User login

Neurology Reviews covers innovative and emerging news in neurology and neuroscience every month, with a focus on practical approaches to treating Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, headache, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurologic disorders.

PML

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rituxan

The leading independent newspaper covering neurology news and commentary.

Four PTSD blood biomarkers identified

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DISCOVER BMB

Lack of food for thought: Starve a bacterium, feed an infection

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

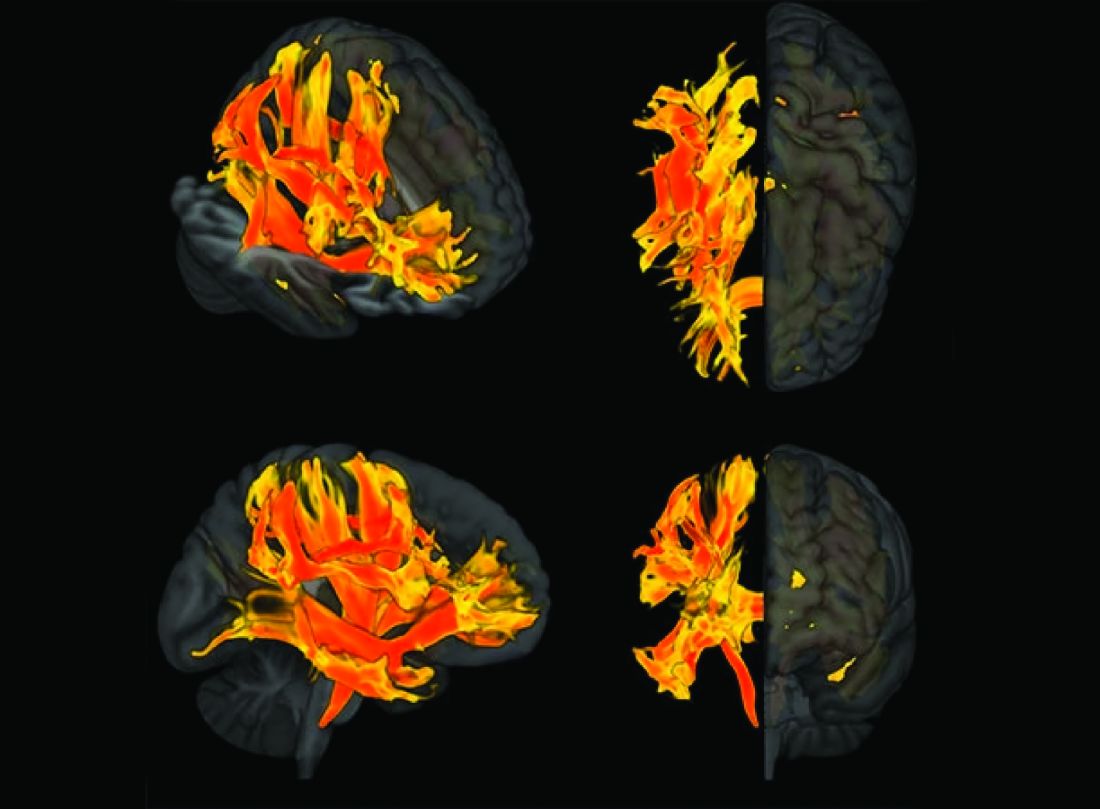

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRICS

New update on left atrial appendage closure recommendations

An updated consensus statement on transcatheter left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) has put a newfound focus on patient selection for the procedure, specifically recommending that the procedure is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who have risk for thromboembolism, aren’t well suited for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and have a good chance of living for at least another year.

The statement, published online in the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, also makes recommendations for how much experience operators should have, how many procedures they should perform to keep their skills up, and when and how to use imaging and prescribe DOACs, among other suggestions.

The statement represents the first updated guidance for LAAC since 2015. “Since then this field has really expanded and evolved,” writing group chair Jacqueline Saw, MD, said in an interview. “For instance, the indications are more matured and specific, and the procedural technical steps have matured. Imaging has also advanced, there’s more understanding about postprocedural care and there are also new devices that have been approved.”

Dr. Saw, an interventional cardiologist at Vancouver General Hospital and St. Paul’s Hospital, and a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, called the statement “a piece that puts everything together.”

“This document really summarizes the whole practice for doing transcatheter procedures,” she added, “so it’s all-in-one document in terms of recommendation of who we do the procedure for, how we should do it, how we should image and guide the procedure, and what complications to look out for and how to manage patients post procedure, be it with antithrombotic therapy and/or device surveillance.”

13 recommendations

In all, the statement carries 13 recommendations for LAAC. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions and the Heart Rhythm Society commissioned the writing group. The American College of Cardiology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography have endorsed the statement. The following are among the recommendations:

- Transcatheter LAAC is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with high thromboembolic risk but for whom long-term oral anticoagulation may be contraindicated and who have at least 1 year’s life expectancy.

- Operators should have performed at least 50 prior left-sided ablations or structural procedures and at least 25 transseptal punctures (TSPs). Interventional-imaging physicians should have experience in guiding 25 or more TSPs before supporting LAAC procedures independently.

- To maintain skills, operators should do 25 or more TSPs and at least 12 LAACs over each 2-year period.

- On-site cardiovascular surgery backup should be available for new programs and for operators early in their learning curve.

- Baseline imaging with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or cardiac computed tomography should be performed before LAAC.

- Intraprocedural imaging guidance with TEE or intracardiac echocardiography.

- Follow labeling of each specific LAAC device for technical aspects of the procedure.

- Familiarity with avoiding, recognizing, and managing LAAC complications.

- Predischarge 2-dimensional TEE to rule out pericardial effusion and device embolization.

- Anticoagulation for device-related thrombus.

- Make all efforts to minimize peridevice leaks during implantation because their clinical impact and management isn’t well understood.

- Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, DOAC, or dual-antiplatelet therapy after LAAC based on the studied regimen and instructions for each specific device, tailored to the bleeding risks for each patient.

- TEE or cardiac computed tomography at 45-90 days after LAAC for device surveillance to assess for peridevice leak and device-related thrombus.

The statement also includes precautionary recommendations. It advises against using routine closure of LAAC-associated iatrogenic atrial septal defects and states that combined procedures with LAAC, such as structural interventions and pulmonary vein isolation, should be avoided because randomized controlled trial data are pending.

“These recommendations are based upon data from updated publications and randomized trial data as well as large registries, including the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, so I think this is a very practical statement that puts all these pieces together for any budding interventionalist doing this procedure and even experienced operations,” Dr. Saw said.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agreed that the “rigorous standards” set out in the statement will help maintain “a high level of procedural safety in the setting of rapid expansion.”

The editorialists, Faisal M. Merchant, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., point out that the incidence of pericardial effusion has decreased from more than 5% in the pivotal Watchman trials to less than 1.5% in the most recent report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which shows that more than 100,000 procedures have been performed in the United States.

But most important as the field moves forward, they stress, is patient selection. The recommendation of limiting patients to those with a life expectancy of 1 year “is a tacit recognition of the fact that the benefits of LAAC take time to accrue, and many older and frail patients are unlikely to derive meaningful benefit.”

Dr. Merchant and Dr. Alkhouli also note that there remains a conundrum in patient selection that remains from the original LAAC trials, which enrolled patients who were eligible for anticoagulation. “Somewhat paradoxically, after its approval, LAAC is mostly prescribed to patients who are not felt to be good anticoagulation candidates.” This leaves physicians “in the precarious position of extrapolating data to patients who were excluded from the original clinical trials.”

Therefore, the consensus statement “is right to put patient selection front and center in its recommendations, but as the field of LAAC comes of age, better evidence to support patient selection will be the real sign of maturity.”

Dr. Saw said she envisions another update over the next 2 years or so as ongoing clinical trials comparing DOAC and LAAC, namely the CHAMPION-AF and OPTION trials, report results.

Dr. Saw and Dr. Merchant, reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alkhouli has financial ties to Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Philips.

An updated consensus statement on transcatheter left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) has put a newfound focus on patient selection for the procedure, specifically recommending that the procedure is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who have risk for thromboembolism, aren’t well suited for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and have a good chance of living for at least another year.

The statement, published online in the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, also makes recommendations for how much experience operators should have, how many procedures they should perform to keep their skills up, and when and how to use imaging and prescribe DOACs, among other suggestions.

The statement represents the first updated guidance for LAAC since 2015. “Since then this field has really expanded and evolved,” writing group chair Jacqueline Saw, MD, said in an interview. “For instance, the indications are more matured and specific, and the procedural technical steps have matured. Imaging has also advanced, there’s more understanding about postprocedural care and there are also new devices that have been approved.”

Dr. Saw, an interventional cardiologist at Vancouver General Hospital and St. Paul’s Hospital, and a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, called the statement “a piece that puts everything together.”

“This document really summarizes the whole practice for doing transcatheter procedures,” she added, “so it’s all-in-one document in terms of recommendation of who we do the procedure for, how we should do it, how we should image and guide the procedure, and what complications to look out for and how to manage patients post procedure, be it with antithrombotic therapy and/or device surveillance.”

13 recommendations

In all, the statement carries 13 recommendations for LAAC. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions and the Heart Rhythm Society commissioned the writing group. The American College of Cardiology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography have endorsed the statement. The following are among the recommendations:

- Transcatheter LAAC is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with high thromboembolic risk but for whom long-term oral anticoagulation may be contraindicated and who have at least 1 year’s life expectancy.

- Operators should have performed at least 50 prior left-sided ablations or structural procedures and at least 25 transseptal punctures (TSPs). Interventional-imaging physicians should have experience in guiding 25 or more TSPs before supporting LAAC procedures independently.

- To maintain skills, operators should do 25 or more TSPs and at least 12 LAACs over each 2-year period.

- On-site cardiovascular surgery backup should be available for new programs and for operators early in their learning curve.

- Baseline imaging with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or cardiac computed tomography should be performed before LAAC.

- Intraprocedural imaging guidance with TEE or intracardiac echocardiography.

- Follow labeling of each specific LAAC device for technical aspects of the procedure.

- Familiarity with avoiding, recognizing, and managing LAAC complications.

- Predischarge 2-dimensional TEE to rule out pericardial effusion and device embolization.

- Anticoagulation for device-related thrombus.

- Make all efforts to minimize peridevice leaks during implantation because their clinical impact and management isn’t well understood.

- Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, DOAC, or dual-antiplatelet therapy after LAAC based on the studied regimen and instructions for each specific device, tailored to the bleeding risks for each patient.

- TEE or cardiac computed tomography at 45-90 days after LAAC for device surveillance to assess for peridevice leak and device-related thrombus.

The statement also includes precautionary recommendations. It advises against using routine closure of LAAC-associated iatrogenic atrial septal defects and states that combined procedures with LAAC, such as structural interventions and pulmonary vein isolation, should be avoided because randomized controlled trial data are pending.

“These recommendations are based upon data from updated publications and randomized trial data as well as large registries, including the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, so I think this is a very practical statement that puts all these pieces together for any budding interventionalist doing this procedure and even experienced operations,” Dr. Saw said.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agreed that the “rigorous standards” set out in the statement will help maintain “a high level of procedural safety in the setting of rapid expansion.”

The editorialists, Faisal M. Merchant, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., point out that the incidence of pericardial effusion has decreased from more than 5% in the pivotal Watchman trials to less than 1.5% in the most recent report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which shows that more than 100,000 procedures have been performed in the United States.

But most important as the field moves forward, they stress, is patient selection. The recommendation of limiting patients to those with a life expectancy of 1 year “is a tacit recognition of the fact that the benefits of LAAC take time to accrue, and many older and frail patients are unlikely to derive meaningful benefit.”

Dr. Merchant and Dr. Alkhouli also note that there remains a conundrum in patient selection that remains from the original LAAC trials, which enrolled patients who were eligible for anticoagulation. “Somewhat paradoxically, after its approval, LAAC is mostly prescribed to patients who are not felt to be good anticoagulation candidates.” This leaves physicians “in the precarious position of extrapolating data to patients who were excluded from the original clinical trials.”

Therefore, the consensus statement “is right to put patient selection front and center in its recommendations, but as the field of LAAC comes of age, better evidence to support patient selection will be the real sign of maturity.”

Dr. Saw said she envisions another update over the next 2 years or so as ongoing clinical trials comparing DOAC and LAAC, namely the CHAMPION-AF and OPTION trials, report results.

Dr. Saw and Dr. Merchant, reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alkhouli has financial ties to Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Philips.

An updated consensus statement on transcatheter left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) has put a newfound focus on patient selection for the procedure, specifically recommending that the procedure is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who have risk for thromboembolism, aren’t well suited for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and have a good chance of living for at least another year.

The statement, published online in the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, also makes recommendations for how much experience operators should have, how many procedures they should perform to keep their skills up, and when and how to use imaging and prescribe DOACs, among other suggestions.

The statement represents the first updated guidance for LAAC since 2015. “Since then this field has really expanded and evolved,” writing group chair Jacqueline Saw, MD, said in an interview. “For instance, the indications are more matured and specific, and the procedural technical steps have matured. Imaging has also advanced, there’s more understanding about postprocedural care and there are also new devices that have been approved.”

Dr. Saw, an interventional cardiologist at Vancouver General Hospital and St. Paul’s Hospital, and a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, called the statement “a piece that puts everything together.”

“This document really summarizes the whole practice for doing transcatheter procedures,” she added, “so it’s all-in-one document in terms of recommendation of who we do the procedure for, how we should do it, how we should image and guide the procedure, and what complications to look out for and how to manage patients post procedure, be it with antithrombotic therapy and/or device surveillance.”

13 recommendations

In all, the statement carries 13 recommendations for LAAC. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions and the Heart Rhythm Society commissioned the writing group. The American College of Cardiology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography have endorsed the statement. The following are among the recommendations:

- Transcatheter LAAC is appropriate for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with high thromboembolic risk but for whom long-term oral anticoagulation may be contraindicated and who have at least 1 year’s life expectancy.

- Operators should have performed at least 50 prior left-sided ablations or structural procedures and at least 25 transseptal punctures (TSPs). Interventional-imaging physicians should have experience in guiding 25 or more TSPs before supporting LAAC procedures independently.

- To maintain skills, operators should do 25 or more TSPs and at least 12 LAACs over each 2-year period.

- On-site cardiovascular surgery backup should be available for new programs and for operators early in their learning curve.

- Baseline imaging with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or cardiac computed tomography should be performed before LAAC.

- Intraprocedural imaging guidance with TEE or intracardiac echocardiography.

- Follow labeling of each specific LAAC device for technical aspects of the procedure.

- Familiarity with avoiding, recognizing, and managing LAAC complications.

- Predischarge 2-dimensional TEE to rule out pericardial effusion and device embolization.

- Anticoagulation for device-related thrombus.

- Make all efforts to minimize peridevice leaks during implantation because their clinical impact and management isn’t well understood.

- Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, DOAC, or dual-antiplatelet therapy after LAAC based on the studied regimen and instructions for each specific device, tailored to the bleeding risks for each patient.

- TEE or cardiac computed tomography at 45-90 days after LAAC for device surveillance to assess for peridevice leak and device-related thrombus.

The statement also includes precautionary recommendations. It advises against using routine closure of LAAC-associated iatrogenic atrial septal defects and states that combined procedures with LAAC, such as structural interventions and pulmonary vein isolation, should be avoided because randomized controlled trial data are pending.

“These recommendations are based upon data from updated publications and randomized trial data as well as large registries, including the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, so I think this is a very practical statement that puts all these pieces together for any budding interventionalist doing this procedure and even experienced operations,” Dr. Saw said.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agreed that the “rigorous standards” set out in the statement will help maintain “a high level of procedural safety in the setting of rapid expansion.”

The editorialists, Faisal M. Merchant, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., point out that the incidence of pericardial effusion has decreased from more than 5% in the pivotal Watchman trials to less than 1.5% in the most recent report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which shows that more than 100,000 procedures have been performed in the United States.

But most important as the field moves forward, they stress, is patient selection. The recommendation of limiting patients to those with a life expectancy of 1 year “is a tacit recognition of the fact that the benefits of LAAC take time to accrue, and many older and frail patients are unlikely to derive meaningful benefit.”

Dr. Merchant and Dr. Alkhouli also note that there remains a conundrum in patient selection that remains from the original LAAC trials, which enrolled patients who were eligible for anticoagulation. “Somewhat paradoxically, after its approval, LAAC is mostly prescribed to patients who are not felt to be good anticoagulation candidates.” This leaves physicians “in the precarious position of extrapolating data to patients who were excluded from the original clinical trials.”

Therefore, the consensus statement “is right to put patient selection front and center in its recommendations, but as the field of LAAC comes of age, better evidence to support patient selection will be the real sign of maturity.”

Dr. Saw said she envisions another update over the next 2 years or so as ongoing clinical trials comparing DOAC and LAAC, namely the CHAMPION-AF and OPTION trials, report results.

Dr. Saw and Dr. Merchant, reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alkhouli has financial ties to Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Philips.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR CARDIOVASCULAR ANGIOGRAPHY & INTERVENTIONS

Kidney disease skews Alzheimer’s biomarker testing

New research provides more evidence that

In a cross-sectional study of adults with and those without cognitive impairment, chronic kidney disease was associated with increased plasma concentrations of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 217 and 181.

However, there were no associations between chronic kidney disease and the ratio of p-tau217 to unphosphorylated tau 217 (pT217/T217), and the associations with p-tau181 to unphosphorylated tau 181 (pT181/T181) were attenuated in patients with cognitive impairment.

“These novel findings suggest that plasma measures of the phosphorylated to unphosphorylated tau ratios are more accurate than p-tau forms alone as they correlate less with individual difference in glomerular filtration rate or impaired kidney function,” reported an investigative team led by Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, with Lund University in Sweden.

“Thus, to mitigate the effects of non-Alzheimer’s–related comorbidities like chronic kidney disease on the performance of plasma Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, certain tau ratios, and specifically pT217/T217, should be considered for implementation in clinical practice and drug trials,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology to coincide with a presentation at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Skewed tau levels

Plasma biomarkers of amyloid-beta (Abeta) and tau pathologies, and in particular variants in p-tau217 and p-tau181, have shown promise for use in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and prognosis. However, previous reports have suggested that chronic kidney disease might influence plasma p-tau217 and p-tau181 concentrations, potentially decreasing their usefulness in the diagnostic workup of dementia.

Researchers investigated associations of chronic kidney disease with plasma ratios of p-tau217 and p-tau181 to the corresponding unphosphorylated peptides in Alzheimer’s disease.

The data came from 473 older adults, with and without cognitive impairment, from the Swedish BioFinder-2 study who had plasma tau assessments and chronic kidney disease status established within 6 months of plasma collection.

The researchers found that lower estimated glomerular filtration rate levels (indicative of kidney dysfunction) were associated with higher plasma concentrations of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated tau peptides measured simultaneously using the tau immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry assay.

However, the correlations with estimated glomerular filtration rate were nonsignificant for the pT217/T217 ratio in individuals with cognitive impairment and were significantly attenuated for pT217/T217 in cognitively unimpaired individuals and for pT181/T181 in both cognitively unimpaired and impaired individuals.

“Importantly, we demonstrate that there were no significant associations between chronic kidney disease and the pT217/T217 ratio and changes in plasma pT181/T181 associated with chronic kidney disease were small or nonsignificant,” the researchers noted.

“Our results indicate that by using p-tau/tau ratios we may be able to reduce the variability in plasma p-tau levels driven by impaired kidney function and consequently such ratios are more robust measures of brain p-tau pathology in individuals with both early- and later-stage Alzheimer’s disease,” they added.

The researchers believe this is likely true for the ratios of other related proteins – a view that is supported by findings of attenuated associations of chronic kidney disease with Abeta42/40, compared with Abeta42 and Abeta40 in the current study and in previous studies.

Important clinical implications

Reached for comment, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific engagement, noted that research continues to indicate that blood biomarkers have “promise for improving, and possibly even redefining, the clinical workup for Alzheimer’s disease.

“Many of the Alzheimer’s blood tests in development today have focused on core blood biomarkers associated with amyloid accumulation and tau tangle formation in the brain,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

“Before these tests can be used more broadly in the clinic, we need to understand all of the variables that may impact the results of various blood biomarkers, including differences that may be driven by race, ethnicity, sex, and underlying health conditions, such as chronic kidney disease.

“This study corroborates other research suggesting that some Alzheimer’s-associated markers can be affected by chronic kidney disease, but by using ratios of amyloid or tau markers, we may be able to minimize these differences in results caused by underlying disease,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, said, “Using these ratios makes a lot of sense because the ratios wouldn’t change with kidney function. I think this is an important advance in clinical utilization of these tests.”

Dr. Fillit noted that older people often have declining kidney function, which can be easily measured by glomerular filtration rate. Changes in blood levels of these markers with declining kidney function are “not unexpected, but [it’s] important that it’s been demonstrated.

“As we go forward, maybe the future utilization of these tests will be not only recording the ratios but also reporting the ratios in the context of somebody’s glomerular filtration rate. You could imagine a scenario where when the test is done, it’s automatically done alongside of glomerular filtration rate,” Dr. Fillit said in an interview.

The study was supported by Coins for Alzheimer’s Research Trust, the Tracy Family Stable Isotope Labeling Quantitation Center, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Hansson has received support to his institution from ADx, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, Pfizer, and Roche; consultancy/speaker fees from Amylyx, Alzpath, Biogen, Cerveau, Fujirebio, Genentech, Novartis, Roche, and Siemens; and personal fees from Eli Lilly, Eisai, Bioarctic, and Biogen outside the submitted work. Dr. Edelmayer and Dr. Fillit have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides more evidence that

In a cross-sectional study of adults with and those without cognitive impairment, chronic kidney disease was associated with increased plasma concentrations of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 217 and 181.

However, there were no associations between chronic kidney disease and the ratio of p-tau217 to unphosphorylated tau 217 (pT217/T217), and the associations with p-tau181 to unphosphorylated tau 181 (pT181/T181) were attenuated in patients with cognitive impairment.

“These novel findings suggest that plasma measures of the phosphorylated to unphosphorylated tau ratios are more accurate than p-tau forms alone as they correlate less with individual difference in glomerular filtration rate or impaired kidney function,” reported an investigative team led by Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, with Lund University in Sweden.

“Thus, to mitigate the effects of non-Alzheimer’s–related comorbidities like chronic kidney disease on the performance of plasma Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, certain tau ratios, and specifically pT217/T217, should be considered for implementation in clinical practice and drug trials,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology to coincide with a presentation at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Skewed tau levels

Plasma biomarkers of amyloid-beta (Abeta) and tau pathologies, and in particular variants in p-tau217 and p-tau181, have shown promise for use in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and prognosis. However, previous reports have suggested that chronic kidney disease might influence plasma p-tau217 and p-tau181 concentrations, potentially decreasing their usefulness in the diagnostic workup of dementia.

Researchers investigated associations of chronic kidney disease with plasma ratios of p-tau217 and p-tau181 to the corresponding unphosphorylated peptides in Alzheimer’s disease.

The data came from 473 older adults, with and without cognitive impairment, from the Swedish BioFinder-2 study who had plasma tau assessments and chronic kidney disease status established within 6 months of plasma collection.

