User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Diagnose Pediatric Melanoma Using the CUP Criteria

It is typically perceived that cutaneous malignancies in childhood and adolescence are uncommon, but the incidence of melanoma in this patient population is increasing. In 2014, the American Cancer Society estimated 310 cases of malignant melanoma in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, making it the 8th most prevalent cancer in adolescents. Based on US data for pediatric patients aged 0 to 19 years (2006-2010), melanoma was reported to be more common in girls and non-Hispanic whites. For pediatric cases diagnosed in 2003-2009, the 5-year observed survival rate was 95%, an increase from 83% in 1975-1979. These findings serve as a reminder for practitioners to encourage young patients to practice good sun protection habits. Even if patients are careful, melanomas do occur in childhood and early diagnosis is key.

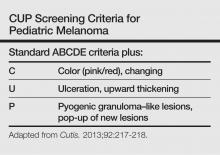

The ABCDE—asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter, evolving—criteria have been used for melanoma screening in adults and may be helpful in detecting pediatric melanoma. However, Silverberg and McCuaig proposed a mnemonic specifically for screening children called the CUP criteria. Because melanomas of childhood do not necessarily arise in a preexisting nevus, the CUP criteria take into account melanomas that arise de novo and may present histologically as spitzoid neoplasms. The atypical presentation of melanomas in childhood includes color uniformity (pink/red), ulceration and upward thickening, and pyogenic granuloma–like lesions and pop-up of new lesions.

For more information on practice modifications from these screening criteria for pediatric melanoma, read Silverberg and McCuaig’s Cutis article “Melanoma in Childhood: Changing Our Mind-set.”

It is typically perceived that cutaneous malignancies in childhood and adolescence are uncommon, but the incidence of melanoma in this patient population is increasing. In 2014, the American Cancer Society estimated 310 cases of malignant melanoma in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, making it the 8th most prevalent cancer in adolescents. Based on US data for pediatric patients aged 0 to 19 years (2006-2010), melanoma was reported to be more common in girls and non-Hispanic whites. For pediatric cases diagnosed in 2003-2009, the 5-year observed survival rate was 95%, an increase from 83% in 1975-1979. These findings serve as a reminder for practitioners to encourage young patients to practice good sun protection habits. Even if patients are careful, melanomas do occur in childhood and early diagnosis is key.

The ABCDE—asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter, evolving—criteria have been used for melanoma screening in adults and may be helpful in detecting pediatric melanoma. However, Silverberg and McCuaig proposed a mnemonic specifically for screening children called the CUP criteria. Because melanomas of childhood do not necessarily arise in a preexisting nevus, the CUP criteria take into account melanomas that arise de novo and may present histologically as spitzoid neoplasms. The atypical presentation of melanomas in childhood includes color uniformity (pink/red), ulceration and upward thickening, and pyogenic granuloma–like lesions and pop-up of new lesions.

For more information on practice modifications from these screening criteria for pediatric melanoma, read Silverberg and McCuaig’s Cutis article “Melanoma in Childhood: Changing Our Mind-set.”

It is typically perceived that cutaneous malignancies in childhood and adolescence are uncommon, but the incidence of melanoma in this patient population is increasing. In 2014, the American Cancer Society estimated 310 cases of malignant melanoma in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, making it the 8th most prevalent cancer in adolescents. Based on US data for pediatric patients aged 0 to 19 years (2006-2010), melanoma was reported to be more common in girls and non-Hispanic whites. For pediatric cases diagnosed in 2003-2009, the 5-year observed survival rate was 95%, an increase from 83% in 1975-1979. These findings serve as a reminder for practitioners to encourage young patients to practice good sun protection habits. Even if patients are careful, melanomas do occur in childhood and early diagnosis is key.

The ABCDE—asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter, evolving—criteria have been used for melanoma screening in adults and may be helpful in detecting pediatric melanoma. However, Silverberg and McCuaig proposed a mnemonic specifically for screening children called the CUP criteria. Because melanomas of childhood do not necessarily arise in a preexisting nevus, the CUP criteria take into account melanomas that arise de novo and may present histologically as spitzoid neoplasms. The atypical presentation of melanomas in childhood includes color uniformity (pink/red), ulceration and upward thickening, and pyogenic granuloma–like lesions and pop-up of new lesions.

For more information on practice modifications from these screening criteria for pediatric melanoma, read Silverberg and McCuaig’s Cutis article “Melanoma in Childhood: Changing Our Mind-set.”

Product News: 02 2015

Bellafill

Suneva Medical, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the polymethylmethacrylate collagen filler Bellafill for the correction of moderate to severe, atrophic, distensible facial acne scars on the cheek in patients older than 21 years. Bellafill adds volume to the skin to lift and smooth out pitted acne scars to the level of the surrounding skin. Bellafill also is indicated for correction of nasolabial folds. For more information, visit www.bellafill.com.

Benzac

Galderma Laboratories, LP, launches Benzac Acne Solutions, an over-the-counter 3-step acne regimen consisting of a skin balancing foaming cleanser, intensive spot treatment, and blemish clearing hydrator. In addition to salicylic acid, Benzac also contains Kakadu plum (an antioxidant) to brighten the skin, lemon myrtle (an astringent) to reduce excess oil, and zinc to act as a barrier against skin moisture loss. Benzac contains pharmaceutical-grade East Indian sandalwood oil to calm and soothe the skin. For more information, visit www.benzac.com.

The Promius Promise App

Promius Pharma, LLC, marketers of Zenatane (isotretinoin capsules), launches The Promius Promise App designed to help educate and guide patients through the iPLEDGE program from the first visit to the last visit. The app is free for patients who have received a Zenatane prescription through The Promius Promise program. Patients can easily find important information, which may help with treatment compliance. The app will be useful for young adults and teenagers as well as their parents. For more information, visit www.zenatane.com/toolkit/Promius-Promise-Enrollment-Form.php.

Soolantra

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Soolantra Cream 1% for the once-daily treatment of inflammatory lesions of rosacea. Ivermectin, the active ingredient in Soolantra, has both anti-inflammatory and antiparasitic activity. The basis for the cream formulation is Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream. Soolantra offers patients improvement as early as week 2 of treatment. For more information, visit www.soolantra.com/hcp.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Bellafill

Suneva Medical, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the polymethylmethacrylate collagen filler Bellafill for the correction of moderate to severe, atrophic, distensible facial acne scars on the cheek in patients older than 21 years. Bellafill adds volume to the skin to lift and smooth out pitted acne scars to the level of the surrounding skin. Bellafill also is indicated for correction of nasolabial folds. For more information, visit www.bellafill.com.

Benzac

Galderma Laboratories, LP, launches Benzac Acne Solutions, an over-the-counter 3-step acne regimen consisting of a skin balancing foaming cleanser, intensive spot treatment, and blemish clearing hydrator. In addition to salicylic acid, Benzac also contains Kakadu plum (an antioxidant) to brighten the skin, lemon myrtle (an astringent) to reduce excess oil, and zinc to act as a barrier against skin moisture loss. Benzac contains pharmaceutical-grade East Indian sandalwood oil to calm and soothe the skin. For more information, visit www.benzac.com.

The Promius Promise App

Promius Pharma, LLC, marketers of Zenatane (isotretinoin capsules), launches The Promius Promise App designed to help educate and guide patients through the iPLEDGE program from the first visit to the last visit. The app is free for patients who have received a Zenatane prescription through The Promius Promise program. Patients can easily find important information, which may help with treatment compliance. The app will be useful for young adults and teenagers as well as their parents. For more information, visit www.zenatane.com/toolkit/Promius-Promise-Enrollment-Form.php.

Soolantra

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Soolantra Cream 1% for the once-daily treatment of inflammatory lesions of rosacea. Ivermectin, the active ingredient in Soolantra, has both anti-inflammatory and antiparasitic activity. The basis for the cream formulation is Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream. Soolantra offers patients improvement as early as week 2 of treatment. For more information, visit www.soolantra.com/hcp.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Bellafill

Suneva Medical, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of the polymethylmethacrylate collagen filler Bellafill for the correction of moderate to severe, atrophic, distensible facial acne scars on the cheek in patients older than 21 years. Bellafill adds volume to the skin to lift and smooth out pitted acne scars to the level of the surrounding skin. Bellafill also is indicated for correction of nasolabial folds. For more information, visit www.bellafill.com.

Benzac

Galderma Laboratories, LP, launches Benzac Acne Solutions, an over-the-counter 3-step acne regimen consisting of a skin balancing foaming cleanser, intensive spot treatment, and blemish clearing hydrator. In addition to salicylic acid, Benzac also contains Kakadu plum (an antioxidant) to brighten the skin, lemon myrtle (an astringent) to reduce excess oil, and zinc to act as a barrier against skin moisture loss. Benzac contains pharmaceutical-grade East Indian sandalwood oil to calm and soothe the skin. For more information, visit www.benzac.com.

The Promius Promise App

Promius Pharma, LLC, marketers of Zenatane (isotretinoin capsules), launches The Promius Promise App designed to help educate and guide patients through the iPLEDGE program from the first visit to the last visit. The app is free for patients who have received a Zenatane prescription through The Promius Promise program. Patients can easily find important information, which may help with treatment compliance. The app will be useful for young adults and teenagers as well as their parents. For more information, visit www.zenatane.com/toolkit/Promius-Promise-Enrollment-Form.php.

Soolantra

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Soolantra Cream 1% for the once-daily treatment of inflammatory lesions of rosacea. Ivermectin, the active ingredient in Soolantra, has both anti-inflammatory and antiparasitic activity. The basis for the cream formulation is Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream. Soolantra offers patients improvement as early as week 2 of treatment. For more information, visit www.soolantra.com/hcp.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

A Primer to Natural Hair Care Practices in Black Patients

The phenomenon of natural (nonchemically treated) hair in individuals of African and Afro-Caribbean descent is sweeping across the United States. The ideals of beauty among this patient population have shifted from a relaxed, straightened, noncurly look to a more natural curly and/or kinky appearance. The discussion on natural hair versus straight hair has been brought to the mainstream by films such as Good Hair (2009). Furthermore, major hair care companies have increased their marketing of natural hair products to address the needs of these patients.

Popular traumatic hair care practices such as chemical relaxation and thermal straightening may lead to hair damage. Although the role of hair care practices in various scalp and hair disorders is ambiguous, traumatic practices commonly are performed by patients who are diagnosed with dermatologic conditions such as scarring alopecia.1 Alopecia is the fourth most common dermatologic diagnosis in black patients.2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is the most common form of scarring alopecia in this patient population3 and has been associated with traumatic hair care practices. As a result, many patients have switched to natural hairstyles that are less traumatic and damaging, often due to recommendations by dermatologists.

As the US population continues to become more diverse, dermatologists will be faced with many questions regarding hair disease and natural hair care in patients with skin of color. A basic understanding of hair care practices among black individuals is important to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of hair shaft and scalp disorders.4 When patients switch to natural hairstyles, are dermatologists prepared to answer questions that may arise during this process? This article will familiarize dermatologists with basic hair care terminology and general recommendations they can make to black patients who are transitioning to natural hairstyles.

Characteristics of Hair in the Skin of Color Population

A basic understanding of the structural properties of hair is fundamental. Human hair is categorized into 3 groups: Asian, Caucasian, and African.5 African hair typically is curly and, depending on the degree of the curl, is more susceptible to damage due to increased mechanical fragility. It also has a tendency to form knots and fissures along the hair shaft, which causes additional fracturing with simple manipulation. African hair grows more slowly than Asian and Caucasian hair, which can be discouraging to patients. It also has a lower water concentration and does not become coated with sebum as naturally as straightened hair.5 A simplified explanation of these characteristics can help patients understand how to proceed in managing and styling their natural hair.

As physicians, it is important for us to treat any underlying conditions related to the hair and scalp in black patients. Common dermatologic conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis, lupus, folliculitis, and alopecia can affect patients’ hair health. In addition to traumatic hair care practices, inflammation secondary to bacterial infections can contribute to the onset of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.6 Therefore, a detailed history and physical examination are needed to evaluate the etiology of associated symptoms. Treatment of these associated symptoms will aid in the overall care of patients.

Transitioning to Natural Hairstyles

Following evaluation and treatment of any hair or scalp conditions, how can dermatologists help black patients transition to natural hairstyles? The term transition refers to the process of switching from a chemically relaxed or thermally straightened hairstyle to a natural hairstyle. Dermatologists must understand the common terminology used to describe natural hair practices in this patient population.

There are several methods patients can use to transition from chemically treated hairstyles to natural hairstyles. Patients may consider the option of the “big chop,” or cutting off all chemically treated hair. This option typically leaves women with very short hairstyles down to the new growth, or hair that has grown since the last chemical relaxer. Other commonly used methods during the transition phase include protective styling (eg, braids, weaves, extensions) or simply growing out the chemically treated hair.

Protective styling methods such as braids, weaves, and extensions allow hair to be easily styled while the chemically treated hair grows out over time.7 Typically, protective styles may be worn for weeks to months, allowing hair growth without hair breakage and shedding. Hair weaving is a practice that incorporates artificial (synthetic) or human hair into one’s natural scalp hair.8 There are various techniques to extend hair including clip-in extensions, hair bonding and fusion with adhesives, sewing hair into braided hair, or the application of single strands of hair into a cap made of nylon mesh known as a lace front. Braided styles, weaves, and hair extensions cannot be washed as often as natural hair, but it is important to remind patients to replenish moisture as often as possible. Moisturizing or greasing the exposed scalp and proximal hair shafts can assist with water retention. It is imperative to inform patients that overuse of tight braids and glues for weaves and extensions may further damage the hair and scalp. Some of the natural ingredients commonly used in moisturizers include olive oil, jojoba oil, coconut oil, castor oil, and glycerin. These products can commonly cause pomade acne, which should be recognized and treated by dermatologists. Furthermore, long weaves and extensions can put excess weight on natural hair causing breakage. To prevent breakage, wearing an updo (a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward) can reduce the heavy strain on the hair.

Dermatologists should remind patients who wish to grow out chemically treated hair to frequently moisturize the hair and scalp as well as to avoid trauma to prevent hair breakage. As the natural hair grows out, the patient will experience varying hair textures from the natural curly hair to the previously processed straightened hair; as a result, the hair may tangle and become damaged. Manual detangling and detangling conditioners can help prevent damage. Patients should be advised to detangle the hair in sections first with the fingers, then with a wide-tooth comb working retrograde from the hair end to the roots.

Frequent hair trimming, ranging from every 4 to 6 weeks to every 2 to 4 months, should be recommended to patients who are experiencing breakage or wish to prevent damage. Trimming damaged hair can relieve excess weight on the natural hair and remove split ends, which promotes hair growth. Braiding and other lengthening techniques can prevent the hair from curling upon itself or tangling, causing less kinking and thereby decreasing the need for trimming.7 Wearing bonnets, using satin pillowcases, and wearing protective hairstyles while sleeping also can decrease hair breakage and hair loss. A commonly used hairstyle to protect the hair while sleeping is called “pineappling,” which is used to preserve and protect curls. This technique is described as gathering the hair in a high but loose ponytail at the top of the head. For patients with straightened hair, wrapping the hair underneath a bonnet or satin scarf while sleeping can prevent damage.

Managing Natural Hairstyles

An important factor in the management of natural hairstyles is the retention of hair moisture, as there is less water content in African hair compared to other hair types.5 Overuse of heat and harsh shampoos can strip moisture from the hair. Similar to patients with atopic dermatitis who should restore and maintain the skin barrier to prevent transepidermal water loss, it is important to remind patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using products and styling practices that may further deplete water content in the hair. Moisture is crucial to healthy hair.

A common culprit in shampoos that leads to hair dryness is sodium lauryl sulfate/sodium laureth sulfate, a detergent/surfactant used as a foaming agent. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a potent degreaser that binds dirt and excess product on the hair and scalp. It also dissolves oil in the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.

Patients with natural hairstyles commonly use sulfate-free shampoos to prevent stripping the hair of its moisture and natural oils. Another method used to prevent hair dryness is co-washing, or washing the hair with a conditioner. Co-washing can effectively cleanse the hair while maintaining moisture. The use of cationic ingredients in conditioners aids in sealing moisture within the hair shaft. Hair consists of the negatively charged protein keratin, which binds to cationic surfactants in conditioners.9 The hydrophobic ends of the surfactant prevent the substance from being rinsed out and act to restore the hair barrier.

Silicone is another important ingredient in hair care products. In patients with natural hair, there are varying views on the use of products containing silicone. Silicones are added to products designed to coat the hair, adding shine, retaining moisture, and providing thermal protection. Silicones are used to provide “slip.” Slip is a term that is commonly used among patients with natural hair to describe how slippery a product is and how easily the product will help comb or detangle the hair. There are 2 basic types of silicones: water insoluble and water soluble. Water-insoluble silicones traditionally build up on the hair and require surfactant-containing shampoos to becompletely removed. Residue buildup on the hair weighs the hair down and causes damage. In contrast, water-soluble silicones do not build up and typically do not cause damage.

Silicones with the prefixes PEG- or PPG- typically are water soluble and will not build up on the hair. Dimethicone copolyol and lauryl methicone copolyol are other water-soluble silicones. In general, water-soluble silicones provide moisturizing properties without leaving residue. Other silicones such as amodimethicone and cyclomethicone are not water soluble but have properties that prevent buildup.

It is common practice for patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using water-insoluble silicones. As dermatologists, we can recommend silicone-free conditioners or conditioners containing water-soluble silicones to prevent hair dehydration and subsequent breakage. It may be advantageous to have patients try various products to determine which ones work best for their hair.

More Resources for Patients

Dermatologists have extensive knowledge of the pathophysiology of skin, hair, and nail diseases; however, despite our vast knowledge, we also need to recognize our limits. In addition to increasing your own knowledge of natural hair care practices to help your patients, it is important to recommend that your patients search for additional resources to aid in their transition to natural hairstyles. Natural hairstylists can be great resources for patients to help with hair management. In the current digital age, there also are thousands of blogs and social media forums dedicated to the topic of natural hair care. Advising patients to consult natural hair care resources can be beneficial, but as hair specialists, it also is important for us to dispel any false information that our patients may receive. As physicians, it is essential not only to manage patients who present to our offices with conditions resulting from damaging hair practices but also to help prevent such conditions from occurring. Although there may not be an overwhelming amount of evidence-based medical research to guide our decisions, we also can learn from the thousands of patients who have articulated their stories and experiences. Through observing and listening to our patients, we can incorporate this new knowledge in the management of our patients.

1. Shah SK, Alexis AF. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: retrospective chart review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:212-222.

2. Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

3. Uhlenhake EE, Mehregan DM. Prospective histologic examinations in patients who practice traumatic hairstyling [published online ahead of print March 3, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1506-1512.

4. Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108.

5. Kelly AP, Taylor S, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

6. Kyei A, Bergfeld WF, Piliang M, et al. Medical and environmental risk factors for the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a population study [published online ahead of print April 11, 2011]. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:909-914.

7. Walton N, Carter ET. Better Than Good Hair: The Curly Girl Guide to Healthy, Gorgeous Natural Hair! New York, NY: Amistad; 2013.

8. Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

9. Cruz CF, Fernandes MM, Gomes AC, et al. Keratins and lipids in ethnic hair [published online ahead of print January 24, 2013]. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35:244-249.

The phenomenon of natural (nonchemically treated) hair in individuals of African and Afro-Caribbean descent is sweeping across the United States. The ideals of beauty among this patient population have shifted from a relaxed, straightened, noncurly look to a more natural curly and/or kinky appearance. The discussion on natural hair versus straight hair has been brought to the mainstream by films such as Good Hair (2009). Furthermore, major hair care companies have increased their marketing of natural hair products to address the needs of these patients.

Popular traumatic hair care practices such as chemical relaxation and thermal straightening may lead to hair damage. Although the role of hair care practices in various scalp and hair disorders is ambiguous, traumatic practices commonly are performed by patients who are diagnosed with dermatologic conditions such as scarring alopecia.1 Alopecia is the fourth most common dermatologic diagnosis in black patients.2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is the most common form of scarring alopecia in this patient population3 and has been associated with traumatic hair care practices. As a result, many patients have switched to natural hairstyles that are less traumatic and damaging, often due to recommendations by dermatologists.

As the US population continues to become more diverse, dermatologists will be faced with many questions regarding hair disease and natural hair care in patients with skin of color. A basic understanding of hair care practices among black individuals is important to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of hair shaft and scalp disorders.4 When patients switch to natural hairstyles, are dermatologists prepared to answer questions that may arise during this process? This article will familiarize dermatologists with basic hair care terminology and general recommendations they can make to black patients who are transitioning to natural hairstyles.

Characteristics of Hair in the Skin of Color Population

A basic understanding of the structural properties of hair is fundamental. Human hair is categorized into 3 groups: Asian, Caucasian, and African.5 African hair typically is curly and, depending on the degree of the curl, is more susceptible to damage due to increased mechanical fragility. It also has a tendency to form knots and fissures along the hair shaft, which causes additional fracturing with simple manipulation. African hair grows more slowly than Asian and Caucasian hair, which can be discouraging to patients. It also has a lower water concentration and does not become coated with sebum as naturally as straightened hair.5 A simplified explanation of these characteristics can help patients understand how to proceed in managing and styling their natural hair.

As physicians, it is important for us to treat any underlying conditions related to the hair and scalp in black patients. Common dermatologic conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis, lupus, folliculitis, and alopecia can affect patients’ hair health. In addition to traumatic hair care practices, inflammation secondary to bacterial infections can contribute to the onset of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.6 Therefore, a detailed history and physical examination are needed to evaluate the etiology of associated symptoms. Treatment of these associated symptoms will aid in the overall care of patients.

Transitioning to Natural Hairstyles

Following evaluation and treatment of any hair or scalp conditions, how can dermatologists help black patients transition to natural hairstyles? The term transition refers to the process of switching from a chemically relaxed or thermally straightened hairstyle to a natural hairstyle. Dermatologists must understand the common terminology used to describe natural hair practices in this patient population.

There are several methods patients can use to transition from chemically treated hairstyles to natural hairstyles. Patients may consider the option of the “big chop,” or cutting off all chemically treated hair. This option typically leaves women with very short hairstyles down to the new growth, or hair that has grown since the last chemical relaxer. Other commonly used methods during the transition phase include protective styling (eg, braids, weaves, extensions) or simply growing out the chemically treated hair.

Protective styling methods such as braids, weaves, and extensions allow hair to be easily styled while the chemically treated hair grows out over time.7 Typically, protective styles may be worn for weeks to months, allowing hair growth without hair breakage and shedding. Hair weaving is a practice that incorporates artificial (synthetic) or human hair into one’s natural scalp hair.8 There are various techniques to extend hair including clip-in extensions, hair bonding and fusion with adhesives, sewing hair into braided hair, or the application of single strands of hair into a cap made of nylon mesh known as a lace front. Braided styles, weaves, and hair extensions cannot be washed as often as natural hair, but it is important to remind patients to replenish moisture as often as possible. Moisturizing or greasing the exposed scalp and proximal hair shafts can assist with water retention. It is imperative to inform patients that overuse of tight braids and glues for weaves and extensions may further damage the hair and scalp. Some of the natural ingredients commonly used in moisturizers include olive oil, jojoba oil, coconut oil, castor oil, and glycerin. These products can commonly cause pomade acne, which should be recognized and treated by dermatologists. Furthermore, long weaves and extensions can put excess weight on natural hair causing breakage. To prevent breakage, wearing an updo (a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward) can reduce the heavy strain on the hair.

Dermatologists should remind patients who wish to grow out chemically treated hair to frequently moisturize the hair and scalp as well as to avoid trauma to prevent hair breakage. As the natural hair grows out, the patient will experience varying hair textures from the natural curly hair to the previously processed straightened hair; as a result, the hair may tangle and become damaged. Manual detangling and detangling conditioners can help prevent damage. Patients should be advised to detangle the hair in sections first with the fingers, then with a wide-tooth comb working retrograde from the hair end to the roots.

Frequent hair trimming, ranging from every 4 to 6 weeks to every 2 to 4 months, should be recommended to patients who are experiencing breakage or wish to prevent damage. Trimming damaged hair can relieve excess weight on the natural hair and remove split ends, which promotes hair growth. Braiding and other lengthening techniques can prevent the hair from curling upon itself or tangling, causing less kinking and thereby decreasing the need for trimming.7 Wearing bonnets, using satin pillowcases, and wearing protective hairstyles while sleeping also can decrease hair breakage and hair loss. A commonly used hairstyle to protect the hair while sleeping is called “pineappling,” which is used to preserve and protect curls. This technique is described as gathering the hair in a high but loose ponytail at the top of the head. For patients with straightened hair, wrapping the hair underneath a bonnet or satin scarf while sleeping can prevent damage.

Managing Natural Hairstyles

An important factor in the management of natural hairstyles is the retention of hair moisture, as there is less water content in African hair compared to other hair types.5 Overuse of heat and harsh shampoos can strip moisture from the hair. Similar to patients with atopic dermatitis who should restore and maintain the skin barrier to prevent transepidermal water loss, it is important to remind patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using products and styling practices that may further deplete water content in the hair. Moisture is crucial to healthy hair.

A common culprit in shampoos that leads to hair dryness is sodium lauryl sulfate/sodium laureth sulfate, a detergent/surfactant used as a foaming agent. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a potent degreaser that binds dirt and excess product on the hair and scalp. It also dissolves oil in the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.

Patients with natural hairstyles commonly use sulfate-free shampoos to prevent stripping the hair of its moisture and natural oils. Another method used to prevent hair dryness is co-washing, or washing the hair with a conditioner. Co-washing can effectively cleanse the hair while maintaining moisture. The use of cationic ingredients in conditioners aids in sealing moisture within the hair shaft. Hair consists of the negatively charged protein keratin, which binds to cationic surfactants in conditioners.9 The hydrophobic ends of the surfactant prevent the substance from being rinsed out and act to restore the hair barrier.

Silicone is another important ingredient in hair care products. In patients with natural hair, there are varying views on the use of products containing silicone. Silicones are added to products designed to coat the hair, adding shine, retaining moisture, and providing thermal protection. Silicones are used to provide “slip.” Slip is a term that is commonly used among patients with natural hair to describe how slippery a product is and how easily the product will help comb or detangle the hair. There are 2 basic types of silicones: water insoluble and water soluble. Water-insoluble silicones traditionally build up on the hair and require surfactant-containing shampoos to becompletely removed. Residue buildup on the hair weighs the hair down and causes damage. In contrast, water-soluble silicones do not build up and typically do not cause damage.

Silicones with the prefixes PEG- or PPG- typically are water soluble and will not build up on the hair. Dimethicone copolyol and lauryl methicone copolyol are other water-soluble silicones. In general, water-soluble silicones provide moisturizing properties without leaving residue. Other silicones such as amodimethicone and cyclomethicone are not water soluble but have properties that prevent buildup.

It is common practice for patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using water-insoluble silicones. As dermatologists, we can recommend silicone-free conditioners or conditioners containing water-soluble silicones to prevent hair dehydration and subsequent breakage. It may be advantageous to have patients try various products to determine which ones work best for their hair.

More Resources for Patients

Dermatologists have extensive knowledge of the pathophysiology of skin, hair, and nail diseases; however, despite our vast knowledge, we also need to recognize our limits. In addition to increasing your own knowledge of natural hair care practices to help your patients, it is important to recommend that your patients search for additional resources to aid in their transition to natural hairstyles. Natural hairstylists can be great resources for patients to help with hair management. In the current digital age, there also are thousands of blogs and social media forums dedicated to the topic of natural hair care. Advising patients to consult natural hair care resources can be beneficial, but as hair specialists, it also is important for us to dispel any false information that our patients may receive. As physicians, it is essential not only to manage patients who present to our offices with conditions resulting from damaging hair practices but also to help prevent such conditions from occurring. Although there may not be an overwhelming amount of evidence-based medical research to guide our decisions, we also can learn from the thousands of patients who have articulated their stories and experiences. Through observing and listening to our patients, we can incorporate this new knowledge in the management of our patients.

The phenomenon of natural (nonchemically treated) hair in individuals of African and Afro-Caribbean descent is sweeping across the United States. The ideals of beauty among this patient population have shifted from a relaxed, straightened, noncurly look to a more natural curly and/or kinky appearance. The discussion on natural hair versus straight hair has been brought to the mainstream by films such as Good Hair (2009). Furthermore, major hair care companies have increased their marketing of natural hair products to address the needs of these patients.

Popular traumatic hair care practices such as chemical relaxation and thermal straightening may lead to hair damage. Although the role of hair care practices in various scalp and hair disorders is ambiguous, traumatic practices commonly are performed by patients who are diagnosed with dermatologic conditions such as scarring alopecia.1 Alopecia is the fourth most common dermatologic diagnosis in black patients.2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is the most common form of scarring alopecia in this patient population3 and has been associated with traumatic hair care practices. As a result, many patients have switched to natural hairstyles that are less traumatic and damaging, often due to recommendations by dermatologists.

As the US population continues to become more diverse, dermatologists will be faced with many questions regarding hair disease and natural hair care in patients with skin of color. A basic understanding of hair care practices among black individuals is important to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of hair shaft and scalp disorders.4 When patients switch to natural hairstyles, are dermatologists prepared to answer questions that may arise during this process? This article will familiarize dermatologists with basic hair care terminology and general recommendations they can make to black patients who are transitioning to natural hairstyles.

Characteristics of Hair in the Skin of Color Population

A basic understanding of the structural properties of hair is fundamental. Human hair is categorized into 3 groups: Asian, Caucasian, and African.5 African hair typically is curly and, depending on the degree of the curl, is more susceptible to damage due to increased mechanical fragility. It also has a tendency to form knots and fissures along the hair shaft, which causes additional fracturing with simple manipulation. African hair grows more slowly than Asian and Caucasian hair, which can be discouraging to patients. It also has a lower water concentration and does not become coated with sebum as naturally as straightened hair.5 A simplified explanation of these characteristics can help patients understand how to proceed in managing and styling their natural hair.

As physicians, it is important for us to treat any underlying conditions related to the hair and scalp in black patients. Common dermatologic conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis, lupus, folliculitis, and alopecia can affect patients’ hair health. In addition to traumatic hair care practices, inflammation secondary to bacterial infections can contribute to the onset of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.6 Therefore, a detailed history and physical examination are needed to evaluate the etiology of associated symptoms. Treatment of these associated symptoms will aid in the overall care of patients.

Transitioning to Natural Hairstyles

Following evaluation and treatment of any hair or scalp conditions, how can dermatologists help black patients transition to natural hairstyles? The term transition refers to the process of switching from a chemically relaxed or thermally straightened hairstyle to a natural hairstyle. Dermatologists must understand the common terminology used to describe natural hair practices in this patient population.

There are several methods patients can use to transition from chemically treated hairstyles to natural hairstyles. Patients may consider the option of the “big chop,” or cutting off all chemically treated hair. This option typically leaves women with very short hairstyles down to the new growth, or hair that has grown since the last chemical relaxer. Other commonly used methods during the transition phase include protective styling (eg, braids, weaves, extensions) or simply growing out the chemically treated hair.

Protective styling methods such as braids, weaves, and extensions allow hair to be easily styled while the chemically treated hair grows out over time.7 Typically, protective styles may be worn for weeks to months, allowing hair growth without hair breakage and shedding. Hair weaving is a practice that incorporates artificial (synthetic) or human hair into one’s natural scalp hair.8 There are various techniques to extend hair including clip-in extensions, hair bonding and fusion with adhesives, sewing hair into braided hair, or the application of single strands of hair into a cap made of nylon mesh known as a lace front. Braided styles, weaves, and hair extensions cannot be washed as often as natural hair, but it is important to remind patients to replenish moisture as often as possible. Moisturizing or greasing the exposed scalp and proximal hair shafts can assist with water retention. It is imperative to inform patients that overuse of tight braids and glues for weaves and extensions may further damage the hair and scalp. Some of the natural ingredients commonly used in moisturizers include olive oil, jojoba oil, coconut oil, castor oil, and glycerin. These products can commonly cause pomade acne, which should be recognized and treated by dermatologists. Furthermore, long weaves and extensions can put excess weight on natural hair causing breakage. To prevent breakage, wearing an updo (a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward) can reduce the heavy strain on the hair.

Dermatologists should remind patients who wish to grow out chemically treated hair to frequently moisturize the hair and scalp as well as to avoid trauma to prevent hair breakage. As the natural hair grows out, the patient will experience varying hair textures from the natural curly hair to the previously processed straightened hair; as a result, the hair may tangle and become damaged. Manual detangling and detangling conditioners can help prevent damage. Patients should be advised to detangle the hair in sections first with the fingers, then with a wide-tooth comb working retrograde from the hair end to the roots.

Frequent hair trimming, ranging from every 4 to 6 weeks to every 2 to 4 months, should be recommended to patients who are experiencing breakage or wish to prevent damage. Trimming damaged hair can relieve excess weight on the natural hair and remove split ends, which promotes hair growth. Braiding and other lengthening techniques can prevent the hair from curling upon itself or tangling, causing less kinking and thereby decreasing the need for trimming.7 Wearing bonnets, using satin pillowcases, and wearing protective hairstyles while sleeping also can decrease hair breakage and hair loss. A commonly used hairstyle to protect the hair while sleeping is called “pineappling,” which is used to preserve and protect curls. This technique is described as gathering the hair in a high but loose ponytail at the top of the head. For patients with straightened hair, wrapping the hair underneath a bonnet or satin scarf while sleeping can prevent damage.

Managing Natural Hairstyles

An important factor in the management of natural hairstyles is the retention of hair moisture, as there is less water content in African hair compared to other hair types.5 Overuse of heat and harsh shampoos can strip moisture from the hair. Similar to patients with atopic dermatitis who should restore and maintain the skin barrier to prevent transepidermal water loss, it is important to remind patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using products and styling practices that may further deplete water content in the hair. Moisture is crucial to healthy hair.

A common culprit in shampoos that leads to hair dryness is sodium lauryl sulfate/sodium laureth sulfate, a detergent/surfactant used as a foaming agent. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a potent degreaser that binds dirt and excess product on the hair and scalp. It also dissolves oil in the hair, causing additional dryness and breakage.

Patients with natural hairstyles commonly use sulfate-free shampoos to prevent stripping the hair of its moisture and natural oils. Another method used to prevent hair dryness is co-washing, or washing the hair with a conditioner. Co-washing can effectively cleanse the hair while maintaining moisture. The use of cationic ingredients in conditioners aids in sealing moisture within the hair shaft. Hair consists of the negatively charged protein keratin, which binds to cationic surfactants in conditioners.9 The hydrophobic ends of the surfactant prevent the substance from being rinsed out and act to restore the hair barrier.

Silicone is another important ingredient in hair care products. In patients with natural hair, there are varying views on the use of products containing silicone. Silicones are added to products designed to coat the hair, adding shine, retaining moisture, and providing thermal protection. Silicones are used to provide “slip.” Slip is a term that is commonly used among patients with natural hair to describe how slippery a product is and how easily the product will help comb or detangle the hair. There are 2 basic types of silicones: water insoluble and water soluble. Water-insoluble silicones traditionally build up on the hair and require surfactant-containing shampoos to becompletely removed. Residue buildup on the hair weighs the hair down and causes damage. In contrast, water-soluble silicones do not build up and typically do not cause damage.

Silicones with the prefixes PEG- or PPG- typically are water soluble and will not build up on the hair. Dimethicone copolyol and lauryl methicone copolyol are other water-soluble silicones. In general, water-soluble silicones provide moisturizing properties without leaving residue. Other silicones such as amodimethicone and cyclomethicone are not water soluble but have properties that prevent buildup.

It is common practice for patients with natural hairstyles to avoid using water-insoluble silicones. As dermatologists, we can recommend silicone-free conditioners or conditioners containing water-soluble silicones to prevent hair dehydration and subsequent breakage. It may be advantageous to have patients try various products to determine which ones work best for their hair.

More Resources for Patients

Dermatologists have extensive knowledge of the pathophysiology of skin, hair, and nail diseases; however, despite our vast knowledge, we also need to recognize our limits. In addition to increasing your own knowledge of natural hair care practices to help your patients, it is important to recommend that your patients search for additional resources to aid in their transition to natural hairstyles. Natural hairstylists can be great resources for patients to help with hair management. In the current digital age, there also are thousands of blogs and social media forums dedicated to the topic of natural hair care. Advising patients to consult natural hair care resources can be beneficial, but as hair specialists, it also is important for us to dispel any false information that our patients may receive. As physicians, it is essential not only to manage patients who present to our offices with conditions resulting from damaging hair practices but also to help prevent such conditions from occurring. Although there may not be an overwhelming amount of evidence-based medical research to guide our decisions, we also can learn from the thousands of patients who have articulated their stories and experiences. Through observing and listening to our patients, we can incorporate this new knowledge in the management of our patients.

1. Shah SK, Alexis AF. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: retrospective chart review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:212-222.

2. Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

3. Uhlenhake EE, Mehregan DM. Prospective histologic examinations in patients who practice traumatic hairstyling [published online ahead of print March 3, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1506-1512.

4. Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108.

5. Kelly AP, Taylor S, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

6. Kyei A, Bergfeld WF, Piliang M, et al. Medical and environmental risk factors for the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a population study [published online ahead of print April 11, 2011]. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:909-914.

7. Walton N, Carter ET. Better Than Good Hair: The Curly Girl Guide to Healthy, Gorgeous Natural Hair! New York, NY: Amistad; 2013.

8. Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

9. Cruz CF, Fernandes MM, Gomes AC, et al. Keratins and lipids in ethnic hair [published online ahead of print January 24, 2013]. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35:244-249.

1. Shah SK, Alexis AF. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: retrospective chart review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:212-222.

2. Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

3. Uhlenhake EE, Mehregan DM. Prospective histologic examinations in patients who practice traumatic hairstyling [published online ahead of print March 3, 2013]. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1506-1512.

4. Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African-American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108.

5. Kelly AP, Taylor S, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

6. Kyei A, Bergfeld WF, Piliang M, et al. Medical and environmental risk factors for the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a population study [published online ahead of print April 11, 2011]. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:909-914.

7. Walton N, Carter ET. Better Than Good Hair: The Curly Girl Guide to Healthy, Gorgeous Natural Hair! New York, NY: Amistad; 2013.

8. Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280-282, 285-289.

9. Cruz CF, Fernandes MM, Gomes AC, et al. Keratins and lipids in ethnic hair [published online ahead of print January 24, 2013]. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35:244-249.

Practice Points

- Many scalp and hair diseases in patients of African and Afro-Caribbean descent result from traumatic hairstyling practices and poor management. Proper care of these patients requires an understanding of hair variances and styling techniques across ethnicities.

- The use of protective hairstyles and adequate trimming can aid black patients in the transition to healthier natural hair.

- The use of natural oils for scalp health and the avoidance of products containing chemicals that remove moisture from the hair are helpful in maintaining healthy natural hair.

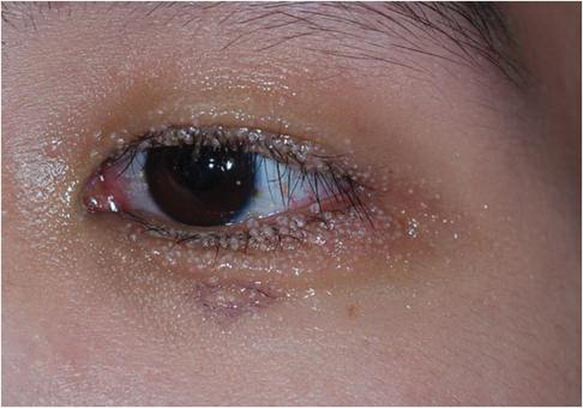

Multiple Papules on the Eyelid Margin

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

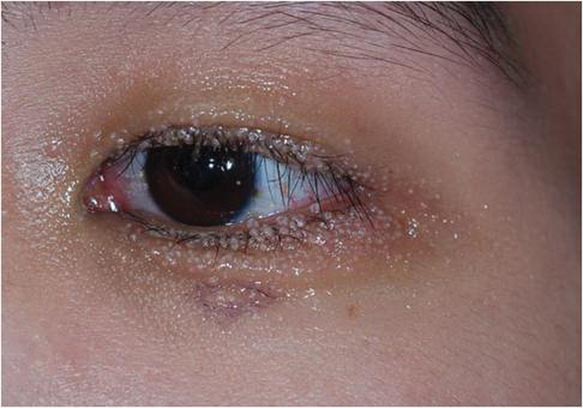

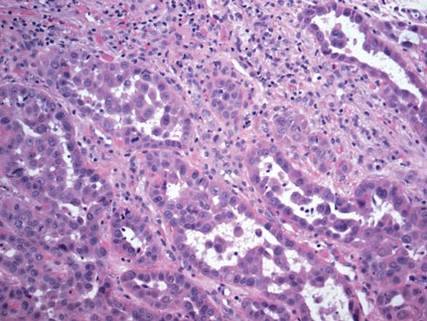

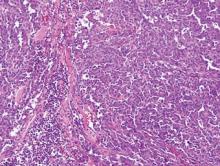

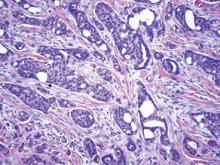

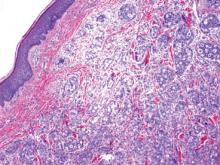

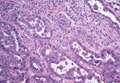

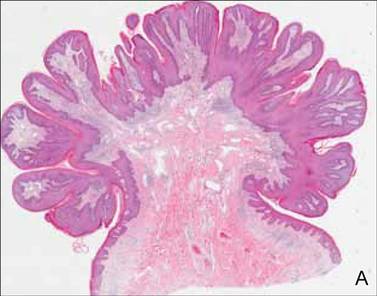

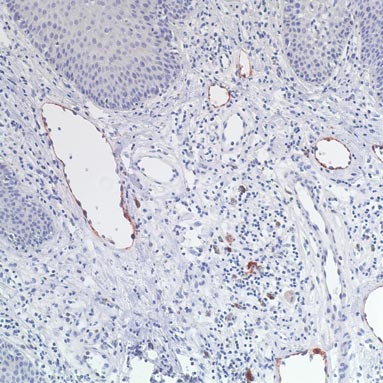

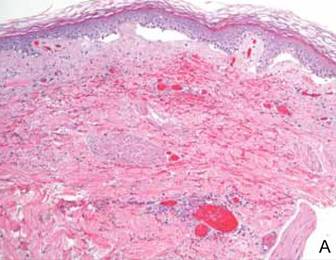

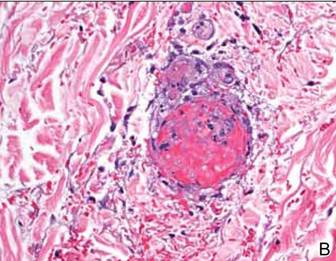

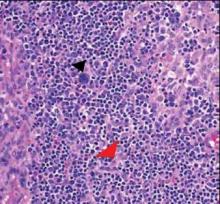

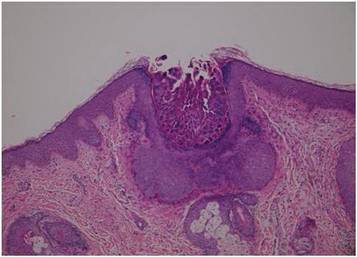

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

A 24-year-old man presented with multiple tiny papules over the left eyelid margin of 2 to 3 months’ duration. There were a couple of papules on the left upper eyelid initially, but they progressed to the upper and lower eyelid margin after scratching. On physical examination, multiple whitish to flesh-colored pearly papules measuring 1 to 2 mm were located on the left eyelid margin. Palpebral follicular conjunctivitis also was noted.

Modifier -25 Use in Dermatology

According to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), modifier -25 is to be used to identify “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service.”1 Modifier -25 frequently is integral to the description of patient visits in dermatology. Dermatologists use modifier -25 more than physicians of any other specialty, and in recent years, more than 50% of dermatology evaluation and management (E/M) visits have been appended with this modifier.

When patients present for assessment and management of various skin findings, a dermatologist may deem it appropriate to proceed with a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure at the same visit after obtaining the patient’s medical history, completing a review of systems, and conducting a clinical examination. Most commonly, a skin biopsy or destruction of a benign or malignant lesion may be performed, but other simple procedures also may be appropriate. The ability to assess and intervene during the same visit is optimal for patients who subsequently may require fewer follow-up visits and experience more immediate relief from their symptoms.

When E/M Cannot Be Billed Separately

Regulatory guidance from the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) dated January 2013 indicates that procedures with a global period of 90 days are major surgical procedures, and if an E/M service is performed on the same day as such a procedure to decide whether or not to perform that procedure, then the E/M service should be reported with modifier -57.2 On the other hand, CPT defines procedures with a 0- or 10-day global period as minor surgical procedures, and E/M services provided on the same day of service as these procedures are included in the procedure code and cannot be billed separately. For review, common dermatologic procedures with 0-day global periods include biopsies (CPT code 11000), shave removals (11300–11313), debridements (11000, 11011–11042), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311–17315); procedures with 10-day global periods include destructions (17000–17286), excisions (11400–11646), and repairs (12001–13153). If an E/M service is performed on the same day as one of these procedures to decide whether to proceed with the minor surgical procedure, this E/M service cannot be reported separately. Additionally, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M with such a minor procedure.

When E/M Can Be Billed Separately