User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Bite-sized bouts of exercise: Why they are valuable and what they are missing

Short bursts of activity are approximately as effective for general health as longer sessions, especially for those who are mainly sedentary, according to several recently published studies.

If your fitness goals are greater, and you want to build muscle strength and endurance, compete in a 5K, or just look better in your swimsuit, you will need to do more. But for basic health, it appears that short bursts can help, the new research papers and experts suggest.

“Whether you accumulate activity in many short bouts versus one extended bout, the general health benefits tend to be similar,” Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, said in an interview.

Current public health recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest doing at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week for health benefits, but this activity can be accumulated in any way over the week, she noted. Previous versions of the CDC guidelines on exercise suggested that physical activity bouts should be at least 10 minutes each, but the latest version of the guidelines acknowledges that bursts of less than 10 minutes may be beneficial.

However, “the activity or fitness level at which someone starts and the specific health goals matter,” Dr. Paluch continued. “Short bouts may be particularly beneficial for those least active to get moving more to improve their general wellness.”

The current federal physical activity guidelines are still worth striving for, and patients can work their way to this goal, accumulating 150 or more minutes in a way that works best for them, she added.

“There is a lack of research directly comparing individuals who consistently accumulate their activity in many short bouts versus single bouts over an extended period of time,” Dr. Paluch noted. From a public health perspective, since both short and long bouts have health benefits, the best physical activity is what fits into your life and helps build a lifelong habit.

The benefits of exercise for cardiovascular health are well documented. A review from Circulation published in 2003 summarized the benefits of regular physical activity on measures of cardiovascular health including reduction in body weight, blood pressure, and bad cholesterol, while increasing insulin sensitivity, good cholesterol, and muscular strength and function. In that review, author Jonathan N. Myers, PhD, now of Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that “one need not be a marathon runner or an elite athlete to derive significant benefits from physical activity.” In fact, “the greatest gains in terms of mortality are achieved when an individual goes from being sedentary to becoming moderately active.”

A recent large, population-based study showed the value of short bursts of exercise for those previously sedentary. In this study, published in Nature Medicine, a team in Australia used wearable fitness trackers to measure the health benefits of what researchers have named “vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity” or VILPA.

Some examples of VILPA include power walking on the way to work, climbing stairs, or even running around with your kids on the playground.

Specifically, individuals who engaged in the median VILPA frequency of three bursts of vigorous activity lasting 1-2 minutes showed a 38%-40% reduction in all-cause mortality risk and cancer mortality risk, and a 48%-49% reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk.

The researchers repeated their analysis for a group of 62,344 adults from the UK Biobank who reported regular vigorous physical activity (VPA). They found similar effects on mortality, based on 1,552 deaths reported.

These results suggest that VILPA may be a reasonable physical activity target, especially for people not able or willing to exercise more formally or intensely, the researchers noted.

“We have known for a long time that leisure-time exercise often reaches vigorous intensity and has many health benefits, but we understand less about the health potential of daily movement, especially activities done as part of daily living that reach vigorous intensity,” lead author Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, professor of physical activity, lifestyle and population health at the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, said in an interview.

“As long as the heart rate goes up for a minute or 2 it will likely be vigorous activity,” Dr. Stamatakis said in an interview. “It is also important that clinicians effectively communicate how patients can know that they are reaching vigorous intensity,” he said.

Signs of vigorous intensity include increased heart rate and getting out of breath after about 20-40 seconds from the start of the VILPA burst. After about a minute of VILPA, the person doing it should be too out of breath to speak more than a few words comfortably, he said.

Data support value of any and all exercise

The Nature Medicine study supports other recent research showing the value of short, intense bursts of physical activity. A pair of recent studies also used fitness trackers to measure activity in adults and assess the benefits on outcomes including death and heart disease.

One of these studies, which was published in the European Heart Journal, also used fitness trackers to measure physical activity at moderate and vigorous levels. The researchers found that individuals who performed at least 20% of their physical activity at a moderate to high level, such as by doing brisk walking in lieu of strolling had a significantly lower risk of heart disease than those whose daily activity included less than 20% at a moderate or intense level.

In another study from the European Heart Journal, researchers found that short bursts of vigorous physical activity of 2 minutes or less adding up to 15-20 minutes per week was enough to reduce mortality by as much as 40%.

Plus, a meta-analysis published in the Lancet showed a decrease in all-cause mortality with an increase in the number of daily steps, although the impact of stepping rate on mortality was inconsistent.

“Many studies have investigated the health benefits of physical activity, but not the importance of these difficult-to-capture VILPA bouts that accrue during the course of normal activities of daily living,” Lee Stoner, PhD, an exercise physiologist and director of the Cardiometabolic Lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr. Stoner, who was not involved in the Nature Medicine study, said he was not surprised by the overall finding that doing short bursts of activity impacted mortality and cardiovascular disease, but was slightly surprised by the strength of the evidence.

