User login

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

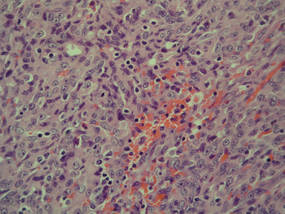

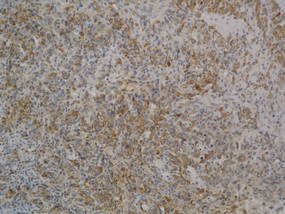

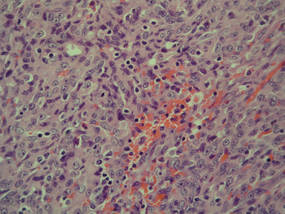

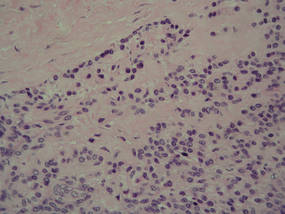

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

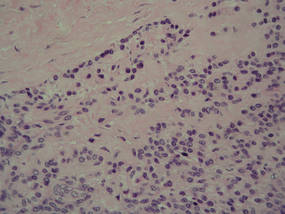

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

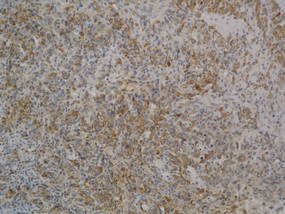

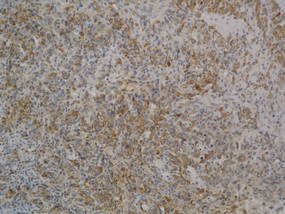

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

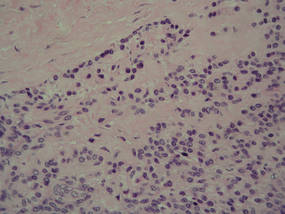

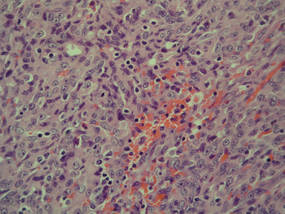

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

Practice Points

- Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses.

- The term glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP) was introduced to describe glomus tumors that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy.

- Complete excision with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs.