User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Cardiac injury caused by COVID-19 less common than thought

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

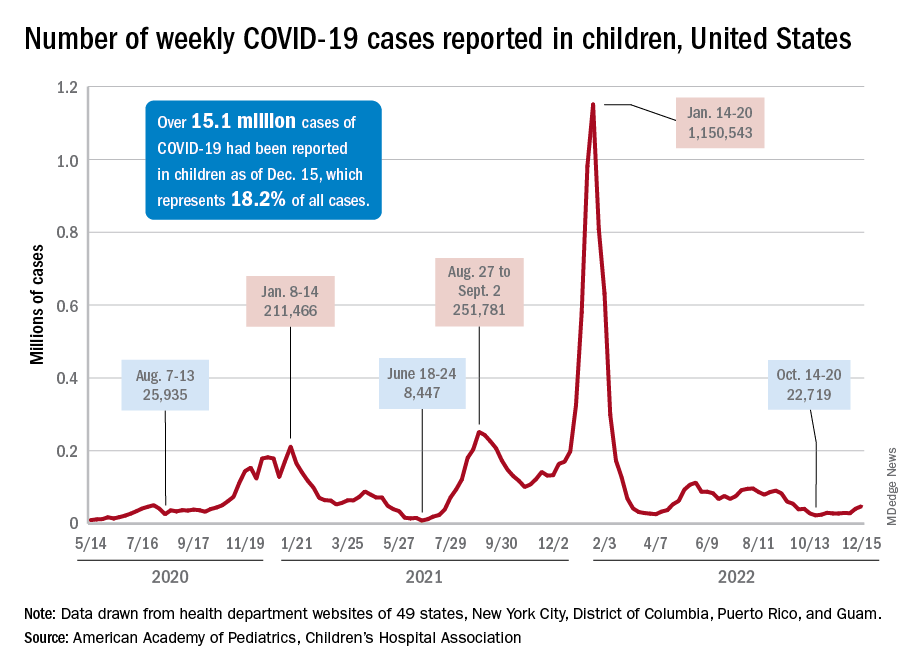

Children and COVID: New-case counts offer dueling narratives

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

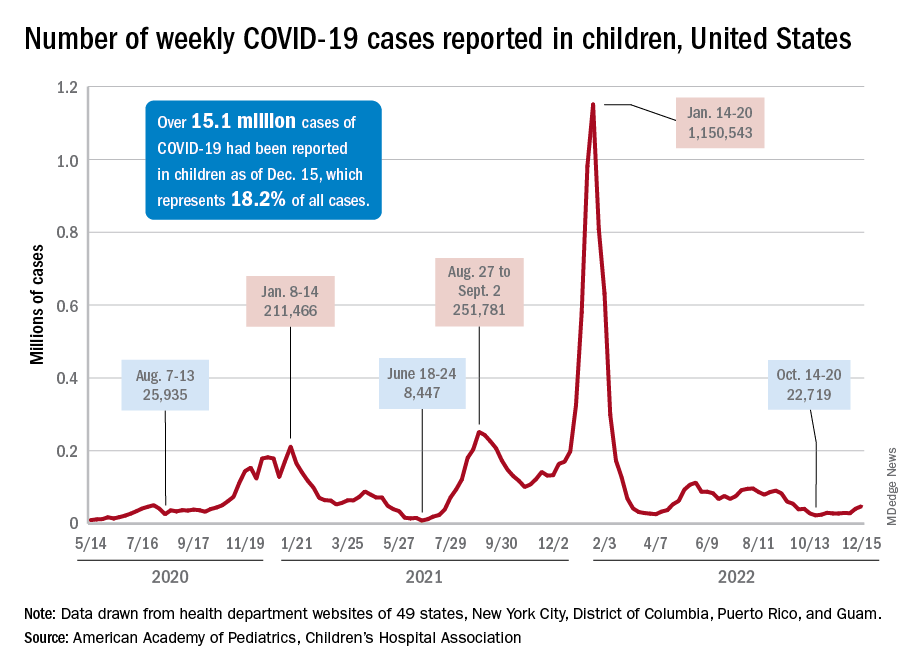

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

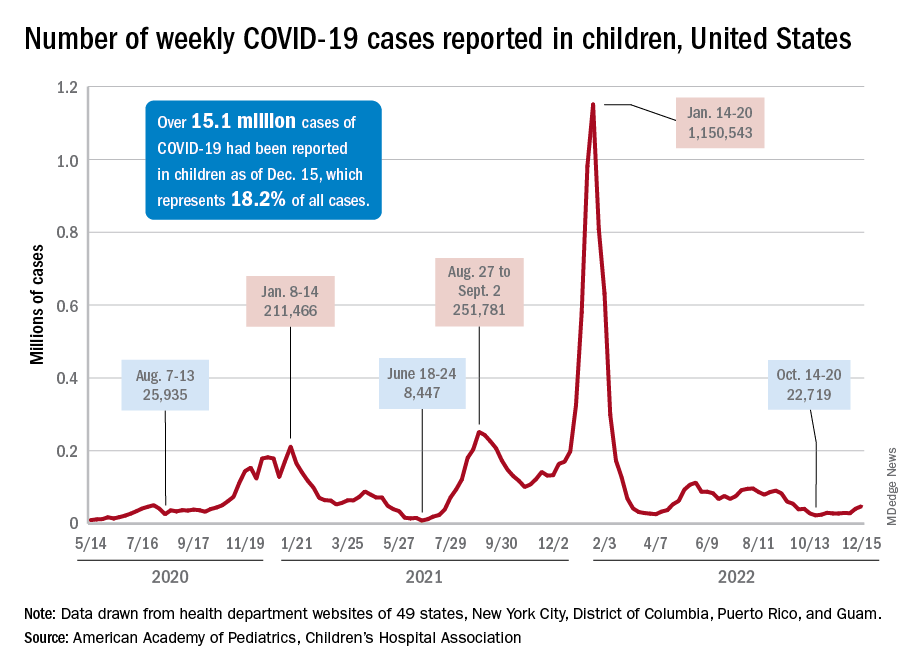

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

High lipoprotein(a) levels plus hypertension add to CVD risk

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HYPERTENSION

Dubious diagnosis: Is there a better way to define ‘prediabetes’?

