User login

How to give a talk

I have to give a talk. Get this – the topic is how to give a good talk. Very meta.

I’ve given a hundred or so presentations in my career, including a couple of TEDx talks. With each one, I try to get a little better. Effective speaking is always simple but never easy. Let me share with you a few things I’ve learned.

Even if you don’t want to become a TEDMED phenom, you should know a few fundamentals. Giving good talks enhances your reputation and can jump-start your practice or career. For any talk, you must master three things: preparation, content, and delivery.

Just as we choose movies with actors we like, people choose speakers they want to see. Who you are matters. If you are introduced by an emcee, then be sure he or she bills you as a star. However, don’t try to be someone you aren’t – If I gave a talk on robotic prostate surgery, I’d be sure to lose no matter how witty I was. That’s why writing your own intro can sometimes be your best option.

Next up: content. It’s the king of speaking as well as marketing. Although you can pick up points for style, if you want to be remembered, you have to deliver something worth remembering. This starts with your preparation. Resist the temptation to focus exclusively on your slides. As in writing, it is best to brainstorm what you want to cover, then outline your ideas, then fill in content with slides.

Most presentations require visuals; however, there are times when you can do without. Go for it! Nothing is more freeing or more intimate than you one-on-one with your audience. If you must have slides, then follow the one-idea one-slide rule. Slides crammed with information actually detract from your presentation. Here’s a tip: Write only what you can fit with a marker on a Post-it pad. Then, laying out the Post-its, you can rearrange slides getting a feel for the flow or argument of the talk.

Did you ever wonder why headlines like, “Why I never use this suture” and “How I cut my EMR documentation time in half” work so well? They tap into a core human instinct: curiosity. Your opening should introduce some sense of wonder. What is she going to share? Really, how does he do that? Starting with a problem and taking them to a solution is also a great game plan that will often yield success.

When it comes to slides, be clean and concise. Taking a cue from wildly popular TED talks, use images and art instead of words. Use sentence fragments, not sentences, and limit content to the width of the slide (no easy feat). Sometimes you need the slide to prompt your talking point. Put only the data or fact you need and leave the rest at the bottom in your notes section.

Humor is almost always a good idea and more difficult to execute than most realize. Cartoons with captions don’t work. I know that’s hard for many of you to hear, but it’s true. Delete them from your decks. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Instead, try finding something relevant to the audience that only they will find funny. Inside jokes not only have a higher chance of success, but will also help you bond with your audience. A joke about ICD10 as it relates to neurology is better than the funniest Calvin and Hobbes strip. Self-deprecating humor is always appreciated. I’m not among the gifted who can come up with a great one-liner on the spot. It’s OK to plan it ahead.

Once you’ve got your talk built, it’s time to run it. This is hard, as it requires planning to have your content done in time to rehearse. Find the discipline to do it. The first time you run it, you’ll likely realize that 1/3 of the content needs to be cut. Cut it. Indeed, plan to run 10% less than the time allotted. Leave your audience wanting for more rather than wishing for less.

As I’ve learned, your talking points and slides will always be most appreciated in your own head. Keeping to time shows your respect for your audience and makes you appear polished.

The day of, get to the venue well ahead of time and check the sound, lights, and temperature. All of your preparation will be for naught if they can’t hear you, see your slides, or feel their fingers due to the frigid AC.

One of the reasons I love giving talks is because they are live. You and your audience are intimately engaged, and like any conversation, you’ll sense how it’s going. Are they looking at you or at their phones? Do they seem bored? Do they laugh easily, even when you weren’t expecting them to? Observe what is happening and adjust your performance accordingly. Are you losing them? Pause. Let them catch up. Are you putting them to sleep? Pick up the pace. Try that bit of humor now.

Your delivery is critical to your success. If you’re on the dais and behind the podium of a large audience, then be big, Greek theatre big, which means bigger facial expressions and bigger arm and hand gestures. Vary the tone and pace of your voice. Speed it up to build excitement. Slow down and lower your pitch for gravity and authority. Pause for 3-4 seconds to create suspense and drama.

Leave time for discussion when possible. Invite the audience to engage by asking, What do you think? Finally, on the plane ride home, or even as you walk back from the auditorium to your clinic, think about your presentation: What worked? What fell flat? What roused the audience? How can you deliver it better next time?

Even if it didn’t go well, remember, there’s always next week. It’s on to Cincinnati.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I have to give a talk. Get this – the topic is how to give a good talk. Very meta.

I’ve given a hundred or so presentations in my career, including a couple of TEDx talks. With each one, I try to get a little better. Effective speaking is always simple but never easy. Let me share with you a few things I’ve learned.

Even if you don’t want to become a TEDMED phenom, you should know a few fundamentals. Giving good talks enhances your reputation and can jump-start your practice or career. For any talk, you must master three things: preparation, content, and delivery.

Just as we choose movies with actors we like, people choose speakers they want to see. Who you are matters. If you are introduced by an emcee, then be sure he or she bills you as a star. However, don’t try to be someone you aren’t – If I gave a talk on robotic prostate surgery, I’d be sure to lose no matter how witty I was. That’s why writing your own intro can sometimes be your best option.

Next up: content. It’s the king of speaking as well as marketing. Although you can pick up points for style, if you want to be remembered, you have to deliver something worth remembering. This starts with your preparation. Resist the temptation to focus exclusively on your slides. As in writing, it is best to brainstorm what you want to cover, then outline your ideas, then fill in content with slides.

Most presentations require visuals; however, there are times when you can do without. Go for it! Nothing is more freeing or more intimate than you one-on-one with your audience. If you must have slides, then follow the one-idea one-slide rule. Slides crammed with information actually detract from your presentation. Here’s a tip: Write only what you can fit with a marker on a Post-it pad. Then, laying out the Post-its, you can rearrange slides getting a feel for the flow or argument of the talk.

Did you ever wonder why headlines like, “Why I never use this suture” and “How I cut my EMR documentation time in half” work so well? They tap into a core human instinct: curiosity. Your opening should introduce some sense of wonder. What is she going to share? Really, how does he do that? Starting with a problem and taking them to a solution is also a great game plan that will often yield success.

When it comes to slides, be clean and concise. Taking a cue from wildly popular TED talks, use images and art instead of words. Use sentence fragments, not sentences, and limit content to the width of the slide (no easy feat). Sometimes you need the slide to prompt your talking point. Put only the data or fact you need and leave the rest at the bottom in your notes section.

Humor is almost always a good idea and more difficult to execute than most realize. Cartoons with captions don’t work. I know that’s hard for many of you to hear, but it’s true. Delete them from your decks. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Instead, try finding something relevant to the audience that only they will find funny. Inside jokes not only have a higher chance of success, but will also help you bond with your audience. A joke about ICD10 as it relates to neurology is better than the funniest Calvin and Hobbes strip. Self-deprecating humor is always appreciated. I’m not among the gifted who can come up with a great one-liner on the spot. It’s OK to plan it ahead.

Once you’ve got your talk built, it’s time to run it. This is hard, as it requires planning to have your content done in time to rehearse. Find the discipline to do it. The first time you run it, you’ll likely realize that 1/3 of the content needs to be cut. Cut it. Indeed, plan to run 10% less than the time allotted. Leave your audience wanting for more rather than wishing for less.

As I’ve learned, your talking points and slides will always be most appreciated in your own head. Keeping to time shows your respect for your audience and makes you appear polished.

The day of, get to the venue well ahead of time and check the sound, lights, and temperature. All of your preparation will be for naught if they can’t hear you, see your slides, or feel their fingers due to the frigid AC.

One of the reasons I love giving talks is because they are live. You and your audience are intimately engaged, and like any conversation, you’ll sense how it’s going. Are they looking at you or at their phones? Do they seem bored? Do they laugh easily, even when you weren’t expecting them to? Observe what is happening and adjust your performance accordingly. Are you losing them? Pause. Let them catch up. Are you putting them to sleep? Pick up the pace. Try that bit of humor now.

Your delivery is critical to your success. If you’re on the dais and behind the podium of a large audience, then be big, Greek theatre big, which means bigger facial expressions and bigger arm and hand gestures. Vary the tone and pace of your voice. Speed it up to build excitement. Slow down and lower your pitch for gravity and authority. Pause for 3-4 seconds to create suspense and drama.

Leave time for discussion when possible. Invite the audience to engage by asking, What do you think? Finally, on the plane ride home, or even as you walk back from the auditorium to your clinic, think about your presentation: What worked? What fell flat? What roused the audience? How can you deliver it better next time?

Even if it didn’t go well, remember, there’s always next week. It’s on to Cincinnati.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I have to give a talk. Get this – the topic is how to give a good talk. Very meta.

I’ve given a hundred or so presentations in my career, including a couple of TEDx talks. With each one, I try to get a little better. Effective speaking is always simple but never easy. Let me share with you a few things I’ve learned.

Even if you don’t want to become a TEDMED phenom, you should know a few fundamentals. Giving good talks enhances your reputation and can jump-start your practice or career. For any talk, you must master three things: preparation, content, and delivery.

Just as we choose movies with actors we like, people choose speakers they want to see. Who you are matters. If you are introduced by an emcee, then be sure he or she bills you as a star. However, don’t try to be someone you aren’t – If I gave a talk on robotic prostate surgery, I’d be sure to lose no matter how witty I was. That’s why writing your own intro can sometimes be your best option.

Next up: content. It’s the king of speaking as well as marketing. Although you can pick up points for style, if you want to be remembered, you have to deliver something worth remembering. This starts with your preparation. Resist the temptation to focus exclusively on your slides. As in writing, it is best to brainstorm what you want to cover, then outline your ideas, then fill in content with slides.

Most presentations require visuals; however, there are times when you can do without. Go for it! Nothing is more freeing or more intimate than you one-on-one with your audience. If you must have slides, then follow the one-idea one-slide rule. Slides crammed with information actually detract from your presentation. Here’s a tip: Write only what you can fit with a marker on a Post-it pad. Then, laying out the Post-its, you can rearrange slides getting a feel for the flow or argument of the talk.

Did you ever wonder why headlines like, “Why I never use this suture” and “How I cut my EMR documentation time in half” work so well? They tap into a core human instinct: curiosity. Your opening should introduce some sense of wonder. What is she going to share? Really, how does he do that? Starting with a problem and taking them to a solution is also a great game plan that will often yield success.

When it comes to slides, be clean and concise. Taking a cue from wildly popular TED talks, use images and art instead of words. Use sentence fragments, not sentences, and limit content to the width of the slide (no easy feat). Sometimes you need the slide to prompt your talking point. Put only the data or fact you need and leave the rest at the bottom in your notes section.

Humor is almost always a good idea and more difficult to execute than most realize. Cartoons with captions don’t work. I know that’s hard for many of you to hear, but it’s true. Delete them from your decks. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Instead, try finding something relevant to the audience that only they will find funny. Inside jokes not only have a higher chance of success, but will also help you bond with your audience. A joke about ICD10 as it relates to neurology is better than the funniest Calvin and Hobbes strip. Self-deprecating humor is always appreciated. I’m not among the gifted who can come up with a great one-liner on the spot. It’s OK to plan it ahead.

Once you’ve got your talk built, it’s time to run it. This is hard, as it requires planning to have your content done in time to rehearse. Find the discipline to do it. The first time you run it, you’ll likely realize that 1/3 of the content needs to be cut. Cut it. Indeed, plan to run 10% less than the time allotted. Leave your audience wanting for more rather than wishing for less.

As I’ve learned, your talking points and slides will always be most appreciated in your own head. Keeping to time shows your respect for your audience and makes you appear polished.

The day of, get to the venue well ahead of time and check the sound, lights, and temperature. All of your preparation will be for naught if they can’t hear you, see your slides, or feel their fingers due to the frigid AC.

One of the reasons I love giving talks is because they are live. You and your audience are intimately engaged, and like any conversation, you’ll sense how it’s going. Are they looking at you or at their phones? Do they seem bored? Do they laugh easily, even when you weren’t expecting them to? Observe what is happening and adjust your performance accordingly. Are you losing them? Pause. Let them catch up. Are you putting them to sleep? Pick up the pace. Try that bit of humor now.

Your delivery is critical to your success. If you’re on the dais and behind the podium of a large audience, then be big, Greek theatre big, which means bigger facial expressions and bigger arm and hand gestures. Vary the tone and pace of your voice. Speed it up to build excitement. Slow down and lower your pitch for gravity and authority. Pause for 3-4 seconds to create suspense and drama.

Leave time for discussion when possible. Invite the audience to engage by asking, What do you think? Finally, on the plane ride home, or even as you walk back from the auditorium to your clinic, think about your presentation: What worked? What fell flat? What roused the audience? How can you deliver it better next time?

Even if it didn’t go well, remember, there’s always next week. It’s on to Cincinnati.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

GERD postop relapse rates highest in women, older adults

Healthy men younger than 45 years have the lowest risk of relapse after reflux surgery compared with other demographic subgroups, according to data from a population-based study of 2,655 adults in Sweden. The findings were published online in JAMA.

“Cohort studies have shown a high risk of recurrent symptoms of GERD after surgery, which may have contributed to the decline in the use of antireflux surgery,” but long-term reflux recurrence rates and potential risk factors have not been well studied, wrote John Maret-Ouda, MD, and colleagues at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Overall, 18% of the patients suffered a reflux relapse; 84% of these were prescribed long-term medication, and 16% underwent additional surgery.

The highest relapse rates occurred among women, older patients, and those with comorbid conditions. Reflux occurred in 22% of women vs. 14% of men (hazard ratio 1.57), and the hazard ratio was 1.41 for patients aged 61 years and older compared with those aged 45 years and younger. Patients with one or more comorbidities were approximately one-third more likely to have a recurrence of reflux, compared with those who had no comorbidities (hazard ratio 1.36).

Approximately 4% of patients reported complications; the most common complication was infection (1.1%), followed by bleeding (0.9%), and esophageal perforation (0.9%).

The recurrence rate of 18% is low compared with other studies, the researchers noted. Possible reasons for the difference include the population-based design of the current study, which meant that no patients were lost to follow-up, as well as the recent time period, “in which laparoscopic antireflux surgery has become more centralized to expert centers where selection of patients might be stricter and the quality of surgery might be higher,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including clinical variations on coding, lack of data on certain confounding variables including body mass index and smoking, and a lack of control GERD patients who did not undergo antireflux surgery, the researchers said. The results suggest that the benefits of laparoscopic antireflux surgery may be diminished by the potential for recurrent GERD, they added.

The Swedish Research Council funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“The operation can be performed with a relatively low rate of morbidity and a very low mortality rate,” Stuart J. Spechler, MD, wrote in an editorial. “Although findings regarding GERD symptom relief and patient satisfaction based on medication usage data should be interpreted with caution, the observation that more than 80% of patients did not restart antireflux medications after laparoscopic antireflux surgery suggests that the operation provided long-lasting relief of GERD symptoms for most patients,” he said. Although surgery is not a permanent cure for all patients with GERD, “the ever-increasing number of proposed [proton pump inhibitor] risks has caused the greatest concern among clinicians and their patients,” said Dr. Spechler. “Whether the greater than 80% possibility of long-term freedom from PPIs and their associated risks warrants the 4% risk of acute surgical complications and the 17.7% risk of GERD recurrence is a decision that individual patients should make after a detailed discussion of these risks and benefits with their physicians,” he said. However, the study findings suggest “that laparoscopic antireflux surgery might be an especially appealing option for young and otherwise healthy men, who seem to have the lowest rate of GERD recurrence after antireflux surgery and who otherwise would likely require decades of PPI treatment without the operation,” he wrote (JAMA 2017;318:913-5).

Dr. Spechler is affiliated with Baylor University in Dallas. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and funding support from the National Institutes of Health.

“The operation can be performed with a relatively low rate of morbidity and a very low mortality rate,” Stuart J. Spechler, MD, wrote in an editorial. “Although findings regarding GERD symptom relief and patient satisfaction based on medication usage data should be interpreted with caution, the observation that more than 80% of patients did not restart antireflux medications after laparoscopic antireflux surgery suggests that the operation provided long-lasting relief of GERD symptoms for most patients,” he said. Although surgery is not a permanent cure for all patients with GERD, “the ever-increasing number of proposed [proton pump inhibitor] risks has caused the greatest concern among clinicians and their patients,” said Dr. Spechler. “Whether the greater than 80% possibility of long-term freedom from PPIs and their associated risks warrants the 4% risk of acute surgical complications and the 17.7% risk of GERD recurrence is a decision that individual patients should make after a detailed discussion of these risks and benefits with their physicians,” he said. However, the study findings suggest “that laparoscopic antireflux surgery might be an especially appealing option for young and otherwise healthy men, who seem to have the lowest rate of GERD recurrence after antireflux surgery and who otherwise would likely require decades of PPI treatment without the operation,” he wrote (JAMA 2017;318:913-5).

Dr. Spechler is affiliated with Baylor University in Dallas. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and funding support from the National Institutes of Health.

“The operation can be performed with a relatively low rate of morbidity and a very low mortality rate,” Stuart J. Spechler, MD, wrote in an editorial. “Although findings regarding GERD symptom relief and patient satisfaction based on medication usage data should be interpreted with caution, the observation that more than 80% of patients did not restart antireflux medications after laparoscopic antireflux surgery suggests that the operation provided long-lasting relief of GERD symptoms for most patients,” he said. Although surgery is not a permanent cure for all patients with GERD, “the ever-increasing number of proposed [proton pump inhibitor] risks has caused the greatest concern among clinicians and their patients,” said Dr. Spechler. “Whether the greater than 80% possibility of long-term freedom from PPIs and their associated risks warrants the 4% risk of acute surgical complications and the 17.7% risk of GERD recurrence is a decision that individual patients should make after a detailed discussion of these risks and benefits with their physicians,” he said. However, the study findings suggest “that laparoscopic antireflux surgery might be an especially appealing option for young and otherwise healthy men, who seem to have the lowest rate of GERD recurrence after antireflux surgery and who otherwise would likely require decades of PPI treatment without the operation,” he wrote (JAMA 2017;318:913-5).

Dr. Spechler is affiliated with Baylor University in Dallas. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and funding support from the National Institutes of Health.

Healthy men younger than 45 years have the lowest risk of relapse after reflux surgery compared with other demographic subgroups, according to data from a population-based study of 2,655 adults in Sweden. The findings were published online in JAMA.

“Cohort studies have shown a high risk of recurrent symptoms of GERD after surgery, which may have contributed to the decline in the use of antireflux surgery,” but long-term reflux recurrence rates and potential risk factors have not been well studied, wrote John Maret-Ouda, MD, and colleagues at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Overall, 18% of the patients suffered a reflux relapse; 84% of these were prescribed long-term medication, and 16% underwent additional surgery.

The highest relapse rates occurred among women, older patients, and those with comorbid conditions. Reflux occurred in 22% of women vs. 14% of men (hazard ratio 1.57), and the hazard ratio was 1.41 for patients aged 61 years and older compared with those aged 45 years and younger. Patients with one or more comorbidities were approximately one-third more likely to have a recurrence of reflux, compared with those who had no comorbidities (hazard ratio 1.36).

Approximately 4% of patients reported complications; the most common complication was infection (1.1%), followed by bleeding (0.9%), and esophageal perforation (0.9%).

The recurrence rate of 18% is low compared with other studies, the researchers noted. Possible reasons for the difference include the population-based design of the current study, which meant that no patients were lost to follow-up, as well as the recent time period, “in which laparoscopic antireflux surgery has become more centralized to expert centers where selection of patients might be stricter and the quality of surgery might be higher,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including clinical variations on coding, lack of data on certain confounding variables including body mass index and smoking, and a lack of control GERD patients who did not undergo antireflux surgery, the researchers said. The results suggest that the benefits of laparoscopic antireflux surgery may be diminished by the potential for recurrent GERD, they added.

The Swedish Research Council funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Healthy men younger than 45 years have the lowest risk of relapse after reflux surgery compared with other demographic subgroups, according to data from a population-based study of 2,655 adults in Sweden. The findings were published online in JAMA.

“Cohort studies have shown a high risk of recurrent symptoms of GERD after surgery, which may have contributed to the decline in the use of antireflux surgery,” but long-term reflux recurrence rates and potential risk factors have not been well studied, wrote John Maret-Ouda, MD, and colleagues at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Overall, 18% of the patients suffered a reflux relapse; 84% of these were prescribed long-term medication, and 16% underwent additional surgery.

The highest relapse rates occurred among women, older patients, and those with comorbid conditions. Reflux occurred in 22% of women vs. 14% of men (hazard ratio 1.57), and the hazard ratio was 1.41 for patients aged 61 years and older compared with those aged 45 years and younger. Patients with one or more comorbidities were approximately one-third more likely to have a recurrence of reflux, compared with those who had no comorbidities (hazard ratio 1.36).

Approximately 4% of patients reported complications; the most common complication was infection (1.1%), followed by bleeding (0.9%), and esophageal perforation (0.9%).

The recurrence rate of 18% is low compared with other studies, the researchers noted. Possible reasons for the difference include the population-based design of the current study, which meant that no patients were lost to follow-up, as well as the recent time period, “in which laparoscopic antireflux surgery has become more centralized to expert centers where selection of patients might be stricter and the quality of surgery might be higher,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including clinical variations on coding, lack of data on certain confounding variables including body mass index and smoking, and a lack of control GERD patients who did not undergo antireflux surgery, the researchers said. The results suggest that the benefits of laparoscopic antireflux surgery may be diminished by the potential for recurrent GERD, they added.

The Swedish Research Council funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Young men were less likely than were other demographic groups to experience recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux after surgery.

Major finding: Overall, 18% of 2,655 adults who underwent reflux surgery experienced recurrent reflux requiring long-term medication or additional surgery.

Data source: A population-based, retrospective cohort study of reflux surgery patients in Sweden.

Disclosures: The Swedish Research Council supported the study.

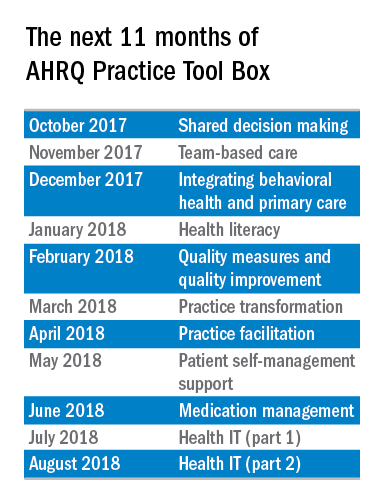

The AHRQ Practice Tool Box

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

Statins linked to lower death rates in COPD

Receiving a statin prescription within a year after diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was associated with a 21% decrease in the subsequent risk of all-cause mortality and a 45% drop in risk of pulmonary mortality, according to the results of a large retrospective administrative database study.

The findings belie those of the recent Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) trial, in which daily simvastatin (40 mg) did not affect exacerbation rates or time to first exacerbation in high-risk COPD patients, wrote Adam Raymakers, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates. Their study was observational, but the association between statin use and decreased mortality “persisted across several measures of statin exposure,” they wrote. “Our findings, in conjunction with previously reported evidence, suggests that there may be a specific subtype of COPD patients that may benefit from statin use.” The study appears in the September issue of Chest (2017;152;486-93).

To further explore the question, the researchers analyzed linked health databases from nearly 40,000 patients aged 50 years and older who had received at least three prescriptions for an anticholinergic or a short-acting beta agonist in 12 months some time between 1998 and 2007. The first prescription was considered the date of COPD “diagnosis.” The average age of the patients was 71 years; 55% were female.

A total of 7,775 patients (19.6%) who met this definition of incident COPD were prescribed a statin at least once during the subsequent year. These patients had a significantly reduced risk of subsequent all-cause mortality in univariate and multivariate analyses, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (95% confidence intervals, 0.68 to 0.91; P less than .002). Statins also showed a protective effect against pulmonary mortality, with univariate and multivariate hazard ratios of 0.52 (P = .01) and 0.55 (P = .03), respectively.

The protective effect of statins held up when the investigators narrowed the exposure period to 6 months after COPD diagnosis and when they expanded it to 18 months. Exposure to statins for 80% of the 1-year window after COPD diagnosis – a proxy for statin adherence – also led to a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, but the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio did not reach statistical significance (0.71 to 1.01; P = .06).

The most common prescription was for atorvastatin (49%), usually for 90 days (23%), 100 days (20%), or 30 days (15%), the researchers said. While the “possibility of the ‘healthy user’ or the ‘healthy adherer’ cannot be ignored,” they adjusted for other prescriptions, comorbidities, and income level, which should have helped eliminate this effect, they added. However, they lacked data on smoking and lung function assessments, both of which are “important confounders and contributors to mortality,” they acknowledged.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported the study. One coinvestigator disclosed consulting relationships with Teva, Pfizer, and Novartis. The others had no conflicts of interest.

Despite [its] limitations, the study results are intriguing and in line with findings from other retrospective cohorts. How then can we reconcile the apparent benefits observed in retrospective studies with the lack of clinical effect seen in prospective trials, particularly the Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) study? Could it be that both negative and positive studies are “correct”? Prospective studies have thus far not been adequately powered for mortality as an endpoint. Perhaps the choice of the particular statin matters? While STATCOPE involved simvastatin, the majority of the cohort reported by Raymakers et al. received atorvastatin. [Or perhaps] the negative results of STATCOPE could be related to careful selection of study participants with a low burden of systemic inflammation.

This most recent study reinforces the idea that statins may play a beneficial role in COPD, but it isn’t clear which patients to target for therapy. It is unlikely that the findings by Raymakers et al. will reverse recent recommendations by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society against the use of statins for the purpose of prevention of COPD exacerbations, but the suggestion of survival advantage related to statins certainly may breathe new life into an enthusiasm greatly tempered by STATCOPE.

Or Kalchiem-Dekel, MD, and Robert M. Reed, MD, are at the pulmonary and critical care medicine division, University of Maryland, Baltimore. Neither editorialist had conflicts of interest (Chest. 2017;152:456-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.156).

