User login

PACIFIC: Durvalumab extends PFS in stage 3 NSCLC

MADRID – For patients with locally advanced, unresectable non-small cell lung cancer, consolidation therapy with the anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor durvalumab after chemoradiation was associated with significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo, results of an interim analysis of the phase 3 PACIFIC trial showed.

Among 713 patients with stage III NSCLC treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy, the median PFS from randomization was 16.8 months for patients assigned to durvalumab compared with 5.6 months for patients assigned to placebo, reported Luis Paz-Ares, MD, from the University of Madrid, Spain.

“Overall, we think durvalumab is a promising option for patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiation,” he said at a briefing at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress.

Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with NSCLC have locally advanced disease at the time of presentation. Patients with unresectable disease and good performance status are treated with chemoradiotheraoy consisting of a platinum doublet with concurrent radiation, but median PFS in these patients is generally short, on the order of 8 months. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is 15%, he said.

Given the lack of major advances in the care of patients with stage 3 disease, investigators have been looking to newer therapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors to see whether they could improve outcomes.

PACIFIC is a phase 3 trial in which patients with stage III NSCLC who did not have disease progression after a minimum of two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive intravenous durvalumab 10 mg/kg or placebo every 2 weeks for up to 12 months. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and smoking history.

Dr. Paz-Ares presented PFS results from the interim analysis, planned when about 367 events had occurred. Data on the co-primary endpoint of OS were not mature at the time of the data cutoff.

Median PFS from randomization according to blinded independent central review for 476 patients treated with durvalumab was 16.8 months, compared with 5.6 months for 237 patients who received the placebo. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio (HR) of 0.52 (P less than .0001).

The respective PFS rates for durvalumab and placebo, were 59.9% vs. 35.3% at 12 months, and 44.2% vs. 27% at 18 months.

Among 443 patients on durvalumab and 213 on placebo who were evaluable for objective responses (OR), the respective OR rates were 28.4% vs. 16.

There were 6 complete responses (CR), 120 partial responses (PR), and 233 cases of stable disease in the durvalumab arm, compared with one CR, 33 PR, and 119 cases of stable disease in the placebo arm. In the durvalumab arm, 73 patients (16.5%) had progressive disease, compared with 59 patients (27.7%) in the placebo arm.

The median duration of response was not reached in the durvalumab arm, compared with 13.8 months in the placebo arm.

The PD-L1 inhibitor was also associated with a lower incidence of any new lesion among the intention-to-treat population (20.4% vs. 32.1%).

Grade 3 or 4 toxicities from any cause were slightly higher with durvalumab, at 29.9% vs. 26.1%. Events leading to discontinuation were also higher with the active drug, at 15.4% vs. 9.8% for placebo.

There were 21 deaths (4.4%) of patients treated with durvalumab, and 13 deaths (5.6%) of patients treated with placebo.

“In my opinion, this is a very well-designed study, and the results are very promising,” commented Enriqueta Felip, MD, who was not involved in the PACIFIC trial.

“We need to wait for the overall survival results, but in my opinion this is a very valuable trial in a group of patients [for whom] we need new strategies,” she said.

Dr. Felip was invited to the briefing as an independent commentator.

Results of the interim analysis of the PACIFIC trial were also published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The PACIFIC trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Paz-Ares has received consultancy fees from the company. Dr. Felip disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies not including AstraZeneca.

MADRID – For patients with locally advanced, unresectable non-small cell lung cancer, consolidation therapy with the anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor durvalumab after chemoradiation was associated with significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo, results of an interim analysis of the phase 3 PACIFIC trial showed.

Among 713 patients with stage III NSCLC treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy, the median PFS from randomization was 16.8 months for patients assigned to durvalumab compared with 5.6 months for patients assigned to placebo, reported Luis Paz-Ares, MD, from the University of Madrid, Spain.

“Overall, we think durvalumab is a promising option for patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiation,” he said at a briefing at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress.

Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with NSCLC have locally advanced disease at the time of presentation. Patients with unresectable disease and good performance status are treated with chemoradiotheraoy consisting of a platinum doublet with concurrent radiation, but median PFS in these patients is generally short, on the order of 8 months. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is 15%, he said.

Given the lack of major advances in the care of patients with stage 3 disease, investigators have been looking to newer therapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors to see whether they could improve outcomes.

PACIFIC is a phase 3 trial in which patients with stage III NSCLC who did not have disease progression after a minimum of two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive intravenous durvalumab 10 mg/kg or placebo every 2 weeks for up to 12 months. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and smoking history.

Dr. Paz-Ares presented PFS results from the interim analysis, planned when about 367 events had occurred. Data on the co-primary endpoint of OS were not mature at the time of the data cutoff.

Median PFS from randomization according to blinded independent central review for 476 patients treated with durvalumab was 16.8 months, compared with 5.6 months for 237 patients who received the placebo. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio (HR) of 0.52 (P less than .0001).

The respective PFS rates for durvalumab and placebo, were 59.9% vs. 35.3% at 12 months, and 44.2% vs. 27% at 18 months.

Among 443 patients on durvalumab and 213 on placebo who were evaluable for objective responses (OR), the respective OR rates were 28.4% vs. 16.

There were 6 complete responses (CR), 120 partial responses (PR), and 233 cases of stable disease in the durvalumab arm, compared with one CR, 33 PR, and 119 cases of stable disease in the placebo arm. In the durvalumab arm, 73 patients (16.5%) had progressive disease, compared with 59 patients (27.7%) in the placebo arm.

The median duration of response was not reached in the durvalumab arm, compared with 13.8 months in the placebo arm.

The PD-L1 inhibitor was also associated with a lower incidence of any new lesion among the intention-to-treat population (20.4% vs. 32.1%).

Grade 3 or 4 toxicities from any cause were slightly higher with durvalumab, at 29.9% vs. 26.1%. Events leading to discontinuation were also higher with the active drug, at 15.4% vs. 9.8% for placebo.

There were 21 deaths (4.4%) of patients treated with durvalumab, and 13 deaths (5.6%) of patients treated with placebo.

“In my opinion, this is a very well-designed study, and the results are very promising,” commented Enriqueta Felip, MD, who was not involved in the PACIFIC trial.

“We need to wait for the overall survival results, but in my opinion this is a very valuable trial in a group of patients [for whom] we need new strategies,” she said.

Dr. Felip was invited to the briefing as an independent commentator.

Results of the interim analysis of the PACIFIC trial were also published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The PACIFIC trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Paz-Ares has received consultancy fees from the company. Dr. Felip disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies not including AstraZeneca.

MADRID – For patients with locally advanced, unresectable non-small cell lung cancer, consolidation therapy with the anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor durvalumab after chemoradiation was associated with significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo, results of an interim analysis of the phase 3 PACIFIC trial showed.

Among 713 patients with stage III NSCLC treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy, the median PFS from randomization was 16.8 months for patients assigned to durvalumab compared with 5.6 months for patients assigned to placebo, reported Luis Paz-Ares, MD, from the University of Madrid, Spain.

“Overall, we think durvalumab is a promising option for patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiation,” he said at a briefing at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress.

Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with NSCLC have locally advanced disease at the time of presentation. Patients with unresectable disease and good performance status are treated with chemoradiotheraoy consisting of a platinum doublet with concurrent radiation, but median PFS in these patients is generally short, on the order of 8 months. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is 15%, he said.

Given the lack of major advances in the care of patients with stage 3 disease, investigators have been looking to newer therapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors to see whether they could improve outcomes.

PACIFIC is a phase 3 trial in which patients with stage III NSCLC who did not have disease progression after a minimum of two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive intravenous durvalumab 10 mg/kg or placebo every 2 weeks for up to 12 months. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and smoking history.

Dr. Paz-Ares presented PFS results from the interim analysis, planned when about 367 events had occurred. Data on the co-primary endpoint of OS were not mature at the time of the data cutoff.

Median PFS from randomization according to blinded independent central review for 476 patients treated with durvalumab was 16.8 months, compared with 5.6 months for 237 patients who received the placebo. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio (HR) of 0.52 (P less than .0001).

The respective PFS rates for durvalumab and placebo, were 59.9% vs. 35.3% at 12 months, and 44.2% vs. 27% at 18 months.

Among 443 patients on durvalumab and 213 on placebo who were evaluable for objective responses (OR), the respective OR rates were 28.4% vs. 16.

There were 6 complete responses (CR), 120 partial responses (PR), and 233 cases of stable disease in the durvalumab arm, compared with one CR, 33 PR, and 119 cases of stable disease in the placebo arm. In the durvalumab arm, 73 patients (16.5%) had progressive disease, compared with 59 patients (27.7%) in the placebo arm.

The median duration of response was not reached in the durvalumab arm, compared with 13.8 months in the placebo arm.

The PD-L1 inhibitor was also associated with a lower incidence of any new lesion among the intention-to-treat population (20.4% vs. 32.1%).

Grade 3 or 4 toxicities from any cause were slightly higher with durvalumab, at 29.9% vs. 26.1%. Events leading to discontinuation were also higher with the active drug, at 15.4% vs. 9.8% for placebo.

There were 21 deaths (4.4%) of patients treated with durvalumab, and 13 deaths (5.6%) of patients treated with placebo.

“In my opinion, this is a very well-designed study, and the results are very promising,” commented Enriqueta Felip, MD, who was not involved in the PACIFIC trial.

“We need to wait for the overall survival results, but in my opinion this is a very valuable trial in a group of patients [for whom] we need new strategies,” she said.

Dr. Felip was invited to the briefing as an independent commentator.

Results of the interim analysis of the PACIFIC trial were also published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The PACIFIC trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Paz-Ares has received consultancy fees from the company. Dr. Felip disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies not including AstraZeneca.

AT ESMO 2017

Shinal v. Toms: It’s Now Harder to Get Informed Consent

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.

The trial court instructed the jury with regard to Dr. Toms’ duty to obtain informed consent from Mrs. Shinal as follows: “[I]n considering whether [Dr. Toms] provided consent to [Mrs. Shinal], you may consider any relevant information you find was communicated to [Mrs. Shinal] by any qualified person acting as an assistant to [Dr. Toms].”

On April 21, 2014, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Dr. Toms.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, which affirmed the trial court’s judgment. It rejected the Shinals’ argument that the trial court’s informed consent charge, which permitted the jury to consider information provided by Dr. Toms’ physician assistant to Mrs. Shinal, was erroneous and prejudicial. The Superior Court relied upon two of its prior cases to opine that a qualified professional acting under the attending doctor’s supervision may convey information communicated to a patient for purposes of obtaining informed consent.

The trial court initially instructed the jury that, in assessing whether Dr. Toms obtained Mrs. Shinal’s informed consent, it could consider relevant information communicated by “any qualified person acting as an assistant” to Dr. Toms. The defendant doctor argued that while it is the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent, the physician is not required to supply all of the information personally. It is the information conveyed, rather than the person conveying it that determines informed consent. Dr. Toms cited several older Pennsylvania Superior Court cases, which permitted a physician to fulfill through an intermediary the duty to provide sufficient information to obtain a patient’s informed consent.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which led to a reversal. In a 4-3 decision, the court disagreed, citing their ruling in the 2002 case of Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center,2 where they held that the duty to obtain informed consent could not be imputed to a hospital. In Valles, the court held that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent is a nondelegable duty owed by the physician conducting the surgery or treatment, because obtaining informed consent results directly from the duty of disclosure, which lies solely with the physician, and a hospital therefore cannot be liable for a physician’s failure to obtain informed consent.

Reasoning by extension, the court accordingly ruled that a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patient’s informed consent. It declared: “Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient, and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.”

The court also held that “a physician cannot rely upon a subordinate to disclose the information required to obtain informed consent. Without direct dialogue and a two-way exchange between the physician and patient, the physician cannot be confident that the patient comprehends the risks, benefits, likelihood of success, and alternatives. ... Informed consent is a product of the physician-patient relationship.

"The patient is in the vulnerable position of entrusting his or her care and well being to the physician based upon the physician’s education, training, and expertise," the court added. "It is incumbent upon the physician to cultivate a relationship with the patient and to familiarize himself or herself with the patient’s understanding and expectations. Were the law to permit physicians to delegate the provision of critical information to staff, it would undermine patient autonomy and bodily integrity by depriving the patient of the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with his or her chosen health care provider. A regime that would countenance delegation of the informed consent process would undermine the primacy of the physician-patient relationship. Only by personally satisfying the duty of disclosure may the physician ensure that consent truly is informed.”

The facts of the case appear straightforward, and its legal conclusion clear. Whether one agrees with the court’s decision is, however, another matter. The American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society (PAMED) had submitted an amicus brief supporting Dr. Toms’ position, arguing that he had fulfilled his obligations under Pennsylvania’s Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act, as well as common law established in previous Pennsylvania court rulings. The final appellate decision therefore came as a big disappointment. The PAMED website notes that the decision “could have significant ramifications for Pennsylvania physicians” in that they can “seemingly no longer rely on the aid of their qualified staff in the informed consent process.”3

The urgent question now is whether other jurisdictions will adopt this Pennsylvania rule that drastically changes the way doctors obtain informed consent from their patients.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Shinal v. Toms, J-106-2016, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Decided: June 20, 2017.

2. Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 805 A.2d (PA, 2002).

3. Informed-consent ruling may have “far-reaching, negative impact.” AMA Wire, Aug 8, 2017.

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.

