User login

Reports of dysuria and nocturia

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

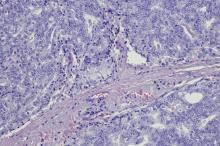

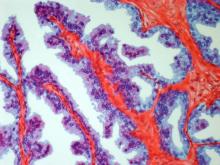

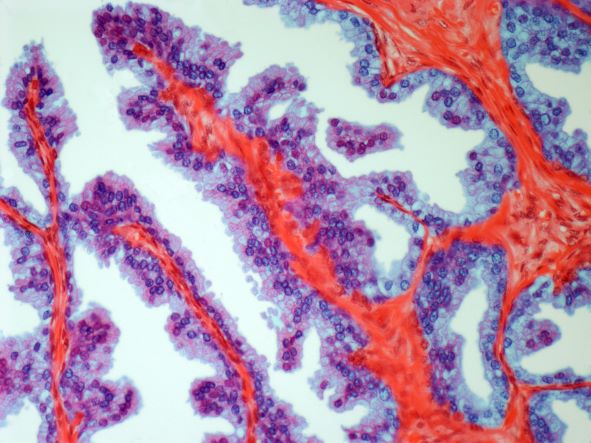

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

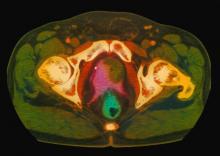

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

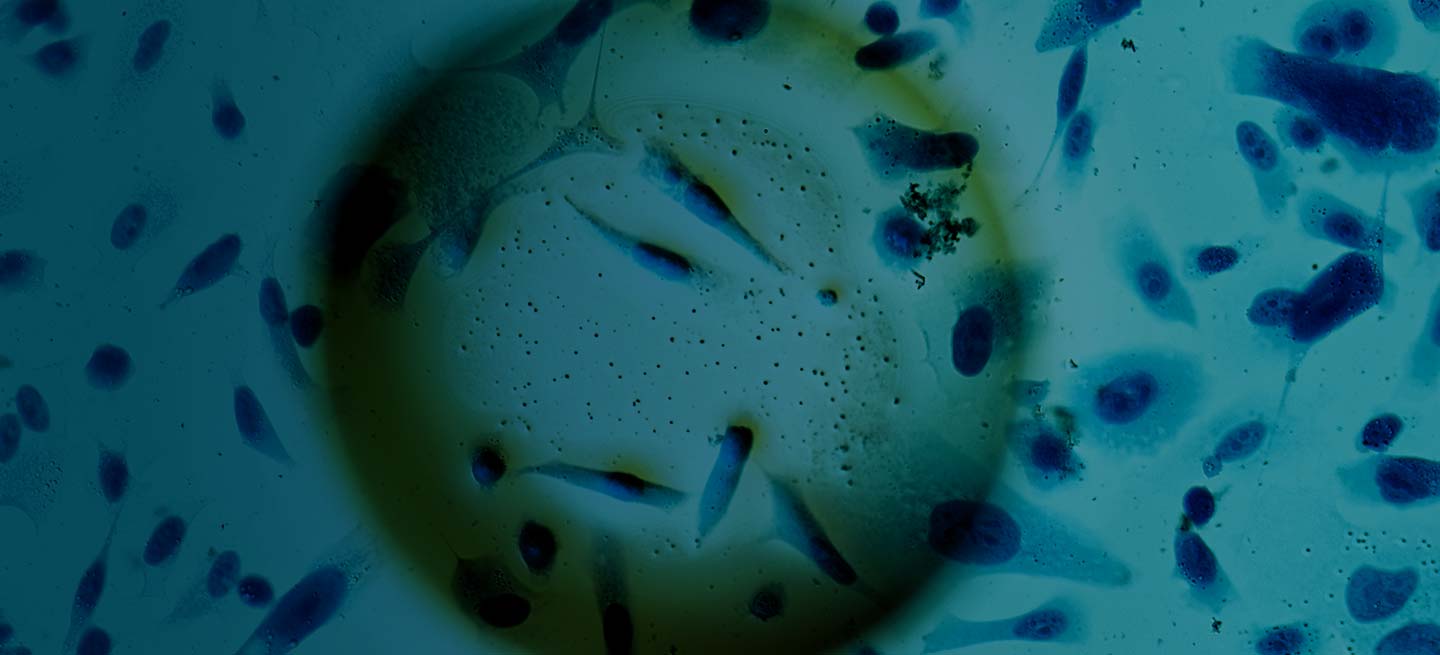

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 69-year-old nonsmoking African American man presents with reports of dysuria, nocturia, and unintentional weight loss. He reveals no other lower urinary tract symptoms, pelvic pain, night sweats, back pain, or excessive fatigue. Digital rectal exam reveals an enlarged prostate with a firm, irregular nodule at the right side of the gland. Laboratory tests reveal a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 2.22 ng/mL; a comprehensive metabolic panel and CBC are within normal limits. The patient is 6 ft 1 in and weighs 187 lb.

A transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy is performed. Histologic examination reveals immunoreactivity for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and expression of transcription factor 1. A proliferation of small cells (> 4 lymphocytes in diameter) is noted, with scant cytoplasm, poorly defined borders, finely granular salt-and-pepper chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and a high mitotic count. Evidence of perineural invasion is noted.

Urinating multiple times per night

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, this is likely a case of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Although most patients with prostate cancer are diagnosed on screening, when localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. In some cases, these signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions; benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA (but because this patient does not report pain, nonbacterial prostatitis is unlikely). Symptomatic patients older than 50 years, such as the one in this case, should be screened for prostate cancer. Those with a PSA > 10 ng/mL are more than 50% likely to have prostate cancer.

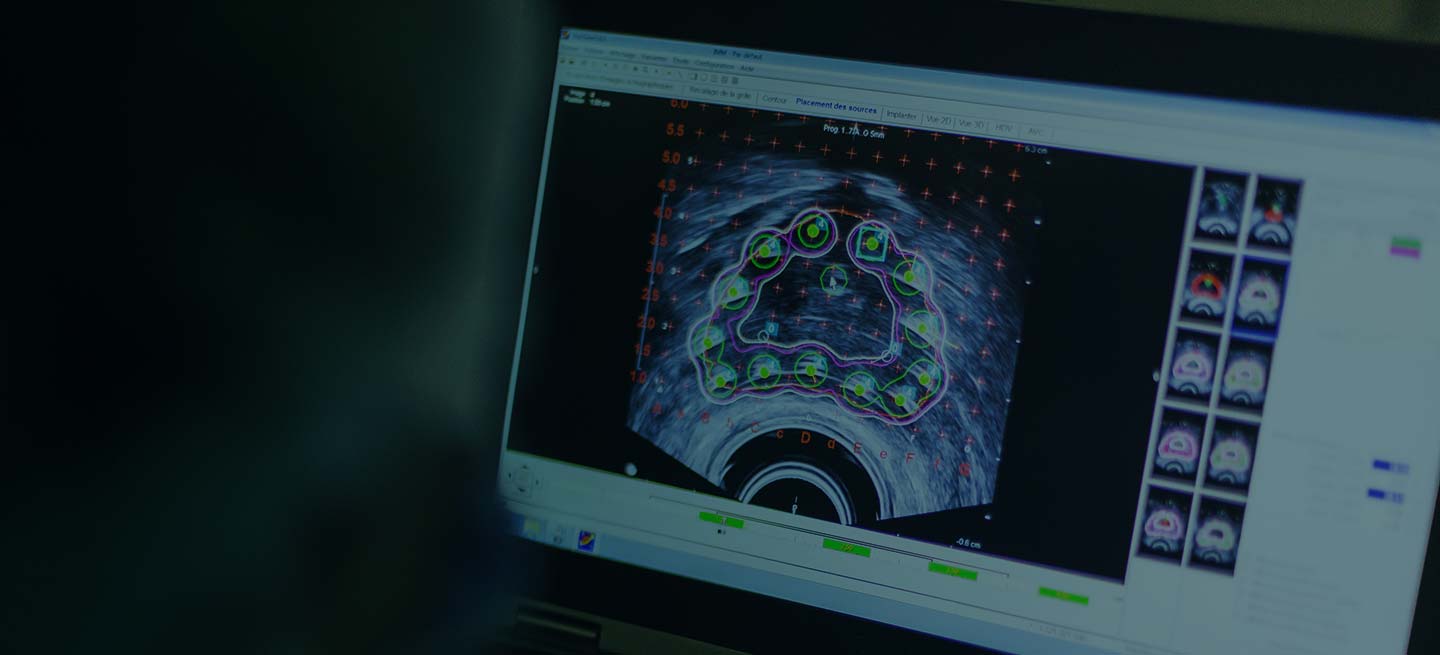

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines advise that needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis in those with elevated PSA levels, preferably via a transrectal ultrasound. MRI can be used to assess lesions that are concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. The clinician should ask about high-risk germline mutations and estimate life expectancy because course of treatment is largely based on risk assessment.

Standard treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. Active surveillance is often recommended for those who have very-low-risk disease because of the slow growth of certain types of prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy is a viable option for any patient with localized disease that can be completely excised surgically, provided the patient has a life expectancy of 10 or more years and no serious comorbidities. In some patients, radical prostatectomy may be followed by radiation with or without a short course of hormone treatment, depending on risk factors for recurrence. Radiation therapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered in the form of external-beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious underlying conditions, observation may be recommended.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, this is likely a case of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Although most patients with prostate cancer are diagnosed on screening, when localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. In some cases, these signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions; benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA (but because this patient does not report pain, nonbacterial prostatitis is unlikely). Symptomatic patients older than 50 years, such as the one in this case, should be screened for prostate cancer. Those with a PSA > 10 ng/mL are more than 50% likely to have prostate cancer.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines advise that needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis in those with elevated PSA levels, preferably via a transrectal ultrasound. MRI can be used to assess lesions that are concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. The clinician should ask about high-risk germline mutations and estimate life expectancy because course of treatment is largely based on risk assessment.

