User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Fair access crucial for new diabetes/kidney disease drugs, say guidelines

The 2022 guideline update released by the KDIGO organization for managing people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) highlighted the safety and expanded, evidence-based role for agents from three drug classes: the SGLT2 inhibitors, the GLP-1 receptor agonists, and the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

But this key take-away from the guideline also underscored the challenges for ensuring fair and affordable access among US patients to these practice-changing medications.

The impact of widespread adoption of these three drug classes into routine US management of people with diabetes and CKD “will be determined by how effective the health care system and its patients and clinicians are at overcoming individual and structural barriers,” write Milda Saunders, MD, and Neda Laiteerapong, MD, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of a synopsis of the 2022 guideline update in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The synopsis is an 11-page distillation of the full 128-page guideline released by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) organization in 2022.

The recommendations in the 2022 guideline update “are exciting for their potential to change the natural history of CKD and diabetes, but their effect could be highly limited by barriers at multiple levels,” write Dr. Saunders and Dr. Laiteerapong, two internal medicine physicians at the University of Chicago.

“Without equitable implementation of the KDIGO 2022 guidelines there is a potential that clinical practice variation will increase and widen health inequities for minoritized people with CKD and diabetes,” they warn.

Generics to the rescue

One potentially effective, and likely imminent, way to level the prescribing field for patients with CKD and diabetes is for agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist classes to become available in generic formulations.

That should lower prices and thereby boost wider access and will likely occur fairly soon for at least two of the three drug classes, Dr. Laiteerapong predicts.

Some GLP-1 receptor agonists have already escaped patent exclusivity or will do so in 2023, she notes, including the anticipated ability of one drugmaker to start U.S. marketing of generic liraglutide by the end of 2023.

However, whether that manufacturer, Teva, proceeds with generic liraglutide “is a big question,” Dr. Laiteerapong said in an interview. She cited Teva’s history of failing to introduce a generic formulation of exenatide onto the U.S. market even though it has had a green light to do so since 2017.

The only nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist now on the market is finerenone (Kerendia), which will not go off patent for several more years, but for some branded SGLT2 inhibitors, U.S. patents will expire in 2025. In addition, remogliflozin is an SGLT2 inhibitor that “may have already lost patent exclusivity,” noted Dr. Laiteerapong, although it has also never received U.S. marketing approval.

Dr. Laiteerapong expressed optimism that the overall trajectory of access is on the rise. “Many people have type 2 diabetes, and these drugs are in demand,” she noted. She also pointed to progress recently made on insulin affordability. “Things will get better as long as people advocate and argue for equity,” she maintained.

Incentivize formulary listings

Dr. Laiteerapong cited other approaches that could boost access to these medications, such as “creating incentives for pharmaceutical companies to ensure that [these drugs] are on formularies” of large, government-affiliated U.S. health insurance programs, such as Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Part D, state Medicaid plans, and coverage through U.S. Veterans Affairs and the Tricare health insurance plans available to active members of the US military.

The editorial she coauthored with Dr. Saunders also calls for future collaborations among various medical societies to create “a more unified and streamlined set of recommendations” that benefits patients with diabetes, CKD, and multiple other chronic conditions.

“Over the last decade, we have seen more societies willing to present cooperative guidelines, as well as a surge in research on patients who live with multiple chronic conditions. There is momentum that will allow these different societies to work together,” Dr. Laiteerapong said.

Dr. Laiteerapong and Dr. Saunders have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2022 guideline update released by the KDIGO organization for managing people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) highlighted the safety and expanded, evidence-based role for agents from three drug classes: the SGLT2 inhibitors, the GLP-1 receptor agonists, and the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

But this key take-away from the guideline also underscored the challenges for ensuring fair and affordable access among US patients to these practice-changing medications.

The impact of widespread adoption of these three drug classes into routine US management of people with diabetes and CKD “will be determined by how effective the health care system and its patients and clinicians are at overcoming individual and structural barriers,” write Milda Saunders, MD, and Neda Laiteerapong, MD, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of a synopsis of the 2022 guideline update in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The synopsis is an 11-page distillation of the full 128-page guideline released by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) organization in 2022.

The recommendations in the 2022 guideline update “are exciting for their potential to change the natural history of CKD and diabetes, but their effect could be highly limited by barriers at multiple levels,” write Dr. Saunders and Dr. Laiteerapong, two internal medicine physicians at the University of Chicago.

“Without equitable implementation of the KDIGO 2022 guidelines there is a potential that clinical practice variation will increase and widen health inequities for minoritized people with CKD and diabetes,” they warn.

Generics to the rescue

One potentially effective, and likely imminent, way to level the prescribing field for patients with CKD and diabetes is for agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist classes to become available in generic formulations.

That should lower prices and thereby boost wider access and will likely occur fairly soon for at least two of the three drug classes, Dr. Laiteerapong predicts.

Some GLP-1 receptor agonists have already escaped patent exclusivity or will do so in 2023, she notes, including the anticipated ability of one drugmaker to start U.S. marketing of generic liraglutide by the end of 2023.

However, whether that manufacturer, Teva, proceeds with generic liraglutide “is a big question,” Dr. Laiteerapong said in an interview. She cited Teva’s history of failing to introduce a generic formulation of exenatide onto the U.S. market even though it has had a green light to do so since 2017.

The only nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist now on the market is finerenone (Kerendia), which will not go off patent for several more years, but for some branded SGLT2 inhibitors, U.S. patents will expire in 2025. In addition, remogliflozin is an SGLT2 inhibitor that “may have already lost patent exclusivity,” noted Dr. Laiteerapong, although it has also never received U.S. marketing approval.

Dr. Laiteerapong expressed optimism that the overall trajectory of access is on the rise. “Many people have type 2 diabetes, and these drugs are in demand,” she noted. She also pointed to progress recently made on insulin affordability. “Things will get better as long as people advocate and argue for equity,” she maintained.

Incentivize formulary listings

Dr. Laiteerapong cited other approaches that could boost access to these medications, such as “creating incentives for pharmaceutical companies to ensure that [these drugs] are on formularies” of large, government-affiliated U.S. health insurance programs, such as Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Part D, state Medicaid plans, and coverage through U.S. Veterans Affairs and the Tricare health insurance plans available to active members of the US military.

The editorial she coauthored with Dr. Saunders also calls for future collaborations among various medical societies to create “a more unified and streamlined set of recommendations” that benefits patients with diabetes, CKD, and multiple other chronic conditions.

“Over the last decade, we have seen more societies willing to present cooperative guidelines, as well as a surge in research on patients who live with multiple chronic conditions. There is momentum that will allow these different societies to work together,” Dr. Laiteerapong said.

Dr. Laiteerapong and Dr. Saunders have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2022 guideline update released by the KDIGO organization for managing people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) highlighted the safety and expanded, evidence-based role for agents from three drug classes: the SGLT2 inhibitors, the GLP-1 receptor agonists, and the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

But this key take-away from the guideline also underscored the challenges for ensuring fair and affordable access among US patients to these practice-changing medications.

The impact of widespread adoption of these three drug classes into routine US management of people with diabetes and CKD “will be determined by how effective the health care system and its patients and clinicians are at overcoming individual and structural barriers,” write Milda Saunders, MD, and Neda Laiteerapong, MD, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of a synopsis of the 2022 guideline update in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The synopsis is an 11-page distillation of the full 128-page guideline released by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) organization in 2022.

The recommendations in the 2022 guideline update “are exciting for their potential to change the natural history of CKD and diabetes, but their effect could be highly limited by barriers at multiple levels,” write Dr. Saunders and Dr. Laiteerapong, two internal medicine physicians at the University of Chicago.

“Without equitable implementation of the KDIGO 2022 guidelines there is a potential that clinical practice variation will increase and widen health inequities for minoritized people with CKD and diabetes,” they warn.

Generics to the rescue

One potentially effective, and likely imminent, way to level the prescribing field for patients with CKD and diabetes is for agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist classes to become available in generic formulations.

That should lower prices and thereby boost wider access and will likely occur fairly soon for at least two of the three drug classes, Dr. Laiteerapong predicts.

Some GLP-1 receptor agonists have already escaped patent exclusivity or will do so in 2023, she notes, including the anticipated ability of one drugmaker to start U.S. marketing of generic liraglutide by the end of 2023.

However, whether that manufacturer, Teva, proceeds with generic liraglutide “is a big question,” Dr. Laiteerapong said in an interview. She cited Teva’s history of failing to introduce a generic formulation of exenatide onto the U.S. market even though it has had a green light to do so since 2017.

The only nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist now on the market is finerenone (Kerendia), which will not go off patent for several more years, but for some branded SGLT2 inhibitors, U.S. patents will expire in 2025. In addition, remogliflozin is an SGLT2 inhibitor that “may have already lost patent exclusivity,” noted Dr. Laiteerapong, although it has also never received U.S. marketing approval.

Dr. Laiteerapong expressed optimism that the overall trajectory of access is on the rise. “Many people have type 2 diabetes, and these drugs are in demand,” she noted. She also pointed to progress recently made on insulin affordability. “Things will get better as long as people advocate and argue for equity,” she maintained.

Incentivize formulary listings

Dr. Laiteerapong cited other approaches that could boost access to these medications, such as “creating incentives for pharmaceutical companies to ensure that [these drugs] are on formularies” of large, government-affiliated U.S. health insurance programs, such as Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Part D, state Medicaid plans, and coverage through U.S. Veterans Affairs and the Tricare health insurance plans available to active members of the US military.

The editorial she coauthored with Dr. Saunders also calls for future collaborations among various medical societies to create “a more unified and streamlined set of recommendations” that benefits patients with diabetes, CKD, and multiple other chronic conditions.

“Over the last decade, we have seen more societies willing to present cooperative guidelines, as well as a surge in research on patients who live with multiple chronic conditions. There is momentum that will allow these different societies to work together,” Dr. Laiteerapong said.

Dr. Laiteerapong and Dr. Saunders have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

PPI use in type 2 diabetes links with cardiovascular events

Among people with type 2 diabetes who self-reported regularly using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events as well as all-cause death was significantly increased in a study of more than 19,000 people with type 2 diabetes in a prospective U.K. database.

During median follow-up of about 11 years, regular use of a PPI by people with type 2 diabetes was significantly linked with a 27% relative increase in the incidence of coronary artery disease, compared with nonuse of a PPI, after full adjustment for potential confounding variables.

The results also show PPI use was significantly linked after full adjustment with a 34% relative increase in MI, a 35% relative increase in heart failure, and a 30% relative increase in all-cause death, say a team of Chinese researchers in a recent report in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

PPIs are a medication class widely used in both over-the-counter and prescription formulations to reduce acid production in the stomach and to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease and other acid-related disorders. The PPI class includes such widely used agents as esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and omeprazole (Prilosec).

The analyses in this report, which used data collected in the UK Biobank, are “rigorous,” and the findings of “a modest elevation of CVD risk are consistent with a growing number of observational studies in populations with and without diabetes,” commented Mary R. Rooney, PhD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who focuses on diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Prior observational reports

For example, a report from a prospective, observational study of more than 4300 U.S. residents published in 2021 that Dr. Rooney coauthored documented that cumulative PPI exposure for more than 5 years was significantly linked with a twofold increase in the rate of CVD events, compared with people who did not use a PPI. (This analysis did not examine a possible effect of diabetes status.)

And in a separate prospective, observational study of more than 1,000 Australians with type 2 diabetes, initiation of PPI treatment was significantly linked with a 3.6-fold increased incidence of CVD events, compared with PPI nonuse.

However, Dr. Rooney cautioned that the role of PPI use in raising CVD events “is still an unresolved question. It is too soon to tell if PPI use in people with diabetes should trigger additional caution.” Findings are needed from prospective, randomized trials to determine more definitively whether PPIs play a causal role in the incidence of CVD events, she said in an interview.

U.S. practice often results in unwarranted prolongation of PPI treatment, said the authors of an editorial that accompanied the 2021 report by Dr. Rooney and coauthors.

Long-term PPI use threatens harm

“The practice of initiating stress ulcer prophylaxis [by administering a PPI] in critical care is common,” wrote the authors of the 2021 editorial, Nitin Malik, MD, and William S. Weintraub, MD. “Although it is data driven and well intentioned, the possibility of causing harm – if it is continued on a long-term basis after resolution of the acute illness – is palpable.”

The new analyses using UK Biobank data included 19,229 adults with type 2 diabetes and no preexisting coronary artery disease, MI, heart failure, or stroke. The cohort included 15,954 people (83%) who did not report using a PPI and 3,275 who currently used PPIs regularly. Study limitations include self-report as the only verification of PPI use and lack of information on type of PPI, dose size, or use duration.

The findings remained consistent in several sensitivity analyses, including a propensity score–matched analysis and after further adjustment for use of histamine2 receptor antagonists, a drug class with indications similar to those for PPIs.

The authors of the report speculated that mechanisms that might link PPI use and increased CVD and mortality risk could include changes to the gut microbiota and possible interactions between PPIs and antiplatelet agents.

The study received no commercial funding. The authors and Dr. Rooney disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among people with type 2 diabetes who self-reported regularly using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events as well as all-cause death was significantly increased in a study of more than 19,000 people with type 2 diabetes in a prospective U.K. database.

During median follow-up of about 11 years, regular use of a PPI by people with type 2 diabetes was significantly linked with a 27% relative increase in the incidence of coronary artery disease, compared with nonuse of a PPI, after full adjustment for potential confounding variables.

The results also show PPI use was significantly linked after full adjustment with a 34% relative increase in MI, a 35% relative increase in heart failure, and a 30% relative increase in all-cause death, say a team of Chinese researchers in a recent report in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

PPIs are a medication class widely used in both over-the-counter and prescription formulations to reduce acid production in the stomach and to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease and other acid-related disorders. The PPI class includes such widely used agents as esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and omeprazole (Prilosec).

The analyses in this report, which used data collected in the UK Biobank, are “rigorous,” and the findings of “a modest elevation of CVD risk are consistent with a growing number of observational studies in populations with and without diabetes,” commented Mary R. Rooney, PhD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who focuses on diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Prior observational reports

For example, a report from a prospective, observational study of more than 4300 U.S. residents published in 2021 that Dr. Rooney coauthored documented that cumulative PPI exposure for more than 5 years was significantly linked with a twofold increase in the rate of CVD events, compared with people who did not use a PPI. (This analysis did not examine a possible effect of diabetes status.)

And in a separate prospective, observational study of more than 1,000 Australians with type 2 diabetes, initiation of PPI treatment was significantly linked with a 3.6-fold increased incidence of CVD events, compared with PPI nonuse.

However, Dr. Rooney cautioned that the role of PPI use in raising CVD events “is still an unresolved question. It is too soon to tell if PPI use in people with diabetes should trigger additional caution.” Findings are needed from prospective, randomized trials to determine more definitively whether PPIs play a causal role in the incidence of CVD events, she said in an interview.

U.S. practice often results in unwarranted prolongation of PPI treatment, said the authors of an editorial that accompanied the 2021 report by Dr. Rooney and coauthors.

Long-term PPI use threatens harm

“The practice of initiating stress ulcer prophylaxis [by administering a PPI] in critical care is common,” wrote the authors of the 2021 editorial, Nitin Malik, MD, and William S. Weintraub, MD. “Although it is data driven and well intentioned, the possibility of causing harm – if it is continued on a long-term basis after resolution of the acute illness – is palpable.”

The new analyses using UK Biobank data included 19,229 adults with type 2 diabetes and no preexisting coronary artery disease, MI, heart failure, or stroke. The cohort included 15,954 people (83%) who did not report using a PPI and 3,275 who currently used PPIs regularly. Study limitations include self-report as the only verification of PPI use and lack of information on type of PPI, dose size, or use duration.

The findings remained consistent in several sensitivity analyses, including a propensity score–matched analysis and after further adjustment for use of histamine2 receptor antagonists, a drug class with indications similar to those for PPIs.

The authors of the report speculated that mechanisms that might link PPI use and increased CVD and mortality risk could include changes to the gut microbiota and possible interactions between PPIs and antiplatelet agents.

The study received no commercial funding. The authors and Dr. Rooney disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among people with type 2 diabetes who self-reported regularly using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events as well as all-cause death was significantly increased in a study of more than 19,000 people with type 2 diabetes in a prospective U.K. database.

During median follow-up of about 11 years, regular use of a PPI by people with type 2 diabetes was significantly linked with a 27% relative increase in the incidence of coronary artery disease, compared with nonuse of a PPI, after full adjustment for potential confounding variables.

The results also show PPI use was significantly linked after full adjustment with a 34% relative increase in MI, a 35% relative increase in heart failure, and a 30% relative increase in all-cause death, say a team of Chinese researchers in a recent report in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

PPIs are a medication class widely used in both over-the-counter and prescription formulations to reduce acid production in the stomach and to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease and other acid-related disorders. The PPI class includes such widely used agents as esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and omeprazole (Prilosec).

The analyses in this report, which used data collected in the UK Biobank, are “rigorous,” and the findings of “a modest elevation of CVD risk are consistent with a growing number of observational studies in populations with and without diabetes,” commented Mary R. Rooney, PhD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who focuses on diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Prior observational reports

For example, a report from a prospective, observational study of more than 4300 U.S. residents published in 2021 that Dr. Rooney coauthored documented that cumulative PPI exposure for more than 5 years was significantly linked with a twofold increase in the rate of CVD events, compared with people who did not use a PPI. (This analysis did not examine a possible effect of diabetes status.)

And in a separate prospective, observational study of more than 1,000 Australians with type 2 diabetes, initiation of PPI treatment was significantly linked with a 3.6-fold increased incidence of CVD events, compared with PPI nonuse.

However, Dr. Rooney cautioned that the role of PPI use in raising CVD events “is still an unresolved question. It is too soon to tell if PPI use in people with diabetes should trigger additional caution.” Findings are needed from prospective, randomized trials to determine more definitively whether PPIs play a causal role in the incidence of CVD events, she said in an interview.

U.S. practice often results in unwarranted prolongation of PPI treatment, said the authors of an editorial that accompanied the 2021 report by Dr. Rooney and coauthors.

Long-term PPI use threatens harm

“The practice of initiating stress ulcer prophylaxis [by administering a PPI] in critical care is common,” wrote the authors of the 2021 editorial, Nitin Malik, MD, and William S. Weintraub, MD. “Although it is data driven and well intentioned, the possibility of causing harm – if it is continued on a long-term basis after resolution of the acute illness – is palpable.”

The new analyses using UK Biobank data included 19,229 adults with type 2 diabetes and no preexisting coronary artery disease, MI, heart failure, or stroke. The cohort included 15,954 people (83%) who did not report using a PPI and 3,275 who currently used PPIs regularly. Study limitations include self-report as the only verification of PPI use and lack of information on type of PPI, dose size, or use duration.

The findings remained consistent in several sensitivity analyses, including a propensity score–matched analysis and after further adjustment for use of histamine2 receptor antagonists, a drug class with indications similar to those for PPIs.

The authors of the report speculated that mechanisms that might link PPI use and increased CVD and mortality risk could include changes to the gut microbiota and possible interactions between PPIs and antiplatelet agents.

The study received no commercial funding. The authors and Dr. Rooney disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY AND METABOLISM

Some BP meds tied to significantly lower risk for dementia, Alzheimer’s

Antihypertensive medications that stimulate rather than inhibit type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors can lower the rate of dementia among new users of these medications, new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 57,000 older Medicare beneficiaries showed that the initiation of antihypertensives that stimulate the receptors was linked to a 16% lower risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD) and an 18% lower risk for vascular dementia compared with those that inhibit the receptors.

“Achieving appropriate blood pressure control is essential for maximizing brain health, and this promising research suggests certain antihypertensives could yield brain benefit compared to others,” lead study author Zachary A. Marcum, PharmD, PhD, associate professor, University of Washington School of Pharmacy, Seattle, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Medicare beneficiaries

Previous observational studies showed that antihypertensive medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, in comparison with those that don’t, were associated with lower rates of dementia. However, those studies included individuals with prevalent hypertension and were relatively small.

The new retrospective cohort study included a random sample of 57,773 Medicare beneficiaries aged at least 65 years with new-onset hypertension. The mean age of participants was 73.8 years, 62.9% were women, and 86.9% were White.

Over the course of the study, some participants filled at least one prescription for a stimulating angiotensin II receptor type 2 and 4, such as angiotensin II receptor type 1 blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.

Others participants filled a prescription for an inhibiting type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

“All these medications lower blood pressure, but they do it in different ways,” said Dr. Marcum.

The researchers were interested in the varying activity of these drugs at the type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.

For each 30-day interval, they categorized beneficiaries into four groups: a stimulating medication group (n = 4,879) consisting of individuals mostly taking stimulating antihypertensives; an inhibiting medication group (n = 10,303) that mostly included individuals prescribed this type of antihypertensive; a mixed group (n = 2,179) that included a combination of the first two classifications; and a nonuser group (n = 40,413) of individuals who were not using either type of drug.

The primary outcome was time to first occurrence of ADRD. The secondary outcome was time to first occurrence of vascular dementia.

Researchers controlled for cardiovascular risk factors and sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and receipt of low-income subsidy.

Unanswered questions

After adjustments, results showed that initiation of an antihypertensive medication regimen that exclusively stimulates, rather than inhibits, type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors was associated with a 16% lower risk for incident ADRD over a follow-up of just under 7 years (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.90; P < .001).

The mixed regimen was also associated with statistically significant (P = .001) reduced odds of ADRD compared with the inhibiting medications.

As for vascular dementia, use of stimulating vs. inhibiting medications was associated with an 18% lower risk (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.96; P = .02).

Again, use of the mixed regimen was associated with reduced risk of vascular dementia compared with the inhibiting medications (P = .03).

A variety of potential mechanisms might explain the superiority of stimulating agents when it comes to dementia risk, said Dr. Marcum. These could include, for example, increased blood flow to the brain and reduced amyloid.

“But more mechanistic work is needed as well as evaluation of dose responses, because that’s not something we looked at in this study,” Dr. Marcum said. “There are still a lot of unanswered questions.”

Stimulators instead of inhibitors?

The results of the current analysis come on the heels of some previous work showing the benefits of lowering blood pressure. For example, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) showed that targeting a systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg significantly reduces risk for heart disease, stroke, and death from these diseases.

But in contrast to previous research, the current study included only beneficiaries with incident hypertension and new use of antihypertensive medications, and it adjusted for time-varying confounding.

Prescribing stimulating instead of inhibiting treatments could make a difference at the population level, Dr. Marcum noted.

“If we could shift the prescribing a little bit from inhibiting to stimulating, that could possibly reduce dementia risk,” he said.

However, “we’re not suggesting [that all patients] have their regimen switched,” he added.

That’s because inhibiting medications still have an important place in the antihypertensive treatment armamentarium, Dr. Marcum noted. As an example, beta-blockers are used post heart attack.

As well, factors such as cost and side effects should be taken into consideration when prescribing an antihypertensive drug.

The new results could be used to set up a comparison in a future randomized controlled trial that would provide the strongest evidence for estimating causal effects of treatments, said Dr. Marcum.

‘More convincing’

Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study is “more convincing” than previous related research, as it has a larger sample size and a longer follow-up.

“And the exquisite statistical analysis gives more robustness, more solidity, to the hypothesis that drugs that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors might be protective for dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego, who was not involved with the research.

However, he noted that the retrospective study had some limitations, including the underdiagnosis of dementia. “The diagnosis of dementia is, honestly, very poorly done in the clinical setting,” he said.

As well, the study could be subject to “confounding by indication,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said. “There could be a third variable, another confounding factor, that’s responsible both for the dementia and for the prescription of these drugs,” he added.

For example, he noted that comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and heart failure might increase the risk of dementia.

He agreed with the investigators that a randomized clinical trial would address these limitations. “All comorbidities would be equally shared” in the randomized groups, and all participants would be given “a specific test for dementia at the same time,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said.

Still, he noted that the new results are in keeping with hypertension guidelines that recommend stimulating drugs.

“This trial definitely shows that the current hypertension guidelines are good treatment for our patients, not only to control blood pressure and not only to prevent infarction to prevent stroke but also to prevent dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego.

Also commenting for this news organization, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the new data provide “clarity” on why previous research had differing results on the effect of antihypertensives on cognition.

Among the caveats of this new analysis is that “it’s unclear if the demographics in this study are fully representative of Medicare beneficiaries,” said Dr. Snyder.

She, too, said a clinical trial is important “to understand if there is a preventative and/or treatment potential in the medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.”

The study received funding from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcum and Dr. Santos-Gallego have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antihypertensive medications that stimulate rather than inhibit type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors can lower the rate of dementia among new users of these medications, new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 57,000 older Medicare beneficiaries showed that the initiation of antihypertensives that stimulate the receptors was linked to a 16% lower risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD) and an 18% lower risk for vascular dementia compared with those that inhibit the receptors.

“Achieving appropriate blood pressure control is essential for maximizing brain health, and this promising research suggests certain antihypertensives could yield brain benefit compared to others,” lead study author Zachary A. Marcum, PharmD, PhD, associate professor, University of Washington School of Pharmacy, Seattle, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Medicare beneficiaries

Previous observational studies showed that antihypertensive medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, in comparison with those that don’t, were associated with lower rates of dementia. However, those studies included individuals with prevalent hypertension and were relatively small.

The new retrospective cohort study included a random sample of 57,773 Medicare beneficiaries aged at least 65 years with new-onset hypertension. The mean age of participants was 73.8 years, 62.9% were women, and 86.9% were White.

Over the course of the study, some participants filled at least one prescription for a stimulating angiotensin II receptor type 2 and 4, such as angiotensin II receptor type 1 blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.

Others participants filled a prescription for an inhibiting type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

“All these medications lower blood pressure, but they do it in different ways,” said Dr. Marcum.

The researchers were interested in the varying activity of these drugs at the type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.

For each 30-day interval, they categorized beneficiaries into four groups: a stimulating medication group (n = 4,879) consisting of individuals mostly taking stimulating antihypertensives; an inhibiting medication group (n = 10,303) that mostly included individuals prescribed this type of antihypertensive; a mixed group (n = 2,179) that included a combination of the first two classifications; and a nonuser group (n = 40,413) of individuals who were not using either type of drug.

The primary outcome was time to first occurrence of ADRD. The secondary outcome was time to first occurrence of vascular dementia.

Researchers controlled for cardiovascular risk factors and sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and receipt of low-income subsidy.

Unanswered questions

After adjustments, results showed that initiation of an antihypertensive medication regimen that exclusively stimulates, rather than inhibits, type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors was associated with a 16% lower risk for incident ADRD over a follow-up of just under 7 years (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.90; P < .001).

The mixed regimen was also associated with statistically significant (P = .001) reduced odds of ADRD compared with the inhibiting medications.

As for vascular dementia, use of stimulating vs. inhibiting medications was associated with an 18% lower risk (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.96; P = .02).

Again, use of the mixed regimen was associated with reduced risk of vascular dementia compared with the inhibiting medications (P = .03).

A variety of potential mechanisms might explain the superiority of stimulating agents when it comes to dementia risk, said Dr. Marcum. These could include, for example, increased blood flow to the brain and reduced amyloid.

“But more mechanistic work is needed as well as evaluation of dose responses, because that’s not something we looked at in this study,” Dr. Marcum said. “There are still a lot of unanswered questions.”

Stimulators instead of inhibitors?

The results of the current analysis come on the heels of some previous work showing the benefits of lowering blood pressure. For example, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) showed that targeting a systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg significantly reduces risk for heart disease, stroke, and death from these diseases.

But in contrast to previous research, the current study included only beneficiaries with incident hypertension and new use of antihypertensive medications, and it adjusted for time-varying confounding.

Prescribing stimulating instead of inhibiting treatments could make a difference at the population level, Dr. Marcum noted.

“If we could shift the prescribing a little bit from inhibiting to stimulating, that could possibly reduce dementia risk,” he said.

However, “we’re not suggesting [that all patients] have their regimen switched,” he added.

That’s because inhibiting medications still have an important place in the antihypertensive treatment armamentarium, Dr. Marcum noted. As an example, beta-blockers are used post heart attack.

As well, factors such as cost and side effects should be taken into consideration when prescribing an antihypertensive drug.

The new results could be used to set up a comparison in a future randomized controlled trial that would provide the strongest evidence for estimating causal effects of treatments, said Dr. Marcum.

‘More convincing’

Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study is “more convincing” than previous related research, as it has a larger sample size and a longer follow-up.

“And the exquisite statistical analysis gives more robustness, more solidity, to the hypothesis that drugs that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors might be protective for dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego, who was not involved with the research.

However, he noted that the retrospective study had some limitations, including the underdiagnosis of dementia. “The diagnosis of dementia is, honestly, very poorly done in the clinical setting,” he said.

As well, the study could be subject to “confounding by indication,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said. “There could be a third variable, another confounding factor, that’s responsible both for the dementia and for the prescription of these drugs,” he added.

For example, he noted that comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and heart failure might increase the risk of dementia.

He agreed with the investigators that a randomized clinical trial would address these limitations. “All comorbidities would be equally shared” in the randomized groups, and all participants would be given “a specific test for dementia at the same time,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said.

Still, he noted that the new results are in keeping with hypertension guidelines that recommend stimulating drugs.

“This trial definitely shows that the current hypertension guidelines are good treatment for our patients, not only to control blood pressure and not only to prevent infarction to prevent stroke but also to prevent dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego.

Also commenting for this news organization, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the new data provide “clarity” on why previous research had differing results on the effect of antihypertensives on cognition.

Among the caveats of this new analysis is that “it’s unclear if the demographics in this study are fully representative of Medicare beneficiaries,” said Dr. Snyder.

She, too, said a clinical trial is important “to understand if there is a preventative and/or treatment potential in the medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.”

The study received funding from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcum and Dr. Santos-Gallego have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antihypertensive medications that stimulate rather than inhibit type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors can lower the rate of dementia among new users of these medications, new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 57,000 older Medicare beneficiaries showed that the initiation of antihypertensives that stimulate the receptors was linked to a 16% lower risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD) and an 18% lower risk for vascular dementia compared with those that inhibit the receptors.

“Achieving appropriate blood pressure control is essential for maximizing brain health, and this promising research suggests certain antihypertensives could yield brain benefit compared to others,” lead study author Zachary A. Marcum, PharmD, PhD, associate professor, University of Washington School of Pharmacy, Seattle, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Medicare beneficiaries

Previous observational studies showed that antihypertensive medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, in comparison with those that don’t, were associated with lower rates of dementia. However, those studies included individuals with prevalent hypertension and were relatively small.

The new retrospective cohort study included a random sample of 57,773 Medicare beneficiaries aged at least 65 years with new-onset hypertension. The mean age of participants was 73.8 years, 62.9% were women, and 86.9% were White.

Over the course of the study, some participants filled at least one prescription for a stimulating angiotensin II receptor type 2 and 4, such as angiotensin II receptor type 1 blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.

Others participants filled a prescription for an inhibiting type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

“All these medications lower blood pressure, but they do it in different ways,” said Dr. Marcum.

The researchers were interested in the varying activity of these drugs at the type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.

For each 30-day interval, they categorized beneficiaries into four groups: a stimulating medication group (n = 4,879) consisting of individuals mostly taking stimulating antihypertensives; an inhibiting medication group (n = 10,303) that mostly included individuals prescribed this type of antihypertensive; a mixed group (n = 2,179) that included a combination of the first two classifications; and a nonuser group (n = 40,413) of individuals who were not using either type of drug.

The primary outcome was time to first occurrence of ADRD. The secondary outcome was time to first occurrence of vascular dementia.

Researchers controlled for cardiovascular risk factors and sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and receipt of low-income subsidy.

Unanswered questions

After adjustments, results showed that initiation of an antihypertensive medication regimen that exclusively stimulates, rather than inhibits, type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors was associated with a 16% lower risk for incident ADRD over a follow-up of just under 7 years (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.90; P < .001).

The mixed regimen was also associated with statistically significant (P = .001) reduced odds of ADRD compared with the inhibiting medications.

As for vascular dementia, use of stimulating vs. inhibiting medications was associated with an 18% lower risk (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.96; P = .02).

Again, use of the mixed regimen was associated with reduced risk of vascular dementia compared with the inhibiting medications (P = .03).

A variety of potential mechanisms might explain the superiority of stimulating agents when it comes to dementia risk, said Dr. Marcum. These could include, for example, increased blood flow to the brain and reduced amyloid.

“But more mechanistic work is needed as well as evaluation of dose responses, because that’s not something we looked at in this study,” Dr. Marcum said. “There are still a lot of unanswered questions.”

Stimulators instead of inhibitors?

The results of the current analysis come on the heels of some previous work showing the benefits of lowering blood pressure. For example, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) showed that targeting a systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg significantly reduces risk for heart disease, stroke, and death from these diseases.

But in contrast to previous research, the current study included only beneficiaries with incident hypertension and new use of antihypertensive medications, and it adjusted for time-varying confounding.

Prescribing stimulating instead of inhibiting treatments could make a difference at the population level, Dr. Marcum noted.

“If we could shift the prescribing a little bit from inhibiting to stimulating, that could possibly reduce dementia risk,” he said.

However, “we’re not suggesting [that all patients] have their regimen switched,” he added.

That’s because inhibiting medications still have an important place in the antihypertensive treatment armamentarium, Dr. Marcum noted. As an example, beta-blockers are used post heart attack.

As well, factors such as cost and side effects should be taken into consideration when prescribing an antihypertensive drug.

The new results could be used to set up a comparison in a future randomized controlled trial that would provide the strongest evidence for estimating causal effects of treatments, said Dr. Marcum.

‘More convincing’

Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study is “more convincing” than previous related research, as it has a larger sample size and a longer follow-up.

“And the exquisite statistical analysis gives more robustness, more solidity, to the hypothesis that drugs that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors might be protective for dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego, who was not involved with the research.

However, he noted that the retrospective study had some limitations, including the underdiagnosis of dementia. “The diagnosis of dementia is, honestly, very poorly done in the clinical setting,” he said.

As well, the study could be subject to “confounding by indication,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said. “There could be a third variable, another confounding factor, that’s responsible both for the dementia and for the prescription of these drugs,” he added.

For example, he noted that comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and heart failure might increase the risk of dementia.

He agreed with the investigators that a randomized clinical trial would address these limitations. “All comorbidities would be equally shared” in the randomized groups, and all participants would be given “a specific test for dementia at the same time,” Dr. Santos-Gallego said.

Still, he noted that the new results are in keeping with hypertension guidelines that recommend stimulating drugs.

“This trial definitely shows that the current hypertension guidelines are good treatment for our patients, not only to control blood pressure and not only to prevent infarction to prevent stroke but also to prevent dementia,” said Dr. Santos-Gallego.

Also commenting for this news organization, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the new data provide “clarity” on why previous research had differing results on the effect of antihypertensives on cognition.

Among the caveats of this new analysis is that “it’s unclear if the demographics in this study are fully representative of Medicare beneficiaries,” said Dr. Snyder.

She, too, said a clinical trial is important “to understand if there is a preventative and/or treatment potential in the medications that stimulate type 2 and 4 angiotensin II receptors.”

The study received funding from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcum and Dr. Santos-Gallego have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Spikes out: A COVID mystery

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

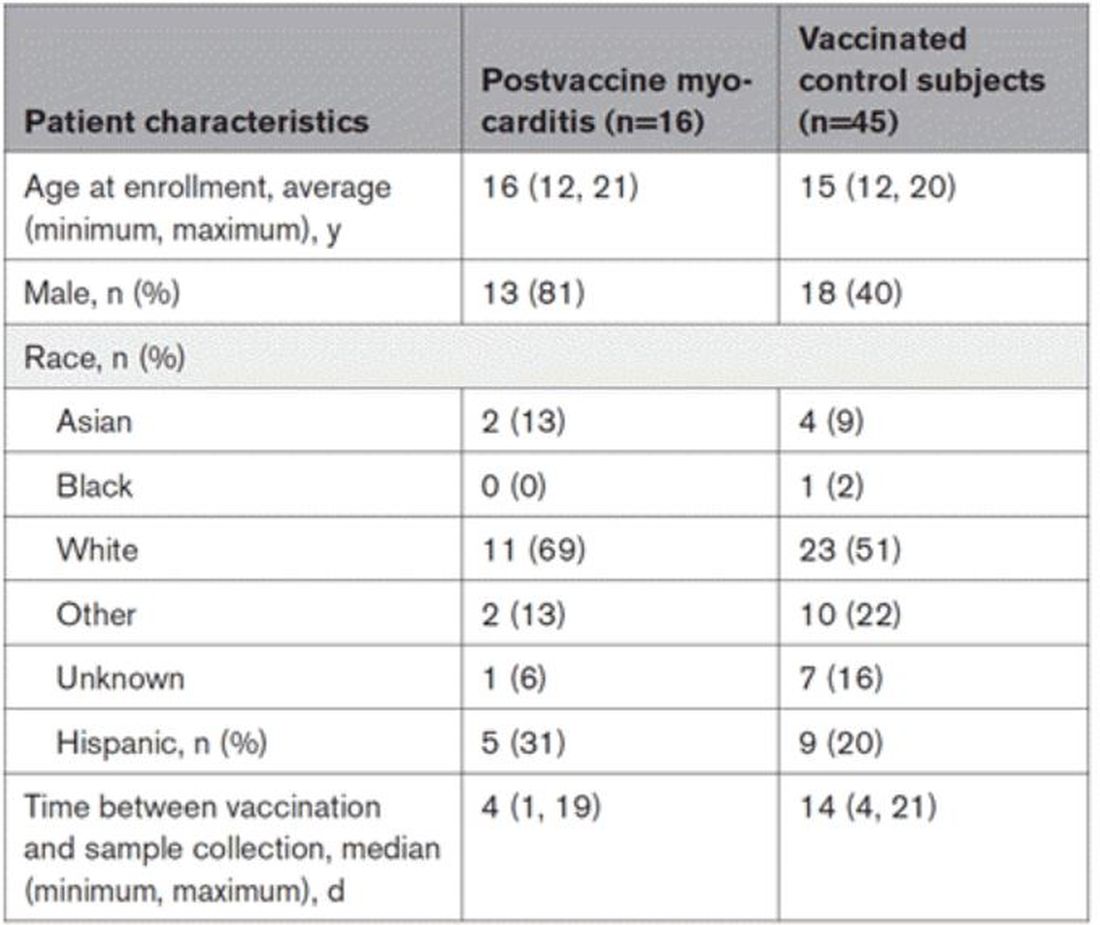

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study spotlights clinicopathologic features, survival outcomes of pediatric melanoma

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.

The authors acknowledged certain limitation of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the small number of children. “Our data suggest that adolescent melanomas are often similar to adult-type melanomas, whilst those which occur in young children frequently occur via different molecular mechanisms,” they concluded. “In the future it is likely that further understanding of these molecular mechanisms and ability to classify melanomas based on their molecular characteristics will assist in further refining prognostic estimates and possible guiding treatment for young patients with melanoma.”

Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, assistant program director of the division of dermatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the analysis “greatly contributes to dermatology, as we are still learning the differences between melanoma in children and adolescents versus adults.

This study found that adolescents with melanoma had worse survival if mitosis were present and/or located on head/neck, which could aid in aggressiveness of treatment.”

A key strength of analysis, she continued, is the large sample size of 514 patients, “given that melanoma in this population is very rare. A limitation which [the researchers] brought up is the discrepancy of diagnosis via histopathology of melanoma in children versus adults. The study relied on the pathology report given the retrospective nature of this [analysis, and it] was based on Australian and Dutch populations, which may limit its scope in other countries.”

Dr. El Sharouni was supported by a research fellowship grant from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), while two of her coauthors, Richard A. Scolyer, MD, and John F. Thompson, MD, were recipients of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant. The study was also supported by a research program grant from Cancer Institute New South Wales. Dr. Thiede reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.

The authors acknowledged certain limitation of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the small number of children. “Our data suggest that adolescent melanomas are often similar to adult-type melanomas, whilst those which occur in young children frequently occur via different molecular mechanisms,” they concluded. “In the future it is likely that further understanding of these molecular mechanisms and ability to classify melanomas based on their molecular characteristics will assist in further refining prognostic estimates and possible guiding treatment for young patients with melanoma.”

Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, assistant program director of the division of dermatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the analysis “greatly contributes to dermatology, as we are still learning the differences between melanoma in children and adolescents versus adults.

This study found that adolescents with melanoma had worse survival if mitosis were present and/or located on head/neck, which could aid in aggressiveness of treatment.”

A key strength of analysis, she continued, is the large sample size of 514 patients, “given that melanoma in this population is very rare. A limitation which [the researchers] brought up is the discrepancy of diagnosis via histopathology of melanoma in children versus adults. The study relied on the pathology report given the retrospective nature of this [analysis, and it] was based on Australian and Dutch populations, which may limit its scope in other countries.”

Dr. El Sharouni was supported by a research fellowship grant from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), while two of her coauthors, Richard A. Scolyer, MD, and John F. Thompson, MD, were recipients of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant. The study was also supported by a research program grant from Cancer Institute New South Wales. Dr. Thiede reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.