The trial court instructed the jury with regard to Dr. Toms’ duty to obtain informed consent from Mrs. Shinal as follows: “[I]n considering whether [Dr. Toms] provided consent to [Mrs. Shinal], you may consider any relevant information you find was communicated to [Mrs. Shinal] by any qualified person acting as an assistant to [Dr. Toms].”

On April 21, 2014, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Dr. Toms.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, which affirmed the trial court’s judgment. It rejected the Shinals’ argument that the trial court’s informed consent charge, which permitted the jury to consider information provided by Dr. Toms’ physician assistant to Mrs. Shinal, was erroneous and prejudicial. The Superior Court relied upon two of its prior cases to opine that a qualified professional acting under the attending doctor’s supervision may convey information communicated to a patient for purposes of obtaining informed consent.

The trial court initially instructed the jury that, in assessing whether Dr. Toms obtained Mrs. Shinal’s informed consent, it could consider relevant information communicated by “any qualified person acting as an assistant” to Dr. Toms. The defendant doctor argued that while it is the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent, the physician is not required to supply all of the information personally. It is the information conveyed, rather than the person conveying it that determines informed consent. Dr. Toms cited several older Pennsylvania Superior Court cases, which permitted a physician to fulfill through an intermediary the duty to provide sufficient information to obtain a patient’s informed consent.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which led to a reversal. In a 4-3 decision, the court disagreed, citing their ruling in the 2002 case of Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center,2 where they held that the duty to obtain informed consent could not be imputed to a hospital. In Valles, the court held that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent is a nondelegable duty owed by the physician conducting the surgery or treatment, because obtaining informed consent results directly from the duty of disclosure, which lies solely with the physician, and a hospital therefore cannot be liable for a physician’s failure to obtain informed consent.

Reasoning by extension, the court accordingly ruled that a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patient’s informed consent. It declared: “Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient, and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.”

The court also held that “a physician cannot rely upon a subordinate to disclose the information required to obtain informed consent. Without direct dialogue and a two-way exchange between the physician and patient, the physician cannot be confident that the patient comprehends the risks, benefits, likelihood of success, and alternatives. ... Informed consent is a product of the physician-patient relationship.

"The patient is in the vulnerable position of entrusting his or her care and well being to the physician based upon the physician’s education, training, and expertise," the court added. "It is incumbent upon the physician to cultivate a relationship with the patient and to familiarize himself or herself with the patient’s understanding and expectations. Were the law to permit physicians to delegate the provision of critical information to staff, it would undermine patient autonomy and bodily integrity by depriving the patient of the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with his or her chosen health care provider. A regime that would countenance delegation of the informed consent process would undermine the primacy of the physician-patient relationship. Only by personally satisfying the duty of disclosure may the physician ensure that consent truly is informed.”

The facts of the case appear straightforward, and its legal conclusion clear. Whether one agrees with the court’s decision is, however, another matter. The American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society (PAMED) had submitted an amicus brief supporting Dr. Toms’ position, arguing that he had fulfilled his obligations under Pennsylvania’s Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act, as well as common law established in previous Pennsylvania court rulings. The final appellate decision therefore came as a big disappointment. The PAMED website notes that the decision “could have significant ramifications for Pennsylvania physicians” in that they can “seemingly no longer rely on the aid of their qualified staff in the informed consent process.”3

The urgent question now is whether other jurisdictions will adopt this Pennsylvania rule that drastically changes the way doctors obtain informed consent from their patients.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Shinal v. Toms, J-106-2016, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Decided: June 20, 2017.

2. Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 805 A.2d (PA, 2002).

3. Informed-consent ruling may have “far-reaching, negative impact.” AMA Wire, Aug 8, 2017.

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.

The trial court instructed the jury with regard to Dr. Toms’ duty to obtain informed consent from Mrs. Shinal as follows: “[I]n considering whether [Dr. Toms] provided consent to [Mrs. Shinal], you may consider any relevant information you find was communicated to [Mrs. Shinal] by any qualified person acting as an assistant to [Dr. Toms].”

On April 21, 2014, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Dr. Toms.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, which affirmed the trial court’s judgment. It rejected the Shinals’ argument that the trial court’s informed consent charge, which permitted the jury to consider information provided by Dr. Toms’ physician assistant to Mrs. Shinal, was erroneous and prejudicial. The Superior Court relied upon two of its prior cases to opine that a qualified professional acting under the attending doctor’s supervision may convey information communicated to a patient for purposes of obtaining informed consent.

The trial court initially instructed the jury that, in assessing whether Dr. Toms obtained Mrs. Shinal’s informed consent, it could consider relevant information communicated by “any qualified person acting as an assistant” to Dr. Toms. The defendant doctor argued that while it is the physician’s duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent, the physician is not required to supply all of the information personally. It is the information conveyed, rather than the person conveying it that determines informed consent. Dr. Toms cited several older Pennsylvania Superior Court cases, which permitted a physician to fulfill through an intermediary the duty to provide sufficient information to obtain a patient’s informed consent.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which led to a reversal. In a 4-3 decision, the court disagreed, citing their ruling in the 2002 case of Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center,2 where they held that the duty to obtain informed consent could not be imputed to a hospital. In Valles, the court held that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent is a nondelegable duty owed by the physician conducting the surgery or treatment, because obtaining informed consent results directly from the duty of disclosure, which lies solely with the physician, and a hospital therefore cannot be liable for a physician’s failure to obtain informed consent.

Reasoning by extension, the court accordingly ruled that a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patient’s informed consent. It declared: “Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient, and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.”

The court also held that “a physician cannot rely upon a subordinate to disclose the information required to obtain informed consent. Without direct dialogue and a two-way exchange between the physician and patient, the physician cannot be confident that the patient comprehends the risks, benefits, likelihood of success, and alternatives. ... Informed consent is a product of the physician-patient relationship.

"The patient is in the vulnerable position of entrusting his or her care and well being to the physician based upon the physician’s education, training, and expertise," the court added. "It is incumbent upon the physician to cultivate a relationship with the patient and to familiarize himself or herself with the patient’s understanding and expectations. Were the law to permit physicians to delegate the provision of critical information to staff, it would undermine patient autonomy and bodily integrity by depriving the patient of the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with his or her chosen health care provider. A regime that would countenance delegation of the informed consent process would undermine the primacy of the physician-patient relationship. Only by personally satisfying the duty of disclosure may the physician ensure that consent truly is informed.”

