User login

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

Dermatology is a rapidly growing, highly competitive specialty with patients that can be served via private practice, academic medicine, hybrid settings, and rural health clinics. Medical residents’ choice of a career path has been rapidly evolving alongside shifts in health care policy, increasing demand for dermatologic services, stagnant fees falling behind inflation for more than a decade, and payment methods that no longer reflect the traditional fee-for-service model. This places a lot of pressure on young dermatologists to evaluate which practice structure best fits their career goals. A nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of each practice model is essential for dermatologists to make informed career decisions that are aligned with their values.

While there are many health care practice models, the first decision dermatology residents must make is whether they would prefer working in the private sector or an academic practice. Of course, it is not uncommon for academic dermatologists to embark on a midcareer segue into private practice and, less commonly, for private dermatologists to culminate their careers with a move to academics. The private sector includes private practice, private equity (PE)–owned group practices that often are single-specialty focused, and hospital-owned group practices that usually are multispecialty. Traditionally, private practices are health care businesses owned by one physician (solo practice) or a group of physicians (group practice) operated independently from hospitals, health systems, or private investors. Financially, these practices rely heavily on volume-based services, especially clinic visits and cosmetic procedures, which provide higher reimbursement rates and usually cash payments at the time of service.1 Roughly 35% of dermatologists in the United States work in private practice, and a dwindling 15% work in solo practice.2,3

Medical practices that are not self-owned by physicians vary widely, and they include hospital- or medical center–owned, private equity, and university-based academic practices. Private equity practices typically are characterized as profit driven. Hospital-owned practices shoulder business decisions and administrative duties for the physician at the cost of provider autonomy. Academic medicine is the most different from the other practice types. In contrast to private practice dermatologists, university-based dermatologists practice at academic medical centers (AMCs) with the core goals of patient care, education, and research. Compensation generally is based on the relative value unit (RVU), which is supplemented by government support and research grants.

As evidenced in this brief discussion, health care practice models are complex, and choosing the right model to align with professional goals can pose a major challenge for many physicians. The advantages and disadvantages of various practice models will be reviewed, highlighting trends and emerging models.

Solo or Small-Group Single-Specialty Private Practice

Private practice offers dermatologists the advantage of higher income potential but with greater economic risk; it often requires physicians to be more involved in the business aspects of dermatologic practice. In the early 1990s, a survey of private practice dermatologists revealed that income was the first or second most important factor that contributed to their career choice of private vs academic practice.4 Earning potential in private practice largely is driven by the autonomy afforded in this setting. Physicians have the liberty of choosing their practice location, structure, schedule, and staff in addition to tailoring services toward profitability; this typically leads to a higher volume of cosmetic and procedural visits, which may be attractive to providers wishing to focus on aesthetics. Private practice dermatologists also are not subject to institutional requirements that may include the preparation of grant submissions, research productivity targets, and devotion of time to teaching. Many private dermatologists find satisfaction in tailoring their work environments to align with personal values and goals and in cultivating long-term relationships with patients in a more personal and less bureaucratic context.

There also are drawbacks to private practice. The profitability often can be attributed to the higher patient load and more hours devoted to practice.5 A 2006 study found that academics saw 32% to 41% fewer patients per week than private practice dermatologists.6 Along with the opportunity for financial gain is the risk of financial ruin. Cost is the largest hurdle for establishing a practice, and most practices do not turn a profit for the first few years.1,5 The financial burden of running a practice includes pressure from the federal government to adopt expensive electronic health record systems to achieve maximum Medicare payment through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, liability insurance, health insurance, and staff salaries.7 These challenges require strong business acumen, including managing overhead costs, navigating insurance negotiations, marketing a practice, and maintaining compliance with evolving health care regulations. The purchase of a $100,000 laser could be a boon or bust, requiring the development of a business plan that ensures a positive return on investment. Additionally, private practice profitability has the potential to dwindle as governmental reimbursements fail to match inflation rates. Securing business advisors or even obtaining a Master of Business Administration degree can be helpful.

Insurance and government agencies also are infringing upon some of the autonomy of private practice dermatologists, as evidenced by a 2017 survey of dermatologists that found that more than half of respondents altered treatment plans based on insurance coverage more than 20% of the time.2 Private equity firms also could infringe on private practice autonomy, as providers are beholden to the firm’s restrictions—from which company’s product will be stocked to which partner will be on call. Lastly, private practice is less conducive to consistent referral patterns and strong relationships with specialists when compared to academic practice. Additionally, reliance on high patient throughput or cosmetic services for financial sustainability can shift focus away from complex medical dermatology, which often is referred to AMCs.

Academic Medicine

Academic dermatology offers a stimulating and collaborative environment with opportunities to advance the field through research and education. Often, the opportunity to teach medical students, residents, and peers is the deciding factor for academic dermatologists, as supported by a 2016 survey that found teaching opportunities are a major influence on career decision.8 The mixture of patient care, education, and research roles can be satisfying when compared to the grind of seeing large numbers of patients every day. Because they typically are salaried with an RVU-based income, academic dermatologists often are less concerned with the costs associated with medical treatment, and they typically treat more medically complex patients and underserved populations.9 The salary structure of academic roles also provides the benefit of a stable and predictable income. Physicians in this setting often are considered experts in their field, positioning them to have a strong built-in referral system along with frequent participation in multidisciplinary care alongside colleagues in rheumatology, oncology, and infectious diseases. The benefits of downstream income from dermatopathology, Mohs surgery, and other ancillary testing can provide great financial advantages for an academic or large group practice.10 Academic medical centers also afford the benefit of resources, such as research offices, clinical trial units, and institutional support for scholarly publication.

Despite its benefits, academic dermatology is not without unique demands. The resources afforded by research work come with grant application deadlines and the pressure to maintain research productivity as measured by grant dollars. Academic providers also must navigate institutional political dynamics and deal with limits on autonomy. Additionally, the administrative burden associated with committee work, mentorship obligations, and publishing requirements further limit clinical time and contribute to burnout. According to Loo et al,5 92% of 89 dermatology department chairmen responding to a poll believed that the lower compensation was the primary factor preventing more residents from pursuing academia.

The adoption of RVU-based and incentive compensation models at many AMCs, along with dwindling government funds available for research, also have created pressure to increase patient volume, sometimes at the expense of teaching and research. Of those academic dermatologists spending more than half their time seeing patients, a majority reported that they lack the time to also conduct research, teach, and mentor students and resident physicians.6 A survey of academic dermatologists suggested that, for those already serving in academic positions, salary was less of a concern than the lack of protected academic time.4 While competing demands can erode the appeal of academic dermatology, academia continues to offer a meaningful and fulfilling career path for those motivated by scholarship, mentorship, teaching opportunities, and systemic impact.

Hybrid and Emerging Models

To reconcile the trade-offs inherent in private and academic models, hybrid roles are becoming increasingly common. In these arrangements, dermatologists split their time between private practice and academic appointments settings, allowing for participation in resident education and research while also benefiting from the operational and financial structure of a private office. In some cases, private groups formally affiliate with academic institutions, creating academic-private practices that host trainees and produce scholarly work while operating financially outside of traditional hospital systems. Individual dermatologists also may choose to accept part-time academic roles that allow residents and medical students to rotate in their offices. Hybrid roles may be of most interest to individuals who feel that they are missing out on the mentorship and teaching opportunities afforded at AMCs.

Government-funded systems such as Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals offer another alternative. Dermatologists at VA hospitals often hold faculty appointments, treat a wide range of conditions in a population with great need, and engage in teaching without the intensity of productivity requirements seen at AMCs. These roles can be attractive to physicians who value public service, work-life balance, and minimal malpractice risk, as well as dermatologists who wish to introduce variety in their practice through an additional clinical setting. Notably, these roles are limited, as roughly 80% of VA hospitals employ part-time dermatologists and 72% reported being understaffed.11 Despite the challenges of limited resources and increased bureaucracy, the VA is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, offering the benefits of protection from most malpractice risk and participation in medical education at 80% of VA hospitals.12 A VA-based practice may be most attractive to physicians with prior military service or those looking for a stable practice that serves the underserved and the mission of medical education.

Similarly, rural health clinics are private practices with special subsidies from the federal government that bring Medicaid payments up to the level of Medicare.13 Rural dermatology also mirrors that of a VA-based practice by offering the opportunity to treat an array of conditions in a population of great need, as rural patients often are in care deserts and would otherwise need to travel for miles to receive dermatologic care. There is a shortage of dermatologists working in rural areas, and rural dermatologists are more likely than those in suburban or urban areas to practice alone.2 Although potentially more physically isolating, rural dermatology offers providers the opportunity to establish a lucrative practice with minimal competition and development of meaningful patient relationships.

The most rapidly increasing practice model emerging in dermatology over the past decade is the private equity (PE) group. Rajabi-Estarabadi et al14 estimated that at least 184 dermatology practices have been acquired by PE groups between 2010 and 2019. An estimated 15% of all PE acquisitions in health care have been within the field of dermatology.9 Private equity firms typically acquire 1 or more practices, then consolidate the operations with the short-term goals of reducing costs and maximizing profits and longer-term goals of selling the practice for further profit in 3 to 7 years.9 They often rely heavily on a dermatologist supervising a number of nurse practitioners.15 While PE acquisition may provide additional financial stability and income, providers have less autonomy and potentially risk a shift in their focus from patient care to profit.

The blurred lines between practice settings reflect a broader shift in the profession. Dermatologists have increasingly crafted flexible, individualized careers that align with their goals and values while drawing from both academic and private models. Hybrid roles may prove critical in preserving the educational and research missions of dermatology while adapting to economic and institutional realities.

Gender Trends, Career Satisfaction, and Other Factors Influencing Career Choice

The gender demographics of dermatology have changed greatly in recent decades. In the years 2010 to 2021, the percentage of women in the field rose from 41% to 52.2%, mirroring the rise in female medical students.16 Despite this, gender disparities persist through differences in pay, promotion rates, leadership opportunities, and research productivity.17 Women who are academic dermatologists are less likely to have protected research time and often shoulder a disproportionate share of mentorship and administrative responsibilities, which frequently are undervalued in promotion and compensation structures. Similarly, women physicians are less likely to own their own private practice.18 Notably, women physicians work part-time more often than their male counterparts, which likely impacts their income.19 Interestingly, no differences were noted in job satisfaction between men and women in academic or private practice settings, suggesting that dermatology is a fulfilling field for female physicians.16 Similar data were observed in the field of dermatopathology; in fact, there is no difference in job satisfaction when comparing providers in academics vs private practice.20

Geographic factors also influence career decisions. Some dermatologists may choose private practice to remain close to family or serve a rural area, while some choose academic centers typically located in major metropolitan areas. Others are drawn to AMCs due to their reputation, resources, or opportunities for specialization. The number of practicing dermatologists in an area also may be considered, as areas with fewer providers likely have more individuals seeking a provider and thus more earning potential.

