User login

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

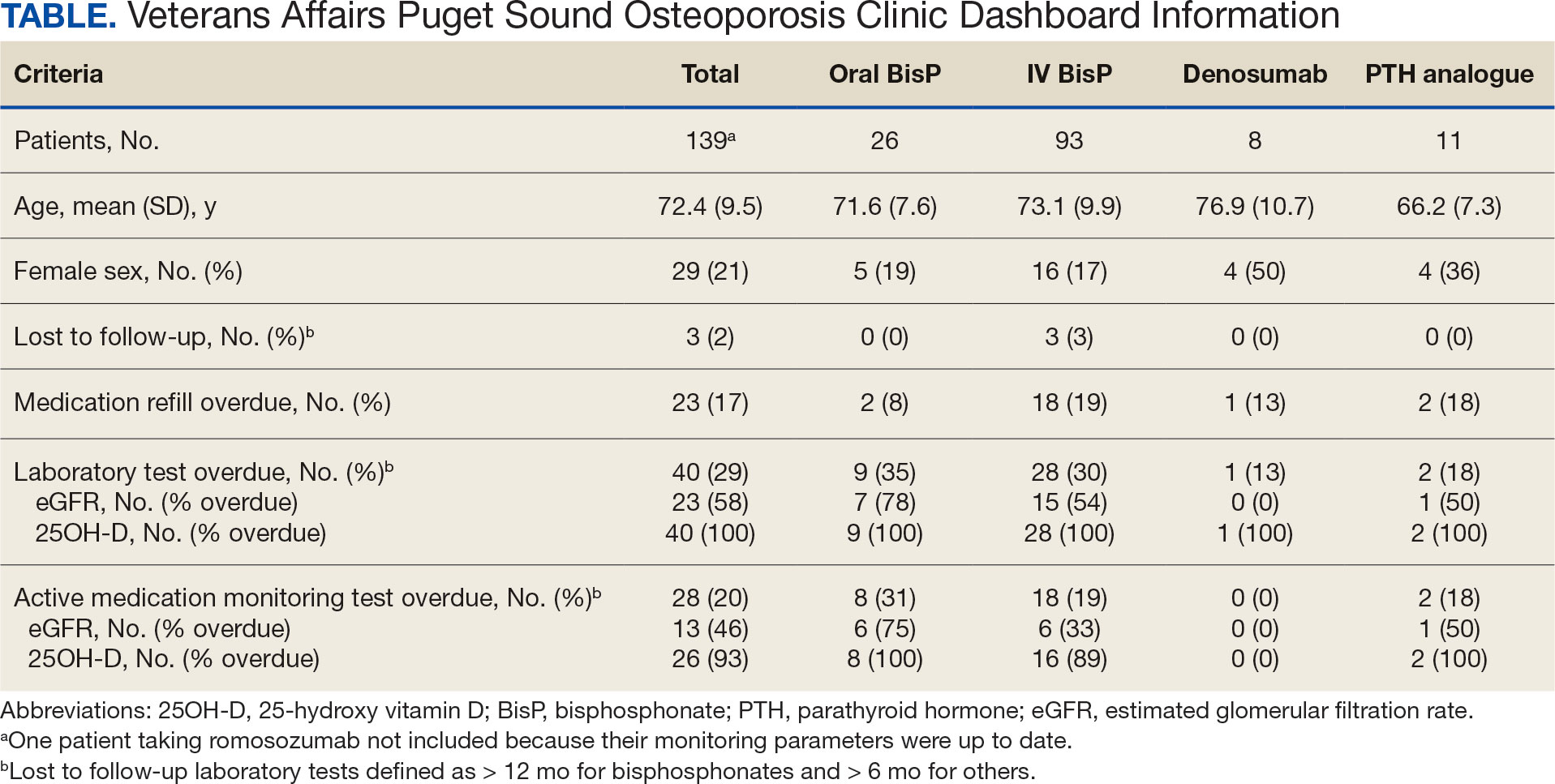

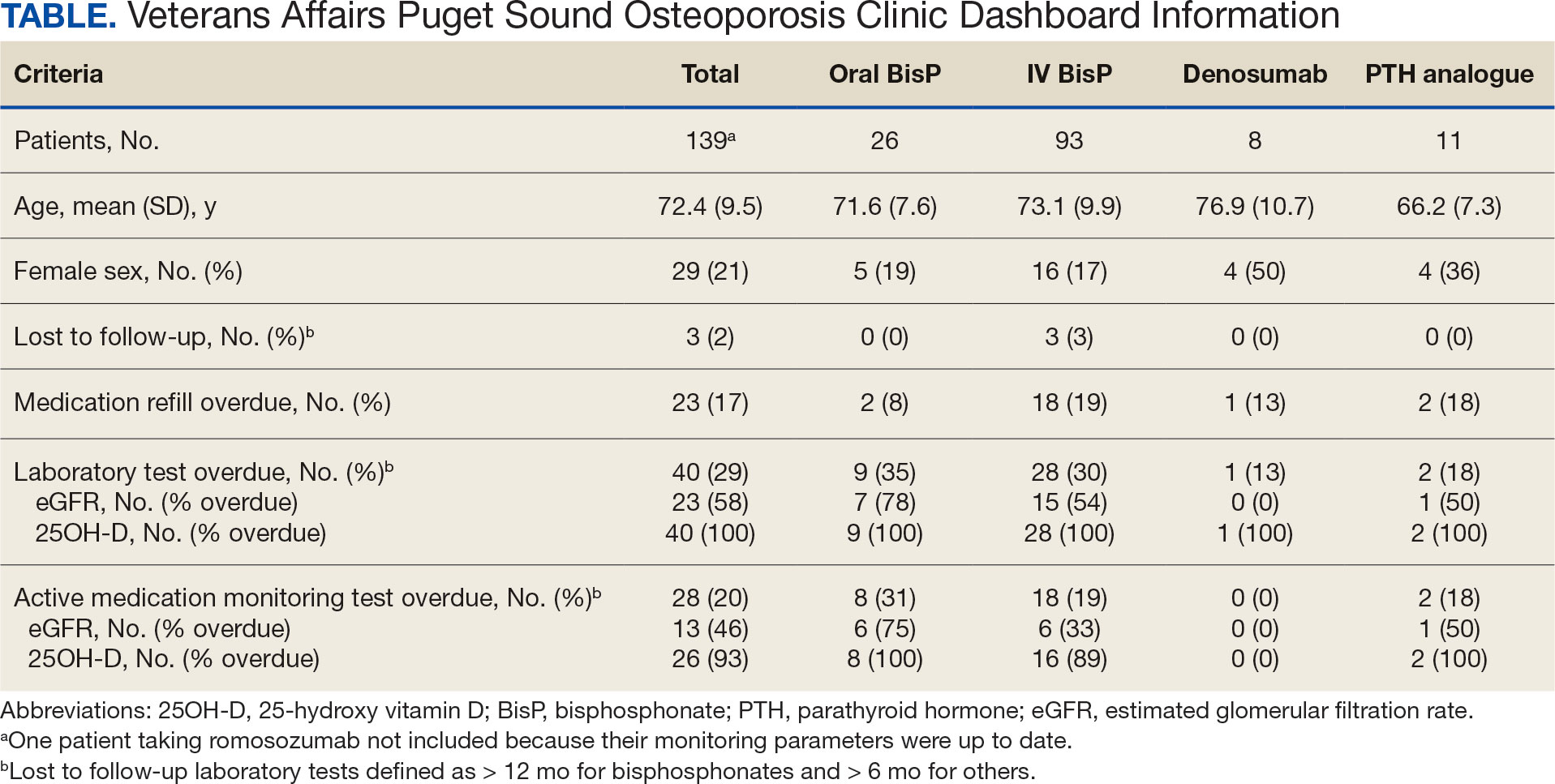

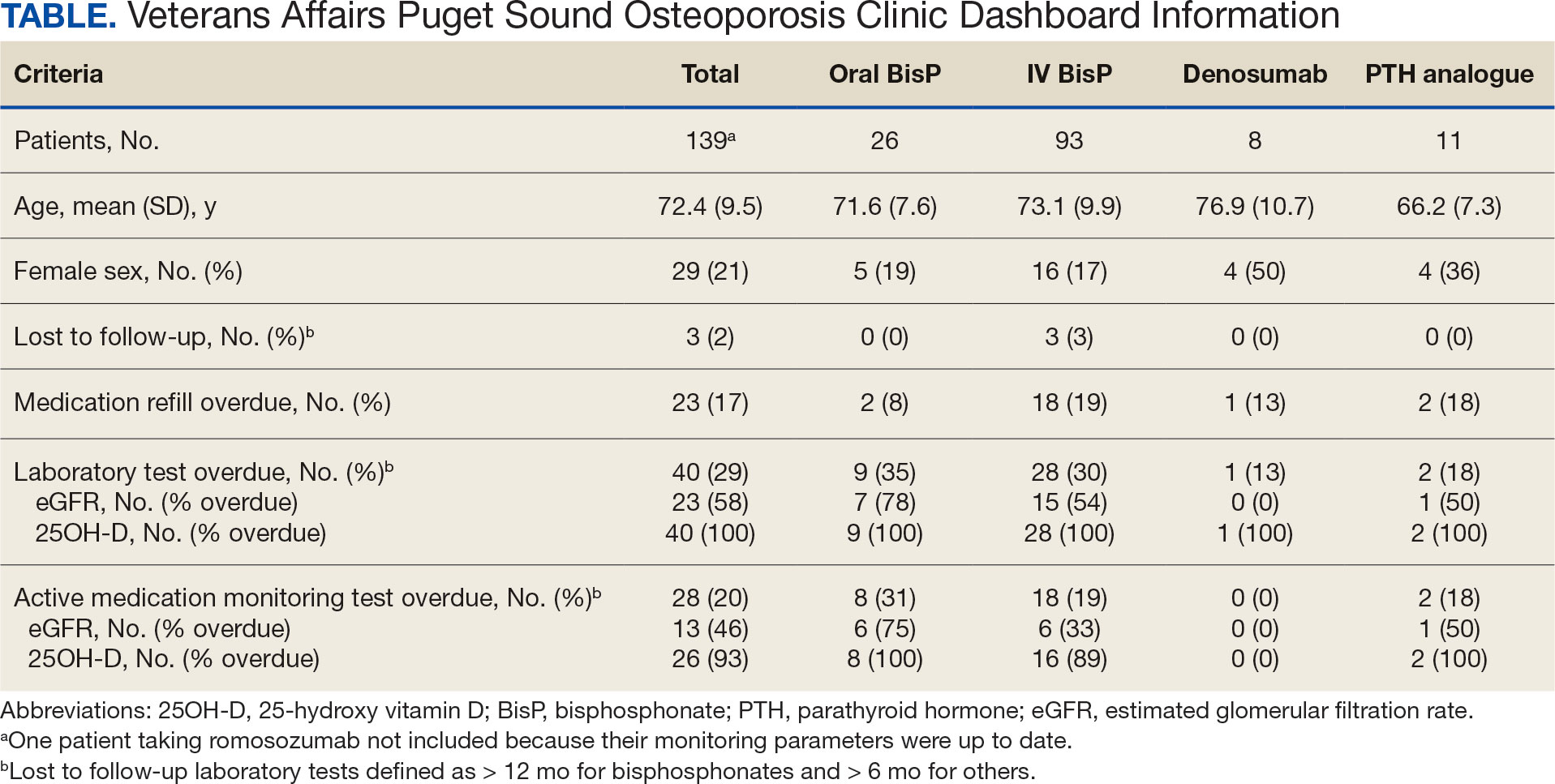

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Using AI to ID Osteoporosis: A Medico-Legal Minefield?

Could an artificial intelligence (AI)–driven tool that mines medical records for suspected cases of osteoporosis be so successful that it becomes a potential liability? Yes, according to Christopher White, PhD, executive director of Maridulu Budyari Gumal, the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research, and Enterprise, a research translation center in Liverpool, Australia.

In a thought-provoking presentation at the Endocrine Society’s AI in Healthcare Virtual Summit, White described the results after his fracture liaison team at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, Australia, tried to plug the “osteoporosis treatment gap” by mining medical records to identify patients with the disorder.

‘Be Careful What You Wish For’

White and colleagues developed a robust standalone database over 20 years that informed fracture risk among patients with osteoporosis in Sydney. The database included all relevant clinical information, as well as bone density measurements, on about 30,000 patients and could be interrogated for randomized controlled trial recruitment.

