User login

Losing Your Mind Trying to Understand the BP-Dementia Link

You could be forgiven if you are confused about how blood pressure (BP) affects dementia. First, you read an article extolling the benefits of BP lowering, then a study about how stopping antihypertensives slows cognitive decline in nursing home residents. It’s enough to make you lose your mind.

The Brain Benefits of BP Lowering

It should be stated unequivocally that you should absolutely treat high BP. It may have once been acceptable to state, “The greatest danger to a man with high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it.” But those dark days are long behind us.

In these divided times, at least we can agree that we should treat high BP. The cardiovascular (CV) benefits, in and of themselves, justify the decision. But BP’s relationship with dementia is more complex. There are different types of dementia even though we tend to lump them all into one category. Vascular dementia is driven by the same pathophysiology and risk factors as cardiac disease. It’s intuitive that treating hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking will decrease the risk for stroke and limit the damage to the brain that we see with repeated vascular insults. For Alzheimer’s disease, high BP and other CV risk factors seem to increase the risk even if the mechanism is not fully elucidated.

Estimates suggest that if we could lower the prevalence of hypertension by 25%, there would be 160,000 fewer cases of Alzheimer’s disease. But the data are not as robust as one might hope. A 2021 Cochrane review found that hypertension treatment slowed cognitive decline, but the quality of the evidence was low. Short duration of follow-up, dropouts, crossovers, and other problems with the data precluded any certainty. What’s more, hypertension in midlife is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, but its impact in those over age 70 is less clear. Later in life, or once cognitive impairment has already developed, it may be too late for BP lowering to have any impact.

Potential Harms of Lowering BP

All this needs to be weighed against the potential harms of treating hypertension. I will reiterate that hypertension should be treated and treated aggressively for the prevention of CV events. But overtreatment, especially in older patients, is associated with hypotension, falls, and syncope. Older patients are also at risk for polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions.

A Korean nationwide survey showed a U-shaped association between BP and Alzheimer’s disease risk in adults (mean age, 67 years), with both high and low BPs associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Though not all studies agree. A post hoc analysis of SPRINT MIND did not find any negative impact of intensive BP lowering on cognitive outcomes or cerebral perfusion in older adults (mean age, 68 years). But it didn’t do much good either. Given the heterogeneity of the data, doubts remain on whether aggressive BP lowering might be detrimental in older patients with comorbidities and preexisting dementia. The obvious corollary then is whether deprescribing hypertensive medications could be beneficial.

A recent publication in JAMA Internal Medicine attempted to address this very question. The cohort study used data from Veterans Affairs nursing home residents (mean age, 78 years) to emulate a randomized trial on deprescribing antihypertensives and cognitive decline. Many of the residents’ cognitive scores worsened over the course of follow-up; however, the decline was less pronounced in the deprescribing group (10% vs 12%). The same group did a similar analysis looking at CV outcomes and found no increased risk for heart attack or stroke with deprescribing BP medications. Taken together, these nursing home data suggest that deprescribing may help slow cognitive decline without the expected trade-off of increased CV events.

Deprescribing, Yes or No?

However, randomized data would obviously be preferable, and these are in short supply. One such trial, the DANTE study, found no benefit to deprescribing in terms of cognition in adults aged 75 years or older with mild cognitive impairment. The study follow-up was only 16 weeks, however, which is hardly enough time to demonstrate any effect, positive or negative. The most that can be said is that it didn’t cause many short-term adverse events.

Perhaps the best conclusion to draw from this somewhat underwhelming collection of data is that lowering high BP is important, but less important the closer we get to the end of life. Hypotension is obviously bad, and overly aggressive BP lowering is going to lead to negative outcomes in older adults because gravity is an unforgiving mistress.

Deprescribing antihypertensives in older adults is probably not going to cause major negative outcomes, but whether it will do much good in nonhypotensive patients is debatable. The bigger problem is the millions of people with undiagnosed or undertreated hypertension. We would probably have less dementia if we treated hypertension when it does the most good: as a primary-prevention strategy in midlife.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

You could be forgiven if you are confused about how blood pressure (BP) affects dementia. First, you read an article extolling the benefits of BP lowering, then a study about how stopping antihypertensives slows cognitive decline in nursing home residents. It’s enough to make you lose your mind.

The Brain Benefits of BP Lowering

It should be stated unequivocally that you should absolutely treat high BP. It may have once been acceptable to state, “The greatest danger to a man with high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it.” But those dark days are long behind us.

In these divided times, at least we can agree that we should treat high BP. The cardiovascular (CV) benefits, in and of themselves, justify the decision. But BP’s relationship with dementia is more complex. There are different types of dementia even though we tend to lump them all into one category. Vascular dementia is driven by the same pathophysiology and risk factors as cardiac disease. It’s intuitive that treating hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking will decrease the risk for stroke and limit the damage to the brain that we see with repeated vascular insults. For Alzheimer’s disease, high BP and other CV risk factors seem to increase the risk even if the mechanism is not fully elucidated.

Estimates suggest that if we could lower the prevalence of hypertension by 25%, there would be 160,000 fewer cases of Alzheimer’s disease. But the data are not as robust as one might hope. A 2021 Cochrane review found that hypertension treatment slowed cognitive decline, but the quality of the evidence was low. Short duration of follow-up, dropouts, crossovers, and other problems with the data precluded any certainty. What’s more, hypertension in midlife is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, but its impact in those over age 70 is less clear. Later in life, or once cognitive impairment has already developed, it may be too late for BP lowering to have any impact.

Potential Harms of Lowering BP

All this needs to be weighed against the potential harms of treating hypertension. I will reiterate that hypertension should be treated and treated aggressively for the prevention of CV events. But overtreatment, especially in older patients, is associated with hypotension, falls, and syncope. Older patients are also at risk for polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions.

A Korean nationwide survey showed a U-shaped association between BP and Alzheimer’s disease risk in adults (mean age, 67 years), with both high and low BPs associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Though not all studies agree. A post hoc analysis of SPRINT MIND did not find any negative impact of intensive BP lowering on cognitive outcomes or cerebral perfusion in older adults (mean age, 68 years). But it didn’t do much good either. Given the heterogeneity of the data, doubts remain on whether aggressive BP lowering might be detrimental in older patients with comorbidities and preexisting dementia. The obvious corollary then is whether deprescribing hypertensive medications could be beneficial.

A recent publication in JAMA Internal Medicine attempted to address this very question. The cohort study used data from Veterans Affairs nursing home residents (mean age, 78 years) to emulate a randomized trial on deprescribing antihypertensives and cognitive decline. Many of the residents’ cognitive scores worsened over the course of follow-up; however, the decline was less pronounced in the deprescribing group (10% vs 12%). The same group did a similar analysis looking at CV outcomes and found no increased risk for heart attack or stroke with deprescribing BP medications. Taken together, these nursing home data suggest that deprescribing may help slow cognitive decline without the expected trade-off of increased CV events.

Deprescribing, Yes or No?

However, randomized data would obviously be preferable, and these are in short supply. One such trial, the DANTE study, found no benefit to deprescribing in terms of cognition in adults aged 75 years or older with mild cognitive impairment. The study follow-up was only 16 weeks, however, which is hardly enough time to demonstrate any effect, positive or negative. The most that can be said is that it didn’t cause many short-term adverse events.

Perhaps the best conclusion to draw from this somewhat underwhelming collection of data is that lowering high BP is important, but less important the closer we get to the end of life. Hypotension is obviously bad, and overly aggressive BP lowering is going to lead to negative outcomes in older adults because gravity is an unforgiving mistress.

Deprescribing antihypertensives in older adults is probably not going to cause major negative outcomes, but whether it will do much good in nonhypotensive patients is debatable. The bigger problem is the millions of people with undiagnosed or undertreated hypertension. We would probably have less dementia if we treated hypertension when it does the most good: as a primary-prevention strategy in midlife.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

You could be forgiven if you are confused about how blood pressure (BP) affects dementia. First, you read an article extolling the benefits of BP lowering, then a study about how stopping antihypertensives slows cognitive decline in nursing home residents. It’s enough to make you lose your mind.

The Brain Benefits of BP Lowering

It should be stated unequivocally that you should absolutely treat high BP. It may have once been acceptable to state, “The greatest danger to a man with high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it.” But those dark days are long behind us.

In these divided times, at least we can agree that we should treat high BP. The cardiovascular (CV) benefits, in and of themselves, justify the decision. But BP’s relationship with dementia is more complex. There are different types of dementia even though we tend to lump them all into one category. Vascular dementia is driven by the same pathophysiology and risk factors as cardiac disease. It’s intuitive that treating hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking will decrease the risk for stroke and limit the damage to the brain that we see with repeated vascular insults. For Alzheimer’s disease, high BP and other CV risk factors seem to increase the risk even if the mechanism is not fully elucidated.

Estimates suggest that if we could lower the prevalence of hypertension by 25%, there would be 160,000 fewer cases of Alzheimer’s disease. But the data are not as robust as one might hope. A 2021 Cochrane review found that hypertension treatment slowed cognitive decline, but the quality of the evidence was low. Short duration of follow-up, dropouts, crossovers, and other problems with the data precluded any certainty. What’s more, hypertension in midlife is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, but its impact in those over age 70 is less clear. Later in life, or once cognitive impairment has already developed, it may be too late for BP lowering to have any impact.

Potential Harms of Lowering BP

All this needs to be weighed against the potential harms of treating hypertension. I will reiterate that hypertension should be treated and treated aggressively for the prevention of CV events. But overtreatment, especially in older patients, is associated with hypotension, falls, and syncope. Older patients are also at risk for polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions.

A Korean nationwide survey showed a U-shaped association between BP and Alzheimer’s disease risk in adults (mean age, 67 years), with both high and low BPs associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Though not all studies agree. A post hoc analysis of SPRINT MIND did not find any negative impact of intensive BP lowering on cognitive outcomes or cerebral perfusion in older adults (mean age, 68 years). But it didn’t do much good either. Given the heterogeneity of the data, doubts remain on whether aggressive BP lowering might be detrimental in older patients with comorbidities and preexisting dementia. The obvious corollary then is whether deprescribing hypertensive medications could be beneficial.

A recent publication in JAMA Internal Medicine attempted to address this very question. The cohort study used data from Veterans Affairs nursing home residents (mean age, 78 years) to emulate a randomized trial on deprescribing antihypertensives and cognitive decline. Many of the residents’ cognitive scores worsened over the course of follow-up; however, the decline was less pronounced in the deprescribing group (10% vs 12%). The same group did a similar analysis looking at CV outcomes and found no increased risk for heart attack or stroke with deprescribing BP medications. Taken together, these nursing home data suggest that deprescribing may help slow cognitive decline without the expected trade-off of increased CV events.

Deprescribing, Yes or No?

However, randomized data would obviously be preferable, and these are in short supply. One such trial, the DANTE study, found no benefit to deprescribing in terms of cognition in adults aged 75 years or older with mild cognitive impairment. The study follow-up was only 16 weeks, however, which is hardly enough time to demonstrate any effect, positive or negative. The most that can be said is that it didn’t cause many short-term adverse events.

Perhaps the best conclusion to draw from this somewhat underwhelming collection of data is that lowering high BP is important, but less important the closer we get to the end of life. Hypotension is obviously bad, and overly aggressive BP lowering is going to lead to negative outcomes in older adults because gravity is an unforgiving mistress.

Deprescribing antihypertensives in older adults is probably not going to cause major negative outcomes, but whether it will do much good in nonhypotensive patients is debatable. The bigger problem is the millions of people with undiagnosed or undertreated hypertension. We would probably have less dementia if we treated hypertension when it does the most good: as a primary-prevention strategy in midlife.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nutrition, Drugs, or Bariatric Surgery: What’s the Best Approach for Sustained Weight Loss?

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

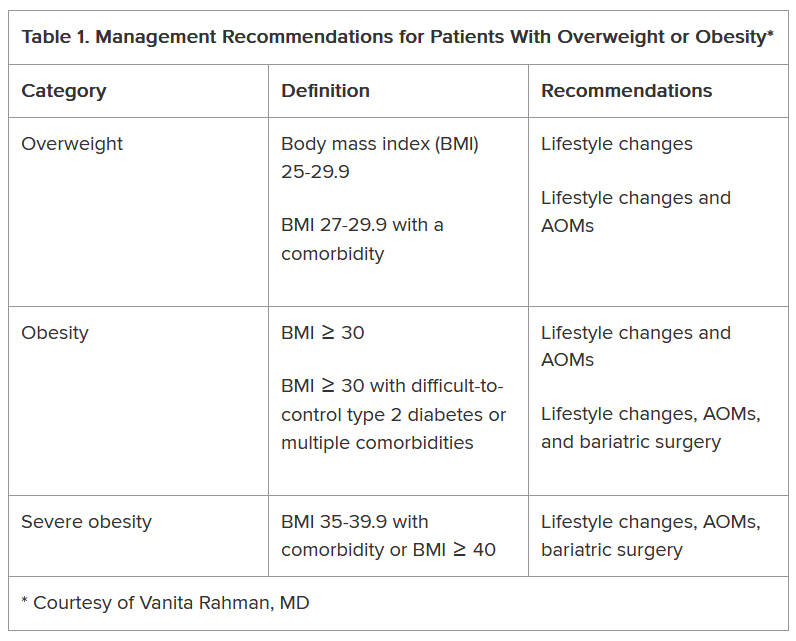

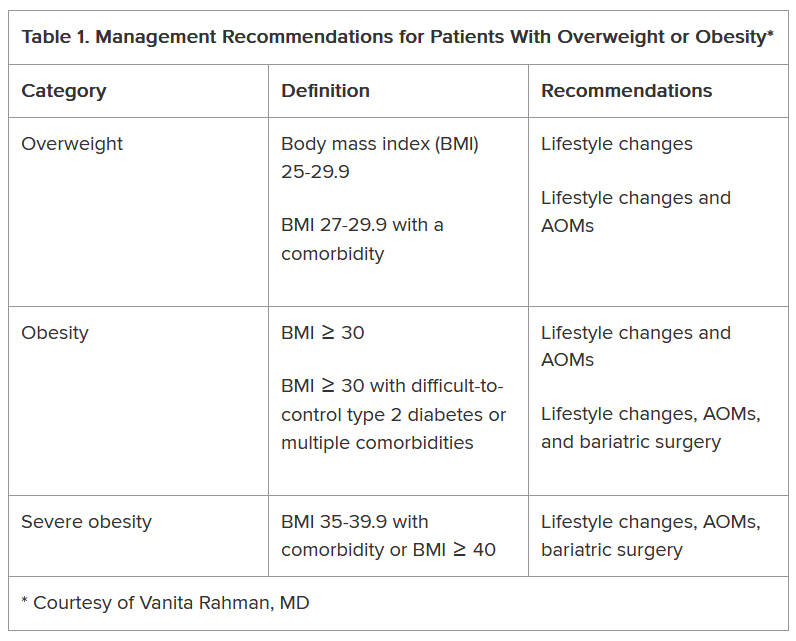

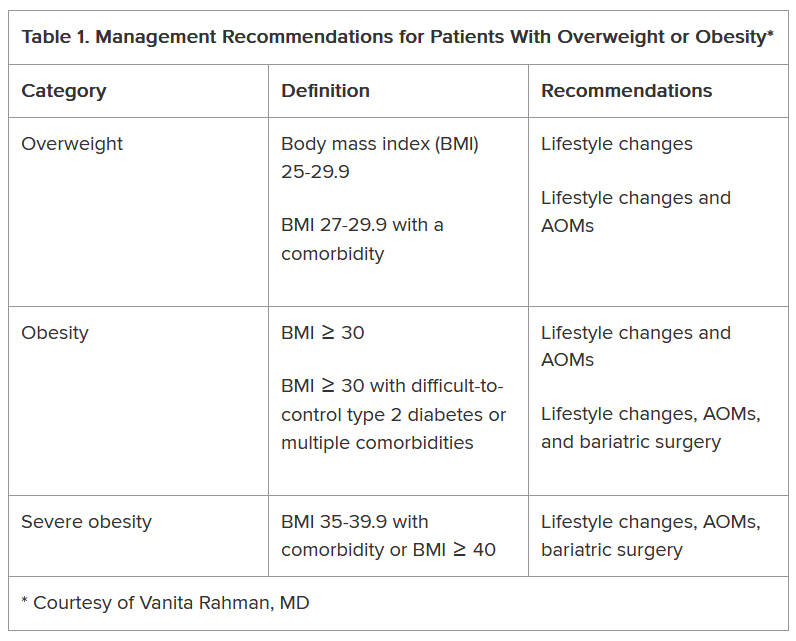

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

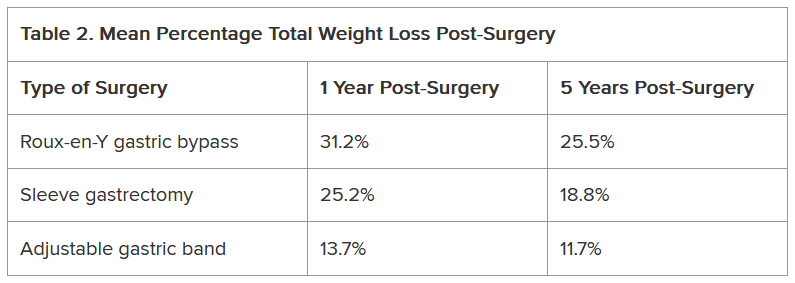

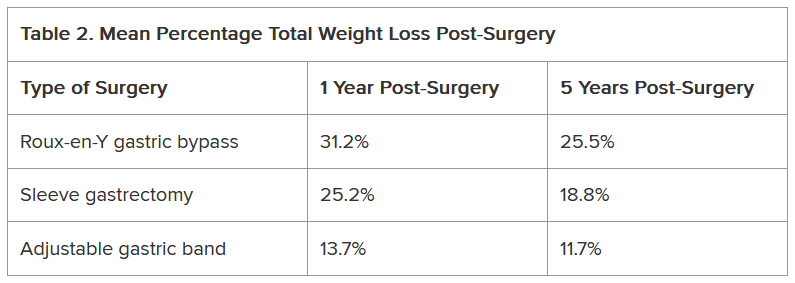

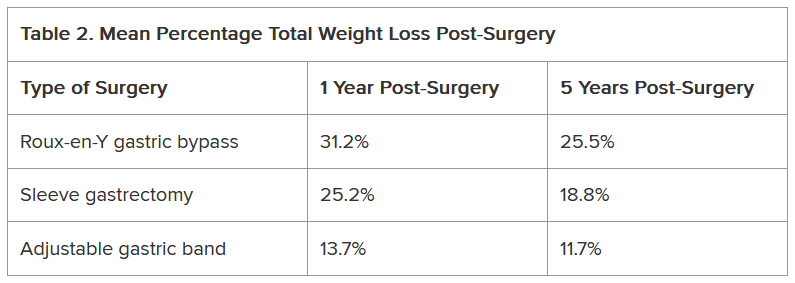

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AI-Enhanced ECG Used to Predict Hypertension and Associated Risks

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intensive BP Control May Benefit CKD Patients in Real World

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Dry January: Should Doctors Make It Year-Round?

