User login

Woman with throbbing unilateral headache

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

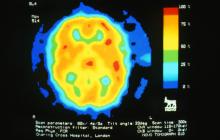

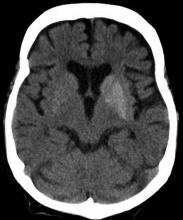

A 28-year-old woman presents with a throbbing unilateral headache (left side) and is very nauseated. She describes a white light in her line of vision. Her headaches are recurring, pulsating, and usually last for about 2 days without relief from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). She has been experiencing these episodes almost every month for the past 8 months and initially attributed them to her menstrual cycle, as she has always experienced moderate to severe headaches during this time. The patient is enrolled in a research trial in which single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging revealed low activity with reduced blood flow. The patient is nonfebrile.

Shortness of breath and abdominal pain

On the basis of the patient's history and clinical presentation, the likely diagnosis is ketosis-prone diabetes (KPD) type 2. KPD is widely thought of as an atypical diabetes syndrome, though some groups consider it to be a common clinical presentation in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) rather than a subtype of disease. The condition is more prevalent in males and among Black and Hispanic populations.

Definitive diagnosis of the type of diabetes can present a clinical challenge during acute presentation. Although the majority of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episodes occur in patients previously diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, an estimated 34% occur in patients with T2D. For patients who are obese or have a family history of diabetes, there should be a high index of suspicion for new-onset DKA in type 2 diabetes.

Patients with KPD typically present in a state of ketoacidosis with a brief but acute history of hyperglycemic symptoms. Hyperglycemia, elevated anion gap acidosis, and ketonemia form the expected constellation of DKA symptoms. A key consideration in the differential diagnosis is hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). Patients with HHS are much more likely to have altered mental status than are patients with DKA. Metabolic acidosis and ketonemia are absent or mild, and anion gap is either normal or slightly elevated. In HHS, extreme elevations of glucose are seen, with a lack of significant ketoacidosis. Glucose levels tend to be higher in HHS than in DKA; they are almost always > 600 mg/dL, and levels > 1000 mg/dL are not uncommon. In DKA, glucose levels are still markedly high — generally 500-800 mg/dL but rarely exceeding 900 mg/dL. Patients with DKA also usually present with an A1c > 10% and a blood pH < 7.30.

Treatment for KPD is initially acute, beginning with aggressive intravenous fluid and insulin therapy A. Once this state resolves, insulin requirements typically decrease for patients with T2D, and they are able to maintain adequate glycemic control with an oral therapy regimen.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's history and clinical presentation, the likely diagnosis is ketosis-prone diabetes (KPD) type 2. KPD is widely thought of as an atypical diabetes syndrome, though some groups consider it to be a common clinical presentation in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) rather than a subtype of disease. The condition is more prevalent in males and among Black and Hispanic populations.

Definitive diagnosis of the type of diabetes can present a clinical challenge during acute presentation. Although the majority of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episodes occur in patients previously diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, an estimated 34% occur in patients with T2D. For patients who are obese or have a family history of diabetes, there should be a high index of suspicion for new-onset DKA in type 2 diabetes.

Patients with KPD typically present in a state of ketoacidosis with a brief but acute history of hyperglycemic symptoms. Hyperglycemia, elevated anion gap acidosis, and ketonemia form the expected constellation of DKA symptoms. A key consideration in the differential diagnosis is hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). Patients with HHS are much more likely to have altered mental status than are patients with DKA. Metabolic acidosis and ketonemia are absent or mild, and anion gap is either normal or slightly elevated. In HHS, extreme elevations of glucose are seen, with a lack of significant ketoacidosis. Glucose levels tend to be higher in HHS than in DKA; they are almost always > 600 mg/dL, and levels > 1000 mg/dL are not uncommon. In DKA, glucose levels are still markedly high — generally 500-800 mg/dL but rarely exceeding 900 mg/dL. Patients with DKA also usually present with an A1c > 10% and a blood pH < 7.30.

Treatment for KPD is initially acute, beginning with aggressive intravenous fluid and insulin therapy A. Once this state resolves, insulin requirements typically decrease for patients with T2D, and they are able to maintain adequate glycemic control with an oral therapy regimen.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's history and clinical presentation, the likely diagnosis is ketosis-prone diabetes (KPD) type 2. KPD is widely thought of as an atypical diabetes syndrome, though some groups consider it to be a common clinical presentation in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) rather than a subtype of disease. The condition is more prevalent in males and among Black and Hispanic populations.

Definitive diagnosis of the type of diabetes can present a clinical challenge during acute presentation. Although the majority of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episodes occur in patients previously diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, an estimated 34% occur in patients with T2D. For patients who are obese or have a family history of diabetes, there should be a high index of suspicion for new-onset DKA in type 2 diabetes.

Patients with KPD typically present in a state of ketoacidosis with a brief but acute history of hyperglycemic symptoms. Hyperglycemia, elevated anion gap acidosis, and ketonemia form the expected constellation of DKA symptoms. A key consideration in the differential diagnosis is hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). Patients with HHS are much more likely to have altered mental status than are patients with DKA. Metabolic acidosis and ketonemia are absent or mild, and anion gap is either normal or slightly elevated. In HHS, extreme elevations of glucose are seen, with a lack of significant ketoacidosis. Glucose levels tend to be higher in HHS than in DKA; they are almost always > 600 mg/dL, and levels > 1000 mg/dL are not uncommon. In DKA, glucose levels are still markedly high — generally 500-800 mg/dL but rarely exceeding 900 mg/dL. Patients with DKA also usually present with an A1c > 10% and a blood pH < 7.30.

Treatment for KPD is initially acute, beginning with aggressive intravenous fluid and insulin therapy A. Once this state resolves, insulin requirements typically decrease for patients with T2D, and they are able to maintain adequate glycemic control with an oral therapy regimen.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 21-year-old man presents with shortness of breath and abdominal pain. He has a BMI of 34.6 and explains that he has had asthma for several years, using an inhaler when needed. He reports a few weeks of polydipsia and polyuria. The patient notes that his father has kidney disease. He believes other close relatives are managing chronic metabolic conditions but does not know any further detail regarding their diagnoses. On laboratory testing, blood pH is 6.30 and bicarbonate level is 11.1 mmol/L. A1c is 12.0%. Acanthosis nigricans are noted on the neck and in the axilla bilaterally.

Severe pain in the frontotemporal area

Migraine is a neurologic disease characterized by episodes of throbbing, often unilateral, headache. These attacks are associated with visual or other sensory symptoms (classic aura) related to the central nervous system, nausea, and vomiting, and are often set off or exacerbated by physical activity. The age-adjusted prevalence is estimated at 15.9% across all adults, but migraine is much more common in women, with a prevalence of 21% in women and 10.7% in men.

On the basis of the patient's history, clinical suspicion for chronic migraine should be high. Hemiplegic migraine usually presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes with speech disturbance. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are also unilateral but are characterized by their highly intense but short duration. Clinical suspicion for a space-occupying lesion should be raised in cases where patients with a history of headache present with new symptoms or abnormal signs.

The diagnosis of chronic migraine is a clinical one. The American Headache Society defines chronic migraine as at least five attacks of migraine-like or tension type–like headache that must fulfill specific criteria. If the migraine occurs with aura, it must occur 8 days or more per month for more than 3 months and be relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative. If the migraine occurs without aura, the same criteria apply, but it is important that the aforementioned signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). However, it is accepted that migraine treatment must be individualized, and that a trial-and-error period should be expected. Recent data suggest that about 30% of migraine patients who are prescribed a triptan have an insufficient response to this approach. Some research has shown that such patients have a better response after being switched to a second drug in the triptan class, while other studies have shown no difference. The patient in the current case might also be a candidate for preventive treatment, which should generally be considered when, in spite of acute treatment, migraine interferes with the patient's day-to-day routine or when attacks become frequent. The four CGRP monoclonal antibodies approved in the United States are eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a neurologic disease characterized by episodes of throbbing, often unilateral, headache. These attacks are associated with visual or other sensory symptoms (classic aura) related to the central nervous system, nausea, and vomiting, and are often set off or exacerbated by physical activity. The age-adjusted prevalence is estimated at 15.9% across all adults, but migraine is much more common in women, with a prevalence of 21% in women and 10.7% in men.

On the basis of the patient's history, clinical suspicion for chronic migraine should be high. Hemiplegic migraine usually presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes with speech disturbance. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are also unilateral but are characterized by their highly intense but short duration. Clinical suspicion for a space-occupying lesion should be raised in cases where patients with a history of headache present with new symptoms or abnormal signs.

The diagnosis of chronic migraine is a clinical one. The American Headache Society defines chronic migraine as at least five attacks of migraine-like or tension type–like headache that must fulfill specific criteria. If the migraine occurs with aura, it must occur 8 days or more per month for more than 3 months and be relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative. If the migraine occurs without aura, the same criteria apply, but it is important that the aforementioned signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). However, it is accepted that migraine treatment must be individualized, and that a trial-and-error period should be expected. Recent data suggest that about 30% of migraine patients who are prescribed a triptan have an insufficient response to this approach. Some research has shown that such patients have a better response after being switched to a second drug in the triptan class, while other studies have shown no difference. The patient in the current case might also be a candidate for preventive treatment, which should generally be considered when, in spite of acute treatment, migraine interferes with the patient's day-to-day routine or when attacks become frequent. The four CGRP monoclonal antibodies approved in the United States are eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a neurologic disease characterized by episodes of throbbing, often unilateral, headache. These attacks are associated with visual or other sensory symptoms (classic aura) related to the central nervous system, nausea, and vomiting, and are often set off or exacerbated by physical activity. The age-adjusted prevalence is estimated at 15.9% across all adults, but migraine is much more common in women, with a prevalence of 21% in women and 10.7% in men.

On the basis of the patient's history, clinical suspicion for chronic migraine should be high. Hemiplegic migraine usually presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes with speech disturbance. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are also unilateral but are characterized by their highly intense but short duration. Clinical suspicion for a space-occupying lesion should be raised in cases where patients with a history of headache present with new symptoms or abnormal signs.

The diagnosis of chronic migraine is a clinical one. The American Headache Society defines chronic migraine as at least five attacks of migraine-like or tension type–like headache that must fulfill specific criteria. If the migraine occurs with aura, it must occur 8 days or more per month for more than 3 months and be relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative. If the migraine occurs without aura, the same criteria apply, but it is important that the aforementioned signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). However, it is accepted that migraine treatment must be individualized, and that a trial-and-error period should be expected. Recent data suggest that about 30% of migraine patients who are prescribed a triptan have an insufficient response to this approach. Some research has shown that such patients have a better response after being switched to a second drug in the triptan class, while other studies have shown no difference. The patient in the current case might also be a candidate for preventive treatment, which should generally be considered when, in spite of acute treatment, migraine interferes with the patient's day-to-day routine or when attacks become frequent. The four CGRP monoclonal antibodies approved in the United States are eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

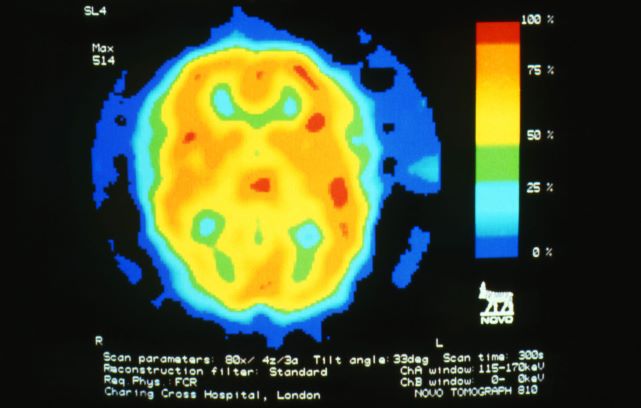

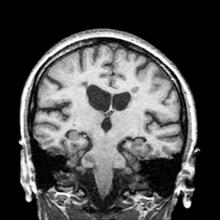

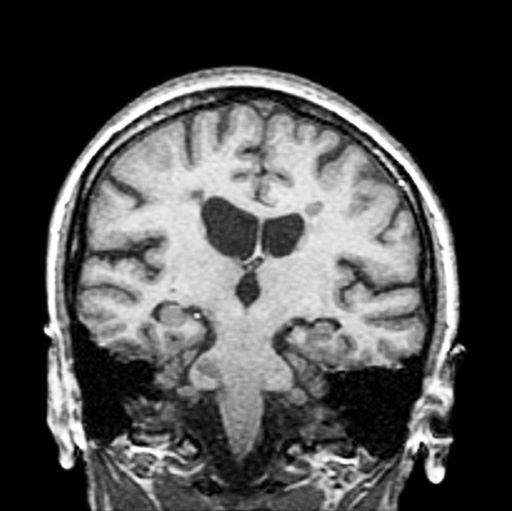

A 36-year-old man presents with severe pain in the frontotemporal area. He reports a history of severe headaches, sometimes with nausea. In the past year, these symptoms have begun to "knock him out" for nearly 2 weeks out of a month. The patient historically has been able to curtail his symptoms with a triptan. Physical examination is remarkable for Adie tonic pupil. A 1.5 T MRI of the brain is performed. Axial FLAIR sequence reveals scattered white matter lesions consistent with foci of demyelination.

Patient with tachycardia

On the basis of the patient's personal and family history together with his presentation, the likely diagnosis is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA). LADA is characterized by beta-cell loss and insulin resistance. This slowly evolving form of autoimmune diabetes comprises 2%-12% of all patients with adult-onset diabetes. Patients with LADA present with evidence of autoimmunity and varying C-peptide levels, which decrease more slowly in this subgroup than in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). They also have immunogenic markers associated with T1D, primarily anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies.

Patients with LADA are often misdiagnosed as having T2D. The clinical picture of LADA overlaps with that of T2D, with patients being insulin resistant and often overweight. In addition, presenting symptoms of LADA — excessive thirst, blurred vision, and high blood glucose — are also seen in T2D. Although LADA is technically classified as T1D, some groups posit that the condition exists on a spectrum between T1D and T2D. Compared with patients with T2D, those with LADA are generally younger at diagnosis (often in their 30s), have lower BMI, and report a personal or family history of autoimmune diseases, such as the patient in this quiz. Throughout the disease course, individuals with LADA show a reduced frequency of metabolic syndrome compared with those with T2D.

Key to diagnosis is the absence of insulin requirement for at least 6 months. Anti-GAD antibodies are the most sensitive marker for LADA; other autoantibodies that occur less frequently include ICA, IA-2A, ZnT8A, and tetraspanin 7 autoantibodies. With a paucity of large-scale clinical trials in LADA, current treatment strategies are not based on consensus guidelines, though an expert panel has published management recommendations. Category 1 patients (defined as a C-peptide level < 0.3 nmol/L) are treated with intensive insulin therapy. The recommendation for category 2 patients (defined as C-peptide values ≥ 0.3 and ≤ 0.7 nmol/L) is a modified American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes algorithm for T2D. However, patients with category 2 LADA may need to initiate insulin therapy earlier to combat beta-cell failure (ostensibly because LADA is an autoimmune disease beta-cell function declines much faster than in T2D). For category 3 patients (defined as C-peptide values > 0.7 nmol/L), treatment decisions are made in response to changing C-peptide levels.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's personal and family history together with his presentation, the likely diagnosis is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA). LADA is characterized by beta-cell loss and insulin resistance. This slowly evolving form of autoimmune diabetes comprises 2%-12% of all patients with adult-onset diabetes. Patients with LADA present with evidence of autoimmunity and varying C-peptide levels, which decrease more slowly in this subgroup than in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). They also have immunogenic markers associated with T1D, primarily anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies.

