User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cutaneous Adenosquamous Carcinoma: A Rare Neoplasm With Biphasic Differentiation

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

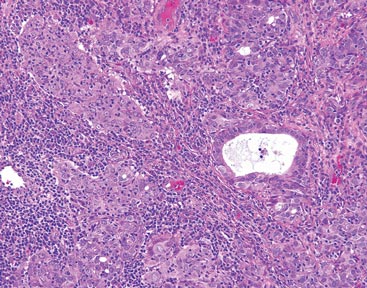

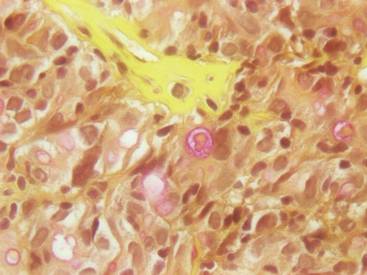

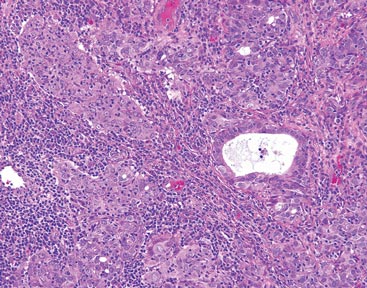

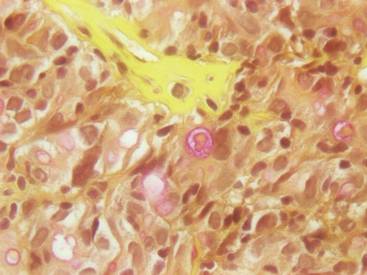

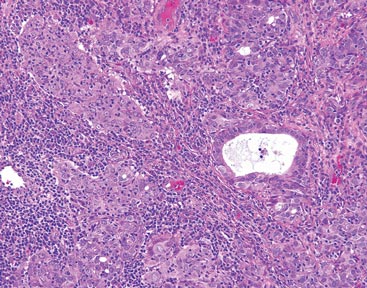

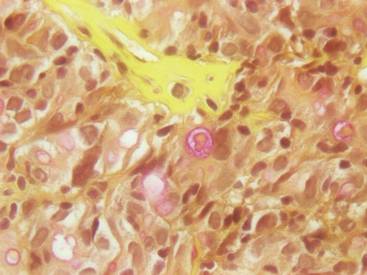

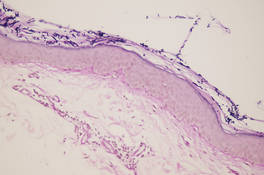

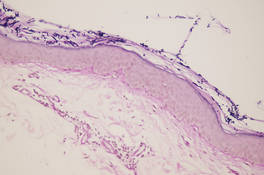

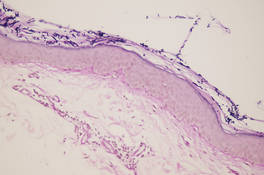

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.  Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).  Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.  Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).  Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.  Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).  Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an extremely rare malignant neoplasm with histologic similarities to both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

- Mohs micrographic surgery for excision is recommended; however, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors also have been used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.

Tumor Volume: An Adjunct Prognostic Factor in Cutaneous Melanoma

Melanoma continues to be a devastating disease unless diagnosed and treated early. According to the National Cancer Institute, there will be more than 76,000 new cases of invasive melanoma and nearly 10,000 melanoma-related deaths in 2014 in the United States.1 If diagnosed early, more than 93% of melanoma patients can expect to be cured, but later diagnosis of thicker melanoma is associated with a worse prognosis. Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for cutaneous melanoma, including wide excision and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy for staging of the regional nodal basins in appropriate patients. Although novel targeted therapies and immunotherapies have been associated with improved survival in metastatic melanoma, detection of cutaneous melanoma in its early phases remains the best chance for cure.

Tumor thickness, or Breslow depth, is the most important histologic determinant of prognosis in melanoma patients and is measured vertically in millimeters from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of the tumor involvement. Increased tumor thickness confers a higher metastatic potential and poorer prognosis.2 Other histologic prognostic factors that have been incorporated into the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system include the presence or absence of ulceration and mitotic index (measured per square millimeter), particularly for T1 melanomas (<1 mm thick), though Breslow depth greater than 0.75 mm appears to be the most reliable predictor of SLN metastasis in thin (T1) melanomas (≤1 mm).3

Tumor volume assessment may be a helpful adjunct to Breslow depth as a prognostic indicator for melanoma, particularly for predicting SLN metastasis.4 This retrospective study was designed to assess the improvement in the accuracy of Breslow depth as a prognostic factor by utilizing tumor volume combined with mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction (eg, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes).

Methods

The study was approved by the Stanford University (Stanford, California) institutional review board. A retrospective review of invasive primary melanomas recorded in Stanford University’s pathology/dermatopathology database from January 2007 through December 2010 was conducted. Because cases included both Stanford Health Care (formerly Stanford Hospital & Clinics) and outside pathology consultations, clinical assessment of patient outcome was not possible for all cases and thus was not performed.

Assessment

Information extracted from the pathology reports included Breslow depth; estimated surface area of the primary tumor (measured by the longest vertical and horizontal dimensions recorded by the clinician prior to diagnostic biopsy and reported on the biopsy requisition form [>90% of cases] or reported by the pathologist on gross measurement of the pigmented lesion in formalin [<10% of cases]); mitotic index (measured per square millimeter); presence or absence of ulceration; and inflammatory host reaction (as noted by tumor-infiltrating response). Our method of estimating the tumor volume (lesion surface area • Breslow depth) did not take into account border irregularities in the primary tumor. This method also was limited because prebiopsy clinical measurement could differ from gross pathologic measurement of the tumor due to shrinkage of the latter ex vivo and following formalin fixation. However, when both measurements were documented, the pathological measurement was only slightly less than the clinical measurement. Metastases were defined as those in lymph nodes (microscopic or macroscopic), skin, or in distant organs, as identified through review of subsequent pathology reports.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3. Test statistics were preset at a significance level of α=.05. Using metastasis status as the outcome, univariate regression models were first fitted to assess the predictive ability of each prognostic indicator. In univariate analyses, continuous prognostic indicators (Breslow depth, tumor volume, and surface area) were included in the model while seeking the best functional form by means of fractional polynomials modeling.5,6 Predictive ability of prognostic indicators was determined by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).7 Using best functional form for Breslow depth, all other prognostic indicators were added to the model to assess their individual contributions to improve the predictive ability for tumor metastasis. The functional forms used for tumor volume and surface area were those determined in the univariate analysis. Multivariable models were compared aiming for an improvement of the best Breslow model indices: Schwarz criterion, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, generalized R2, and AUC.5 The added contribution of clinical predictors to the model for Breslow depth was judged by the significance of the coefficient for the added clinical predictor, the significance of the change in AUC, and the change in the model indices listed above. A check on overdispersion was carried out on the final model selected.

Results

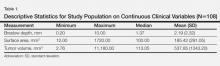

There were 108 eligible cases in the 4-year time period in which tumor volume assessment could be determined based on the pathology report in conjunction with Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and tumor infiltrating response. Breslow depth ranged from 0.20 to 10.00 mm, with a median depth of 1.37 mm. Surface area ranged from 12.00 to 1720.00 mm2 (median, 100.00 mm2). Tumor volume was calculated by multiplying Breslow depth by surface area and ranged from 2.76 to 11,180.00 mm3 (median, 113.05 mm3)(Table 1). Ulceration was present in 18.69% of the tumors, 20.37% exhibited a brisk inflammatory host reaction, and 53.27% had a mitotic index of 1/mm2 or more. Tumor metastasis was noted in 40.74% (44/108) of patients (Table 2), all of whom had a primary melanoma with a Breslow depth greater than 1 mm. Only one T1 melanoma had a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3. Metastasis in patients with T2 (1- to 2-mm thick) and T3 (2- to 4-mm thick) melanoma was associated with a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3 in 16 of 26 patients (61.54%), and all 18 patients with T4 melanomas (>4-mm thick) had tumor volume greater than 250 mm3.

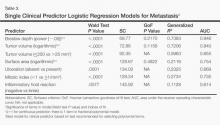

Univariate analysis demonstrated that Breslow depth was the best prognostic indicator of metastasis (AUC=0.946) but that tumor volume (as a continuous variable) was nearly equally predictive (AUC=0.940)(Table 3). Tumor volume alone (categorized as <250 mm3 vs >250 mm3) had lower prognostic value (AUC=0.855). Mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, inflammatory host reaction, and surface area also had lower prognostic values, though all were significant factors (P values ranging from <.0001 to .0077)(Table 3).

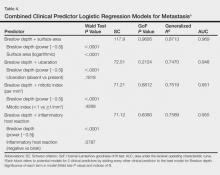

Importantly, the addition of surface area, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction to the model to Breslow depth did not improve predictive ability for metastasis, and AUC values did not increase significantly after adding these factors (Table 4). In particular, the change in AUC for adding surface area to the model with Breslow depth was 0.023 (P=.1095). Models in Table 4 were checked for interaction of these 2 predictors, and the interaction term for thickness and surface area was not statistically significant (P=.0932)(data not shown).

Comment

Decades after the concept of measuring tumor thickness in cutaneous melanomas was proposed by Dr. Alexander Breslow, it remains the most reliable predictor of prognosis in melanoma patients.2 Our study demonstrated that tumor volume may be contributory to thickness, despite our relatively imprecise assessment of tumor volume based on clinical or pathological reporting of primary tumor area. Because more than 90% of our tumor volume measurements were based on clinician reports of the lesion size before diagnostic biopsy rather than gross measurement of the tumor by the pathologist after biopsy, we believe that measurement and assessment of tumor volume could be readily incorporated into the clinical practice setting. Although we could not demonstrate a correlation between SLN positivity and tumor volume in T1 melanomas because none of the T1 tumors exhibited microscopic nodal metastasis, assessment of tumor volume may assist the clinician in patient management, using a 250-mm3 cutoff point. Gross tumor measurement is important to allow for accurate assessment of volume and would preferably be recorded by the clinician prior to biopsy with notation of clinical lesion size on the pathology requisition form, as is recommended in the American Academy of Dermatology’s melanoma practice guidelines.8

A prior assessment of 123 patients with invasive primary melanomas demonstrated that greater tumor volume (>250 mm3) was associated with metastasis across all tumor thicknesses.4 In T1 melanoma, no patients with a tumor volume less than 250 mm3 demonstrated SLN metastasis,4 suggesting that volume assessment may aid in consideration of staging with SLN biopsy in conjunction with tumor thickness and other established prognostic factors for SLN positivity in thin melanomas (eg, high mitotic index [particularly in tumors >0.75-mm thick]), histologic ulceration, and/or lymphovascular invasion).2,8

It should be noted, however, that lentigo maligna melanoma, which often is predominantly in situ with only focal papillary dermal invasion, may have an erroneously high tumor volume due to its larger total surface area. However, tumor volume would not be expected to correlate with tumor metastasis given the thin invasive component. The current study was limited by not accounting for melanoma subtype in the overall analysis.

A practical estimation of tumor volume based on clinical measurement of tumor size (ie, surface area of the suspicious lesion prior to biopsy) in combination with the pathologist’s assessment of Breslow depth may be a helpful adjunct to predicting likelihood of development of metastasis. We suggest that the concept of tumor volume should be subjected to more rigorous investigation with standardized clinical/prebiopsy measurement of the lesion; correlation with known histologic prognostic factors, SLN positivity, and/or development of additional nodal or visceral metastasis; and most importantly long-term patient outcome in terms of survival. Our preliminary data suggest the value of this enterprise.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:395-407.

4. Walton RG, Velasco C. Volume as a prognostic indicator in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Practical Dermatol. September 2010:26-28.

5. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000.

6. Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model-Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Analysis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

7. Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Vol 28. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2004.

8. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

Melanoma continues to be a devastating disease unless diagnosed and treated early. According to the National Cancer Institute, there will be more than 76,000 new cases of invasive melanoma and nearly 10,000 melanoma-related deaths in 2014 in the United States.1 If diagnosed early, more than 93% of melanoma patients can expect to be cured, but later diagnosis of thicker melanoma is associated with a worse prognosis. Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for cutaneous melanoma, including wide excision and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy for staging of the regional nodal basins in appropriate patients. Although novel targeted therapies and immunotherapies have been associated with improved survival in metastatic melanoma, detection of cutaneous melanoma in its early phases remains the best chance for cure.

Tumor thickness, or Breslow depth, is the most important histologic determinant of prognosis in melanoma patients and is measured vertically in millimeters from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of the tumor involvement. Increased tumor thickness confers a higher metastatic potential and poorer prognosis.2 Other histologic prognostic factors that have been incorporated into the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system include the presence or absence of ulceration and mitotic index (measured per square millimeter), particularly for T1 melanomas (<1 mm thick), though Breslow depth greater than 0.75 mm appears to be the most reliable predictor of SLN metastasis in thin (T1) melanomas (≤1 mm).3

Tumor volume assessment may be a helpful adjunct to Breslow depth as a prognostic indicator for melanoma, particularly for predicting SLN metastasis.4 This retrospective study was designed to assess the improvement in the accuracy of Breslow depth as a prognostic factor by utilizing tumor volume combined with mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction (eg, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes).

Methods

The study was approved by the Stanford University (Stanford, California) institutional review board. A retrospective review of invasive primary melanomas recorded in Stanford University’s pathology/dermatopathology database from January 2007 through December 2010 was conducted. Because cases included both Stanford Health Care (formerly Stanford Hospital & Clinics) and outside pathology consultations, clinical assessment of patient outcome was not possible for all cases and thus was not performed.

Assessment

Information extracted from the pathology reports included Breslow depth; estimated surface area of the primary tumor (measured by the longest vertical and horizontal dimensions recorded by the clinician prior to diagnostic biopsy and reported on the biopsy requisition form [>90% of cases] or reported by the pathologist on gross measurement of the pigmented lesion in formalin [<10% of cases]); mitotic index (measured per square millimeter); presence or absence of ulceration; and inflammatory host reaction (as noted by tumor-infiltrating response). Our method of estimating the tumor volume (lesion surface area • Breslow depth) did not take into account border irregularities in the primary tumor. This method also was limited because prebiopsy clinical measurement could differ from gross pathologic measurement of the tumor due to shrinkage of the latter ex vivo and following formalin fixation. However, when both measurements were documented, the pathological measurement was only slightly less than the clinical measurement. Metastases were defined as those in lymph nodes (microscopic or macroscopic), skin, or in distant organs, as identified through review of subsequent pathology reports.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3. Test statistics were preset at a significance level of α=.05. Using metastasis status as the outcome, univariate regression models were first fitted to assess the predictive ability of each prognostic indicator. In univariate analyses, continuous prognostic indicators (Breslow depth, tumor volume, and surface area) were included in the model while seeking the best functional form by means of fractional polynomials modeling.5,6 Predictive ability of prognostic indicators was determined by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).7 Using best functional form for Breslow depth, all other prognostic indicators were added to the model to assess their individual contributions to improve the predictive ability for tumor metastasis. The functional forms used for tumor volume and surface area were those determined in the univariate analysis. Multivariable models were compared aiming for an improvement of the best Breslow model indices: Schwarz criterion, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, generalized R2, and AUC.5 The added contribution of clinical predictors to the model for Breslow depth was judged by the significance of the coefficient for the added clinical predictor, the significance of the change in AUC, and the change in the model indices listed above. A check on overdispersion was carried out on the final model selected.

Results

There were 108 eligible cases in the 4-year time period in which tumor volume assessment could be determined based on the pathology report in conjunction with Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and tumor infiltrating response. Breslow depth ranged from 0.20 to 10.00 mm, with a median depth of 1.37 mm. Surface area ranged from 12.00 to 1720.00 mm2 (median, 100.00 mm2). Tumor volume was calculated by multiplying Breslow depth by surface area and ranged from 2.76 to 11,180.00 mm3 (median, 113.05 mm3)(Table 1). Ulceration was present in 18.69% of the tumors, 20.37% exhibited a brisk inflammatory host reaction, and 53.27% had a mitotic index of 1/mm2 or more. Tumor metastasis was noted in 40.74% (44/108) of patients (Table 2), all of whom had a primary melanoma with a Breslow depth greater than 1 mm. Only one T1 melanoma had a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3. Metastasis in patients with T2 (1- to 2-mm thick) and T3 (2- to 4-mm thick) melanoma was associated with a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3 in 16 of 26 patients (61.54%), and all 18 patients with T4 melanomas (>4-mm thick) had tumor volume greater than 250 mm3.

Univariate analysis demonstrated that Breslow depth was the best prognostic indicator of metastasis (AUC=0.946) but that tumor volume (as a continuous variable) was nearly equally predictive (AUC=0.940)(Table 3). Tumor volume alone (categorized as <250 mm3 vs >250 mm3) had lower prognostic value (AUC=0.855). Mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, inflammatory host reaction, and surface area also had lower prognostic values, though all were significant factors (P values ranging from <.0001 to .0077)(Table 3).

Importantly, the addition of surface area, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction to the model to Breslow depth did not improve predictive ability for metastasis, and AUC values did not increase significantly after adding these factors (Table 4). In particular, the change in AUC for adding surface area to the model with Breslow depth was 0.023 (P=.1095). Models in Table 4 were checked for interaction of these 2 predictors, and the interaction term for thickness and surface area was not statistically significant (P=.0932)(data not shown).

Comment

Decades after the concept of measuring tumor thickness in cutaneous melanomas was proposed by Dr. Alexander Breslow, it remains the most reliable predictor of prognosis in melanoma patients.2 Our study demonstrated that tumor volume may be contributory to thickness, despite our relatively imprecise assessment of tumor volume based on clinical or pathological reporting of primary tumor area. Because more than 90% of our tumor volume measurements were based on clinician reports of the lesion size before diagnostic biopsy rather than gross measurement of the tumor by the pathologist after biopsy, we believe that measurement and assessment of tumor volume could be readily incorporated into the clinical practice setting. Although we could not demonstrate a correlation between SLN positivity and tumor volume in T1 melanomas because none of the T1 tumors exhibited microscopic nodal metastasis, assessment of tumor volume may assist the clinician in patient management, using a 250-mm3 cutoff point. Gross tumor measurement is important to allow for accurate assessment of volume and would preferably be recorded by the clinician prior to biopsy with notation of clinical lesion size on the pathology requisition form, as is recommended in the American Academy of Dermatology’s melanoma practice guidelines.8

A prior assessment of 123 patients with invasive primary melanomas demonstrated that greater tumor volume (>250 mm3) was associated with metastasis across all tumor thicknesses.4 In T1 melanoma, no patients with a tumor volume less than 250 mm3 demonstrated SLN metastasis,4 suggesting that volume assessment may aid in consideration of staging with SLN biopsy in conjunction with tumor thickness and other established prognostic factors for SLN positivity in thin melanomas (eg, high mitotic index [particularly in tumors >0.75-mm thick]), histologic ulceration, and/or lymphovascular invasion).2,8

It should be noted, however, that lentigo maligna melanoma, which often is predominantly in situ with only focal papillary dermal invasion, may have an erroneously high tumor volume due to its larger total surface area. However, tumor volume would not be expected to correlate with tumor metastasis given the thin invasive component. The current study was limited by not accounting for melanoma subtype in the overall analysis.

A practical estimation of tumor volume based on clinical measurement of tumor size (ie, surface area of the suspicious lesion prior to biopsy) in combination with the pathologist’s assessment of Breslow depth may be a helpful adjunct to predicting likelihood of development of metastasis. We suggest that the concept of tumor volume should be subjected to more rigorous investigation with standardized clinical/prebiopsy measurement of the lesion; correlation with known histologic prognostic factors, SLN positivity, and/or development of additional nodal or visceral metastasis; and most importantly long-term patient outcome in terms of survival. Our preliminary data suggest the value of this enterprise.

Melanoma continues to be a devastating disease unless diagnosed and treated early. According to the National Cancer Institute, there will be more than 76,000 new cases of invasive melanoma and nearly 10,000 melanoma-related deaths in 2014 in the United States.1 If diagnosed early, more than 93% of melanoma patients can expect to be cured, but later diagnosis of thicker melanoma is associated with a worse prognosis. Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for cutaneous melanoma, including wide excision and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy for staging of the regional nodal basins in appropriate patients. Although novel targeted therapies and immunotherapies have been associated with improved survival in metastatic melanoma, detection of cutaneous melanoma in its early phases remains the best chance for cure.

Tumor thickness, or Breslow depth, is the most important histologic determinant of prognosis in melanoma patients and is measured vertically in millimeters from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of the tumor involvement. Increased tumor thickness confers a higher metastatic potential and poorer prognosis.2 Other histologic prognostic factors that have been incorporated into the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system include the presence or absence of ulceration and mitotic index (measured per square millimeter), particularly for T1 melanomas (<1 mm thick), though Breslow depth greater than 0.75 mm appears to be the most reliable predictor of SLN metastasis in thin (T1) melanomas (≤1 mm).3

Tumor volume assessment may be a helpful adjunct to Breslow depth as a prognostic indicator for melanoma, particularly for predicting SLN metastasis.4 This retrospective study was designed to assess the improvement in the accuracy of Breslow depth as a prognostic factor by utilizing tumor volume combined with mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction (eg, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes).

Methods

The study was approved by the Stanford University (Stanford, California) institutional review board. A retrospective review of invasive primary melanomas recorded in Stanford University’s pathology/dermatopathology database from January 2007 through December 2010 was conducted. Because cases included both Stanford Health Care (formerly Stanford Hospital & Clinics) and outside pathology consultations, clinical assessment of patient outcome was not possible for all cases and thus was not performed.

Assessment

Information extracted from the pathology reports included Breslow depth; estimated surface area of the primary tumor (measured by the longest vertical and horizontal dimensions recorded by the clinician prior to diagnostic biopsy and reported on the biopsy requisition form [>90% of cases] or reported by the pathologist on gross measurement of the pigmented lesion in formalin [<10% of cases]); mitotic index (measured per square millimeter); presence or absence of ulceration; and inflammatory host reaction (as noted by tumor-infiltrating response). Our method of estimating the tumor volume (lesion surface area • Breslow depth) did not take into account border irregularities in the primary tumor. This method also was limited because prebiopsy clinical measurement could differ from gross pathologic measurement of the tumor due to shrinkage of the latter ex vivo and following formalin fixation. However, when both measurements were documented, the pathological measurement was only slightly less than the clinical measurement. Metastases were defined as those in lymph nodes (microscopic or macroscopic), skin, or in distant organs, as identified through review of subsequent pathology reports.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3. Test statistics were preset at a significance level of α=.05. Using metastasis status as the outcome, univariate regression models were first fitted to assess the predictive ability of each prognostic indicator. In univariate analyses, continuous prognostic indicators (Breslow depth, tumor volume, and surface area) were included in the model while seeking the best functional form by means of fractional polynomials modeling.5,6 Predictive ability of prognostic indicators was determined by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).7 Using best functional form for Breslow depth, all other prognostic indicators were added to the model to assess their individual contributions to improve the predictive ability for tumor metastasis. The functional forms used for tumor volume and surface area were those determined in the univariate analysis. Multivariable models were compared aiming for an improvement of the best Breslow model indices: Schwarz criterion, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, generalized R2, and AUC.5 The added contribution of clinical predictors to the model for Breslow depth was judged by the significance of the coefficient for the added clinical predictor, the significance of the change in AUC, and the change in the model indices listed above. A check on overdispersion was carried out on the final model selected.

Results

There were 108 eligible cases in the 4-year time period in which tumor volume assessment could be determined based on the pathology report in conjunction with Breslow depth, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and tumor infiltrating response. Breslow depth ranged from 0.20 to 10.00 mm, with a median depth of 1.37 mm. Surface area ranged from 12.00 to 1720.00 mm2 (median, 100.00 mm2). Tumor volume was calculated by multiplying Breslow depth by surface area and ranged from 2.76 to 11,180.00 mm3 (median, 113.05 mm3)(Table 1). Ulceration was present in 18.69% of the tumors, 20.37% exhibited a brisk inflammatory host reaction, and 53.27% had a mitotic index of 1/mm2 or more. Tumor metastasis was noted in 40.74% (44/108) of patients (Table 2), all of whom had a primary melanoma with a Breslow depth greater than 1 mm. Only one T1 melanoma had a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3. Metastasis in patients with T2 (1- to 2-mm thick) and T3 (2- to 4-mm thick) melanoma was associated with a tumor volume greater than 250 mm3 in 16 of 26 patients (61.54%), and all 18 patients with T4 melanomas (>4-mm thick) had tumor volume greater than 250 mm3.

Univariate analysis demonstrated that Breslow depth was the best prognostic indicator of metastasis (AUC=0.946) but that tumor volume (as a continuous variable) was nearly equally predictive (AUC=0.940)(Table 3). Tumor volume alone (categorized as <250 mm3 vs >250 mm3) had lower prognostic value (AUC=0.855). Mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, inflammatory host reaction, and surface area also had lower prognostic values, though all were significant factors (P values ranging from <.0001 to .0077)(Table 3).

Importantly, the addition of surface area, mitotic index, presence or absence of ulceration, and inflammatory host reaction to the model to Breslow depth did not improve predictive ability for metastasis, and AUC values did not increase significantly after adding these factors (Table 4). In particular, the change in AUC for adding surface area to the model with Breslow depth was 0.023 (P=.1095). Models in Table 4 were checked for interaction of these 2 predictors, and the interaction term for thickness and surface area was not statistically significant (P=.0932)(data not shown).

Comment

Decades after the concept of measuring tumor thickness in cutaneous melanomas was proposed by Dr. Alexander Breslow, it remains the most reliable predictor of prognosis in melanoma patients.2 Our study demonstrated that tumor volume may be contributory to thickness, despite our relatively imprecise assessment of tumor volume based on clinical or pathological reporting of primary tumor area. Because more than 90% of our tumor volume measurements were based on clinician reports of the lesion size before diagnostic biopsy rather than gross measurement of the tumor by the pathologist after biopsy, we believe that measurement and assessment of tumor volume could be readily incorporated into the clinical practice setting. Although we could not demonstrate a correlation between SLN positivity and tumor volume in T1 melanomas because none of the T1 tumors exhibited microscopic nodal metastasis, assessment of tumor volume may assist the clinician in patient management, using a 250-mm3 cutoff point. Gross tumor measurement is important to allow for accurate assessment of volume and would preferably be recorded by the clinician prior to biopsy with notation of clinical lesion size on the pathology requisition form, as is recommended in the American Academy of Dermatology’s melanoma practice guidelines.8

A prior assessment of 123 patients with invasive primary melanomas demonstrated that greater tumor volume (>250 mm3) was associated with metastasis across all tumor thicknesses.4 In T1 melanoma, no patients with a tumor volume less than 250 mm3 demonstrated SLN metastasis,4 suggesting that volume assessment may aid in consideration of staging with SLN biopsy in conjunction with tumor thickness and other established prognostic factors for SLN positivity in thin melanomas (eg, high mitotic index [particularly in tumors >0.75-mm thick]), histologic ulceration, and/or lymphovascular invasion).2,8

It should be noted, however, that lentigo maligna melanoma, which often is predominantly in situ with only focal papillary dermal invasion, may have an erroneously high tumor volume due to its larger total surface area. However, tumor volume would not be expected to correlate with tumor metastasis given the thin invasive component. The current study was limited by not accounting for melanoma subtype in the overall analysis.

A practical estimation of tumor volume based on clinical measurement of tumor size (ie, surface area of the suspicious lesion prior to biopsy) in combination with the pathologist’s assessment of Breslow depth may be a helpful adjunct to predicting likelihood of development of metastasis. We suggest that the concept of tumor volume should be subjected to more rigorous investigation with standardized clinical/prebiopsy measurement of the lesion; correlation with known histologic prognostic factors, SLN positivity, and/or development of additional nodal or visceral metastasis; and most importantly long-term patient outcome in terms of survival. Our preliminary data suggest the value of this enterprise.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:395-407.

4. Walton RG, Velasco C. Volume as a prognostic indicator in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Practical Dermatol. September 2010:26-28.

5. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000.

6. Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model-Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Analysis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

7. Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Vol 28. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2004.

8. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:395-407.

4. Walton RG, Velasco C. Volume as a prognostic indicator in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Practical Dermatol. September 2010:26-28.

5. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000.

6. Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model-Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Analysis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

7. Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Vol 28. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2004.

8. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

Practice Points

- Measurement of melanoma tumor volume using clinical area (length • width of the lesion before diagnostic biopsy) multiplied by Breslow depth may provide additional prognostic information.

- Further study is needed to validate the use of tumor volume as an adjunct to established histopathologic prognostic factors in cutaneous melanoma.

Bilateral Onychodystrophy in a Boy With a History of Isolated Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is a relatively rare and self-limited linear dermatosis of unknown etiology. Lichen striatus primarily affects children, with more than 50% of cases occurring in patients aged 5 to 15 years.1,2 It presents clinically as a single unilateral linear band consisting of scaly, 1- to 3-mm papules that coalesce to form long streaks.3,4 The diagnosis usually is made clinically based on the characteristic appearance of skin lesions and a pattern of distribution that follows the lines of Blaschko.5,6 The papules usually are asymptomatic; however, if the patient is symptomatic, pruritus is the most common concern. Lichen striatus may resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation that may last for several months to years.

Nail involvement is uncommon in LS; a review of the literature has shown that 30 cases have been reported in the world literature since 1941.7 Nail changes may present before, after, or concurrently with the skin lesions.4,8 On rare occasions, nail involvement may be the only area of involvement without the presence of typical skin lesions.8 The involved nails may show longitudinal ridging, splitting, hyperkeratosis of the nail beds, thinning or thickening of the nail plate, nail pitting, and overcurvature of the nail plate, and rarely the nails may fall off completely.8-10

We report the case of a boy who was diagnosed with isolated LS at 2 years of age. The lesions spontaneously resolved within 6 months. Three years later the patient presented with a rare manifestation of LS in the form of bilateral onychodystrophy.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 2-year-old boy presented for evaluation of a nonpruritic linear rash on the right lower side of the abdomen of 3 weeks’ duration. A review of systems was negative for any other constitutional signs or symptoms. No sick contacts were reported at the patient’s home, and his immunizations were up-to-date. His medical history was remarkable for a burn on the left hand from contact with a hot object at 11 months of age that required skin grafting.

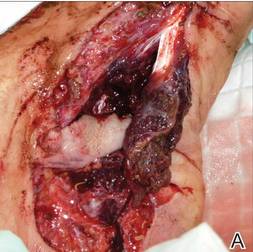

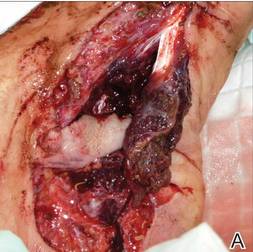

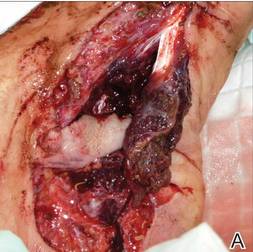

Dermatologic examination revealed a linear band of small, 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored lichenoid papules. Many of the papules had a scaly appearance and some had a vesicular component or were flat topped. The band ranged from 2- to 3-cm wide and was 25 cm in length, extending from the right anterolateral part of the lower abdomen to the right upper lateral part of the buttocks (Figure 1). No abnormalities were noted on the rest of the skin. A diagnosis of LS was made.

|

At 5 years of age, the patient returned for evaluation of bluish discoloration and thinning of the nails of the left middle and ring fingers of several months duration. The patient was afebrile and appeared to be healthy. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatomegaly and the rest of the physical examination by a pediatrician was unremarkable. The nails of the 2 affected fingers had fallen off 2 months prior to presentation and had started to regrow. On dermatologic examination, it was noted that the regrown nails showed some residual longitudinal ridging, thinning, and dark discoloration of the proximal nail folds (Figure 2). On examination of the other toenails and fingernails there was evidence of bilateral pitting, ridging, and discoloration (Figure 3). The left great toenail was predominantly affected. The patient’s guardians were not aware of the toenail changes and denied any history of trauma to the fingers. When asked about the course of the prior abdominal linear rash, they reported that the lesions had completely resolved within 6 months. The rare diagnosis of isolated onychodystrophy as a late manifestation of the prior LS was made.

Comment

The etiology of LS remains unknown, but there have been several hypotheses suggesting environmental triggers such as trauma11 or infection.12 Others have suggested a possible autoimmune response13 or genetic components.6 Reports of simultaneous occurrences of LS in siblings as well as in a mother and her son14,15; outbreaks of LS among children who are not biologically related but in a shared living environment; and a possible seasonal variation suggest an environmental infectious agent (eg, a virus) as the possible triggering factor. However, laboratory testing for viral etiology in LS has not been helpful.

Many of the reported cases of LS have described a pattern of distribution along the lines of Blaschko.5,6,16,17 Lines of Blaschko are thought to be embryologic in origin and caused by the segmental growth of clones of cutaneous cells or the mutation-induced mosaicism of cutaneous cells, which led to the theory that mosaicism is involved in LS. Lichen striatus needs to be differentiated from other conditions with similar cutaneous appearances (eg, lichen nitidus, linear lichen planus of the digits, linear psoriasis, linear keratosis follicularis, linear epidermal nevus).

Skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis rarely is necessary, as LS is a self-limited disorder and generally no treatment is recommended. Topical and intralesional steroids do not routinely impact the resolution of LS; however, emollients and topical steroids may be used to treat associated dryness and pruritus, if present.18 Immunomodulators such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been successfully used in treating persistent and pruritic LS lesions on the face and extremities.19,20 Tacrolimus also has been successfully used to treat nail abnormalities in LS.21

Guardians and family members should be reassured that LS is a benign condition that generally resolves spontaneously within 3 to 12 months. Also, guardians should be counseled regarding the possibility of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, which may last for several months to years, particularly in children with darker skin types. Lichen striatus of the nails may have a more protracted course, lasting from 6 months to 5 years,22 but usually resolves spontaneously and without deformity.

Our patient developed a rare case of isolated LS at 2 years of age. Reports have suggested later onset of the condition, with more than 50% of all LS cases occurring in children aged 5 to 15 years.1,2 Despite the earlier onset in our case, the patient still presented with the classic nonpruritic single linear band of papules that is characteristic of LS.

The nail involvement in our case is quite intriguing because of its rarity, timing, and extent of involvement. Nail involvement is generally uncommon in LS, with approximately 30 cases reported worldwide since 1941.7 The nail changes in our patient were unique in their timing, with the isolated onychodystrophy developing 3 years after the initial skin lesion. This subtle timing may pose a diagnostic challenge in patients with LS if treating physicians are unable to link the presenting onychodystrophy to the earlier cutaneous component of the condition. Two reports have shown that nail changes in association with LS may occur at any time before, after, or concurrently with the skin lesions,4,8 suggesting that on rare occasions, as in our case, nail involvement may be the only area of involvement without the presence of typical LS skin lesions.8

The nail involvement in our patient also showed a greater severity than prior reports,8,9 as he lost 2 fingernails completely before regrowth. Also, the bilateral distribution of onychodystrophy in our patient involving both the fingernails and toenails appeared to be consistent with a report by Al-Niaimi and Cox.22

Nail involvement in cases of LS may be underreported when, as in our case, nail dystrophy presents as the only area of involvement without the presence of the typical skin lesions characteristic of LS. It is reasonable to recommend that clinicians facing similar presentations of isolated onychodystrophy should include the possibility of LS in the differential diagnosis before committing patients to a more common diagnosis (eg, onychomycosis). Clinicians should inquire about any history of cutaneous LS and counsel patients to return for treatment should skin lesions develop that are suggestive of LS.

1. Hofer T. Lichen striatus in adults or ‘adult blaschkitis’? there is no need for a new naming. Dermatology. 2003;207:89-92.

2. Taniguchi Abagge K, Parolin Marinoni L, Giraldi S, et al. Lichen striatus: description of 89 cases in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:440-443.

3. Hauber K, Rose C, Brocker EB, et al. Lichen striatus: clinical features and follow-up in 12 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:536-539.

4. Karp DL, Cohen BA. Onychodystrophy in lichen striatus. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:359-361.

5. Arias-Santiago SA, Sierra Girón-Prieto M, Fernández-Pugnarie MA, et al. Lichen striatus following Blaschko lines [published online ahead of print May 8, 2009]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:76-77.

6. Racette AJ, Adams AD, Kessler SE. Simultaneous lichen striatus in siblings along the same Blaschko line [published online ahead of print February 16, 2009]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:50-54.

7. Markouch I, Clérici T, Saiag P, et al. Lichen striatus with nail dystrophy in an infant. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:883-886.

8. Tosti A, Peluso AM, Misciali C, et al. Nail lichen striatus: clinical features and long-term follow-up of five patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:908-913.

9. Leposavic R, Belsito DV. Onychodystrophy and subungual hyperkeratosis due to lichen striatus. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1099-1100.

10. Baran R, Dupré A, Lauret P, et al. Lichen striatus with nail involvement. report of 4 cases and review of the 4 cases in the literature. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1979;106:885-891.

11. Shepherd V, Lun K, Strutton G. Lichen striatus in an adult following trauma. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:25-28.

12. Hafner C, Landthaler M, Vogt T. Lichen striatus (blaschkitis) following varicella infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1345-1347.

13. Brennand S, Khan S, Chong AH. Lichen striatus in a pregnant woman. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:184-186.

14. Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of lichen striatus in siblings. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:293-295.

15. Yaosaka M, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Lichen striatus affecting a mother and her son. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:352-353.

16. Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding the spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:621-627.

17. Taieb A, el Youbi A, Grosshans E, et al. Lichen striatus: a Blaschko linear acquired inflammatory skin eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:637-642.

18. Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

19. Vukićević J, Milobratović D, Vesić S, et al. Unilateral multiple lichen striatus treated with tacrolimus ointment: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2009;18:35-38.

20. Fujimoto N, Tajima S, Ishibashi A. Facial lichen striatus: successful treatment with tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:587-590.

21. Kim GW, Kim SH, Seo SH, et al. Lichen striatus with nail abnormality successfully treated with tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatol. 2009;36:616-617.

22. Al-Niaimi FA, Cox NH. Unilateral lichen striatus with bilateral onychodystrophy [published online ahead of print June 5, 2009]. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:511.

Lichen striatus (LS) is a relatively rare and self-limited linear dermatosis of unknown etiology. Lichen striatus primarily affects children, with more than 50% of cases occurring in patients aged 5 to 15 years.1,2 It presents clinically as a single unilateral linear band consisting of scaly, 1- to 3-mm papules that coalesce to form long streaks.3,4 The diagnosis usually is made clinically based on the characteristic appearance of skin lesions and a pattern of distribution that follows the lines of Blaschko.5,6 The papules usually are asymptomatic; however, if the patient is symptomatic, pruritus is the most common concern. Lichen striatus may resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation that may last for several months to years.

Nail involvement is uncommon in LS; a review of the literature has shown that 30 cases have been reported in the world literature since 1941.7 Nail changes may present before, after, or concurrently with the skin lesions.4,8 On rare occasions, nail involvement may be the only area of involvement without the presence of typical skin lesions.8 The involved nails may show longitudinal ridging, splitting, hyperkeratosis of the nail beds, thinning or thickening of the nail plate, nail pitting, and overcurvature of the nail plate, and rarely the nails may fall off completely.8-10

We report the case of a boy who was diagnosed with isolated LS at 2 years of age. The lesions spontaneously resolved within 6 months. Three years later the patient presented with a rare manifestation of LS in the form of bilateral onychodystrophy.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 2-year-old boy presented for evaluation of a nonpruritic linear rash on the right lower side of the abdomen of 3 weeks’ duration. A review of systems was negative for any other constitutional signs or symptoms. No sick contacts were reported at the patient’s home, and his immunizations were up-to-date. His medical history was remarkable for a burn on the left hand from contact with a hot object at 11 months of age that required skin grafting.

Dermatologic examination revealed a linear band of small, 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored lichenoid papules. Many of the papules had a scaly appearance and some had a vesicular component or were flat topped. The band ranged from 2- to 3-cm wide and was 25 cm in length, extending from the right anterolateral part of the lower abdomen to the right upper lateral part of the buttocks (Figure 1). No abnormalities were noted on the rest of the skin. A diagnosis of LS was made.

|

At 5 years of age, the patient returned for evaluation of bluish discoloration and thinning of the nails of the left middle and ring fingers of several months duration. The patient was afebrile and appeared to be healthy. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatomegaly and the rest of the physical examination by a pediatrician was unremarkable. The nails of the 2 affected fingers had fallen off 2 months prior to presentation and had started to regrow. On dermatologic examination, it was noted that the regrown nails showed some residual longitudinal ridging, thinning, and dark discoloration of the proximal nail folds (Figure 2). On examination of the other toenails and fingernails there was evidence of bilateral pitting, ridging, and discoloration (Figure 3). The left great toenail was predominantly affected. The patient’s guardians were not aware of the toenail changes and denied any history of trauma to the fingers. When asked about the course of the prior abdominal linear rash, they reported that the lesions had completely resolved within 6 months. The rare diagnosis of isolated onychodystrophy as a late manifestation of the prior LS was made.

Comment

The etiology of LS remains unknown, but there have been several hypotheses suggesting environmental triggers such as trauma11 or infection.12 Others have suggested a possible autoimmune response13 or genetic components.6 Reports of simultaneous occurrences of LS in siblings as well as in a mother and her son14,15; outbreaks of LS among children who are not biologically related but in a shared living environment; and a possible seasonal variation suggest an environmental infectious agent (eg, a virus) as the possible triggering factor. However, laboratory testing for viral etiology in LS has not been helpful.

