User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Practice Question Answers: Vulvar Diseases, Part 1

1. The risk for subsequently developing squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the vulva is most strongly associated with:

a. candidiasis

b. cicatricial pemphigoid

c. lichen planus

d. lichen sclerosus

e. recurrent Trichomonas infections

2. Vitamin D supplements and topical antibiotics commonly are used to treat:

a. desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. human papillomavirus–related severe squamous dysplasia of the vulva and vagina

d. lichen sclerosus

e. psoriasis

3. A 28-year-old diabetic woman presented to your clinic with well-developed vulvar pruritus. She was known to have an implanted copper intrauterine device. A Papanicolaou test would most likely reveal:

a. bacteria

b. herpetic virocytes

c. high-grade dysplastic squamous cells

d. koilocytic squamous cells

e. pseudohyphae

4. A 54-year-old woman with Sjögren syndrome and atrophic gastritis presented to your clinic with vulvar pruritus. Atrophy of the skin and mucosa with fissures was clinically suggestive of:

a. candidiasis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. lichen sclerosus

d. lichen simplex chronicus

e. psoriasis

5. A 48-year-old woman was referred to your clinic for evaluation of persistent burning vulvar pain of 3 months’ duration. She said she felt tired most of the time. On physical examination the vulva looked normal. Commonly this condition is associated with:

a. diabetes mellitus

b. fibromyalgia

c. hypothyroidism

d. iron deficiency anemia

e. psoriasis

1. The risk for subsequently developing squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the vulva is most strongly associated with:

a. candidiasis

b. cicatricial pemphigoid

c. lichen planus

d. lichen sclerosus

e. recurrent Trichomonas infections

2. Vitamin D supplements and topical antibiotics commonly are used to treat:

a. desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. human papillomavirus–related severe squamous dysplasia of the vulva and vagina

d. lichen sclerosus

e. psoriasis

3. A 28-year-old diabetic woman presented to your clinic with well-developed vulvar pruritus. She was known to have an implanted copper intrauterine device. A Papanicolaou test would most likely reveal:

a. bacteria

b. herpetic virocytes

c. high-grade dysplastic squamous cells

d. koilocytic squamous cells

e. pseudohyphae

4. A 54-year-old woman with Sjögren syndrome and atrophic gastritis presented to your clinic with vulvar pruritus. Atrophy of the skin and mucosa with fissures was clinically suggestive of:

a. candidiasis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. lichen sclerosus

d. lichen simplex chronicus

e. psoriasis

5. A 48-year-old woman was referred to your clinic for evaluation of persistent burning vulvar pain of 3 months’ duration. She said she felt tired most of the time. On physical examination the vulva looked normal. Commonly this condition is associated with:

a. diabetes mellitus

b. fibromyalgia

c. hypothyroidism

d. iron deficiency anemia

e. psoriasis

1. The risk for subsequently developing squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the vulva is most strongly associated with:

a. candidiasis

b. cicatricial pemphigoid

c. lichen planus

d. lichen sclerosus

e. recurrent Trichomonas infections

2. Vitamin D supplements and topical antibiotics commonly are used to treat:

a. desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. human papillomavirus–related severe squamous dysplasia of the vulva and vagina

d. lichen sclerosus

e. psoriasis

3. A 28-year-old diabetic woman presented to your clinic with well-developed vulvar pruritus. She was known to have an implanted copper intrauterine device. A Papanicolaou test would most likely reveal:

a. bacteria

b. herpetic virocytes

c. high-grade dysplastic squamous cells

d. koilocytic squamous cells

e. pseudohyphae

4. A 54-year-old woman with Sjögren syndrome and atrophic gastritis presented to your clinic with vulvar pruritus. Atrophy of the skin and mucosa with fissures was clinically suggestive of:

a. candidiasis

b. dysesthetic vulvodynia

c. lichen sclerosus

d. lichen simplex chronicus

e. psoriasis

5. A 48-year-old woman was referred to your clinic for evaluation of persistent burning vulvar pain of 3 months’ duration. She said she felt tired most of the time. On physical examination the vulva looked normal. Commonly this condition is associated with:

a. diabetes mellitus

b. fibromyalgia

c. hypothyroidism

d. iron deficiency anemia

e. psoriasis

Vulvar Diseases, Part 1

Reducing Risks

Psoriasis is associated with multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases. With the advent of anti-inflammatory therapy, there has been much investigation into whether treatments for psoriasis may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events. In a Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology article published online on October 10, Ahlehoff et al examined the rate of cardiovascular events—cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke—in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs.

Individual-level linkage of administrative registries was utilized to perform a longitudinal nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Time-dependent multivariable adjusted Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of cardiovascular events associated with use of biological drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, and other antipsoriatic therapies (ie, topical treatments, phototherapy, climate therapy).

The investigators included a total of 6902 patients (9662 treatment exposures) with a maximum follow-up of 5 years. Incidence rates per 1000 patient-years for cardiovascular events were highest for retinoids and other therapies (18.95 and 14.63, respectively) followed by methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biological drugs (6.28, 6.08, and 4.16, respectively). Relative to other therapies, methotrexate (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34-0.83) was associated with reduced risk for the composite end point. A comparable but nonsignificant protective effect was observed with biological drugs (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.30-1.10), whereas no protective effect was apparent with cyclosporine (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.26-4.27) and retinoids (HR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.03-2.96). Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22-0.98) were linked to reduced event rates but the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.47-4.94) was not.

The authors concluded that systemic anti-inflammatory treatment with methotrexate was associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events during long-term follow-up compared to patients treated with other antipsoriatic therapies.

What’s the issue?

This study is consistent with other investigations evaluating the cardioprotective benefit of therapies for psoriasis. The cardioprotective benefits of methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been previously reported. Further investigation will help to elucidate the role of these drugs as well as newer therapies in the reduction of comorbidities. Does this study influence your perception of therapies for psoriasis?

Psoriasis is associated with multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases. With the advent of anti-inflammatory therapy, there has been much investigation into whether treatments for psoriasis may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events. In a Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology article published online on October 10, Ahlehoff et al examined the rate of cardiovascular events—cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke—in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs.

Individual-level linkage of administrative registries was utilized to perform a longitudinal nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Time-dependent multivariable adjusted Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of cardiovascular events associated with use of biological drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, and other antipsoriatic therapies (ie, topical treatments, phototherapy, climate therapy).

The investigators included a total of 6902 patients (9662 treatment exposures) with a maximum follow-up of 5 years. Incidence rates per 1000 patient-years for cardiovascular events were highest for retinoids and other therapies (18.95 and 14.63, respectively) followed by methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biological drugs (6.28, 6.08, and 4.16, respectively). Relative to other therapies, methotrexate (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34-0.83) was associated with reduced risk for the composite end point. A comparable but nonsignificant protective effect was observed with biological drugs (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.30-1.10), whereas no protective effect was apparent with cyclosporine (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.26-4.27) and retinoids (HR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.03-2.96). Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22-0.98) were linked to reduced event rates but the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.47-4.94) was not.

The authors concluded that systemic anti-inflammatory treatment with methotrexate was associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events during long-term follow-up compared to patients treated with other antipsoriatic therapies.

What’s the issue?

This study is consistent with other investigations evaluating the cardioprotective benefit of therapies for psoriasis. The cardioprotective benefits of methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been previously reported. Further investigation will help to elucidate the role of these drugs as well as newer therapies in the reduction of comorbidities. Does this study influence your perception of therapies for psoriasis?

Psoriasis is associated with multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases. With the advent of anti-inflammatory therapy, there has been much investigation into whether treatments for psoriasis may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events. In a Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology article published online on October 10, Ahlehoff et al examined the rate of cardiovascular events—cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke—in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs.

Individual-level linkage of administrative registries was utilized to perform a longitudinal nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Time-dependent multivariable adjusted Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of cardiovascular events associated with use of biological drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, and other antipsoriatic therapies (ie, topical treatments, phototherapy, climate therapy).

The investigators included a total of 6902 patients (9662 treatment exposures) with a maximum follow-up of 5 years. Incidence rates per 1000 patient-years for cardiovascular events were highest for retinoids and other therapies (18.95 and 14.63, respectively) followed by methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biological drugs (6.28, 6.08, and 4.16, respectively). Relative to other therapies, methotrexate (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34-0.83) was associated with reduced risk for the composite end point. A comparable but nonsignificant protective effect was observed with biological drugs (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.30-1.10), whereas no protective effect was apparent with cyclosporine (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.26-4.27) and retinoids (HR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.03-2.96). Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22-0.98) were linked to reduced event rates but the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.47-4.94) was not.

The authors concluded that systemic anti-inflammatory treatment with methotrexate was associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events during long-term follow-up compared to patients treated with other antipsoriatic therapies.

What’s the issue?

This study is consistent with other investigations evaluating the cardioprotective benefit of therapies for psoriasis. The cardioprotective benefits of methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been previously reported. Further investigation will help to elucidate the role of these drugs as well as newer therapies in the reduction of comorbidities. Does this study influence your perception of therapies for psoriasis?

Recent Findings About Cardiovascular Comorbidities

Psoriasis Patients Have a Higher Risk for Myocardial Infarction

To determine if psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for myocardial infarction (MI), Wu et al (J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.952609) performed a retrospective cohort study of 50,865 control patients matched to 10,173 patients with mild psoriasis and 19,205 control patients matched to 3841 patients with severe psoriasis. Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with mild and severe psoriasis had a higher risk for MI compared to matched control patients.

Practice Point: Psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for MI compared to control patients.

>>Read more at Journal of Dermatological Treatment

Screen Children With Psoriasis for Cardiovascular Comorbidities

Most evidence of the cardiovascular effects on psoriasis patients has focused on adults. Torres et al (Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:229-235) evaluated the prevalence of excess adiposity, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and lipid profile in children with psoriasis (age range, 5–15 years) compared to a control group. Children with psoriasis had a higher prevalence and greater odds of excess adiposity compared to controls. A higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome also was observed in children with psoriasis compared to controls.

