User login

Neurology Reviews covers innovative and emerging news in neurology and neuroscience every month, with a focus on practical approaches to treating Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, headache, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurologic disorders.

PML

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rituxan

The leading independent newspaper covering neurology news and commentary.

Mississippi–Ohio River valley linked to higher risk of Parkinson’s disease

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

according to findings from a study that was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The association was attributed to concentrations of particulate matter (PM) 2.5 in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, which was on average higher than in other areas, but that didn’t entirely explain the increase in Parkinson’s disease in that region, Brittany Krzyzanowski, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the neuroepidemiology research program of the department of neurology at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, said in an interview.

“This study revealed Parkinson’s disease hot spots in the Mississippi–Ohio River valley, a region that has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the nation,” she said, “but we also still find a relationship between air pollution and Parkinson’s risk in the regions in the western half of the United States where Parkinson’s disease and air pollution levels are relatively low.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski and colleagues evaluated 22,546,965 Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, using a multimethod approach that included geospatial analytical techniques to categorize their exposure to PM2.5 based on age, sex, race, smoking status, and health care usage. The researchers also performed individual-level case-control analysis to assess PM2.5 results at the county level. The Medicare beneficiaries were grouped according to average exposure, with the lowest group having an average annual exposure of 5 mcg/m3 and the group with the highest exposure having an average annual exposure of 19 mcg/m3.

In total, researchers identified 83,674 Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson’s disease, with 434 new cases per 100,000 people in the highest exposure group, compared with 359 new cases per 100,000 people in the lowest-exposure group. The relative risk for Parkinson’s disease increased in the highest quartile of PM2.5 by 25%, compared with the lowest quartile after adjusting for factors such as age, smoking status, and health care usage (95% confidence interval, 20%–29%).

The results showed the nationwide average annual PM2.5 was associated with incident Parkinson’s disease, and the Rocky Mountain region carried a strong association between PM2.5 and Parkson’s disease with a 16% increase in risk per level of exposure to PM2.5. While the Mississippi-Ohio River valley was also associated with Parkinson’s disease, there was a weaker association between PM2.5 and Parkinson’s disease, which the researchers attributed to a “ceiling effect” of PM2.5 between approximately 12-19 mcg/m3.

Dr. Krzyzanowski said that use of a large-population-based dataset and high-resolution location data were major strengths of the study. “Having this level of information leaves less room for uncertainty in our measures and analyses,” she said. “Our study also leveraged innovative geographic information systems which allowed us to refine local patterns of disease by using population behavior and demographic information (such as smoking and age) to ensure that we could provide the most accurate map representation available to date.”

A focus on air pollution

Existing research in examining the etiology of Parkinson’s mainly focused on exposure to pesticides,* Dr. Krzyzanowski explained, and “consists of studies using relatively small populations and low-resolution air pollution data.” Genetics is another possible cause, she noted, but only explains some Parkinson’s disease cases.

“Our work suggests that we should also be looking at air pollution as a contributor in the development of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

Ray Dorsey, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who was not involved with the study, said that evidence is mounting that “air pollution may be an important causal factor in Parkinson’s and especially Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This study by a well-regarded group of researchers adds epidemiological evidence for that association,” he said. Another strength is that the study was conducted in the United States, as many epidemiological studies evaluating air pollution and Parkinson’s disease have been performed outside the country because of “a dearth of reliable data sources.”

“This study, along with others, suggest that some of the important environmental toxicants tied to brain disease may be inhaled,” Dr. Dorsey said. “The nose may be the front door to the brain.”

Dr. Krzyzanowski said the next step in their research is further examination of different types of air pollution. “Air pollution contains a variety of toxic components which vary from region to region. Understanding the different components in air pollution and how they interact with climate, temperature, and topography could help explain the regional differences we observed.”

One potential limitation in the study is a lag between air pollution exposure and development of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Dorsey noted.

“Here, it looks like (but I am not certain) that the investigators looked at current air pollution levels and new cases of Parkinson’s. Ideally, for incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, we would want to know historical data on exposure to air pollution,” he said.

Future studies should include prospective evaluation of adults as well as babies and children who have been exposed to both high and low levels of air pollution. That kind of study “would be incredibly valuable for determining the role of an important environmental toxicant in many brain diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s,” he said.

Dr. Krzyzanowski and Dr. Dorsey reported no relevant financial disclosures. This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

*Correction, 4/14/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the disease that was the subject of this research.

FROM AAN 2023

Seven ‘simple’ cardiovascular health measures linked to reduced dementia risk in women

according to results of a study that was released early, ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Epidemiologist Pamela M. Rist, ScD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and associate epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues, used data from 13,720 women whose mean age was 54 when they enrolled in the Harvard-based Women’s Health Study between 1992 and 1995. Subjects in that study were followed up in 2004.

Putting ‘Life’s Simple 7’ to the test

Dr. Rist and colleagues used the Harvard data to discern how well closely women conformed, during the initial study period and at 10-year follow up, to what the American Heart Association describes as “Life’s Simple 7,” a list of behavioral and biometric measures that indicate and predict cardiovascular health. The measures include four modifiable behaviors – not smoking, healthy weight, a healthy diet, and being physically active – along with three biometric measures of blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar (AHA has since added a sleep component).

Researchers assigned women one point for each desirable habit or measure on the list, with subjects’ average Simple 7 score at baseline 4.3, and 4.2 at 10 years’ follow-up.

The investigators then looked at Medicare data for the study subjects from 2011 to 2018 – approximately 20 years after their enrollment in the Women’s Health Study – seeking dementia diagnoses. Some 13% of the study cohort (n = 1,771) had gone on to develop dementia.

Each point on the Simple 7 score at baseline corresponded with a 6% reduction in later dementia risk, Dr. Rist and her colleagues found after adjusting for variables including age and education (odds ratio per one unit change in score, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90-0.98). This effect was similar for Simple 7 scores measured at 10 years of follow-up (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91-1.00).

“It can be empowering for people to know that by taking steps such as exercising for a half an hour a day or keeping their blood pressure under control, they can reduce their risk of dementia,” Dr. Rist said in a statement on the findings.

‘A simple take-home message’

Reached for comment, Andrew E. Budson, MD, chief of cognitive-behavioral neurology at the VA Boston Healthcare System, praised Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study as one that “builds on existing knowledge to provide a simple take-home message that empowers women to take control of their dementia risk.”

Each of the seven known risk factors – being active, eating better, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking, maintaining a healthy blood pressure, controlling cholesterol, and having low blood sugar – “was associated with a 6% reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Budson continued. “So, women who work to address all seven risk factors can reduce their risk of developing dementia by 42%: a huge amount. Moreover, although this study only looked at women, I am confident that if men follow this same advice they will also be able to reduce their risk of dementia, although we don’t know if the size of the effect will be the same.”

Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest. Dr. Budson has reported receiving past compensation as a speaker for Eli Lilly.

according to results of a study that was released early, ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Epidemiologist Pamela M. Rist, ScD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and associate epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues, used data from 13,720 women whose mean age was 54 when they enrolled in the Harvard-based Women’s Health Study between 1992 and 1995. Subjects in that study were followed up in 2004.

Putting ‘Life’s Simple 7’ to the test

Dr. Rist and colleagues used the Harvard data to discern how well closely women conformed, during the initial study period and at 10-year follow up, to what the American Heart Association describes as “Life’s Simple 7,” a list of behavioral and biometric measures that indicate and predict cardiovascular health. The measures include four modifiable behaviors – not smoking, healthy weight, a healthy diet, and being physically active – along with three biometric measures of blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar (AHA has since added a sleep component).

Researchers assigned women one point for each desirable habit or measure on the list, with subjects’ average Simple 7 score at baseline 4.3, and 4.2 at 10 years’ follow-up.

The investigators then looked at Medicare data for the study subjects from 2011 to 2018 – approximately 20 years after their enrollment in the Women’s Health Study – seeking dementia diagnoses. Some 13% of the study cohort (n = 1,771) had gone on to develop dementia.

Each point on the Simple 7 score at baseline corresponded with a 6% reduction in later dementia risk, Dr. Rist and her colleagues found after adjusting for variables including age and education (odds ratio per one unit change in score, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90-0.98). This effect was similar for Simple 7 scores measured at 10 years of follow-up (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91-1.00).

“It can be empowering for people to know that by taking steps such as exercising for a half an hour a day or keeping their blood pressure under control, they can reduce their risk of dementia,” Dr. Rist said in a statement on the findings.

‘A simple take-home message’

Reached for comment, Andrew E. Budson, MD, chief of cognitive-behavioral neurology at the VA Boston Healthcare System, praised Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study as one that “builds on existing knowledge to provide a simple take-home message that empowers women to take control of their dementia risk.”

Each of the seven known risk factors – being active, eating better, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking, maintaining a healthy blood pressure, controlling cholesterol, and having low blood sugar – “was associated with a 6% reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Budson continued. “So, women who work to address all seven risk factors can reduce their risk of developing dementia by 42%: a huge amount. Moreover, although this study only looked at women, I am confident that if men follow this same advice they will also be able to reduce their risk of dementia, although we don’t know if the size of the effect will be the same.”

Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest. Dr. Budson has reported receiving past compensation as a speaker for Eli Lilly.

according to results of a study that was released early, ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Epidemiologist Pamela M. Rist, ScD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and associate epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues, used data from 13,720 women whose mean age was 54 when they enrolled in the Harvard-based Women’s Health Study between 1992 and 1995. Subjects in that study were followed up in 2004.

Putting ‘Life’s Simple 7’ to the test

Dr. Rist and colleagues used the Harvard data to discern how well closely women conformed, during the initial study period and at 10-year follow up, to what the American Heart Association describes as “Life’s Simple 7,” a list of behavioral and biometric measures that indicate and predict cardiovascular health. The measures include four modifiable behaviors – not smoking, healthy weight, a healthy diet, and being physically active – along with three biometric measures of blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar (AHA has since added a sleep component).

Researchers assigned women one point for each desirable habit or measure on the list, with subjects’ average Simple 7 score at baseline 4.3, and 4.2 at 10 years’ follow-up.

The investigators then looked at Medicare data for the study subjects from 2011 to 2018 – approximately 20 years after their enrollment in the Women’s Health Study – seeking dementia diagnoses. Some 13% of the study cohort (n = 1,771) had gone on to develop dementia.

Each point on the Simple 7 score at baseline corresponded with a 6% reduction in later dementia risk, Dr. Rist and her colleagues found after adjusting for variables including age and education (odds ratio per one unit change in score, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90-0.98). This effect was similar for Simple 7 scores measured at 10 years of follow-up (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91-1.00).

“It can be empowering for people to know that by taking steps such as exercising for a half an hour a day or keeping their blood pressure under control, they can reduce their risk of dementia,” Dr. Rist said in a statement on the findings.

‘A simple take-home message’

Reached for comment, Andrew E. Budson, MD, chief of cognitive-behavioral neurology at the VA Boston Healthcare System, praised Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study as one that “builds on existing knowledge to provide a simple take-home message that empowers women to take control of their dementia risk.”

Each of the seven known risk factors – being active, eating better, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking, maintaining a healthy blood pressure, controlling cholesterol, and having low blood sugar – “was associated with a 6% reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Budson continued. “So, women who work to address all seven risk factors can reduce their risk of developing dementia by 42%: a huge amount. Moreover, although this study only looked at women, I am confident that if men follow this same advice they will also be able to reduce their risk of dementia, although we don’t know if the size of the effect will be the same.”

Dr. Rist and colleagues’ study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest. Dr. Budson has reported receiving past compensation as a speaker for Eli Lilly.

FROM AAN 2023

Helping a patient buck the odds

I’m not going to get rich off Mike.

Of course, I’m not going to get rich off anyone, nor do I want to. I’m not here to rip anyone off.

Mike goes back with me, roughly 23 years.

He was born with cerebral palsy and refractory seizures. His birth mother gave him up quickly, and he was adopted by a couple who knew what they were getting into (to me that constitutes sainthood).

Over the years Mike has done his best to buck the odds. He’s tried to stay employed, in spite of his physical limitations, working variously as a janitor, grocery courtesy clerk, and store greeter. He tells me that he can still work and wants to, even with having to rely on public transportation.

By the time he came to me he’d been through several neurologists and even more failed epilepsy drugs. His brain MRI and EEGs showed multifocal seizures from numerous inoperable cortical heterotopias.

I dabbled with a few newer drugs at the time for him, without success. Finally, I reached for the neurological equivalent of unstable dynamite – Felbatol (felbamate).

As it often does, it worked. One of my attendings in training (you, Bob) told me it was the home-run drug. When nothing else worked, it might – but you had to handle it carefully.

Fortunately, after 23 years, that hasn’t happened. Mike’s labs have looked good. His seizures have dropped from several a week to a few per year.

Ten years ago Mike had to change insurance to one I don’t take, and had me forward his records to another neurologist. That office told him they don’t handle Felbatol. As did another. And another.

Mike, understandably, doesn’t want to change meds. This is the only drug that’s given him a decent quality of life, and let him have a job. That’s pretty important to him.

So, I see him for free now, once or twice a year. Sometimes he offers me a token payment of $5-$10, but I turn it down. He needs it more than I do, for bus fair to my office if nothing else.

I’m sure some would be critical of me, saying that I should be more open to new drugs and treatments. I am, believe me. But Mike can’t afford many of them, or the loss of work they’d entail if his seizures worsen. He doesn’t want to take that chance, and I don’t blame him.

Of course, none of us can see everyone for free. In fact, he’s the only one I do. I’m not greedy, but I also have to pay my rent, staff, and mortgage.

But taking money from Mike, who’s come up on the short end of the stick in so many ways, doesn’t seem right. I can’t do it, and really don’t want to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m not going to get rich off Mike.

Of course, I’m not going to get rich off anyone, nor do I want to. I’m not here to rip anyone off.

Mike goes back with me, roughly 23 years.

He was born with cerebral palsy and refractory seizures. His birth mother gave him up quickly, and he was adopted by a couple who knew what they were getting into (to me that constitutes sainthood).

Over the years Mike has done his best to buck the odds. He’s tried to stay employed, in spite of his physical limitations, working variously as a janitor, grocery courtesy clerk, and store greeter. He tells me that he can still work and wants to, even with having to rely on public transportation.

By the time he came to me he’d been through several neurologists and even more failed epilepsy drugs. His brain MRI and EEGs showed multifocal seizures from numerous inoperable cortical heterotopias.

I dabbled with a few newer drugs at the time for him, without success. Finally, I reached for the neurological equivalent of unstable dynamite – Felbatol (felbamate).

As it often does, it worked. One of my attendings in training (you, Bob) told me it was the home-run drug. When nothing else worked, it might – but you had to handle it carefully.

Fortunately, after 23 years, that hasn’t happened. Mike’s labs have looked good. His seizures have dropped from several a week to a few per year.

Ten years ago Mike had to change insurance to one I don’t take, and had me forward his records to another neurologist. That office told him they don’t handle Felbatol. As did another. And another.

Mike, understandably, doesn’t want to change meds. This is the only drug that’s given him a decent quality of life, and let him have a job. That’s pretty important to him.

So, I see him for free now, once or twice a year. Sometimes he offers me a token payment of $5-$10, but I turn it down. He needs it more than I do, for bus fair to my office if nothing else.

I’m sure some would be critical of me, saying that I should be more open to new drugs and treatments. I am, believe me. But Mike can’t afford many of them, or the loss of work they’d entail if his seizures worsen. He doesn’t want to take that chance, and I don’t blame him.

Of course, none of us can see everyone for free. In fact, he’s the only one I do. I’m not greedy, but I also have to pay my rent, staff, and mortgage.

But taking money from Mike, who’s come up on the short end of the stick in so many ways, doesn’t seem right. I can’t do it, and really don’t want to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m not going to get rich off Mike.

Of course, I’m not going to get rich off anyone, nor do I want to. I’m not here to rip anyone off.

Mike goes back with me, roughly 23 years.

He was born with cerebral palsy and refractory seizures. His birth mother gave him up quickly, and he was adopted by a couple who knew what they were getting into (to me that constitutes sainthood).

Over the years Mike has done his best to buck the odds. He’s tried to stay employed, in spite of his physical limitations, working variously as a janitor, grocery courtesy clerk, and store greeter. He tells me that he can still work and wants to, even with having to rely on public transportation.

By the time he came to me he’d been through several neurologists and even more failed epilepsy drugs. His brain MRI and EEGs showed multifocal seizures from numerous inoperable cortical heterotopias.

I dabbled with a few newer drugs at the time for him, without success. Finally, I reached for the neurological equivalent of unstable dynamite – Felbatol (felbamate).

As it often does, it worked. One of my attendings in training (you, Bob) told me it was the home-run drug. When nothing else worked, it might – but you had to handle it carefully.

Fortunately, after 23 years, that hasn’t happened. Mike’s labs have looked good. His seizures have dropped from several a week to a few per year.

Ten years ago Mike had to change insurance to one I don’t take, and had me forward his records to another neurologist. That office told him they don’t handle Felbatol. As did another. And another.

Mike, understandably, doesn’t want to change meds. This is the only drug that’s given him a decent quality of life, and let him have a job. That’s pretty important to him.

So, I see him for free now, once or twice a year. Sometimes he offers me a token payment of $5-$10, but I turn it down. He needs it more than I do, for bus fair to my office if nothing else.

I’m sure some would be critical of me, saying that I should be more open to new drugs and treatments. I am, believe me. But Mike can’t afford many of them, or the loss of work they’d entail if his seizures worsen. He doesn’t want to take that chance, and I don’t blame him.

Of course, none of us can see everyone for free. In fact, he’s the only one I do. I’m not greedy, but I also have to pay my rent, staff, and mortgage.

But taking money from Mike, who’s come up on the short end of the stick in so many ways, doesn’t seem right. I can’t do it, and really don’t want to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Study gives new insight into timing of combo treatment in metastatic NSCLC

However, patients still fared poorly on average since overall survival remained low and didn’t change significantly.

While not conclusive, the new research – released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023 – offers early insight into the best timing for the experimental combination treatment, study coauthor Yanyan Lou, MD, PhD, an oncologist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., said in an interview.

The wide availability of radiation therapy could also allow the therapy to be administered even in regions with poor access to sophisticated medical care, she said. “Radiation is a very feasible approach that pretty much everybody in your community can get.”

Radiotherapy is typically not added to immunotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. But “there has been recent interest in the combination: Would tumor necrosis from radiation enhance the immunogenicity of the tumor and thus enhance the effect of immunotherapy?” oncologist Toby Campbell, MD, of University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Research has indeed suggested that the treatments may have a synergistic effect, he said, and it’s clear that “strategies to try and increase immunogenicity are an important area to investigate.”

But he cautioned that “we have a long way to go to understanding how immunogenicity works and how the gut microbiome, tumor, immunotherapy, and the immune system interact with one another.”

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed cases of 225 patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (male = 56%, median age = 68, 79% adenocarcinoma) who were treated with immunotherapy at Mayo Clinic–Jacksonville from 2011 to 2022. The study excluded those who received targeted therapy or prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy and durvalumab.

The most common metastases were bone and central nervous system types (41% and 25%, respectively). Fifty-six percent of patients received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy. Another 27% never received radiotherapy, and 17% received it after immunotherapy was discontinued.

Common types of immunotherapy included pembrolizumab (78%), nivolumab (14%), and atezolizumab (12%).

Overall, the researchers found no statistically significant differences in various outcomes between patients who received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy compared with those who didn’t get radiotherapy (progression-free survival: 5.9 vs. 5.5 months, P = .66; overall survival: 16.9 vs. 13.1 months, P = .84; immune-related adverse events: 26.2% vs. 34.4%, P = .24).

However, the researchers found that progression-free survival was significantly higher in one group: Those who received radiotherapy 1-12 months before immunotherapy vs. those who received it less than 1 month before (12.6 vs. 4.2 months, hazard ratio [HR], 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.83, P = .005,) and those who never received radiotherapy (12.6 vs. 5.5 months, HR, 0.56, 95% CI, 0.36-0.89, P = .0197).

There wasn’t a statistically significant difference in overall survival.

The small number of subjects and the variation in treatment protocols may have prevented the study from revealing a survival benefit, Dr. Lou said.

As for adverse effects, she said a preliminary analysis didn’t turn up any.

It’s not clear why a 1- to 12-month gap between radiotherapy and immunotherapy may be most effective, she said. Moving forward, “we need validate this in a large cohort,” she noted.

In regard to cost, immunotherapy is notoriously expensive. Pembrolizumab, for example, has a list price of $10,897 per 200-mg dose given every 3 weeks, and patients may take the drug for a year or two.

Dr. Campbell, who didn’t take part in the new study, said it suggests that research into radiation-immunotherapy combination treatment may be worthwhile.

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Campbell reported no disclosures.

However, patients still fared poorly on average since overall survival remained low and didn’t change significantly.

While not conclusive, the new research – released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023 – offers early insight into the best timing for the experimental combination treatment, study coauthor Yanyan Lou, MD, PhD, an oncologist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., said in an interview.

The wide availability of radiation therapy could also allow the therapy to be administered even in regions with poor access to sophisticated medical care, she said. “Radiation is a very feasible approach that pretty much everybody in your community can get.”

Radiotherapy is typically not added to immunotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. But “there has been recent interest in the combination: Would tumor necrosis from radiation enhance the immunogenicity of the tumor and thus enhance the effect of immunotherapy?” oncologist Toby Campbell, MD, of University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Research has indeed suggested that the treatments may have a synergistic effect, he said, and it’s clear that “strategies to try and increase immunogenicity are an important area to investigate.”

But he cautioned that “we have a long way to go to understanding how immunogenicity works and how the gut microbiome, tumor, immunotherapy, and the immune system interact with one another.”

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed cases of 225 patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (male = 56%, median age = 68, 79% adenocarcinoma) who were treated with immunotherapy at Mayo Clinic–Jacksonville from 2011 to 2022. The study excluded those who received targeted therapy or prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy and durvalumab.

The most common metastases were bone and central nervous system types (41% and 25%, respectively). Fifty-six percent of patients received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy. Another 27% never received radiotherapy, and 17% received it after immunotherapy was discontinued.

Common types of immunotherapy included pembrolizumab (78%), nivolumab (14%), and atezolizumab (12%).

Overall, the researchers found no statistically significant differences in various outcomes between patients who received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy compared with those who didn’t get radiotherapy (progression-free survival: 5.9 vs. 5.5 months, P = .66; overall survival: 16.9 vs. 13.1 months, P = .84; immune-related adverse events: 26.2% vs. 34.4%, P = .24).

However, the researchers found that progression-free survival was significantly higher in one group: Those who received radiotherapy 1-12 months before immunotherapy vs. those who received it less than 1 month before (12.6 vs. 4.2 months, hazard ratio [HR], 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.83, P = .005,) and those who never received radiotherapy (12.6 vs. 5.5 months, HR, 0.56, 95% CI, 0.36-0.89, P = .0197).

There wasn’t a statistically significant difference in overall survival.

The small number of subjects and the variation in treatment protocols may have prevented the study from revealing a survival benefit, Dr. Lou said.

As for adverse effects, she said a preliminary analysis didn’t turn up any.

It’s not clear why a 1- to 12-month gap between radiotherapy and immunotherapy may be most effective, she said. Moving forward, “we need validate this in a large cohort,” she noted.

In regard to cost, immunotherapy is notoriously expensive. Pembrolizumab, for example, has a list price of $10,897 per 200-mg dose given every 3 weeks, and patients may take the drug for a year or two.

Dr. Campbell, who didn’t take part in the new study, said it suggests that research into radiation-immunotherapy combination treatment may be worthwhile.

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Campbell reported no disclosures.

However, patients still fared poorly on average since overall survival remained low and didn’t change significantly.

While not conclusive, the new research – released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023 – offers early insight into the best timing for the experimental combination treatment, study coauthor Yanyan Lou, MD, PhD, an oncologist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., said in an interview.

The wide availability of radiation therapy could also allow the therapy to be administered even in regions with poor access to sophisticated medical care, she said. “Radiation is a very feasible approach that pretty much everybody in your community can get.”

Radiotherapy is typically not added to immunotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. But “there has been recent interest in the combination: Would tumor necrosis from radiation enhance the immunogenicity of the tumor and thus enhance the effect of immunotherapy?” oncologist Toby Campbell, MD, of University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Research has indeed suggested that the treatments may have a synergistic effect, he said, and it’s clear that “strategies to try and increase immunogenicity are an important area to investigate.”

But he cautioned that “we have a long way to go to understanding how immunogenicity works and how the gut microbiome, tumor, immunotherapy, and the immune system interact with one another.”

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed cases of 225 patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (male = 56%, median age = 68, 79% adenocarcinoma) who were treated with immunotherapy at Mayo Clinic–Jacksonville from 2011 to 2022. The study excluded those who received targeted therapy or prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy and durvalumab.

The most common metastases were bone and central nervous system types (41% and 25%, respectively). Fifty-six percent of patients received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy. Another 27% never received radiotherapy, and 17% received it after immunotherapy was discontinued.

Common types of immunotherapy included pembrolizumab (78%), nivolumab (14%), and atezolizumab (12%).

Overall, the researchers found no statistically significant differences in various outcomes between patients who received radiotherapy before or during immunotherapy compared with those who didn’t get radiotherapy (progression-free survival: 5.9 vs. 5.5 months, P = .66; overall survival: 16.9 vs. 13.1 months, P = .84; immune-related adverse events: 26.2% vs. 34.4%, P = .24).

However, the researchers found that progression-free survival was significantly higher in one group: Those who received radiotherapy 1-12 months before immunotherapy vs. those who received it less than 1 month before (12.6 vs. 4.2 months, hazard ratio [HR], 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.83, P = .005,) and those who never received radiotherapy (12.6 vs. 5.5 months, HR, 0.56, 95% CI, 0.36-0.89, P = .0197).

There wasn’t a statistically significant difference in overall survival.

The small number of subjects and the variation in treatment protocols may have prevented the study from revealing a survival benefit, Dr. Lou said.

As for adverse effects, she said a preliminary analysis didn’t turn up any.

It’s not clear why a 1- to 12-month gap between radiotherapy and immunotherapy may be most effective, she said. Moving forward, “we need validate this in a large cohort,” she noted.

In regard to cost, immunotherapy is notoriously expensive. Pembrolizumab, for example, has a list price of $10,897 per 200-mg dose given every 3 weeks, and patients may take the drug for a year or two.

Dr. Campbell, who didn’t take part in the new study, said it suggests that research into radiation-immunotherapy combination treatment may be worthwhile.

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Campbell reported no disclosures.

FROM ELCC 2023

First target doesn’t affect survival in NSCLC with brain metastases

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

FROM ELCC 2023

New guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management released

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANNABIS AND CANNABINOID RESEARCH

Picking up the premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

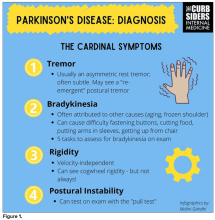

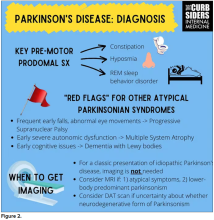

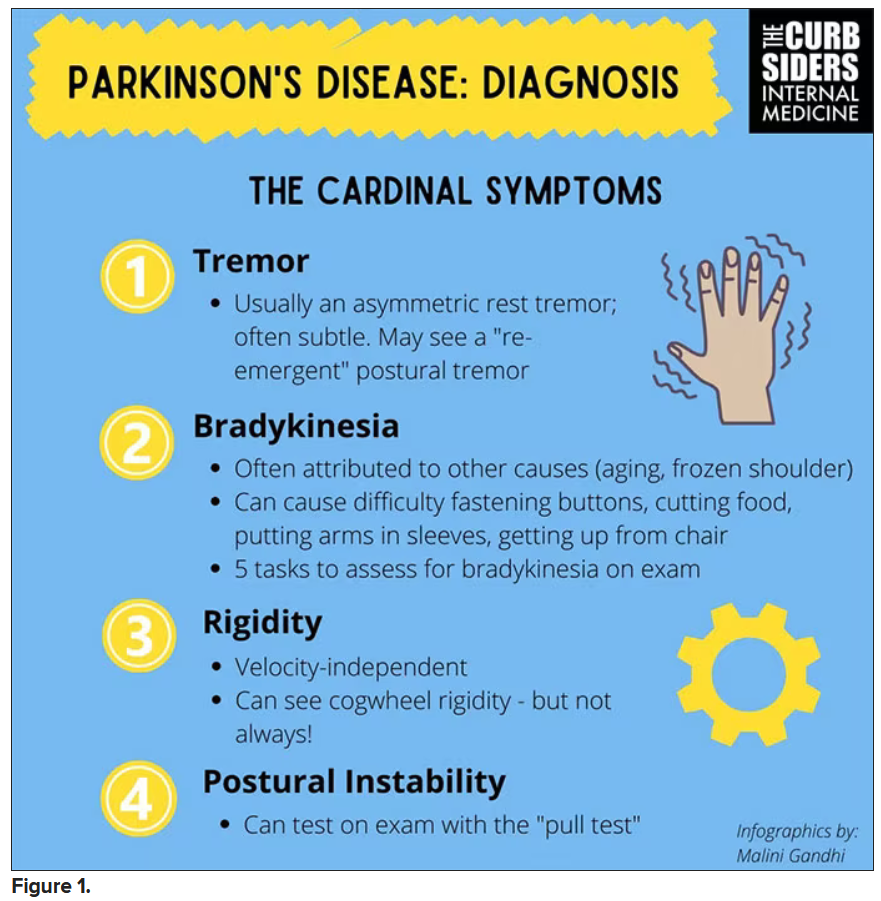

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.