Many of the reported cases of LS have described a pattern of distribution along the lines of Blaschko.5,6,16,17 Lines of Blaschko are thought to be embryologic in origin and caused by the segmental growth of clones of cutaneous cells or the mutation-induced mosaicism of cutaneous cells, which led to the theory that mosaicism is involved in LS. Lichen striatus needs to be differentiated from other conditions with similar cutaneous appearances (eg, lichen nitidus, linear lichen planus of the digits, linear psoriasis, linear keratosis follicularis, linear epidermal nevus).

Skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis rarely is necessary, as LS is a self-limited disorder and generally no treatment is recommended. Topical and intralesional steroids do not routinely impact the resolution of LS; however, emollients and topical steroids may be used to treat associated dryness and pruritus, if present.18 Immunomodulators such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been successfully used in treating persistent and pruritic LS lesions on the face and extremities.19,20 Tacrolimus also has been successfully used to treat nail abnormalities in LS.21

Guardians and family members should be reassured that LS is a benign condition that generally resolves spontaneously within 3 to 12 months. Also, guardians should be counseled regarding the possibility of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, which may last for several months to years, particularly in children with darker skin types. Lichen striatus of the nails may have a more protracted course, lasting from 6 months to 5 years,22 but usually resolves spontaneously and without deformity.

Our patient developed a rare case of isolated LS at 2 years of age. Reports have suggested later onset of the condition, with more than 50% of all LS cases occurring in children aged 5 to 15 years.1,2 Despite the earlier onset in our case, the patient still presented with the classic nonpruritic single linear band of papules that is characteristic of LS.

The nail involvement in our case is quite intriguing because of its rarity, timing, and extent of involvement. Nail involvement is generally uncommon in LS, with approximately 30 cases reported worldwide since 1941.7 The nail changes in our patient were unique in their timing, with the isolated onychodystrophy developing 3 years after the initial skin lesion. This subtle timing may pose a diagnostic challenge in patients with LS if treating physicians are unable to link the presenting onychodystrophy to the earlier cutaneous component of the condition. Two reports have shown that nail changes in association with LS may occur at any time before, after, or concurrently with the skin lesions,4,8 suggesting that on rare occasions, as in our case, nail involvement may be the only area of involvement without the presence of typical LS skin lesions.8

The nail involvement in our patient also showed a greater severity than prior reports,8,9 as he lost 2 fingernails completely before regrowth. Also, the bilateral distribution of onychodystrophy in our patient involving both the fingernails and toenails appeared to be consistent with a report by Al-Niaimi and Cox.22

Nail involvement in cases of LS may be underreported when, as in our case, nail dystrophy presents as the only area of involvement without the presence of the typical skin lesions characteristic of LS. It is reasonable to recommend that clinicians facing similar presentations of isolated onychodystrophy should include the possibility of LS in the differential diagnosis before committing patients to a more common diagnosis (eg, onychomycosis). Clinicians should inquire about any history of cutaneous LS and counsel patients to return for treatment should skin lesions develop that are suggestive of LS.

Lichen striatus (LS) is a relatively rare and self-limited linear dermatosis of unknown etiology. Lichen striatus primarily affects children, with more than 50% of cases occurring in patients aged 5 to 15 years.1,2 It presents clinically as a single unilateral linear band consisting of scaly, 1- to 3-mm papules that coalesce to form long streaks.3,4 The diagnosis usually is made clinically based on the characteristic appearance of skin lesions and a pattern of distribution that follows the lines of Blaschko.5,6 The papules usually are asymptomatic; however, if the patient is symptomatic, pruritus is the most common concern. Lichen striatus may resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation that may last for several months to years.

Nail involvement is uncommon in LS; a review of the literature has shown that 30 cases have been reported in the world literature since 1941.7 Nail changes may present before, after, or concurrently with the skin lesions.4,8 On rare occasions, nail involvement may be the only area of involvement without the presence of typical skin lesions.8 The involved nails may show longitudinal ridging, splitting, hyperkeratosis of the nail beds, thinning or thickening of the nail plate, nail pitting, and overcurvature of the nail plate, and rarely the nails may fall off completely.8-10

We report the case of a boy who was diagnosed with isolated LS at 2 years of age. The lesions spontaneously resolved within 6 months. Three years later the patient presented with a rare manifestation of LS in the form of bilateral onychodystrophy.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 2-year-old boy presented for evaluation of a nonpruritic linear rash on the right lower side of the abdomen of 3 weeks’ duration. A review of systems was negative for any other constitutional signs or symptoms. No sick contacts were reported at the patient’s home, and his immunizations were up-to-date. His medical history was remarkable for a burn on the left hand from contact with a hot object at 11 months of age that required skin grafting.

Dermatologic examination revealed a linear band of small, 1- to 3-mm, flesh-colored lichenoid papules. Many of the papules had a scaly appearance and some had a vesicular component or were flat topped. The band ranged from 2- to 3-cm wide and was 25 cm in length, extending from the right anterolateral part of the lower abdomen to the right upper lateral part of the buttocks (Figure 1). No abnormalities were noted on the rest of the skin. A diagnosis of LS was made.

|

At 5 years of age, the patient returned for evaluation of bluish discoloration and thinning of the nails of the left middle and ring fingers of several months duration. The patient was afebrile and appeared to be healthy. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatomegaly and the rest of the physical examination by a pediatrician was unremarkable. The nails of the 2 affected fingers had fallen off 2 months prior to presentation and had started to regrow. On dermatologic examination, it was noted that the regrown nails showed some residual longitudinal ridging, thinning, and dark discoloration of the proximal nail folds (Figure 2). On examination of the other toenails and fingernails there was evidence of bilateral pitting, ridging, and discoloration (Figure 3). The left great toenail was predominantly affected. The patient’s guardians were not aware of the toenail changes and denied any history of trauma to the fingers. When asked about the course of the prior abdominal linear rash, they reported that the lesions had completely resolved within 6 months. The rare diagnosis of isolated onychodystrophy as a late manifestation of the prior LS was made.

Comment