User login

Add AFib to noncardiac surgery risk evaluation: New support

Practice has gone back and forth on whether atrial fibrillation (AFib) should be considered in the preoperative cardiovascular risk (CV) evaluation of patients slated for noncardiac surgery, and the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), currently widely used as an assessment tool, doesn’t include the arrhythmia.

But consideration of preexisting AFib along with the RCRI predicted 30-day mortality more sharply than the RCRI alone in an analysis of data covering several million patients slated for such procedures.

Indeed, AFib emerged as a significant, independent risk factor for a number of bad postoperative outcomes. Mortality within a month of the procedure climbed about 30% for patients with AFib before the noncardiac surgery. Their 30-day risks for stroke and for heart failure hospitalization went up similarly.

The addition of AFib to the RCRI significantly improved its ability to discriminate 30-day postoperative risk levels regardless of age, sex, and type of noncardiac surgery, Amgad Mentias, MD, Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. And “it was able to correctly up-classify patients to high risk, if AFib was there, and it was able to down-classify some patients to lower risk if it wasn’t there.”

“I think [the findings] are convincing evidence that atrial fib should at least be part of the thought process for the surgical team and the medical team taking care of the patient,” said Dr. Mentias, who is senior author on the study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, with lead author Sameer Prasada, MD, also of the Cleveland Clinic.

The results “call for incorporating AFib as a risk factor in perioperative risk scores for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” the published report states.

Supraventricular arrhythmias had been part of the Goldman Risk Index once widely used preoperatively to assess cardiac risk before practice adopted the RCRI in the past decade, observe Anne B. Curtis, MD, and Sai Krishna C. Korada, MD, University at Buffalo, New York, in an accompanying editorial.

The current findings “demonstrate improved prediction of adverse postsurgical outcomes” from supplementing the RCRI with AFib, they write. Given associations between preexisting AFib and serious cardiac events, “it is time to ‘re-revise’ the RCRI and acknowledge the importance of AFib in predicting adverse outcomes” after noncardiac surgery.

The new findings, however, aren’t all straightforward. In one result that remains a bit of a head-scratcher, postoperative risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with preexisting AFib went in the opposite direction of risk for death and other CV outcomes, falling by almost 20%.

That is “hard to explain with the available data,” the report states, but “the use of anticoagulation, whether oral or parenteral (as a bridge therapy in the perioperative period), is a plausible explanation” given the frequent role of thrombosis in triggering MIs.

Consistent with such a mechanism, the group argues, the MI risk reduction was seen primarily among patients with AFib and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or higher – that is, those at highest risk for stroke and therefore most likely to be on oral anticoagulation. The MI risk reduction wasn’t seen in such patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1.

“I think that’s part of the explanation, that anticoagulation can reduce risk of MI. But it’s not the whole explanation,” Dr. Mentias said in an interview. If it were the sole mechanism, he said, then the same oral anticoagulation that protected against MI should have also cut the postoperative stroke risk. Yet that risk climbed 40% among patients with preexisting AFib.

The analysis started with 8.6 million Medicare patients with planned noncardiac surgery, seen from 2015 to 2019, of whom 16.4% had preexisting AFib. Propensity matching for demographics, urgency and type of surgery, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and RCRI index created two cohorts for comparison: 1.13 million patients with and 1.92 million without preexisting AFib.

Preexisting AFib was associated with a higher 30-day risk for death from any cause, the primary endpoint being 8.3% versus 5.8% for those without such AFib (P < .001), for an odds ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.32).

Corresponding 30-day ORs for other events, all significant at P < .001, were:

- 1.31 (95% CI, 1.30-1.33) for heart failure

- 1.40 (95% CI, 1.37-1.43) for stroke

- 1.59 (95% CI, 1.43-1.75) for systemic embolism

- 1.14 (95% CI, 1.13-1.16) for major bleeding

- 0.81 (95% CI, 0.79-0.82) for MI

Those with preexisting AFib also had longer hospitalizations at a median 5 days, compared with 4 days for those without such AFib (P < .001).

The study has the limitations of most any retrospective cohort analysis. Other limitations, the report notes, include lack of information on any antiarrhythmic meds given during hospitalization or type of AFib.

For example, AFib that is permanent – compared with paroxysmal or persistent – may be associated with more atrial fibrosis, greater atrial dilatation, “and probably higher pressures inside the heart,” Dr. Mentias observed.

“That’s not always the case, but that’s the notion. So presumably people with persistent or permanent atrial fib would have more advanced heart disease, and that could imply more risk. But we did not have that kind of data.”

Dr. Mentias and Dr. Prasada report no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Curtis discloses serving on advisory boards for Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Milestone Pharmaceuticals; receiving honoraria for speaking from Medtronic and Zoll; and serving on a data-monitoring board for Medtronic. Dr. Korada reports he has no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Practice has gone back and forth on whether atrial fibrillation (AFib) should be considered in the preoperative cardiovascular risk (CV) evaluation of patients slated for noncardiac surgery, and the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), currently widely used as an assessment tool, doesn’t include the arrhythmia.

But consideration of preexisting AFib along with the RCRI predicted 30-day mortality more sharply than the RCRI alone in an analysis of data covering several million patients slated for such procedures.

Indeed, AFib emerged as a significant, independent risk factor for a number of bad postoperative outcomes. Mortality within a month of the procedure climbed about 30% for patients with AFib before the noncardiac surgery. Their 30-day risks for stroke and for heart failure hospitalization went up similarly.

The addition of AFib to the RCRI significantly improved its ability to discriminate 30-day postoperative risk levels regardless of age, sex, and type of noncardiac surgery, Amgad Mentias, MD, Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. And “it was able to correctly up-classify patients to high risk, if AFib was there, and it was able to down-classify some patients to lower risk if it wasn’t there.”

“I think [the findings] are convincing evidence that atrial fib should at least be part of the thought process for the surgical team and the medical team taking care of the patient,” said Dr. Mentias, who is senior author on the study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, with lead author Sameer Prasada, MD, also of the Cleveland Clinic.

The results “call for incorporating AFib as a risk factor in perioperative risk scores for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” the published report states.

Supraventricular arrhythmias had been part of the Goldman Risk Index once widely used preoperatively to assess cardiac risk before practice adopted the RCRI in the past decade, observe Anne B. Curtis, MD, and Sai Krishna C. Korada, MD, University at Buffalo, New York, in an accompanying editorial.

The current findings “demonstrate improved prediction of adverse postsurgical outcomes” from supplementing the RCRI with AFib, they write. Given associations between preexisting AFib and serious cardiac events, “it is time to ‘re-revise’ the RCRI and acknowledge the importance of AFib in predicting adverse outcomes” after noncardiac surgery.

The new findings, however, aren’t all straightforward. In one result that remains a bit of a head-scratcher, postoperative risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with preexisting AFib went in the opposite direction of risk for death and other CV outcomes, falling by almost 20%.

That is “hard to explain with the available data,” the report states, but “the use of anticoagulation, whether oral or parenteral (as a bridge therapy in the perioperative period), is a plausible explanation” given the frequent role of thrombosis in triggering MIs.

Consistent with such a mechanism, the group argues, the MI risk reduction was seen primarily among patients with AFib and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or higher – that is, those at highest risk for stroke and therefore most likely to be on oral anticoagulation. The MI risk reduction wasn’t seen in such patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1.

“I think that’s part of the explanation, that anticoagulation can reduce risk of MI. But it’s not the whole explanation,” Dr. Mentias said in an interview. If it were the sole mechanism, he said, then the same oral anticoagulation that protected against MI should have also cut the postoperative stroke risk. Yet that risk climbed 40% among patients with preexisting AFib.

The analysis started with 8.6 million Medicare patients with planned noncardiac surgery, seen from 2015 to 2019, of whom 16.4% had preexisting AFib. Propensity matching for demographics, urgency and type of surgery, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and RCRI index created two cohorts for comparison: 1.13 million patients with and 1.92 million without preexisting AFib.

Preexisting AFib was associated with a higher 30-day risk for death from any cause, the primary endpoint being 8.3% versus 5.8% for those without such AFib (P < .001), for an odds ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.32).

Corresponding 30-day ORs for other events, all significant at P < .001, were:

- 1.31 (95% CI, 1.30-1.33) for heart failure

- 1.40 (95% CI, 1.37-1.43) for stroke

- 1.59 (95% CI, 1.43-1.75) for systemic embolism

- 1.14 (95% CI, 1.13-1.16) for major bleeding

- 0.81 (95% CI, 0.79-0.82) for MI

Those with preexisting AFib also had longer hospitalizations at a median 5 days, compared with 4 days for those without such AFib (P < .001).

The study has the limitations of most any retrospective cohort analysis. Other limitations, the report notes, include lack of information on any antiarrhythmic meds given during hospitalization or type of AFib.

For example, AFib that is permanent – compared with paroxysmal or persistent – may be associated with more atrial fibrosis, greater atrial dilatation, “and probably higher pressures inside the heart,” Dr. Mentias observed.

“That’s not always the case, but that’s the notion. So presumably people with persistent or permanent atrial fib would have more advanced heart disease, and that could imply more risk. But we did not have that kind of data.”

Dr. Mentias and Dr. Prasada report no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Curtis discloses serving on advisory boards for Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Milestone Pharmaceuticals; receiving honoraria for speaking from Medtronic and Zoll; and serving on a data-monitoring board for Medtronic. Dr. Korada reports he has no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Practice has gone back and forth on whether atrial fibrillation (AFib) should be considered in the preoperative cardiovascular risk (CV) evaluation of patients slated for noncardiac surgery, and the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), currently widely used as an assessment tool, doesn’t include the arrhythmia.

But consideration of preexisting AFib along with the RCRI predicted 30-day mortality more sharply than the RCRI alone in an analysis of data covering several million patients slated for such procedures.

Indeed, AFib emerged as a significant, independent risk factor for a number of bad postoperative outcomes. Mortality within a month of the procedure climbed about 30% for patients with AFib before the noncardiac surgery. Their 30-day risks for stroke and for heart failure hospitalization went up similarly.

The addition of AFib to the RCRI significantly improved its ability to discriminate 30-day postoperative risk levels regardless of age, sex, and type of noncardiac surgery, Amgad Mentias, MD, Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. And “it was able to correctly up-classify patients to high risk, if AFib was there, and it was able to down-classify some patients to lower risk if it wasn’t there.”

“I think [the findings] are convincing evidence that atrial fib should at least be part of the thought process for the surgical team and the medical team taking care of the patient,” said Dr. Mentias, who is senior author on the study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, with lead author Sameer Prasada, MD, also of the Cleveland Clinic.

The results “call for incorporating AFib as a risk factor in perioperative risk scores for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” the published report states.

Supraventricular arrhythmias had been part of the Goldman Risk Index once widely used preoperatively to assess cardiac risk before practice adopted the RCRI in the past decade, observe Anne B. Curtis, MD, and Sai Krishna C. Korada, MD, University at Buffalo, New York, in an accompanying editorial.

The current findings “demonstrate improved prediction of adverse postsurgical outcomes” from supplementing the RCRI with AFib, they write. Given associations between preexisting AFib and serious cardiac events, “it is time to ‘re-revise’ the RCRI and acknowledge the importance of AFib in predicting adverse outcomes” after noncardiac surgery.

The new findings, however, aren’t all straightforward. In one result that remains a bit of a head-scratcher, postoperative risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with preexisting AFib went in the opposite direction of risk for death and other CV outcomes, falling by almost 20%.

That is “hard to explain with the available data,” the report states, but “the use of anticoagulation, whether oral or parenteral (as a bridge therapy in the perioperative period), is a plausible explanation” given the frequent role of thrombosis in triggering MIs.

Consistent with such a mechanism, the group argues, the MI risk reduction was seen primarily among patients with AFib and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or higher – that is, those at highest risk for stroke and therefore most likely to be on oral anticoagulation. The MI risk reduction wasn’t seen in such patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1.

“I think that’s part of the explanation, that anticoagulation can reduce risk of MI. But it’s not the whole explanation,” Dr. Mentias said in an interview. If it were the sole mechanism, he said, then the same oral anticoagulation that protected against MI should have also cut the postoperative stroke risk. Yet that risk climbed 40% among patients with preexisting AFib.

The analysis started with 8.6 million Medicare patients with planned noncardiac surgery, seen from 2015 to 2019, of whom 16.4% had preexisting AFib. Propensity matching for demographics, urgency and type of surgery, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and RCRI index created two cohorts for comparison: 1.13 million patients with and 1.92 million without preexisting AFib.

Preexisting AFib was associated with a higher 30-day risk for death from any cause, the primary endpoint being 8.3% versus 5.8% for those without such AFib (P < .001), for an odds ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.32).

Corresponding 30-day ORs for other events, all significant at P < .001, were:

- 1.31 (95% CI, 1.30-1.33) for heart failure

- 1.40 (95% CI, 1.37-1.43) for stroke

- 1.59 (95% CI, 1.43-1.75) for systemic embolism

- 1.14 (95% CI, 1.13-1.16) for major bleeding

- 0.81 (95% CI, 0.79-0.82) for MI

Those with preexisting AFib also had longer hospitalizations at a median 5 days, compared with 4 days for those without such AFib (P < .001).

The study has the limitations of most any retrospective cohort analysis. Other limitations, the report notes, include lack of information on any antiarrhythmic meds given during hospitalization or type of AFib.

For example, AFib that is permanent – compared with paroxysmal or persistent – may be associated with more atrial fibrosis, greater atrial dilatation, “and probably higher pressures inside the heart,” Dr. Mentias observed.

“That’s not always the case, but that’s the notion. So presumably people with persistent or permanent atrial fib would have more advanced heart disease, and that could imply more risk. But we did not have that kind of data.”

Dr. Mentias and Dr. Prasada report no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Curtis discloses serving on advisory boards for Abbott, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Milestone Pharmaceuticals; receiving honoraria for speaking from Medtronic and Zoll; and serving on a data-monitoring board for Medtronic. Dr. Korada reports he has no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

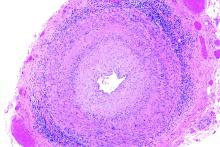

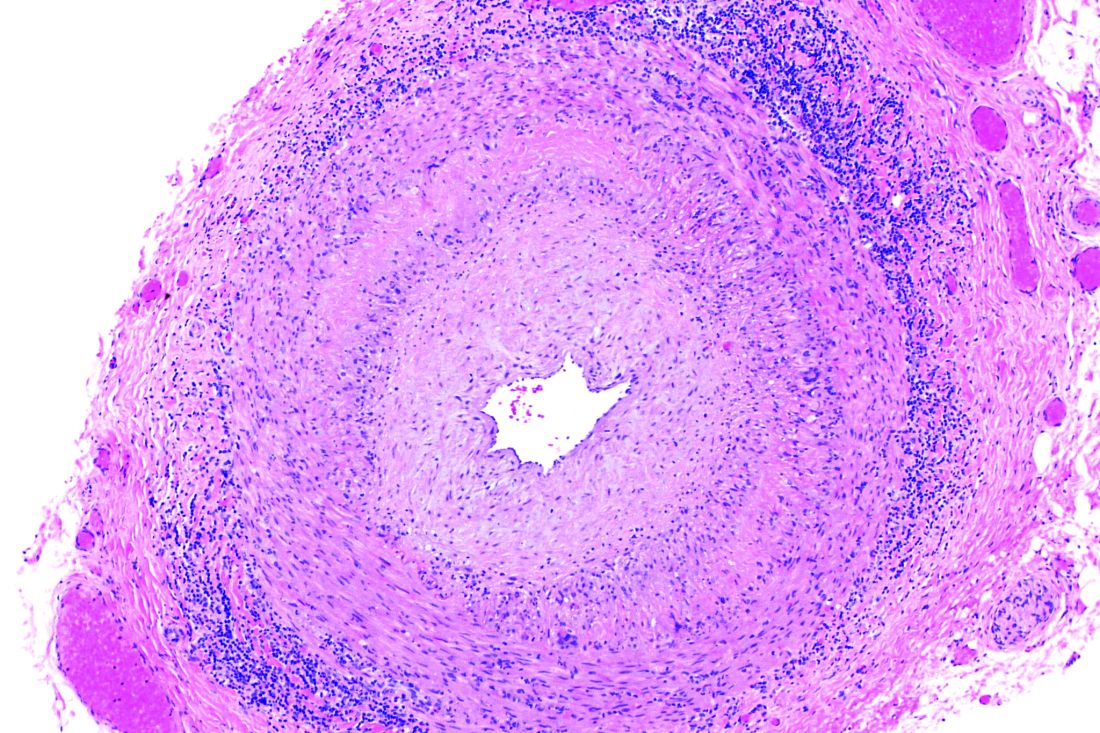

Updated AHA/ASA guideline changes care for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage

Many strategies widely considered “standard care” for managing spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are not as effective as previously thought and are no longer recommended in updated guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA).

Compression stockings, antiseizure medication, and steroid treatment are among the treatments with uncertain effectiveness, the writing group says.

The 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous ICH was published online in Stroke. The 80-page document contains major changes and refinements to the 2015 guideline on ICH management.

“Advances have been made in an array of fields related to ICH, including the organization of regional health care systems, reversal of the negative effects of blood thinners, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and the underlying disease in small blood vessels,” Steven M. Greenberg, MD, PhD, chair of the guideline writing group with Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in a news release.

“We’ve updated sections across the board. There’s probably no area that went untouched with some tweaking and new evidence added that led to some changes in level of evidence or strength of a recommendation,” Dr. Greenberg added in an interview with this news organization.

“Each section comes with knowledge gaps, and it wasn’t hard to come up with knowledge gaps in every section,” Dr. Greenberg acknowledged.

Time-honored treatments no more?

Among the key updates are changes to some “time-honored” treatments that continue to be used with some “regularity” for patients with ICH, yet appear to confer either no benefit or harm, Dr. Greenberg said.

For example, for emergency or critical care treatment of ICH, prophylactic corticosteroids or continuous hyperosmolar therapy is not recommended, because it appears to have no benefit for outcome, while use of platelet transfusions outside the setting of emergency surgery or severe thrombocytopenia appears to worsen outcome, the authors say.

Use of graduated knee- or thigh-high compression stockings alone is not an effective prophylactic therapy for prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Instead, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) starting on the day of diagnosis is now recommended for DVT prophylaxis.

“This is an area where we still have a lot of exploration to do. It is unclear whether even specialized compression devices reduce the risks of deep vein thrombosis or improve the overall health of people with a brain bleed,” Dr. Greenberg said in the release.

The new guidance advises against use of antiseizure or antidepressant medications for ICH patients in whom there is no evidence of seizures or depression.

In clinical trials, antiseizure medication did not contribute to improvements in functionality or long-term seizure control, and the use of antidepressants increased the chance of bone fractures, the authors say.

The guideline also provides updated recommendations for acute reversal of anticoagulation after ICH. It highlights the use of protein complex concentrate for reversal of vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin; idarucizumab for reversal of the thrombin inhibitor dabigatran; and andexanet alfa for reversal of factor Xa inhibitors, such as rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

For acute blood pressure lowering after mild to moderate ICH, treatment regimens that limit blood pressure variability and achieve smooth, sustained blood pressure control appear to reduce hematoma expansion and yield better functional outcome, the guideline says.

It also notes that minimally invasive approaches for hematoma evacuation, compared with medical management alone‚ have been shown to reduce mortality.

For patients with cerebellar hemorrhage, indications for immediate surgical evacuation with or without an external ventricular drain to reduce mortality now include larger volume (> 15 mL) in addition to previously recommended indications of neurologic deterioration, brainstem compression, and hydrocephalus, the authors note.

However, a “major knowledge gap is whether we can improve functional outcome with hematoma evacuation,” Dr. Greenberg said.

Multidisciplinary care

For rehabilitation after ICH, the guideline reinforces the importance of having a multidisciplinary team to develop a comprehensive plan for recovery.

Starting rehabilitation activities such as stretching and functional task training may be considered 24 to 48 hours following mild or moderate ICH. However, early aggressive mobilization within the first 24 hours has been linked to an increased risk of death within 14 days after an ICH, the guideline says.

Knowledge gaps include how soon it’s safe to return to work, drive, and participate in other social engagements. Recommendations on sexual activity and exercise levels that are safe after a stroke are also needed.

“People need additional help with these lifestyle changes, whether it’s moving around more, curbing their alcohol use, or eating healthier foods. This all happens after they leave the hospital, and we need to be sure we are empowering families with the information they may need to be properly supportive,” Dr. Greenberg says in the release.

The guideline points to the patient’s home caregiver as a “key and sometimes overlooked” member of the care team. It recommends psychosocial education, practical support, and training for the caregiver to improve the patient’s balance, activity level, and overall quality of life.

Opportunity for prevention?

The guideline also suggests there may be an opportunity to prevent ICH in some people through neuroimaging markers.

While neuroimaging is not routinely performed as a part of risk stratification for primary ICH risk, damage to small blood vessels that is associated with ICH may be evident on MRI that could signal future ICH risk, the guideline says.

“We added to the guidelines for the first time a section on mostly imaging markers of risk for having a first-ever hemorrhage,” Dr. Greenberg said in an interview.

“We don’t make any recommendations as to how to act on these markers because there is a knowledge gap. The hope is that we’ll see growth in our ability to predict first-ever hemorrhage and be able to do things to prevent first-ever hemorrhage,” he said.

“We believe the wide range of knowledge set forth in the new guideline will translate into meaningful improvements in ICH care,” Dr. Greenberg adds in the release.

The updated guideline has been endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology, and the Neurocritical Care Society. The American Academy of Neurology has affirmed the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists.

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Greenberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of disclosures for the guideline group is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many strategies widely considered “standard care” for managing spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are not as effective as previously thought and are no longer recommended in updated guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA).

Compression stockings, antiseizure medication, and steroid treatment are among the treatments with uncertain effectiveness, the writing group says.

The 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous ICH was published online in Stroke. The 80-page document contains major changes and refinements to the 2015 guideline on ICH management.

“Advances have been made in an array of fields related to ICH, including the organization of regional health care systems, reversal of the negative effects of blood thinners, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and the underlying disease in small blood vessels,” Steven M. Greenberg, MD, PhD, chair of the guideline writing group with Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in a news release.

“We’ve updated sections across the board. There’s probably no area that went untouched with some tweaking and new evidence added that led to some changes in level of evidence or strength of a recommendation,” Dr. Greenberg added in an interview with this news organization.

“Each section comes with knowledge gaps, and it wasn’t hard to come up with knowledge gaps in every section,” Dr. Greenberg acknowledged.

Time-honored treatments no more?

Among the key updates are changes to some “time-honored” treatments that continue to be used with some “regularity” for patients with ICH, yet appear to confer either no benefit or harm, Dr. Greenberg said.

For example, for emergency or critical care treatment of ICH, prophylactic corticosteroids or continuous hyperosmolar therapy is not recommended, because it appears to have no benefit for outcome, while use of platelet transfusions outside the setting of emergency surgery or severe thrombocytopenia appears to worsen outcome, the authors say.

Use of graduated knee- or thigh-high compression stockings alone is not an effective prophylactic therapy for prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Instead, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) starting on the day of diagnosis is now recommended for DVT prophylaxis.

“This is an area where we still have a lot of exploration to do. It is unclear whether even specialized compression devices reduce the risks of deep vein thrombosis or improve the overall health of people with a brain bleed,” Dr. Greenberg said in the release.

The new guidance advises against use of antiseizure or antidepressant medications for ICH patients in whom there is no evidence of seizures or depression.

In clinical trials, antiseizure medication did not contribute to improvements in functionality or long-term seizure control, and the use of antidepressants increased the chance of bone fractures, the authors say.

The guideline also provides updated recommendations for acute reversal of anticoagulation after ICH. It highlights the use of protein complex concentrate for reversal of vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin; idarucizumab for reversal of the thrombin inhibitor dabigatran; and andexanet alfa for reversal of factor Xa inhibitors, such as rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

For acute blood pressure lowering after mild to moderate ICH, treatment regimens that limit blood pressure variability and achieve smooth, sustained blood pressure control appear to reduce hematoma expansion and yield better functional outcome, the guideline says.

It also notes that minimally invasive approaches for hematoma evacuation, compared with medical management alone‚ have been shown to reduce mortality.

For patients with cerebellar hemorrhage, indications for immediate surgical evacuation with or without an external ventricular drain to reduce mortality now include larger volume (> 15 mL) in addition to previously recommended indications of neurologic deterioration, brainstem compression, and hydrocephalus, the authors note.

However, a “major knowledge gap is whether we can improve functional outcome with hematoma evacuation,” Dr. Greenberg said.

Multidisciplinary care

For rehabilitation after ICH, the guideline reinforces the importance of having a multidisciplinary team to develop a comprehensive plan for recovery.

Starting rehabilitation activities such as stretching and functional task training may be considered 24 to 48 hours following mild or moderate ICH. However, early aggressive mobilization within the first 24 hours has been linked to an increased risk of death within 14 days after an ICH, the guideline says.

Knowledge gaps include how soon it’s safe to return to work, drive, and participate in other social engagements. Recommendations on sexual activity and exercise levels that are safe after a stroke are also needed.

“People need additional help with these lifestyle changes, whether it’s moving around more, curbing their alcohol use, or eating healthier foods. This all happens after they leave the hospital, and we need to be sure we are empowering families with the information they may need to be properly supportive,” Dr. Greenberg says in the release.

The guideline points to the patient’s home caregiver as a “key and sometimes overlooked” member of the care team. It recommends psychosocial education, practical support, and training for the caregiver to improve the patient’s balance, activity level, and overall quality of life.

Opportunity for prevention?

The guideline also suggests there may be an opportunity to prevent ICH in some people through neuroimaging markers.

While neuroimaging is not routinely performed as a part of risk stratification for primary ICH risk, damage to small blood vessels that is associated with ICH may be evident on MRI that could signal future ICH risk, the guideline says.

“We added to the guidelines for the first time a section on mostly imaging markers of risk for having a first-ever hemorrhage,” Dr. Greenberg said in an interview.

“We don’t make any recommendations as to how to act on these markers because there is a knowledge gap. The hope is that we’ll see growth in our ability to predict first-ever hemorrhage and be able to do things to prevent first-ever hemorrhage,” he said.

“We believe the wide range of knowledge set forth in the new guideline will translate into meaningful improvements in ICH care,” Dr. Greenberg adds in the release.

The updated guideline has been endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology, and the Neurocritical Care Society. The American Academy of Neurology has affirmed the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists.

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Greenberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of disclosures for the guideline group is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many strategies widely considered “standard care” for managing spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are not as effective as previously thought and are no longer recommended in updated guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA).

Compression stockings, antiseizure medication, and steroid treatment are among the treatments with uncertain effectiveness, the writing group says.

The 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous ICH was published online in Stroke. The 80-page document contains major changes and refinements to the 2015 guideline on ICH management.

“Advances have been made in an array of fields related to ICH, including the organization of regional health care systems, reversal of the negative effects of blood thinners, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and the underlying disease in small blood vessels,” Steven M. Greenberg, MD, PhD, chair of the guideline writing group with Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in a news release.

“We’ve updated sections across the board. There’s probably no area that went untouched with some tweaking and new evidence added that led to some changes in level of evidence or strength of a recommendation,” Dr. Greenberg added in an interview with this news organization.

“Each section comes with knowledge gaps, and it wasn’t hard to come up with knowledge gaps in every section,” Dr. Greenberg acknowledged.

Time-honored treatments no more?

Among the key updates are changes to some “time-honored” treatments that continue to be used with some “regularity” for patients with ICH, yet appear to confer either no benefit or harm, Dr. Greenberg said.

For example, for emergency or critical care treatment of ICH, prophylactic corticosteroids or continuous hyperosmolar therapy is not recommended, because it appears to have no benefit for outcome, while use of platelet transfusions outside the setting of emergency surgery or severe thrombocytopenia appears to worsen outcome, the authors say.

Use of graduated knee- or thigh-high compression stockings alone is not an effective prophylactic therapy for prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Instead, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) starting on the day of diagnosis is now recommended for DVT prophylaxis.

“This is an area where we still have a lot of exploration to do. It is unclear whether even specialized compression devices reduce the risks of deep vein thrombosis or improve the overall health of people with a brain bleed,” Dr. Greenberg said in the release.

The new guidance advises against use of antiseizure or antidepressant medications for ICH patients in whom there is no evidence of seizures or depression.

In clinical trials, antiseizure medication did not contribute to improvements in functionality or long-term seizure control, and the use of antidepressants increased the chance of bone fractures, the authors say.

The guideline also provides updated recommendations for acute reversal of anticoagulation after ICH. It highlights the use of protein complex concentrate for reversal of vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin; idarucizumab for reversal of the thrombin inhibitor dabigatran; and andexanet alfa for reversal of factor Xa inhibitors, such as rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

For acute blood pressure lowering after mild to moderate ICH, treatment regimens that limit blood pressure variability and achieve smooth, sustained blood pressure control appear to reduce hematoma expansion and yield better functional outcome, the guideline says.

It also notes that minimally invasive approaches for hematoma evacuation, compared with medical management alone‚ have been shown to reduce mortality.

For patients with cerebellar hemorrhage, indications for immediate surgical evacuation with or without an external ventricular drain to reduce mortality now include larger volume (> 15 mL) in addition to previously recommended indications of neurologic deterioration, brainstem compression, and hydrocephalus, the authors note.

However, a “major knowledge gap is whether we can improve functional outcome with hematoma evacuation,” Dr. Greenberg said.

Multidisciplinary care

For rehabilitation after ICH, the guideline reinforces the importance of having a multidisciplinary team to develop a comprehensive plan for recovery.

Starting rehabilitation activities such as stretching and functional task training may be considered 24 to 48 hours following mild or moderate ICH. However, early aggressive mobilization within the first 24 hours has been linked to an increased risk of death within 14 days after an ICH, the guideline says.

Knowledge gaps include how soon it’s safe to return to work, drive, and participate in other social engagements. Recommendations on sexual activity and exercise levels that are safe after a stroke are also needed.

“People need additional help with these lifestyle changes, whether it’s moving around more, curbing their alcohol use, or eating healthier foods. This all happens after they leave the hospital, and we need to be sure we are empowering families with the information they may need to be properly supportive,” Dr. Greenberg says in the release.

The guideline points to the patient’s home caregiver as a “key and sometimes overlooked” member of the care team. It recommends psychosocial education, practical support, and training for the caregiver to improve the patient’s balance, activity level, and overall quality of life.

Opportunity for prevention?

The guideline also suggests there may be an opportunity to prevent ICH in some people through neuroimaging markers.

While neuroimaging is not routinely performed as a part of risk stratification for primary ICH risk, damage to small blood vessels that is associated with ICH may be evident on MRI that could signal future ICH risk, the guideline says.

“We added to the guidelines for the first time a section on mostly imaging markers of risk for having a first-ever hemorrhage,” Dr. Greenberg said in an interview.

“We don’t make any recommendations as to how to act on these markers because there is a knowledge gap. The hope is that we’ll see growth in our ability to predict first-ever hemorrhage and be able to do things to prevent first-ever hemorrhage,” he said.

“We believe the wide range of knowledge set forth in the new guideline will translate into meaningful improvements in ICH care,” Dr. Greenberg adds in the release.

The updated guideline has been endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology, and the Neurocritical Care Society. The American Academy of Neurology has affirmed the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists.

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Greenberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of disclosures for the guideline group is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACST-2: Carotid stenting, surgery on par in asymptomatic patients

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.

The results showed the 30-day risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), or any stroke was 3.9% with carotid stenting and 3.2% with surgery (P = .26).

But with stenting, there was a slightly higher risk for procedural nondisabling strokes (48 vs. 29; P = .03), including 15 strokes vs. 5 strokes, respectively, that left patients with no residual symptoms. This is “consistent with large, recent nationally representative registry data,” observed Dr. Halliday, of the University of Oxford (England).

For those undergoing surgery, cranial nerve palsies were reported in 5.4% vs. no patients undergoing stenting.

At 5 years, the nonprocedural fatal or disabling stroke rate was 2.5% in each group (rate ratio [RR], 0.98; P = .91), with any nonprocedural stroke occurring in 5.3% of patients with stenting vs. 4.5% with surgery (RR, 1.16; P = .33).

The investigators performed a meta-analysis combining the ACST-2 results with those of eight prior trials (four in asymptomatic and four in symptomatic patients) that yielded a similar nonsignificant result for any nonprocedural stroke (RR, 1.11; P = .21).

Based on the results from ACST-2 plus the major trials, stenting and surgery involve “similar risks and similar benefits,” Dr. Halliday concluded.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, University Hospital of Geneva, said, “In centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

While the trial provides “good news” for patients, he pointed out that a reduction in the sample size from 5,000 to 3,625 limited the statistical power and that enrollment over a long period of time may have introduced confounders, such as changes in equipment technique, and medical therapy.

Also, many centers enrolled few patients, raising the concern over low-volume centers and operators, Dr. Roffi said. “We know that 8% of the centers enrolled 39% of the patients,” and “information on the credentialing and experience of the interventionalists was limited.”

Further, a lack of systematic MI assessment may have favored the surgery group, and more recent developments in stenting with the potential of reducing periprocedural stroke were rarely used, such as proximal emboli protection in only 15% and double-layer stents in 11%.

Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany, said that, as a vascular surgeon, he finds it understandable that there might be a higher incidence of nonfatal strokes when treating carotid stenosis with stents, given the vulnerability of these lesions.

“Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe, it has to be done in order to avoid strokes, and, obviously, there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Montalescot, however, said that what the study cannot address – and what was the subject of many online audience comments – is whether either intervention should be performed in these patients.

Unlike earlier trials comparing interventions to medical therapy, Dr. Halliday said ACST-2 enrolled patients for whom the decision had been made that revascularization was needed. In addition, 99%-100% were receiving antithrombotic therapy at baseline, 85%-90% were receiving antihypertensives, and about 85% were taking statins.

Longer-term follow-up should provide a better picture of the nonprocedural stroke risk, with patients asked annually about exactly what medications and doses they are taking, she said.

“We will have an enormous list of exactly what’s gone on and the intensity of that therapy, which is, of course, much more intense than when we carried out our first trial. But these were people in whom a procedure was thought to be necessary,” she noted.

When asked during the press conference which procedure she would choose, Dr. Halliday, a surgeon, observed that patient preference is important but that the nature of the lesion itself often determines the optimal choice.

“If you know the competence of the people doing it is equal, then the less invasive procedure – providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following for 10 years – is the more important,” she added.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Halliday reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.

The results showed the 30-day risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), or any stroke was 3.9% with carotid stenting and 3.2% with surgery (P = .26).

But with stenting, there was a slightly higher risk for procedural nondisabling strokes (48 vs. 29; P = .03), including 15 strokes vs. 5 strokes, respectively, that left patients with no residual symptoms. This is “consistent with large, recent nationally representative registry data,” observed Dr. Halliday, of the University of Oxford (England).

For those undergoing surgery, cranial nerve palsies were reported in 5.4% vs. no patients undergoing stenting.

At 5 years, the nonprocedural fatal or disabling stroke rate was 2.5% in each group (rate ratio [RR], 0.98; P = .91), with any nonprocedural stroke occurring in 5.3% of patients with stenting vs. 4.5% with surgery (RR, 1.16; P = .33).

The investigators performed a meta-analysis combining the ACST-2 results with those of eight prior trials (four in asymptomatic and four in symptomatic patients) that yielded a similar nonsignificant result for any nonprocedural stroke (RR, 1.11; P = .21).

Based on the results from ACST-2 plus the major trials, stenting and surgery involve “similar risks and similar benefits,” Dr. Halliday concluded.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, University Hospital of Geneva, said, “In centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

While the trial provides “good news” for patients, he pointed out that a reduction in the sample size from 5,000 to 3,625 limited the statistical power and that enrollment over a long period of time may have introduced confounders, such as changes in equipment technique, and medical therapy.

Also, many centers enrolled few patients, raising the concern over low-volume centers and operators, Dr. Roffi said. “We know that 8% of the centers enrolled 39% of the patients,” and “information on the credentialing and experience of the interventionalists was limited.”

Further, a lack of systematic MI assessment may have favored the surgery group, and more recent developments in stenting with the potential of reducing periprocedural stroke were rarely used, such as proximal emboli protection in only 15% and double-layer stents in 11%.

Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany, said that, as a vascular surgeon, he finds it understandable that there might be a higher incidence of nonfatal strokes when treating carotid stenosis with stents, given the vulnerability of these lesions.

“Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe, it has to be done in order to avoid strokes, and, obviously, there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Montalescot, however, said that what the study cannot address – and what was the subject of many online audience comments – is whether either intervention should be performed in these patients.

Unlike earlier trials comparing interventions to medical therapy, Dr. Halliday said ACST-2 enrolled patients for whom the decision had been made that revascularization was needed. In addition, 99%-100% were receiving antithrombotic therapy at baseline, 85%-90% were receiving antihypertensives, and about 85% were taking statins.

Longer-term follow-up should provide a better picture of the nonprocedural stroke risk, with patients asked annually about exactly what medications and doses they are taking, she said.

“We will have an enormous list of exactly what’s gone on and the intensity of that therapy, which is, of course, much more intense than when we carried out our first trial. But these were people in whom a procedure was thought to be necessary,” she noted.

When asked during the press conference which procedure she would choose, Dr. Halliday, a surgeon, observed that patient preference is important but that the nature of the lesion itself often determines the optimal choice.

“If you know the competence of the people doing it is equal, then the less invasive procedure – providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following for 10 years – is the more important,” she added.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Halliday reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.

The results showed the 30-day risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), or any stroke was 3.9% with carotid stenting and 3.2% with surgery (P = .26).

But with stenting, there was a slightly higher risk for procedural nondisabling strokes (48 vs. 29; P = .03), including 15 strokes vs. 5 strokes, respectively, that left patients with no residual symptoms. This is “consistent with large, recent nationally representative registry data,” observed Dr. Halliday, of the University of Oxford (England).

For those undergoing surgery, cranial nerve palsies were reported in 5.4% vs. no patients undergoing stenting.

At 5 years, the nonprocedural fatal or disabling stroke rate was 2.5% in each group (rate ratio [RR], 0.98; P = .91), with any nonprocedural stroke occurring in 5.3% of patients with stenting vs. 4.5% with surgery (RR, 1.16; P = .33).

The investigators performed a meta-analysis combining the ACST-2 results with those of eight prior trials (four in asymptomatic and four in symptomatic patients) that yielded a similar nonsignificant result for any nonprocedural stroke (RR, 1.11; P = .21).

Based on the results from ACST-2 plus the major trials, stenting and surgery involve “similar risks and similar benefits,” Dr. Halliday concluded.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, University Hospital of Geneva, said, “In centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

While the trial provides “good news” for patients, he pointed out that a reduction in the sample size from 5,000 to 3,625 limited the statistical power and that enrollment over a long period of time may have introduced confounders, such as changes in equipment technique, and medical therapy.

Also, many centers enrolled few patients, raising the concern over low-volume centers and operators, Dr. Roffi said. “We know that 8% of the centers enrolled 39% of the patients,” and “information on the credentialing and experience of the interventionalists was limited.”

Further, a lack of systematic MI assessment may have favored the surgery group, and more recent developments in stenting with the potential of reducing periprocedural stroke were rarely used, such as proximal emboli protection in only 15% and double-layer stents in 11%.

Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany, said that, as a vascular surgeon, he finds it understandable that there might be a higher incidence of nonfatal strokes when treating carotid stenosis with stents, given the vulnerability of these lesions.

“Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe, it has to be done in order to avoid strokes, and, obviously, there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Montalescot, however, said that what the study cannot address – and what was the subject of many online audience comments – is whether either intervention should be performed in these patients.

Unlike earlier trials comparing interventions to medical therapy, Dr. Halliday said ACST-2 enrolled patients for whom the decision had been made that revascularization was needed. In addition, 99%-100% were receiving antithrombotic therapy at baseline, 85%-90% were receiving antihypertensives, and about 85% were taking statins.

Longer-term follow-up should provide a better picture of the nonprocedural stroke risk, with patients asked annually about exactly what medications and doses they are taking, she said.

“We will have an enormous list of exactly what’s gone on and the intensity of that therapy, which is, of course, much more intense than when we carried out our first trial. But these were people in whom a procedure was thought to be necessary,” she noted.

When asked during the press conference which procedure she would choose, Dr. Halliday, a surgeon, observed that patient preference is important but that the nature of the lesion itself often determines the optimal choice.

“If you know the competence of the people doing it is equal, then the less invasive procedure – providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following for 10 years – is the more important,” she added.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Halliday reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA panel supports Vascepa expanded indication for CVD reduction

Icosapent ethyl, a highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid, received unanimous backing from a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel for a new indication for reducing cardiovascular event risk.

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) received initial agency approval in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

The target patient population for this new, cardiovascular-event protection role will reflect some or all of the types of patients enrolled in REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. This study provided the bulk of the data considered by the FDA panel.

REDUCE-IT showed that, during a median of 4.9 years, patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (New Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

Icosapent ethyl “appeared effective and safe,” and would be a “useful, new, added agent for treating patients” like those enrolled in the trial, said Kenneth D. Burman, MD, professor and chief of endocrinology at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center and chair of the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee.

The advisory panel members appeared uniformly comfortable with recommending that the FDA add a cardiovascular disease indication based on the REDUCE-IT findings.

But while they agreed that icosapent ethyl should receive some type of indication for cardiovascular event reduction, the committee split over which patients the indication should include. Specifically, they diverged on the issue of primary prevention.

Some said that the patient enrollment that produced a positive result in REDUCE-IT should not be retrospectively subdivided, while others said that combining secondary- and primary-prevention patients in a single large trial inappropriately lumped together patients who would be better considered separately.

Committee members also expressed uncertainty over the appropriate triglyceride level to warrant treatment. The REDUCE-IT trial was designed to enroll patients with triglycerides of 135 mg/dL or greater, but several panel members suggested that, for labeling, the threshold should be at least 150 mg/dL, or even 200 mg/dL.

Safety was another aspect that generated a lot of panel discussion throughout their day-long discussion, with particular focus on a signal of a small but concerning increased rate of incident atrial fibrillation among patients who received icosapent ethyl, as well as a small but nearly significant increase in the rate of serious bleeds.

Further analyses presented during the meeting showed that an increased bleeding rate linked with icosapent ethyl was focused in patients who concurrently received one or more antiplatelet drugs or an anticoagulant.

However, panel members rejected the notion that these safety concerns warranted a boxed warning, agreeing that it could be managed with appropriate labeling information.

Clinician reaction

Clinicians who manage these types of patients viewed the prospect of an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl as an important advance.

The REDUCE-IT results by themselves “were convincing” for patients with established cardiovascular disease without need for a confirmatory trial, Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview. But he remained unconvinced about efficacy for primary-prevention patients, or even for secondary-prevention patients with a triglyceride level below 150 mg/dL.

“Icosapent ethyl will clearly be a mainstay for managing high-risk patients. It gives us another treatment option,” Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist and medical director and principal investigator of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif., said in an interview. “I do not see the atrial fibrillation or bleeding effects as reasons not to approve this drug. It should be a precaution. Overall, icosapent ethyl is one of the easier drugs for patients to take.”

Dr. Handelsman said it would be unethical to run a confirmatory trial and randomize patients to placebo. “Another trial makes no sense,” he said.

But the data from REDUCE-IT were “not as convincing” for primary-prevention patients, suggesting a need for caution about using icosapent ethyl for patients without established cardiovascular disease, Paul S. Jellinger, MD, an endocrinologist in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said in an interview.

Cost-effectiveness

An analysis of the cost-effectiveness of icosapent ethyl as used in REDUCE-IT showed that the drug fell into the rare category of being a “dominant” treatment, meaning that it both improved patient outcomes and reduced medical costs. William S. Weintraub, MD, will report findings from this analysis on Nov. 16, 2019, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

The analysis used a wholesale acquisition cost for a 1-day dosage of icosapent ethyl of $4.16, derived from a commercial source for prescription-drug pricing and actual hospitalization costs for the patients in the trial.

Based on the REDUCE-IT outcomes, treatment with icosapent ethyl was linked with a boost in quality-adjusted life-years that extrapolated to an average 0.26 increase during the full lifetime of REDUCE-IT participants, at a cost that averaged $1,284 less per treated patient over their lifetime, according to Dr. Weintraub, director of Outcomes Research at Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington.

Although the 0.26 lifetime increase in quality-adjusted life-years may sound modest, “in the cost-effectiveness world, 0.26 is actually significant,” Dr. Weintraub said. He also highlighted how unusual it is to find a patented drug that improves quality of life and longevity while also saving money.

“I know of no other on-patent, branded pharmaceutical that is dominant,” he said.

Off-patent pharmaceuticals, like statins, can be quite inexpensive and may also be dominant, he noted. Being dominant for cost-effectiveness means that icosapent ethyl “provides good value and is worth what we pay for it, well within social thresholds of willingness to pay,” Dr. Weintraub said.

REDUCE-IT was sponsored by Amarin, the company that markets icosapent ethyl (Vascepa). Dr. Burman has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Eisai, and IBSA. Dr. Eckel has received personal fees from Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi/Regeneron, as well as research funding from Endece, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and UniQure. Dr. Handelsman has been a consultant to and received research funding from Amarin and several other companies. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Amarin, Amgen, and Regeneron. Dr. Weintraub has received honoraria and research support from Amarin, and honoraria from AstraZeneca.

Icosapent ethyl, a highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid, received unanimous backing from a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel for a new indication for reducing cardiovascular event risk.

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) received initial agency approval in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

The target patient population for this new, cardiovascular-event protection role will reflect some or all of the types of patients enrolled in REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. This study provided the bulk of the data considered by the FDA panel.

REDUCE-IT showed that, during a median of 4.9 years, patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (New Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

Icosapent ethyl “appeared effective and safe,” and would be a “useful, new, added agent for treating patients” like those enrolled in the trial, said Kenneth D. Burman, MD, professor and chief of endocrinology at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center and chair of the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee.

The advisory panel members appeared uniformly comfortable with recommending that the FDA add a cardiovascular disease indication based on the REDUCE-IT findings.

But while they agreed that icosapent ethyl should receive some type of indication for cardiovascular event reduction, the committee split over which patients the indication should include. Specifically, they diverged on the issue of primary prevention.

Some said that the patient enrollment that produced a positive result in REDUCE-IT should not be retrospectively subdivided, while others said that combining secondary- and primary-prevention patients in a single large trial inappropriately lumped together patients who would be better considered separately.

Committee members also expressed uncertainty over the appropriate triglyceride level to warrant treatment. The REDUCE-IT trial was designed to enroll patients with triglycerides of 135 mg/dL or greater, but several panel members suggested that, for labeling, the threshold should be at least 150 mg/dL, or even 200 mg/dL.

Safety was another aspect that generated a lot of panel discussion throughout their day-long discussion, with particular focus on a signal of a small but concerning increased rate of incident atrial fibrillation among patients who received icosapent ethyl, as well as a small but nearly significant increase in the rate of serious bleeds.

Further analyses presented during the meeting showed that an increased bleeding rate linked with icosapent ethyl was focused in patients who concurrently received one or more antiplatelet drugs or an anticoagulant.

However, panel members rejected the notion that these safety concerns warranted a boxed warning, agreeing that it could be managed with appropriate labeling information.

Clinician reaction

Clinicians who manage these types of patients viewed the prospect of an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl as an important advance.

The REDUCE-IT results by themselves “were convincing” for patients with established cardiovascular disease without need for a confirmatory trial, Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview. But he remained unconvinced about efficacy for primary-prevention patients, or even for secondary-prevention patients with a triglyceride level below 150 mg/dL.

“Icosapent ethyl will clearly be a mainstay for managing high-risk patients. It gives us another treatment option,” Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist and medical director and principal investigator of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif., said in an interview. “I do not see the atrial fibrillation or bleeding effects as reasons not to approve this drug. It should be a precaution. Overall, icosapent ethyl is one of the easier drugs for patients to take.”

Dr. Handelsman said it would be unethical to run a confirmatory trial and randomize patients to placebo. “Another trial makes no sense,” he said.

But the data from REDUCE-IT were “not as convincing” for primary-prevention patients, suggesting a need for caution about using icosapent ethyl for patients without established cardiovascular disease, Paul S. Jellinger, MD, an endocrinologist in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said in an interview.

Cost-effectiveness

An analysis of the cost-effectiveness of icosapent ethyl as used in REDUCE-IT showed that the drug fell into the rare category of being a “dominant” treatment, meaning that it both improved patient outcomes and reduced medical costs. William S. Weintraub, MD, will report findings from this analysis on Nov. 16, 2019, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

The analysis used a wholesale acquisition cost for a 1-day dosage of icosapent ethyl of $4.16, derived from a commercial source for prescription-drug pricing and actual hospitalization costs for the patients in the trial.

Based on the REDUCE-IT outcomes, treatment with icosapent ethyl was linked with a boost in quality-adjusted life-years that extrapolated to an average 0.26 increase during the full lifetime of REDUCE-IT participants, at a cost that averaged $1,284 less per treated patient over their lifetime, according to Dr. Weintraub, director of Outcomes Research at Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington.

Although the 0.26 lifetime increase in quality-adjusted life-years may sound modest, “in the cost-effectiveness world, 0.26 is actually significant,” Dr. Weintraub said. He also highlighted how unusual it is to find a patented drug that improves quality of life and longevity while also saving money.

“I know of no other on-patent, branded pharmaceutical that is dominant,” he said.

Off-patent pharmaceuticals, like statins, can be quite inexpensive and may also be dominant, he noted. Being dominant for cost-effectiveness means that icosapent ethyl “provides good value and is worth what we pay for it, well within social thresholds of willingness to pay,” Dr. Weintraub said.

REDUCE-IT was sponsored by Amarin, the company that markets icosapent ethyl (Vascepa). Dr. Burman has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Eisai, and IBSA. Dr. Eckel has received personal fees from Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi/Regeneron, as well as research funding from Endece, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and UniQure. Dr. Handelsman has been a consultant to and received research funding from Amarin and several other companies. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Amarin, Amgen, and Regeneron. Dr. Weintraub has received honoraria and research support from Amarin, and honoraria from AstraZeneca.

Icosapent ethyl, a highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid, received unanimous backing from a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel for a new indication for reducing cardiovascular event risk.

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) received initial agency approval in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

The target patient population for this new, cardiovascular-event protection role will reflect some or all of the types of patients enrolled in REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. This study provided the bulk of the data considered by the FDA panel.

REDUCE-IT showed that, during a median of 4.9 years, patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (New Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

Icosapent ethyl “appeared effective and safe,” and would be a “useful, new, added agent for treating patients” like those enrolled in the trial, said Kenneth D. Burman, MD, professor and chief of endocrinology at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center and chair of the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee.

The advisory panel members appeared uniformly comfortable with recommending that the FDA add a cardiovascular disease indication based on the REDUCE-IT findings.

But while they agreed that icosapent ethyl should receive some type of indication for cardiovascular event reduction, the committee split over which patients the indication should include. Specifically, they diverged on the issue of primary prevention.

Some said that the patient enrollment that produced a positive result in REDUCE-IT should not be retrospectively subdivided, while others said that combining secondary- and primary-prevention patients in a single large trial inappropriately lumped together patients who would be better considered separately.

Committee members also expressed uncertainty over the appropriate triglyceride level to warrant treatment. The REDUCE-IT trial was designed to enroll patients with triglycerides of 135 mg/dL or greater, but several panel members suggested that, for labeling, the threshold should be at least 150 mg/dL, or even 200 mg/dL.

Safety was another aspect that generated a lot of panel discussion throughout their day-long discussion, with particular focus on a signal of a small but concerning increased rate of incident atrial fibrillation among patients who received icosapent ethyl, as well as a small but nearly significant increase in the rate of serious bleeds.

Further analyses presented during the meeting showed that an increased bleeding rate linked with icosapent ethyl was focused in patients who concurrently received one or more antiplatelet drugs or an anticoagulant.

However, panel members rejected the notion that these safety concerns warranted a boxed warning, agreeing that it could be managed with appropriate labeling information.

Clinician reaction

Clinicians who manage these types of patients viewed the prospect of an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl as an important advance.