However, a “crisis” occurred around 2011, when the team received a recruitment request for the first head-to-head comparison of alendronate with romosozumab. “We had numerous postmenopausal women in the age range with the required bone density, but we hadn’t captured the severity of their vertebral fracture or how many they actually had,” White told the this news organization. For recruitment into the study, participants must have had at least two moderate or severe vertebral fractures or a proximal vertebral fracture that was sustained between 3 and 24 months before recruitment.

White turned to his hospital’s mainframe, which had coding data and time intervals for patients who were admitted with vertebral or hip fractures. He calculated how many patients who met the study criteria had been discharged and how many of those he thought he’d be able to capture through the mainframe. He was confident he would have enough, but he was wrong. He underrecruited and could not participate in the trial.

Determined not to wind up in a similar situation in the future, he investigated and found that other centers were struggling with similar problems. This led to a collaboration with four investigators who were using AI and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) coding to identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures. White, meanwhile, had developed a natural language processing tool called XRAIT that also identified patients at fracture risk. A study comparing the two electronic search programs, which screen medical records for fractures, found that both reliably identified patients who had had a fracture. White and his colleagues concluded that hybrid tools combining XRAIT and AES would likely improve the identification of patients with osteoporosis who would require follow-up or might participate in future trials.

Those patients were not being identified sooner for multiple reasons, White explained. Sometimes, the radiologist would report osteoporosis, but it wouldn’t get coded. Or, in the emergency department, a patient with a fracture would be treated and then sent home, and the possibility of osteoporosis wasn’t reported.

“As we went deeper and deeper with our tools into the medical record, we found more and more patients who hadn’t been coded or reported but who actually had osteoporosis,” White said. “It was incredibly prevalent.”

But the number of patients identified was more than the hospital could comfortably handle.

