User login

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

Dermatopathology education, which comprises approximately 30% of the dermatology residency curriculum, is crucial for the holistic training of dermatology residents to diagnose and manage a range of dermatologic conditions.1 Additionally, dermatopathology is the topic of one of the 4 American Board of Dermatology CORE Exam modules, further highlighting the need for comprehensive education in this area. A variety of resources including virtual dermatopathology and conventional microscopy training currently are used in residency programs for dermatopathology education.2,3 Although used less frequently, social media platforms such as Instagram also are used to aid in dermatopathology education for a wider audience.4 Other online resources, including the American Society of Dermatopathology website (www.asdp.org) and DermpathAtlas.com, are excellent tools for medical students, residents, and fellows to develop their knowledge.5 While these resources are accessible, they must be directly sought out by the student and utilized on their own time. Additionally, if medical students do not have a strong understanding of the basics of dermatopathology, they may not have the foundation required to benefit from these resources.

Dermatopathology education is critical for the overall practice of dermatology, yet most dermatology residency programs may not be incorporating dermatopathology education early enough in training. One study evaluating the timing and length of dermatopathology education during residency reported that fewer than 40% (20/51) of dermatology residency programs allocate 3 or more weeks to dermatopathology education during the second postgraduate year.1 Despite Ackerman6 advocating for early dermatopathology exposure to best prepare medical students to recognize and manage certain dermatologic conditions, the majority of exposure still seems to occur during postgraduate year 4.1 Furthermore, current primary care residents feel that their medical school training did not sufficiently prepare them to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, with only 37% (93/252) reporting feeling adequately prepared.7,8 Medical students also reported a lack of confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, with 89% (72/81) reporting they felt neutral, slightly confident, or not at all confident when asked to diagnose skin lesions.9 In the same study, the average score was 46.6% (7/15 questions answered correctly) when 74 participants were assessed via a multiple choice quiz on dermatologic diagnosis and treatment, further demonstrating the lack of general dermatology comfort among medical students.9 This likely stems from limited dermatology curriculum in medical schools, demonstrating the need for further dermatology education as a whole in medical school.10

Ensuring robust dermatopathology education in medical school and the first year of dermatology residency has the potential to better prepare medical students for the transition into dermatology residency and clinical practice. We created an introductory dermatopathology lecture and presented it to medical students and first year dermatology residents to improve dermatopathology knowledge and confidence in learners early in their dermatology training.

Structure of the Lecture

Participants included first-year dermatology residents and fourth-year medical students rotating with the Wayne State University Department of Dermatology (Detroit, Michigan). The same facilitator (H.O.) taught each of the lectures, and all lectures were conducted via Zoom at the beginning of the month from May 2024 through November 2024. A total of 7 lectures were given. The lecture was formatted so that a histologic image was shown, then learners expressed their thoughts about what the image was showing before the answer was given. This format allowed participants to view the images on their own device screen and allowed the facilitator to annotate the images. The lecture was divided into 3 sections: (1) cell types and basic structures, (2) anatomic slides, and (3) common diagnoses. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Section 1: Cell Types and Basic Structures—The first section covered the fundamental cell types (neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, melanocytes, and eosinophils) along with glandular structures (apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous). The session was designed to follow a retention and allow learners to think through each slide. First, participants were shown histologic images of each cell type and were asked to identify what type of cell was being shown. On the following slide, key features of each cell type were highlighted. Next, participants similarly were shown images of the glandular structures followed by key features of each. The section concluded with a review of the layers of the skin (stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale). A histologic image was shown, and the facilitator discussed how to distinguish the layers.

Section 2: Anatomic Sites—This section focused on key pathologic features for differentiating body surfaces, including the scalp, face, eyelids, ears, areolae, palms and soles, and mucosae. Participants initially were shown an image of a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide from a specific body surface and then were asked to identify structures that may serve as a clue to the anatomic location. If the participants were not sure, they were given hints; for example, when participants were shown an image of the ear and were unsure of the location, the facilitator circled cartilage and asked them to identify the structure. In most cases, once participants named this structure, they were able to recognize that the location was the ear.

Section 3: Common Diagnoses—This section addressed frequently encountered diagnoses in dermatopathology, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, seborrheic keratosis, solar lentigo, melanocytic nevus, melanoma, verruca vulgaris, spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It followed the same format of the first section: participants were shown an hemotoxyllin and eosin–stained image and then were asked to discuss what the diagnosis could be and why. Hints were given if participants struggled to come up with the correct diagnosis. A few slides also were dedicated to distinguishing benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma.

Pretest and Posttest Results

Residents participated in the lecture as part of their first-year orientation, and medical students participated during their dermatology rotation. All participants were invited to complete a pretest and a posttest before and after the lecture, respectively. Both assessments were optional and anonymous. The pretest was completed electronically and consisted of 10 knowledge-based, multiple-choice questions that included a histopathologic image and asked, “What is the most likely diagnosis?,” “What is the predominant cell type?,” and “Where was this specimen taken from?” In addition to the knowledge-based questions, participants also were asked to rate their confidence in dermatopathology on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not confident at all) to 5 (extremely confident). Participants completed the entire pretest before any information on the topic was provided. After the lecture, participants were asked to complete a posttest identical to the pretest and to rate their confidence in dermatopathology again on the same scale. The posttest included an additional question asking participants to rate the helpfulness of the lecture on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not helpful at all) to 5 (extremely helpful). Participants completed the posttest within 48 hours of the lecture.

Overall, 15 learners participated in the pretest and 12 in the posttest. Of the 15 pretest participants, 3 were first-year residents and 12 were medical students. Similarly, in the posttest, 2 respondents were first-year residents and 10 were medical students. All responses contained complete pretests and posttests. The mean score on the pretest was 62%, whereas the mean score on the posttest was 75%. A paired t test indicated a statistically significant improvement (P=.017). In addition, the mean rating for confidence in dermatopathology knowledge before the lecture was 1.5 prior to the lecture and 2.6 after the lecture. A paired t test demonstrated statistical significance (P=.010). The mean rating of the helpfulness of the lecture was 4.67. The majority (91.7% [11/12]) of the participants gave a rating of 4 or 5.

Impact of the Lecture on Dermatopathology Knowledge

There is a gap in dermatopathology education early in medical training. Our introductory lecture led to higher post test scores and increased confidence in dermatopathology among medical students and dermatology residents, demonstrating the effectiveness of this kind of program in bridging this education gap. The majority of participants in our lecture said they found the session helpful. A previously published article called for early implementation of dermatology education as a whole in the medical curriculum due to lack of knowledge and confidence, and our introductory lecture may help to bridge this gap.8 Increasing dermatopathology content for medical students and first-year dermatology residents can expand knowledge, as shown by the increased scores on the posttest, and better supports learners transitioning to dermatology residency, where dermatopathology constitutes a large part of the overall curriculum.2 More comprehensive knowledge of dermatopathology early in dermatology training also may help to better prepare residents to accurately diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions.

Pretest scores showed that the average confidence rating in dermatopathology among participants in our lecture was 1.5, which is rather low. This is consistent with prior studies that have found that residents feel that medical school inadequately prepared them for dermatology residency.7,8 More than 87% (71/81) of medical students surveyed felt they received inadequate general dermatology training in medical school.9 This supports the proposed educational gap that is impacting confidence in overall dermatology knowledge, which includes dermatopathology. In our study, the average confidence rating increased by 1.1 points after the lecture, which was statistically significant (P=.010) and demonstrates that an introductory lecture serves as a feasible intervention to improve confidence in this area.

The feedback we received from participants in our lecture shows the benefits of an introductory interactive lecture with virtual dermatopathology images. Ngo et al2 highlighted how residents perceive virtual images to be superior to conventional microscopy for dermatopathology, which we utilized in our lecture. This method is not only cost effective but also provides a simple way for learners and facilitators to point out key findings on histopathology slides.2

Final Thoughts

Overall, implementing dermatopathology education early in training has a measurable impact on dermatopathology knowledge and confidence among medical students and first-year dermatology residents. An interactive lecture with virtual images similar to the one we describe here may better prepare learners for the transition to dermatology residency by addressing the educational gap in dermatopathology early in training.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826, vii.

- Ngo TB, Niu W, Fang Z, et al. Dermatology residents’ perspectives on virtual dermatopathology education. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51:530-537.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels J, Murphy MJ. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763-771.

- Hubbard G, Saal R, Wintringham J, et al. Utilizing Instagram as a novel method for dermatopathology instruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;49:89-91.

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14.

- Ackerman AB. Training residents in dermatopathology: why, when, where, and how. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(6 Pt 1):1104-1106.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.e1.

- Murase JE. Understanding the importance of dermatology training in undergraduate medical education. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:95-96.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Impact of an Introductory Dermatopathology Lecture on Medical Students and First-Year Dermatology Residents

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

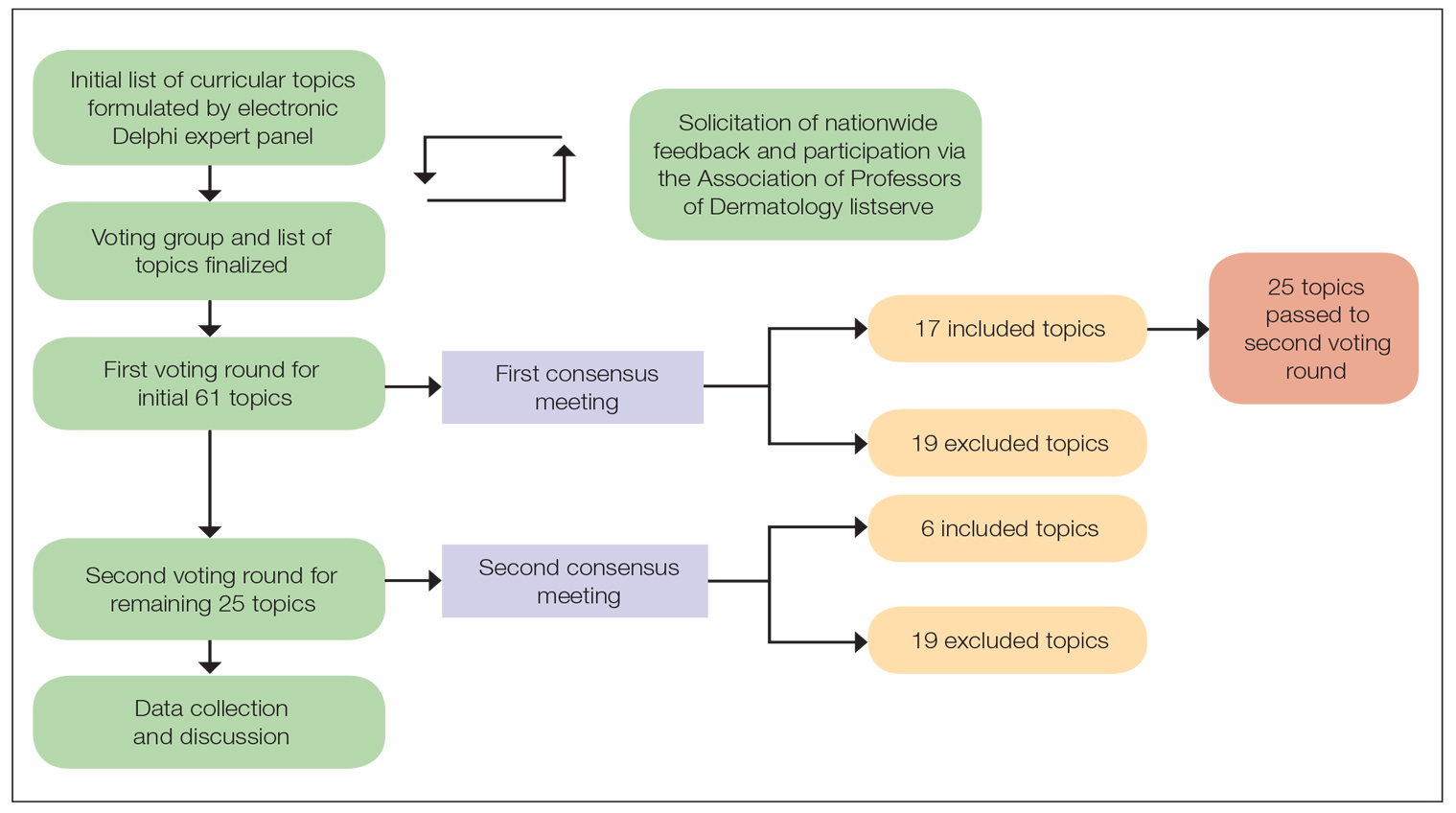

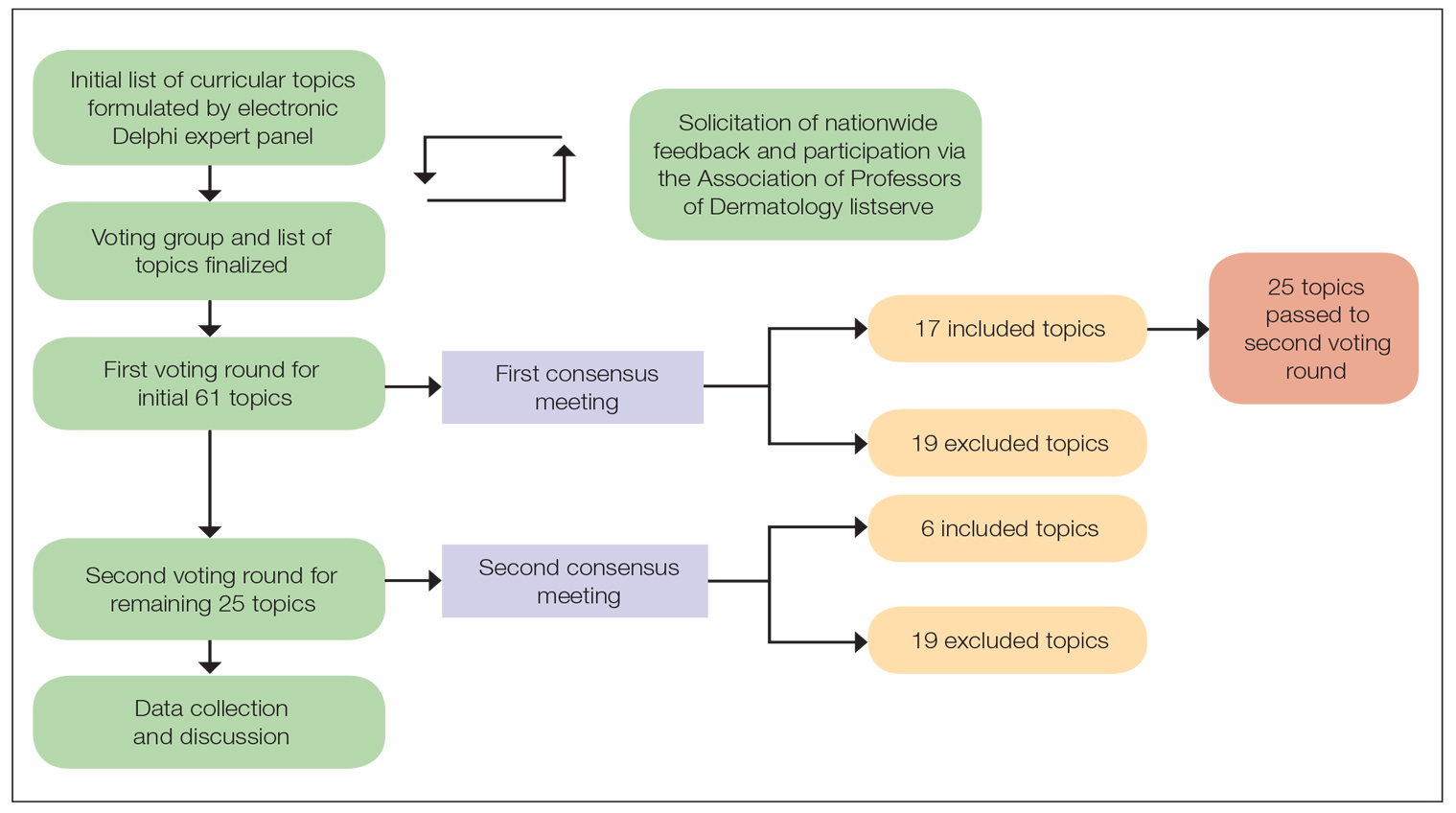

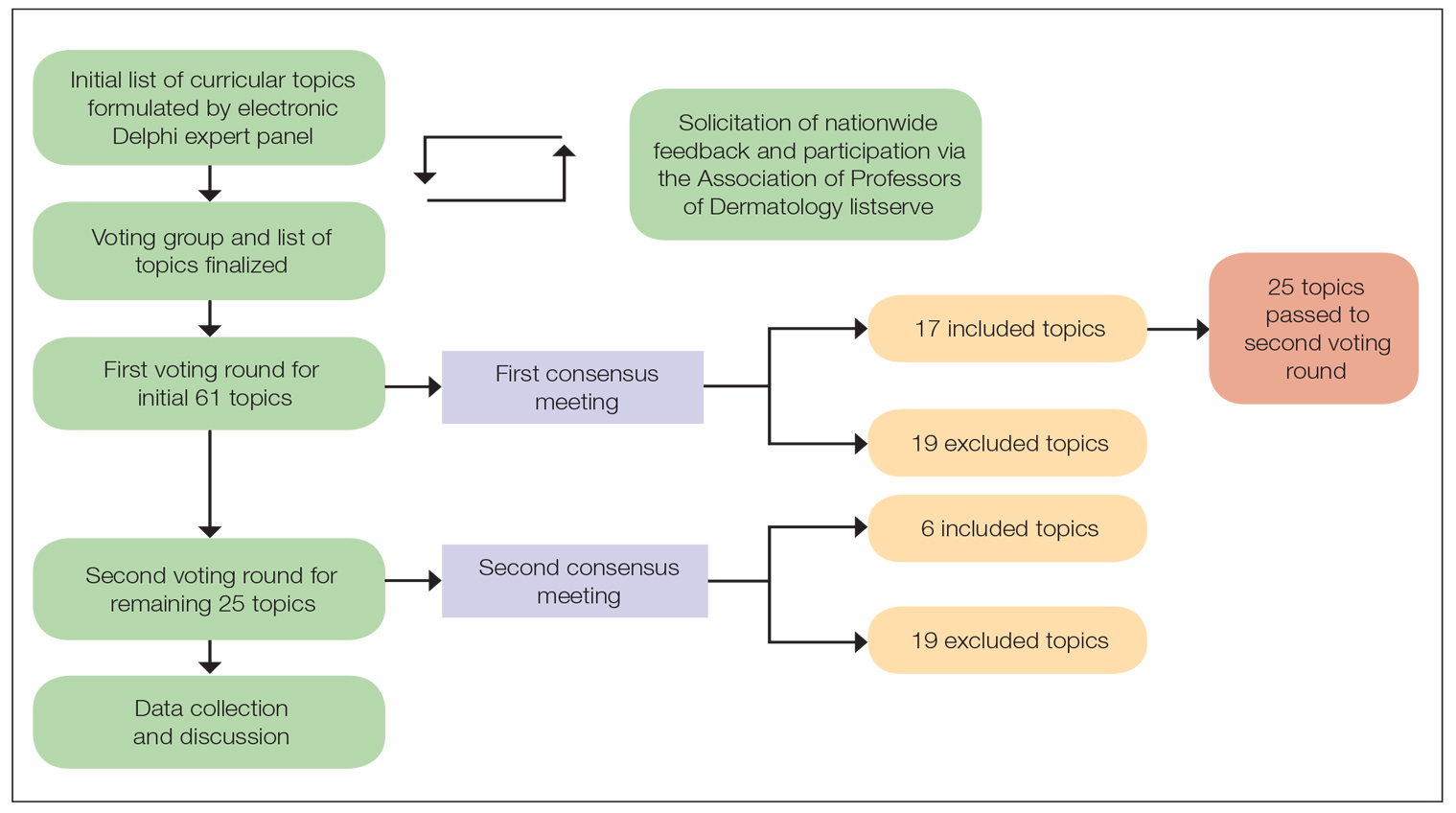

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821