The facts of the case appear straightforward, and its legal conclusion clear. Whether one agrees with the court’s decision is, however, another matter. The American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society (PAMED) had submitted an amicus brief supporting Dr. Toms’ position, arguing that he had fulfilled his obligations under Pennsylvania’s Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act, as well as common law established in previous Pennsylvania court rulings. The final appellate decision therefore came as a big disappointment. The PAMED website notes that the decision “could have significant ramifications for Pennsylvania physicians” in that they can “seemingly no longer rely on the aid of their qualified staff in the informed consent process.”3

The urgent question now is whether other jurisdictions will adopt this Pennsylvania rule that drastically changes the way doctors obtain informed consent from their patients.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Shinal v. Toms, J-106-2016, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Decided: June 20, 2017.

2. Valles v. Albert Einstein Medical Center, 805 A.2d (PA, 2002).

3. Informed-consent ruling may have “far-reaching, negative impact.” AMA Wire, Aug 8, 2017.

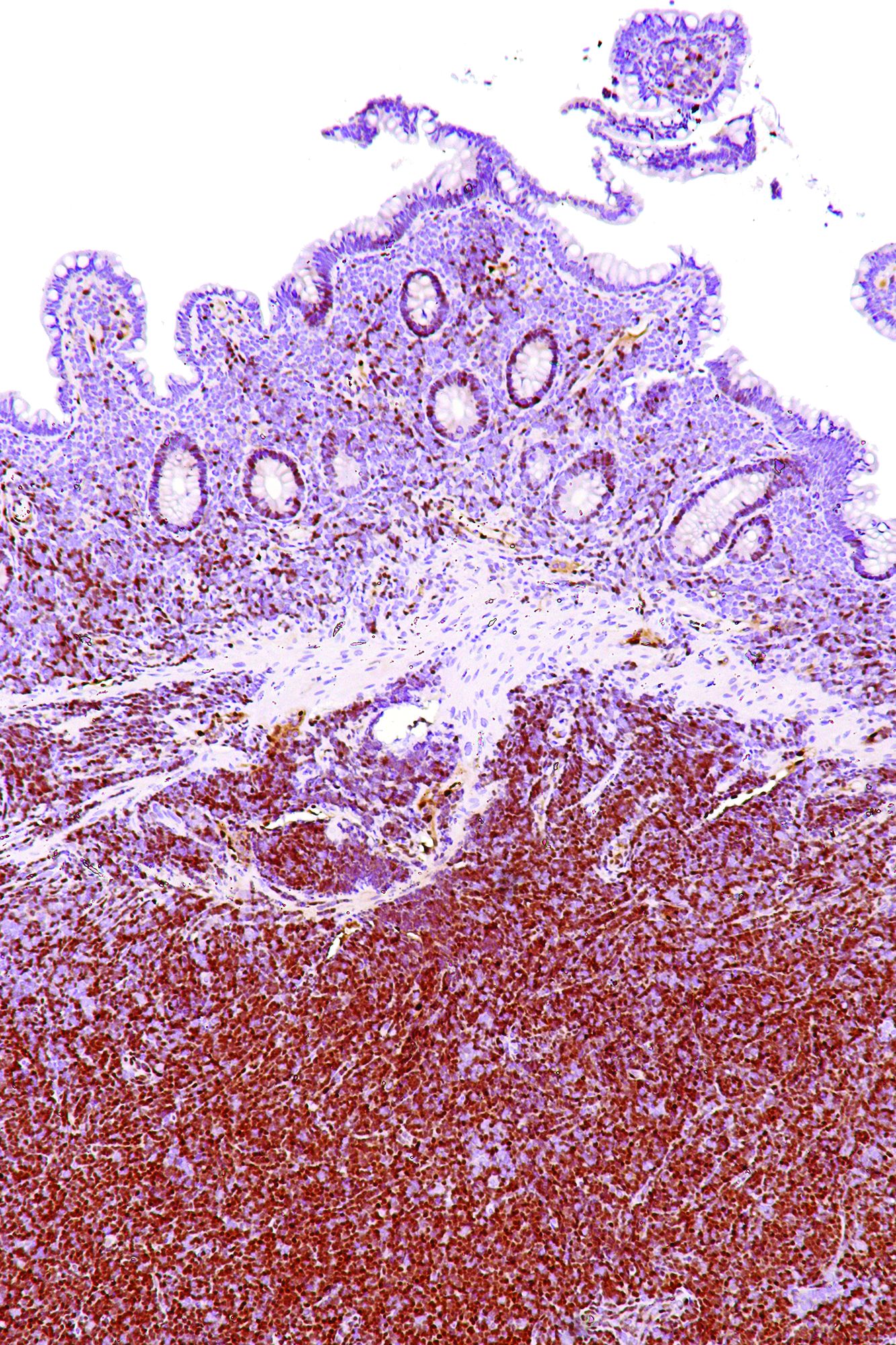

Plerixafor doesn’t overcome HPC failure in R-hyperCVAD for mantle cell lymphoma

A commonly-used intensive induction regimen was associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure in patients with mantle cell lymphoma, even when plerixafor rescue was attempted, based on a study by Amandeep Salhotra, MD, and his colleagues at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

Patients who received rituximab and hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (R-hyperCVAD) in the era after plerixafor came into use experienced significantly higher rates of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection failure than did patients receiving other induction regimens (17% vs. 4% failure rate, P = .04).

“Plerixafor does not overcome the negative impact of R-hyperCVAD on PBSC mobilization, and caution is warranted in using R-hyperCVAD in patients with newly diagnosed MCL who are candidates for ASCT (autologous stem cell transplant),” wrote Dr. Salhotra and his colleagues.

The higher rate of hematopoietic progenitor cell collection failure for R-hyperCVAD patients could not be attributed to their age at time of mantle cell lymphoma diagnosis or to the amount of time between diagnosis and collection.

Treatment records for 181 consecutive mantle cell lymphoma patients were examined for a 10 year period in the retrospective single-site study. Plerixafor, a C-X-C chemokine receptor agonist that reduces hematopoietic progenitor cells’ ability to bind to bone marrow stroma, was introduced on August 16, 2009; a total of 71 patients were treated before this point, and 110 were treated afterward.

The R-hyperCVAD regimen was received by 34 pre-plerixafor patients (45%) and by 42 of the post-plerixafor era patients (55%). Other regimens were received by 37 (35%) and 68 (65%) of the pre- and post-plerixafor era patients, respectively.

Before plerixafor came into use, Dr. Salhotra, of City of Hope’s department of hematology and hematopoietic cell transplantation, and his coinvestigators saw no significant difference among their study population in the rates of PBSC collection failure between those receiving R-hyperCVAD (11%) and those receiving other regimens (12%). The findings were reported in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The study was conducted in the context of other recent work that showed higher rates of PBSC collection failure and fewer CD34+ cells collected with the use of an R-hyperCVAD conditioning regimen. The fact that PBSC mobilization rates were significantly lower in R-hyperCVAD patients post-plerixafor surprised the investigators, who had hypothesized that the use of plerixafor would overcome PBSC mobilization failures without regard to the conditioning regimen used.

“It may be worthwhile to consider using a more aggressive strategy for [hematopoetic progenitor cell] mobilization in patients who have received R-hyperCVAD chemotherapy upfront or as salvage for aggressive lymphomas,” the researchers wrote. This might include the use of plerixafor upfront when patients have low CD34 counts before apheresis.

The researchers plan to examine their data to see how the choice of induction regimen and plerixafor usage impact patient survival.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Amandeep Salhotra, et al. Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma patients is associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure despite plerixafor rescue. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.04.011

A commonly-used intensive induction regimen was associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure in patients with mantle cell lymphoma, even when plerixafor rescue was attempted, based on a study by Amandeep Salhotra, MD, and his colleagues at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

Patients who received rituximab and hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (R-hyperCVAD) in the era after plerixafor came into use experienced significantly higher rates of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection failure than did patients receiving other induction regimens (17% vs. 4% failure rate, P = .04).

“Plerixafor does not overcome the negative impact of R-hyperCVAD on PBSC mobilization, and caution is warranted in using R-hyperCVAD in patients with newly diagnosed MCL who are candidates for ASCT (autologous stem cell transplant),” wrote Dr. Salhotra and his colleagues.

The higher rate of hematopoietic progenitor cell collection failure for R-hyperCVAD patients could not be attributed to their age at time of mantle cell lymphoma diagnosis or to the amount of time between diagnosis and collection.

Treatment records for 181 consecutive mantle cell lymphoma patients were examined for a 10 year period in the retrospective single-site study. Plerixafor, a C-X-C chemokine receptor agonist that reduces hematopoietic progenitor cells’ ability to bind to bone marrow stroma, was introduced on August 16, 2009; a total of 71 patients were treated before this point, and 110 were treated afterward.

The R-hyperCVAD regimen was received by 34 pre-plerixafor patients (45%) and by 42 of the post-plerixafor era patients (55%). Other regimens were received by 37 (35%) and 68 (65%) of the pre- and post-plerixafor era patients, respectively.

Before plerixafor came into use, Dr. Salhotra, of City of Hope’s department of hematology and hematopoietic cell transplantation, and his coinvestigators saw no significant difference among their study population in the rates of PBSC collection failure between those receiving R-hyperCVAD (11%) and those receiving other regimens (12%). The findings were reported in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The study was conducted in the context of other recent work that showed higher rates of PBSC collection failure and fewer CD34+ cells collected with the use of an R-hyperCVAD conditioning regimen. The fact that PBSC mobilization rates were significantly lower in R-hyperCVAD patients post-plerixafor surprised the investigators, who had hypothesized that the use of plerixafor would overcome PBSC mobilization failures without regard to the conditioning regimen used.

“It may be worthwhile to consider using a more aggressive strategy for [hematopoetic progenitor cell] mobilization in patients who have received R-hyperCVAD chemotherapy upfront or as salvage for aggressive lymphomas,” the researchers wrote. This might include the use of plerixafor upfront when patients have low CD34 counts before apheresis.

The researchers plan to examine their data to see how the choice of induction regimen and plerixafor usage impact patient survival.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Amandeep Salhotra, et al. Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma patients is associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure despite plerixafor rescue. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.04.011

A commonly-used intensive induction regimen was associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure in patients with mantle cell lymphoma, even when plerixafor rescue was attempted, based on a study by Amandeep Salhotra, MD, and his colleagues at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

Patients who received rituximab and hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (R-hyperCVAD) in the era after plerixafor came into use experienced significantly higher rates of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection failure than did patients receiving other induction regimens (17% vs. 4% failure rate, P = .04).

“Plerixafor does not overcome the negative impact of R-hyperCVAD on PBSC mobilization, and caution is warranted in using R-hyperCVAD in patients with newly diagnosed MCL who are candidates for ASCT (autologous stem cell transplant),” wrote Dr. Salhotra and his colleagues.

The higher rate of hematopoietic progenitor cell collection failure for R-hyperCVAD patients could not be attributed to their age at time of mantle cell lymphoma diagnosis or to the amount of time between diagnosis and collection.

Treatment records for 181 consecutive mantle cell lymphoma patients were examined for a 10 year period in the retrospective single-site study. Plerixafor, a C-X-C chemokine receptor agonist that reduces hematopoietic progenitor cells’ ability to bind to bone marrow stroma, was introduced on August 16, 2009; a total of 71 patients were treated before this point, and 110 were treated afterward.

The R-hyperCVAD regimen was received by 34 pre-plerixafor patients (45%) and by 42 of the post-plerixafor era patients (55%). Other regimens were received by 37 (35%) and 68 (65%) of the pre- and post-plerixafor era patients, respectively.

Before plerixafor came into use, Dr. Salhotra, of City of Hope’s department of hematology and hematopoietic cell transplantation, and his coinvestigators saw no significant difference among their study population in the rates of PBSC collection failure between those receiving R-hyperCVAD (11%) and those receiving other regimens (12%). The findings were reported in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

The study was conducted in the context of other recent work that showed higher rates of PBSC collection failure and fewer CD34+ cells collected with the use of an R-hyperCVAD conditioning regimen. The fact that PBSC mobilization rates were significantly lower in R-hyperCVAD patients post-plerixafor surprised the investigators, who had hypothesized that the use of plerixafor would overcome PBSC mobilization failures without regard to the conditioning regimen used.

“It may be worthwhile to consider using a more aggressive strategy for [hematopoetic progenitor cell] mobilization in patients who have received R-hyperCVAD chemotherapy upfront or as salvage for aggressive lymphomas,” the researchers wrote. This might include the use of plerixafor upfront when patients have low CD34 counts before apheresis.

The researchers plan to examine their data to see how the choice of induction regimen and plerixafor usage impact patient survival.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Amandeep Salhotra, et al. Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma patients is associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure despite plerixafor rescue. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.04.011

FROM BIOLOGY OF BLOOD AND MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Key clinical point: R-hyperCVAD was associated with increased peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection failure in the post-plerixafor era.

Major finding: Patients receiving R-hyperCVAD in the post-plerixafor era had a 17% PBSC collection failure rate, compared to a 4% rate for those receiving other chemotherapy (P = 0.04).

Study details: Single-center retrospective study of 181 consecutive patients with mantle cell lymphoma over a 10-year period spanning the introduction of plerixafor.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by City of Hope and the National Cancer Institute; the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Amandeep Salhotra, et al. Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma patients is associated with higher rates of hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization failure despite plerixafor rescue. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017; 23:1264-1268.

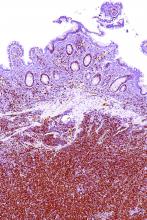

Alcohol misuse universal screening effective and efficient

Universal screening for alcohol misuse in acute medical admissions is feasible and can reduce readmissions for liver disease, according to a new study.

