User login

FDA places partial hold on trials of nivolumab in MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on 3 trials of the PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo).

The trials were designed to investigate nivolumab-based combination regimens in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The partial clinical hold means patients currently enrolled in these 3 trials can continue treatment if they are experiencing clinical benefit. However, no new patients can be enrolled at this time.

The partial clinical hold is related to risks identified in trials studying another anti-PD-1 agent, pembrolizumab, in MM patients.

Data from the pembrolizumab trials indicate the risks outweigh the benefits when PD-1/PD-L1 treatment is given to MM patients in combination with dexamethasone and pomalidomide or lenalidomide.

In addition, there may be an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for MM patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 treatments alone or in other combinations.

With this in mind, the FDA placed the partial hold on the following nivolumab trials:

- CheckMate-602: A randomized, phase 3 trial of combinations of nivolumab, elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory MM

- CheckMate-039: A phase 1 study intended to establish the tolerability of nivolumab and the combination of nivolumab and daratumumab, with or without pomalidomide and dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory MM

- CA204142: A phase 2 study of elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, and in combination with nivolumab, in patients with MM who relapsed after or were refractory to prior treatment with lenalidomide.

Other studies of nivolumab will continue as planned.

Bristol-Myers Squibb, the company developing and marketing nivolumab, said it remains steadfast in its commitment to improve outcomes for MM patients and will work closely with the FDA to address concerns.

Nivolumab is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Adults with classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant and brentuximab vedotin or after 3 or more lines of therapy, including autologous transplant

- Patients with previously treated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer

- Metastatic melanoma patients

- Advanced renal cell carcinoma patients who received prior anti-angiogenic therapy

- Patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck on or after platinum-based therapy

- Patients with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-based chemotherapy

- Patients (≥12 years) with microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer that has progressed following treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on 3 trials of the PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo).

The trials were designed to investigate nivolumab-based combination regimens in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The partial clinical hold means patients currently enrolled in these 3 trials can continue treatment if they are experiencing clinical benefit. However, no new patients can be enrolled at this time.

The partial clinical hold is related to risks identified in trials studying another anti-PD-1 agent, pembrolizumab, in MM patients.

Data from the pembrolizumab trials indicate the risks outweigh the benefits when PD-1/PD-L1 treatment is given to MM patients in combination with dexamethasone and pomalidomide or lenalidomide.

In addition, there may be an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for MM patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 treatments alone or in other combinations.

With this in mind, the FDA placed the partial hold on the following nivolumab trials:

- CheckMate-602: A randomized, phase 3 trial of combinations of nivolumab, elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory MM

- CheckMate-039: A phase 1 study intended to establish the tolerability of nivolumab and the combination of nivolumab and daratumumab, with or without pomalidomide and dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory MM

- CA204142: A phase 2 study of elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, and in combination with nivolumab, in patients with MM who relapsed after or were refractory to prior treatment with lenalidomide.

Other studies of nivolumab will continue as planned.

Bristol-Myers Squibb, the company developing and marketing nivolumab, said it remains steadfast in its commitment to improve outcomes for MM patients and will work closely with the FDA to address concerns.

Nivolumab is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Adults with classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant and brentuximab vedotin or after 3 or more lines of therapy, including autologous transplant

- Patients with previously treated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer

- Metastatic melanoma patients

- Advanced renal cell carcinoma patients who received prior anti-angiogenic therapy

- Patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck on or after platinum-based therapy

- Patients with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-based chemotherapy

- Patients (≥12 years) with microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer that has progressed following treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on 3 trials of the PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo).

The trials were designed to investigate nivolumab-based combination regimens in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The partial clinical hold means patients currently enrolled in these 3 trials can continue treatment if they are experiencing clinical benefit. However, no new patients can be enrolled at this time.

The partial clinical hold is related to risks identified in trials studying another anti-PD-1 agent, pembrolizumab, in MM patients.

Data from the pembrolizumab trials indicate the risks outweigh the benefits when PD-1/PD-L1 treatment is given to MM patients in combination with dexamethasone and pomalidomide or lenalidomide.

In addition, there may be an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for MM patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 treatments alone or in other combinations.

With this in mind, the FDA placed the partial hold on the following nivolumab trials:

- CheckMate-602: A randomized, phase 3 trial of combinations of nivolumab, elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory MM

- CheckMate-039: A phase 1 study intended to establish the tolerability of nivolumab and the combination of nivolumab and daratumumab, with or without pomalidomide and dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory MM

- CA204142: A phase 2 study of elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, and in combination with nivolumab, in patients with MM who relapsed after or were refractory to prior treatment with lenalidomide.

Other studies of nivolumab will continue as planned.

Bristol-Myers Squibb, the company developing and marketing nivolumab, said it remains steadfast in its commitment to improve outcomes for MM patients and will work closely with the FDA to address concerns.

Nivolumab is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Adults with classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant and brentuximab vedotin or after 3 or more lines of therapy, including autologous transplant

- Patients with previously treated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer

- Metastatic melanoma patients

- Advanced renal cell carcinoma patients who received prior anti-angiogenic therapy

- Patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck on or after platinum-based therapy

- Patients with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-based chemotherapy

- Patients (≥12 years) with microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer that has progressed following treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

Does Diet Matter in Multiple Sclerosis?

Q) What is known about the impact of diet on multiple sclerosis? How can I advise my patients with MS?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and degenerative central nervous system disease affecting more than 2.5 million people worldwide. Today, if a Google search is performed for “diet and MS,” more than 67 million results are obtained. Many tout specific protocols as beneficial for MS but have no substantial data to support these claims. This can be confusing for patients as well as providers. How should you advise those who ask for advice on dietary modifications to help control symptoms or disease course?

First, it’s important to remember that individuals with MS have a reduced median lifespan (by about seven years), compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, patients with MS commonly have comorbid conditions—such as diabetes, obesity, and ischemic heart disease—that increase mortality risk.1,2 Diet and nutrition are significant factors that impact the course of these diseases.

We must also bear in mind that patients with MS experience symptoms that may impede their efforts to prepare meals. In a 2008 study of 123 MS patients (more than 50% of whom were overweight or obese), fatigue was cited as a significant factor that limited cooking and food preparation. Cognitive impairment and depression also may affect dietary intake. Interestingly, the average recorded intake for all food groups was less than that recommended in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.3

A web-based survey conducted by the German MS Society in 2011 revealed that 42% of the 337 respondents had modified their diet due to MS. These modifications included change in intake of fatty acids; decrease or elimination of meat, sugar, and additives; and introduction of a low-carb or Paleo diet.4

Among an international sample of 2,087 MS patients, a significant association was found between a healthy diet and improved quality of life (both physical and mental) and reduced disability. This “healthy consumption” of fruits, vegetables, and dietary fat was also associated with a marginally decreased risk for relapse. Patients who demonstrated increased disease activity were more likely to have poor consumption of fruits, vegetables, and fats and to consume more meat and dairy products.5

There has also been research on specific components of dietary intake. Antioxidant-containing foods, for example, may have an anti-inflammatory effect.6 Vitamin B12 deficiency plays a role in immunomodulatory effect, as well as formation of the myelin sheath, although its role (and the effect of biotin supplementation) in MS disease progression requires further study.7 Also ongoing is research into various calorie-restriction protocols, altering both timing and amount of caloric intake, since some data suggest this strategy reduces leptin, a satiety hormone that increases inflammation and has been shown to promote more aggressive MS in a mouse model.8

In the meantime, what can we conclude about diet and MS? A recent review determined that, although there is insufficient data to support one specific diet, there is sufficient evidence to recommend consumption of fish, foods lower in fat, whole grains, vitamin D, and supplemental omega fatty acids.5

It is important to discuss diet with our MS patients. In the German survey, 82% of patients felt that diet was important, yet only 10% had asked a provider for nutritional advice.4 In another study, patients indicated that food labels were their top source for nutrition information; only 20% sought advice from a nutritionist.3 We need to ask our MS patients if they are following a particular diet and be prepared to discuss potentially beneficial dietary choices with them—and offer referral to a nutritionist to those who require additional direction and support.—SP

Stacey Panasci, MSPAS, PA-C

Springfield Neurology Associates, LLC

Massachusetts

1. Marrie RA, Elliott L, Marriott J, et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;85(3):240-247.

2. Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Koebnick C. Childhood obesity and risk of pediatric multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome. Neurology. 2013;80(6):548-552.

3. Goodman S, Gulick EE. Dietary practices of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:47-57.

4. Riemann- Lorenz K, Eilers M, von Geldern G, et al. Dietary interventions in multiple sclerosis: development and pilot testing of an evidence based patient education program. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165246.

5. Hadgkiss EJ, Jekinek GA, Weiland TJ, et al. The association of diet with quality of life, disability, and relapse rate in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Nutr Neurosci. 2015;18(3):125-136.

6. Khalili M, Azimi A, Izadi V, et al. Does lipoic acid consumption affect the cytokine profile in multiple sclerosis patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(6):291-296.

7. Kocer B, Engur S, Ak F, Yilmaz M. Serum vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine levels and their association with clinical and electrophysiological parameters in multiple sclerosis.

J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:399-403.

8. Galgani M, Procaccini C, De Rosa V, et al. Leptin modulates the survival of autoreactive CD4+ T cells through the nutrient/energy-sensing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7474-7479.

Q) What is known about the impact of diet on multiple sclerosis? How can I advise my patients with MS?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and degenerative central nervous system disease affecting more than 2.5 million people worldwide. Today, if a Google search is performed for “diet and MS,” more than 67 million results are obtained. Many tout specific protocols as beneficial for MS but have no substantial data to support these claims. This can be confusing for patients as well as providers. How should you advise those who ask for advice on dietary modifications to help control symptoms or disease course?

First, it’s important to remember that individuals with MS have a reduced median lifespan (by about seven years), compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, patients with MS commonly have comorbid conditions—such as diabetes, obesity, and ischemic heart disease—that increase mortality risk.1,2 Diet and nutrition are significant factors that impact the course of these diseases.

We must also bear in mind that patients with MS experience symptoms that may impede their efforts to prepare meals. In a 2008 study of 123 MS patients (more than 50% of whom were overweight or obese), fatigue was cited as a significant factor that limited cooking and food preparation. Cognitive impairment and depression also may affect dietary intake. Interestingly, the average recorded intake for all food groups was less than that recommended in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.3

A web-based survey conducted by the German MS Society in 2011 revealed that 42% of the 337 respondents had modified their diet due to MS. These modifications included change in intake of fatty acids; decrease or elimination of meat, sugar, and additives; and introduction of a low-carb or Paleo diet.4

Among an international sample of 2,087 MS patients, a significant association was found between a healthy diet and improved quality of life (both physical and mental) and reduced disability. This “healthy consumption” of fruits, vegetables, and dietary fat was also associated with a marginally decreased risk for relapse. Patients who demonstrated increased disease activity were more likely to have poor consumption of fruits, vegetables, and fats and to consume more meat and dairy products.5

There has also been research on specific components of dietary intake. Antioxidant-containing foods, for example, may have an anti-inflammatory effect.6 Vitamin B12 deficiency plays a role in immunomodulatory effect, as well as formation of the myelin sheath, although its role (and the effect of biotin supplementation) in MS disease progression requires further study.7 Also ongoing is research into various calorie-restriction protocols, altering both timing and amount of caloric intake, since some data suggest this strategy reduces leptin, a satiety hormone that increases inflammation and has been shown to promote more aggressive MS in a mouse model.8

In the meantime, what can we conclude about diet and MS? A recent review determined that, although there is insufficient data to support one specific diet, there is sufficient evidence to recommend consumption of fish, foods lower in fat, whole grains, vitamin D, and supplemental omega fatty acids.5

It is important to discuss diet with our MS patients. In the German survey, 82% of patients felt that diet was important, yet only 10% had asked a provider for nutritional advice.4 In another study, patients indicated that food labels were their top source for nutrition information; only 20% sought advice from a nutritionist.3 We need to ask our MS patients if they are following a particular diet and be prepared to discuss potentially beneficial dietary choices with them—and offer referral to a nutritionist to those who require additional direction and support.—SP

Stacey Panasci, MSPAS, PA-C

Springfield Neurology Associates, LLC

Massachusetts

Q) What is known about the impact of diet on multiple sclerosis? How can I advise my patients with MS?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and degenerative central nervous system disease affecting more than 2.5 million people worldwide. Today, if a Google search is performed for “diet and MS,” more than 67 million results are obtained. Many tout specific protocols as beneficial for MS but have no substantial data to support these claims. This can be confusing for patients as well as providers. How should you advise those who ask for advice on dietary modifications to help control symptoms or disease course?

First, it’s important to remember that individuals with MS have a reduced median lifespan (by about seven years), compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, patients with MS commonly have comorbid conditions—such as diabetes, obesity, and ischemic heart disease—that increase mortality risk.1,2 Diet and nutrition are significant factors that impact the course of these diseases.

We must also bear in mind that patients with MS experience symptoms that may impede their efforts to prepare meals. In a 2008 study of 123 MS patients (more than 50% of whom were overweight or obese), fatigue was cited as a significant factor that limited cooking and food preparation. Cognitive impairment and depression also may affect dietary intake. Interestingly, the average recorded intake for all food groups was less than that recommended in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.3

A web-based survey conducted by the German MS Society in 2011 revealed that 42% of the 337 respondents had modified their diet due to MS. These modifications included change in intake of fatty acids; decrease or elimination of meat, sugar, and additives; and introduction of a low-carb or Paleo diet.4

Among an international sample of 2,087 MS patients, a significant association was found between a healthy diet and improved quality of life (both physical and mental) and reduced disability. This “healthy consumption” of fruits, vegetables, and dietary fat was also associated with a marginally decreased risk for relapse. Patients who demonstrated increased disease activity were more likely to have poor consumption of fruits, vegetables, and fats and to consume more meat and dairy products.5

There has also been research on specific components of dietary intake. Antioxidant-containing foods, for example, may have an anti-inflammatory effect.6 Vitamin B12 deficiency plays a role in immunomodulatory effect, as well as formation of the myelin sheath, although its role (and the effect of biotin supplementation) in MS disease progression requires further study.7 Also ongoing is research into various calorie-restriction protocols, altering both timing and amount of caloric intake, since some data suggest this strategy reduces leptin, a satiety hormone that increases inflammation and has been shown to promote more aggressive MS in a mouse model.8

In the meantime, what can we conclude about diet and MS? A recent review determined that, although there is insufficient data to support one specific diet, there is sufficient evidence to recommend consumption of fish, foods lower in fat, whole grains, vitamin D, and supplemental omega fatty acids.5

It is important to discuss diet with our MS patients. In the German survey, 82% of patients felt that diet was important, yet only 10% had asked a provider for nutritional advice.4 In another study, patients indicated that food labels were their top source for nutrition information; only 20% sought advice from a nutritionist.3 We need to ask our MS patients if they are following a particular diet and be prepared to discuss potentially beneficial dietary choices with them—and offer referral to a nutritionist to those who require additional direction and support.—SP

Stacey Panasci, MSPAS, PA-C

Springfield Neurology Associates, LLC

Massachusetts

1. Marrie RA, Elliott L, Marriott J, et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;85(3):240-247.

2. Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Koebnick C. Childhood obesity and risk of pediatric multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome. Neurology. 2013;80(6):548-552.

3. Goodman S, Gulick EE. Dietary practices of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:47-57.

4. Riemann- Lorenz K, Eilers M, von Geldern G, et al. Dietary interventions in multiple sclerosis: development and pilot testing of an evidence based patient education program. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165246.

5. Hadgkiss EJ, Jekinek GA, Weiland TJ, et al. The association of diet with quality of life, disability, and relapse rate in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Nutr Neurosci. 2015;18(3):125-136.

6. Khalili M, Azimi A, Izadi V, et al. Does lipoic acid consumption affect the cytokine profile in multiple sclerosis patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(6):291-296.

7. Kocer B, Engur S, Ak F, Yilmaz M. Serum vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine levels and their association with clinical and electrophysiological parameters in multiple sclerosis.

J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:399-403.

8. Galgani M, Procaccini C, De Rosa V, et al. Leptin modulates the survival of autoreactive CD4+ T cells through the nutrient/energy-sensing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7474-7479.

1. Marrie RA, Elliott L, Marriott J, et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;85(3):240-247.

2. Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Koebnick C. Childhood obesity and risk of pediatric multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome. Neurology. 2013;80(6):548-552.

3. Goodman S, Gulick EE. Dietary practices of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:47-57.

4. Riemann- Lorenz K, Eilers M, von Geldern G, et al. Dietary interventions in multiple sclerosis: development and pilot testing of an evidence based patient education program. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165246.

5. Hadgkiss EJ, Jekinek GA, Weiland TJ, et al. The association of diet with quality of life, disability, and relapse rate in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Nutr Neurosci. 2015;18(3):125-136.

6. Khalili M, Azimi A, Izadi V, et al. Does lipoic acid consumption affect the cytokine profile in multiple sclerosis patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(6):291-296.

7. Kocer B, Engur S, Ak F, Yilmaz M. Serum vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine levels and their association with clinical and electrophysiological parameters in multiple sclerosis.

J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:399-403.

8. Galgani M, Procaccini C, De Rosa V, et al. Leptin modulates the survival of autoreactive CD4+ T cells through the nutrient/energy-sensing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7474-7479.

Tips for avoiding laser treatment complications

SAN DIEGO – The way Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, sees it, the best way to avoid complications from using lasers for aesthetic procedures is to trust your own eyes, not the laser device itself.

“Lasers are never perfect,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “The same device made by the same manufacturer may produce highly different outputs at the same setting. Moreover, lasers produce much different energies after they’ve been serviced. So, if you have two devices sitting right next to each other, don’t assume that the energy output on one device is exactly the same as the other device.”

He also warned clinicians against taking a “cookbook approach” to using lasers, such as memorizing settings or using ones recommended by a colleague or a device manufacturer. “Some lasers are not externally calibrated,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “Safe and unsafe laser endpoints and close clinical observation are the best means to avoiding complications. Learn your endpoints. This is true with the selective photothermolysis lasers: the pigment lasers, vascular lasers, and laser hair removal. Unfortunately, when you use nonablative fractional lasers, there really isn’t an endpoint, so it’s going to be more difficult to discern in that case. The key clinical finding is the endpoint, not the energy setting.”

When treating pigmented lesions and tattoos, for example, immediate whitening is the desired endpoint, not tissue splatter. “So, if you see the epidermis fly off with your first pulse, dial it down,” Dr. Avram said. “It sounds obvious, but sometimes, if you’re working quickly, you figure it will be all right. Just stop and make sure you’re seeing what you’re supposed to be seeing.”

The desired endpoints for vascular lasers, meanwhile, include purpura, transient purpura, or vessel clearance. “What you don’t want to see is gray,” he said. Desired endpoints for hair removal include perifollicular edema and erythema. “What you don’t want to see is epidermal change or dermal tightening,” he added. “Observe the skin and the patient. If the skin is reacting strangely, stop and check all of your settings. If the patient is having an inordinate amount of pain, stop and check all of your settings. These are often the clues that can help you avoid harming a patient.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

SAN DIEGO – The way Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, sees it, the best way to avoid complications from using lasers for aesthetic procedures is to trust your own eyes, not the laser device itself.

“Lasers are never perfect,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “The same device made by the same manufacturer may produce highly different outputs at the same setting. Moreover, lasers produce much different energies after they’ve been serviced. So, if you have two devices sitting right next to each other, don’t assume that the energy output on one device is exactly the same as the other device.”

He also warned clinicians against taking a “cookbook approach” to using lasers, such as memorizing settings or using ones recommended by a colleague or a device manufacturer. “Some lasers are not externally calibrated,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “Safe and unsafe laser endpoints and close clinical observation are the best means to avoiding complications. Learn your endpoints. This is true with the selective photothermolysis lasers: the pigment lasers, vascular lasers, and laser hair removal. Unfortunately, when you use nonablative fractional lasers, there really isn’t an endpoint, so it’s going to be more difficult to discern in that case. The key clinical finding is the endpoint, not the energy setting.”

When treating pigmented lesions and tattoos, for example, immediate whitening is the desired endpoint, not tissue splatter. “So, if you see the epidermis fly off with your first pulse, dial it down,” Dr. Avram said. “It sounds obvious, but sometimes, if you’re working quickly, you figure it will be all right. Just stop and make sure you’re seeing what you’re supposed to be seeing.”

The desired endpoints for vascular lasers, meanwhile, include purpura, transient purpura, or vessel clearance. “What you don’t want to see is gray,” he said. Desired endpoints for hair removal include perifollicular edema and erythema. “What you don’t want to see is epidermal change or dermal tightening,” he added. “Observe the skin and the patient. If the skin is reacting strangely, stop and check all of your settings. If the patient is having an inordinate amount of pain, stop and check all of your settings. These are often the clues that can help you avoid harming a patient.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

SAN DIEGO – The way Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, sees it, the best way to avoid complications from using lasers for aesthetic procedures is to trust your own eyes, not the laser device itself.

“Lasers are never perfect,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “The same device made by the same manufacturer may produce highly different outputs at the same setting. Moreover, lasers produce much different energies after they’ve been serviced. So, if you have two devices sitting right next to each other, don’t assume that the energy output on one device is exactly the same as the other device.”

He also warned clinicians against taking a “cookbook approach” to using lasers, such as memorizing settings or using ones recommended by a colleague or a device manufacturer. “Some lasers are not externally calibrated,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “Safe and unsafe laser endpoints and close clinical observation are the best means to avoiding complications. Learn your endpoints. This is true with the selective photothermolysis lasers: the pigment lasers, vascular lasers, and laser hair removal. Unfortunately, when you use nonablative fractional lasers, there really isn’t an endpoint, so it’s going to be more difficult to discern in that case. The key clinical finding is the endpoint, not the energy setting.”

When treating pigmented lesions and tattoos, for example, immediate whitening is the desired endpoint, not tissue splatter. “So, if you see the epidermis fly off with your first pulse, dial it down,” Dr. Avram said. “It sounds obvious, but sometimes, if you’re working quickly, you figure it will be all right. Just stop and make sure you’re seeing what you’re supposed to be seeing.”

The desired endpoints for vascular lasers, meanwhile, include purpura, transient purpura, or vessel clearance. “What you don’t want to see is gray,” he said. Desired endpoints for hair removal include perifollicular edema and erythema. “What you don’t want to see is epidermal change or dermal tightening,” he added. “Observe the skin and the patient. If the skin is reacting strangely, stop and check all of your settings. If the patient is having an inordinate amount of pain, stop and check all of your settings. These are often the clues that can help you avoid harming a patient.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

FROM MOAS 2017

New recommendations tout biosimilars for rheumatologic diseases

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Orange Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

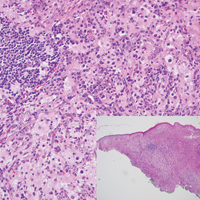

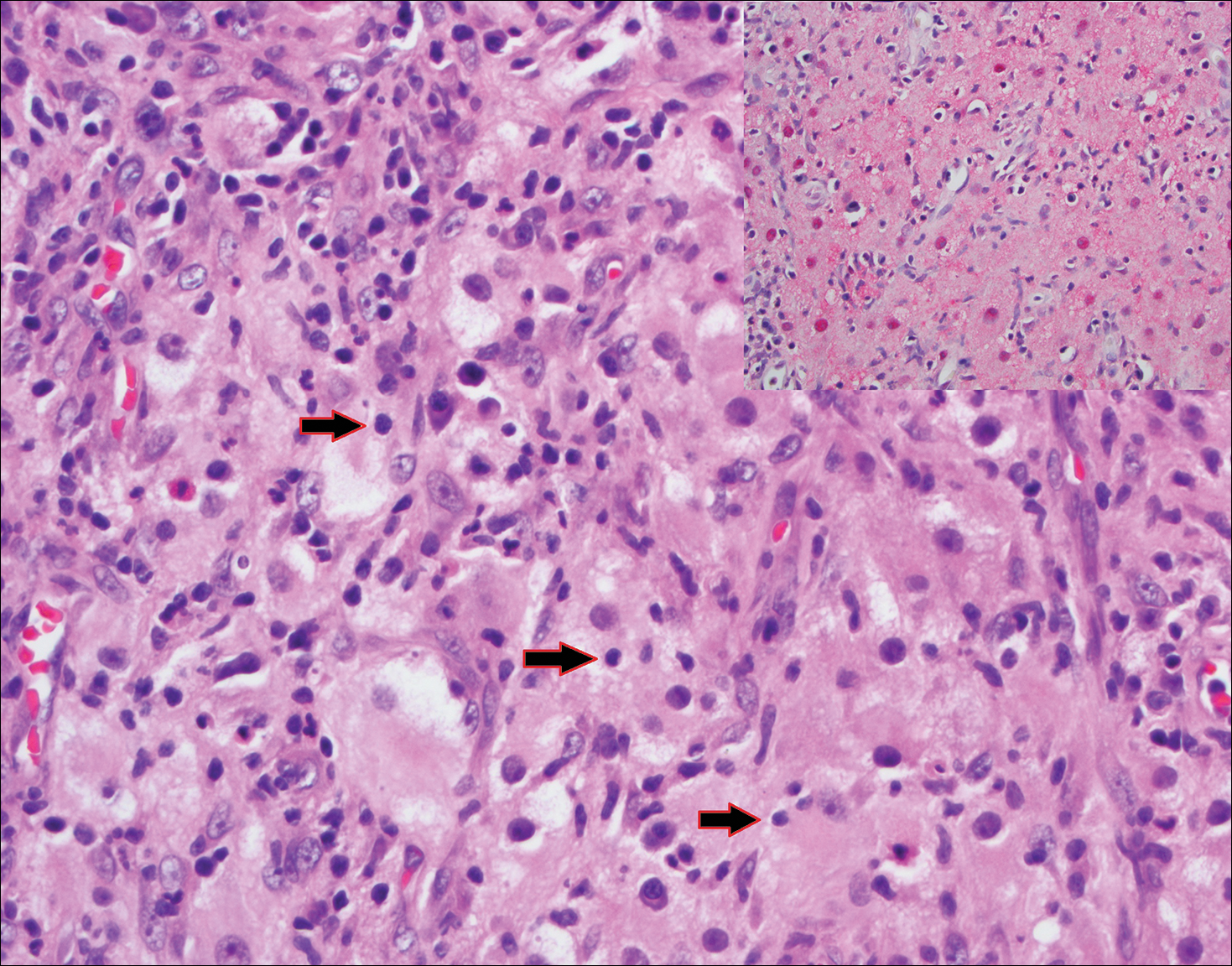

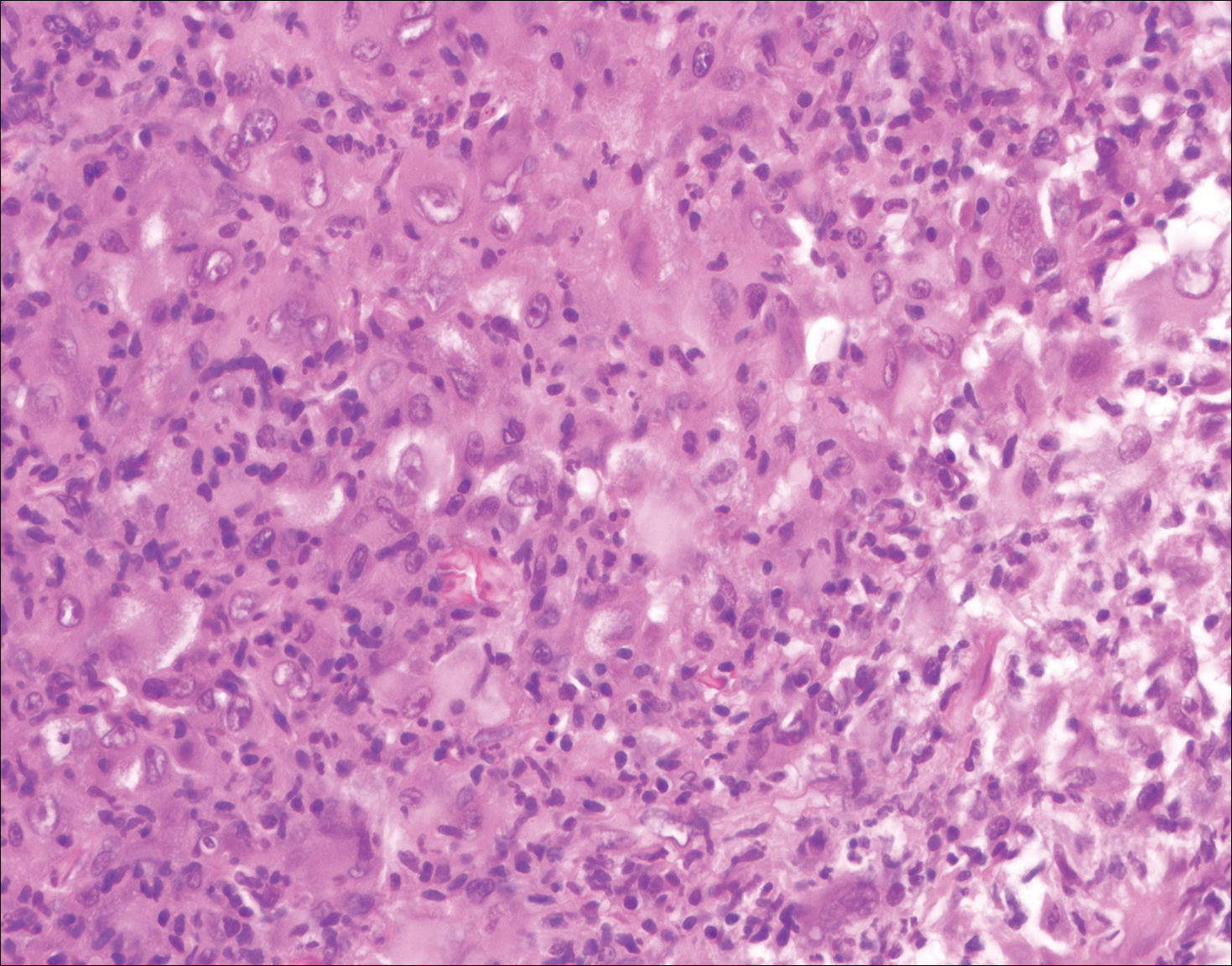

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

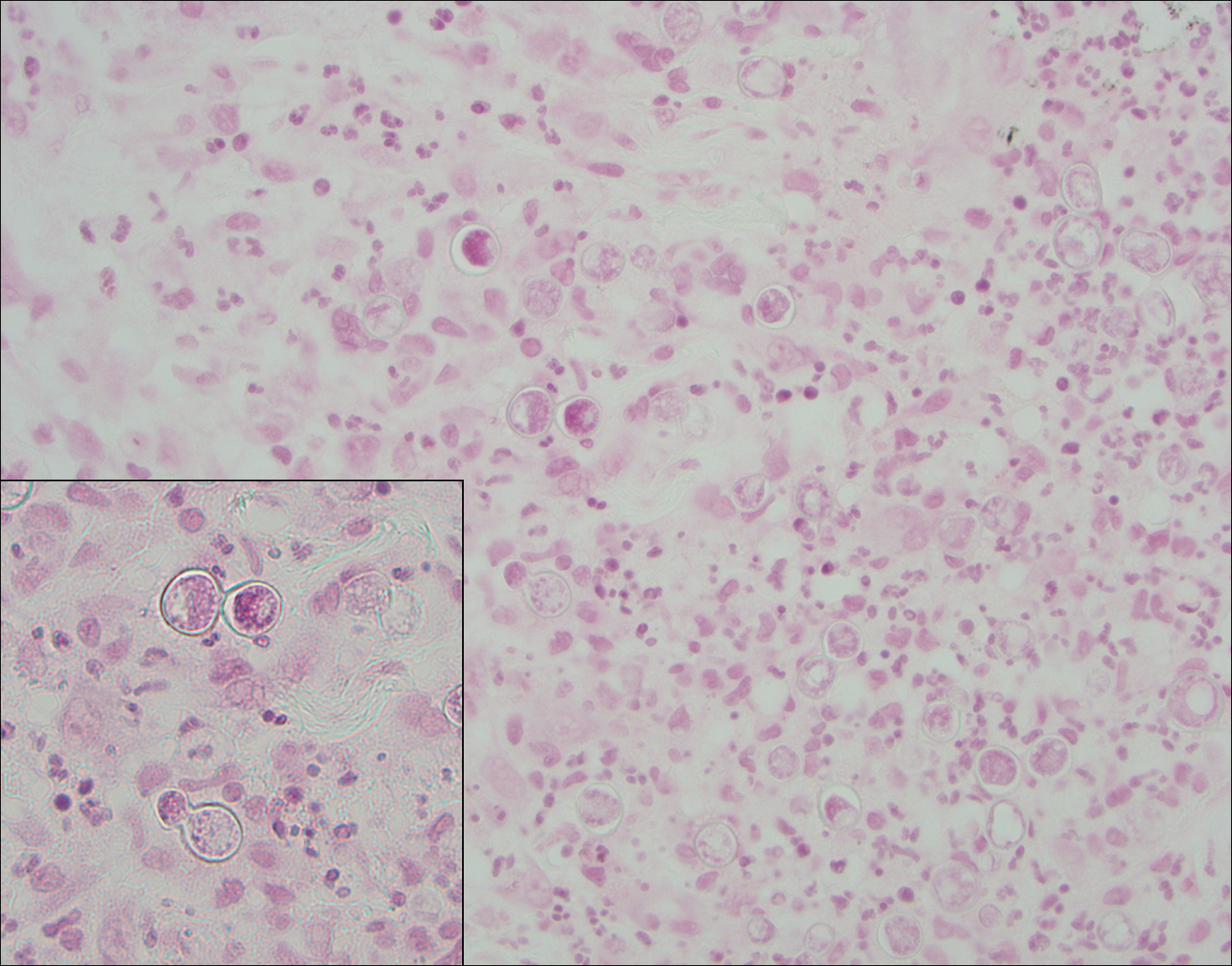

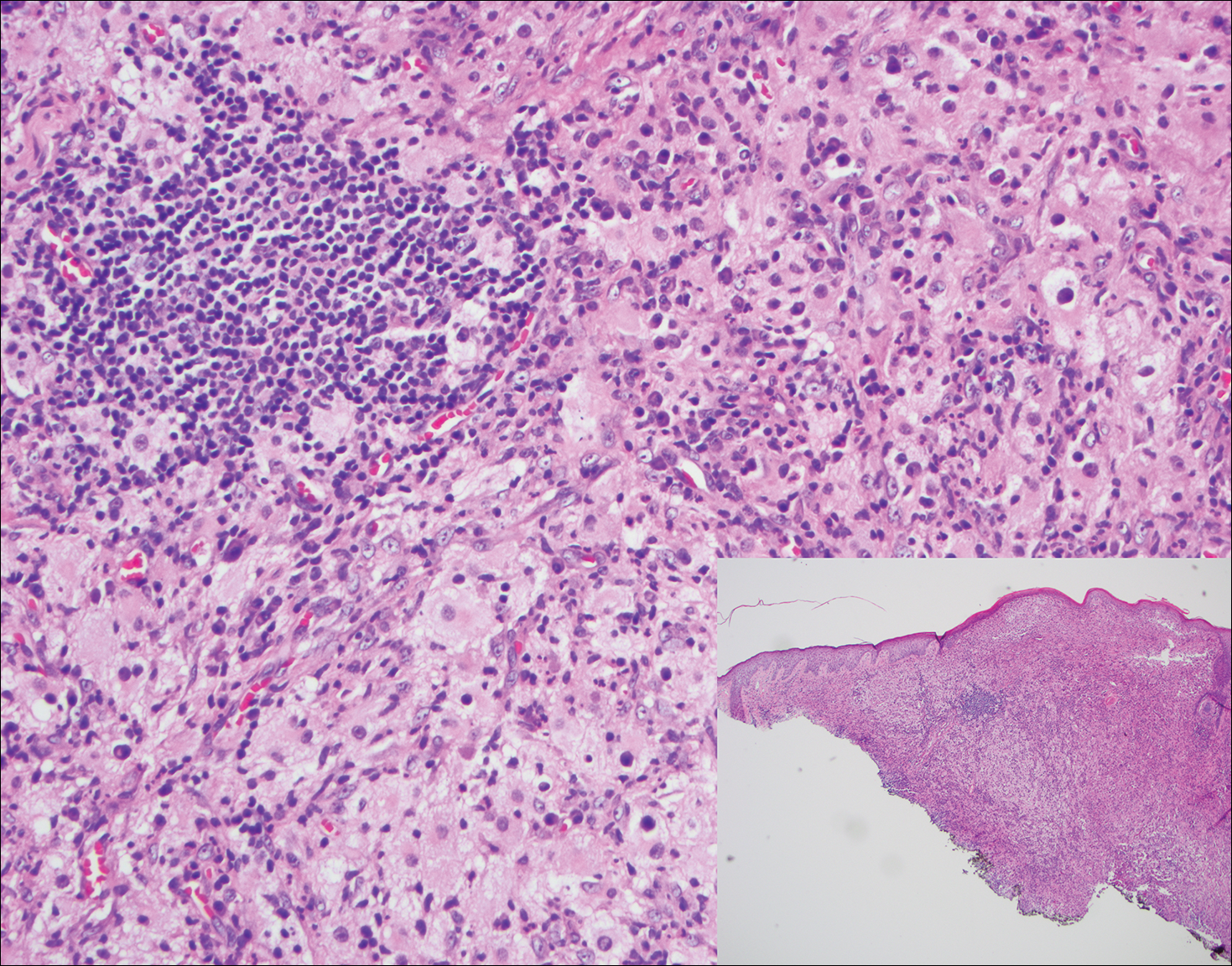

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

A 59-year-old man presented with itchy and mildly painful nodules on the head and neck of 7 months' duration. The patient denied fever, chills, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and other systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed multiple firm pink-orange nodules of varying sizes distributed on the scalp, face, and neck. Right-sided, painless, bulky cervical lymphadenopathy also was noted. An incisional biopsy was performed.

The Atopic Dermatitis Biologic Era Has Begun

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4

A biologic medication for AD has been long overdue. Psoriatic biologic medications have been tried in AD with occasional benefit in case reports but no major response in larger trials. Belloni et al5 reviewed early data on off-label usage of biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis or other indications applied to AD patients. In their review of cases, they make the point that results are variable and anti-B-cell activity may hold the greatest promise.5 On the other hand, a recent series of 3 patients showed limited response to rituximab in chronic AD,6 while a combination of omalizumab, an anti-IgE medication, and rituximab was helpful in some patients.7 Ultimately, the issue is that nonspecific biologics may or may not address the underlying disease factors in AD. Therefore, there has been a true need for biologic intervention targeted directly at the pathogenic mechanism of AD. Furthermore, the desire for a biologic targeted at AD is paired with the true need to have a medication so targeted that the drug would have little effect on the rest of the immune system, resulting in targeted immunomodulation without secondary risk of infections.

