User login

The cost of conflation: Avoiding loose talk about the duty to warn

The campaign, election, and administration of President Donald Trump have reinvigorated debate over rule 7.3 of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) code of ethics. Known as the Goldwater Rule for its historical roots in a magazine profile and subsequent libel suit by the 1964 Republican presidential nominee,1 this standard deems it unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion of a public figure without conducting an examination and obtaining authorization.2 The American Psychological Association similarly provides that assessments must be based on adequate examination of the individual.3

Growing controversy

Shortly after President Trump’s inauguration, a group of 35 mental health professionals penned a letter in the New York Times stating that he was “incapable of serving safely as president.” Importantly, the writers couched their conclusions in professional expertise and specifically criticized the Goldwater Rule as having subjected their colleagues to self-imposed silence.4 A prominent psychiatrist, Allen J. Frances, MD, responded the following day to caution against “psychiatric name-calling” as a substitute for political action.5

Since then, psychiatrists classifying the APA ethics position as a “gag rule” preventing them from performing a public service have garnered considerable press coverage. When the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) reiterated this summer that only APA members are bound by the Goldwater Rule, Boston Globe Media’s STAT news outlet misreported it as a license for psychiatrists to disregard the standard. Amid the ensuing media storm, the APsaA was forced to clarify that it was not countenancing defiance of psychiatry’s flagship organization and that its own longstanding policy remained unchanged.

Among those chafing against the Goldwater Rule in the current political environment, a call to arms has been the profession’s supposed “duty to warn” the public of the president’s mental health. This rationale was made explicit in an eponymous online movement and town hall forum hosted by Bandy X. Lee, MD, MDiv, a member of Yale University’s psychiatry faculty. According to these critics, an inherent tension exists between the Goldwater Rule’s prohibition on volunteering professional opinions from afar and the imperative to warn about the dangers posed by a leader with mental illness.

The duty to warn

Clinicians’ obligation to warn third parties when patients make credible threats or pose a high risk of harm emanates from various state laws, court decisions, and professional ethics rules. In the seminal Tarasoff case, a patient divulged in the course of psychotherapy his plan to murder a fellow student who had rejected his romantic overtures; campus police were alerted, but the intended victim was not. After the plan came to fruition, the California Supreme Court held that therapists must exercise reasonable care to protect “foreseeable victims” where they know or should know that a patient poses a serious danger.6

Although a controversial and massive expansion of tort liability 40 years ago, the basic tenets of Tarasoff have since been adopted by numerous courts, state legislatures, and professional organizations. The American Medical Association (AMA) recognizes an exception to confidentiality to mitigate serious threats of harm to the patient or other identifiable individuals.7 To enable health care professionals to operate in a way that is consistent with these standards, the HIPAA Privacy Rule expressly permits doctors to disclose protected health information, including psychotherapy notes, if the disclosure “is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public.”8

In terms of both professional ethics and privacy law, the duty to warn is framed as a limited and enumerated exception to the general rule that patient communications must be kept in confidence. In the absence of a clinician’s being privy to personal details about a patient via interview and examination, the duty to warn loses all coherence. It is precisely the intimacy of the doctor-patient relationship that gives rise to the fiduciary duty of confidentiality, which in turn must yield to public safety in rare situations where a credible threat is issued against an identifiable victim.

Origins of a misconception

Unlike the duty to warn, the Goldwater Rule is neither premised on nor a departure from the dictates of confidentiality. The rule is codified under the section of the APA ethics standards dealing with community and public health activities, not patient privacy. In nearly all cases where the Goldwater Rule could be invoked, the fundamental issue is that no examination has occurred. If it had, informed consent would be required for treatment, and appropriate authorization would be required for disclosure. Moreover, talking with the media – as opposed to alerting law enforcement, family members, or the subject of a threat – would almost never qualify as an appropriate outlet for discharging a physician’s duty to warn.

Whatever its merits, the Goldwater Rule is intended to distinguish between educational activities – in which psychiatrists share their expertise with the public and shed light on mental illness – and professional opinion wherein psychiatrists offer diagnoses or prognoses unsolicited by the individual.9

The APA has since clarified that the Goldwater Rule does not prohibit “psychologically informed leadership studies” so long as they maintain scholarly standards and do not specify a clinical diagnosis. When appropriately conducted as academic research, including acknowledgment of inherent limitations, psychological profiles do not implicate the Goldwater Rule by drawing clinical conclusions outside clinical practice.

Ultimately, the debate over the Goldwater Rule pits concerns over professional standards and respect for persons against the ability of psychiatrists to apply the expertise and language of their profession according to their own best judgment, without running afoul of an ethical norm. The premise that the Tarasoff principle overrides the Goldwater Rule is a red herring that does a disservice to both. There may be valid reasons to reevaluate the Goldwater Rule, but the duty to warn is not one of them.

Lt. Col. Charles G. Kels practices health and disability law in the U.S. Air Force. Dr. Lori H. Kels teaches and practices psychiatry at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine in San Antonio. Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Air Force or Department of Defense.

References

1. Goldwater v. Ginzburg, 414 F2d 324 (2d Cir 1969), cert denied, 396 US 1049 (1970).

2. APA Principles of Medical Ethics, 2013 ed. [7.3].

3. American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Ethics, 2016 ed. [9.01b].

4. The New York Times. Feb. 14, 2017.

5. The New York Times. Feb. 15, 2017.

6. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

7. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1(e) Confidentiality].

8. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 164.512(j)

9. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1348-50.

10. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25(3):A635-A46.

11. APA Opinions of the Ethics Committee, 2017 ed. [Q.7.a].

The campaign, election, and administration of President Donald Trump have reinvigorated debate over rule 7.3 of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) code of ethics. Known as the Goldwater Rule for its historical roots in a magazine profile and subsequent libel suit by the 1964 Republican presidential nominee,1 this standard deems it unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion of a public figure without conducting an examination and obtaining authorization.2 The American Psychological Association similarly provides that assessments must be based on adequate examination of the individual.3

Growing controversy

Shortly after President Trump’s inauguration, a group of 35 mental health professionals penned a letter in the New York Times stating that he was “incapable of serving safely as president.” Importantly, the writers couched their conclusions in professional expertise and specifically criticized the Goldwater Rule as having subjected their colleagues to self-imposed silence.4 A prominent psychiatrist, Allen J. Frances, MD, responded the following day to caution against “psychiatric name-calling” as a substitute for political action.5

Since then, psychiatrists classifying the APA ethics position as a “gag rule” preventing them from performing a public service have garnered considerable press coverage. When the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) reiterated this summer that only APA members are bound by the Goldwater Rule, Boston Globe Media’s STAT news outlet misreported it as a license for psychiatrists to disregard the standard. Amid the ensuing media storm, the APsaA was forced to clarify that it was not countenancing defiance of psychiatry’s flagship organization and that its own longstanding policy remained unchanged.

Among those chafing against the Goldwater Rule in the current political environment, a call to arms has been the profession’s supposed “duty to warn” the public of the president’s mental health. This rationale was made explicit in an eponymous online movement and town hall forum hosted by Bandy X. Lee, MD, MDiv, a member of Yale University’s psychiatry faculty. According to these critics, an inherent tension exists between the Goldwater Rule’s prohibition on volunteering professional opinions from afar and the imperative to warn about the dangers posed by a leader with mental illness.

The duty to warn

Clinicians’ obligation to warn third parties when patients make credible threats or pose a high risk of harm emanates from various state laws, court decisions, and professional ethics rules. In the seminal Tarasoff case, a patient divulged in the course of psychotherapy his plan to murder a fellow student who had rejected his romantic overtures; campus police were alerted, but the intended victim was not. After the plan came to fruition, the California Supreme Court held that therapists must exercise reasonable care to protect “foreseeable victims” where they know or should know that a patient poses a serious danger.6

Although a controversial and massive expansion of tort liability 40 years ago, the basic tenets of Tarasoff have since been adopted by numerous courts, state legislatures, and professional organizations. The American Medical Association (AMA) recognizes an exception to confidentiality to mitigate serious threats of harm to the patient or other identifiable individuals.7 To enable health care professionals to operate in a way that is consistent with these standards, the HIPAA Privacy Rule expressly permits doctors to disclose protected health information, including psychotherapy notes, if the disclosure “is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public.”8

In terms of both professional ethics and privacy law, the duty to warn is framed as a limited and enumerated exception to the general rule that patient communications must be kept in confidence. In the absence of a clinician’s being privy to personal details about a patient via interview and examination, the duty to warn loses all coherence. It is precisely the intimacy of the doctor-patient relationship that gives rise to the fiduciary duty of confidentiality, which in turn must yield to public safety in rare situations where a credible threat is issued against an identifiable victim.

Origins of a misconception

Unlike the duty to warn, the Goldwater Rule is neither premised on nor a departure from the dictates of confidentiality. The rule is codified under the section of the APA ethics standards dealing with community and public health activities, not patient privacy. In nearly all cases where the Goldwater Rule could be invoked, the fundamental issue is that no examination has occurred. If it had, informed consent would be required for treatment, and appropriate authorization would be required for disclosure. Moreover, talking with the media – as opposed to alerting law enforcement, family members, or the subject of a threat – would almost never qualify as an appropriate outlet for discharging a physician’s duty to warn.

Whatever its merits, the Goldwater Rule is intended to distinguish between educational activities – in which psychiatrists share their expertise with the public and shed light on mental illness – and professional opinion wherein psychiatrists offer diagnoses or prognoses unsolicited by the individual.9

The APA has since clarified that the Goldwater Rule does not prohibit “psychologically informed leadership studies” so long as they maintain scholarly standards and do not specify a clinical diagnosis. When appropriately conducted as academic research, including acknowledgment of inherent limitations, psychological profiles do not implicate the Goldwater Rule by drawing clinical conclusions outside clinical practice.

Ultimately, the debate over the Goldwater Rule pits concerns over professional standards and respect for persons against the ability of psychiatrists to apply the expertise and language of their profession according to their own best judgment, without running afoul of an ethical norm. The premise that the Tarasoff principle overrides the Goldwater Rule is a red herring that does a disservice to both. There may be valid reasons to reevaluate the Goldwater Rule, but the duty to warn is not one of them.

Lt. Col. Charles G. Kels practices health and disability law in the U.S. Air Force. Dr. Lori H. Kels teaches and practices psychiatry at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine in San Antonio. Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Air Force or Department of Defense.

References

1. Goldwater v. Ginzburg, 414 F2d 324 (2d Cir 1969), cert denied, 396 US 1049 (1970).

2. APA Principles of Medical Ethics, 2013 ed. [7.3].

3. American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Ethics, 2016 ed. [9.01b].

4. The New York Times. Feb. 14, 2017.

5. The New York Times. Feb. 15, 2017.

6. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

7. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1(e) Confidentiality].

8. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 164.512(j)

9. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1348-50.

10. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25(3):A635-A46.

11. APA Opinions of the Ethics Committee, 2017 ed. [Q.7.a].

The campaign, election, and administration of President Donald Trump have reinvigorated debate over rule 7.3 of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) code of ethics. Known as the Goldwater Rule for its historical roots in a magazine profile and subsequent libel suit by the 1964 Republican presidential nominee,1 this standard deems it unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion of a public figure without conducting an examination and obtaining authorization.2 The American Psychological Association similarly provides that assessments must be based on adequate examination of the individual.3

Growing controversy

Shortly after President Trump’s inauguration, a group of 35 mental health professionals penned a letter in the New York Times stating that he was “incapable of serving safely as president.” Importantly, the writers couched their conclusions in professional expertise and specifically criticized the Goldwater Rule as having subjected their colleagues to self-imposed silence.4 A prominent psychiatrist, Allen J. Frances, MD, responded the following day to caution against “psychiatric name-calling” as a substitute for political action.5

Since then, psychiatrists classifying the APA ethics position as a “gag rule” preventing them from performing a public service have garnered considerable press coverage. When the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) reiterated this summer that only APA members are bound by the Goldwater Rule, Boston Globe Media’s STAT news outlet misreported it as a license for psychiatrists to disregard the standard. Amid the ensuing media storm, the APsaA was forced to clarify that it was not countenancing defiance of psychiatry’s flagship organization and that its own longstanding policy remained unchanged.

Among those chafing against the Goldwater Rule in the current political environment, a call to arms has been the profession’s supposed “duty to warn” the public of the president’s mental health. This rationale was made explicit in an eponymous online movement and town hall forum hosted by Bandy X. Lee, MD, MDiv, a member of Yale University’s psychiatry faculty. According to these critics, an inherent tension exists between the Goldwater Rule’s prohibition on volunteering professional opinions from afar and the imperative to warn about the dangers posed by a leader with mental illness.

The duty to warn

Clinicians’ obligation to warn third parties when patients make credible threats or pose a high risk of harm emanates from various state laws, court decisions, and professional ethics rules. In the seminal Tarasoff case, a patient divulged in the course of psychotherapy his plan to murder a fellow student who had rejected his romantic overtures; campus police were alerted, but the intended victim was not. After the plan came to fruition, the California Supreme Court held that therapists must exercise reasonable care to protect “foreseeable victims” where they know or should know that a patient poses a serious danger.6

Although a controversial and massive expansion of tort liability 40 years ago, the basic tenets of Tarasoff have since been adopted by numerous courts, state legislatures, and professional organizations. The American Medical Association (AMA) recognizes an exception to confidentiality to mitigate serious threats of harm to the patient or other identifiable individuals.7 To enable health care professionals to operate in a way that is consistent with these standards, the HIPAA Privacy Rule expressly permits doctors to disclose protected health information, including psychotherapy notes, if the disclosure “is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public.”8

In terms of both professional ethics and privacy law, the duty to warn is framed as a limited and enumerated exception to the general rule that patient communications must be kept in confidence. In the absence of a clinician’s being privy to personal details about a patient via interview and examination, the duty to warn loses all coherence. It is precisely the intimacy of the doctor-patient relationship that gives rise to the fiduciary duty of confidentiality, which in turn must yield to public safety in rare situations where a credible threat is issued against an identifiable victim.

Origins of a misconception

Unlike the duty to warn, the Goldwater Rule is neither premised on nor a departure from the dictates of confidentiality. The rule is codified under the section of the APA ethics standards dealing with community and public health activities, not patient privacy. In nearly all cases where the Goldwater Rule could be invoked, the fundamental issue is that no examination has occurred. If it had, informed consent would be required for treatment, and appropriate authorization would be required for disclosure. Moreover, talking with the media – as opposed to alerting law enforcement, family members, or the subject of a threat – would almost never qualify as an appropriate outlet for discharging a physician’s duty to warn.

Whatever its merits, the Goldwater Rule is intended to distinguish between educational activities – in which psychiatrists share their expertise with the public and shed light on mental illness – and professional opinion wherein psychiatrists offer diagnoses or prognoses unsolicited by the individual.9

The APA has since clarified that the Goldwater Rule does not prohibit “psychologically informed leadership studies” so long as they maintain scholarly standards and do not specify a clinical diagnosis. When appropriately conducted as academic research, including acknowledgment of inherent limitations, psychological profiles do not implicate the Goldwater Rule by drawing clinical conclusions outside clinical practice.

Ultimately, the debate over the Goldwater Rule pits concerns over professional standards and respect for persons against the ability of psychiatrists to apply the expertise and language of their profession according to their own best judgment, without running afoul of an ethical norm. The premise that the Tarasoff principle overrides the Goldwater Rule is a red herring that does a disservice to both. There may be valid reasons to reevaluate the Goldwater Rule, but the duty to warn is not one of them.

Lt. Col. Charles G. Kels practices health and disability law in the U.S. Air Force. Dr. Lori H. Kels teaches and practices psychiatry at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine in San Antonio. Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Air Force or Department of Defense.

References

1. Goldwater v. Ginzburg, 414 F2d 324 (2d Cir 1969), cert denied, 396 US 1049 (1970).

2. APA Principles of Medical Ethics, 2013 ed. [7.3].

3. American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Ethics, 2016 ed. [9.01b].

4. The New York Times. Feb. 14, 2017.

5. The New York Times. Feb. 15, 2017.

6. Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 551 P2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

7. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, 2017 ed. [3.2.1(e) Confidentiality].

8. 45 Code of Federal Regulations 164.512(j)

9. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1348-50.

10. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25(3):A635-A46.

11. APA Opinions of the Ethics Committee, 2017 ed. [Q.7.a].

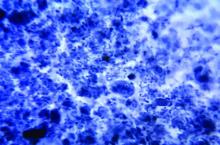

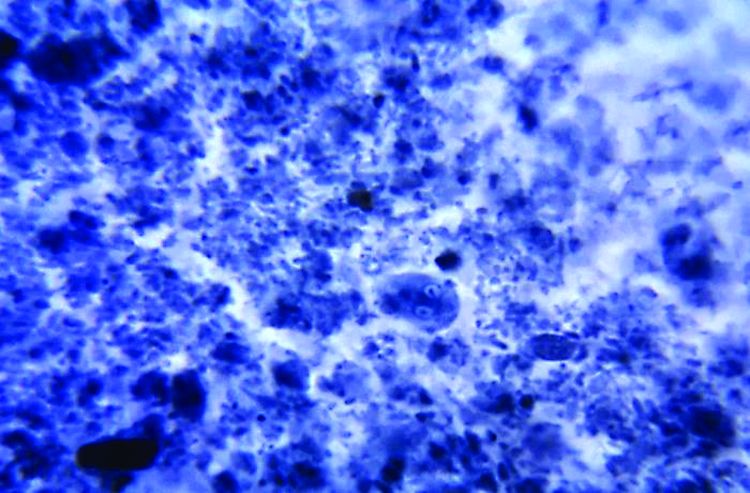

G. lamblia assemblage B more common in HIV-positive people

The intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia assemblage B was more likely in people with HIV than in people without HIV, according to research published in Acta Tropica.

Of the 65 patients with G. lamblia included in a study undertaken by Clarissa Perez Faria, PhD, and her associates at the University of Coimbra (Portugal), 38 were HIV positive, 27 were HIV negative, and 60 patients were microscopy-positive for G. lamblia. In the HIV-positive group, 19 of the 34 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 15 were assemblage A. In the HIV-negative group, 9 of the 26 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 17 were assemblage A.

“HIV infection increases the risk of having intestinal parasitic infections, including G. lamblia. The detection and treatment of infections are important measures to improve the quality of life of HIV-infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Acta Tropica (doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.026).

The intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia assemblage B was more likely in people with HIV than in people without HIV, according to research published in Acta Tropica.

Of the 65 patients with G. lamblia included in a study undertaken by Clarissa Perez Faria, PhD, and her associates at the University of Coimbra (Portugal), 38 were HIV positive, 27 were HIV negative, and 60 patients were microscopy-positive for G. lamblia. In the HIV-positive group, 19 of the 34 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 15 were assemblage A. In the HIV-negative group, 9 of the 26 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 17 were assemblage A.

“HIV infection increases the risk of having intestinal parasitic infections, including G. lamblia. The detection and treatment of infections are important measures to improve the quality of life of HIV-infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Acta Tropica (doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.026).

The intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia assemblage B was more likely in people with HIV than in people without HIV, according to research published in Acta Tropica.

Of the 65 patients with G. lamblia included in a study undertaken by Clarissa Perez Faria, PhD, and her associates at the University of Coimbra (Portugal), 38 were HIV positive, 27 were HIV negative, and 60 patients were microscopy-positive for G. lamblia. In the HIV-positive group, 19 of the 34 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 15 were assemblage A. In the HIV-negative group, 9 of the 26 microscopy-positive samples were assemblage B, and 17 were assemblage A.

“HIV infection increases the risk of having intestinal parasitic infections, including G. lamblia. The detection and treatment of infections are important measures to improve the quality of life of HIV-infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Acta Tropica (doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.026).

FROM ACTA TROPICA

Early births stress dads too

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.

“We have to understand that these fathers are now 6 weeks at home with a healthy infant, but they are still experiencing the stress of being exposed to this risk of preterm birth,” Ms. Schulze said.

By 6 months, depression had eased off in fathers whose infants made it to term; at 5%, it was similar to the rate in the control group fathers (4%) and the general population. But many fathers whose babies came early still were experiencing depression (12%).

Ms. Schulze then compared the fathers’ experience to that of the mothers. At baseline, women at risk of preterm birth had exactly the same rate of depression as their partners (35%). However, depression also was elevated among women in the control group (18%). The background rate for depression among German women is 10%, Ms. Schulze said.

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, the timing of birth did not seem to matter as much to the mothers. Depression rates were similarly elevated in those who had a preterm birth and those who did not (25%, 28%). Both were significantly higher than the 17% rate in the control group.

At 6 months, things were leveling out some for these mothers, with depression present in 10% of the preterm birth group, 19% of the full-term birth group, and 13% of the control group.

“Men seem to suffer just as much stress from this experience as women do, although perhaps in a different trajectory,” Ms. Schulze said. “Although there may be different contributing factors, we believe that the psychological care offered to mothers at risk of preterm birth should also be extended to fathers.”

She had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT WPA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Depression developed in 35% of men whose wives were admitted to the hospital for imminent preterm birth; elevated depression rates lingered for up to 6 months in these fathers.

Data source: The prospective study comprised 69 couples admitted for preterm birth risk, and 49 control couples.

Disclosures: Ms. Schulze had no financial disclosures.

Intensive exercise didn’t improve glycemic control for obese pregnant women

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

An intensive exercise intervention for obese pregnant women did not improve maternal glycemia, but did attenuate excessive gestational weight gain, according to the a single-center, randomized controlled trial published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Healthy Eating, Exercise and Lifestyle Trial, conducted from November 2013 through April 2016 at the Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital in Dublin, randomized 88 pregnant women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater at their first prenatal visit to either a medically supervised exercise program or to the control group. The intervention consisted of 50-60 minutes of exercise at least once per week, including resistance or weights and aerobic exercises (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1001-10).

However, excessive gestational weight gain at 36 weeks’ gestation (greater than 9.1 kg) was lower in the exercise group at 22.2%, compared with 43.2% in the control group (P less than .05), Niamh Daly of Coombe Women and Infants University Hospital and her coauthors reported.

“Our study may have failed to improve maternal glycemia because the ideal time to begin such a program could be before pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “Pregnant women who are obese, however, should be advised to exercise because it attenuates excessive gestational weight gain.”

The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was no difference in mean fasting plasma glucose between the control group (90.0 plus or minus 9.0 mg/dL) and the exercise group (93.6 plus or minus 7.2 mg/dL) at 24-28 weeks’ gestation (P = .13).

Data source: A single-center, randomized controlled trial of 88 pregnant women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by Friends of the Coombe, a charity organization. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

MedPAC calls for MIPS repeal

WASHINGTON – In a rare display of a near-immediate consensus, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission agreed that the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System track of the new Quality Payment Program should be scrapped, although commission members are not yet ready to endorse a replacement plan.

MedPAC staff presented its idea of “repeal and replace” less then 10 months into the first reporting year, with staff member David V. Glass noting during an Oct. 6 meeting that “MIPS will not achieve the goal of identifying and rewarding high-value clinicians.”

“Our most basic concern is that measures used in MIPS have not been proven to be associated with high-value care,” Mr. Glass said. “Many of the MIPS quality measures are process measures, assessing only the care a provider delivers within their four walls.”

MedPAC staff proposed a replacement option affecting all clinicians who are not a part of an advanced Alternative Payment Model program. Under their proposal, Medicare would withhold 2% of each clinician’s Medicare payments. Clinicians could earn back that 2% by joining a large reporting entity (either as part of a formal business structure or something like a virtual group); they could elect to join an advanced APM, earning back the 2% and possibly bonus payments; or they could do nothing and lose the 2%.

Measurements in the proposed value program would be similar to those employed by advanced APMs in that they would be focused on population-based measures assessing clinical quality, patient experience, and value. Potential measures would address avoidable admissions/emergency department visits, mortality, readmissions, ability to obtain care, ability to communicate with clinicians, spending per beneficiary, resource use, and rates of low-value care use. Measures would be calculated based on claims.

MedPAC commissioners were nearly unanimous in their agreement to the idea of repealing MIPS but were not ready to sign off on the proposed replacement.

“I’m really concerned about the burden on physicians, and I’m concerned about some of the outlandish potential rewards for groups under MIPS that can really dissuade them from investing and moving into APMs,” commission member Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution said.

“I think we really have to get rid of MIPS and either replace it with this system, which I think has a lot of merit, or just get rid of it,” said commission member Jack Hoadley, PhD, of Georgetown University in Washington, suggesting MIPS would be “even worse” than the old Sustainable Growth Rate formula over time. It is “clear to me that MIPS is not going to ... get us toward high-value care, it is not going to make clinicians’ lives better, it is not going to make patients’ lives better, and there is a lot of money at stake.”

Commission member Dana Gelb Safran, ScD, chief performance measurement and improvement officer at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts said she did not believe that there would be any value being gained in return for the money given to clinicians who participate in MIPS.

Not everyone was on board with the proposed replacement.

“I am very much in favor of repealing MIPS, but I don’t get the sense that we’ve gotten the replacement model quite right yet” because the proposed system does not do enough to get physicians into advanced APMs, commission member Craig Samitt, MD, chief clinical officer at Anthem, said. “So if a replacement is a voluntary model that would allow us to keep practicing health care the way we’ve been practicing, then that replacement is not a good replacement.”

The American Medical Association declined to evaluate the proposal that was laid forth by staff.

“The AMA welcomes ideas on how to improve Medicare physician payment policies,” AMA President David O. Barbe said in a statement. “We understand that MedPAC’s proposals are a work in progress, so it’s too early to render any judgment.”

Dr. Barbe noted that the AMA recommends that physicians participate in MIPS, even if it is at the lowest level simply to avoid any penalty and continue investing in the infrastructure to participate. The AMA, AGA, and other medical societies also are asking CMS to allow those who are exempt from MIPS participation to be able to opt into the program.

The American Medical Group Association (AMGA), a trade organization representing multispecialty medical groups, however, has criticized the move by CMS to increase the number of clinicians who are exempt from MIPS.

Under the proposed expansion – which would approximately double the number of clinicians who are MIPS exempt – “MIPS no longer provides really any incentive to get to value and in fact it’s a disincentive,” said Chet Speed, AMGA vice president of public policy. “That is one of the realities that MedPAC was dealing with.”

Mr. Speed emphasized that AMGA has not altered its policy on MIPS, which it wants to see enacted for all and has offered its own resources to help with the transition, but “if AMGA were to entertain a new position on MIPS, I think we probably would go with a more simple route, which is to just get rid of MIPS and repurpose the revenues that were in MIPS to APMs. ... We have not agreed upon that policy but that has been discussed internally.”

He added that “AMGA’s membership does look at MIPS as a tool that has really devolved from a value mechanism to a compliance exercise and nothing more.”

As to whether health care provider associations would come together and support the repeal of MIPS, Mr. Speed was hesitant to predict that, even though many have reservations about it, noting that it could be because the broadening of exclusions, which the AMA and most other associations support, effectively remove a lot of their membership from having to participate anyway, leaving the bigger groups such as Mayo, the Cleveland Clinic and Intermountain Healthcare to fight over a much smaller pot of bonus payments, significantly limiting the returns on investments made to be ready for the MIPS transition.

WASHINGTON – In a rare display of a near-immediate consensus, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission agreed that the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System track of the new Quality Payment Program should be scrapped, although commission members are not yet ready to endorse a replacement plan.

MedPAC staff presented its idea of “repeal and replace” less then 10 months into the first reporting year, with staff member David V. Glass noting during an Oct. 6 meeting that “MIPS will not achieve the goal of identifying and rewarding high-value clinicians.”

“Our most basic concern is that measures used in MIPS have not been proven to be associated with high-value care,” Mr. Glass said. “Many of the MIPS quality measures are process measures, assessing only the care a provider delivers within their four walls.”

MedPAC staff proposed a replacement option affecting all clinicians who are not a part of an advanced Alternative Payment Model program. Under their proposal, Medicare would withhold 2% of each clinician’s Medicare payments. Clinicians could earn back that 2% by joining a large reporting entity (either as part of a formal business structure or something like a virtual group); they could elect to join an advanced APM, earning back the 2% and possibly bonus payments; or they could do nothing and lose the 2%.

Measurements in the proposed value program would be similar to those employed by advanced APMs in that they would be focused on population-based measures assessing clinical quality, patient experience, and value. Potential measures would address avoidable admissions/emergency department visits, mortality, readmissions, ability to obtain care, ability to communicate with clinicians, spending per beneficiary, resource use, and rates of low-value care use. Measures would be calculated based on claims.

MedPAC commissioners were nearly unanimous in their agreement to the idea of repealing MIPS but were not ready to sign off on the proposed replacement.

“I’m really concerned about the burden on physicians, and I’m concerned about some of the outlandish potential rewards for groups under MIPS that can really dissuade them from investing and moving into APMs,” commission member Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution said.

“I think we really have to get rid of MIPS and either replace it with this system, which I think has a lot of merit, or just get rid of it,” said commission member Jack Hoadley, PhD, of Georgetown University in Washington, suggesting MIPS would be “even worse” than the old Sustainable Growth Rate formula over time. It is “clear to me that MIPS is not going to ... get us toward high-value care, it is not going to make clinicians’ lives better, it is not going to make patients’ lives better, and there is a lot of money at stake.”

Commission member Dana Gelb Safran, ScD, chief performance measurement and improvement officer at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts said she did not believe that there would be any value being gained in return for the money given to clinicians who participate in MIPS.

Not everyone was on board with the proposed replacement.

“I am very much in favor of repealing MIPS, but I don’t get the sense that we’ve gotten the replacement model quite right yet” because the proposed system does not do enough to get physicians into advanced APMs, commission member Craig Samitt, MD, chief clinical officer at Anthem, said. “So if a replacement is a voluntary model that would allow us to keep practicing health care the way we’ve been practicing, then that replacement is not a good replacement.”

The American Medical Association declined to evaluate the proposal that was laid forth by staff.

“The AMA welcomes ideas on how to improve Medicare physician payment policies,” AMA President David O. Barbe said in a statement. “We understand that MedPAC’s proposals are a work in progress, so it’s too early to render any judgment.”

Dr. Barbe noted that the AMA recommends that physicians participate in MIPS, even if it is at the lowest level simply to avoid any penalty and continue investing in the infrastructure to participate. The AMA, AGA, and other medical societies also are asking CMS to allow those who are exempt from MIPS participation to be able to opt into the program.

The American Medical Group Association (AMGA), a trade organization representing multispecialty medical groups, however, has criticized the move by CMS to increase the number of clinicians who are exempt from MIPS.

Under the proposed expansion – which would approximately double the number of clinicians who are MIPS exempt – “MIPS no longer provides really any incentive to get to value and in fact it’s a disincentive,” said Chet Speed, AMGA vice president of public policy. “That is one of the realities that MedPAC was dealing with.”

Mr. Speed emphasized that AMGA has not altered its policy on MIPS, which it wants to see enacted for all and has offered its own resources to help with the transition, but “if AMGA were to entertain a new position on MIPS, I think we probably would go with a more simple route, which is to just get rid of MIPS and repurpose the revenues that were in MIPS to APMs. ... We have not agreed upon that policy but that has been discussed internally.”

He added that “AMGA’s membership does look at MIPS as a tool that has really devolved from a value mechanism to a compliance exercise and nothing more.”

As to whether health care provider associations would come together and support the repeal of MIPS, Mr. Speed was hesitant to predict that, even though many have reservations about it, noting that it could be because the broadening of exclusions, which the AMA and most other associations support, effectively remove a lot of their membership from having to participate anyway, leaving the bigger groups such as Mayo, the Cleveland Clinic and Intermountain Healthcare to fight over a much smaller pot of bonus payments, significantly limiting the returns on investments made to be ready for the MIPS transition.

WASHINGTON – In a rare display of a near-immediate consensus, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission agreed that the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System track of the new Quality Payment Program should be scrapped, although commission members are not yet ready to endorse a replacement plan.

MedPAC staff presented its idea of “repeal and replace” less then 10 months into the first reporting year, with staff member David V. Glass noting during an Oct. 6 meeting that “MIPS will not achieve the goal of identifying and rewarding high-value clinicians.”

“Our most basic concern is that measures used in MIPS have not been proven to be associated with high-value care,” Mr. Glass said. “Many of the MIPS quality measures are process measures, assessing only the care a provider delivers within their four walls.”

MedPAC staff proposed a replacement option affecting all clinicians who are not a part of an advanced Alternative Payment Model program. Under their proposal, Medicare would withhold 2% of each clinician’s Medicare payments. Clinicians could earn back that 2% by joining a large reporting entity (either as part of a formal business structure or something like a virtual group); they could elect to join an advanced APM, earning back the 2% and possibly bonus payments; or they could do nothing and lose the 2%.

Measurements in the proposed value program would be similar to those employed by advanced APMs in that they would be focused on population-based measures assessing clinical quality, patient experience, and value. Potential measures would address avoidable admissions/emergency department visits, mortality, readmissions, ability to obtain care, ability to communicate with clinicians, spending per beneficiary, resource use, and rates of low-value care use. Measures would be calculated based on claims.

MedPAC commissioners were nearly unanimous in their agreement to the idea of repealing MIPS but were not ready to sign off on the proposed replacement.

“I’m really concerned about the burden on physicians, and I’m concerned about some of the outlandish potential rewards for groups under MIPS that can really dissuade them from investing and moving into APMs,” commission member Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution said.

“I think we really have to get rid of MIPS and either replace it with this system, which I think has a lot of merit, or just get rid of it,” said commission member Jack Hoadley, PhD, of Georgetown University in Washington, suggesting MIPS would be “even worse” than the old Sustainable Growth Rate formula over time. It is “clear to me that MIPS is not going to ... get us toward high-value care, it is not going to make clinicians’ lives better, it is not going to make patients’ lives better, and there is a lot of money at stake.”

Commission member Dana Gelb Safran, ScD, chief performance measurement and improvement officer at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts said she did not believe that there would be any value being gained in return for the money given to clinicians who participate in MIPS.

Not everyone was on board with the proposed replacement.

“I am very much in favor of repealing MIPS, but I don’t get the sense that we’ve gotten the replacement model quite right yet” because the proposed system does not do enough to get physicians into advanced APMs, commission member Craig Samitt, MD, chief clinical officer at Anthem, said. “So if a replacement is a voluntary model that would allow us to keep practicing health care the way we’ve been practicing, then that replacement is not a good replacement.”

The American Medical Association declined to evaluate the proposal that was laid forth by staff.

“The AMA welcomes ideas on how to improve Medicare physician payment policies,” AMA President David O. Barbe said in a statement. “We understand that MedPAC’s proposals are a work in progress, so it’s too early to render any judgment.”

Dr. Barbe noted that the AMA recommends that physicians participate in MIPS, even if it is at the lowest level simply to avoid any penalty and continue investing in the infrastructure to participate. The AMA, AGA, and other medical societies also are asking CMS to allow those who are exempt from MIPS participation to be able to opt into the program.

The American Medical Group Association (AMGA), a trade organization representing multispecialty medical groups, however, has criticized the move by CMS to increase the number of clinicians who are exempt from MIPS.

Under the proposed expansion – which would approximately double the number of clinicians who are MIPS exempt – “MIPS no longer provides really any incentive to get to value and in fact it’s a disincentive,” said Chet Speed, AMGA vice president of public policy. “That is one of the realities that MedPAC was dealing with.”

Mr. Speed emphasized that AMGA has not altered its policy on MIPS, which it wants to see enacted for all and has offered its own resources to help with the transition, but “if AMGA were to entertain a new position on MIPS, I think we probably would go with a more simple route, which is to just get rid of MIPS and repurpose the revenues that were in MIPS to APMs. ... We have not agreed upon that policy but that has been discussed internally.”

He added that “AMGA’s membership does look at MIPS as a tool that has really devolved from a value mechanism to a compliance exercise and nothing more.”

As to whether health care provider associations would come together and support the repeal of MIPS, Mr. Speed was hesitant to predict that, even though many have reservations about it, noting that it could be because the broadening of exclusions, which the AMA and most other associations support, effectively remove a lot of their membership from having to participate anyway, leaving the bigger groups such as Mayo, the Cleveland Clinic and Intermountain Healthcare to fight over a much smaller pot of bonus payments, significantly limiting the returns on investments made to be ready for the MIPS transition.

AT A MEDPAC MEETING

FDA approves first extended-release steroid injection for OA knee pain

Flexion Therapeutics announced Oct. 6 the approval of Zilretta (triamcinolone acetonide extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only extended-release, intra-articular injection for osteoarthritis knee pain.

Zilretta uses a proprietary microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide to provide pain relief over 12 weeks by prolonging the release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The approval is based on data from a phase 3 clinical trial. The randomized, double-blind study enrolled 484 patients at 37 centers worldwide. The label also includes the results from a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial, which examined blood glucose concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes to show how Zilretta can avoid blood glucose spikes observed with corticosteroid use.

Zilretta is expected to be available in the United States by the end of October.

Flexion Therapeutics announced Oct. 6 the approval of Zilretta (triamcinolone acetonide extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only extended-release, intra-articular injection for osteoarthritis knee pain.

Zilretta uses a proprietary microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide to provide pain relief over 12 weeks by prolonging the release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The approval is based on data from a phase 3 clinical trial. The randomized, double-blind study enrolled 484 patients at 37 centers worldwide. The label also includes the results from a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial, which examined blood glucose concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes to show how Zilretta can avoid blood glucose spikes observed with corticosteroid use.

Zilretta is expected to be available in the United States by the end of October.

Flexion Therapeutics announced Oct. 6 the approval of Zilretta (triamcinolone acetonide extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only extended-release, intra-articular injection for osteoarthritis knee pain.

Zilretta uses a proprietary microsphere-based formulation of triamcinolone acetonide to provide pain relief over 12 weeks by prolonging the release of triamcinolone acetonide inside the synovial fluid. The approval is based on data from a phase 3 clinical trial. The randomized, double-blind study enrolled 484 patients at 37 centers worldwide. The label also includes the results from a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial, which examined blood glucose concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes to show how Zilretta can avoid blood glucose spikes observed with corticosteroid use.

Zilretta is expected to be available in the United States by the end of October.

The electronic elephant

Five years ago, while I still was actively practicing primary care pediatrics, I did a rough calculation that the EHR the practice had purchased was adding an hour to my workday. We were not computer neophytes. This was our third EHR system in 10 years. Not a single minute of that extra time included face-to-face interaction with my patients. In the ensuing years, I have been listening to former colleagues and reading emails from readers of this column. It is clear that my unfortunate experience with our new EHR in 2012 was just a hint at how bad things would get for primary care physicians indentured to EHRs. The short learning curve that was promised has not flattened out, and my rough calculation of an hour at the computer was clearly an underestimate. Most physicians I hear from feel they are spending significantly more than an hour scrolling and clicking.

Although I frequently have used this column to grumble about EHRs, I have been hesitant to launch into a vein-popping tirade because my evidence has been primarily anecdotal. However, a few weeks ago a friend shared a link to a study that provided some startling figures that went beyond my expectation (“Tethered to the EHR: Primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time motion observations,” Ann Fam Med. 2017;15[5]:419-26).

Let that sentence sink in for a moment. How do those numbers compare with your own practice experience? Has anyone in your clinic or hospital taken the time to collect the data? I suspect that your time expenditure on the EHR is similar. Are you or anyone else in your group doing anything more than grumbling to one another about this situation?

Isn’t it time for us to do more than just grouse about this electronic elephant in the room? How many successful businesses would tolerate a situation in which the employees responsible for producing the company’s signature product are allowed to spend half of their time idle? From a purely business perspective, the current EHR/provider interface makes no sense.

Although the cost of physician productivity misdirected to EHRs is probably less than the billions of dollars lost to overpriced medication in this country, this is a topic that deserves a spotlight in ongoing discussions of the Affordable Care Act. At a time when the adequacy of our physician workforce is being questioned, we must take seriously the anecdotal evidence that frustration with EHRs is driving older and experienced physicians into early retirement.

Our patients can be our best allies because most of them don’t like us looking at our computer screens when we should be looking them in the eye … and listening. Like it or not, we now have a president who is a disruptor of the status quo. Maybe it’s time for us to follow his example and begin making some real noise about the personal and financial cost of EHRs. Talk to your legislators, practice administrators, the American Academy of Pediatrics, anyone … even if they don’t seem to be listening.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Five years ago, while I still was actively practicing primary care pediatrics, I did a rough calculation that the EHR the practice had purchased was adding an hour to my workday. We were not computer neophytes. This was our third EHR system in 10 years. Not a single minute of that extra time included face-to-face interaction with my patients. In the ensuing years, I have been listening to former colleagues and reading emails from readers of this column. It is clear that my unfortunate experience with our new EHR in 2012 was just a hint at how bad things would get for primary care physicians indentured to EHRs. The short learning curve that was promised has not flattened out, and my rough calculation of an hour at the computer was clearly an underestimate. Most physicians I hear from feel they are spending significantly more than an hour scrolling and clicking.

Although I frequently have used this column to grumble about EHRs, I have been hesitant to launch into a vein-popping tirade because my evidence has been primarily anecdotal. However, a few weeks ago a friend shared a link to a study that provided some startling figures that went beyond my expectation (“Tethered to the EHR: Primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time motion observations,” Ann Fam Med. 2017;15[5]:419-26).

Let that sentence sink in for a moment. How do those numbers compare with your own practice experience? Has anyone in your clinic or hospital taken the time to collect the data? I suspect that your time expenditure on the EHR is similar. Are you or anyone else in your group doing anything more than grumbling to one another about this situation?

Isn’t it time for us to do more than just grouse about this electronic elephant in the room? How many successful businesses would tolerate a situation in which the employees responsible for producing the company’s signature product are allowed to spend half of their time idle? From a purely business perspective, the current EHR/provider interface makes no sense.

Although the cost of physician productivity misdirected to EHRs is probably less than the billions of dollars lost to overpriced medication in this country, this is a topic that deserves a spotlight in ongoing discussions of the Affordable Care Act. At a time when the adequacy of our physician workforce is being questioned, we must take seriously the anecdotal evidence that frustration with EHRs is driving older and experienced physicians into early retirement.

Our patients can be our best allies because most of them don’t like us looking at our computer screens when we should be looking them in the eye … and listening. Like it or not, we now have a president who is a disruptor of the status quo. Maybe it’s time for us to follow his example and begin making some real noise about the personal and financial cost of EHRs. Talk to your legislators, practice administrators, the American Academy of Pediatrics, anyone … even if they don’t seem to be listening.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Five years ago, while I still was actively practicing primary care pediatrics, I did a rough calculation that the EHR the practice had purchased was adding an hour to my workday. We were not computer neophytes. This was our third EHR system in 10 years. Not a single minute of that extra time included face-to-face interaction with my patients. In the ensuing years, I have been listening to former colleagues and reading emails from readers of this column. It is clear that my unfortunate experience with our new EHR in 2012 was just a hint at how bad things would get for primary care physicians indentured to EHRs. The short learning curve that was promised has not flattened out, and my rough calculation of an hour at the computer was clearly an underestimate. Most physicians I hear from feel they are spending significantly more than an hour scrolling and clicking.

Although I frequently have used this column to grumble about EHRs, I have been hesitant to launch into a vein-popping tirade because my evidence has been primarily anecdotal. However, a few weeks ago a friend shared a link to a study that provided some startling figures that went beyond my expectation (“Tethered to the EHR: Primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time motion observations,” Ann Fam Med. 2017;15[5]:419-26).

Let that sentence sink in for a moment. How do those numbers compare with your own practice experience? Has anyone in your clinic or hospital taken the time to collect the data? I suspect that your time expenditure on the EHR is similar. Are you or anyone else in your group doing anything more than grumbling to one another about this situation?

Isn’t it time for us to do more than just grouse about this electronic elephant in the room? How many successful businesses would tolerate a situation in which the employees responsible for producing the company’s signature product are allowed to spend half of their time idle? From a purely business perspective, the current EHR/provider interface makes no sense.

Although the cost of physician productivity misdirected to EHRs is probably less than the billions of dollars lost to overpriced medication in this country, this is a topic that deserves a spotlight in ongoing discussions of the Affordable Care Act. At a time when the adequacy of our physician workforce is being questioned, we must take seriously the anecdotal evidence that frustration with EHRs is driving older and experienced physicians into early retirement.

Our patients can be our best allies because most of them don’t like us looking at our computer screens when we should be looking them in the eye … and listening. Like it or not, we now have a president who is a disruptor of the status quo. Maybe it’s time for us to follow his example and begin making some real noise about the personal and financial cost of EHRs. Talk to your legislators, practice administrators, the American Academy of Pediatrics, anyone … even if they don’t seem to be listening.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Triple therapy for type 2 diabetes goes beyond glucose control

LISBON – Greater glycemic control and weight reductions were achieved by people with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes who used a fixed dual combination of a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor added to metformin compared with those who used a DPP-4 inhibitor plus metformin in a phase 3b study.

The addition of dapagliflozin/saxagliptin (Qtern, AstraZeneca) to metformin (DAPA/SAXA-MET) resulted in a 1.4% decrease in glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) from baseline to week 26, which was 0.3% more than the 1.1% drop seen when sitagliptin (Januvia, Merck) was added onto metformin (SITA-MET; P less than .008).

“With the triple therapy there was a more profound reduction in glycated hemoglobin,” Stefano Del Prato, MD, professor of endocrinology and metabolism and chief of the section of diabetes at the University of Pisa, Italy, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. “Triple therapy was also associated with significant reductions in fasting plasma glucose and body weight versus sitagliptin added on to metformin,” he said.

Of note, a higher percentage of patients given the triple therapy achieved a target HbA1c of less than 7% compared with those receiving the dual therapy (37% vs. 25%; P = .0034) at 26 weeks, and fasting plasma glucose also fell to a greater extent (–32 mg/dL vs. –11 mg/dL; P less than .0001).

“This study beautifully illustrates to me that when we use SGLT2 inhibitors we shouldn’t be just fixated by the glycemic difference,” Naveed Sattar, MD, professor of cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said from the audience.

Dr. Sattar, who was not involved in the study, suggested that the diabetes community was at the point of a new paradigm: “We could use these drugs to protect the kidneys and the heart,” he suggested. “As a diabetes community we should move beyond glycemia; it’s the other benefits that we should be thinking about when we prescribe these drugs,” he said.

Not everyone was as enthusiastic. One delegate said the study design was “screwy” because two different DPP-4 inhibitors were used. Dr. Del Prato responded, saying that the dual sitagliptin/metformin combination was the comparator arm because it was the most commonly used combination, and saxagliptin was used as it was available in a fixed combination with a DPP4 inhibitor, dapagliflozin.

“Current guidelines recommend addition of a single antidiabetes agent to metformin to achieve and maintain glycemic targets in patients with type 2 diabetes; however, responses to dual therapy are often limited and not persistent in time,” Dr. Del Prato observed. He added that there was already some evidence that triple drug combinations with complementary modes of action “provide increased efficacy for some patients” and that both SGLT2 inhibitors and DPP-4 inhibitors were recommended in combination with metformin.

The aim of the randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study he presented, therefore, was to compare the efficacy and safety of adding the combination of an SGLT2 (dapagliflozin) plus a DPP-4 inhibitor (saxagliptin) versus adding a DPP-4 inhibitor (sitagliptin) alone to metformin “across diverse predefined subpopulations of patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes.”

Patients recruited into the trial had to have been taking a stable dose of metformin of more than 1,500 mg/day for at least 8 weeks at study entry, with a baseline HbA1c of 8%-10.5%, and a fasting plasma glucose of 270 mg/dL or less. Of 861 people screened, 461 were randomized, with 232 receiving daily treatment with the fixed combination of DAPA (10 mg) plus SAXA (5 mg) and 229 receiving sitagliptin (100 mg) added to their existing metformin regimen.