Detecting patients’ alcohol misuse early can help treat or prevent alcohol-related liver disease, such as cirrhosis; however, screening is not being used in a routine, effective way, according to Greta Westwood, PhD, head of Nursing, Midwifery, and AHP Research at Portsmouth (England) Hospitals and her fellow investigators.

“In primary care, screening is highly variable, and treatment rates are low, often focusing on patients who already have advanced psychiatric or physical illness,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “In addition, many patients with alcohol use disorders do not fully engage with primary care services for a variety of reasons, often leading to excessive use of the hospital ED as the first point of contact.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective, observational study of 53,165 patients who were admitted to the acute medical unit at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, England, between July 2011 and March 2014 (J Hepatol. 2017 Sep;67[3]:559-67).

More than half of patients were male (52%), the average patient age was 67 years, and the patients had an average of three previous hospital admissions.

Of the patients observed, 48,211 (90.68%) completed the screening test, while the remaining 4,934 (9.32%) did not.

Those who were not screened had a higher mortality rate than did those who were (8.30% vs 6.17%; P less than .001), were more likely to be discharged the same day (3.37% vs. 1.87%; P less than .001), and were more likely to discharge themselves (29.67% vs. 13.31%; P less than .001).

The screening process, an electronic modified version of the Paddington Alcohol Test, consisted of the nurses’ asking a series of questions about types of alcohol consumed, frequency and maximum daily amount, whether the admission was considered alcohol related, and they documented signs of alcohol withdrawal.

Patients were then given a score based on how the answers compared with the healthy level of alcohol consumption, with 0-2 points considered “low risk,” 3-5 points considered “increasing risk,” and 6-10 points considered “high risk.”

Those assigned a low-risk status were not referred to intervention, but doctors recommended increasing-risk patients attend a community alcohol intervention team for brief intervention, while high-risk patients were automatically referred to an Alcohol Specialist Nursing Service (ASNS).

Of those screened, there were 1,135 patients (2.33%) considered at increasing risk of alcohol misuse and 1,921 (3.98%) at high risk.

While 68.5% of patients with a high-risk score were referred to the ASNS, all those who were referred completed the medical detoxification course, according to investigators.

High-risk patients were found to have had, on average, more hospital visits than increasing- and low-risk patients – 4.74 visits, compared with 2.92 and 3.00, respectively; they also reported more ED trips – 7.68 visits, compared with 3.81 and 2.64, respectively.

Dr. Westwood and her colleagues found that, when using the screening tool, investigators were more likely to find signs of alcohol-related liver disease among those with higher scores.

Liver, pancreatic, and digestive disorders accounted for 22.1% of primary admission codes of high-risk patients, compared with 3.2% of low-risk patients.

Investigators wrote that this tool can help doctors identify at-risk patients early and attack the problem of alcohol misuse head on and in a timely manner.

“It is vital that patients with cirrhosis who continue to drink are identified and referred to dedicated hospital alcohol care teams,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “Screening can identify patients at an increased risk of alcohol-related harm whose range of diagnoses is not dissimilar to lower-risk patients and whose misuse of alcohol might otherwise have not been identified.”

Investigators did not account for decreased scores or testing effectiveness in patients readmitted and retested. Additionally, the long-term impact of ASNS care is still being studied.

Two investigators reported affiliations with the Learning Clinic, which created and licensed the analysis program that is part of the screening tool. All other investigators, including Dr. Westwood, reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Universal screening for alcohol misuse in acute medical admissions is feasible and can reduce readmissions for liver disease, according to a new study.

Detecting patients’ alcohol misuse early can help treat or prevent alcohol-related liver disease, such as cirrhosis; however, screening is not being used in a routine, effective way, according to Greta Westwood, PhD, head of Nursing, Midwifery, and AHP Research at Portsmouth (England) Hospitals and her fellow investigators.

“In primary care, screening is highly variable, and treatment rates are low, often focusing on patients who already have advanced psychiatric or physical illness,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “In addition, many patients with alcohol use disorders do not fully engage with primary care services for a variety of reasons, often leading to excessive use of the hospital ED as the first point of contact.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective, observational study of 53,165 patients who were admitted to the acute medical unit at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, England, between July 2011 and March 2014 (J Hepatol. 2017 Sep;67[3]:559-67).

More than half of patients were male (52%), the average patient age was 67 years, and the patients had an average of three previous hospital admissions.

Of the patients observed, 48,211 (90.68%) completed the screening test, while the remaining 4,934 (9.32%) did not.

Those who were not screened had a higher mortality rate than did those who were (8.30% vs 6.17%; P less than .001), were more likely to be discharged the same day (3.37% vs. 1.87%; P less than .001), and were more likely to discharge themselves (29.67% vs. 13.31%; P less than .001).

The screening process, an electronic modified version of the Paddington Alcohol Test, consisted of the nurses’ asking a series of questions about types of alcohol consumed, frequency and maximum daily amount, whether the admission was considered alcohol related, and they documented signs of alcohol withdrawal.

Patients were then given a score based on how the answers compared with the healthy level of alcohol consumption, with 0-2 points considered “low risk,” 3-5 points considered “increasing risk,” and 6-10 points considered “high risk.”

Those assigned a low-risk status were not referred to intervention, but doctors recommended increasing-risk patients attend a community alcohol intervention team for brief intervention, while high-risk patients were automatically referred to an Alcohol Specialist Nursing Service (ASNS).

Of those screened, there were 1,135 patients (2.33%) considered at increasing risk of alcohol misuse and 1,921 (3.98%) at high risk.

While 68.5% of patients with a high-risk score were referred to the ASNS, all those who were referred completed the medical detoxification course, according to investigators.

High-risk patients were found to have had, on average, more hospital visits than increasing- and low-risk patients – 4.74 visits, compared with 2.92 and 3.00, respectively; they also reported more ED trips – 7.68 visits, compared with 3.81 and 2.64, respectively.

Dr. Westwood and her colleagues found that, when using the screening tool, investigators were more likely to find signs of alcohol-related liver disease among those with higher scores.

Liver, pancreatic, and digestive disorders accounted for 22.1% of primary admission codes of high-risk patients, compared with 3.2% of low-risk patients.

Investigators wrote that this tool can help doctors identify at-risk patients early and attack the problem of alcohol misuse head on and in a timely manner.

“It is vital that patients with cirrhosis who continue to drink are identified and referred to dedicated hospital alcohol care teams,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “Screening can identify patients at an increased risk of alcohol-related harm whose range of diagnoses is not dissimilar to lower-risk patients and whose misuse of alcohol might otherwise have not been identified.”

Investigators did not account for decreased scores or testing effectiveness in patients readmitted and retested. Additionally, the long-term impact of ASNS care is still being studied.

Two investigators reported affiliations with the Learning Clinic, which created and licensed the analysis program that is part of the screening tool. All other investigators, including Dr. Westwood, reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Universal screening for alcohol misuse in acute medical admissions is feasible and can reduce readmissions for liver disease, according to a new study.

Detecting patients’ alcohol misuse early can help treat or prevent alcohol-related liver disease, such as cirrhosis; however, screening is not being used in a routine, effective way, according to Greta Westwood, PhD, head of Nursing, Midwifery, and AHP Research at Portsmouth (England) Hospitals and her fellow investigators.

“In primary care, screening is highly variable, and treatment rates are low, often focusing on patients who already have advanced psychiatric or physical illness,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “In addition, many patients with alcohol use disorders do not fully engage with primary care services for a variety of reasons, often leading to excessive use of the hospital ED as the first point of contact.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective, observational study of 53,165 patients who were admitted to the acute medical unit at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, England, between July 2011 and March 2014 (J Hepatol. 2017 Sep;67[3]:559-67).

More than half of patients were male (52%), the average patient age was 67 years, and the patients had an average of three previous hospital admissions.

Of the patients observed, 48,211 (90.68%) completed the screening test, while the remaining 4,934 (9.32%) did not.

Those who were not screened had a higher mortality rate than did those who were (8.30% vs 6.17%; P less than .001), were more likely to be discharged the same day (3.37% vs. 1.87%; P less than .001), and were more likely to discharge themselves (29.67% vs. 13.31%; P less than .001).

The screening process, an electronic modified version of the Paddington Alcohol Test, consisted of the nurses’ asking a series of questions about types of alcohol consumed, frequency and maximum daily amount, whether the admission was considered alcohol related, and they documented signs of alcohol withdrawal.

Patients were then given a score based on how the answers compared with the healthy level of alcohol consumption, with 0-2 points considered “low risk,” 3-5 points considered “increasing risk,” and 6-10 points considered “high risk.”

Those assigned a low-risk status were not referred to intervention, but doctors recommended increasing-risk patients attend a community alcohol intervention team for brief intervention, while high-risk patients were automatically referred to an Alcohol Specialist Nursing Service (ASNS).

Of those screened, there were 1,135 patients (2.33%) considered at increasing risk of alcohol misuse and 1,921 (3.98%) at high risk.

While 68.5% of patients with a high-risk score were referred to the ASNS, all those who were referred completed the medical detoxification course, according to investigators.

High-risk patients were found to have had, on average, more hospital visits than increasing- and low-risk patients – 4.74 visits, compared with 2.92 and 3.00, respectively; they also reported more ED trips – 7.68 visits, compared with 3.81 and 2.64, respectively.

Dr. Westwood and her colleagues found that, when using the screening tool, investigators were more likely to find signs of alcohol-related liver disease among those with higher scores.

Liver, pancreatic, and digestive disorders accounted for 22.1% of primary admission codes of high-risk patients, compared with 3.2% of low-risk patients.

Investigators wrote that this tool can help doctors identify at-risk patients early and attack the problem of alcohol misuse head on and in a timely manner.

“It is vital that patients with cirrhosis who continue to drink are identified and referred to dedicated hospital alcohol care teams,” Dr. Westwood and her colleagues wrote. “Screening can identify patients at an increased risk of alcohol-related harm whose range of diagnoses is not dissimilar to lower-risk patients and whose misuse of alcohol might otherwise have not been identified.”

Investigators did not account for decreased scores or testing effectiveness in patients readmitted and retested. Additionally, the long-term impact of ASNS care is still being studied.

Two investigators reported affiliations with the Learning Clinic, which created and licensed the analysis program that is part of the screening tool. All other investigators, including Dr. Westwood, reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who were admitted and were not screened for alcohol misuse risk had a higher mortality rate, compared with those who were screened (8.3% vs. 6.17%; P less than .001).

Data source: Retrospective observational study of 53,165 patients admitted to the acute medical clinic of the Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, England, between July 2011 and March 2014.

Disclosures: Two investigators reported affiliations with the Learning Clinic, which created and licensed the analysis program that is part of the screening tool. All other investigators, including Dr. Westwood, reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Team identifies mutation that causes EPP

Researchers say they have discovered a genetic mutation that triggers erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).

The team performed genetic sequencing on members of a family from Northern France who had EPP of a previously unknown genetic signature.

The sequencing revealed a mutation in the gene CLPX that promotes EPP.

Barry Paw MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center in Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in PNAS.

About EPP

To produce heme, the body goes through porphyrin synthesis, which mainly occurs in the liver and bone marrow. Genetic defects can hinder the body’s ability to produce heme, and a decrease in heme production leads to a buildup of protoporphyrin components.

In the case of EPP, protoporphyrin IX accumulates in the red blood cells, plasma, and sometimes the liver.

When protoporphyrin IX is exposed to light, it produces chemicals that damage surrounding cells. As a result, people with EPP experience swelling, burning, and redness of the skin after exposure to sunlight.

“People with EPP are chronically anemic, which makes them feel very tired and look very pale, with increased photosensitivity because they can’t come out in the daylight,” Dr Paw said. “Even on a cloudy day, there’s enough ultraviolet light to cause blistering and disfigurement of the exposed body parts, ears, and nose.”

Although some genetic pathways leading to the build-up of protoporphyrin IX have already been described, many cases of EPP remain unexplained.

New discovery

Dr Paw and his colleagues noted that heme synthesis is controlled by the mitochondrial AAA+ unfoldase ClpX, which participates in the degradation and activation of δ-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS).

In their analysis of the French family with EPP, the researchers discovered a dominant mutation in the ATPase active site of CLPX. This mutation—p.Gly298Asp—prompts the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

The researchers said the mutation partially inactivates CLPX, which increases the post-translational stability of ALAS. This increases ALAS protein and ALA levels and leads to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

“This newly discovered mutation really highlights the complex genetic network that underpins heme metabolism,” Dr Paw said. “Loss-of-function mutations in any number of genes that are part of this network can result in devastating, disfiguring disorders.”

Dr Paw also noted that identifying the mutations that contribute to EPP and other porphyrias could pave the way for new methods of treating these disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a genetic mutation that triggers erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).

The team performed genetic sequencing on members of a family from Northern France who had EPP of a previously unknown genetic signature.

The sequencing revealed a mutation in the gene CLPX that promotes EPP.

Barry Paw MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center in Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in PNAS.

About EPP

To produce heme, the body goes through porphyrin synthesis, which mainly occurs in the liver and bone marrow. Genetic defects can hinder the body’s ability to produce heme, and a decrease in heme production leads to a buildup of protoporphyrin components.

In the case of EPP, protoporphyrin IX accumulates in the red blood cells, plasma, and sometimes the liver.