“The referent group in the Nature Medicine study were those accruing no VILPA”, likely meaning they were very inactive,” Dr. Stoner said and added that he thinks this demonstrates the value of VILPA.

Even without immediately meeting the specific numbers recommended by the CDC, “any physical activity is better than none, especially if vigorous, and VILPA can be built into normal daily routines,” Dr. Stoner added.

What’s missing in short bursts?

Short bursts of activity do have their limits when it comes to overall fitness, said Dr. Stoner.

“Endurance will not be improved as much through short bursts, because such activities are unlikely to be as effective at empowering the mitochondria – the batteries keeping our cells running, including skeletal muscle cells,” he said. “Additionally, the vigorous bouts are unlikely to be as effective at improving muscular strength and endurance. For this, it is recommended that we engage each muscle group in strengthening exercises two times per week.”

However, Dr. Stoner agreed that prescribing short bursts of intense activity as part of daily living may be a great way to get people started with exercise.

“The key is to remove barriers to physical activity pursuit, then focusing on long-term routine rather than short-term gain,” he said. “Individuals are better served if they focus on goals other than weight loss, for which physical activity or exercise may not be the solution. Rather, being physically active can improve vigor, make daily activities simpler, and improve cognitive abilities,” and any physical activity is one of the most effective solutions for regulating blood glucose levels and improving cardiovascular risk factors.

Make it routine – and fun

To benefit from physical activity, cultivating and sustaining a long-term routine is key, said Dr. Stoner, whose research has focused on sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease. Whatever the activity is, shorter bursts, or longer bouts or both, it is essential that individuals figure out activities that they enjoy if they want to create sustained behavior, and thus health change, Gabriel Zieff, MA, a doctoral candidate in Dr. Stoner’s Cardiometabolic Lab, who conducts studies on exercise, noted in an interview.

“We exercise enthusiasts and researchers are often hyperfocused on whether this duration or that duration is better, whether this intensity or that intensity is better,” but at the end of the day, it is the enjoyment factor that often predicts sustained behavior change, and should be part of discussions with patients to help reduce sedentary behavior and promote activity, Mr. Zieff said.

Short bouts can encourage hesitant exercisers

“To best support health, clinicians should consider taking a few seconds to ask patients about their physical activity levels,” said Dr. Paluch, who was the lead author on the Lancet meta-analysis of daily steps. In that study, Dr. Paluch and colleagues found that taking more steps each day was associated with a progressively lower risk of all-cause mortality. However, that study did not measure step rate.

Clinicians can emphasize that health benefits do not require an hour-long exercise routine and special equipment, and moving more, even in shorts bursts of activity can have meaningful associations with health, particularly for those who are less active, she said.

The recent studies on short bursts of activity agree that “some physical activity is better than none and adults should move more throughout the day in whatever way makes sense to them and fits best into their lives,” said Dr. Paluch. “For example, opting for the stairs instead of the elevator, a brisk walk to the bus stop, a short game of hide and seek with the children or grandchildren – anything that gets your body moving more, even if briefly. Making simple lifestyle changes is often easier in small bites. In time, this can grow into long-term habits, ultimately leading to an overall active lifestyle that supports living healthier for longer.”

The Nature Medicine study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Several coauthors were supported by the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Novo Nordisk, the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, the Alan Turing Institute, the British Heart Foundation, and Health Data Research UK, an initiative funded by UK Research and Innovation. Dr. Paluch and Dr. Stoner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Short bursts of activity are approximately as effective for general health as longer sessions, especially for those who are mainly sedentary, according to several recently published studies.

If your fitness goals are greater, and you want to build muscle strength and endurance, compete in a 5K, or just look better in your swimsuit, you will need to do more. But for basic health, it appears that short bursts can help, the new research papers and experts suggest.

“Whether you accumulate activity in many short bouts versus one extended bout, the general health benefits tend to be similar,” Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, said in an interview.

Current public health recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest doing at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week for health benefits, but this activity can be accumulated in any way over the week, she noted. Previous versions of the CDC guidelines on exercise suggested that physical activity bouts should be at least 10 minutes each, but the latest version of the guidelines acknowledges that bursts of less than 10 minutes may be beneficial.

However, “the activity or fitness level at which someone starts and the specific health goals matter,” Dr. Paluch continued. “Short bouts may be particularly beneficial for those least active to get moving more to improve their general wellness.”

The current federal physical activity guidelines are still worth striving for, and patients can work their way to this goal, accumulating 150 or more minutes in a way that works best for them, she added.

“There is a lack of research directly comparing individuals who consistently accumulate their activity in many short bouts versus single bouts over an extended period of time,” Dr. Paluch noted. From a public health perspective, since both short and long bouts have health benefits, the best physical activity is what fits into your life and helps build a lifelong habit.

