User login

Case Report

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with cone-shaped, oyster shell–like skin lesions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He denied any fever, pruritus, pain, joint stiffness, or arthralgia. His family history was remarkable for psoriasis in his paternal grandfather and uncle.

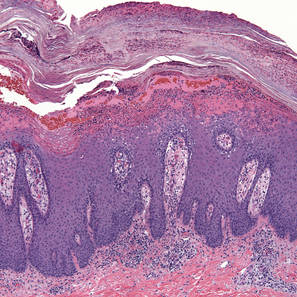

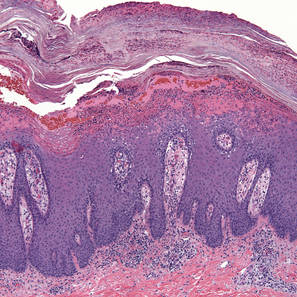

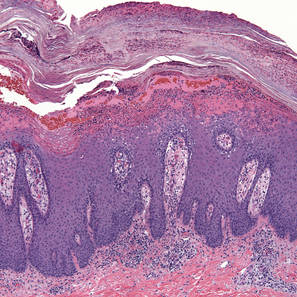

A few years prior to the eruption, the patient developed a rash in the bilateral inguinal area but did not seek medical attention. One month prior to presentation, the rash began to spread to the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. He was treated in the emergency department with a 5-day course of oral prednisone without any noticeable improvement. At the time of presentation to the dermatology clinic, he was found to have multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crusts (Figure 1). Rapid plasma reagin testing was negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right upper arm demonstrated thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (Figure 2). In the stratum corneum, there was seroexudate with numerous red blood cells between the parakeratosis.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with hyperkeratotic crust on the back (A). Closer view of erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crust (B). |

|

| Figure 2. Thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

The patient was diagnosed with rupioid psoriasis. The lesions dramatically improved with methotrexate 10 mg weekly and topical steroids. Two months following diagnosis the patient presented with persistent hyperkeratotic lesions on the back, as he had difficulty reaching the lesions to apply topical medications; intralesional steroid injections were added. This regimen resulted in near-complete resolution maintained at his most recent follow-up 2 years following diagnosis in our clinic.

Comment

Rupia is based on the Greek word rhupos, which means dirt or filth. The term rupioid has been used to describe well-demarcated, cone-shaped plaques with thick, dark, lamellate, and adherent crusts on the skin somewhat resembling oyster or limpet shells. Histologically, a serosanguineous exudate along with thick skin helps to impart a “dirty” appearance to rupioid lesions. Rupioid manifestations have been clinically observed in a variety of diseases, including rupioid psoriasis,1-3 reactive arthritis,4 disseminated histoplasmosis,5 keratotic scabies,6 secondary syphilis,7 and photosensitive skin lesions in association with aminoaciduria.8 To diagnose the underlying infectious or inflammatory diseases beneath the thick crusts, skin biopsy and a blood test for syphilis may be necessary.

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphologic subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble an oyster or limpet shell. Patients with thick plaque psoriasis are more likely to be male with a higher incidence of nail disease and psoriatic arthritis as well as a greater body surface area affected than patients with thin plaque psoriasis.1 Although most cases of rupioid psoriasis were associated with psoriatic arthritis,3 our patient showed no evidence of psoriatic arthritis or nail changes.

Reactive arthritis may have a similar appearance to rupioid psoriasis but may be distinguished by a geographic relief map configuration with coalescing, keratotic and desquamating lesions, as well as associated urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis.4 A rupioid eruption was reported as a manifestation of disseminated histoplasmosis with dirty-appearing, heaped-up, crusted lesions present on the cheeks, nose, and forehead on clinical examination and several intracellular and extracellular oval structures on histologic examination with periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine-silver stain.5 Malignant or rupioid syphilis refers to the stage in which papulopustules of pustular syphilis undergo central necrosis due to endarteritis obliterans and intravascular thrombosis.7

In our case, the patient’s psoriasis could have flared after discontinuation of the prednisone that was administered by the emergency department physician. Most cases have been treated with combined systemic and topical therapy.9 For systemic treatment, cyclosporine, intramuscular or oral methotrexate, adalimumab, and ustekinumab3 have been used with remarkable improvement. Hyperkeratotic types of psoriasis are generally thought to be resistant to topical therapy because of poor penetration of applied agents; however, a case of rupioid psoriasis without arthritis was successfully treated with topical steroids without concomitant systemic medications.2

Conclusion

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphological subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble a limpet shell. Rupioid skin manifestations may be seen in a variety of diseases including rupioid psoriasis, reactive arthritis, disseminated histoplasmosis, keratotic scabies, secondary syphilis, and photosensitive skin lesions associated with aminoaciduria. Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis often requires additional testing such as skin biopsy, skin scraping, and blood tests, and it typically requires systemic therapy for treatment.

1. Christensen TE, Callis KP, Papenfuss J, et al. Observations of psoriasis in the absence of therapeutic intervention identifies two unappreciated morphologic variants, thin-plaque and thick-plaque psoriasis, and their associated phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2397-2403.

2. Feldman SR, Brown KL, Heald P. ‘Coral reef’ psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

3. Necas M, Vasku V. Ustekinumab in the treatment of severe rupioid psoriasis: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2010;19:23-27.

4. Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter’s disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

5. Corti M, Villafañe MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

6. Costa JB, Rocha de Sousa VL, da Trindade Neto PB, et al. Norwegian scabies mimicking rupioid psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:910-913.

7. Bhagwat PV, Tophakhane RS, Rathod RM, et al. Rupioid syphilis in an HIV patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 2009;75:201-202.

8. Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

9. Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with cone-shaped, oyster shell–like skin lesions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He denied any fever, pruritus, pain, joint stiffness, or arthralgia. His family history was remarkable for psoriasis in his paternal grandfather and uncle.

A few years prior to the eruption, the patient developed a rash in the bilateral inguinal area but did not seek medical attention. One month prior to presentation, the rash began to spread to the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. He was treated in the emergency department with a 5-day course of oral prednisone without any noticeable improvement. At the time of presentation to the dermatology clinic, he was found to have multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crusts (Figure 1). Rapid plasma reagin testing was negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right upper arm demonstrated thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (Figure 2). In the stratum corneum, there was seroexudate with numerous red blood cells between the parakeratosis.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with hyperkeratotic crust on the back (A). Closer view of erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crust (B). |

|

| Figure 2. Thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

The patient was diagnosed with rupioid psoriasis. The lesions dramatically improved with methotrexate 10 mg weekly and topical steroids. Two months following diagnosis the patient presented with persistent hyperkeratotic lesions on the back, as he had difficulty reaching the lesions to apply topical medications; intralesional steroid injections were added. This regimen resulted in near-complete resolution maintained at his most recent follow-up 2 years following diagnosis in our clinic.

Comment

Rupia is based on the Greek word rhupos, which means dirt or filth. The term rupioid has been used to describe well-demarcated, cone-shaped plaques with thick, dark, lamellate, and adherent crusts on the skin somewhat resembling oyster or limpet shells. Histologically, a serosanguineous exudate along with thick skin helps to impart a “dirty” appearance to rupioid lesions. Rupioid manifestations have been clinically observed in a variety of diseases, including rupioid psoriasis,1-3 reactive arthritis,4 disseminated histoplasmosis,5 keratotic scabies,6 secondary syphilis,7 and photosensitive skin lesions in association with aminoaciduria.8 To diagnose the underlying infectious or inflammatory diseases beneath the thick crusts, skin biopsy and a blood test for syphilis may be necessary.

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphologic subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble an oyster or limpet shell. Patients with thick plaque psoriasis are more likely to be male with a higher incidence of nail disease and psoriatic arthritis as well as a greater body surface area affected than patients with thin plaque psoriasis.1 Although most cases of rupioid psoriasis were associated with psoriatic arthritis,3 our patient showed no evidence of psoriatic arthritis or nail changes.

Reactive arthritis may have a similar appearance to rupioid psoriasis but may be distinguished by a geographic relief map configuration with coalescing, keratotic and desquamating lesions, as well as associated urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis.4 A rupioid eruption was reported as a manifestation of disseminated histoplasmosis with dirty-appearing, heaped-up, crusted lesions present on the cheeks, nose, and forehead on clinical examination and several intracellular and extracellular oval structures on histologic examination with periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine-silver stain.5 Malignant or rupioid syphilis refers to the stage in which papulopustules of pustular syphilis undergo central necrosis due to endarteritis obliterans and intravascular thrombosis.7

In our case, the patient’s psoriasis could have flared after discontinuation of the prednisone that was administered by the emergency department physician. Most cases have been treated with combined systemic and topical therapy.9 For systemic treatment, cyclosporine, intramuscular or oral methotrexate, adalimumab, and ustekinumab3 have been used with remarkable improvement. Hyperkeratotic types of psoriasis are generally thought to be resistant to topical therapy because of poor penetration of applied agents; however, a case of rupioid psoriasis without arthritis was successfully treated with topical steroids without concomitant systemic medications.2

Conclusion

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphological subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble a limpet shell. Rupioid skin manifestations may be seen in a variety of diseases including rupioid psoriasis, reactive arthritis, disseminated histoplasmosis, keratotic scabies, secondary syphilis, and photosensitive skin lesions associated with aminoaciduria. Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis often requires additional testing such as skin biopsy, skin scraping, and blood tests, and it typically requires systemic therapy for treatment.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with cone-shaped, oyster shell–like skin lesions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He denied any fever, pruritus, pain, joint stiffness, or arthralgia. His family history was remarkable for psoriasis in his paternal grandfather and uncle.

A few years prior to the eruption, the patient developed a rash in the bilateral inguinal area but did not seek medical attention. One month prior to presentation, the rash began to spread to the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. He was treated in the emergency department with a 5-day course of oral prednisone without any noticeable improvement. At the time of presentation to the dermatology clinic, he was found to have multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crusts (Figure 1). Rapid plasma reagin testing was negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the right upper arm demonstrated thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (Figure 2). In the stratum corneum, there was seroexudate with numerous red blood cells between the parakeratosis.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with hyperkeratotic crust on the back (A). Closer view of erythematous plaques with conical, oyster shell–like, dirty-appearing, hyperkeratotic crust (B). |

|

| Figure 2. Thick parakeratosis with a remarkable Munro microabscess, regular psoriasiform acanthosis with thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, and prominent papillary dermal edema (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

The patient was diagnosed with rupioid psoriasis. The lesions dramatically improved with methotrexate 10 mg weekly and topical steroids. Two months following diagnosis the patient presented with persistent hyperkeratotic lesions on the back, as he had difficulty reaching the lesions to apply topical medications; intralesional steroid injections were added. This regimen resulted in near-complete resolution maintained at his most recent follow-up 2 years following diagnosis in our clinic.

Comment

Rupia is based on the Greek word rhupos, which means dirt or filth. The term rupioid has been used to describe well-demarcated, cone-shaped plaques with thick, dark, lamellate, and adherent crusts on the skin somewhat resembling oyster or limpet shells. Histologically, a serosanguineous exudate along with thick skin helps to impart a “dirty” appearance to rupioid lesions. Rupioid manifestations have been clinically observed in a variety of diseases, including rupioid psoriasis,1-3 reactive arthritis,4 disseminated histoplasmosis,5 keratotic scabies,6 secondary syphilis,7 and photosensitive skin lesions in association with aminoaciduria.8 To diagnose the underlying infectious or inflammatory diseases beneath the thick crusts, skin biopsy and a blood test for syphilis may be necessary.

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphologic subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble an oyster or limpet shell. Patients with thick plaque psoriasis are more likely to be male with a higher incidence of nail disease and psoriatic arthritis as well as a greater body surface area affected than patients with thin plaque psoriasis.1 Although most cases of rupioid psoriasis were associated with psoriatic arthritis,3 our patient showed no evidence of psoriatic arthritis or nail changes.

Reactive arthritis may have a similar appearance to rupioid psoriasis but may be distinguished by a geographic relief map configuration with coalescing, keratotic and desquamating lesions, as well as associated urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis.4 A rupioid eruption was reported as a manifestation of disseminated histoplasmosis with dirty-appearing, heaped-up, crusted lesions present on the cheeks, nose, and forehead on clinical examination and several intracellular and extracellular oval structures on histologic examination with periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine-silver stain.5 Malignant or rupioid syphilis refers to the stage in which papulopustules of pustular syphilis undergo central necrosis due to endarteritis obliterans and intravascular thrombosis.7

In our case, the patient’s psoriasis could have flared after discontinuation of the prednisone that was administered by the emergency department physician. Most cases have been treated with combined systemic and topical therapy.9 For systemic treatment, cyclosporine, intramuscular or oral methotrexate, adalimumab, and ustekinumab3 have been used with remarkable improvement. Hyperkeratotic types of psoriasis are generally thought to be resistant to topical therapy because of poor penetration of applied agents; however, a case of rupioid psoriasis without arthritis was successfully treated with topical steroids without concomitant systemic medications.2

Conclusion

Rupioid psoriasis is a morphological subtype of plaque psoriasis with hyperkeratotic lesions that resemble a limpet shell. Rupioid skin manifestations may be seen in a variety of diseases including rupioid psoriasis, reactive arthritis, disseminated histoplasmosis, keratotic scabies, secondary syphilis, and photosensitive skin lesions associated with aminoaciduria. Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis often requires additional testing such as skin biopsy, skin scraping, and blood tests, and it typically requires systemic therapy for treatment.

1. Christensen TE, Callis KP, Papenfuss J, et al. Observations of psoriasis in the absence of therapeutic intervention identifies two unappreciated morphologic variants, thin-plaque and thick-plaque psoriasis, and their associated phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2397-2403.

2. Feldman SR, Brown KL, Heald P. ‘Coral reef’ psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

3. Necas M, Vasku V. Ustekinumab in the treatment of severe rupioid psoriasis: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2010;19:23-27.

4. Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter’s disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

5. Corti M, Villafañe MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

6. Costa JB, Rocha de Sousa VL, da Trindade Neto PB, et al. Norwegian scabies mimicking rupioid psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:910-913.

7. Bhagwat PV, Tophakhane RS, Rathod RM, et al. Rupioid syphilis in an HIV patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 2009;75:201-202.

8. Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

9. Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

1. Christensen TE, Callis KP, Papenfuss J, et al. Observations of psoriasis in the absence of therapeutic intervention identifies two unappreciated morphologic variants, thin-plaque and thick-plaque psoriasis, and their associated phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2397-2403.

2. Feldman SR, Brown KL, Heald P. ‘Coral reef’ psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

3. Necas M, Vasku V. Ustekinumab in the treatment of severe rupioid psoriasis: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2010;19:23-27.

4. Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter’s disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

5. Corti M, Villafañe MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

6. Costa JB, Rocha de Sousa VL, da Trindade Neto PB, et al. Norwegian scabies mimicking rupioid psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:910-913.

7. Bhagwat PV, Tophakhane RS, Rathod RM, et al. Rupioid syphilis in an HIV patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 2009;75:201-202.

8. Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

9. Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Diseases with rupioid manifestations include rupioid psoriasis, reactive arthritis, disseminated histoplasmosis, keratotic scabies, secondary syphilis, and photosensitive skin lesions associated with aminoaciduria.

- Skin biopsy, skin scraping, and blood tests may be necessary to diagnose the underlying diseases beneath the thick crusts and to rule out other diagnoses within the differential.

- Treatment of rupioid psoriasis is no different than typical plaque psoriasis, except for the need for systemic therapy in most cases due to the thick scale.