Wait no longer, that era arrived a few months ago with the rapid US Food and Drug Administration approval of dupilumab, an injectable medication used every 2 weeks for the therapy of moderate to severe AD. This fully human monoclonal antibody against the IL-4Rα subunit blocks IL-4 and IL-13, key inflammatory agents in the triggering of production of IgE and eosinophil activation. Even better than the fact that it is targeted are the excellent outcomes in the therapy of moderate to severe AD in adults and the minimal side-effect profile resulting in no requirements for laboratory screening or ongoing monitoring.8

Dupilumab seems to perform well, both clinically and in improving the lives of AD patients. Meta-analysis of trials involving dupilumab has shown improved health-related quality of life outcomes.9,10 Usage of dupilumab alone in clinical trials for 16 weeks (SOLO 1 and SOLO 2) has resulted in stunning reduction in disease severity with a limited side-effect profile, with patients most commonly reporting conjunctivitis.11 In real-world models where dupilumab is added into a regimen of topical corticosteroid usage (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial), patients fared even better with the combination, highlighting that this medication may best be used adjunctively to our skin care guidance as dermatologists.12

A new era for AD patients has arrived and we as practitioners are now fortunate to be able to therapeutically reach the worst cases of AD. The new era has only begun with dozens of new agents addressing a variety of interleukin pathways including IL-17 and IL-22 still under development. Ultimately, we hope that ongoing pediatric trials will allow us to glean the role of early disease intervention at the root cause of AD and address our abilities to prevent comorbidities and disease persistence. Will we be able to avert years of disabling disease? The future holds immense hope.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Somanunt S, Chinratanapisit S, Pacharn P, et al. The natural history of atopic dermatitis and its association with Atopic March [published online Dec 12, 2016]. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. doi:10.12932/AP0825.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM, et al; the National Eczema Association Task Force. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal ("steroid addiction") in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses [published online January 13, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:541.e2-549.e2.

- Belloni B, Andres C, Ollert M, et al. Novel immunological approaches in the treatment of atopic eczema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:423-427.

- McDonald BS, Jones J, Rustin M. Rituximab as a treatment for severe atopic eczema: failure to improve in three consecutive patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:45-47.

- Sánchez-Ramón S, Eguíluz-Gracia I, Rodríguez-Mazariego ME, et al. Sequential combined therapy with omalizumab and rituximab: a new approach to severe atopic dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:190-196.

- D'Erme AM, Romanelli M, Chiricozzi A. Spotlight on dupilumab in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1473-1480.

- Han Y, Chen Y, Liu X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [published online May 4, 2017]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.015.

- Simpson EL. Dupilumab improves general health-related quality-of-life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: pooled results from two randomized, controlled phase 3 clinical trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:243-248.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis [published online Sep 30, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published online May 4, 2017]. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4

A biologic medication for AD has been long overdue. Psoriatic biologic medications have been tried in AD with occasional benefit in case reports but no major response in larger trials. Belloni et al5 reviewed early data on off-label usage of biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis or other indications applied to AD patients. In their review of cases, they make the point that results are variable and anti-B-cell activity may hold the greatest promise.5 On the other hand, a recent series of 3 patients showed limited response to rituximab in chronic AD,6 while a combination of omalizumab, an anti-IgE medication, and rituximab was helpful in some patients.7 Ultimately, the issue is that nonspecific biologics may or may not address the underlying disease factors in AD. Therefore, there has been a true need for biologic intervention targeted directly at the pathogenic mechanism of AD. Furthermore, the desire for a biologic targeted at AD is paired with the true need to have a medication so targeted that the drug would have little effect on the rest of the immune system, resulting in targeted immunomodulation without secondary risk of infections.

Wait no longer, that era arrived a few months ago with the rapid US Food and Drug Administration approval of dupilumab, an injectable medication used every 2 weeks for the therapy of moderate to severe AD. This fully human monoclonal antibody against the IL-4Rα subunit blocks IL-4 and IL-13, key inflammatory agents in the triggering of production of IgE and eosinophil activation. Even better than the fact that it is targeted are the excellent outcomes in the therapy of moderate to severe AD in adults and the minimal side-effect profile resulting in no requirements for laboratory screening or ongoing monitoring.8

Dupilumab seems to perform well, both clinically and in improving the lives of AD patients. Meta-analysis of trials involving dupilumab has shown improved health-related quality of life outcomes.9,10 Usage of dupilumab alone in clinical trials for 16 weeks (SOLO 1 and SOLO 2) has resulted in stunning reduction in disease severity with a limited side-effect profile, with patients most commonly reporting conjunctivitis.11 In real-world models where dupilumab is added into a regimen of topical corticosteroid usage (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial), patients fared even better with the combination, highlighting that this medication may best be used adjunctively to our skin care guidance as dermatologists.12

A new era for AD patients has arrived and we as practitioners are now fortunate to be able to therapeutically reach the worst cases of AD. The new era has only begun with dozens of new agents addressing a variety of interleukin pathways including IL-17 and IL-22 still under development. Ultimately, we hope that ongoing pediatric trials will allow us to glean the role of early disease intervention at the root cause of AD and address our abilities to prevent comorbidities and disease persistence. Will we be able to avert years of disabling disease? The future holds immense hope.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4