In summary, career satisfaction is influenced by many factors, including practice setting, colleagues, institutional leadership, work environment, and professional goals. For individuals who are seeking intellectual stimulation and teaching opportunities, academic dermatology may be a great career option. Academic or large group practices may come with a large group of clinical dermatologists to provide a steady stream of specimens. Private practice appeals to those seeking autonomy, reduced bureaucracy, and higher earning potential. Tierney et al21 found that the greatest predictor of a future career in academics among Mohs surgeons was the number of publications a fellow had before and during fellowship training. These data suggest that personal interests greatly influence career decisions.

The Role of Mentorship in Career Decision-Making

Just as personal preferences guide career decisions, so too do interpersonal interactions. Mentorship plays a large role in career success, and the involvement of faculty mentors in society meetings and editorial boards has been shown to positively correlate with the number of residents pursuing academia.14 Similarly, negative interactions have strong impacts, as the top cited reason for Mohs surgeons leaving academia was lack of support from their academic chair.21 While many academic dermatologists report fulfillment from the collegial environment, retention remains an issue. Tierney et al21 found that, among 455 academic Mohs surgeons, only 28% of those who began in academia remained in those roles over the long term, and this trend of low retention holds true across the field of academic dermatology. Lack of autonomy, insufficient institutional support, and more lucrative private practice opportunities were all cited as reasons for leaving. For dermatologists seeking separation from academics but continued research opportunities, data suggest that private practice allows for continued research and publications, indicating that scholarly engagement is not exclusive to academic settings. These trends point to the increasing viability of hybrid or academic-private models that combine academic productivity with greater flexibility and financial stability.

Final Thoughts

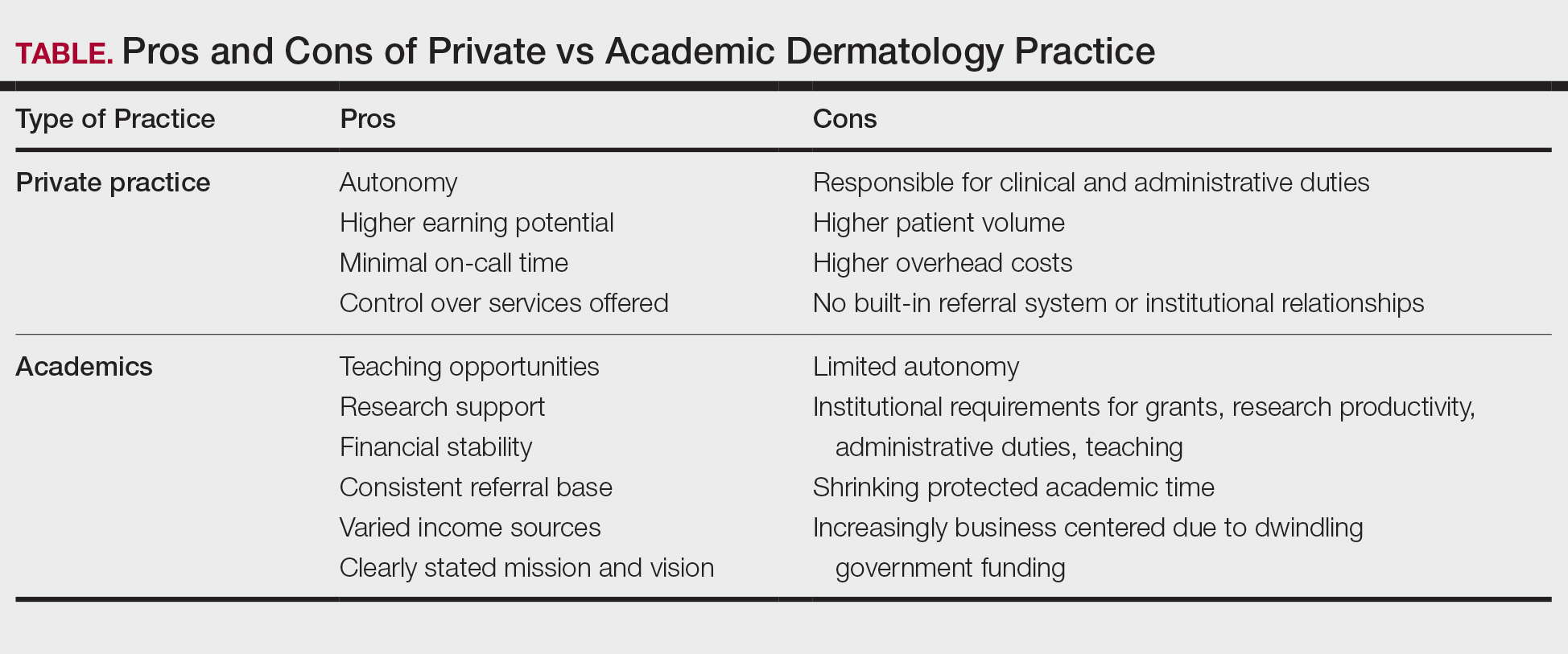

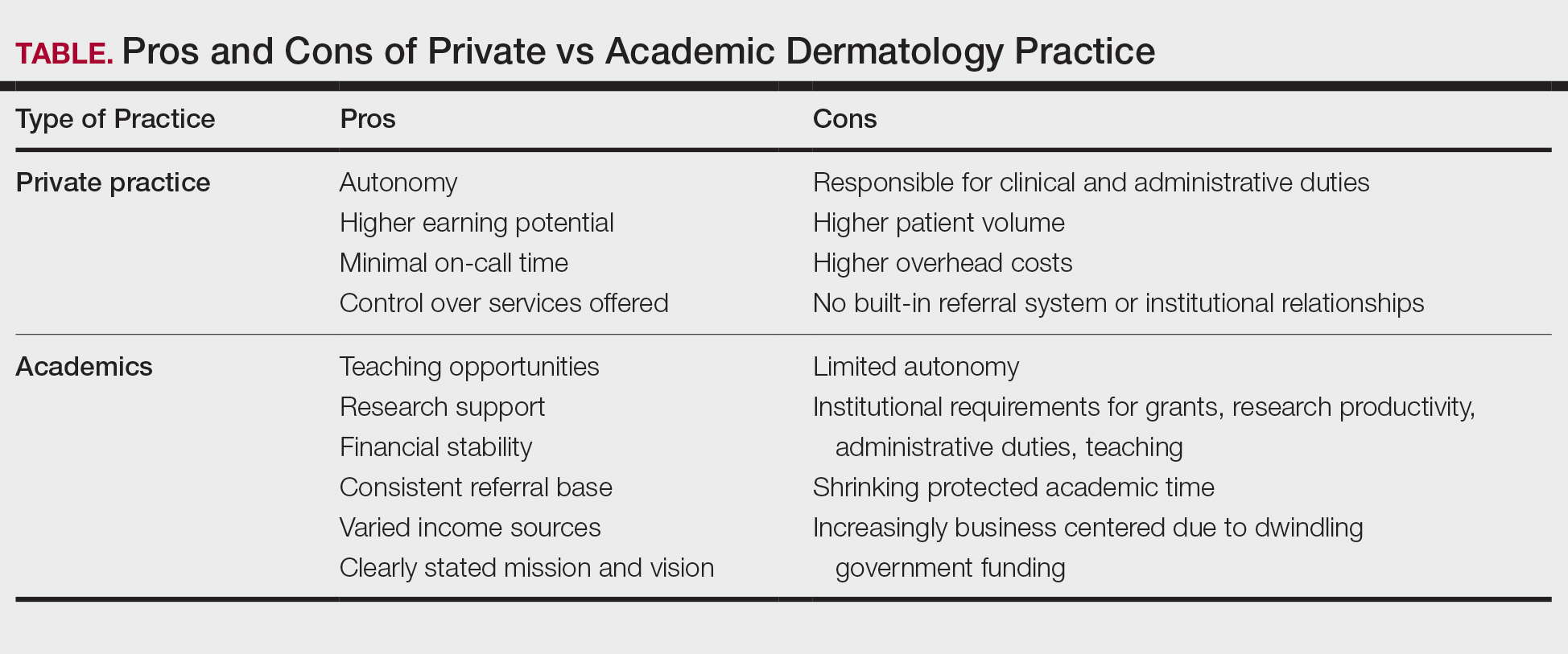

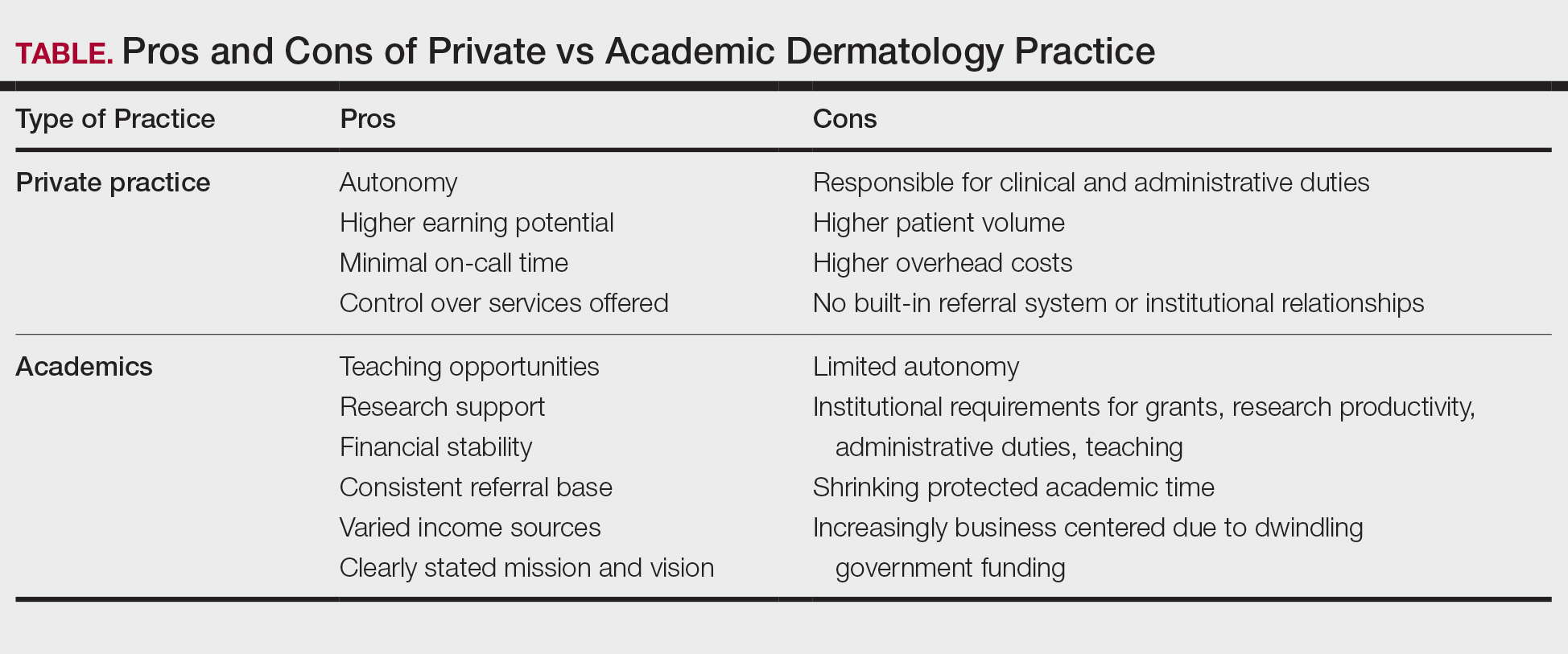

Academic and private practice dermatology each offer compelling advantages and distinct challenges (Table). The growing popularity of hybrid models reflects a desire among dermatologists to balance the intellectual fulfillment associated with academic medicine with professional sustainability and autonomy of private practice. Whether through part-time academic appointments, rural health clinics, VA employment, or affiliations between private groups and academic institutions, these emerging roles offer a flexible and adaptive approach to career development.

Ultimately, the ideal practice model is one that aligns with a physician’s personal values, long-term goals, and lifestyle preferences. No single path fits all, but thoughtful career planning supported by mentorship and institutional transparency can help dermatologists thrive in a rapidly evolving health care landscape.

- Kaplan J. Part I: private practice versus academic medicine. BoardVitals Blog. June 5, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.boardvitals.com/blog/private-practice-academic-medicine/

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Parthasarathy V, Pollock JR, McNeely GL, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of trends in dermatology practice size in the United States from 2012 to 2020. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;315:223-229. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02344-0

- Bergstresser PR. Perceptions of the academic environment: a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1092-1096. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70311-o

- Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower: issues of recruitment and retention. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.341

- Resneck JS, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.013

- Salmen N, Brodell R, Brodell Dolohanty L. The electronic health record: should small practices adopt this technology? J of Skin. 2024;8:1269-1273. doi:10.25251/skin.8.1.8

- Morales-Pico BM, Cotton CC, Morrell DS. Factors correlated with residents’ decisions to enter academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7295783b.

- DeWane ME, Mostow E, Grant-Kels JM. The corporatization of care in academic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:289-295. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.003

- Pearlman RL, Nahar VK, Sisson WT, et al. Understanding downstream service profitability generated by dermatology faculty in an academic medical center: a key driver to promotion of access-to-care. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1425-1427. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02406-3

- Huang WW, Tsoukas MM, Bhutani T, et al. Benchmarking U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs dermatologic services: a nationwide survey of VA dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:50-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.035

- 20 reasons doctors like working for the Veterans Health Administration. US Department of Veterans Affairs. August 2016. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/20ReasonsVHA_508_IB10935.pdf

- Rural health clinics (RHCs). Rural Health Information Hub. Updated April 7, 2025. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www .ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-clinics

- Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Jones VA, Zheng C, et al. Dermatologist transitions: academics into private practices and vice versa. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:541-546. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.05.012

- Bruch JD, Foot C, Singh Y, et al. Workforce composition in private equity–acquired versus non–private equity–acquired physician practices. Health Affairs. 2023;42:121-129. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00308

- Zlakishvili B, Horev A. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research over the past 15 years. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:e160. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000160

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Levender MM, et al. Practice patterns and job satisfaction of Mohs surgeons: a gender-based survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1103-1108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29140863/

- Kane CK. Policy Research Perspectives. Recent changes in physician practice arrangements: shifts away from private practice and towards larger practice size continue through 2022. American Medical Association website. 2023. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2022-prp-practice-arrangement.pdf

- Frank E, Zhao Z, Sen S, et al. Gender disparities in work and parental status among early career physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198340. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8340

- Boyd AS, Fang F. A survey-based evaluation of dermatopathology in the United States. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:173-176. doi:10.1097/dad.0b013e3181f0ed84

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW, Kimball AB. Career trajectory and job satisfaction trends in Mohs micrographic surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1229-1238. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02076.x

Dermatology is a rapidly growing, highly competitive specialty with patients that can be served via private practice, academic medicine, hybrid settings, and rural health clinics. Medical residents’ choice of a career path has been rapidly evolving alongside shifts in health care policy, increasing demand for dermatologic services, stagnant fees falling behind inflation for more than a decade, and payment methods that no longer reflect the traditional fee-for-service model. This places a lot of pressure on young dermatologists to evaluate which practice structure best fits their career goals. A nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of each practice model is essential for dermatologists to make informed career decisions that are aligned with their values.

While there are many health care practice models, the first decision dermatology residents must make is whether they would prefer working in the private sector or an academic practice. Of course, it is not uncommon for academic dermatologists to embark on a midcareer segue into private practice and, less commonly, for private dermatologists to culminate their careers with a move to academics. The private sector includes private practice, private equity (PE)–owned group practices that often are single-specialty focused, and hospital-owned group practices that usually are multispecialty. Traditionally, private practices are health care businesses owned by one physician (solo practice) or a group of physicians (group practice) operated independently from hospitals, health systems, or private investors. Financially, these practices rely heavily on volume-based services, especially clinic visits and cosmetic procedures, which provide higher reimbursement rates and usually cash payments at the time of service.1 Roughly 35% of dermatologists in the United States work in private practice, and a dwindling 15% work in solo practice.2,3

Medical practices that are not self-owned by physicians vary widely, and they include hospital- or medical center–owned, private equity, and university-based academic practices. Private equity practices typically are characterized as profit driven. Hospital-owned practices shoulder business decisions and administrative duties for the physician at the cost of provider autonomy. Academic medicine is the most different from the other practice types. In contrast to private practice dermatologists, university-based dermatologists practice at academic medical centers (AMCs) with the core goals of patient care, education, and research. Compensation generally is based on the relative value unit (RVU), which is supplemented by government support and research grants.

As evidenced in this brief discussion, health care practice models are complex, and choosing the right model to align with professional goals can pose a major challenge for many physicians. The advantages and disadvantages of various practice models will be reviewed, highlighting trends and emerging models.

Solo or Small-Group Single-Specialty Private Practice

Private practice offers dermatologists the advantage of higher income potential but with greater economic risk; it often requires physicians to be more involved in the business aspects of dermatologic practice. In the early 1990s, a survey of private practice dermatologists revealed that income was the first or second most important factor that contributed to their career choice of private vs academic practice.4 Earning potential in private practice largely is driven by the autonomy afforded in this setting. Physicians have the liberty of choosing their practice location, structure, schedule, and staff in addition to tailoring services toward profitability; this typically leads to a higher volume of cosmetic and procedural visits, which may be attractive to providers wishing to focus on aesthetics. Private practice dermatologists also are not subject to institutional requirements that may include the preparation of grant submissions, research productivity targets, and devotion of time to teaching. Many private dermatologists find satisfaction in tailoring their work environments to align with personal values and goals and in cultivating long-term relationships with patients in a more personal and less bureaucratic context.

There also are drawbacks to private practice. The profitability often can be attributed to the higher patient load and more hours devoted to practice.5 A 2006 study found that academics saw 32% to 41% fewer patients per week than private practice dermatologists.6 Along with the opportunity for financial gain is the risk of financial ruin. Cost is the largest hurdle for establishing a practice, and most practices do not turn a profit for the first few years.1,5 The financial burden of running a practice includes pressure from the federal government to adopt expensive electronic health record systems to achieve maximum Medicare payment through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, liability insurance, health insurance, and staff salaries.7 These challenges require strong business acumen, including managing overhead costs, navigating insurance negotiations, marketing a practice, and maintaining compliance with evolving health care regulations. The purchase of a $100,000 laser could be a boon or bust, requiring the development of a business plan that ensures a positive return on investment. Additionally, private practice profitability has the potential to dwindle as governmental reimbursements fail to match inflation rates. Securing business advisors or even obtaining a Master of Business Administration degree can be helpful.

Insurance and government agencies also are infringing upon some of the autonomy of private practice dermatologists, as evidenced by a 2017 survey of dermatologists that found that more than half of respondents altered treatment plans based on insurance coverage more than 20% of the time.2 Private equity firms also could infringe on private practice autonomy, as providers are beholden to the firm’s restrictions—from which company’s product will be stocked to which partner will be on call. Lastly, private practice is less conducive to consistent referral patterns and strong relationships with specialists when compared to academic practice. Additionally, reliance on high patient throughput or cosmetic services for financial sustainability can shift focus away from complex medical dermatology, which often is referred to AMCs.

Academic Medicine

Academic dermatology offers a stimulating and collaborative environment with opportunities to advance the field through research and education. Often, the opportunity to teach medical students, residents, and peers is the deciding factor for academic dermatologists, as supported by a 2016 survey that found teaching opportunities are a major influence on career decision.8 The mixture of patient care, education, and research roles can be satisfying when compared to the grind of seeing large numbers of patients every day. Because they typically are salaried with an RVU-based income, academic dermatologists often are less concerned with the costs associated with medical treatment, and they typically treat more medically complex patients and underserved populations.9 The salary structure of academic roles also provides the benefit of a stable and predictable income. Physicians in this setting often are considered experts in their field, positioning them to have a strong built-in referral system along with frequent participation in multidisciplinary care alongside colleagues in rheumatology, oncology, and infectious diseases. The benefits of downstream income from dermatopathology, Mohs surgery, and other ancillary testing can provide great financial advantages for an academic or large group practice.10 Academic medical centers also afford the benefit of resources, such as research offices, clinical trial units, and institutional support for scholarly publication.

Despite its benefits, academic dermatology is not without unique demands. The resources afforded by research work come with grant application deadlines and the pressure to maintain research productivity as measured by grant dollars. Academic providers also must navigate institutional political dynamics and deal with limits on autonomy. Additionally, the administrative burden associated with committee work, mentorship obligations, and publishing requirements further limit clinical time and contribute to burnout. According to Loo et al,5 92% of 89 dermatology department chairmen responding to a poll believed that the lower compensation was the primary factor preventing more residents from pursuing academia.

The adoption of RVU-based and incentive compensation models at many AMCs, along with dwindling government funds available for research, also have created pressure to increase patient volume, sometimes at the expense of teaching and research. Of those academic dermatologists spending more than half their time seeing patients, a majority reported that they lack the time to also conduct research, teach, and mentor students and resident physicians.6 A survey of academic dermatologists suggested that, for those already serving in academic positions, salary was less of a concern than the lack of protected academic time.4 While competing demands can erode the appeal of academic dermatology, academia continues to offer a meaningful and fulfilling career path for those motivated by scholarship, mentorship, teaching opportunities, and systemic impact.

Hybrid and Emerging Models

To reconcile the trade-offs inherent in private and academic models, hybrid roles are becoming increasingly common. In these arrangements, dermatologists split their time between private practice and academic appointments settings, allowing for participation in resident education and research while also benefiting from the operational and financial structure of a private office. In some cases, private groups formally affiliate with academic institutions, creating academic-private practices that host trainees and produce scholarly work while operating financially outside of traditional hospital systems. Individual dermatologists also may choose to accept part-time academic roles that allow residents and medical students to rotate in their offices. Hybrid roles may be of most interest to individuals who feel that they are missing out on the mentorship and teaching opportunities afforded at AMCs.

Government-funded systems such as Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals offer another alternative. Dermatologists at VA hospitals often hold faculty appointments, treat a wide range of conditions in a population with great need, and engage in teaching without the intensity of productivity requirements seen at AMCs. These roles can be attractive to physicians who value public service, work-life balance, and minimal malpractice risk, as well as dermatologists who wish to introduce variety in their practice through an additional clinical setting. Notably, these roles are limited, as roughly 80% of VA hospitals employ part-time dermatologists and 72% reported being understaffed.11 Despite the challenges of limited resources and increased bureaucracy, the VA is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, offering the benefits of protection from most malpractice risk and participation in medical education at 80% of VA hospitals.12 A VA-based practice may be most attractive to physicians with prior military service or those looking for a stable practice that serves the underserved and the mission of medical education.

Similarly, rural health clinics are private practices with special subsidies from the federal government that bring Medicaid payments up to the level of Medicare.13 Rural dermatology also mirrors that of a VA-based practice by offering the opportunity to treat an array of conditions in a population of great need, as rural patients often are in care deserts and would otherwise need to travel for miles to receive dermatologic care. There is a shortage of dermatologists working in rural areas, and rural dermatologists are more likely than those in suburban or urban areas to practice alone.2 Although potentially more physically isolating, rural dermatology offers providers the opportunity to establish a lucrative practice with minimal competition and development of meaningful patient relationships.

The most rapidly increasing practice model emerging in dermatology over the past decade is the private equity (PE) group. Rajabi-Estarabadi et al14 estimated that at least 184 dermatology practices have been acquired by PE groups between 2010 and 2019. An estimated 15% of all PE acquisitions in health care have been within the field of dermatology.9 Private equity firms typically acquire 1 or more practices, then consolidate the operations with the short-term goals of reducing costs and maximizing profits and longer-term goals of selling the practice for further profit in 3 to 7 years.9 They often rely heavily on a dermatologist supervising a number of nurse practitioners.15 While PE acquisition may provide additional financial stability and income, providers have less autonomy and potentially risk a shift in their focus from patient care to profit.

The blurred lines between practice settings reflect a broader shift in the profession. Dermatologists have increasingly crafted flexible, individualized careers that align with their goals and values while drawing from both academic and private models. Hybrid roles may prove critical in preserving the educational and research missions of dermatology while adapting to economic and institutional realities.

Gender Trends, Career Satisfaction, and Other Factors Influencing Career Choice

The gender demographics of dermatology have changed greatly in recent decades. In the years 2010 to 2021, the percentage of women in the field rose from 41% to 52.2%, mirroring the rise in female medical students.16 Despite this, gender disparities persist through differences in pay, promotion rates, leadership opportunities, and research productivity.17 Women who are academic dermatologists are less likely to have protected research time and often shoulder a disproportionate share of mentorship and administrative responsibilities, which frequently are undervalued in promotion and compensation structures. Similarly, women physicians are less likely to own their own private practice.18 Notably, women physicians work part-time more often than their male counterparts, which likely impacts their income.19 Interestingly, no differences were noted in job satisfaction between men and women in academic or private practice settings, suggesting that dermatology is a fulfilling field for female physicians.16 Similar data were observed in the field of dermatopathology; in fact, there is no difference in job satisfaction when comparing providers in academics vs private practice.20

Geographic factors also influence career decisions. Some dermatologists may choose private practice to remain close to family or serve a rural area, while some choose academic centers typically located in major metropolitan areas. Others are drawn to AMCs due to their reputation, resources, or opportunities for specialization. The number of practicing dermatologists in an area also may be considered, as areas with fewer providers likely have more individuals seeking a provider and thus more earning potential.

In summary, career satisfaction is influenced by many factors, including practice setting, colleagues, institutional leadership, work environment, and professional goals. For individuals who are seeking intellectual stimulation and teaching opportunities, academic dermatology may be a great career option. Academic or large group practices may come with a large group of clinical dermatologists to provide a steady stream of specimens. Private practice appeals to those seeking autonomy, reduced bureaucracy, and higher earning potential. Tierney et al21 found that the greatest predictor of a future career in academics among Mohs surgeons was the number of publications a fellow had before and during fellowship training. These data suggest that personal interests greatly influence career decisions.

The Role of Mentorship in Career Decision-Making

Just as personal preferences guide career decisions, so too do interpersonal interactions. Mentorship plays a large role in career success, and the involvement of faculty mentors in society meetings and editorial boards has been shown to positively correlate with the number of residents pursuing academia.14 Similarly, negative interactions have strong impacts, as the top cited reason for Mohs surgeons leaving academia was lack of support from their academic chair.21 While many academic dermatologists report fulfillment from the collegial environment, retention remains an issue. Tierney et al21 found that, among 455 academic Mohs surgeons, only 28% of those who began in academia remained in those roles over the long term, and this trend of low retention holds true across the field of academic dermatology. Lack of autonomy, insufficient institutional support, and more lucrative private practice opportunities were all cited as reasons for leaving. For dermatologists seeking separation from academics but continued research opportunities, data suggest that private practice allows for continued research and publications, indicating that scholarly engagement is not exclusive to academic settings. These trends point to the increasing viability of hybrid or academic-private models that combine academic productivity with greater flexibility and financial stability.

Final Thoughts

Academic and private practice dermatology each offer compelling advantages and distinct challenges (Table). The growing popularity of hybrid models reflects a desire among dermatologists to balance the intellectual fulfillment associated with academic medicine with professional sustainability and autonomy of private practice. Whether through part-time academic appointments, rural health clinics, VA employment, or affiliations between private groups and academic institutions, these emerging roles offer a flexible and adaptive approach to career development.

Ultimately, the ideal practice model is one that aligns with a physician’s personal values, long-term goals, and lifestyle preferences. No single path fits all, but thoughtful career planning supported by mentorship and institutional transparency can help dermatologists thrive in a rapidly evolving health care landscape.

Dermatology is a rapidly growing, highly competitive specialty with patients that can be served via private practice, academic medicine, hybrid settings, and rural health clinics. Medical residents’ choice of a career path has been rapidly evolving alongside shifts in health care policy, increasing demand for dermatologic services, stagnant fees falling behind inflation for more than a decade, and payment methods that no longer reflect the traditional fee-for-service model. This places a lot of pressure on young dermatologists to evaluate which practice structure best fits their career goals. A nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of each practice model is essential for dermatologists to make informed career decisions that are aligned with their values.

While there are many health care practice models, the first decision dermatology residents must make is whether they would prefer working in the private sector or an academic practice. Of course, it is not uncommon for academic dermatologists to embark on a midcareer segue into private practice and, less commonly, for private dermatologists to culminate their careers with a move to academics. The private sector includes private practice, private equity (PE)–owned group practices that often are single-specialty focused, and hospital-owned group practices that usually are multispecialty. Traditionally, private practices are health care businesses owned by one physician (solo practice) or a group of physicians (group practice) operated independently from hospitals, health systems, or private investors. Financially, these practices rely heavily on volume-based services, especially clinic visits and cosmetic procedures, which provide higher reimbursement rates and usually cash payments at the time of service.1 Roughly 35% of dermatologists in the United States work in private practice, and a dwindling 15% work in solo practice.2,3

Medical practices that are not self-owned by physicians vary widely, and they include hospital- or medical center–owned, private equity, and university-based academic practices. Private equity practices typically are characterized as profit driven. Hospital-owned practices shoulder business decisions and administrative duties for the physician at the cost of provider autonomy. Academic medicine is the most different from the other practice types. In contrast to private practice dermatologists, university-based dermatologists practice at academic medical centers (AMCs) with the core goals of patient care, education, and research. Compensation generally is based on the relative value unit (RVU), which is supplemented by government support and research grants.

As evidenced in this brief discussion, health care practice models are complex, and choosing the right model to align with professional goals can pose a major challenge for many physicians. The advantages and disadvantages of various practice models will be reviewed, highlighting trends and emerging models.

Solo or Small-Group Single-Specialty Private Practice

Private practice offers dermatologists the advantage of higher income potential but with greater economic risk; it often requires physicians to be more involved in the business aspects of dermatologic practice. In the early 1990s, a survey of private practice dermatologists revealed that income was the first or second most important factor that contributed to their career choice of private vs academic practice.4 Earning potential in private practice largely is driven by the autonomy afforded in this setting. Physicians have the liberty of choosing their practice location, structure, schedule, and staff in addition to tailoring services toward profitability; this typically leads to a higher volume of cosmetic and procedural visits, which may be attractive to providers wishing to focus on aesthetics. Private practice dermatologists also are not subject to institutional requirements that may include the preparation of grant submissions, research productivity targets, and devotion of time to teaching. Many private dermatologists find satisfaction in tailoring their work environments to align with personal values and goals and in cultivating long-term relationships with patients in a more personal and less bureaucratic context.

