User login

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

Organs of Metastasis Predominate with Age in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Subtypes: National Cancer Database Analysis

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Background

Patients diagnosed with lung cancer are predominantly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Thus, it is imperative to investigate and distinguish the differences present at diagnosis to possibly improve survival outcomes. NSCLC commonly metastasizes within older patients near the mean age of 71 years, but also in early onset patients which represents the patients younger than the earliest lung cancer screening age of 50.

Objective

To reveal differences in ratios of metastasis locations in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ACC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC).

Methods

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was utilized to identify patients diagnosed with SCC, ACC, and ASC using the histology codes 8070, 8140, and 8560 from the ICD-O-3.2 from 2004 to 2022. Age groups were 70 years. Metastases located to the brain, liver, bone, and lung were included. Chi-Square tests were performed. The data was analyzed using R version 4.4.2 and statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results

In this study, 1,445,119 patients were analyzed. Chi-Square tests identified significant differences in the ratios of organ metastasis locations between age groups in each subtype (p < 0.001). SCC in each age group similarly metastasized most to bone (36.3%, 34.7%, 34.5%), but notably more local lung metastasis was observed in the oldest group (33.6%). In ACC and ASC, the oldest group also had greater ratios of spread within the lungs (28.0%, 27.2%). Overall, the younger the age group, distant spread to the brain increased (ex. 29.0%, 24.4%, 17.5%). This suggests a widely heterogenous distribution of metastases at diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes and patient age.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that patients with SCC, ACC, or ASC subtypes of NSCLC share similar predominant locations based in part on patient age, irrespective of cancer origin. NSCLC may more distantly metastasize in younger patients to the brain, while older patients may have locally metastatic cancer. Further analysis of key demographic variables as well as common undertaken treatment options may prove informative and reveal existing differences in survival outcomes.

Demographic and Clinical Factors Associated With PD-L1 Testing of Veterans With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Background

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) by improving overall survival compared to chemotherapy. PD-L1 biomarker testing is paramount for informing treatment decisions in aNSCLC. Real-world data describing patterns of PD-L1 testing within the Veteran Health Administration (VHA) are limited. This retrospective study seeks to evaluate demographic and clinical factors associated with PD-L1 testing in VHA.

Methods

Veterans diagnosed with aNSCLC from 2019-2022 were identified using VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse. Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Chi- Square tests measured association between receipt of PD-L1 testing and patient demographic and clinical characteristics at aNSCLC diagnosis. Logistic regression assessed predictors of PD-L1 testing, and subgroup analyses were performed for significant interactions.

Results

Our study included 4575 patients with aNSCLC; 57.0% received PD-L1 testing. The likelihood of PD-L1 testing increased among patients diagnosed with aNSCLC after 2019 vs during 2019 (OR≥1.118, p≤0.035) and in Black vs White patients (OR=1.227, p=0.011). However, the following had decreased likelihood of PD-L1 testing: patients with stage IIIB vs IV cancer (OR=0.683, p=0.004); non vs current/former smokers (OR=0.733, p=0.039); squamous (OR=0.863, p=0.030) or NOS (OR=0.695,p=0.013) vs. adenocarcinoma histology. Interactions were observed between patient residential region and residential rurality (p=0.003), and region and receipt of oncology community care consults (OCCC) (p=0.030). Patients in rural Midwest (OR=0.445,p=0.004) and rural South (OR=0.566, p=0.032) were less likely to receive PD-L1 testing than Metropolitan patients. Across patients with OCCC, Western US patients were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.554, p=0.001) than patients in other regions. However, within Midwestern patients, those without a OCCC were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.724, p< 0.001) than those with a OCCC. High comorbidity index (CCI≥3) is associated with an increased likelihood of PD-L1 testing in a univariable model (OR=1.286 vs. CCI=0,p=0.009), but not in the multivariable model (p=0.278).

Conclusions

We identified demographic and clinical factors, including regional differences in rurality and OCCC patterns, associated with PD-L1 testing. These factors can focus ongoing efforts to improve PD-L1 testing and efforts to be more in line with recommended care.

Background

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) by improving overall survival compared to chemotherapy. PD-L1 biomarker testing is paramount for informing treatment decisions in aNSCLC. Real-world data describing patterns of PD-L1 testing within the Veteran Health Administration (VHA) are limited. This retrospective study seeks to evaluate demographic and clinical factors associated with PD-L1 testing in VHA.

Methods

Veterans diagnosed with aNSCLC from 2019-2022 were identified using VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse. Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Chi- Square tests measured association between receipt of PD-L1 testing and patient demographic and clinical characteristics at aNSCLC diagnosis. Logistic regression assessed predictors of PD-L1 testing, and subgroup analyses were performed for significant interactions.

Results

Our study included 4575 patients with aNSCLC; 57.0% received PD-L1 testing. The likelihood of PD-L1 testing increased among patients diagnosed with aNSCLC after 2019 vs during 2019 (OR≥1.118, p≤0.035) and in Black vs White patients (OR=1.227, p=0.011). However, the following had decreased likelihood of PD-L1 testing: patients with stage IIIB vs IV cancer (OR=0.683, p=0.004); non vs current/former smokers (OR=0.733, p=0.039); squamous (OR=0.863, p=0.030) or NOS (OR=0.695,p=0.013) vs. adenocarcinoma histology. Interactions were observed between patient residential region and residential rurality (p=0.003), and region and receipt of oncology community care consults (OCCC) (p=0.030). Patients in rural Midwest (OR=0.445,p=0.004) and rural South (OR=0.566, p=0.032) were less likely to receive PD-L1 testing than Metropolitan patients. Across patients with OCCC, Western US patients were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.554, p=0.001) than patients in other regions. However, within Midwestern patients, those without a OCCC were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.724, p< 0.001) than those with a OCCC. High comorbidity index (CCI≥3) is associated with an increased likelihood of PD-L1 testing in a univariable model (OR=1.286 vs. CCI=0,p=0.009), but not in the multivariable model (p=0.278).

Conclusions

We identified demographic and clinical factors, including regional differences in rurality and OCCC patterns, associated with PD-L1 testing. These factors can focus ongoing efforts to improve PD-L1 testing and efforts to be more in line with recommended care.