The benefits of exercise for cardiovascular health are well documented. A review from Circulation published in 2003 summarized the benefits of regular physical activity on measures of cardiovascular health including reduction in body weight, blood pressure, and bad cholesterol, while increasing insulin sensitivity, good cholesterol, and muscular strength and function. In that review, author Jonathan N. Myers, PhD, now of Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that “one need not be a marathon runner or an elite athlete to derive significant benefits from physical activity.” In fact, “the greatest gains in terms of mortality are achieved when an individual goes from being sedentary to becoming moderately active.”

A recent large, population-based study showed the value of short bursts of exercise for those previously sedentary. In this study, published in Nature Medicine, a team in Australia used wearable fitness trackers to measure the health benefits of what researchers have named “vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity” or VILPA.

Some examples of VILPA include power walking on the way to work, climbing stairs, or even running around with your kids on the playground.

Specifically, individuals who engaged in the median VILPA frequency of three bursts of vigorous activity lasting 1-2 minutes showed a 38%-40% reduction in all-cause mortality risk and cancer mortality risk, and a 48%-49% reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk.

The researchers repeated their analysis for a group of 62,344 adults from the UK Biobank who reported regular vigorous physical activity (VPA). They found similar effects on mortality, based on 1,552 deaths reported.

These results suggest that VILPA may be a reasonable physical activity target, especially for people not able or willing to exercise more formally or intensely, the researchers noted.

“We have known for a long time that leisure-time exercise often reaches vigorous intensity and has many health benefits, but we understand less about the health potential of daily movement, especially activities done as part of daily living that reach vigorous intensity,” lead author Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, professor of physical activity, lifestyle and population health at the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, said in an interview.

“As long as the heart rate goes up for a minute or 2 it will likely be vigorous activity,” Dr. Stamatakis said in an interview. “It is also important that clinicians effectively communicate how patients can know that they are reaching vigorous intensity,” he said.

Signs of vigorous intensity include increased heart rate and getting out of breath after about 20-40 seconds from the start of the VILPA burst. After about a minute of VILPA, the person doing it should be too out of breath to speak more than a few words comfortably, he said.

Data support value of any and all exercise

The Nature Medicine study supports other recent research showing the value of short, intense bursts of physical activity. A pair of recent studies also used fitness trackers to measure activity in adults and assess the benefits on outcomes including death and heart disease.

One of these studies, which was published in the European Heart Journal, also used fitness trackers to measure physical activity at moderate and vigorous levels. The researchers found that individuals who performed at least 20% of their physical activity at a moderate to high level, such as by doing brisk walking in lieu of strolling had a significantly lower risk of heart disease than those whose daily activity included less than 20% at a moderate or intense level.

In another study from the European Heart Journal, researchers found that short bursts of vigorous physical activity of 2 minutes or less adding up to 15-20 minutes per week was enough to reduce mortality by as much as 40%.

Plus, a meta-analysis published in the Lancet showed a decrease in all-cause mortality with an increase in the number of daily steps, although the impact of stepping rate on mortality was inconsistent.

“Many studies have investigated the health benefits of physical activity, but not the importance of these difficult-to-capture VILPA bouts that accrue during the course of normal activities of daily living,” Lee Stoner, PhD, an exercise physiologist and director of the Cardiometabolic Lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr. Stoner, who was not involved in the Nature Medicine study, said he was not surprised by the overall finding that doing short bursts of activity impacted mortality and cardiovascular disease, but was slightly surprised by the strength of the evidence.

“The referent group in the Nature Medicine study were those accruing no VILPA”, likely meaning they were very inactive,” Dr. Stoner said and added that he thinks this demonstrates the value of VILPA.

Even without immediately meeting the specific numbers recommended by the CDC, “any physical activity is better than none, especially if vigorous, and VILPA can be built into normal daily routines,” Dr. Stoner added.

What’s missing in short bursts?

Short bursts of activity do have their limits when it comes to overall fitness, said Dr. Stoner.

“Endurance will not be improved as much through short bursts, because such activities are unlikely to be as effective at empowering the mitochondria – the batteries keeping our cells running, including skeletal muscle cells,” he said. “Additionally, the vigorous bouts are unlikely to be as effective at improving muscular strength and endurance. For this, it is recommended that we engage each muscle group in strengthening exercises two times per week.”

However, Dr. Stoner agreed that prescribing short bursts of intense activity as part of daily living may be a great way to get people started with exercise.

“The key is to remove barriers to physical activity pursuit, then focusing on long-term routine rather than short-term gain,” he said. “Individuals are better served if they focus on goals other than weight loss, for which physical activity or exercise may not be the solution. Rather, being physically active can improve vigor, make daily activities simpler, and improve cognitive abilities,” and any physical activity is one of the most effective solutions for regulating blood glucose levels and improving cardiovascular risk factors.

Make it routine – and fun

To benefit from physical activity, cultivating and sustaining a long-term routine is key, said Dr. Stoner, whose research has focused on sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease. Whatever the activity is, shorter bursts, or longer bouts or both, it is essential that individuals figure out activities that they enjoy if they want to create sustained behavior, and thus health change, Gabriel Zieff, MA, a doctoral candidate in Dr. Stoner’s Cardiometabolic Lab, who conducts studies on exercise, noted in an interview.

“We exercise enthusiasts and researchers are often hyperfocused on whether this duration or that duration is better, whether this intensity or that intensity is better,” but at the end of the day, it is the enjoyment factor that often predicts sustained behavior change, and should be part of discussions with patients to help reduce sedentary behavior and promote activity, Mr. Zieff said.

Short bouts can encourage hesitant exercisers

“To best support health, clinicians should consider taking a few seconds to ask patients about their physical activity levels,” said Dr. Paluch, who was the lead author on the Lancet meta-analysis of daily steps. In that study, Dr. Paluch and colleagues found that taking more steps each day was associated with a progressively lower risk of all-cause mortality. However, that study did not measure step rate.

Clinicians can emphasize that health benefits do not require an hour-long exercise routine and special equipment, and moving more, even in shorts bursts of activity can have meaningful associations with health, particularly for those who are less active, she said.

The recent studies on short bursts of activity agree that “some physical activity is better than none and adults should move more throughout the day in whatever way makes sense to them and fits best into their lives,” said Dr. Paluch. “For example, opting for the stairs instead of the elevator, a brisk walk to the bus stop, a short game of hide and seek with the children or grandchildren – anything that gets your body moving more, even if briefly. Making simple lifestyle changes is often easier in small bites. In time, this can grow into long-term habits, ultimately leading to an overall active lifestyle that supports living healthier for longer.”

The Nature Medicine study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Several coauthors were supported by the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Novo Nordisk, the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, the Alan Turing Institute, the British Heart Foundation, and Health Data Research UK, an initiative funded by UK Research and Innovation. Dr. Paluch and Dr. Stoner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Short bursts of activity are approximately as effective for general health as longer sessions, especially for those who are mainly sedentary, according to several recently published studies.

If your fitness goals are greater, and you want to build muscle strength and endurance, compete in a 5K, or just look better in your swimsuit, you will need to do more. But for basic health, it appears that short bursts can help, the new research papers and experts suggest.

“Whether you accumulate activity in many short bouts versus one extended bout, the general health benefits tend to be similar,” Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, said in an interview.

Current public health recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest doing at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week for health benefits, but this activity can be accumulated in any way over the week, she noted. Previous versions of the CDC guidelines on exercise suggested that physical activity bouts should be at least 10 minutes each, but the latest version of the guidelines acknowledges that bursts of less than 10 minutes may be beneficial.

However, “the activity or fitness level at which someone starts and the specific health goals matter,” Dr. Paluch continued. “Short bouts may be particularly beneficial for those least active to get moving more to improve their general wellness.”

The current federal physical activity guidelines are still worth striving for, and patients can work their way to this goal, accumulating 150 or more minutes in a way that works best for them, she added.

“There is a lack of research directly comparing individuals who consistently accumulate their activity in many short bouts versus single bouts over an extended period of time,” Dr. Paluch noted. From a public health perspective, since both short and long bouts have health benefits, the best physical activity is what fits into your life and helps build a lifelong habit.

The benefits of exercise for cardiovascular health are well documented. A review from Circulation published in 2003 summarized the benefits of regular physical activity on measures of cardiovascular health including reduction in body weight, blood pressure, and bad cholesterol, while increasing insulin sensitivity, good cholesterol, and muscular strength and function. In that review, author Jonathan N. Myers, PhD, now of Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that “one need not be a marathon runner or an elite athlete to derive significant benefits from physical activity.” In fact, “the greatest gains in terms of mortality are achieved when an individual goes from being sedentary to becoming moderately active.”

A recent large, population-based study showed the value of short bursts of exercise for those previously sedentary. In this study, published in Nature Medicine, a team in Australia used wearable fitness trackers to measure the health benefits of what researchers have named “vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity” or VILPA.

Some examples of VILPA include power walking on the way to work, climbing stairs, or even running around with your kids on the playground.

Specifically, individuals who engaged in the median VILPA frequency of three bursts of vigorous activity lasting 1-2 minutes showed a 38%-40% reduction in all-cause mortality risk and cancer mortality risk, and a 48%-49% reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk.

The researchers repeated their analysis for a group of 62,344 adults from the UK Biobank who reported regular vigorous physical activity (VPA). They found similar effects on mortality, based on 1,552 deaths reported.

These results suggest that VILPA may be a reasonable physical activity target, especially for people not able or willing to exercise more formally or intensely, the researchers noted.

“We have known for a long time that leisure-time exercise often reaches vigorous intensity and has many health benefits, but we understand less about the health potential of daily movement, especially activities done as part of daily living that reach vigorous intensity,” lead author Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, professor of physical activity, lifestyle and population health at the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, said in an interview.

“As long as the heart rate goes up for a minute or 2 it will likely be vigorous activity,” Dr. Stamatakis said in an interview. “It is also important that clinicians effectively communicate how patients can know that they are reaching vigorous intensity,” he said.

Signs of vigorous intensity include increased heart rate and getting out of breath after about 20-40 seconds from the start of the VILPA burst. After about a minute of VILPA, the person doing it should be too out of breath to speak more than a few words comfortably, he said.

Data support value of any and all exercise

The Nature Medicine study supports other recent research showing the value of short, intense bursts of physical activity. A pair of recent studies also used fitness trackers to measure activity in adults and assess the benefits on outcomes including death and heart disease.

One of these studies, which was published in the European Heart Journal, also used fitness trackers to measure physical activity at moderate and vigorous levels. The researchers found that individuals who performed at least 20% of their physical activity at a moderate to high level, such as by doing brisk walking in lieu of strolling had a significantly lower risk of heart disease than those whose daily activity included less than 20% at a moderate or intense level.

In another study from the European Heart Journal, researchers found that short bursts of vigorous physical activity of 2 minutes or less adding up to 15-20 minutes per week was enough to reduce mortality by as much as 40%.

Plus, a meta-analysis published in the Lancet showed a decrease in all-cause mortality with an increase in the number of daily steps, although the impact of stepping rate on mortality was inconsistent.

“Many studies have investigated the health benefits of physical activity, but not the importance of these difficult-to-capture VILPA bouts that accrue during the course of normal activities of daily living,” Lee Stoner, PhD, an exercise physiologist and director of the Cardiometabolic Lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr. Stoner, who was not involved in the Nature Medicine study, said he was not surprised by the overall finding that doing short bursts of activity impacted mortality and cardiovascular disease, but was slightly surprised by the strength of the evidence.

“The referent group in the Nature Medicine study were those accruing no VILPA”, likely meaning they were very inactive,” Dr. Stoner said and added that he thinks this demonstrates the value of VILPA.

Even without immediately meeting the specific numbers recommended by the CDC, “any physical activity is better than none, especially if vigorous, and VILPA can be built into normal daily routines,” Dr. Stoner added.

What’s missing in short bursts?

Short bursts of activity do have their limits when it comes to overall fitness, said Dr. Stoner.

“Endurance will not be improved as much through short bursts, because such activities are unlikely to be as effective at empowering the mitochondria – the batteries keeping our cells running, including skeletal muscle cells,” he said. “Additionally, the vigorous bouts are unlikely to be as effective at improving muscular strength and endurance. For this, it is recommended that we engage each muscle group in strengthening exercises two times per week.”

However, Dr. Stoner agreed that prescribing short bursts of intense activity as part of daily living may be a great way to get people started with exercise.

“The key is to remove barriers to physical activity pursuit, then focusing on long-term routine rather than short-term gain,” he said. “Individuals are better served if they focus on goals other than weight loss, for which physical activity or exercise may not be the solution. Rather, being physically active can improve vigor, make daily activities simpler, and improve cognitive abilities,” and any physical activity is one of the most effective solutions for regulating blood glucose levels and improving cardiovascular risk factors.

Make it routine – and fun

To benefit from physical activity, cultivating and sustaining a long-term routine is key, said Dr. Stoner, whose research has focused on sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease. Whatever the activity is, shorter bursts, or longer bouts or both, it is essential that individuals figure out activities that they enjoy if they want to create sustained behavior, and thus health change, Gabriel Zieff, MA, a doctoral candidate in Dr. Stoner’s Cardiometabolic Lab, who conducts studies on exercise, noted in an interview.

“We exercise enthusiasts and researchers are often hyperfocused on whether this duration or that duration is better, whether this intensity or that intensity is better,” but at the end of the day, it is the enjoyment factor that often predicts sustained behavior change, and should be part of discussions with patients to help reduce sedentary behavior and promote activity, Mr. Zieff said.

Short bouts can encourage hesitant exercisers

“To best support health, clinicians should consider taking a few seconds to ask patients about their physical activity levels,” said Dr. Paluch, who was the lead author on the Lancet meta-analysis of daily steps. In that study, Dr. Paluch and colleagues found that taking more steps each day was associated with a progressively lower risk of all-cause mortality. However, that study did not measure step rate.