Practice Point: Cardiovascular comorbidities known to be associated with adult psoriasis also are observed in children with psoriasis, warranting the need to screen children with psoriasis and promote healthy lifestyle choices.

>>Read more at European Journal of Dermatology

Psoriasis Patients Have a Greater Risk for Heart Failure

Khalid et al (Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:743-748) investigated the risk for new-onset heart failure in a nationwide cohort of psoriasis patients. They found that the overall incidence rates of new-onset heart failure were higher for patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Compared with the reference population, the fully adjusted hazard ratios for new-onset heart failure were increased in patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Practice Point: Psoriasis may be associated with a disease severity–dependent increased risk for new-onset heart failure.

>>Read more at European Journal of Heart Failure

Psoriasis Patients Have a Higher Risk for Myocardial Infarction

To determine if psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for myocardial infarction (MI), Wu et al (J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.952609) performed a retrospective cohort study of 50,865 control patients matched to 10,173 patients with mild psoriasis and 19,205 control patients matched to 3841 patients with severe psoriasis. Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with mild and severe psoriasis had a higher risk for MI compared to matched control patients.

Practice Point: Psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for MI compared to control patients.

>>Read more at Journal of Dermatological Treatment

Screen Children With Psoriasis for Cardiovascular Comorbidities

Most evidence of the cardiovascular effects on psoriasis patients has focused on adults. Torres et al (Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:229-235) evaluated the prevalence of excess adiposity, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and lipid profile in children with psoriasis (age range, 5–15 years) compared to a control group. Children with psoriasis had a higher prevalence and greater odds of excess adiposity compared to controls. A higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome also was observed in children with psoriasis compared to controls.

Practice Point: Cardiovascular comorbidities known to be associated with adult psoriasis also are observed in children with psoriasis, warranting the need to screen children with psoriasis and promote healthy lifestyle choices.

>>Read more at European Journal of Dermatology

Psoriasis Patients Have a Greater Risk for Heart Failure

Khalid et al (Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:743-748) investigated the risk for new-onset heart failure in a nationwide cohort of psoriasis patients. They found that the overall incidence rates of new-onset heart failure were higher for patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Compared with the reference population, the fully adjusted hazard ratios for new-onset heart failure were increased in patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Practice Point: Psoriasis may be associated with a disease severity–dependent increased risk for new-onset heart failure.

>>Read more at European Journal of Heart Failure

Psoriasis Patients Have a Higher Risk for Myocardial Infarction

To determine if psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for myocardial infarction (MI), Wu et al (J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.952609) performed a retrospective cohort study of 50,865 control patients matched to 10,173 patients with mild psoriasis and 19,205 control patients matched to 3841 patients with severe psoriasis. Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with mild and severe psoriasis had a higher risk for MI compared to matched control patients.

Practice Point: Psoriasis is associated with a higher risk for MI compared to control patients.

>>Read more at Journal of Dermatological Treatment

Screen Children With Psoriasis for Cardiovascular Comorbidities

Most evidence of the cardiovascular effects on psoriasis patients has focused on adults. Torres et al (Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:229-235) evaluated the prevalence of excess adiposity, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and lipid profile in children with psoriasis (age range, 5–15 years) compared to a control group. Children with psoriasis had a higher prevalence and greater odds of excess adiposity compared to controls. A higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome also was observed in children with psoriasis compared to controls.

Practice Point: Cardiovascular comorbidities known to be associated with adult psoriasis also are observed in children with psoriasis, warranting the need to screen children with psoriasis and promote healthy lifestyle choices.

>>Read more at European Journal of Dermatology

Psoriasis Patients Have a Greater Risk for Heart Failure

Khalid et al (Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:743-748) investigated the risk for new-onset heart failure in a nationwide cohort of psoriasis patients. They found that the overall incidence rates of new-onset heart failure were higher for patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Compared with the reference population, the fully adjusted hazard ratios for new-onset heart failure were increased in patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Practice Point: Psoriasis may be associated with a disease severity–dependent increased risk for new-onset heart failure.

>>Read more at European Journal of Heart Failure

Erythematous Seropurulent Ulcerations

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

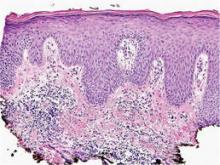

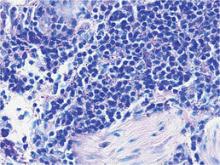

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

A 34-year-old male veteran who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple ulcerated skin lesions on the left arm and forearm as well as the chest. After returning to the United States from being stationed in Qatar and Saudi Arabia, he noticed multiple “bug bites” on the left arm that eventually progressed to larger crusted ulcerations. He denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, tenderness, or any other symptoms. He had been given doxycycline for a possible bacterial infection, but the lesions did not improve.

At Last? Apremilast

In late September 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the medication apremilast for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. It was previously approved for psoriatic arthritis in March 2014. Its mechanism includes selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4, resulting in increased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, indirectly mediating production of inflammatory mediators in many cell types, namely decreasing tumor necrosis factor α and IL-23 and increasing IL-10. Orally dosed at 30 mg twice daily, safety and efficacy was determined via 2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 (N=1257)—that highlighted a PASI-75 (psoriasis area severity index) in 30% of patients in the first 4 months and up to 88% of patients with PASI-75 in the first year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(suppl 1):AB164). Additionally, according to results presented at a recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in early October 2014, pruritus and difficult areas such as the scalp, palmoplantar area, and nails showed significant improvement at week 16 (P<.0001). The most common side effects were diarrhea, nausea, upper respiratory infection, and headache, which occurred most often in the first 2 weeks of therapy. The medication does not require routine laboratory monitoring; however, because weight loss is possible, it is recommended that weight should be periodically checked. There are no contraindications aside from hypersensitivity to the drug itself, and caution should be taken in patients with unstable depression, suicidal ideation, or severe renal impairment. It is pregnancy category C.

What’s the issue?

Because it is administered orally; is dually indicated for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis; and does not require laboratory monitoring, alcohol consumption restrictions, category X classification, or immunosuppressive infection or cancer risk, the window-shopping appeal of this drug seems attractive compared to the veteran and contemporary pharmaceutical army of psoriasis therapy. However, based on the ESTEEM studies, meager apremilast PASI scores are not blowing us away like those of biologic medications. At a time when the evolution of medications for psoriasis seems like a revolving door for new products highlighting new mechanisms in new pathways in even newer cells in relationship to inflammation, how will this drug fit in?

In late September 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the medication apremilast for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. It was previously approved for psoriatic arthritis in March 2014. Its mechanism includes selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4, resulting in increased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, indirectly mediating production of inflammatory mediators in many cell types, namely decreasing tumor necrosis factor α and IL-23 and increasing IL-10. Orally dosed at 30 mg twice daily, safety and efficacy was determined via 2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 (N=1257)—that highlighted a PASI-75 (psoriasis area severity index) in 30% of patients in the first 4 months and up to 88% of patients with PASI-75 in the first year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(suppl 1):AB164). Additionally, according to results presented at a recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in early October 2014, pruritus and difficult areas such as the scalp, palmoplantar area, and nails showed significant improvement at week 16 (P<.0001). The most common side effects were diarrhea, nausea, upper respiratory infection, and headache, which occurred most often in the first 2 weeks of therapy. The medication does not require routine laboratory monitoring; however, because weight loss is possible, it is recommended that weight should be periodically checked. There are no contraindications aside from hypersensitivity to the drug itself, and caution should be taken in patients with unstable depression, suicidal ideation, or severe renal impairment. It is pregnancy category C.

What’s the issue?

Because it is administered orally; is dually indicated for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis; and does not require laboratory monitoring, alcohol consumption restrictions, category X classification, or immunosuppressive infection or cancer risk, the window-shopping appeal of this drug seems attractive compared to the veteran and contemporary pharmaceutical army of psoriasis therapy. However, based on the ESTEEM studies, meager apremilast PASI scores are not blowing us away like those of biologic medications. At a time when the evolution of medications for psoriasis seems like a revolving door for new products highlighting new mechanisms in new pathways in even newer cells in relationship to inflammation, how will this drug fit in?

In late September 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the medication apremilast for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. It was previously approved for psoriatic arthritis in March 2014. Its mechanism includes selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4, resulting in increased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, indirectly mediating production of inflammatory mediators in many cell types, namely decreasing tumor necrosis factor α and IL-23 and increasing IL-10. Orally dosed at 30 mg twice daily, safety and efficacy was determined via 2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 (N=1257)—that highlighted a PASI-75 (psoriasis area severity index) in 30% of patients in the first 4 months and up to 88% of patients with PASI-75 in the first year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(suppl 1):AB164). Additionally, according to results presented at a recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in early October 2014, pruritus and difficult areas such as the scalp, palmoplantar area, and nails showed significant improvement at week 16 (P<.0001). The most common side effects were diarrhea, nausea, upper respiratory infection, and headache, which occurred most often in the first 2 weeks of therapy. The medication does not require routine laboratory monitoring; however, because weight loss is possible, it is recommended that weight should be periodically checked. There are no contraindications aside from hypersensitivity to the drug itself, and caution should be taken in patients with unstable depression, suicidal ideation, or severe renal impairment. It is pregnancy category C.

What’s the issue?

Because it is administered orally; is dually indicated for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis; and does not require laboratory monitoring, alcohol consumption restrictions, category X classification, or immunosuppressive infection or cancer risk, the window-shopping appeal of this drug seems attractive compared to the veteran and contemporary pharmaceutical army of psoriasis therapy. However, based on the ESTEEM studies, meager apremilast PASI scores are not blowing us away like those of biologic medications. At a time when the evolution of medications for psoriasis seems like a revolving door for new products highlighting new mechanisms in new pathways in even newer cells in relationship to inflammation, how will this drug fit in?

Learning Dermatopathology in the Digital Age

As in the study of clinical dermatology, establishing a strong fund of knowledge regarding dermatopathology requires visual exposure to countless representative cases. In the not-so-distant past, textbooks relied on grayscale representations to illustrate these diagnoses, but residents today enjoy full-color images; however, textbooks lack the plasticity of digital media, which allow for more immersive interaction with the content. With technological advances in whole-slide imaging, teaching cases can be saved and shared, and rare diagnoses can be studied by individuals who are far removed from the original specimen.1 Even more exciting is that many of the applications (apps) that facilitate digital learning of dermatopathology are available free of charge. In this article, I will review some of the available apps, focusing on their usability, content, and utility as a learning resource for dermatologists at all stages of training. They are discussed in the order of their utility to students of dermatopathology. I have no financial ties to any of the products reviewed, and my recommendations reflect my opinions and observations after real-world use.

Winner: Clearpath

The Clearpath app (http://www.dermpathlab.com/clearpath/) is a fantastic representation of well-executed digital pathology software. Initially released for $50.00 in 2013, the app has since become free while maintaining a steady stream of updates and expanded content. The app is incredibly intuitive and easy to use, made possible by its modern user interface and versatile search function (Figure). For those just beginning to learn dermatopathology, the glossary contains well-written definitions as well as images, which have highlighting that can be toggled on and off to show an area of interest; for instance, if you cannot wrap your mind around the concept of a “grenz zone,” the app can highlight and focus your attention on the respective area in a related image. The app’s library contains more than 250 diagnoses; by clicking on a diagnosis, you are first shown several images displaying features of the pathology identified with highlighting. Then you can study a digital slide as if your tablet was a microscope stage, panning and zooming as you choose. When you are comfortable with the slides, the integrated quiz mode allows for board review with up to 25 answer choices per slide. Although Clearpath’s image-intensive program does require a wireless connection, it also offers the ability to download slides for offline review.

The app has few notable shortcomings related mostly to compatibility, as it is only available for download from the Apple App Store for iPad. Additionally, in comparison to other programs, there is a relative paucity of pathology images to look at, though new diagnoses frequently are added. Regardless, for those with iPads, it is the most refined introduction to a digital dermatopathology product, and a must-have download.

Runner-up: myDermPath

In my February 2014 column,2 I interviewed Dirk M. Elston, MD, and we briefly discussed the myDermPath app (http://mydermpath.com/), which had just recently been made available for free. The myDermPath app excels in the sheer volume of diagnoses it presents—more than 1000 in all—including more unusual pathologic entities. Physicians looking for images of barnyard pox or inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, for example, do not need to go any further. The pathologic images presented are accompanied by coherent descriptions of clinical features and usually are supplemented with clinical photographs. Furthermore, the app includes a video primer on normal histology narrated by Dr. Elston, a step-by-step algorithm for arriving at a diagnosis, and detailed descriptions of immunofluorescence studies and stains. These additional features make myDermPath a more comprehensive application and a more useful reference source. Its universal compatibility on a range of digital devices makes access to myDermPath convenient for users on any platform (ie, iOS, Android, Web).

The app’s most notable limitation is that, at the time of this writing, it feels somewhat less polished, especially compared to the Clearpath app. This antiquated feel also is evident in the app’s apparent instability on my smartphone, as it frequently stops responding while I am navigating through the menus or looking at histology and often makes it cumbersome to use. This stability issue is not evident on the Web-based version. The app also does not fully support the larger screen sizes of some of the newer smartphones, and therefore the display includes wasted dead space. These faults aside, the volume of material presented and the app’s comprehensive content still make myDermPath a useful addition to your digital dermatopathology repertoire.

Honorable Mention: Derm In-Review

Derm In-Review (http://dermatologyinreview.com/Merz) is sponsored by Merz Pharma and is well known as a broad-reaching resource that reviews the entire breadth of our field for those preparing for in-service or the boards examination. To learn dermatopathology, there are 2 ways to access the digital images: through the Web-based interface and via the mobile app (compatible with iOS and Android). The slides are not categorized but rather are presented in a random order to facilitate quiz taking. The slide images are only photographs of individual features and are not meant to be manipulated as true digital slides; however, the images are good representations of diagnoses, and short descriptions help with learning histologic features. Currently, Aurora Diagnostics (Woodbury, New York) is funding the dermatopathology portion of Derm In-Review, and the online application has already seen a face-lift. With the addition of more content, an updated mobile app, and possibly digital slides, this app will become a more useful tool for learning dermatopathology. Access to Derm In-Review is free with registration on the Web site.

Honorable Mention: Dermpath University

Dermpath University (http://www.dermpathdiagnostics.com/university/digitaldermpath) is a Web-based educational resource of Dermpath Diagnostics that houses a large collection of digital slides. These slides are categorized and can be viewed as unknown cases or with the diagnoses revealed. The images are of high quality and the software is intuitive; however, aside from the diagnosis, slides are not labeled with histologic features or comments about them. The best way to think of this collection is to imagine it is a digital version of the organized slide boxes many residency programs have for teaching purposes. Access to Dermpath University is free with registration on the Web site. Dermpath University also is home to weekly live teledermatology sessions; the schedule can be found on the Web site.

Online Courses: DermpathMD and MDlive

Although structured differently than the other apps described in this article, DermpathMD (http://www.dermpathmd.com) and MDlive (http://www.mdlive.net/dermpath_sch.htm) offer free online dermatopathology courses that are also valuable resources. Rather than discrete apps or digital slides, the courses available from these sources are presented in a lecture-based format to provide overviews on specific topics in dermatopathology. DermpathMD has lectures available as PDFs to download, while MDlive has narrated presentations. Both of these resources are good supplements to a dermatopathology textbook and can be used to obtain a basic foothold on the subject matter before more detailed study.

Conclusion

Learning dermatopathology is no longer done exclusively behind a microscope. The resources presented here bring the experience of learning and reviewing histology slides to your fingertips, sharpening your ability to hone in on the correct features to make an accurate diagnosis. Studying from these digital resources is convenient, comprehensive, and generally free of charge. I hope that you enjoy experimenting with these programs to find a combination that suits your educational needs.

1. Pantanowitz L, Valenstein PN, Evans AJ, et al. Review of the current state of whole slide imaging in pathology. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:36.

2. Bronfenbrener R. Learning from a leader: an interview with Dirk M. Elston, MD. Cutis. 2014;93:E7-E9.

As in the study of clinical dermatology, establishing a strong fund of knowledge regarding dermatopathology requires visual exposure to countless representative cases. In the not-so-distant past, textbooks relied on grayscale representations to illustrate these diagnoses, but residents today enjoy full-color images; however, textbooks lack the plasticity of digital media, which allow for more immersive interaction with the content. With technological advances in whole-slide imaging, teaching cases can be saved and shared, and rare diagnoses can be studied by individuals who are far removed from the original specimen.1 Even more exciting is that many of the applications (apps) that facilitate digital learning of dermatopathology are available free of charge. In this article, I will review some of the available apps, focusing on their usability, content, and utility as a learning resource for dermatologists at all stages of training. They are discussed in the order of their utility to students of dermatopathology. I have no financial ties to any of the products reviewed, and my recommendations reflect my opinions and observations after real-world use.

Winner: Clearpath

The Clearpath app (http://www.dermpathlab.com/clearpath/) is a fantastic representation of well-executed digital pathology software. Initially released for $50.00 in 2013, the app has since become free while maintaining a steady stream of updates and expanded content. The app is incredibly intuitive and easy to use, made possible by its modern user interface and versatile search function (Figure). For those just beginning to learn dermatopathology, the glossary contains well-written definitions as well as images, which have highlighting that can be toggled on and off to show an area of interest; for instance, if you cannot wrap your mind around the concept of a “grenz zone,” the app can highlight and focus your attention on the respective area in a related image. The app’s library contains more than 250 diagnoses; by clicking on a diagnosis, you are first shown several images displaying features of the pathology identified with highlighting. Then you can study a digital slide as if your tablet was a microscope stage, panning and zooming as you choose. When you are comfortable with the slides, the integrated quiz mode allows for board review with up to 25 answer choices per slide. Although Clearpath’s image-intensive program does require a wireless connection, it also offers the ability to download slides for offline review.

The app has few notable shortcomings related mostly to compatibility, as it is only available for download from the Apple App Store for iPad. Additionally, in comparison to other programs, there is a relative paucity of pathology images to look at, though new diagnoses frequently are added. Regardless, for those with iPads, it is the most refined introduction to a digital dermatopathology product, and a must-have download.

Runner-up: myDermPath

In my February 2014 column,2 I interviewed Dirk M. Elston, MD, and we briefly discussed the myDermPath app (http://mydermpath.com/), which had just recently been made available for free. The myDermPath app excels in the sheer volume of diagnoses it presents—more than 1000 in all—including more unusual pathologic entities. Physicians looking for images of barnyard pox or inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, for example, do not need to go any further. The pathologic images presented are accompanied by coherent descriptions of clinical features and usually are supplemented with clinical photographs. Furthermore, the app includes a video primer on normal histology narrated by Dr. Elston, a step-by-step algorithm for arriving at a diagnosis, and detailed descriptions of immunofluorescence studies and stains. These additional features make myDermPath a more comprehensive application and a more useful reference source. Its universal compatibility on a range of digital devices makes access to myDermPath convenient for users on any platform (ie, iOS, Android, Web).

The app’s most notable limitation is that, at the time of this writing, it feels somewhat less polished, especially compared to the Clearpath app. This antiquated feel also is evident in the app’s apparent instability on my smartphone, as it frequently stops responding while I am navigating through the menus or looking at histology and often makes it cumbersome to use. This stability issue is not evident on the Web-based version. The app also does not fully support the larger screen sizes of some of the newer smartphones, and therefore the display includes wasted dead space. These faults aside, the volume of material presented and the app’s comprehensive content still make myDermPath a useful addition to your digital dermatopathology repertoire.

Honorable Mention: Derm In-Review

Derm In-Review (http://dermatologyinreview.com/Merz) is sponsored by Merz Pharma and is well known as a broad-reaching resource that reviews the entire breadth of our field for those preparing for in-service or the boards examination. To learn dermatopathology, there are 2 ways to access the digital images: through the Web-based interface and via the mobile app (compatible with iOS and Android). The slides are not categorized but rather are presented in a random order to facilitate quiz taking. The slide images are only photographs of individual features and are not meant to be manipulated as true digital slides; however, the images are good representations of diagnoses, and short descriptions help with learning histologic features. Currently, Aurora Diagnostics (Woodbury, New York) is funding the dermatopathology portion of Derm In-Review, and the online application has already seen a face-lift. With the addition of more content, an updated mobile app, and possibly digital slides, this app will become a more useful tool for learning dermatopathology. Access to Derm In-Review is free with registration on the Web site.

Honorable Mention: Dermpath University

Dermpath University (http://www.dermpathdiagnostics.com/university/digitaldermpath) is a Web-based educational resource of Dermpath Diagnostics that houses a large collection of digital slides. These slides are categorized and can be viewed as unknown cases or with the diagnoses revealed. The images are of high quality and the software is intuitive; however, aside from the diagnosis, slides are not labeled with histologic features or comments about them. The best way to think of this collection is to imagine it is a digital version of the organized slide boxes many residency programs have for teaching purposes. Access to Dermpath University is free with registration on the Web site. Dermpath University also is home to weekly live teledermatology sessions; the schedule can be found on the Web site.

Online Courses: DermpathMD and MDlive

Although structured differently than the other apps described in this article, DermpathMD (http://www.dermpathmd.com) and MDlive (http://www.mdlive.net/dermpath_sch.htm) offer free online dermatopathology courses that are also valuable resources. Rather than discrete apps or digital slides, the courses available from these sources are presented in a lecture-based format to provide overviews on specific topics in dermatopathology. DermpathMD has lectures available as PDFs to download, while MDlive has narrated presentations. Both of these resources are good supplements to a dermatopathology textbook and can be used to obtain a basic foothold on the subject matter before more detailed study.

Conclusion

Learning dermatopathology is no longer done exclusively behind a microscope. The resources presented here bring the experience of learning and reviewing histology slides to your fingertips, sharpening your ability to hone in on the correct features to make an accurate diagnosis. Studying from these digital resources is convenient, comprehensive, and generally free of charge. I hope that you enjoy experimenting with these programs to find a combination that suits your educational needs.

As in the study of clinical dermatology, establishing a strong fund of knowledge regarding dermatopathology requires visual exposure to countless representative cases. In the not-so-distant past, textbooks relied on grayscale representations to illustrate these diagnoses, but residents today enjoy full-color images; however, textbooks lack the plasticity of digital media, which allow for more immersive interaction with the content. With technological advances in whole-slide imaging, teaching cases can be saved and shared, and rare diagnoses can be studied by individuals who are far removed from the original specimen.1 Even more exciting is that many of the applications (apps) that facilitate digital learning of dermatopathology are available free of charge. In this article, I will review some of the available apps, focusing on their usability, content, and utility as a learning resource for dermatologists at all stages of training. They are discussed in the order of their utility to students of dermatopathology. I have no financial ties to any of the products reviewed, and my recommendations reflect my opinions and observations after real-world use.

Winner: Clearpath

The Clearpath app (http://www.dermpathlab.com/clearpath/) is a fantastic representation of well-executed digital pathology software. Initially released for $50.00 in 2013, the app has since become free while maintaining a steady stream of updates and expanded content. The app is incredibly intuitive and easy to use, made possible by its modern user interface and versatile search function (Figure). For those just beginning to learn dermatopathology, the glossary contains well-written definitions as well as images, which have highlighting that can be toggled on and off to show an area of interest; for instance, if you cannot wrap your mind around the concept of a “grenz zone,” the app can highlight and focus your attention on the respective area in a related image. The app’s library contains more than 250 diagnoses; by clicking on a diagnosis, you are first shown several images displaying features of the pathology identified with highlighting. Then you can study a digital slide as if your tablet was a microscope stage, panning and zooming as you choose. When you are comfortable with the slides, the integrated quiz mode allows for board review with up to 25 answer choices per slide. Although Clearpath’s image-intensive program does require a wireless connection, it also offers the ability to download slides for offline review.

The app has few notable shortcomings related mostly to compatibility, as it is only available for download from the Apple App Store for iPad. Additionally, in comparison to other programs, there is a relative paucity of pathology images to look at, though new diagnoses frequently are added. Regardless, for those with iPads, it is the most refined introduction to a digital dermatopathology product, and a must-have download.

Runner-up: myDermPath

In my February 2014 column,2 I interviewed Dirk M. Elston, MD, and we briefly discussed the myDermPath app (http://mydermpath.com/), which had just recently been made available for free. The myDermPath app excels in the sheer volume of diagnoses it presents—more than 1000 in all—including more unusual pathologic entities. Physicians looking for images of barnyard pox or inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, for example, do not need to go any further. The pathologic images presented are accompanied by coherent descriptions of clinical features and usually are supplemented with clinical photographs. Furthermore, the app includes a video primer on normal histology narrated by Dr. Elston, a step-by-step algorithm for arriving at a diagnosis, and detailed descriptions of immunofluorescence studies and stains. These additional features make myDermPath a more comprehensive application and a more useful reference source. Its universal compatibility on a range of digital devices makes access to myDermPath convenient for users on any platform (ie, iOS, Android, Web).

The app’s most notable limitation is that, at the time of this writing, it feels somewhat less polished, especially compared to the Clearpath app. This antiquated feel also is evident in the app’s apparent instability on my smartphone, as it frequently stops responding while I am navigating through the menus or looking at histology and often makes it cumbersome to use. This stability issue is not evident on the Web-based version. The app also does not fully support the larger screen sizes of some of the newer smartphones, and therefore the display includes wasted dead space. These faults aside, the volume of material presented and the app’s comprehensive content still make myDermPath a useful addition to your digital dermatopathology repertoire.

Honorable Mention: Derm In-Review

Derm In-Review (http://dermatologyinreview.com/Merz) is sponsored by Merz Pharma and is well known as a broad-reaching resource that reviews the entire breadth of our field for those preparing for in-service or the boards examination. To learn dermatopathology, there are 2 ways to access the digital images: through the Web-based interface and via the mobile app (compatible with iOS and Android). The slides are not categorized but rather are presented in a random order to facilitate quiz taking. The slide images are only photographs of individual features and are not meant to be manipulated as true digital slides; however, the images are good representations of diagnoses, and short descriptions help with learning histologic features. Currently, Aurora Diagnostics (Woodbury, New York) is funding the dermatopathology portion of Derm In-Review, and the online application has already seen a face-lift. With the addition of more content, an updated mobile app, and possibly digital slides, this app will become a more useful tool for learning dermatopathology. Access to Derm In-Review is free with registration on the Web site.

Honorable Mention: Dermpath University

Dermpath University (http://www.dermpathdiagnostics.com/university/digitaldermpath) is a Web-based educational resource of Dermpath Diagnostics that houses a large collection of digital slides. These slides are categorized and can be viewed as unknown cases or with the diagnoses revealed. The images are of high quality and the software is intuitive; however, aside from the diagnosis, slides are not labeled with histologic features or comments about them. The best way to think of this collection is to imagine it is a digital version of the organized slide boxes many residency programs have for teaching purposes. Access to Dermpath University is free with registration on the Web site. Dermpath University also is home to weekly live teledermatology sessions; the schedule can be found on the Web site.

Online Courses: DermpathMD and MDlive

Although structured differently than the other apps described in this article, DermpathMD (http://www.dermpathmd.com) and MDlive (http://www.mdlive.net/dermpath_sch.htm) offer free online dermatopathology courses that are also valuable resources. Rather than discrete apps or digital slides, the courses available from these sources are presented in a lecture-based format to provide overviews on specific topics in dermatopathology. DermpathMD has lectures available as PDFs to download, while MDlive has narrated presentations. Both of these resources are good supplements to a dermatopathology textbook and can be used to obtain a basic foothold on the subject matter before more detailed study.

Conclusion

Learning dermatopathology is no longer done exclusively behind a microscope. The resources presented here bring the experience of learning and reviewing histology slides to your fingertips, sharpening your ability to hone in on the correct features to make an accurate diagnosis. Studying from these digital resources is convenient, comprehensive, and generally free of charge. I hope that you enjoy experimenting with these programs to find a combination that suits your educational needs.

1. Pantanowitz L, Valenstein PN, Evans AJ, et al. Review of the current state of whole slide imaging in pathology. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:36.

2. Bronfenbrener R. Learning from a leader: an interview with Dirk M. Elston, MD. Cutis. 2014;93:E7-E9.

1. Pantanowitz L, Valenstein PN, Evans AJ, et al. Review of the current state of whole slide imaging in pathology. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:36.

2. Bronfenbrener R. Learning from a leader: an interview with Dirk M. Elston, MD. Cutis. 2014;93:E7-E9.

Product News: 04 2014

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Errata

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis to 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate

Cyanoacrylates are widely used in adhesive products, with applications ranging from household products to nail and beauty salons and even dentistry. A topical skin adhesive containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate was approved in 1998 for topical application for closure of skin edges of wounds from surgical incisions.1 Usually cyanoacrylates are not strong sensitizers, and despite their extensive use, there have been relatively few reports of associated allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2-5 We report 4 cases of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate used in postsurgical wound closures as confirmed by patch tests.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 33-year-old woman presented with an intensely pruritic peri-incisional rash on the lower back and right buttock of 1 week’s duration. The eruption started roughly 1 week following surgical implantation of a spinal cord stimulator for treatment of chronic back pain. Both incisions made during the implantation were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. The patient denied any prior exposure to topical skin adhesives or any history of contact dermatitis to nickel or other materials. The patient did not dress the wounds and did not apply topical agents to the area.