User login

CRP may predict survival after immunotherapy for lung cancer

CHICAGO – A baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) level above 50 mg/L independently predicted worse overall survival after immunotherapy in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer in a retrospective study.

In 99 patients treated with nivolumab after a first-line platinum doublet, the median baseline CRP level was 22 mg/L. After a median follow-up of 8.5 months, 50% of patients were alive, and, based on univariate and multivariate analysis, both liver involvement and having a CRP level greater than 50 mg/L were significantly associated with inferior overall survival after immunotherapy.

The median overall survival after immunotherapy was 9.3 months versus 2.7 months with a CRP level of 50 mg/L or less versus above 50 mg/L, Abdul Rafeh Naqash, MD, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Notably, significant increases in CRP level, compared with baseline, were seen at the time of grade 2 to grade 4 immune-related adverse events, which occurred in 38.4% of patients. This is a hypothesis-generating finding in that it suggests there is dysregulation of the immune system, in the context of immune checkpoint blockade, that leads to a more proinflammatory state, which ultimately leads to immune-related adverse events, Dr. Naqash said.

Study subjects were adults with a median age of 65 years who were treated during April 2015-March 2017. Most were white (64.7%), were male (64.6%), and had non–small cell lung cancer (88%). Most had stage IV disease (70.7%), and the most common site for metastases was the bones (35.4%) and the liver (24.2%). Patients’ CRP levels were measured at anti-PD-1–treatment initiation and serially with subsequent doses.

The findings are important because the identification of predictive biomarkers in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy could provide valuable insights into underlying mechanisms regulating patient responses, elucidate resistance mechanisms, and help with optimal selection of patients for treatment with and development of patient-tailored treatment, Dr. Naqash said, noting that identifying such biomarkers has thus far been a challenge.

However, this study is limited by its retrospective design and limited follow-up; the findings require validation in prospective lung cancer trials, he concluded.

Dr. Naqash reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – A baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) level above 50 mg/L independently predicted worse overall survival after immunotherapy in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer in a retrospective study.

In 99 patients treated with nivolumab after a first-line platinum doublet, the median baseline CRP level was 22 mg/L. After a median follow-up of 8.5 months, 50% of patients were alive, and, based on univariate and multivariate analysis, both liver involvement and having a CRP level greater than 50 mg/L were significantly associated with inferior overall survival after immunotherapy.

The median overall survival after immunotherapy was 9.3 months versus 2.7 months with a CRP level of 50 mg/L or less versus above 50 mg/L, Abdul Rafeh Naqash, MD, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Notably, significant increases in CRP level, compared with baseline, were seen at the time of grade 2 to grade 4 immune-related adverse events, which occurred in 38.4% of patients. This is a hypothesis-generating finding in that it suggests there is dysregulation of the immune system, in the context of immune checkpoint blockade, that leads to a more proinflammatory state, which ultimately leads to immune-related adverse events, Dr. Naqash said.

Study subjects were adults with a median age of 65 years who were treated during April 2015-March 2017. Most were white (64.7%), were male (64.6%), and had non–small cell lung cancer (88%). Most had stage IV disease (70.7%), and the most common site for metastases was the bones (35.4%) and the liver (24.2%). Patients’ CRP levels were measured at anti-PD-1–treatment initiation and serially with subsequent doses.

The findings are important because the identification of predictive biomarkers in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy could provide valuable insights into underlying mechanisms regulating patient responses, elucidate resistance mechanisms, and help with optimal selection of patients for treatment with and development of patient-tailored treatment, Dr. Naqash said, noting that identifying such biomarkers has thus far been a challenge.

However, this study is limited by its retrospective design and limited follow-up; the findings require validation in prospective lung cancer trials, he concluded.

Dr. Naqash reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – A baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) level above 50 mg/L independently predicted worse overall survival after immunotherapy in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer in a retrospective study.

In 99 patients treated with nivolumab after a first-line platinum doublet, the median baseline CRP level was 22 mg/L. After a median follow-up of 8.5 months, 50% of patients were alive, and, based on univariate and multivariate analysis, both liver involvement and having a CRP level greater than 50 mg/L were significantly associated with inferior overall survival after immunotherapy.

The median overall survival after immunotherapy was 9.3 months versus 2.7 months with a CRP level of 50 mg/L or less versus above 50 mg/L, Abdul Rafeh Naqash, MD, of East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Notably, significant increases in CRP level, compared with baseline, were seen at the time of grade 2 to grade 4 immune-related adverse events, which occurred in 38.4% of patients. This is a hypothesis-generating finding in that it suggests there is dysregulation of the immune system, in the context of immune checkpoint blockade, that leads to a more proinflammatory state, which ultimately leads to immune-related adverse events, Dr. Naqash said.

Study subjects were adults with a median age of 65 years who were treated during April 2015-March 2017. Most were white (64.7%), were male (64.6%), and had non–small cell lung cancer (88%). Most had stage IV disease (70.7%), and the most common site for metastases was the bones (35.4%) and the liver (24.2%). Patients’ CRP levels were measured at anti-PD-1–treatment initiation and serially with subsequent doses.

The findings are important because the identification of predictive biomarkers in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy could provide valuable insights into underlying mechanisms regulating patient responses, elucidate resistance mechanisms, and help with optimal selection of patients for treatment with and development of patient-tailored treatment, Dr. Naqash said, noting that identifying such biomarkers has thus far been a challenge.

However, this study is limited by its retrospective design and limited follow-up; the findings require validation in prospective lung cancer trials, he concluded.

Dr. Naqash reported having no disclosures.

AT A SYMPOSIUM IN THORACIC ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median overall survival after immunotherapy: 9.3 months vs. 2.7 months with CRP of 50 mg/L or less vs. above 50 mg/L.

Data source: A retrospective study of 99 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Naqash reported having no disclosures.

Postsurgical antibiotics cut infection in obese women after C-section

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41).

Data source: The randomized, placebo-controlled study comprised 403 women.

Disclosures: The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the study. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

PHM17 session summary: Career Development (K Award) grants

Session

Career Development (K Award) grants: What are they, why should I apply, and how do I get funded?

Presenters

Christopher Bonafide, MD, MSCE; Patrick Brady, MD, MS; Kavita Parikh, MD, MSHS; Raj Srivastava, MD, MPH, SFHM; Derek Williams, MD, MPH

Session Summary

Pediatric hospital medicine, in its relative infancy, is attracting a cohort of academicians dedicated to advancing the care of hospitalized children. While other pediatric subspecialties have long reserved a significant proportion of fellowship training for research, pediatric hospitalist research has instead developed from the work of scholarly pioneers in the industry.

More colloquially known as K Awards, NIH Career Development Awards exist to financially support early-career clinical, translational, and basic science investigators through a closely mentored career development and research plan. The result? A mutually beneficial initiative lasting 3-5 years aligning the interests of the early-career investigator, hosting institution, and NIH. The realm of grant funding is confusing and can be intimidating, particularly for early-career investigators in a rapidly growing field of practice. Presenters at this session addressed the stigma of applying for K awards head on.

Who should apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Competitive applicants for a Career Development Award are ideally interested in embarking on a career dedicated to research of some type, although exactly what that entails can and certainly may change over time.

What does the NIH Career Development Award provide?

The award funds a significant portion of your salary to provide protected time dedicated to your research and career development. Removing this financial barrier allows the investigator to become fully immersed in maturation as an independent investigator. The presenters were quick to caution that applicants (along with department and division chairs) should be aware that the award does not cover your entire salary; early-career investigators truly need dedication from their department and/or division to be successful.

Why apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Clinical, translational, and basic science research takes time to complete, and the skills needed to be a successful investigator are not intuitive. Rather, they require close mentorship and practice. A career development award organizes and prioritizes an early-career investigator’s approach to obtaining research independence. Applying for an NIH Career Development Award helps identify the applicant’s experiential and knowledge gaps and, more importantly, develops a plan for how these deficits will be addressed over the course of the research project. This formative process ideally allows the early-career investigator to be more competitive in seeking larger grant funding.

Interested in pursuing a career development award? Dr. Bonafide and Dr. Srivastava offered the valuable advice that an applicant’s proposed research is only part of the equation for funding success. Equally important is your ability to identify your weaknesses as they pertain to research (and how you will address these weaknesses) as well as to find your mentorship team. You and your fellow awardees should surround yourselves with mentors who will address specific needs, which, in some circumstances, may require creativity and collaboration to augment the experience gained from others.

Key takeaway for PHM

As we recognize the growing complexities of caring for the hospitalized child, opportunities for clinical, translational, and basic science are expanding rapidly. Embracing the benefits of formalizing your research training early can lead to a successful and satisfying academic career in the long term.

Dr. Morrison is a Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

Session

Career Development (K Award) grants: What are they, why should I apply, and how do I get funded?

Presenters

Christopher Bonafide, MD, MSCE; Patrick Brady, MD, MS; Kavita Parikh, MD, MSHS; Raj Srivastava, MD, MPH, SFHM; Derek Williams, MD, MPH

Session Summary

Pediatric hospital medicine, in its relative infancy, is attracting a cohort of academicians dedicated to advancing the care of hospitalized children. While other pediatric subspecialties have long reserved a significant proportion of fellowship training for research, pediatric hospitalist research has instead developed from the work of scholarly pioneers in the industry.

More colloquially known as K Awards, NIH Career Development Awards exist to financially support early-career clinical, translational, and basic science investigators through a closely mentored career development and research plan. The result? A mutually beneficial initiative lasting 3-5 years aligning the interests of the early-career investigator, hosting institution, and NIH. The realm of grant funding is confusing and can be intimidating, particularly for early-career investigators in a rapidly growing field of practice. Presenters at this session addressed the stigma of applying for K awards head on.

Who should apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Competitive applicants for a Career Development Award are ideally interested in embarking on a career dedicated to research of some type, although exactly what that entails can and certainly may change over time.

What does the NIH Career Development Award provide?

The award funds a significant portion of your salary to provide protected time dedicated to your research and career development. Removing this financial barrier allows the investigator to become fully immersed in maturation as an independent investigator. The presenters were quick to caution that applicants (along with department and division chairs) should be aware that the award does not cover your entire salary; early-career investigators truly need dedication from their department and/or division to be successful.

Why apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Clinical, translational, and basic science research takes time to complete, and the skills needed to be a successful investigator are not intuitive. Rather, they require close mentorship and practice. A career development award organizes and prioritizes an early-career investigator’s approach to obtaining research independence. Applying for an NIH Career Development Award helps identify the applicant’s experiential and knowledge gaps and, more importantly, develops a plan for how these deficits will be addressed over the course of the research project. This formative process ideally allows the early-career investigator to be more competitive in seeking larger grant funding.

Interested in pursuing a career development award? Dr. Bonafide and Dr. Srivastava offered the valuable advice that an applicant’s proposed research is only part of the equation for funding success. Equally important is your ability to identify your weaknesses as they pertain to research (and how you will address these weaknesses) as well as to find your mentorship team. You and your fellow awardees should surround yourselves with mentors who will address specific needs, which, in some circumstances, may require creativity and collaboration to augment the experience gained from others.

Key takeaway for PHM

As we recognize the growing complexities of caring for the hospitalized child, opportunities for clinical, translational, and basic science are expanding rapidly. Embracing the benefits of formalizing your research training early can lead to a successful and satisfying academic career in the long term.

Dr. Morrison is a Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

Session

Career Development (K Award) grants: What are they, why should I apply, and how do I get funded?

Presenters

Christopher Bonafide, MD, MSCE; Patrick Brady, MD, MS; Kavita Parikh, MD, MSHS; Raj Srivastava, MD, MPH, SFHM; Derek Williams, MD, MPH

Session Summary

Pediatric hospital medicine, in its relative infancy, is attracting a cohort of academicians dedicated to advancing the care of hospitalized children. While other pediatric subspecialties have long reserved a significant proportion of fellowship training for research, pediatric hospitalist research has instead developed from the work of scholarly pioneers in the industry.

More colloquially known as K Awards, NIH Career Development Awards exist to financially support early-career clinical, translational, and basic science investigators through a closely mentored career development and research plan. The result? A mutually beneficial initiative lasting 3-5 years aligning the interests of the early-career investigator, hosting institution, and NIH. The realm of grant funding is confusing and can be intimidating, particularly for early-career investigators in a rapidly growing field of practice. Presenters at this session addressed the stigma of applying for K awards head on.

Who should apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Competitive applicants for a Career Development Award are ideally interested in embarking on a career dedicated to research of some type, although exactly what that entails can and certainly may change over time.

What does the NIH Career Development Award provide?

The award funds a significant portion of your salary to provide protected time dedicated to your research and career development. Removing this financial barrier allows the investigator to become fully immersed in maturation as an independent investigator. The presenters were quick to caution that applicants (along with department and division chairs) should be aware that the award does not cover your entire salary; early-career investigators truly need dedication from their department and/or division to be successful.

Why apply for an NIH Career Development Award?

Clinical, translational, and basic science research takes time to complete, and the skills needed to be a successful investigator are not intuitive. Rather, they require close mentorship and practice. A career development award organizes and prioritizes an early-career investigator’s approach to obtaining research independence. Applying for an NIH Career Development Award helps identify the applicant’s experiential and knowledge gaps and, more importantly, develops a plan for how these deficits will be addressed over the course of the research project. This formative process ideally allows the early-career investigator to be more competitive in seeking larger grant funding.

Interested in pursuing a career development award? Dr. Bonafide and Dr. Srivastava offered the valuable advice that an applicant’s proposed research is only part of the equation for funding success. Equally important is your ability to identify your weaknesses as they pertain to research (and how you will address these weaknesses) as well as to find your mentorship team. You and your fellow awardees should surround yourselves with mentors who will address specific needs, which, in some circumstances, may require creativity and collaboration to augment the experience gained from others.

Key takeaway for PHM

As we recognize the growing complexities of caring for the hospitalized child, opportunities for clinical, translational, and basic science are expanding rapidly. Embracing the benefits of formalizing your research training early can lead to a successful and satisfying academic career in the long term.

Dr. Morrison is a Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla.

FDA grants accelerated approval to copanlisib for relapsed follicular lymphoma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa) for the treatment of adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior treatments.

Approval of the kinase inhibitor was based on an overall response rate of 59% in a single-arm trial of 104 patients with follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had relapsed disease following at least two prior treatments. These patients had a complete or partial response for a median 12.2 months.

“For patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma, the cancer often comes back even after multiple treatments,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the press release. “Options are limited for these patients and today’s approval provides an additional choice for treatment, filling an unmet need for them,” he said.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa) for the treatment of adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior treatments.

Approval of the kinase inhibitor was based on an overall response rate of 59% in a single-arm trial of 104 patients with follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had relapsed disease following at least two prior treatments. These patients had a complete or partial response for a median 12.2 months.

“For patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma, the cancer often comes back even after multiple treatments,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the press release. “Options are limited for these patients and today’s approval provides an additional choice for treatment, filling an unmet need for them,” he said.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa) for the treatment of adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior treatments.

Approval of the kinase inhibitor was based on an overall response rate of 59% in a single-arm trial of 104 patients with follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had relapsed disease following at least two prior treatments. These patients had a complete or partial response for a median 12.2 months.

“For patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma, the cancer often comes back even after multiple treatments,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the press release. “Options are limited for these patients and today’s approval provides an additional choice for treatment, filling an unmet need for them,” he said.

Rheumatoid arthritis characteristics make large contribution to cardiovascular risk

Nearly one-third of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis can be attributed to their rheumatoid arthritis characteristics, such as Disease Activity Score and rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated protein antibody positivity, research suggests.

A prospective, international cohort study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases followed 5,638 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and no history of cardiovascular disease for a mean of 5.8 years to look at their risk of myocardial infarction, angina, revascularization, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from cardiovascular disease.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events was 20.9% in men and 11.1% in women.

Smoking and hypertension were the strongest predictors of cardiovascular disease in both men and women and had the highest population attributable risk (PAR), even after adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors.

The PAR for triglycerides was 11.5% overall, but it was 12.6% for Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) and 12.2% for rheumatoid factor (RF)/anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) positivity. Other RA-related factors, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein, did not have a significant effect on cardiovascular event risk.

When combined, cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking, body mass index, diabetes, and family history accounted for 49% of the PAR of cardiovascular events in people with RA, and the RA characteristics explained 30.3% of the risk.

Together, the cardiovascular and RA risk factors accounted for 69.6% of the risk of cardiovascular events, and the remaining 30.4% could not be explained.

While the PAR associated with the combined cardiovascular risk factors was higher in men than in women, the contribution of all the RA characteristics combined proved to be greater in women than in men. However, neither sex difference was statistically significant.

“While the prevalence of RF/ACPA positivity and DAS28 levels was similar between the sexes, the effect sizes of RA characteristics appeared to be larger among women than men, despite lack of statistical significance,” the authors wrote.

“Moreover, higher levels of ESR in women than men may partially explain this apparent difference in PAR [and] RA disease duration was longer among women, and more women than men were receiving biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] at baseline.”

Eli Lilly, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Norwegian South East Health Authority supported the study. Two authors declared honoraria, fees, and grants from the pharmaceutical industry, including Eli Lilly. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis can be attributed to their rheumatoid arthritis characteristics, such as Disease Activity Score and rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated protein antibody positivity, research suggests.

A prospective, international cohort study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases followed 5,638 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and no history of cardiovascular disease for a mean of 5.8 years to look at their risk of myocardial infarction, angina, revascularization, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from cardiovascular disease.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events was 20.9% in men and 11.1% in women.

Smoking and hypertension were the strongest predictors of cardiovascular disease in both men and women and had the highest population attributable risk (PAR), even after adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors.

The PAR for triglycerides was 11.5% overall, but it was 12.6% for Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) and 12.2% for rheumatoid factor (RF)/anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) positivity. Other RA-related factors, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein, did not have a significant effect on cardiovascular event risk.

When combined, cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking, body mass index, diabetes, and family history accounted for 49% of the PAR of cardiovascular events in people with RA, and the RA characteristics explained 30.3% of the risk.

Together, the cardiovascular and RA risk factors accounted for 69.6% of the risk of cardiovascular events, and the remaining 30.4% could not be explained.

While the PAR associated with the combined cardiovascular risk factors was higher in men than in women, the contribution of all the RA characteristics combined proved to be greater in women than in men. However, neither sex difference was statistically significant.

“While the prevalence of RF/ACPA positivity and DAS28 levels was similar between the sexes, the effect sizes of RA characteristics appeared to be larger among women than men, despite lack of statistical significance,” the authors wrote.

“Moreover, higher levels of ESR in women than men may partially explain this apparent difference in PAR [and] RA disease duration was longer among women, and more women than men were receiving biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] at baseline.”

Eli Lilly, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Norwegian South East Health Authority supported the study. Two authors declared honoraria, fees, and grants from the pharmaceutical industry, including Eli Lilly. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis can be attributed to their rheumatoid arthritis characteristics, such as Disease Activity Score and rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated protein antibody positivity, research suggests.

A prospective, international cohort study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases followed 5,638 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and no history of cardiovascular disease for a mean of 5.8 years to look at their risk of myocardial infarction, angina, revascularization, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from cardiovascular disease.

Overall, the 10-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events was 20.9% in men and 11.1% in women.

Smoking and hypertension were the strongest predictors of cardiovascular disease in both men and women and had the highest population attributable risk (PAR), even after adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors.

The PAR for triglycerides was 11.5% overall, but it was 12.6% for Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) and 12.2% for rheumatoid factor (RF)/anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) positivity. Other RA-related factors, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein, did not have a significant effect on cardiovascular event risk.

When combined, cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking, body mass index, diabetes, and family history accounted for 49% of the PAR of cardiovascular events in people with RA, and the RA characteristics explained 30.3% of the risk.

Together, the cardiovascular and RA risk factors accounted for 69.6% of the risk of cardiovascular events, and the remaining 30.4% could not be explained.

While the PAR associated with the combined cardiovascular risk factors was higher in men than in women, the contribution of all the RA characteristics combined proved to be greater in women than in men. However, neither sex difference was statistically significant.

“While the prevalence of RF/ACPA positivity and DAS28 levels was similar between the sexes, the effect sizes of RA characteristics appeared to be larger among women than men, despite lack of statistical significance,” the authors wrote.

“Moreover, higher levels of ESR in women than men may partially explain this apparent difference in PAR [and] RA disease duration was longer among women, and more women than men were receiving biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] at baseline.”

Eli Lilly, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Norwegian South East Health Authority supported the study. Two authors declared honoraria, fees, and grants from the pharmaceutical industry, including Eli Lilly. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Rheumatoid arthritis characteristics explained 30.3% of the risk of cardiovascular events in individuals with RA.

Data source: A prospective, international cohort study of 5,638 patients with RA.

Disclosures: Eli Lilly, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Norwegian South East Health Authority supported the study. Two authors declared honoraria, fees, and grants from the pharmaceutical industry, including Eli Lilly. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Ultrasound’s value for arthralgia may be to rule out IA

Ultrasound evaluations to look for subclinical inflammation in joints of patients with arthralgia appear best at ruling out inflammatory arthritis (IA) 1 year in the future rather than ruling it in, according to findings from a multicenter cohort study published online in Arthritis Research and Therapy.

The imaging modality’s ability to identify those who will not go on to develop IA complemented the serologic and clinical factors that help to discriminate the individuals with arthralgia who are most at risk of the condition.

The ultimate goal of using imaging such as ultrasound in patients with arthralgia is to identify those who would benefit from starting treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as early as possible to potentially improve outcomes, but it also could help to discriminate between the anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive and seronegative individuals without clinical signs of inflammation at baseline who may progress from arthralgia to IA.

“Although ACPA positivity is a very good predictor for those patients who will develop IA within 1 year, it is still difficult to identify the exact individuals who will develop IA, because any ACPA-positive individual has an a priori chance of 50% of developing IA. In seronegative patients, the prediction of IA is even more difficult, because only 5% develop IA within the subsequent year. Imaging techniques have been shown to be able to detect synovitis before its clinical appearance and could be of help in identifying those at risk of IA,” the investigators wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:202. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1405-y).

Dr. van der Ven and her associates found that 31 (16%) of 196 patients who had arthralgia for less than 1 year in the hands, feet, or shoulders went on to develop IA after 1 year of follow-up. In this group of 196 patients at baseline, 72 (37%) had synovitis on ultrasound – defined as a greyscale grade of 2 or 3 and/or the presence of power Doppler signal (grade 1, 2, or 3) – including 32 with a positive power Doppler. A total of 18 patients were lost to follow-up during the first 6 months and another 19 were lost during months 6-12.

Rheumatologists who were unaware of ultrasound findings had to confirm soft-tissue swelling as arthritis at 1 year to classify it as incident IA. The positive predictive value of ultrasound for IA was only 26% when at least 1 joint out of 26 assessed was positive, but the negative predictive value when no joints were positive on ultrasound was 89%.

Overall, at 1 year, 15 of the 31 patients with IA had started therapy with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and 22 did not have a definite diagnosis; 12 had monoarthritis and 10 had polyarthritis. The remaining nine patients included four with rheumatoid arthritis, four with psoriatic arthritis, and one with spondyloarthritis.

At baseline, individuals with IA were more often older (mean age 50 vs. 44 years; P = .005), had synovitis on ultrasound (59% vs. 32%; P = .007), and had a positive power Doppler signal (31% vs. 12%; P = .012). A multivariate analysis revealed that IA at 1 year of follow-up could be independently predicted according to age (odds ratio, 1.06), morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes (OR, 2.80), ACPA positivity (OR, 2.35), and synovitis on ultrasound (OR, 2.65).

The investigators noted that the study’s limitations relate to requirements for patients to have at least two painful joints in hands, feet, or shoulders at baseline and two criteria related to inflammation. The possible inflammation-related criteria required for entry included morning stiffness for more than 1 hour, inability to clench a fist in the morning, pain when shaking someone’s hand, pins and needles in the fingers, difficulties wearing rings or shoes, family history of rheumatoid arthritis, and/or unexplained fatigue for less than 1 year.

Rheumatologists who enrolled patients into the cohort also may have “recruited clinically suspected patients with possibly more severe symptoms,” the investigators noted. Another potential source of bias related to the group of 38 patients who chose not to participate: It’s possible these patients had less severe symptoms than those who participated in the study.

The study was funded by an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer. The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Ultrasound evaluations to look for subclinical inflammation in joints of patients with arthralgia appear best at ruling out inflammatory arthritis (IA) 1 year in the future rather than ruling it in, according to findings from a multicenter cohort study published online in Arthritis Research and Therapy.

The imaging modality’s ability to identify those who will not go on to develop IA complemented the serologic and clinical factors that help to discriminate the individuals with arthralgia who are most at risk of the condition.

The ultimate goal of using imaging such as ultrasound in patients with arthralgia is to identify those who would benefit from starting treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as early as possible to potentially improve outcomes, but it also could help to discriminate between the anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive and seronegative individuals without clinical signs of inflammation at baseline who may progress from arthralgia to IA.

“Although ACPA positivity is a very good predictor for those patients who will develop IA within 1 year, it is still difficult to identify the exact individuals who will develop IA, because any ACPA-positive individual has an a priori chance of 50% of developing IA. In seronegative patients, the prediction of IA is even more difficult, because only 5% develop IA within the subsequent year. Imaging techniques have been shown to be able to detect synovitis before its clinical appearance and could be of help in identifying those at risk of IA,” the investigators wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:202. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1405-y).

Dr. van der Ven and her associates found that 31 (16%) of 196 patients who had arthralgia for less than 1 year in the hands, feet, or shoulders went on to develop IA after 1 year of follow-up. In this group of 196 patients at baseline, 72 (37%) had synovitis on ultrasound – defined as a greyscale grade of 2 or 3 and/or the presence of power Doppler signal (grade 1, 2, or 3) – including 32 with a positive power Doppler. A total of 18 patients were lost to follow-up during the first 6 months and another 19 were lost during months 6-12.

Rheumatologists who were unaware of ultrasound findings had to confirm soft-tissue swelling as arthritis at 1 year to classify it as incident IA. The positive predictive value of ultrasound for IA was only 26% when at least 1 joint out of 26 assessed was positive, but the negative predictive value when no joints were positive on ultrasound was 89%.

Overall, at 1 year, 15 of the 31 patients with IA had started therapy with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and 22 did not have a definite diagnosis; 12 had monoarthritis and 10 had polyarthritis. The remaining nine patients included four with rheumatoid arthritis, four with psoriatic arthritis, and one with spondyloarthritis.

At baseline, individuals with IA were more often older (mean age 50 vs. 44 years; P = .005), had synovitis on ultrasound (59% vs. 32%; P = .007), and had a positive power Doppler signal (31% vs. 12%; P = .012). A multivariate analysis revealed that IA at 1 year of follow-up could be independently predicted according to age (odds ratio, 1.06), morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes (OR, 2.80), ACPA positivity (OR, 2.35), and synovitis on ultrasound (OR, 2.65).

The investigators noted that the study’s limitations relate to requirements for patients to have at least two painful joints in hands, feet, or shoulders at baseline and two criteria related to inflammation. The possible inflammation-related criteria required for entry included morning stiffness for more than 1 hour, inability to clench a fist in the morning, pain when shaking someone’s hand, pins and needles in the fingers, difficulties wearing rings or shoes, family history of rheumatoid arthritis, and/or unexplained fatigue for less than 1 year.

Rheumatologists who enrolled patients into the cohort also may have “recruited clinically suspected patients with possibly more severe symptoms,” the investigators noted. Another potential source of bias related to the group of 38 patients who chose not to participate: It’s possible these patients had less severe symptoms than those who participated in the study.

The study was funded by an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer. The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Ultrasound evaluations to look for subclinical inflammation in joints of patients with arthralgia appear best at ruling out inflammatory arthritis (IA) 1 year in the future rather than ruling it in, according to findings from a multicenter cohort study published online in Arthritis Research and Therapy.

The imaging modality’s ability to identify those who will not go on to develop IA complemented the serologic and clinical factors that help to discriminate the individuals with arthralgia who are most at risk of the condition.

The ultimate goal of using imaging such as ultrasound in patients with arthralgia is to identify those who would benefit from starting treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as early as possible to potentially improve outcomes, but it also could help to discriminate between the anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive and seronegative individuals without clinical signs of inflammation at baseline who may progress from arthralgia to IA.

“Although ACPA positivity is a very good predictor for those patients who will develop IA within 1 year, it is still difficult to identify the exact individuals who will develop IA, because any ACPA-positive individual has an a priori chance of 50% of developing IA. In seronegative patients, the prediction of IA is even more difficult, because only 5% develop IA within the subsequent year. Imaging techniques have been shown to be able to detect synovitis before its clinical appearance and could be of help in identifying those at risk of IA,” the investigators wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:202. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1405-y).

Dr. van der Ven and her associates found that 31 (16%) of 196 patients who had arthralgia for less than 1 year in the hands, feet, or shoulders went on to develop IA after 1 year of follow-up. In this group of 196 patients at baseline, 72 (37%) had synovitis on ultrasound – defined as a greyscale grade of 2 or 3 and/or the presence of power Doppler signal (grade 1, 2, or 3) – including 32 with a positive power Doppler. A total of 18 patients were lost to follow-up during the first 6 months and another 19 were lost during months 6-12.

Rheumatologists who were unaware of ultrasound findings had to confirm soft-tissue swelling as arthritis at 1 year to classify it as incident IA. The positive predictive value of ultrasound for IA was only 26% when at least 1 joint out of 26 assessed was positive, but the negative predictive value when no joints were positive on ultrasound was 89%.

Overall, at 1 year, 15 of the 31 patients with IA had started therapy with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and 22 did not have a definite diagnosis; 12 had monoarthritis and 10 had polyarthritis. The remaining nine patients included four with rheumatoid arthritis, four with psoriatic arthritis, and one with spondyloarthritis.

At baseline, individuals with IA were more often older (mean age 50 vs. 44 years; P = .005), had synovitis on ultrasound (59% vs. 32%; P = .007), and had a positive power Doppler signal (31% vs. 12%; P = .012). A multivariate analysis revealed that IA at 1 year of follow-up could be independently predicted according to age (odds ratio, 1.06), morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes (OR, 2.80), ACPA positivity (OR, 2.35), and synovitis on ultrasound (OR, 2.65).

The investigators noted that the study’s limitations relate to requirements for patients to have at least two painful joints in hands, feet, or shoulders at baseline and two criteria related to inflammation. The possible inflammation-related criteria required for entry included morning stiffness for more than 1 hour, inability to clench a fist in the morning, pain when shaking someone’s hand, pins and needles in the fingers, difficulties wearing rings or shoes, family history of rheumatoid arthritis, and/or unexplained fatigue for less than 1 year.

Rheumatologists who enrolled patients into the cohort also may have “recruited clinically suspected patients with possibly more severe symptoms,” the investigators noted. Another potential source of bias related to the group of 38 patients who chose not to participate: It’s possible these patients had less severe symptoms than those who participated in the study.

The study was funded by an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer. The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

FROM ARTHRITIS RESEARCH AND THERAPY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The positive predictive value of ultrasound for IA was only 26% when at least 1 joint out of 26 assessed was positive, but the negative predictive value when no joints were positive on ultrasound was 89%.

Data source: A multicenter cohort study of 196 patients with arthralgia in at least two joints for less than 1 year.

Disclosures: The study was funded by an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer. The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Medial Oblique Meniscomeniscal Ligament of Knee

Take-Home Points

- Prevalence of the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament is 1% to 4%.

- It is important to distinguish this ligament from a meniscus tear on MRI.

- The functional characteristics of this ligament are not well understood.

- What may appear to be a meniscal tear in a younger patient could be a medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament.

- Dr. Flanigan recommends leaving the ligament intact unless resection is needed to provide better visualization.

We report a case of aberrant meniscus attachment in the setting of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. An anomalous cordlike attachment ran from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus through the intercondylar notch. This attachment was previously named the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament1 but has seldom been reported in the literature. Prevalence is 1% to 4%.1,2 This case was treated at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old man presented with left knee pain after sustaining 2 injuries to the knee. The first injury occurred during a dodgeball game—when the knee buckled on landing from a jump. A “pop” was felt, and the knee swelled immediately. The second injury occurred about 3 months later, during soccer play. The patient was running when his foot slipped and caused the knee to buckle. Again, a “pop” was felt, and there was swelling. Mechanical symptoms of clicking then started. The patient reported no instability episodes. His medical history and family history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was healthy and had a body mass index of 23.05 kg/m2.

Physical examination revealed no effusion, erythema, or warmth in the left knee. Range of motion was 0° to 135° in the left knee and 0° to 140° in the right knee. There was no pain on hyperextension of the knee or medial or lateral joint-line tenderness, but there was pain on hyperflexion, and the McMurray test was positive. Ligament examination was negative except for positive anterior drawer, Lachman, and pivot-shift tests.

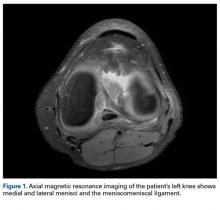

Radiographs taken the day of the first clinic visit showed no acute osseous abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed complete disruption of the proximal fibers of the ACL (Figures 1, 2).

Also observed was a small oblique tear of the body of the lateral meniscus with slight blunting of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus, which may have been related to a small tear. A pivot-shift contusion pattern with impaction fracture of the lateral femoral condyle was also appreciated. There were no definite cartilage defects identified.

Discussion

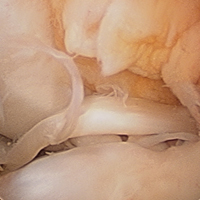

The medial and lateral menisci typically are separate fibrocartilaginous structures acting as a cushion for the knee, but normal variant connections between the structures have been described. These connections include the anterior transverse meniscal ligament, the posterior transverse meniscal ligament, and the medial and lateral oblique meniscomeniscal ligaments.3 In the present case, a medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament was identified. Its path between menisci was traceable on coronal and axial views. Video taken during arthroscopy also clearly showed its path and its relationship to other structures in the knee. To Dr. Flanigan’s knowledge, this ligament was not previously described with video. It is important to distinguish this ligament from a horizontal tear of the meniscus, given the potential for misinterpretation on MRI. A horizontal tear is a degenerative change that often occurs in older patients. Our patient was 18 years old at time of injury. In addition, the surface of his lower meniscus was smooth, whereas in a tear the edge is irregular and discontinuous. Dr. Flanigan prefers to leave this ligament intact unless resection would provide better visualization during arthroscopy. His reasoning is that the functional characteristics of the ligament are not well understood.

There are few reports on the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament.1 Sanders and colleagues1 found 3 cases of this normal variant. In the first, the ligament was interpreted as a flap tear on MRI; in the other 2 cases, the ligament was correctly identified. Kim and Laor2 and Dervin and Paterson4 also described this variant in case reports.

There are many abnormalities of the meniscus. In our literature review, we found reports on various anomalies, including discoid meniscus,5 ring-shape meniscus,6,7 accessory meniscus,8 double-layer meniscus,9-12 abnormal band formation,13,14 hypoplasia,15 Wrisberg meniscus,6 and congenital absence of meniscus.16 These variations have multifactorial causes, including congenital and developmental influences.

In a recent case report, Giordano and Goldblatt14 described an abnormal band of lateral meniscus extending from the posterior horn to the anterior-mid portion of the same meniscus. Lee and Min13 described the same band earlier, in a 2-patient case report.13 One patient presented symptomatically, nontraumatically, and the other with a posterior cruciate ligament tear. Each case was deemed congenital given the characteristic appearance and bilaterality of the anomaly.

In an 11-patient case series in Finland, Rainio and colleagues17 described an attachment from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus inserting into the ACL—a crescent band from the upper surface of the anterior horn that attached along the upper two thirds of the ACL.

At 2-year follow-up, our patient was doing well with rehabilitation and experienced only minimal symptoms. Radiologists and surgeons should be able to identify such variants. Knowing the common and rare variants, radiologists can help surgeons by identifying normal anatomy from pathology and providing a more clinically relevant report. Surgeons should be aware of the anatomical variability in the knee in order to provide the best care for their patients.

1. Sanders TG, Linares RC, Lawhorn KW, Tirman PF, Houser C. Oblique meniscomeniscal ligament: another potential pitfall for a meniscal tear—anatomic description and appearance at MR imaging in three cases. Radiology. 1999;213(1):213-216.

2. Kim HK, Laor T. Oblique meniscomeniscal ligament: a normal variant. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(6):634.

3. Chan CM, Goldblatt JP. Unilateral meniscomeniscal ligament. Orthopedics. 2012;35(12):e1815-e1817.

4. Dervin GF, Paterson RS. Oblique menisco-meniscal ligament of the knee. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):363-365.

5. Sun Y, Jiang Q. Review of discoid meniscus. Orthop Surg. 2011;3(4):219-223.

6. Kim YG, Ihn JC, Park SK, Kyung HS. An arthroscopic analysis of lateral meniscal variants and a comparison with MRI findings. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(1):20-26.

7. Kim SJ, Jeon CH, Koh CH. A ring-shaped lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):738-739.

8. Karahan M, Erol B. Accessory lateral meniscus: a case report. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1973-1976.

9. Okahashi K, Sugimoto K, Iwai M, Oshima M, Fujisawa Y, Takakura Y. Double-layered lateral meniscus. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10(6):661-664.

10. Karataglis D, Dramis A, Learmonth DJ. Double-layered lateral meniscus. A rare anatomical aberration. Knee. 2006;13(5):415-416.

11. Takayama K, Kuroda R, Matsumoto T, et al. Bilateral double-layered lateral meniscus: a report of two cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(11):1336-1339.

12. Wang Q, Liu XM, Liu SB, Bai Y. Double-layered lateral meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2050-2051.

13. Lee BI, Min KD. Abnormal band of the lateral meniscus of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(6):11.

14. Giordano B, Goldblatt J. Abnormal band of lateral meniscus. Orthopedics. 2009;32(1):51.

15. Ohana N, Plotquin D, Atar D. Bilateral hypoplastic lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):740-742.

16. Tolo VT. Congenital absence of the menisci and cruciate ligaments of the knee. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(6):1022-1024.

17. Rainio P, Sarimo J, Rantanen J, Alanen J, Orava S. Observation of anomalous insertion of the medial meniscus on the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(2):E9.

Take-Home Points

- Prevalence of the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament is 1% to 4%.

- It is important to distinguish this ligament from a meniscus tear on MRI.

- The functional characteristics of this ligament are not well understood.

- What may appear to be a meniscal tear in a younger patient could be a medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament.

- Dr. Flanigan recommends leaving the ligament intact unless resection is needed to provide better visualization.

We report a case of aberrant meniscus attachment in the setting of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. An anomalous cordlike attachment ran from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus through the intercondylar notch. This attachment was previously named the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament1 but has seldom been reported in the literature. Prevalence is 1% to 4%.1,2 This case was treated at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old man presented with left knee pain after sustaining 2 injuries to the knee. The first injury occurred during a dodgeball game—when the knee buckled on landing from a jump. A “pop” was felt, and the knee swelled immediately. The second injury occurred about 3 months later, during soccer play. The patient was running when his foot slipped and caused the knee to buckle. Again, a “pop” was felt, and there was swelling. Mechanical symptoms of clicking then started. The patient reported no instability episodes. His medical history and family history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was healthy and had a body mass index of 23.05 kg/m2.

Physical examination revealed no effusion, erythema, or warmth in the left knee. Range of motion was 0° to 135° in the left knee and 0° to 140° in the right knee. There was no pain on hyperextension of the knee or medial or lateral joint-line tenderness, but there was pain on hyperflexion, and the McMurray test was positive. Ligament examination was negative except for positive anterior drawer, Lachman, and pivot-shift tests.

Radiographs taken the day of the first clinic visit showed no acute osseous abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed complete disruption of the proximal fibers of the ACL (Figures 1, 2).

Also observed was a small oblique tear of the body of the lateral meniscus with slight blunting of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus, which may have been related to a small tear. A pivot-shift contusion pattern with impaction fracture of the lateral femoral condyle was also appreciated. There were no definite cartilage defects identified.

Discussion

The medial and lateral menisci typically are separate fibrocartilaginous structures acting as a cushion for the knee, but normal variant connections between the structures have been described. These connections include the anterior transverse meniscal ligament, the posterior transverse meniscal ligament, and the medial and lateral oblique meniscomeniscal ligaments.3 In the present case, a medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament was identified. Its path between menisci was traceable on coronal and axial views. Video taken during arthroscopy also clearly showed its path and its relationship to other structures in the knee. To Dr. Flanigan’s knowledge, this ligament was not previously described with video. It is important to distinguish this ligament from a horizontal tear of the meniscus, given the potential for misinterpretation on MRI. A horizontal tear is a degenerative change that often occurs in older patients. Our patient was 18 years old at time of injury. In addition, the surface of his lower meniscus was smooth, whereas in a tear the edge is irregular and discontinuous. Dr. Flanigan prefers to leave this ligament intact unless resection would provide better visualization during arthroscopy. His reasoning is that the functional characteristics of the ligament are not well understood.

There are few reports on the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament.1 Sanders and colleagues1 found 3 cases of this normal variant. In the first, the ligament was interpreted as a flap tear on MRI; in the other 2 cases, the ligament was correctly identified. Kim and Laor2 and Dervin and Paterson4 also described this variant in case reports.

There are many abnormalities of the meniscus. In our literature review, we found reports on various anomalies, including discoid meniscus,5 ring-shape meniscus,6,7 accessory meniscus,8 double-layer meniscus,9-12 abnormal band formation,13,14 hypoplasia,15 Wrisberg meniscus,6 and congenital absence of meniscus.16 These variations have multifactorial causes, including congenital and developmental influences.

In a recent case report, Giordano and Goldblatt14 described an abnormal band of lateral meniscus extending from the posterior horn to the anterior-mid portion of the same meniscus. Lee and Min13 described the same band earlier, in a 2-patient case report.13 One patient presented symptomatically, nontraumatically, and the other with a posterior cruciate ligament tear. Each case was deemed congenital given the characteristic appearance and bilaterality of the anomaly.

In an 11-patient case series in Finland, Rainio and colleagues17 described an attachment from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus inserting into the ACL—a crescent band from the upper surface of the anterior horn that attached along the upper two thirds of the ACL.

At 2-year follow-up, our patient was doing well with rehabilitation and experienced only minimal symptoms. Radiologists and surgeons should be able to identify such variants. Knowing the common and rare variants, radiologists can help surgeons by identifying normal anatomy from pathology and providing a more clinically relevant report. Surgeons should be aware of the anatomical variability in the knee in order to provide the best care for their patients.

Take-Home Points

- Prevalence of the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament is 1% to 4%.

- It is important to distinguish this ligament from a meniscus tear on MRI.

- The functional characteristics of this ligament are not well understood.

- What may appear to be a meniscal tear in a younger patient could be a medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament.

- Dr. Flanigan recommends leaving the ligament intact unless resection is needed to provide better visualization.

We report a case of aberrant meniscus attachment in the setting of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. An anomalous cordlike attachment ran from the anterior horn of the medial meniscus to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus through the intercondylar notch. This attachment was previously named the medial oblique meniscomeniscal ligament1 but has seldom been reported in the literature. Prevalence is 1% to 4%.1,2 This case was treated at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old man presented with left knee pain after sustaining 2 injuries to the knee. The first injury occurred during a dodgeball game—when the knee buckled on landing from a jump. A “pop” was felt, and the knee swelled immediately. The second injury occurred about 3 months later, during soccer play. The patient was running when his foot slipped and caused the knee to buckle. Again, a “pop” was felt, and there was swelling. Mechanical symptoms of clicking then started. The patient reported no instability episodes. His medical history and family history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was healthy and had a body mass index of 23.05 kg/m2.