There also are drawbacks to private practice. The profitability often can be attributed to the higher patient load and more hours devoted to practice.5 A 2006 study found that academics saw 32% to 41% fewer patients per week than private practice dermatologists.6 Along with the opportunity for financial gain is the risk of financial ruin. Cost is the largest hurdle for establishing a practice, and most practices do not turn a profit for the first few years.1,5 The financial burden of running a practice includes pressure from the federal government to adopt expensive electronic health record systems to achieve maximum Medicare payment through the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, liability insurance, health insurance, and staff salaries.7 These challenges require strong business acumen, including managing overhead costs, navigating insurance negotiations, marketing a practice, and maintaining compliance with evolving health care regulations. The purchase of a $100,000 laser could be a boon or bust, requiring the development of a business plan that ensures a positive return on investment. Additionally, private practice profitability has the potential to dwindle as governmental reimbursements fail to match inflation rates. Securing business advisors or even obtaining a Master of Business Administration degree can be helpful.

Insurance and government agencies also are infringing upon some of the autonomy of private practice dermatologists, as evidenced by a 2017 survey of dermatologists that found that more than half of respondents altered treatment plans based on insurance coverage more than 20% of the time.2 Private equity firms also could infringe on private practice autonomy, as providers are beholden to the firm’s restrictions—from which company’s product will be stocked to which partner will be on call. Lastly, private practice is less conducive to consistent referral patterns and strong relationships with specialists when compared to academic practice. Additionally, reliance on high patient throughput or cosmetic services for financial sustainability can shift focus away from complex medical dermatology, which often is referred to AMCs.

Academic Medicine

Academic dermatology offers a stimulating and collaborative environment with opportunities to advance the field through research and education. Often, the opportunity to teach medical students, residents, and peers is the deciding factor for academic dermatologists, as supported by a 2016 survey that found teaching opportunities are a major influence on career decision.8 The mixture of patient care, education, and research roles can be satisfying when compared to the grind of seeing large numbers of patients every day. Because they typically are salaried with an RVU-based income, academic dermatologists often are less concerned with the costs associated with medical treatment, and they typically treat more medically complex patients and underserved populations.9 The salary structure of academic roles also provides the benefit of a stable and predictable income. Physicians in this setting often are considered experts in their field, positioning them to have a strong built-in referral system along with frequent participation in multidisciplinary care alongside colleagues in rheumatology, oncology, and infectious diseases. The benefits of downstream income from dermatopathology, Mohs surgery, and other ancillary testing can provide great financial advantages for an academic or large group practice.10 Academic medical centers also afford the benefit of resources, such as research offices, clinical trial units, and institutional support for scholarly publication.

Despite its benefits, academic dermatology is not without unique demands. The resources afforded by research work come with grant application deadlines and the pressure to maintain research productivity as measured by grant dollars. Academic providers also must navigate institutional political dynamics and deal with limits on autonomy. Additionally, the administrative burden associated with committee work, mentorship obligations, and publishing requirements further limit clinical time and contribute to burnout. According to Loo et al,5 92% of 89 dermatology department chairmen responding to a poll believed that the lower compensation was the primary factor preventing more residents from pursuing academia.

The adoption of RVU-based and incentive compensation models at many AMCs, along with dwindling government funds available for research, also have created pressure to increase patient volume, sometimes at the expense of teaching and research. Of those academic dermatologists spending more than half their time seeing patients, a majority reported that they lack the time to also conduct research, teach, and mentor students and resident physicians.6 A survey of academic dermatologists suggested that, for those already serving in academic positions, salary was less of a concern than the lack of protected academic time.4 While competing demands can erode the appeal of academic dermatology, academia continues to offer a meaningful and fulfilling career path for those motivated by scholarship, mentorship, teaching opportunities, and systemic impact.

Hybrid and Emerging Models

To reconcile the trade-offs inherent in private and academic models, hybrid roles are becoming increasingly common. In these arrangements, dermatologists split their time between private practice and academic appointments settings, allowing for participation in resident education and research while also benefiting from the operational and financial structure of a private office. In some cases, private groups formally affiliate with academic institutions, creating academic-private practices that host trainees and produce scholarly work while operating financially outside of traditional hospital systems. Individual dermatologists also may choose to accept part-time academic roles that allow residents and medical students to rotate in their offices. Hybrid roles may be of most interest to individuals who feel that they are missing out on the mentorship and teaching opportunities afforded at AMCs.

Government-funded systems such as Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals offer another alternative. Dermatologists at VA hospitals often hold faculty appointments, treat a wide range of conditions in a population with great need, and engage in teaching without the intensity of productivity requirements seen at AMCs. These roles can be attractive to physicians who value public service, work-life balance, and minimal malpractice risk, as well as dermatologists who wish to introduce variety in their practice through an additional clinical setting. Notably, these roles are limited, as roughly 80% of VA hospitals employ part-time dermatologists and 72% reported being understaffed.11 Despite the challenges of limited resources and increased bureaucracy, the VA is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, offering the benefits of protection from most malpractice risk and participation in medical education at 80% of VA hospitals.12 A VA-based practice may be most attractive to physicians with prior military service or those looking for a stable practice that serves the underserved and the mission of medical education.

Similarly, rural health clinics are private practices with special subsidies from the federal government that bring Medicaid payments up to the level of Medicare.13 Rural dermatology also mirrors that of a VA-based practice by offering the opportunity to treat an array of conditions in a population of great need, as rural patients often are in care deserts and would otherwise need to travel for miles to receive dermatologic care. There is a shortage of dermatologists working in rural areas, and rural dermatologists are more likely than those in suburban or urban areas to practice alone.2 Although potentially more physically isolating, rural dermatology offers providers the opportunity to establish a lucrative practice with minimal competition and development of meaningful patient relationships.

The most rapidly increasing practice model emerging in dermatology over the past decade is the private equity (PE) group. Rajabi-Estarabadi et al14 estimated that at least 184 dermatology practices have been acquired by PE groups between 2010 and 2019. An estimated 15% of all PE acquisitions in health care have been within the field of dermatology.9 Private equity firms typically acquire 1 or more practices, then consolidate the operations with the short-term goals of reducing costs and maximizing profits and longer-term goals of selling the practice for further profit in 3 to 7 years.9 They often rely heavily on a dermatologist supervising a number of nurse practitioners.15 While PE acquisition may provide additional financial stability and income, providers have less autonomy and potentially risk a shift in their focus from patient care to profit.

The blurred lines between practice settings reflect a broader shift in the profession. Dermatologists have increasingly crafted flexible, individualized careers that align with their goals and values while drawing from both academic and private models. Hybrid roles may prove critical in preserving the educational and research missions of dermatology while adapting to economic and institutional realities.

Gender Trends, Career Satisfaction, and Other Factors Influencing Career Choice

The gender demographics of dermatology have changed greatly in recent decades. In the years 2010 to 2021, the percentage of women in the field rose from 41% to 52.2%, mirroring the rise in female medical students.16 Despite this, gender disparities persist through differences in pay, promotion rates, leadership opportunities, and research productivity.17 Women who are academic dermatologists are less likely to have protected research time and often shoulder a disproportionate share of mentorship and administrative responsibilities, which frequently are undervalued in promotion and compensation structures. Similarly, women physicians are less likely to own their own private practice.18 Notably, women physicians work part-time more often than their male counterparts, which likely impacts their income.19 Interestingly, no differences were noted in job satisfaction between men and women in academic or private practice settings, suggesting that dermatology is a fulfilling field for female physicians.16 Similar data were observed in the field of dermatopathology; in fact, there is no difference in job satisfaction when comparing providers in academics vs private practice.20

Geographic factors also influence career decisions. Some dermatologists may choose private practice to remain close to family or serve a rural area, while some choose academic centers typically located in major metropolitan areas. Others are drawn to AMCs due to their reputation, resources, or opportunities for specialization. The number of practicing dermatologists in an area also may be considered, as areas with fewer providers likely have more individuals seeking a provider and thus more earning potential.

In summary, career satisfaction is influenced by many factors, including practice setting, colleagues, institutional leadership, work environment, and professional goals. For individuals who are seeking intellectual stimulation and teaching opportunities, academic dermatology may be a great career option. Academic or large group practices may come with a large group of clinical dermatologists to provide a steady stream of specimens. Private practice appeals to those seeking autonomy, reduced bureaucracy, and higher earning potential. Tierney et al21 found that the greatest predictor of a future career in academics among Mohs surgeons was the number of publications a fellow had before and during fellowship training. These data suggest that personal interests greatly influence career decisions.

The Role of Mentorship in Career Decision-Making

Just as personal preferences guide career decisions, so too do interpersonal interactions. Mentorship plays a large role in career success, and the involvement of faculty mentors in society meetings and editorial boards has been shown to positively correlate with the number of residents pursuing academia.14 Similarly, negative interactions have strong impacts, as the top cited reason for Mohs surgeons leaving academia was lack of support from their academic chair.21 While many academic dermatologists report fulfillment from the collegial environment, retention remains an issue. Tierney et al21 found that, among 455 academic Mohs surgeons, only 28% of those who began in academia remained in those roles over the long term, and this trend of low retention holds true across the field of academic dermatology. Lack of autonomy, insufficient institutional support, and more lucrative private practice opportunities were all cited as reasons for leaving. For dermatologists seeking separation from academics but continued research opportunities, data suggest that private practice allows for continued research and publications, indicating that scholarly engagement is not exclusive to academic settings. These trends point to the increasing viability of hybrid or academic-private models that combine academic productivity with greater flexibility and financial stability.

Final Thoughts

Academic and private practice dermatology each offer compelling advantages and distinct challenges (Table). The growing popularity of hybrid models reflects a desire among dermatologists to balance the intellectual fulfillment associated with academic medicine with professional sustainability and autonomy of private practice. Whether through part-time academic appointments, rural health clinics, VA employment, or affiliations between private groups and academic institutions, these emerging roles offer a flexible and adaptive approach to career development.

Ultimately, the ideal practice model is one that aligns with a physician’s personal values, long-term goals, and lifestyle preferences. No single path fits all, but thoughtful career planning supported by mentorship and institutional transparency can help dermatologists thrive in a rapidly evolving health care landscape.

- Kaplan J. Part I: private practice versus academic medicine. BoardVitals Blog. June 5, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.boardvitals.com/blog/private-practice-academic-medicine/

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Parthasarathy V, Pollock JR, McNeely GL, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of trends in dermatology practice size in the United States from 2012 to 2020. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;315:223-229. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02344-0

- Bergstresser PR. Perceptions of the academic environment: a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1092-1096. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70311-o

- Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower: issues of recruitment and retention. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.341

- Resneck JS, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.013

- Salmen N, Brodell R, Brodell Dolohanty L. The electronic health record: should small practices adopt this technology? J of Skin. 2024;8:1269-1273. doi:10.25251/skin.8.1.8

- Morales-Pico BM, Cotton CC, Morrell DS. Factors correlated with residents’ decisions to enter academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7295783b.

- DeWane ME, Mostow E, Grant-Kels JM. The corporatization of care in academic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:289-295. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.003

- Pearlman RL, Nahar VK, Sisson WT, et al. Understanding downstream service profitability generated by dermatology faculty in an academic medical center: a key driver to promotion of access-to-care. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1425-1427. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02406-3

- Huang WW, Tsoukas MM, Bhutani T, et al. Benchmarking U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs dermatologic services: a nationwide survey of VA dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:50-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.035

- 20 reasons doctors like working for the Veterans Health Administration. US Department of Veterans Affairs. August 2016. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/20ReasonsVHA_508_IB10935.pdf

- Rural health clinics (RHCs). Rural Health Information Hub. Updated April 7, 2025. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www .ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-clinics

- Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Jones VA, Zheng C, et al. Dermatologist transitions: academics into private practices and vice versa. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:541-546. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.05.012

- Bruch JD, Foot C, Singh Y, et al. Workforce composition in private equity–acquired versus non–private equity–acquired physician practices. Health Affairs. 2023;42:121-129. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00308

- Zlakishvili B, Horev A. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research over the past 15 years. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:e160. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000160

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Levender MM, et al. Practice patterns and job satisfaction of Mohs surgeons: a gender-based survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1103-1108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29140863/

- Kane CK. Policy Research Perspectives. Recent changes in physician practice arrangements: shifts away from private practice and towards larger practice size continue through 2022. American Medical Association website. 2023. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2022-prp-practice-arrangement.pdf

- Frank E, Zhao Z, Sen S, et al. Gender disparities in work and parental status among early career physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198340. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8340

- Boyd AS, Fang F. A survey-based evaluation of dermatopathology in the United States. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:173-176. doi:10.1097/dad.0b013e3181f0ed84

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW, Kimball AB. Career trajectory and job satisfaction trends in Mohs micrographic surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1229-1238. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02076.x

- Kaplan J. Part I: private practice versus academic medicine. BoardVitals Blog. June 5, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.boardvitals.com/blog/private-practice-academic-medicine/

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Parthasarathy V, Pollock JR, McNeely GL, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of trends in dermatology practice size in the United States from 2012 to 2020. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;315:223-229. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02344-0

- Bergstresser PR. Perceptions of the academic environment: a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1092-1096. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70311-o

- Loo DS, Liu CL, Geller AC, et al. Academic dermatology manpower: issues of recruitment and retention. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:341-347. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.341

- Resneck JS, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.013

- Salmen N, Brodell R, Brodell Dolohanty L. The electronic health record: should small practices adopt this technology? J of Skin. 2024;8:1269-1273. doi:10.25251/skin.8.1.8

- Morales-Pico BM, Cotton CC, Morrell DS. Factors correlated with residents’ decisions to enter academic dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7295783b.

- DeWane ME, Mostow E, Grant-Kels JM. The corporatization of care in academic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:289-295. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.003

- Pearlman RL, Nahar VK, Sisson WT, et al. Understanding downstream service profitability generated by dermatology faculty in an academic medical center: a key driver to promotion of access-to-care. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1425-1427. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02406-3

- Huang WW, Tsoukas MM, Bhutani T, et al. Benchmarking U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs dermatologic services: a nationwide survey of VA dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:50-54. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.035

- 20 reasons doctors like working for the Veterans Health Administration. US Department of Veterans Affairs. August 2016. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/20ReasonsVHA_508_IB10935.pdf

- Rural health clinics (RHCs). Rural Health Information Hub. Updated April 7, 2025. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www .ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-clinics

- Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Jones VA, Zheng C, et al. Dermatologist transitions: academics into private practices and vice versa. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:541-546. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.05.012

- Bruch JD, Foot C, Singh Y, et al. Workforce composition in private equity–acquired versus non–private equity–acquired physician practices. Health Affairs. 2023;42:121-129. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00308

- Zlakishvili B, Horev A. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research over the past 15 years. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:e160. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000160

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Levender MM, et al. Practice patterns and job satisfaction of Mohs surgeons: a gender-based survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1103-1108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29140863/

- Kane CK. Policy Research Perspectives. Recent changes in physician practice arrangements: shifts away from private practice and towards larger practice size continue through 2022. American Medical Association website. 2023. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2022-prp-practice-arrangement.pdf

- Frank E, Zhao Z, Sen S, et al. Gender disparities in work and parental status among early career physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198340. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8340

- Boyd AS, Fang F. A survey-based evaluation of dermatopathology in the United States. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:173-176. doi:10.1097/dad.0b013e3181f0ed84

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW, Kimball AB. Career trajectory and job satisfaction trends in Mohs micrographic surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1229-1238. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02076.x

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

Advantages and Disadvantages of Private vs Academic Dermatology Practices

PRACTICE POINTS

- In the field of dermatology, solo and small-group single-specialty private practices are shrinking while academic medicine is growing.

- Hybrid models reflect a desire among some dermatologists to balance the intellectual fulfillment and sustainability associated with academic medicine and the professional autonomy of private practice.

