User login

Investigators studied more than 6,000 cognitively healthy individuals, aged 40-73, and found that those who consumed more than 550 mg of magnesium daily had a brain age approximately 1 year younger by age 55 years, compared with a person who consumed a normal magnesium intake (~360 mg per day).

“This research highlights the potential benefits of a diet high in magnesium and the role it plays in promoting good brain health,” lead author Khawlah Alateeq, a PhD candidate in neuroscience at Australian National University’s National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, said in an interview.

Clinicians “can use [the findings] to counsel patients on the benefits of increasing magnesium intake through a healthy diet and monitoring magnesium levels to prevent deficiencies,” she stated.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Nutrition.

Promising target

The researchers were motivated to conduct the study because of “the growing concern over the increasing prevalence of dementia,” Ms. Alateeq said.

“Since there is no cure for dementia, and the development of pharmacological treatment for dementia has been unsuccessful over the last 30 years, prevention has been suggested as an effective approach to address the issue,” she added.

Nutrition, Ms. Alateeq said, is a “modifiable risk factor that can influence brain health and is highly amenable to scalable and cost-effective interventions.” It represents “a promising target” for risk reduction at a population level.

Previous research shows individuals with lower magnesium levels are at higher risk for AD, while those with higher dietary magnesium intake may be at lower risk of progressing from normal aging to cognitive impairment.

Most previous studies, however, included participants older than age 60 years, and it’s “unclear when the neuroprotective effects of dietary magnesium become detectable,” the researchers note.

Moreover, dietary patterns change and fluctuate, potentially leading to changes in magnesium intake over time. These changes may have as much impact as absolute magnesium at any point in time.

In light of the “current lack of understanding of when and to what extent dietary magnesium exerts its protective effects on the brain,” the researchers examined the association between magnesium trajectories over time, brain matter, and white matter lesions.

They also examined the association between magnesium and several different blood pressure measures (mean arterial pressure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure).

Since cardiovascular health, neurodegeneration, and brain shrinkage patterns differ between men and women, the researchers stratified their analyses by sex.

Brain volume differences

The researchers analyzed the dietary magnesium intake of 6,001 individuals (mean age, 55.3 years) selected from the UK Biobank – a prospective cohort study of participants aged 37-73 at baseline, who were assessed between 2005 and 2023.

For the current study, only participants with baseline DBP and SBP measurements and structural MRI scans were included. Participants were also required to be free of neurologic disorders and to have an available record of dietary magnesium intake.

Covariates included age, sex, education, health conditions, smoking status, body mass index, amount of physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Over a 16-month period, participants completed an online questionnaire five times. Their responses were used to calculate daily magnesium intake. Foods of particular interest included leafy green vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, all of which are magnesium rich.

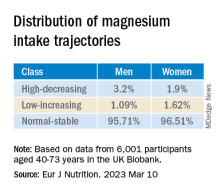

They used latent class analysis (LCA) to “identify mutually exclusive subgroup (classes) of magnesium intake trajectory separately for men and women.”

Men had a slightly higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with women, and postmenopausal women had a higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with premenopausal women.

Compared with lower baseline magnesium intake, higher baseline dietary intake of magnesium was associated with larger brain volumes in several regions in both men and women.

The latent class analysis identified three classes of magnesium intake:

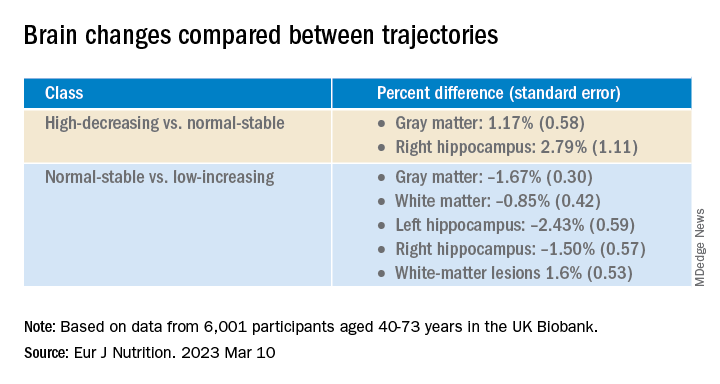

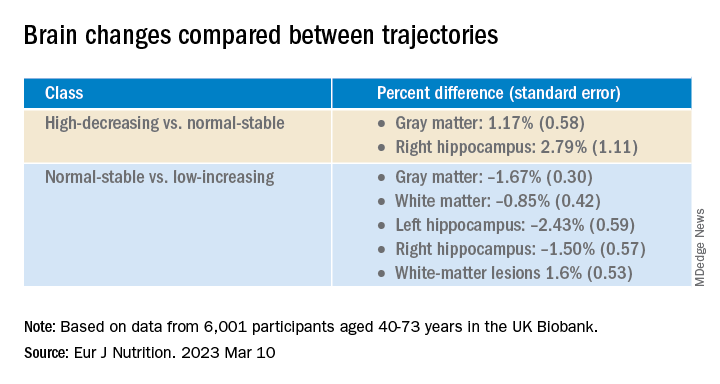

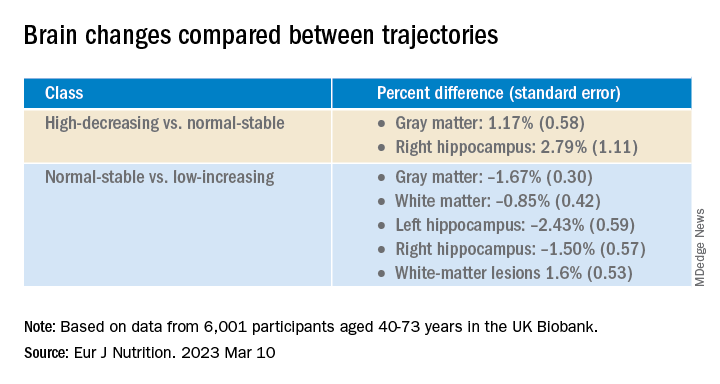

In women in particular, the “high-decreasing” trajectory was significantly associated with larger brain volumes, compared with the “normal-stable” trajectory, while the “low-increasing” trajectory was associated with smaller brain volumes.

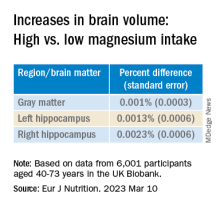

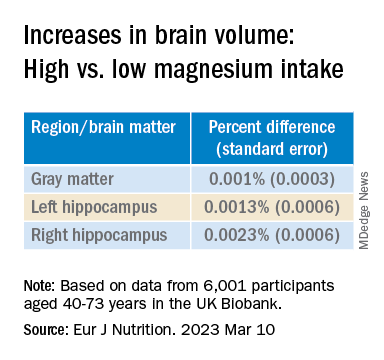

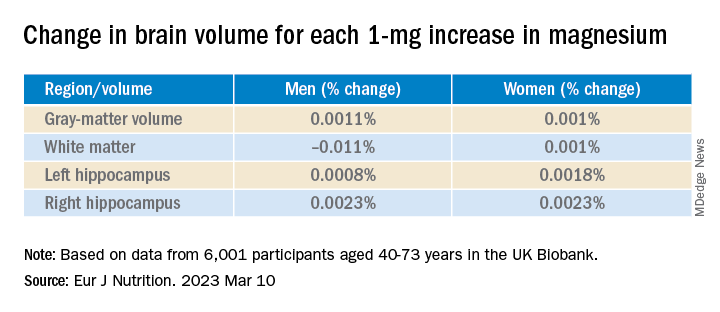

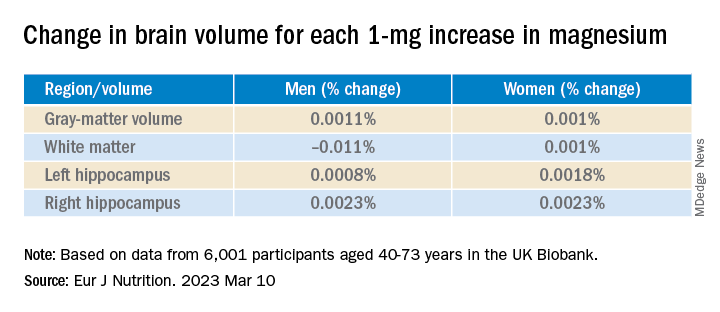

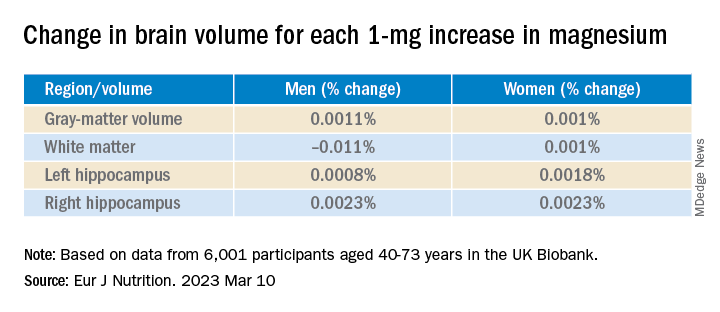

Even an increase of 1 mg of magnesium per day (above 350 mg/day) made a difference in brain volume, especially in women. The changes associated with every 1-mg increase are found in the table below:

Associations between magnesium and BP measures were “mostly nonsignificant,” the researchers say, and the neuroprotective effect of higher magnesium intake in the high-decreasing trajectory was greater in postmenopausal versus premenopausal women.

“Our models indicate that compared to somebody with a normal magnesium intake (~350 mg per day), somebody in the top quartile of magnesium intake (≥ 550 mg per day) would be predicted to have a ~0.20% larger GM and ~0.46% larger RHC,” the authors summarize.

“In a population with an average age of 55 years, this effect corresponds to ~1 year of typical aging,” they note. “In other words, if this effect is generalizable to other populations, a 41% increase in magnesium intake may lead to significantly better brain health.”

Although the exact mechanisms underlying magnesium’s protective effects are “not yet clearly understood, there’s considerable evidence that magnesium levels are related to better cardiovascular health. Magnesium supplementation has been found to decrease blood pressure – and high blood pressure is a well-established risk factor for dementia,” said Ms. Alateeq.

Association, not causation

Yuko Hara, PhD, director of Aging and Prevention, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the study is observational and therefore shows an association, not causation.

“People eating a high-magnesium diet may also be eating a brain-healthy diet and getting high levels of nutrients/minerals other than magnesium alone,” suggested Dr. Hara, who was not involved with the study.

She noted that many foods are good sources of magnesium, including spinach, almonds, cashews, legumes, yogurt, brown rice, and avocados.

“Eating a brain-healthy diet (for example, the Mediterranean diet) is one of the Seven Steps to Protect Your Cognitive Vitality that ADDF’s Cognitive Vitality promotes,” she said.

Open Access funding was enabled and organized by the Council of Australian University Librarians and its Member Institutions. Ms. Alateeq, her co-authors, and Dr. Hara declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied more than 6,000 cognitively healthy individuals, aged 40-73, and found that those who consumed more than 550 mg of magnesium daily had a brain age approximately 1 year younger by age 55 years, compared with a person who consumed a normal magnesium intake (~360 mg per day).

“This research highlights the potential benefits of a diet high in magnesium and the role it plays in promoting good brain health,” lead author Khawlah Alateeq, a PhD candidate in neuroscience at Australian National University’s National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, said in an interview.

Clinicians “can use [the findings] to counsel patients on the benefits of increasing magnesium intake through a healthy diet and monitoring magnesium levels to prevent deficiencies,” she stated.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Nutrition.

Promising target

The researchers were motivated to conduct the study because of “the growing concern over the increasing prevalence of dementia,” Ms. Alateeq said.

“Since there is no cure for dementia, and the development of pharmacological treatment for dementia has been unsuccessful over the last 30 years, prevention has been suggested as an effective approach to address the issue,” she added.

Nutrition, Ms. Alateeq said, is a “modifiable risk factor that can influence brain health and is highly amenable to scalable and cost-effective interventions.” It represents “a promising target” for risk reduction at a population level.

Previous research shows individuals with lower magnesium levels are at higher risk for AD, while those with higher dietary magnesium intake may be at lower risk of progressing from normal aging to cognitive impairment.

Most previous studies, however, included participants older than age 60 years, and it’s “unclear when the neuroprotective effects of dietary magnesium become detectable,” the researchers note.

Moreover, dietary patterns change and fluctuate, potentially leading to changes in magnesium intake over time. These changes may have as much impact as absolute magnesium at any point in time.

In light of the “current lack of understanding of when and to what extent dietary magnesium exerts its protective effects on the brain,” the researchers examined the association between magnesium trajectories over time, brain matter, and white matter lesions.

They also examined the association between magnesium and several different blood pressure measures (mean arterial pressure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure).

Since cardiovascular health, neurodegeneration, and brain shrinkage patterns differ between men and women, the researchers stratified their analyses by sex.

Brain volume differences

The researchers analyzed the dietary magnesium intake of 6,001 individuals (mean age, 55.3 years) selected from the UK Biobank – a prospective cohort study of participants aged 37-73 at baseline, who were assessed between 2005 and 2023.

For the current study, only participants with baseline DBP and SBP measurements and structural MRI scans were included. Participants were also required to be free of neurologic disorders and to have an available record of dietary magnesium intake.

Covariates included age, sex, education, health conditions, smoking status, body mass index, amount of physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Over a 16-month period, participants completed an online questionnaire five times. Their responses were used to calculate daily magnesium intake. Foods of particular interest included leafy green vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, all of which are magnesium rich.

They used latent class analysis (LCA) to “identify mutually exclusive subgroup (classes) of magnesium intake trajectory separately for men and women.”

Men had a slightly higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with women, and postmenopausal women had a higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with premenopausal women.

Compared with lower baseline magnesium intake, higher baseline dietary intake of magnesium was associated with larger brain volumes in several regions in both men and women.

The latent class analysis identified three classes of magnesium intake:

In women in particular, the “high-decreasing” trajectory was significantly associated with larger brain volumes, compared with the “normal-stable” trajectory, while the “low-increasing” trajectory was associated with smaller brain volumes.

Even an increase of 1 mg of magnesium per day (above 350 mg/day) made a difference in brain volume, especially in women. The changes associated with every 1-mg increase are found in the table below:

Associations between magnesium and BP measures were “mostly nonsignificant,” the researchers say, and the neuroprotective effect of higher magnesium intake in the high-decreasing trajectory was greater in postmenopausal versus premenopausal women.

“Our models indicate that compared to somebody with a normal magnesium intake (~350 mg per day), somebody in the top quartile of magnesium intake (≥ 550 mg per day) would be predicted to have a ~0.20% larger GM and ~0.46% larger RHC,” the authors summarize.

“In a population with an average age of 55 years, this effect corresponds to ~1 year of typical aging,” they note. “In other words, if this effect is generalizable to other populations, a 41% increase in magnesium intake may lead to significantly better brain health.”

Although the exact mechanisms underlying magnesium’s protective effects are “not yet clearly understood, there’s considerable evidence that magnesium levels are related to better cardiovascular health. Magnesium supplementation has been found to decrease blood pressure – and high blood pressure is a well-established risk factor for dementia,” said Ms. Alateeq.

Association, not causation

Yuko Hara, PhD, director of Aging and Prevention, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the study is observational and therefore shows an association, not causation.

“People eating a high-magnesium diet may also be eating a brain-healthy diet and getting high levels of nutrients/minerals other than magnesium alone,” suggested Dr. Hara, who was not involved with the study.

She noted that many foods are good sources of magnesium, including spinach, almonds, cashews, legumes, yogurt, brown rice, and avocados.

“Eating a brain-healthy diet (for example, the Mediterranean diet) is one of the Seven Steps to Protect Your Cognitive Vitality that ADDF’s Cognitive Vitality promotes,” she said.

Open Access funding was enabled and organized by the Council of Australian University Librarians and its Member Institutions. Ms. Alateeq, her co-authors, and Dr. Hara declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied more than 6,000 cognitively healthy individuals, aged 40-73, and found that those who consumed more than 550 mg of magnesium daily had a brain age approximately 1 year younger by age 55 years, compared with a person who consumed a normal magnesium intake (~360 mg per day).

“This research highlights the potential benefits of a diet high in magnesium and the role it plays in promoting good brain health,” lead author Khawlah Alateeq, a PhD candidate in neuroscience at Australian National University’s National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, said in an interview.

Clinicians “can use [the findings] to counsel patients on the benefits of increasing magnesium intake through a healthy diet and monitoring magnesium levels to prevent deficiencies,” she stated.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Nutrition.

Promising target

The researchers were motivated to conduct the study because of “the growing concern over the increasing prevalence of dementia,” Ms. Alateeq said.

“Since there is no cure for dementia, and the development of pharmacological treatment for dementia has been unsuccessful over the last 30 years, prevention has been suggested as an effective approach to address the issue,” she added.

Nutrition, Ms. Alateeq said, is a “modifiable risk factor that can influence brain health and is highly amenable to scalable and cost-effective interventions.” It represents “a promising target” for risk reduction at a population level.

Previous research shows individuals with lower magnesium levels are at higher risk for AD, while those with higher dietary magnesium intake may be at lower risk of progressing from normal aging to cognitive impairment.

Most previous studies, however, included participants older than age 60 years, and it’s “unclear when the neuroprotective effects of dietary magnesium become detectable,” the researchers note.

Moreover, dietary patterns change and fluctuate, potentially leading to changes in magnesium intake over time. These changes may have as much impact as absolute magnesium at any point in time.

In light of the “current lack of understanding of when and to what extent dietary magnesium exerts its protective effects on the brain,” the researchers examined the association between magnesium trajectories over time, brain matter, and white matter lesions.

They also examined the association between magnesium and several different blood pressure measures (mean arterial pressure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure).

Since cardiovascular health, neurodegeneration, and brain shrinkage patterns differ between men and women, the researchers stratified their analyses by sex.

Brain volume differences

The researchers analyzed the dietary magnesium intake of 6,001 individuals (mean age, 55.3 years) selected from the UK Biobank – a prospective cohort study of participants aged 37-73 at baseline, who were assessed between 2005 and 2023.

For the current study, only participants with baseline DBP and SBP measurements and structural MRI scans were included. Participants were also required to be free of neurologic disorders and to have an available record of dietary magnesium intake.

Covariates included age, sex, education, health conditions, smoking status, body mass index, amount of physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Over a 16-month period, participants completed an online questionnaire five times. Their responses were used to calculate daily magnesium intake. Foods of particular interest included leafy green vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, all of which are magnesium rich.

They used latent class analysis (LCA) to “identify mutually exclusive subgroup (classes) of magnesium intake trajectory separately for men and women.”

Men had a slightly higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with women, and postmenopausal women had a higher prevalence of BP medication and diabetes, compared with premenopausal women.

Compared with lower baseline magnesium intake, higher baseline dietary intake of magnesium was associated with larger brain volumes in several regions in both men and women.

The latent class analysis identified three classes of magnesium intake:

In women in particular, the “high-decreasing” trajectory was significantly associated with larger brain volumes, compared with the “normal-stable” trajectory, while the “low-increasing” trajectory was associated with smaller brain volumes.

Even an increase of 1 mg of magnesium per day (above 350 mg/day) made a difference in brain volume, especially in women. The changes associated with every 1-mg increase are found in the table below:

Associations between magnesium and BP measures were “mostly nonsignificant,” the researchers say, and the neuroprotective effect of higher magnesium intake in the high-decreasing trajectory was greater in postmenopausal versus premenopausal women.

“Our models indicate that compared to somebody with a normal magnesium intake (~350 mg per day), somebody in the top quartile of magnesium intake (≥ 550 mg per day) would be predicted to have a ~0.20% larger GM and ~0.46% larger RHC,” the authors summarize.

“In a population with an average age of 55 years, this effect corresponds to ~1 year of typical aging,” they note. “In other words, if this effect is generalizable to other populations, a 41% increase in magnesium intake may lead to significantly better brain health.”

Although the exact mechanisms underlying magnesium’s protective effects are “not yet clearly understood, there’s considerable evidence that magnesium levels are related to better cardiovascular health. Magnesium supplementation has been found to decrease blood pressure – and high blood pressure is a well-established risk factor for dementia,” said Ms. Alateeq.

Association, not causation

Yuko Hara, PhD, director of Aging and Prevention, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the study is observational and therefore shows an association, not causation.

“People eating a high-magnesium diet may also be eating a brain-healthy diet and getting high levels of nutrients/minerals other than magnesium alone,” suggested Dr. Hara, who was not involved with the study.

She noted that many foods are good sources of magnesium, including spinach, almonds, cashews, legumes, yogurt, brown rice, and avocados.

“Eating a brain-healthy diet (for example, the Mediterranean diet) is one of the Seven Steps to Protect Your Cognitive Vitality that ADDF’s Cognitive Vitality promotes,” she said.

Open Access funding was enabled and organized by the Council of Australian University Librarians and its Member Institutions. Ms. Alateeq, her co-authors, and Dr. Hara declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF NUTRITION