User login

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

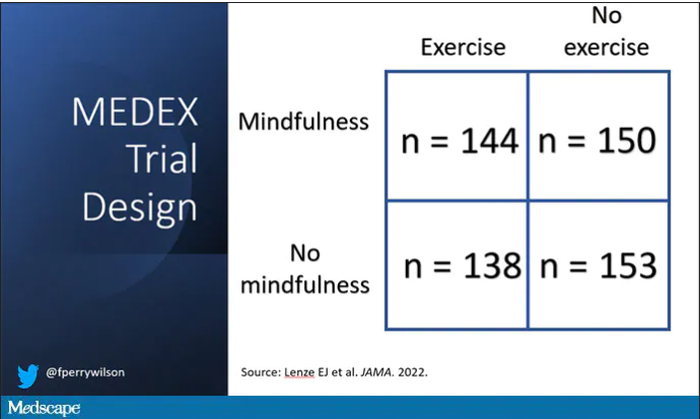

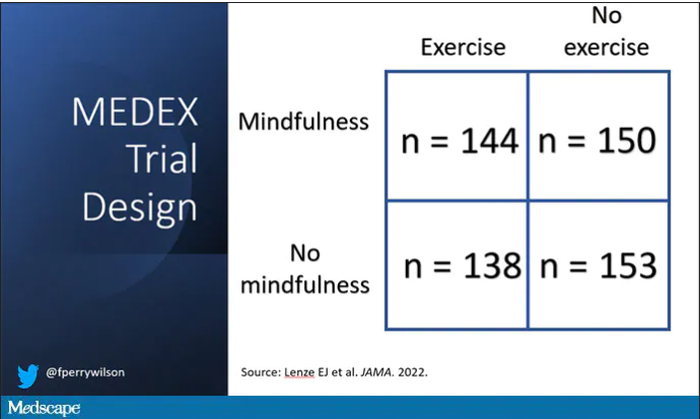

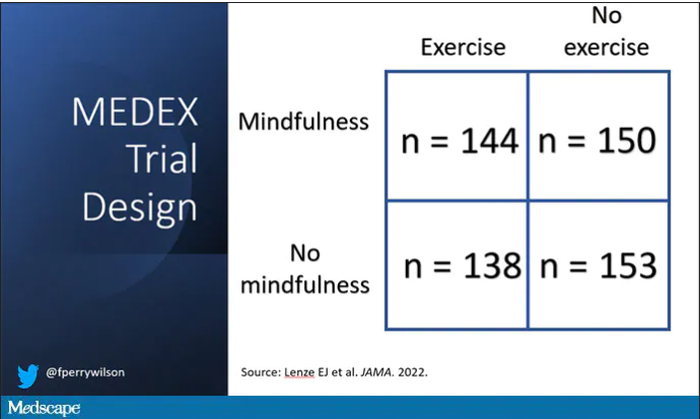

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.