For millennia in medicine, alcohol, particularly red wine, carried a health halo; in small doses, it has historically been thought to have cardioprotective benefits. Michael Farkouh, MD, a professor of cardiology at Cedars-Sinai, estimates half the physicians still accept people having a drink or two a day. “That is still in practice, though the numbers are reducing,” he said.

But Farkouh no longer drinks alcohol, a position he has come to after getting more involved in research into the substance and his realization that many of the studies touting alcohol’s health benefits were flawed.

Today, alcohol sits alongside asbestos and tobacco as class 1 carcinogens. According to the World Health Organization, it has no known safe ingestible amount. In 2018, a blockbuster report in The Lancet found no amount of any kind of alcohol improves health. In early January, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called for adding cancer warnings to alcohol labels.

But the way doctors drink is far from black and white. For physicians, drinking habits are tied up in personal values, professional understanding of a substance with a confusing research history, and the fact alcohol is deeply ingrained in the social fabric of society — and in medicine. As thinking on alcohol shifts, this news organization spoke with physicians about their own drinking habits, how they counsel patients on it, and alcohol’s place in a field that works to keep people healthy.

Cultural Currency

From the days of Hippocrates, who believed alcohol could cure virtually every ailment, alcohol has held a large role in medicine. Through much of the 19th century, patent remedies like Hamlin’s Wizard Oil and the Seven Sutherland Sisters Hair Grower, contained alcohol — sometimes in concentrations exceeding 50%.

The first American Pharmacopoeia, published in 1820, even contained nine wine-based medicines. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, physicians largely debated alcohol’s role in medicine. However, a 1922 poll of members of the American Medical Association found that physicians were still using alcohol as a medicine for everything from heart attacks to animal bites.

Today, alcohol’s presence in medicine is, in some ways, representative of a realized cognitive dissonance.

“In my mind, alcohol has completely lost any illusion of benefit. It is a poison to almost every single organ in our body. Yet I’m currently engaged in a duel of being a physician who drinks in moderation and constantly judging myself for it,” said Tyra Fainstad, MD, an internist and an associate professor at CU Medicine in Denver.

Fainstad said every academic national conference she has attended has had a reception with multiple cash bars — and professional recruitment dinners regularly include at least the offering of alcohol. Private hospitals often have open bars at events.

“Drinking has historically been a way that people unwind, even in medicine,” said addiction psychiatrist Alexis Ritvo, MD. Ritvo — who said she drinks occasionally but much less than she used to after paying attention to how alcohol makes her feel and the harm alcohol can cause — noted that some occasions where alcohol is present socially in medicine don’t bother her. Alcohol is even an option at the addiction psychiatry conference, where attendees can exchange tickets for drinks. But last year, the event provided separate bars for alcoholic and nonalcoholic drinks.

“Our life is full of things that are contradictory or at odds,” Ritvo said. “We want things to either be wrong or right, appropriate or inappropriate, but just like all things, everything’s pretty nuanced.”

But there are examples of alcohol being a part of an event that are downright inappropriate, such as when she attended a fundraiser for a recovery facility that had an open bar.

Farkouh said alcohol at events can exclude others. (He recommends that instead of calling a social gathering “going out for drinks,” someone might say, “We’re getting together.”) He drinks mocktails or nonalcoholic beer at work events where alcohol is served.

Brian Dwinnell, MD, associate dean of student life at CU Medicine, said alcohol can quickly become the focus of an event — something he noticed at an annual kickball game between first- and second-year students that has historically served beer.

In recent years, school leadership has removed alcohol from his institution’s match day celebration and the kickball game. “Initially, there was some pushback from students,” he said of making these events dry, “but now, it’s just sort of accepted, and the events have been just as great as they were when we did provide alcohol.”

How Doctors Drink