User login

Clinical Guidelines Hub only

Poor cardiovascular health predicted cognitive impairment

Adults in poor cardiovascular health were more likely to develop cognitive problems such as learning and memory impairment, compared with healthier peers, according to a large prospective study published online June 11 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

But top scorers on the cardiovascular health (CVH) measure used in the study were not more protected against incident mental impairment than were intermediate scorers, reported Evan Thacker, Ph.D., of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and his associates.

"This pattern suggests that even intermediate levels of CVH are preferable to low levels of CVH," the investigators said. "This is an encouraging message for population health promotion, because intermediate CVH is a more realistic target than ideal CVH for many individuals."

The investigators used the American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7 score to classify the cardiovascular health of 17,761 black and white adults in the United States aged 45 years and older (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014 June 11 [doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000635]). Individuals were participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. The Six-Item Screener was used assess baseline global cognitive status; and a three-test measure of verbal learning, memory, and fluency was used to assess mental function at subsequent 2-year intervals. In all, 56% of individuals resided in "stroke belt" states, including Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee, the investigators said. All study participants had normal cognitive function and no stroke history at the outset.

After adjustment for age, sex, race, and education, 4.6% of individuals with the worst CVH scores developed cognitive impairment after baseline (95% confidence interval, 4.0%-5.2%), compared with only 2.7% of those with intermediate scores (95% CI, 2.3%-3.1%) and 2.6% of those with the best scores (95% CI, 2.1%-3.1%), Dr. Thacker and his associates reported. Therefore, the odds of incident cognitive impairment were 35%-37% lower in the intermediate- and high-CVH groups than in the low-CVH group, the researchers added (odds ratios, 0.65 and 0.63; 95% CIs, 0.52-0.81 and 0.51-0.79, respectively).

"Rather than a dose-response pattern across the range of Life’s Simple 7 scores, we observed that associations with [incident clinical impairment] were the same for the highest tertile of Life’s Simple 7 score and the middle tertile, relative to the lowest tertile," the researchers wrote. "Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the AHA’s strategic efforts to improve CVH from poor to intermediate or higher levels could lead to reductions in cognitive decline, and we believe further research addressing this hypothesis is warranted."

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Adults in poor cardiovascular health were more likely to develop cognitive problems such as learning and memory impairment, compared with healthier peers, according to a large prospective study published online June 11 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

But top scorers on the cardiovascular health (CVH) measure used in the study were not more protected against incident mental impairment than were intermediate scorers, reported Evan Thacker, Ph.D., of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and his associates.

"This pattern suggests that even intermediate levels of CVH are preferable to low levels of CVH," the investigators said. "This is an encouraging message for population health promotion, because intermediate CVH is a more realistic target than ideal CVH for many individuals."

The investigators used the American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7 score to classify the cardiovascular health of 17,761 black and white adults in the United States aged 45 years and older (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014 June 11 [doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000635]). Individuals were participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. The Six-Item Screener was used assess baseline global cognitive status; and a three-test measure of verbal learning, memory, and fluency was used to assess mental function at subsequent 2-year intervals. In all, 56% of individuals resided in "stroke belt" states, including Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee, the investigators said. All study participants had normal cognitive function and no stroke history at the outset.

After adjustment for age, sex, race, and education, 4.6% of individuals with the worst CVH scores developed cognitive impairment after baseline (95% confidence interval, 4.0%-5.2%), compared with only 2.7% of those with intermediate scores (95% CI, 2.3%-3.1%) and 2.6% of those with the best scores (95% CI, 2.1%-3.1%), Dr. Thacker and his associates reported. Therefore, the odds of incident cognitive impairment were 35%-37% lower in the intermediate- and high-CVH groups than in the low-CVH group, the researchers added (odds ratios, 0.65 and 0.63; 95% CIs, 0.52-0.81 and 0.51-0.79, respectively).

"Rather than a dose-response pattern across the range of Life’s Simple 7 scores, we observed that associations with [incident clinical impairment] were the same for the highest tertile of Life’s Simple 7 score and the middle tertile, relative to the lowest tertile," the researchers wrote. "Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the AHA’s strategic efforts to improve CVH from poor to intermediate or higher levels could lead to reductions in cognitive decline, and we believe further research addressing this hypothesis is warranted."

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Adults in poor cardiovascular health were more likely to develop cognitive problems such as learning and memory impairment, compared with healthier peers, according to a large prospective study published online June 11 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

But top scorers on the cardiovascular health (CVH) measure used in the study were not more protected against incident mental impairment than were intermediate scorers, reported Evan Thacker, Ph.D., of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and his associates.

"This pattern suggests that even intermediate levels of CVH are preferable to low levels of CVH," the investigators said. "This is an encouraging message for population health promotion, because intermediate CVH is a more realistic target than ideal CVH for many individuals."

The investigators used the American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7 score to classify the cardiovascular health of 17,761 black and white adults in the United States aged 45 years and older (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014 June 11 [doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000635]). Individuals were participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. The Six-Item Screener was used assess baseline global cognitive status; and a three-test measure of verbal learning, memory, and fluency was used to assess mental function at subsequent 2-year intervals. In all, 56% of individuals resided in "stroke belt" states, including Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee, the investigators said. All study participants had normal cognitive function and no stroke history at the outset.

After adjustment for age, sex, race, and education, 4.6% of individuals with the worst CVH scores developed cognitive impairment after baseline (95% confidence interval, 4.0%-5.2%), compared with only 2.7% of those with intermediate scores (95% CI, 2.3%-3.1%) and 2.6% of those with the best scores (95% CI, 2.1%-3.1%), Dr. Thacker and his associates reported. Therefore, the odds of incident cognitive impairment were 35%-37% lower in the intermediate- and high-CVH groups than in the low-CVH group, the researchers added (odds ratios, 0.65 and 0.63; 95% CIs, 0.52-0.81 and 0.51-0.79, respectively).

"Rather than a dose-response pattern across the range of Life’s Simple 7 scores, we observed that associations with [incident clinical impairment] were the same for the highest tertile of Life’s Simple 7 score and the middle tertile, relative to the lowest tertile," the researchers wrote. "Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the AHA’s strategic efforts to improve CVH from poor to intermediate or higher levels could lead to reductions in cognitive decline, and we believe further research addressing this hypothesis is warranted."

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Intermediate or high cardiovascular health can lower the risk of cognitive impairment, compared with low CVH.

Major finding: The odds of incident cognitive impairment were 35%-37% lower in individuals with intermediate and high CVH scores than in individuals with the worst scores.

Data source: Prospective observational cohort study of 17,761 individuals aged 45 years and older with normal cognitive function and no stroke history at outset.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Hepatitis B screening recommended for high-risk patients

Physicians should screen all asymptomatic but high-risk adolescents and adults for hepatitis B virus infection, according to an updated recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that was published online May 27 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Since the last USPSTF recommendation on HBV screening in 2004, which focused on the general population and didn’t advocate screening of this subset of patients, research has documented that antiviral treatment improves both intermediate outcomes such as virologic and histologic responses and long-term outcomes such as prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease.

Given this effectiveness, along with the 98% sensitivity and specificity of HBV screening tests, the group has now issued a level B recommendation that high-risk patients be screened, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the USPSTF and professor of family and community medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

High-risk patients include the following:

• People born in regions where the prevalence of HBV infection is 2% or greater, such as sub-Saharan Africa, central and southeast Asia, China, the Pacific Islands, and parts of Latin America. People born in these areas account for 47%-95% of the chronic HBV infection in the United States.

• American-born children of parents from these regions, who may not have been vaccinated in infancy.

• HIV-positive persons.

• IV-drug users.

• Household contacts of people with HBV infection.

• Men who have sex with men.

The updated USPSTF recommendations are in line with those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Institute of Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The CDC additionally recommends HBV screening for blood, organ, or tissue donors; people with occupational or other exposure to infectious blood or body fluids; and patients receiving hemodialysis, cytotoxic therapy, or immunosuppressive therapy.

The USPSTF still does not recommend HBV screening for the general population. The prevalence of the infection is low in the U.S. general population, and most members of the general population who are infected with HBV do not develop the chronic form of the infection and do not develop complications like hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis. The potential harms of general screening, then, probably exceed the potential benefits, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted (Ann Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1018]).

The USPSTF has separate recommendations regarding hepatitis B in pregnant women. These, along with the updated recommendations for high-risk patients, are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The USPSTF is a voluntary group funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality but otherwise independent of the federal government. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

These "long overdue" recommendations are "a dramatic and welcome upgrade from the 2004 USPSTF guidelines, which issued a grade D recommendation against screening asymptomatic persons for HBV infection," said Dr. Ruma Rajbhandari and Dr. Raymond T. Chung.

"Many would argue that the USPSTF should have endorsed screening for HBV infection in high-risk populations a decade ago," they wrote. The group lagged far behind the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ recommendations in 2001 and the CDC’s recommendations in 2005. "We may have thus missed an opportunity to screen many high-risk persons in the United States," Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung said.

The USPSTF update "would be more useful if they provided a clearer definition of the high-risk patient. ... We worry that busy generalist clinicians do not have the time to estimate their patients’ risks for HBV infection." Physicians may find it more helpful to look up the CDC’s table listing all the factors that render a patient high risk, they added.

Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung are with the liver center and gastrointestinal division at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Lefevre’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1153]).

These "long overdue" recommendations are "a dramatic and welcome upgrade from the 2004 USPSTF guidelines, which issued a grade D recommendation against screening asymptomatic persons for HBV infection," said Dr. Ruma Rajbhandari and Dr. Raymond T. Chung.

"Many would argue that the USPSTF should have endorsed screening for HBV infection in high-risk populations a decade ago," they wrote. The group lagged far behind the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ recommendations in 2001 and the CDC’s recommendations in 2005. "We may have thus missed an opportunity to screen many high-risk persons in the United States," Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung said.

The USPSTF update "would be more useful if they provided a clearer definition of the high-risk patient. ... We worry that busy generalist clinicians do not have the time to estimate their patients’ risks for HBV infection." Physicians may find it more helpful to look up the CDC’s table listing all the factors that render a patient high risk, they added.

Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung are with the liver center and gastrointestinal division at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Lefevre’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1153]).

These "long overdue" recommendations are "a dramatic and welcome upgrade from the 2004 USPSTF guidelines, which issued a grade D recommendation against screening asymptomatic persons for HBV infection," said Dr. Ruma Rajbhandari and Dr. Raymond T. Chung.

"Many would argue that the USPSTF should have endorsed screening for HBV infection in high-risk populations a decade ago," they wrote. The group lagged far behind the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ recommendations in 2001 and the CDC’s recommendations in 2005. "We may have thus missed an opportunity to screen many high-risk persons in the United States," Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung said.

The USPSTF update "would be more useful if they provided a clearer definition of the high-risk patient. ... We worry that busy generalist clinicians do not have the time to estimate their patients’ risks for HBV infection." Physicians may find it more helpful to look up the CDC’s table listing all the factors that render a patient high risk, they added.

Dr. Rajbhandari and Dr. Chung are with the liver center and gastrointestinal division at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. They reported no relevant conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Lefevre’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1153]).

Physicians should screen all asymptomatic but high-risk adolescents and adults for hepatitis B virus infection, according to an updated recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that was published online May 27 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Since the last USPSTF recommendation on HBV screening in 2004, which focused on the general population and didn’t advocate screening of this subset of patients, research has documented that antiviral treatment improves both intermediate outcomes such as virologic and histologic responses and long-term outcomes such as prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease.

Given this effectiveness, along with the 98% sensitivity and specificity of HBV screening tests, the group has now issued a level B recommendation that high-risk patients be screened, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the USPSTF and professor of family and community medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

High-risk patients include the following:

• People born in regions where the prevalence of HBV infection is 2% or greater, such as sub-Saharan Africa, central and southeast Asia, China, the Pacific Islands, and parts of Latin America. People born in these areas account for 47%-95% of the chronic HBV infection in the United States.

• American-born children of parents from these regions, who may not have been vaccinated in infancy.

• HIV-positive persons.

• IV-drug users.

• Household contacts of people with HBV infection.

• Men who have sex with men.

The updated USPSTF recommendations are in line with those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Institute of Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The CDC additionally recommends HBV screening for blood, organ, or tissue donors; people with occupational or other exposure to infectious blood or body fluids; and patients receiving hemodialysis, cytotoxic therapy, or immunosuppressive therapy.

The USPSTF still does not recommend HBV screening for the general population. The prevalence of the infection is low in the U.S. general population, and most members of the general population who are infected with HBV do not develop the chronic form of the infection and do not develop complications like hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis. The potential harms of general screening, then, probably exceed the potential benefits, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted (Ann Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1018]).

The USPSTF has separate recommendations regarding hepatitis B in pregnant women. These, along with the updated recommendations for high-risk patients, are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The USPSTF is a voluntary group funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality but otherwise independent of the federal government. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

Physicians should screen all asymptomatic but high-risk adolescents and adults for hepatitis B virus infection, according to an updated recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that was published online May 27 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Since the last USPSTF recommendation on HBV screening in 2004, which focused on the general population and didn’t advocate screening of this subset of patients, research has documented that antiviral treatment improves both intermediate outcomes such as virologic and histologic responses and long-term outcomes such as prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease.

Given this effectiveness, along with the 98% sensitivity and specificity of HBV screening tests, the group has now issued a level B recommendation that high-risk patients be screened, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the USPSTF and professor of family and community medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

High-risk patients include the following:

• People born in regions where the prevalence of HBV infection is 2% or greater, such as sub-Saharan Africa, central and southeast Asia, China, the Pacific Islands, and parts of Latin America. People born in these areas account for 47%-95% of the chronic HBV infection in the United States.

• American-born children of parents from these regions, who may not have been vaccinated in infancy.

• HIV-positive persons.

• IV-drug users.

• Household contacts of people with HBV infection.

• Men who have sex with men.

The updated USPSTF recommendations are in line with those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Institute of Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The CDC additionally recommends HBV screening for blood, organ, or tissue donors; people with occupational or other exposure to infectious blood or body fluids; and patients receiving hemodialysis, cytotoxic therapy, or immunosuppressive therapy.

The USPSTF still does not recommend HBV screening for the general population. The prevalence of the infection is low in the U.S. general population, and most members of the general population who are infected with HBV do not develop the chronic form of the infection and do not develop complications like hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis. The potential harms of general screening, then, probably exceed the potential benefits, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted (Ann Intern. Med. 2014 May 27 [doi:10.7326/M14-1018]).

The USPSTF has separate recommendations regarding hepatitis B in pregnant women. These, along with the updated recommendations for high-risk patients, are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The USPSTF is a voluntary group funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality but otherwise independent of the federal government. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: HBV screening is appropriate in all at-risk populations.

Major finding: Physicians should screen all adolescents and adults at high risk for HBV infection, including those born in regions where the virus is endemic, American-born children of such parents, household contacts of people with HBV, people with HIV, IV-drug users, and men who have sex with men.

Data source: A comprehensive review of the literature since 2004 regarding the benefits and harms of screening high-risk patients for HBV infection, and a compilation of recommendations for screening high-risk patients.

Disclosures: The USPSTF is a voluntary group funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality but otherwise independent of the federal government. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: AACE/ACE introduce new obesity diagnosis framework

LAS VEGAS —Your patient’s body mass index indicates obesity. Now, what’s the course of action?

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology are aiming to address this gap in diagnosis and treatment of obesity through a new framework.

The four-step approach starts with BMI measurement, then clinical assessment, complication staging, and finally treatment.

In a video interview, Dr. W. Timothy Garvey, chair of the AACE Obesity Scientific Committee, explained why the new framework is important and how physicians can apply it to their practice at the AACE annual meeting.

The document, or advanced framework, is in its last stages of completion.

Twitter: @naseemmiller

LAS VEGAS —Your patient’s body mass index indicates obesity. Now, what’s the course of action?

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology are aiming to address this gap in diagnosis and treatment of obesity through a new framework.

The four-step approach starts with BMI measurement, then clinical assessment, complication staging, and finally treatment.

In a video interview, Dr. W. Timothy Garvey, chair of the AACE Obesity Scientific Committee, explained why the new framework is important and how physicians can apply it to their practice at the AACE annual meeting.

The document, or advanced framework, is in its last stages of completion.

Twitter: @naseemmiller

LAS VEGAS —Your patient’s body mass index indicates obesity. Now, what’s the course of action?

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology are aiming to address this gap in diagnosis and treatment of obesity through a new framework.

The four-step approach starts with BMI measurement, then clinical assessment, complication staging, and finally treatment.

In a video interview, Dr. W. Timothy Garvey, chair of the AACE Obesity Scientific Committee, explained why the new framework is important and how physicians can apply it to their practice at the AACE annual meeting.

The document, or advanced framework, is in its last stages of completion.

Twitter: @naseemmiller

AACAP disagrees with marijuana legalization, cites harmful effects on children

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has released a policy opposing efforts to legalize marijuana.

The AACAP policy statement, released April 15, opposes marijuana legalization while supporting initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of marijuana’s effects on adolescents and improving access to evidence-based treatment, rather than focusing on criminal charges for adolescent users. AACAP also supports the careful monitoring of marijuana-related policy changes on the mental health of children and adolescents.

The policy stresses that significant early use of the drug is associated with increased incidence and worsened psychotic, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders "across the lifespan." In addition, one in six adolescent marijuana users develops cannabis use disorder, a syndrome involving tolerance, withdrawal, and continued marijuana use despite significant associated impairments.

"Often lost in the discussion on marijuana are the concerning potential implications of policy changes on children and adolescents, who are particularly vulnerable to marijuana’s adverse effects," Dr. Kevin Gray, cochair of AACAP’s Substance Abuse and Addiction Committee, said in a statement. "With this in mind, AACAP felt it was critically important to communicate our organization’s position, given our role as advocates for children and adolescent mental health."

ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk equations get a thumbs-up

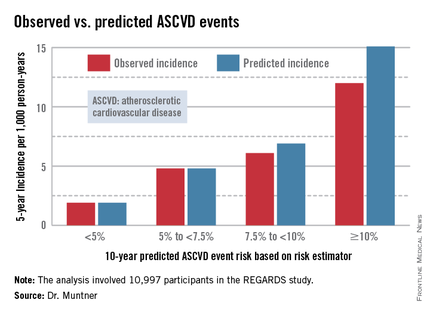

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

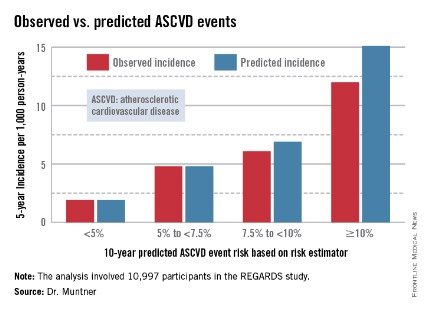

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

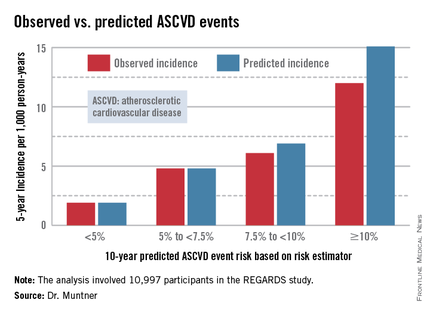

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

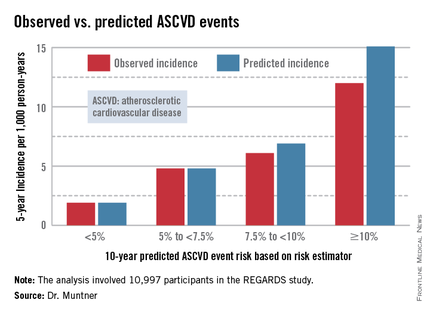

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

AT ACC 14

Major finding: The controversial cardiovascular risk equations at the heart of the latest ACC/AHA risk-assessment guidelines turned in a moderate to good performance in a validation study involving nearly 11,000 participants in a large, observational, prospective study.

Data source: The REGARDS study is a population-based study in which more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients are being followed prospectively.

Disclosures: The analysis was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Draft recommendations back aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Novel anticoagulants get nod in new AF guidelines

New guidelines for managing patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation recommend dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, as well as warfarin, and call on physicians to use a more comprehensive stroke risk calculator.

"I think physicians are still learning how to use the newer anticoagulants, and this is something that will require time," said Dr. Craig T. January, chair of the AF guidelines committee, assembled by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

The guidelines, published in Circulation and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, focus on nonvalvular AF and feature a detailed dosing chart organized by anticoagulant type and renal function, which is impaired in up to 20% of those with AF.

"The goal was to create a straightforward chart on how to use these drugs," said Dr. January, a clinician/scientist with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are not recommended for AF patients with nonvalvular disease and end-stage kidney disease, either on or off dialysis, because of a lack of evidence from clinical trials regarding the balance of risks and benefits.

No recommendation was made for apixaban (Eliquis) in patients with severe or end-stage renal impairment, because of a lack of published data, although a recent secondary analysis of the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial suggests the direct factor Xa inhibitor provides the greatest reduction in major bleeding in patients with impaired renal function compared with warfarin (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2821-30).

The guidelines advise clinicians to evaluate renal function prior to initiating any of the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors, and to reevaluate at least annually and when clinically indicated.

Previously, warfarin (Coumadin) was the only recommended anticoagulant in the 2006 guidelines. It’s admittedly cheaper, but the guidelines note that the novel anticoagulants eliminate dietary limitations and the need for repeated international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring, and have more predictable pharmacological profiles and fewer drug-drug interactions.

The oral agents have revolutionized the treatment of AF since entering the market in the past few years, but by no means replace warfarin.

For patients with nonvalvular AF who are well controlled and satisfied with warfarin therapy, the guidelines say, "It is not necessary to change to one of the newer agents," Dr. January observed.

Warfarin should also be used for valvular AF to manage patients with a mechanical heart valve or hemodynamically significant mitral stenosis because these populations were excluded from all three major trials – RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate), ROCKET-AF (An Efficacy and Safety Study of Rivaroxaban With Warfarin for the Prevention of Stroke and Non-Central Nervous System Systemic Embolism in Patients With Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation), and ARISTOTLE – that led to the approval of the newer anticoagulants.

Dabigatran is specifically not recommended for patients with a mechanical valve because of the potential for harm, which was recently recognized by the Food and Drug Administration.

The document includes a section on dose interruption and bridging therapy, which in part reflects the fact that the new oral agents carry a black box warning from the FDA because discontinuation can increase the risk of thromboembolism. In addition, reversal agents are in development, but they are not currently available should immediate reversal be needed.

The new recommendations will elicit discussion, but are not expected to be controversial like the updated cholesterol management guidelines recently released by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, Dr. January said.

Another noteworthy change is the diminished use of aspirin in preventing stroke. "Most of the published data have shown that aspirin is not as effective as full anticoagulation and that aspirin itself in many trials has little benefit. This was a point of a lot of discussion in the committee," he said.

To calculate stroke risk, the guidelines recommend that clinicians use the CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 or older (doubled), Diabetes mellitus, Prior Stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (doubled), Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category female) calculator because it has a broader score range (0 to 9) and includes a larger number of risk factors than the older CHADS2 score.

"What the CHA2DS2-VASc provides is better discrimination for patients at the lower end of risk," Dr. January said. "I think there was uniform agreement in the committee that the CHA2DS2-VASc was the preferred risk calculator and that we should move on from the CHADS2 score.

"The CHA2DS2-VASc score is an interesting score because, depending on how you implement it, women can never have a score of zero," he added. "In fact, there are data out of Europe in the last year that the risk of stroke in women [with AF] is really quite low for those under 65."

As with the 2006 guidelines, the new document emphasizes an increased role for using radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of AF. This reflects the continued evolution of the technology as an AF therapy, Dr. January said. As a result, RF ablation will be increasingly used for AF treatment, particularly in symptomatic patients.

The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society without commercial support. Dr. January and his coauthors reported no relevant industry relationships.

New guidelines for managing patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation recommend dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, as well as warfarin, and call on physicians to use a more comprehensive stroke risk calculator.

"I think physicians are still learning how to use the newer anticoagulants, and this is something that will require time," said Dr. Craig T. January, chair of the AF guidelines committee, assembled by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

The guidelines, published in Circulation and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, focus on nonvalvular AF and feature a detailed dosing chart organized by anticoagulant type and renal function, which is impaired in up to 20% of those with AF.

"The goal was to create a straightforward chart on how to use these drugs," said Dr. January, a clinician/scientist with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are not recommended for AF patients with nonvalvular disease and end-stage kidney disease, either on or off dialysis, because of a lack of evidence from clinical trials regarding the balance of risks and benefits.

No recommendation was made for apixaban (Eliquis) in patients with severe or end-stage renal impairment, because of a lack of published data, although a recent secondary analysis of the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial suggests the direct factor Xa inhibitor provides the greatest reduction in major bleeding in patients with impaired renal function compared with warfarin (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2821-30).

The guidelines advise clinicians to evaluate renal function prior to initiating any of the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors, and to reevaluate at least annually and when clinically indicated.

Previously, warfarin (Coumadin) was the only recommended anticoagulant in the 2006 guidelines. It’s admittedly cheaper, but the guidelines note that the novel anticoagulants eliminate dietary limitations and the need for repeated international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring, and have more predictable pharmacological profiles and fewer drug-drug interactions.

The oral agents have revolutionized the treatment of AF since entering the market in the past few years, but by no means replace warfarin.

For patients with nonvalvular AF who are well controlled and satisfied with warfarin therapy, the guidelines say, "It is not necessary to change to one of the newer agents," Dr. January observed.

Warfarin should also be used for valvular AF to manage patients with a mechanical heart valve or hemodynamically significant mitral stenosis because these populations were excluded from all three major trials – RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate), ROCKET-AF (An Efficacy and Safety Study of Rivaroxaban With Warfarin for the Prevention of Stroke and Non-Central Nervous System Systemic Embolism in Patients With Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation), and ARISTOTLE – that led to the approval of the newer anticoagulants.

Dabigatran is specifically not recommended for patients with a mechanical valve because of the potential for harm, which was recently recognized by the Food and Drug Administration.

The document includes a section on dose interruption and bridging therapy, which in part reflects the fact that the new oral agents carry a black box warning from the FDA because discontinuation can increase the risk of thromboembolism. In addition, reversal agents are in development, but they are not currently available should immediate reversal be needed.

The new recommendations will elicit discussion, but are not expected to be controversial like the updated cholesterol management guidelines recently released by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, Dr. January said.

Another noteworthy change is the diminished use of aspirin in preventing stroke. "Most of the published data have shown that aspirin is not as effective as full anticoagulation and that aspirin itself in many trials has little benefit. This was a point of a lot of discussion in the committee," he said.

To calculate stroke risk, the guidelines recommend that clinicians use the CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 or older (doubled), Diabetes mellitus, Prior Stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (doubled), Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category female) calculator because it has a broader score range (0 to 9) and includes a larger number of risk factors than the older CHADS2 score.

"What the CHA2DS2-VASc provides is better discrimination for patients at the lower end of risk," Dr. January said. "I think there was uniform agreement in the committee that the CHA2DS2-VASc was the preferred risk calculator and that we should move on from the CHADS2 score.

"The CHA2DS2-VASc score is an interesting score because, depending on how you implement it, women can never have a score of zero," he added. "In fact, there are data out of Europe in the last year that the risk of stroke in women [with AF] is really quite low for those under 65."

As with the 2006 guidelines, the new document emphasizes an increased role for using radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of AF. This reflects the continued evolution of the technology as an AF therapy, Dr. January said. As a result, RF ablation will be increasingly used for AF treatment, particularly in symptomatic patients.

The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society without commercial support. Dr. January and his coauthors reported no relevant industry relationships.

New guidelines for managing patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation recommend dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, as well as warfarin, and call on physicians to use a more comprehensive stroke risk calculator.

"I think physicians are still learning how to use the newer anticoagulants, and this is something that will require time," said Dr. Craig T. January, chair of the AF guidelines committee, assembled by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society.

The guidelines, published in Circulation and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, focus on nonvalvular AF and feature a detailed dosing chart organized by anticoagulant type and renal function, which is impaired in up to 20% of those with AF.

"The goal was to create a straightforward chart on how to use these drugs," said Dr. January, a clinician/scientist with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are not recommended for AF patients with nonvalvular disease and end-stage kidney disease, either on or off dialysis, because of a lack of evidence from clinical trials regarding the balance of risks and benefits.

No recommendation was made for apixaban (Eliquis) in patients with severe or end-stage renal impairment, because of a lack of published data, although a recent secondary analysis of the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial suggests the direct factor Xa inhibitor provides the greatest reduction in major bleeding in patients with impaired renal function compared with warfarin (Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:2821-30).

The guidelines advise clinicians to evaluate renal function prior to initiating any of the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors, and to reevaluate at least annually and when clinically indicated.

Previously, warfarin (Coumadin) was the only recommended anticoagulant in the 2006 guidelines. It’s admittedly cheaper, but the guidelines note that the novel anticoagulants eliminate dietary limitations and the need for repeated international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring, and have more predictable pharmacological profiles and fewer drug-drug interactions.

The oral agents have revolutionized the treatment of AF since entering the market in the past few years, but by no means replace warfarin.

For patients with nonvalvular AF who are well controlled and satisfied with warfarin therapy, the guidelines say, "It is not necessary to change to one of the newer agents," Dr. January observed.

Warfarin should also be used for valvular AF to manage patients with a mechanical heart valve or hemodynamically significant mitral stenosis because these populations were excluded from all three major trials – RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate), ROCKET-AF (An Efficacy and Safety Study of Rivaroxaban With Warfarin for the Prevention of Stroke and Non-Central Nervous System Systemic Embolism in Patients With Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation), and ARISTOTLE – that led to the approval of the newer anticoagulants.

Dabigatran is specifically not recommended for patients with a mechanical valve because of the potential for harm, which was recently recognized by the Food and Drug Administration.

The document includes a section on dose interruption and bridging therapy, which in part reflects the fact that the new oral agents carry a black box warning from the FDA because discontinuation can increase the risk of thromboembolism. In addition, reversal agents are in development, but they are not currently available should immediate reversal be needed.

The new recommendations will elicit discussion, but are not expected to be controversial like the updated cholesterol management guidelines recently released by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, Dr. January said.

Another noteworthy change is the diminished use of aspirin in preventing stroke. "Most of the published data have shown that aspirin is not as effective as full anticoagulation and that aspirin itself in many trials has little benefit. This was a point of a lot of discussion in the committee," he said.

To calculate stroke risk, the guidelines recommend that clinicians use the CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 75 or older (doubled), Diabetes mellitus, Prior Stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (doubled), Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category female) calculator because it has a broader score range (0 to 9) and includes a larger number of risk factors than the older CHADS2 score.

"What the CHA2DS2-VASc provides is better discrimination for patients at the lower end of risk," Dr. January said. "I think there was uniform agreement in the committee that the CHA2DS2-VASc was the preferred risk calculator and that we should move on from the CHADS2 score.

"The CHA2DS2-VASc score is an interesting score because, depending on how you implement it, women can never have a score of zero," he added. "In fact, there are data out of Europe in the last year that the risk of stroke in women [with AF] is really quite low for those under 65."

As with the 2006 guidelines, the new document emphasizes an increased role for using radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of AF. This reflects the continued evolution of the technology as an AF therapy, Dr. January said. As a result, RF ablation will be increasingly used for AF treatment, particularly in symptomatic patients.

The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society without commercial support. Dr. January and his coauthors reported no relevant industry relationships.

FROM CIRCULATION

Data source: Expert opinion.

Disclosures: The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the ACC, AHA, and HRS without commercial support. Dr. January and his coauthors reported no relevant industry relationships.

Evidence needed on obesity definition, treatment, AACE declares

WASHINGTON – Obesity requires a medical definition that goes beyond gauging a person’s body mass index if cost-effective care is to be delivered in an integrated fashion, according to a consensus statement issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology.

"The definition of obesity as a disease is not perfect," Dr. W. Timothy Garvey, who chaired the AACE/ACE Obesity Consensus Conference, said in a media briefing. "We rely upon an [anthropometric] measure of body mass index, which is a measure of height versus weight, and there was consensus that this was ... divorced from the impact of weight gain on the health of the individual. This imprecision in our diagnosis of obesity was constraining us."

In 2013, the American Medical Association officially recognized obesity as a disease. Better codification of what actually constitutes "obesity, the disease," will allow a more integrated and effective approach to treating it, said Dr. Garvey, professor of medicine and chair of the department of nutrition sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. To do so, the AACE/ACE held an intensive, 2-day session that largely featured spontaneous discussions between panelists and audience members representing four specific obesity "pillars": biomedical, government and regulation, health industry and economics, and research and education sectors.

A constant theme across the sectors was the need for a definition of obesity that accounts for cultural differences, ethnicity, and the presence or absence of cardiometabolic markers of disease in persons who are overweight or obese.

The conference’s multidisciplined approach informed the consensus statement that obesity is a chronic disease that should be treated with the established AACE/ACE obesity algorithm and met with lifestyle interventions. The consensus statement also addressed our current "obesogenic" environment, which many participants said was created in part by the abundance of nonnutritious foods.

In an interview, Dr. Susan Kansagra, deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said that by working with local vendors and their suppliers, among other actions, her agency is focused on increasing access to more nutritious foods in neighborhoods across the city as a way to shape the food environment. "It’s not people who’ve changed over the past 30 years; it’s the environment," Dr. Kansagra said at the conference.

Also addressed by the consensus statement was the need for preventive care, particularly at the pediatric level, and more cohesive public awareness campaigns that could affect how private payers develop their reimbursement strategies. Audience member Dr. Robert Silverman, medical director of CIGNA Healthcare, said that payers would respond to the need for obesity care, but that what currently is missing is "a tie between the evidence and the complications [of obesity]."

"We learned that different stakeholders require different levels of evidence," AACE President Jeffrey I. Mechanick said in the media briefing. "So, we’re going to be able come up with a more efficient way to make recommendations about research so that private insurance carriers, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or regulatory agencies have the type of data they require to facilitate the action [they need]."

These differences were brought to light during the conference as various audience members representing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the CMS, the National Institutes of Health, and others involved in research and policy making, addressed the panel to either explain or defend why their agency operates as it does.

In the case of the CMS, a statutory organization, it can apply coverage only according to what the agency is mandated to do, said Dr. Elizabeth Koller of the CMS. The level of evidence the agency looks for, she said, includes "hard endpoints of clinical relevance, like reductions in sleep apnea and degenerative joint disease." The CMS is also concerned about the lack of long-term data on interventions, the durability of interventions, and which characteristics are common in people who relapse in their disease, said Dr. Koller, who addressed the group as an audience member.

"Hearing from the CMS was incredibly helpful. We learned so much," said Dr. Mechanick, director of metabolic support at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York, in an interview.

Dr. Mechanick also said this was the first of three meetings, the next to be held in about a year, where the ultimate goal would be to use the evidence base they will have created to develop recommendations for all involved in delivering obesity care.

The talk was "polite," Dr. John Morton, chief of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University and president of the American Society of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery, said in an interview, but he said he thinks there is bias against people with obesity. "We wouldn’t be having this discussion if it were about cancer," he said in the interview. "Sometimes we think the consequences of obesity are the result of a personal decision, and that may skew people in a direction where they don’t necessarily want to provide help."

Regardless, Dr. Garvey said at the briefing, "the ‘old world’ thinking that obesity is a lifestyle choice has failed us."

Dr. Mechanick is a consultant for Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Garvey has multiple industry relationships, including with Merck, Vivus, and Eisai.

WASHINGTON – Obesity requires a medical definition that goes beyond gauging a person’s body mass index if cost-effective care is to be delivered in an integrated fashion, according to a consensus statement issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology.

"The definition of obesity as a disease is not perfect," Dr. W. Timothy Garvey, who chaired the AACE/ACE Obesity Consensus Conference, said in a media briefing. "We rely upon an [anthropometric] measure of body mass index, which is a measure of height versus weight, and there was consensus that this was ... divorced from the impact of weight gain on the health of the individual. This imprecision in our diagnosis of obesity was constraining us."

In 2013, the American Medical Association officially recognized obesity as a disease. Better codification of what actually constitutes "obesity, the disease," will allow a more integrated and effective approach to treating it, said Dr. Garvey, professor of medicine and chair of the department of nutrition sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. To do so, the AACE/ACE held an intensive, 2-day session that largely featured spontaneous discussions between panelists and audience members representing four specific obesity "pillars": biomedical, government and regulation, health industry and economics, and research and education sectors.

A constant theme across the sectors was the need for a definition of obesity that accounts for cultural differences, ethnicity, and the presence or absence of cardiometabolic markers of disease in persons who are overweight or obese.

The conference’s multidisciplined approach informed the consensus statement that obesity is a chronic disease that should be treated with the established AACE/ACE obesity algorithm and met with lifestyle interventions. The consensus statement also addressed our current "obesogenic" environment, which many participants said was created in part by the abundance of nonnutritious foods.

In an interview, Dr. Susan Kansagra, deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said that by working with local vendors and their suppliers, among other actions, her agency is focused on increasing access to more nutritious foods in neighborhoods across the city as a way to shape the food environment. "It’s not people who’ve changed over the past 30 years; it’s the environment," Dr. Kansagra said at the conference.

Also addressed by the consensus statement was the need for preventive care, particularly at the pediatric level, and more cohesive public awareness campaigns that could affect how private payers develop their reimbursement strategies. Audience member Dr. Robert Silverman, medical director of CIGNA Healthcare, said that payers would respond to the need for obesity care, but that what currently is missing is "a tie between the evidence and the complications [of obesity]."

"We learned that different stakeholders require different levels of evidence," AACE President Jeffrey I. Mechanick said in the media briefing. "So, we’re going to be able come up with a more efficient way to make recommendations about research so that private insurance carriers, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or regulatory agencies have the type of data they require to facilitate the action [they need]."

These differences were brought to light during the conference as various audience members representing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the CMS, the National Institutes of Health, and others involved in research and policy making, addressed the panel to either explain or defend why their agency operates as it does.

In the case of the CMS, a statutory organization, it can apply coverage only according to what the agency is mandated to do, said Dr. Elizabeth Koller of the CMS. The level of evidence the agency looks for, she said, includes "hard endpoints of clinical relevance, like reductions in sleep apnea and degenerative joint disease." The CMS is also concerned about the lack of long-term data on interventions, the durability of interventions, and which characteristics are common in people who relapse in their disease, said Dr. Koller, who addressed the group as an audience member.

"Hearing from the CMS was incredibly helpful. We learned so much," said Dr. Mechanick, director of metabolic support at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York, in an interview.

Dr. Mechanick also said this was the first of three meetings, the next to be held in about a year, where the ultimate goal would be to use the evidence base they will have created to develop recommendations for all involved in delivering obesity care.

The talk was "polite," Dr. John Morton, chief of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University and president of the American Society of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery, said in an interview, but he said he thinks there is bias against people with obesity. "We wouldn’t be having this discussion if it were about cancer," he said in the interview. "Sometimes we think the consequences of obesity are the result of a personal decision, and that may skew people in a direction where they don’t necessarily want to provide help."

Regardless, Dr. Garvey said at the briefing, "the ‘old world’ thinking that obesity is a lifestyle choice has failed us."