User login

Does Extended Postop Follow-Up Improve Survival in Gastric Cancer?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Currently, postgastrectomy cancer surveillance typically lasts 5 years, although some centers now monitor patients beyond this point.

- To investigate the potential benefit of extended surveillance, researchers used Korean National Health Insurance claims data to identify 40,468 patients with gastric cancer who were disease free 5 years after gastrectomy — 14,294 received extended regular follow-up visits and 26,174 did not.

- The extended regular follow-up group was defined as having endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT between 2 months and 2 years before diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer and having two or more examinations between 5.5 and 8.5 years after gastrectomy. Late recurrence was a recurrence diagnosed 5 years after gastrectomy.

- Researchers used Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the independent association between follow-up and overall and postrecurrence survival rates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 5 years postgastrectomy, the incidence of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer was 7.8% — 4.0% between 5 and 10 years (1610 of 40,468 patients) and 9.4% after 10 years (1528 of 16,287 patients).

- Regular follow-up beyond 5 years was associated with a significant reduction in overall mortality — from 49.4% to 36.9% at 15 years (P < .001). Overall survival after late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer also improved significantly with extended regular follow-up, with the 5-year postrecurrence survival rate increasing from 32.7% to 71.1% (P < .001).

- The combination of endoscopy and abdominopelvic CT provided the highest 5-year postrecurrence survival rate (74.5%), compared with endoscopy alone (54.5%) or CT alone (47.1%).

- A time interval of more than 2 years between a previous endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT and diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer significantly decreased postrecurrence survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.72 for endoscopy and HR, 1.48 for abdominopelvic CT).

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that extended regular follow-up after 5 years post gastrectomy should be implemented clinically and that current practice and value of follow-up protocols in postoperative care of patients with gastric cancer be reconsidered,” the authors concluded.

The authors of an accompanying commentary cautioned that, while the study “successfully establishes groundwork for extending surveillance of gastric cancer in high-risk populations, more work is needed to strategically identify those who would benefit most from extended surveillance.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Ju-Hee Lee, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and accompanying commentary were published online on June 18 in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Recurrent cancer and gastric remnant cancer could not be distinguished from each other because clinical records were not analyzed. The claims database lacked detailed clinical information on individual patients, including cancer stages, and a separate analysis of tumor markers could not be performed.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by a grant from the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. The study authors and commentary authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Currently, postgastrectomy cancer surveillance typically lasts 5 years, although some centers now monitor patients beyond this point.

- To investigate the potential benefit of extended surveillance, researchers used Korean National Health Insurance claims data to identify 40,468 patients with gastric cancer who were disease free 5 years after gastrectomy — 14,294 received extended regular follow-up visits and 26,174 did not.

- The extended regular follow-up group was defined as having endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT between 2 months and 2 years before diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer and having two or more examinations between 5.5 and 8.5 years after gastrectomy. Late recurrence was a recurrence diagnosed 5 years after gastrectomy.

- Researchers used Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the independent association between follow-up and overall and postrecurrence survival rates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 5 years postgastrectomy, the incidence of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer was 7.8% — 4.0% between 5 and 10 years (1610 of 40,468 patients) and 9.4% after 10 years (1528 of 16,287 patients).

- Regular follow-up beyond 5 years was associated with a significant reduction in overall mortality — from 49.4% to 36.9% at 15 years (P < .001). Overall survival after late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer also improved significantly with extended regular follow-up, with the 5-year postrecurrence survival rate increasing from 32.7% to 71.1% (P < .001).

- The combination of endoscopy and abdominopelvic CT provided the highest 5-year postrecurrence survival rate (74.5%), compared with endoscopy alone (54.5%) or CT alone (47.1%).

- A time interval of more than 2 years between a previous endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT and diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer significantly decreased postrecurrence survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.72 for endoscopy and HR, 1.48 for abdominopelvic CT).

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that extended regular follow-up after 5 years post gastrectomy should be implemented clinically and that current practice and value of follow-up protocols in postoperative care of patients with gastric cancer be reconsidered,” the authors concluded.

The authors of an accompanying commentary cautioned that, while the study “successfully establishes groundwork for extending surveillance of gastric cancer in high-risk populations, more work is needed to strategically identify those who would benefit most from extended surveillance.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Ju-Hee Lee, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and accompanying commentary were published online on June 18 in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Recurrent cancer and gastric remnant cancer could not be distinguished from each other because clinical records were not analyzed. The claims database lacked detailed clinical information on individual patients, including cancer stages, and a separate analysis of tumor markers could not be performed.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by a grant from the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. The study authors and commentary authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Currently, postgastrectomy cancer surveillance typically lasts 5 years, although some centers now monitor patients beyond this point.

- To investigate the potential benefit of extended surveillance, researchers used Korean National Health Insurance claims data to identify 40,468 patients with gastric cancer who were disease free 5 years after gastrectomy — 14,294 received extended regular follow-up visits and 26,174 did not.

- The extended regular follow-up group was defined as having endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT between 2 months and 2 years before diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer and having two or more examinations between 5.5 and 8.5 years after gastrectomy. Late recurrence was a recurrence diagnosed 5 years after gastrectomy.

- Researchers used Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the independent association between follow-up and overall and postrecurrence survival rates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 5 years postgastrectomy, the incidence of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer was 7.8% — 4.0% between 5 and 10 years (1610 of 40,468 patients) and 9.4% after 10 years (1528 of 16,287 patients).

- Regular follow-up beyond 5 years was associated with a significant reduction in overall mortality — from 49.4% to 36.9% at 15 years (P < .001). Overall survival after late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer also improved significantly with extended regular follow-up, with the 5-year postrecurrence survival rate increasing from 32.7% to 71.1% (P < .001).

- The combination of endoscopy and abdominopelvic CT provided the highest 5-year postrecurrence survival rate (74.5%), compared with endoscopy alone (54.5%) or CT alone (47.1%).

- A time interval of more than 2 years between a previous endoscopy or abdominopelvic CT and diagnosis of late recurrence or gastric remnant cancer significantly decreased postrecurrence survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.72 for endoscopy and HR, 1.48 for abdominopelvic CT).

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that extended regular follow-up after 5 years post gastrectomy should be implemented clinically and that current practice and value of follow-up protocols in postoperative care of patients with gastric cancer be reconsidered,” the authors concluded.

The authors of an accompanying commentary cautioned that, while the study “successfully establishes groundwork for extending surveillance of gastric cancer in high-risk populations, more work is needed to strategically identify those who would benefit most from extended surveillance.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Ju-Hee Lee, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and accompanying commentary were published online on June 18 in JAMA Surgery.

LIMITATIONS:

Recurrent cancer and gastric remnant cancer could not be distinguished from each other because clinical records were not analyzed. The claims database lacked detailed clinical information on individual patients, including cancer stages, and a separate analysis of tumor markers could not be performed.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by a grant from the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. The study authors and commentary authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Factors Linked to Complete Response, Survival in Pancreatic Cancer

TOPLINE:

a multicenter cohort study found. Several factors, including treatment type and tumor features, influenced the outcomes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Preoperative chemo(radio)therapy is increasingly used in patients with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma and may improve the chance of a pathologic complete response. Achieving a pathologic complete response is associated with improved overall survival.

- However, the evidence on pathologic complete response is based on large national databases or small single-center series. Multicenter studies with in-depth data about complete response are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers investigated the incidence and factors associated with pathologic complete response after preoperative chemo(radio)therapy among 1758 patients (mean age, 64 years; 50% men) with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection after two or more cycles of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy).

- Patients were treated at 19 centers in eight countries. The median follow-up was 19 months. Pathologic complete response was defined as the absence of vital tumor cells in the patient’s sampled pancreas specimen after resection.

- Factors associated with overall survival and pathologic complete response were investigated with Cox proportional hazards and logistic regression models, respectively.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that the rate of pathologic complete response was 4.8% in patients who received chemo(radio)therapy before pancreatic cancer resection.

- Having a pathologic complete response was associated with a 54% lower risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.46). At 5 years, the overall survival rate was 63% in patients with a pathologic complete response vs 30% in patients without one.

- More patients who received preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX achieved a pathologic complete response (58.8% vs 44.7%). Other factors associated with pathologic complete response included tumors located in the pancreatic head (odds ratio [OR], 2.51), tumors > 40 mm at diagnosis (OR, 2.58), partial or complete radiologic response (OR, 13.0), and normal(ized) serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 after preoperative therapy (OR, 3.76).

- Preoperative radiotherapy (OR, 2.03) and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy (OR, 8.91) were also associated with a pathologic complete response; however, preoperative radiotherapy did not improve overall survival, and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy was independently associated with worse overall survival. These findings suggest that a pathologic complete response might not always reflect an optimal disease response.

IN PRACTICE:

Although pathologic complete response does not reflect cure, it is associated with better overall survival, the authors wrote. Factors associated with a pathologic complete response may inform treatment decisions.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Thomas F. Stoop, MD, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, was published online on June 18 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had several limitations. The sample size and the limited number of events precluded comparative subanalyses, as well as a more detailed stratification for preoperative chemotherapy regimens. Information about patients’ race and the presence of BRCA germline mutations, both of which seem to be relevant to the chance of achieving a major pathologic response, was not collected or available.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding was noted. Several coauthors have industry relationships outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

a multicenter cohort study found. Several factors, including treatment type and tumor features, influenced the outcomes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Preoperative chemo(radio)therapy is increasingly used in patients with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma and may improve the chance of a pathologic complete response. Achieving a pathologic complete response is associated with improved overall survival.

- However, the evidence on pathologic complete response is based on large national databases or small single-center series. Multicenter studies with in-depth data about complete response are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers investigated the incidence and factors associated with pathologic complete response after preoperative chemo(radio)therapy among 1758 patients (mean age, 64 years; 50% men) with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection after two or more cycles of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy).

- Patients were treated at 19 centers in eight countries. The median follow-up was 19 months. Pathologic complete response was defined as the absence of vital tumor cells in the patient’s sampled pancreas specimen after resection.

- Factors associated with overall survival and pathologic complete response were investigated with Cox proportional hazards and logistic regression models, respectively.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that the rate of pathologic complete response was 4.8% in patients who received chemo(radio)therapy before pancreatic cancer resection.

- Having a pathologic complete response was associated with a 54% lower risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.46). At 5 years, the overall survival rate was 63% in patients with a pathologic complete response vs 30% in patients without one.

- More patients who received preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX achieved a pathologic complete response (58.8% vs 44.7%). Other factors associated with pathologic complete response included tumors located in the pancreatic head (odds ratio [OR], 2.51), tumors > 40 mm at diagnosis (OR, 2.58), partial or complete radiologic response (OR, 13.0), and normal(ized) serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 after preoperative therapy (OR, 3.76).

- Preoperative radiotherapy (OR, 2.03) and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy (OR, 8.91) were also associated with a pathologic complete response; however, preoperative radiotherapy did not improve overall survival, and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy was independently associated with worse overall survival. These findings suggest that a pathologic complete response might not always reflect an optimal disease response.

IN PRACTICE:

Although pathologic complete response does not reflect cure, it is associated with better overall survival, the authors wrote. Factors associated with a pathologic complete response may inform treatment decisions.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Thomas F. Stoop, MD, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, was published online on June 18 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had several limitations. The sample size and the limited number of events precluded comparative subanalyses, as well as a more detailed stratification for preoperative chemotherapy regimens. Information about patients’ race and the presence of BRCA germline mutations, both of which seem to be relevant to the chance of achieving a major pathologic response, was not collected or available.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding was noted. Several coauthors have industry relationships outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

a multicenter cohort study found. Several factors, including treatment type and tumor features, influenced the outcomes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Preoperative chemo(radio)therapy is increasingly used in patients with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma and may improve the chance of a pathologic complete response. Achieving a pathologic complete response is associated with improved overall survival.

- However, the evidence on pathologic complete response is based on large national databases or small single-center series. Multicenter studies with in-depth data about complete response are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers investigated the incidence and factors associated with pathologic complete response after preoperative chemo(radio)therapy among 1758 patients (mean age, 64 years; 50% men) with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection after two or more cycles of chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy).

- Patients were treated at 19 centers in eight countries. The median follow-up was 19 months. Pathologic complete response was defined as the absence of vital tumor cells in the patient’s sampled pancreas specimen after resection.

- Factors associated with overall survival and pathologic complete response were investigated with Cox proportional hazards and logistic regression models, respectively.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that the rate of pathologic complete response was 4.8% in patients who received chemo(radio)therapy before pancreatic cancer resection.

- Having a pathologic complete response was associated with a 54% lower risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.46). At 5 years, the overall survival rate was 63% in patients with a pathologic complete response vs 30% in patients without one.

- More patients who received preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX achieved a pathologic complete response (58.8% vs 44.7%). Other factors associated with pathologic complete response included tumors located in the pancreatic head (odds ratio [OR], 2.51), tumors > 40 mm at diagnosis (OR, 2.58), partial or complete radiologic response (OR, 13.0), and normal(ized) serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 after preoperative therapy (OR, 3.76).

- Preoperative radiotherapy (OR, 2.03) and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy (OR, 8.91) were also associated with a pathologic complete response; however, preoperative radiotherapy did not improve overall survival, and preoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy was independently associated with worse overall survival. These findings suggest that a pathologic complete response might not always reflect an optimal disease response.

IN PRACTICE:

Although pathologic complete response does not reflect cure, it is associated with better overall survival, the authors wrote. Factors associated with a pathologic complete response may inform treatment decisions.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Thomas F. Stoop, MD, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, was published online on June 18 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had several limitations. The sample size and the limited number of events precluded comparative subanalyses, as well as a more detailed stratification for preoperative chemotherapy regimens. Information about patients’ race and the presence of BRCA germline mutations, both of which seem to be relevant to the chance of achieving a major pathologic response, was not collected or available.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding was noted. Several coauthors have industry relationships outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy: Improvements and Considerations

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

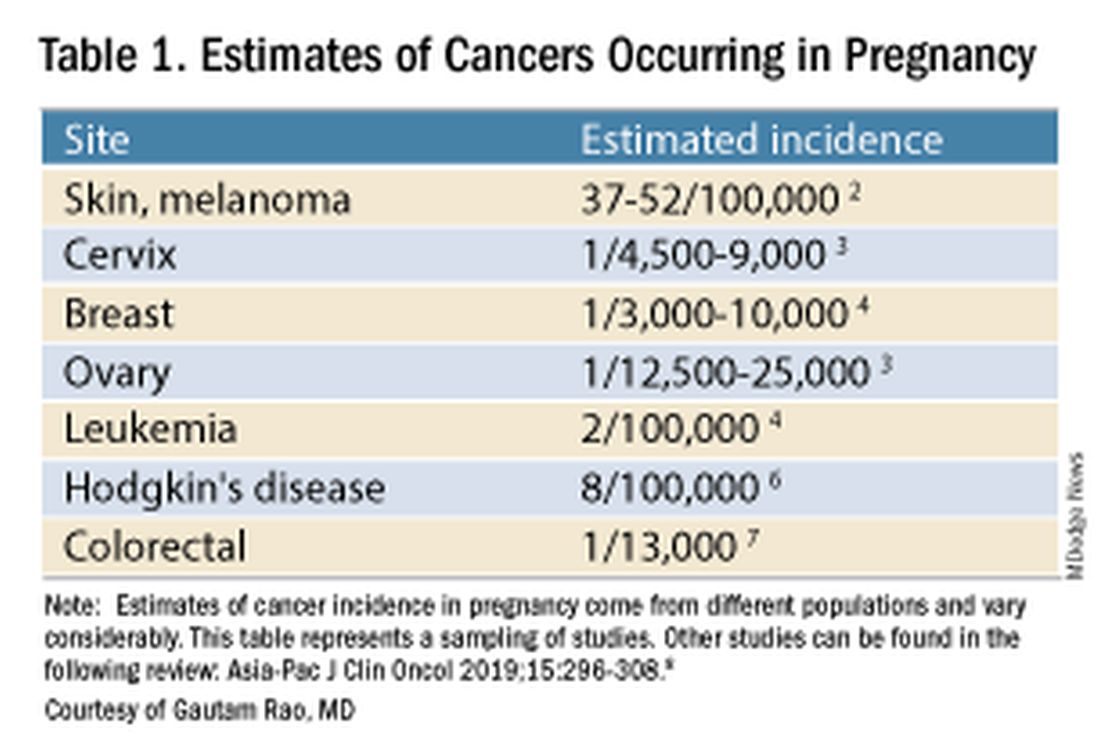

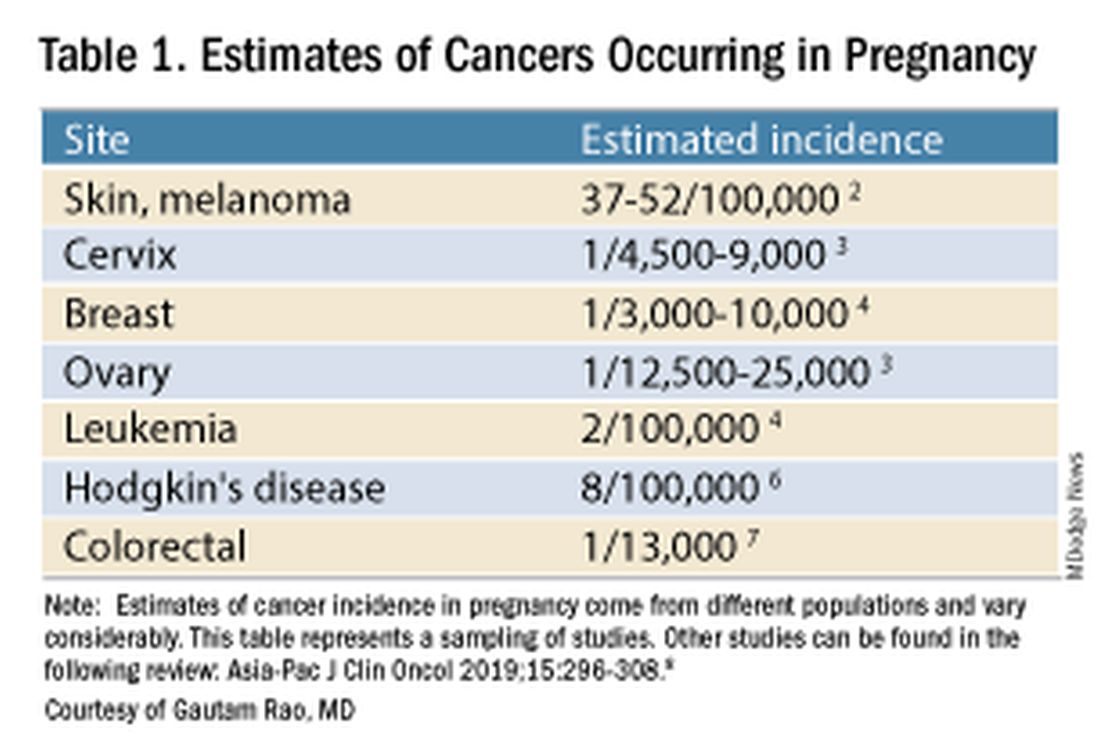

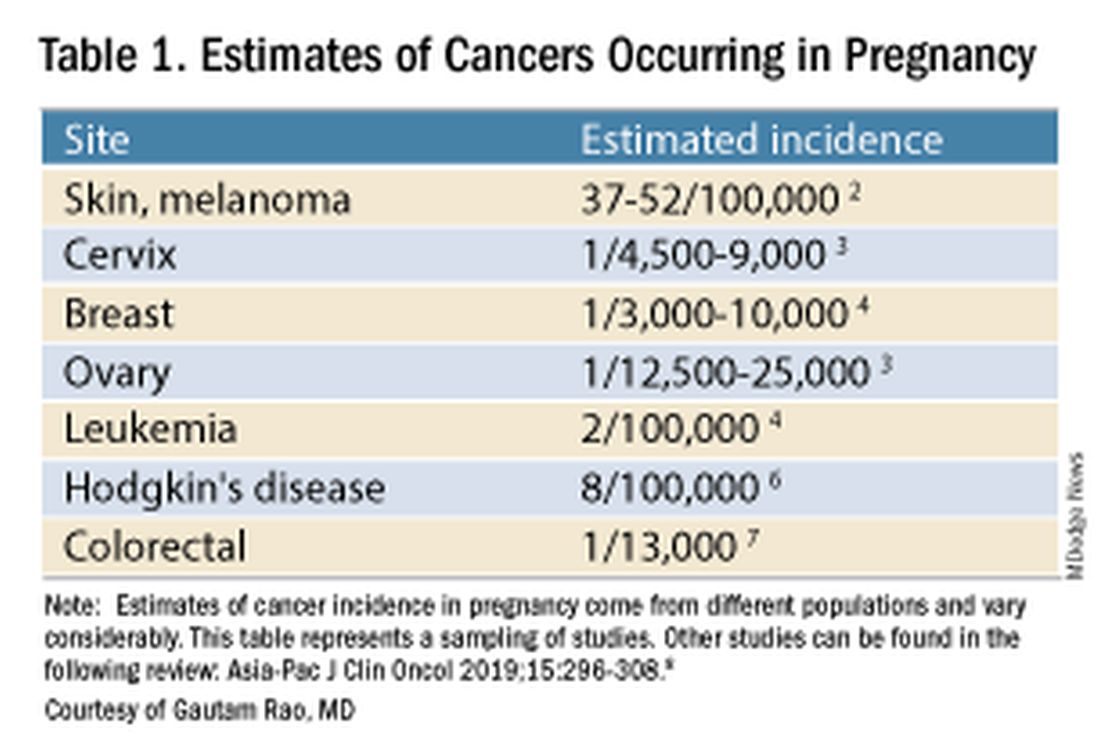

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

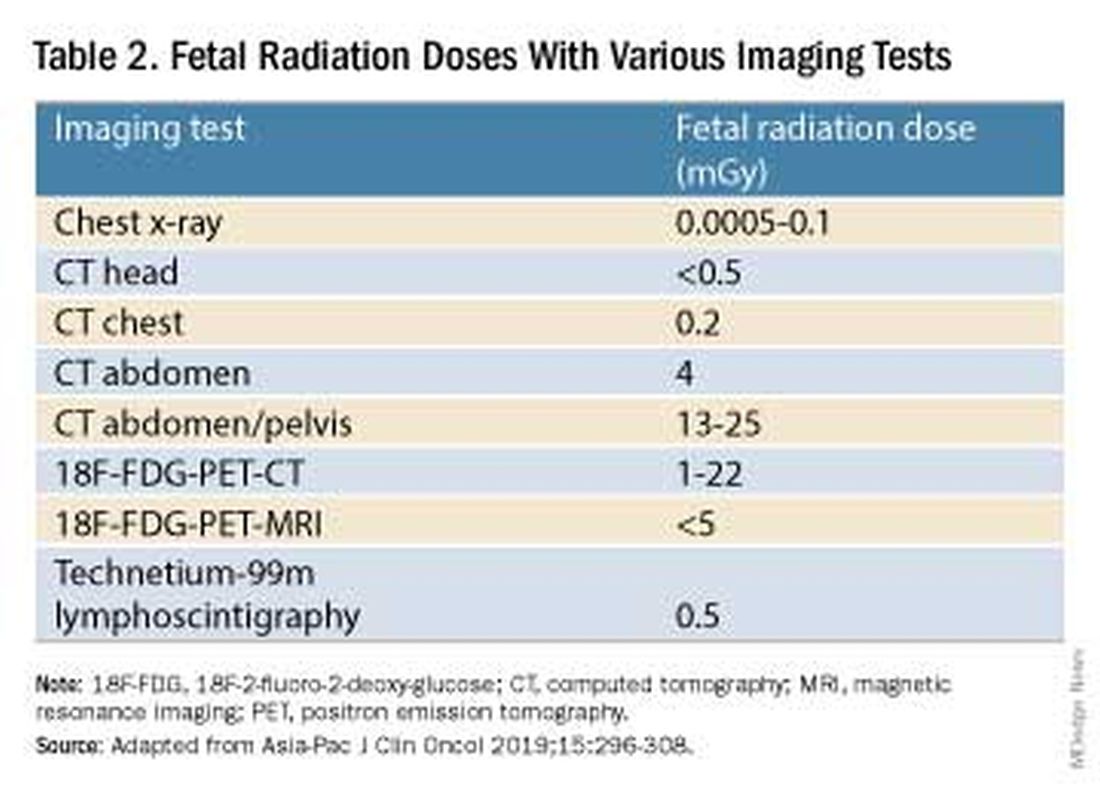

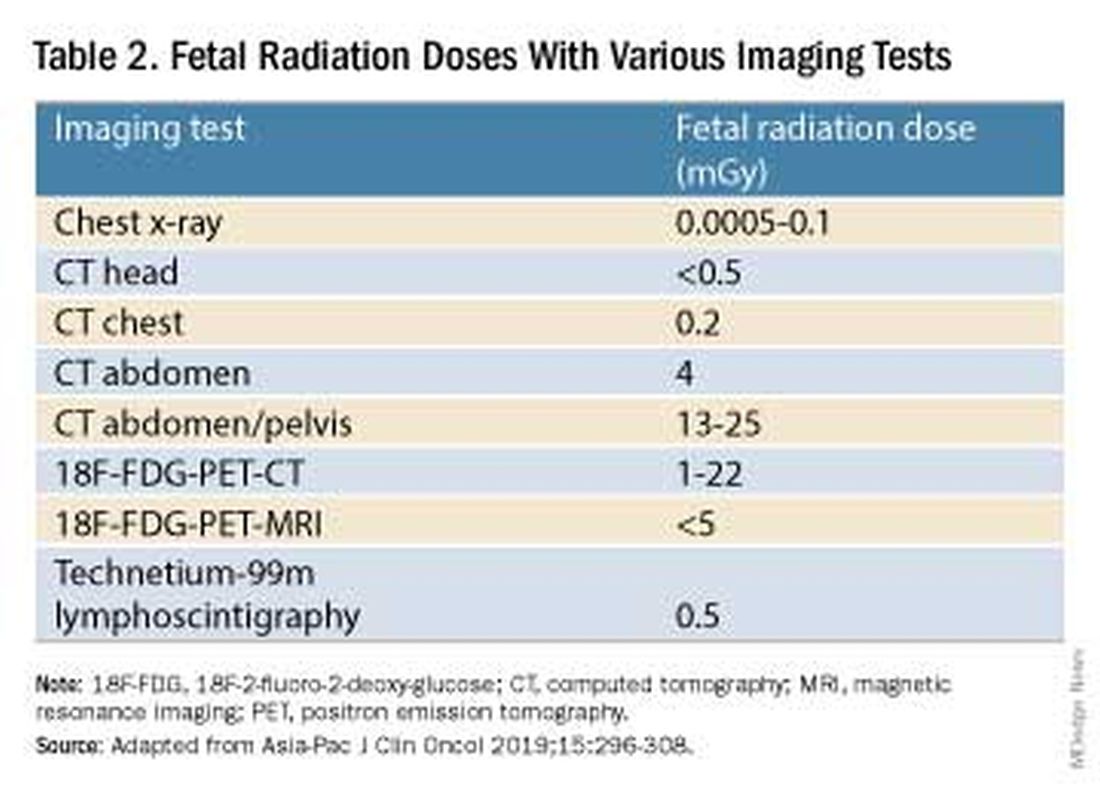

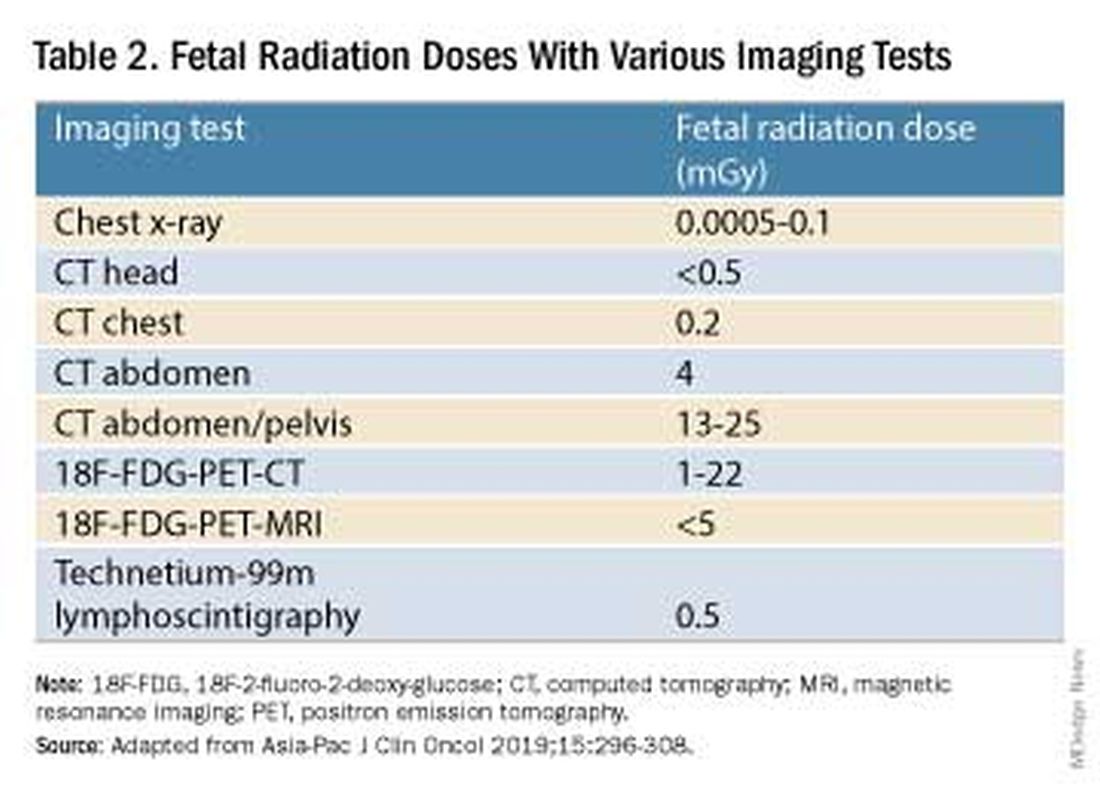

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

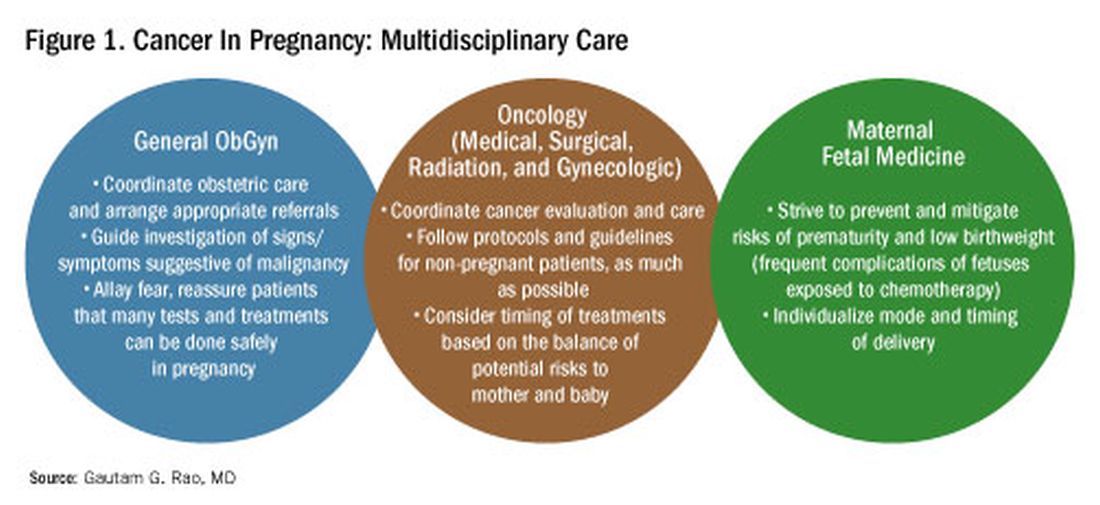

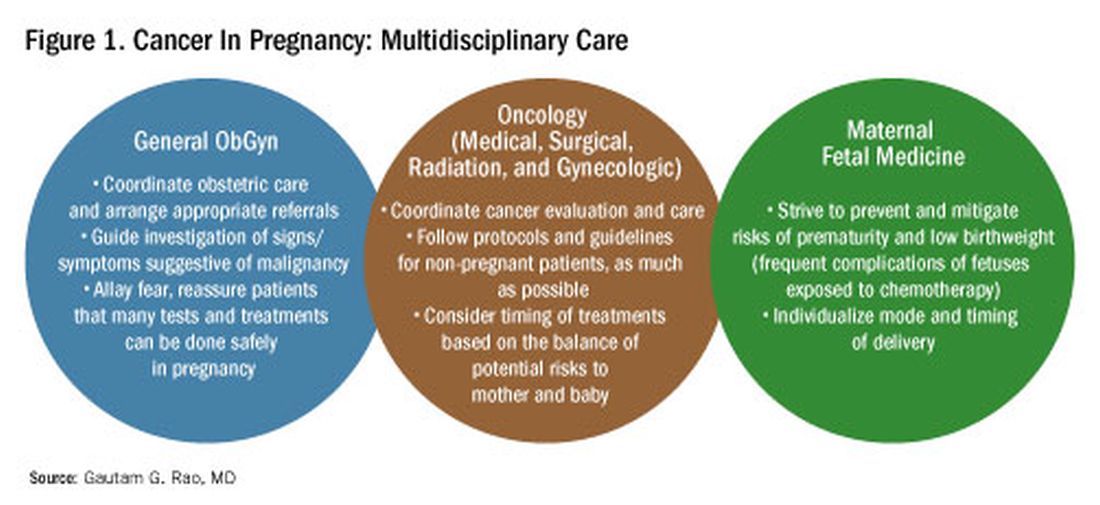

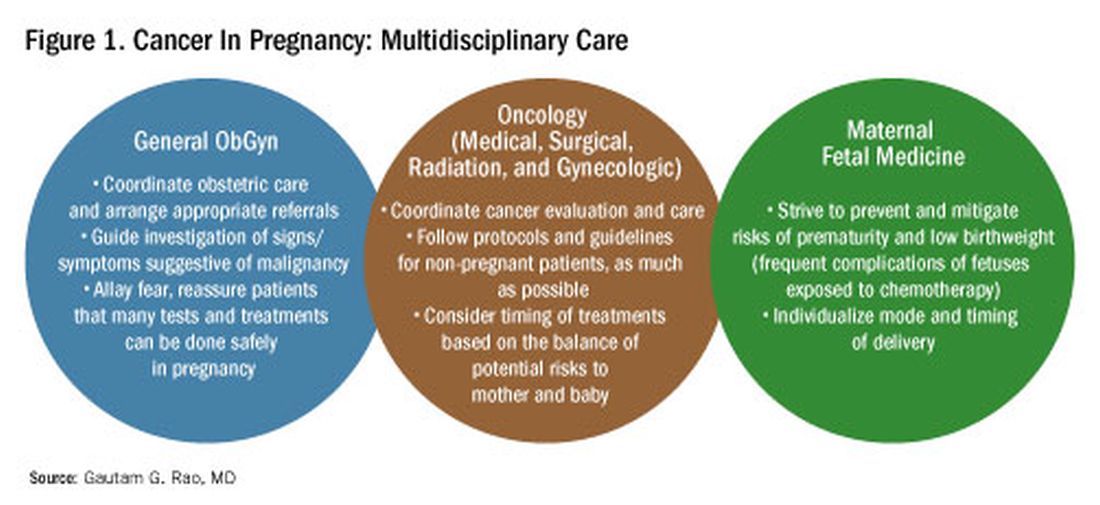

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Genetics and Lifestyle Choices Can Affect Early Prostate Cancer Deaths

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- About one third of men die from prostate cancer before age 75, highlighting the need for prevention strategies that target high-risk populations.

- In the current study, researchers analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies — the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study (MDCS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) — which included 19,607 men with a median age at inclusion of 59 years (MDCS) and 65.1 years (HPFS) followed from 1991 to 2019.

- Participants were categorized by genetic risk and lifestyle score. Genetic risk was defined using a multiancestry polygenic risk score (PRS) for overall prostate cancer that included 400 genetic risk variants.

- A healthy lifestyle score was defined as 3-6, while an unhealthy lifestyle score was 0-2. Lifestyle factors included smoking, weight, physical activity, and diet.

- The researchers calculated hazard ratios (HRs) for the association between genetic and lifestyle factors and prostate cancer death.

TAKEAWAY:

- Combining the PRS and family history of cancer, 67% of men overall (13,186 of 19,607) were considered to have higher genetic risk, and about 30% overall had an unhealthy lifestyle score of 0-2.

- Men at higher genetic risk accounted for 88% (94 of 107) of early prostate cancer deaths.

- Compared with men at lower genetic risk, those at higher genetic risk had more than a threefold higher rate of early prostate cancer death (HR, 3.26) and more than a twofold increased rate of late prostate cancer death (HR, 2.26) as well as a higher lifetime risk for prostate cancer death.

- Among men at higher genetic risk, an unhealthy lifestyle was associated with a higher risk of early prostate cancer death, with smoking and a BMI of ≥ 30 being significant factors. Depending on the definition of a healthy lifestyle, the researchers estimated that 22%-36% of early prostate cancer deaths among men at higher genetic risk might be preventable.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on data from two prospective cohort studies, this analysis provides evidence for targeting men at increased genetic risk with prevention strategies aimed at reducing premature deaths from prostate cancer,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Anna Plym, PhD, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, was published online on July 3 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Differences in prostate cancer testing and treatment may account for some of the observed association between a healthy lifestyle and prostate cancer death. This analysis provides an estimate of what is achievable in terms of prevention had everyone adopted a healthy lifestyle. The authors only considered factors at study entry, which would not include changes that happen later.

DISCLOSURES:

The study authors reported several disclosures. Fredrik Wiklund, PhD, received grants from GE Healthcare, personal fees from Janssen, Varian Medical Systems, and WebMD, and stock options and personal fees from Cortechs Labs outside the submitted work. Adam S. Kibel, MD, received personal fees from Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellvax, Merck, and Roche and served as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb and Candel outside the submitted work. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- About one third of men die from prostate cancer before age 75, highlighting the need for prevention strategies that target high-risk populations.

- In the current study, researchers analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies — the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study (MDCS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) — which included 19,607 men with a median age at inclusion of 59 years (MDCS) and 65.1 years (HPFS) followed from 1991 to 2019.

- Participants were categorized by genetic risk and lifestyle score. Genetic risk was defined using a multiancestry polygenic risk score (PRS) for overall prostate cancer that included 400 genetic risk variants.

- A healthy lifestyle score was defined as 3-6, while an unhealthy lifestyle score was 0-2. Lifestyle factors included smoking, weight, physical activity, and diet.

- The researchers calculated hazard ratios (HRs) for the association between genetic and lifestyle factors and prostate cancer death.

TAKEAWAY:

- Combining the PRS and family history of cancer, 67% of men overall (13,186 of 19,607) were considered to have higher genetic risk, and about 30% overall had an unhealthy lifestyle score of 0-2.

- Men at higher genetic risk accounted for 88% (94 of 107) of early prostate cancer deaths.

- Compared with men at lower genetic risk, those at higher genetic risk had more than a threefold higher rate of early prostate cancer death (HR, 3.26) and more than a twofold increased rate of late prostate cancer death (HR, 2.26) as well as a higher lifetime risk for prostate cancer death.

- Among men at higher genetic risk, an unhealthy lifestyle was associated with a higher risk of early prostate cancer death, with smoking and a BMI of ≥ 30 being significant factors. Depending on the definition of a healthy lifestyle, the researchers estimated that 22%-36% of early prostate cancer deaths among men at higher genetic risk might be preventable.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on data from two prospective cohort studies, this analysis provides evidence for targeting men at increased genetic risk with prevention strategies aimed at reducing premature deaths from prostate cancer,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Anna Plym, PhD, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, was published online on July 3 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Differences in prostate cancer testing and treatment may account for some of the observed association between a healthy lifestyle and prostate cancer death. This analysis provides an estimate of what is achievable in terms of prevention had everyone adopted a healthy lifestyle. The authors only considered factors at study entry, which would not include changes that happen later.

DISCLOSURES:

The study authors reported several disclosures. Fredrik Wiklund, PhD, received grants from GE Healthcare, personal fees from Janssen, Varian Medical Systems, and WebMD, and stock options and personal fees from Cortechs Labs outside the submitted work. Adam S. Kibel, MD, received personal fees from Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellvax, Merck, and Roche and served as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb and Candel outside the submitted work. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- About one third of men die from prostate cancer before age 75, highlighting the need for prevention strategies that target high-risk populations.

- In the current study, researchers analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies — the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study (MDCS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) — which included 19,607 men with a median age at inclusion of 59 years (MDCS) and 65.1 years (HPFS) followed from 1991 to 2019.

- Participants were categorized by genetic risk and lifestyle score. Genetic risk was defined using a multiancestry polygenic risk score (PRS) for overall prostate cancer that included 400 genetic risk variants.

- A healthy lifestyle score was defined as 3-6, while an unhealthy lifestyle score was 0-2. Lifestyle factors included smoking, weight, physical activity, and diet.

- The researchers calculated hazard ratios (HRs) for the association between genetic and lifestyle factors and prostate cancer death.

TAKEAWAY:

- Combining the PRS and family history of cancer, 67% of men overall (13,186 of 19,607) were considered to have higher genetic risk, and about 30% overall had an unhealthy lifestyle score of 0-2.

- Men at higher genetic risk accounted for 88% (94 of 107) of early prostate cancer deaths.

- Compared with men at lower genetic risk, those at higher genetic risk had more than a threefold higher rate of early prostate cancer death (HR, 3.26) and more than a twofold increased rate of late prostate cancer death (HR, 2.26) as well as a higher lifetime risk for prostate cancer death.

- Among men at higher genetic risk, an unhealthy lifestyle was associated with a higher risk of early prostate cancer death, with smoking and a BMI of ≥ 30 being significant factors. Depending on the definition of a healthy lifestyle, the researchers estimated that 22%-36% of early prostate cancer deaths among men at higher genetic risk might be preventable.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on data from two prospective cohort studies, this analysis provides evidence for targeting men at increased genetic risk with prevention strategies aimed at reducing premature deaths from prostate cancer,” the researchers concluded.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Anna Plym, PhD, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, was published online on July 3 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Differences in prostate cancer testing and treatment may account for some of the observed association between a healthy lifestyle and prostate cancer death. This analysis provides an estimate of what is achievable in terms of prevention had everyone adopted a healthy lifestyle. The authors only considered factors at study entry, which would not include changes that happen later.

DISCLOSURES:

The study authors reported several disclosures. Fredrik Wiklund, PhD, received grants from GE Healthcare, personal fees from Janssen, Varian Medical Systems, and WebMD, and stock options and personal fees from Cortechs Labs outside the submitted work. Adam S. Kibel, MD, received personal fees from Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellvax, Merck, and Roche and served as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb and Candel outside the submitted work. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ASCO 2024: An Expert’s Top Hematology Highlights

Research presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has the potential to change practice — and assumptions — about acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and blood cancer as a whole, according to the chief science officer of the American Cancer Society.

In an interview following the conference, Arif H. Kamal, MD, MBA, MHS, who practices hematology-oncology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, recapped several landmark studies and discussed their lessons for clinicians.

Question: You’ve highlighted a randomized, multisite clinical trialled by a researcher from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The researchers enrolled 115 adult patients with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) who were receiving non–intensive care to usual care or regular meetings with palliative care clinicians (monthly as outpatients and at least twice weekly as inpatients). Among those who died (61.7%), those in the intervention group had their end-of-life preferences documented much earlier (41 days before death vs. 1.5 days, P < .001). They were also more likely to have documented end-of-life care preferences (96.5% vs. 68.4%, P < .001) and less likely to have been hospitalized within the last month of life (70.6% vs. 91.9%, P = .031). Why did this study strike you as especially important?

Dr. Kamal: A few studies have now shown better outcomes in hematology after the use of early palliative care. This has been shown not only in transplant patients but also in non-transplant patients with hematologic malignancies. As a result, you’re seeing a shift toward regular integration of palliative care.

The historical concern has been that palliative care takes the foot off the gas pedal. Another way to look at it is that palliative care helps keep the foot on the gas pedal.

Q: Should the focus be on all hematologic cancer patients or just on those who are more severe cases or whose illness is terminal?

Dr. Kamal: The focus is on patients with acute progressive leukemias rather than those with indolent, long-standing lymphomas. This a reflection of severity and complexity: In leukemia, you can be someone really sick all of a sudden and require intensive treatment.

Q: What’s new about this kind of research?

Dr. Kamal: We’re learning how palliative care is valuable in all cancers, but particularly in blood cancers, where it has historically not been studied. The groundbreaking studies in palliative care over the last 20 years have largely been in solid tumors such as lung cancers and colorectal cancers.

Q: What is unique about the patient experience in hematologic cancers compared to solid tumor cancers?

Dr. Kamal: Blood cancers are a relatively new place to integrate palliative care, but what we’re finding is that it may be even more needed than in solid tumors in terms of improving outcomes.

In pancreatic cancer, you may not know if something is going to work, but it is going to take you months to figure it out. In leukemia, there can be a lot of dynamism: You’re going to find out in a matter of days. You have to be able to pivot really quickly to the next thing, go to transplant very quickly and urgently, or make a decision to pursue supportive care.

This really compresses the normal issues like uncertainty and emotional anxiety that a pancreatic cancer patient may process over a year. Leukemic patients may need to process that over 2, 3, or 4 weeks. Palliative care can be there to help the patient to process options.

Q: You also highlighted the industry-funded phase 3 ASC4FIRST study into asciminib (Scemblix) in newly diagnosed patients with CML. The trial was led by a researcher from the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute and the University of Adelaide, Australia. Asciminib, a STAMP inhibitor, is FDA-approved for certain CML indications. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the new study finds better major molecular response at 48 weeks for the drug vs. investigator-selected tyrosine kinase inhibitors (67.7% vs. 49.0%, P < .001). What do these findings tell you?