User login

Clinical Guidelines Hub only

VIP Boot Camp: Expanding the Impact of VA Primary Care Mental Health With a Transdiagnostic Modular Group Program

VIP Boot Camp: Expanding the Impact of VA Primary Care Mental Health With a Transdiagnostic Modular Group Program

Since 2007, Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has improved access to mental health care services for veterans by directly embedding mental health care professionals (HCPs) within primary care teams.1 Veterans referred to PCMHI often have co-occurring physical and mental health disorders.2 Untreated chronic physical and mental comorbidities can diminish the effectiveness of medical and mental health interventions. Growing evidence suggests that treatment of mental health conditions can improve physical health outcomes and management of physical conditions can improve mental health outcomes.2,3

Chronic pain and sleep disorders are common reasons patients present to primary care, and often coexist together with mental health comorbidities.4 Sleep disorders affect 50% to 88% of patients with chronic pain, and 40% of patients with sleep disorders report chronic pain.4 Research has found that chronic pain and sleep disorders increase the risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. Addressing suicide prevention simultaneously with treating chronic pain and insomnia is encouraged.5

Background

PCMHI treats physical and mental health comorbidities with a collaborative framework and a biopsychosocial integrative model.6 PCMHI staff provide mental health services as members of primary care teams. An interdisciplinary PCMHI team can include, but is not limited to, psychologists, mental health social workers, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, clinical pharmacists, and mental health nurses. Quality of care within this model is elevated, as mental and physical health are recognized as interconnected. Collaboration between primary care and mental health benefits veterans and the VHA by increasing access to mental health care, decreasing stigma associated with mental health treatment, improving health outcomes, and enhancing the likelihood of recovery, resulting in high patient satisfaction.6-8

In the existing PCMHI model, HCPs are encouraged to use short-term, evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs).9 Veterans referred to PCMHI from primary care are typically able to attend 1 to 6 brief sessions of mental health treatment, often 20 to 30 minutes long. Most EBPs in PCMHI are disorder- specific, providing interventions focused on a single presenting problem (eg, insomnia, chronic pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]). For veterans with a single issue, this model can be very effective. 1,10 However, the high rate of co-occurrence of mental and physical health issues can make it difficult to fully treat interrelated problems if the focus is on 1 specific diagnosis. Veterans with a need for additional (more comprehensive or intensive) mental health treatment are frequently referred to a higher, more resource-intensive level of mental health care, either in the VHA or the community. Examples of higher levels of mental health care include the longer term behavioral health interdisciplinary program (BHIP), sometimes called a mental health clinic (MHC), or a specialty mental health program such as a PTSD clinic.

As PCMHI continues to grow, new challenges have emerged related to staffing shortages and gaps in the clinical delivery of mental health treatment within the VHA. At the same time, demand for VHA mental health treatment has increased. However, a mental health professional shortage severely limits the ability of the VHA to meet this demand. In many systems, this shortage may result in more referrals being made to a higher level of mental health care because of fewer resources to provide comprehensive treatment in a less intensive PCMHI setting.8,10,11 This referral pattern can overburden higher level care, often with long wait times for treatment and lengthy lag times between appointments. Furthermore, these gaps in the clinical delivery of care cannot be effectively addressed by hiring additional mental health professionals. This strain on resources can impede access to care and negatively affect outcomes.10

Recent congressional reports highlight these issues, noting that demand for mental health services continues to outpace the capacity of both PCMHI and higher levels of mental health care, leading to delays in treatment that may negatively affect outcomes.8,10,11 These delays can be particularly detrimental for individuals with conditions requiring timely intervention.8,11 Some veterans are willing to engage with PCMHI in a primary care setting but may be reluctant to engage in general mental health treatment. These veterans might not receive the mental health care they need without PCMHI.

Group Psychotherapy

A group psychotherapy format can address gaps in care delivery and provide advantages for patients, mental health professionals, and the VHA. Group psychotherapy aligns with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) 2018 Blueprint for Excellence and 2018 to 2024 strategic plan, underscoring the need for more timely and efficient mental health services.12,13

Benefits of group psychotherapy include reductions in symptoms, decreased feelings of isolation, increased social support, decreased emotional suppression, and enhanced satisfaction with overall quality of life.14-17 Studies of veterans with PTSD have found less attrition among those who chose group therapy compared with individual therapy.14,18 Group psychotherapy improves access to care by enabling delivery to more patients.14 When compared with individual therapy, the group format allows for a large number of patients to be treated simultaneously, maximizing resources and reducing costs.3,19-21

VISN 9 CRH Innovation

The VA provides care to veterans through regionally distinct administrative systems known as Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Clinical resource hubs (CRH) are VISN-based programs created to cover VA staffing shortages by virtually deploying HCPs into local VA systems until vacancies are filled. The national CRH vision of effectively using resources and innovative technologies to meet veterans’ health care needs, along with the above-referenced clinical gaps in the delivery of care, inspired the development of VIP Boot Camp within the VISN 9 CRH.22

Program Description

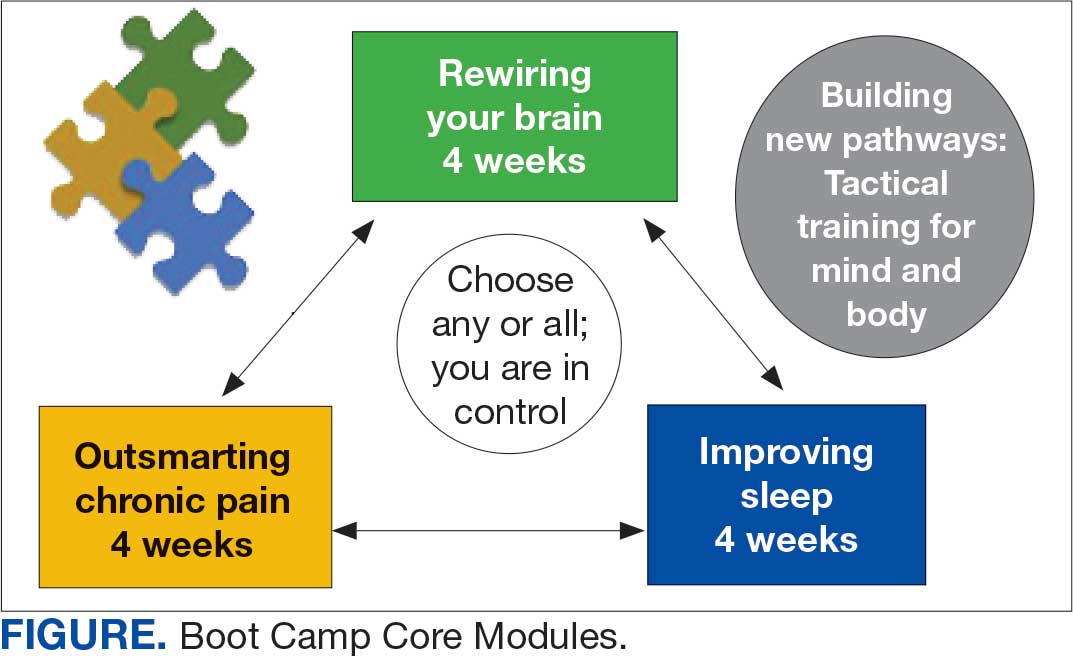

VIP Boot Camp is an evidence-informed group psychotherapy program designed to provide timely, brief, and comprehensive mental health treatment for veterans. VIP Boot Camp was developed to address the needs of veterans accessing PCMHI services who experience ≥ 1 of the often overlapping problems of anxiety/emotion regulation/stress, sleep difficulties, and chronic pain (Figure). VIP Boot Camp uses an integrative approach to highlight interconnections and similarities among these difficulties and their treatment. A primary vision of the program is to provide this comprehensive treatment within PCMHI (upstream) so additional referrals to higher levels of mental health care (downstream) may not be needed.

This design is intentional because it increases the number of individuals who can be treated upstream with comprehensive, preventive, and proactive care within PCMHI which, over time, frees up resources in the BHIP for individuals requiring higher levels of care. This approach also aligns with the importance of early treatment for chronic pain and sleep disturbances, which are linked to increased risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide for veterans.5 National interest for VIP Boot Camp grew during fiscal year 2024 after it received the Gold Medal Recognition for Most Adoptable and Greatest Potential for Impact during VHA National Access Sprint Wave 3—Mental Health Call of Champions.

History

VIP Boot Camp began in August 2021 at VISN 9 as a 6-week virtual group for veterans with chronic pain. It was established to assist a large VA medical center experiencing PCMHI staffing shortages and lacking available PCMHI groups. Many veterans in the chronic pain group discussed co-occurring issues such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, and stress. The CRH team considered launching 2 separate groups to address these additional PCMHI-level issues; however, in developing the group material which drew from multiple clinical approaches, the team recognized significant overlapping and interconnected themes.

The team discussed EBPs within the VHA and how certain interventions within these treatments could be helpful across many other co-occurring disorders. Integrated tactics (clinical interventions) were drawn from cognitive-behavioral therapy (for depression, insomnia, or chronic pain), acceptance and commitment therapy, prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, unified protocol, pain reprocessing therapy, emotional awareness and expression therapy, interpersonal neurobiology, and mindfulness. We collaborated with veterans during VIP Boot Camp groups to determine how to present and discuss complex interventions in ways that were clinically accurate, understandable, relatable, and relevant to their experiences.

To address accessibility issues, the chronic pain group was reduced to 4 weeks. A second 4-week module for anxiety, emotion regulation, and stress was developed, mirroring the tactics, language, and integrative approach of the revised chronic pain module. A similar integrative approach led to the development of the third and final 4-week module for sleep disturbances.

Current Program

The VIP Boot Camp consists of three 4-week integrated modules, each highlighting a critical area: sleep disturbances (Improving Sleep), chronic pain difficulties (Outsmarting Chronic Pain), and emotion regulation difficulties (Rewiring Your Brain). VIP Boot Camp is designed for veterans who are at the PCMHI level of care. Referrals are accepted for patients receiving treatment from primary care or PCMHI.

Guidelines for participation in VIP Boot Camp may differ across sites or VISNs. For example, a veteran who has been referred to the BHIP for medication management only or to a specialty MHC such as a pain clinic or PTSD clinic might also be appropriate and eligible for VIP Boot Camp.

Given the interconnectedness of foundational themes, elements, and practices across the VIP Boot Camp modules, the modules are offered in a rolling format with a veteran-centric “choose your own adventure” approach. Tactics are presented in the modules in a way that allows patients to begin with any 1 of the 3 modules and receive treatment that will help in the other areas. Participants choose their core module and initial treatment focus based on their values, needs, and goals. Individuals who complete a core module can end their VIP Boot Camp experience or continue to the next 4-week module for up to 3 modules.

The group is open to new individuals at the start of any 4-week module and closed for the remainder of its 4-week duration. This innovative rolling modular approach combines elements of open- and closed-group format, allowing for the flexibility and accessibility of an open group with the stability and peer support of a closed group.

Given the complicated and overlapping nature of chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances, VIP Boot Camp acknowledges that everything is interconnected and difficulties in 1 area may impact other areas. The 3 interconnected modules with repeating themes provide coherence and consistency. Veterans learn how interconnections across difficulties can be leveraged so that tactics learned and practiced in 1 area can assist in other areas, changing the cycle of suffering into a cycle of growth.

VIP Boot Camp sessions are 90 minutes long, once weekly for 4 weeks, with 2 mental health professionals trained to lead a dynamic group psychotherapy experience that aims to be fun for participants. VIP Boot Camp synthesizes evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions, as well as techniques from VHA complementary and integrative health programs, psychoeducation, and interpersonal interventions that model connection, playfulness, and healthy boundaries. These varied strategies combine to equip veterans with practical tactics for self-management outside of sessions, a process described as “finding puzzle pieces.” VIP Boot Camp is built on the idea that people are more likely to adopt and practice any tactic after being taught why that tactic is important, and how it fits into their larger interconnected puzzle. After each session, participants are provided with additional asynchronous educational material to help reinforce their learnings and practices.

Although individuals may hesitate to participate in a group setting, they often find the experience of community enhances and accelerates their treatment and gains. This involvement is highlighted in a core aspect of a VIP Boot Camp session called wins, during which participants learn how others on their Boot Camp team are implementing new skills and moving toward their personal values and objectives in a stepwise manner. Through these shared experiences, veterans discover how tactics working for others may serve as a model for their own personal objectives and plans for practice. The sense of relief described by many upon realizing they are not alone in their experiences, along with the satisfaction felt in discovering their ability to support others in Boot Camp, is described by many participants as deeply meaningful and in line with their personal values.

While developed as a fully virtual group program, VIP Boot Camp can also be conducted in person. The virtual program has been successful and continues to spread across VISN 9. There are 8 virtual VIP Boot Camps running in VISN 9, with plans for continued expansion. In the VISN 9 CRH, Boot Camps typically have 10 to 12 participants. Additionally, as VIP Boot Camp grows within a location there are frequently sufficient referrals to support a second rolling group, which enables staggering of the module offerings to allow for even more timely treatment.

Training Program

VISN 9 CRH also developed a VIP Boot Camp 3-day intensive training program for PCMHI HCPs that consists of learning and practicing VIP Boot Camp material for chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, sleep disturbances, mindfulness, and guided imagery, along with gaining experience as a VIP Boot Camp coleader. Feedback received from PCMHI HCPs who completed training has been positive. There is also a private Microsoft Teams channel for HCPs, which allows for resource sharing and community building among coleaders. More than 75 PCMHI HCPs have completed VIP Boot Camp training and > 25 VIP Boot Camps have been established at 4 additional VISNs.

The VISN 9 CRH VIP Boot Camp program initiated an implementation and effectiveness project with the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. The focus of this collaboration is support for implementation and treatment effectiveness research with reports, articles, and a white paper on findings and best practices, alongside continued dissemination of the VIP Boot Camp program and training.

Conclusions

VIP Boot Camp is a PCMHI group program offering readily available, comprehensive, and integrative group psychotherapy services to veterans experiencing . 1 of the following: chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances. It was launched at the VISN 9 CRH with a goal of addressing clinical gaps in the delivery of mental health care, by increasing the number of patients treated within PCMHI. The VIP Boot Camp model provides veterans the opportunity to transform cycles of suffering into cycles of growth through a single approach that can address multiple presenting and interconnected issues.

A 3-day VIP Boot Camp training program provides a quick and effective path for a PCMHI program to train HCPs to launch a VIP Boot Camp. The VISN 9 CRH will continue to champion VIP Boot Camp as a model for the successful provision of comprehensive and integrative mental health treatment within PCMHI at the VA. Through readily available access to comprehensive mental health treatment in an environment that promotes participant empowerment and social engagement, VIP Boot Camp represents an integrative and innovative model of mental health treatment that offers benefits to veteran participants, HCPs, and the VHA.

- Leung LB, Yoon J, Escarce JJ, et al. Primary care-mental health integration in the VA: shifting mental health services for common mental illnesses to primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:403-409. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700190

- Zhang A, Park S, Sullivan JE, et al. The effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for primary care patients’ depressive and/or anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:139-150. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170270

- Hundt NE, Barrera TL, Robinson A, et al. A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179:942-949. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-14-00128

- Jank R, Gallee A, Boeckle M, et al. Chronic pain and sleep disorders in primary care. Pain Res Treat. 2017;2017:1-9. doi:10.1155/2017/9081802

- Ashrafioun L, Bishop TM, Pigeon WR. The relationship between pain severity, insomnia, and suicide attempts among a national veteran sample initiating pain care. Psychosom Med. 2021;83:733- 738. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000975

- Ramanuj P, Ferenchik E, Docherty M, et al. Evolving models of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:1. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-0985-4

- Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83-90. doi:10.1037/a0020130

- Smith TL, Kim B, Benzer JK, et al. FLOW: early results from a clinical demonstration project to improve the transition of patients with mental health disorders back to primary care. Psychol Serv. 2021;18:23-32. doi:10.1037/ser0000336

- Kearney LK, Post EP, Pomerantz AS, et al. Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the department of veterans affairs transforming primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):399-408. doi:10.1037/a0035909

- US Government Accountability Office. Veterans health care: staffing challenges persist for fully integrating mental health and primary care services. December 15, 2022. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105372

- National Academies of Science and Engineering. Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24915/evaluation-of-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-mental-health-services

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Blueprint for excellence: achieving veterans’ excellence. October 6, 2014. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.volunteer.va.gov/docs/blueprintforexcellence_factsheet.PDF

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018-2024 strategic plan. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.calvet.ca.gov/Regulations/USDVA%20Strategic%20Plan%202018-2024.pdf

- Sripada RK, Bohnert KM, Ganoczy D, et al. Initial group versus individual therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and subsequent follow-up treatment adequacy. Psychol Serv. 2016;13:349-355. doi:10.1037/ser0000077

- Burnett-Zeigler IE, Pfeiffer P, Zivin K, et al. Psychotherapy utilization for acute depression within the Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:325-335. doi:10.1037/a0027957

- Kim JS, Prins A, Hirschhorn EW, et al. Preliminary investigation into the effectiveness of group webSTAIR for trauma-exposed veterans in primary care. Mil Med. 2024;189:e1403-e1408. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae052

- Jakupcak M, Blais RK, Grossbard J, et al. “Toughness” in association with mental health symptoms among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking Veterans Affairs health care. Psychol Men Masc. 2014;15:100-104. doi:10.1037/a0031508

- Stoycos SA, Berzenski SR, Beck JG, et al. Predictors of treatment completion in group psychotherapy for male veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36:346-358. doi:10.1002/jts.22915

- Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9237-4

- Hunt MG, Rosenheck RA. Psychotherapy in mental health clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:561-573. doi:10.1002/jclp.20788

- Khatri N, Marziali E, Tchernikov I, et al. Comparing telehealth-based and clinic-based group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depression and anxiety: a pilot study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:765. doi:10.2147/cia.s57832

- Dangel J. Clinical resource hub increases veterans' access to care. VA News. January 12, 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://news.va.gov/137439/clinical-resource-hub-increases-access-to-care/

Since 2007, Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has improved access to mental health care services for veterans by directly embedding mental health care professionals (HCPs) within primary care teams.1 Veterans referred to PCMHI often have co-occurring physical and mental health disorders.2 Untreated chronic physical and mental comorbidities can diminish the effectiveness of medical and mental health interventions. Growing evidence suggests that treatment of mental health conditions can improve physical health outcomes and management of physical conditions can improve mental health outcomes.2,3

Chronic pain and sleep disorders are common reasons patients present to primary care, and often coexist together with mental health comorbidities.4 Sleep disorders affect 50% to 88% of patients with chronic pain, and 40% of patients with sleep disorders report chronic pain.4 Research has found that chronic pain and sleep disorders increase the risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. Addressing suicide prevention simultaneously with treating chronic pain and insomnia is encouraged.5

Background

PCMHI treats physical and mental health comorbidities with a collaborative framework and a biopsychosocial integrative model.6 PCMHI staff provide mental health services as members of primary care teams. An interdisciplinary PCMHI team can include, but is not limited to, psychologists, mental health social workers, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, clinical pharmacists, and mental health nurses. Quality of care within this model is elevated, as mental and physical health are recognized as interconnected. Collaboration between primary care and mental health benefits veterans and the VHA by increasing access to mental health care, decreasing stigma associated with mental health treatment, improving health outcomes, and enhancing the likelihood of recovery, resulting in high patient satisfaction.6-8

In the existing PCMHI model, HCPs are encouraged to use short-term, evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs).9 Veterans referred to PCMHI from primary care are typically able to attend 1 to 6 brief sessions of mental health treatment, often 20 to 30 minutes long. Most EBPs in PCMHI are disorder- specific, providing interventions focused on a single presenting problem (eg, insomnia, chronic pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]). For veterans with a single issue, this model can be very effective. 1,10 However, the high rate of co-occurrence of mental and physical health issues can make it difficult to fully treat interrelated problems if the focus is on 1 specific diagnosis. Veterans with a need for additional (more comprehensive or intensive) mental health treatment are frequently referred to a higher, more resource-intensive level of mental health care, either in the VHA or the community. Examples of higher levels of mental health care include the longer term behavioral health interdisciplinary program (BHIP), sometimes called a mental health clinic (MHC), or a specialty mental health program such as a PTSD clinic.

As PCMHI continues to grow, new challenges have emerged related to staffing shortages and gaps in the clinical delivery of mental health treatment within the VHA. At the same time, demand for VHA mental health treatment has increased. However, a mental health professional shortage severely limits the ability of the VHA to meet this demand. In many systems, this shortage may result in more referrals being made to a higher level of mental health care because of fewer resources to provide comprehensive treatment in a less intensive PCMHI setting.8,10,11 This referral pattern can overburden higher level care, often with long wait times for treatment and lengthy lag times between appointments. Furthermore, these gaps in the clinical delivery of care cannot be effectively addressed by hiring additional mental health professionals. This strain on resources can impede access to care and negatively affect outcomes.10

Recent congressional reports highlight these issues, noting that demand for mental health services continues to outpace the capacity of both PCMHI and higher levels of mental health care, leading to delays in treatment that may negatively affect outcomes.8,10,11 These delays can be particularly detrimental for individuals with conditions requiring timely intervention.8,11 Some veterans are willing to engage with PCMHI in a primary care setting but may be reluctant to engage in general mental health treatment. These veterans might not receive the mental health care they need without PCMHI.

Group Psychotherapy

A group psychotherapy format can address gaps in care delivery and provide advantages for patients, mental health professionals, and the VHA. Group psychotherapy aligns with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) 2018 Blueprint for Excellence and 2018 to 2024 strategic plan, underscoring the need for more timely and efficient mental health services.12,13

Benefits of group psychotherapy include reductions in symptoms, decreased feelings of isolation, increased social support, decreased emotional suppression, and enhanced satisfaction with overall quality of life.14-17 Studies of veterans with PTSD have found less attrition among those who chose group therapy compared with individual therapy.14,18 Group psychotherapy improves access to care by enabling delivery to more patients.14 When compared with individual therapy, the group format allows for a large number of patients to be treated simultaneously, maximizing resources and reducing costs.3,19-21

VISN 9 CRH Innovation

The VA provides care to veterans through regionally distinct administrative systems known as Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Clinical resource hubs (CRH) are VISN-based programs created to cover VA staffing shortages by virtually deploying HCPs into local VA systems until vacancies are filled. The national CRH vision of effectively using resources and innovative technologies to meet veterans’ health care needs, along with the above-referenced clinical gaps in the delivery of care, inspired the development of VIP Boot Camp within the VISN 9 CRH.22

Program Description

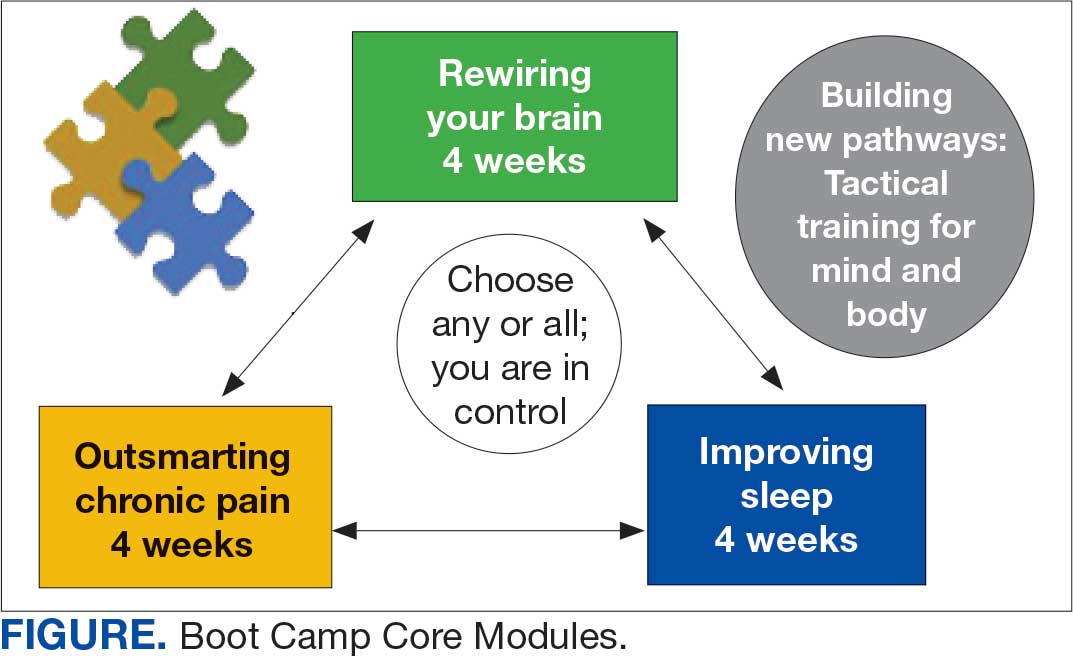

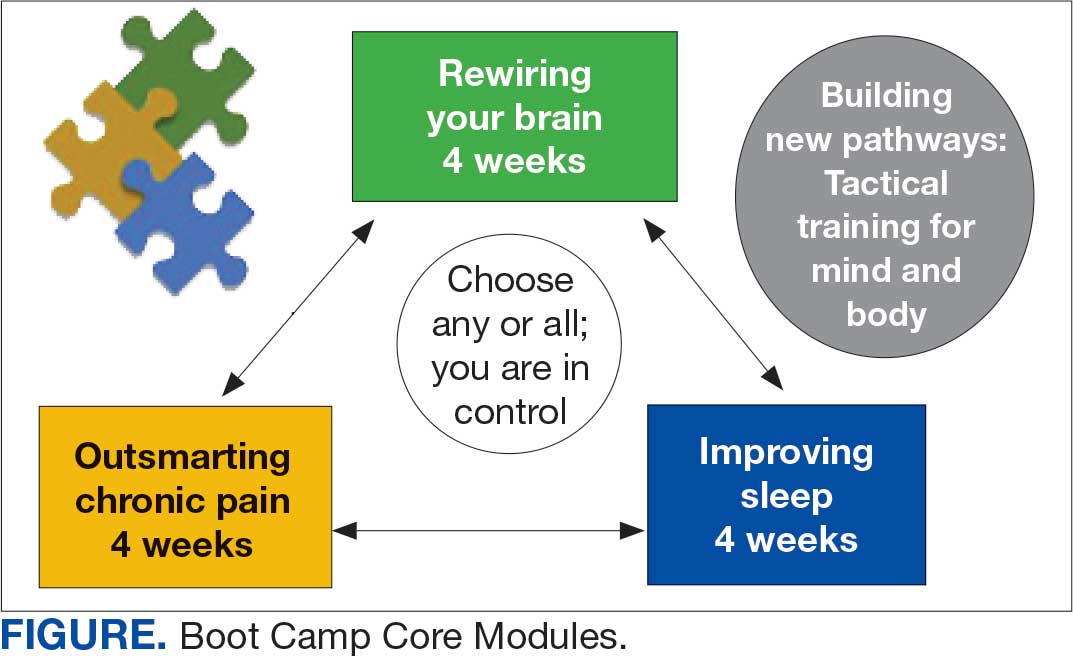

VIP Boot Camp is an evidence-informed group psychotherapy program designed to provide timely, brief, and comprehensive mental health treatment for veterans. VIP Boot Camp was developed to address the needs of veterans accessing PCMHI services who experience ≥ 1 of the often overlapping problems of anxiety/emotion regulation/stress, sleep difficulties, and chronic pain (Figure). VIP Boot Camp uses an integrative approach to highlight interconnections and similarities among these difficulties and their treatment. A primary vision of the program is to provide this comprehensive treatment within PCMHI (upstream) so additional referrals to higher levels of mental health care (downstream) may not be needed.

This design is intentional because it increases the number of individuals who can be treated upstream with comprehensive, preventive, and proactive care within PCMHI which, over time, frees up resources in the BHIP for individuals requiring higher levels of care. This approach also aligns with the importance of early treatment for chronic pain and sleep disturbances, which are linked to increased risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide for veterans.5 National interest for VIP Boot Camp grew during fiscal year 2024 after it received the Gold Medal Recognition for Most Adoptable and Greatest Potential for Impact during VHA National Access Sprint Wave 3—Mental Health Call of Champions.

History

VIP Boot Camp began in August 2021 at VISN 9 as a 6-week virtual group for veterans with chronic pain. It was established to assist a large VA medical center experiencing PCMHI staffing shortages and lacking available PCMHI groups. Many veterans in the chronic pain group discussed co-occurring issues such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, and stress. The CRH team considered launching 2 separate groups to address these additional PCMHI-level issues; however, in developing the group material which drew from multiple clinical approaches, the team recognized significant overlapping and interconnected themes.

The team discussed EBPs within the VHA and how certain interventions within these treatments could be helpful across many other co-occurring disorders. Integrated tactics (clinical interventions) were drawn from cognitive-behavioral therapy (for depression, insomnia, or chronic pain), acceptance and commitment therapy, prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, unified protocol, pain reprocessing therapy, emotional awareness and expression therapy, interpersonal neurobiology, and mindfulness. We collaborated with veterans during VIP Boot Camp groups to determine how to present and discuss complex interventions in ways that were clinically accurate, understandable, relatable, and relevant to their experiences.

To address accessibility issues, the chronic pain group was reduced to 4 weeks. A second 4-week module for anxiety, emotion regulation, and stress was developed, mirroring the tactics, language, and integrative approach of the revised chronic pain module. A similar integrative approach led to the development of the third and final 4-week module for sleep disturbances.

Current Program

The VIP Boot Camp consists of three 4-week integrated modules, each highlighting a critical area: sleep disturbances (Improving Sleep), chronic pain difficulties (Outsmarting Chronic Pain), and emotion regulation difficulties (Rewiring Your Brain). VIP Boot Camp is designed for veterans who are at the PCMHI level of care. Referrals are accepted for patients receiving treatment from primary care or PCMHI.

Guidelines for participation in VIP Boot Camp may differ across sites or VISNs. For example, a veteran who has been referred to the BHIP for medication management only or to a specialty MHC such as a pain clinic or PTSD clinic might also be appropriate and eligible for VIP Boot Camp.

Given the interconnectedness of foundational themes, elements, and practices across the VIP Boot Camp modules, the modules are offered in a rolling format with a veteran-centric “choose your own adventure” approach. Tactics are presented in the modules in a way that allows patients to begin with any 1 of the 3 modules and receive treatment that will help in the other areas. Participants choose their core module and initial treatment focus based on their values, needs, and goals. Individuals who complete a core module can end their VIP Boot Camp experience or continue to the next 4-week module for up to 3 modules.

The group is open to new individuals at the start of any 4-week module and closed for the remainder of its 4-week duration. This innovative rolling modular approach combines elements of open- and closed-group format, allowing for the flexibility and accessibility of an open group with the stability and peer support of a closed group.

Given the complicated and overlapping nature of chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances, VIP Boot Camp acknowledges that everything is interconnected and difficulties in 1 area may impact other areas. The 3 interconnected modules with repeating themes provide coherence and consistency. Veterans learn how interconnections across difficulties can be leveraged so that tactics learned and practiced in 1 area can assist in other areas, changing the cycle of suffering into a cycle of growth.

VIP Boot Camp sessions are 90 minutes long, once weekly for 4 weeks, with 2 mental health professionals trained to lead a dynamic group psychotherapy experience that aims to be fun for participants. VIP Boot Camp synthesizes evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions, as well as techniques from VHA complementary and integrative health programs, psychoeducation, and interpersonal interventions that model connection, playfulness, and healthy boundaries. These varied strategies combine to equip veterans with practical tactics for self-management outside of sessions, a process described as “finding puzzle pieces.” VIP Boot Camp is built on the idea that people are more likely to adopt and practice any tactic after being taught why that tactic is important, and how it fits into their larger interconnected puzzle. After each session, participants are provided with additional asynchronous educational material to help reinforce their learnings and practices.

Although individuals may hesitate to participate in a group setting, they often find the experience of community enhances and accelerates their treatment and gains. This involvement is highlighted in a core aspect of a VIP Boot Camp session called wins, during which participants learn how others on their Boot Camp team are implementing new skills and moving toward their personal values and objectives in a stepwise manner. Through these shared experiences, veterans discover how tactics working for others may serve as a model for their own personal objectives and plans for practice. The sense of relief described by many upon realizing they are not alone in their experiences, along with the satisfaction felt in discovering their ability to support others in Boot Camp, is described by many participants as deeply meaningful and in line with their personal values.

While developed as a fully virtual group program, VIP Boot Camp can also be conducted in person. The virtual program has been successful and continues to spread across VISN 9. There are 8 virtual VIP Boot Camps running in VISN 9, with plans for continued expansion. In the VISN 9 CRH, Boot Camps typically have 10 to 12 participants. Additionally, as VIP Boot Camp grows within a location there are frequently sufficient referrals to support a second rolling group, which enables staggering of the module offerings to allow for even more timely treatment.

Training Program

VISN 9 CRH also developed a VIP Boot Camp 3-day intensive training program for PCMHI HCPs that consists of learning and practicing VIP Boot Camp material for chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, sleep disturbances, mindfulness, and guided imagery, along with gaining experience as a VIP Boot Camp coleader. Feedback received from PCMHI HCPs who completed training has been positive. There is also a private Microsoft Teams channel for HCPs, which allows for resource sharing and community building among coleaders. More than 75 PCMHI HCPs have completed VIP Boot Camp training and > 25 VIP Boot Camps have been established at 4 additional VISNs.

The VISN 9 CRH VIP Boot Camp program initiated an implementation and effectiveness project with the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. The focus of this collaboration is support for implementation and treatment effectiveness research with reports, articles, and a white paper on findings and best practices, alongside continued dissemination of the VIP Boot Camp program and training.

Conclusions

VIP Boot Camp is a PCMHI group program offering readily available, comprehensive, and integrative group psychotherapy services to veterans experiencing . 1 of the following: chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances. It was launched at the VISN 9 CRH with a goal of addressing clinical gaps in the delivery of mental health care, by increasing the number of patients treated within PCMHI. The VIP Boot Camp model provides veterans the opportunity to transform cycles of suffering into cycles of growth through a single approach that can address multiple presenting and interconnected issues.

A 3-day VIP Boot Camp training program provides a quick and effective path for a PCMHI program to train HCPs to launch a VIP Boot Camp. The VISN 9 CRH will continue to champion VIP Boot Camp as a model for the successful provision of comprehensive and integrative mental health treatment within PCMHI at the VA. Through readily available access to comprehensive mental health treatment in an environment that promotes participant empowerment and social engagement, VIP Boot Camp represents an integrative and innovative model of mental health treatment that offers benefits to veteran participants, HCPs, and the VHA.

Since 2007, Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has improved access to mental health care services for veterans by directly embedding mental health care professionals (HCPs) within primary care teams.1 Veterans referred to PCMHI often have co-occurring physical and mental health disorders.2 Untreated chronic physical and mental comorbidities can diminish the effectiveness of medical and mental health interventions. Growing evidence suggests that treatment of mental health conditions can improve physical health outcomes and management of physical conditions can improve mental health outcomes.2,3

Chronic pain and sleep disorders are common reasons patients present to primary care, and often coexist together with mental health comorbidities.4 Sleep disorders affect 50% to 88% of patients with chronic pain, and 40% of patients with sleep disorders report chronic pain.4 Research has found that chronic pain and sleep disorders increase the risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. Addressing suicide prevention simultaneously with treating chronic pain and insomnia is encouraged.5

Background

PCMHI treats physical and mental health comorbidities with a collaborative framework and a biopsychosocial integrative model.6 PCMHI staff provide mental health services as members of primary care teams. An interdisciplinary PCMHI team can include, but is not limited to, psychologists, mental health social workers, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, clinical pharmacists, and mental health nurses. Quality of care within this model is elevated, as mental and physical health are recognized as interconnected. Collaboration between primary care and mental health benefits veterans and the VHA by increasing access to mental health care, decreasing stigma associated with mental health treatment, improving health outcomes, and enhancing the likelihood of recovery, resulting in high patient satisfaction.6-8

In the existing PCMHI model, HCPs are encouraged to use short-term, evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs).9 Veterans referred to PCMHI from primary care are typically able to attend 1 to 6 brief sessions of mental health treatment, often 20 to 30 minutes long. Most EBPs in PCMHI are disorder- specific, providing interventions focused on a single presenting problem (eg, insomnia, chronic pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]). For veterans with a single issue, this model can be very effective. 1,10 However, the high rate of co-occurrence of mental and physical health issues can make it difficult to fully treat interrelated problems if the focus is on 1 specific diagnosis. Veterans with a need for additional (more comprehensive or intensive) mental health treatment are frequently referred to a higher, more resource-intensive level of mental health care, either in the VHA or the community. Examples of higher levels of mental health care include the longer term behavioral health interdisciplinary program (BHIP), sometimes called a mental health clinic (MHC), or a specialty mental health program such as a PTSD clinic.

As PCMHI continues to grow, new challenges have emerged related to staffing shortages and gaps in the clinical delivery of mental health treatment within the VHA. At the same time, demand for VHA mental health treatment has increased. However, a mental health professional shortage severely limits the ability of the VHA to meet this demand. In many systems, this shortage may result in more referrals being made to a higher level of mental health care because of fewer resources to provide comprehensive treatment in a less intensive PCMHI setting.8,10,11 This referral pattern can overburden higher level care, often with long wait times for treatment and lengthy lag times between appointments. Furthermore, these gaps in the clinical delivery of care cannot be effectively addressed by hiring additional mental health professionals. This strain on resources can impede access to care and negatively affect outcomes.10

Recent congressional reports highlight these issues, noting that demand for mental health services continues to outpace the capacity of both PCMHI and higher levels of mental health care, leading to delays in treatment that may negatively affect outcomes.8,10,11 These delays can be particularly detrimental for individuals with conditions requiring timely intervention.8,11 Some veterans are willing to engage with PCMHI in a primary care setting but may be reluctant to engage in general mental health treatment. These veterans might not receive the mental health care they need without PCMHI.

Group Psychotherapy

A group psychotherapy format can address gaps in care delivery and provide advantages for patients, mental health professionals, and the VHA. Group psychotherapy aligns with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) 2018 Blueprint for Excellence and 2018 to 2024 strategic plan, underscoring the need for more timely and efficient mental health services.12,13

Benefits of group psychotherapy include reductions in symptoms, decreased feelings of isolation, increased social support, decreased emotional suppression, and enhanced satisfaction with overall quality of life.14-17 Studies of veterans with PTSD have found less attrition among those who chose group therapy compared with individual therapy.14,18 Group psychotherapy improves access to care by enabling delivery to more patients.14 When compared with individual therapy, the group format allows for a large number of patients to be treated simultaneously, maximizing resources and reducing costs.3,19-21

VISN 9 CRH Innovation

The VA provides care to veterans through regionally distinct administrative systems known as Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Clinical resource hubs (CRH) are VISN-based programs created to cover VA staffing shortages by virtually deploying HCPs into local VA systems until vacancies are filled. The national CRH vision of effectively using resources and innovative technologies to meet veterans’ health care needs, along with the above-referenced clinical gaps in the delivery of care, inspired the development of VIP Boot Camp within the VISN 9 CRH.22

Program Description

VIP Boot Camp is an evidence-informed group psychotherapy program designed to provide timely, brief, and comprehensive mental health treatment for veterans. VIP Boot Camp was developed to address the needs of veterans accessing PCMHI services who experience ≥ 1 of the often overlapping problems of anxiety/emotion regulation/stress, sleep difficulties, and chronic pain (Figure). VIP Boot Camp uses an integrative approach to highlight interconnections and similarities among these difficulties and their treatment. A primary vision of the program is to provide this comprehensive treatment within PCMHI (upstream) so additional referrals to higher levels of mental health care (downstream) may not be needed.

This design is intentional because it increases the number of individuals who can be treated upstream with comprehensive, preventive, and proactive care within PCMHI which, over time, frees up resources in the BHIP for individuals requiring higher levels of care. This approach also aligns with the importance of early treatment for chronic pain and sleep disturbances, which are linked to increased risk of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide for veterans.5 National interest for VIP Boot Camp grew during fiscal year 2024 after it received the Gold Medal Recognition for Most Adoptable and Greatest Potential for Impact during VHA National Access Sprint Wave 3—Mental Health Call of Champions.

History

VIP Boot Camp began in August 2021 at VISN 9 as a 6-week virtual group for veterans with chronic pain. It was established to assist a large VA medical center experiencing PCMHI staffing shortages and lacking available PCMHI groups. Many veterans in the chronic pain group discussed co-occurring issues such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, and stress. The CRH team considered launching 2 separate groups to address these additional PCMHI-level issues; however, in developing the group material which drew from multiple clinical approaches, the team recognized significant overlapping and interconnected themes.

The team discussed EBPs within the VHA and how certain interventions within these treatments could be helpful across many other co-occurring disorders. Integrated tactics (clinical interventions) were drawn from cognitive-behavioral therapy (for depression, insomnia, or chronic pain), acceptance and commitment therapy, prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, unified protocol, pain reprocessing therapy, emotional awareness and expression therapy, interpersonal neurobiology, and mindfulness. We collaborated with veterans during VIP Boot Camp groups to determine how to present and discuss complex interventions in ways that were clinically accurate, understandable, relatable, and relevant to their experiences.

To address accessibility issues, the chronic pain group was reduced to 4 weeks. A second 4-week module for anxiety, emotion regulation, and stress was developed, mirroring the tactics, language, and integrative approach of the revised chronic pain module. A similar integrative approach led to the development of the third and final 4-week module for sleep disturbances.

Current Program

The VIP Boot Camp consists of three 4-week integrated modules, each highlighting a critical area: sleep disturbances (Improving Sleep), chronic pain difficulties (Outsmarting Chronic Pain), and emotion regulation difficulties (Rewiring Your Brain). VIP Boot Camp is designed for veterans who are at the PCMHI level of care. Referrals are accepted for patients receiving treatment from primary care or PCMHI.

Guidelines for participation in VIP Boot Camp may differ across sites or VISNs. For example, a veteran who has been referred to the BHIP for medication management only or to a specialty MHC such as a pain clinic or PTSD clinic might also be appropriate and eligible for VIP Boot Camp.

Given the interconnectedness of foundational themes, elements, and practices across the VIP Boot Camp modules, the modules are offered in a rolling format with a veteran-centric “choose your own adventure” approach. Tactics are presented in the modules in a way that allows patients to begin with any 1 of the 3 modules and receive treatment that will help in the other areas. Participants choose their core module and initial treatment focus based on their values, needs, and goals. Individuals who complete a core module can end their VIP Boot Camp experience or continue to the next 4-week module for up to 3 modules.

The group is open to new individuals at the start of any 4-week module and closed for the remainder of its 4-week duration. This innovative rolling modular approach combines elements of open- and closed-group format, allowing for the flexibility and accessibility of an open group with the stability and peer support of a closed group.

Given the complicated and overlapping nature of chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances, VIP Boot Camp acknowledges that everything is interconnected and difficulties in 1 area may impact other areas. The 3 interconnected modules with repeating themes provide coherence and consistency. Veterans learn how interconnections across difficulties can be leveraged so that tactics learned and practiced in 1 area can assist in other areas, changing the cycle of suffering into a cycle of growth.

VIP Boot Camp sessions are 90 minutes long, once weekly for 4 weeks, with 2 mental health professionals trained to lead a dynamic group psychotherapy experience that aims to be fun for participants. VIP Boot Camp synthesizes evidence-based and evidence-informed interventions, as well as techniques from VHA complementary and integrative health programs, psychoeducation, and interpersonal interventions that model connection, playfulness, and healthy boundaries. These varied strategies combine to equip veterans with practical tactics for self-management outside of sessions, a process described as “finding puzzle pieces.” VIP Boot Camp is built on the idea that people are more likely to adopt and practice any tactic after being taught why that tactic is important, and how it fits into their larger interconnected puzzle. After each session, participants are provided with additional asynchronous educational material to help reinforce their learnings and practices.

Although individuals may hesitate to participate in a group setting, they often find the experience of community enhances and accelerates their treatment and gains. This involvement is highlighted in a core aspect of a VIP Boot Camp session called wins, during which participants learn how others on their Boot Camp team are implementing new skills and moving toward their personal values and objectives in a stepwise manner. Through these shared experiences, veterans discover how tactics working for others may serve as a model for their own personal objectives and plans for practice. The sense of relief described by many upon realizing they are not alone in their experiences, along with the satisfaction felt in discovering their ability to support others in Boot Camp, is described by many participants as deeply meaningful and in line with their personal values.

While developed as a fully virtual group program, VIP Boot Camp can also be conducted in person. The virtual program has been successful and continues to spread across VISN 9. There are 8 virtual VIP Boot Camps running in VISN 9, with plans for continued expansion. In the VISN 9 CRH, Boot Camps typically have 10 to 12 participants. Additionally, as VIP Boot Camp grows within a location there are frequently sufficient referrals to support a second rolling group, which enables staggering of the module offerings to allow for even more timely treatment.

Training Program

VISN 9 CRH also developed a VIP Boot Camp 3-day intensive training program for PCMHI HCPs that consists of learning and practicing VIP Boot Camp material for chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, sleep disturbances, mindfulness, and guided imagery, along with gaining experience as a VIP Boot Camp coleader. Feedback received from PCMHI HCPs who completed training has been positive. There is also a private Microsoft Teams channel for HCPs, which allows for resource sharing and community building among coleaders. More than 75 PCMHI HCPs have completed VIP Boot Camp training and > 25 VIP Boot Camps have been established at 4 additional VISNs.

The VISN 9 CRH VIP Boot Camp program initiated an implementation and effectiveness project with the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. The focus of this collaboration is support for implementation and treatment effectiveness research with reports, articles, and a white paper on findings and best practices, alongside continued dissemination of the VIP Boot Camp program and training.

Conclusions

VIP Boot Camp is a PCMHI group program offering readily available, comprehensive, and integrative group psychotherapy services to veterans experiencing . 1 of the following: chronic pain, emotion regulation/ stress, and sleep disturbances. It was launched at the VISN 9 CRH with a goal of addressing clinical gaps in the delivery of mental health care, by increasing the number of patients treated within PCMHI. The VIP Boot Camp model provides veterans the opportunity to transform cycles of suffering into cycles of growth through a single approach that can address multiple presenting and interconnected issues.

A 3-day VIP Boot Camp training program provides a quick and effective path for a PCMHI program to train HCPs to launch a VIP Boot Camp. The VISN 9 CRH will continue to champion VIP Boot Camp as a model for the successful provision of comprehensive and integrative mental health treatment within PCMHI at the VA. Through readily available access to comprehensive mental health treatment in an environment that promotes participant empowerment and social engagement, VIP Boot Camp represents an integrative and innovative model of mental health treatment that offers benefits to veteran participants, HCPs, and the VHA.

- Leung LB, Yoon J, Escarce JJ, et al. Primary care-mental health integration in the VA: shifting mental health services for common mental illnesses to primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:403-409. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700190

- Zhang A, Park S, Sullivan JE, et al. The effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for primary care patients’ depressive and/or anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:139-150. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170270

- Hundt NE, Barrera TL, Robinson A, et al. A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179:942-949. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-14-00128

- Jank R, Gallee A, Boeckle M, et al. Chronic pain and sleep disorders in primary care. Pain Res Treat. 2017;2017:1-9. doi:10.1155/2017/9081802

- Ashrafioun L, Bishop TM, Pigeon WR. The relationship between pain severity, insomnia, and suicide attempts among a national veteran sample initiating pain care. Psychosom Med. 2021;83:733- 738. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000975

- Ramanuj P, Ferenchik E, Docherty M, et al. Evolving models of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:1. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-0985-4

- Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83-90. doi:10.1037/a0020130

- Smith TL, Kim B, Benzer JK, et al. FLOW: early results from a clinical demonstration project to improve the transition of patients with mental health disorders back to primary care. Psychol Serv. 2021;18:23-32. doi:10.1037/ser0000336

- Kearney LK, Post EP, Pomerantz AS, et al. Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the department of veterans affairs transforming primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):399-408. doi:10.1037/a0035909

- US Government Accountability Office. Veterans health care: staffing challenges persist for fully integrating mental health and primary care services. December 15, 2022. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105372

- National Academies of Science and Engineering. Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24915/evaluation-of-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-mental-health-services

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Blueprint for excellence: achieving veterans’ excellence. October 6, 2014. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.volunteer.va.gov/docs/blueprintforexcellence_factsheet.PDF

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018-2024 strategic plan. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.calvet.ca.gov/Regulations/USDVA%20Strategic%20Plan%202018-2024.pdf

- Sripada RK, Bohnert KM, Ganoczy D, et al. Initial group versus individual therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and subsequent follow-up treatment adequacy. Psychol Serv. 2016;13:349-355. doi:10.1037/ser0000077

- Burnett-Zeigler IE, Pfeiffer P, Zivin K, et al. Psychotherapy utilization for acute depression within the Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:325-335. doi:10.1037/a0027957

- Kim JS, Prins A, Hirschhorn EW, et al. Preliminary investigation into the effectiveness of group webSTAIR for trauma-exposed veterans in primary care. Mil Med. 2024;189:e1403-e1408. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae052

- Jakupcak M, Blais RK, Grossbard J, et al. “Toughness” in association with mental health symptoms among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking Veterans Affairs health care. Psychol Men Masc. 2014;15:100-104. doi:10.1037/a0031508

- Stoycos SA, Berzenski SR, Beck JG, et al. Predictors of treatment completion in group psychotherapy for male veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36:346-358. doi:10.1002/jts.22915

- Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9237-4

- Hunt MG, Rosenheck RA. Psychotherapy in mental health clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:561-573. doi:10.1002/jclp.20788

- Khatri N, Marziali E, Tchernikov I, et al. Comparing telehealth-based and clinic-based group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depression and anxiety: a pilot study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:765. doi:10.2147/cia.s57832

- Dangel J. Clinical resource hub increases veterans' access to care. VA News. January 12, 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://news.va.gov/137439/clinical-resource-hub-increases-access-to-care/

- Leung LB, Yoon J, Escarce JJ, et al. Primary care-mental health integration in the VA: shifting mental health services for common mental illnesses to primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:403-409. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700190

- Zhang A, Park S, Sullivan JE, et al. The effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for primary care patients’ depressive and/or anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:139-150. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170270

- Hundt NE, Barrera TL, Robinson A, et al. A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179:942-949. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-14-00128

- Jank R, Gallee A, Boeckle M, et al. Chronic pain and sleep disorders in primary care. Pain Res Treat. 2017;2017:1-9. doi:10.1155/2017/9081802

- Ashrafioun L, Bishop TM, Pigeon WR. The relationship between pain severity, insomnia, and suicide attempts among a national veteran sample initiating pain care. Psychosom Med. 2021;83:733- 738. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000975

- Ramanuj P, Ferenchik E, Docherty M, et al. Evolving models of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:1. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-0985-4

- Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83-90. doi:10.1037/a0020130

- Smith TL, Kim B, Benzer JK, et al. FLOW: early results from a clinical demonstration project to improve the transition of patients with mental health disorders back to primary care. Psychol Serv. 2021;18:23-32. doi:10.1037/ser0000336

- Kearney LK, Post EP, Pomerantz AS, et al. Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the department of veterans affairs transforming primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):399-408. doi:10.1037/a0035909

- US Government Accountability Office. Veterans health care: staffing challenges persist for fully integrating mental health and primary care services. December 15, 2022. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105372

- National Academies of Science and Engineering. Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24915/evaluation-of-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-mental-health-services

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Blueprint for excellence: achieving veterans’ excellence. October 6, 2014. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.volunteer.va.gov/docs/blueprintforexcellence_factsheet.PDF

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018-2024 strategic plan. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://www.calvet.ca.gov/Regulations/USDVA%20Strategic%20Plan%202018-2024.pdf

- Sripada RK, Bohnert KM, Ganoczy D, et al. Initial group versus individual therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and subsequent follow-up treatment adequacy. Psychol Serv. 2016;13:349-355. doi:10.1037/ser0000077

- Burnett-Zeigler IE, Pfeiffer P, Zivin K, et al. Psychotherapy utilization for acute depression within the Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:325-335. doi:10.1037/a0027957

- Kim JS, Prins A, Hirschhorn EW, et al. Preliminary investigation into the effectiveness of group webSTAIR for trauma-exposed veterans in primary care. Mil Med. 2024;189:e1403-e1408. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae052

- Jakupcak M, Blais RK, Grossbard J, et al. “Toughness” in association with mental health symptoms among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking Veterans Affairs health care. Psychol Men Masc. 2014;15:100-104. doi:10.1037/a0031508

- Stoycos SA, Berzenski SR, Beck JG, et al. Predictors of treatment completion in group psychotherapy for male veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2023;36:346-358. doi:10.1002/jts.22915

- Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9237-4

- Hunt MG, Rosenheck RA. Psychotherapy in mental health clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:561-573. doi:10.1002/jclp.20788

- Khatri N, Marziali E, Tchernikov I, et al. Comparing telehealth-based and clinic-based group cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depression and anxiety: a pilot study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:765. doi:10.2147/cia.s57832

- Dangel J. Clinical resource hub increases veterans' access to care. VA News. January 12, 2025. Accessed September 3, 2025. https://news.va.gov/137439/clinical-resource-hub-increases-access-to-care/

VIP Boot Camp: Expanding the Impact of VA Primary Care Mental Health With a Transdiagnostic Modular Group Program

VIP Boot Camp: Expanding the Impact of VA Primary Care Mental Health With a Transdiagnostic Modular Group Program

E-Consults Bridge to Interdisciplinary Team Care for Rural Appalachian Veterans With Chronic Pain and Opioid Use Disorder

E-Consults Bridge to Interdisciplinary Team Care for Rural Appalachian Veterans With Chronic Pain and Opioid Use Disorder

Rural veterans are prescribed long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain at higher rates than urban veterans, increasing their risk of developing opioid use disorder (OUD).1,2 Veterans with co-occurring OUD and chronic pain have more severe health concerns, as well as higher rates of homelessness, psychoactive drug misuse, and mental health disorders, compared to veterans with either chronic pain or OUD alone.3 Interdisciplinary team (IDT) care is recommended for both chronic pain and OUD.4,5 Rural veterans with co-occurring chronic pain and OUD, however, are often unable to access IDTs due to long travel and wait times. As a result, these rural veterans often receive care from primary care practitioners (PCPs) who lack training in pain management and addiction and have low confidence in their ability to provide optimal treatment.6,7

In the Veterans Health Administration, electronic consultations (e-consults) provide support to PCPs by recommending evidence-based approaches such as buprenorphine for OUD and pain IDTs for chronic pain.5,8 However, research on the use of e-consults to connect to IDT care for co-occurring chronic pain and OUD are lacking, as well as studies on IDTs using innovative methods (eg, shared appointments) to overcome treatment barriers (eg, multiple appointments) for rural veterans at higher risk for co-occurring OUD and chronic pain.

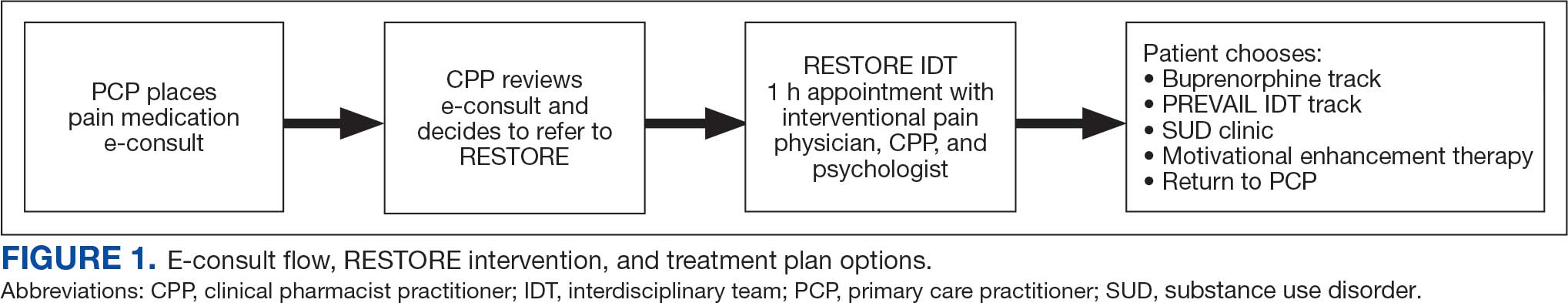

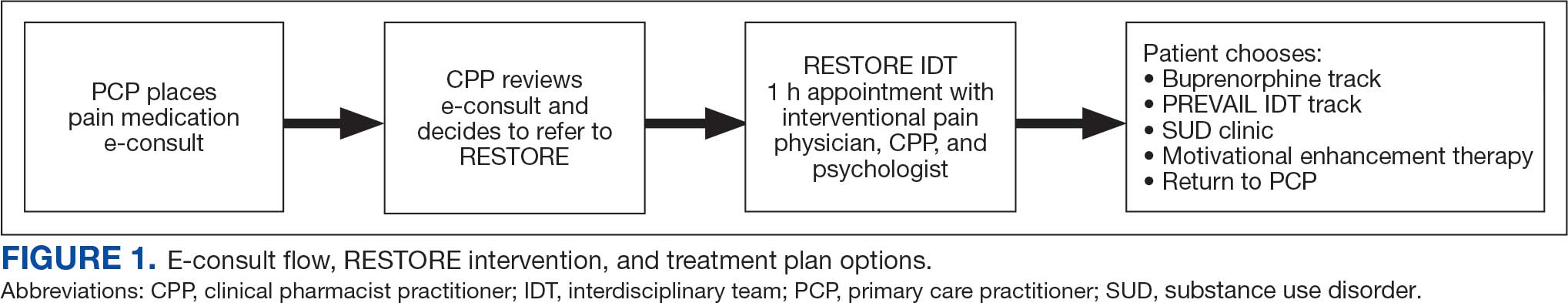

This quality improvement study sought to determine the feasibility and impact of a pharmacy e-consult service that provided pain medication recommendations and subsequent referrals to RESTORE, a shared appointment program with an IDT, for assessment and treatment of chronic pain and OUD.

Methods

This retrospective chart review was approved as nonresearch by the Institutional Review Board Chair at the Salem Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (SVAHS), a low-complexity medical center in Virginia that primarily serves a rural and highly rural Central Appalachian veteran population.

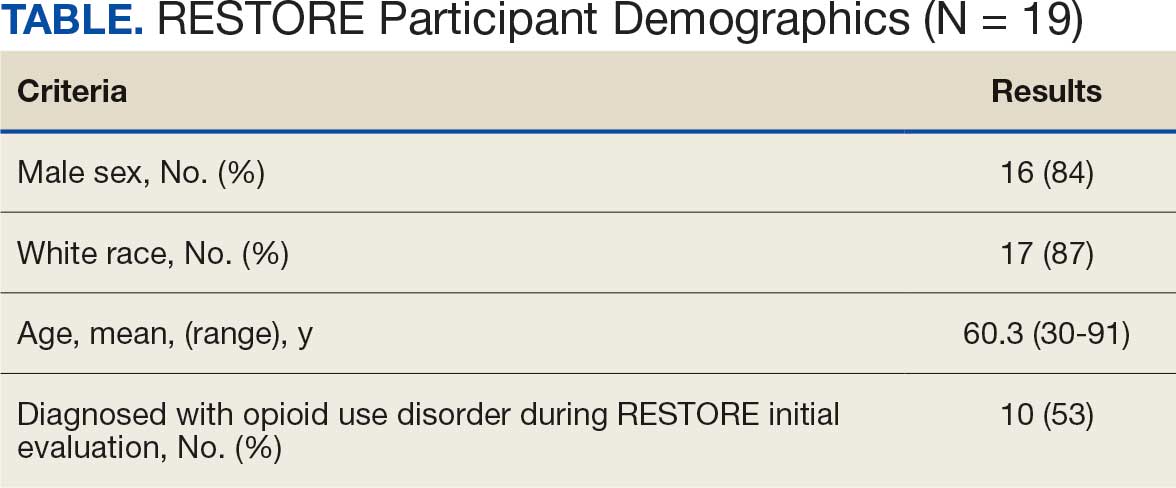

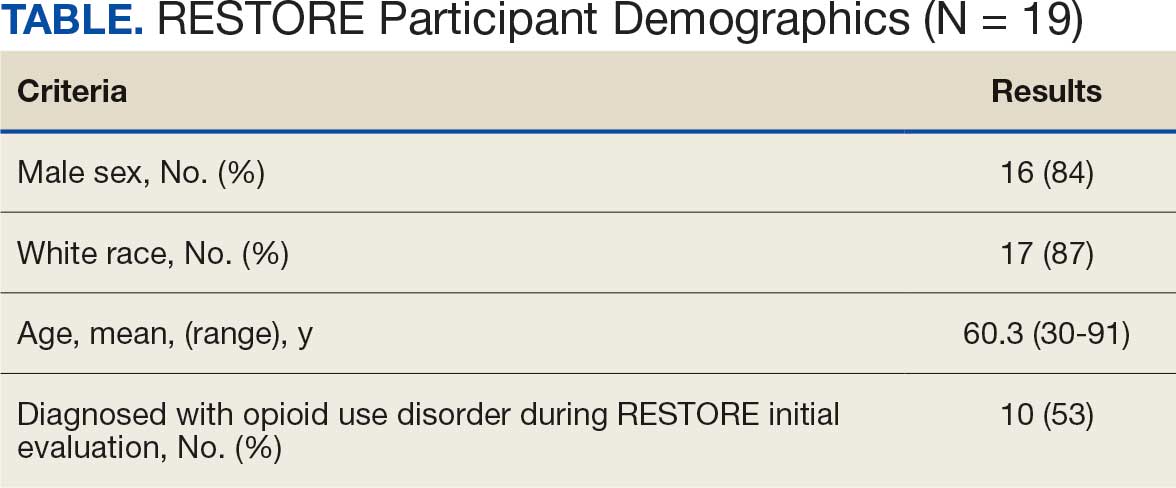

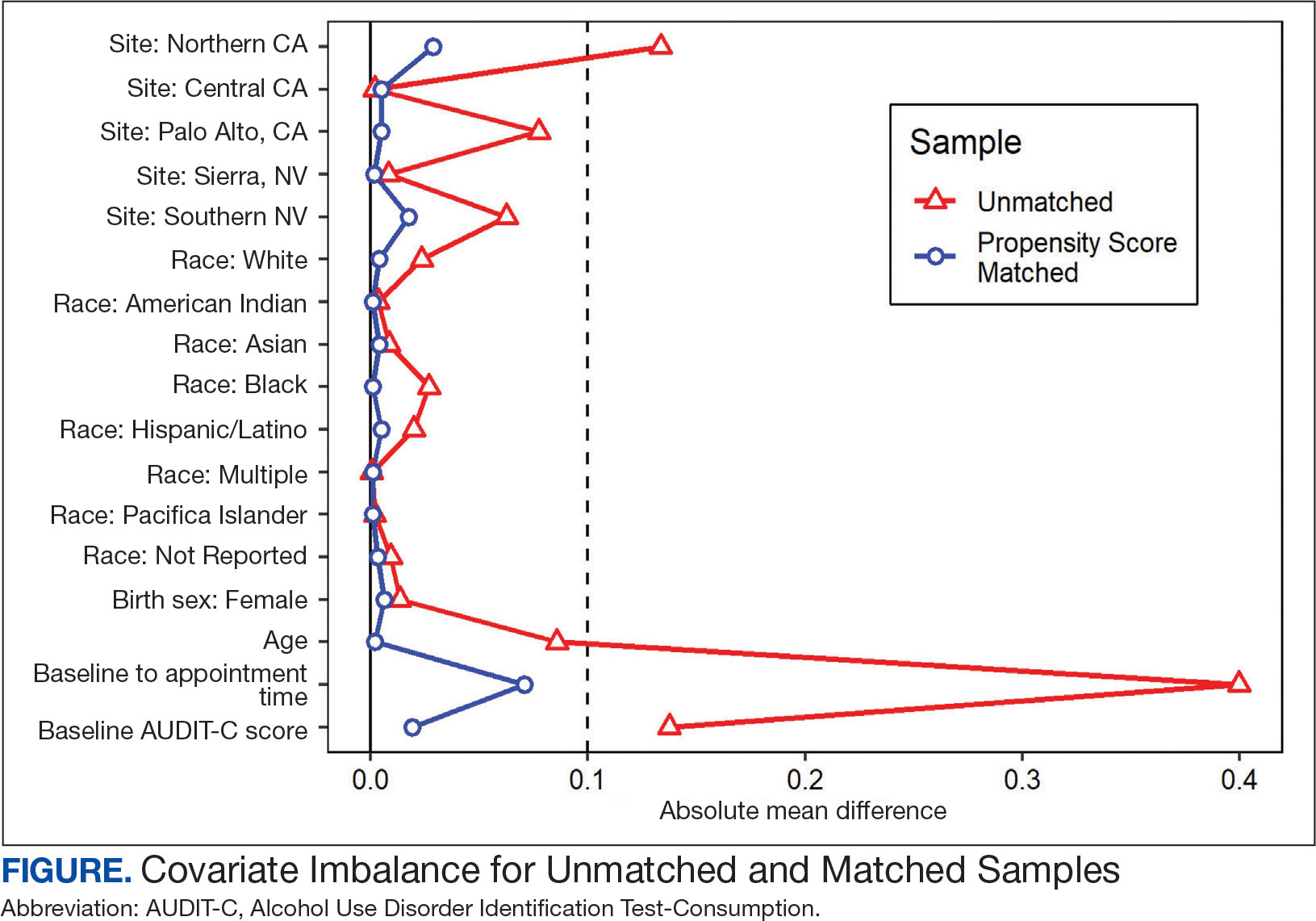

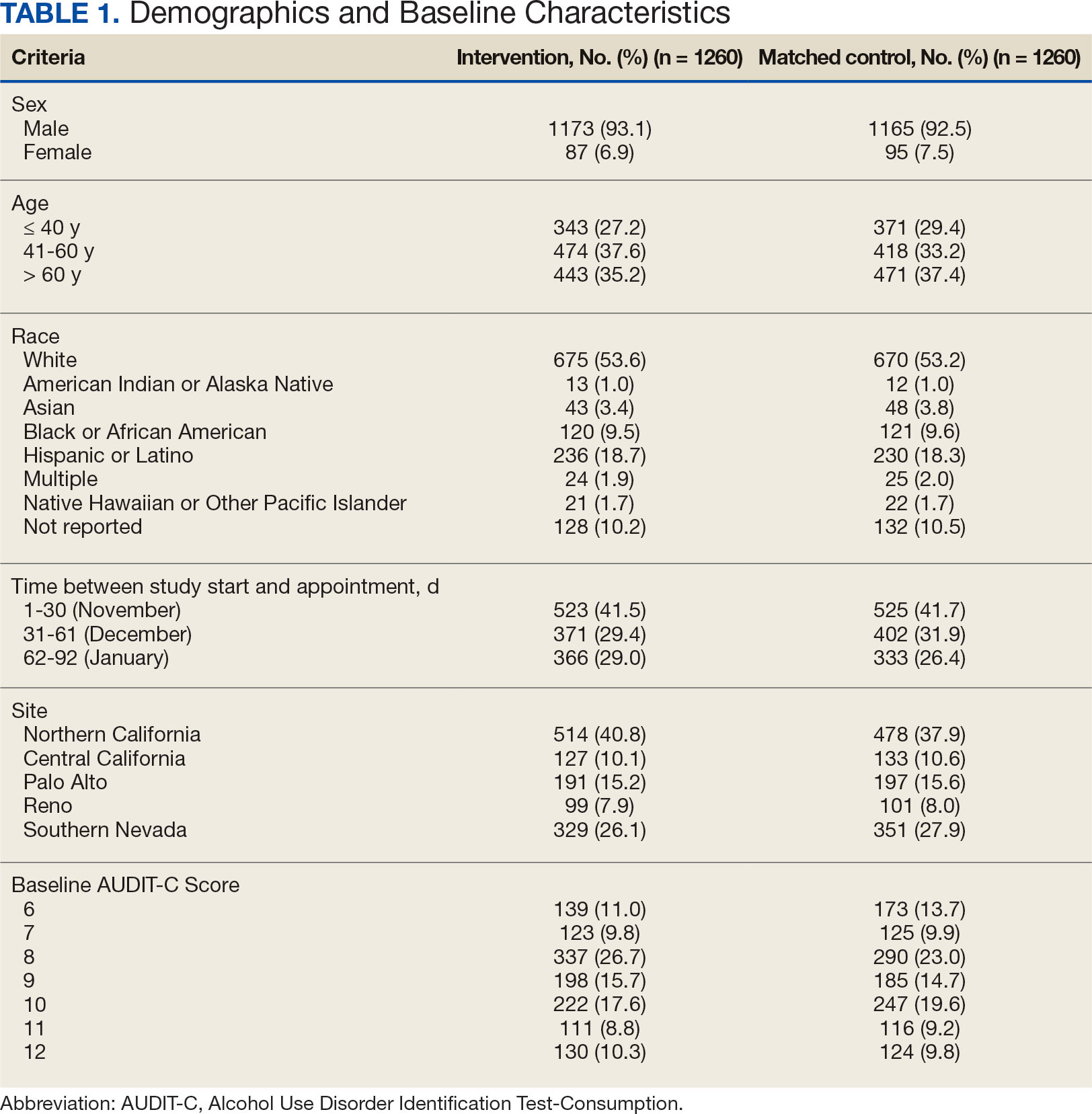

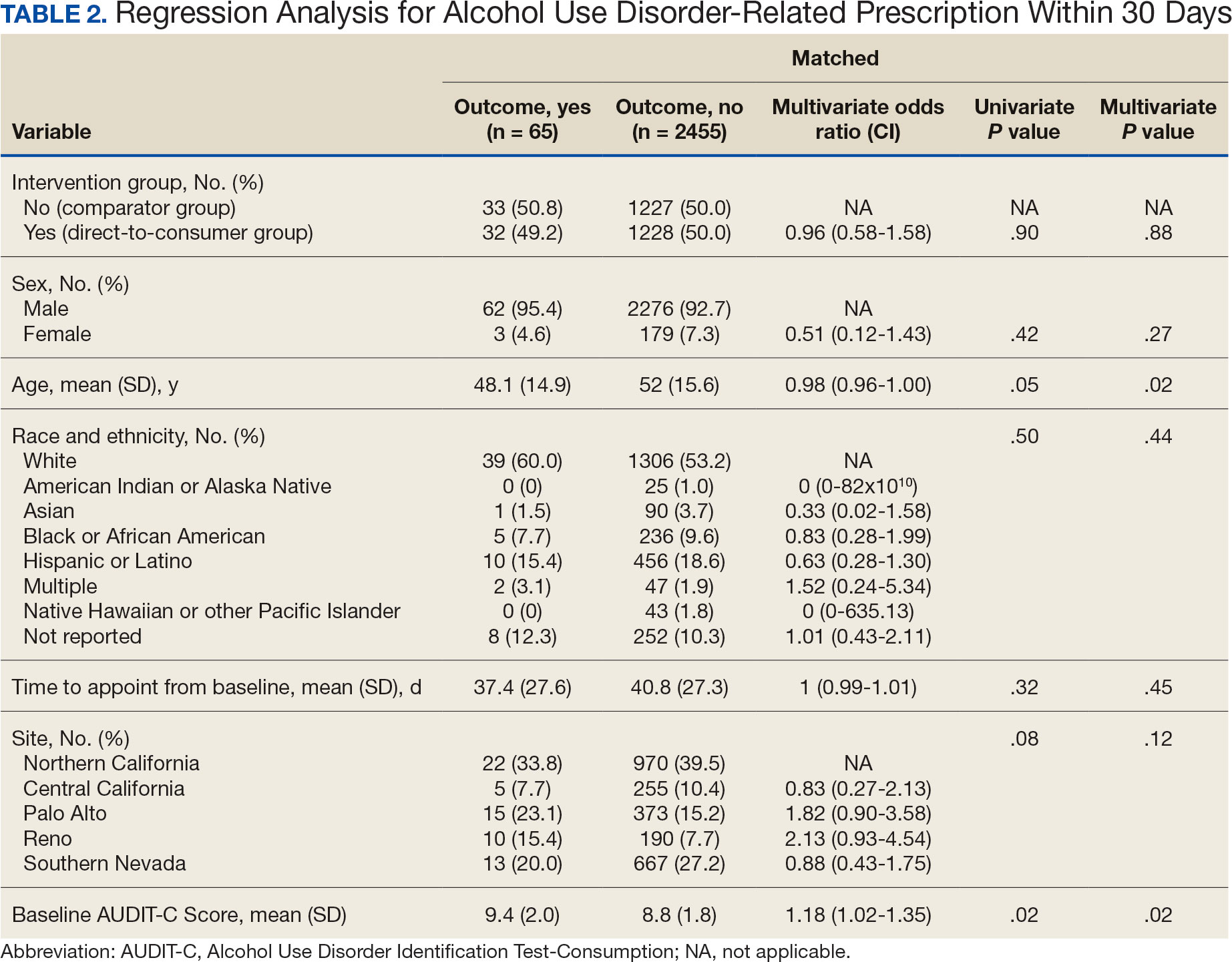

This study included veterans whose clinicians placed a pain medication e-consult requesting recommendations for medication adjustments and/or a referral to RESTORE from January 1, 2022, through January 6, 2023. Requests for services that could not be provided through an e-consult were excluded (Figure 1). Veterans who had a pain medication e-consult were identified in the SVAHS electronic medical record (EMR). Data extracted from the EMR included demographics, referral source, reason for referral, RESTORE appointment attendance, OUD diagnosis made during the RESTORE initial evaluation, implementation of medication recommendations by the referrer within 6 months, engagement in ≥ 3 pain education classes, and a shared appointment with a pain IDT within 6 months. Data were entered into a REDCap database, and descriptive statistics summarized the results. Feasibility was assessed by use of the e-consult by PCPs, attendance at the RESTORE appointment, and OUD diagnosis by the RESTORE team.

RESTORE Intervention

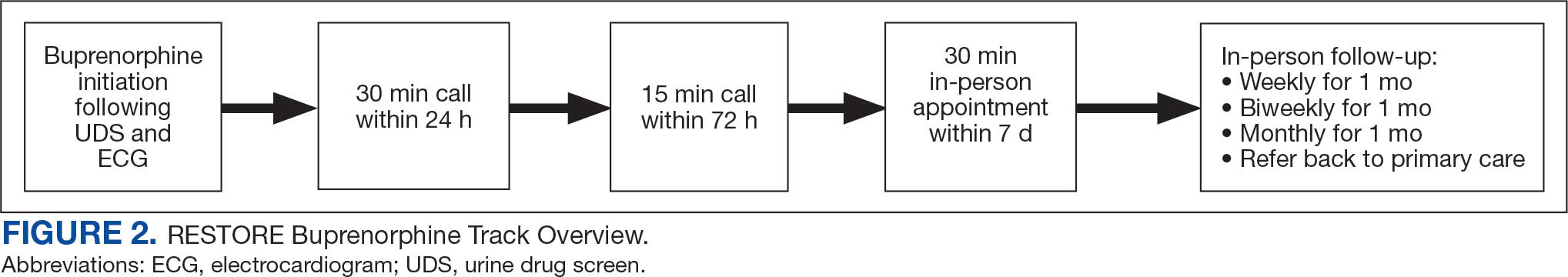

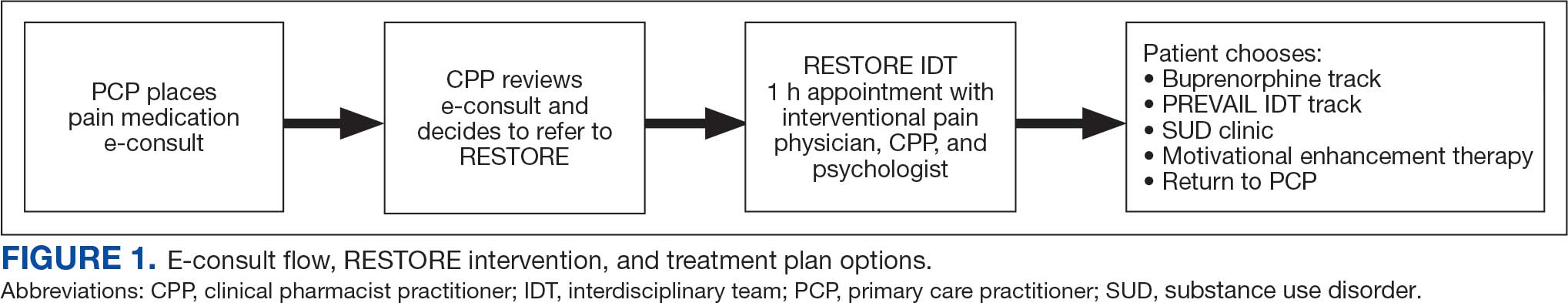

A pain medication e-consult was followed by referral to a shared appointment with the RESTORE IDT, with subsequent referrals to a pain IDT for chronic pain management if the veteran was amenable.

Pain medication e-consults in the EMR prompted a chart review by a clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP). Recommendations for changes to medication regimens were documented in the EMR. At completion of the e-consult, the referring clinician received an automated view alert.

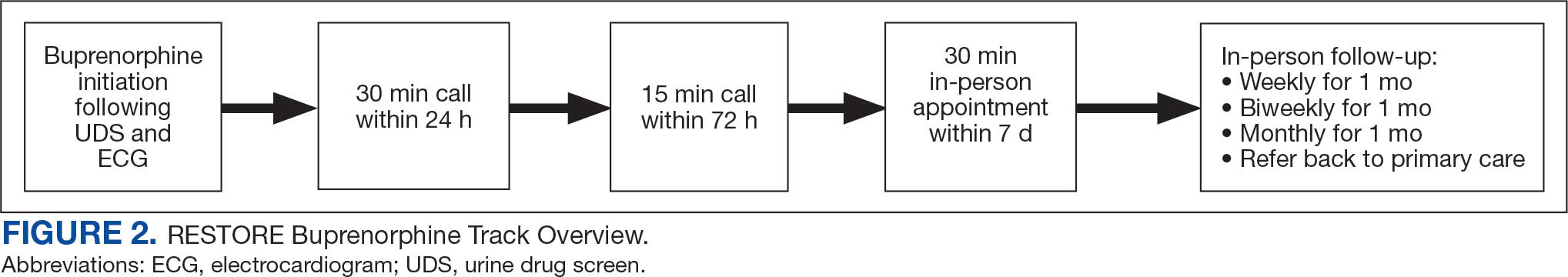

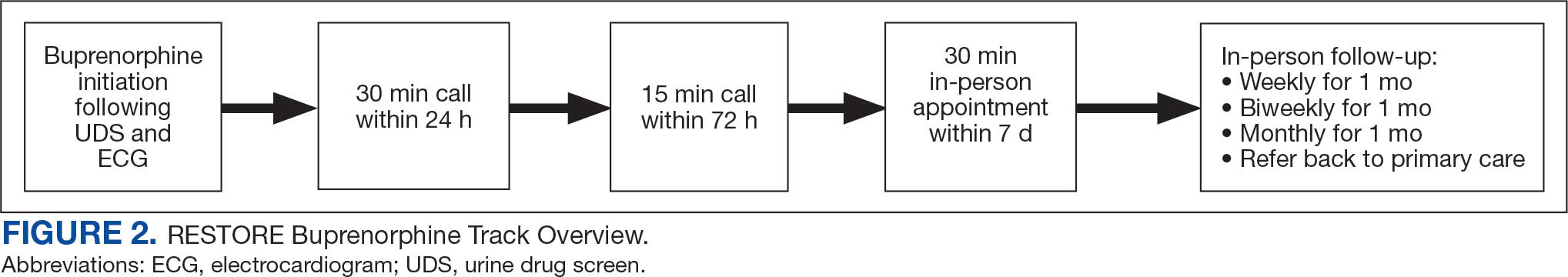

Veterans (and a support person, if preferred) were seen in a 60-minute, face-to-face shared appointment which included a psychologist, CPP, and pain physician. The psychologist conducted an OUD diagnostic interview, provided diagnostic feedback, and used motivational interviewing to provide psychoeducation on the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain, the IDT approach to chronic pain, and an overview of pain IDT care locally available. A CPP and physician then described medication options available to address OUD, if applicable. Together, the IDT and patient used shared decision making to determine a comprehensive treatment plan that may include a referral to the SVAHS PREVAIL Center for Chronic Pain IDT track (PREVAIL IDT track), a referral to substance use care in the case of polysubstance use, or medication initiation.9-11 If medication was prescribed, the patient was subsequently followed by the CPP through phone calls and face-to-face appointments at regularly scheduled intervals in coordination with the prescriber until they were stabilized. After stabilization, the prescription would be managed by their PCP (Figure 2). Veterans whose clinical condition changed significantly or worsened after returning to their PCP were invited to be reevaluated by the RESTORE team and restart care in that program. Individuals who were actively receiving RESTORE team care were discussed in a weekly care coordination meeting with all clinicians from both the PREVAIL and RESTORE teams.

Program Metrics

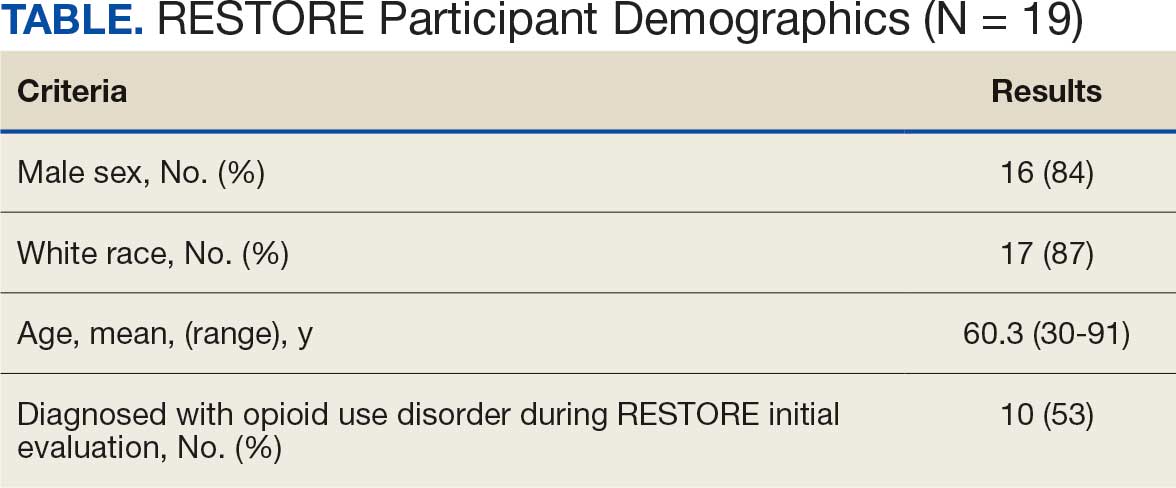

Pain medication e-consults were placed for 77 patients; 7 were excluded as inappropriate referral requests. Seventy (83%) e-consults were placed by PCPs (Table). Fifty-seven referring PCPs (81%) implemented ≥ 1 medication recommendation and 41 (59%) implemented all recommendations within 6 months. CPPs referred 19 individuals to RESTORE due to concerns related to high risk. All attended the initial evaluation appointment with the RESTORE team, 17 (89%) agreed to be referred to PREVAIL IDT track for nonpharmacologic pain care, and 9 (53%) engaged with that care within 6 months. Of those who attended RESTORE, 7 patients (37%) initiated buprenorphine for OUD with 6 (86%) being prescribed buprenorphine for ≥ 6 months.

Discussion

Most e-consults placed at SVAHS, which primarily serves a rural veteran population in Central Appalachia, resulted in veterans engaging in evidence-based treatment for co-occurring chronic pain and OUD. The use of e-consults and subsequent shared appointments with an IDT appears to be feasible, as the service was most often used by PCPs who often feel unequipped to manage chronic pain.7 The attendance rate for the RESTORE appointments was notable given the typically poor follow-up for patients with OUD. It supports the feasibility of a shared appointment approach which may overcome frequent barriers to care in this vulnerable population (ie, time, transportation). By attending 1 appointment with all clinicians present as opposed to multiple appointments, veterans experience fewer barriers than attending multiple appointments. RESTORE continues to be offered as an active clinical service whose implementation is now supported by changes to SVAHS policies. Since this study was conducted, the number of patients seen weekly has doubled and will soon be tripled based on high demand from PCPs.

While this study was limited to 1 site, had a small sample size, and was limited in scope, its results suggest that future research is warranted. Future studies using a larger sample size utilizing both a randomized control trial design and qualitative methods are needed to answer critical questions such as the role of patient characteristics on treatment effectiveness and the impact of the RESTORE model on long-term OUD medication adherence, patients’ perceptions and satisfaction, barriers to implementation, PCP confidence in providing pain care, and use of evidence-based nonpharmacologic pain management services.12-14

Conclusions

The results of this quality-improvement project suggest that e-consults may facilitate referrals to and patient follow-through with evidence-based treatment for co-occurring chronic pain and OUD among veterans living in rural communities in Central Appalachia who tend to experience significant barriers to traditional care and may require an innovative approach to facilitate effective treatment.

- Lund BC, Ohl ME, Hadlandsmyth K, et al. Regional and rural-urban variation in opioid prescribing in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(11-12):894-900. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz104

- Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, et al. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):557-564. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000021

- MacLean RR, Sofuoglu M, Stefanovics E, et al. Opioid use disorder with chronic pain increases disease burden and service use. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(1):157-165. doi:10.1037/ser0000607

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines: use of opioids in the management of chronic pain. Version 4.0. Updated May 2022. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOpioidsCPG.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Version 3.0. Updated February 2022. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/lbp/VADoDLBPCPGFinal508.pdf

- Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, et al. Systematic review of pain medicine content, teaching, and assessment in medical school curricula internationally. Pain Ther. 2018;7(2):139-161. doi:10.1007/s40122-018-0103-z

- Jamison RN, Scanlan E, Matthews ML, et al. Attitudes of primary care practitioners in managing chronic pain patients prescribed opioids for pain: a prospective longitudinal controlled trial. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):99-113. doi:10.1111/pme.12871

- Miller DM, Harvey TL. Pharmacist pain e-consults that result in a therapy change. Fed Pract. 2015;32(7):14-19.

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ. Chronic, noncancer pain care in the Veterans Administration: current trends and future directions. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(2):519-529. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.02.004

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ, Bolton R, et al. Using a whole health approach to build biopsychosocial-spiritual personal health plans for veterans with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2024;25(1):69-74. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2023.09.010

- Darnall BD, Edwards KA, Courtney RE, et al. Innovative treatment formats, technologies, and clinician trainings that improve access to behavioral pain treatment for youth and adults. Front Pain Res. 2023;4. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1223172

- Lister JJ, Weaver A, Ellis JD, et al. A systematic review of rural-specific barriers to medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46:273-288. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1694536

- Bhatraju EP, Radick AC, Leroux BG, et al. Buprenorphine adherence and illicit opioid use among patients in treatment for opioid use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2023;49. doi:10.1080/00952990.2023.2220876

- Courtney RE, Halsey E, Patil T, Mastronardi KV, Browne HS, Darnall BD. Prescription opioid tapering practices and outcomes at a rural VA health care system. Pain Med. 2024;25:480-482. doi:10.1093/pm/pnae013

Rural veterans are prescribed long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain at higher rates than urban veterans, increasing their risk of developing opioid use disorder (OUD).1,2 Veterans with co-occurring OUD and chronic pain have more severe health concerns, as well as higher rates of homelessness, psychoactive drug misuse, and mental health disorders, compared to veterans with either chronic pain or OUD alone.3 Interdisciplinary team (IDT) care is recommended for both chronic pain and OUD.4,5 Rural veterans with co-occurring chronic pain and OUD, however, are often unable to access IDTs due to long travel and wait times. As a result, these rural veterans often receive care from primary care practitioners (PCPs) who lack training in pain management and addiction and have low confidence in their ability to provide optimal treatment.6,7

In the Veterans Health Administration, electronic consultations (e-consults) provide support to PCPs by recommending evidence-based approaches such as buprenorphine for OUD and pain IDTs for chronic pain.5,8 However, research on the use of e-consults to connect to IDT care for co-occurring chronic pain and OUD are lacking, as well as studies on IDTs using innovative methods (eg, shared appointments) to overcome treatment barriers (eg, multiple appointments) for rural veterans at higher risk for co-occurring OUD and chronic pain.

This quality improvement study sought to determine the feasibility and impact of a pharmacy e-consult service that provided pain medication recommendations and subsequent referrals to RESTORE, a shared appointment program with an IDT, for assessment and treatment of chronic pain and OUD.

Methods

This retrospective chart review was approved as nonresearch by the Institutional Review Board Chair at the Salem Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (SVAHS), a low-complexity medical center in Virginia that primarily serves a rural and highly rural Central Appalachian veteran population.

This study included veterans whose clinicians placed a pain medication e-consult requesting recommendations for medication adjustments and/or a referral to RESTORE from January 1, 2022, through January 6, 2023. Requests for services that could not be provided through an e-consult were excluded (Figure 1). Veterans who had a pain medication e-consult were identified in the SVAHS electronic medical record (EMR). Data extracted from the EMR included demographics, referral source, reason for referral, RESTORE appointment attendance, OUD diagnosis made during the RESTORE initial evaluation, implementation of medication recommendations by the referrer within 6 months, engagement in ≥ 3 pain education classes, and a shared appointment with a pain IDT within 6 months. Data were entered into a REDCap database, and descriptive statistics summarized the results. Feasibility was assessed by use of the e-consult by PCPs, attendance at the RESTORE appointment, and OUD diagnosis by the RESTORE team.

RESTORE Intervention

A pain medication e-consult was followed by referral to a shared appointment with the RESTORE IDT, with subsequent referrals to a pain IDT for chronic pain management if the veteran was amenable.

Pain medication e-consults in the EMR prompted a chart review by a clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP). Recommendations for changes to medication regimens were documented in the EMR. At completion of the e-consult, the referring clinician received an automated view alert.