

- Starting a direct care practice offers autonomy but demands entrepreneurial readiness.

- New dermatologists can enjoy control over scheduling, pricing, and patient care, but success requires business acumen, financial planning, and comfort with risk.

Letter: Another View on Private Equity in GI

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

An October 1 article in GI & Hepatology News cautioned physicians against partnering with private equity firms, warning that they target “quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care.”

But several recent studies – and my own experience – show that .

A 2024 study conducted by Avalere Health found that per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated practice model to a PE-affiliated model declined by $963 in the 12 months following the transition. By contrast, per-beneficiary Medicare expenditures for physicians who shifted from an unaffiliated model to a hospital-affiliated one increased more than $1,300.

A 2025 peer-reviewed study published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy found that physicians affiliated with private equity were far more likely to perform common high-volume procedures in the lowest-cost site of care – an ambulatory surgery center or medical office – than in higher-cost hospital outpatient departments. Physicians affiliated with hospitals were far more likely to perform procedures in HOPDs.

Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization has enabled my practice to afford advanced technologies we never could have deployed on our own. Those technologies have helped improve our polyp detection rates, reduce the incidence of colon cancer, and more efficiently care for patients with ulcerative colitis. We also now provide patients seamless access to digital platforms that help them better manage chronic conditions.

Independent medical practice is under duress. Partnering with a private equity-backed management services organization is one of the most effective ways for a physician practice to retain its independence – and continue offering patients affordable, high-quality care.

George Dickstein, MD, AGAF, is senior vice president of clinical affairs, Massachusetts, for Gastro Health, and chairperson of Gastro Health’s Physician Leadership Council. He is based in Framingham, Mass. GI & Hepatology News encourages readers to submit letters to the editor to debate topics raised in the newspaper.

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

What are the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD’s) top advocacy priorities related to Medicare physician reimbursement?

Dr. Taylor: Medicare physician payment has failed to keep up with inflation, threatening the viability of medical practices. The AAD urges Congress to stabilize the Medicare payment system to ensure continued patient access to essential health care by

What is the AAD’s stance on transitioning from traditional fee-for-service to value-based care models in dermatology under Medicare?

Dr. Taylor: Current value-based programs are extremely burdensome, have not demonstrated improved patient care, and are not clinically relevant to physicians or patients. The AAD has serious concerns about the viability and effectiveness of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), especially the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Numerous studies have highlighted persistent challenges associated with MIPS, including practices serving high-risk patients and those that are small or in rural areas. For instance, researchers examined whether MIPS disproportionately penalized surgeons who care for these patients and found a connection between caring for these patients, lower MIPS scores, and a higher likelihood of facing negative payment adjustments.

Additionally, the US Government Accountability Office was tasked with reviewing several aspects concerning small and rural practices in relation to Medicare payment incentive programs, including MIPS. Findings indicated that physician practices with 15 or fewer providers, whether located in rural or nonrural areas, had a higher likelihood of receiving negative payment adjustments in Medicare incentive programs compared to larger practices. To maximize participation and facilitate the best possible outcomes for dermatologists within the MIPS program, the AAD maintains that we must continue to develop and advocate that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approve dermatology-specific measures for MIPS reporting.

Does the AAD have plans to develop or expand dermatology-specific quality measures that are more clinically relevant and less administratively taxing?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is committed to ensuring that dermatologists can be successful in the QPP and its MIPS Value Pathways and Advanced Alternative Payment Model programs. These payment pathways for QPP-eligible participants allow physicians to increase their future Medicare reimbursements but also penalize those who do not meet performance objectives. The AAD is constantly reviewing and proposing new dermatology-specific quality measures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services based on member feedback to reduce administrative burdens of MIPS reporting. All of our quality measures are developed by dermatologists for dermatologists.

How is the AAD supporting practices dealing with insurer-mandated switch policies that disrupt continuity of care and increase documentation burden?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD works with private payers to alleviate administrative burdens for dermatologists, maintain appropriate reimbursement for services provided, and ensure patients can access covered quality care by building and maintaining relationships with public and private payers. This critical collaboration addresses immediate needs affecting our members’ ability to deliver care, such as when policy changes affect claims and formulary coverage or payment. Our coordinated strategy ensures payer policies align with everyday practice for dermatologists so they can focus on treating patients. The AAD has resources and tools to guide dermatology practices in appropriate documentation and coding.

What initiatives is the AAD pursuing to specifically support independent or small dermatology practices in coping with administrative overload?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is continuously advocating for our small and independent dermatology practices. In every comment letter we submit on proposed medical practice reporting regulation, we demand small practice exemptions. Moreover, the AAD has resources and practical tools for all types of practices to cope with administrative burdens, including MIPS reporting requirements. These resources and tools were created by dermatologists for dermatologists to take the guesswork out of administrative compliance. DataDerm is the AAD’s clinical data registry used for MIPS reporting. Since its launch in 2016, DataDerm has become dermatology’s largest clinical data registry, capturing information on more than 16 million unique patients and 69 million encounters. It supports the advancement of skin disease diagnosis and treatment, informs clinical practice, streamlines MIPS reporting, and drives clinically relevant research using real-world data.

What are the biggest contributors to physician burnout right now? What resources does AAD offer to support dermatologists in managing burnout?

Dr. Taylor: The biggest contributors to burnout that dermatologists are facing are demanding workloads, administrative burdens, and loss of autonomy. Dermatologists welcome medical challenges, but they face growing administrative and regulatory burdens that take time away from patient care and contribute to burnout. Taking a wellness-centered approach can help, which is why the AAD includes both practical tools to reduce burdens and strategies to sustain your practice in its online resources. The burnout and wellness section of the AAD website can help with administrative burdens, building a supportive work culture, recognizing drivers of burnout, reconnecting with your purpose, and more.

How is the AAD working to ensure that the expanding scope of practice does not compromise patient safety, particularly when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of complex skin cancers or prescribing systemic medications?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD advocates to ensure that each member of the care team is practicing at a level consistent with their training and education and opposes scope-of-practice expansions for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other nonphysician clinicians that threaten patient safety by allowing them to practice independently and advertise as skin experts. Each state has its own scope-of-practice laws governing what nonphysicians can do, whether supervision is required, and how they can represent their training, both in advertising and in a medical practice. The AAD supports appropriate safeguards to ensure patient safety and a focus on the highest-quality appropriate care as the nonphysician workforce expands. The AAD encourages patients to report adverse outcomes to the appropriate state licensing boards.

Is the AAD developing or recommending best practices for dermatologists who supervise NPs or PAs, especially in large practices or retail clinics where oversight can be inconsistent?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD firmly believes that the optimal quality of medical care is delivered when a qualified and licensed physician provides direct on-site supervision to all qualified nonphysician personnel. A medical director of a medical spa facility should be a physician licensed in the state where the facility is located and also should be clearly identified by state licensure and any state-recognized board certification as well as by medical specialty, training, and education. The individual also should be identified as the medical director in all marketing materials and on websites and social media accounts related to the medical spa facility. The AAD would like to see policies that would provide increased transparency in state licensure and specialty board certification including requiring disclosure that a physician is certified or eligible for certification by a private or public board, parent association, or multidisciplinary board or association; requiring disclosure of the certifying board or association with one’s field of study or specialty; requiring display of visible identification—including one’s state licensure, professional degree, field of study, and the use of clarifying titles—in facilities, in marketing materials, and on websites and social media; and requiring all personnel in private medical practices, hospitals, clinics, or other settings employing physicians and/or other personnel that offer medical, surgical, or aesthetic procedures to wear a photo identification name tag during all patient encounters.

What are the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD’s) top advocacy priorities related to Medicare physician reimbursement?

Dr. Taylor: Medicare physician payment has failed to keep up with inflation, threatening the viability of medical practices. The AAD urges Congress to stabilize the Medicare payment system to ensure continued patient access to essential health care by

What is the AAD’s stance on transitioning from traditional fee-for-service to value-based care models in dermatology under Medicare?

Dr. Taylor: Current value-based programs are extremely burdensome, have not demonstrated improved patient care, and are not clinically relevant to physicians or patients. The AAD has serious concerns about the viability and effectiveness of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), especially the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Numerous studies have highlighted persistent challenges associated with MIPS, including practices serving high-risk patients and those that are small or in rural areas. For instance, researchers examined whether MIPS disproportionately penalized surgeons who care for these patients and found a connection between caring for these patients, lower MIPS scores, and a higher likelihood of facing negative payment adjustments.

Additionally, the US Government Accountability Office was tasked with reviewing several aspects concerning small and rural practices in relation to Medicare payment incentive programs, including MIPS. Findings indicated that physician practices with 15 or fewer providers, whether located in rural or nonrural areas, had a higher likelihood of receiving negative payment adjustments in Medicare incentive programs compared to larger practices. To maximize participation and facilitate the best possible outcomes for dermatologists within the MIPS program, the AAD maintains that we must continue to develop and advocate that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approve dermatology-specific measures for MIPS reporting.

Does the AAD have plans to develop or expand dermatology-specific quality measures that are more clinically relevant and less administratively taxing?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is committed to ensuring that dermatologists can be successful in the QPP and its MIPS Value Pathways and Advanced Alternative Payment Model programs. These payment pathways for QPP-eligible participants allow physicians to increase their future Medicare reimbursements but also penalize those who do not meet performance objectives. The AAD is constantly reviewing and proposing new dermatology-specific quality measures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services based on member feedback to reduce administrative burdens of MIPS reporting. All of our quality measures are developed by dermatologists for dermatologists.

How is the AAD supporting practices dealing with insurer-mandated switch policies that disrupt continuity of care and increase documentation burden?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD works with private payers to alleviate administrative burdens for dermatologists, maintain appropriate reimbursement for services provided, and ensure patients can access covered quality care by building and maintaining relationships with public and private payers. This critical collaboration addresses immediate needs affecting our members’ ability to deliver care, such as when policy changes affect claims and formulary coverage or payment. Our coordinated strategy ensures payer policies align with everyday practice for dermatologists so they can focus on treating patients. The AAD has resources and tools to guide dermatology practices in appropriate documentation and coding.

What initiatives is the AAD pursuing to specifically support independent or small dermatology practices in coping with administrative overload?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is continuously advocating for our small and independent dermatology practices. In every comment letter we submit on proposed medical practice reporting regulation, we demand small practice exemptions. Moreover, the AAD has resources and practical tools for all types of practices to cope with administrative burdens, including MIPS reporting requirements. These resources and tools were created by dermatologists for dermatologists to take the guesswork out of administrative compliance. DataDerm is the AAD’s clinical data registry used for MIPS reporting. Since its launch in 2016, DataDerm has become dermatology’s largest clinical data registry, capturing information on more than 16 million unique patients and 69 million encounters. It supports the advancement of skin disease diagnosis and treatment, informs clinical practice, streamlines MIPS reporting, and drives clinically relevant research using real-world data.

What are the biggest contributors to physician burnout right now? What resources does AAD offer to support dermatologists in managing burnout?

Dr. Taylor: The biggest contributors to burnout that dermatologists are facing are demanding workloads, administrative burdens, and loss of autonomy. Dermatologists welcome medical challenges, but they face growing administrative and regulatory burdens that take time away from patient care and contribute to burnout. Taking a wellness-centered approach can help, which is why the AAD includes both practical tools to reduce burdens and strategies to sustain your practice in its online resources. The burnout and wellness section of the AAD website can help with administrative burdens, building a supportive work culture, recognizing drivers of burnout, reconnecting with your purpose, and more.

How is the AAD working to ensure that the expanding scope of practice does not compromise patient safety, particularly when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of complex skin cancers or prescribing systemic medications?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD advocates to ensure that each member of the care team is practicing at a level consistent with their training and education and opposes scope-of-practice expansions for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other nonphysician clinicians that threaten patient safety by allowing them to practice independently and advertise as skin experts. Each state has its own scope-of-practice laws governing what nonphysicians can do, whether supervision is required, and how they can represent their training, both in advertising and in a medical practice. The AAD supports appropriate safeguards to ensure patient safety and a focus on the highest-quality appropriate care as the nonphysician workforce expands. The AAD encourages patients to report adverse outcomes to the appropriate state licensing boards.

Is the AAD developing or recommending best practices for dermatologists who supervise NPs or PAs, especially in large practices or retail clinics where oversight can be inconsistent?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD firmly believes that the optimal quality of medical care is delivered when a qualified and licensed physician provides direct on-site supervision to all qualified nonphysician personnel. A medical director of a medical spa facility should be a physician licensed in the state where the facility is located and also should be clearly identified by state licensure and any state-recognized board certification as well as by medical specialty, training, and education. The individual also should be identified as the medical director in all marketing materials and on websites and social media accounts related to the medical spa facility. The AAD would like to see policies that would provide increased transparency in state licensure and specialty board certification including requiring disclosure that a physician is certified or eligible for certification by a private or public board, parent association, or multidisciplinary board or association; requiring disclosure of the certifying board or association with one’s field of study or specialty; requiring display of visible identification—including one’s state licensure, professional degree, field of study, and the use of clarifying titles—in facilities, in marketing materials, and on websites and social media; and requiring all personnel in private medical practices, hospitals, clinics, or other settings employing physicians and/or other personnel that offer medical, surgical, or aesthetic procedures to wear a photo identification name tag during all patient encounters.