Background

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) by improving overall survival compared to chemotherapy. PD-L1 biomarker testing is paramount for informing treatment decisions in aNSCLC. Real-world data describing patterns of PD-L1 testing within the Veteran Health Administration (VHA) are limited. This retrospective study seeks to evaluate demographic and clinical factors associated with PD-L1 testing in VHA.

Methods

Veterans diagnosed with aNSCLC from 2019-2022 were identified using VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse. Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Chi- Square tests measured association between receipt of PD-L1 testing and patient demographic and clinical characteristics at aNSCLC diagnosis. Logistic regression assessed predictors of PD-L1 testing, and subgroup analyses were performed for significant interactions.

Results

Our study included 4575 patients with aNSCLC; 57.0% received PD-L1 testing. The likelihood of PD-L1 testing increased among patients diagnosed with aNSCLC after 2019 vs during 2019 (OR≥1.118, p≤0.035) and in Black vs White patients (OR=1.227, p=0.011). However, the following had decreased likelihood of PD-L1 testing: patients with stage IIIB vs IV cancer (OR=0.683, p=0.004); non vs current/former smokers (OR=0.733, p=0.039); squamous (OR=0.863, p=0.030) or NOS (OR=0.695,p=0.013) vs. adenocarcinoma histology. Interactions were observed between patient residential region and residential rurality (p=0.003), and region and receipt of oncology community care consults (OCCC) (p=0.030). Patients in rural Midwest (OR=0.445,p=0.004) and rural South (OR=0.566, p=0.032) were less likely to receive PD-L1 testing than Metropolitan patients. Across patients with OCCC, Western US patients were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.554, p=0.001) than patients in other regions. However, within Midwestern patients, those without a OCCC were more likely to receive PD-L1 testing (OR=1.724, p< 0.001) than those with a OCCC. High comorbidity index (CCI≥3) is associated with an increased likelihood of PD-L1 testing in a univariable model (OR=1.286 vs. CCI=0,p=0.009), but not in the multivariable model (p=0.278).

Conclusions

We identified demographic and clinical factors, including regional differences in rurality and OCCC patterns, associated with PD-L1 testing. These factors can focus ongoing efforts to improve PD-L1 testing and efforts to be more in line with recommended care.

Prognosis Paradox: Does HLA-B27 Improve the Prognosis of Immune-Related Pneumonitis in Metastatic Lung Cancer?

Background

Immune related adverse events (irAE) are a well-known complication in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) with checkpoint inhibitors and have been shown to improve overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) across multiple studies. However, studies have shown that the prognosis of NSCLCA differs depending on the type of immune related adverse event and the grade of the irAE. For instance, patients who experienced endocrine irAEs like thyroid, or adrenal insufficiency tended to have an improved OS and PFS, whereas patients who developed pneumonitis that required discontinuation of checkpoint inhibitors had worse OS and PFS. While the literature describes the prognostic impacts of irAEs on NSCLCA, there is still a dearth of information on the implications of HLA supertypes on the prognosis of NSCLCA following irAEs.

Case Presentation

To address this point and to ask a question, we would like to share the case of a patient with a 10-year history of inflammatory arthropathy related to HLA-B27 antigen prior to his diagnosis of T2bN2M1b adenosquamous lung cancer with liver metastases. The tumor was 100% PD-L1 expressive and the patient was treated with pembrolizumab. The patient developed central adrenal insufficiency 10 months after pembrolizumab was initiated which was treated with physiologic dosing of hydrocortisone. The patient later developed a grade 3 pneumonitis 62 months after initiation of pembrolizumab and was treated with systemic glucocorticoids. Due to recurrent hospitalizations for pneumonitis, pembrolizumab was discontinued at 70 months post initiation. At the time of discontinuation PET was positive. However, there was a decrease in hyperactivity of the primary tumor at 4 months post discontinuation of pembrolizumab and there have been serial negative PETS from 7 months to 13 months post discontinuation. This led us to ask the question of whether HLA-B27 is protective of the poor prognostic immune related pneumonitis in this patient?

Background

Immune related adverse events (irAE) are a well-known complication in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) with checkpoint inhibitors and have been shown to improve overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) across multiple studies. However, studies have shown that the prognosis of NSCLCA differs depending on the type of immune related adverse event and the grade of the irAE. For instance, patients who experienced endocrine irAEs like thyroid, or adrenal insufficiency tended to have an improved OS and PFS, whereas patients who developed pneumonitis that required discontinuation of checkpoint inhibitors had worse OS and PFS. While the literature describes the prognostic impacts of irAEs on NSCLCA, there is still a dearth of information on the implications of HLA supertypes on the prognosis of NSCLCA following irAEs.

Case Presentation

To address this point and to ask a question, we would like to share the case of a patient with a 10-year history of inflammatory arthropathy related to HLA-B27 antigen prior to his diagnosis of T2bN2M1b adenosquamous lung cancer with liver metastases. The tumor was 100% PD-L1 expressive and the patient was treated with pembrolizumab. The patient developed central adrenal insufficiency 10 months after pembrolizumab was initiated which was treated with physiologic dosing of hydrocortisone. The patient later developed a grade 3 pneumonitis 62 months after initiation of pembrolizumab and was treated with systemic glucocorticoids. Due to recurrent hospitalizations for pneumonitis, pembrolizumab was discontinued at 70 months post initiation. At the time of discontinuation PET was positive. However, there was a decrease in hyperactivity of the primary tumor at 4 months post discontinuation of pembrolizumab and there have been serial negative PETS from 7 months to 13 months post discontinuation. This led us to ask the question of whether HLA-B27 is protective of the poor prognostic immune related pneumonitis in this patient?

Background

Immune related adverse events (irAE) are a well-known complication in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) with checkpoint inhibitors and have been shown to improve overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) across multiple studies. However, studies have shown that the prognosis of NSCLCA differs depending on the type of immune related adverse event and the grade of the irAE. For instance, patients who experienced endocrine irAEs like thyroid, or adrenal insufficiency tended to have an improved OS and PFS, whereas patients who developed pneumonitis that required discontinuation of checkpoint inhibitors had worse OS and PFS. While the literature describes the prognostic impacts of irAEs on NSCLCA, there is still a dearth of information on the implications of HLA supertypes on the prognosis of NSCLCA following irAEs.

Case Presentation

To address this point and to ask a question, we would like to share the case of a patient with a 10-year history of inflammatory arthropathy related to HLA-B27 antigen prior to his diagnosis of T2bN2M1b adenosquamous lung cancer with liver metastases. The tumor was 100% PD-L1 expressive and the patient was treated with pembrolizumab. The patient developed central adrenal insufficiency 10 months after pembrolizumab was initiated which was treated with physiologic dosing of hydrocortisone. The patient later developed a grade 3 pneumonitis 62 months after initiation of pembrolizumab and was treated with systemic glucocorticoids. Due to recurrent hospitalizations for pneumonitis, pembrolizumab was discontinued at 70 months post initiation. At the time of discontinuation PET was positive. However, there was a decrease in hyperactivity of the primary tumor at 4 months post discontinuation of pembrolizumab and there have been serial negative PETS from 7 months to 13 months post discontinuation. This led us to ask the question of whether HLA-B27 is protective of the poor prognostic immune related pneumonitis in this patient?

Brief Immunotherapy Yields Major Survival Benefits in Advanced NSCLC: A Case Report

Background

Lung cancer, primarily non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), typically presents at an advanced stage with a five-year survival rate below 5%. Treatment includes platinum-based chemotherapy and targeted therapies for specific mutations, with immunotherapy significantly improving outcomes for patients with high PD-L1 expression.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male, diagnosed with advanced lung adenocarcinoma in 2020 after showing symptoms of brain metastases, underwent successful surgical and CyberKnife treatments. Despite no actionable genetic targets and a high PD-L1 expression of 80%, his treatment with 3-cycles of Keytruda was cut short due to a psoriatic arthritis flare-up, though it initially decreased his CEA levels significantly. Over the following years, fluctuating CEA levels and various imaging studies indicated some concerning changes, such as potential radionecrosis or recurrence of cancer in the lung. His refusal of biopsy and a preference for avoiding invasive treatments led to only surveillance. Later, an MRI showed some metastasis, and the patient agreed to a lung biopsy, which showed poorly differentiated carcinoma of pulmonary origin. The patient only agreed to restart treatment with Keytruda 4-years later after his initial treatment with Keytruda, under close rheumatological care, and received only two doses. Afterward, the patient lost follow-ups. 3-months later, Repeated CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of mass or pathological lymph nodes, and repeated CEA was 3.4.

Discussion

Managing advanced lung adenocarcinoma, especially with complications like brain metastases and psoriatic arthritis, is challenging. Pembrolizumab treatment showed promise by significantly reducing CEA levels despite early discontinuation due to autoimmune side effects, indicating effective tumor response in patients with high PD-L1 expression. The case underscores the need for balancing cancer treatment with autoimmune management and highlights the importance of patient preferences in treatment plans. Ongoing surveillance and genomic profiling remain crucial for guiding therapy.

Conclusions

This case of a 70-year-old male with advanced lung adenocarcinoma highlights the significant impact of immunotherapy, particularly PD-1/ PD-L1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab, in NSCLC. Despite a brief treatment period, the patient experienced extended disease control, demonstrating the potential of immunotherapy to enhance survival and its broad applicability in oncology.

Background

Lung cancer, primarily non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), typically presents at an advanced stage with a five-year survival rate below 5%. Treatment includes platinum-based chemotherapy and targeted therapies for specific mutations, with immunotherapy significantly improving outcomes for patients with high PD-L1 expression.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male, diagnosed with advanced lung adenocarcinoma in 2020 after showing symptoms of brain metastases, underwent successful surgical and CyberKnife treatments. Despite no actionable genetic targets and a high PD-L1 expression of 80%, his treatment with 3-cycles of Keytruda was cut short due to a psoriatic arthritis flare-up, though it initially decreased his CEA levels significantly. Over the following years, fluctuating CEA levels and various imaging studies indicated some concerning changes, such as potential radionecrosis or recurrence of cancer in the lung. His refusal of biopsy and a preference for avoiding invasive treatments led to only surveillance. Later, an MRI showed some metastasis, and the patient agreed to a lung biopsy, which showed poorly differentiated carcinoma of pulmonary origin. The patient only agreed to restart treatment with Keytruda 4-years later after his initial treatment with Keytruda, under close rheumatological care, and received only two doses. Afterward, the patient lost follow-ups. 3-months later, Repeated CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of mass or pathological lymph nodes, and repeated CEA was 3.4.

Discussion

Managing advanced lung adenocarcinoma, especially with complications like brain metastases and psoriatic arthritis, is challenging. Pembrolizumab treatment showed promise by significantly reducing CEA levels despite early discontinuation due to autoimmune side effects, indicating effective tumor response in patients with high PD-L1 expression. The case underscores the need for balancing cancer treatment with autoimmune management and highlights the importance of patient preferences in treatment plans. Ongoing surveillance and genomic profiling remain crucial for guiding therapy.

Conclusions

This case of a 70-year-old male with advanced lung adenocarcinoma highlights the significant impact of immunotherapy, particularly PD-1/ PD-L1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab, in NSCLC. Despite a brief treatment period, the patient experienced extended disease control, demonstrating the potential of immunotherapy to enhance survival and its broad applicability in oncology.

Background

Lung cancer, primarily non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), typically presents at an advanced stage with a five-year survival rate below 5%. Treatment includes platinum-based chemotherapy and targeted therapies for specific mutations, with immunotherapy significantly improving outcomes for patients with high PD-L1 expression.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male, diagnosed with advanced lung adenocarcinoma in 2020 after showing symptoms of brain metastases, underwent successful surgical and CyberKnife treatments. Despite no actionable genetic targets and a high PD-L1 expression of 80%, his treatment with 3-cycles of Keytruda was cut short due to a psoriatic arthritis flare-up, though it initially decreased his CEA levels significantly. Over the following years, fluctuating CEA levels and various imaging studies indicated some concerning changes, such as potential radionecrosis or recurrence of cancer in the lung. His refusal of biopsy and a preference for avoiding invasive treatments led to only surveillance. Later, an MRI showed some metastasis, and the patient agreed to a lung biopsy, which showed poorly differentiated carcinoma of pulmonary origin. The patient only agreed to restart treatment with Keytruda 4-years later after his initial treatment with Keytruda, under close rheumatological care, and received only two doses. Afterward, the patient lost follow-ups. 3-months later, Repeated CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of mass or pathological lymph nodes, and repeated CEA was 3.4.

Discussion

Managing advanced lung adenocarcinoma, especially with complications like brain metastases and psoriatic arthritis, is challenging. Pembrolizumab treatment showed promise by significantly reducing CEA levels despite early discontinuation due to autoimmune side effects, indicating effective tumor response in patients with high PD-L1 expression. The case underscores the need for balancing cancer treatment with autoimmune management and highlights the importance of patient preferences in treatment plans. Ongoing surveillance and genomic profiling remain crucial for guiding therapy.

Conclusions

This case of a 70-year-old male with advanced lung adenocarcinoma highlights the significant impact of immunotherapy, particularly PD-1/ PD-L1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab, in NSCLC. Despite a brief treatment period, the patient experienced extended disease control, demonstrating the potential of immunotherapy to enhance survival and its broad applicability in oncology.

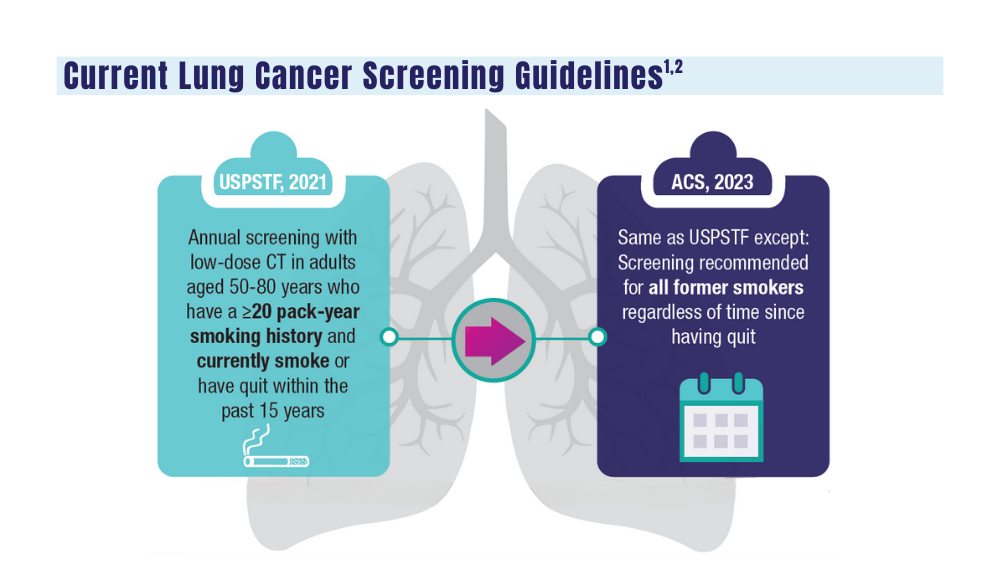

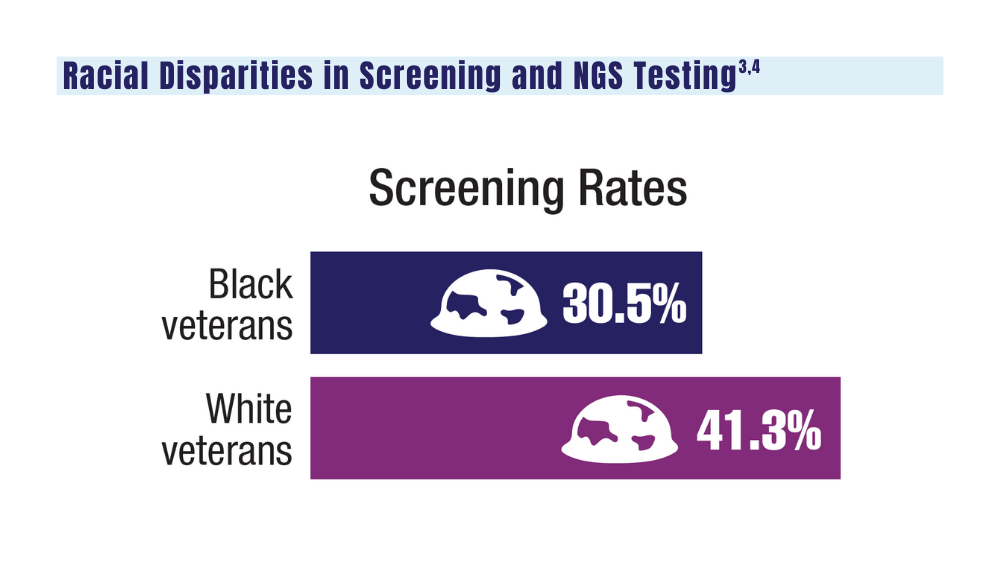

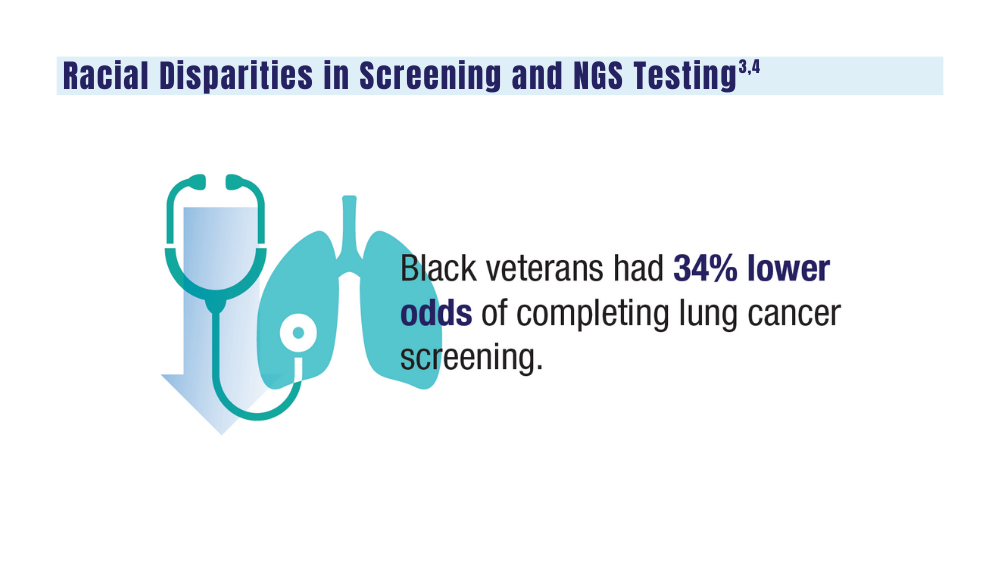

Cancer Data Trends 2024: Lung Cancer

1. Wolf AMD, Oeffinger KC, Shih TYC, et al. Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;10.3322/caac.21811. doi:10.3322/caac.21811

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA promotes high-quality, patient-centered lung cancer screening for veterans. Published June 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/impacts/lcs.cfm

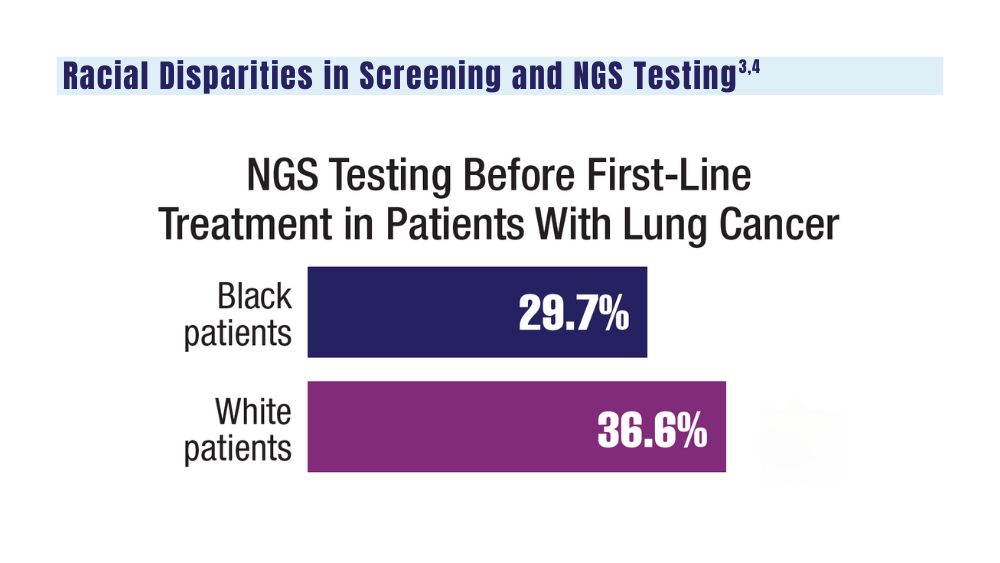

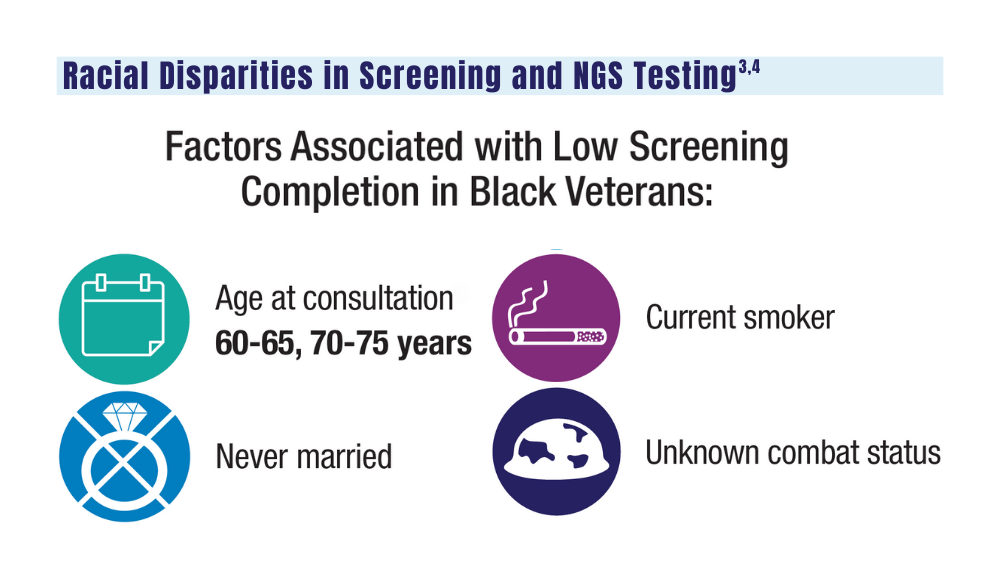

3. Navuluri N, Morrison S, Green CL, et al. Racial disparities in lung cancer screening among veterans, 2013 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2318795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18795

4. Bruno DS, Hess LM, Li X, Su EW, Patel M. Disparities in biomarker testing and clinical trial enrollment among patients with lung, breast, or colorectal cancers in the United States. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100427. doi:10.1200/PO.21.00427