Ironically, he added, “To my relief and probably not to the benefit of the patients, there was a system upgrade of the radiology reporting system, which was incompatible with the natural language processing technology that I had installed. The AI was turned off at that point, but I had a look over the edge and into the mine pit.”

“The lesson learned,” White told this news organization, is “If you mine the medical record for unidentified patients before you know what to do with the output, you create a medico-legal minefield. You need to be careful what you wish for with technology, because it may actually come true.”

Grappling With the Treatment Gap

An (over)abundance of patients is likely contributing to the “osteoporosis treatment gap” that Australia’s fracture liaison services, which handle many of these patients, are grappling with. One recent meta-analysis showed that not all eligible patients are treated and that not all patients who are treated actually start treatment. Another study showed that only a minority of patients — anywhere between 20% and 40% — who start are still persisting at about 3 years, White said.

Various types of fracture liaison services exist, he noted. The model that has been shown to best promote adherence is the one requiring clinicians to “identify, educate [usually, the primary care physician], evaluate, start treatment, continue treatment, and follow-up at 12 months for to confirm that there is adherence.”

What’s happening now, he said, is that the technology is identifying a high number of vertebral crush fractures, and there’s no education or evaluation. “The radiologist just refers the patient to a primary care physician and hopes for the best. AI isn’t contributing to solving the treatment gap problem; it’s amplifying it. It’s ahead of the ability of organizations to accommodate the findings.”

Solutions, he said, would require support at the top of health systems and organizations, and funding to proceed; data surveys concentrating on vertical integration of the medical record to follow patients wherever they are — eg, hospital, primary care — in their health journeys; a workflow with synchronous diagnosis and treatment planning, delivery, monitoring, and payment; and clinical and community champions advocating and “leading the charge in health tech.”

Furthermore, he advised, organizations need to be “very, very careful with safety and security — that is, managing the digital risks.”

“Oscar Wilde said there are two tragedies in life: One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it,” White concluded. “In my career, we’ve moved on from not knowing how to treat osteoporosis to knowing how to treat it. And that is both an asset and a liability.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could an artificial intelligence (AI)–driven tool that mines medical records for suspected cases of osteoporosis be so successful that it becomes a potential liability? Yes, according to Christopher White, PhD, executive director of Maridulu Budyari Gumal, the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research, and Enterprise, a research translation center in Liverpool, Australia.

In a thought-provoking presentation at the Endocrine Society’s AI in Healthcare Virtual Summit, White described the results after his fracture liaison team at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, Australia, tried to plug the “osteoporosis treatment gap” by mining medical records to identify patients with the disorder.

‘Be Careful What You Wish For’

White and colleagues developed a robust standalone database over 20 years that informed fracture risk among patients with osteoporosis in Sydney. The database included all relevant clinical information, as well as bone density measurements, on about 30,000 patients and could be interrogated for randomized controlled trial recruitment.

However, a “crisis” occurred around 2011, when the team received a recruitment request for the first head-to-head comparison of alendronate with romosozumab. “We had numerous postmenopausal women in the age range with the required bone density, but we hadn’t captured the severity of their vertebral fracture or how many they actually had,” White told the this news organization. For recruitment into the study, participants must have had at least two moderate or severe vertebral fractures or a proximal vertebral fracture that was sustained between 3 and 24 months before recruitment.

White turned to his hospital’s mainframe, which had coding data and time intervals for patients who were admitted with vertebral or hip fractures. He calculated how many patients who met the study criteria had been discharged and how many of those he thought he’d be able to capture through the mainframe. He was confident he would have enough, but he was wrong. He underrecruited and could not participate in the trial.

Determined not to wind up in a similar situation in the future, he investigated and found that other centers were struggling with similar problems. This led to a collaboration with four investigators who were using AI and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) coding to identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures. White, meanwhile, had developed a natural language processing tool called XRAIT that also identified patients at fracture risk. A study comparing the two electronic search programs, which screen medical records for fractures, found that both reliably identified patients who had had a fracture. White and his colleagues concluded that hybrid tools combining XRAIT and AES would likely improve the identification of patients with osteoporosis who would require follow-up or might participate in future trials.

Those patients were not being identified sooner for multiple reasons, White explained. Sometimes, the radiologist would report osteoporosis, but it wouldn’t get coded. Or, in the emergency department, a patient with a fracture would be treated and then sent home, and the possibility of osteoporosis wasn’t reported.

“As we went deeper and deeper with our tools into the medical record, we found more and more patients who hadn’t been coded or reported but who actually had osteoporosis,” White said. “It was incredibly prevalent.”

But the number of patients identified was more than the hospital could comfortably handle.

Ironically, he added, “To my relief and probably not to the benefit of the patients, there was a system upgrade of the radiology reporting system, which was incompatible with the natural language processing technology that I had installed. The AI was turned off at that point, but I had a look over the edge and into the mine pit.”