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT IDF WORLD DIABETES CONGRESS 2022

Researchers probe ‘systematic error’ in gun injury data

These coding inaccuracies could distort our understanding of gun violence in the United States and make it seem like accidental shootings are more common than they really are, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

“The systematic error in intent classification is not widely known or acknowledged by researchers in this field,” Philip J. Cook, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and Susan T. Parker, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in an invited commentary about the new findings. “The bulk of all shootings, nonfatal and fatal together, are assaults, which is to say the result of one person intentionally shooting another. An accurate statistical portrait thus suggests that gun violence is predominantly a crime problem.”

In 2020, 79% of all homicides and 53% of all suicides involved firearms, the CDC reported. Gun violence is now the leading cause of death for children in the United States, government data show.

For the new study, Matthew Miller, MD, ScD, of Northeastern University and the Harvard Injury Control Research Center in Boston, and his colleagues examined how International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes may misclassify the intent behind gunshot injuries.

Dr. Miller’s group looked at 1,227 incidents between 2008 and 2019 at three major trauma centers – Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Of those shootings, 837 (68.2%) involved assaults, 168 (13.5%) were unintentional, 124 (9.9%) were deliberate self-harm, and 43 (3.4%) were instances of legal intervention, based on the researchers’ review of medical records.

ICD codes at discharge, however, labeled 581 cases (47.4%) as assaults and 432 (35.2%) as unintentional.

The researchers found that 234 of the 837 assaults (28%) and 9 of the 43 legal interventions (20.9%) were miscoded as unintentional. This problem occurred even when the “medical narrative explicitly indicated that the shooting was an act of interpersonal violence,” such as a drive-by shooting or an act of domestic violence, the researchers reported.

Hospital trauma registrars, who detail the circumstances surrounding injuries, were mostly in agreement with the researchers.

Medical coders “would likely have little trouble characterizing firearm injury intent accurately if incentives were created for them to do so,” the authors wrote.

Trends and interventions

Separately, researchers published studies showing that gun violence tends to affect various demographics differently, and that remediating abandoned houses could help reduce gun crime.

Lindsay Young, of the University of Cincinnati, and Henry Xiang, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Pediatric Trauma Research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, analyzed rates of firearm deaths from 1981 to 2020.

They found that the rate of firearm-related homicide was five times higher among males than females, and the rate of suicide involving firearms was nearly seven times higher for men, they reported in PLOS ONE.

Black men were the group most affected by homicide, whereas White men were most affected by suicide, they found.

To see if fixing abandoned properties would improve health and reduce gun violence in low-income, Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Eugenia C. South, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues conducted a randomized trial.

They randomly assigned abandoned properties in some areas to undergo full remediation (installing working windows and doors, cleaning trash, and weeding); trash cleanup and weeding only; or no intervention.

“Abandoned houses that were remediated showed substantial drops in nearby weapons violations (−8.43%), gun assaults (−13.12%), and to a lesser extent shootings (−6.96%),” the researchers reported.

The intervention targets effects of segregation that have resulted from “historical and ongoing government and private-sector policies” that lead to disinvestment in Black, urban communities, they wrote. Abandoned houses can be used to store firearms and for other illegal activity. They also can engender feelings of fear, neglect, and stress in communities, the researchers noted.

Dr. Miller’s study was funded by the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research; coauthors disclosed corporate, government, and university grants. The full list of disclosures can be found with the original article. Editorialists Dr. Cook and Dr. Parker report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. South’s study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. South and some coauthors disclosed government grants.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These coding inaccuracies could distort our understanding of gun violence in the United States and make it seem like accidental shootings are more common than they really are, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

“The systematic error in intent classification is not widely known or acknowledged by researchers in this field,” Philip J. Cook, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and Susan T. Parker, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in an invited commentary about the new findings. “The bulk of all shootings, nonfatal and fatal together, are assaults, which is to say the result of one person intentionally shooting another. An accurate statistical portrait thus suggests that gun violence is predominantly a crime problem.”

In 2020, 79% of all homicides and 53% of all suicides involved firearms, the CDC reported. Gun violence is now the leading cause of death for children in the United States, government data show.

For the new study, Matthew Miller, MD, ScD, of Northeastern University and the Harvard Injury Control Research Center in Boston, and his colleagues examined how International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes may misclassify the intent behind gunshot injuries.

Dr. Miller’s group looked at 1,227 incidents between 2008 and 2019 at three major trauma centers – Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Of those shootings, 837 (68.2%) involved assaults, 168 (13.5%) were unintentional, 124 (9.9%) were deliberate self-harm, and 43 (3.4%) were instances of legal intervention, based on the researchers’ review of medical records.

ICD codes at discharge, however, labeled 581 cases (47.4%) as assaults and 432 (35.2%) as unintentional.