User login

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

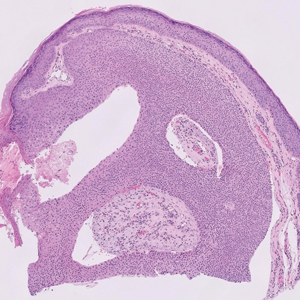

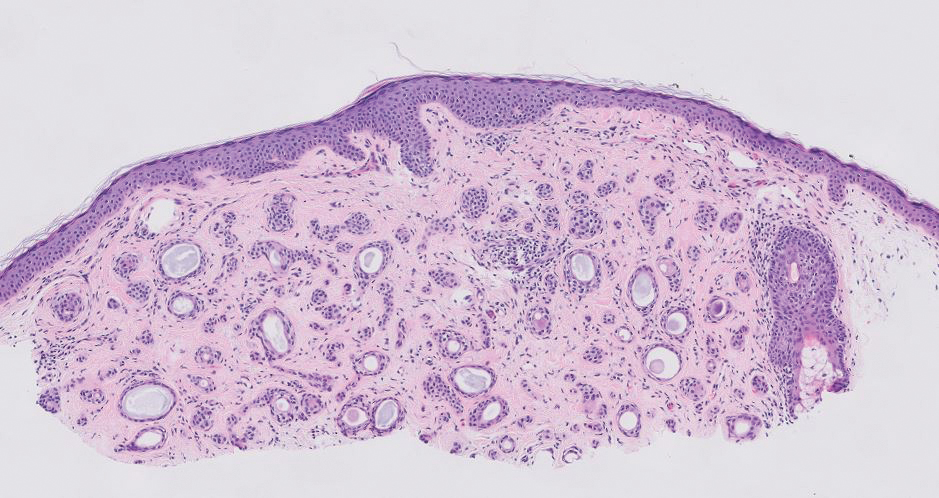

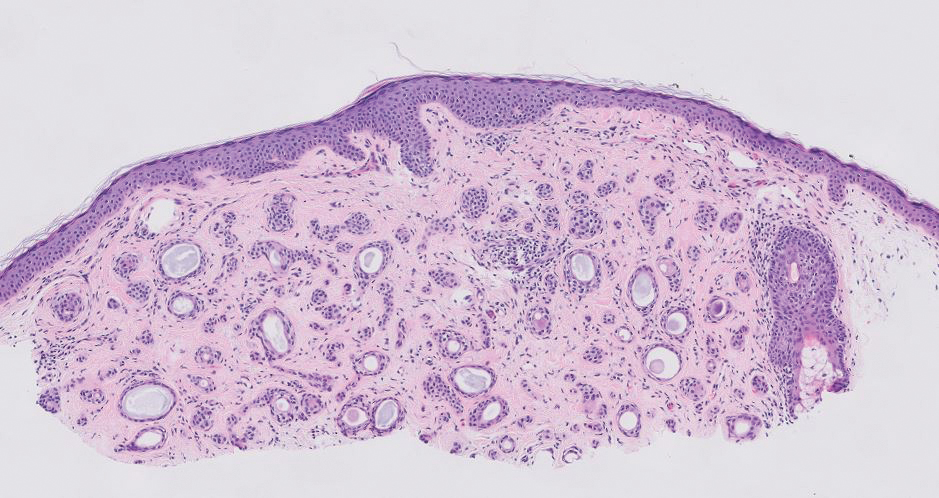

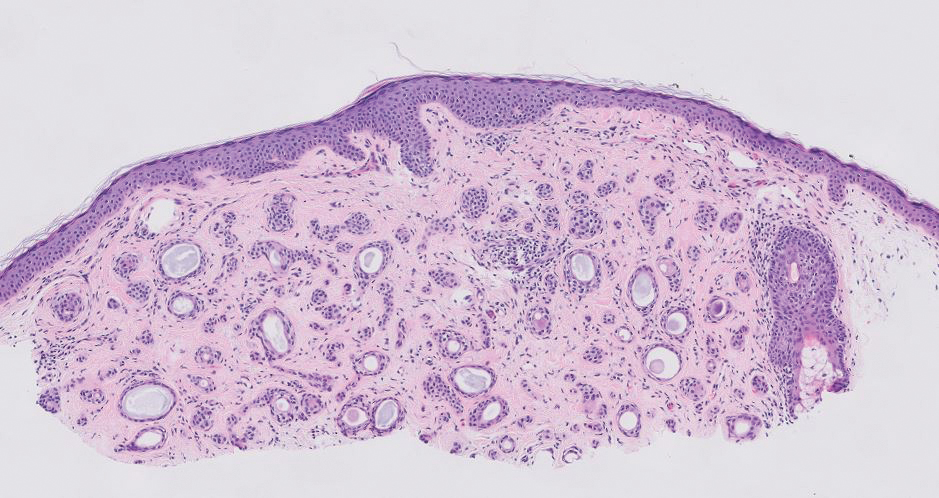

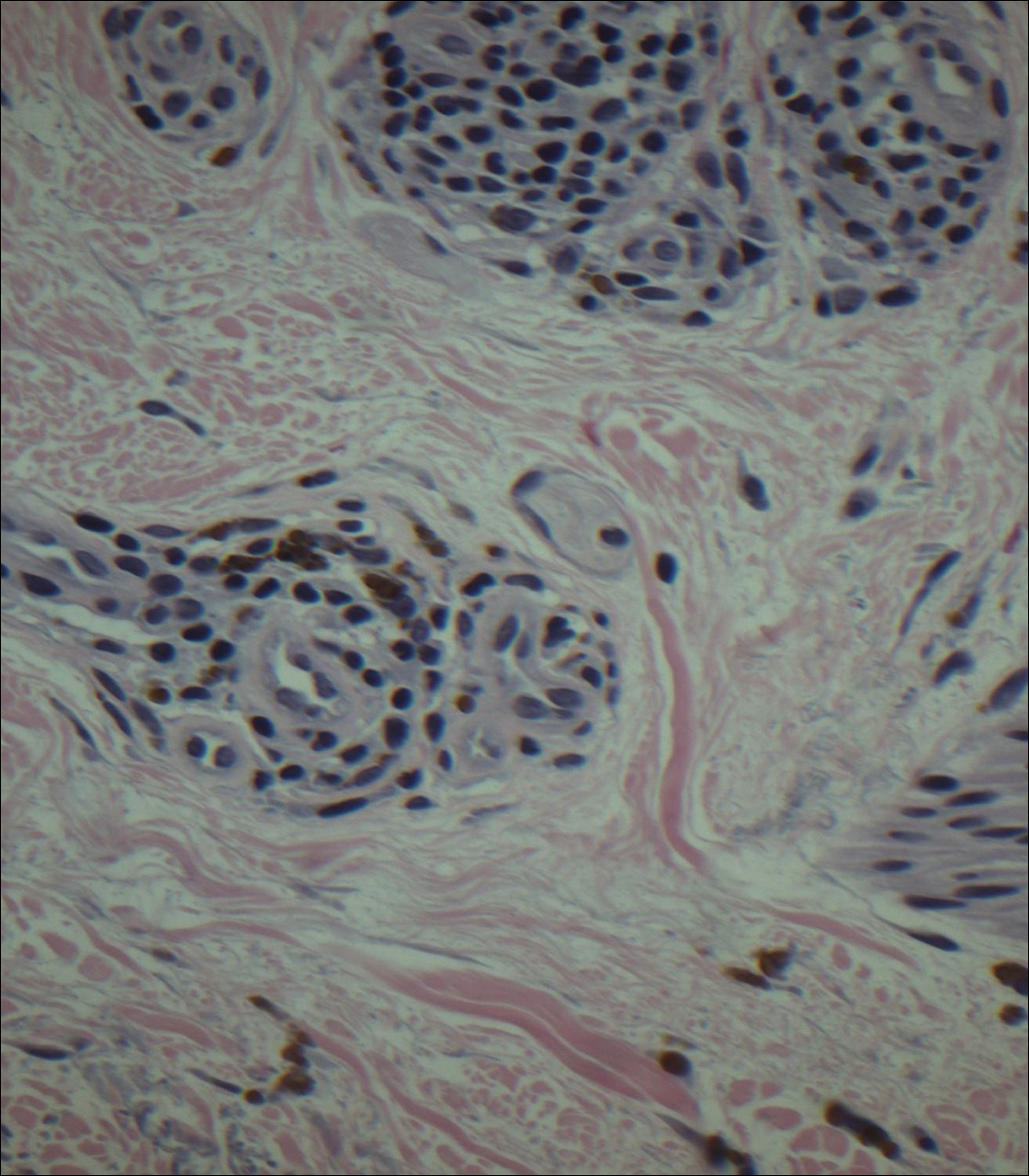

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

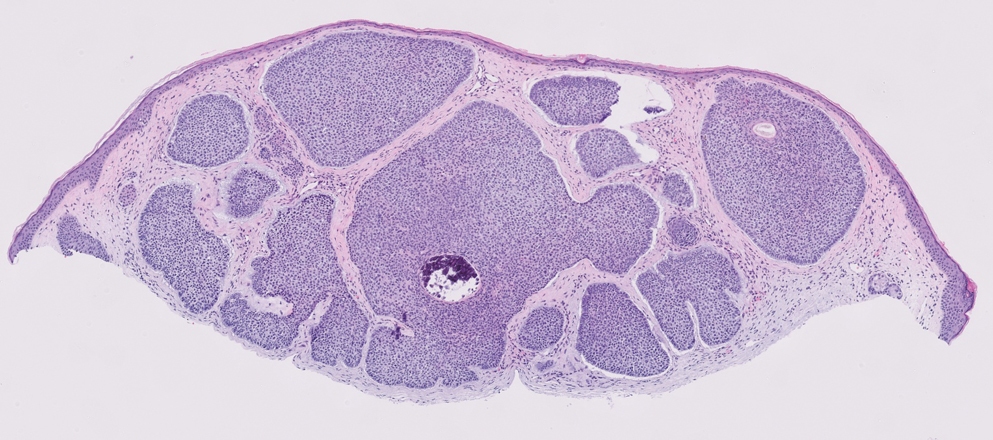

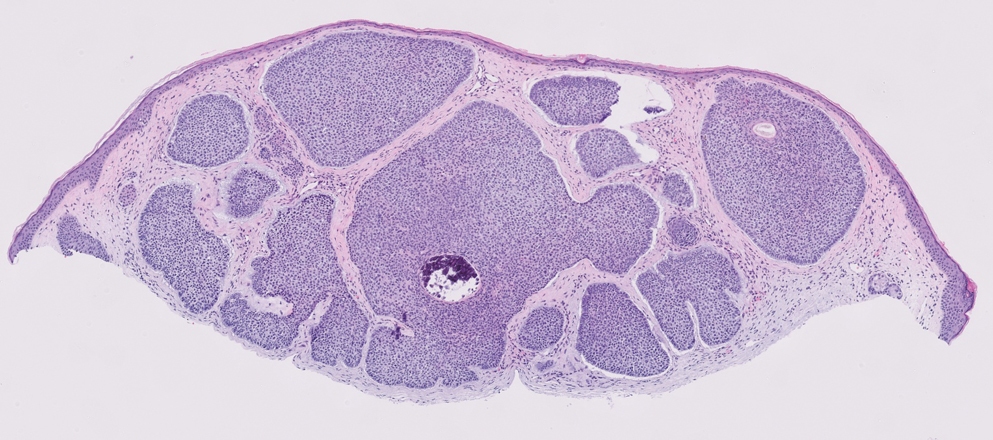

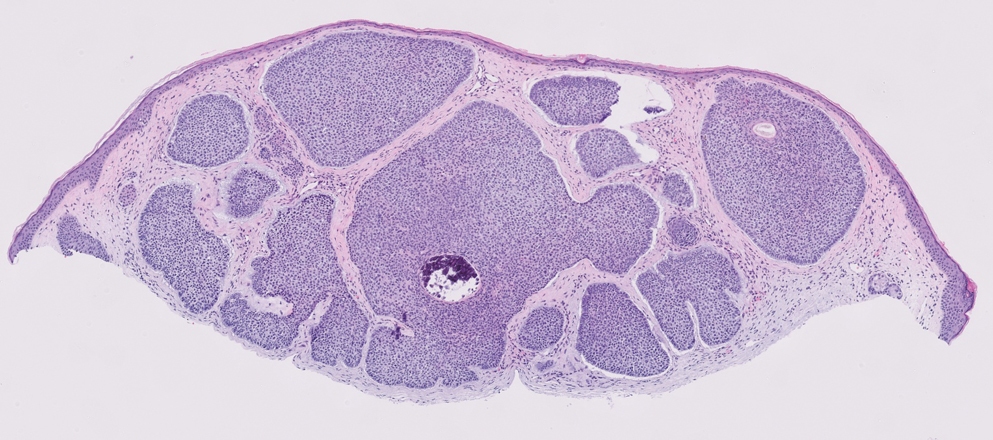

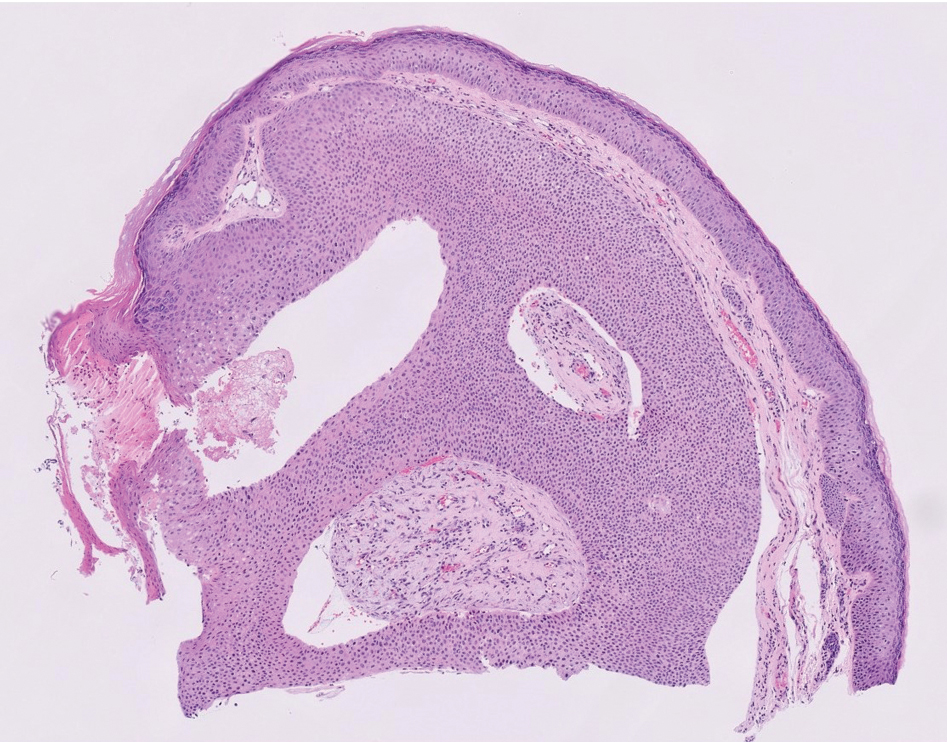

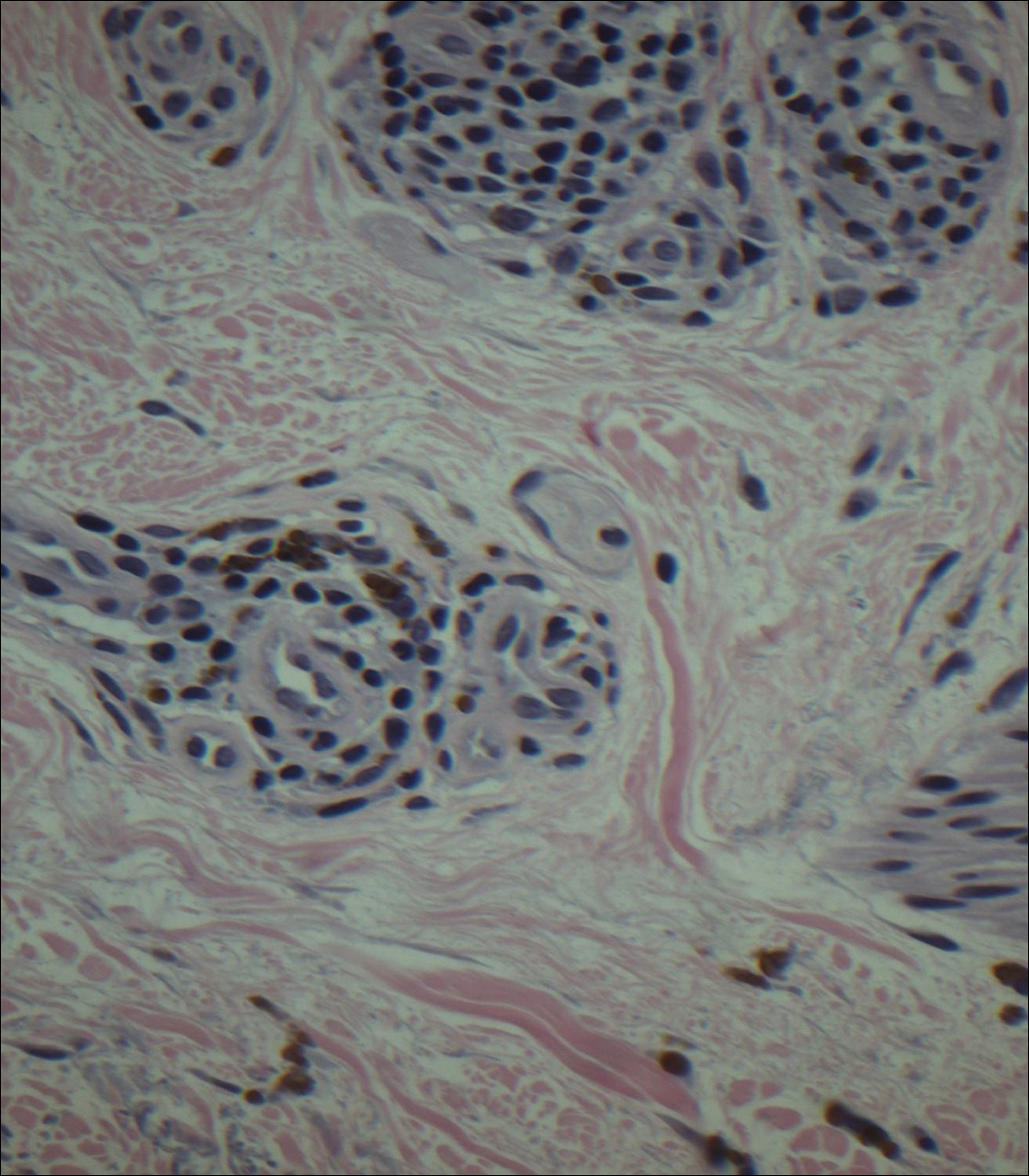

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

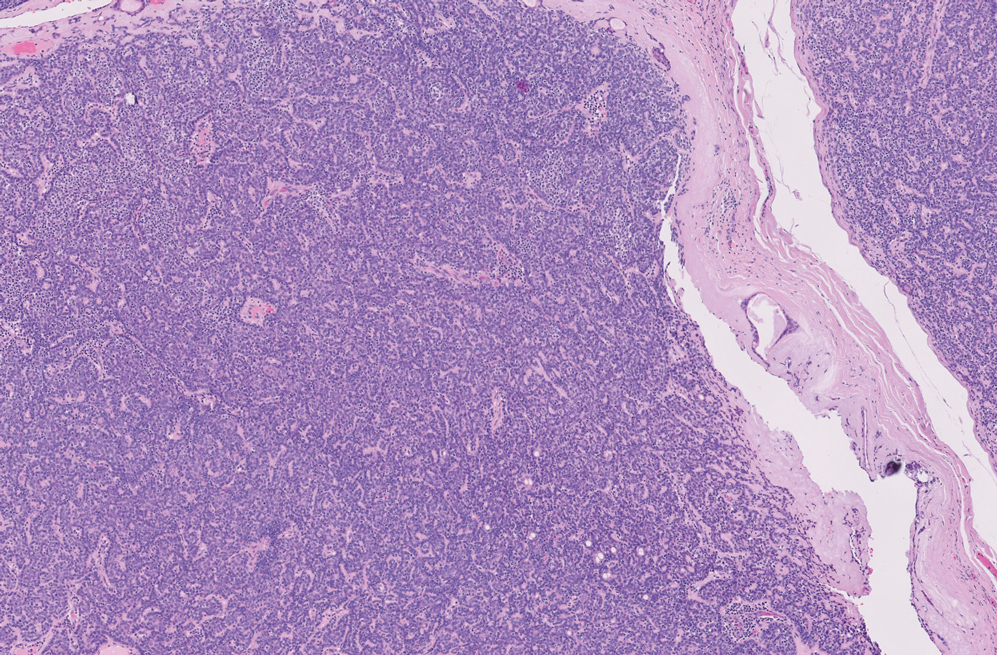

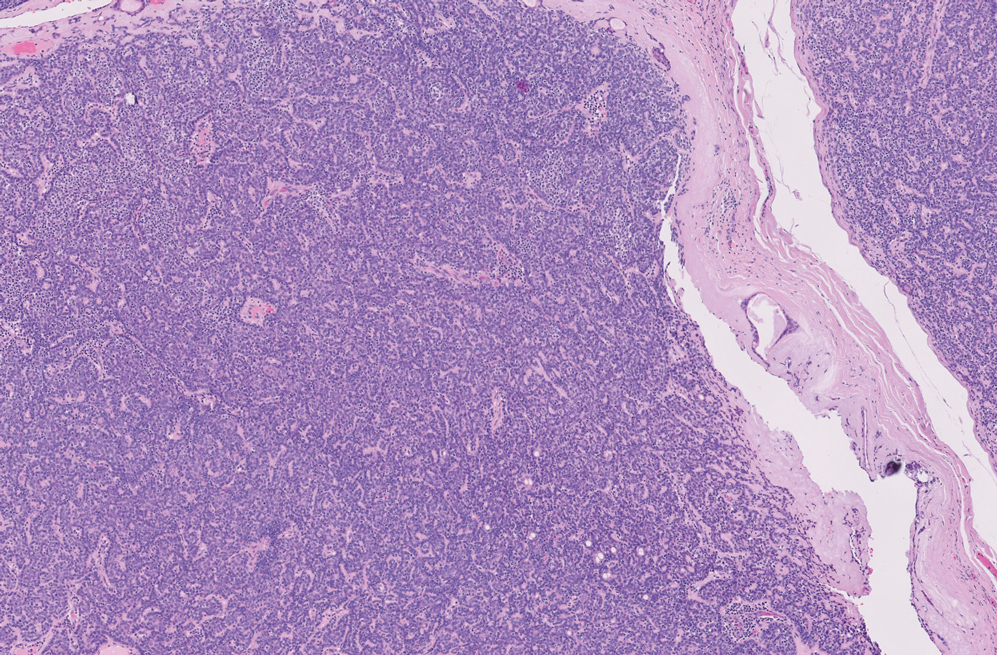

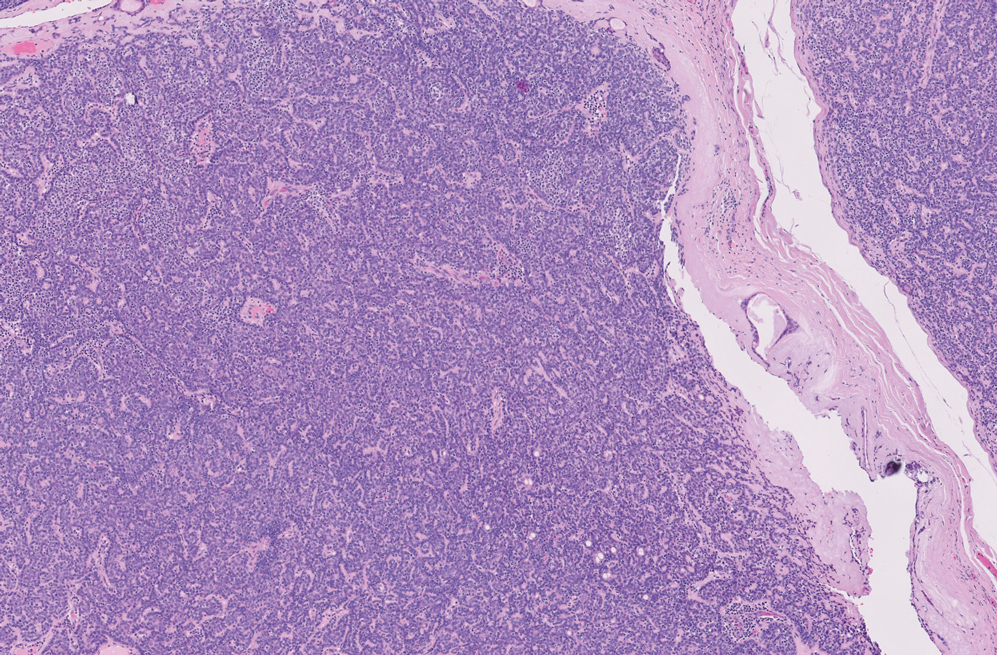

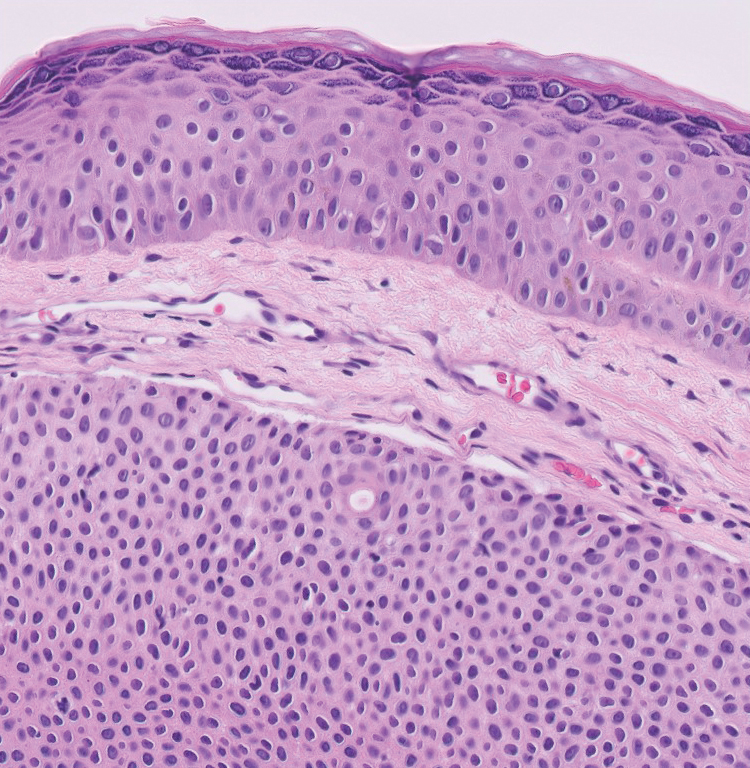

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

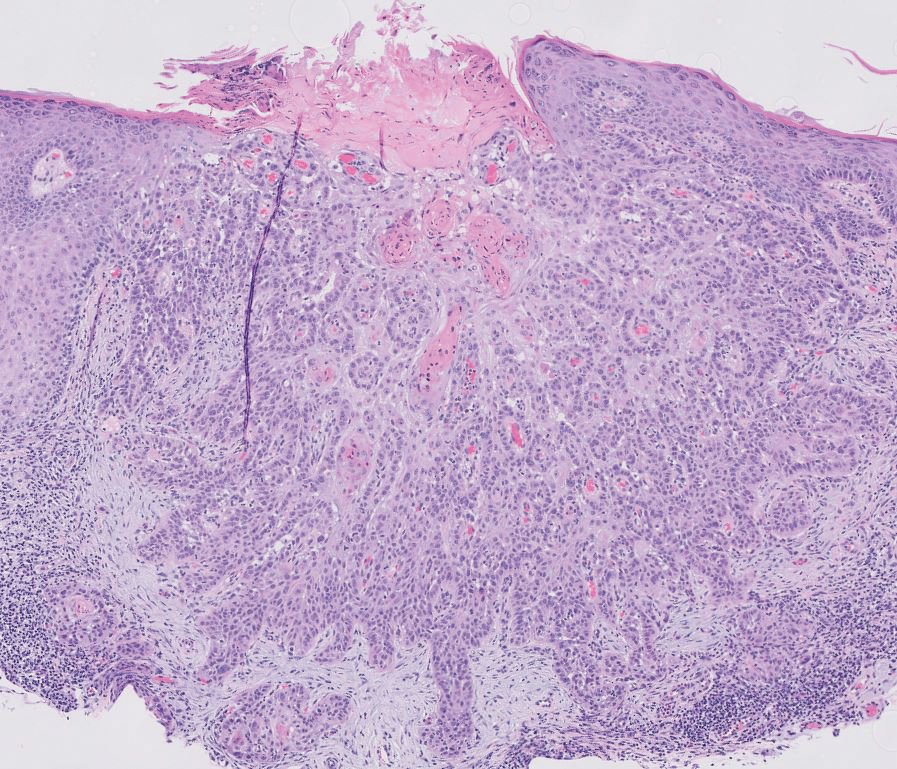

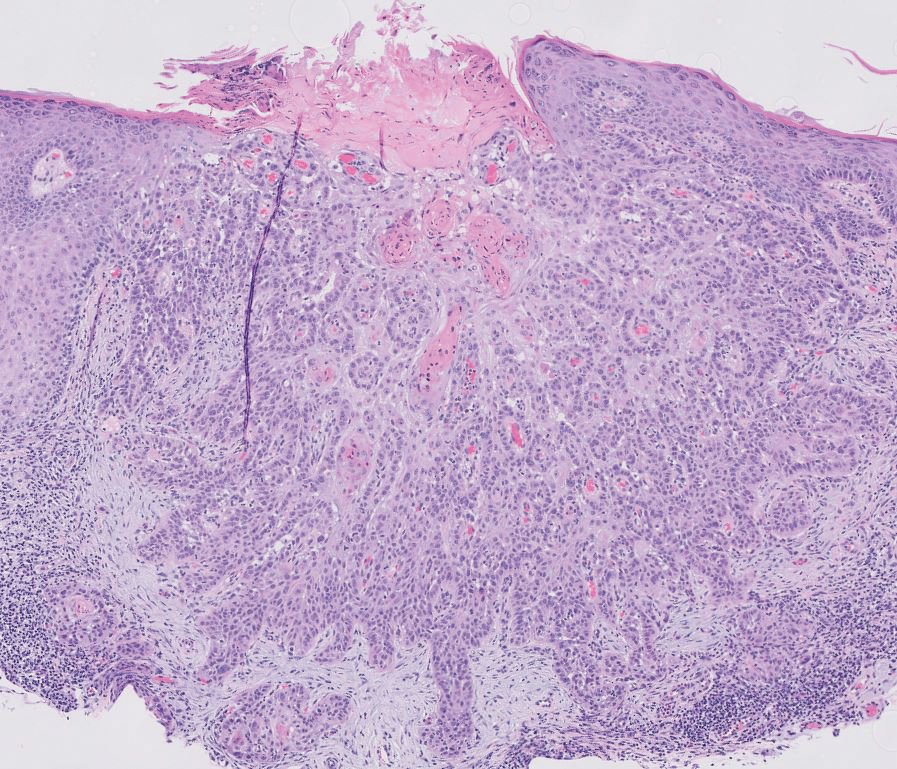

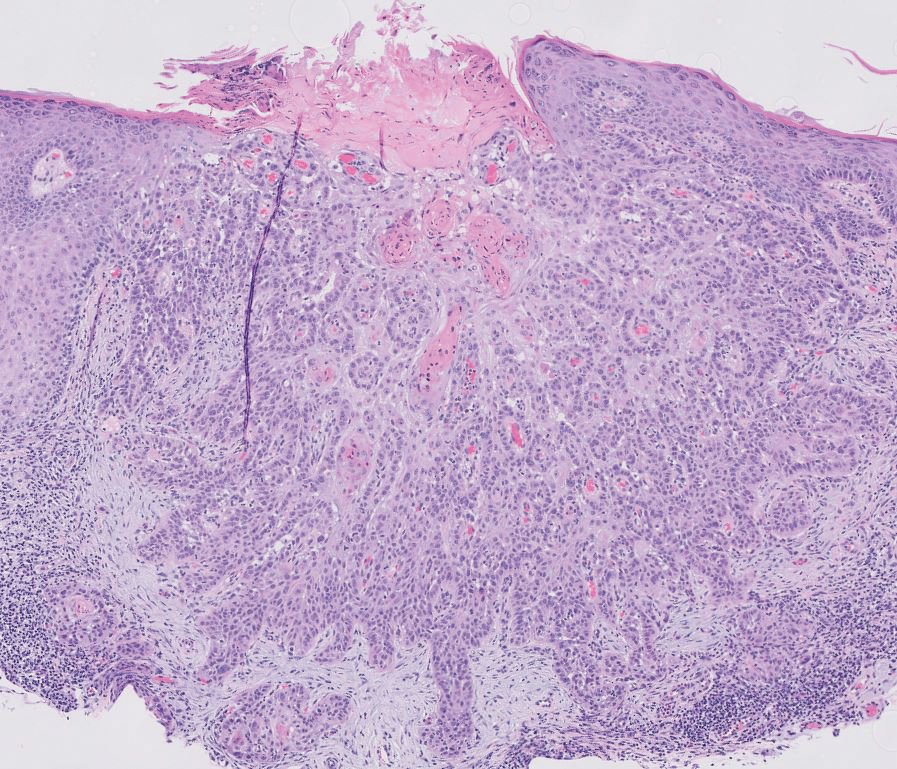

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

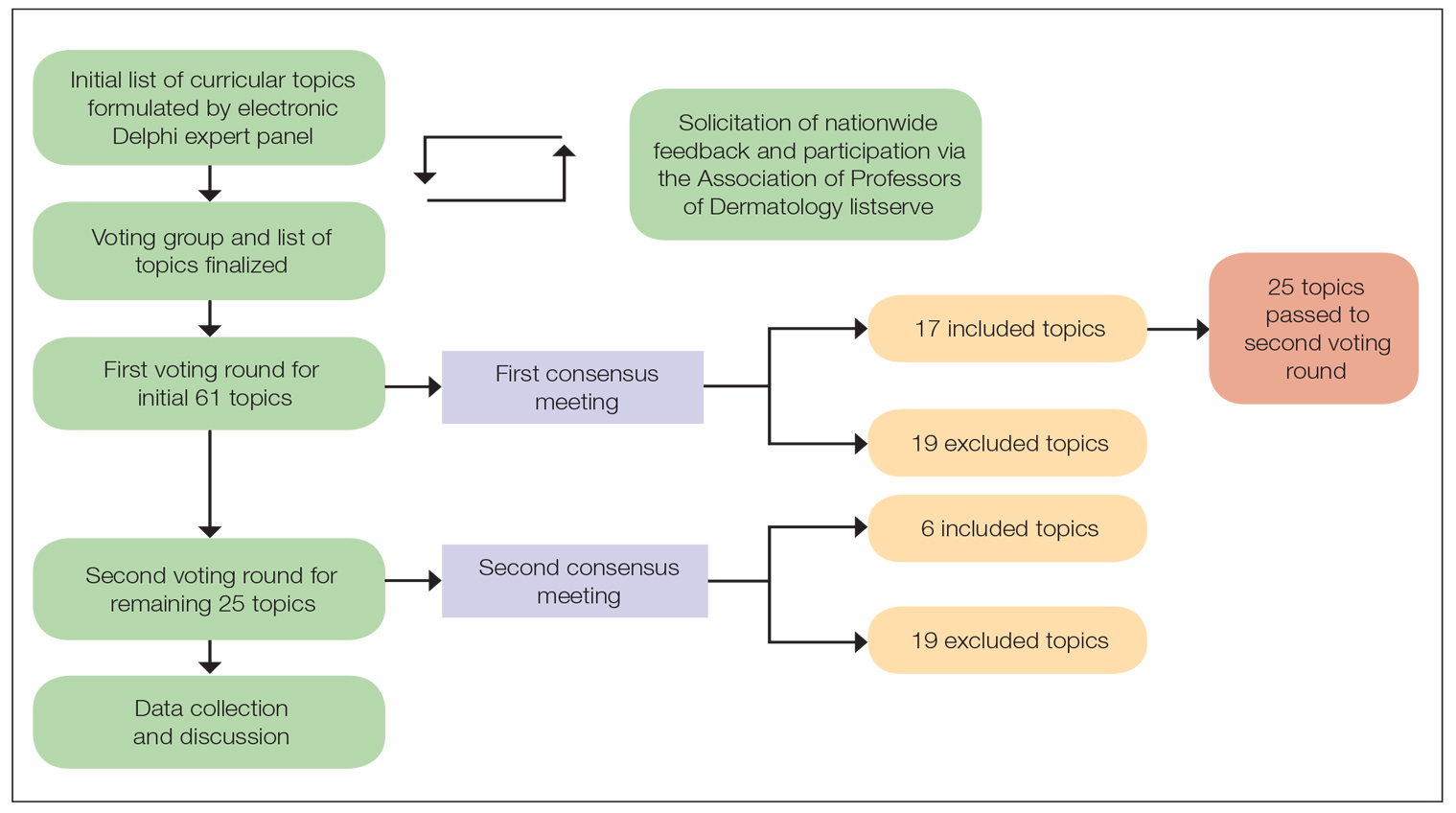

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

A 57-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic papule on the left lower eyelid. The patient reported that the lesion seemed to wax and wane in size over time. Physical examination revealed a small, pink, verrucous papule on the left lower eyelid. A shave biopsy of the lesion revealed a well-circumscribed collection of small, monomorphic, cuboidal cells with basophilic round nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and compact eosinophilic cytoplasm (top) with focal areas of duct formation (bottom) that was sharply demarcated from normal keratinocytes.

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

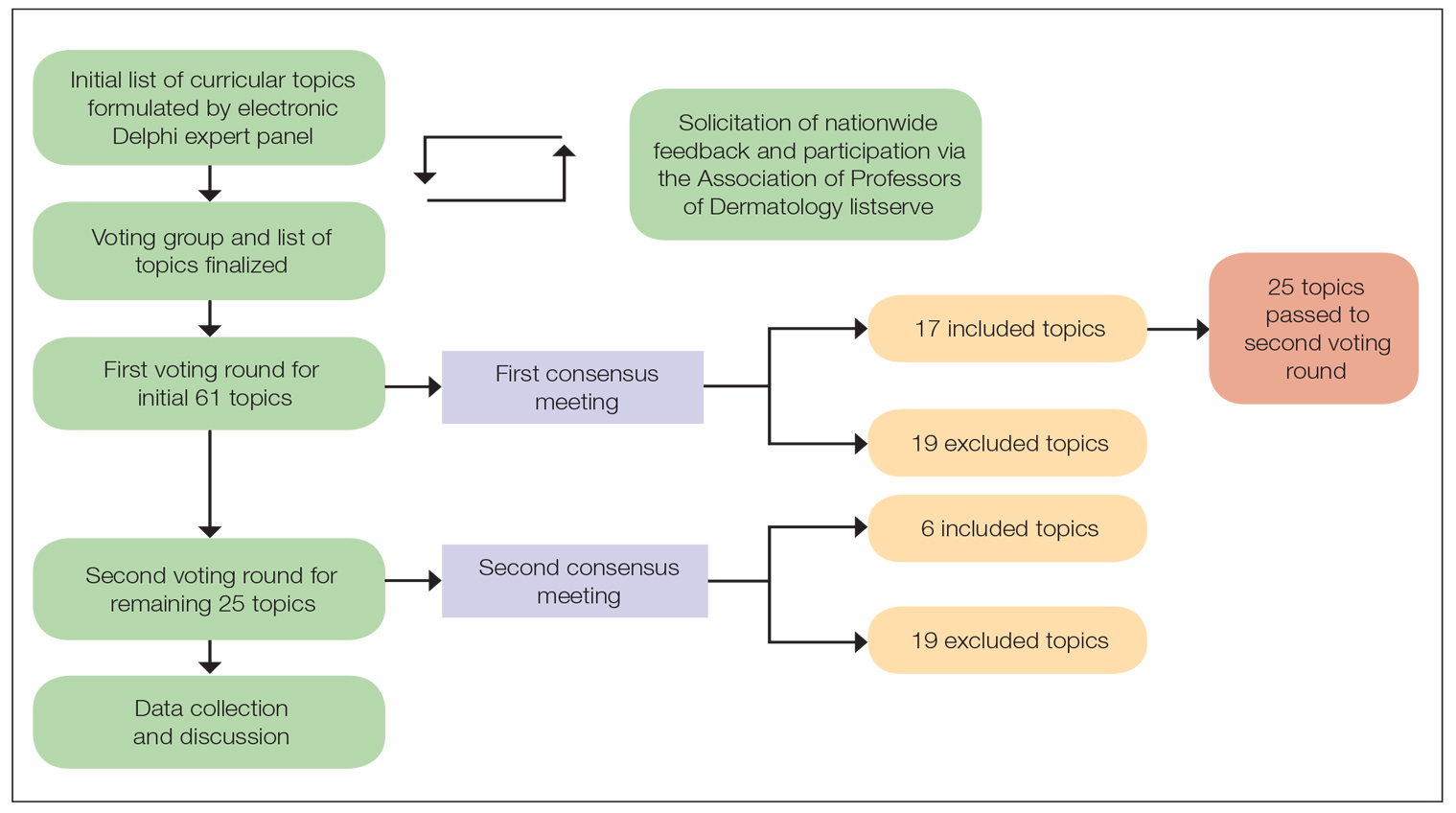

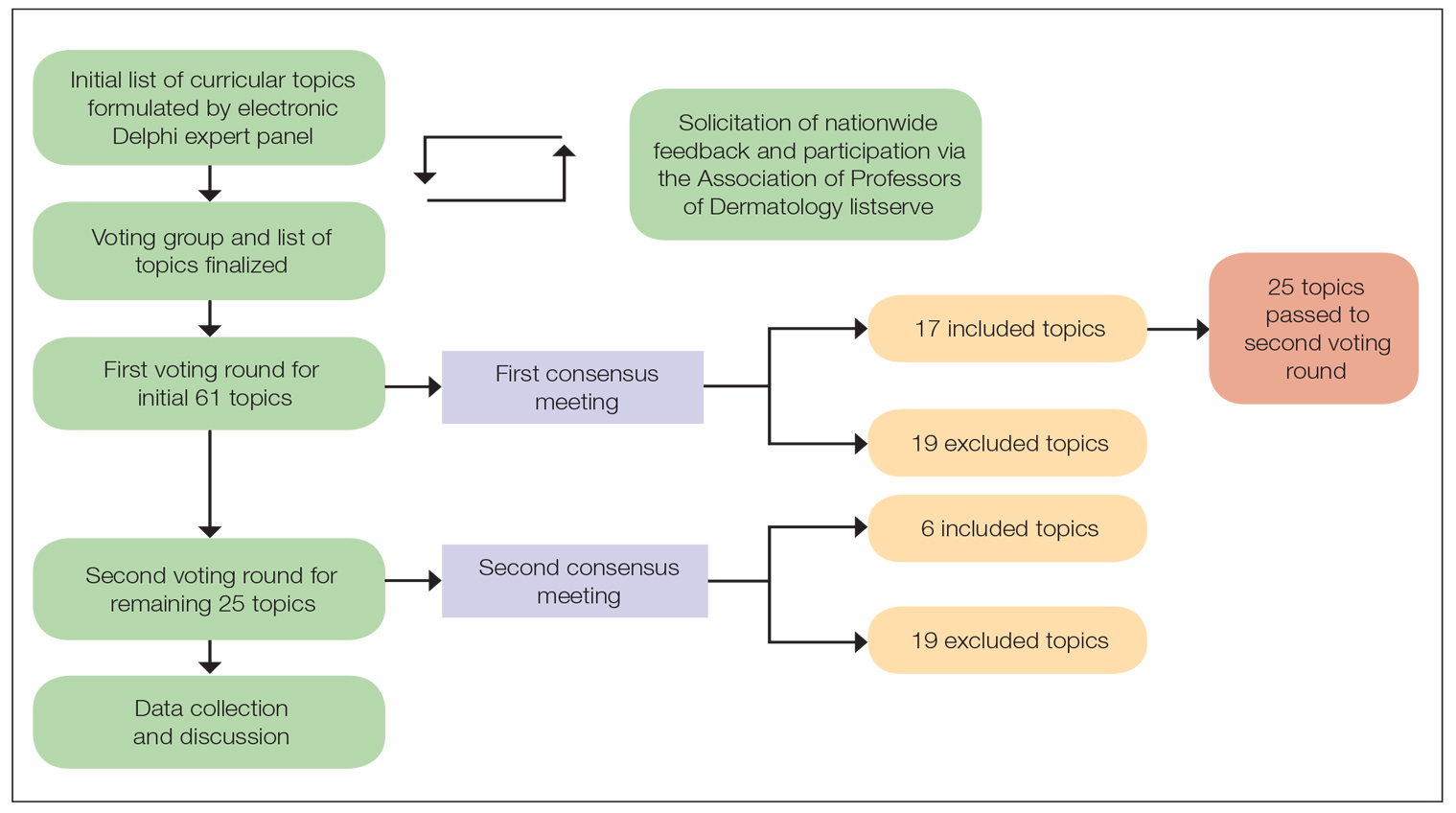

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

PRACTICE POINTS

- Advancing curricula related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology training can improve health outcomes, address health care workforce disparities, and enhance clinical care for diverse patient populations.

- Education on patient-centered communication, cultural humility, and the impact of social determinants of health results in dermatology residents who are better equipped with the necessary tools to effectively care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Imipramine-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Imipramine is a tricyclic medication uncommonly used to treat depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric illnesses. Although relatively rare, it has been associated with hyperpigmentation of the skin including slate gray discoloration of sun-exposed areas.

We present the case of a 63-year-old woman who had been taking imipramine for more than 20 years when she developed bluish gray discoloration on the face and neck. Histopathology of biopsy specimens showed numerous perivascular and interstitial brown globules in the dermis that were composed of melanin only, as evidenced by positive Fontana-Masson staining and negative Perls Prussian blue staining. A diagnosis of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation was made based on histopathology and clinical history.

In addition to the case presentation, we provide a review of drugs that commonly cause hyperpigmentation as well as their associated histopathologic staining characteristics.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman presented with blue-gray discoloration on the face and neck. She first noted the discoloration on the left side of the forehead 3 years prior; it then spread to the right side of the forehead, cheeks, and neck. She denied pruritus, pain, redness, and scaling of the involved areas; any recent changes in medications; or the use of any topical products on the affected areas. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, which was inconsistently controlled with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide, and depression, which had been managed with oral imipramine.

Physical examination disclosed blue-gray hyperpigmented patches with irregular borders on the bilateral forehead, temples, and periorbital skin (Figure 1). Reticulated brown patches were noted on the bilateral cheeks, and the neck displayed diffuse muddy brown patches with sparing of the submental areas.

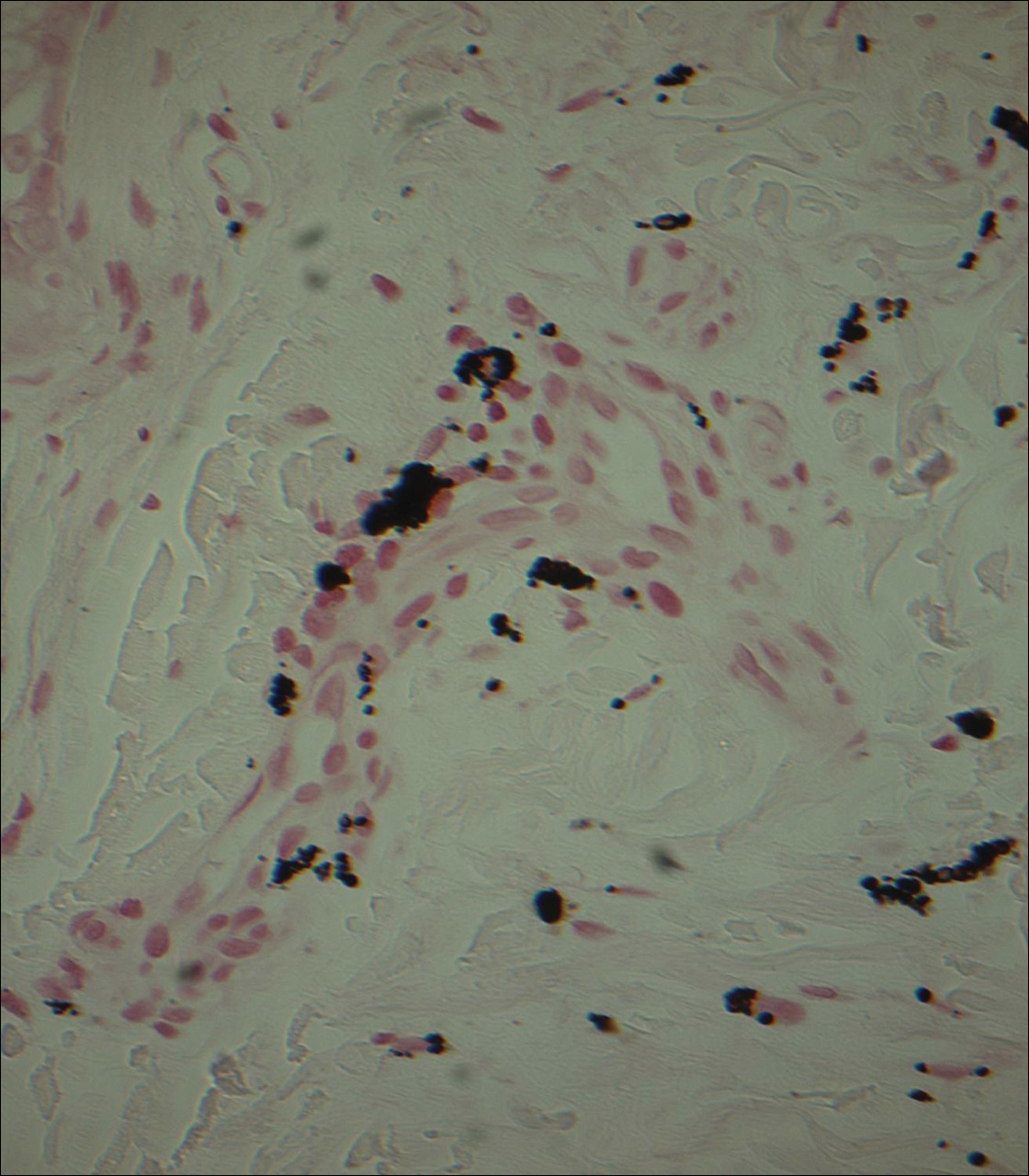

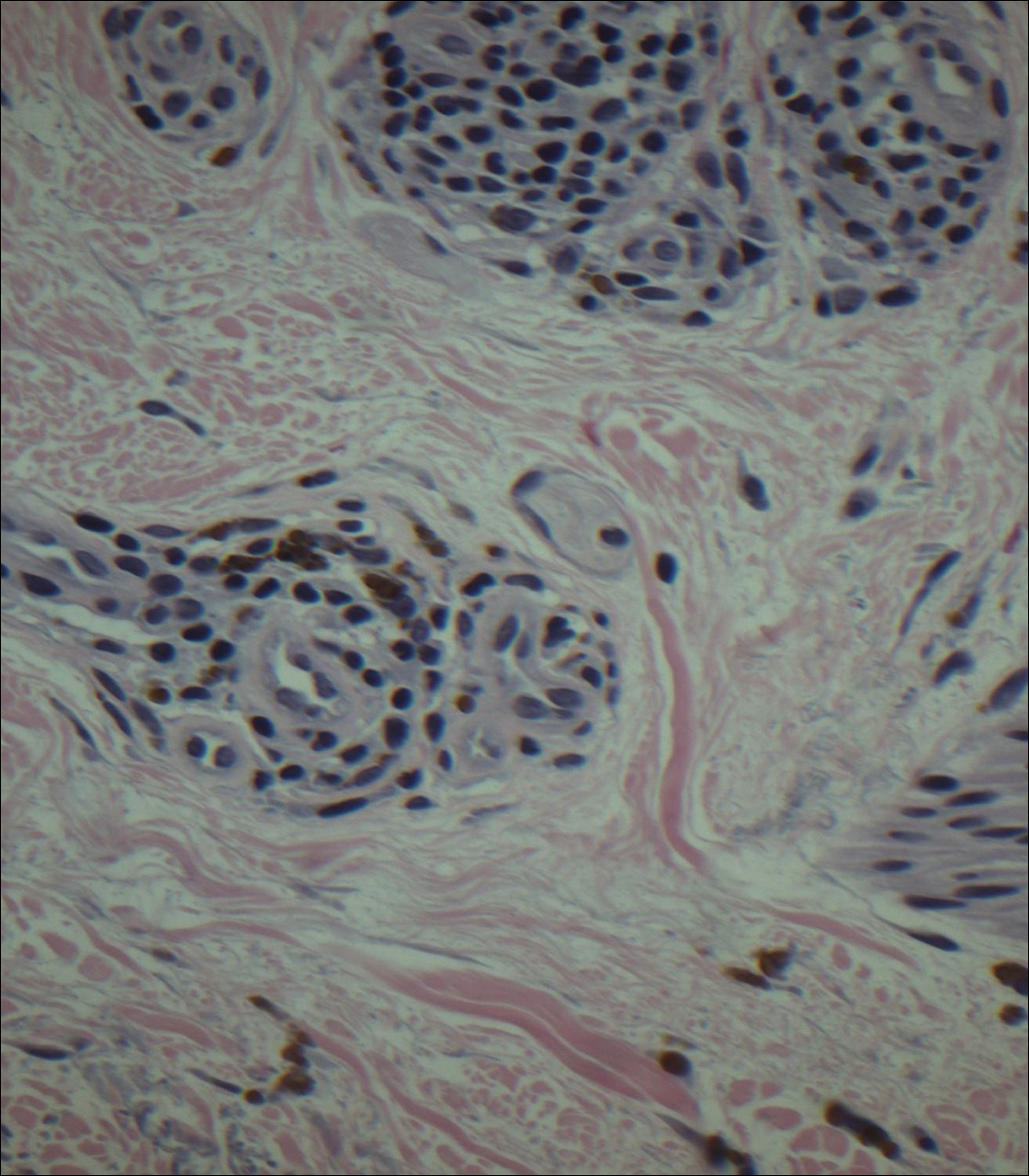

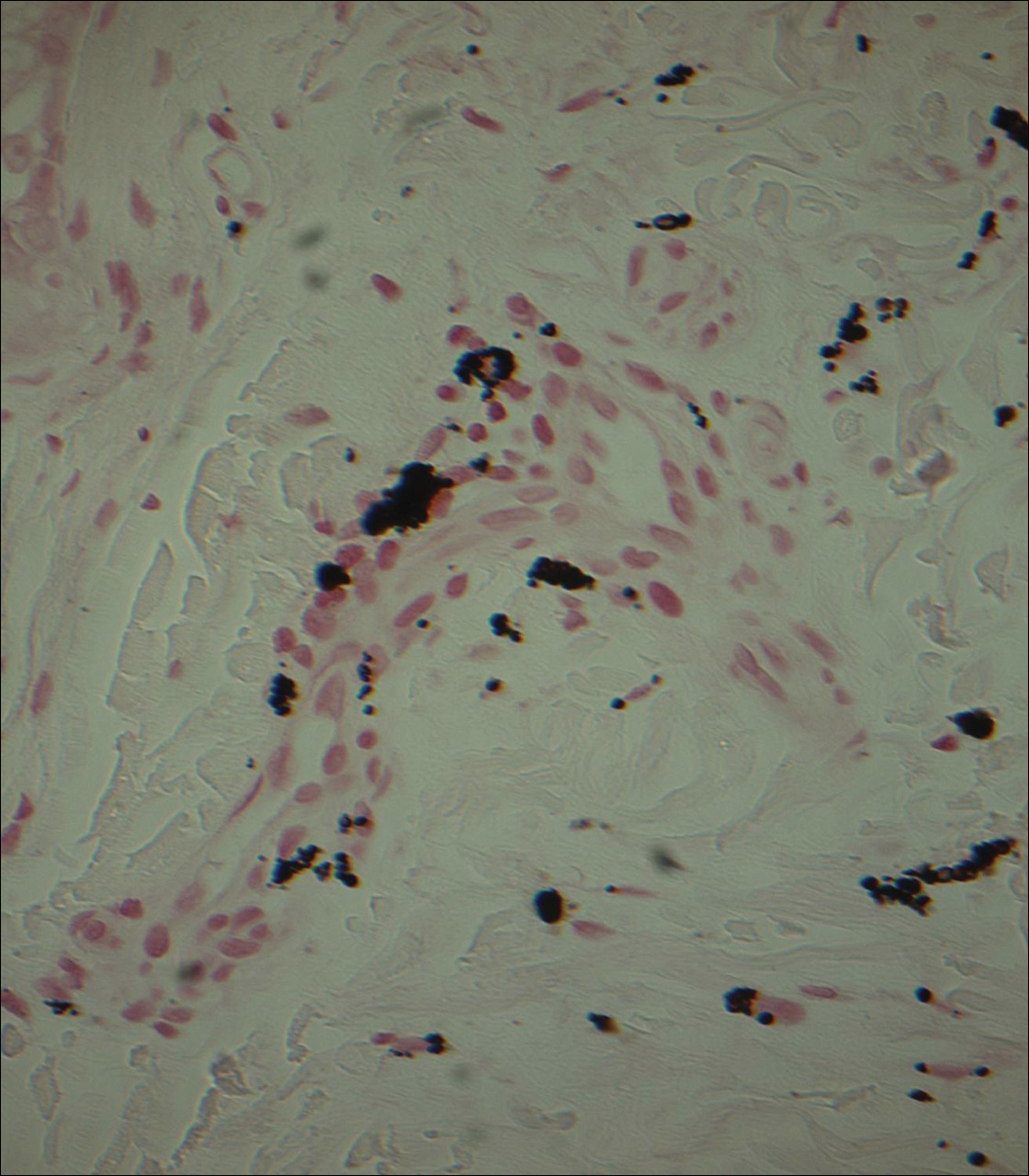

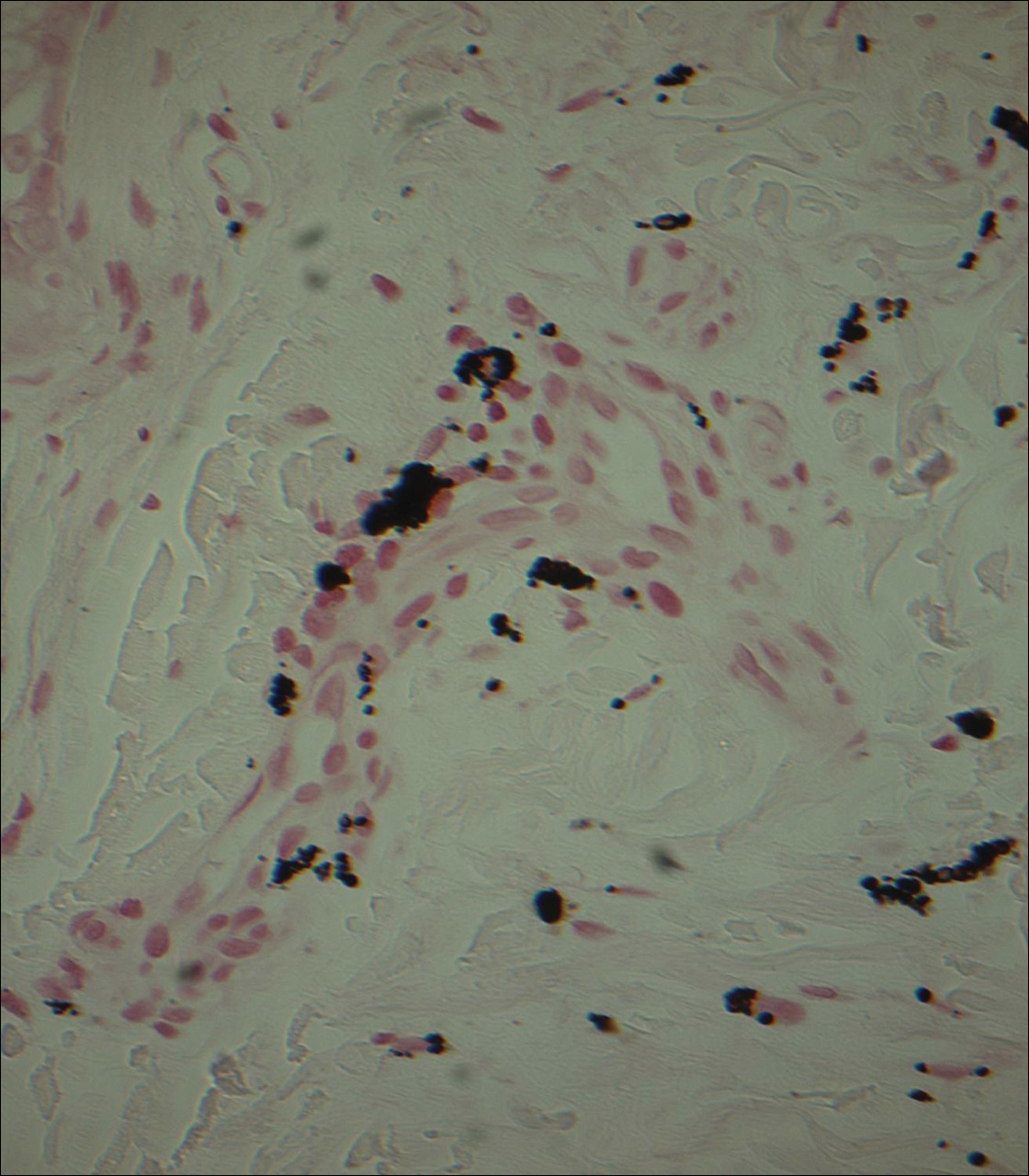

Punch biopsies obtained from the lateral forehead showed an unremarkable epidermis with deposition of numerous golden brown granules in the upper and mid dermis and in perivascular macrophages (Figure 2). The pigmented granules showed positive staining with Fontana-Masson (Figure 3), and a Perls Prussian blue stain for hemosiderin was negative. Based on the clinical history, a diagnosis of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation was made.

The patient revealed that she had taken imipramine for more than 20 years for depression as prescribed by her mental health professional. She had tried several other antidepressants but none were as effective as imipramine. Therefore, she was not willing to discontinue it despite the likelihood that the hyperpigmentation would persist and could worsen with continued use of the medication. Diligent photoprotection was advised. Additionally, she started taking lisinopril some time after the appearance of the hyperpigmentation presented and had not taken hydrochlorothiazide consistently for several years. Although these drugs are known to cause various cutaneous reactions, it was not considered likely in this case.

Comment

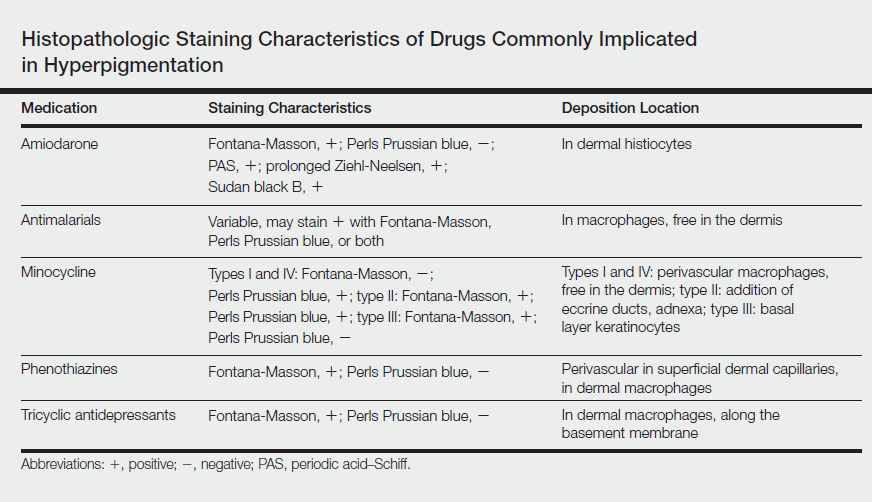

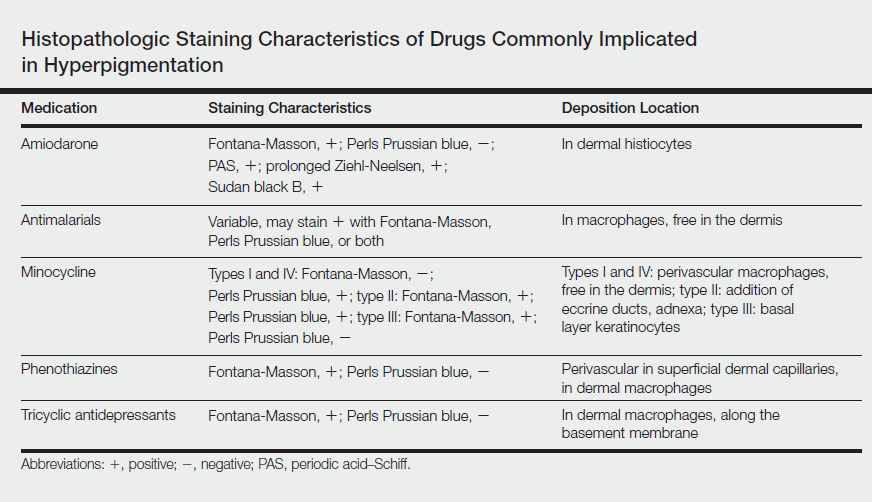

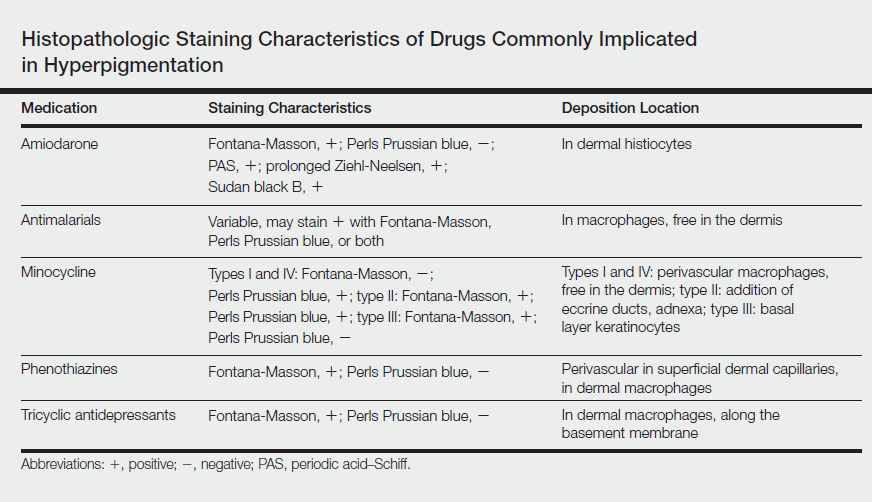

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation accounts for 10% to 20% of all cases of acquired hyperpigmentation.1 Common causative drugs include amiodarone, antimalarials, minocycline, and rarely psychotropics including phenothiazines and tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine.1-4 Although amiodarone-induced hyperpigmentation is associated with lipofuscin in addition to melanin, most other medications, including imipramine, induce cutaneous effects through deposition of melanin and/or hemosiderin. A review of the histopathologic staining characteristics in pigment anomalies caused by these drugs is summarized in the Table.

Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation presents as slate gray discrete macules and patches on sun-exposed skin that may appear anywhere from 2 to 22 years after initiating the medication.1-4 Affected areas include the malar cheeks, temples, periorbital areas, hands, forearms, and seldom the iris and sclera.2-4 Although the blue to slate gray coloring is classic, other colors have been described including brown, golden brown, and purple.2

Histopathology of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation shows golden brown, round to oval granules in the superficial dermis and within dermal macrophages.1,3 Generally, Fontana-Masson staining is positive for melanin and Perls Prussian blue staining is negative for iron.1,2,4

Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation likely results from photoexcitation of imipramine or one of its metabolites. These compounds activate tyrosinase, increasing melanogenesis and leading to formation of melanin-imipramine or melanin-metabolite complexes.1-3 Complexes are deposited in the dermis and basal layer or are engulfed by dermal macrophages and darkened on sun exposure due to their high melanin content.1 Other possible mechanisms of hyperpigmentation include nonspecific inflammation caused by the drug in the skin, hemosiderin deposition from vessel damage and subsequent erythrocyte extravasation, or deposition of newly formed pigments related to the drug.1

Most patients report satisfactory resolution of imipramine-induced discoloration within 1 year of stopping imipramine or switching to a different antidepressant.1,4 Patients who are unwilling to discontinue imipramine may achieve resolution with alexandrite or Q-switched ruby laser therapy.1,4 Strict sun protective measures are necessary, both to prevent new deposition of melanin and to prevent darkening of existing pigment.

Despite the advent of new psychotropic medications, imipramine remains the antidepressant of choice for many patients. Although rare, it is important to be able to recognize imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation and to encourage patient-psychiatrist communication to determine an antidepressant regimen that avoids unnecessary cutaneous side effects.

- D’Agostino ML, Risser J, Robinson-Bostom L. Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:799-803.

- Ming ME, Bhawan J, Stefanato CM, et al. Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation: four cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2, pt 1):159-166.

- Sicari MC, Lebwohl M, Baral J, et al. Photoinduced dermal pigmentation in patients taking tricyclic antidepressants: histology, electron microscopy, and energy dispersive spectroscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol.1999;40(2, pt 2):290-293.

- Atkin DH, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):77-80.

Imipramine is a tricyclic medication uncommonly used to treat depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric illnesses. Although relatively rare, it has been associated with hyperpigmentation of the skin including slate gray discoloration of sun-exposed areas.

We present the case of a 63-year-old woman who had been taking imipramine for more than 20 years when she developed bluish gray discoloration on the face and neck. Histopathology of biopsy specimens showed numerous perivascular and interstitial brown globules in the dermis that were composed of melanin only, as evidenced by positive Fontana-Masson staining and negative Perls Prussian blue staining. A diagnosis of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation was made based on histopathology and clinical history.

In addition to the case presentation, we provide a review of drugs that commonly cause hyperpigmentation as well as their associated histopathologic staining characteristics.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman presented with blue-gray discoloration on the face and neck. She first noted the discoloration on the left side of the forehead 3 years prior; it then spread to the right side of the forehead, cheeks, and neck. She denied pruritus, pain, redness, and scaling of the involved areas; any recent changes in medications; or the use of any topical products on the affected areas. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, which was inconsistently controlled with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide, and depression, which had been managed with oral imipramine.

Physical examination disclosed blue-gray hyperpigmented patches with irregular borders on the bilateral forehead, temples, and periorbital skin (Figure 1). Reticulated brown patches were noted on the bilateral cheeks, and the neck displayed diffuse muddy brown patches with sparing of the submental areas.

Punch biopsies obtained from the lateral forehead showed an unremarkable epidermis with deposition of numerous golden brown granules in the upper and mid dermis and in perivascular macrophages (Figure 2). The pigmented granules showed positive staining with Fontana-Masson (Figure 3), and a Perls Prussian blue stain for hemosiderin was negative. Based on the clinical history, a diagnosis of imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation was made.