Patients with LADA are often misdiagnosed as having T2D. The clinical picture of LADA overlaps with that of T2D, with patients being insulin resistant and often overweight. In addition, presenting symptoms of LADA — excessive thirst, blurred vision, and high blood glucose — are also seen in T2D. Although LADA is technically classified as T1D, some groups posit that the condition exists on a spectrum between T1D and T2D. Compared with patients with T2D, those with LADA are generally younger at diagnosis (often in their 30s), have lower BMI, and report a personal or family history of autoimmune diseases, such as the patient in this quiz. Throughout the disease course, individuals with LADA show a reduced frequency of metabolic syndrome compared with those with T2D.

Key to diagnosis is the absence of insulin requirement for at least 6 months. Anti-GAD antibodies are the most sensitive marker for LADA; other autoantibodies that occur less frequently include ICA, IA-2A, ZnT8A, and tetraspanin 7 autoantibodies. With a paucity of large-scale clinical trials in LADA, current treatment strategies are not based on consensus guidelines, though an expert panel has published management recommendations. Category 1 patients (defined as a C-peptide level < 0.3 nmol/L) are treated with intensive insulin therapy. The recommendation for category 2 patients (defined as C-peptide values ≥ 0.3 and ≤ 0.7 nmol/L) is a modified American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes algorithm for T2D. However, patients with category 2 LADA may need to initiate insulin therapy earlier to combat beta-cell failure (ostensibly because LADA is an autoimmune disease beta-cell function declines much faster than in T2D). For category 3 patients (defined as C-peptide values > 0.7 nmol/L), treatment decisions are made in response to changing C-peptide levels.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On the basis of the patient's personal and family history together with his presentation, the likely diagnosis is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA). LADA is characterized by beta-cell loss and insulin resistance. This slowly evolving form of autoimmune diabetes comprises 2%-12% of all patients with adult-onset diabetes. Patients with LADA present with evidence of autoimmunity and varying C-peptide levels, which decrease more slowly in this subgroup than in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). They also have immunogenic markers associated with T1D, primarily anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies.

Patients with LADA are often misdiagnosed as having T2D. The clinical picture of LADA overlaps with that of T2D, with patients being insulin resistant and often overweight. In addition, presenting symptoms of LADA — excessive thirst, blurred vision, and high blood glucose — are also seen in T2D. Although LADA is technically classified as T1D, some groups posit that the condition exists on a spectrum between T1D and T2D. Compared with patients with T2D, those with LADA are generally younger at diagnosis (often in their 30s), have lower BMI, and report a personal or family history of autoimmune diseases, such as the patient in this quiz. Throughout the disease course, individuals with LADA show a reduced frequency of metabolic syndrome compared with those with T2D.

Key to diagnosis is the absence of insulin requirement for at least 6 months. Anti-GAD antibodies are the most sensitive marker for LADA; other autoantibodies that occur less frequently include ICA, IA-2A, ZnT8A, and tetraspanin 7 autoantibodies. With a paucity of large-scale clinical trials in LADA, current treatment strategies are not based on consensus guidelines, though an expert panel has published management recommendations. Category 1 patients (defined as a C-peptide level < 0.3 nmol/L) are treated with intensive insulin therapy. The recommendation for category 2 patients (defined as C-peptide values ≥ 0.3 and ≤ 0.7 nmol/L) is a modified American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes algorithm for T2D. However, patients with category 2 LADA may need to initiate insulin therapy earlier to combat beta-cell failure (ostensibly because LADA is an autoimmune disease beta-cell function declines much faster than in T2D). For category 3 patients (defined as C-peptide values > 0.7 nmol/L), treatment decisions are made in response to changing C-peptide levels.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 33-year-old man presents with blurred vision and tachycardia. Physical examination is remarkable for a BMI of 27 kg/m2. The patient explains that he feels he has lost weight. However, he attributes this change to a new exercise regimen he undertook when he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) about 8 months ago. The patient also notes polydipsia over a series of weeks. He reports that his first cousin may have lupus, though her diagnosis is still uncertain. Axial noncontrast CT demonstrates hyperattenuation that is more pronounced on the left side and involves the lentiform and caudate nuclei bilaterally.

History of AD with progressing flare

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

A 9-year-old girl with a history of moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) presents with a rapidly progressing AD flare. The patient had been stable over the past 6 months with the use of daily emollients. Over the past 36-48 hours, the patient developed pruritic lesions and pustules on her knees and elbows, and erythema and scaling around the eyes. Physical examination reveals a temperature of 101.5°F (38.6°C), a heart rate of 112 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, and a blood pressure of 100/95 mm Hg. Physical findings include cutaneous erythema and warmth surrounding the affected areas, pustules with yellow fluid, and regional lymphadenopathy.

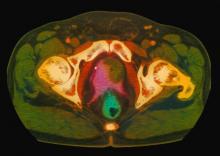

Complaints of incomplete bladder emptying

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

A 61-year-old man presents with complaints of frequent urination and incomplete bladder emptying. He also has been feeling fatigued but cannot tell if this is because his symptoms are worse at night and he has not been sleeping well. Despite a family history of atrial fibrillation, he reports no significant medical history beyond appendicitis many years ago. The patient underwent a prostate cancer screening about 18 months ago, which was normal. During a recent office visit, digital rectal examination (DRE) was normal, but prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels were elevated at 10.2 ng/mL. An MRI is performed as part of the workup.

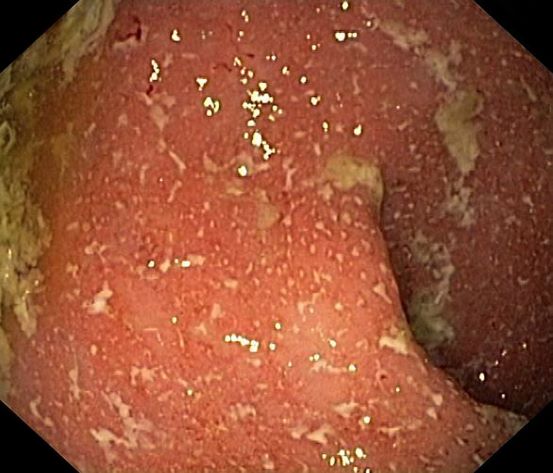

Boy presents with abdominal cramping

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 5-year-old boy presents with abdominal cramping and bloody stools over the course of 2 days. His mother explains that the onset of diarrhea was insidious. Because the patient has a sensitive stomach, she tries to keep his diet relatively bland, but she worries about what he eats at school. He is slightly underweight for his age group. The family has not traveled recently. The patient does not have a fever, but skin turgor is decreased. There is no evidence of fistulae or abscesses. His complete blood cell count is 10.6 g/dL.

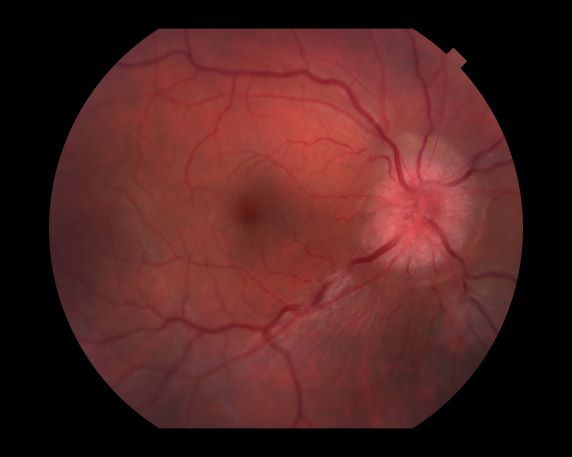

Decreased visual acuity and paresthesia

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.