Clinicians can emphasize that health benefits do not require an hour-long exercise routine and special equipment, and moving more, even in shorts bursts of activity can have meaningful associations with health, particularly for those who are less active, she said.

The recent studies on short bursts of activity agree that “some physical activity is better than none and adults should move more throughout the day in whatever way makes sense to them and fits best into their lives,” said Dr. Paluch. “For example, opting for the stairs instead of the elevator, a brisk walk to the bus stop, a short game of hide and seek with the children or grandchildren – anything that gets your body moving more, even if briefly. Making simple lifestyle changes is often easier in small bites. In time, this can grow into long-term habits, ultimately leading to an overall active lifestyle that supports living healthier for longer.”

The Nature Medicine study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Several coauthors were supported by the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Novo Nordisk, the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, the Alan Turing Institute, the British Heart Foundation, and Health Data Research UK, an initiative funded by UK Research and Innovation. Dr. Paluch and Dr. Stoner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Fitbit figures: More steps per day cut type 2 diabetes risk

The protective effect of daily step count on type 2 diabetes risk remained after adjusting for smoking and sedentary time.

Taking more steps per day was also associated with less risk of developing type 2 diabetes in different subgroups of physical activity intensity.

“Our data shows the importance of moving your body every day to lower your risk of [type 2] diabetes,” said the lead author of the research, Andrew S. Perry, MD. The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Despite low baseline risk, benefit from increased physical activity

The study was conducted in more than 5,000 participants in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program who had a median age of 51 and were generally overweight (median BMI 27.8 kg/m2). Three quarters were women and 89% were White.

It used an innovative approach in a real-world population, said Dr. Perry, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The individuals in this cohort had relatively few risk factors, so it was not surprising that the incidence of type 2 diabetes overall was low (2%), the researchers note. “Yet, despite being low risk, we still detected a signal of benefit from increased” physical activity, Dr. Perry and colleagues write.

The individuals had a median of 16 very active minutes/day, which corresponds to 112 very active minutes/week (ie, less than the guideline-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity/week).

“These results indicate that amounts of physical activity are correlated with lower risk of [type 2] diabetes, regardless of the intensity level, and even at amounts less than current guidelines recommend,” the researchers summarize.

Physical activity tracked over close to 4 years

Prior studies of the relationship between physical activity and type 2 diabetes risk relied primarily on questionnaires that asked people about physical activity at one point in time.

The researchers aimed to examine this association over time, in a contemporary cohort of Fitbit users who participated in the All of Us program.

From 12,781 participants with Fitbit data between 2010 and 2021, they identified 5,677 individuals who were at least 18 years old and had linked electronic health record data, no diabetes at baseline, at least 15 days of Fitbit data in the initial monitoring period, and at least 180 days of follow-up.

The Fitbit counts steps, and it also uses an algorithm to quantify physical activity intensity as lightly active (1.5-3 metabolic equivalent task (METs), fairly active (3-6 METs), and very active (> 6 METs).

During a median 3.8-year follow-up, participants made a median of 7,924 steps/day and were “fairly active” for a median of 16 minutes/day.

They found 97 new cases of type 2 diabetes over a follow-up of 4 years in the dataset.

The predicted cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes at 5 years was 0.8% for individuals who walked 13,245 steps/day (90th percentile) vs. 2.3% for those who walked 4,301 steps/day (10th percentile).

“We hope to study more diverse populations in future studies to confirm the generalizability of these findings,” Dr. Perry said.

This study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Perry reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The protective effect of daily step count on type 2 diabetes risk remained after adjusting for smoking and sedentary time.

Taking more steps per day was also associated with less risk of developing type 2 diabetes in different subgroups of physical activity intensity.

“Our data shows the importance of moving your body every day to lower your risk of [type 2] diabetes,” said the lead author of the research, Andrew S. Perry, MD. The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Despite low baseline risk, benefit from increased physical activity

The study was conducted in more than 5,000 participants in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program who had a median age of 51 and were generally overweight (median BMI 27.8 kg/m2). Three quarters were women and 89% were White.

It used an innovative approach in a real-world population, said Dr. Perry, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The individuals in this cohort had relatively few risk factors, so it was not surprising that the incidence of type 2 diabetes overall was low (2%), the researchers note. “Yet, despite being low risk, we still detected a signal of benefit from increased” physical activity, Dr. Perry and colleagues write.

The individuals had a median of 16 very active minutes/day, which corresponds to 112 very active minutes/week (ie, less than the guideline-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity/week).

“These results indicate that amounts of physical activity are correlated with lower risk of [type 2] diabetes, regardless of the intensity level, and even at amounts less than current guidelines recommend,” the researchers summarize.

Physical activity tracked over close to 4 years

Prior studies of the relationship between physical activity and type 2 diabetes risk relied primarily on questionnaires that asked people about physical activity at one point in time.