When protoporphyrin IX is exposed to light, it produces chemicals that damage surrounding cells. As a result, people with EPP experience swelling, burning, and redness of the skin after exposure to sunlight.

“People with EPP are chronically anemic, which makes them feel very tired and look very pale, with increased photosensitivity because they can’t come out in the daylight,” Dr Paw said. “Even on a cloudy day, there’s enough ultraviolet light to cause blistering and disfigurement of the exposed body parts, ears, and nose.”

Although some genetic pathways leading to the build-up of protoporphyrin IX have already been described, many cases of EPP remain unexplained.

New discovery

Dr Paw and his colleagues noted that heme synthesis is controlled by the mitochondrial AAA+ unfoldase ClpX, which participates in the degradation and activation of δ-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS).

In their analysis of the French family with EPP, the researchers discovered a dominant mutation in the ATPase active site of CLPX. This mutation—p.Gly298Asp—prompts the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

The researchers said the mutation partially inactivates CLPX, which increases the post-translational stability of ALAS. This increases ALAS protein and ALA levels and leads to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

“This newly discovered mutation really highlights the complex genetic network that underpins heme metabolism,” Dr Paw said. “Loss-of-function mutations in any number of genes that are part of this network can result in devastating, disfiguring disorders.”

Dr Paw also noted that identifying the mutations that contribute to EPP and other porphyrias could pave the way for new methods of treating these disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a genetic mutation that triggers erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).

The team performed genetic sequencing on members of a family from Northern France who had EPP of a previously unknown genetic signature.

The sequencing revealed a mutation in the gene CLPX that promotes EPP.

Barry Paw MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center in Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported this discovery in PNAS.

About EPP

To produce heme, the body goes through porphyrin synthesis, which mainly occurs in the liver and bone marrow. Genetic defects can hinder the body’s ability to produce heme, and a decrease in heme production leads to a buildup of protoporphyrin components.

In the case of EPP, protoporphyrin IX accumulates in the red blood cells, plasma, and sometimes the liver.

When protoporphyrin IX is exposed to light, it produces chemicals that damage surrounding cells. As a result, people with EPP experience swelling, burning, and redness of the skin after exposure to sunlight.

“People with EPP are chronically anemic, which makes them feel very tired and look very pale, with increased photosensitivity because they can’t come out in the daylight,” Dr Paw said. “Even on a cloudy day, there’s enough ultraviolet light to cause blistering and disfigurement of the exposed body parts, ears, and nose.”

Although some genetic pathways leading to the build-up of protoporphyrin IX have already been described, many cases of EPP remain unexplained.

New discovery

Dr Paw and his colleagues noted that heme synthesis is controlled by the mitochondrial AAA+ unfoldase ClpX, which participates in the degradation and activation of δ-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS).

In their analysis of the French family with EPP, the researchers discovered a dominant mutation in the ATPase active site of CLPX. This mutation—p.Gly298Asp—prompts the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

The researchers said the mutation partially inactivates CLPX, which increases the post-translational stability of ALAS. This increases ALAS protein and ALA levels and leads to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX.

“This newly discovered mutation really highlights the complex genetic network that underpins heme metabolism,” Dr Paw said. “Loss-of-function mutations in any number of genes that are part of this network can result in devastating, disfiguring disorders.”

Dr Paw also noted that identifying the mutations that contribute to EPP and other porphyrias could pave the way for new methods of treating these disorders. ![]()

Minimally invasive esophagectomy may mean less major morbidity

COLORADO SPRINGS – Minimally invasive esophagectomy was associated with a significantly lower rate of postoperative major morbidity as well as a mean 1-day briefer length of stay than open esophagectomy in a propensity-matched analysis of the real-world American College of Surgeons-National Quality Improvement Program database, Mark F. Berry, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

However, both of the study’s discussants questioned whether the reported modest absolute reduction in major morbidity was really attributable to the minimally invasive approach or could instead have resulted from one of several potential confounders that couldn’t be fully adjusted for, given inherent limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database.

“There was a statistically significant difference in morbidity,” replied Dr. Berry of Stanford (Calif.) University. “It was a 4% absolute difference, which I think is probably clinically meaningful, but certainly it’s not really, really dramatic.”

“What I think we found is that it’s safe to do a minimally invasive esophagectomy and safe for people to introduce it into their practice. But it’s not necessarily something that’s a game changer, unlike what’s been seen with minimally invasive approaches for some other things,” said Dr. Berry, who added that he didn’t wish to overstate the importance of the observed difference in morbidity.

Studies from high-volume centers show that minimally-invasive esophagectomy (MIE) reduces length of stay, postoperative major morbidity, and features equivalent or even slightly lower mortality than traditional open esophagectomy, the generalizability of these findings beyond such centers is questionable. That’s why Dr. Berry and his coinvestigators turned to the ACS-NSQIP database, which includes all esophagectomies performed for esophageal cancer at roughly 700 U.S. hospitals, not just those done by board-certified thoracic surgeons.

He presented a retrospective cohort study of 3,901 esophagectomy patients during 2005-2013 who met study criteria, 16.4% of whom had MIE. The use of this approach increased steadily from 6.5% of all esophagectomies in 2005 to 22.3% in 2013. A propensity-matched analysis designed to neutralize potentially confounding differences included 638 MIE and 1,914 open esophagectomy patients.

The primary outcome was the 30-day rate of composite major morbidity in the realms of various wound, respiratory, renal, and cardiovascular complications. The rate was 36.1% in the MIE group and 40.5% with open esophagectomy in the propensity-matched analysis, an absolute risk reduction of 4.4% and a relative risk reduction of 17%. Although rates were consistently slightly lower in each of the categories of major morbidity, those individual differences didn’t achieve statistical significance. The difference in major morbidity became significant only when major morbidity was considered as a whole.

Mean length of stay was 9 days with MIE and 10 days with open surgery.

There was no significant difference between the two study groups in 30-day rates of readmission, reoperation, or mortality.

Discussant Donald E. Low said “esophagectomy is being analysed regarding its place in all sorts of presentations, stages, and situations, so the aspect of making sure that we’re delivering the services as efficiently as possible is going to become more important, not less important.”

That being said, he noted that there is no specific CPT code for MIE. That raises the possibility of an uncertain amount of procedural misclassification in the ACS-NSQIP database.

Also, the only significant difference in major morbidity between the two study groups was in the subcategory of intra- or postoperative bleeding requiring transfusion, which occurred in 10.8% of the MIE and 16.7% of the open esophagectomy groups, observed Dr. Low, director of the Esophageal Center of Excellence at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle.

“Some of us believe that blood utilization and transfusion requirement is really a quality measure and not a complication,” the surgeon said. And if that outcome is excluded from consideration, then there is no significant difference in major morbidity.