Standard treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. Active surveillance is often recommended for those who have very-low-risk disease because of the slow growth of certain types of prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy is a viable option for any patient with localized disease that can be completely excised surgically, provided the patient has a life expectancy of 10 or more years and no serious comorbidities. In some patients, radical prostatectomy may be followed by radiation with or without a short course of hormone treatment, depending on risk factors for recurrence. Radiation therapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered in the form of external-beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious underlying conditions, observation may be recommended.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, this is likely a case of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Although most patients with prostate cancer are diagnosed on screening, when localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. In some cases, these signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions; benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA (but because this patient does not report pain, nonbacterial prostatitis is unlikely). Symptomatic patients older than 50 years, such as the one in this case, should be screened for prostate cancer. Those with a PSA > 10 ng/mL are more than 50% likely to have prostate cancer.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines advise that needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis in those with elevated PSA levels, preferably via a transrectal ultrasound. MRI can be used to assess lesions that are concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. The clinician should ask about high-risk germline mutations and estimate life expectancy because course of treatment is largely based on risk assessment.

Standard treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. Active surveillance is often recommended for those who have very-low-risk disease because of the slow growth of certain types of prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy is a viable option for any patient with localized disease that can be completely excised surgically, provided the patient has a life expectancy of 10 or more years and no serious comorbidities. In some patients, radical prostatectomy may be followed by radiation with or without a short course of hormone treatment, depending on risk factors for recurrence. Radiation therapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered in the form of external-beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious underlying conditions, observation may be recommended.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old man presents for routine prostate cancer screening. He notes that he has not been sleeping well as a result of getting up to urinate multiple times per night for the past few months. The patient underwent a prostate cancer screening about 26 months ago, and results were normal. On examination, digital rectal examination is normal, but prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are elevated at 10.2 ng/mL.

Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer

Complaints of incomplete bladder emptying

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

A 61-year-old man presents with complaints of frequent urination and incomplete bladder emptying. He also has been feeling fatigued but cannot tell if this is because his symptoms are worse at night and he has not been sleeping well. Despite a family history of atrial fibrillation, he reports no significant medical history beyond appendicitis many years ago. The patient underwent a prostate cancer screening about 18 months ago, which was normal. During a recent office visit, digital rectal examination (DRE) was normal, but prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels were elevated at 10.2 ng/mL. An MRI is performed as part of the workup.

Prostate Cancer: Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing

Weakness in the legs and edema

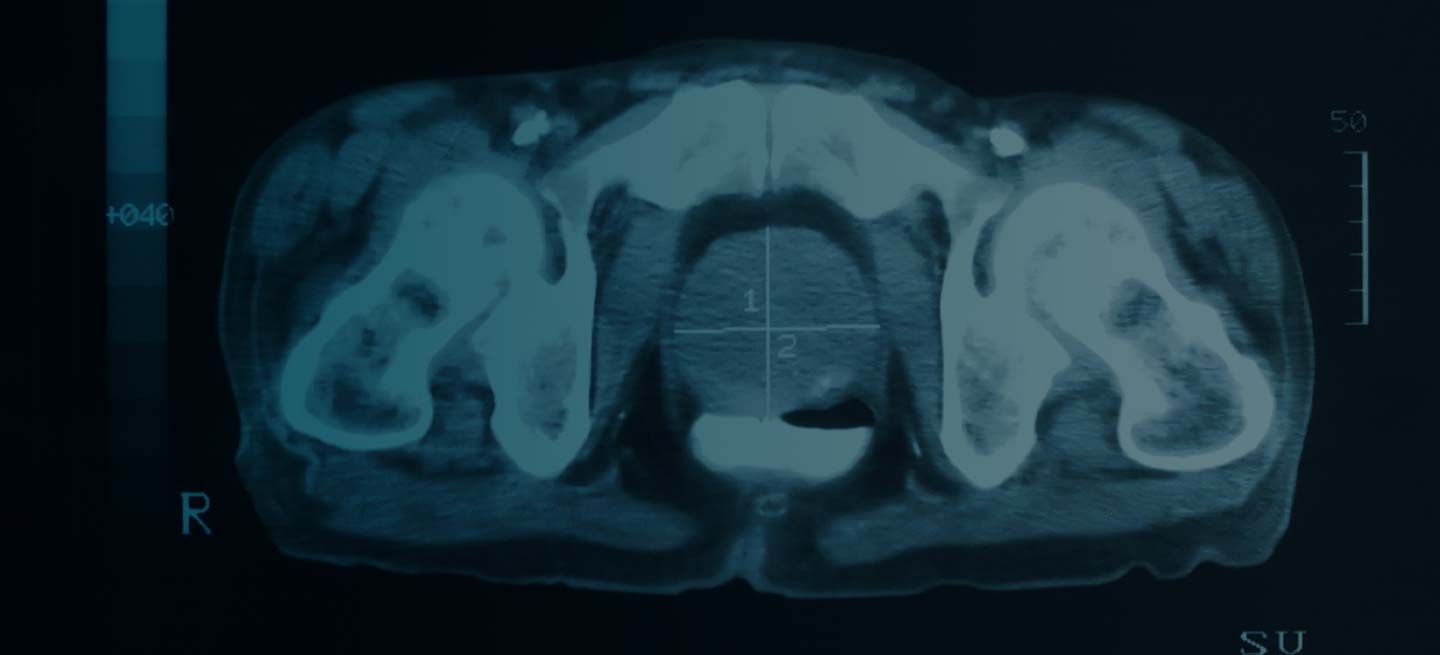

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 66-year-old male patient presents with weakness in the legs and edema. He takes medication to control his hypertension. About 8 years ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer during screening. Tumor staging was T3 and Gleason score was 8. The patient underwent successful radiation combined with hormone therapy. While he does not have urologic symptoms at this time, he does report that he is easily fatigued. Serum calcium is 10.6 mg/dL and hemoglobin is 10.5 g/dL. There is no evidence of neurologic deficit.