“The lesson learned,” White told this news organization, is “If you mine the medical record for unidentified patients before you know what to do with the output, you create a medico-legal minefield. You need to be careful what you wish for with technology, because it may actually come true.”

Grappling With the Treatment Gap

An (over)abundance of patients is likely contributing to the “osteoporosis treatment gap” that Australia’s fracture liaison services, which handle many of these patients, are grappling with. One recent meta-analysis showed that not all eligible patients are treated and that not all patients who are treated actually start treatment. Another study showed that only a minority of patients — anywhere between 20% and 40% — who start are still persisting at about 3 years, White said.

Various types of fracture liaison services exist, he noted. The model that has been shown to best promote adherence is the one requiring clinicians to “identify, educate [usually, the primary care physician], evaluate, start treatment, continue treatment, and follow-up at 12 months for to confirm that there is adherence.”

What’s happening now, he said, is that the technology is identifying a high number of vertebral crush fractures, and there’s no education or evaluation. “The radiologist just refers the patient to a primary care physician and hopes for the best. AI isn’t contributing to solving the treatment gap problem; it’s amplifying it. It’s ahead of the ability of organizations to accommodate the findings.”

Solutions, he said, would require support at the top of health systems and organizations, and funding to proceed; data surveys concentrating on vertical integration of the medical record to follow patients wherever they are — eg, hospital, primary care — in their health journeys; a workflow with synchronous diagnosis and treatment planning, delivery, monitoring, and payment; and clinical and community champions advocating and “leading the charge in health tech.”

Furthermore, he advised, organizations need to be “very, very careful with safety and security — that is, managing the digital risks.”

“Oscar Wilde said there are two tragedies in life: One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it,” White concluded. “In my career, we’ve moved on from not knowing how to treat osteoporosis to knowing how to treat it. And that is both an asset and a liability.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could an artificial intelligence (AI)–driven tool that mines medical records for suspected cases of osteoporosis be so successful that it becomes a potential liability? Yes, according to Christopher White, PhD, executive director of Maridulu Budyari Gumal, the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research, and Enterprise, a research translation center in Liverpool, Australia.

In a thought-provoking presentation at the Endocrine Society’s AI in Healthcare Virtual Summit, White described the results after his fracture liaison team at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, Australia, tried to plug the “osteoporosis treatment gap” by mining medical records to identify patients with the disorder.

‘Be Careful What You Wish For’

White and colleagues developed a robust standalone database over 20 years that informed fracture risk among patients with osteoporosis in Sydney. The database included all relevant clinical information, as well as bone density measurements, on about 30,000 patients and could be interrogated for randomized controlled trial recruitment.

However, a “crisis” occurred around 2011, when the team received a recruitment request for the first head-to-head comparison of alendronate with romosozumab. “We had numerous postmenopausal women in the age range with the required bone density, but we hadn’t captured the severity of their vertebral fracture or how many they actually had,” White told the this news organization. For recruitment into the study, participants must have had at least two moderate or severe vertebral fractures or a proximal vertebral fracture that was sustained between 3 and 24 months before recruitment.

White turned to his hospital’s mainframe, which had coding data and time intervals for patients who were admitted with vertebral or hip fractures. He calculated how many patients who met the study criteria had been discharged and how many of those he thought he’d be able to capture through the mainframe. He was confident he would have enough, but he was wrong. He underrecruited and could not participate in the trial.

Determined not to wind up in a similar situation in the future, he investigated and found that other centers were struggling with similar problems. This led to a collaboration with four investigators who were using AI and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) coding to identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures. White, meanwhile, had developed a natural language processing tool called XRAIT that also identified patients at fracture risk. A study comparing the two electronic search programs, which screen medical records for fractures, found that both reliably identified patients who had had a fracture. White and his colleagues concluded that hybrid tools combining XRAIT and AES would likely improve the identification of patients with osteoporosis who would require follow-up or might participate in future trials.

Those patients were not being identified sooner for multiple reasons, White explained. Sometimes, the radiologist would report osteoporosis, but it wouldn’t get coded. Or, in the emergency department, a patient with a fracture would be treated and then sent home, and the possibility of osteoporosis wasn’t reported.

“As we went deeper and deeper with our tools into the medical record, we found more and more patients who hadn’t been coded or reported but who actually had osteoporosis,” White said. “It was incredibly prevalent.”

But the number of patients identified was more than the hospital could comfortably handle.

Ironically, he added, “To my relief and probably not to the benefit of the patients, there was a system upgrade of the radiology reporting system, which was incompatible with the natural language processing technology that I had installed. The AI was turned off at that point, but I had a look over the edge and into the mine pit.”

“The lesson learned,” White told this news organization, is “If you mine the medical record for unidentified patients before you know what to do with the output, you create a medico-legal minefield. You need to be careful what you wish for with technology, because it may actually come true.”

Grappling With the Treatment Gap

An (over)abundance of patients is likely contributing to the “osteoporosis treatment gap” that Australia’s fracture liaison services, which handle many of these patients, are grappling with. One recent meta-analysis showed that not all eligible patients are treated and that not all patients who are treated actually start treatment. Another study showed that only a minority of patients — anywhere between 20% and 40% — who start are still persisting at about 3 years, White said.

Various types of fracture liaison services exist, he noted. The model that has been shown to best promote adherence is the one requiring clinicians to “identify, educate [usually, the primary care physician], evaluate, start treatment, continue treatment, and follow-up at 12 months for to confirm that there is adherence.”

What’s happening now, he said, is that the technology is identifying a high number of vertebral crush fractures, and there’s no education or evaluation. “The radiologist just refers the patient to a primary care physician and hopes for the best. AI isn’t contributing to solving the treatment gap problem; it’s amplifying it. It’s ahead of the ability of organizations to accommodate the findings.”

Solutions, he said, would require support at the top of health systems and organizations, and funding to proceed; data surveys concentrating on vertical integration of the medical record to follow patients wherever they are — eg, hospital, primary care — in their health journeys; a workflow with synchronous diagnosis and treatment planning, delivery, monitoring, and payment; and clinical and community champions advocating and “leading the charge in health tech.”

Furthermore, he advised, organizations need to be “very, very careful with safety and security — that is, managing the digital risks.”

“Oscar Wilde said there are two tragedies in life: One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it,” White concluded. “In my career, we’ve moved on from not knowing how to treat osteoporosis to knowing how to treat it. And that is both an asset and a liability.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is Vitamin E Beneficial for Bone Health?

Vitamin E may be best known for boosting skin and eye health as well as immune function. In recent years, researchers have explored the potential benefits of vitamin E on bone loss, especially in women with menopause-related osteoporosis. While data are beginning to roll in from these studies, evidence supporting a positive impact of vitamin E on osteoporosis and hip fracture risk in perimenopausal women remains elusive.

For osteoporosis, the rationale for using vitamin E is based on its antioxidant activity, which can scavenge potentially damaging free radicals. Researchers have asked whether vitamin E can help maintain the integrity of bone matrix and stimulate bone formation while minimizing bone resorption, particularly in trabecular (spongy) bone, the bone compartment preferentially affected in perimenopausal bone loss.

Vitamin E mostly consists of two isomers: alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol. Alpha-tocopherol has higher antioxidant activity and is found in nuts, seeds, vegetable oils, green leafy vegetables, fortified cereals, and vitamin E supplements. Gamma-tocopherol is known for its superior anti-inflammatory properties and accounts for about 70% of the total vitamin E intake in a typical American diet, largely sourced from soybean and other vegetable oils.

Benefits and Risks in Bone Loss Studies

Perimenopausal bone loss is caused, to a great extent, by the decrease in sex hormones. Studies of vitamin E in ovariectomized rats have yielded mixed results. This animal model lacks sex hormones and has similar bone changes to those of postmenopausal women. Some animal studies have suggested a positive effect of vitamin E on bone while others have reported no effect.

Studies in humans also have produced conflicting reports of positive, neutral, and negative associations of vitamin E with bone health. For example, the Women’s Health Initiative examined the relationship between vitamin and mineral antioxidants and bone health in postmenopausal women and found no significant association between antioxidants and bone mineral density.

Another study examining data from children and adolescents enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database found an inverse association between alpha-tocopherol and lumbar spine bone density, suggesting a deleterious effect on bone. Inverse associations also have been reported in certain studies of postmenopausal women.

High doses of alpha-tocopherol have been linked to a risk for impaired bone health through a variety of mechanisms, such as interference with vitamin K metabolism; competitive binding for alpha-tocopherol transfer protein, inhibiting the entry of beneficial vitamin E isomers, including gamma-tocopherol; and pro-oxidant effects that harm bone. Thus, postmenopausal women taking vitamin E supplements primarily as high doses of alpha-tocopherol might be hindering their bone health.

Data for gamma-tocopherol are more promising. Some studies hypothesize that gamma-tocopherol might uncouple bone turnover, leading to increased bone formation without affecting bone resorption. Further, a randomized controlled study of mixed tocopherols (rather than alpha-tocopherol) vs placebo reported a protective effect of this preparation on bone outcomes by suppressing bone resorption. This raises the importance of considering the specific forms of vitamin E when evaluating its role in bone health.

Limitations of Current Studies

Researchers acknowledge several limitations in studies to date. For example, there are very few randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of vitamin E on bone health. Most studies are cross-sectional or observational, even when longitudinal. Cross-sectional and observational designs prevent us from establishing a causal relationship between vitamin E and bone endpoints.

Such designs also run the risk of additional confounders that may affect associations between vitamin E and bone, or the lack thereof. These could include both known and unknown confounders. Of note, gamma-tocopherol intake data were not available for certain NHANES studies.

Further, people often consume multiple nutrients and supplements, complicating the identification of specific nutrient-disease associations. Most human studies estimate tocopherol intake by dietary questionnaires or measure serum tocopherol levels, which reflect short-term dietary intake, while bone mineral density is probably influenced by long-term dietary patterns.

Too Soon to Prescribe Vitamin E for Bone Health

Some nutrition experts advocate for vitamin E supplements containing mixed tocopherols, specifically suggesting a ratio of 50-100 IU of gamma-tocopherol per 400 IU of D-alpha-tocopherol. Additional research is essential to confirm and further clarify the role of gamma-tocopherol in bone formation and resorption. In fact, it is also important to explore the influence of other compounds in the vitamin E family on skeletal health.

Until more data are available, we would recommend following the Institute of Medicine’s guidelines for the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of vitamin E. This is age dependent, ranging from 4 to 11 mg/d between the ages of 0 and 13 years, and 15 mg/d thereafter.

Overall, evidence of vitamin E’s impact on osteoporosis and hip fracture risk in perimenopausal women remains inconclusive. Although some observational and interventional studies suggest potential benefits, more interventional studies, particularly randomized controlled trials, are necessary to explore the risks and benefits of vitamin E supplementation and serum vitamin E levels on bone density and fracture risk more thoroughly.

Dr. Pani, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, UVA School of Medicine; Medical Director, Department of General Medicine, Same Day Care Clinic, both in Charlottesville, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Misra, Professor, Chair, Physician-in-Chief, Department of Pediatrics, University of Virginia, and UVA Health Children’s, Charlottesville, has disclosed being a key opinion leader for Lumos Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin E may be best known for boosting skin and eye health as well as immune function. In recent years, researchers have explored the potential benefits of vitamin E on bone loss, especially in women with menopause-related osteoporosis. While data are beginning to roll in from these studies, evidence supporting a positive impact of vitamin E on osteoporosis and hip fracture risk in perimenopausal women remains elusive.

For osteoporosis, the rationale for using vitamin E is based on its antioxidant activity, which can scavenge potentially damaging free radicals. Researchers have asked whether vitamin E can help maintain the integrity of bone matrix and stimulate bone formation while minimizing bone resorption, particularly in trabecular (spongy) bone, the bone compartment preferentially affected in perimenopausal bone loss.

Vitamin E mostly consists of two isomers: alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol. Alpha-tocopherol has higher antioxidant activity and is found in nuts, seeds, vegetable oils, green leafy vegetables, fortified cereals, and vitamin E supplements. Gamma-tocopherol is known for its superior anti-inflammatory properties and accounts for about 70% of the total vitamin E intake in a typical American diet, largely sourced from soybean and other vegetable oils.

Benefits and Risks in Bone Loss Studies

Perimenopausal bone loss is caused, to a great extent, by the decrease in sex hormones. Studies of vitamin E in ovariectomized rats have yielded mixed results. This animal model lacks sex hormones and has similar bone changes to those of postmenopausal women. Some animal studies have suggested a positive effect of vitamin E on bone while others have reported no effect.

Studies in humans also have produced conflicting reports of positive, neutral, and negative associations of vitamin E with bone health. For example, the Women’s Health Initiative examined the relationship between vitamin and mineral antioxidants and bone health in postmenopausal women and found no significant association between antioxidants and bone mineral density.

Another study examining data from children and adolescents enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database found an inverse association between alpha-tocopherol and lumbar spine bone density, suggesting a deleterious effect on bone. Inverse associations also have been reported in certain studies of postmenopausal women.

High doses of alpha-tocopherol have been linked to a risk for impaired bone health through a variety of mechanisms, such as interference with vitamin K metabolism; competitive binding for alpha-tocopherol transfer protein, inhibiting the entry of beneficial vitamin E isomers, including gamma-tocopherol; and pro-oxidant effects that harm bone. Thus, postmenopausal women taking vitamin E supplements primarily as high doses of alpha-tocopherol might be hindering their bone health.

Data for gamma-tocopherol are more promising. Some studies hypothesize that gamma-tocopherol might uncouple bone turnover, leading to increased bone formation without affecting bone resorption. Further, a randomized controlled study of mixed tocopherols (rather than alpha-tocopherol) vs placebo reported a protective effect of this preparation on bone outcomes by suppressing bone resorption. This raises the importance of considering the specific forms of vitamin E when evaluating its role in bone health.

Limitations of Current Studies

Researchers acknowledge several limitations in studies to date. For example, there are very few randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of vitamin E on bone health. Most studies are cross-sectional or observational, even when longitudinal. Cross-sectional and observational designs prevent us from establishing a causal relationship between vitamin E and bone endpoints.

Such designs also run the risk of additional confounders that may affect associations between vitamin E and bone, or the lack thereof. These could include both known and unknown confounders. Of note, gamma-tocopherol intake data were not available for certain NHANES studies.

Further, people often consume multiple nutrients and supplements, complicating the identification of specific nutrient-disease associations. Most human studies estimate tocopherol intake by dietary questionnaires or measure serum tocopherol levels, which reflect short-term dietary intake, while bone mineral density is probably influenced by long-term dietary patterns.

Too Soon to Prescribe Vitamin E for Bone Health

Some nutrition experts advocate for vitamin E supplements containing mixed tocopherols, specifically suggesting a ratio of 50-100 IU of gamma-tocopherol per 400 IU of D-alpha-tocopherol. Additional research is essential to confirm and further clarify the role of gamma-tocopherol in bone formation and resorption. In fact, it is also important to explore the influence of other compounds in the vitamin E family on skeletal health.

Until more data are available, we would recommend following the Institute of Medicine’s guidelines for the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of vitamin E. This is age dependent, ranging from 4 to 11 mg/d between the ages of 0 and 13 years, and 15 mg/d thereafter.

Overall, evidence of vitamin E’s impact on osteoporosis and hip fracture risk in perimenopausal women remains inconclusive. Although some observational and interventional studies suggest potential benefits, more interventional studies, particularly randomized controlled trials, are necessary to explore the risks and benefits of vitamin E supplementation and serum vitamin E levels on bone density and fracture risk more thoroughly.

Dr. Pani, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, UVA School of Medicine; Medical Director, Department of General Medicine, Same Day Care Clinic, both in Charlottesville, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Misra, Professor, Chair, Physician-in-Chief, Department of Pediatrics, University of Virginia, and UVA Health Children’s, Charlottesville, has disclosed being a key opinion leader for Lumos Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin E may be best known for boosting skin and eye health as well as immune function. In recent years, researchers have explored the potential benefits of vitamin E on bone loss, especially in women with menopause-related osteoporosis. While data are beginning to roll in from these studies, evidence supporting a positive impact of vitamin E on osteoporosis and hip fracture risk in perimenopausal women remains elusive.

For osteoporosis, the rationale for using vitamin E is based on its antioxidant activity, which can scavenge potentially damaging free radicals. Researchers have asked whether vitamin E can help maintain the integrity of bone matrix and stimulate bone formation while minimizing bone resorption, particularly in trabecular (spongy) bone, the bone compartment preferentially affected in perimenopausal bone loss.

Vitamin E mostly consists of two isomers: alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol. Alpha-tocopherol has higher antioxidant activity and is found in nuts, seeds, vegetable oils, green leafy vegetables, fortified cereals, and vitamin E supplements. Gamma-tocopherol is known for its superior anti-inflammatory properties and accounts for about 70% of the total vitamin E intake in a typical American diet, largely sourced from soybean and other vegetable oils.

Benefits and Risks in Bone Loss Studies

Perimenopausal bone loss is caused, to a great extent, by the decrease in sex hormones. Studies of vitamin E in ovariectomized rats have yielded mixed results. This animal model lacks sex hormones and has similar bone changes to those of postmenopausal women. Some animal studies have suggested a positive effect of vitamin E on bone while others have reported no effect.

Studies in humans also have produced conflicting reports of positive, neutral, and negative associations of vitamin E with bone health. For example, the Women’s Health Initiative examined the relationship between vitamin and mineral antioxidants and bone health in postmenopausal women and found no significant association between antioxidants and bone mineral density.

Another study examining data from children and adolescents enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database found an inverse association between alpha-tocopherol and lumbar spine bone density, suggesting a deleterious effect on bone. Inverse associations also have been reported in certain studies of postmenopausal women.

High doses of alpha-tocopherol have been linked to a risk for impaired bone health through a variety of mechanisms, such as interference with vitamin K metabolism; competitive binding for alpha-tocopherol transfer protein, inhibiting the entry of beneficial vitamin E isomers, including gamma-tocopherol; and pro-oxidant effects that harm bone. Thus, postmenopausal women taking vitamin E supplements primarily as high doses of alpha-tocopherol might be hindering their bone health.

Data for gamma-tocopherol are more promising. Some studies hypothesize that gamma-tocopherol might uncouple bone turnover, leading to increased bone formation without affecting bone resorption. Further, a randomized controlled study of mixed tocopherols (rather than alpha-tocopherol) vs placebo reported a protective effect of this preparation on bone outcomes by suppressing bone resorption. This raises the importance of considering the specific forms of vitamin E when evaluating its role in bone health.

Limitations of Current Studies

Researchers acknowledge several limitations in studies to date. For example, there are very few randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of vitamin E on bone health. Most studies are cross-sectional or observational, even when longitudinal. Cross-sectional and observational designs prevent us from establishing a causal relationship between vitamin E and bone endpoints.

Such designs also run the risk of additional confounders that may affect associations between vitamin E and bone, or the lack thereof. These could include both known and unknown confounders. Of note, gamma-tocopherol intake data were not available for certain NHANES studies.