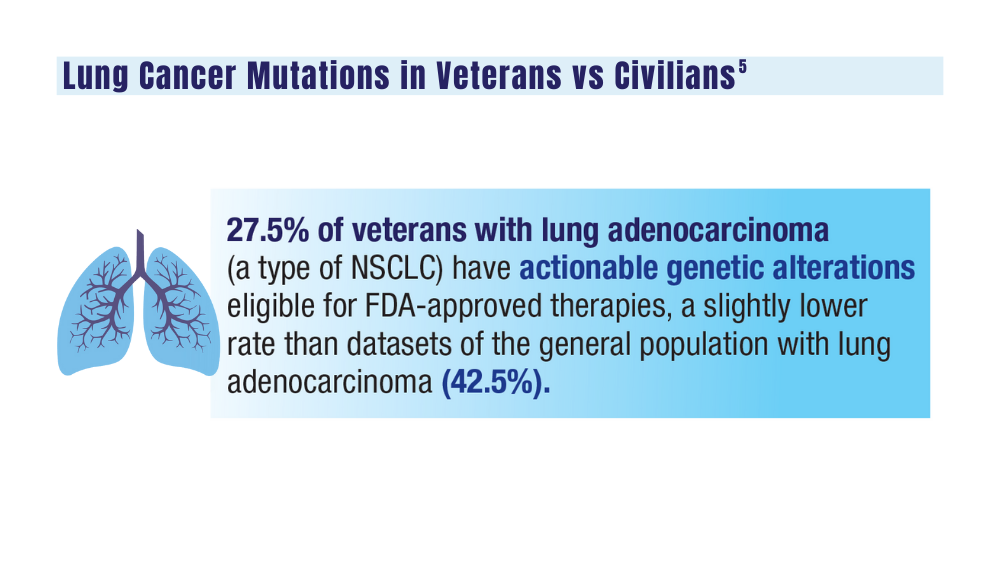

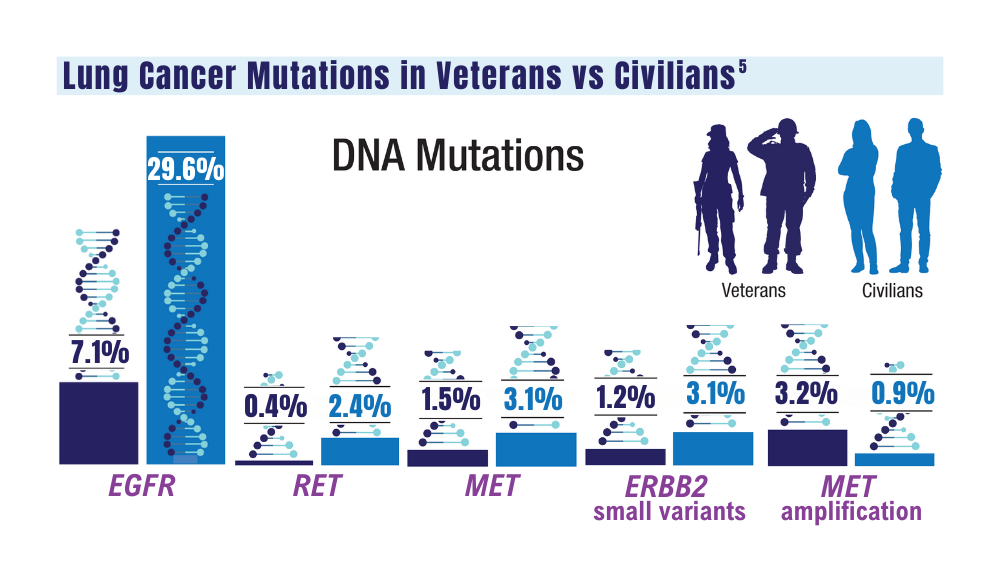

5. Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00054-9. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014

