User login

A pediatrician’s guide to screening for and treating depression

On Oct. 19, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association jointly declared a “national emergency in children’s mental health,” calling upon policy makers to take actions that could help address “soaring rates” of anxiety and depression.

Knowing that increasing the work force or creating new programs will come slowly if at all, they called for the integration of mental health care into primary care pediatrics and efforts to reduce the risk of suicide in children and adolescents.

Our clinical experience suggests that adolescent depression, which can lead to profoundly impaired function, impaired development, and even suicide, is a major concern in your practice. We hope to do our part by reviewing the screening, diagnosis, and management of depression that can reasonably happen in the pediatrician’s office.

Depression

Depression affects as many as 20% of adolescents, with girls experiencing major depressive disorder (MDD) twice as often as boys. The incidence of depression increases fourfold after puberty, and there is substantial evidence, but no clear cause, that it has increased by nearly 50% over the past decade, rising from a rate of 8% of U.S. adolescents in 2007 to 13% in 2017.1 In that same time period, the rate of completed suicides among U.S. youth aged 10-24 increased 57.4%, after being stable for the prior decade.2 Adolescent depression is also linked to increased substance use and high-risk behaviors such as drunk driving. In 2020, mental health–related emergency department visits by adolescents aged 12-17 increased by 31%. Visits for suicide attempts among adolescent girls in 2021 jumped by 51% from 2019.3 Clearly, MDD in adolescence is a common, potentially life-threatening problem

.

Screening and assessment

At annual checkups with patients 12 and older or at sick visits of patients with emotional, sleep, or vague somatic concerns, it should be standard practice to screen for depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 modified for Adolescents (PHQ9-A) is a reliable, validated, and free screening instrument that your patients can fill out in the waiting room. (The PHQ9 can be used for your patients who are 18 and older.) It takes only 5 minutes to complete and is very easy to score. It establishes whether your patient meets DSM-5 criteria for MDD, and the degree of severity (5-9 is mild, 10-14 is moderate, 15-19 is moderately severe, and 20-27 is severe). It also screens for thoughts about suicide and past suicide attempts. You might add the more comprehensive parent-completed Pediatric Symptom Checklist, which includes a depression screen.4

These screening instruments can be completed electronically prior to or at the visit and should have a preamble explaining why depression screening is relevant. If screening is positive, interview your adolescent patients alone. This will give you the time to gather more detail about how impaired their function is at school, with friends, and in family relationships. Have they been missing school? Have their grades changed? Are they failing to hand in homework? Have they withdrawn from sports or activities? Are they less likely to hang out with friends? Do they participate in family activities? Have others noticed any changes? You should also check for associated anxiety symptoms (ruminative worries, panic attacks) and drug and alcohol use. Of course, you should ask about any suicidal thoughts (from vague morbid thoughts to specific plans, with intent and factors that have prevented them) and actual attempts. Remember, asking about suicidal thoughts and attempts will not cause or worsen them. On the contrary, your patients may feel shame, but will be relieved to not be alone with these thoughts. And this knowledge will be essential as you decide what to do next. When you meet with the parents, ask them about a family history of depression or suicide attempts, and then offer supportive interventions.

Supportive interventions

For all adolescents with depression, supportive interventions are helpful, and for those with mild symptoms, they are often adequate treatment. This begins with education for your patient and their parents about depression. It is an illness, not a problem of character or discipline. Advise your patients that adequate, restful sleep every night is critical to recovery. Regular exercise (daily is best, but at least three times weekly for 30 minutes) is often effective in mild to moderate depression. Patience and compassion for feelings of sadness, irritability, or disinterest are important at home, and maintaining connections with those people who offer support (friends, coaches, parents, etc.) is essential. They should also be told that “depression lies.” Feelings of guilt and self-reproach are a normal part of the illness, not facts. Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) offer written materials through their websites that are very helpful educational resources. Connect them with sources of counseling support (through school, for example). For those with mild, brief, and uncomplicated depression, supportive interventions alone should offer relief within 4-6 weeks. It is hard to predict the trajectory of depression, so follow-up visits are relevant to determine if they are improving or worsening.

Psychotherapy

For your patients with moderate depression, or with hopelessness or suicidality, a referral for evidence-based psychotherapy is indicated. Both cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy have demonstrated efficacy in treating depression in adolescents. If there is a history of trauma or high family conflict, supportive psychotherapy that will enhance communication skills within the family is very important to recovery. Identify various sources for high-quality psychotherapy services (individual, family, and group) in your community. While this may sound easier said than done, online services such as Psychology Today’s therapist locator can help. If your local university has a graduate program in social work or psychology, connect with them as they may have easier access to high-quality services through their training programs. If there is a group practice of therapists in your community, invite them to meet with your team to learn about whether they use evidence-based therapies and can support families as well as individual youth.

Pharmacologic options

For those adolescents with moderate to severe depression, psychotherapy alone is usually inadequate. Indeed, they may be so impaired that they simply cannot meaningfully engage in the work of psychotherapy. These patients require psychopharmacologic treatment first. First-line treatment is with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (both fluoxetine and escitalopram are approved for use in adolescent depression). While many pediatricians remain reluctant about initiating SSRI treatment of depression since the Food and Drug Administration’s 2004 boxed warning was issued, the risks of untreated severe depression are more marked than are the risks of SSRI treatment. As prescription rates dipped in the following decade, rates of suicide attempts in adolescents with severe depression climbed. Subsequent research on the nature of the risk of “increased suicidality” indicated it is substantially lower than originally thought.

The AAP’s Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care offer reassuring guidance: They recommend that pediatricians initiate treatment at a very low dose of SSRI (5 mg of fluoxetine, 12.5 mg of sertraline, or 5 mg of escitalopram) and aim to get to a therapeutic dose within 4 weeks.5 Educate the patient and parent about likely side effects (gastrointestinal upset, sleep disruption, akathisia or restlessness, and activation), which indicate the dose should be held steady until the side effects subside. Patients should be seen weekly until they get to a therapeutic dose, then biweekly to monitor for response. At these regular check-ins, the PHQ9A can follow symptom severity. You should monitor changes in function and for any change in suicidal thoughts. If your patient does not respond with at least energy improvement within 4 weeks, you should cross-taper to a different SSRI.

Managing risk

Suicidal thoughts are a common symptom of depression and an important marker of severity. Adolescents have more limited impulse control than do adults, elevating their risk for impulsively acting on these thoughts. Adolescents who are using alcohol or other substances, or who have a history of impulsivity, are at higher risk. Further compounding the degree of risk are a history of suicide attempts, impulsive aggression or psychotic symptoms, or a family history of completed suicide. In managing risk, it is critical that you assess and discuss these risk factors and discuss the need to have a safety plan.

This planning should include both patient and parent. Help the parent to identify lethal means at home (guns, rope, medications, and knives or box cutters) and make plans to secure or remove them. It includes helping your patient list those strategies that can be helpful if they are feeling more distressed (distracting with music or television, exercise, or connecting with select friends). A safety plan is not a promise or a contract to not do something, rather it is a practical set of strategies the patient and family can employ if they are feeling worse. It depends on the adolescent having a secure, trusting connection with the adults at home and with your office.

If your patient fails to improve, if the diagnosis appears complicated, or if you feel the patient is not safe, you should refer to child psychiatry or, if needed, a local emergency department. If you cannot find access to a psychiatrist, start with your state’s child psychiatric consultation hotline for access to telephone support: www.nncpap.org.

Although the suggestions outlined above are grounded in evidence and need, treating moderate to severe depression is likely a new challenge for many pediatricians. Managing the risk of suicide can be stressful, without a doubt. In our own work as child psychiatrists, we recognize that there is no single, reliable method to predict suicide and therefore no specific approach to ensuring prevention. We appreciate this burden of worry when treating a severely depressed adolescent, and follow the rule, “never worry alone” – share your concerns with parents and/or a mental health consultant (hopefully co-located in your office), or obtain a second opinion, even consult a child psychiatrist on a hotline. Offering supportive care for those with mild depression can prevent it from becoming severe, and beginning treatment for those with severe depression can make a profound difference in the course of a young person’s illness.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pew Research Center. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2017).

2. Curtin SC. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020 Sep;69(11):1-10.

3. Yard E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Jun 18;70(24):888-94.

4. Jellinek M et al. J Pediatr. 2021 Jun;233:220-6.e1.

5. Zuckerbrot RA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar;141(3):e20174081.

On Oct. 19, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association jointly declared a “national emergency in children’s mental health,” calling upon policy makers to take actions that could help address “soaring rates” of anxiety and depression.

Knowing that increasing the work force or creating new programs will come slowly if at all, they called for the integration of mental health care into primary care pediatrics and efforts to reduce the risk of suicide in children and adolescents.

Our clinical experience suggests that adolescent depression, which can lead to profoundly impaired function, impaired development, and even suicide, is a major concern in your practice. We hope to do our part by reviewing the screening, diagnosis, and management of depression that can reasonably happen in the pediatrician’s office.

Depression

Depression affects as many as 20% of adolescents, with girls experiencing major depressive disorder (MDD) twice as often as boys. The incidence of depression increases fourfold after puberty, and there is substantial evidence, but no clear cause, that it has increased by nearly 50% over the past decade, rising from a rate of 8% of U.S. adolescents in 2007 to 13% in 2017.1 In that same time period, the rate of completed suicides among U.S. youth aged 10-24 increased 57.4%, after being stable for the prior decade.2 Adolescent depression is also linked to increased substance use and high-risk behaviors such as drunk driving. In 2020, mental health–related emergency department visits by adolescents aged 12-17 increased by 31%. Visits for suicide attempts among adolescent girls in 2021 jumped by 51% from 2019.3 Clearly, MDD in adolescence is a common, potentially life-threatening problem

.

Screening and assessment

At annual checkups with patients 12 and older or at sick visits of patients with emotional, sleep, or vague somatic concerns, it should be standard practice to screen for depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 modified for Adolescents (PHQ9-A) is a reliable, validated, and free screening instrument that your patients can fill out in the waiting room. (The PHQ9 can be used for your patients who are 18 and older.) It takes only 5 minutes to complete and is very easy to score. It establishes whether your patient meets DSM-5 criteria for MDD, and the degree of severity (5-9 is mild, 10-14 is moderate, 15-19 is moderately severe, and 20-27 is severe). It also screens for thoughts about suicide and past suicide attempts. You might add the more comprehensive parent-completed Pediatric Symptom Checklist, which includes a depression screen.4

These screening instruments can be completed electronically prior to or at the visit and should have a preamble explaining why depression screening is relevant. If screening is positive, interview your adolescent patients alone. This will give you the time to gather more detail about how impaired their function is at school, with friends, and in family relationships. Have they been missing school? Have their grades changed? Are they failing to hand in homework? Have they withdrawn from sports or activities? Are they less likely to hang out with friends? Do they participate in family activities? Have others noticed any changes? You should also check for associated anxiety symptoms (ruminative worries, panic attacks) and drug and alcohol use. Of course, you should ask about any suicidal thoughts (from vague morbid thoughts to specific plans, with intent and factors that have prevented them) and actual attempts. Remember, asking about suicidal thoughts and attempts will not cause or worsen them. On the contrary, your patients may feel shame, but will be relieved to not be alone with these thoughts. And this knowledge will be essential as you decide what to do next. When you meet with the parents, ask them about a family history of depression or suicide attempts, and then offer supportive interventions.

Supportive interventions

For all adolescents with depression, supportive interventions are helpful, and for those with mild symptoms, they are often adequate treatment. This begins with education for your patient and their parents about depression. It is an illness, not a problem of character or discipline. Advise your patients that adequate, restful sleep every night is critical to recovery. Regular exercise (daily is best, but at least three times weekly for 30 minutes) is often effective in mild to moderate depression. Patience and compassion for feelings of sadness, irritability, or disinterest are important at home, and maintaining connections with those people who offer support (friends, coaches, parents, etc.) is essential. They should also be told that “depression lies.” Feelings of guilt and self-reproach are a normal part of the illness, not facts. Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) offer written materials through their websites that are very helpful educational resources. Connect them with sources of counseling support (through school, for example). For those with mild, brief, and uncomplicated depression, supportive interventions alone should offer relief within 4-6 weeks. It is hard to predict the trajectory of depression, so follow-up visits are relevant to determine if they are improving or worsening.

Psychotherapy

For your patients with moderate depression, or with hopelessness or suicidality, a referral for evidence-based psychotherapy is indicated. Both cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy have demonstrated efficacy in treating depression in adolescents. If there is a history of trauma or high family conflict, supportive psychotherapy that will enhance communication skills within the family is very important to recovery. Identify various sources for high-quality psychotherapy services (individual, family, and group) in your community. While this may sound easier said than done, online services such as Psychology Today’s therapist locator can help. If your local university has a graduate program in social work or psychology, connect with them as they may have easier access to high-quality services through their training programs. If there is a group practice of therapists in your community, invite them to meet with your team to learn about whether they use evidence-based therapies and can support families as well as individual youth.

Pharmacologic options

For those adolescents with moderate to severe depression, psychotherapy alone is usually inadequate. Indeed, they may be so impaired that they simply cannot meaningfully engage in the work of psychotherapy. These patients require psychopharmacologic treatment first. First-line treatment is with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (both fluoxetine and escitalopram are approved for use in adolescent depression). While many pediatricians remain reluctant about initiating SSRI treatment of depression since the Food and Drug Administration’s 2004 boxed warning was issued, the risks of untreated severe depression are more marked than are the risks of SSRI treatment. As prescription rates dipped in the following decade, rates of suicide attempts in adolescents with severe depression climbed. Subsequent research on the nature of the risk of “increased suicidality” indicated it is substantially lower than originally thought.

The AAP’s Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care offer reassuring guidance: They recommend that pediatricians initiate treatment at a very low dose of SSRI (5 mg of fluoxetine, 12.5 mg of sertraline, or 5 mg of escitalopram) and aim to get to a therapeutic dose within 4 weeks.5 Educate the patient and parent about likely side effects (gastrointestinal upset, sleep disruption, akathisia or restlessness, and activation), which indicate the dose should be held steady until the side effects subside. Patients should be seen weekly until they get to a therapeutic dose, then biweekly to monitor for response. At these regular check-ins, the PHQ9A can follow symptom severity. You should monitor changes in function and for any change in suicidal thoughts. If your patient does not respond with at least energy improvement within 4 weeks, you should cross-taper to a different SSRI.

Managing risk

Suicidal thoughts are a common symptom of depression and an important marker of severity. Adolescents have more limited impulse control than do adults, elevating their risk for impulsively acting on these thoughts. Adolescents who are using alcohol or other substances, or who have a history of impulsivity, are at higher risk. Further compounding the degree of risk are a history of suicide attempts, impulsive aggression or psychotic symptoms, or a family history of completed suicide. In managing risk, it is critical that you assess and discuss these risk factors and discuss the need to have a safety plan.

This planning should include both patient and parent. Help the parent to identify lethal means at home (guns, rope, medications, and knives or box cutters) and make plans to secure or remove them. It includes helping your patient list those strategies that can be helpful if they are feeling more distressed (distracting with music or television, exercise, or connecting with select friends). A safety plan is not a promise or a contract to not do something, rather it is a practical set of strategies the patient and family can employ if they are feeling worse. It depends on the adolescent having a secure, trusting connection with the adults at home and with your office.

If your patient fails to improve, if the diagnosis appears complicated, or if you feel the patient is not safe, you should refer to child psychiatry or, if needed, a local emergency department. If you cannot find access to a psychiatrist, start with your state’s child psychiatric consultation hotline for access to telephone support: www.nncpap.org.

Although the suggestions outlined above are grounded in evidence and need, treating moderate to severe depression is likely a new challenge for many pediatricians. Managing the risk of suicide can be stressful, without a doubt. In our own work as child psychiatrists, we recognize that there is no single, reliable method to predict suicide and therefore no specific approach to ensuring prevention. We appreciate this burden of worry when treating a severely depressed adolescent, and follow the rule, “never worry alone” – share your concerns with parents and/or a mental health consultant (hopefully co-located in your office), or obtain a second opinion, even consult a child psychiatrist on a hotline. Offering supportive care for those with mild depression can prevent it from becoming severe, and beginning treatment for those with severe depression can make a profound difference in the course of a young person’s illness.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pew Research Center. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2017).

2. Curtin SC. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020 Sep;69(11):1-10.

3. Yard E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Jun 18;70(24):888-94.

4. Jellinek M et al. J Pediatr. 2021 Jun;233:220-6.e1.

5. Zuckerbrot RA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar;141(3):e20174081.

On Oct. 19, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association jointly declared a “national emergency in children’s mental health,” calling upon policy makers to take actions that could help address “soaring rates” of anxiety and depression.

Knowing that increasing the work force or creating new programs will come slowly if at all, they called for the integration of mental health care into primary care pediatrics and efforts to reduce the risk of suicide in children and adolescents.

Our clinical experience suggests that adolescent depression, which can lead to profoundly impaired function, impaired development, and even suicide, is a major concern in your practice. We hope to do our part by reviewing the screening, diagnosis, and management of depression that can reasonably happen in the pediatrician’s office.

Depression

Depression affects as many as 20% of adolescents, with girls experiencing major depressive disorder (MDD) twice as often as boys. The incidence of depression increases fourfold after puberty, and there is substantial evidence, but no clear cause, that it has increased by nearly 50% over the past decade, rising from a rate of 8% of U.S. adolescents in 2007 to 13% in 2017.1 In that same time period, the rate of completed suicides among U.S. youth aged 10-24 increased 57.4%, after being stable for the prior decade.2 Adolescent depression is also linked to increased substance use and high-risk behaviors such as drunk driving. In 2020, mental health–related emergency department visits by adolescents aged 12-17 increased by 31%. Visits for suicide attempts among adolescent girls in 2021 jumped by 51% from 2019.3 Clearly, MDD in adolescence is a common, potentially life-threatening problem

.

Screening and assessment

At annual checkups with patients 12 and older or at sick visits of patients with emotional, sleep, or vague somatic concerns, it should be standard practice to screen for depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 modified for Adolescents (PHQ9-A) is a reliable, validated, and free screening instrument that your patients can fill out in the waiting room. (The PHQ9 can be used for your patients who are 18 and older.) It takes only 5 minutes to complete and is very easy to score. It establishes whether your patient meets DSM-5 criteria for MDD, and the degree of severity (5-9 is mild, 10-14 is moderate, 15-19 is moderately severe, and 20-27 is severe). It also screens for thoughts about suicide and past suicide attempts. You might add the more comprehensive parent-completed Pediatric Symptom Checklist, which includes a depression screen.4

These screening instruments can be completed electronically prior to or at the visit and should have a preamble explaining why depression screening is relevant. If screening is positive, interview your adolescent patients alone. This will give you the time to gather more detail about how impaired their function is at school, with friends, and in family relationships. Have they been missing school? Have their grades changed? Are they failing to hand in homework? Have they withdrawn from sports or activities? Are they less likely to hang out with friends? Do they participate in family activities? Have others noticed any changes? You should also check for associated anxiety symptoms (ruminative worries, panic attacks) and drug and alcohol use. Of course, you should ask about any suicidal thoughts (from vague morbid thoughts to specific plans, with intent and factors that have prevented them) and actual attempts. Remember, asking about suicidal thoughts and attempts will not cause or worsen them. On the contrary, your patients may feel shame, but will be relieved to not be alone with these thoughts. And this knowledge will be essential as you decide what to do next. When you meet with the parents, ask them about a family history of depression or suicide attempts, and then offer supportive interventions.

Supportive interventions

For all adolescents with depression, supportive interventions are helpful, and for those with mild symptoms, they are often adequate treatment. This begins with education for your patient and their parents about depression. It is an illness, not a problem of character or discipline. Advise your patients that adequate, restful sleep every night is critical to recovery. Regular exercise (daily is best, but at least three times weekly for 30 minutes) is often effective in mild to moderate depression. Patience and compassion for feelings of sadness, irritability, or disinterest are important at home, and maintaining connections with those people who offer support (friends, coaches, parents, etc.) is essential. They should also be told that “depression lies.” Feelings of guilt and self-reproach are a normal part of the illness, not facts. Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) offer written materials through their websites that are very helpful educational resources. Connect them with sources of counseling support (through school, for example). For those with mild, brief, and uncomplicated depression, supportive interventions alone should offer relief within 4-6 weeks. It is hard to predict the trajectory of depression, so follow-up visits are relevant to determine if they are improving or worsening.

Psychotherapy

For your patients with moderate depression, or with hopelessness or suicidality, a referral for evidence-based psychotherapy is indicated. Both cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy have demonstrated efficacy in treating depression in adolescents. If there is a history of trauma or high family conflict, supportive psychotherapy that will enhance communication skills within the family is very important to recovery. Identify various sources for high-quality psychotherapy services (individual, family, and group) in your community. While this may sound easier said than done, online services such as Psychology Today’s therapist locator can help. If your local university has a graduate program in social work or psychology, connect with them as they may have easier access to high-quality services through their training programs. If there is a group practice of therapists in your community, invite them to meet with your team to learn about whether they use evidence-based therapies and can support families as well as individual youth.

Pharmacologic options

For those adolescents with moderate to severe depression, psychotherapy alone is usually inadequate. Indeed, they may be so impaired that they simply cannot meaningfully engage in the work of psychotherapy. These patients require psychopharmacologic treatment first. First-line treatment is with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (both fluoxetine and escitalopram are approved for use in adolescent depression). While many pediatricians remain reluctant about initiating SSRI treatment of depression since the Food and Drug Administration’s 2004 boxed warning was issued, the risks of untreated severe depression are more marked than are the risks of SSRI treatment. As prescription rates dipped in the following decade, rates of suicide attempts in adolescents with severe depression climbed. Subsequent research on the nature of the risk of “increased suicidality” indicated it is substantially lower than originally thought.

