User login

Burning Skin Patches on the Face, Neck, and Chest

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

The Diagnosis: Gastric Acid Dermatitis

After further discussion, the patient indicated that he had vomited during the night of alcohol consumption, and the vomitus remained on the affected areas until the next morning, indicating that excessive alcohol ingestion stimulated abundant secretion of gastric acid, which caused the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of clothing acted as a buffer in the unaffected areas, which helped make the final diagnosis of gastric acid dermatitis. The patient was treated with external application of recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor gel (21,000 IU/5 g) once daily, and the lesions greatly improved within 7 days. The burning pain of the throat, stomach, and esophagus resolved after consultation with an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist.

Gastric acid dermatitis is a new term used to describe an acute skin burn caused by the patient's own gastric acid. Generally, the pH of human gastric acid is between 0.9 and 1.8 but will be diluted after eating and will gradually increase to approximately 3.5, which is not enough to induce burns on the skin.1 In addition, the skin barrier is capable of preventing transient gastric acid corrosion.2,3 However, the release of a large amount of gastric acid after excessive alcohol ingestion coupled with 1 night of lethargy left enough acid and time to induce skin burns in our patient.

Dermatitis caused by other allergic or chemical factors, such as Paederus dermatitis, was excluded, as the patient’s manifestation occurred during the inactive period of Paederus fuscipes. Furthermore, the patient denied any history of contact with chemicals in the last month. Food eruptions primarily manifest as systemic anaphylaxis with eruptive and pruritic rashes after consumption of seafood, eggs, milk, or other proteins, while alcoholic contact dermatitis is a form of irritating dermatitis that could be easily induced again by direct skin contact with alcohol.

Management of gastric acid dermatitis is similar to that for other chemical burns. Because scarring seldom occurs, the central issue is to restore the skin barrier as quickly as possible and to avoid or alleviate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Treatments to restore the skin barrier include recombinant bovine or human-derived basic fibroblast growth factor gel, moist exposed burn ointment, and medical sodium hyaluronate gelatin. To treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some whitening agents such as compound superoxide dismutase arbutin cream and hydroquinone cream as well as the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser are effective to ameliorate the skin condition. If skin burns are on sun-exposed areas, photoprotection is necessary to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgment—We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

- Ergun P, Kipcak S, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and pH of gastric juice in patients with gastrointestinal reflux disease and subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:512-517. doi:10.1097 /MCG.0000000000001560

- Mitamura Y, Ogulur I, Pat Y, et al. Dysregulation of the epithelial barrier by environmental and other exogenous factors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:615-626. doi:10.1111/cod.13959

- Kuo SH, Shen CJ, Shen CF, et al. Role of pH value in clinically relevant diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:107. doi:10.3390 /diagnostics10020107

A 26-year-old man presented with a burning skin rash around the mouth, neck, and chest after 1 night of lethargy due to excessive alcohol consumption 2 days prior. He also reported a sore throat and burning pain in the stomach and esophagus. Physical examination revealed signs of severe epidermal necrosis, including erythema, blisters, serous discharge, and superficial crusts on the perioral region, as well as well-defined erythema on the anterior neck and chest. Gastroscopy and laryngoscopy showed extensive mucosal erosion. A laboratory workup revealed no abnormalities.

Multiple Tumors of the Follicular Infundibulum: A Cutaneous Reaction Pattern?

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI) was first described by Mehregan and Butler1 in a patient with multiple papules. It typically presents as a solitary lesion that mainly affects the face, neck, and upper trunk, and it generally occurs in elderly patients with a female predilection and occasional vulvar involvement. Sometimes TFI may coexist with an unusual trichilemmal tumor or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with sebaceous or sweat duct differentiation. Other features of TFI include an eosinophilic cuticle, ductal differentiation, coronoid lamellae, and desmoplasia. Interestingly, approximately one-fourth of reported TFIs were found to be associated with other cutaneous lesions, including BCC, actinic keratosis, desmoplastic malignant melanoma, junctional melanocytic nevus, trichilemmoma, and epidermal inclusion cyst.2 Eruptive forms of TFI are rare, presenting as macules, smooth or slightly keratotic papules, or depressed lesions with a flesh-colored erythematous or hypopigmented appearance. We report the case of a 49-year-old woman with multiple TFIs and some new features.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented with multiple lesions on the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs of more than 3 years’ duration. According to the patient, multiple small, reddish papules gradually appeared on the arms and legs approximately 3 years prior to presentation and were accompanied by considerable pruritus. She sought medical assistance several times at local clinics. A diagnosis of eczema and prurigo was made and oral antihistamines and topical glucocorticoids were administered for more than 2 years. The pruritus was controlled to some degree but recurred after discontinuation of treatment. Five months later, the lesions flared up suddenly and rapidly to the back and buttocks, just around the skin areas treated with cupping glass, a traditional Chinese therapy, for heat syncope. She reported constant itching that kept her awake at night.

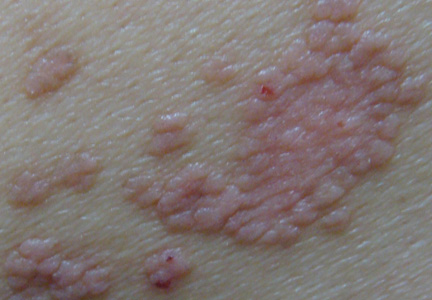

Physical examination revealed hundreds of erythematous maculopapules scattered over the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs. The individual lesions were minimally elevated, irregularly shaped, and slightly scaly, and they were distributed in a relatively symmetrical manner. Some of the lesions coalesced to form small plaques measuring approximately 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter (Figure 1). Interestingly, several annulated lesions with a hypopigmented center and hyperpigmented periphery could be observed at areas treated with cupping glass, showing a typical presentation of the Köbner phenomenon (Figure 2). No obvious association with sun exposure or hair loss was detected. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions.

|

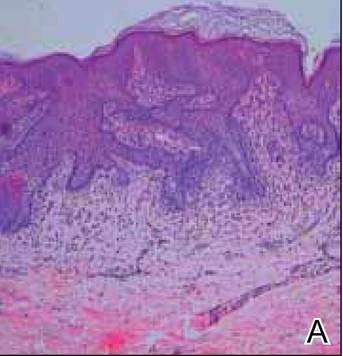

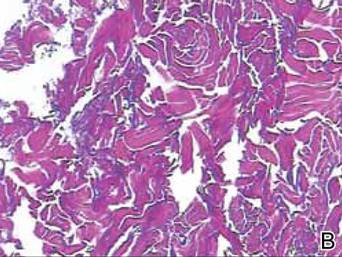

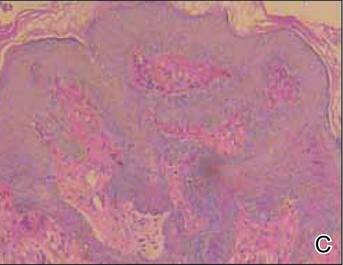

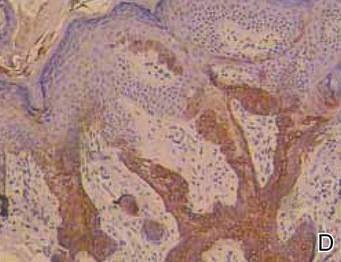

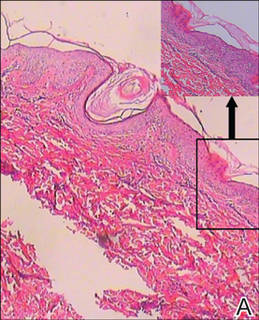

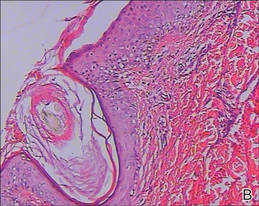

The differential diagnosis included lichen planus, prurigo, and adnexal tumors. Histopathologic examination of biopsies from lesions on the back and around the cupping glass areas revealed a benign platelike proliferation of pale-staining epithelial cells in the papillary dermis connected to the overlying epidermis with a moderate lymphatic cell infiltration (Figure 3A). Weigert staining revealed a network of elastic fibers surrounding the base of the tumor (Figure 3B). The pale epithelial cells were positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the proliferation was positive for keratin 17 (Figure 3D).

These striking clinical and histological findings suggested the lesions were multiple TFIs. Treatment with tretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 months was ineffective. The patient refused treatment with either oral acitretin or dapsone or invasive techniques such as lasers and cryotherapy. She has been on careful follow-up for the last 2 years with new lesions appearing intermittently.

Comment

The etiology of TFI still is unknown but may be related to environmental factors or genetic changes. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum generally are classified as solitary, eruptive, associated with other lesions of Cowden disease, associated with a single tumor, or TFI-like epidermal changes.3 The eruptive form has seldom been reported to date. Eruptive TFIs are nonspecific, ranging in number from several to more than 100. Clinical characteristics and distribution of the lesions can vary from patient to patient, but the lesions tend to be quite monomorphous, even in cases with more than 100 lesions.4 Histopathologic features usually are typical and distinctive, allowing its definite diagnosis. To confirm the diagnosis, the immunohistochemical profile may be useful to characterize its follicular origin, which is positive for keratin 17. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum usually are benign; however, in one patient with more than 100 lesions, there was documented transformation into BCC.5 Due to the potential for malignant transformation as well as its occurrence within the spectrum of lesions associated with Cowden disease,6,7 long-term supervision of TFI is strongly recommended, as was the case with our patient.

A remarkable feature in our case was the patient’s severe pruritus, as most reported cases have been asymptomatic. The increased association with other cutaneous lesions,2 the Köbner phenomenon, and the underlying inflammatory cell infiltration of the tumors in our case strongly suggested that eruptive TFI may represent a kind of cutaneous reaction.

|

Conclusion

The clinical findings of severe pruritus and the Köbner phenomenon in our patient further expand the constellation of the clinical presentation of the eruptive variant of TFI.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:924-927.

2. Abbas O, Mahalingam M. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: an epidermal reaction pattern? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:626633.

3. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

4. Sartorelli AC, Leite FE, Friedman IV, et al. Vitiligoid hypopigmented macules and tumor of the follicular infundibulum [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:68-70.

5. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

6. Starink TM, Meijer CJ, Brownstein MH. The cutaneous pathology of Cowden’s disease: new findings. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:83-93.

7. Weyers W, Hörster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI) was first described by Mehregan and Butler1 in a patient with multiple papules. It typically presents as a solitary lesion that mainly affects the face, neck, and upper trunk, and it generally occurs in elderly patients with a female predilection and occasional vulvar involvement. Sometimes TFI may coexist with an unusual trichilemmal tumor or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with sebaceous or sweat duct differentiation. Other features of TFI include an eosinophilic cuticle, ductal differentiation, coronoid lamellae, and desmoplasia. Interestingly, approximately one-fourth of reported TFIs were found to be associated with other cutaneous lesions, including BCC, actinic keratosis, desmoplastic malignant melanoma, junctional melanocytic nevus, trichilemmoma, and epidermal inclusion cyst.2 Eruptive forms of TFI are rare, presenting as macules, smooth or slightly keratotic papules, or depressed lesions with a flesh-colored erythematous or hypopigmented appearance. We report the case of a 49-year-old woman with multiple TFIs and some new features.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented with multiple lesions on the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs of more than 3 years’ duration. According to the patient, multiple small, reddish papules gradually appeared on the arms and legs approximately 3 years prior to presentation and were accompanied by considerable pruritus. She sought medical assistance several times at local clinics. A diagnosis of eczema and prurigo was made and oral antihistamines and topical glucocorticoids were administered for more than 2 years. The pruritus was controlled to some degree but recurred after discontinuation of treatment. Five months later, the lesions flared up suddenly and rapidly to the back and buttocks, just around the skin areas treated with cupping glass, a traditional Chinese therapy, for heat syncope. She reported constant itching that kept her awake at night.

Physical examination revealed hundreds of erythematous maculopapules scattered over the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs. The individual lesions were minimally elevated, irregularly shaped, and slightly scaly, and they were distributed in a relatively symmetrical manner. Some of the lesions coalesced to form small plaques measuring approximately 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter (Figure 1). Interestingly, several annulated lesions with a hypopigmented center and hyperpigmented periphery could be observed at areas treated with cupping glass, showing a typical presentation of the Köbner phenomenon (Figure 2). No obvious association with sun exposure or hair loss was detected. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions.

|

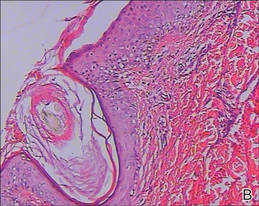

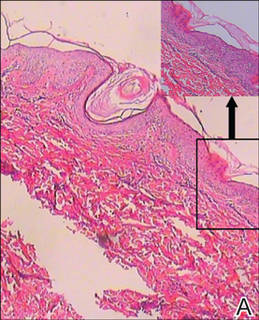

The differential diagnosis included lichen planus, prurigo, and adnexal tumors. Histopathologic examination of biopsies from lesions on the back and around the cupping glass areas revealed a benign platelike proliferation of pale-staining epithelial cells in the papillary dermis connected to the overlying epidermis with a moderate lymphatic cell infiltration (Figure 3A). Weigert staining revealed a network of elastic fibers surrounding the base of the tumor (Figure 3B). The pale epithelial cells were positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the proliferation was positive for keratin 17 (Figure 3D).

These striking clinical and histological findings suggested the lesions were multiple TFIs. Treatment with tretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 months was ineffective. The patient refused treatment with either oral acitretin or dapsone or invasive techniques such as lasers and cryotherapy. She has been on careful follow-up for the last 2 years with new lesions appearing intermittently.

Comment

The etiology of TFI still is unknown but may be related to environmental factors or genetic changes. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum generally are classified as solitary, eruptive, associated with other lesions of Cowden disease, associated with a single tumor, or TFI-like epidermal changes.3 The eruptive form has seldom been reported to date. Eruptive TFIs are nonspecific, ranging in number from several to more than 100. Clinical characteristics and distribution of the lesions can vary from patient to patient, but the lesions tend to be quite monomorphous, even in cases with more than 100 lesions.4 Histopathologic features usually are typical and distinctive, allowing its definite diagnosis. To confirm the diagnosis, the immunohistochemical profile may be useful to characterize its follicular origin, which is positive for keratin 17. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum usually are benign; however, in one patient with more than 100 lesions, there was documented transformation into BCC.5 Due to the potential for malignant transformation as well as its occurrence within the spectrum of lesions associated with Cowden disease,6,7 long-term supervision of TFI is strongly recommended, as was the case with our patient.

A remarkable feature in our case was the patient’s severe pruritus, as most reported cases have been asymptomatic. The increased association with other cutaneous lesions,2 the Köbner phenomenon, and the underlying inflammatory cell infiltration of the tumors in our case strongly suggested that eruptive TFI may represent a kind of cutaneous reaction.

|

Conclusion

The clinical findings of severe pruritus and the Köbner phenomenon in our patient further expand the constellation of the clinical presentation of the eruptive variant of TFI.

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI) was first described by Mehregan and Butler1 in a patient with multiple papules. It typically presents as a solitary lesion that mainly affects the face, neck, and upper trunk, and it generally occurs in elderly patients with a female predilection and occasional vulvar involvement. Sometimes TFI may coexist with an unusual trichilemmal tumor or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with sebaceous or sweat duct differentiation. Other features of TFI include an eosinophilic cuticle, ductal differentiation, coronoid lamellae, and desmoplasia. Interestingly, approximately one-fourth of reported TFIs were found to be associated with other cutaneous lesions, including BCC, actinic keratosis, desmoplastic malignant melanoma, junctional melanocytic nevus, trichilemmoma, and epidermal inclusion cyst.2 Eruptive forms of TFI are rare, presenting as macules, smooth or slightly keratotic papules, or depressed lesions with a flesh-colored erythematous or hypopigmented appearance. We report the case of a 49-year-old woman with multiple TFIs and some new features.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented with multiple lesions on the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs of more than 3 years’ duration. According to the patient, multiple small, reddish papules gradually appeared on the arms and legs approximately 3 years prior to presentation and were accompanied by considerable pruritus. She sought medical assistance several times at local clinics. A diagnosis of eczema and prurigo was made and oral antihistamines and topical glucocorticoids were administered for more than 2 years. The pruritus was controlled to some degree but recurred after discontinuation of treatment. Five months later, the lesions flared up suddenly and rapidly to the back and buttocks, just around the skin areas treated with cupping glass, a traditional Chinese therapy, for heat syncope. She reported constant itching that kept her awake at night.

Physical examination revealed hundreds of erythematous maculopapules scattered over the arms, shoulders, trunk, buttocks, and legs. The individual lesions were minimally elevated, irregularly shaped, and slightly scaly, and they were distributed in a relatively symmetrical manner. Some of the lesions coalesced to form small plaques measuring approximately 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter (Figure 1). Interestingly, several annulated lesions with a hypopigmented center and hyperpigmented periphery could be observed at areas treated with cupping glass, showing a typical presentation of the Köbner phenomenon (Figure 2). No obvious association with sun exposure or hair loss was detected. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions.

|

The differential diagnosis included lichen planus, prurigo, and adnexal tumors. Histopathologic examination of biopsies from lesions on the back and around the cupping glass areas revealed a benign platelike proliferation of pale-staining epithelial cells in the papillary dermis connected to the overlying epidermis with a moderate lymphatic cell infiltration (Figure 3A). Weigert staining revealed a network of elastic fibers surrounding the base of the tumor (Figure 3B). The pale epithelial cells were positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the proliferation was positive for keratin 17 (Figure 3D).

These striking clinical and histological findings suggested the lesions were multiple TFIs. Treatment with tretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 months was ineffective. The patient refused treatment with either oral acitretin or dapsone or invasive techniques such as lasers and cryotherapy. She has been on careful follow-up for the last 2 years with new lesions appearing intermittently.

Comment

The etiology of TFI still is unknown but may be related to environmental factors or genetic changes. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum generally are classified as solitary, eruptive, associated with other lesions of Cowden disease, associated with a single tumor, or TFI-like epidermal changes.3 The eruptive form has seldom been reported to date. Eruptive TFIs are nonspecific, ranging in number from several to more than 100. Clinical characteristics and distribution of the lesions can vary from patient to patient, but the lesions tend to be quite monomorphous, even in cases with more than 100 lesions.4 Histopathologic features usually are typical and distinctive, allowing its definite diagnosis. To confirm the diagnosis, the immunohistochemical profile may be useful to characterize its follicular origin, which is positive for keratin 17. Tumors of the follicular infundibulum usually are benign; however, in one patient with more than 100 lesions, there was documented transformation into BCC.5 Due to the potential for malignant transformation as well as its occurrence within the spectrum of lesions associated with Cowden disease,6,7 long-term supervision of TFI is strongly recommended, as was the case with our patient.

A remarkable feature in our case was the patient’s severe pruritus, as most reported cases have been asymptomatic. The increased association with other cutaneous lesions,2 the Köbner phenomenon, and the underlying inflammatory cell infiltration of the tumors in our case strongly suggested that eruptive TFI may represent a kind of cutaneous reaction.

|

Conclusion

The clinical findings of severe pruritus and the Köbner phenomenon in our patient further expand the constellation of the clinical presentation of the eruptive variant of TFI.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:924-927.

2. Abbas O, Mahalingam M. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: an epidermal reaction pattern? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:626633.

3. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

4. Sartorelli AC, Leite FE, Friedman IV, et al. Vitiligoid hypopigmented macules and tumor of the follicular infundibulum [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:68-70.

5. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

6. Starink TM, Meijer CJ, Brownstein MH. The cutaneous pathology of Cowden’s disease: new findings. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:83-93.

7. Weyers W, Hörster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:924-927.

2. Abbas O, Mahalingam M. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: an epidermal reaction pattern? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:626633.

3. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

4. Sartorelli AC, Leite FE, Friedman IV, et al. Vitiligoid hypopigmented macules and tumor of the follicular infundibulum [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:68-70.

5. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

6. Starink TM, Meijer CJ, Brownstein MH. The cutaneous pathology of Cowden’s disease: new findings. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:83-93.

7. Weyers W, Hörster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

Practice Points

- Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum (TFIs) sometimes may have the potential for malignant transformation; therefore, long-term supervision of TFI is strongly recommended.

- Eruptive forms of TFI are rare. In our patient, severe pruritus, the Köbner phenomenon, and the underlying inflammatory cell infiltration of the tumors strongly suggested that eruptive TFI may represent a kind of cutaneous reaction.

Unilateral Generalized Keratosis Pilaris Following Pregnancy

Keratosis pilaris (KP), also known as lichen planopilaris, is a common inherited disorder characterized by the presence of small folliculocentric keratotic papules that may have surrounding erythema, which gives the skin a stippled appearance resembling gooseflesh.1 Keratosis pilaris has a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the upper arms, thighs, and buttocks; however, a generalized presentation may occur.1-3 Patients usually are asymptomatic with concerns regarding cosmetic appearance. A number of diseases are associated with KP, such as KP atrophicans, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et colli, and ichthyosis vulgaris. Treatment of KP mainly focuses on avoiding skin dryness and adding keratolytic agents when necessary.1 We report the case of a 29-year-old woman who presented with unilateral generalized KP in the second month of her second pregnancy.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented in the second month of pregnancy with follicular hyperkeratotic papules on the right side of the face, neck, trunk, buttocks, arms, and legs with mild pruritus (Figure 1). According to the patient, when she found out she was pregnant, she discovered several reddish gray papules on the right cheek and dorsal aspect of the right hand that rapidly spread to the neck and trunk but remained restricted to the right side of the body. She occasionally experienced mild pruritus.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Several reddish gray follicular papules formed red patches on the right side of the face (A). Numerous small hyperpigmented follicular papules were scattered on the right side of the neck; the left side was devoid of lesions, revealing a sharp distinct demarcation line between the involved and uninvolved skin (B). Reddish gray or pigmented lesions were distributed on the hands and thighs but were restricted to the right side (C and D). | |

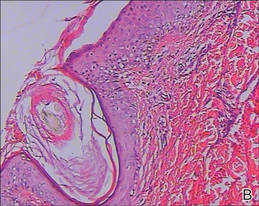

Physical examination revealed numerous small reddish or hyperpigmented follicular papules scattered on the right side of the body, both in the flexor and extensor aspects. The distribution of the lesions did not follow the lines of Blaschko. Strangely, the left side was devoid of lesions, and a sharp distinct line of demarcation separated the involved and uninvolved sides. Physical examination of the scalp, hair, nails, and oral cavity was normal with no atrophy or scarring. The patient’s first pregnancy was aborted in the third month of pregnancy (14 months prior to presentation), but no skin lesions were reported at that time. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions. Histopathologic examination of a biopsy taken from a lesion on the right side of the neck showed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, follicular and interfollicular hyperkeratosis, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration (Figure 2).

Based on the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of unilateral generalized KP was made. No treatment was administered due to the pregnancy. The patient’s skin condition continued to worsen throughout her pregnancy with more widespread and hyperpigmented lesions, but they remained unilateral. The patient showed no obvious improvement 4 months following delivery, and no treatment was administered because the patient was breastfeeding.

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration, which suggested typical keratosis pilaris (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 [inset, original magnification ×100] and ×100). |

Comment

Keratosis pilaris is a common hyperkeratotic condition that typically presents as flesh-colored follicular papules surrounded by varying degrees of perifollicular erythema. Occasionally, inflammatory acneform pustules and papules may appear.1,2 Keratosis pilaris usually presents between the ages of 2 and 3 years, flourishes until 20 years of age, and usually subsides in adulthood.4 Xerotic or atopic individuals are prone to develop KP.2 Other conditions associated with KP include ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia with papular lesions, cardiofasciocutaneous syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia with corkscrew hairs, and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome.5 Although its etiology is uncertain, KP is thought to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.

Histologically, the lesions result from the formation of an orthokeratotic plug, which may contain twisted hairs, that blocks and dilates the orifice and upper portion of the follicular infundibulum. Mild perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrates usually are present in the adjacent dermis.5 Most cases of KP involve lesions that are bilaterally distributed. One report described a 5-year-old girl with lesions that were limited to the right cheek. They were diagnosed as atrophoderma vermiculata, a form of KP atrophicans, which is a less common variant of KP.6 Another report described a 2-year-old girl who developed KP 7 months after birth, which was the only case we found in the English-language literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms keratosis pilaris, hemicorporal, and pregnancy, with near-total involvement of one side of the body. The authors believed this peculiar manifestation was probably caused by an inherited segmental anomaly from a postzygotic genetic mutation.7

Our patient’s condition was unusual because the generalized lesions were unilaterally distributed and they occurred early in the pregnancy. Some studies have indicated that hormonal influences may play a role in the development of KP.3,8 Our case also demonstrates KP as a condition in which the onset and severity of the disorder may be associated with the hormonal changes in pregnancy. Additionally, it is worth noting that the lesions presented during the patient’s second pregnancy, but there were no lesions reported during her first pregnancy 14 months prior, which was aborted in the third month. We cannot explain this phenomenon and cannot predict if the lesions will recur in future pregnancies.

Conclusion

We suggest that both a genetic mutation and pregnancy-induced hormonal changes played possible roles in the development and progress of unilateral generalized KP in our patient. Follow-up is necessary in these patients and further work needs to be done to reveal the underlying mechanism.

1. Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

2. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000.

3. Jackson JB, Touma SC, Norton AB. Keratosis pilaris in pregnancy: an unrecognized dematosis of pregnancy? W V Med J. 2004;100:26-28.

4. Poskitt L, Wilkinson JD. Natural history of keratosis pilaris. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:711-713.

5. Griffiths WAD, Judge MR, Leigh IM. Disorders of keratinisation. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1998.

6. Nico MM, Valente NY, Sotto MN. Folliculitis ulerythematosa reticulata (atrophoderma vermiculata): early detection of a case with unilateral lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:285-286.

7. Ehsani A, Namazi MR, Barikbin B, et al. Unilaterally generalized keratosis pilaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:361-362.

8. Barth JH, Wojnarowska F, Dawber RP. Is keratosis pilaris another androgen-dependent dermatosis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:240-241.

Keratosis pilaris (KP), also known as lichen planopilaris, is a common inherited disorder characterized by the presence of small folliculocentric keratotic papules that may have surrounding erythema, which gives the skin a stippled appearance resembling gooseflesh.1 Keratosis pilaris has a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the upper arms, thighs, and buttocks; however, a generalized presentation may occur.1-3 Patients usually are asymptomatic with concerns regarding cosmetic appearance. A number of diseases are associated with KP, such as KP atrophicans, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et colli, and ichthyosis vulgaris. Treatment of KP mainly focuses on avoiding skin dryness and adding keratolytic agents when necessary.1 We report the case of a 29-year-old woman who presented with unilateral generalized KP in the second month of her second pregnancy.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented in the second month of pregnancy with follicular hyperkeratotic papules on the right side of the face, neck, trunk, buttocks, arms, and legs with mild pruritus (Figure 1). According to the patient, when she found out she was pregnant, she discovered several reddish gray papules on the right cheek and dorsal aspect of the right hand that rapidly spread to the neck and trunk but remained restricted to the right side of the body. She occasionally experienced mild pruritus.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Several reddish gray follicular papules formed red patches on the right side of the face (A). Numerous small hyperpigmented follicular papules were scattered on the right side of the neck; the left side was devoid of lesions, revealing a sharp distinct demarcation line between the involved and uninvolved skin (B). Reddish gray or pigmented lesions were distributed on the hands and thighs but were restricted to the right side (C and D). | |

Physical examination revealed numerous small reddish or hyperpigmented follicular papules scattered on the right side of the body, both in the flexor and extensor aspects. The distribution of the lesions did not follow the lines of Blaschko. Strangely, the left side was devoid of lesions, and a sharp distinct line of demarcation separated the involved and uninvolved sides. Physical examination of the scalp, hair, nails, and oral cavity was normal with no atrophy or scarring. The patient’s first pregnancy was aborted in the third month of pregnancy (14 months prior to presentation), but no skin lesions were reported at that time. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions. Histopathologic examination of a biopsy taken from a lesion on the right side of the neck showed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, follicular and interfollicular hyperkeratosis, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration (Figure 2).

Based on the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of unilateral generalized KP was made. No treatment was administered due to the pregnancy. The patient’s skin condition continued to worsen throughout her pregnancy with more widespread and hyperpigmented lesions, but they remained unilateral. The patient showed no obvious improvement 4 months following delivery, and no treatment was administered because the patient was breastfeeding.

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration, which suggested typical keratosis pilaris (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 [inset, original magnification ×100] and ×100). |

Comment

Keratosis pilaris is a common hyperkeratotic condition that typically presents as flesh-colored follicular papules surrounded by varying degrees of perifollicular erythema. Occasionally, inflammatory acneform pustules and papules may appear.1,2 Keratosis pilaris usually presents between the ages of 2 and 3 years, flourishes until 20 years of age, and usually subsides in adulthood.4 Xerotic or atopic individuals are prone to develop KP.2 Other conditions associated with KP include ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia with papular lesions, cardiofasciocutaneous syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia with corkscrew hairs, and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome.5 Although its etiology is uncertain, KP is thought to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.

Histologically, the lesions result from the formation of an orthokeratotic plug, which may contain twisted hairs, that blocks and dilates the orifice and upper portion of the follicular infundibulum. Mild perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrates usually are present in the adjacent dermis.5 Most cases of KP involve lesions that are bilaterally distributed. One report described a 5-year-old girl with lesions that were limited to the right cheek. They were diagnosed as atrophoderma vermiculata, a form of KP atrophicans, which is a less common variant of KP.6 Another report described a 2-year-old girl who developed KP 7 months after birth, which was the only case we found in the English-language literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms keratosis pilaris, hemicorporal, and pregnancy, with near-total involvement of one side of the body. The authors believed this peculiar manifestation was probably caused by an inherited segmental anomaly from a postzygotic genetic mutation.7

Our patient’s condition was unusual because the generalized lesions were unilaterally distributed and they occurred early in the pregnancy. Some studies have indicated that hormonal influences may play a role in the development of KP.3,8 Our case also demonstrates KP as a condition in which the onset and severity of the disorder may be associated with the hormonal changes in pregnancy. Additionally, it is worth noting that the lesions presented during the patient’s second pregnancy, but there were no lesions reported during her first pregnancy 14 months prior, which was aborted in the third month. We cannot explain this phenomenon and cannot predict if the lesions will recur in future pregnancies.

Conclusion

We suggest that both a genetic mutation and pregnancy-induced hormonal changes played possible roles in the development and progress of unilateral generalized KP in our patient. Follow-up is necessary in these patients and further work needs to be done to reveal the underlying mechanism.

Keratosis pilaris (KP), also known as lichen planopilaris, is a common inherited disorder characterized by the presence of small folliculocentric keratotic papules that may have surrounding erythema, which gives the skin a stippled appearance resembling gooseflesh.1 Keratosis pilaris has a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the upper arms, thighs, and buttocks; however, a generalized presentation may occur.1-3 Patients usually are asymptomatic with concerns regarding cosmetic appearance. A number of diseases are associated with KP, such as KP atrophicans, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et colli, and ichthyosis vulgaris. Treatment of KP mainly focuses on avoiding skin dryness and adding keratolytic agents when necessary.1 We report the case of a 29-year-old woman who presented with unilateral generalized KP in the second month of her second pregnancy.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented in the second month of pregnancy with follicular hyperkeratotic papules on the right side of the face, neck, trunk, buttocks, arms, and legs with mild pruritus (Figure 1). According to the patient, when she found out she was pregnant, she discovered several reddish gray papules on the right cheek and dorsal aspect of the right hand that rapidly spread to the neck and trunk but remained restricted to the right side of the body. She occasionally experienced mild pruritus.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Several reddish gray follicular papules formed red patches on the right side of the face (A). Numerous small hyperpigmented follicular papules were scattered on the right side of the neck; the left side was devoid of lesions, revealing a sharp distinct demarcation line between the involved and uninvolved skin (B). Reddish gray or pigmented lesions were distributed on the hands and thighs but were restricted to the right side (C and D). | |

Physical examination revealed numerous small reddish or hyperpigmented follicular papules scattered on the right side of the body, both in the flexor and extensor aspects. The distribution of the lesions did not follow the lines of Blaschko. Strangely, the left side was devoid of lesions, and a sharp distinct line of demarcation separated the involved and uninvolved sides. Physical examination of the scalp, hair, nails, and oral cavity was normal with no atrophy or scarring. The patient’s first pregnancy was aborted in the third month of pregnancy (14 months prior to presentation), but no skin lesions were reported at that time. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and there was no known family history of similar skin lesions. Histopathologic examination of a biopsy taken from a lesion on the right side of the neck showed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, follicular and interfollicular hyperkeratosis, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration (Figure 2).

Based on the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of unilateral generalized KP was made. No treatment was administered due to the pregnancy. The patient’s skin condition continued to worsen throughout her pregnancy with more widespread and hyperpigmented lesions, but they remained unilateral. The patient showed no obvious improvement 4 months following delivery, and no treatment was administered because the patient was breastfeeding.

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, dilated hair follicles containing keratinous plugs, dermal vascular dilatation and congestion, and mild perivascular inflammatory infiltration, which suggested typical keratosis pilaris (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 [inset, original magnification ×100] and ×100). |

Comment

Keratosis pilaris is a common hyperkeratotic condition that typically presents as flesh-colored follicular papules surrounded by varying degrees of perifollicular erythema. Occasionally, inflammatory acneform pustules and papules may appear.1,2 Keratosis pilaris usually presents between the ages of 2 and 3 years, flourishes until 20 years of age, and usually subsides in adulthood.4 Xerotic or atopic individuals are prone to develop KP.2 Other conditions associated with KP include ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia with papular lesions, cardiofasciocutaneous syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia with corkscrew hairs, and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome.5 Although its etiology is uncertain, KP is thought to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.

Histologically, the lesions result from the formation of an orthokeratotic plug, which may contain twisted hairs, that blocks and dilates the orifice and upper portion of the follicular infundibulum. Mild perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrates usually are present in the adjacent dermis.5 Most cases of KP involve lesions that are bilaterally distributed. One report described a 5-year-old girl with lesions that were limited to the right cheek. They were diagnosed as atrophoderma vermiculata, a form of KP atrophicans, which is a less common variant of KP.6 Another report described a 2-year-old girl who developed KP 7 months after birth, which was the only case we found in the English-language literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms keratosis pilaris, hemicorporal, and pregnancy, with near-total involvement of one side of the body. The authors believed this peculiar manifestation was probably caused by an inherited segmental anomaly from a postzygotic genetic mutation.7

Our patient’s condition was unusual because the generalized lesions were unilaterally distributed and they occurred early in the pregnancy. Some studies have indicated that hormonal influences may play a role in the development of KP.3,8 Our case also demonstrates KP as a condition in which the onset and severity of the disorder may be associated with the hormonal changes in pregnancy. Additionally, it is worth noting that the lesions presented during the patient’s second pregnancy, but there were no lesions reported during her first pregnancy 14 months prior, which was aborted in the third month. We cannot explain this phenomenon and cannot predict if the lesions will recur in future pregnancies.

Conclusion

We suggest that both a genetic mutation and pregnancy-induced hormonal changes played possible roles in the development and progress of unilateral generalized KP in our patient. Follow-up is necessary in these patients and further work needs to be done to reveal the underlying mechanism.

1. Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

2. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000.

3. Jackson JB, Touma SC, Norton AB. Keratosis pilaris in pregnancy: an unrecognized dematosis of pregnancy? W V Med J. 2004;100:26-28.

4. Poskitt L, Wilkinson JD. Natural history of keratosis pilaris. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:711-713.

5. Griffiths WAD, Judge MR, Leigh IM. Disorders of keratinisation. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1998.

6. Nico MM, Valente NY, Sotto MN. Folliculitis ulerythematosa reticulata (atrophoderma vermiculata): early detection of a case with unilateral lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:285-286.

7. Ehsani A, Namazi MR, Barikbin B, et al. Unilaterally generalized keratosis pilaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:361-362.

8. Barth JH, Wojnarowska F, Dawber RP. Is keratosis pilaris another androgen-dependent dermatosis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:240-241.

1. Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

2. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000.

3. Jackson JB, Touma SC, Norton AB. Keratosis pilaris in pregnancy: an unrecognized dematosis of pregnancy? W V Med J. 2004;100:26-28.

4. Poskitt L, Wilkinson JD. Natural history of keratosis pilaris. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:711-713.

5. Griffiths WAD, Judge MR, Leigh IM. Disorders of keratinisation. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1998.

6. Nico MM, Valente NY, Sotto MN. Folliculitis ulerythematosa reticulata (atrophoderma vermiculata): early detection of a case with unilateral lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:285-286.

7. Ehsani A, Namazi MR, Barikbin B, et al. Unilaterally generalized keratosis pilaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:361-362.

8. Barth JH, Wojnarowska F, Dawber RP. Is keratosis pilaris another androgen-dependent dermatosis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:240-241.

Practice Points

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common disorder, with a genetic background and hormonal changes playing possible roles in its development. It also may be associated with a number of diseases.

- The skin lesions of KP usually are bilaterally distributed, either in a generalized or localized distribution. Unilateral lesions are rare. The underlying mechanism of unilateral generalized KP remains unknown.