The researchers found that lower estimated glomerular filtration rate levels (indicative of kidney dysfunction) were associated with higher plasma concentrations of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated tau peptides measured simultaneously using the tau immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry assay.

However, the correlations with estimated glomerular filtration rate were nonsignificant for the pT217/T217 ratio in individuals with cognitive impairment and were significantly attenuated for pT217/T217 in cognitively unimpaired individuals and for pT181/T181 in both cognitively unimpaired and impaired individuals.

“Importantly, we demonstrate that there were no significant associations between chronic kidney disease and the pT217/T217 ratio and changes in plasma pT181/T181 associated with chronic kidney disease were small or nonsignificant,” the researchers noted.

“Our results indicate that by using p-tau/tau ratios we may be able to reduce the variability in plasma p-tau levels driven by impaired kidney function and consequently such ratios are more robust measures of brain p-tau pathology in individuals with both early- and later-stage Alzheimer’s disease,” they added.

The researchers believe this is likely true for the ratios of other related proteins – a view that is supported by findings of attenuated associations of chronic kidney disease with Abeta42/40, compared with Abeta42 and Abeta40 in the current study and in previous studies.

Important clinical implications

Reached for comment, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific engagement, noted that research continues to indicate that blood biomarkers have “promise for improving, and possibly even redefining, the clinical workup for Alzheimer’s disease.

“Many of the Alzheimer’s blood tests in development today have focused on core blood biomarkers associated with amyloid accumulation and tau tangle formation in the brain,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

“Before these tests can be used more broadly in the clinic, we need to understand all of the variables that may impact the results of various blood biomarkers, including differences that may be driven by race, ethnicity, sex, and underlying health conditions, such as chronic kidney disease.

“This study corroborates other research suggesting that some Alzheimer’s-associated markers can be affected by chronic kidney disease, but by using ratios of amyloid or tau markers, we may be able to minimize these differences in results caused by underlying disease,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, said, “Using these ratios makes a lot of sense because the ratios wouldn’t change with kidney function. I think this is an important advance in clinical utilization of these tests.”

Dr. Fillit noted that older people often have declining kidney function, which can be easily measured by glomerular filtration rate. Changes in blood levels of these markers with declining kidney function are “not unexpected, but [it’s] important that it’s been demonstrated.

“As we go forward, maybe the future utilization of these tests will be not only recording the ratios but also reporting the ratios in the context of somebody’s glomerular filtration rate. You could imagine a scenario where when the test is done, it’s automatically done alongside of glomerular filtration rate,” Dr. Fillit said in an interview.

The study was supported by Coins for Alzheimer’s Research Trust, the Tracy Family Stable Isotope Labeling Quantitation Center, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Hansson has received support to his institution from ADx, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, Pfizer, and Roche; consultancy/speaker fees from Amylyx, Alzpath, Biogen, Cerveau, Fujirebio, Genentech, Novartis, Roche, and Siemens; and personal fees from Eli Lilly, Eisai, Bioarctic, and Biogen outside the submitted work. Dr. Edelmayer and Dr. Fillit have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides more evidence that

In a cross-sectional study of adults with and those without cognitive impairment, chronic kidney disease was associated with increased plasma concentrations of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 217 and 181.

However, there were no associations between chronic kidney disease and the ratio of p-tau217 to unphosphorylated tau 217 (pT217/T217), and the associations with p-tau181 to unphosphorylated tau 181 (pT181/T181) were attenuated in patients with cognitive impairment.

“These novel findings suggest that plasma measures of the phosphorylated to unphosphorylated tau ratios are more accurate than p-tau forms alone as they correlate less with individual difference in glomerular filtration rate or impaired kidney function,” reported an investigative team led by Oskar Hansson, MD, PhD, with Lund University in Sweden.

“Thus, to mitigate the effects of non-Alzheimer’s–related comorbidities like chronic kidney disease on the performance of plasma Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, certain tau ratios, and specifically pT217/T217, should be considered for implementation in clinical practice and drug trials,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology to coincide with a presentation at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Skewed tau levels