The AAP’s Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care offer reassuring guidance: They recommend that pediatricians initiate treatment at a very low dose of SSRI (5 mg of fluoxetine, 12.5 mg of sertraline, or 5 mg of escitalopram) and aim to get to a therapeutic dose within 4 weeks.5 Educate the patient and parent about likely side effects (gastrointestinal upset, sleep disruption, akathisia or restlessness, and activation), which indicate the dose should be held steady until the side effects subside. Patients should be seen weekly until they get to a therapeutic dose, then biweekly to monitor for response. At these regular check-ins, the PHQ9A can follow symptom severity. You should monitor changes in function and for any change in suicidal thoughts. If your patient does not respond with at least energy improvement within 4 weeks, you should cross-taper to a different SSRI.

Managing risk

Suicidal thoughts are a common symptom of depression and an important marker of severity. Adolescents have more limited impulse control than do adults, elevating their risk for impulsively acting on these thoughts. Adolescents who are using alcohol or other substances, or who have a history of impulsivity, are at higher risk. Further compounding the degree of risk are a history of suicide attempts, impulsive aggression or psychotic symptoms, or a family history of completed suicide. In managing risk, it is critical that you assess and discuss these risk factors and discuss the need to have a safety plan.

This planning should include both patient and parent. Help the parent to identify lethal means at home (guns, rope, medications, and knives or box cutters) and make plans to secure or remove them. It includes helping your patient list those strategies that can be helpful if they are feeling more distressed (distracting with music or television, exercise, or connecting with select friends). A safety plan is not a promise or a contract to not do something, rather it is a practical set of strategies the patient and family can employ if they are feeling worse. It depends on the adolescent having a secure, trusting connection with the adults at home and with your office.

If your patient fails to improve, if the diagnosis appears complicated, or if you feel the patient is not safe, you should refer to child psychiatry or, if needed, a local emergency department. If you cannot find access to a psychiatrist, start with your state’s child psychiatric consultation hotline for access to telephone support: www.nncpap.org.

Although the suggestions outlined above are grounded in evidence and need, treating moderate to severe depression is likely a new challenge for many pediatricians. Managing the risk of suicide can be stressful, without a doubt. In our own work as child psychiatrists, we recognize that there is no single, reliable method to predict suicide and therefore no specific approach to ensuring prevention. We appreciate this burden of worry when treating a severely depressed adolescent, and follow the rule, “never worry alone” – share your concerns with parents and/or a mental health consultant (hopefully co-located in your office), or obtain a second opinion, even consult a child psychiatrist on a hotline. Offering supportive care for those with mild depression can prevent it from becoming severe, and beginning treatment for those with severe depression can make a profound difference in the course of a young person’s illness.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pew Research Center. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2017).

2. Curtin SC. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020 Sep;69(11):1-10.

3. Yard E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Jun 18;70(24):888-94.

4. Jellinek M et al. J Pediatr. 2021 Jun;233:220-6.e1.

5. Zuckerbrot RA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar;141(3):e20174081.

Aaron Beck: An appreciation

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Twice exceptionality: A hidden diagnosis in primary care

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

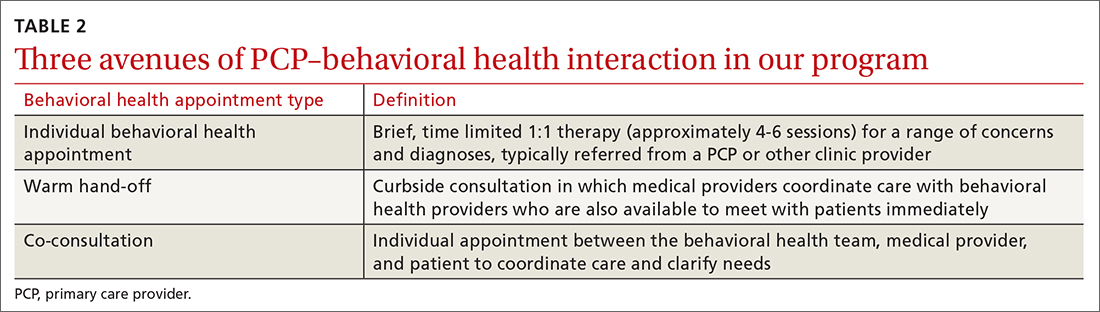

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.