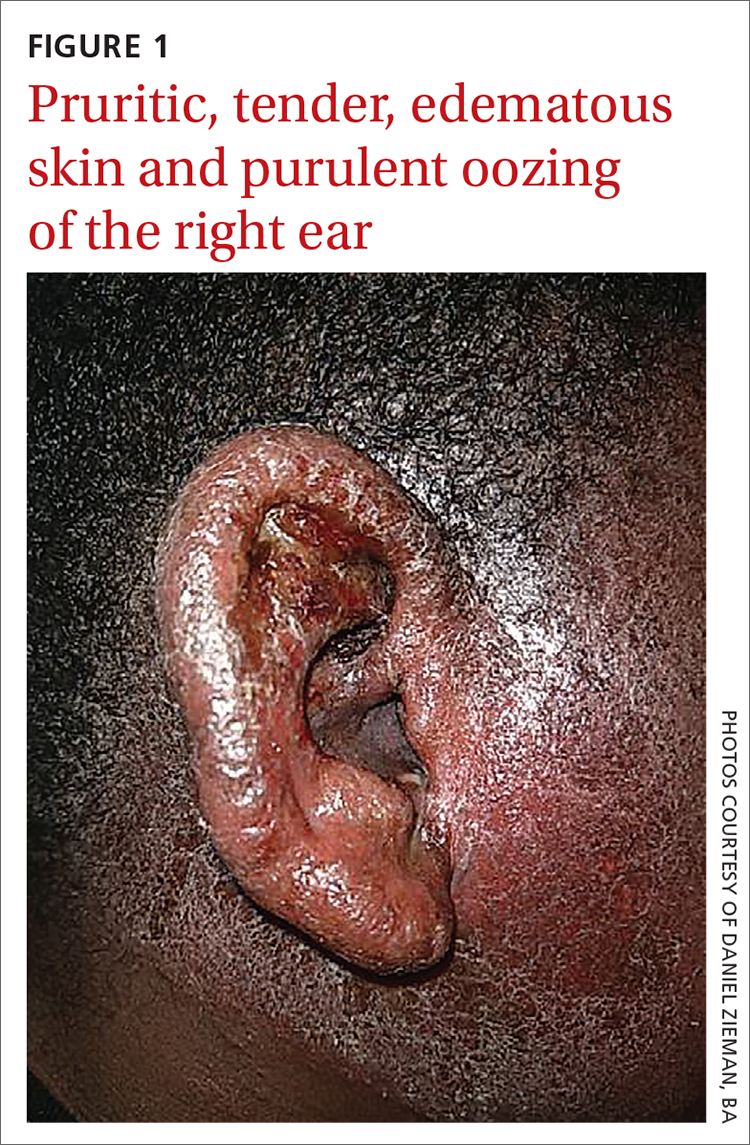

Erythematous ear with drainage

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

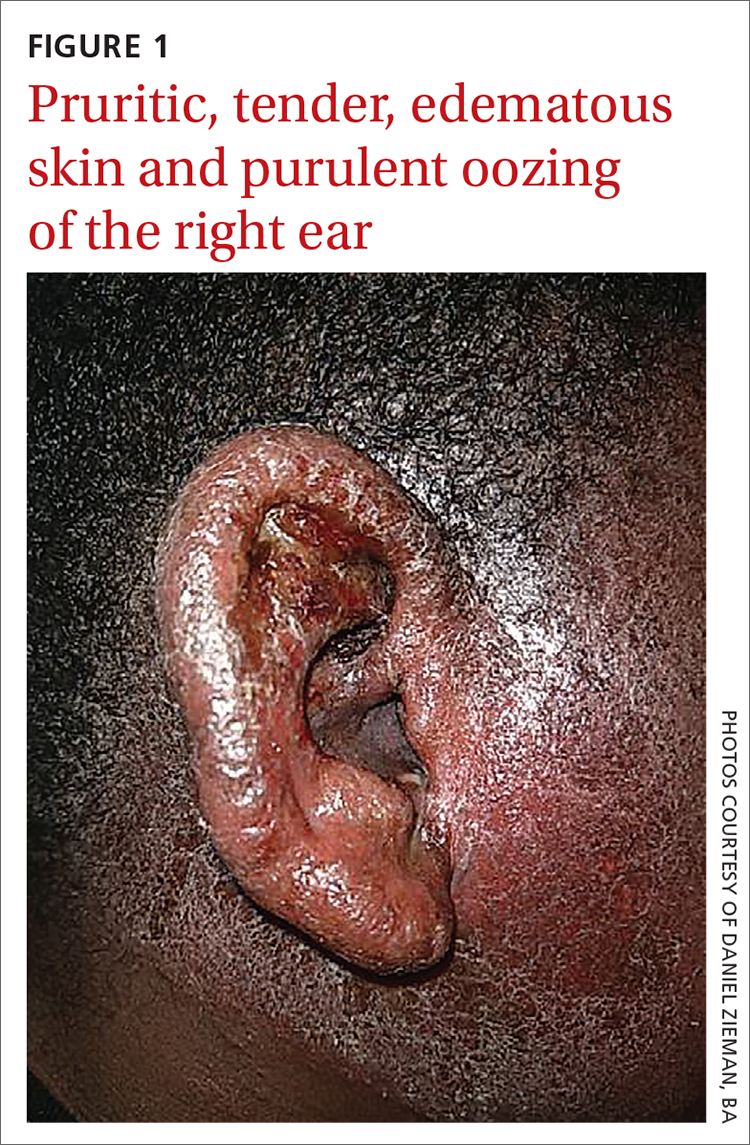

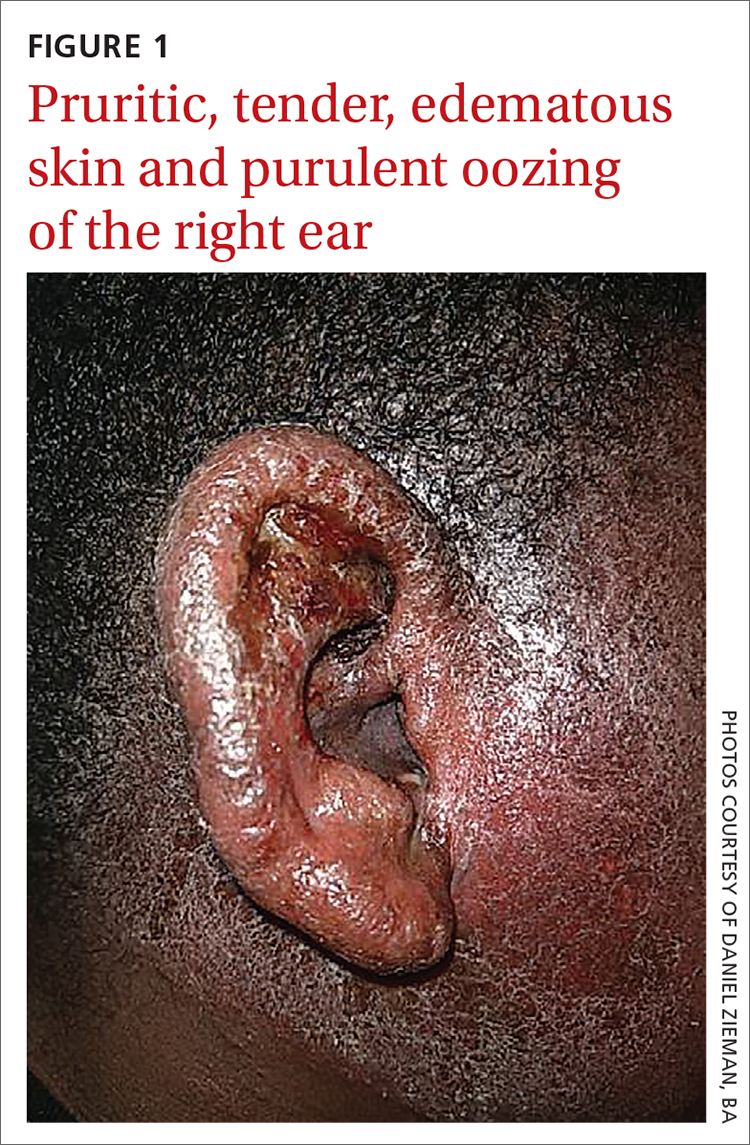

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

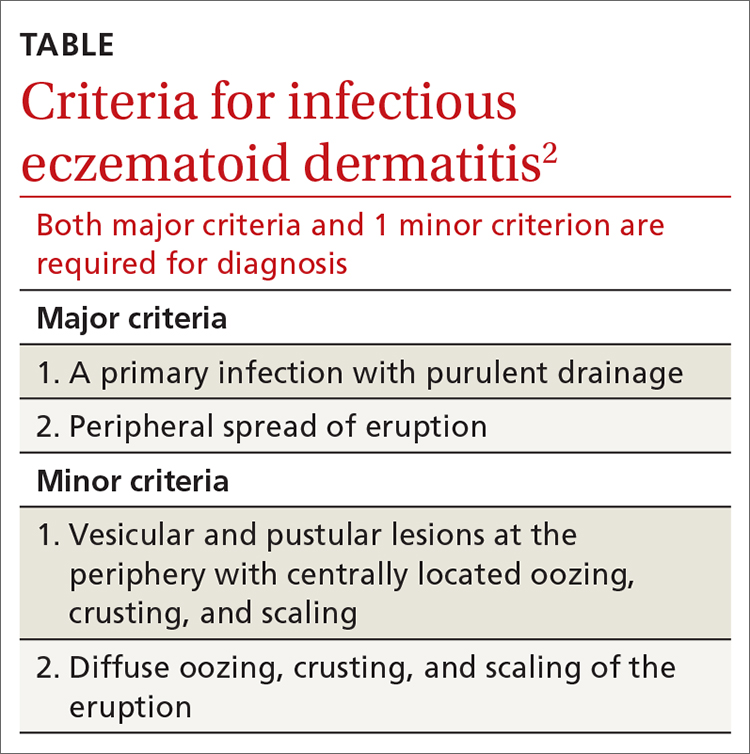

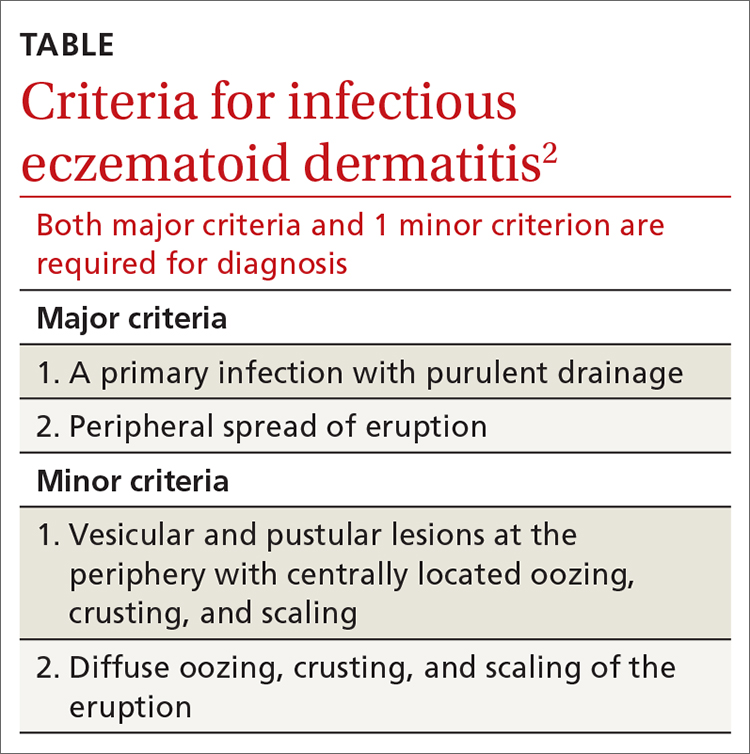

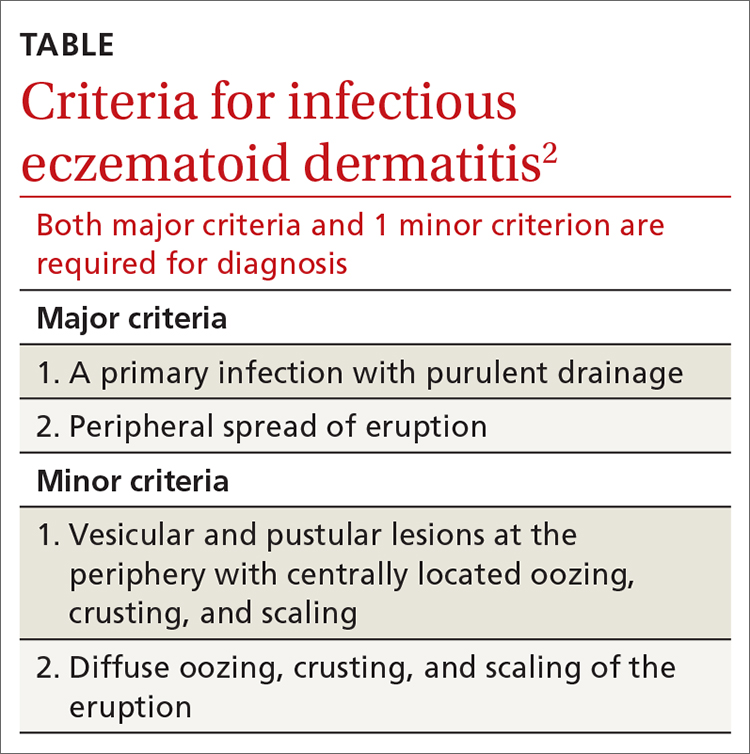

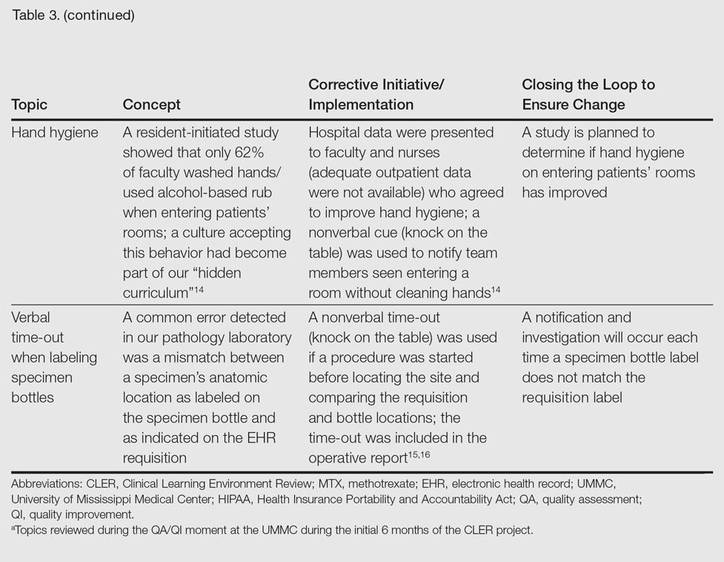

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

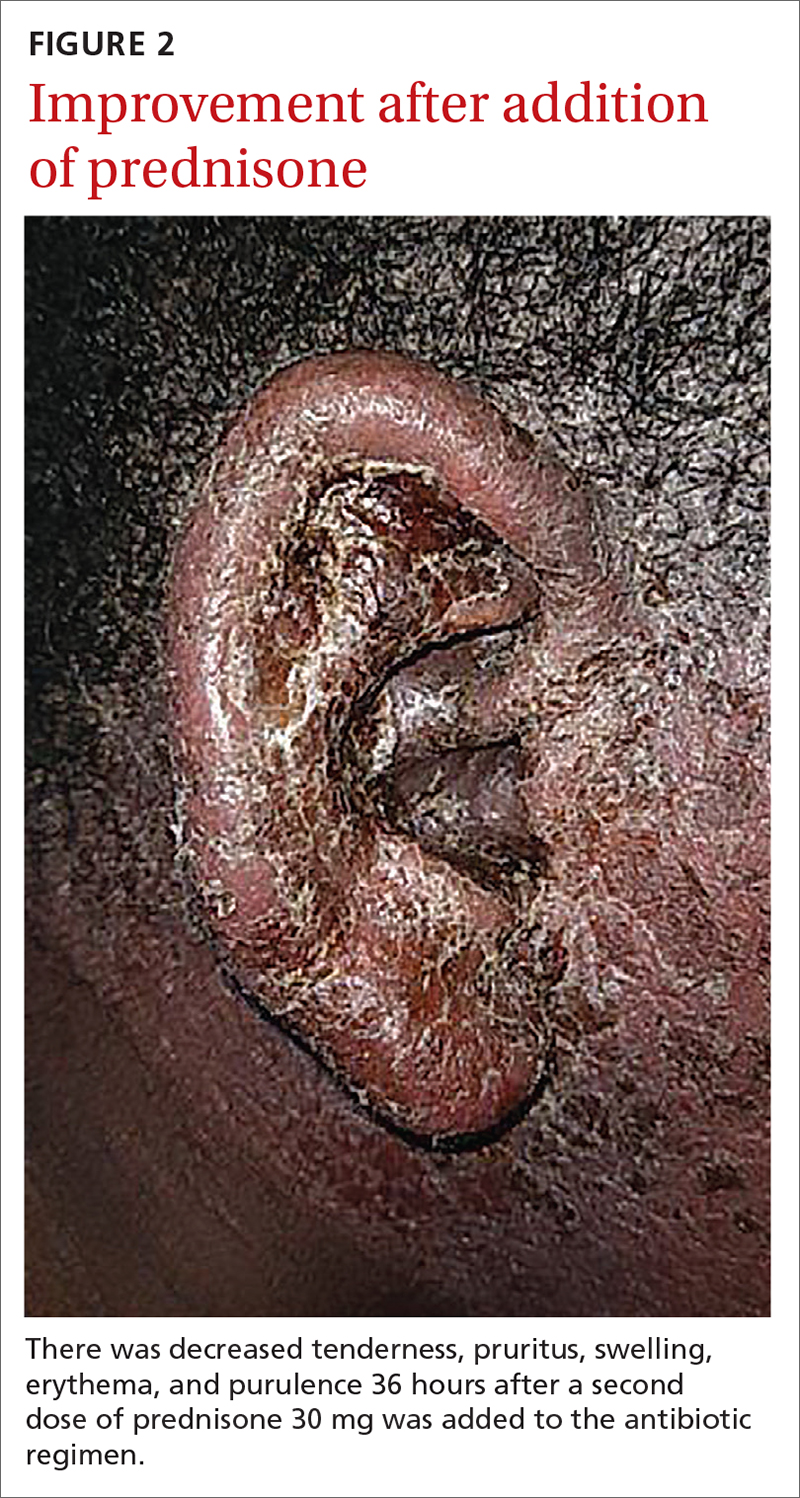

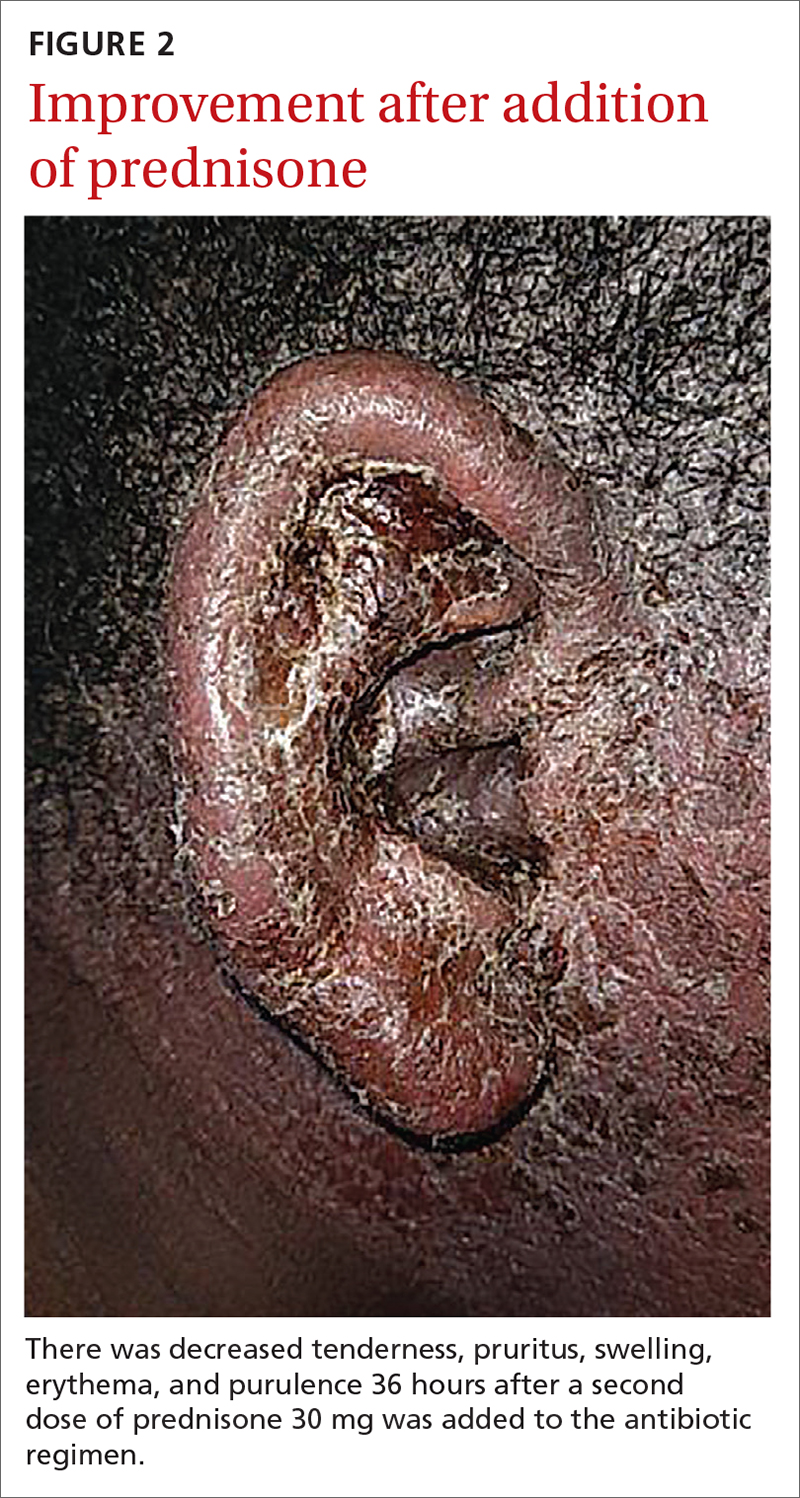

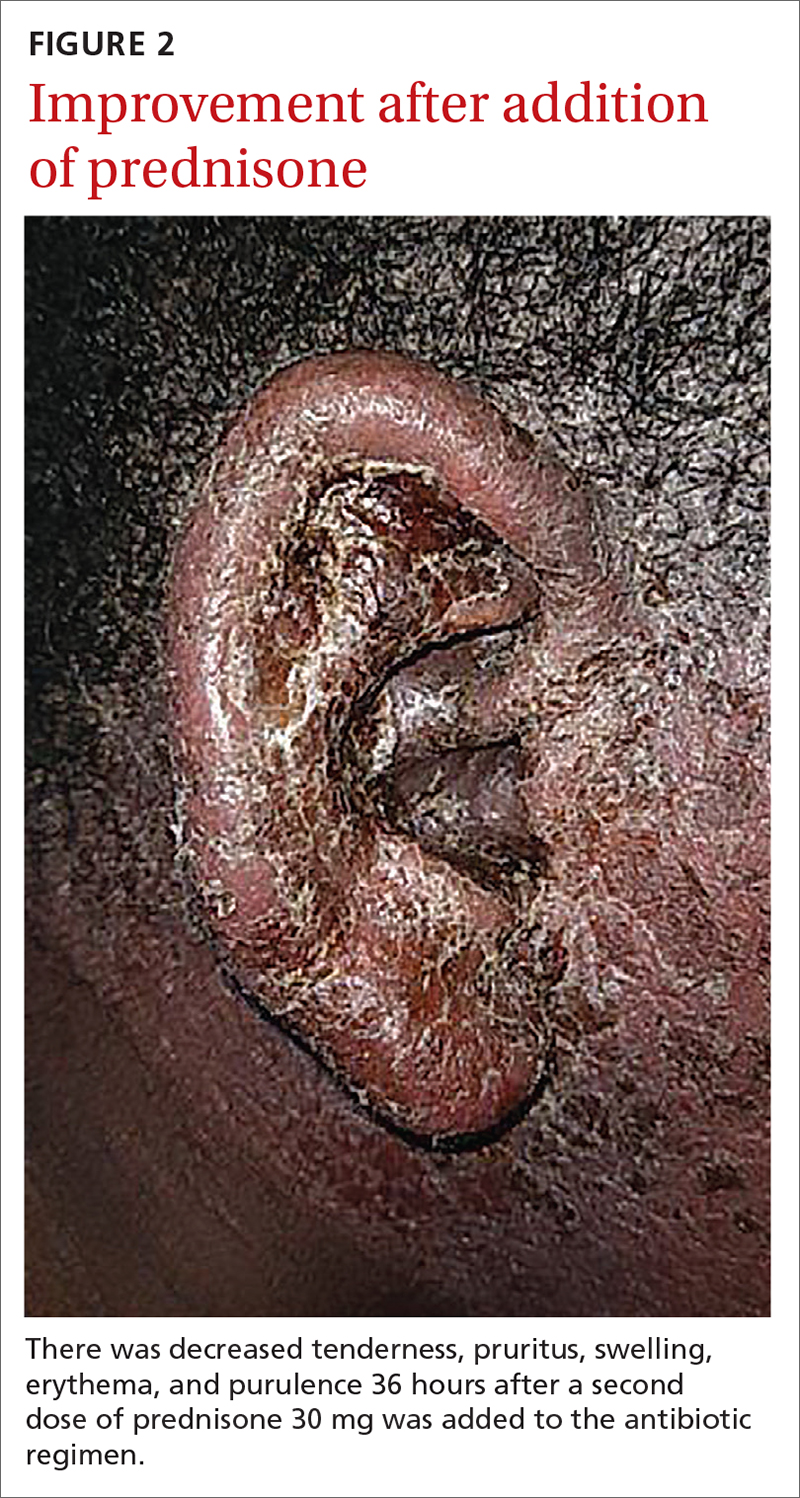

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus