User login

Reactive Angioendotheliomatosis Following Ad26.COV2.S Vaccination

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

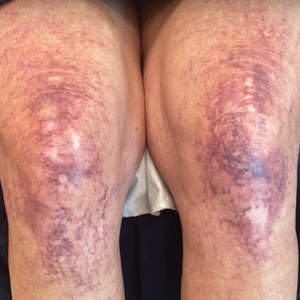

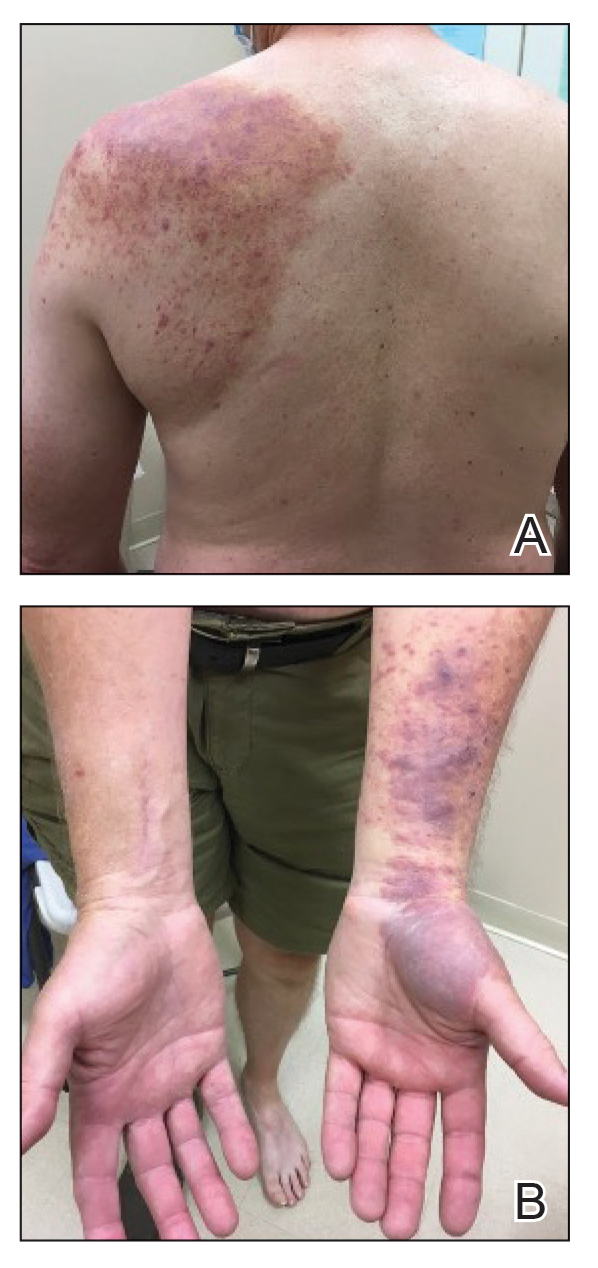

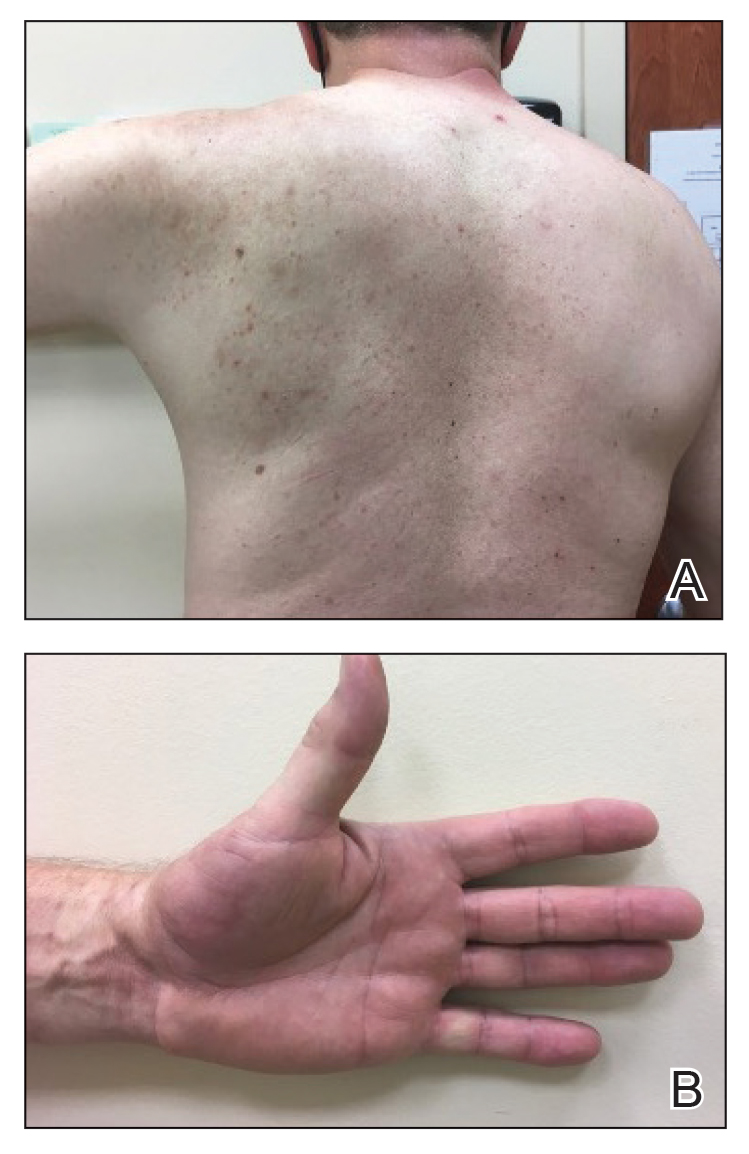

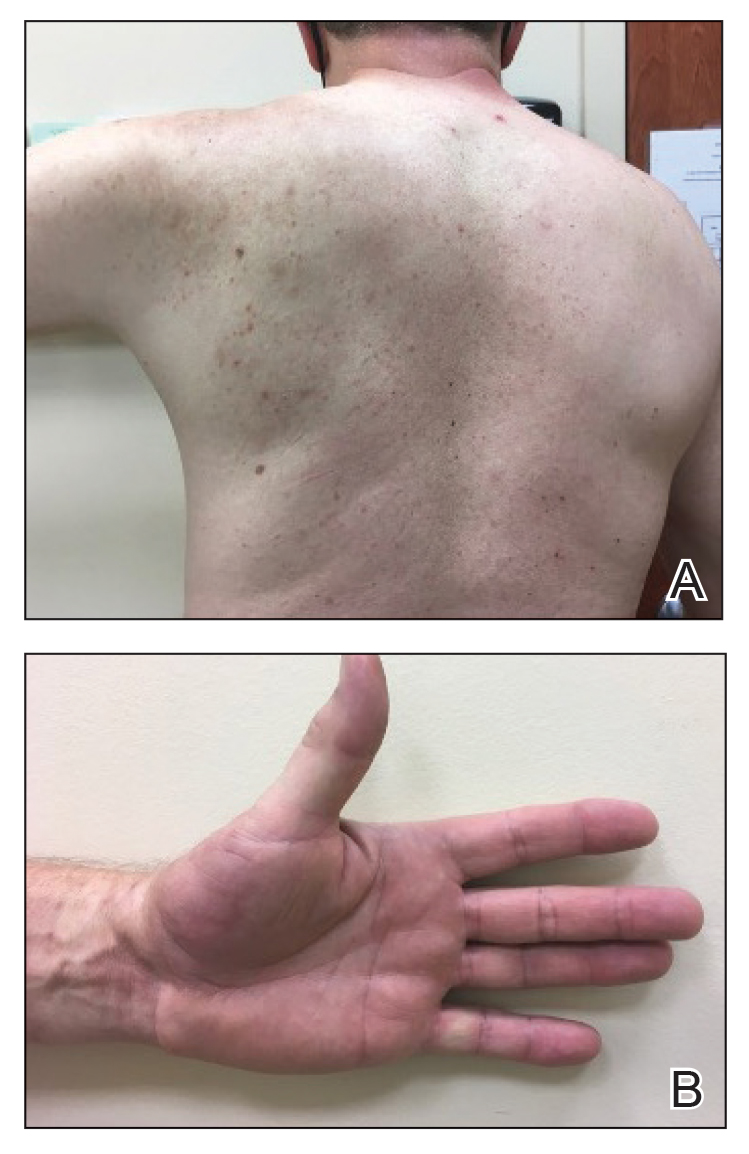

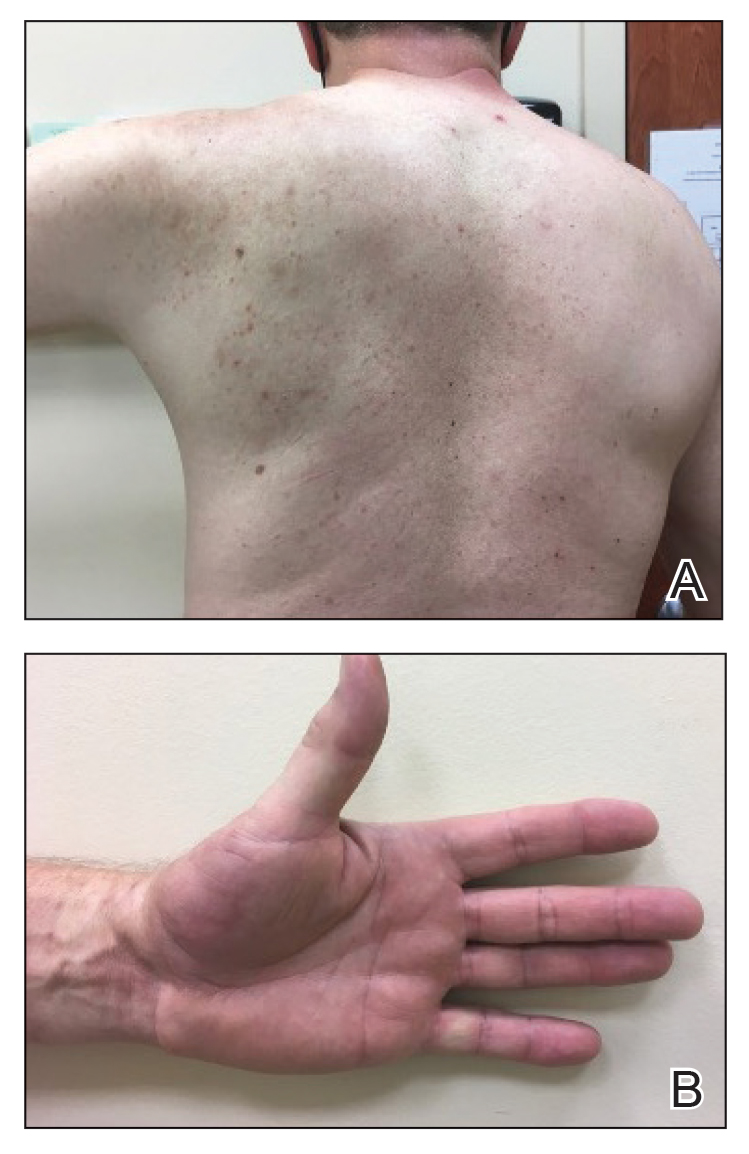

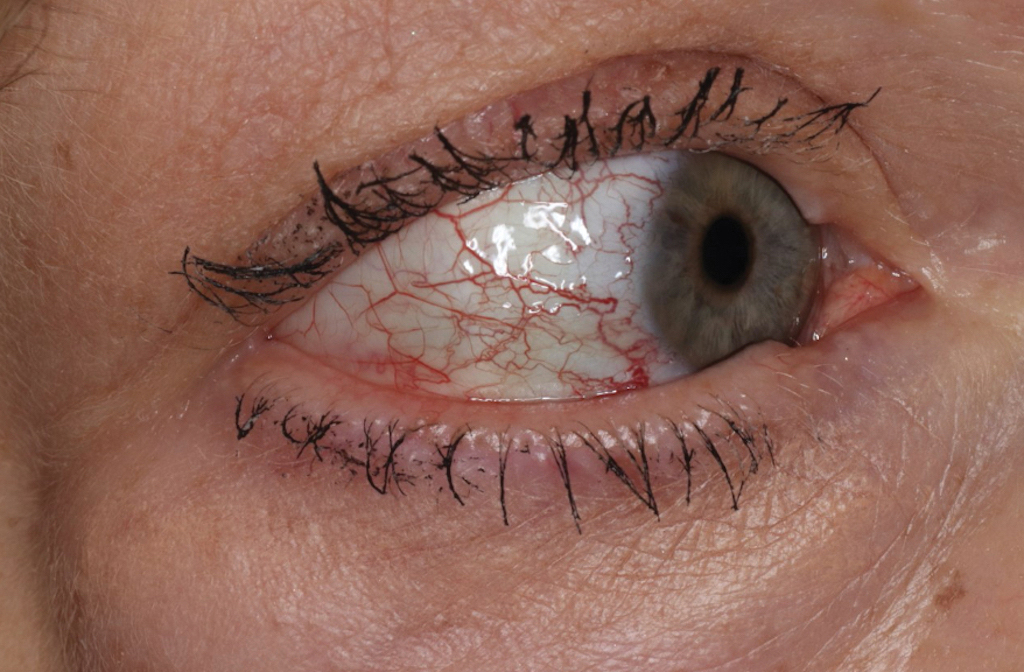

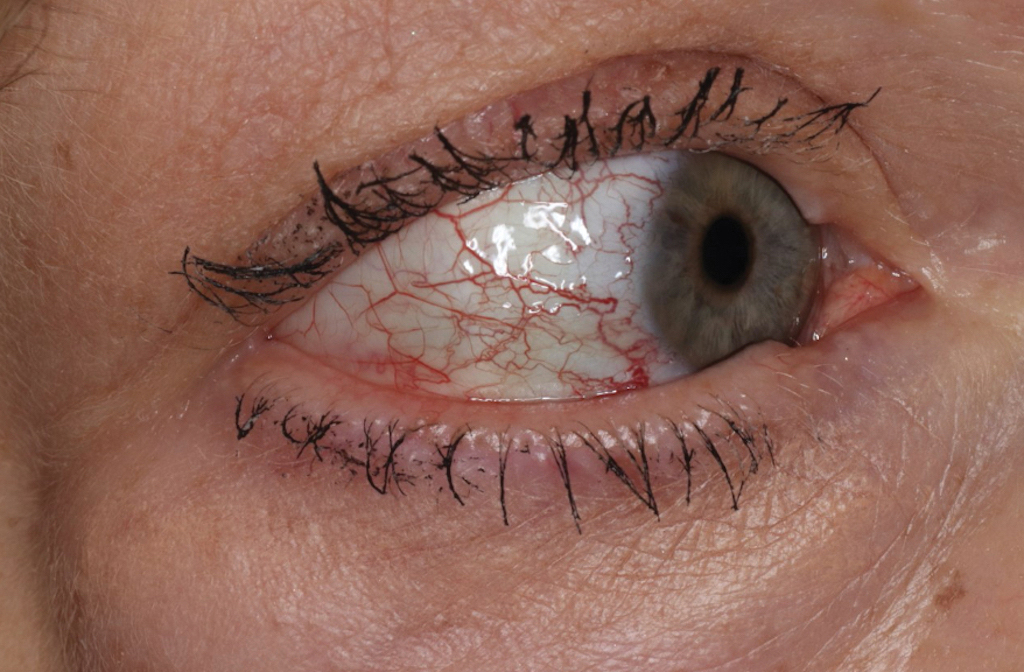

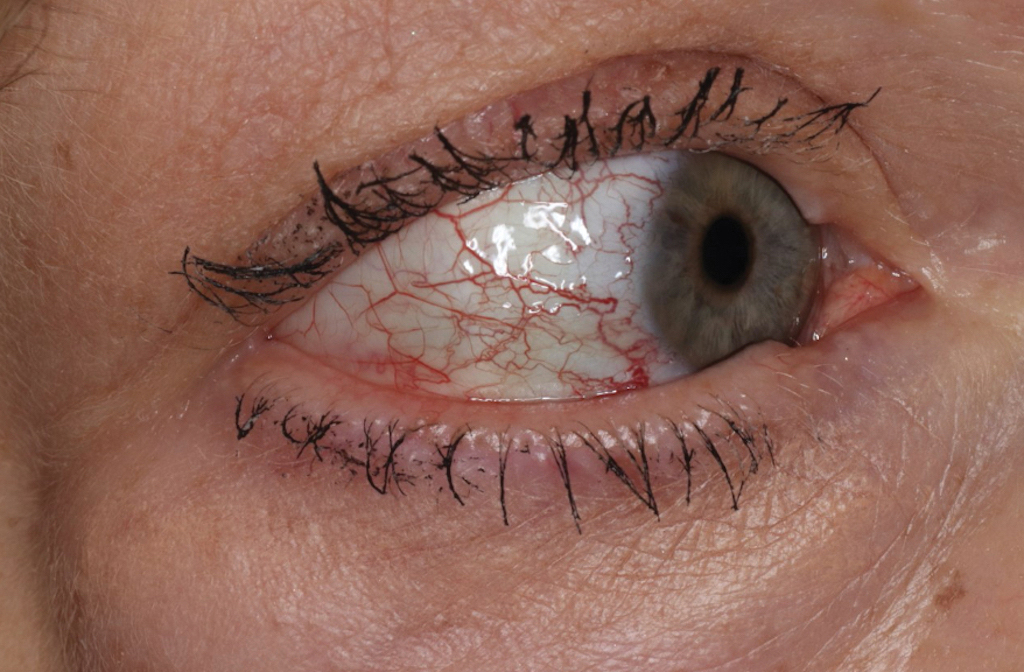

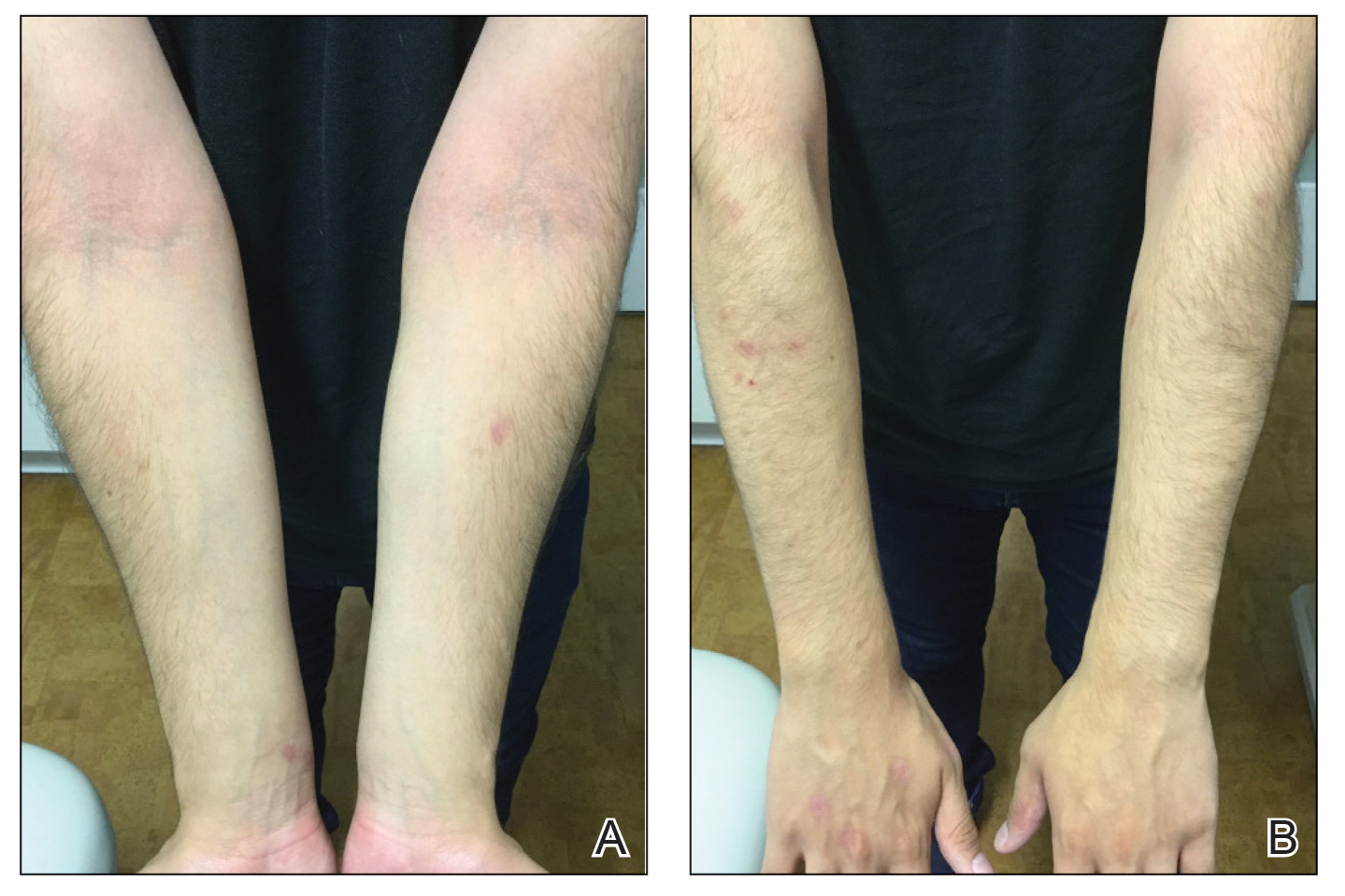

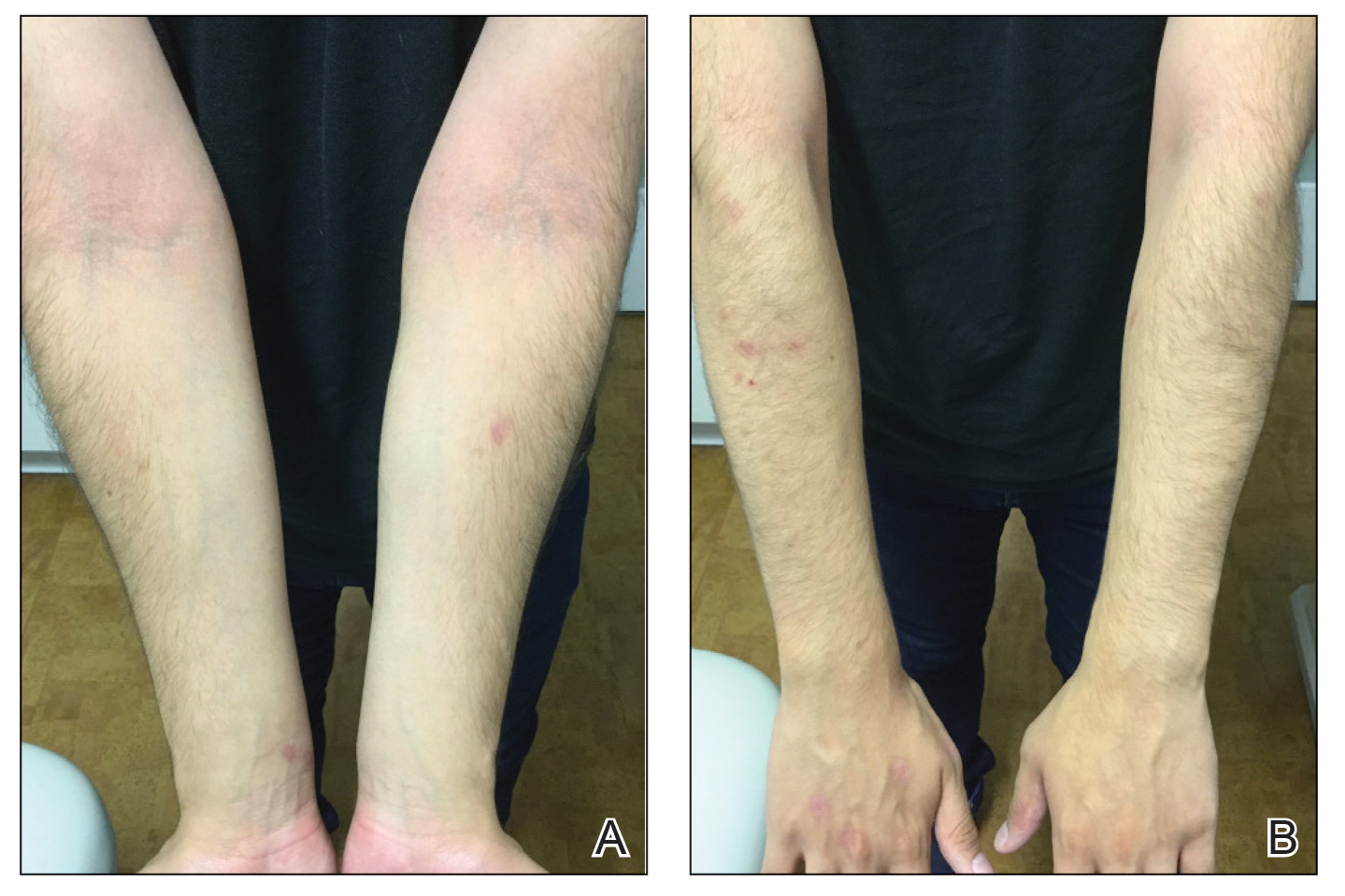

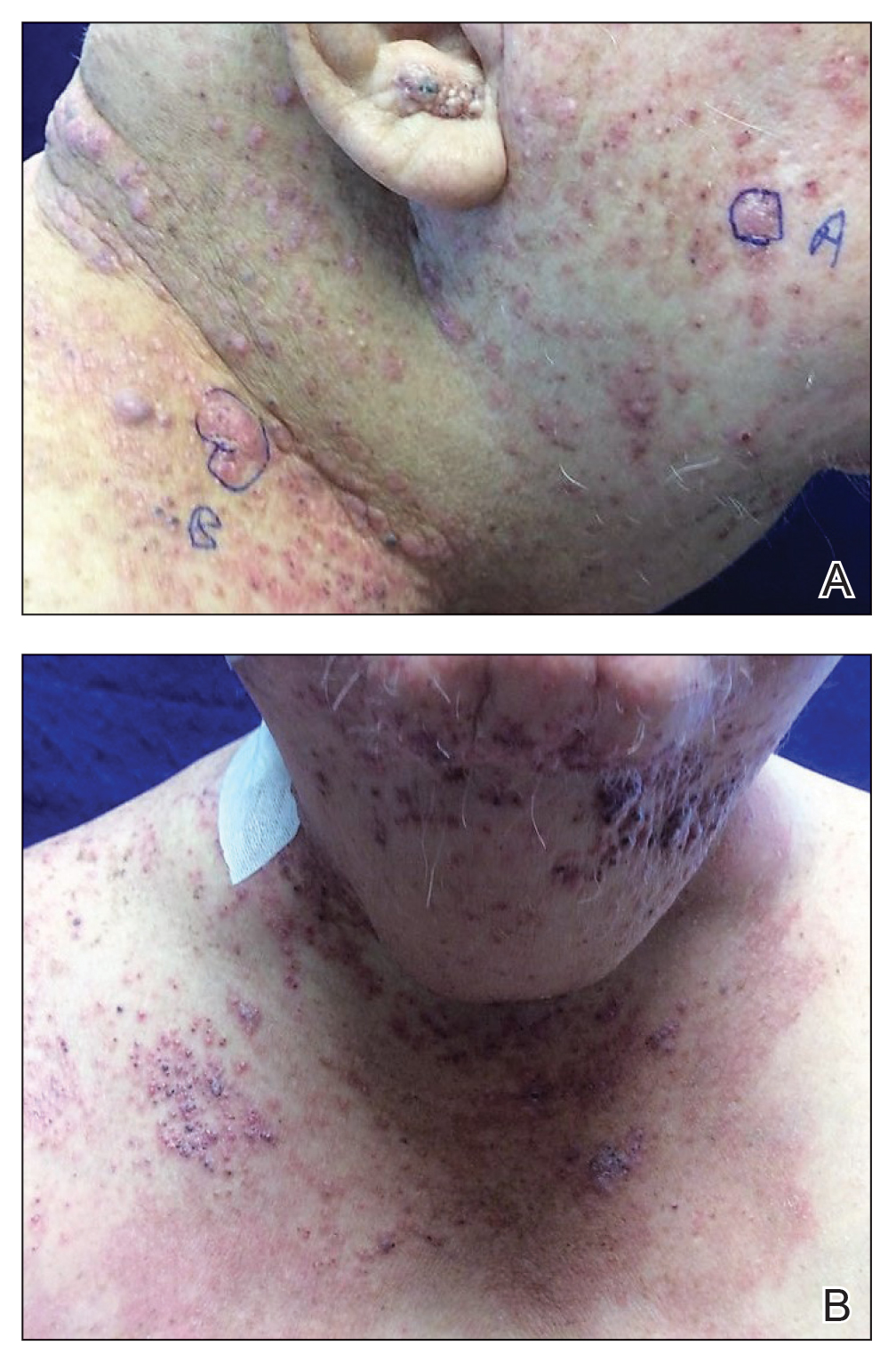

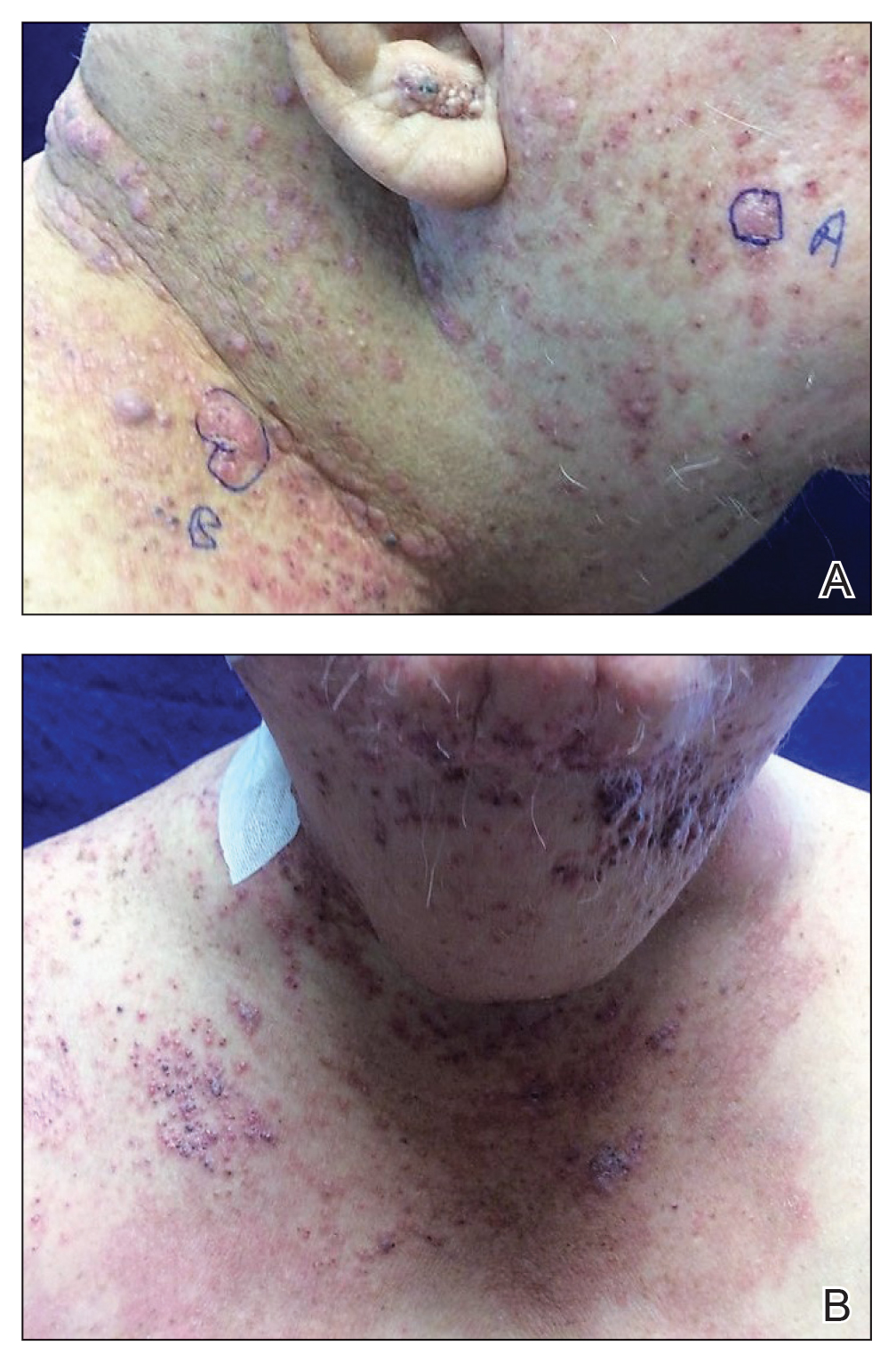

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

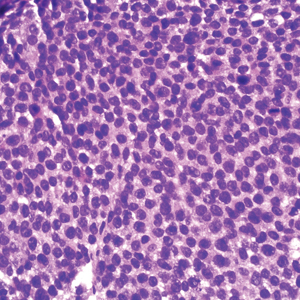

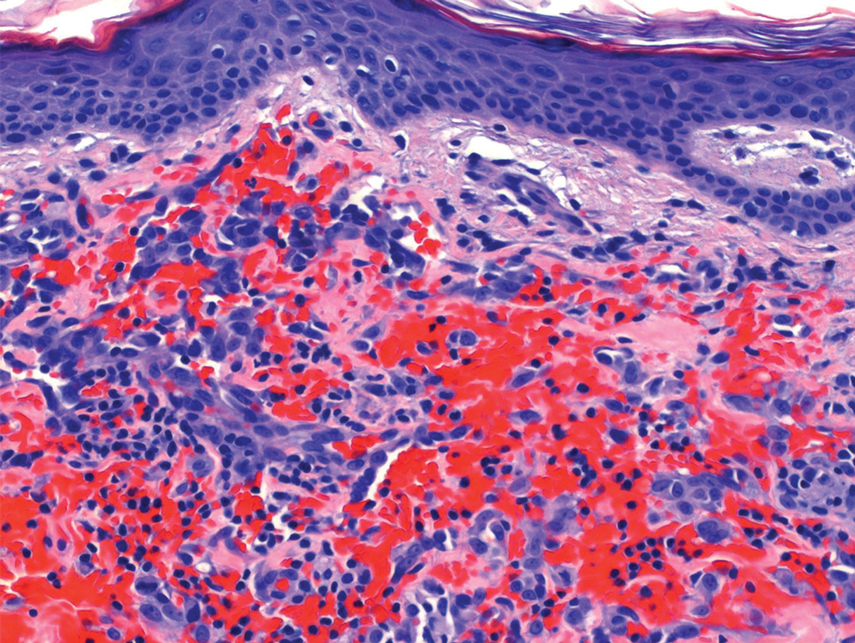

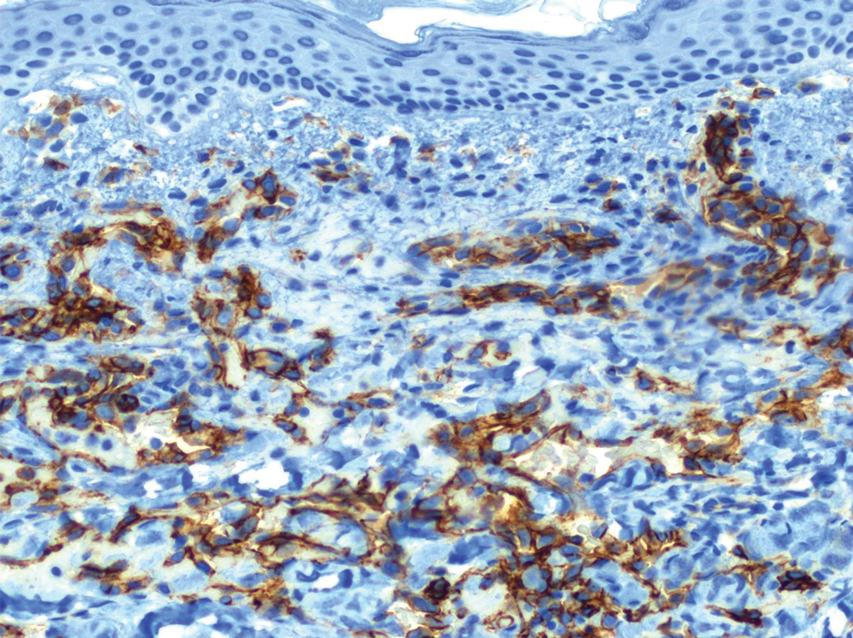

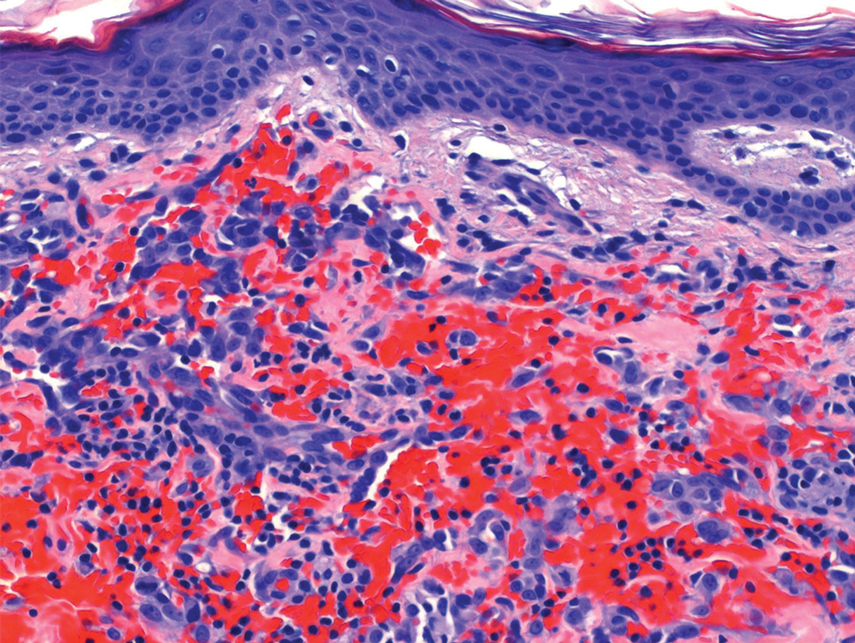

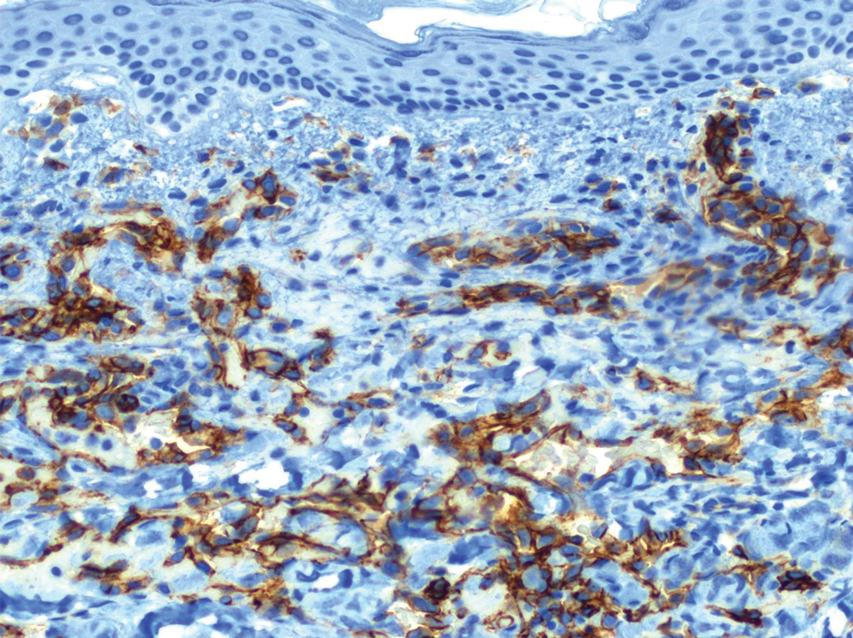

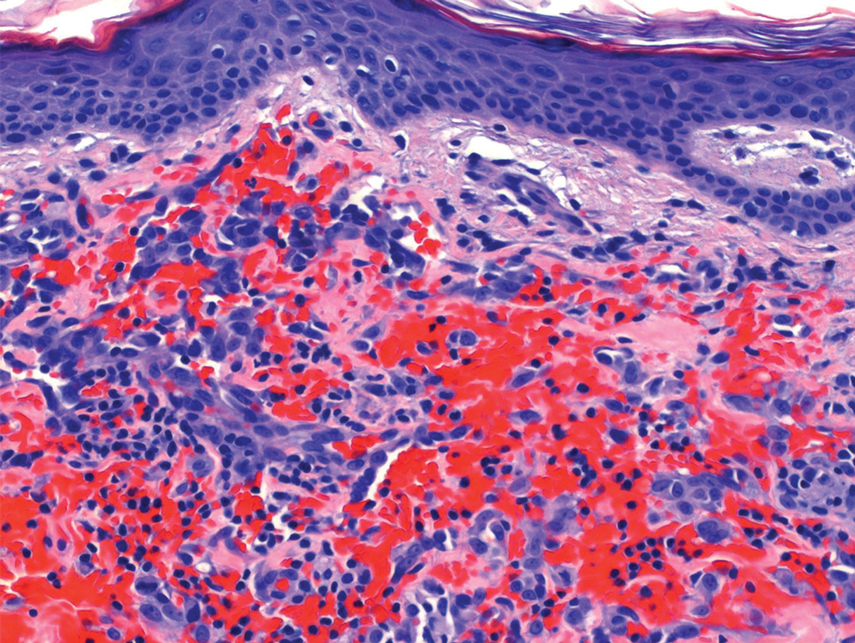

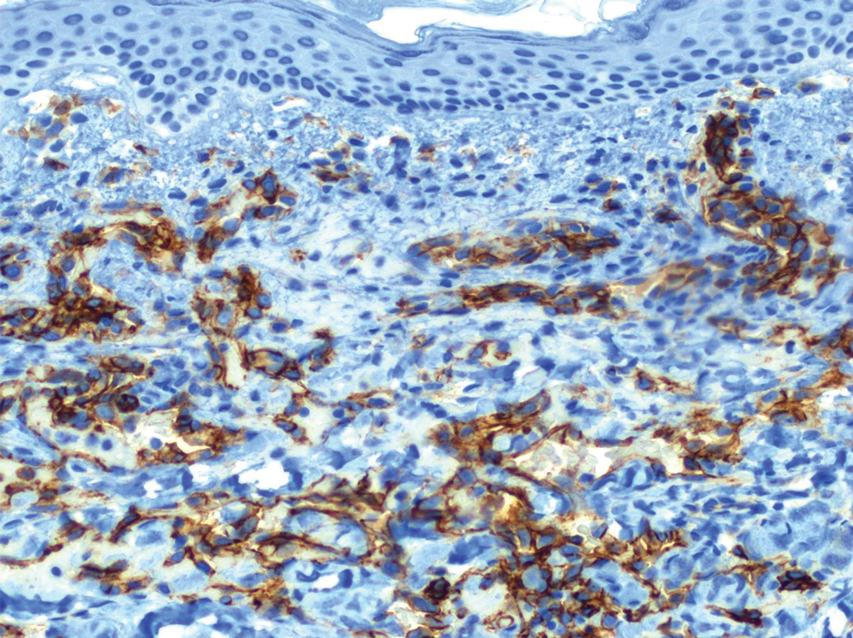

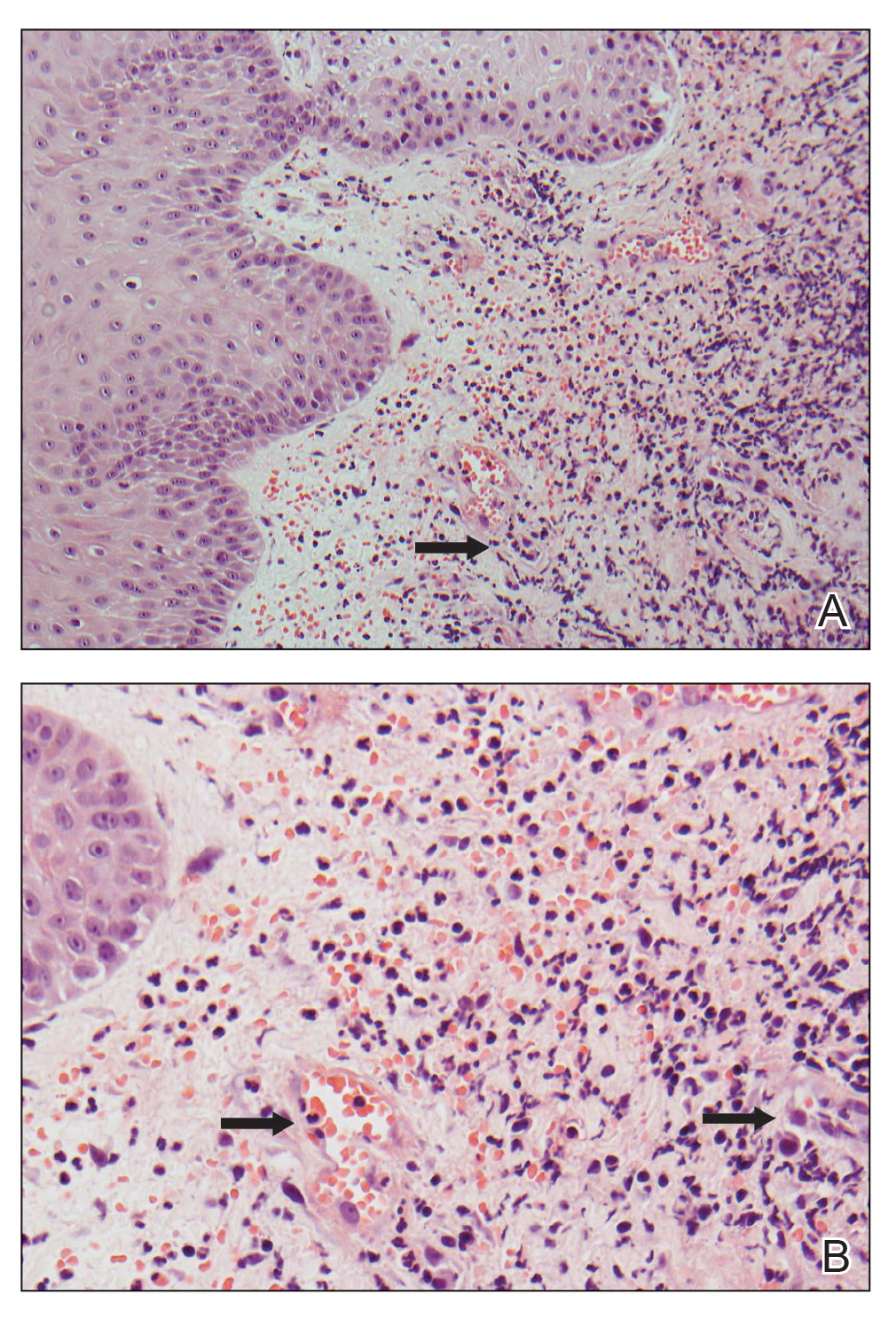

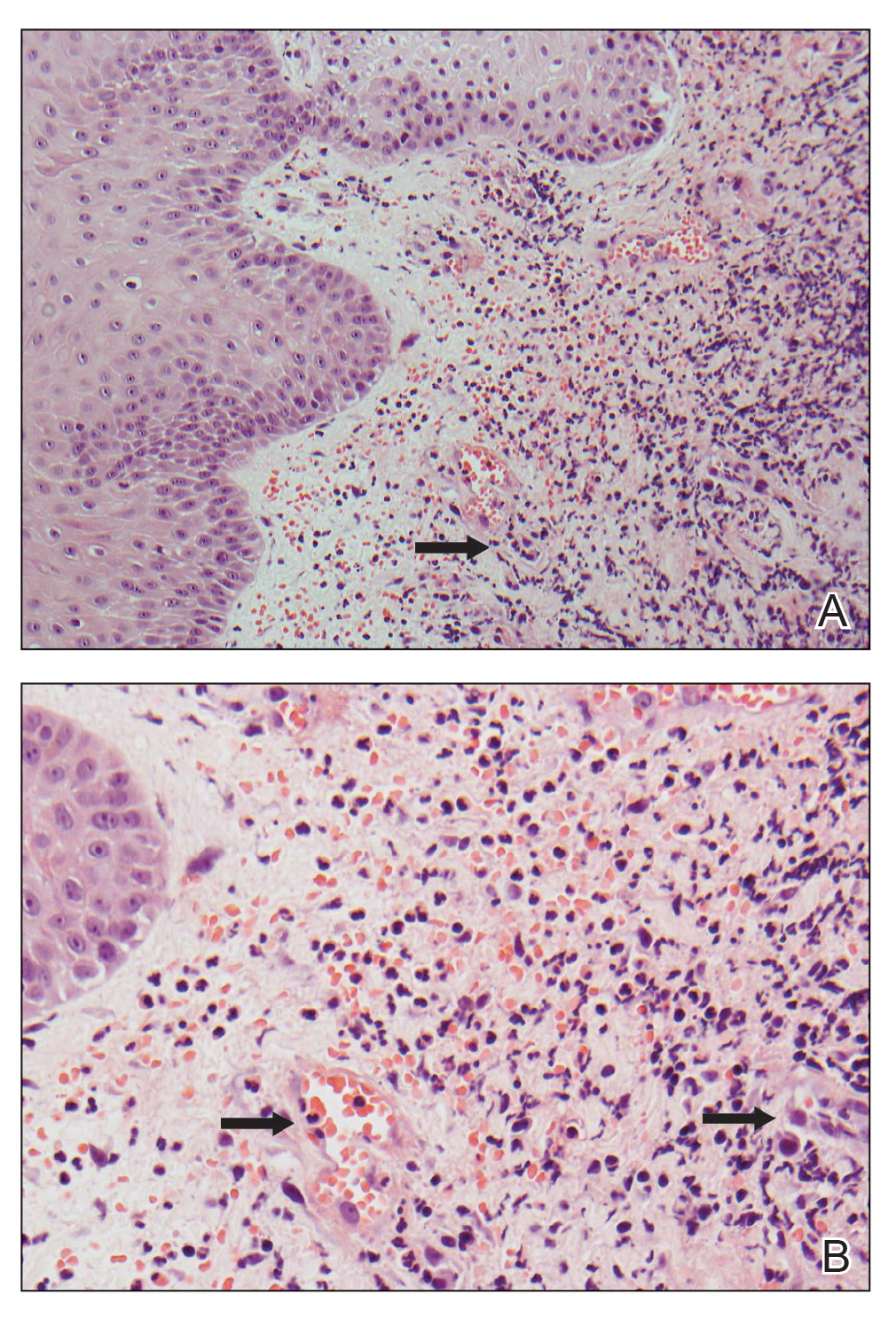

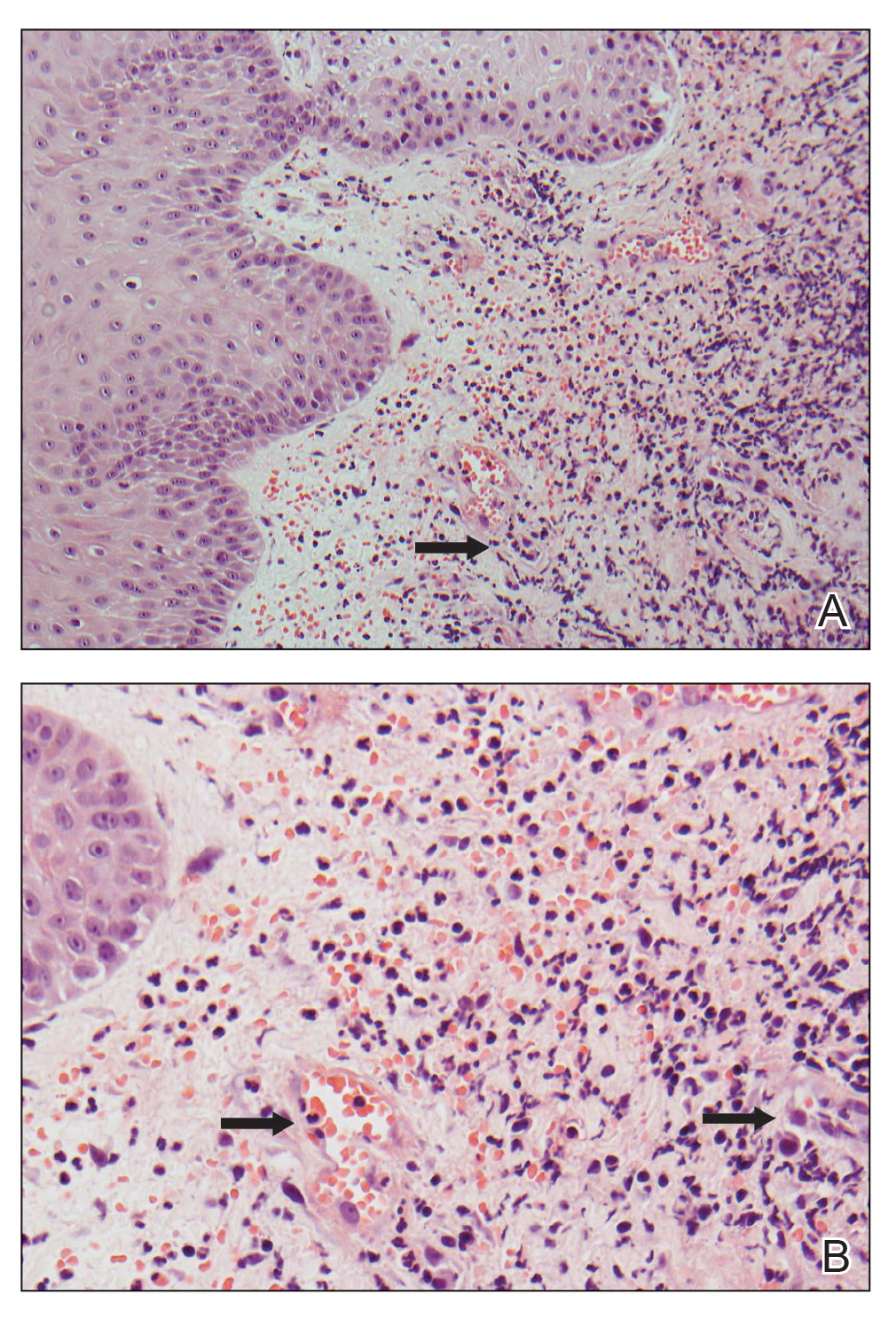

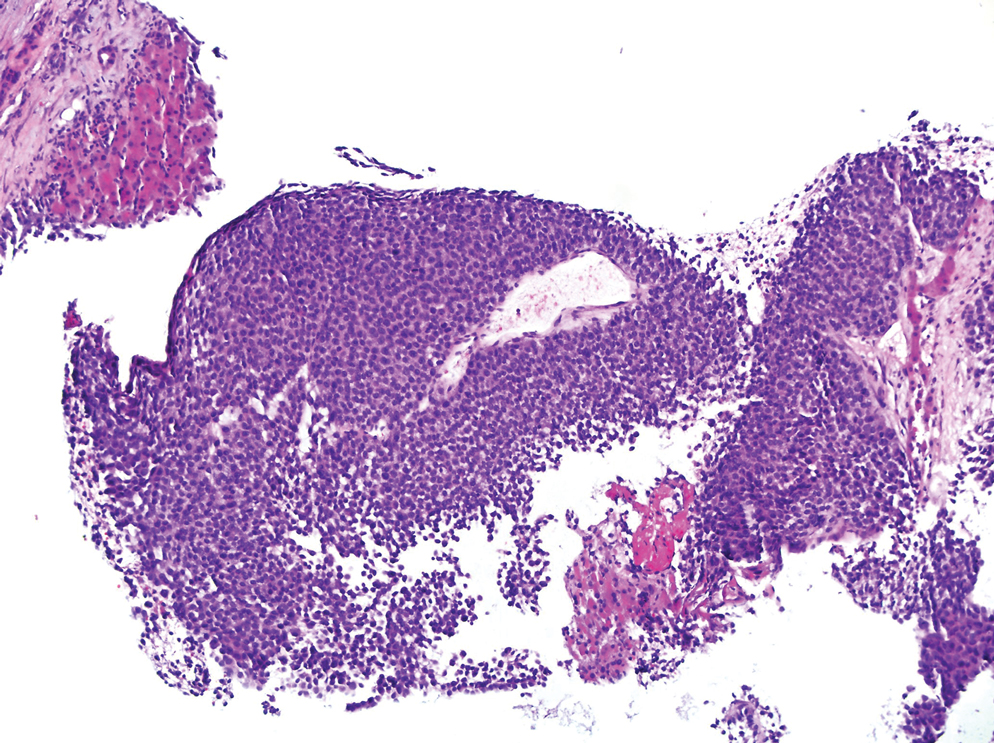

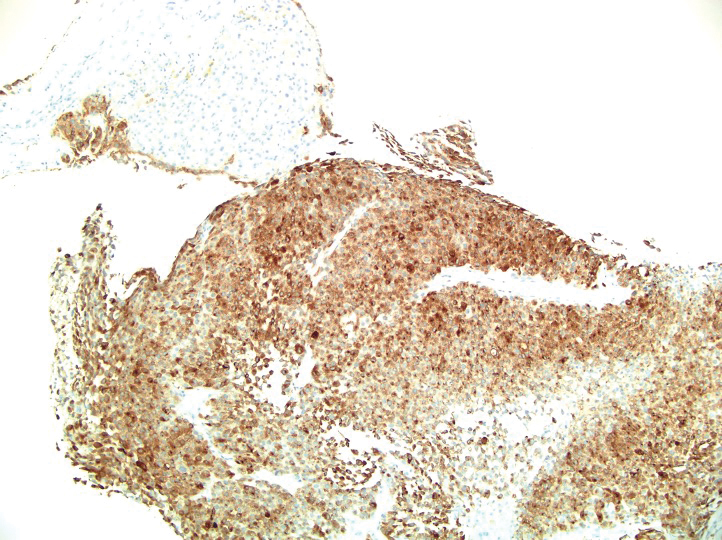

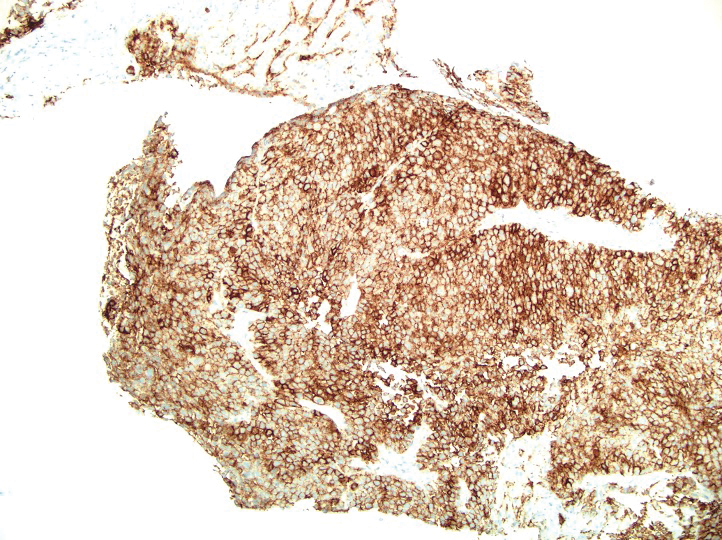

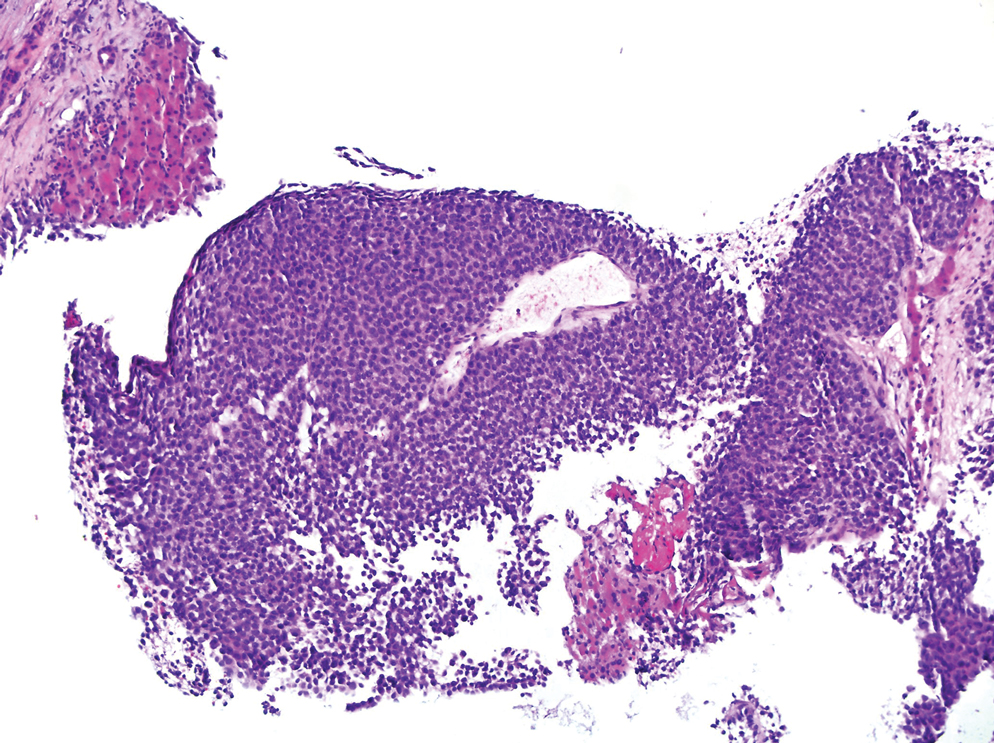

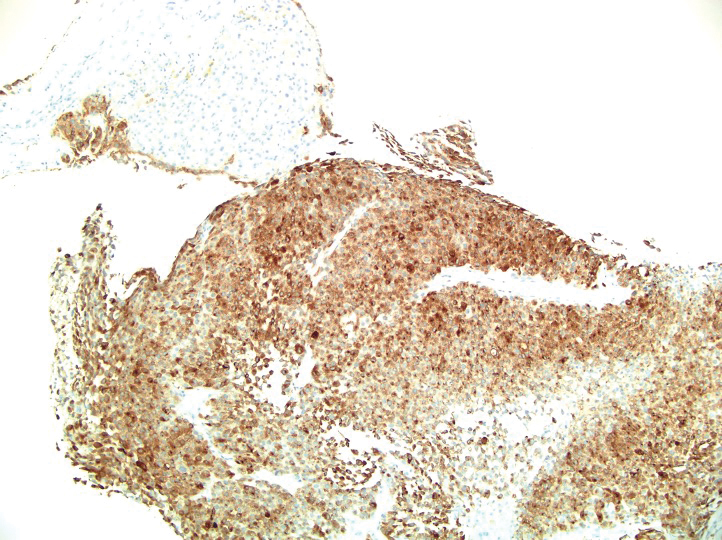

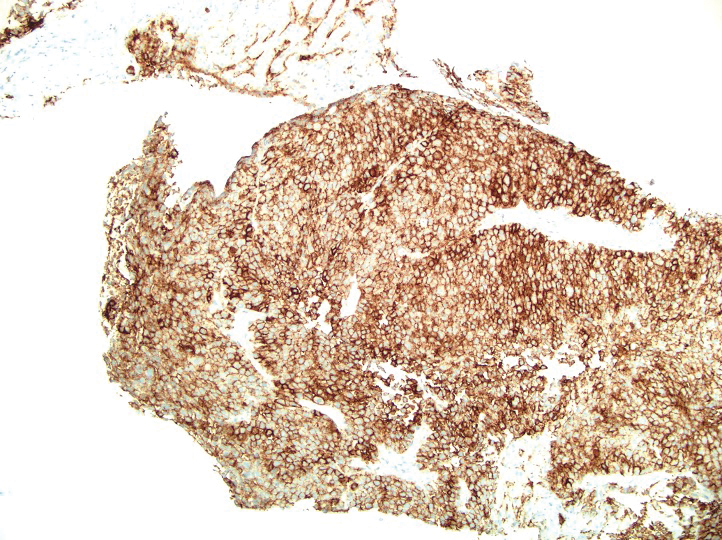

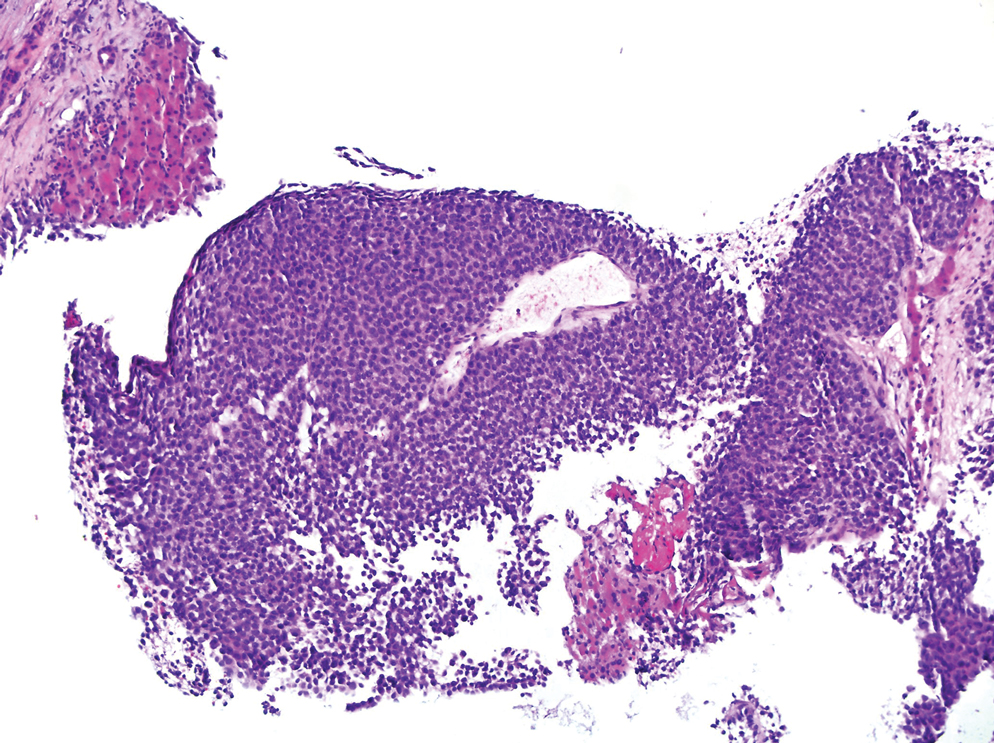

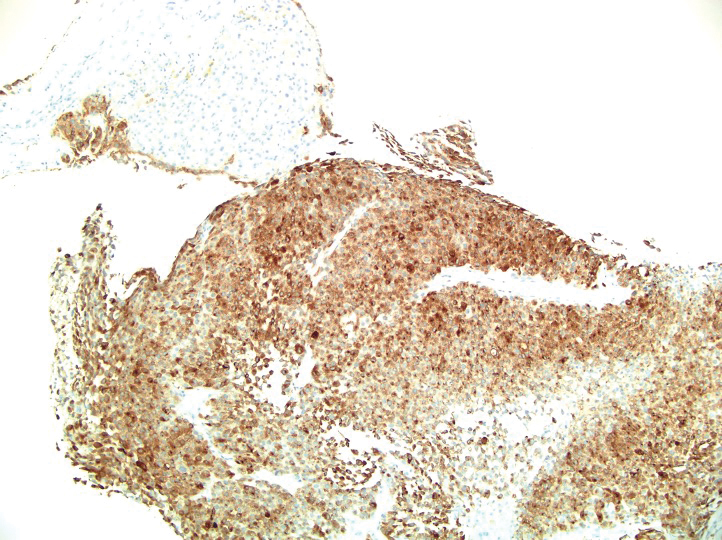

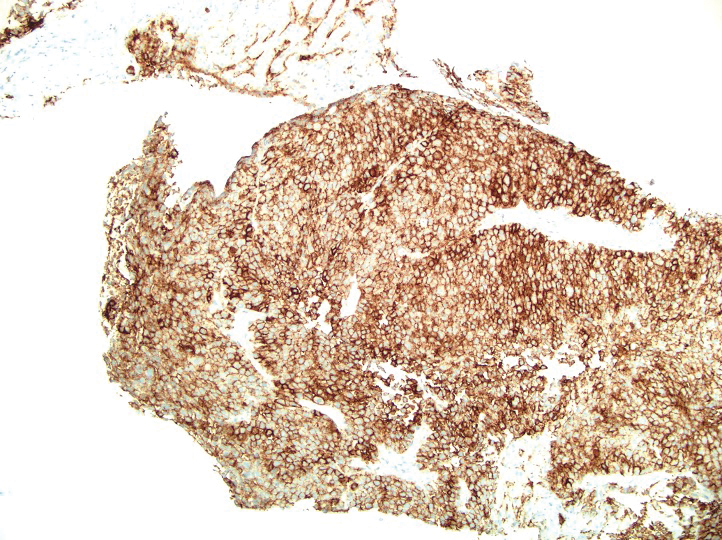

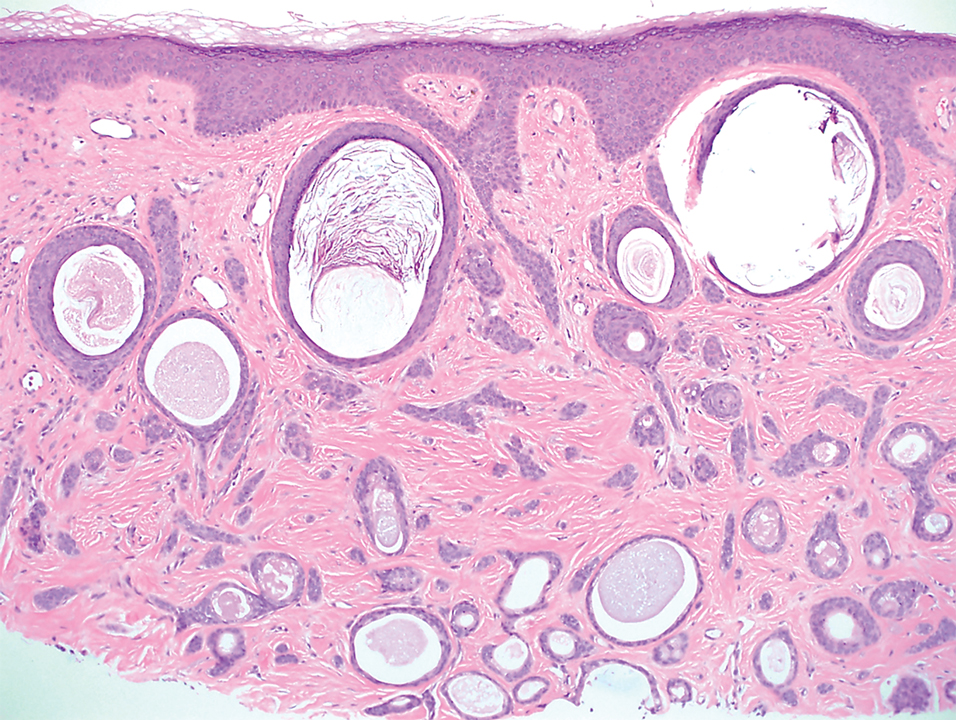

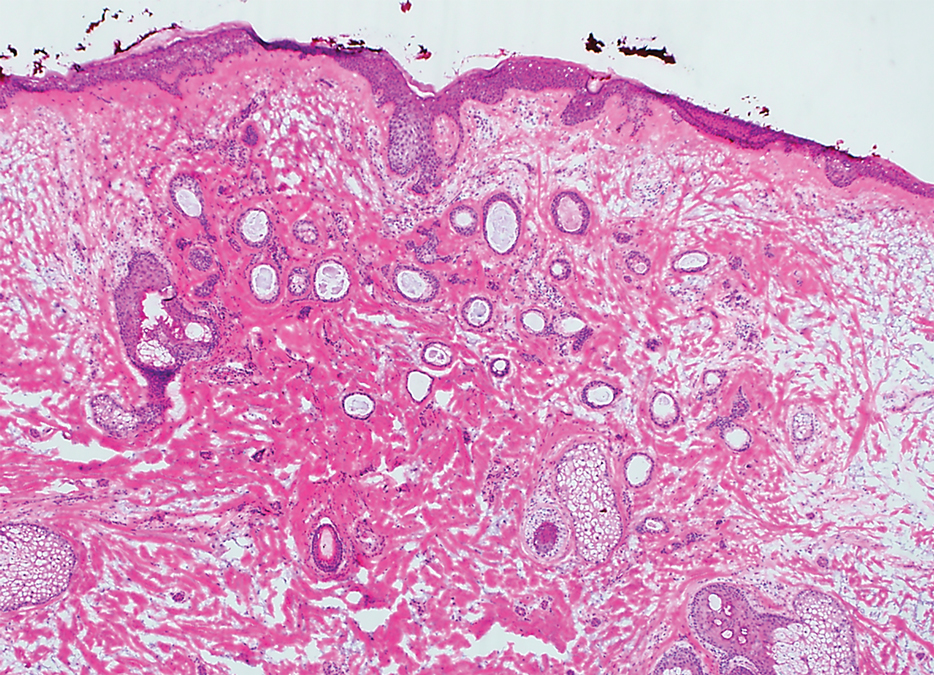

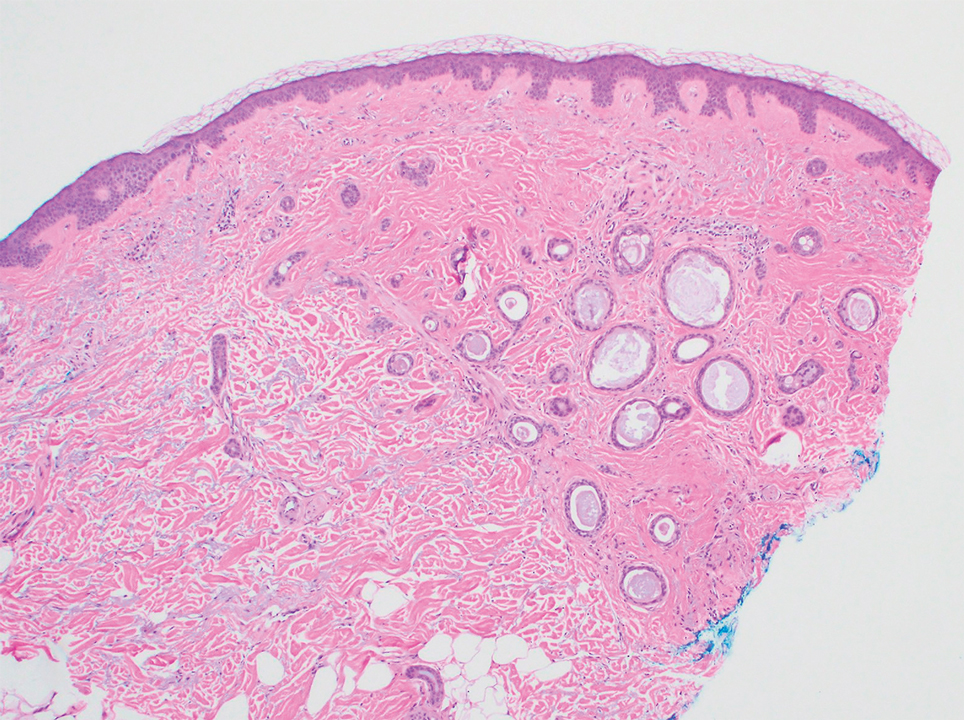

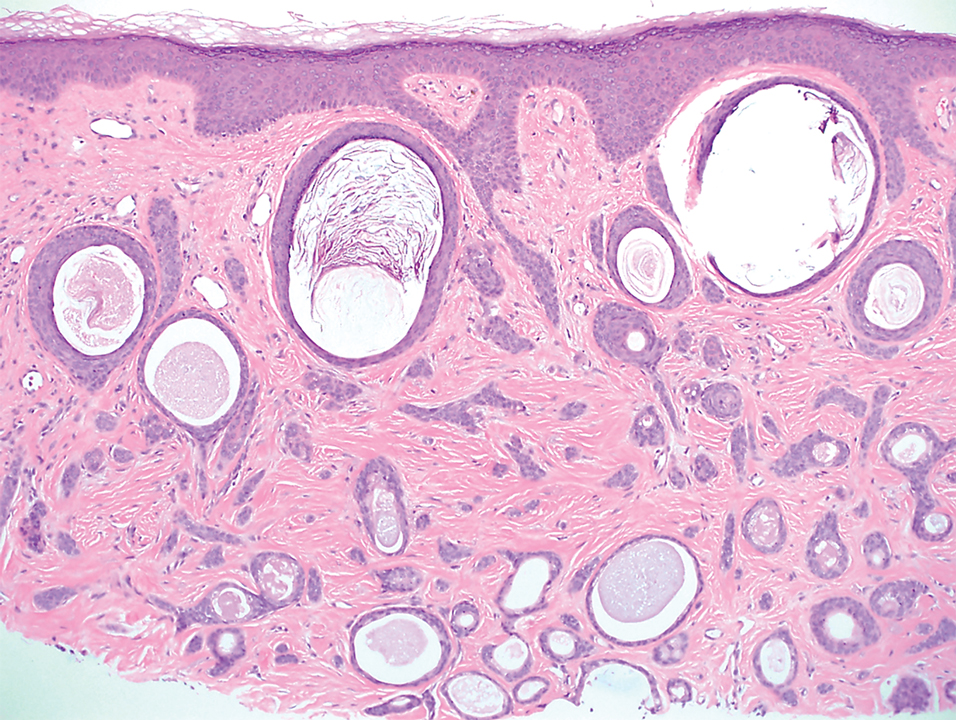

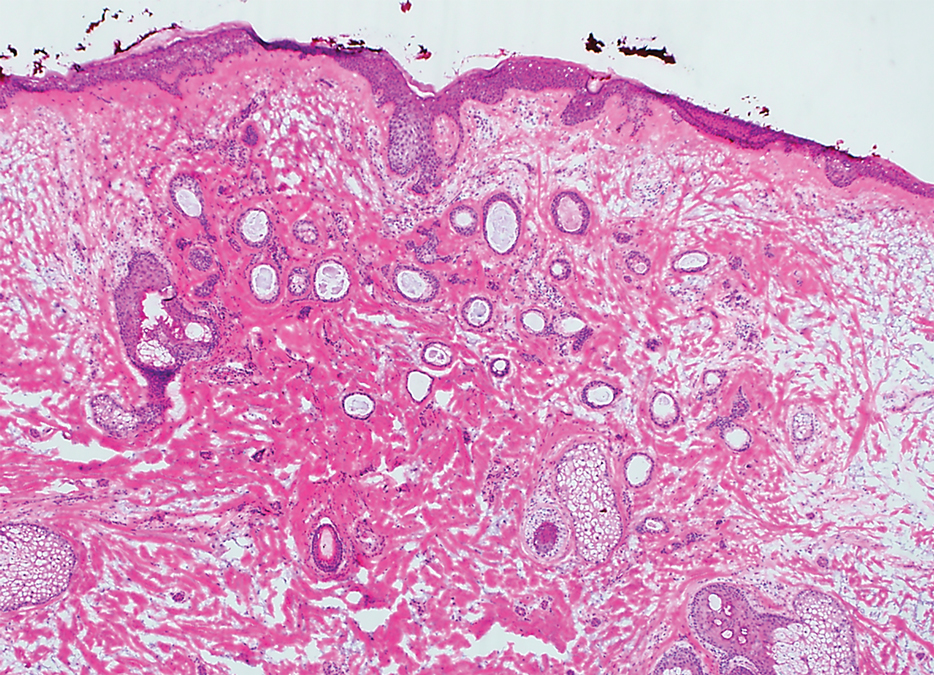

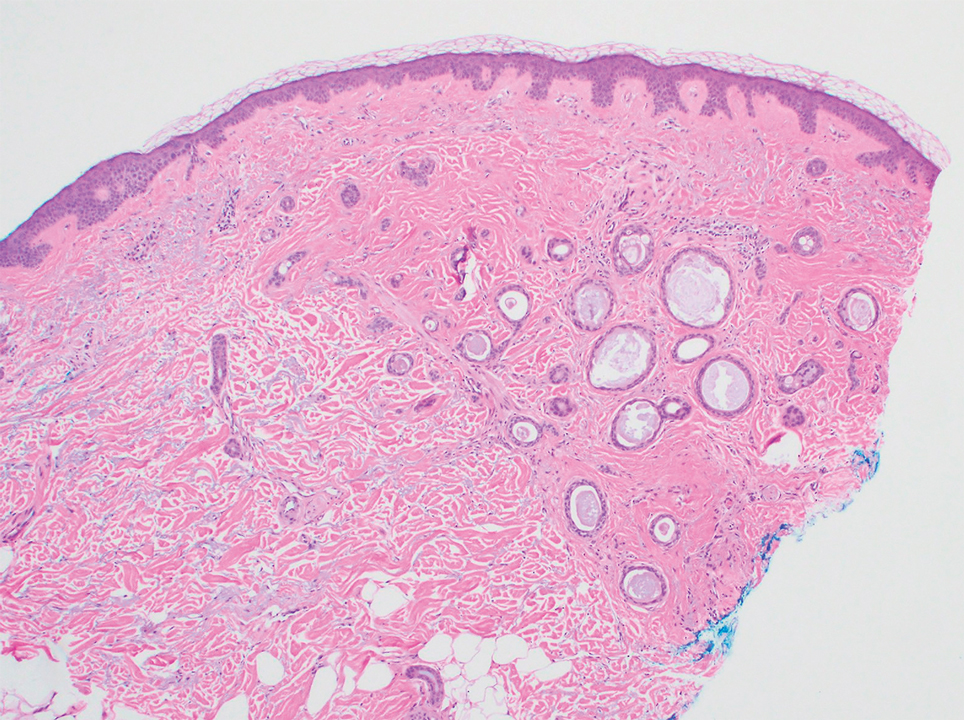

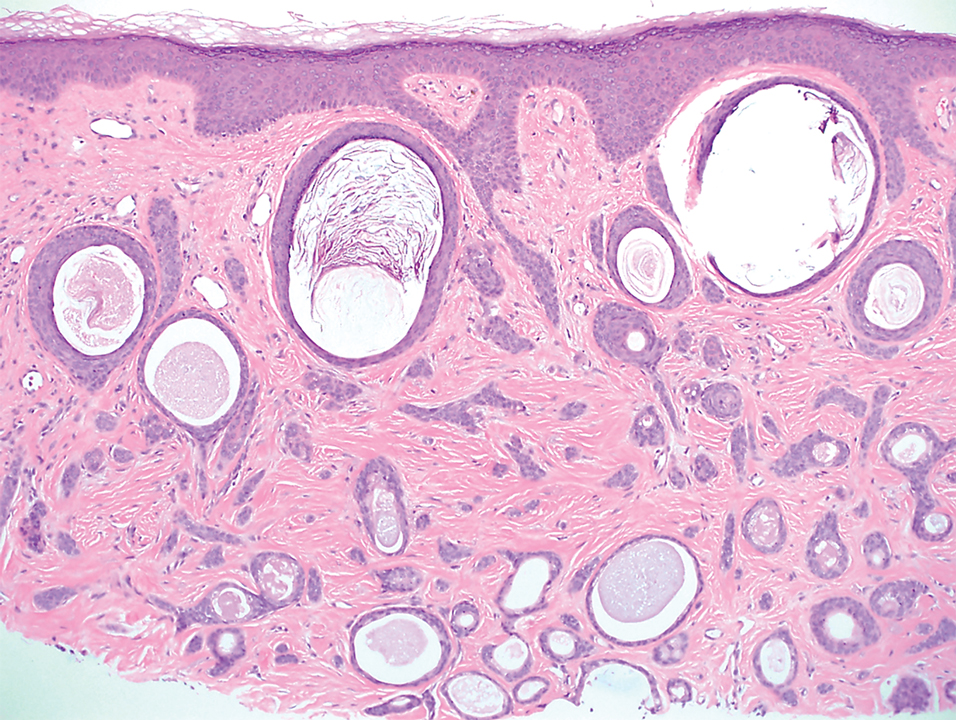

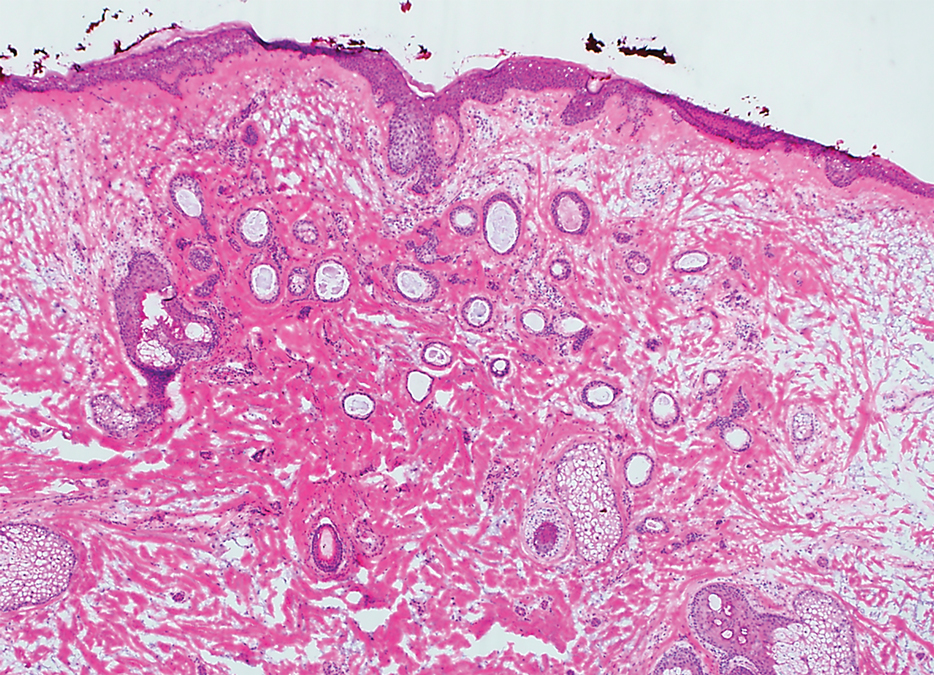

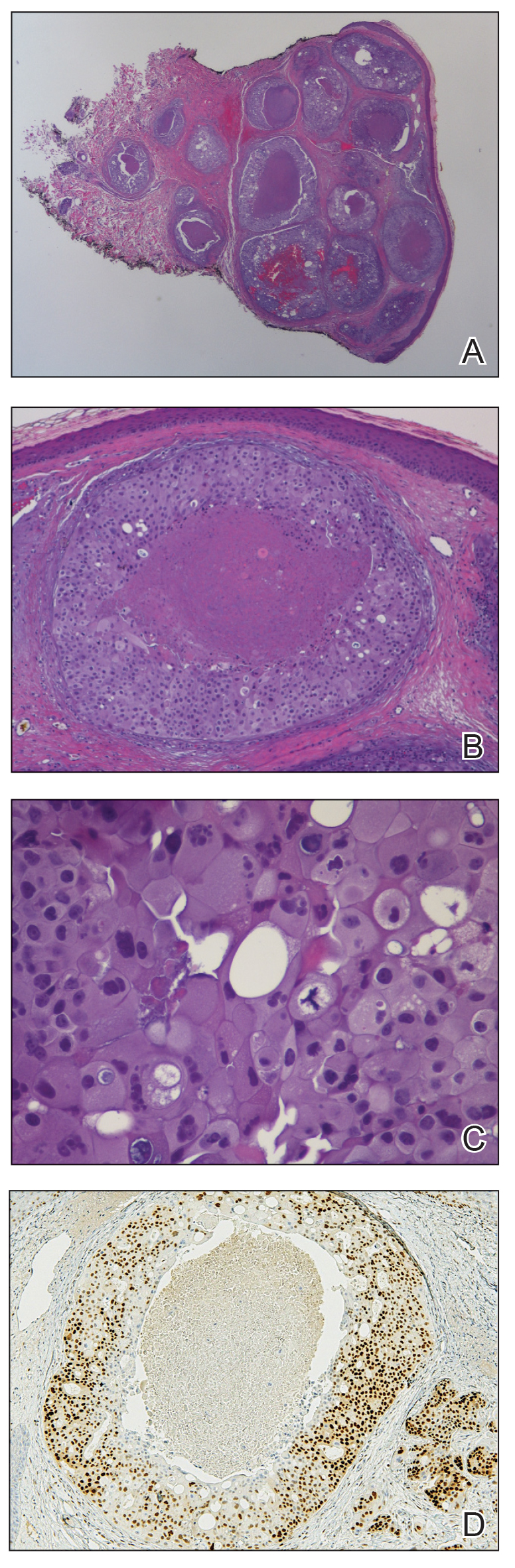

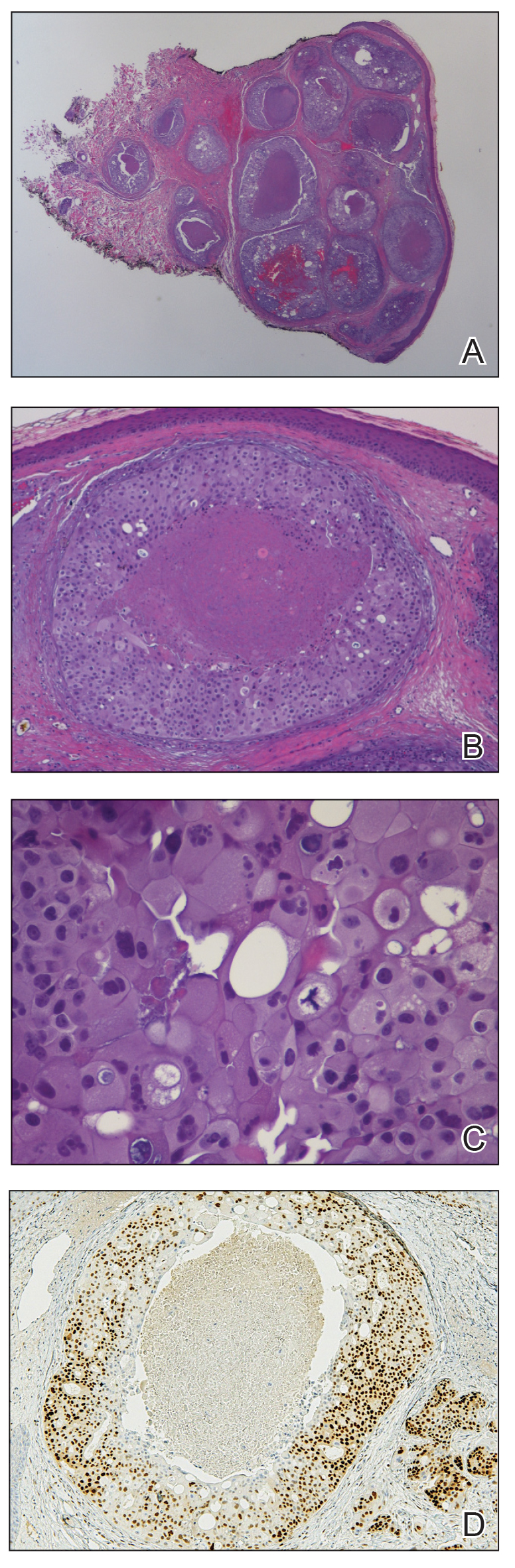

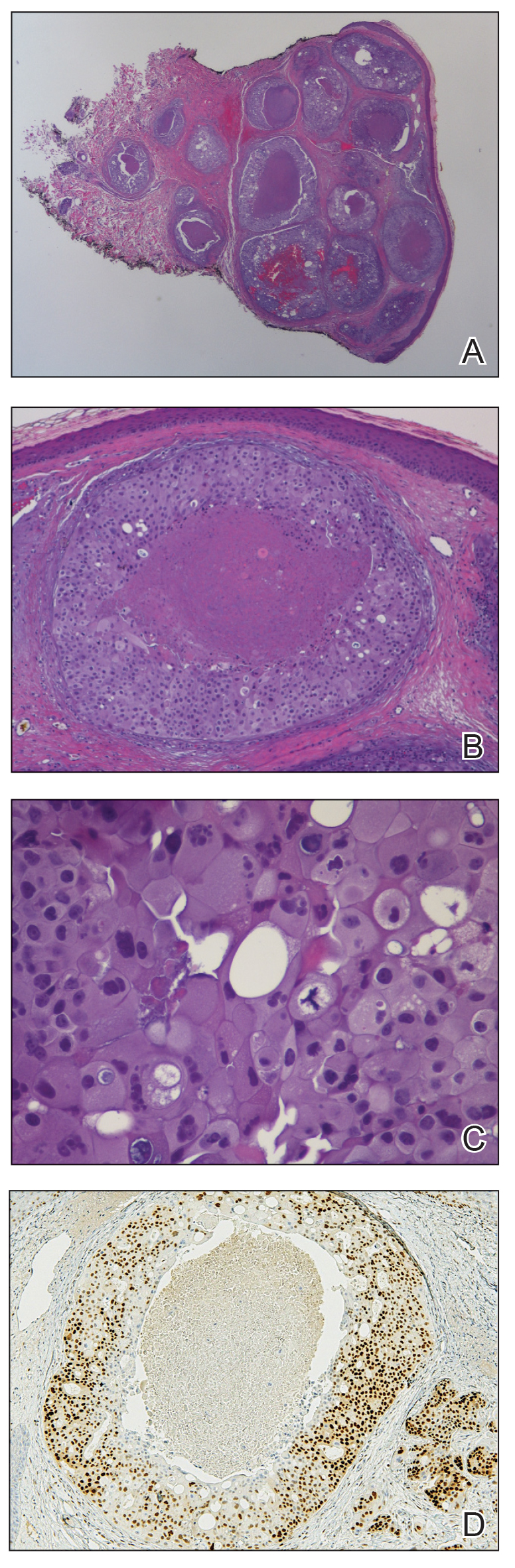

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

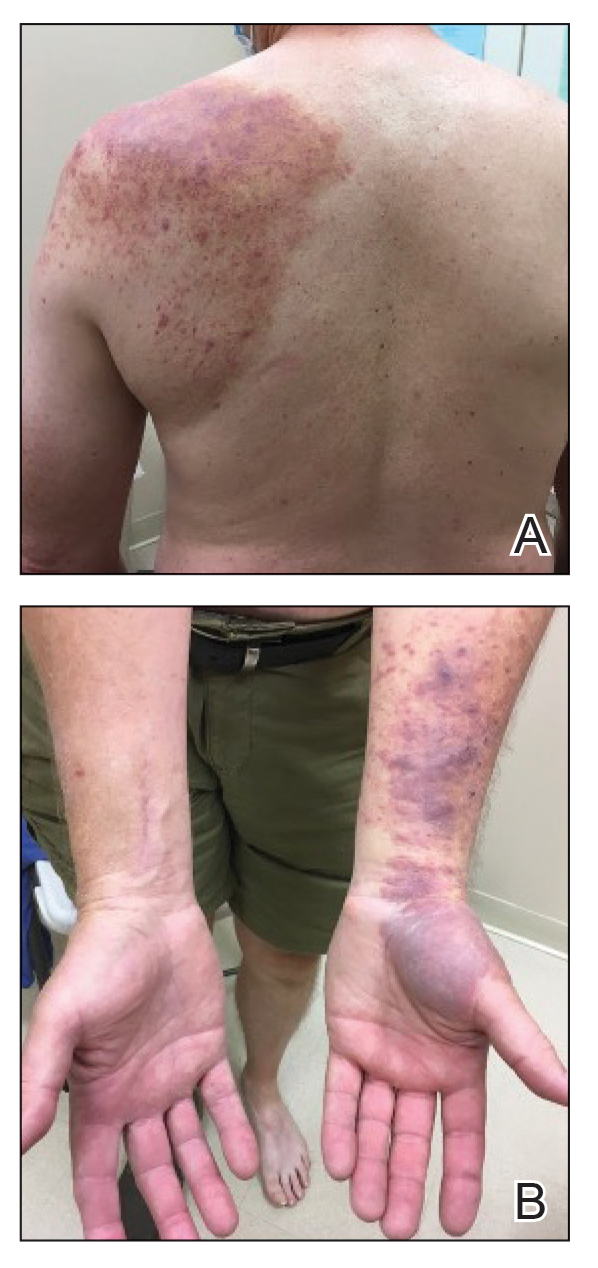

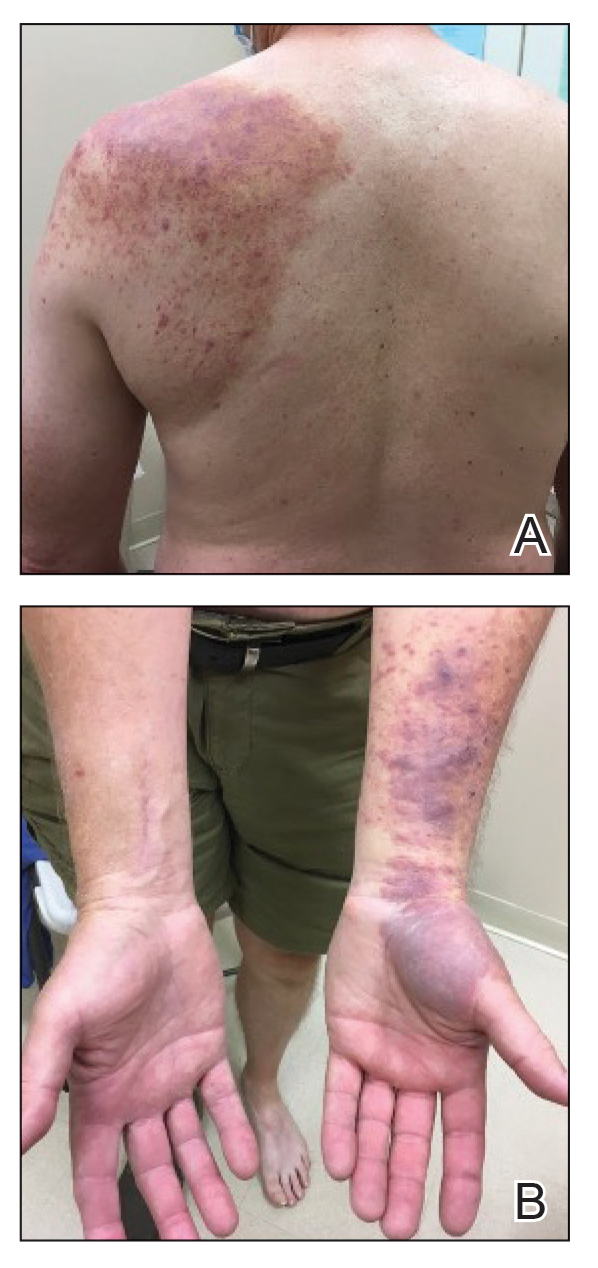

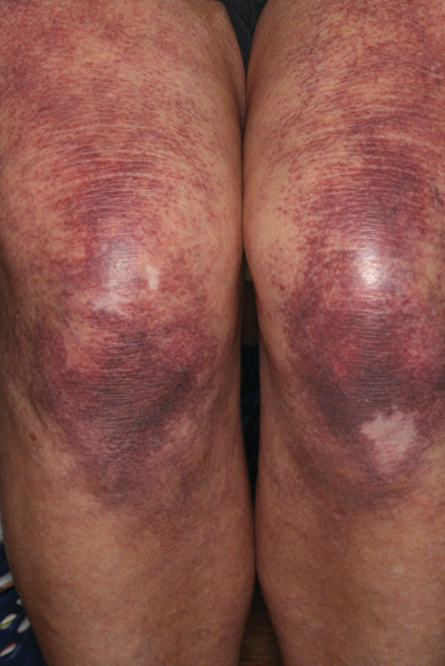

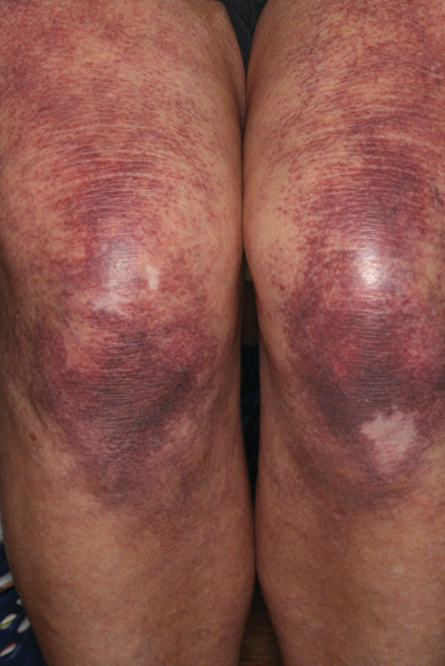

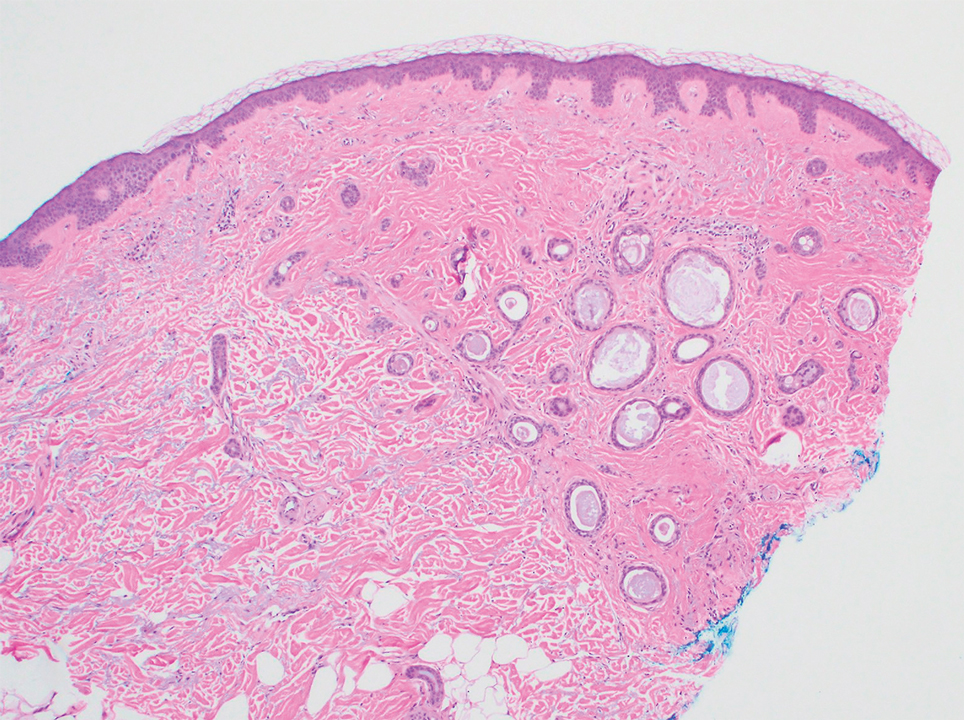

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011

- Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880543

- Genedy RM, Hamza AM, Abdel Latef AA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of D2-40 in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2021;18:67-74. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_61_20

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707-719. doi:10.1038/nrc2888

- Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800061

- Zuckerman JN. The importance of injecting vaccines into muscle. Different patients need different needle sizes. BMJ. 2000;321:1237-1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1237

- Bhatia R, Hazarika N, Chandrasekaran D, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic reactive angioendotheliomatosis with topical timolol maleate. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1002-1004. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1770

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al; ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187-2201. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448-2456. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7517

- Berry CT, Eliliwi M, Gallagher S, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis following single-dose Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;15:11-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.07.002

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:222-235. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012250

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, et al. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;176:16-32. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

- Xiong H-L, Wu Y-T, Cao J-L, et al. Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:2105-2113. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1815589

- Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, et al. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization – apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e722-e725. doi:10.1111/jdv.17499

- Angeli F, Spanevello A, Reboldi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.

Gottron and Nikolowski3 reported the first case of RAE in an adult patient who presented with purpuric patches secondary to skin infarction. Current definitions use the umbrella term cutaneous reactive angiomatosis to cover 3 major subtypes: reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angioendotheliomatosis, and acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma [KS]). The manifestation of these subgroups is clinically similar, and they must be differentiated through histologic evaluation.4

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis has an unknown pathogenesis and is poorly defined clinically. The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely is linked to vaso-occlusion and hypoxia.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as a review of Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library, using the terms reactive angioendotheliomatosis, COVID, vaccine, Ad26.COV2.S, and RAE in any combination revealed no prior cases of RAE in association with Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

By the late 1980s, systemic angioendotheliomatosis was segregated into 2 distinct entities: malignant and reactive.4 The differential diagnosis of malignant systemic angioendotheliomatosis includes KS and angiosarcoma; nonmalignant causes are the variants of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis. It is important to rule out KS because of its malignant and deceptive nature. It is unknown if KS originates in blood vessels or lymphatic endothelial cells; however, evidence is strongly in favor of blood vessel origin using CD31 and CD34 endothelial markers.5 CD34 positivity is more reliable than CD31 in diagnosing KS, but the absence of both markers does not offer enough evidence to rule out KS on its own.6

In our patient, histopathology revealed cells positive for CD31 and D2-40; the latter is a lymphatic endothelial cell marker that stains the endothelium of lymphatic channels but not blood vessels.7 Positive D2-40 can be indicative of KS and non-KS lesions, each with a distinct staining pattern. D2-40 staining on non-KS lesions is confined to lymphatic vessels, as it was in our patient; in contrast, spindle-shaped cells also will be stained in KS lesions.8

Another cell marker, CD20, is a B cell–specific protein that can be measured to help diagnose malignant diseases such as B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Human herpesvirus 8 (also known as KS-associated herpesvirus) is the infectious cause of KS and traditionally has been detected using methods such as the polymerase chain reaction.9,10

Most cases of RAE are idiopathic and occur in association with systemic disease, which was not the case in our patient. We speculated that his reaction was most likely triggered by vascular transfection of endothelial cells secondary to Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. Alternatively, vaccination may have caused vascular occlusion, though the lack of cyanosis, nail changes, and route of inoculant make this less likely.

All approved COVID-19 vaccines are designed solely for intramuscular injection. In comparison to other types of tissue, muscles have superior vascularity, allowing for enhanced mobilization of compounds, which results in faster systemic circulation.11 Alternative methods of injection, including intravascular, subcutaneous, and intradermal, may lead to decreased efficacy or adverse events, or both.

Prior cases of RAE have been treated with laser therapy, topical or systemic corticosteroids, excisional removal, or topical β-blockers, such as timolol.12β-Blocking agents act on β-adrenergic receptors on endothelial cells to inhibit angiogenesis by reducing release of blood vessel growth-signaling molecules and triggering apoptosis. In this patient, topical steroids and oral antihistamines were sufficient treatment.

Vaccine-related adverse events have been reported but remain rare. The benefits of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination for protection against COVID-19 outweigh the extremely low risk for adverse events.13 For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals who are eligible to maximize protection. Intramuscular injection of Ad26.COV2.S resulted in a lower incidence of moderate to severe COVID-19 cases in all age groups vs the placebo group. Hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in 0.4% of Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated patients vs 0.4% of patients who received a placebo; the more common reactions were nonanaphylactic.13

There have been 12 reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, which sparked nationwide controversy over the safety of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine.14 After further investigation into those reports, the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that the benefits of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine outweigh the low risk for associated thrombosis.15

Although adverse reactions are rare, it is important that health care providers take proper safety measures before and while administering any COVID-19 vaccine. Patients should be screened for contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine to mitigate adverse effects seen in the small percentage of patients who may need to take alternative precautions.

The broad tissue tropism and high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 are the main contributors to its infection having reached pandemic scale. The spike (S) protein on SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, the most thoroughly studied SARS-CoV-2 receptor, which is found in a range of tissues, including arterial endothelial cells, leading to its transfection. Several studies have proposed that expression of the S protein causes endothelial dysfunction through cytokine release, activation of complement, and ultimately microvascular occlusion.16

Recent developments in the use of viral-like particles, such as vesicular stomatitis virus, may mitigate future cases of RAE that are associated with endothelial cell transfection. Vesicular stomatitis virus is a popular model virus for research applications due to its glycoprotein and matrix protein contributing to its broad tropism. Recent efforts to alter these proteins have successfully limited the broad tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus.17

The SARS-CoV-2 virus must be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 laboratory. Conversely, pseudoviruses can be handled in lower containment facilities due to their safe and efficacious nature, offering an avenue to expedite vaccine development against many viral outbreaks, including SARS-CoV-2.18

An increasing number of cutaneous manifestations have been associated with COVID-19 infection and vaccination. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, a rare self-limiting exanthem, has been reported in association with COVID-19 vaccination.19 Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis manifests as erythematous blanchable papules that resemble angiomas, typically in a widespread distribution. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis has striking similarities to RAE histologically; both manifest as dilated dermal blood vessels with plump endothelial cells.

Our case is unique because of the vasculitic palpable nature of the lesions, which were localized to the left arm. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis formation after COVID-19 infection or SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may suggest alteration of ACE2 by binding of S protein.20 Such alteration of the ACE2 pathway would lead to inflammation of angiotensin II, causing proliferation of endothelial cells in the formation of angiomalike lesions. This hypothesis suggests a paraviral eruption secondary to an immunologic reaction, not a classical virtual eruption from direct contact of the virus on blood vessels. Although EPA and RAE are harmless and self-limiting, these reports will spread awareness of the increasing number of skin manifestations related to COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccination.

Acknowledgment—Thoughtful insights and comments on this manuscript were provided by Christine J. Ko, MD (New Haven, Connecticut); Christine L. Egan, MD (Glen Mills, Pennsylvania); Howard A. Bueller, MD (Delray Beach, Florida); and Juan Pablo Robles, PhD (Juriquilla, Mexico).

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011

- Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880543

- Genedy RM, Hamza AM, Abdel Latef AA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of D2-40 in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2021;18:67-74. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_61_20

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707-719. doi:10.1038/nrc2888

- Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800061

- Zuckerman JN. The importance of injecting vaccines into muscle. Different patients need different needle sizes. BMJ. 2000;321:1237-1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1237

- Bhatia R, Hazarika N, Chandrasekaran D, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic reactive angioendotheliomatosis with topical timolol maleate. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1002-1004. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1770

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al; ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187-2201. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448-2456. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7517

- Berry CT, Eliliwi M, Gallagher S, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis following single-dose Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;15:11-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.07.002

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:222-235. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012250

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, et al. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;176:16-32. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

- Xiong H-L, Wu Y-T, Cao J-L, et al. Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:2105-2113. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1815589

- Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, et al. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization – apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e722-e725. doi:10.1111/jdv.17499

- Angeli F, Spanevello A, Reboldi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019

- McMenamin ME, Fletcher CDM. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: a study of 15 cases demonstrating a wide clinicopathologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:686-697. doi:10.1097/00000478-200206000-00001

- Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, et al. Angiomatosis: a rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108-110. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.158448

- Gottron HA, Nikolowski W. Extrarenal Lohlein focal nephritis of the skin in endocarditis. Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1958;207:156-176.

- Cooper PH. Angioendotheliomatosis: two separate diseases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:259. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00556.x

- Cancian L, Hansen A, Boshoff C. Cellular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. Sep 2013;23:421-32. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.04.001

- Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, et al. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. doi:10.1136/jcp.48.11.1011

- Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880543

- Genedy RM, Hamza AM, Abdel Latef AA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of D2-40 in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2021;18:67-74. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_61_20

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707-719. doi:10.1038/nrc2888

- Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800061

- Zuckerman JN. The importance of injecting vaccines into muscle. Different patients need different needle sizes. BMJ. 2000;321:1237-1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1237

- Bhatia R, Hazarika N, Chandrasekaran D, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic reactive angioendotheliomatosis with topical timolol maleate. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1002-1004. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1770

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al; ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187-2201. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448-2456. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7517

- Berry CT, Eliliwi M, Gallagher S, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis following single-dose Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;15:11-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.07.002

- Flaumenhaft R, Enjyoji K, Schmaier AA. Vasculopathy in COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:222-235. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012250

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, et al. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;176:16-32. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.003

- Xiong H-L, Wu Y-T, Cao J-L, et al. Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:2105-2113. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1815589

- Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, et al. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization – apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e722-e725. doi:10.1111/jdv.17499

- Angeli F, Spanevello A, Reboldi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019

Practice points

- Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare benign vascular proliferation of endothelial cells lining blood vessels that clinically appears similar to Kaposi sarcoma and must be differentiated by microscopic evaluation.

- An increasing number of reports link SARS-CoV-2 viral infection or vaccination against this virus with various cutaneous manifestations. Our case offers a link between RAE and Ad26.COV2.S vaccination.

Diffuse Capillary Malformation With Undergrowth of a Limb in a Boy

To the Editor:

Capillary malformations (CMs), the most common vascular malformations that can affect the skin,1 present clinically as macules and patches of various colors, shapes, and sizes. Congenital structural abnormalities are associated with conditions such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC), and megalencephaly–capillary malformation syndrome.2 Diffuse CM with overgrowth (DCMO) of the soft tissue and bones is an established association of CMs; however, diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth (DCMU) is a more recent term that describes the lesser-recognized counterpart to DCMO.3 Herein, we describe a case of CM with left-sided undergrowth.

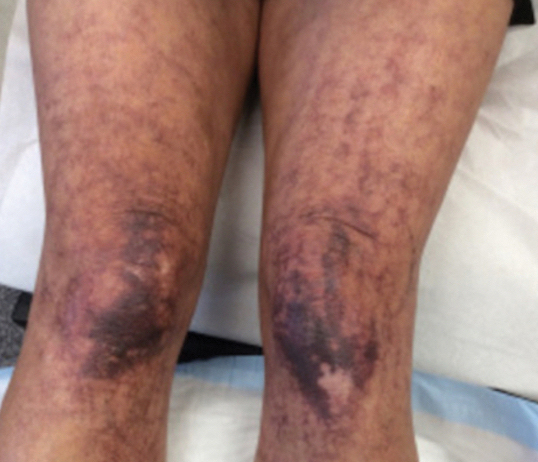

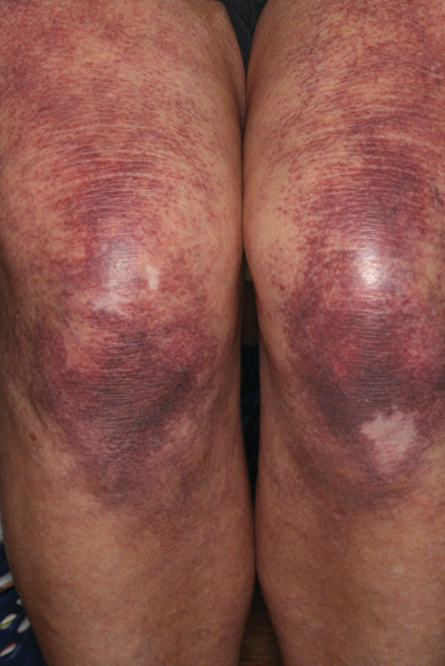

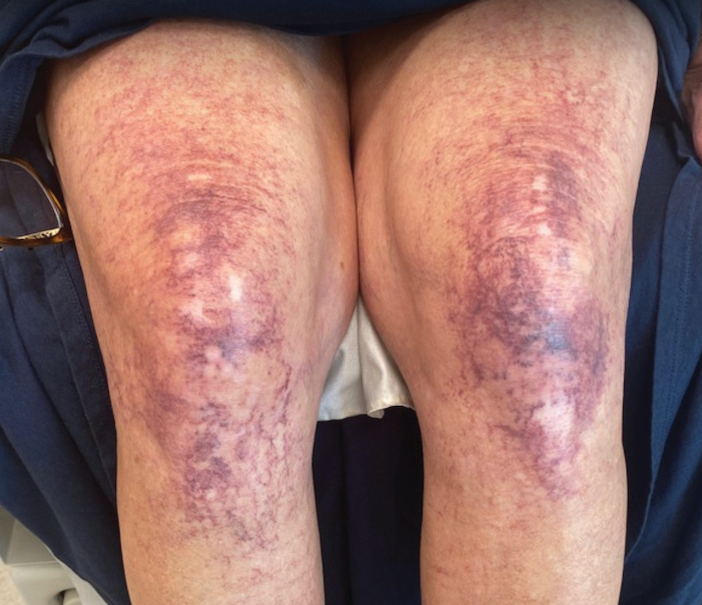

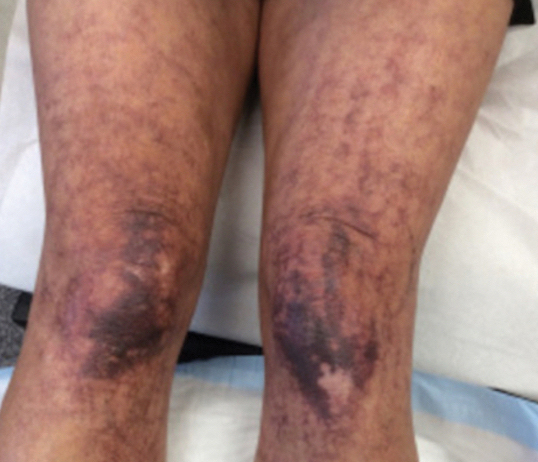

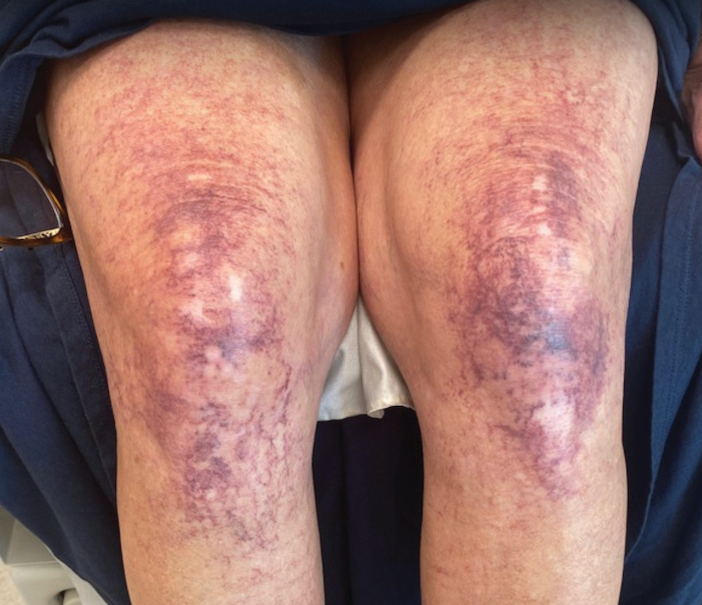

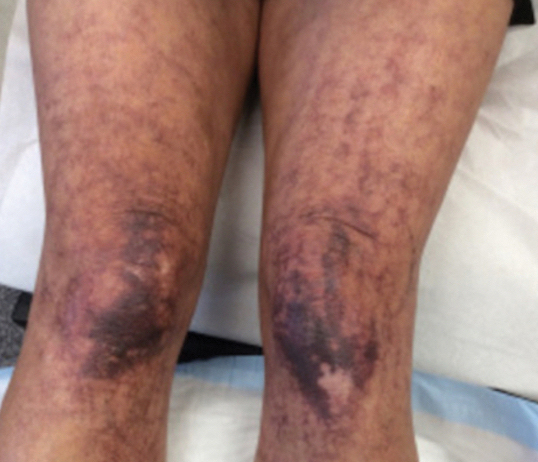

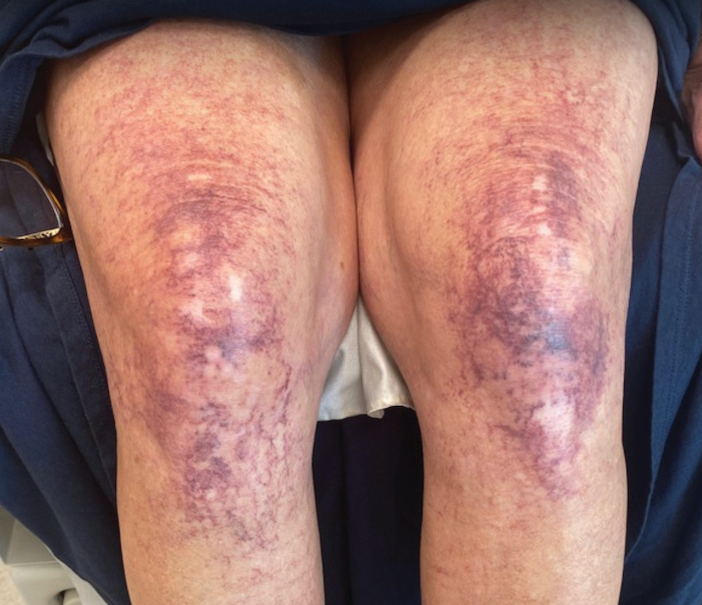

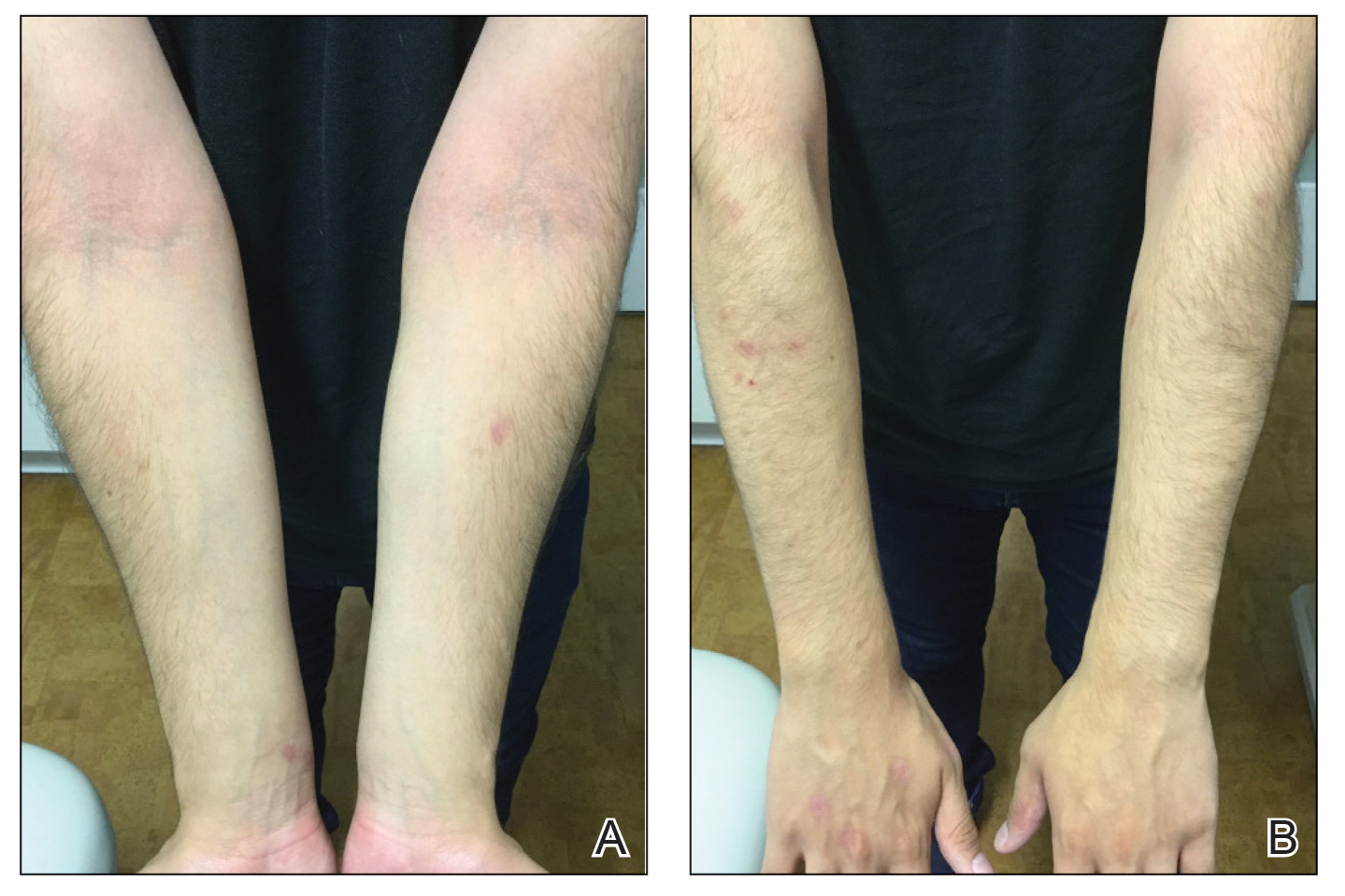

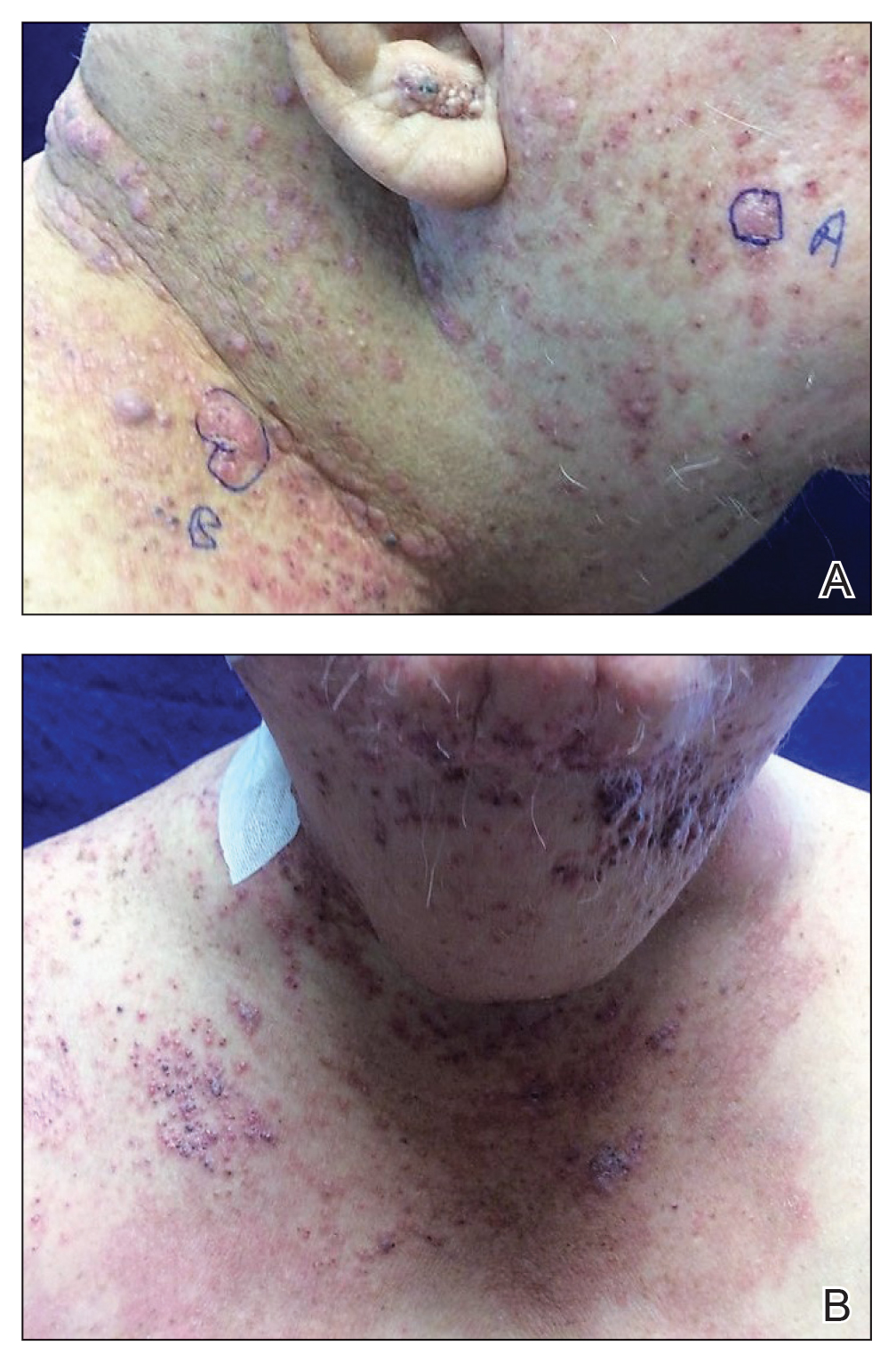

An 11-year-old boy presented to our clinic with asymptomatic vascular patterning on the left side of the body that had been present since birth. He previously was diagnosed with congenital right hemihypertrophy. He reported that the areas gradually lightened over time, and he denied any history of ulceration or venous or lymphatic malformations. Additionally, he explained how the left arm and leg have been noticeably smaller than the right extremities throughout his life. Physical examination revealed superficial, violaceous, reticulated patches along the left upper back tracking down the arm, abdomen (Figure 1A), and anterior thigh (Figure 1B) without crossing the midline. A few dilated veins were noted in the same region as the patches. There was no evidence of scarring or depression found in the skin. The right arms and legs were visibly larger compared to the left side (Figure 2A), and there also was macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand (Figure 2B). Radiography confirmed the limb length discrepancy and showed the right and left legs to measure 73.2 cm and 71.3 cm, respectively. Given the patient’s multifocal reticulated CMs and ipsilateral undergrowth, a diagnosis of DCMU was rendered. The superficial vascular pattern is likely to fade over time, which will partially be hidden by his darker complexion. He also was advised to continue to see an orthopedist to monitor the limb length incongruity. Surgical intervention was not recommended.

It ordinarily is thought that vascular anomalies of a limb may result in hypertrophy due to increased blood flow such as in KTS, but there are occasions where the affected limb(s) are inexplicably smaller.2,4 Cubiró et al3 observed that in 6 patients with unilateral CMs, all had ipsilateral limb undergrowth. They proposed the term diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth as a distinct counterpart to DCMO. Diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth is most similar to CMTC, as both can present with patchy or reticulated capillary staining with ipsilateral limb hypotrophy, but girth more often is affected than length; CMTC also may be associated with dermal atrophy and ulceration.2 The lesions of CMTC typically diminish within the first few years of life whereas those in DCMU tend to persist. Patients with KTS also can exhibit soft-tissue and bony undergrowth, which is termed inverse Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome3; however, the lack of the triad of capillary-lymphatic-venous malformation in our patient made this condition less likely. Additionally, it appears that our patient had left-sided undergrowth rather than the previously diagnosed right hemihypertrophy. The ipsilateral macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand was an interesting observation and contrasted the undergrowth apparent in the rest of the left limb, which could be caused by increased blood flow specifically to the third digit resembling DCMO.4

Of note, genetic mutations have been implicated as a cause of vascular malformations and growth abnormalities. Specifically, mutations in the phosphoinositide-3-kinase–AKT pathway have been reported in these cases likely due its role in cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis.3,4 Future studies should investigate genetic associations in patients with DCMU to determine if there is a robust genotypic-phenotypic link.

Although CMs are a common occurrence in pediatric dermatology, CMs with concurrent limb undergrowth are rare. Our patient’s unique features included involvement of both an arm and leg as well as the presence of macrodactyly. We agree with the terminology for DCMU to describe multifocal reticulated vascular patterning with ipsilateral undergrowth.3

- Huang JT, Liang MG. Vascular malformations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1091-1110. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.08.003

- Lee MS, Liang MG, Mulliken JB. Diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth: a clinical subtype of vascular anomalies with hypertrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:589-594. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.030

- Cubiró X, Rozas‐Muñoz E, Castel P, et al. Clinical and genetic evaluation of six children with diffuse capillary malformation and undergrowth. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:833-838. doi:10.1111/pde.14252

- Uihlein LC, Liang MG, Fishman SJ, et al. Capillary-venous malformation in the lower limb. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:541-548. doi:10.1111/pde.12186

To the Editor:

Capillary malformations (CMs), the most common vascular malformations that can affect the skin,1 present clinically as macules and patches of various colors, shapes, and sizes. Congenital structural abnormalities are associated with conditions such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC), and megalencephaly–capillary malformation syndrome.2 Diffuse CM with overgrowth (DCMO) of the soft tissue and bones is an established association of CMs; however, diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth (DCMU) is a more recent term that describes the lesser-recognized counterpart to DCMO.3 Herein, we describe a case of CM with left-sided undergrowth.

An 11-year-old boy presented to our clinic with asymptomatic vascular patterning on the left side of the body that had been present since birth. He previously was diagnosed with congenital right hemihypertrophy. He reported that the areas gradually lightened over time, and he denied any history of ulceration or venous or lymphatic malformations. Additionally, he explained how the left arm and leg have been noticeably smaller than the right extremities throughout his life. Physical examination revealed superficial, violaceous, reticulated patches along the left upper back tracking down the arm, abdomen (Figure 1A), and anterior thigh (Figure 1B) without crossing the midline. A few dilated veins were noted in the same region as the patches. There was no evidence of scarring or depression found in the skin. The right arms and legs were visibly larger compared to the left side (Figure 2A), and there also was macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand (Figure 2B). Radiography confirmed the limb length discrepancy and showed the right and left legs to measure 73.2 cm and 71.3 cm, respectively. Given the patient’s multifocal reticulated CMs and ipsilateral undergrowth, a diagnosis of DCMU was rendered. The superficial vascular pattern is likely to fade over time, which will partially be hidden by his darker complexion. He also was advised to continue to see an orthopedist to monitor the limb length incongruity. Surgical intervention was not recommended.

It ordinarily is thought that vascular anomalies of a limb may result in hypertrophy due to increased blood flow such as in KTS, but there are occasions where the affected limb(s) are inexplicably smaller.2,4 Cubiró et al3 observed that in 6 patients with unilateral CMs, all had ipsilateral limb undergrowth. They proposed the term diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth as a distinct counterpart to DCMO. Diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth is most similar to CMTC, as both can present with patchy or reticulated capillary staining with ipsilateral limb hypotrophy, but girth more often is affected than length; CMTC also may be associated with dermal atrophy and ulceration.2 The lesions of CMTC typically diminish within the first few years of life whereas those in DCMU tend to persist. Patients with KTS also can exhibit soft-tissue and bony undergrowth, which is termed inverse Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome3; however, the lack of the triad of capillary-lymphatic-venous malformation in our patient made this condition less likely. Additionally, it appears that our patient had left-sided undergrowth rather than the previously diagnosed right hemihypertrophy. The ipsilateral macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand was an interesting observation and contrasted the undergrowth apparent in the rest of the left limb, which could be caused by increased blood flow specifically to the third digit resembling DCMO.4

Of note, genetic mutations have been implicated as a cause of vascular malformations and growth abnormalities. Specifically, mutations in the phosphoinositide-3-kinase–AKT pathway have been reported in these cases likely due its role in cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis.3,4 Future studies should investigate genetic associations in patients with DCMU to determine if there is a robust genotypic-phenotypic link.

Although CMs are a common occurrence in pediatric dermatology, CMs with concurrent limb undergrowth are rare. Our patient’s unique features included involvement of both an arm and leg as well as the presence of macrodactyly. We agree with the terminology for DCMU to describe multifocal reticulated vascular patterning with ipsilateral undergrowth.3

To the Editor:

Capillary malformations (CMs), the most common vascular malformations that can affect the skin,1 present clinically as macules and patches of various colors, shapes, and sizes. Congenital structural abnormalities are associated with conditions such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC), and megalencephaly–capillary malformation syndrome.2 Diffuse CM with overgrowth (DCMO) of the soft tissue and bones is an established association of CMs; however, diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth (DCMU) is a more recent term that describes the lesser-recognized counterpart to DCMO.3 Herein, we describe a case of CM with left-sided undergrowth.

An 11-year-old boy presented to our clinic with asymptomatic vascular patterning on the left side of the body that had been present since birth. He previously was diagnosed with congenital right hemihypertrophy. He reported that the areas gradually lightened over time, and he denied any history of ulceration or venous or lymphatic malformations. Additionally, he explained how the left arm and leg have been noticeably smaller than the right extremities throughout his life. Physical examination revealed superficial, violaceous, reticulated patches along the left upper back tracking down the arm, abdomen (Figure 1A), and anterior thigh (Figure 1B) without crossing the midline. A few dilated veins were noted in the same region as the patches. There was no evidence of scarring or depression found in the skin. The right arms and legs were visibly larger compared to the left side (Figure 2A), and there also was macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand (Figure 2B). Radiography confirmed the limb length discrepancy and showed the right and left legs to measure 73.2 cm and 71.3 cm, respectively. Given the patient’s multifocal reticulated CMs and ipsilateral undergrowth, a diagnosis of DCMU was rendered. The superficial vascular pattern is likely to fade over time, which will partially be hidden by his darker complexion. He also was advised to continue to see an orthopedist to monitor the limb length incongruity. Surgical intervention was not recommended.

It ordinarily is thought that vascular anomalies of a limb may result in hypertrophy due to increased blood flow such as in KTS, but there are occasions where the affected limb(s) are inexplicably smaller.2,4 Cubiró et al3 observed that in 6 patients with unilateral CMs, all had ipsilateral limb undergrowth. They proposed the term diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth as a distinct counterpart to DCMO. Diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth is most similar to CMTC, as both can present with patchy or reticulated capillary staining with ipsilateral limb hypotrophy, but girth more often is affected than length; CMTC also may be associated with dermal atrophy and ulceration.2 The lesions of CMTC typically diminish within the first few years of life whereas those in DCMU tend to persist. Patients with KTS also can exhibit soft-tissue and bony undergrowth, which is termed inverse Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome3; however, the lack of the triad of capillary-lymphatic-venous malformation in our patient made this condition less likely. Additionally, it appears that our patient had left-sided undergrowth rather than the previously diagnosed right hemihypertrophy. The ipsilateral macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand was an interesting observation and contrasted the undergrowth apparent in the rest of the left limb, which could be caused by increased blood flow specifically to the third digit resembling DCMO.4

Of note, genetic mutations have been implicated as a cause of vascular malformations and growth abnormalities. Specifically, mutations in the phosphoinositide-3-kinase–AKT pathway have been reported in these cases likely due its role in cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis.3,4 Future studies should investigate genetic associations in patients with DCMU to determine if there is a robust genotypic-phenotypic link.

Although CMs are a common occurrence in pediatric dermatology, CMs with concurrent limb undergrowth are rare. Our patient’s unique features included involvement of both an arm and leg as well as the presence of macrodactyly. We agree with the terminology for DCMU to describe multifocal reticulated vascular patterning with ipsilateral undergrowth.3

- Huang JT, Liang MG. Vascular malformations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1091-1110. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.08.003

- Lee MS, Liang MG, Mulliken JB. Diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth: a clinical subtype of vascular anomalies with hypertrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:589-594. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.030

- Cubiró X, Rozas‐Muñoz E, Castel P, et al. Clinical and genetic evaluation of six children with diffuse capillary malformation and undergrowth. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:833-838. doi:10.1111/pde.14252

- Uihlein LC, Liang MG, Fishman SJ, et al. Capillary-venous malformation in the lower limb. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:541-548. doi:10.1111/pde.12186

- Huang JT, Liang MG. Vascular malformations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1091-1110. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.08.003

- Lee MS, Liang MG, Mulliken JB. Diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth: a clinical subtype of vascular anomalies with hypertrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:589-594. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.030

- Cubiró X, Rozas‐Muñoz E, Castel P, et al. Clinical and genetic evaluation of six children with diffuse capillary malformation and undergrowth. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:833-838. doi:10.1111/pde.14252

- Uihlein LC, Liang MG, Fishman SJ, et al. Capillary-venous malformation in the lower limb. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:541-548. doi:10.1111/pde.12186

Practice Points

- The term diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth (DCMU) describes a distinct counterpart to diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth. It can be challenging to distinguish from other vascular malformations associated with congenital structural abnormalities.

- The vascular patterning of DCMU may fade over time, but patients should continue to be monitored for their structural incongruity.

Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hand: A Distinctive Variant of Sweet Syndrome

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand (NDDH) is an uncommon reactive neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a painful, enlarging, ulcerative nodule. It often is misdiagnosed and initially treated as an infection. Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, it is associated with underlying infections, inflammatory conditions, and malignancies. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand is considered a subset of Sweet syndrome (SS); we highlight similarities and differences between NDDH and SS, reporting the case of a 66-year-old man without systemic symptoms who developed NDDH on the right hand.

A 66-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, painful, ulcerative, 2-cm nodule on the right hand following mechanical trauma 2 weeks prior (Figure 1). He was afebrile with no remarkable medical history. Laboratory evaluation revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 20 mm/h (reference range, 0-10 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 3.52 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL) without leukocytosis; both were not remarkably elevated when adjusted for age.1,2 The clinical differential diagnosis was broad and included pyoderma with evolving cellulitis, neutrophilic dermatosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, subcutaneous or deep fungal infection, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous lymphoma, and metastasis. Due to the rapid development of the lesion, initial treatment focused on a bacterial infection, but there was no improvement on antibiotics and wound cultures were negative. The ulcerative nodule was biopsied, and histopathology demonstrated abundant neutrophilic inflammation, endothelial swelling, and leukocytoclasis without microorganisms (Figure 2). Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. A diagnosis of NDDH was made based on clinical and histologic findings. The wound improved with a 3-week course of oral prednisone.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand is a subset of reactive neutrophilic dermatoses, which includes SS (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) and pyoderma gangrenosum. It is described as a localized variant of SS, with similar associated underlying inflammatory, neoplastic conditions and laboratory findings.3 However, NDDH has characteristic features that differ from classic SS. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand typically presents as painful papules, pustules, or ulcers that progress to become larger ulcers, plaques, and nodules. The clinical appearance may more closely resemble pyoderma gangrenosum or atypical SS, with ulceration frequently present. Pathergy also may be demonstrated in NDDH, similar to our patient. The average age of presentation for NDDH is 60 years, which is older than the average age for SS or pyoderma gangrenosum.3 Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, NDDH responds well to oral steroids or steroid-sparing immunosuppressants such as dapsone, colchicine, azathioprine, or tetracycline antibiotics.4

The criteria for SS are well established5,6 and may be used for the diagnosis of NDDH, taking into account the localization of lesions to the dorsal aspect of the hands. The diagnostic criteria for SS include fulfillment of both major and at least 2 of 4 minor criteria. The 2 major criteria include rapid presentation of skin lesions and neutrophilic dermal infiltrate on biopsy. Minor criteria are defined as the following: (1) preceding nonspecific respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, inflammatory conditions, underlying malignancy, or pregnancy; (2) fever; (3) excellent response to steroids; and (4) 3 of the 4 of the following laboratory abnormalities: elevated CRP, ESR, leukocytosis, or left shift in complete blood cell count. Our patient met both major criteria and only 1 minor criterion—excellent response to systemic corticosteroids. Nofal et al7 advocated for revised diagnostic criteria for SS, with one suggestion utilizing only the 2 major criteria being necessary for diagnosis. Given that serum inflammatory markers may not be as elevated in NDDH compared to SS,3,7,8 meeting the major criteria alone may be a better way to diagnose NDDH, as in our patient.

Our patient presented with an expanding ulcerating nodule on the hand that elicited a wide list of differential diagnoses to include infections and neoplasms. Rapid development, localization to the dorsal aspect of the hand, and treatment resistance to antibiotics may help the clinician consider a diagnosis of NDDH, which should be confirmed by a biopsy. Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, an underlying malignancy or inflammatory condition should be sought out. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand responds well to systemic steroids, though recurrences may occur.

- Miller A, Green M, Robinson D. Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Br Med (Clinical Res Ed). 1983;286:226.

- Wyczalkowska-Tomasik A, Czarkowska-Paczek B, Zielenkiewicz M, et al. Inflammatory markers change with age, but do not fall beyond reported normal ranges. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2016;64:249-254.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Gaulding J, Kohen LL. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017; 76(6 suppl 1):AB178.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Nofal A, Abdelmaksoud A, Amer H, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: diagnostic criteria revisited. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:1081-1088.

- Wolf R, Tüzün Y. Acral manifestations of Sweet syndrome (neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands). Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:81-84.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand (NDDH) is an uncommon reactive neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a painful, enlarging, ulcerative nodule. It often is misdiagnosed and initially treated as an infection. Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, it is associated with underlying infections, inflammatory conditions, and malignancies. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand is considered a subset of Sweet syndrome (SS); we highlight similarities and differences between NDDH and SS, reporting the case of a 66-year-old man without systemic symptoms who developed NDDH on the right hand.

A 66-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, painful, ulcerative, 2-cm nodule on the right hand following mechanical trauma 2 weeks prior (Figure 1). He was afebrile with no remarkable medical history. Laboratory evaluation revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 20 mm/h (reference range, 0-10 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 3.52 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL) without leukocytosis; both were not remarkably elevated when adjusted for age.1,2 The clinical differential diagnosis was broad and included pyoderma with evolving cellulitis, neutrophilic dermatosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, subcutaneous or deep fungal infection, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous lymphoma, and metastasis. Due to the rapid development of the lesion, initial treatment focused on a bacterial infection, but there was no improvement on antibiotics and wound cultures were negative. The ulcerative nodule was biopsied, and histopathology demonstrated abundant neutrophilic inflammation, endothelial swelling, and leukocytoclasis without microorganisms (Figure 2). Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. A diagnosis of NDDH was made based on clinical and histologic findings. The wound improved with a 3-week course of oral prednisone.

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand is a subset of reactive neutrophilic dermatoses, which includes SS (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) and pyoderma gangrenosum. It is described as a localized variant of SS, with similar associated underlying inflammatory, neoplastic conditions and laboratory findings.3 However, NDDH has characteristic features that differ from classic SS. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand typically presents as painful papules, pustules, or ulcers that progress to become larger ulcers, plaques, and nodules. The clinical appearance may more closely resemble pyoderma gangrenosum or atypical SS, with ulceration frequently present. Pathergy also may be demonstrated in NDDH, similar to our patient. The average age of presentation for NDDH is 60 years, which is older than the average age for SS or pyoderma gangrenosum.3 Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, NDDH responds well to oral steroids or steroid-sparing immunosuppressants such as dapsone, colchicine, azathioprine, or tetracycline antibiotics.4

The criteria for SS are well established5,6 and may be used for the diagnosis of NDDH, taking into account the localization of lesions to the dorsal aspect of the hands. The diagnostic criteria for SS include fulfillment of both major and at least 2 of 4 minor criteria. The 2 major criteria include rapid presentation of skin lesions and neutrophilic dermal infiltrate on biopsy. Minor criteria are defined as the following: (1) preceding nonspecific respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, inflammatory conditions, underlying malignancy, or pregnancy; (2) fever; (3) excellent response to steroids; and (4) 3 of the 4 of the following laboratory abnormalities: elevated CRP, ESR, leukocytosis, or left shift in complete blood cell count. Our patient met both major criteria and only 1 minor criterion—excellent response to systemic corticosteroids. Nofal et al7 advocated for revised diagnostic criteria for SS, with one suggestion utilizing only the 2 major criteria being necessary for diagnosis. Given that serum inflammatory markers may not be as elevated in NDDH compared to SS,3,7,8 meeting the major criteria alone may be a better way to diagnose NDDH, as in our patient.

Our patient presented with an expanding ulcerating nodule on the hand that elicited a wide list of differential diagnoses to include infections and neoplasms. Rapid development, localization to the dorsal aspect of the hand, and treatment resistance to antibiotics may help the clinician consider a diagnosis of NDDH, which should be confirmed by a biopsy. Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, an underlying malignancy or inflammatory condition should be sought out. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand responds well to systemic steroids, though recurrences may occur.

To the Editor:

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand (NDDH) is an uncommon reactive neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a painful, enlarging, ulcerative nodule. It often is misdiagnosed and initially treated as an infection. Similar to other neutrophilic dermatoses, it is associated with underlying infections, inflammatory conditions, and malignancies. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand is considered a subset of Sweet syndrome (SS); we highlight similarities and differences between NDDH and SS, reporting the case of a 66-year-old man without systemic symptoms who developed NDDH on the right hand.

A 66-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, painful, ulcerative, 2-cm nodule on the right hand following mechanical trauma 2 weeks prior (Figure 1). He was afebrile with no remarkable medical history. Laboratory evaluation revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 20 mm/h (reference range, 0-10 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 3.52 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL) without leukocytosis; both were not remarkably elevated when adjusted for age.1,2 The clinical differential diagnosis was broad and included pyoderma with evolving cellulitis, neutrophilic dermatosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, subcutaneous or deep fungal infection, squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous lymphoma, and metastasis. Due to the rapid development of the lesion, initial treatment focused on a bacterial infection, but there was no improvement on antibiotics and wound cultures were negative. The ulcerative nodule was biopsied, and histopathology demonstrated abundant neutrophilic inflammation, endothelial swelling, and leukocytoclasis without microorganisms (Figure 2). Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. A diagnosis of NDDH was made based on clinical and histologic findings. The wound improved with a 3-week course of oral prednisone.