What are the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD’s) top advocacy priorities related to Medicare physician reimbursement?

Dr. Taylor: Medicare physician payment has failed to keep up with inflation, threatening the viability of medical practices. The AAD urges Congress to stabilize the Medicare payment system to ensure continued patient access to essential health care by

What is the AAD’s stance on transitioning from traditional fee-for-service to value-based care models in dermatology under Medicare?

Dr. Taylor: Current value-based programs are extremely burdensome, have not demonstrated improved patient care, and are not clinically relevant to physicians or patients. The AAD has serious concerns about the viability and effectiveness of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), especially the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Numerous studies have highlighted persistent challenges associated with MIPS, including practices serving high-risk patients and those that are small or in rural areas. For instance, researchers examined whether MIPS disproportionately penalized surgeons who care for these patients and found a connection between caring for these patients, lower MIPS scores, and a higher likelihood of facing negative payment adjustments.

Additionally, the US Government Accountability Office was tasked with reviewing several aspects concerning small and rural practices in relation to Medicare payment incentive programs, including MIPS. Findings indicated that physician practices with 15 or fewer providers, whether located in rural or nonrural areas, had a higher likelihood of receiving negative payment adjustments in Medicare incentive programs compared to larger practices. To maximize participation and facilitate the best possible outcomes for dermatologists within the MIPS program, the AAD maintains that we must continue to develop and advocate that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approve dermatology-specific measures for MIPS reporting.

Does the AAD have plans to develop or expand dermatology-specific quality measures that are more clinically relevant and less administratively taxing?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is committed to ensuring that dermatologists can be successful in the QPP and its MIPS Value Pathways and Advanced Alternative Payment Model programs. These payment pathways for QPP-eligible participants allow physicians to increase their future Medicare reimbursements but also penalize those who do not meet performance objectives. The AAD is constantly reviewing and proposing new dermatology-specific quality measures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services based on member feedback to reduce administrative burdens of MIPS reporting. All of our quality measures are developed by dermatologists for dermatologists.

How is the AAD supporting practices dealing with insurer-mandated switch policies that disrupt continuity of care and increase documentation burden?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD works with private payers to alleviate administrative burdens for dermatologists, maintain appropriate reimbursement for services provided, and ensure patients can access covered quality care by building and maintaining relationships with public and private payers. This critical collaboration addresses immediate needs affecting our members’ ability to deliver care, such as when policy changes affect claims and formulary coverage or payment. Our coordinated strategy ensures payer policies align with everyday practice for dermatologists so they can focus on treating patients. The AAD has resources and tools to guide dermatology practices in appropriate documentation and coding.

What initiatives is the AAD pursuing to specifically support independent or small dermatology practices in coping with administrative overload?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD is continuously advocating for our small and independent dermatology practices. In every comment letter we submit on proposed medical practice reporting regulation, we demand small practice exemptions. Moreover, the AAD has resources and practical tools for all types of practices to cope with administrative burdens, including MIPS reporting requirements. These resources and tools were created by dermatologists for dermatologists to take the guesswork out of administrative compliance. DataDerm is the AAD’s clinical data registry used for MIPS reporting. Since its launch in 2016, DataDerm has become dermatology’s largest clinical data registry, capturing information on more than 16 million unique patients and 69 million encounters. It supports the advancement of skin disease diagnosis and treatment, informs clinical practice, streamlines MIPS reporting, and drives clinically relevant research using real-world data.

What are the biggest contributors to physician burnout right now? What resources does AAD offer to support dermatologists in managing burnout?

Dr. Taylor: The biggest contributors to burnout that dermatologists are facing are demanding workloads, administrative burdens, and loss of autonomy. Dermatologists welcome medical challenges, but they face growing administrative and regulatory burdens that take time away from patient care and contribute to burnout. Taking a wellness-centered approach can help, which is why the AAD includes both practical tools to reduce burdens and strategies to sustain your practice in its online resources. The burnout and wellness section of the AAD website can help with administrative burdens, building a supportive work culture, recognizing drivers of burnout, reconnecting with your purpose, and more.

How is the AAD working to ensure that the expanding scope of practice does not compromise patient safety, particularly when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of complex skin cancers or prescribing systemic medications?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD advocates to ensure that each member of the care team is practicing at a level consistent with their training and education and opposes scope-of-practice expansions for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other nonphysician clinicians that threaten patient safety by allowing them to practice independently and advertise as skin experts. Each state has its own scope-of-practice laws governing what nonphysicians can do, whether supervision is required, and how they can represent their training, both in advertising and in a medical practice. The AAD supports appropriate safeguards to ensure patient safety and a focus on the highest-quality appropriate care as the nonphysician workforce expands. The AAD encourages patients to report adverse outcomes to the appropriate state licensing boards.

Is the AAD developing or recommending best practices for dermatologists who supervise NPs or PAs, especially in large practices or retail clinics where oversight can be inconsistent?

Dr. Taylor: The AAD firmly believes that the optimal quality of medical care is delivered when a qualified and licensed physician provides direct on-site supervision to all qualified nonphysician personnel. A medical director of a medical spa facility should be a physician licensed in the state where the facility is located and also should be clearly identified by state licensure and any state-recognized board certification as well as by medical specialty, training, and education. The individual also should be identified as the medical director in all marketing materials and on websites and social media accounts related to the medical spa facility. The AAD would like to see policies that would provide increased transparency in state licensure and specialty board certification including requiring disclosure that a physician is certified or eligible for certification by a private or public board, parent association, or multidisciplinary board or association; requiring disclosure of the certifying board or association with one’s field of study or specialty; requiring display of visible identification—including one’s state licensure, professional degree, field of study, and the use of clarifying titles—in facilities, in marketing materials, and on websites and social media; and requiring all personnel in private medical practices, hospitals, clinics, or other settings employing physicians and/or other personnel that offer medical, surgical, or aesthetic procedures to wear a photo identification name tag during all patient encounters.

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

Shaping the Future of Dermatology Practice: Leadership Insight From Susan C. Taylor, MD

Medicolegal Concerns in Contemporary Private GI Practice

The need for gastroenterology (GI) services is on the rise in the US, with growing rates of colonoscopy, earlier-onset colon cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease. This increase is taking place in the context of a changing regulatory landscape.

, and to that end, a recent educational practice management update was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Erin Smith Aebel, JD, a health law specialist with Trenam Law in Tampa, Florida. Aebel has been a speaker at several national GI conferences and has addressed GI trainees on these issues in medical schools.

“Healthcare regulation continues to evolve and it’s a complicated area,” Aebel told GI & Hepatology News. “Some physician investors in healthcare ventures see the potential profits but are not fully aware of how a physician’s license and livelihood could be affected by noncompliance.”

Aebel has seen some medical business owners and institutions pushing physicians to their limits in order to maximize profits. “They’re failing to allow them the meaningful things that allow for a long-term productive and successful practice that provides great patient care,” she said. “A current issue I’m dealing with is employers’ taking away physicians’ administrative time and not respecting the work that is necessary for the physician to be efficient and provide great care,” she said. “If too many physicians get squeezed in this manner, they will eventually walk away from big employers to something they can better control.”

Aebel noted that private-equity acquisitions of medical practices — a fast-growing US trend — are often targeted at quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care. “A question to be asked by physicians and patients is who is benefiting from this transaction?” she said. “Sometimes retired physicians can see a great benefit in private equity, but newer physicians can get tied up with a strong noncompete agreement. The best deals are ones that try to find wins for all involved, including patients.”

Many independent gastroenterologists focusing on the demands of daily practice are less aware than they should be of the legal and business administration sides. “I often get clients who come to me complaining about their contracts after they’ve signed them. I don’t have leverage to do as much for them,” she admitted.

From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control. These could relate to compensation and bonuses, as well as opportunities to invest in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

Aebel’s overarching messages to gastroenterologists are as follows: “Be aware. Learn basic health law. Read your contracts before you sign them. And invest in good counsel before you sign agreements,” she said. “In addition, GI practitioners need to have a working knowledge of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute and the federal Stark Law and how they could be commonly applied in their practices.”

These are designed to protect government-funded patient care from monetary influence. The False Claims Act is another federal buttress against fraud and abuse, she said.

Update Details

Though not intended to be legal advice, Aebel’s update touches on several important medicolegal areas.

Stark Law on Self-Referrals

Gastroenterologists should be familiar with this federal law, a self-referral civil penalty statute regulating how physicians can pay themselves in practices that provide designated health services covered by federal healthcare programs such as Medicare or Medicaid.

For a Stark penalty to apply, there must be a physician referral to an entity (eg, lab, hospital, nutrition service, physiotherapy or radiotherapy center) in which the physician or a close family member has a financial interest.

Ambulatory Surgery Centers

Another common area vulnerable to federal fraud and abuse regulation is investment in ASCs. “Generally speaking, it is a felony to pay or be paid anything of value for Medicare or Medicaid business referrals,” Aebel wrote. This provision relates to the general restriction of the federal AKB statute.

A gastroenterologist referring Medicare patients to a center where that physician has an investment could technically violate this law because the physician will receive profit distributions from the referral. In addition to constituting a felony with potential jail time, violation of this statute is grounds for substantial civil monetary penalties and/or exclusion from the government coverage program.

Fortunately, Aebel noted, legal safe harbors cover many financial relationships, including investment in an ASC. The financial arrangement is protected from prosecution if it meets five safe harbor requirements, including nondiscriminatory treatment of government-insured patients and physician investment unrelated to a center’s volume or the value of referrals. If even one aspect is not met, that will automatically constitute a crime.

“However, the government will look at facts and circumstances to determine whether there was an intent to pay for a referral,” Aebel wrote.

The safe harbor designates requirements for four types of ASCs: surgeon-owned, single-specialty, multispecialty, and hospital/physician ASCs.

Private-Equity Investment

With mergers and acquisitions of US medical practices and networks by private-equity firms becoming more common, gastroenterologists need to be aware of the legal issues involved in such investment.

Most states abide by corporate practice of medicine doctrines, which prohibit unlicensed people from direct ownership in a medical practice. These doctrines vary by state, but their primary goal is to ensure that medical decisions are made solely based on patient care and not influenced by corporate interests. The aim is to shield the physician-patient relationship from commercial influence.

“Accordingly, this creates additional complicated structures necessary for private-equity investment in gastroenterology practices,” Aebel wrote. Usually, such investors will invest in a management services organization (MSO), which takes much of the practice’s value via management fees. Gastroenterologists may or may not have an opportunity to invest in the practice and the MSO in this scenario.

Under corporate practice of medicine doctrine, physicians must control the clinical aspects of patient care. Therefore, some states may have restrictions on private-equity companies’ control of the use of medical devices, pricing, medical protocols, or other issues of patient care.

“This needs to be considered when reviewing the investment documents and structural documents proposed by private equity companies,” the advisory stated. From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control over their clinical practice. “This could relate to their compensation, bonuses, and investment opportunities in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ASCs.”

Offering a gastroenterologist’s perspective on the paper, Camille Thélin, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the Division of Digestive Diseases and Health at the University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, who also practices privately, said, that “what Erin Aebel reminds us is that the business side of GI can be just as tricky as the clinical side. Ancillary services like capsule studies or office labs fall under strict Stark rules, ASC ownership has Anti-Kickback Law restrictions, and private-equity deals may affect both your paycheck and your autonomy.”

Thélin’s main takeaway advice is that business opportunities can be valuable but carry real legal risks if not structured correctly. “This isn’t just abstract compliance law — it’s about protecting one’s ability to practice medicine, earn fairly, and avoid devastating penalties,” she told GI & Hepatology News. “This article reinforces the need for proactive legal review and careful structuring of business arrangements so physicians can focus on patient care without stumbling into avoidable legal pitfalls. With the right legal structure, ancillaries, ASCs, and private equity can strengthen your GI practice without risking compliance.”

The bottom line, said Aebel, is that gastroenterologists already in private practice or considering entering one must navigate a complex landscape of compliance and regulatory requirements — particularly when providing ancillary services, investing in ASCs, or engaging with private equity.

Understanding the Stark law, the AKB statute, and the intricacies of private-equity investment is essential to mitigate risks and avoid severe penalties, the advisory stressed. By proactively seeking expert legal and business guidance, gastroenterologists can structure their financial and ownership arrangements in a compliant manner, safeguarding their practices while capitalizing on growth opportunities.

This paper listed no external funding. Neither Aebel nor Thélin had any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The need for gastroenterology (GI) services is on the rise in the US, with growing rates of colonoscopy, earlier-onset colon cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease. This increase is taking place in the context of a changing regulatory landscape.

, and to that end, a recent educational practice management update was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Erin Smith Aebel, JD, a health law specialist with Trenam Law in Tampa, Florida. Aebel has been a speaker at several national GI conferences and has addressed GI trainees on these issues in medical schools.

“Healthcare regulation continues to evolve and it’s a complicated area,” Aebel told GI & Hepatology News. “Some physician investors in healthcare ventures see the potential profits but are not fully aware of how a physician’s license and livelihood could be affected by noncompliance.”

Aebel has seen some medical business owners and institutions pushing physicians to their limits in order to maximize profits. “They’re failing to allow them the meaningful things that allow for a long-term productive and successful practice that provides great patient care,” she said. “A current issue I’m dealing with is employers’ taking away physicians’ administrative time and not respecting the work that is necessary for the physician to be efficient and provide great care,” she said. “If too many physicians get squeezed in this manner, they will eventually walk away from big employers to something they can better control.”

Aebel noted that private-equity acquisitions of medical practices — a fast-growing US trend — are often targeted at quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care. “A question to be asked by physicians and patients is who is benefiting from this transaction?” she said. “Sometimes retired physicians can see a great benefit in private equity, but newer physicians can get tied up with a strong noncompete agreement. The best deals are ones that try to find wins for all involved, including patients.”

Many independent gastroenterologists focusing on the demands of daily practice are less aware than they should be of the legal and business administration sides. “I often get clients who come to me complaining about their contracts after they’ve signed them. I don’t have leverage to do as much for them,” she admitted.

From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control. These could relate to compensation and bonuses, as well as opportunities to invest in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

Aebel’s overarching messages to gastroenterologists are as follows: “Be aware. Learn basic health law. Read your contracts before you sign them. And invest in good counsel before you sign agreements,” she said. “In addition, GI practitioners need to have a working knowledge of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute and the federal Stark Law and how they could be commonly applied in their practices.”

These are designed to protect government-funded patient care from monetary influence. The False Claims Act is another federal buttress against fraud and abuse, she said.

Update Details

Though not intended to be legal advice, Aebel’s update touches on several important medicolegal areas.

Stark Law on Self-Referrals

Gastroenterologists should be familiar with this federal law, a self-referral civil penalty statute regulating how physicians can pay themselves in practices that provide designated health services covered by federal healthcare programs such as Medicare or Medicaid.

For a Stark penalty to apply, there must be a physician referral to an entity (eg, lab, hospital, nutrition service, physiotherapy or radiotherapy center) in which the physician or a close family member has a financial interest.

Ambulatory Surgery Centers

Another common area vulnerable to federal fraud and abuse regulation is investment in ASCs. “Generally speaking, it is a felony to pay or be paid anything of value for Medicare or Medicaid business referrals,” Aebel wrote. This provision relates to the general restriction of the federal AKB statute.

A gastroenterologist referring Medicare patients to a center where that physician has an investment could technically violate this law because the physician will receive profit distributions from the referral. In addition to constituting a felony with potential jail time, violation of this statute is grounds for substantial civil monetary penalties and/or exclusion from the government coverage program.

Fortunately, Aebel noted, legal safe harbors cover many financial relationships, including investment in an ASC. The financial arrangement is protected from prosecution if it meets five safe harbor requirements, including nondiscriminatory treatment of government-insured patients and physician investment unrelated to a center’s volume or the value of referrals. If even one aspect is not met, that will automatically constitute a crime.

“However, the government will look at facts and circumstances to determine whether there was an intent to pay for a referral,” Aebel wrote.

The safe harbor designates requirements for four types of ASCs: surgeon-owned, single-specialty, multispecialty, and hospital/physician ASCs.

Private-Equity Investment

With mergers and acquisitions of US medical practices and networks by private-equity firms becoming more common, gastroenterologists need to be aware of the legal issues involved in such investment.

Most states abide by corporate practice of medicine doctrines, which prohibit unlicensed people from direct ownership in a medical practice. These doctrines vary by state, but their primary goal is to ensure that medical decisions are made solely based on patient care and not influenced by corporate interests. The aim is to shield the physician-patient relationship from commercial influence.

“Accordingly, this creates additional complicated structures necessary for private-equity investment in gastroenterology practices,” Aebel wrote. Usually, such investors will invest in a management services organization (MSO), which takes much of the practice’s value via management fees. Gastroenterologists may or may not have an opportunity to invest in the practice and the MSO in this scenario.

Under corporate practice of medicine doctrine, physicians must control the clinical aspects of patient care. Therefore, some states may have restrictions on private-equity companies’ control of the use of medical devices, pricing, medical protocols, or other issues of patient care.

“This needs to be considered when reviewing the investment documents and structural documents proposed by private equity companies,” the advisory stated. From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control over their clinical practice. “This could relate to their compensation, bonuses, and investment opportunities in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ASCs.”

Offering a gastroenterologist’s perspective on the paper, Camille Thélin, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the Division of Digestive Diseases and Health at the University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, who also practices privately, said, that “what Erin Aebel reminds us is that the business side of GI can be just as tricky as the clinical side. Ancillary services like capsule studies or office labs fall under strict Stark rules, ASC ownership has Anti-Kickback Law restrictions, and private-equity deals may affect both your paycheck and your autonomy.”

Thélin’s main takeaway advice is that business opportunities can be valuable but carry real legal risks if not structured correctly. “This isn’t just abstract compliance law — it’s about protecting one’s ability to practice medicine, earn fairly, and avoid devastating penalties,” she told GI & Hepatology News. “This article reinforces the need for proactive legal review and careful structuring of business arrangements so physicians can focus on patient care without stumbling into avoidable legal pitfalls. With the right legal structure, ancillaries, ASCs, and private equity can strengthen your GI practice without risking compliance.”

The bottom line, said Aebel, is that gastroenterologists already in private practice or considering entering one must navigate a complex landscape of compliance and regulatory requirements — particularly when providing ancillary services, investing in ASCs, or engaging with private equity.

Understanding the Stark law, the AKB statute, and the intricacies of private-equity investment is essential to mitigate risks and avoid severe penalties, the advisory stressed. By proactively seeking expert legal and business guidance, gastroenterologists can structure their financial and ownership arrangements in a compliant manner, safeguarding their practices while capitalizing on growth opportunities.

This paper listed no external funding. Neither Aebel nor Thélin had any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The need for gastroenterology (GI) services is on the rise in the US, with growing rates of colonoscopy, earlier-onset colon cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease. This increase is taking place in the context of a changing regulatory landscape.

, and to that end, a recent educational practice management update was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Erin Smith Aebel, JD, a health law specialist with Trenam Law in Tampa, Florida. Aebel has been a speaker at several national GI conferences and has addressed GI trainees on these issues in medical schools.

“Healthcare regulation continues to evolve and it’s a complicated area,” Aebel told GI & Hepatology News. “Some physician investors in healthcare ventures see the potential profits but are not fully aware of how a physician’s license and livelihood could be affected by noncompliance.”

Aebel has seen some medical business owners and institutions pushing physicians to their limits in order to maximize profits. “They’re failing to allow them the meaningful things that allow for a long-term productive and successful practice that provides great patient care,” she said. “A current issue I’m dealing with is employers’ taking away physicians’ administrative time and not respecting the work that is necessary for the physician to be efficient and provide great care,” she said. “If too many physicians get squeezed in this manner, they will eventually walk away from big employers to something they can better control.”

Aebel noted that private-equity acquisitions of medical practices — a fast-growing US trend — are often targeted at quick profits and quick exits, which can be inconsistent with quality long-term patient care. “A question to be asked by physicians and patients is who is benefiting from this transaction?” she said. “Sometimes retired physicians can see a great benefit in private equity, but newer physicians can get tied up with a strong noncompete agreement. The best deals are ones that try to find wins for all involved, including patients.”

Many independent gastroenterologists focusing on the demands of daily practice are less aware than they should be of the legal and business administration sides. “I often get clients who come to me complaining about their contracts after they’ve signed them. I don’t have leverage to do as much for them,” she admitted.

From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control. These could relate to compensation and bonuses, as well as opportunities to invest in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

Aebel’s overarching messages to gastroenterologists are as follows: “Be aware. Learn basic health law. Read your contracts before you sign them. And invest in good counsel before you sign agreements,” she said. “In addition, GI practitioners need to have a working knowledge of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute and the federal Stark Law and how they could be commonly applied in their practices.”

These are designed to protect government-funded patient care from monetary influence. The False Claims Act is another federal buttress against fraud and abuse, she said.

Update Details

Though not intended to be legal advice, Aebel’s update touches on several important medicolegal areas.

Stark Law on Self-Referrals

Gastroenterologists should be familiar with this federal law, a self-referral civil penalty statute regulating how physicians can pay themselves in practices that provide designated health services covered by federal healthcare programs such as Medicare or Medicaid.

For a Stark penalty to apply, there must be a physician referral to an entity (eg, lab, hospital, nutrition service, physiotherapy or radiotherapy center) in which the physician or a close family member has a financial interest.

Ambulatory Surgery Centers

Another common area vulnerable to federal fraud and abuse regulation is investment in ASCs. “Generally speaking, it is a felony to pay or be paid anything of value for Medicare or Medicaid business referrals,” Aebel wrote. This provision relates to the general restriction of the federal AKB statute.

A gastroenterologist referring Medicare patients to a center where that physician has an investment could technically violate this law because the physician will receive profit distributions from the referral. In addition to constituting a felony with potential jail time, violation of this statute is grounds for substantial civil monetary penalties and/or exclusion from the government coverage program.

Fortunately, Aebel noted, legal safe harbors cover many financial relationships, including investment in an ASC. The financial arrangement is protected from prosecution if it meets five safe harbor requirements, including nondiscriminatory treatment of government-insured patients and physician investment unrelated to a center’s volume or the value of referrals. If even one aspect is not met, that will automatically constitute a crime.

“However, the government will look at facts and circumstances to determine whether there was an intent to pay for a referral,” Aebel wrote.

The safe harbor designates requirements for four types of ASCs: surgeon-owned, single-specialty, multispecialty, and hospital/physician ASCs.

Private-Equity Investment

With mergers and acquisitions of US medical practices and networks by private-equity firms becoming more common, gastroenterologists need to be aware of the legal issues involved in such investment.

Most states abide by corporate practice of medicine doctrines, which prohibit unlicensed people from direct ownership in a medical practice. These doctrines vary by state, but their primary goal is to ensure that medical decisions are made solely based on patient care and not influenced by corporate interests. The aim is to shield the physician-patient relationship from commercial influence.

“Accordingly, this creates additional complicated structures necessary for private-equity investment in gastroenterology practices,” Aebel wrote. Usually, such investors will invest in a management services organization (MSO), which takes much of the practice’s value via management fees. Gastroenterologists may or may not have an opportunity to invest in the practice and the MSO in this scenario.

Under corporate practice of medicine doctrine, physicians must control the clinical aspects of patient care. Therefore, some states may have restrictions on private-equity companies’ control of the use of medical devices, pricing, medical protocols, or other issues of patient care.

“This needs to be considered when reviewing the investment documents and structural documents proposed by private equity companies,” the advisory stated. From a business standpoint, gastroenterologists need to understand where they can negotiate for financial gain and control over their clinical practice. “This could relate to their compensation, bonuses, and investment opportunities in the practice, the practice management company, and possibly real estate or ASCs.”

Offering a gastroenterologist’s perspective on the paper, Camille Thélin, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the Division of Digestive Diseases and Health at the University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, who also practices privately, said, that “what Erin Aebel reminds us is that the business side of GI can be just as tricky as the clinical side. Ancillary services like capsule studies or office labs fall under strict Stark rules, ASC ownership has Anti-Kickback Law restrictions, and private-equity deals may affect both your paycheck and your autonomy.”

Thélin’s main takeaway advice is that business opportunities can be valuable but carry real legal risks if not structured correctly. “This isn’t just abstract compliance law — it’s about protecting one’s ability to practice medicine, earn fairly, and avoid devastating penalties,” she told GI & Hepatology News. “This article reinforces the need for proactive legal review and careful structuring of business arrangements so physicians can focus on patient care without stumbling into avoidable legal pitfalls. With the right legal structure, ancillaries, ASCs, and private equity can strengthen your GI practice without risking compliance.”

The bottom line, said Aebel, is that gastroenterologists already in private practice or considering entering one must navigate a complex landscape of compliance and regulatory requirements — particularly when providing ancillary services, investing in ASCs, or engaging with private equity.

Understanding the Stark law, the AKB statute, and the intricacies of private-equity investment is essential to mitigate risks and avoid severe penalties, the advisory stressed. By proactively seeking expert legal and business guidance, gastroenterologists can structure their financial and ownership arrangements in a compliant manner, safeguarding their practices while capitalizing on growth opportunities.

This paper listed no external funding. Neither Aebel nor Thélin had any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

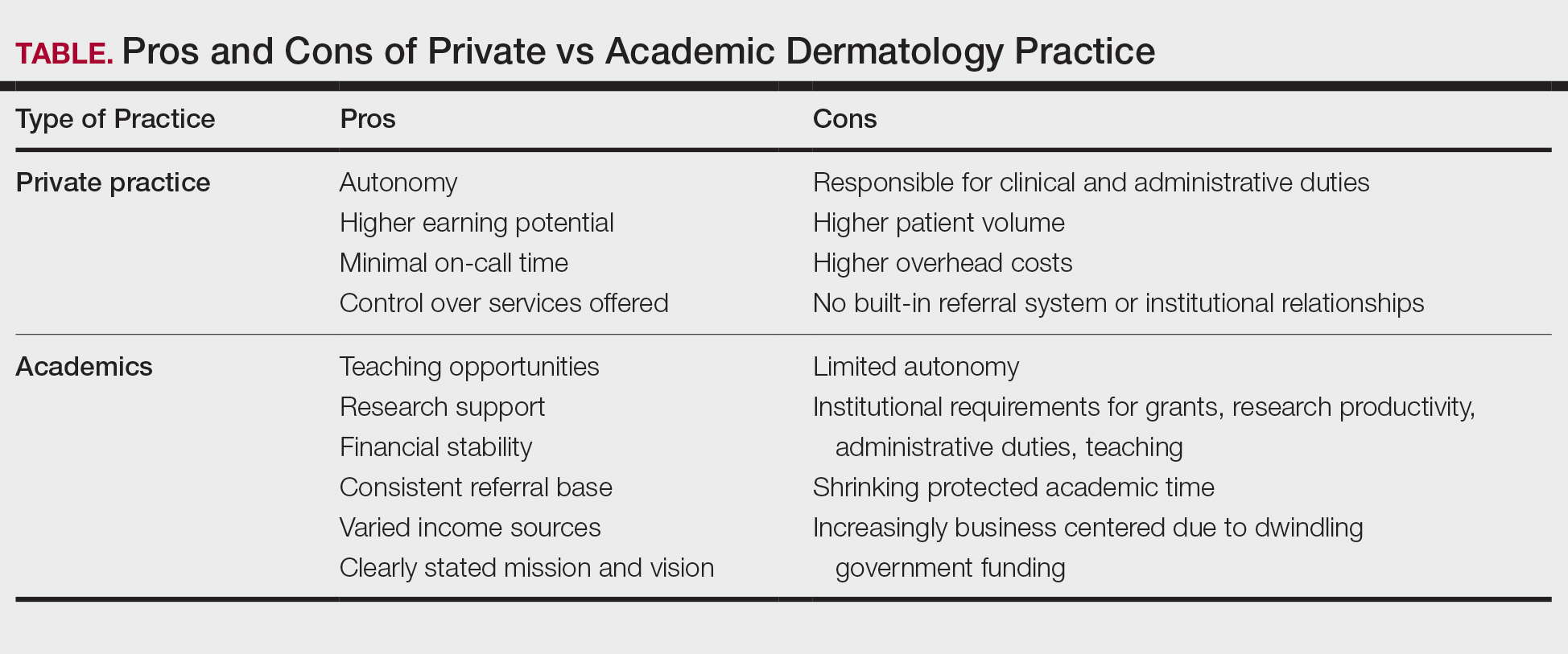

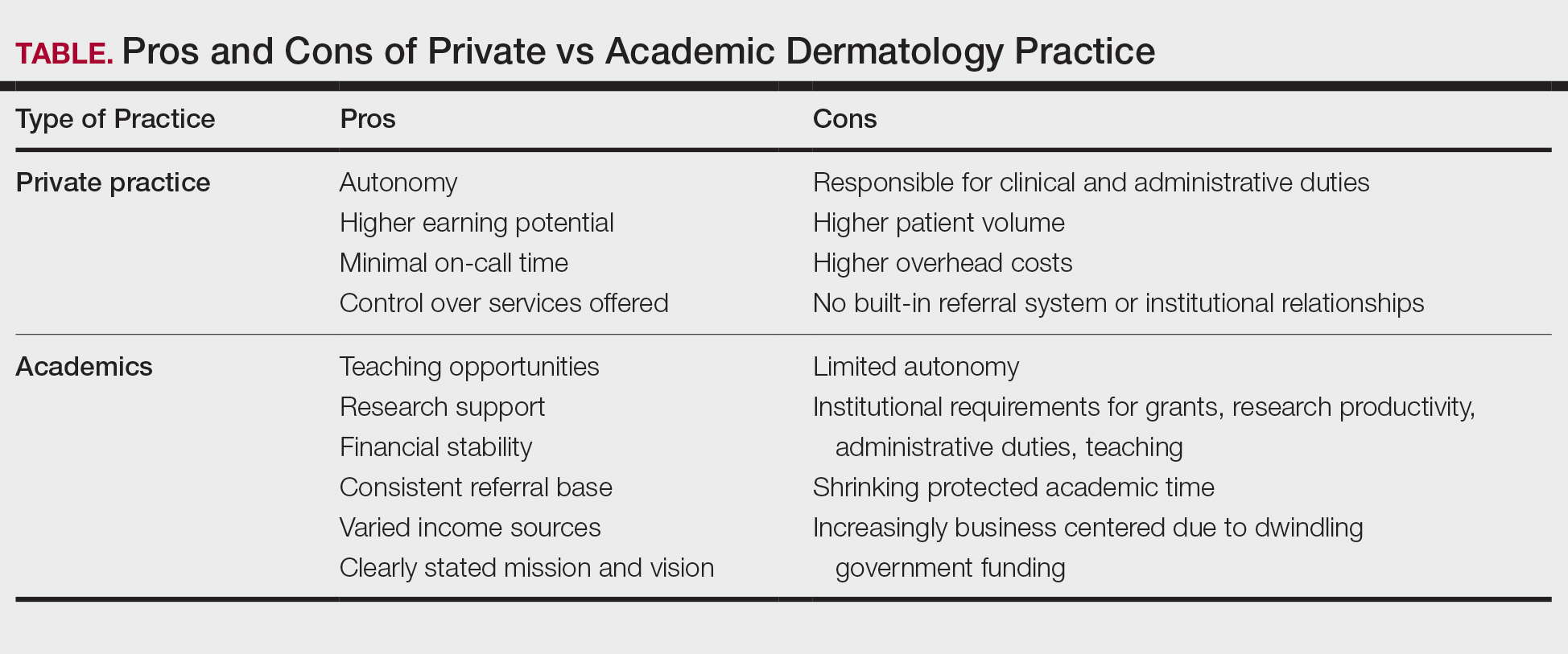

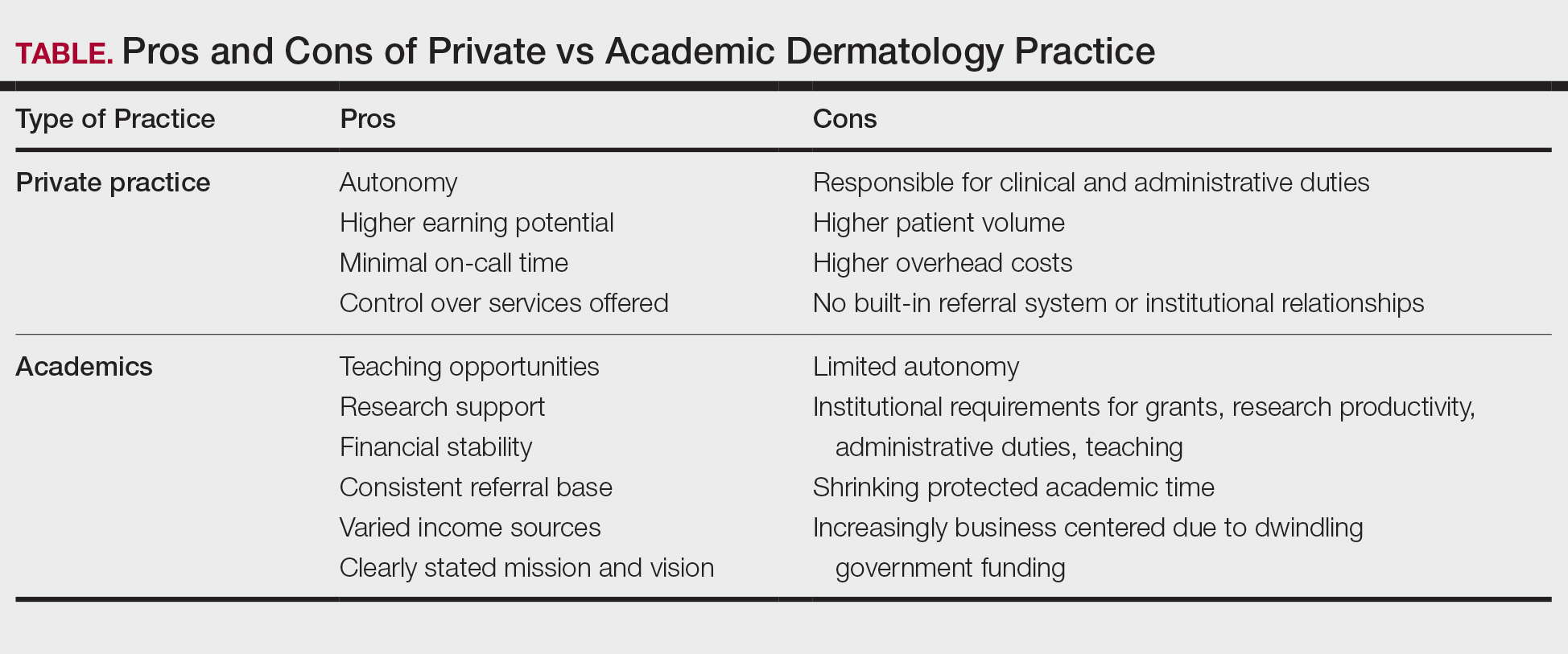

Dermatology is a rapidly growing, highly competitive specialty with patients that can be served via private practice, academic medicine, hybrid settings, and rural health clinics. Medical residents’ choice of a career path has been rapidly evolving alongside shifts in health care policy, increasing demand for dermatologic services, stagnant fees falling behind inflation for more than a decade, and payment methods that no longer reflect the traditional fee-for-service model. This places a lot of pressure on young dermatologists to evaluate which practice structure best fits their career goals. A nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of each practice model is essential for dermatologists to make informed career decisions that are aligned with their values.

While there are many health care practice models, the first decision dermatology residents must make is whether they would prefer working in the private sector or an academic practice. Of course, it is not uncommon for academic dermatologists to embark on a midcareer segue into private practice and, less commonly, for private dermatologists to culminate their careers with a move to academics. The private sector includes private practice, private equity (PE)–owned group practices that often are single-specialty focused, and hospital-owned group practices that usually are multispecialty. Traditionally, private practices are health care businesses owned by one physician (solo practice) or a group of physicians (group practice) operated independently from hospitals, health systems, or private investors. Financially, these practices rely heavily on volume-based services, especially clinic visits and cosmetic procedures, which provide higher reimbursement rates and usually cash payments at the time of service.1 Roughly 35% of dermatologists in the United States work in private practice, and a dwindling 15% work in solo practice.2,3

Medical practices that are not self-owned by physicians vary widely, and they include hospital- or medical center–owned, private equity, and university-based academic practices. Private equity practices typically are characterized as profit driven. Hospital-owned practices shoulder business decisions and administrative duties for the physician at the cost of provider autonomy. Academic medicine is the most different from the other practice types. In contrast to private practice dermatologists, university-based dermatologists practice at academic medical centers (AMCs) with the core goals of patient care, education, and research. Compensation generally is based on the relative value unit (RVU), which is supplemented by government support and research grants.

As evidenced in this brief discussion, health care practice models are complex, and choosing the right model to align with professional goals can pose a major challenge for many physicians. The advantages and disadvantages of various practice models will be reviewed, highlighting trends and emerging models.

Solo or Small-Group Single-Specialty Private Practice

Private practice offers dermatologists the advantage of higher income potential but with greater economic risk; it often requires physicians to be more involved in the business aspects of dermatologic practice. In the early 1990s, a survey of private practice dermatologists revealed that income was the first or second most important factor that contributed to their career choice of private vs academic practice.4 Earning potential in private practice largely is driven by the autonomy afforded in this setting. Physicians have the liberty of choosing their practice location, structure, schedule, and staff in addition to tailoring services toward profitability; this typically leads to a higher volume of cosmetic and procedural visits, which may be attractive to providers wishing to focus on aesthetics. Private practice dermatologists also are not subject to institutional requirements that may include the preparation of grant submissions, research productivity targets, and devotion of time to teaching. Many private dermatologists find satisfaction in tailoring their work environments to align with personal values and goals and in cultivating long-term relationships with patients in a more personal and less bureaucratic context.

There also are drawbacks to private practice. The profitability often can be attributed to the higher patient load and more hours devoted to practice.5 A 2006 study found that academics saw 32% to 41% fewer patients per week than private practice dermatologists.6 Along with the opportunity for financial gain is the risk of financial ruin. Cost is the largest hurdle for establishing a practice, and most practices do not turn a profit for the first few years.1,5 The financial burden of running a practice includes pressure from the federal government to adopt expensive electronic health record systems to achieve maximum Medicare payment through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, liability insurance, health insurance, and staff salaries.7 These challenges require strong business acumen, including managing overhead costs, navigating insurance negotiations, marketing a practice, and maintaining compliance with evolving health care regulations. The purchase of a $100,000 laser could be a boon or bust, requiring the development of a business plan that ensures a positive return on investment. Additionally, private practice profitability has the potential to dwindle as governmental reimbursements fail to match inflation rates. Securing business advisors or even obtaining a Master of Business Administration degree can be helpful.

Insurance and government agencies also are infringing upon some of the autonomy of private practice dermatologists, as evidenced by a 2017 survey of dermatologists that found that more than half of respondents altered treatment plans based on insurance coverage more than 20% of the time.2 Private equity firms also could infringe on private practice autonomy, as providers are beholden to the firm’s restrictions—from which company’s product will be stocked to which partner will be on call. Lastly, private practice is less conducive to consistent referral patterns and strong relationships with specialists when compared to academic practice. Additionally, reliance on high patient throughput or cosmetic services for financial sustainability can shift focus away from complex medical dermatology, which often is referred to AMCs.

Academic Medicine