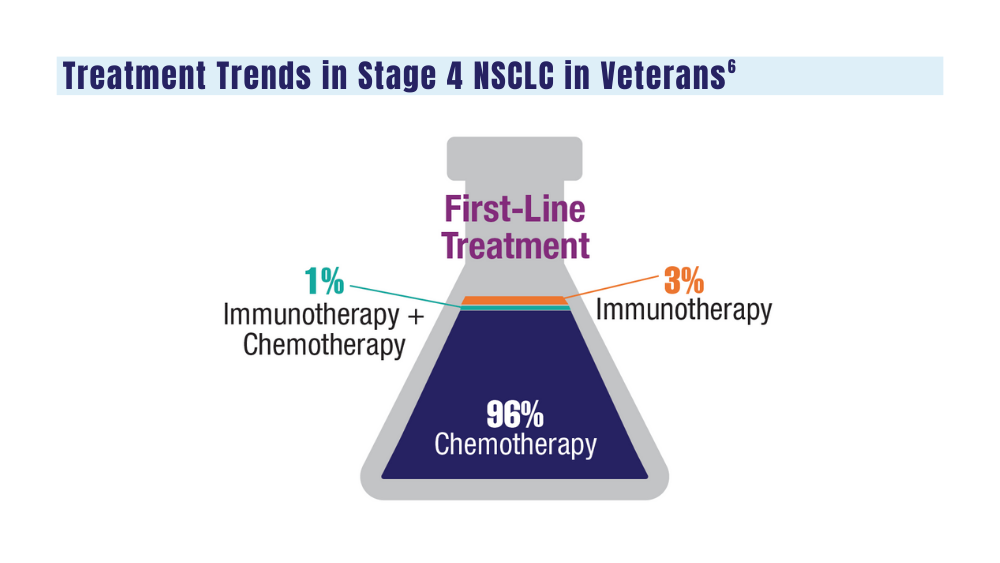

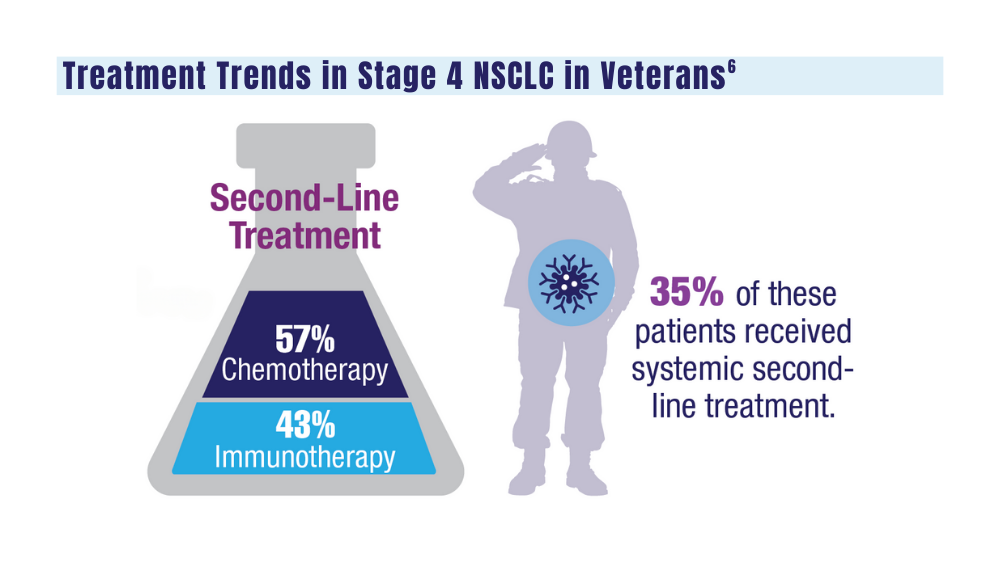

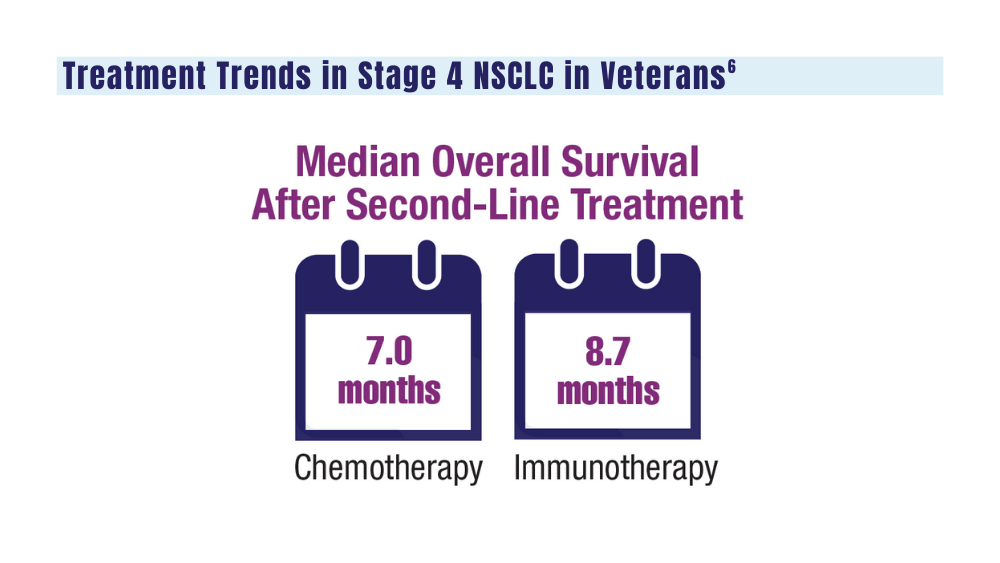

6. Williams CD, Allo MA, Gu L, Vashistha V, Press A, Kelley M. Health outcomes and healthcare resource utilization among veterans with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer treated with second-line chemotherapy versus immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0282020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0282020

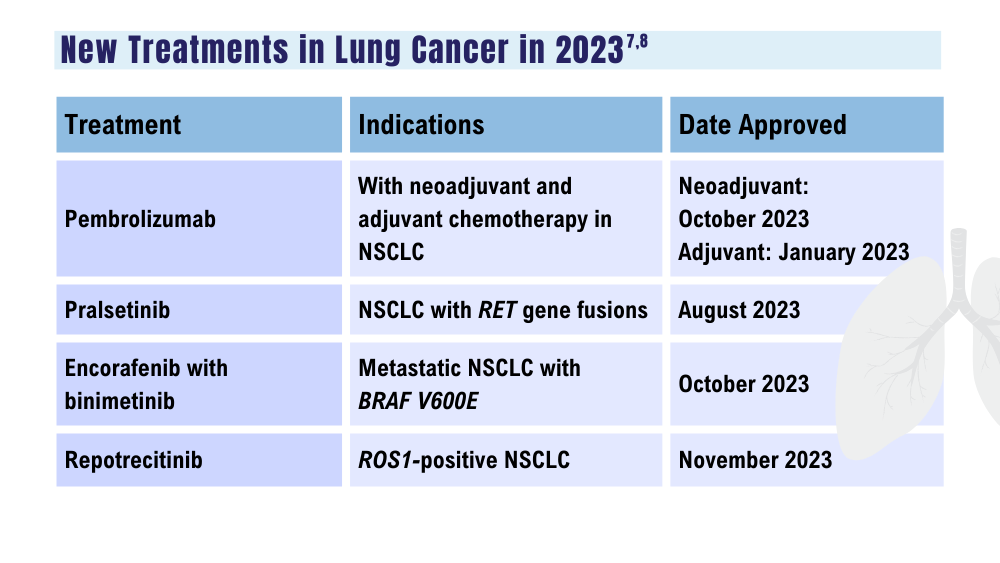

7. US Food and Drug Administration. Oncology (cancer)/hematologic malignancies approval notifications. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/oncology-cancer-hematologic-malignancies-approval-notifications

8. Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100408. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100408

1. Wolf AMD, Oeffinger KC, Shih TYC, et al. Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;10.3322/caac.21811. doi:10.3322/caac.21811

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA promotes high-quality, patient-centered lung cancer screening for veterans. Published June 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/impacts/lcs.cfm

3. Navuluri N, Morrison S, Green CL, et al. Racial disparities in lung cancer screening among veterans, 2013 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2318795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18795

4. Bruno DS, Hess LM, Li X, Su EW, Patel M. Disparities in biomarker testing and clinical trial enrollment among patients with lung, breast, or colorectal cancers in the United States. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100427. doi:10.1200/PO.21.00427

5. Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00054-9. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014

6. Williams CD, Allo MA, Gu L, Vashistha V, Press A, Kelley M. Health outcomes and healthcare resource utilization among veterans with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer treated with second-line chemotherapy versus immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0282020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0282020

7. US Food and Drug Administration. Oncology (cancer)/hematologic malignancies approval notifications. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/oncology-cancer-hematologic-malignancies-approval-notifications

8. Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100408. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100408

1. Wolf AMD, Oeffinger KC, Shih TYC, et al. Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;10.3322/caac.21811. doi:10.3322/caac.21811

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA promotes high-quality, patient-centered lung cancer screening for veterans. Published June 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/impacts/lcs.cfm

3. Navuluri N, Morrison S, Green CL, et al. Racial disparities in lung cancer screening among veterans, 2013 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2318795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18795

4. Bruno DS, Hess LM, Li X, Su EW, Patel M. Disparities in biomarker testing and clinical trial enrollment among patients with lung, breast, or colorectal cancers in the United States. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100427. doi:10.1200/PO.21.00427

5. Jalal SI, Guo A, Ahmed S, Kelley MJ. Analysis of actionable genetic alterations in lung carcinoma from the VA National Precision Oncology Program. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00054-9. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.014

6. Williams CD, Allo MA, Gu L, Vashistha V, Press A, Kelley M. Health outcomes and healthcare resource utilization among veterans with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer treated with second-line chemotherapy versus immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0282020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0282020

7. US Food and Drug Administration. Oncology (cancer)/hematologic malignancies approval notifications. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/oncology-cancer-hematologic-malignancies-approval-notifications

8. Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100408. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100408

Cancer Data Trends 2024

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

Chest pain and shortness of breath

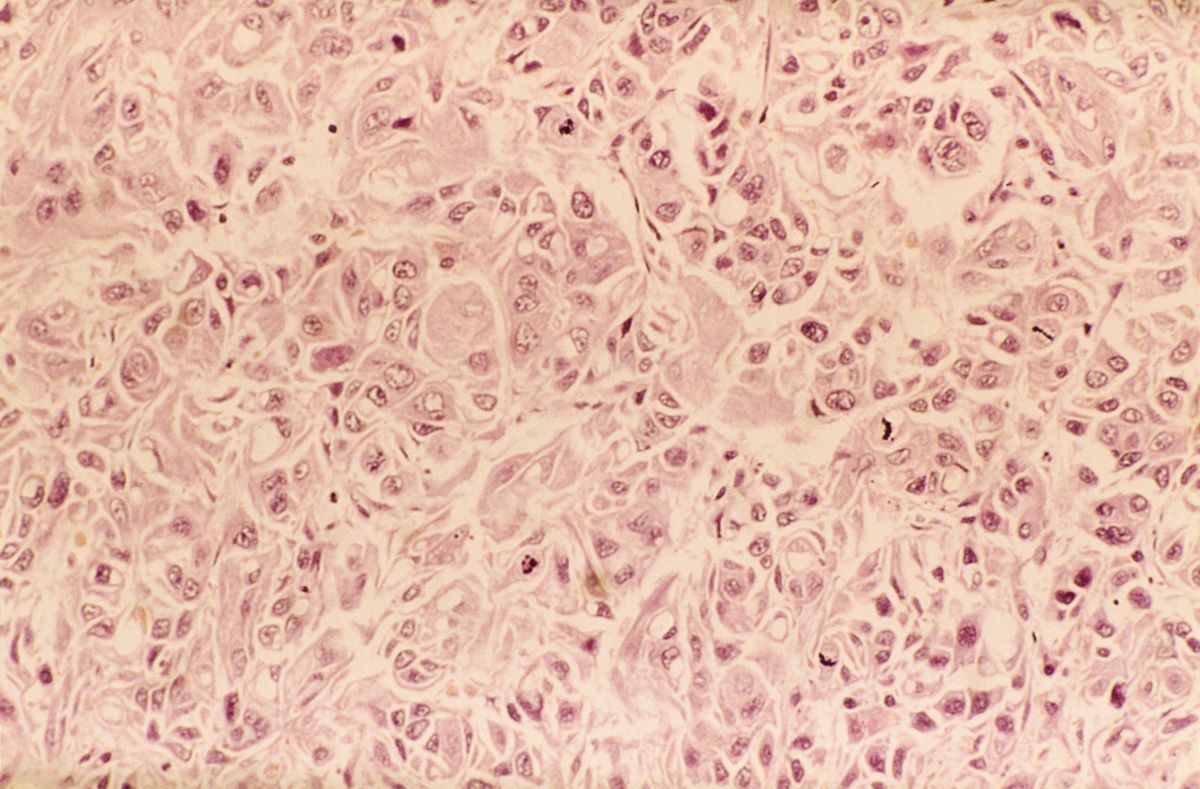

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with a persistent cough, dyspnea, unintentional weight loss, and fatigue over the past few months. He has a history of smoking for 30 years but quit 5 years ago. He also reports occasional chest pain and shortness of breath during physical activities. Physical examination reveals crackles in the middle lobe of the right lung. The patient occasionally coughs up blood. Chest radiography shows a large mass in the right lung, and a subsequent CT scan confirms a large peripheral mass of solid attenuation with an irregular margin. The patient undergoes thoracoscopy to obtain a biopsy sample from the tumor for further analysis. The biopsy reveals glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation.

NSCLC- Clinical Presentation

Complaints of cough and fatigue

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 67-year-old White man presents to the emergency department with reports of cough, dyspnea, fatigue, hoarseness, and unintentional weight loss. The patient states that his symptoms began approximately 3 weeks earlier and have progressively worsened. In the past year, he has been treated twice for respiratory infections (bronchitis and pneumonia approximately 6 and 9 months before the current presentation, respectively). He has a 45-year history of smoking (45 pack-years). The patient's vital signs include temperature of 100.4 °F, blood pressure of 142/80 mm Hg, and pulse ox of 95%. Physical examination reveals rales in the left side of the chest and decreased breath sounds in bilateral bases of the lungs. The patient appears cachexic. He is 6 ft 2 in and weighs 163 lb.

A chest radiograph reveals a large mass in the left lung field. A subsequent CT of the chest reveals encasement of the left upper and lower lobe bronchus with extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy and areas of necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tumor reveals a malignant, poorly differentiated epithelial neoplasm composed of large, atypical cells. There is no morphologic or immunohistochemical evidence of glandular, squamous, or neuroendocrine differentiation.