User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Identification of Cutaneous Warts: Cryotherapy-Induced Acetowhitelike Epithelium

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

Subcutaneous Sarcoidosis on Ultrasonography

To the Editor:

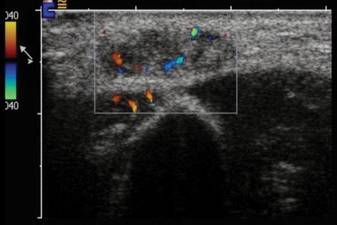

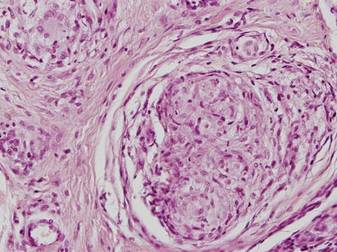

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

Inability to Grow Long Hair: A Presentation of Trichorrhexis Nodosa

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Sunscreens

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top sunscreens. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 40 Sunscreen Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It has broad UV spectrum coverage that blocks harmful UVA and UVB rays. It has a combination of both physical and chemical sun protection ingredients including Mexoryl SX.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Ultra Light Sunscreen Fluid

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Coppertone Sport AccuSpray

Bayer

“I use this personally and recommend it for my patients who exercise outdoors. It’s a photostable, broad-spectrum formula that is water resistant and offers durable protection.”

- EltaMD UV Clear Broad-Spectrum SPF 46, EltaMD UV Facial Broad-Spectrum SPF 30+

Swiss-American

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- EltaMD UV Daily Broad-Spectrum SPF 40

Swiss-American

"A perfect everyday sunscreen/moisturizer with broad-spectrum protection with the added benefits of an antioxidant (vitamin E) and hyaluronic acid to help reverse some evidence of photoaging. Additionally, the tinted version contains iron oxide, which previous research has shown to aid in treatment and prevention of melasma."—Michael Rains, Austin, Texas

- Physical Eye UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- Sensitive Skin Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 60+

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Super Fluid UV Defense SPF 50+

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Triple Protection Factor Broad Spectrum SPF 50+ Sunscreen Lotion With DNA Enzyme Complex + Antioxidants

Elizabeth Arden, Inc.

“I like this product because in addition to being an elegant, chemical-free sunscreen it has antioxidants and DNA repair enzymes. It not only protects the skin, but published research suggests it may help reverse some photodamage that has already occurred.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansers for rosacea patients, antiaging moisturizers, OTC acne preparations, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top sunscreens. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 40 Sunscreen Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It has broad UV spectrum coverage that blocks harmful UVA and UVB rays. It has a combination of both physical and chemical sun protection ingredients including Mexoryl SX.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Ultra Light Sunscreen Fluid

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Coppertone Sport AccuSpray

Bayer

“I use this personally and recommend it for my patients who exercise outdoors. It’s a photostable, broad-spectrum formula that is water resistant and offers durable protection.”

- EltaMD UV Clear Broad-Spectrum SPF 46, EltaMD UV Facial Broad-Spectrum SPF 30+

Swiss-American

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- EltaMD UV Daily Broad-Spectrum SPF 40

Swiss-American

"A perfect everyday sunscreen/moisturizer with broad-spectrum protection with the added benefits of an antioxidant (vitamin E) and hyaluronic acid to help reverse some evidence of photoaging. Additionally, the tinted version contains iron oxide, which previous research has shown to aid in treatment and prevention of melasma."—Michael Rains, Austin, Texas

- Physical Eye UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- Sensitive Skin Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 60+

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Super Fluid UV Defense SPF 50+

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Triple Protection Factor Broad Spectrum SPF 50+ Sunscreen Lotion With DNA Enzyme Complex + Antioxidants

Elizabeth Arden, Inc.

“I like this product because in addition to being an elegant, chemical-free sunscreen it has antioxidants and DNA repair enzymes. It not only protects the skin, but published research suggests it may help reverse some photodamage that has already occurred.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansers for rosacea patients, antiaging moisturizers, OTC acne preparations, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top sunscreens. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 40 Sunscreen Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It has broad UV spectrum coverage that blocks harmful UVA and UVB rays. It has a combination of both physical and chemical sun protection ingredients including Mexoryl SX.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Ultra Light Sunscreen Fluid

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Coppertone Sport AccuSpray

Bayer

“I use this personally and recommend it for my patients who exercise outdoors. It’s a photostable, broad-spectrum formula that is water resistant and offers durable protection.”

- EltaMD UV Clear Broad-Spectrum SPF 46, EltaMD UV Facial Broad-Spectrum SPF 30+

Swiss-American

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- EltaMD UV Daily Broad-Spectrum SPF 40

Swiss-American

"A perfect everyday sunscreen/moisturizer with broad-spectrum protection with the added benefits of an antioxidant (vitamin E) and hyaluronic acid to help reverse some evidence of photoaging. Additionally, the tinted version contains iron oxide, which previous research has shown to aid in treatment and prevention of melasma."—Michael Rains, Austin, Texas

- Physical Eye UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

Recommended by Julie Woodward, MD, Durham, North Carolina

- Sensitive Skin Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 60+

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Super Fluid UV Defense SPF 50+

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Triple Protection Factor Broad Spectrum SPF 50+ Sunscreen Lotion With DNA Enzyme Complex + Antioxidants

Elizabeth Arden, Inc.

“I like this product because in addition to being an elegant, chemical-free sunscreen it has antioxidants and DNA repair enzymes. It not only protects the skin, but published research suggests it may help reverse some photodamage that has already occurred.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansers for rosacea patients, antiaging moisturizers, OTC acne preparations, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Manage Your Dermatology Practice: Selecting Cosmetic Procedures to Offer in Your Practice

Dermatologists with a strictly medical or surgical practice may consider offering cosmetic procedures to their patients. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on how to market your practice as cosmetic by obtaining patient input, estimating start-up costs, and determining which procedures may benefit patients with medical conditions such as acne and rosacea.

Dermatologists with a strictly medical or surgical practice may consider offering cosmetic procedures to their patients. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on how to market your practice as cosmetic by obtaining patient input, estimating start-up costs, and determining which procedures may benefit patients with medical conditions such as acne and rosacea.

Dermatologists with a strictly medical or surgical practice may consider offering cosmetic procedures to their patients. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on how to market your practice as cosmetic by obtaining patient input, estimating start-up costs, and determining which procedures may benefit patients with medical conditions such as acne and rosacea.

Practice Question Answers: Sunscreen Agents

1. Which of the following sunscreen agents is most likely to cause a photoallergic reaction on the skin?

a. homosalate

b. oxybenzone

c. PABA

d. padimate O

e. zinc oxide

2. Which of the following sunscreen agents is least likely to cause an allergic reaction when applied?

a. ecamsule

b. octisalate

c. padimate A

d. titanium dioxide

e. trolamine salicylate

3. Of the following, which is/are considered to be an inorganic sunscreen agent?

a. PABA

b. titanium dioxide

c. zinc oxide

d. A, B, and C

e. B and C

4. Sunscreens containing PABA or one of its derivatives may cross-react with which of the following?

a. bananas

b. doxycycline

c. griseofulvin

d. naproxen

e. sulfonamides

5. Which of the following is/are used in sunscreens for UVA protection?

a. avobenzone

b. ecamsule

c. octisalate

d. A, B, and C

e. A and B

1. Which of the following sunscreen agents is most likely to cause a photoallergic reaction on the skin?

a. homosalate

b. oxybenzone

c. PABA

d. padimate O

e. zinc oxide

2. Which of the following sunscreen agents is least likely to cause an allergic reaction when applied?

a. ecamsule

b. octisalate

c. padimate A

d. titanium dioxide

e. trolamine salicylate

3. Of the following, which is/are considered to be an inorganic sunscreen agent?

a. PABA

b. titanium dioxide

c. zinc oxide

d. A, B, and C

e. B and C

4. Sunscreens containing PABA or one of its derivatives may cross-react with which of the following?

a. bananas

b. doxycycline

c. griseofulvin

d. naproxen

e. sulfonamides

5. Which of the following is/are used in sunscreens for UVA protection?

a. avobenzone

b. ecamsule

c. octisalate

d. A, B, and C

e. A and B

1. Which of the following sunscreen agents is most likely to cause a photoallergic reaction on the skin?

a. homosalate

b. oxybenzone

c. PABA

d. padimate O

e. zinc oxide

2. Which of the following sunscreen agents is least likely to cause an allergic reaction when applied?

a. ecamsule

b. octisalate

c. padimate A

d. titanium dioxide

e. trolamine salicylate

3. Of the following, which is/are considered to be an inorganic sunscreen agent?

a. PABA

b. titanium dioxide

c. zinc oxide

d. A, B, and C

e. B and C

4. Sunscreens containing PABA or one of its derivatives may cross-react with which of the following?

a. bananas

b. doxycycline

c. griseofulvin

d. naproxen

e. sulfonamides

5. Which of the following is/are used in sunscreens for UVA protection?

a. avobenzone

b. ecamsule

c. octisalate

d. A, B, and C

e. A and B

Sunscreen Agents

Perioral Rejuvenation

The perioral region is second to the periorbital area in making a person appear tired, sad, happy, or healthy. Although a lot of emphasis has been given to improving the periorbital area, the perioral region has received less attention. The mainstay of addressing the perioral region is using fillers, mainly synthetic ones, to smooth rhytides and restore lost volume. Skin resurfacing is a second-line approach, in part due to the required 5 to 7 days of recovery time to heal. However, as we have learned through many other procedures, it is wrong to make one modality your hammer and every patient your nail.

In an article published online on November 20, 2014, in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Penna et al conducted a morphometric review of 462 perioral photographs to come up with a 2-dimensional classification system to evaluate the perioral region. The classification was based on 2 qualities: lip shape and surface changes. Lip shape was classified as (1) short concave upper lip with 2 to 3 mm of upper incisors visible and prominent everted vermilion; (2) moderately elongated and straight upper lip with upper incisors at the lower border of the upper lip and mild degree of vermilion inversion; and (3) strongly elongated upper lip that forms a convex curve around the frontal teeth row with upper incisors that are not visible and vermilion is inverted. Lip surface was classified as (1) distinct philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll without static radial wrinkles, and minor dynamic radial wrinkles; (2) flattened philtral columns and Cupid’s bow, indistinct white roll, beginning static radial wrinkles, and strong dynamic radial wrinkles; and (3) invisible philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll, and considerable static radial wrinkles.

This scale was validated for objectivity, interevaluator reliability, intraevaluator reliability, and reproducibility by having 3 plastic surgeons evaluate perioral photographs of 42 female patients. The scale proved to be valid to a significant degree using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Based on this evaluation scale, one can evaluate the anatomic structure of the lip to decide if no treatment is needed, if synthetic or autologous fillers would suffice, or if a surgical lip-lift is required. Furthermore, surface changes can help determine if no treatment is needed, if skin resurfacing is indicated, or if both skin resurfacing and volumizing is required. The authors studied female subjects because they constitute the majority of patients seeking perioral rejuvenation.

What’s the issue?

Certainly the field of noninvasive cosmetic procedures continues to grow yearly; however, one must temper the enthusiasm of the patient at times so that he/she does not undergo excessive procedures and end up with unnatural results. Furthermore, one must not neglect the importance of artistry and proper patient evaluation in order to achieve a natural rejuvenated appearance. For example, relying solely on fillers to address perioral aging has resulted in an astonishing number of celebrities and patients walking around with an unnatural and distorted appearance. In many instances, this look may age a patient rather than rejuvenate him/her. Cosmetic dermatology is a balance between knowing when to treat, how much to treat, and when to effectively combine modalities to ensure the best outcome. This classification system will be useful for training residents and newly graduated dermatologists.

The perioral region is second to the periorbital area in making a person appear tired, sad, happy, or healthy. Although a lot of emphasis has been given to improving the periorbital area, the perioral region has received less attention. The mainstay of addressing the perioral region is using fillers, mainly synthetic ones, to smooth rhytides and restore lost volume. Skin resurfacing is a second-line approach, in part due to the required 5 to 7 days of recovery time to heal. However, as we have learned through many other procedures, it is wrong to make one modality your hammer and every patient your nail.

In an article published online on November 20, 2014, in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Penna et al conducted a morphometric review of 462 perioral photographs to come up with a 2-dimensional classification system to evaluate the perioral region. The classification was based on 2 qualities: lip shape and surface changes. Lip shape was classified as (1) short concave upper lip with 2 to 3 mm of upper incisors visible and prominent everted vermilion; (2) moderately elongated and straight upper lip with upper incisors at the lower border of the upper lip and mild degree of vermilion inversion; and (3) strongly elongated upper lip that forms a convex curve around the frontal teeth row with upper incisors that are not visible and vermilion is inverted. Lip surface was classified as (1) distinct philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll without static radial wrinkles, and minor dynamic radial wrinkles; (2) flattened philtral columns and Cupid’s bow, indistinct white roll, beginning static radial wrinkles, and strong dynamic radial wrinkles; and (3) invisible philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll, and considerable static radial wrinkles.

This scale was validated for objectivity, interevaluator reliability, intraevaluator reliability, and reproducibility by having 3 plastic surgeons evaluate perioral photographs of 42 female patients. The scale proved to be valid to a significant degree using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Based on this evaluation scale, one can evaluate the anatomic structure of the lip to decide if no treatment is needed, if synthetic or autologous fillers would suffice, or if a surgical lip-lift is required. Furthermore, surface changes can help determine if no treatment is needed, if skin resurfacing is indicated, or if both skin resurfacing and volumizing is required. The authors studied female subjects because they constitute the majority of patients seeking perioral rejuvenation.

What’s the issue?

Certainly the field of noninvasive cosmetic procedures continues to grow yearly; however, one must temper the enthusiasm of the patient at times so that he/she does not undergo excessive procedures and end up with unnatural results. Furthermore, one must not neglect the importance of artistry and proper patient evaluation in order to achieve a natural rejuvenated appearance. For example, relying solely on fillers to address perioral aging has resulted in an astonishing number of celebrities and patients walking around with an unnatural and distorted appearance. In many instances, this look may age a patient rather than rejuvenate him/her. Cosmetic dermatology is a balance between knowing when to treat, how much to treat, and when to effectively combine modalities to ensure the best outcome. This classification system will be useful for training residents and newly graduated dermatologists.

The perioral region is second to the periorbital area in making a person appear tired, sad, happy, or healthy. Although a lot of emphasis has been given to improving the periorbital area, the perioral region has received less attention. The mainstay of addressing the perioral region is using fillers, mainly synthetic ones, to smooth rhytides and restore lost volume. Skin resurfacing is a second-line approach, in part due to the required 5 to 7 days of recovery time to heal. However, as we have learned through many other procedures, it is wrong to make one modality your hammer and every patient your nail.

In an article published online on November 20, 2014, in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Penna et al conducted a morphometric review of 462 perioral photographs to come up with a 2-dimensional classification system to evaluate the perioral region. The classification was based on 2 qualities: lip shape and surface changes. Lip shape was classified as (1) short concave upper lip with 2 to 3 mm of upper incisors visible and prominent everted vermilion; (2) moderately elongated and straight upper lip with upper incisors at the lower border of the upper lip and mild degree of vermilion inversion; and (3) strongly elongated upper lip that forms a convex curve around the frontal teeth row with upper incisors that are not visible and vermilion is inverted. Lip surface was classified as (1) distinct philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll without static radial wrinkles, and minor dynamic radial wrinkles; (2) flattened philtral columns and Cupid’s bow, indistinct white roll, beginning static radial wrinkles, and strong dynamic radial wrinkles; and (3) invisible philtral columns, Cupid’s bow and white roll, and considerable static radial wrinkles.

This scale was validated for objectivity, interevaluator reliability, intraevaluator reliability, and reproducibility by having 3 plastic surgeons evaluate perioral photographs of 42 female patients. The scale proved to be valid to a significant degree using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Based on this evaluation scale, one can evaluate the anatomic structure of the lip to decide if no treatment is needed, if synthetic or autologous fillers would suffice, or if a surgical lip-lift is required. Furthermore, surface changes can help determine if no treatment is needed, if skin resurfacing is indicated, or if both skin resurfacing and volumizing is required. The authors studied female subjects because they constitute the majority of patients seeking perioral rejuvenation.

What’s the issue?

Certainly the field of noninvasive cosmetic procedures continues to grow yearly; however, one must temper the enthusiasm of the patient at times so that he/she does not undergo excessive procedures and end up with unnatural results. Furthermore, one must not neglect the importance of artistry and proper patient evaluation in order to achieve a natural rejuvenated appearance. For example, relying solely on fillers to address perioral aging has resulted in an astonishing number of celebrities and patients walking around with an unnatural and distorted appearance. In many instances, this look may age a patient rather than rejuvenate him/her. Cosmetic dermatology is a balance between knowing when to treat, how much to treat, and when to effectively combine modalities to ensure the best outcome. This classification system will be useful for training residents and newly graduated dermatologists.

Counting Costs

We are all aware of the rising costs of medical care, especially for complex diseases such as psoriasis. The total cost of psoriasis in the United States is unknown. Brezinski et al (JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593) sought to define the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. They argued that this information is needed to provide the foundation for research, advocacy, and educational efforts within the disease.

The authors searched PubMed and MEDLINE databases for economic investigations on the costs of adult psoriasis in the United States. The primary objective of the analysis was to provide a comprehensive analysis of the literature on the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. The direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs of psoriasis were reported based on this systematic literature review and adjusted to 2013 US dollars.

The direct costs included medical costs associated with (1) specialist medical evaluations, (2) hospitalization, (3) prescription medications, (4) phototherapy, (5) medication administration costs, (6) laboratory tests and monitoring studies, and (7) over-the-counter medications and self-care products. The indirect costs were determined by absenteeism and impaired work productivity. Intangible costs were calculated as a measure of the negative effect of psoriasis on quality of life. Finally, comorbidity costs measured the medical evaluations, treatment, and lab monitoring that were directly attributed to comorbid conditions associated with psoriasis.

An initial review of the literature generated 100 articles; 22 studies were included in the systematic review. The direct psoriasis costs ranged from $51.7 billion to $63.2 billion, the indirect costs ranged from $23.9 billion to $35.4 billion, and medical comorbidities were estimated to contribute $36.4 billion annually in 2013 US dollars. The annual cost of psoriasis in the United States amounted to approximately $112 billion in 2013.

The authors concluded that the economic burden of psoriasis was substantial and significant in the United States.

What’s the issue?

In the United States, the economic burden of psoriasis is substantial because this disease is associated with negative physical, psychiatric, and social consequences. In addition, treatment costs continue to rise. How will this analysis of cost influence your future management of psoriasis?

We are all aware of the rising costs of medical care, especially for complex diseases such as psoriasis. The total cost of psoriasis in the United States is unknown. Brezinski et al (JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593) sought to define the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. They argued that this information is needed to provide the foundation for research, advocacy, and educational efforts within the disease.

The authors searched PubMed and MEDLINE databases for economic investigations on the costs of adult psoriasis in the United States. The primary objective of the analysis was to provide a comprehensive analysis of the literature on the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. The direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs of psoriasis were reported based on this systematic literature review and adjusted to 2013 US dollars.