User login

Dystrophic Calcinosis Cutis: Treatment With Intravenous Sodium Thiosulfate

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

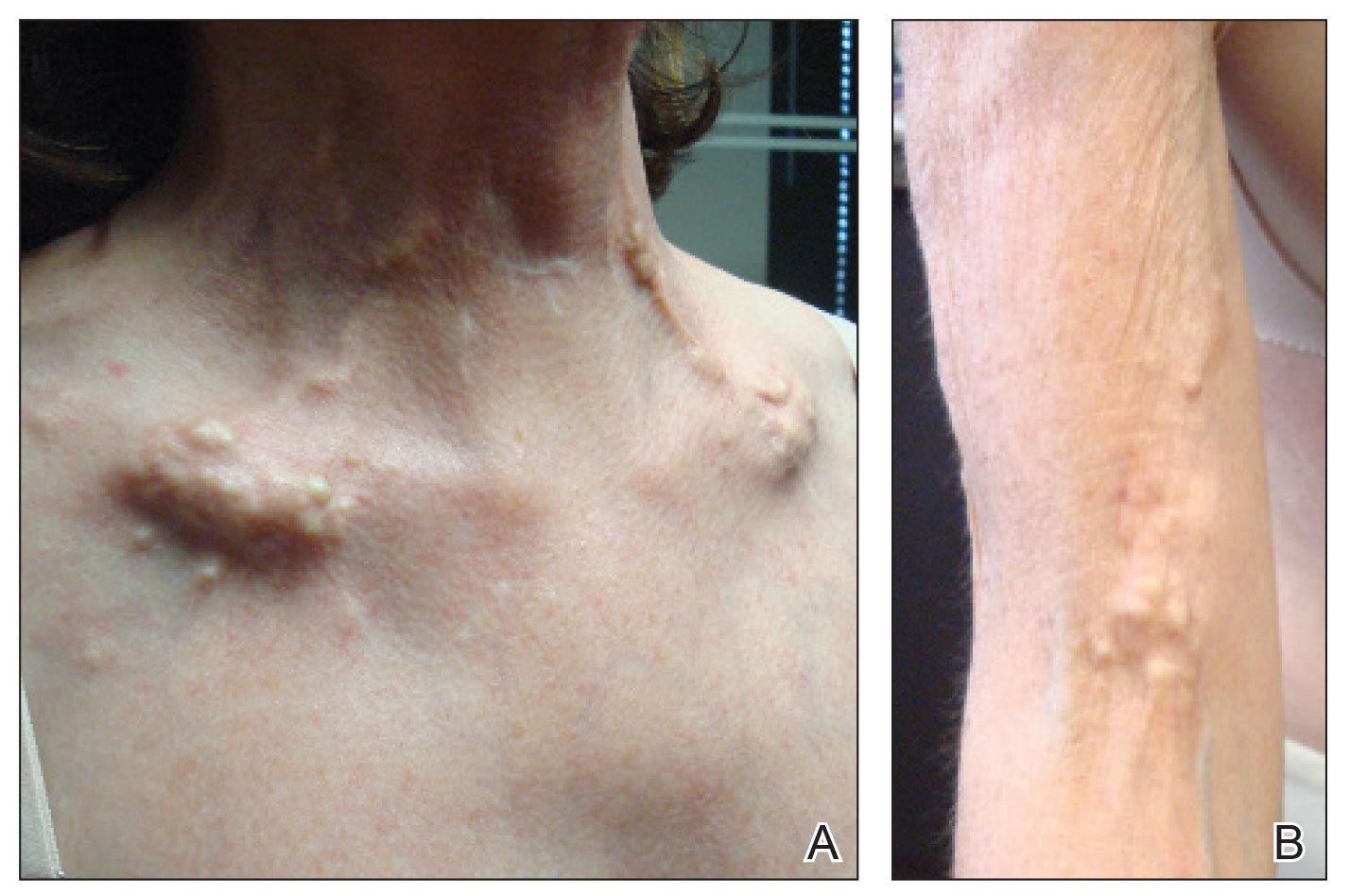

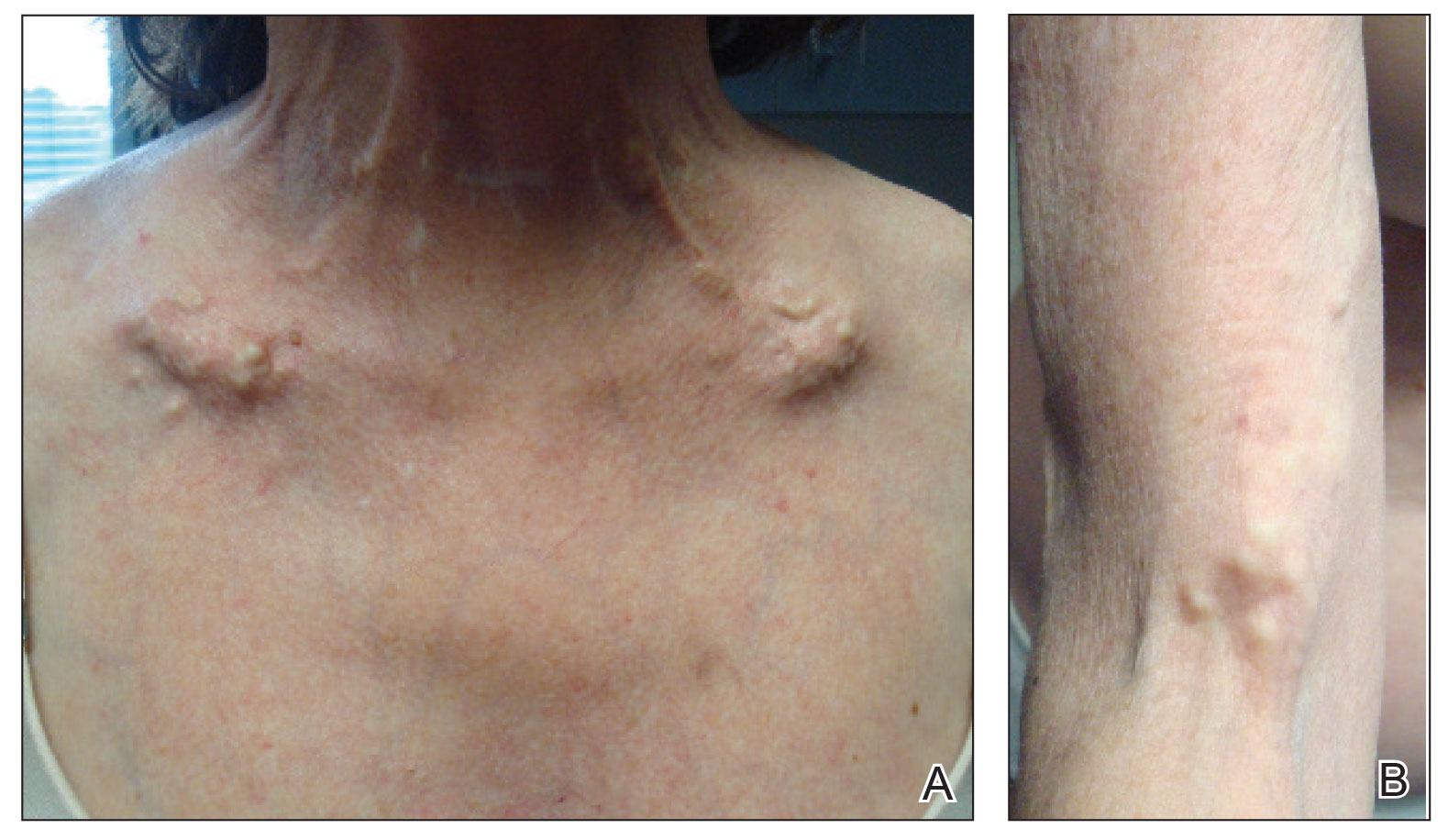

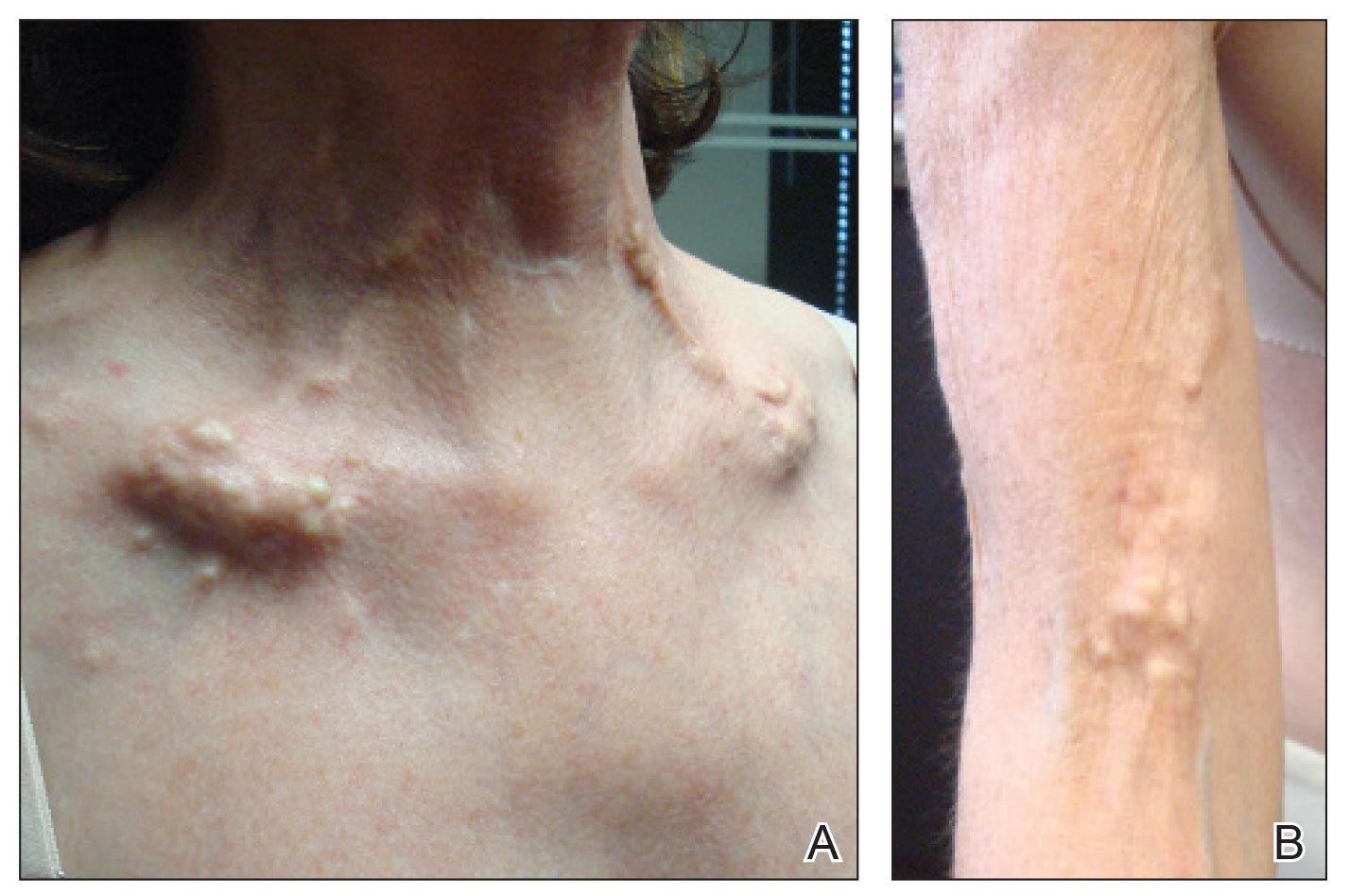

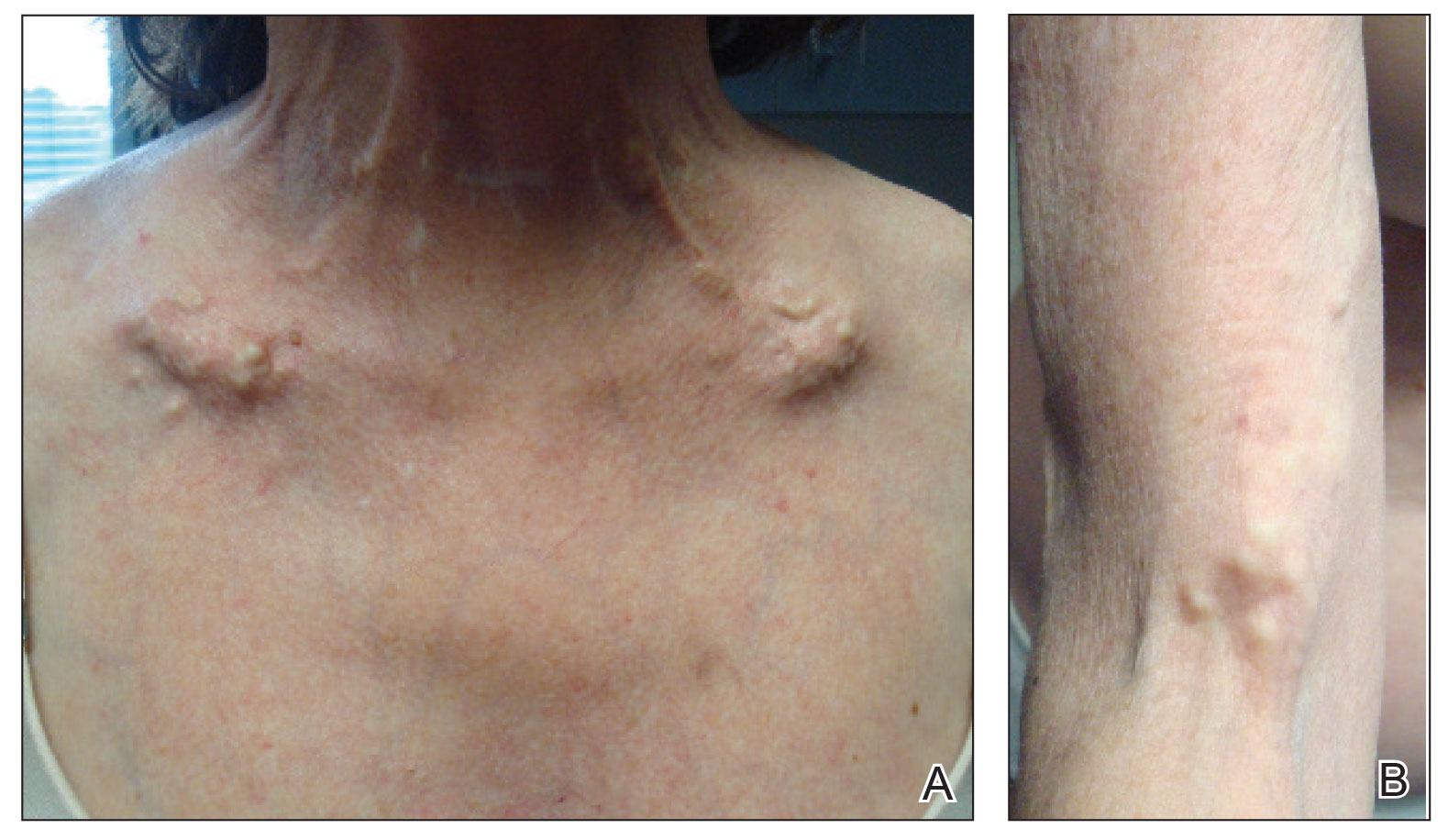

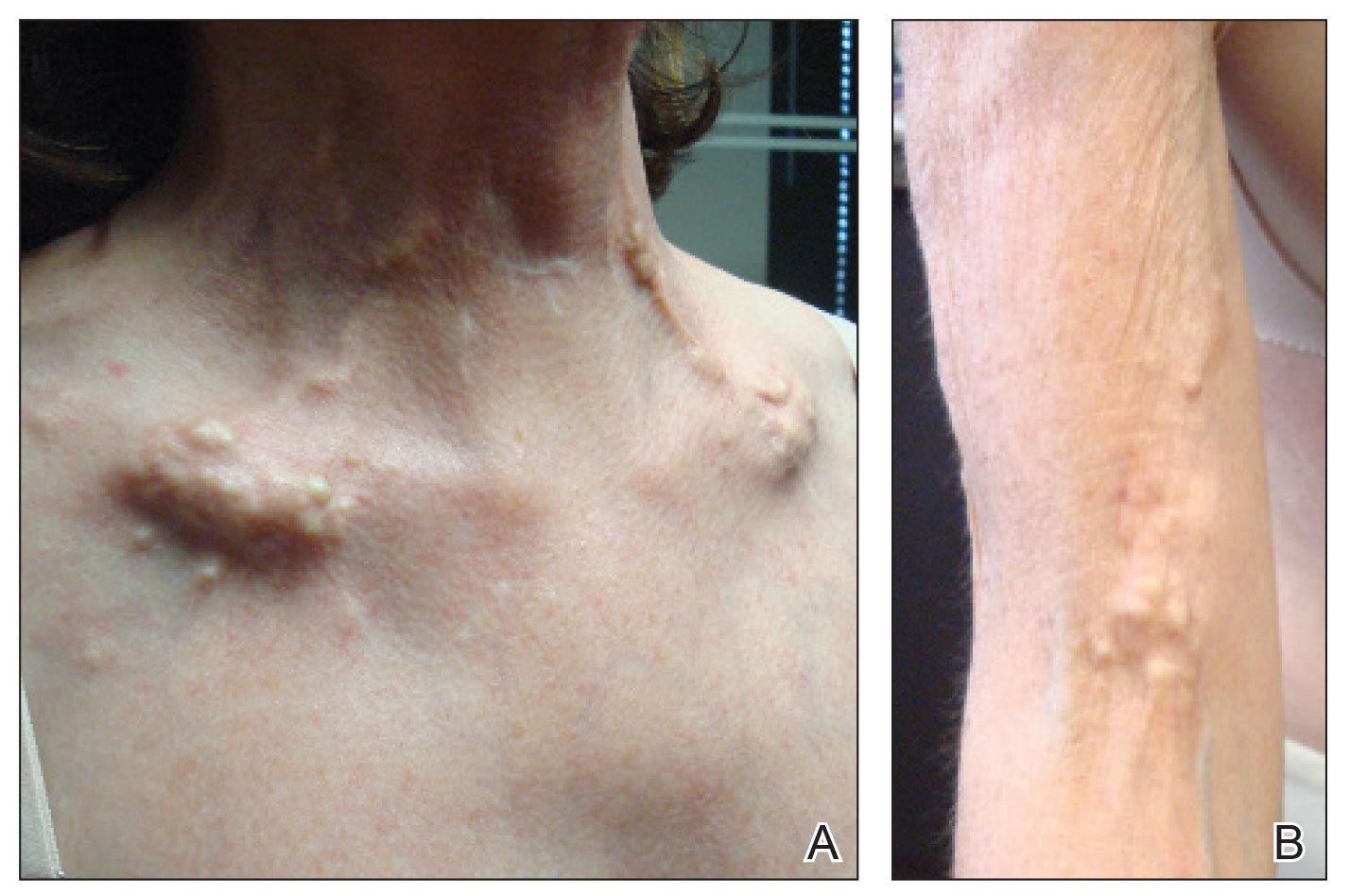

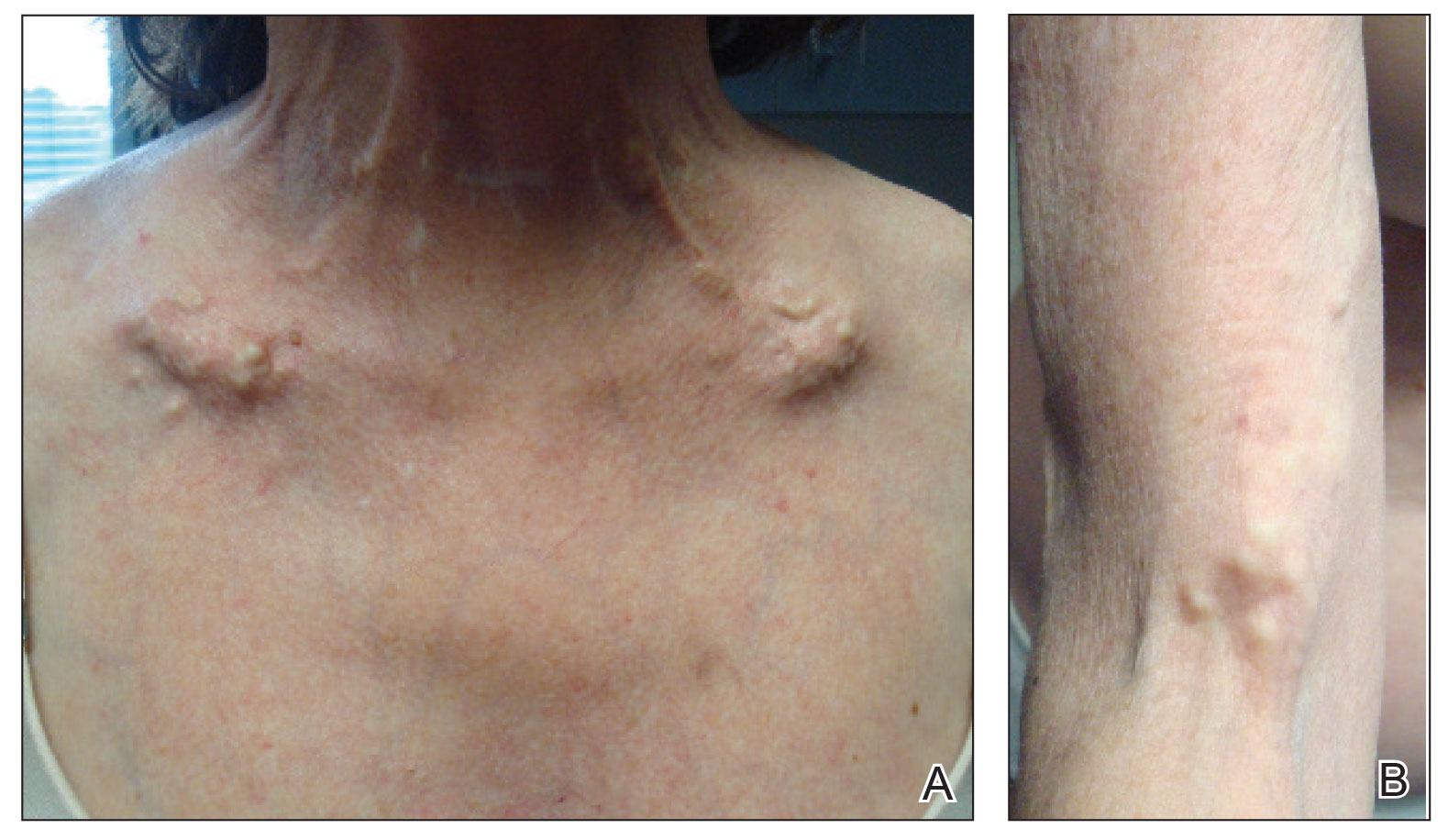

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

Practice Points

- Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a potentially debilitating condition with limited effective therapies.

- Consider intravenous sodium thiosulfate in patients with diffuse and severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Cutaneous Adenosquamous Carcinoma: A Rare Neoplasm With Biphasic Differentiation

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.

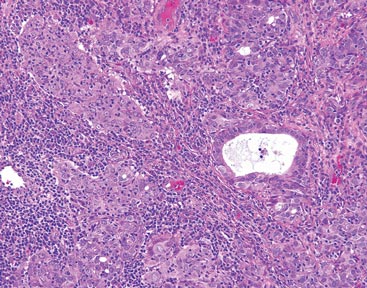

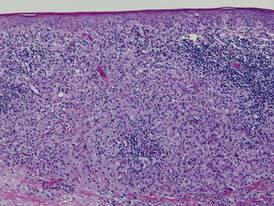

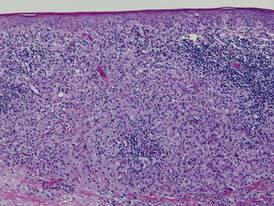

Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).

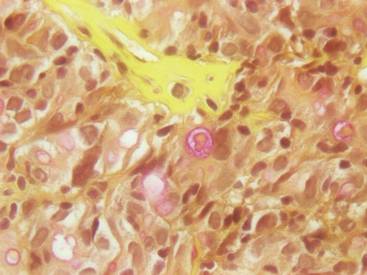

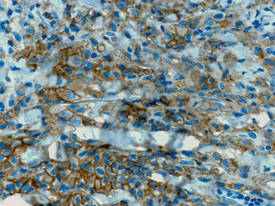

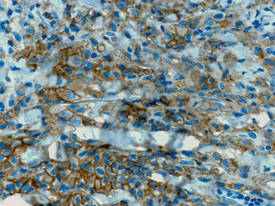

Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

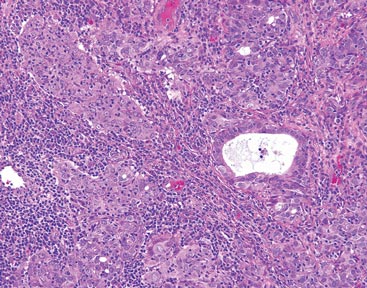

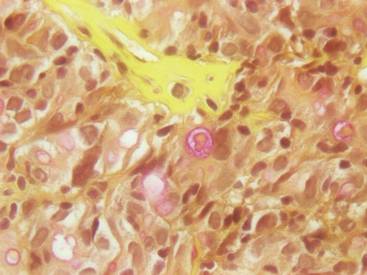

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.

Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).

Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

Case Report

An 85-year-old woman presented with a painless red plaque on the right bicep of 5 years’ duration. The patient had not seen a physician in the last 63 years and had unsuccessfully attempted to treat the plaque by occlusion with an adhesive bandage. A review of systems was negative for pain, pruritus, bleeding, fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats. Physical examination revealed a raised, 2×4×1-cm, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep (Figure 1). Full-body skin examination revealed erythema and swelling of the right wrist and forearm consistent with cellulitis as well as tinea pedis and onychomycosis of the toenails of both feet.

Figure 1. A raised, red, nontender, ulcerated plaque with slight exudate and gelatinous texture on the right bicep.

Figure 2. The tumor was comprised of gland-forming cells and exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures (H&E, original magnification ×100).

Figure 3. Mucicarmine staining highlighted sialomucin within the glandular component (original magnification ×400). |

Hematoxylin and eosin as well as mucicarmine staining of a shave biopsy from the lesion demonstrated an invasive epithelial neoplasm comprised of squamoid and gland-forming cells broadly attached to the epidermis, which suggested a primary cutaneous origin (Figures 2 and 3). The tumor cells were arranged in infiltrating cords and nests; they exhibited crowding, pleomorphism, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic division figures. Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) within the glandular component was highlighted on mucicarmine staining. The gland-forming segment of the tumor was strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7. Gastrointestinal tumors were excluded on negative CDX2 and CK20 staining, pulmonary and thyroid tumors were excluded on negative thyroid transcription factor 1 staining, and endometrial and ovarian tumors were excluded with negative estrogen receptor staining. On physical examination the breasts were soft, nontender, and without deformity. A chest radiograph demonstrated normal heart size and pulmonary vasculature with mild bibasilar atelectasis and no areas of consolidation. Given these clinical findings along with a negative history of cancer and negative estrogen receptor staining, breast cancer was excluded from the differential diagnosis, and the diagnosis of cASC was made. The tumor was excised using Mohs micrographic surgery and was free of recurrence at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Comment

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an aggressive subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that was first described in 1985.1 It typically presents as an erythematous, indurated, keratotic papule or plaque with a predilection for the face, scalp, and upper extremities of immunocompromised individuals and elderly men.2,3 Biopsies generally demonstrate a malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the epidermis and exhibiting squamous and glandular differentiation. The glandular segment usually is indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma and can be highlighted on CK7, carcinoembryonic antigen, mucicarmine, and periodic acid–Schiff staining. The squamous segment typically is indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and shows aberrant keratinization and intercellular bridges. Tumors often are deeply invasive, poorly differentiated, and associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction. Local recurrence rates are between 22% and 26%,4 but metastasis is rare. Surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy. When clear margins cannot be obtained using Mohs micrographic surgery, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.2

The differential diagnosis for cASC includes cutaneous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, cutaneous acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous manifestations of metastatic visceral adenosquamous carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma sometimes is used interchangeably with cASC in the literature, but it is a different cutaneous neoplasm that forms goblet cells, intermediate cells, and squamous cells. It is considered the cutaneous analogue of salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and does not exhibit the anaplasia, stromal desmoplasia, and aggressive course of cASC.5 The acantholytic subtype of squamous cell carcinoma forms glandlike spaces due to poor adhesion between keratinocytes, but the glandlike spaces do not form mucin or stain positive for CK7 or carcinoembryonic antigen. Adenosquamous carcinomas are well recognized in the lungs, breasts, genitourinary tract, pancreas, and gastroenteric system. Visceral tumor metastasis to the skin should be excluded by appropriate screening.

Conclusion

Although cASCs are not commonly encountered in clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of these lesions is important due to their potentially aggressive behavior. Misdiagnosis and improper treatment could be attributed to lack of awareness of this type of lesion.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

1. Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin-and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

2. Fu JM, McCalmont T, Siegrid YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

3. Ko JK, Leffel DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of 9 cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

4. Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

5. Riedlinger WF, Hurley MY, Dehner LP, et al. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the skin: a distinct entity from adenosquamous carcinoma: a case study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:131-135.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC) is an extremely rare malignant neoplasm with histologic similarities to both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

- Mohs micrographic surgery for excision is recommended; however, adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors also have been used to treat locally recurrent cASCs.

Adult-Type Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Minimal Treatment for Maximal Results

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

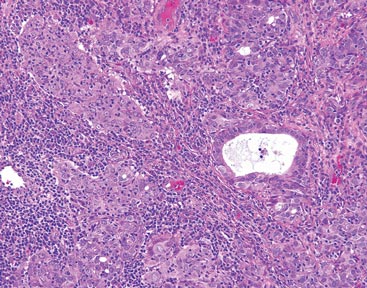

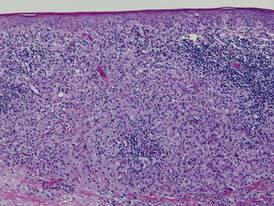

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

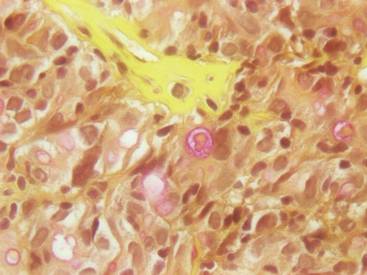

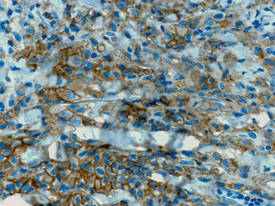

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.