User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Topical Therapy for Acne in Women: Is There a Role for Clindamycin Phosphate–Benzoyl Peroxide Gel?

The management of acne vulgaris (AV) in women has been the subject of considerable attention over the last few years. It has become increasingly recognized that a greater number of patient encounters in dermatology offices involve women with AV who are beyond their adolescent years. Overall, it is estimated that up to approximately 22% of women in the United States are affected by AV, with approximately half of women in their 20s and one-third of women in their 30s reporting some degree of AV.1-4 Among women, the disease shows no predilection for certain skin types or ethnicities, can start during the preteenaged or adolescent years, can persist or recur in adulthood (persistent acne, 75%), or can start in adulthood (late-onset acne, 25%) in females with minimal or no history of AV occurring earlier in life.3,5-7 In the subpopulation of adult women, AV occurs at a time when many expect to be far beyond this “teenage affliction.” Women who are affected commonly express feeling embarrassed and frustrated.5-8

Most of the emphasis in the literature and in presentations at dermatology meetings regarding the management of AV in adult women has focused on excluding underlying disorders that cause excess androgens (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, tumors, exogenous sources) as well as the use of systemic therapies such as oral contraceptives (OCs) and spironolactone.5-7,9,10 Little attention has been given to the selection of topical therapies in this patient population, especially with regard to evidence from clinical studies. To date, results from published study analyses using topical agents specifically for adult females with facial AV have only included adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.11-13 Both agents have been evaluated in subset analysis comparisons of outcomes in women aged 18 years and older versus adolescents aged 12 to 17 years based on data from 12-week phase 3 pivotal trials.14-16

Are there clinically relevant differences between AV in adult versus adolescent females?

Although much has been written about AV in women, epidemiology, demographics, assessment of clinical presentation, and correlation of clinical presentation with excess androgens have not been emphasized,1-3,5-10,17 likely due to marketing campaigns that emphasize AV as a disorder that predominantly affects teenagers as well as the focus on optimal use of oral spironolactone and/or OCs in the management of AV in the adult female population. Attention to spironolactone use is important because it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AV. Spironolactone carries certain black-box warnings that may not be clinically relevant in all patients but still require attention. It also is associated with risks if taken during pregnancy, and it is a potassium-sparing diuretic with potential for hyperkalemia, especially in patients with reduced renal function or those who are taking potassium supplements or certain other medications.6,9,11,17 Use of OCs to treat AV also is not without potential risks, with specific warnings and relative contraindications reported, especially in relation to increased risks for cardiac complications, stroke, and thromboembolism.6,9,11,12 Because adult females are in a different stage of life than teenagers, there are defined psychosocial and medical considerations in managing AV in these patients compared with adolescents.5-8,17 Importantly for both clinicians and patients, addressing these differences and considerations can have a major impact on whether or not women with AV experience successful treatment outcomes.1-3,5,6,8,10,13 Skin color and ethnicity also can affect the psychosocial and physical factors that influence the overall management of adult female patients with AV, including selection of therapies and handling long-term visible sequelae that occur in some AV patients, such as dyschromia (eg, persistent or postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation) and acne scarring.5-8,13,17-20

Psychosocial Considerations

With regard to psychosocial, emotional, and attitudinal considerations in women with AV, common findings include concern or frustration regarding the presence of AV beyond adolescence; anxiety; symptoms of depression; decreased self-confidence; increased self-consciousness, especially during public interactions or intimate situations; and interference with steady concentration at work or school.5,6,8,13 Long-term complications of AV, such as dyschromia and acne scarring, are more likely to be encountered in adult patients, especially if they had AV as a teenager, with women reporting that they remain conscious of these adverse sequelae.8 It is estimated that approximately three-fourths of women with AV also had AV as teenagers; therefore, most of them have already used many over-the-counter and prescription therapies and are likely to want treatments that are newer, well-tolerated, safe, and known to be effective in adult women.8,16,17 Convenience and simplicity are vital components of treatment selection and regimen design, as many women with AV frequently face time constraints in their daily routines due to family, social, employment, and home-related demands and responsibilities.6-8,17

Medical Considerations

It is apparent from reports in the literature as well as from clinical experience that some women with AV present with a U-shaped pattern of involvement on the face,5-7,10,13,17 which refers to the presence of predominantly inflammatory papules (many of them deep) and some nodules on the lower face, jawline, and anterolateral neck region, with comedones often sparse or absent.5-7 It often is perceived and may be true that women who present with this pattern of distribution are more androgen sensitive despite having normal serum androgen levels or in some cases exhibit detectable excess androgens (eg, in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome) and may be more likely to respond to hormonal therapies (eg, spironolactone, OCs) than those with mixed facial AV (ie, multiple comedonal and inflammatory acne lesions, not limited to a U-shaped pattern, similar to adolescent AV), but data are limited to support differentiation between the U-shaped pattern group and the conventional mixed facial AV group.5-7,17 Adult and adolescent females in both groups sometimes report perimenstrual flares and frequent persistent papular AV that tends to concentrate on the perioral and chin area.

It is also important to consider that the current literature suggests approximately three-fourths of women with AV report that they also had AV as a teenager, with many indicating the same clinical pattern of AV and approximately one-third reporting AV that is more severe in adulthood than adolescence.5-8,17 The available literature on topical and oral therapies used to treat AV in both adolescent and adult females predominantly focuses on inclusion of both inflammatory and noninflammatory (comedonal) facial AV lesions, does not specifically address or include the U-shaped pattern of AV in adult women for inclusion in studies that evaluate efficacy in this subgroup, and does not include AV involving the neck region and below the jawline margin as part of any study protocols and/or discussions about therapy.5-7,9-12,17,21-26 Involvement of the neck and lower jawline is common in women presenting with the U-shaped pattern of AV, and available studies only evaluate AV involving the face and do not include AV lesions present below the jawline margin. As a result, there is a considerable need for well-designed studies with laboratory assessments to include or exclude underlying detectable excess androgens and to assess the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of specific therapeutic agents both alone and in combination in adult women who present with a U-shaped pattern of AV.17

Other medical considerations that can influence treatment selection and are more likely to be present in adult versus adolescent females include underlying chronic medical disorders; concomitant medications that may interact with other oral agents; potential for pregnancy; age, particularly when prescribing OCs; and the potential desire to stop taking OCs if already used over a prolonged period.6,7

Age-Related Differentiation of Female Subgroups With AV

The age-based dividing line that defines AV in adults versus adolescent females has been described in the literature; however, the basis for published definitions of female subgroups with AV is not well-supported by strong scientific evidence.1-3,5-7,17 The conventional dividing line that was originally selected to define adult females with AV was 25 years of age or older; persistent acne is present both during adolescence and at or after 25 years of age, while late-onset acne is described as AV that first presents at 25 years of age or older.3,5-7

More recently, a range of 18 years or older has been used to classify adult female AV and a range of 12 to 17 years for adolescent female AV in subset analyses that evaluated treatment outcomes in both patient populations from phase 3 pivotal trials completed with adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.14-16 These subanalyses included participants with facial AV that was predominantly moderate in severity, mandated specific lesion count ranges for both comedonal and inflammatory lesions, and included only facial AV that was above the mandibular (jawline) margin.15,16,21,26 Therefore, patients with AV presenting in a U-shaped pattern with involvement below the jawline and on the neck were not included in these study analyses, as these patients were excluded from the phase 3 trials on which the analyses were based. The outcomes of these analyses apply to treatment in women who present with both inflammatory and noninflammatory facial AV lesions, which supports the observation that AV in this patient population is not always predominantly inflammatory and does not always present in a U-shaped distribution.14-16 In fact, a U-shaped pattern of distribution appears to be less common in women with AV than a mixed inflammatory and comedonal distribution that involves the face more diffusely, though more data are needed from well-designed and large-scale epidemiologic and demographic studies.5,14,17

Are there data available on the use of benzoyl peroxide with or without a topical antibiotic in women with AV?

There is a conspicuous absence of prospective clinical trials and retrospective analyses evaluating the specific use of individual AV therapies in adult females, with a particular lack of studies with topical agents (eg, benzoyl peroxide [BP]).14 Subset analyses have been completed for adapalene gel 0.3% and dapsone gel 5%.15,16 Additionally, an age-based subset analysis in females with facial AV also has been completed with clindamycin phosphate (CP) 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel once daily, with data presented but not yet fully published.14

Two identical phase 3, double-blind, randomized, 12-week, 4-arm trials compared treatment outcomes in groups treated with an aqueous-based combination gel formulation containing BP 2.5% and CP 1.2% (n=797), active monad gels (BP [n=809] or CP [n=812]), or vehicle gel (n=395), all applied once daily in patients with facial AV.22 Participants were 12 years or older (mean age range, 19.1–19.6 years; age range, 12.1–70.2 years), were of either gender (approximately 50% split in each study arm), and presented with moderate (approximately 80% of participants) or severe AV (approximately 20% of participants) at baseline. The entry criteria for lesion types and number of lesions were 17 to 40 inflammatory lesions (ie, papules, pustules, <2 nodules)(range of mean number of lesions, 25.8–26.4) and 20 to 100 noninflammatory lesions (ie, closed comedones, open comedones)(range of mean number of lesions, 44.0–47.4). Participant demographics included white (73.9%–77.5%), black/African American (16.1%–20.4%), and Asian (2.1%–3.3%), with the remaining participants distributed among a variety of other ethnic groups such as Native Hawaiian/Native Pacific Islander and Native American Indian/Native Alaskan (collectively <5% in each study arm). Therefore, approximately 1 of every 4 patients had skin of color, which provided good diversity of patients considering the large study size (N=2813). Data analysis included dichotomization of participants by severity rating (moderate or severe based on evaluator global severity score) and skin phototype (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III or IV–VI).22

The pooled results from both studies completed at 68 investigative sites demonstrated that CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was superior in efficacy to each individual monad and to the vehicle in inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion reductions as early as week 4 (P<.001) and at week 12, which was the study end point (P<.001), with superiority also demonstrated in achieving treatment success (defined as a >2 grade improvement according to the evaluator global severity score) compared to the 3 other study arms (P<.001).22 Subject assessments also were consistent with outcomes noted by the investigators. Cutaneous tolerability was favorable and comparable in all 4 study arms with less than 1% of participants discontinuing treatment due to adverse events.22

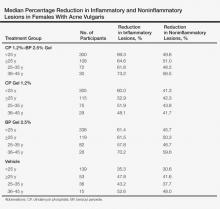

A subset analysis of the data from the phase 3 pivotal trials with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was completed to compare reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions in female participants who were younger than 25 years and 25 years of age or older in all 4 study arms. This information has been presented14,17 but has not been previously published. Based on the overall results reported in the phase 3 studies, there were no differentiations in skin tolerability or safety based on participant age, gender, or skin type.22 The subanalysis included a total of 1080 females who were younger than 25 years and 395 females who were 25 years of age or older. The lesion reduction outcomes of this subanalysis are presented in the Table. Statistical analyses of the results among these age groups in the 4 study arms were not completed because the objective was to determine if there were any major or obvious differences in reduction of AV lesions based on the conventional dividing line of 25 years of age in adult women as compared to adolescent females treated with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel. In addition, the large difference in numbers of female participants between the 2 age groups (>25 years of age, n=395; <25 years of age, n=1080) at least partially confounds both statistical and observational analysis. Among the women who were 25 years of age or older who were included in the subanalysis, 67.0% and 25.8% were between the ages of 25 to 35 years and 36 to 45 years, respectively. Based on the outcomes reported in the phase 3 trials and in this subgroup analysis, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel applied once daily over a 12-week period appeared overall to be comparably effective in females regardless of age and with no apparent adverse events regarding differences in skin tolerability or safety.14,22 One observation that was noted was the possible trend of greater reduction in both lesion types in women older than 35 years versus younger females with the use of the combination gel or BP alone; however, the number of female participants who were older than 35 years of age was substantially less (n=102) than those who were 35 years of age or younger (n=1345), thus precluding support for any definitive conclusions about this possible trend.22

How can CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel be incorporated into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV?

The incorporation of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV is similar to the general use of BP-containing formulations in the overall management of AV.9,14,27,28 Because women with AV commonly present with facial inflammatory lesions and many also with facial comedones, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel is best used once daily in the morning in combination with a topical retinoid in the evening,9,27 which can be achieved with use of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel in the morning and a topical retinoid (ie, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene) in the evening or CP 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% gel in the evening. It is important to note that cutaneous irritation may be more likely if neck lesions are present; the potential for bleaching of colored fabric by BP also is a practical concern.28 In addition, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel may also be used in combination with topical dapsone, but both products should be applied separately at different times of the day to avoid temporary orange discoloration of the skin, which appears to be an uncommon side effect but remains a possibility based on the product information for dapsone gel 5% with regard to its concomitant use with BP.29,30

1. Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, et al. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21:223-230.

2. Zeichner J. Evaluating and treating the adult female patient with acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1416-1427.

3. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

4. Collier CN, Harper J, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-59.

5. Dreno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

6. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

7. Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

8. Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

9. Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):1-37.

10. Thiboutot DM. Endocrinological evaluation and hormonal therapy for women with difficult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(suppl 3):57-61.

11. Sawaya ME, Samani N. Antiandrogens and androgen receptors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders-Elsevier; 2012:361-374.

12. Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

13. Preneau S, Dreno B. Female acne: a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:277-282.

14. Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. What’s new in the medicine cabinet?: a panoramic review of clinically relevant information for the busy dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-30.

15. Berson D, Alexis A. Adapalene 0.3% for the treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:32-35.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, Gallagher C. Facing up to adult women with acne vulgaris: an analysis of pivotal trial data on dapsone 5% gel in the adult female population. Poster presented at: Fall Clinical Dermatology; October 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

17. Del Rosso JQ. Management of acne with oral spironolactone. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Summer Meeting; August 2013; Boston, MA.

18. Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

19. Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

20. Perkins AC, Cheng CE, Hillebrand GG, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1054-1060.

21. Draelos ZD, Carter E, Maloney JM, et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris [published online ahead of print January 17, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:439.e1-439.e10.

22. Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

23. Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining

1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

24. Fleischer AB Jr, Dinehart S, Stough D, et al. Safety and efficacy of a new extended-release formulation of minocycline. Cutis. 2006;78(suppl 4):21-31.

25. Gollnick HP, Draelos Z, Glenn MJ, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a unique fixed-dose combination topical gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a transatlantic, randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 1670 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1180-1189.

26. Thiboutot D, Arsonnaud S, Soto P. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(suppl 6):3-10.

27. Zeichner JA. Optimizing topical combination therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:313-317.

28. Tanghetti EA, Popp KF. A current review of topical benzoyl peroxide: new perspectives on formulation and utilization. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:17-24.

29. Fleischer AB, Shalita A, Eichenfield LF. Dapsone gel 5% in combination with adapalene gel 0.1%, benzoyl peroxide gel 4% or moisturizer for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:33-40.

30. Aczone (dapsone gel 5%) [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

The management of acne vulgaris (AV) in women has been the subject of considerable attention over the last few years. It has become increasingly recognized that a greater number of patient encounters in dermatology offices involve women with AV who are beyond their adolescent years. Overall, it is estimated that up to approximately 22% of women in the United States are affected by AV, with approximately half of women in their 20s and one-third of women in their 30s reporting some degree of AV.1-4 Among women, the disease shows no predilection for certain skin types or ethnicities, can start during the preteenaged or adolescent years, can persist or recur in adulthood (persistent acne, 75%), or can start in adulthood (late-onset acne, 25%) in females with minimal or no history of AV occurring earlier in life.3,5-7 In the subpopulation of adult women, AV occurs at a time when many expect to be far beyond this “teenage affliction.” Women who are affected commonly express feeling embarrassed and frustrated.5-8

Most of the emphasis in the literature and in presentations at dermatology meetings regarding the management of AV in adult women has focused on excluding underlying disorders that cause excess androgens (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, tumors, exogenous sources) as well as the use of systemic therapies such as oral contraceptives (OCs) and spironolactone.5-7,9,10 Little attention has been given to the selection of topical therapies in this patient population, especially with regard to evidence from clinical studies. To date, results from published study analyses using topical agents specifically for adult females with facial AV have only included adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.11-13 Both agents have been evaluated in subset analysis comparisons of outcomes in women aged 18 years and older versus adolescents aged 12 to 17 years based on data from 12-week phase 3 pivotal trials.14-16

Are there clinically relevant differences between AV in adult versus adolescent females?

Although much has been written about AV in women, epidemiology, demographics, assessment of clinical presentation, and correlation of clinical presentation with excess androgens have not been emphasized,1-3,5-10,17 likely due to marketing campaigns that emphasize AV as a disorder that predominantly affects teenagers as well as the focus on optimal use of oral spironolactone and/or OCs in the management of AV in the adult female population. Attention to spironolactone use is important because it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AV. Spironolactone carries certain black-box warnings that may not be clinically relevant in all patients but still require attention. It also is associated with risks if taken during pregnancy, and it is a potassium-sparing diuretic with potential for hyperkalemia, especially in patients with reduced renal function or those who are taking potassium supplements or certain other medications.6,9,11,17 Use of OCs to treat AV also is not without potential risks, with specific warnings and relative contraindications reported, especially in relation to increased risks for cardiac complications, stroke, and thromboembolism.6,9,11,12 Because adult females are in a different stage of life than teenagers, there are defined psychosocial and medical considerations in managing AV in these patients compared with adolescents.5-8,17 Importantly for both clinicians and patients, addressing these differences and considerations can have a major impact on whether or not women with AV experience successful treatment outcomes.1-3,5,6,8,10,13 Skin color and ethnicity also can affect the psychosocial and physical factors that influence the overall management of adult female patients with AV, including selection of therapies and handling long-term visible sequelae that occur in some AV patients, such as dyschromia (eg, persistent or postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation) and acne scarring.5-8,13,17-20

Psychosocial Considerations

With regard to psychosocial, emotional, and attitudinal considerations in women with AV, common findings include concern or frustration regarding the presence of AV beyond adolescence; anxiety; symptoms of depression; decreased self-confidence; increased self-consciousness, especially during public interactions or intimate situations; and interference with steady concentration at work or school.5,6,8,13 Long-term complications of AV, such as dyschromia and acne scarring, are more likely to be encountered in adult patients, especially if they had AV as a teenager, with women reporting that they remain conscious of these adverse sequelae.8 It is estimated that approximately three-fourths of women with AV also had AV as teenagers; therefore, most of them have already used many over-the-counter and prescription therapies and are likely to want treatments that are newer, well-tolerated, safe, and known to be effective in adult women.8,16,17 Convenience and simplicity are vital components of treatment selection and regimen design, as many women with AV frequently face time constraints in their daily routines due to family, social, employment, and home-related demands and responsibilities.6-8,17

Medical Considerations

It is apparent from reports in the literature as well as from clinical experience that some women with AV present with a U-shaped pattern of involvement on the face,5-7,10,13,17 which refers to the presence of predominantly inflammatory papules (many of them deep) and some nodules on the lower face, jawline, and anterolateral neck region, with comedones often sparse or absent.5-7 It often is perceived and may be true that women who present with this pattern of distribution are more androgen sensitive despite having normal serum androgen levels or in some cases exhibit detectable excess androgens (eg, in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome) and may be more likely to respond to hormonal therapies (eg, spironolactone, OCs) than those with mixed facial AV (ie, multiple comedonal and inflammatory acne lesions, not limited to a U-shaped pattern, similar to adolescent AV), but data are limited to support differentiation between the U-shaped pattern group and the conventional mixed facial AV group.5-7,17 Adult and adolescent females in both groups sometimes report perimenstrual flares and frequent persistent papular AV that tends to concentrate on the perioral and chin area.

It is also important to consider that the current literature suggests approximately three-fourths of women with AV report that they also had AV as a teenager, with many indicating the same clinical pattern of AV and approximately one-third reporting AV that is more severe in adulthood than adolescence.5-8,17 The available literature on topical and oral therapies used to treat AV in both adolescent and adult females predominantly focuses on inclusion of both inflammatory and noninflammatory (comedonal) facial AV lesions, does not specifically address or include the U-shaped pattern of AV in adult women for inclusion in studies that evaluate efficacy in this subgroup, and does not include AV involving the neck region and below the jawline margin as part of any study protocols and/or discussions about therapy.5-7,9-12,17,21-26 Involvement of the neck and lower jawline is common in women presenting with the U-shaped pattern of AV, and available studies only evaluate AV involving the face and do not include AV lesions present below the jawline margin. As a result, there is a considerable need for well-designed studies with laboratory assessments to include or exclude underlying detectable excess androgens and to assess the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of specific therapeutic agents both alone and in combination in adult women who present with a U-shaped pattern of AV.17

Other medical considerations that can influence treatment selection and are more likely to be present in adult versus adolescent females include underlying chronic medical disorders; concomitant medications that may interact with other oral agents; potential for pregnancy; age, particularly when prescribing OCs; and the potential desire to stop taking OCs if already used over a prolonged period.6,7

Age-Related Differentiation of Female Subgroups With AV

The age-based dividing line that defines AV in adults versus adolescent females has been described in the literature; however, the basis for published definitions of female subgroups with AV is not well-supported by strong scientific evidence.1-3,5-7,17 The conventional dividing line that was originally selected to define adult females with AV was 25 years of age or older; persistent acne is present both during adolescence and at or after 25 years of age, while late-onset acne is described as AV that first presents at 25 years of age or older.3,5-7

More recently, a range of 18 years or older has been used to classify adult female AV and a range of 12 to 17 years for adolescent female AV in subset analyses that evaluated treatment outcomes in both patient populations from phase 3 pivotal trials completed with adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.14-16 These subanalyses included participants with facial AV that was predominantly moderate in severity, mandated specific lesion count ranges for both comedonal and inflammatory lesions, and included only facial AV that was above the mandibular (jawline) margin.15,16,21,26 Therefore, patients with AV presenting in a U-shaped pattern with involvement below the jawline and on the neck were not included in these study analyses, as these patients were excluded from the phase 3 trials on which the analyses were based. The outcomes of these analyses apply to treatment in women who present with both inflammatory and noninflammatory facial AV lesions, which supports the observation that AV in this patient population is not always predominantly inflammatory and does not always present in a U-shaped distribution.14-16 In fact, a U-shaped pattern of distribution appears to be less common in women with AV than a mixed inflammatory and comedonal distribution that involves the face more diffusely, though more data are needed from well-designed and large-scale epidemiologic and demographic studies.5,14,17

Are there data available on the use of benzoyl peroxide with or without a topical antibiotic in women with AV?

There is a conspicuous absence of prospective clinical trials and retrospective analyses evaluating the specific use of individual AV therapies in adult females, with a particular lack of studies with topical agents (eg, benzoyl peroxide [BP]).14 Subset analyses have been completed for adapalene gel 0.3% and dapsone gel 5%.15,16 Additionally, an age-based subset analysis in females with facial AV also has been completed with clindamycin phosphate (CP) 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel once daily, with data presented but not yet fully published.14

Two identical phase 3, double-blind, randomized, 12-week, 4-arm trials compared treatment outcomes in groups treated with an aqueous-based combination gel formulation containing BP 2.5% and CP 1.2% (n=797), active monad gels (BP [n=809] or CP [n=812]), or vehicle gel (n=395), all applied once daily in patients with facial AV.22 Participants were 12 years or older (mean age range, 19.1–19.6 years; age range, 12.1–70.2 years), were of either gender (approximately 50% split in each study arm), and presented with moderate (approximately 80% of participants) or severe AV (approximately 20% of participants) at baseline. The entry criteria for lesion types and number of lesions were 17 to 40 inflammatory lesions (ie, papules, pustules, <2 nodules)(range of mean number of lesions, 25.8–26.4) and 20 to 100 noninflammatory lesions (ie, closed comedones, open comedones)(range of mean number of lesions, 44.0–47.4). Participant demographics included white (73.9%–77.5%), black/African American (16.1%–20.4%), and Asian (2.1%–3.3%), with the remaining participants distributed among a variety of other ethnic groups such as Native Hawaiian/Native Pacific Islander and Native American Indian/Native Alaskan (collectively <5% in each study arm). Therefore, approximately 1 of every 4 patients had skin of color, which provided good diversity of patients considering the large study size (N=2813). Data analysis included dichotomization of participants by severity rating (moderate or severe based on evaluator global severity score) and skin phototype (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III or IV–VI).22

The pooled results from both studies completed at 68 investigative sites demonstrated that CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was superior in efficacy to each individual monad and to the vehicle in inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion reductions as early as week 4 (P<.001) and at week 12, which was the study end point (P<.001), with superiority also demonstrated in achieving treatment success (defined as a >2 grade improvement according to the evaluator global severity score) compared to the 3 other study arms (P<.001).22 Subject assessments also were consistent with outcomes noted by the investigators. Cutaneous tolerability was favorable and comparable in all 4 study arms with less than 1% of participants discontinuing treatment due to adverse events.22

A subset analysis of the data from the phase 3 pivotal trials with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was completed to compare reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions in female participants who were younger than 25 years and 25 years of age or older in all 4 study arms. This information has been presented14,17 but has not been previously published. Based on the overall results reported in the phase 3 studies, there were no differentiations in skin tolerability or safety based on participant age, gender, or skin type.22 The subanalysis included a total of 1080 females who were younger than 25 years and 395 females who were 25 years of age or older. The lesion reduction outcomes of this subanalysis are presented in the Table. Statistical analyses of the results among these age groups in the 4 study arms were not completed because the objective was to determine if there were any major or obvious differences in reduction of AV lesions based on the conventional dividing line of 25 years of age in adult women as compared to adolescent females treated with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel. In addition, the large difference in numbers of female participants between the 2 age groups (>25 years of age, n=395; <25 years of age, n=1080) at least partially confounds both statistical and observational analysis. Among the women who were 25 years of age or older who were included in the subanalysis, 67.0% and 25.8% were between the ages of 25 to 35 years and 36 to 45 years, respectively. Based on the outcomes reported in the phase 3 trials and in this subgroup analysis, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel applied once daily over a 12-week period appeared overall to be comparably effective in females regardless of age and with no apparent adverse events regarding differences in skin tolerability or safety.14,22 One observation that was noted was the possible trend of greater reduction in both lesion types in women older than 35 years versus younger females with the use of the combination gel or BP alone; however, the number of female participants who were older than 35 years of age was substantially less (n=102) than those who were 35 years of age or younger (n=1345), thus precluding support for any definitive conclusions about this possible trend.22

How can CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel be incorporated into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV?

The incorporation of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV is similar to the general use of BP-containing formulations in the overall management of AV.9,14,27,28 Because women with AV commonly present with facial inflammatory lesions and many also with facial comedones, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel is best used once daily in the morning in combination with a topical retinoid in the evening,9,27 which can be achieved with use of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel in the morning and a topical retinoid (ie, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene) in the evening or CP 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% gel in the evening. It is important to note that cutaneous irritation may be more likely if neck lesions are present; the potential for bleaching of colored fabric by BP also is a practical concern.28 In addition, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel may also be used in combination with topical dapsone, but both products should be applied separately at different times of the day to avoid temporary orange discoloration of the skin, which appears to be an uncommon side effect but remains a possibility based on the product information for dapsone gel 5% with regard to its concomitant use with BP.29,30

The management of acne vulgaris (AV) in women has been the subject of considerable attention over the last few years. It has become increasingly recognized that a greater number of patient encounters in dermatology offices involve women with AV who are beyond their adolescent years. Overall, it is estimated that up to approximately 22% of women in the United States are affected by AV, with approximately half of women in their 20s and one-third of women in their 30s reporting some degree of AV.1-4 Among women, the disease shows no predilection for certain skin types or ethnicities, can start during the preteenaged or adolescent years, can persist or recur in adulthood (persistent acne, 75%), or can start in adulthood (late-onset acne, 25%) in females with minimal or no history of AV occurring earlier in life.3,5-7 In the subpopulation of adult women, AV occurs at a time when many expect to be far beyond this “teenage affliction.” Women who are affected commonly express feeling embarrassed and frustrated.5-8

Most of the emphasis in the literature and in presentations at dermatology meetings regarding the management of AV in adult women has focused on excluding underlying disorders that cause excess androgens (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, tumors, exogenous sources) as well as the use of systemic therapies such as oral contraceptives (OCs) and spironolactone.5-7,9,10 Little attention has been given to the selection of topical therapies in this patient population, especially with regard to evidence from clinical studies. To date, results from published study analyses using topical agents specifically for adult females with facial AV have only included adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.11-13 Both agents have been evaluated in subset analysis comparisons of outcomes in women aged 18 years and older versus adolescents aged 12 to 17 years based on data from 12-week phase 3 pivotal trials.14-16

Are there clinically relevant differences between AV in adult versus adolescent females?

Although much has been written about AV in women, epidemiology, demographics, assessment of clinical presentation, and correlation of clinical presentation with excess androgens have not been emphasized,1-3,5-10,17 likely due to marketing campaigns that emphasize AV as a disorder that predominantly affects teenagers as well as the focus on optimal use of oral spironolactone and/or OCs in the management of AV in the adult female population. Attention to spironolactone use is important because it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AV. Spironolactone carries certain black-box warnings that may not be clinically relevant in all patients but still require attention. It also is associated with risks if taken during pregnancy, and it is a potassium-sparing diuretic with potential for hyperkalemia, especially in patients with reduced renal function or those who are taking potassium supplements or certain other medications.6,9,11,17 Use of OCs to treat AV also is not without potential risks, with specific warnings and relative contraindications reported, especially in relation to increased risks for cardiac complications, stroke, and thromboembolism.6,9,11,12 Because adult females are in a different stage of life than teenagers, there are defined psychosocial and medical considerations in managing AV in these patients compared with adolescents.5-8,17 Importantly for both clinicians and patients, addressing these differences and considerations can have a major impact on whether or not women with AV experience successful treatment outcomes.1-3,5,6,8,10,13 Skin color and ethnicity also can affect the psychosocial and physical factors that influence the overall management of adult female patients with AV, including selection of therapies and handling long-term visible sequelae that occur in some AV patients, such as dyschromia (eg, persistent or postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation) and acne scarring.5-8,13,17-20

Psychosocial Considerations

With regard to psychosocial, emotional, and attitudinal considerations in women with AV, common findings include concern or frustration regarding the presence of AV beyond adolescence; anxiety; symptoms of depression; decreased self-confidence; increased self-consciousness, especially during public interactions or intimate situations; and interference with steady concentration at work or school.5,6,8,13 Long-term complications of AV, such as dyschromia and acne scarring, are more likely to be encountered in adult patients, especially if they had AV as a teenager, with women reporting that they remain conscious of these adverse sequelae.8 It is estimated that approximately three-fourths of women with AV also had AV as teenagers; therefore, most of them have already used many over-the-counter and prescription therapies and are likely to want treatments that are newer, well-tolerated, safe, and known to be effective in adult women.8,16,17 Convenience and simplicity are vital components of treatment selection and regimen design, as many women with AV frequently face time constraints in their daily routines due to family, social, employment, and home-related demands and responsibilities.6-8,17

Medical Considerations

It is apparent from reports in the literature as well as from clinical experience that some women with AV present with a U-shaped pattern of involvement on the face,5-7,10,13,17 which refers to the presence of predominantly inflammatory papules (many of them deep) and some nodules on the lower face, jawline, and anterolateral neck region, with comedones often sparse or absent.5-7 It often is perceived and may be true that women who present with this pattern of distribution are more androgen sensitive despite having normal serum androgen levels or in some cases exhibit detectable excess androgens (eg, in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome) and may be more likely to respond to hormonal therapies (eg, spironolactone, OCs) than those with mixed facial AV (ie, multiple comedonal and inflammatory acne lesions, not limited to a U-shaped pattern, similar to adolescent AV), but data are limited to support differentiation between the U-shaped pattern group and the conventional mixed facial AV group.5-7,17 Adult and adolescent females in both groups sometimes report perimenstrual flares and frequent persistent papular AV that tends to concentrate on the perioral and chin area.

It is also important to consider that the current literature suggests approximately three-fourths of women with AV report that they also had AV as a teenager, with many indicating the same clinical pattern of AV and approximately one-third reporting AV that is more severe in adulthood than adolescence.5-8,17 The available literature on topical and oral therapies used to treat AV in both adolescent and adult females predominantly focuses on inclusion of both inflammatory and noninflammatory (comedonal) facial AV lesions, does not specifically address or include the U-shaped pattern of AV in adult women for inclusion in studies that evaluate efficacy in this subgroup, and does not include AV involving the neck region and below the jawline margin as part of any study protocols and/or discussions about therapy.5-7,9-12,17,21-26 Involvement of the neck and lower jawline is common in women presenting with the U-shaped pattern of AV, and available studies only evaluate AV involving the face and do not include AV lesions present below the jawline margin. As a result, there is a considerable need for well-designed studies with laboratory assessments to include or exclude underlying detectable excess androgens and to assess the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of specific therapeutic agents both alone and in combination in adult women who present with a U-shaped pattern of AV.17

Other medical considerations that can influence treatment selection and are more likely to be present in adult versus adolescent females include underlying chronic medical disorders; concomitant medications that may interact with other oral agents; potential for pregnancy; age, particularly when prescribing OCs; and the potential desire to stop taking OCs if already used over a prolonged period.6,7

Age-Related Differentiation of Female Subgroups With AV

The age-based dividing line that defines AV in adults versus adolescent females has been described in the literature; however, the basis for published definitions of female subgroups with AV is not well-supported by strong scientific evidence.1-3,5-7,17 The conventional dividing line that was originally selected to define adult females with AV was 25 years of age or older; persistent acne is present both during adolescence and at or after 25 years of age, while late-onset acne is described as AV that first presents at 25 years of age or older.3,5-7

More recently, a range of 18 years or older has been used to classify adult female AV and a range of 12 to 17 years for adolescent female AV in subset analyses that evaluated treatment outcomes in both patient populations from phase 3 pivotal trials completed with adapalene gel 0.3% applied once daily and dapsone gel 5% applied twice daily.14-16 These subanalyses included participants with facial AV that was predominantly moderate in severity, mandated specific lesion count ranges for both comedonal and inflammatory lesions, and included only facial AV that was above the mandibular (jawline) margin.15,16,21,26 Therefore, patients with AV presenting in a U-shaped pattern with involvement below the jawline and on the neck were not included in these study analyses, as these patients were excluded from the phase 3 trials on which the analyses were based. The outcomes of these analyses apply to treatment in women who present with both inflammatory and noninflammatory facial AV lesions, which supports the observation that AV in this patient population is not always predominantly inflammatory and does not always present in a U-shaped distribution.14-16 In fact, a U-shaped pattern of distribution appears to be less common in women with AV than a mixed inflammatory and comedonal distribution that involves the face more diffusely, though more data are needed from well-designed and large-scale epidemiologic and demographic studies.5,14,17

Are there data available on the use of benzoyl peroxide with or without a topical antibiotic in women with AV?

There is a conspicuous absence of prospective clinical trials and retrospective analyses evaluating the specific use of individual AV therapies in adult females, with a particular lack of studies with topical agents (eg, benzoyl peroxide [BP]).14 Subset analyses have been completed for adapalene gel 0.3% and dapsone gel 5%.15,16 Additionally, an age-based subset analysis in females with facial AV also has been completed with clindamycin phosphate (CP) 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel once daily, with data presented but not yet fully published.14

Two identical phase 3, double-blind, randomized, 12-week, 4-arm trials compared treatment outcomes in groups treated with an aqueous-based combination gel formulation containing BP 2.5% and CP 1.2% (n=797), active monad gels (BP [n=809] or CP [n=812]), or vehicle gel (n=395), all applied once daily in patients with facial AV.22 Participants were 12 years or older (mean age range, 19.1–19.6 years; age range, 12.1–70.2 years), were of either gender (approximately 50% split in each study arm), and presented with moderate (approximately 80% of participants) or severe AV (approximately 20% of participants) at baseline. The entry criteria for lesion types and number of lesions were 17 to 40 inflammatory lesions (ie, papules, pustules, <2 nodules)(range of mean number of lesions, 25.8–26.4) and 20 to 100 noninflammatory lesions (ie, closed comedones, open comedones)(range of mean number of lesions, 44.0–47.4). Participant demographics included white (73.9%–77.5%), black/African American (16.1%–20.4%), and Asian (2.1%–3.3%), with the remaining participants distributed among a variety of other ethnic groups such as Native Hawaiian/Native Pacific Islander and Native American Indian/Native Alaskan (collectively <5% in each study arm). Therefore, approximately 1 of every 4 patients had skin of color, which provided good diversity of patients considering the large study size (N=2813). Data analysis included dichotomization of participants by severity rating (moderate or severe based on evaluator global severity score) and skin phototype (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III or IV–VI).22

The pooled results from both studies completed at 68 investigative sites demonstrated that CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was superior in efficacy to each individual monad and to the vehicle in inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion reductions as early as week 4 (P<.001) and at week 12, which was the study end point (P<.001), with superiority also demonstrated in achieving treatment success (defined as a >2 grade improvement according to the evaluator global severity score) compared to the 3 other study arms (P<.001).22 Subject assessments also were consistent with outcomes noted by the investigators. Cutaneous tolerability was favorable and comparable in all 4 study arms with less than 1% of participants discontinuing treatment due to adverse events.22

A subset analysis of the data from the phase 3 pivotal trials with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel was completed to compare reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions in female participants who were younger than 25 years and 25 years of age or older in all 4 study arms. This information has been presented14,17 but has not been previously published. Based on the overall results reported in the phase 3 studies, there were no differentiations in skin tolerability or safety based on participant age, gender, or skin type.22 The subanalysis included a total of 1080 females who were younger than 25 years and 395 females who were 25 years of age or older. The lesion reduction outcomes of this subanalysis are presented in the Table. Statistical analyses of the results among these age groups in the 4 study arms were not completed because the objective was to determine if there were any major or obvious differences in reduction of AV lesions based on the conventional dividing line of 25 years of age in adult women as compared to adolescent females treated with CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel. In addition, the large difference in numbers of female participants between the 2 age groups (>25 years of age, n=395; <25 years of age, n=1080) at least partially confounds both statistical and observational analysis. Among the women who were 25 years of age or older who were included in the subanalysis, 67.0% and 25.8% were between the ages of 25 to 35 years and 36 to 45 years, respectively. Based on the outcomes reported in the phase 3 trials and in this subgroup analysis, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel applied once daily over a 12-week period appeared overall to be comparably effective in females regardless of age and with no apparent adverse events regarding differences in skin tolerability or safety.14,22 One observation that was noted was the possible trend of greater reduction in both lesion types in women older than 35 years versus younger females with the use of the combination gel or BP alone; however, the number of female participants who were older than 35 years of age was substantially less (n=102) than those who were 35 years of age or younger (n=1345), thus precluding support for any definitive conclusions about this possible trend.22

How can CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel be incorporated into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV?

The incorporation of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel into a treatment regimen for women with facial AV is similar to the general use of BP-containing formulations in the overall management of AV.9,14,27,28 Because women with AV commonly present with facial inflammatory lesions and many also with facial comedones, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel is best used once daily in the morning in combination with a topical retinoid in the evening,9,27 which can be achieved with use of CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel in the morning and a topical retinoid (ie, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene) in the evening or CP 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% gel in the evening. It is important to note that cutaneous irritation may be more likely if neck lesions are present; the potential for bleaching of colored fabric by BP also is a practical concern.28 In addition, CP 1.2%–BP 2.5% gel may also be used in combination with topical dapsone, but both products should be applied separately at different times of the day to avoid temporary orange discoloration of the skin, which appears to be an uncommon side effect but remains a possibility based on the product information for dapsone gel 5% with regard to its concomitant use with BP.29,30

1. Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, et al. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21:223-230.

2. Zeichner J. Evaluating and treating the adult female patient with acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1416-1427.

3. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

4. Collier CN, Harper J, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-59.

5. Dreno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

6. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

7. Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

8. Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

9. Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):1-37.

10. Thiboutot DM. Endocrinological evaluation and hormonal therapy for women with difficult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(suppl 3):57-61.

11. Sawaya ME, Samani N. Antiandrogens and androgen receptors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders-Elsevier; 2012:361-374.

12. Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

13. Preneau S, Dreno B. Female acne: a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:277-282.

14. Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. What’s new in the medicine cabinet?: a panoramic review of clinically relevant information for the busy dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-30.

15. Berson D, Alexis A. Adapalene 0.3% for the treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:32-35.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, Gallagher C. Facing up to adult women with acne vulgaris: an analysis of pivotal trial data on dapsone 5% gel in the adult female population. Poster presented at: Fall Clinical Dermatology; October 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

17. Del Rosso JQ. Management of acne with oral spironolactone. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Summer Meeting; August 2013; Boston, MA.

18. Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

19. Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

20. Perkins AC, Cheng CE, Hillebrand GG, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1054-1060.

21. Draelos ZD, Carter E, Maloney JM, et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris [published online ahead of print January 17, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:439.e1-439.e10.

22. Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

23. Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining

1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

24. Fleischer AB Jr, Dinehart S, Stough D, et al. Safety and efficacy of a new extended-release formulation of minocycline. Cutis. 2006;78(suppl 4):21-31.

25. Gollnick HP, Draelos Z, Glenn MJ, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a unique fixed-dose combination topical gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a transatlantic, randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 1670 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1180-1189.

26. Thiboutot D, Arsonnaud S, Soto P. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(suppl 6):3-10.

27. Zeichner JA. Optimizing topical combination therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:313-317.

28. Tanghetti EA, Popp KF. A current review of topical benzoyl peroxide: new perspectives on formulation and utilization. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:17-24.

29. Fleischer AB, Shalita A, Eichenfield LF. Dapsone gel 5% in combination with adapalene gel 0.1%, benzoyl peroxide gel 4% or moisturizer for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:33-40.

30. Aczone (dapsone gel 5%) [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

1. Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, et al. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21:223-230.

2. Zeichner J. Evaluating and treating the adult female patient with acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1416-1427.

3. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

4. Collier CN, Harper J, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-59.

5. Dreno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

6. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

7. Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

8. Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

9. Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):1-37.

10. Thiboutot DM. Endocrinological evaluation and hormonal therapy for women with difficult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(suppl 3):57-61.

11. Sawaya ME, Samani N. Antiandrogens and androgen receptors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders-Elsevier; 2012:361-374.

12. Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

13. Preneau S, Dreno B. Female acne: a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:277-282.

14. Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. What’s new in the medicine cabinet?: a panoramic review of clinically relevant information for the busy dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-30.

15. Berson D, Alexis A. Adapalene 0.3% for the treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:32-35.

16. Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, Gallagher C. Facing up to adult women with acne vulgaris: an analysis of pivotal trial data on dapsone 5% gel in the adult female population. Poster presented at: Fall Clinical Dermatology; October 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

17. Del Rosso JQ. Management of acne with oral spironolactone. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Summer Meeting; August 2013; Boston, MA.

18. Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

19. Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

20. Perkins AC, Cheng CE, Hillebrand GG, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1054-1060.

21. Draelos ZD, Carter E, Maloney JM, et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris [published online ahead of print January 17, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:439.e1-439.e10.

22. Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

23. Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining

1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

24. Fleischer AB Jr, Dinehart S, Stough D, et al. Safety and efficacy of a new extended-release formulation of minocycline. Cutis. 2006;78(suppl 4):21-31.

25. Gollnick HP, Draelos Z, Glenn MJ, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a unique fixed-dose combination topical gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a transatlantic, randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 1670 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1180-1189.

26. Thiboutot D, Arsonnaud S, Soto P. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(suppl 6):3-10.

27. Zeichner JA. Optimizing topical combination therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:313-317.

28. Tanghetti EA, Popp KF. A current review of topical benzoyl peroxide: new perspectives on formulation and utilization. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:17-24.

29. Fleischer AB, Shalita A, Eichenfield LF. Dapsone gel 5% in combination with adapalene gel 0.1%, benzoyl peroxide gel 4% or moisturizer for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:33-40.

30. Aczone (dapsone gel 5%) [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

Practice Points

- Adult women with acne vulgaris (AV) can present with a U-shaped pattern of predominantly inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules involving the lower face, jawline region, and anterior and lateral neck; however, many women present with mixed comedonal and inflammatory acne involving the face more diffusely with a presentation similar to what is typically seen in adolescent AV.

- Topical therapy for adult women with acne has been evaluated in subanalyses of data from phase 3 studies with good efficacy and favorable tolerability shown with adapalene gel 0.3% once daily, dapsone gel 5% twice daily, and clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–benzoyl peroxide (BP) 2.5% gel once daily. The latter agent requires cautious use below the jawline margin, as BP can bleach colored fabric of clothing such as shirts, blouses, and sweaters. These topical agents may be used in combination based on the clinical situation, including with systemic therapies for AV.

Lipidized Dermatofibroma

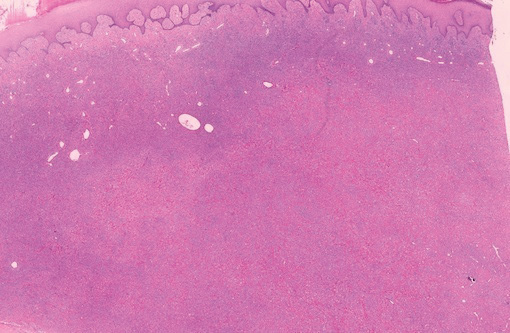

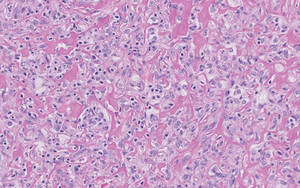

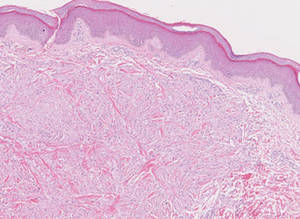

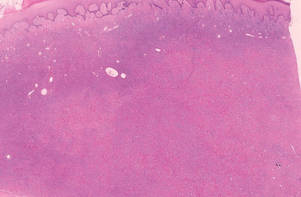

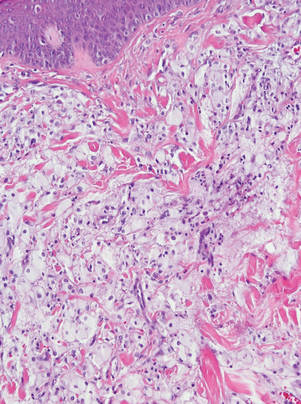

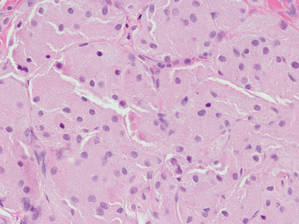

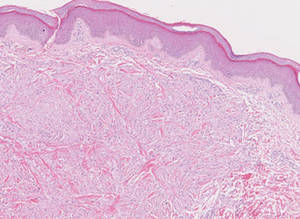

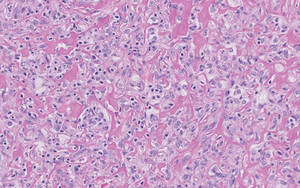

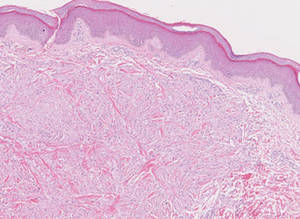

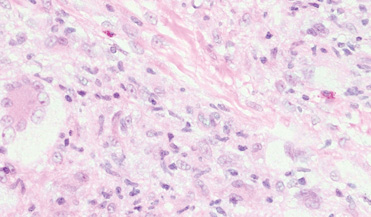

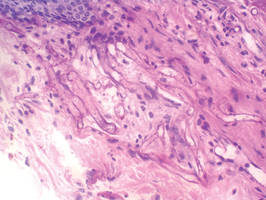

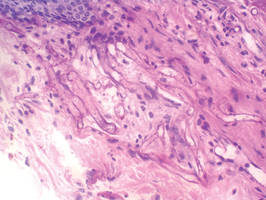

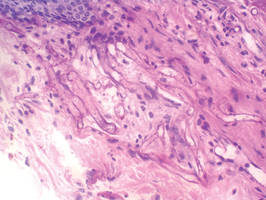

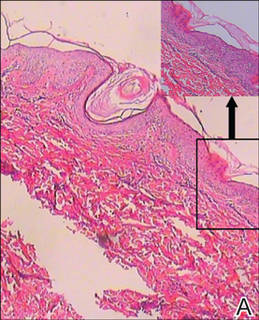

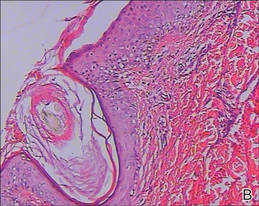

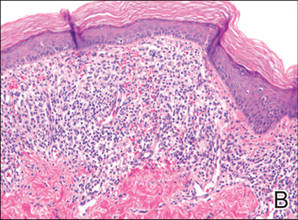

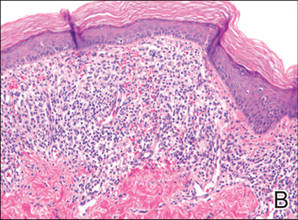

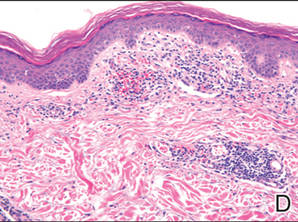

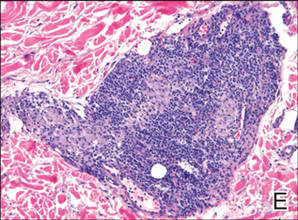

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

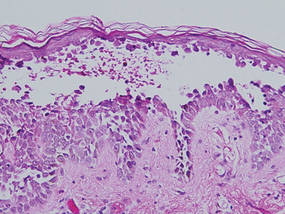

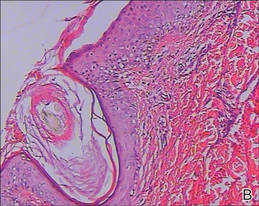

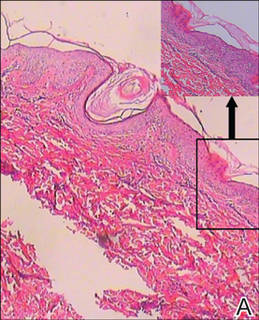

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

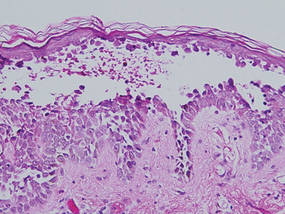

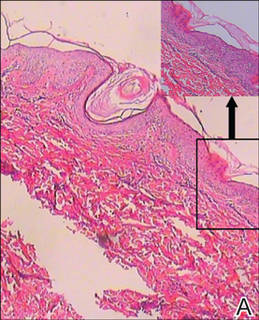

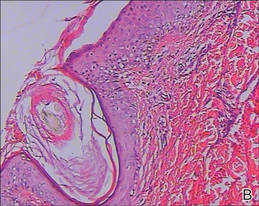

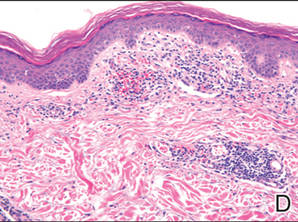

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

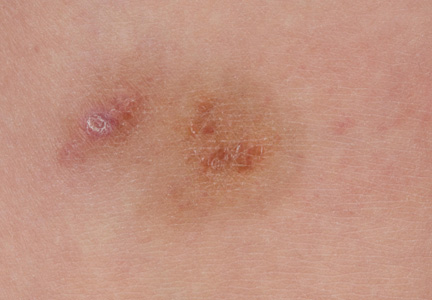

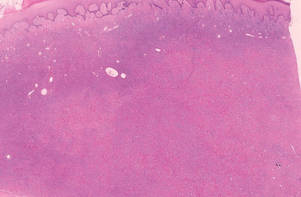

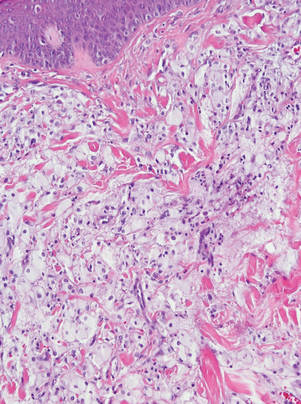

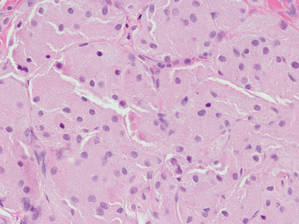

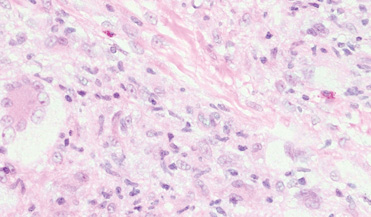

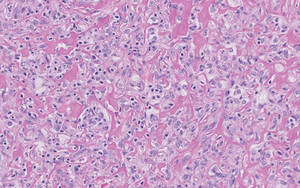

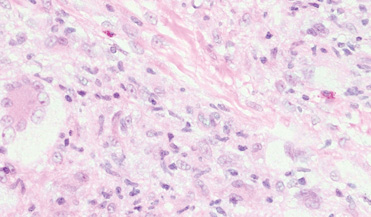

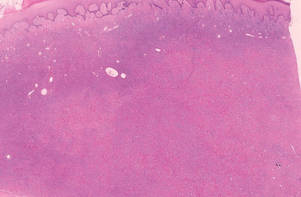

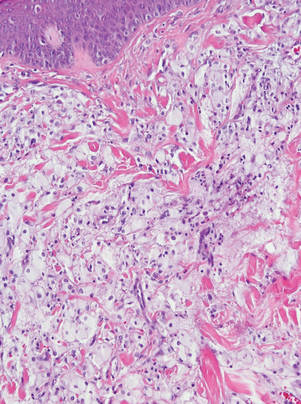

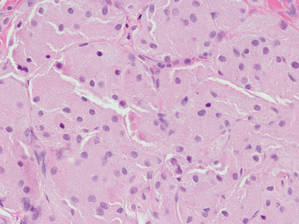

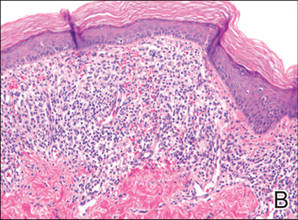

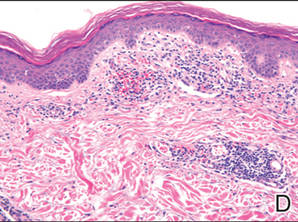

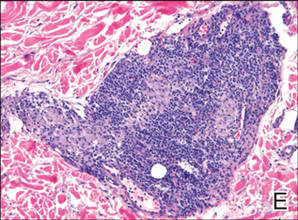

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

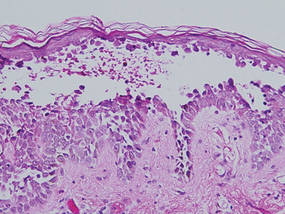

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

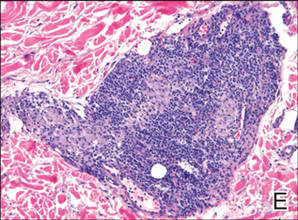

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|