Despite [its] limitations, the study results are intriguing and in line with findings from other retrospective cohorts. How then can we reconcile the apparent benefits observed in retrospective studies with the lack of clinical effect seen in prospective trials, particularly the Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) study? Could it be that both negative and positive studies are “correct”? Prospective studies have thus far not been adequately powered for mortality as an endpoint. Perhaps the choice of the particular statin matters? While STATCOPE involved simvastatin, the majority of the cohort reported by Raymakers et al. received atorvastatin. [Or perhaps] the negative results of STATCOPE could be related to careful selection of study participants with a low burden of systemic inflammation.

This most recent study reinforces the idea that statins may play a beneficial role in COPD, but it isn’t clear which patients to target for therapy. It is unlikely that the findings by Raymakers et al. will reverse recent recommendations by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society against the use of statins for the purpose of prevention of COPD exacerbations, but the suggestion of survival advantage related to statins certainly may breathe new life into an enthusiasm greatly tempered by STATCOPE.

Or Kalchiem-Dekel, MD, and Robert M. Reed, MD, are at the pulmonary and critical care medicine division, University of Maryland, Baltimore. Neither editorialist had conflicts of interest (Chest. 2017;152:456-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.156).

Despite [its] limitations, the study results are intriguing and in line with findings from other retrospective cohorts. How then can we reconcile the apparent benefits observed in retrospective studies with the lack of clinical effect seen in prospective trials, particularly the Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) study? Could it be that both negative and positive studies are “correct”? Prospective studies have thus far not been adequately powered for mortality as an endpoint. Perhaps the choice of the particular statin matters? While STATCOPE involved simvastatin, the majority of the cohort reported by Raymakers et al. received atorvastatin. [Or perhaps] the negative results of STATCOPE could be related to careful selection of study participants with a low burden of systemic inflammation.

This most recent study reinforces the idea that statins may play a beneficial role in COPD, but it isn’t clear which patients to target for therapy. It is unlikely that the findings by Raymakers et al. will reverse recent recommendations by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society against the use of statins for the purpose of prevention of COPD exacerbations, but the suggestion of survival advantage related to statins certainly may breathe new life into an enthusiasm greatly tempered by STATCOPE.

Or Kalchiem-Dekel, MD, and Robert M. Reed, MD, are at the pulmonary and critical care medicine division, University of Maryland, Baltimore. Neither editorialist had conflicts of interest (Chest. 2017;152:456-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.156).

Receiving a statin prescription within a year after diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was associated with a 21% decrease in the subsequent risk of all-cause mortality and a 45% drop in risk of pulmonary mortality, according to the results of a large retrospective administrative database study.

The findings belie those of the recent Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) trial, in which daily simvastatin (40 mg) did not affect exacerbation rates or time to first exacerbation in high-risk COPD patients, wrote Adam Raymakers, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates. Their study was observational, but the association between statin use and decreased mortality “persisted across several measures of statin exposure,” they wrote. “Our findings, in conjunction with previously reported evidence, suggests that there may be a specific subtype of COPD patients that may benefit from statin use.” The study appears in the September issue of Chest (2017;152;486-93).

To further explore the question, the researchers analyzed linked health databases from nearly 40,000 patients aged 50 years and older who had received at least three prescriptions for an anticholinergic or a short-acting beta agonist in 12 months some time between 1998 and 2007. The first prescription was considered the date of COPD “diagnosis.” The average age of the patients was 71 years; 55% were female.

A total of 7,775 patients (19.6%) who met this definition of incident COPD were prescribed a statin at least once during the subsequent year. These patients had a significantly reduced risk of subsequent all-cause mortality in univariate and multivariate analyses, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (95% confidence intervals, 0.68 to 0.91; P less than .002). Statins also showed a protective effect against pulmonary mortality, with univariate and multivariate hazard ratios of 0.52 (P = .01) and 0.55 (P = .03), respectively.

The protective effect of statins held up when the investigators narrowed the exposure period to 6 months after COPD diagnosis and when they expanded it to 18 months. Exposure to statins for 80% of the 1-year window after COPD diagnosis – a proxy for statin adherence – also led to a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, but the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio did not reach statistical significance (0.71 to 1.01; P = .06).

The most common prescription was for atorvastatin (49%), usually for 90 days (23%), 100 days (20%), or 30 days (15%), the researchers said. While the “possibility of the ‘healthy user’ or the ‘healthy adherer’ cannot be ignored,” they adjusted for other prescriptions, comorbidities, and income level, which should have helped eliminate this effect, they added. However, they lacked data on smoking and lung function assessments, both of which are “important confounders and contributors to mortality,” they acknowledged.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported the study. One coinvestigator disclosed consulting relationships with Teva, Pfizer, and Novartis. The others had no conflicts of interest.

Receiving a statin prescription within a year after diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was associated with a 21% decrease in the subsequent risk of all-cause mortality and a 45% drop in risk of pulmonary mortality, according to the results of a large retrospective administrative database study.

The findings belie those of the recent Simvastatin in the Prevention of COPD Exacerbation (STATCOPE) trial, in which daily simvastatin (40 mg) did not affect exacerbation rates or time to first exacerbation in high-risk COPD patients, wrote Adam Raymakers, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates. Their study was observational, but the association between statin use and decreased mortality “persisted across several measures of statin exposure,” they wrote. “Our findings, in conjunction with previously reported evidence, suggests that there may be a specific subtype of COPD patients that may benefit from statin use.” The study appears in the September issue of Chest (2017;152;486-93).

To further explore the question, the researchers analyzed linked health databases from nearly 40,000 patients aged 50 years and older who had received at least three prescriptions for an anticholinergic or a short-acting beta agonist in 12 months some time between 1998 and 2007. The first prescription was considered the date of COPD “diagnosis.” The average age of the patients was 71 years; 55% were female.

A total of 7,775 patients (19.6%) who met this definition of incident COPD were prescribed a statin at least once during the subsequent year. These patients had a significantly reduced risk of subsequent all-cause mortality in univariate and multivariate analyses, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (95% confidence intervals, 0.68 to 0.91; P less than .002). Statins also showed a protective effect against pulmonary mortality, with univariate and multivariate hazard ratios of 0.52 (P = .01) and 0.55 (P = .03), respectively.

The protective effect of statins held up when the investigators narrowed the exposure period to 6 months after COPD diagnosis and when they expanded it to 18 months. Exposure to statins for 80% of the 1-year window after COPD diagnosis – a proxy for statin adherence – also led to a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, but the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio did not reach statistical significance (0.71 to 1.01; P = .06).

The most common prescription was for atorvastatin (49%), usually for 90 days (23%), 100 days (20%), or 30 days (15%), the researchers said. While the “possibility of the ‘healthy user’ or the ‘healthy adherer’ cannot be ignored,” they adjusted for other prescriptions, comorbidities, and income level, which should have helped eliminate this effect, they added. However, they lacked data on smoking and lung function assessments, both of which are “important confounders and contributors to mortality,” they acknowledged.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported the study. One coinvestigator disclosed consulting relationships with Teva, Pfizer, and Novartis. The others had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Statins might reduce the risk of death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Major finding: Statin use was associated with a 21% decrease in risk of all-cause mortality and a 45% decrease in risk of pulmonary mortality.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 39,678 patients with COPD, including 7,775 prescribed statins.

Disclosures: Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported the study. One coinvestigator disclosed consulting relationships with Teva, Pfizer, and Novartis. The others had no conflicts of interest.

Palliative care for patients suffering from severe persistent mental illness

While palliative care grows as an interdisciplinary specialty, more clinicians are asking how it can benefit certain patients with severe mental illness.

Palliative care, which developed with the founding of hospices in the 1960s, initially focused on patients who were dying from cancer. The specialty – which emphasizes improving patients’ quality of life rather than finding a cure, and which is different from hospice – can now be used for patients with noncancer diagnoses such as dementia and HIV/AIDS (Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;8[6]:212-15).

Some psychiatrists think that certain patients with another diagnosis would benefit from palliative care: those with severe persistent mental illness.

In fact, this approach might apply to psychiatric patients who are in long-term residential care with “severe/chronic schizophrenia and insufficient quality of life, those with therapy-refractory depressions and repeated suicide attempts, and those with severe long-standing therapy-refractory anorexia nervosa,” wrote Manuel Trachsel, MD, PhD, and his colleagues (BMC Psychiatry (2016 Jul 14:1-9).

Scott A. Irwin, MD, PhD, who coauthored that article and a letter examining these issues, said Dr. Trachsel’s theories lie on the frontiers of current thinking about incorporating palliative care and psychiatric medicine.

Meanwhile, both Dr. Irwin and Maria I. Lapid, MD, another psychiatrist with expertise in palliative care, said that in many ways, the field of psychiatry is inherently palliative in nature.

Palliative ‘approach’ in SPMI

Dr. Trachsel presented unpublished results from a survey of U.S. psychiatrists at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May that sought to discern whether they favored supporting short-term quality of life rather than long-term disease modification in certain patients with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) – defined as mental illness that is chronic or recurring, requires ongoing intensive psychiatric treatment, and seriously impairs functioning.

Specifically, a palliative care approach to SPMI could include a more relaxed use of agents considered potentially addictive or problematic long term, such as benzodiazepines, Dr. Trachsel said. For patients with medical decision-making capacity, it could 1) include withdrawal of care at a patient’s insistence or periods of intermittent sedation – which is used in palliative medicine for patients with intractable pain; or 2) mean switching a patient with end-stage anorexia and multiple failed treatment attempts to hospice care rather than force feeding, Dr. Trachsel said.

Neither Dr. Trachsel’s survey respondents nor those who attended his presentation seemed comfortable with the idea of extending the term “palliative care” – which is often and incorrectly associated with well-defined end-of-life scenarios – to serious, treatment-refractory mental illness. In those illnesses, disease trajectories may be less certain and futility is harder to define. They and other clinicians, however, did voice general support for the underlying concepts of promoting quality of life and decision-making autonomy for patients with SPMI, as well as palliative care targeted at the medical illnesses often acquired by those with SPMI.

According to Dr. Irwin and Dr. Lapid, reducing symptoms, acknowledging that there is no cure for SPMI, and focusing on optimizing patients’ quality of life would be core components of palliative care.

Futility difficult to define

Dr. Irwin said in an interview that the ideas in the letter (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;3[3]:200) in which he and a few other colleagues collaborated with Dr. Trachsel were essentially “a thought experiment and very philosophical.” In addition, the letter, which proposed palliative psychiatry “as a means to improve quality of care, person-centeredness, and autonomy” for patients with SPMI, was supported by a handful of case studies, most of them in patients with end-stage anorexia, he said. Furthermore, end-of-life interventions are only a subset of what palliative care brings to the table, said Dr. Irwin, palliative care psychiatrist at Cedars-Sinai Health System’s Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles.

With a psychiatric illness, the goals are usually around symptom management and quality of life, and for certain palliative care interventions reserved for end-of-life situations, “there’s usually not something knocking at the door that’s putting that end-of-life question into focus,” Dr. Irwin said. To create end-of-life protocols for SPMI, “you would need to know what the prognosis and trajectory are of each stage of these illnesses. And we don’t have good evidence guiding us.

“If we have a patient who is depressed and wants to commit suicide, who knows how many years they could have left if we intervene?” said Dr. Irwin, who has mentored Dr. Trachsel. “If we had the data that this person’s 90% likely to complete a suicide within the next year, it might change the conversation and treatment decisions.”

Dr. Lapid, a board-certified practitioner of palliative and hospice medicine and geriatric psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agreed in an interview that for patients with an SPMI and no life-limiting comorbidity, it becomes complicated to attempt to define futility.

Moreover, while Medicare and insurance have precisely detailed guidelines for hospice, which provides palliative care for those with a prognosis of 6 months or less, “there’s no psychiatric illness currently considered a terminal disease eligible for hospice care,” Dr. Lapid said.

Obstacles to access

Patients with SPMI die 25 years earlier than do their peers without SPMI. Most of the premature mortality associated with SPMI, which cuts across age groups, is attributable to chronic diseases rather than to violence or suicide. Less overall engagement with the health care system, leading to late treatment or undertreatment of disease, is one explanation for the premature mortality found among some people in this demographic.

In addition, studies have shown that individuals with SPMI have less access to palliative and hospice care. One study, for example, found that people with schizophrenia and a terminal illness went into hospice half as often as did people without SPMI (Schizophr Res. 2012 Nov;141:241-6). In a recent editorial, a team of psychiatrists and pain specialists called such disparities “unacceptable” and demanded cross-collaboration to resolve them (Gen Hospital Psych. 2017 Jan-Feb;44:1-3).

Dr. Lapid said one reason people with SPMI – with or without a life-limiting comorbidity – end up with less access to palliative and hospice care is that “the art of what we do in hospice and palliative care, advanced planning – is not something we do well or routinely in psychiatry.”

And palliative care specialists may find that for some people with severe mental illness, “it can be hard to really palliate their symptoms,” Dr. Lapid said.

Dr. Irwin noted that patients with SPMI and a terminal illness generally are not extended the same level of agency over their treatment choices as are people without it. Cancer patients, for example, can elect not to receive a treatment even when their prognosis is good. People with serious mental illness – even when they have life-limiting medical comorbidities – may not be given the option of deciding whether to opt for treatment.

Rebecca L. Bauer, MD, a psychosomatic medicine fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said that psychiatrists, including those with outpatient practices, are well positioned to help patients gain greater access to palliative care and end-of-life planning.

These patients’ medical needs become so pressing at the end of life that psychiatric disease and the distress it inflicts end up a secondary concern, she said, resulting in the patient suffering.

Psychiatrists “can play an important role in removing some of these barriers,” Dr. Bauer said, especially on multidisciplinary teams. For one thing, psychiatrists are adept at prescribing medications aimed at treating concurrent psychiatric symptoms. In addition, they are more likely than are other clinicians to have experience in communicating with patients with psychosis or other thought disorders.

Another important way psychiatrists can help secure access to palliative care for their patients who need it, she said, is to engage patients during times of relative wellness by encouraging them to discuss end-of-life desires and plans, and help them create formal health care directives.

“We know that sometimes patients [with SPMI] are not as engaged in their primary and medical care, and sometimes the psychiatrist is the only provider they consistently follow up with,” Dr. Bauer said.

All the clinicians interviewed acknowledged that, regardless of the feasibility or ethical viability of any single approach, the idea of incorporating some of the pillars of palliative care for patients with SPMI merits more consideration.

The approach used by psychiatrists treating patients with SPMI is very palliative in approach, Dr. Irwin and Dr. Lapid said. Psychiatrists reduce symptoms and acknowledge that SPMIs are chronic diseases for which there is no cure. To palliate is to make comfortable, to reduce symptoms, to reduce distress and pain, and to relieve suffering and optimize quality of life.

“In cancer, we’ve been telling people for 30 years, ‘keep fighting, because tomorrow there could be a new cure.’ But there’ve been very few new cures,” Dr. Irwin said. “And while some people want to fight to the end in case that cure comes, there are many who would have rather known that there really was little chance and might have made different choices.” In psychiatry, for psychiatric illnesses, he continued, “we need to really start thinking about the course of a person’s life, their quality of life, and the likelihood that they will get better or meet their goals, and what is a tolerable symptom burden for them. Because in the end, these questions apply to all patients.”

While palliative care grows as an interdisciplinary specialty, more clinicians are asking how it can benefit certain patients with severe mental illness.

Palliative care, which developed with the founding of hospices in the 1960s, initially focused on patients who were dying from cancer. The specialty – which emphasizes improving patients’ quality of life rather than finding a cure, and which is different from hospice – can now be used for patients with noncancer diagnoses such as dementia and HIV/AIDS (Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;8[6]:212-15).

Some psychiatrists think that certain patients with another diagnosis would benefit from palliative care: those with severe persistent mental illness.

In fact, this approach might apply to psychiatric patients who are in long-term residential care with “severe/chronic schizophrenia and insufficient quality of life, those with therapy-refractory depressions and repeated suicide attempts, and those with severe long-standing therapy-refractory anorexia nervosa,” wrote Manuel Trachsel, MD, PhD, and his colleagues (BMC Psychiatry (2016 Jul 14:1-9).

Scott A. Irwin, MD, PhD, who coauthored that article and a letter examining these issues, said Dr. Trachsel’s theories lie on the frontiers of current thinking about incorporating palliative care and psychiatric medicine.

Meanwhile, both Dr. Irwin and Maria I. Lapid, MD, another psychiatrist with expertise in palliative care, said that in many ways, the field of psychiatry is inherently palliative in nature.

Palliative ‘approach’ in SPMI

Dr. Trachsel presented unpublished results from a survey of U.S. psychiatrists at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May that sought to discern whether they favored supporting short-term quality of life rather than long-term disease modification in certain patients with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) – defined as mental illness that is chronic or recurring, requires ongoing intensive psychiatric treatment, and seriously impairs functioning.

Specifically, a palliative care approach to SPMI could include a more relaxed use of agents considered potentially addictive or problematic long term, such as benzodiazepines, Dr. Trachsel said. For patients with medical decision-making capacity, it could 1) include withdrawal of care at a patient’s insistence or periods of intermittent sedation – which is used in palliative medicine for patients with intractable pain; or 2) mean switching a patient with end-stage anorexia and multiple failed treatment attempts to hospice care rather than force feeding, Dr. Trachsel said.

Neither Dr. Trachsel’s survey respondents nor those who attended his presentation seemed comfortable with the idea of extending the term “palliative care” – which is often and incorrectly associated with well-defined end-of-life scenarios – to serious, treatment-refractory mental illness. In those illnesses, disease trajectories may be less certain and futility is harder to define. They and other clinicians, however, did voice general support for the underlying concepts of promoting quality of life and decision-making autonomy for patients with SPMI, as well as palliative care targeted at the medical illnesses often acquired by those with SPMI.

According to Dr. Irwin and Dr. Lapid, reducing symptoms, acknowledging that there is no cure for SPMI, and focusing on optimizing patients’ quality of life would be core components of palliative care.

Futility difficult to define

Dr. Irwin said in an interview that the ideas in the letter (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;3[3]:200) in which he and a few other colleagues collaborated with Dr. Trachsel were essentially “a thought experiment and very philosophical.” In addition, the letter, which proposed palliative psychiatry “as a means to improve quality of care, person-centeredness, and autonomy” for patients with SPMI, was supported by a handful of case studies, most of them in patients with end-stage anorexia, he said. Furthermore, end-of-life interventions are only a subset of what palliative care brings to the table, said Dr. Irwin, palliative care psychiatrist at Cedars-Sinai Health System’s Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles.

With a psychiatric illness, the goals are usually around symptom management and quality of life, and for certain palliative care interventions reserved for end-of-life situations, “there’s usually not something knocking at the door that’s putting that end-of-life question into focus,” Dr. Irwin said. To create end-of-life protocols for SPMI, “you would need to know what the prognosis and trajectory are of each stage of these illnesses. And we don’t have good evidence guiding us.

“If we have a patient who is depressed and wants to commit suicide, who knows how many years they could have left if we intervene?” said Dr. Irwin, who has mentored Dr. Trachsel. “If we had the data that this person’s 90% likely to complete a suicide within the next year, it might change the conversation and treatment decisions.”

Dr. Lapid, a board-certified practitioner of palliative and hospice medicine and geriatric psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agreed in an interview that for patients with an SPMI and no life-limiting comorbidity, it becomes complicated to attempt to define futility.

Moreover, while Medicare and insurance have precisely detailed guidelines for hospice, which provides palliative care for those with a prognosis of 6 months or less, “there’s no psychiatric illness currently considered a terminal disease eligible for hospice care,” Dr. Lapid said.

Obstacles to access

Patients with SPMI die 25 years earlier than do their peers without SPMI. Most of the premature mortality associated with SPMI, which cuts across age groups, is attributable to chronic diseases rather than to violence or suicide. Less overall engagement with the health care system, leading to late treatment or undertreatment of disease, is one explanation for the premature mortality found among some people in this demographic.

In addition, studies have shown that individuals with SPMI have less access to palliative and hospice care. One study, for example, found that people with schizophrenia and a terminal illness went into hospice half as often as did people without SPMI (Schizophr Res. 2012 Nov;141:241-6). In a recent editorial, a team of psychiatrists and pain specialists called such disparities “unacceptable” and demanded cross-collaboration to resolve them (Gen Hospital Psych. 2017 Jan-Feb;44:1-3).

Dr. Lapid said one reason people with SPMI – with or without a life-limiting comorbidity – end up with less access to palliative and hospice care is that “the art of what we do in hospice and palliative care, advanced planning – is not something we do well or routinely in psychiatry.”

And palliative care specialists may find that for some people with severe mental illness, “it can be hard to really palliate their symptoms,” Dr. Lapid said.

Dr. Irwin noted that patients with SPMI and a terminal illness generally are not extended the same level of agency over their treatment choices as are people without it. Cancer patients, for example, can elect not to receive a treatment even when their prognosis is good. People with serious mental illness – even when they have life-limiting medical comorbidities – may not be given the option of deciding whether to opt for treatment.

Rebecca L. Bauer, MD, a psychosomatic medicine fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said that psychiatrists, including those with outpatient practices, are well positioned to help patients gain greater access to palliative care and end-of-life planning.

These patients’ medical needs become so pressing at the end of life that psychiatric disease and the distress it inflicts end up a secondary concern, she said, resulting in the patient suffering.

Psychiatrists “can play an important role in removing some of these barriers,” Dr. Bauer said, especially on multidisciplinary teams. For one thing, psychiatrists are adept at prescribing medications aimed at treating concurrent psychiatric symptoms. In addition, they are more likely than are other clinicians to have experience in communicating with patients with psychosis or other thought disorders.

Another important way psychiatrists can help secure access to palliative care for their patients who need it, she said, is to engage patients during times of relative wellness by encouraging them to discuss end-of-life desires and plans, and help them create formal health care directives.

“We know that sometimes patients [with SPMI] are not as engaged in their primary and medical care, and sometimes the psychiatrist is the only provider they consistently follow up with,” Dr. Bauer said.

All the clinicians interviewed acknowledged that, regardless of the feasibility or ethical viability of any single approach, the idea of incorporating some of the pillars of palliative care for patients with SPMI merits more consideration.

The approach used by psychiatrists treating patients with SPMI is very palliative in approach, Dr. Irwin and Dr. Lapid said. Psychiatrists reduce symptoms and acknowledge that SPMIs are chronic diseases for which there is no cure. To palliate is to make comfortable, to reduce symptoms, to reduce distress and pain, and to relieve suffering and optimize quality of life.

“In cancer, we’ve been telling people for 30 years, ‘keep fighting, because tomorrow there could be a new cure.’ But there’ve been very few new cures,” Dr. Irwin said. “And while some people want to fight to the end in case that cure comes, there are many who would have rather known that there really was little chance and might have made different choices.” In psychiatry, for psychiatric illnesses, he continued, “we need to really start thinking about the course of a person’s life, their quality of life, and the likelihood that they will get better or meet their goals, and what is a tolerable symptom burden for them. Because in the end, these questions apply to all patients.”

While palliative care grows as an interdisciplinary specialty, more clinicians are asking how it can benefit certain patients with severe mental illness.

Palliative care, which developed with the founding of hospices in the 1960s, initially focused on patients who were dying from cancer. The specialty – which emphasizes improving patients’ quality of life rather than finding a cure, and which is different from hospice – can now be used for patients with noncancer diagnoses such as dementia and HIV/AIDS (Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;8[6]:212-15).

Some psychiatrists think that certain patients with another diagnosis would benefit from palliative care: those with severe persistent mental illness.

In fact, this approach might apply to psychiatric patients who are in long-term residential care with “severe/chronic schizophrenia and insufficient quality of life, those with therapy-refractory depressions and repeated suicide attempts, and those with severe long-standing therapy-refractory anorexia nervosa,” wrote Manuel Trachsel, MD, PhD, and his colleagues (BMC Psychiatry (2016 Jul 14:1-9).

Scott A. Irwin, MD, PhD, who coauthored that article and a letter examining these issues, said Dr. Trachsel’s theories lie on the frontiers of current thinking about incorporating palliative care and psychiatric medicine.

Meanwhile, both Dr. Irwin and Maria I. Lapid, MD, another psychiatrist with expertise in palliative care, said that in many ways, the field of psychiatry is inherently palliative in nature.

Palliative ‘approach’ in SPMI

Dr. Trachsel presented unpublished results from a survey of U.S. psychiatrists at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May that sought to discern whether they favored supporting short-term quality of life rather than long-term disease modification in certain patients with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) – defined as mental illness that is chronic or recurring, requires ongoing intensive psychiatric treatment, and seriously impairs functioning.

Specifically, a palliative care approach to SPMI could include a more relaxed use of agents considered potentially addictive or problematic long term, such as benzodiazepines, Dr. Trachsel said. For patients with medical decision-making capacity, it could 1) include withdrawal of care at a patient’s insistence or periods of intermittent sedation – which is used in palliative medicine for patients with intractable pain; or 2) mean switching a patient with end-stage anorexia and multiple failed treatment attempts to hospice care rather than force feeding, Dr. Trachsel said.

Neither Dr. Trachsel’s survey respondents nor those who attended his presentation seemed comfortable with the idea of extending the term “palliative care” – which is often and incorrectly associated with well-defined end-of-life scenarios – to serious, treatment-refractory mental illness. In those illnesses, disease trajectories may be less certain and futility is harder to define. They and other clinicians, however, did voice general support for the underlying concepts of promoting quality of life and decision-making autonomy for patients with SPMI, as well as palliative care targeted at the medical illnesses often acquired by those with SPMI.

According to Dr. Irwin and Dr. Lapid, reducing symptoms, acknowledging that there is no cure for SPMI, and focusing on optimizing patients’ quality of life would be core components of palliative care.

Futility difficult to define