The researchers aimed to examine this association over time, in a contemporary cohort of Fitbit users who participated in the All of Us program.

From 12,781 participants with Fitbit data between 2010 and 2021, they identified 5,677 individuals who were at least 18 years old and had linked electronic health record data, no diabetes at baseline, at least 15 days of Fitbit data in the initial monitoring period, and at least 180 days of follow-up.

The Fitbit counts steps, and it also uses an algorithm to quantify physical activity intensity as lightly active (1.5-3 metabolic equivalent task (METs), fairly active (3-6 METs), and very active (> 6 METs).

During a median 3.8-year follow-up, participants made a median of 7,924 steps/day and were “fairly active” for a median of 16 minutes/day.

They found 97 new cases of type 2 diabetes over a follow-up of 4 years in the dataset.

The predicted cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes at 5 years was 0.8% for individuals who walked 13,245 steps/day (90th percentile) vs. 2.3% for those who walked 4,301 steps/day (10th percentile).

“We hope to study more diverse populations in future studies to confirm the generalizability of these findings,” Dr. Perry said.

This study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Perry reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The protective effect of daily step count on type 2 diabetes risk remained after adjusting for smoking and sedentary time.

Taking more steps per day was also associated with less risk of developing type 2 diabetes in different subgroups of physical activity intensity.

“Our data shows the importance of moving your body every day to lower your risk of [type 2] diabetes,” said the lead author of the research, Andrew S. Perry, MD. The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Despite low baseline risk, benefit from increased physical activity

The study was conducted in more than 5,000 participants in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program who had a median age of 51 and were generally overweight (median BMI 27.8 kg/m2). Three quarters were women and 89% were White.

It used an innovative approach in a real-world population, said Dr. Perry, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The individuals in this cohort had relatively few risk factors, so it was not surprising that the incidence of type 2 diabetes overall was low (2%), the researchers note. “Yet, despite being low risk, we still detected a signal of benefit from increased” physical activity, Dr. Perry and colleagues write.

The individuals had a median of 16 very active minutes/day, which corresponds to 112 very active minutes/week (ie, less than the guideline-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity/week).

“These results indicate that amounts of physical activity are correlated with lower risk of [type 2] diabetes, regardless of the intensity level, and even at amounts less than current guidelines recommend,” the researchers summarize.

Physical activity tracked over close to 4 years

Prior studies of the relationship between physical activity and type 2 diabetes risk relied primarily on questionnaires that asked people about physical activity at one point in time.

The researchers aimed to examine this association over time, in a contemporary cohort of Fitbit users who participated in the All of Us program.

From 12,781 participants with Fitbit data between 2010 and 2021, they identified 5,677 individuals who were at least 18 years old and had linked electronic health record data, no diabetes at baseline, at least 15 days of Fitbit data in the initial monitoring period, and at least 180 days of follow-up.

The Fitbit counts steps, and it also uses an algorithm to quantify physical activity intensity as lightly active (1.5-3 metabolic equivalent task (METs), fairly active (3-6 METs), and very active (> 6 METs).

During a median 3.8-year follow-up, participants made a median of 7,924 steps/day and were “fairly active” for a median of 16 minutes/day.

They found 97 new cases of type 2 diabetes over a follow-up of 4 years in the dataset.

The predicted cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes at 5 years was 0.8% for individuals who walked 13,245 steps/day (90th percentile) vs. 2.3% for those who walked 4,301 steps/day (10th percentile).

“We hope to study more diverse populations in future studies to confirm the generalizability of these findings,” Dr. Perry said.

This study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Perry reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rise of ‘alarming’ subvariants of COVID ‘worrisome’ for winter

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL

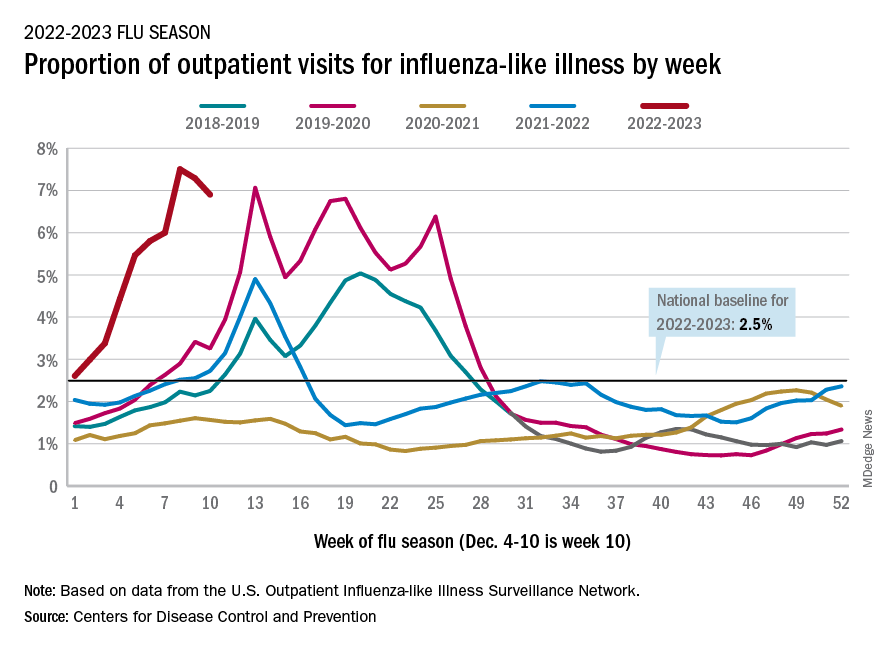

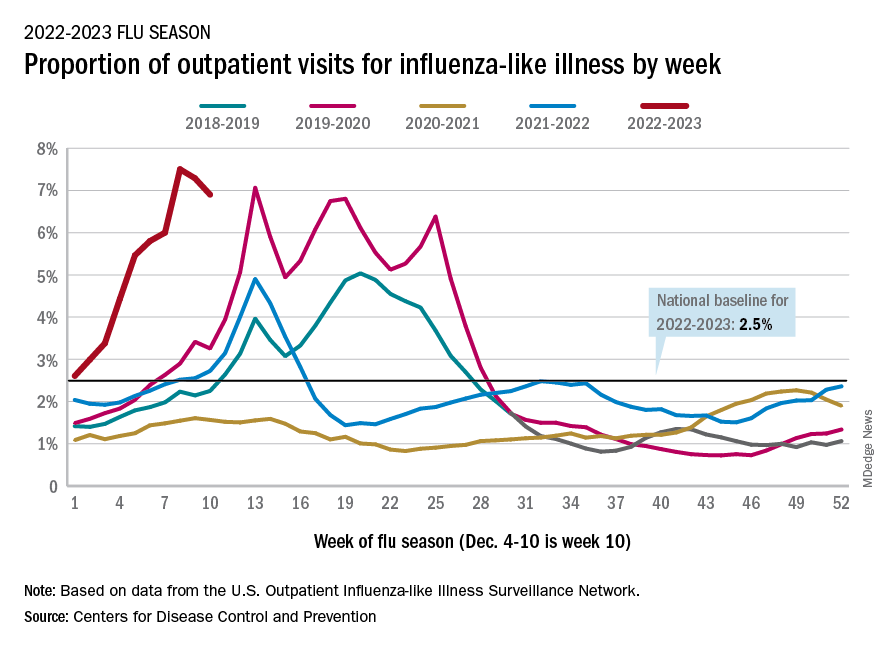

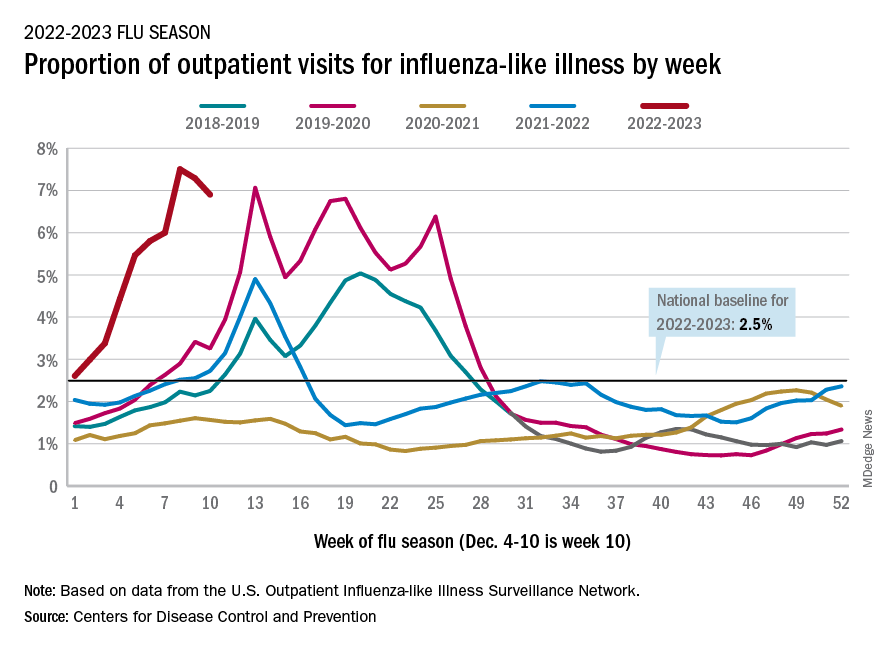

Flu hospitalizations drop amid signs of an early peak

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Behavioral treatment tied to lower medical, pharmacy costs

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect