User login

ASCO 2024: Treating Myeloma Just Got More Complicated

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

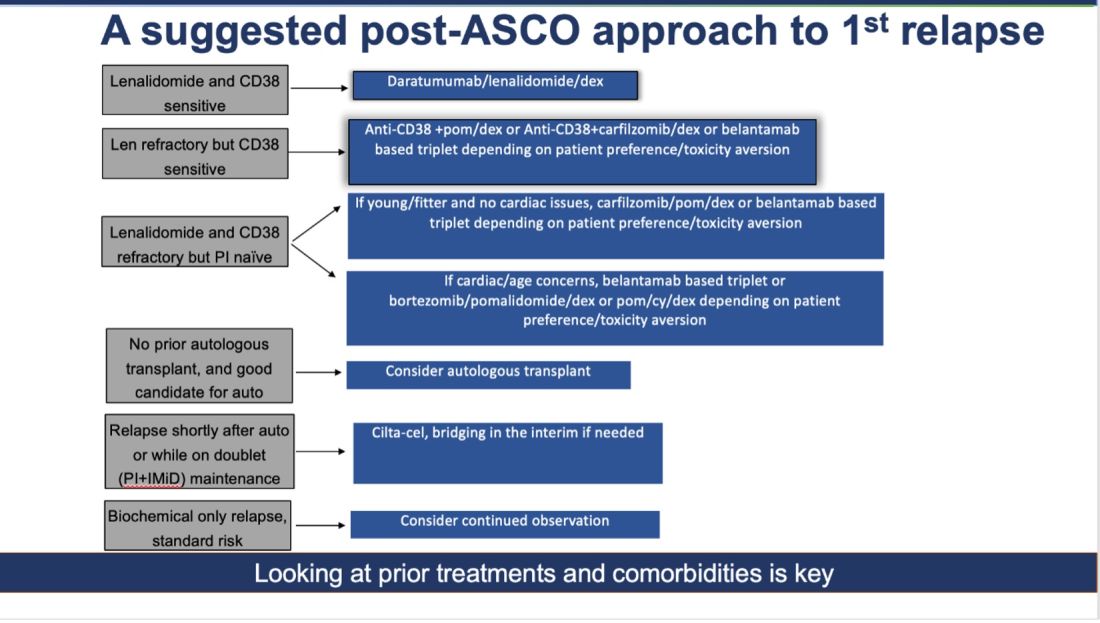

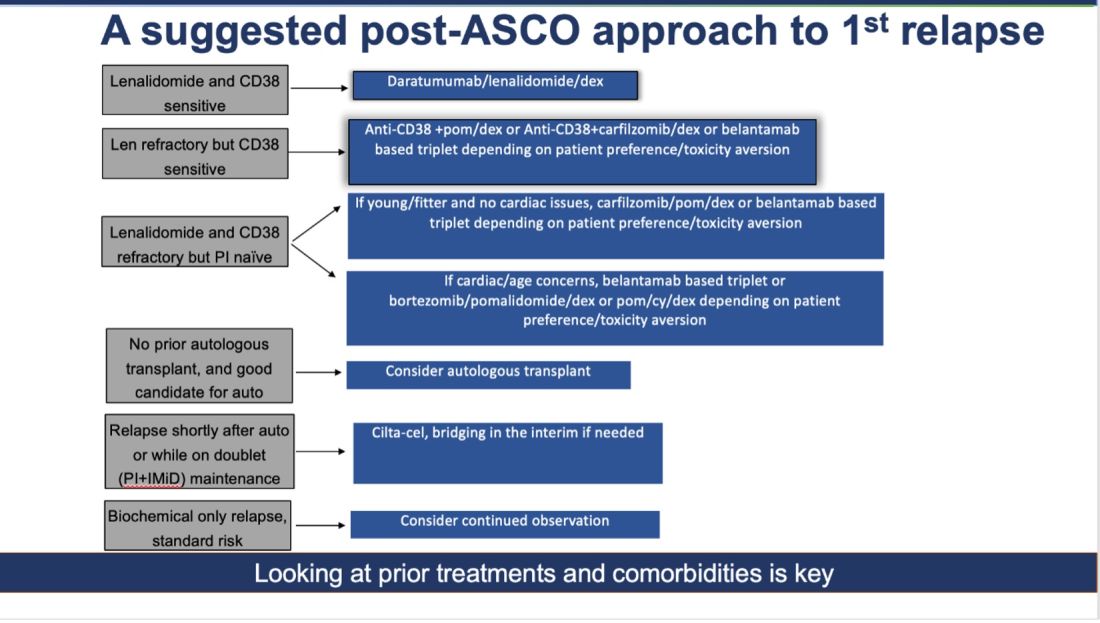

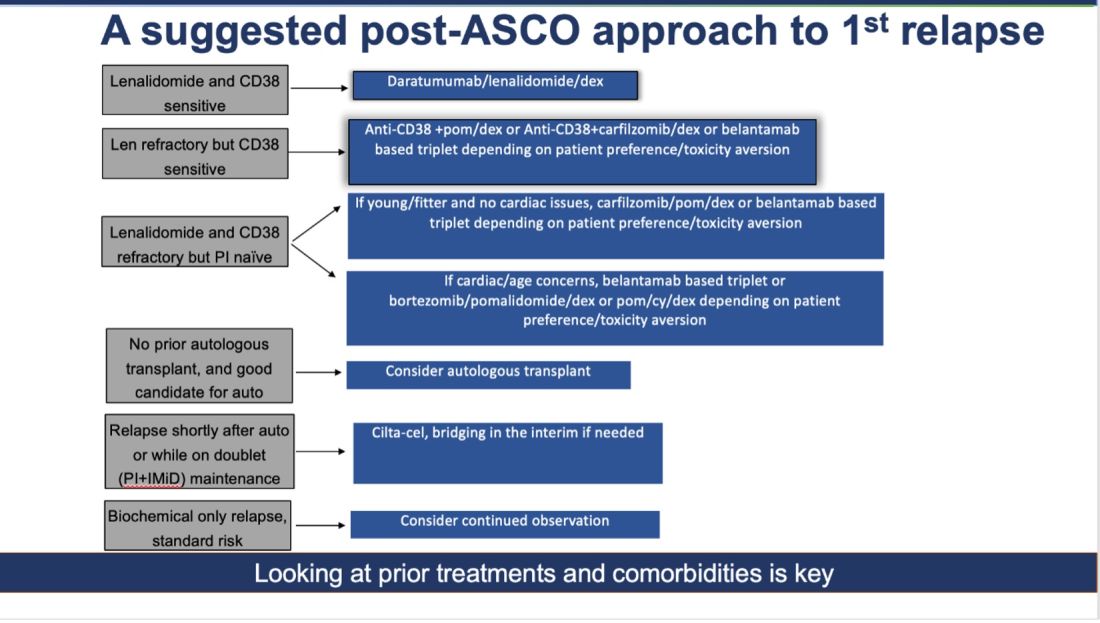

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

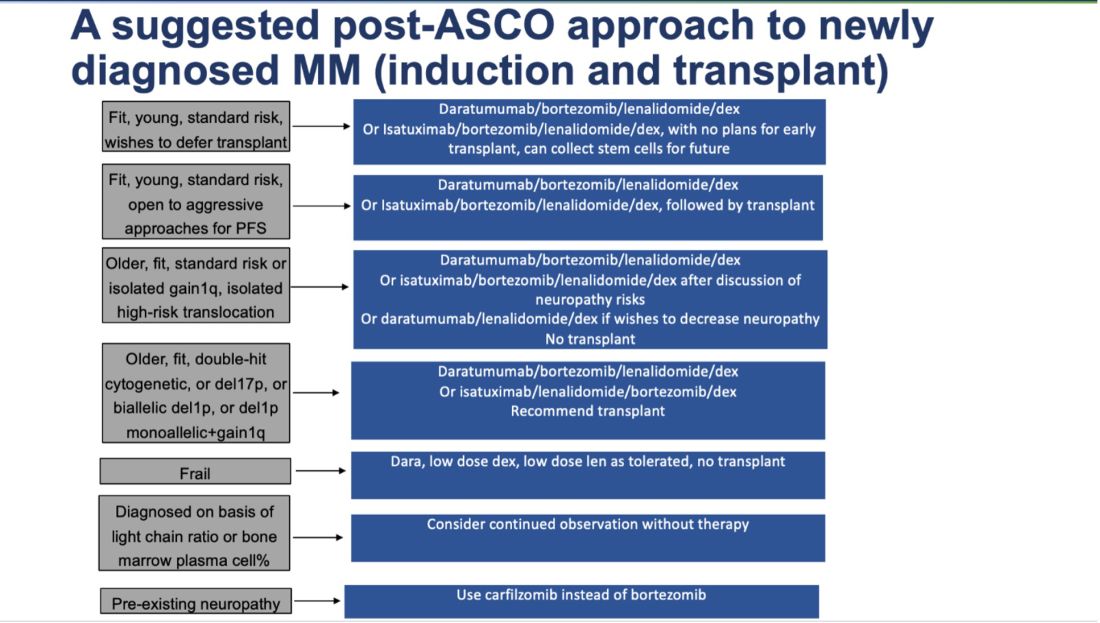

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

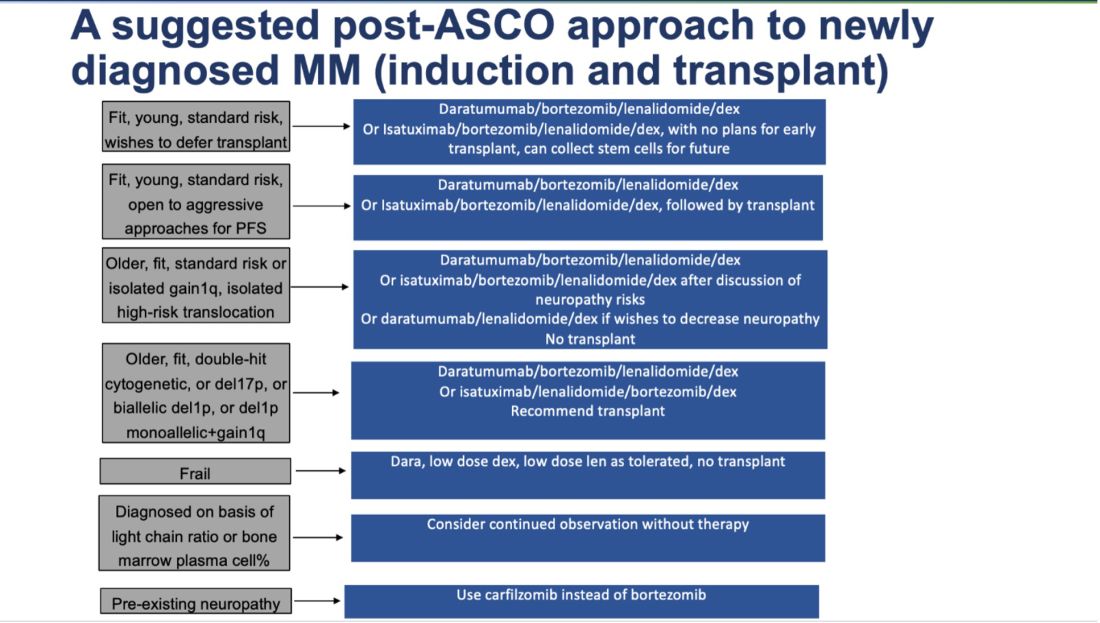

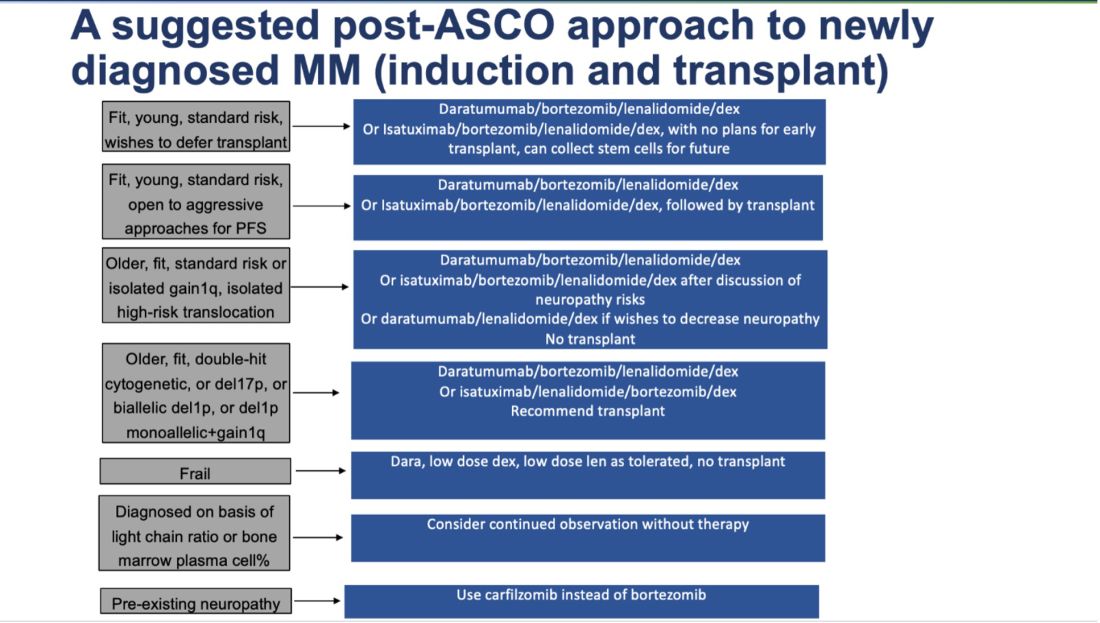

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Cardiovascular Health Becoming a Major Risk Factor for Dementia

That’s according to researchers from University College London (UCL) in the United Kingdom who analyzed 27 papers about dementia that had data collected over more than 70 years. They calculated what share of dementia cases were due to different risk factors. Their findings were recently published in the Lancet Public Health.

Top risk factors for dementia over the years have been hypertension, obesity, diabetes, education, and smoking, according to a news release on the findings. But the prevalence of risk factors has changed over the decades.

Researchers said smoking and education have become less important risk factors because of “population-level interventions,” such as stop-smoking campaigns and compulsory public education. On the other hand, obesity and diabetes rates have increased and become bigger risk factors.

Hypertension remains the greatest risk factor, even though doctors and public health groups are putting more emphasis on managing the condition, the study said.

“Cardiovascular risk factors may have contributed more to dementia risk over time, so these deserve more targeted action for future dementia prevention efforts,” said Naaheed Mukadam, PhD, an associate professor at UCL and the lead author of the study.

Eliminating modifiable risk factors could theoretically prevent 40% of dementia cases, the release said.

The CDC says that an estimated 5.8 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, including 5.6 million people ages 65 and older and about 200,000 under age 65. The UCL release said an estimated 944,000 in the U.K. have dementia.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s according to researchers from University College London (UCL) in the United Kingdom who analyzed 27 papers about dementia that had data collected over more than 70 years. They calculated what share of dementia cases were due to different risk factors. Their findings were recently published in the Lancet Public Health.

Top risk factors for dementia over the years have been hypertension, obesity, diabetes, education, and smoking, according to a news release on the findings. But the prevalence of risk factors has changed over the decades.

Researchers said smoking and education have become less important risk factors because of “population-level interventions,” such as stop-smoking campaigns and compulsory public education. On the other hand, obesity and diabetes rates have increased and become bigger risk factors.

Hypertension remains the greatest risk factor, even though doctors and public health groups are putting more emphasis on managing the condition, the study said.

“Cardiovascular risk factors may have contributed more to dementia risk over time, so these deserve more targeted action for future dementia prevention efforts,” said Naaheed Mukadam, PhD, an associate professor at UCL and the lead author of the study.

Eliminating modifiable risk factors could theoretically prevent 40% of dementia cases, the release said.

The CDC says that an estimated 5.8 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, including 5.6 million people ages 65 and older and about 200,000 under age 65. The UCL release said an estimated 944,000 in the U.K. have dementia.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s according to researchers from University College London (UCL) in the United Kingdom who analyzed 27 papers about dementia that had data collected over more than 70 years. They calculated what share of dementia cases were due to different risk factors. Their findings were recently published in the Lancet Public Health.

Top risk factors for dementia over the years have been hypertension, obesity, diabetes, education, and smoking, according to a news release on the findings. But the prevalence of risk factors has changed over the decades.

Researchers said smoking and education have become less important risk factors because of “population-level interventions,” such as stop-smoking campaigns and compulsory public education. On the other hand, obesity and diabetes rates have increased and become bigger risk factors.

Hypertension remains the greatest risk factor, even though doctors and public health groups are putting more emphasis on managing the condition, the study said.

“Cardiovascular risk factors may have contributed more to dementia risk over time, so these deserve more targeted action for future dementia prevention efforts,” said Naaheed Mukadam, PhD, an associate professor at UCL and the lead author of the study.

Eliminating modifiable risk factors could theoretically prevent 40% of dementia cases, the release said.

The CDC says that an estimated 5.8 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, including 5.6 million people ages 65 and older and about 200,000 under age 65. The UCL release said an estimated 944,000 in the U.K. have dementia.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

Revised Criteria for Alzheimer’s Diagnosis, Staging Released

, including a new biomarker classification system that incorporates fluid and imaging biomarkers as well as an updated disease staging system.

“Plasma markers are here now, and it’s very important to incorporate them into the criteria for diagnosis,” said senior author Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer and medical affairs lead.

The revised criteria are the first updates since 2018.

“Defining diseases biologically, rather than based on syndromic presentation, has long been standard in many areas of medicine — including cancer, heart disease, and diabetes — and is becoming a unifying concept common to all neurodegenerative diseases,” lead author Clifford Jack Jr, MD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release from the Alzheimer’s Association.

“These updates to the diagnostic criteria are needed now because we know more about the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s and we are able to measure those changes,” Dr. Jack added.

The 2024 revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Core Biomarkers Defined

The revised criteria define Alzheimer’s disease as a biologic process that begins with the appearance of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (ADNPC) in the absence of symptoms. Progression of the neuropathologic burden leads to the later appearance and progression of clinical symptoms.

The work group organized Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers into three broad categories: (1) core biomarkers of ADNPC, (2) nonspecific biomarkers that are important in Alzheimer’s disease but are also involved in other brain diseases, and (3) biomarkers of diseases or conditions that commonly coexist with Alzheimer’s disease.

Core Alzheimer’s biomarkers are subdivided into Core 1 and Core 2.

Core 1 biomarkers become abnormal early in the disease course and directly measure either amyloid plaques or phosphorylated tau (p-tau). They include amyloid PET; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta 42/40 ratio, CSF p-tau181/amyloid beta 42 ratio, and CSF total (t)-tau/amyloid beta 42 ratio; and “accurate” plasma biomarkers, such as p-tau217.

“An abnormal Core 1 biomarker result is sufficient to establish a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and to inform clinical decision making [sic] throughout the disease continuum,” the work group wrote.

Core 2 biomarkers become abnormal later in the disease process and are more closely linked with the onset of symptoms. Core 2 biomarkers include tau PET and certain soluble tau fragments associated with tau proteinopathy (eg, MTBR-tau243) but also pT205 and nonphosphorylated mid-region tau fragments.

Core 2 biomarkers, when combined with Core 1, may be used to stage biologic disease severity; abnormal Core 2 biomarkers “increase confidence that Alzheimer’s disease is contributing to symptoms,” the work group noted.

The revised criteria give clinicians “the flexibility to use plasma or PET scans or CSF,” Dr. Carrillo said. “They will have several tools that they can choose from and offer this variety of tools to their patients. We need different tools for different individuals. There will be differences in coverage and access to these diagnostics.”

The revised criteria also include an integrated biologic and clinical staging scheme that acknowledges the fact that common co-pathologies, cognitive reserve, and resistance may modify relationships between clinical and biologic Alzheimer’s disease stages.

Formal Guidelines to Come

The work group noted that currently, the clinical use of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers is intended for the evaluation of symptomatic patients, not cognitively unimpaired individuals.

Disease-targeted therapies have not yet been approved for cognitively unimpaired individuals. For this reason, the work group currently recommends against diagnostic testing in cognitively unimpaired individuals outside the context of observational or therapeutic research studies.

This recommendation would change in the future if disease-targeted therapies that are currently being evaluated in trials demonstrate a benefit in preventing cognitive decline and are approved for use in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, they wrote.

They emphasize that the revised criteria are not intended to provide step-by-step clinical practice guidelines for clinicians. Rather, they provide general principles to inform diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease that reflect current science.

“This is just the beginning,” said Dr. Carrillo. “This is a gathering of the evidence to date and putting it in one place so we can have a consensus and actually a way to test it and make it better as we add new science.”

This also serves as a “springboard” for the Alzheimer’s Association to create formal clinical guidelines. “That will come, hopefully, over the next 12 months. We’ll be working on it, and we hope to have that in 2025,” Dr. Carrillo said.

The revised criteria also emphasize the role of the clinician.

“The biologically based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is meant to assist, rather than supplant, the clinical evaluation of individuals with cognitive impairment,” the work group wrote in a related commentary published online in Nature Medicine.

Recent diagnostics and therapeutic developments “herald a virtuous cycle in which improvements in diagnostic methods enable more sophisticated treatment approaches, which in turn steer advances in diagnostic methods,” they continued. “An unchanging principle, however, is that effective treatment will always rely on the ability to diagnose and stage the biology driving the disease process.”

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Alexander family professorship, GHR Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, Veterans Administration, Life Molecular Imaging, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Gates Foundation, Biogen, C2N Diagnostics, Eisai, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, Roche, National Institute on Aging, Roche/Genentech, BrightFocus Foundation, Hoffmann-La Roche, Novo Nordisk, Toyama, National MS Society, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, and others. A complete list of donors and disclosures is included in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, including a new biomarker classification system that incorporates fluid and imaging biomarkers as well as an updated disease staging system.

“Plasma markers are here now, and it’s very important to incorporate them into the criteria for diagnosis,” said senior author Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer and medical affairs lead.

The revised criteria are the first updates since 2018.

“Defining diseases biologically, rather than based on syndromic presentation, has long been standard in many areas of medicine — including cancer, heart disease, and diabetes — and is becoming a unifying concept common to all neurodegenerative diseases,” lead author Clifford Jack Jr, MD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release from the Alzheimer’s Association.

“These updates to the diagnostic criteria are needed now because we know more about the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s and we are able to measure those changes,” Dr. Jack added.

The 2024 revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Core Biomarkers Defined

The revised criteria define Alzheimer’s disease as a biologic process that begins with the appearance of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (ADNPC) in the absence of symptoms. Progression of the neuropathologic burden leads to the later appearance and progression of clinical symptoms.

The work group organized Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers into three broad categories: (1) core biomarkers of ADNPC, (2) nonspecific biomarkers that are important in Alzheimer’s disease but are also involved in other brain diseases, and (3) biomarkers of diseases or conditions that commonly coexist with Alzheimer’s disease.

Core Alzheimer’s biomarkers are subdivided into Core 1 and Core 2.

Core 1 biomarkers become abnormal early in the disease course and directly measure either amyloid plaques or phosphorylated tau (p-tau). They include amyloid PET; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta 42/40 ratio, CSF p-tau181/amyloid beta 42 ratio, and CSF total (t)-tau/amyloid beta 42 ratio; and “accurate” plasma biomarkers, such as p-tau217.

“An abnormal Core 1 biomarker result is sufficient to establish a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and to inform clinical decision making [sic] throughout the disease continuum,” the work group wrote.

Core 2 biomarkers become abnormal later in the disease process and are more closely linked with the onset of symptoms. Core 2 biomarkers include tau PET and certain soluble tau fragments associated with tau proteinopathy (eg, MTBR-tau243) but also pT205 and nonphosphorylated mid-region tau fragments.

Core 2 biomarkers, when combined with Core 1, may be used to stage biologic disease severity; abnormal Core 2 biomarkers “increase confidence that Alzheimer’s disease is contributing to symptoms,” the work group noted.

The revised criteria give clinicians “the flexibility to use plasma or PET scans or CSF,” Dr. Carrillo said. “They will have several tools that they can choose from and offer this variety of tools to their patients. We need different tools for different individuals. There will be differences in coverage and access to these diagnostics.”

The revised criteria also include an integrated biologic and clinical staging scheme that acknowledges the fact that common co-pathologies, cognitive reserve, and resistance may modify relationships between clinical and biologic Alzheimer’s disease stages.

Formal Guidelines to Come

The work group noted that currently, the clinical use of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers is intended for the evaluation of symptomatic patients, not cognitively unimpaired individuals.

Disease-targeted therapies have not yet been approved for cognitively unimpaired individuals. For this reason, the work group currently recommends against diagnostic testing in cognitively unimpaired individuals outside the context of observational or therapeutic research studies.

This recommendation would change in the future if disease-targeted therapies that are currently being evaluated in trials demonstrate a benefit in preventing cognitive decline and are approved for use in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, they wrote.

They emphasize that the revised criteria are not intended to provide step-by-step clinical practice guidelines for clinicians. Rather, they provide general principles to inform diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease that reflect current science.

“This is just the beginning,” said Dr. Carrillo. “This is a gathering of the evidence to date and putting it in one place so we can have a consensus and actually a way to test it and make it better as we add new science.”

This also serves as a “springboard” for the Alzheimer’s Association to create formal clinical guidelines. “That will come, hopefully, over the next 12 months. We’ll be working on it, and we hope to have that in 2025,” Dr. Carrillo said.

The revised criteria also emphasize the role of the clinician.

“The biologically based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is meant to assist, rather than supplant, the clinical evaluation of individuals with cognitive impairment,” the work group wrote in a related commentary published online in Nature Medicine.

Recent diagnostics and therapeutic developments “herald a virtuous cycle in which improvements in diagnostic methods enable more sophisticated treatment approaches, which in turn steer advances in diagnostic methods,” they continued. “An unchanging principle, however, is that effective treatment will always rely on the ability to diagnose and stage the biology driving the disease process.”

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Alexander family professorship, GHR Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, Veterans Administration, Life Molecular Imaging, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Gates Foundation, Biogen, C2N Diagnostics, Eisai, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, Roche, National Institute on Aging, Roche/Genentech, BrightFocus Foundation, Hoffmann-La Roche, Novo Nordisk, Toyama, National MS Society, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, and others. A complete list of donors and disclosures is included in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, including a new biomarker classification system that incorporates fluid and imaging biomarkers as well as an updated disease staging system.

“Plasma markers are here now, and it’s very important to incorporate them into the criteria for diagnosis,” said senior author Maria C. Carrillo, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer and medical affairs lead.

The revised criteria are the first updates since 2018.

“Defining diseases biologically, rather than based on syndromic presentation, has long been standard in many areas of medicine — including cancer, heart disease, and diabetes — and is becoming a unifying concept common to all neurodegenerative diseases,” lead author Clifford Jack Jr, MD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, said in a news release from the Alzheimer’s Association.

“These updates to the diagnostic criteria are needed now because we know more about the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s and we are able to measure those changes,” Dr. Jack added.

The 2024 revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease were published online in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Core Biomarkers Defined

The revised criteria define Alzheimer’s disease as a biologic process that begins with the appearance of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (ADNPC) in the absence of symptoms. Progression of the neuropathologic burden leads to the later appearance and progression of clinical symptoms.

The work group organized Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers into three broad categories: (1) core biomarkers of ADNPC, (2) nonspecific biomarkers that are important in Alzheimer’s disease but are also involved in other brain diseases, and (3) biomarkers of diseases or conditions that commonly coexist with Alzheimer’s disease.

Core Alzheimer’s biomarkers are subdivided into Core 1 and Core 2.

Core 1 biomarkers become abnormal early in the disease course and directly measure either amyloid plaques or phosphorylated tau (p-tau). They include amyloid PET; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta 42/40 ratio, CSF p-tau181/amyloid beta 42 ratio, and CSF total (t)-tau/amyloid beta 42 ratio; and “accurate” plasma biomarkers, such as p-tau217.

“An abnormal Core 1 biomarker result is sufficient to establish a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and to inform clinical decision making [sic] throughout the disease continuum,” the work group wrote.

Core 2 biomarkers become abnormal later in the disease process and are more closely linked with the onset of symptoms. Core 2 biomarkers include tau PET and certain soluble tau fragments associated with tau proteinopathy (eg, MTBR-tau243) but also pT205 and nonphosphorylated mid-region tau fragments.

Core 2 biomarkers, when combined with Core 1, may be used to stage biologic disease severity; abnormal Core 2 biomarkers “increase confidence that Alzheimer’s disease is contributing to symptoms,” the work group noted.

The revised criteria give clinicians “the flexibility to use plasma or PET scans or CSF,” Dr. Carrillo said. “They will have several tools that they can choose from and offer this variety of tools to their patients. We need different tools for different individuals. There will be differences in coverage and access to these diagnostics.”

The revised criteria also include an integrated biologic and clinical staging scheme that acknowledges the fact that common co-pathologies, cognitive reserve, and resistance may modify relationships between clinical and biologic Alzheimer’s disease stages.

Formal Guidelines to Come

The work group noted that currently, the clinical use of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers is intended for the evaluation of symptomatic patients, not cognitively unimpaired individuals.

Disease-targeted therapies have not yet been approved for cognitively unimpaired individuals. For this reason, the work group currently recommends against diagnostic testing in cognitively unimpaired individuals outside the context of observational or therapeutic research studies.

This recommendation would change in the future if disease-targeted therapies that are currently being evaluated in trials demonstrate a benefit in preventing cognitive decline and are approved for use in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, they wrote.

They emphasize that the revised criteria are not intended to provide step-by-step clinical practice guidelines for clinicians. Rather, they provide general principles to inform diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease that reflect current science.

“This is just the beginning,” said Dr. Carrillo. “This is a gathering of the evidence to date and putting it in one place so we can have a consensus and actually a way to test it and make it better as we add new science.”

This also serves as a “springboard” for the Alzheimer’s Association to create formal clinical guidelines. “That will come, hopefully, over the next 12 months. We’ll be working on it, and we hope to have that in 2025,” Dr. Carrillo said.

The revised criteria also emphasize the role of the clinician.

“The biologically based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is meant to assist, rather than supplant, the clinical evaluation of individuals with cognitive impairment,” the work group wrote in a related commentary published online in Nature Medicine.

Recent diagnostics and therapeutic developments “herald a virtuous cycle in which improvements in diagnostic methods enable more sophisticated treatment approaches, which in turn steer advances in diagnostic methods,” they continued. “An unchanging principle, however, is that effective treatment will always rely on the ability to diagnose and stage the biology driving the disease process.”

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Alexander family professorship, GHR Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, Veterans Administration, Life Molecular Imaging, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Gates Foundation, Biogen, C2N Diagnostics, Eisai, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, Roche, National Institute on Aging, Roche/Genentech, BrightFocus Foundation, Hoffmann-La Roche, Novo Nordisk, Toyama, National MS Society, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, and others. A complete list of donors and disclosures is included in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ALZHEIMER’S & DEMENTIA

Common Cognitive Test Falls Short for Concussion Diagnosis

, a new study showed.

Investigators found that almost half of athletes diagnosed with a concussion tested normally on the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5), the recommended tool for measuring cognitive skills in concussion evaluations. The most accurate measure of concussion was symptoms reported by the athletes.

“If you don’t do well on the cognitive exam, it suggests you have a concussion. But many people who are concussed do fine on the exam,” lead author Kimberly Harmon, MD, professor of family medicine and section head of sports medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in a news release.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Introduced in 2004, the SCAT was created to standardize the collection of information clinicians use to diagnose concussion, including evaluation of symptoms, orientation, and balance. It also uses a 10-word list to assess immediate memory and delayed recall.

Dr. Harmon’s own experiences as a team physician led her to wonder about the accuracy of the cognitive screening portion of the SCAT. She saw that “some people were concussed, and they did well on the recall test. Some people weren’t concussed, and they didn’t do well. So I thought we should study it,” she said.

Investigators compared 92 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1 athletes who had sustained a concussion between 2020 and 2022 and had a concussion evaluation within 48 hours to 92 matched nonconcussed teammates (overall cohort, 52% men). Most concussions occurred in those who played football, followed by volleyball.

All athletes had previously completed NCAA-required baseline concussion screenings. Participants completed the SCAT5 screening test within 2 weeks of the incident concussion.

No significant differences were found between the baseline scores of athletes with and without concussion. Moreover, responses on the word recall section of the SCAT5 held little predictive value for concussion.

Nearly half (45%) of athletes with concussion performed at or even above their baseline cognitive report, which the authors said highlights the limitations of the cognitive components of SCAT5.

The most accurate predictor of concussion was participants’ responses to questions about their symptoms.

“If you get hit in the head and go to the sideline and say, ‘I have a headache, I’m dizzy, I don’t feel right,’ I can say with pretty good assurance that you have a concussion,” Dr. Harmon continued. “I don’t need to do any testing.”

Unfortunately, the problem is “that some athletes don’t want to come out. They don’t report their symptoms or may not recognize their symptoms. So then you need an objective, accurate test to tell you whether you can safely put the athlete back on the field. We don’t have that right now.”

The study did not control for concussion history, and the all–Division 1 cohort means the findings may not be generalizable to other athletes.

Nevertheless, investigators said the study “affirms that reported symptoms are the most sensitive indicator of concussion, and there are limitations to the objective cognitive testing included in the SCAT.” They concluded that concussion “remains a clinical diagnosis that should be based on a thorough review of signs, symptoms, and clinical findings.”

This study was funded in part by donations from University of Washington alumni Jack and Luellen Cherneski and the Chisholm Foundation. Dr. Harmon reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study showed.

Investigators found that almost half of athletes diagnosed with a concussion tested normally on the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5), the recommended tool for measuring cognitive skills in concussion evaluations. The most accurate measure of concussion was symptoms reported by the athletes.

“If you don’t do well on the cognitive exam, it suggests you have a concussion. But many people who are concussed do fine on the exam,” lead author Kimberly Harmon, MD, professor of family medicine and section head of sports medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in a news release.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Introduced in 2004, the SCAT was created to standardize the collection of information clinicians use to diagnose concussion, including evaluation of symptoms, orientation, and balance. It also uses a 10-word list to assess immediate memory and delayed recall.

Dr. Harmon’s own experiences as a team physician led her to wonder about the accuracy of the cognitive screening portion of the SCAT. She saw that “some people were concussed, and they did well on the recall test. Some people weren’t concussed, and they didn’t do well. So I thought we should study it,” she said.

Investigators compared 92 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1 athletes who had sustained a concussion between 2020 and 2022 and had a concussion evaluation within 48 hours to 92 matched nonconcussed teammates (overall cohort, 52% men). Most concussions occurred in those who played football, followed by volleyball.

All athletes had previously completed NCAA-required baseline concussion screenings. Participants completed the SCAT5 screening test within 2 weeks of the incident concussion.

No significant differences were found between the baseline scores of athletes with and without concussion. Moreover, responses on the word recall section of the SCAT5 held little predictive value for concussion.

Nearly half (45%) of athletes with concussion performed at or even above their baseline cognitive report, which the authors said highlights the limitations of the cognitive components of SCAT5.

The most accurate predictor of concussion was participants’ responses to questions about their symptoms.

“If you get hit in the head and go to the sideline and say, ‘I have a headache, I’m dizzy, I don’t feel right,’ I can say with pretty good assurance that you have a concussion,” Dr. Harmon continued. “I don’t need to do any testing.”

Unfortunately, the problem is “that some athletes don’t want to come out. They don’t report their symptoms or may not recognize their symptoms. So then you need an objective, accurate test to tell you whether you can safely put the athlete back on the field. We don’t have that right now.”

The study did not control for concussion history, and the all–Division 1 cohort means the findings may not be generalizable to other athletes.

Nevertheless, investigators said the study “affirms that reported symptoms are the most sensitive indicator of concussion, and there are limitations to the objective cognitive testing included in the SCAT.” They concluded that concussion “remains a clinical diagnosis that should be based on a thorough review of signs, symptoms, and clinical findings.”

This study was funded in part by donations from University of Washington alumni Jack and Luellen Cherneski and the Chisholm Foundation. Dr. Harmon reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study showed.

Investigators found that almost half of athletes diagnosed with a concussion tested normally on the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5), the recommended tool for measuring cognitive skills in concussion evaluations. The most accurate measure of concussion was symptoms reported by the athletes.

“If you don’t do well on the cognitive exam, it suggests you have a concussion. But many people who are concussed do fine on the exam,” lead author Kimberly Harmon, MD, professor of family medicine and section head of sports medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in a news release.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Introduced in 2004, the SCAT was created to standardize the collection of information clinicians use to diagnose concussion, including evaluation of symptoms, orientation, and balance. It also uses a 10-word list to assess immediate memory and delayed recall.

Dr. Harmon’s own experiences as a team physician led her to wonder about the accuracy of the cognitive screening portion of the SCAT. She saw that “some people were concussed, and they did well on the recall test. Some people weren’t concussed, and they didn’t do well. So I thought we should study it,” she said.

Investigators compared 92 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1 athletes who had sustained a concussion between 2020 and 2022 and had a concussion evaluation within 48 hours to 92 matched nonconcussed teammates (overall cohort, 52% men). Most concussions occurred in those who played football, followed by volleyball.

All athletes had previously completed NCAA-required baseline concussion screenings. Participants completed the SCAT5 screening test within 2 weeks of the incident concussion.

No significant differences were found between the baseline scores of athletes with and without concussion. Moreover, responses on the word recall section of the SCAT5 held little predictive value for concussion.

Nearly half (45%) of athletes with concussion performed at or even above their baseline cognitive report, which the authors said highlights the limitations of the cognitive components of SCAT5.

The most accurate predictor of concussion was participants’ responses to questions about their symptoms.

“If you get hit in the head and go to the sideline and say, ‘I have a headache, I’m dizzy, I don’t feel right,’ I can say with pretty good assurance that you have a concussion,” Dr. Harmon continued. “I don’t need to do any testing.”

Unfortunately, the problem is “that some athletes don’t want to come out. They don’t report their symptoms or may not recognize their symptoms. So then you need an objective, accurate test to tell you whether you can safely put the athlete back on the field. We don’t have that right now.”

The study did not control for concussion history, and the all–Division 1 cohort means the findings may not be generalizable to other athletes.

Nevertheless, investigators said the study “affirms that reported symptoms are the most sensitive indicator of concussion, and there are limitations to the objective cognitive testing included in the SCAT.” They concluded that concussion “remains a clinical diagnosis that should be based on a thorough review of signs, symptoms, and clinical findings.”

This study was funded in part by donations from University of Washington alumni Jack and Luellen Cherneski and the Chisholm Foundation. Dr. Harmon reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Form of B12 Deficiency Affecting the Central Nervous System May Be New Autoimmune Disease

Discovered while studying a puzzling case of one patient with inexplicable neurological systems, the same autoantibody was detected in a small percentage of healthy individuals and was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

“I didn’t think this single investigation was going to yield a broader phenomenon with other patients,” lead author John V. Pluvinage, MD, PhD, a neurology resident at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview. “It started as an N-of-one study just based on scientific curiosity.”

“It’s a beautifully done study,” added Betty Diamond, MD, director of the Institute of Molecular Medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, commenting on the research. It uncovers “yet another example of a disease where antibodies getting into the brain are the problem.”

The research was published in Science Translational Medicine.

The Patient

The investigation began in 2014 with a 67-year-old woman presenting with difficulty speaking, ataxia, and tremor. Her blood tests showed no signs of B12 deficiency, and testing for known autoantibodies came back negative.

Solving this mystery required a more exhaustive approach. The patient enrolled in a research study focused on identifying novel autoantibodies in suspected neuroinflammatory disease, using a screening technology called phage immunoprecipitation sequencing.

“We adapted this technology to screen for autoantibodies in an unbiased manner by displaying every peptide across the human proteome and then mixing those peptides with patient antibodies in order to figure out what the antibodies are binding to,” explained Dr. Pluvinage.

Using this method, he and colleagues discovered that this woman had autoantibodies that target CD320 — a receptor important in the cellular uptake of B12. While her blood tests were normal, B12 in the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was “nearly undetectable,” Dr. Pluvinage said. Using an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the researchers determined that anti-CD320 impaired the transport of B12 across the BBB by targeting receptors on the cell surface.

Treating the patient with a combination of immunosuppressant medication and high-dose B12 supplementation increased B12 levels in the patient’s CSF and improved clinical symptoms.

Identifying More Cases

Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues tested the 254 other individuals enrolled in the neuroinflammatory disease study and identified seven participants with CSF anti-CD320 autoantibodies — four of whom had low B12 in the CSF.

In a group of healthy controls, anti-CD320 seropositivity was 6%, similar to the positivity rate in 132 paired serum and CSF samples from a cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis (5.7%). In this group of patients with multiple sclerosis, anti-CD320 presence in the blood was highly predictive of high levels of CSF methylmalonic acid, a metabolic marker of B12 deficiency.

Researchers also screened for anti-CD320 seropositivity in 408 patients with non-neurologic SLE and 28 patients with neuropsychiatric SLE and found that the autoantibody was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neurologic symptoms (21.4%) compared with in those with non-neurologic SLE (5.6%).

“The clinical relevance of anti-CD320 in healthy controls remains uncertain,” the authors wrote. However, it is not uncommon to have healthy patients with known autoantibodies.

“There are always people who have autoantibodies who don’t get disease, and why that is we don’t know,” said Dr. Diamond. Some individuals may develop clinical symptoms later, or there may be other reasons why they are protected against disease.

Pluvinage is eager to follow some seropositive healthy individuals to track their neurologic health overtime, to see if the presence of anti-CD320 “alters their neurologic trajectories.”

Alternative Pathways

Lastly, Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues set out to explain why patients with anti-CD320 in their blood did not show any signs of B12 deficiency. They hypothesized that another receptor may be compensating and still allowing blood cells to take up B12. Using CRISPR screening, the team identified the low-density lipoprotein receptor as an alternative pathway to B12 uptake.

“These findings suggest a model in which anti-CD320 impairs transport of B12 across the BBB, leading to autoimmune B12 central deficiency (ABCD) with varied neurologic manifestations but sparing peripheral manifestations of B12 deficiency,” the authors wrote.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Department of Defense, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Laboratory for Cell Analysis Shared Resource Facility, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Valhalla Foundation, and the Westridge Foundation. Dr. Pluvinage is a co-inventor on a patent application related to this work. Dr. Diamond had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Discovered while studying a puzzling case of one patient with inexplicable neurological systems, the same autoantibody was detected in a small percentage of healthy individuals and was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

“I didn’t think this single investigation was going to yield a broader phenomenon with other patients,” lead author John V. Pluvinage, MD, PhD, a neurology resident at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview. “It started as an N-of-one study just based on scientific curiosity.”

“It’s a beautifully done study,” added Betty Diamond, MD, director of the Institute of Molecular Medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, commenting on the research. It uncovers “yet another example of a disease where antibodies getting into the brain are the problem.”

The research was published in Science Translational Medicine.

The Patient

The investigation began in 2014 with a 67-year-old woman presenting with difficulty speaking, ataxia, and tremor. Her blood tests showed no signs of B12 deficiency, and testing for known autoantibodies came back negative.

Solving this mystery required a more exhaustive approach. The patient enrolled in a research study focused on identifying novel autoantibodies in suspected neuroinflammatory disease, using a screening technology called phage immunoprecipitation sequencing.

“We adapted this technology to screen for autoantibodies in an unbiased manner by displaying every peptide across the human proteome and then mixing those peptides with patient antibodies in order to figure out what the antibodies are binding to,” explained Dr. Pluvinage.

Using this method, he and colleagues discovered that this woman had autoantibodies that target CD320 — a receptor important in the cellular uptake of B12. While her blood tests were normal, B12 in the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was “nearly undetectable,” Dr. Pluvinage said. Using an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the researchers determined that anti-CD320 impaired the transport of B12 across the BBB by targeting receptors on the cell surface.

Treating the patient with a combination of immunosuppressant medication and high-dose B12 supplementation increased B12 levels in the patient’s CSF and improved clinical symptoms.

Identifying More Cases

Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues tested the 254 other individuals enrolled in the neuroinflammatory disease study and identified seven participants with CSF anti-CD320 autoantibodies — four of whom had low B12 in the CSF.

In a group of healthy controls, anti-CD320 seropositivity was 6%, similar to the positivity rate in 132 paired serum and CSF samples from a cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis (5.7%). In this group of patients with multiple sclerosis, anti-CD320 presence in the blood was highly predictive of high levels of CSF methylmalonic acid, a metabolic marker of B12 deficiency.

Researchers also screened for anti-CD320 seropositivity in 408 patients with non-neurologic SLE and 28 patients with neuropsychiatric SLE and found that the autoantibody was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neurologic symptoms (21.4%) compared with in those with non-neurologic SLE (5.6%).

“The clinical relevance of anti-CD320 in healthy controls remains uncertain,” the authors wrote. However, it is not uncommon to have healthy patients with known autoantibodies.

“There are always people who have autoantibodies who don’t get disease, and why that is we don’t know,” said Dr. Diamond. Some individuals may develop clinical symptoms later, or there may be other reasons why they are protected against disease.

Pluvinage is eager to follow some seropositive healthy individuals to track their neurologic health overtime, to see if the presence of anti-CD320 “alters their neurologic trajectories.”

Alternative Pathways

Lastly, Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues set out to explain why patients with anti-CD320 in their blood did not show any signs of B12 deficiency. They hypothesized that another receptor may be compensating and still allowing blood cells to take up B12. Using CRISPR screening, the team identified the low-density lipoprotein receptor as an alternative pathway to B12 uptake.

“These findings suggest a model in which anti-CD320 impairs transport of B12 across the BBB, leading to autoimmune B12 central deficiency (ABCD) with varied neurologic manifestations but sparing peripheral manifestations of B12 deficiency,” the authors wrote.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Department of Defense, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Laboratory for Cell Analysis Shared Resource Facility, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Valhalla Foundation, and the Westridge Foundation. Dr. Pluvinage is a co-inventor on a patent application related to this work. Dr. Diamond had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Discovered while studying a puzzling case of one patient with inexplicable neurological systems, the same autoantibody was detected in a small percentage of healthy individuals and was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

“I didn’t think this single investigation was going to yield a broader phenomenon with other patients,” lead author John V. Pluvinage, MD, PhD, a neurology resident at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview. “It started as an N-of-one study just based on scientific curiosity.”

“It’s a beautifully done study,” added Betty Diamond, MD, director of the Institute of Molecular Medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, commenting on the research. It uncovers “yet another example of a disease where antibodies getting into the brain are the problem.”

The research was published in Science Translational Medicine.

The Patient

The investigation began in 2014 with a 67-year-old woman presenting with difficulty speaking, ataxia, and tremor. Her blood tests showed no signs of B12 deficiency, and testing for known autoantibodies came back negative.

Solving this mystery required a more exhaustive approach. The patient enrolled in a research study focused on identifying novel autoantibodies in suspected neuroinflammatory disease, using a screening technology called phage immunoprecipitation sequencing.

“We adapted this technology to screen for autoantibodies in an unbiased manner by displaying every peptide across the human proteome and then mixing those peptides with patient antibodies in order to figure out what the antibodies are binding to,” explained Dr. Pluvinage.

Using this method, he and colleagues discovered that this woman had autoantibodies that target CD320 — a receptor important in the cellular uptake of B12. While her blood tests were normal, B12 in the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was “nearly undetectable,” Dr. Pluvinage said. Using an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the researchers determined that anti-CD320 impaired the transport of B12 across the BBB by targeting receptors on the cell surface.

Treating the patient with a combination of immunosuppressant medication and high-dose B12 supplementation increased B12 levels in the patient’s CSF and improved clinical symptoms.

Identifying More Cases

Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues tested the 254 other individuals enrolled in the neuroinflammatory disease study and identified seven participants with CSF anti-CD320 autoantibodies — four of whom had low B12 in the CSF.

In a group of healthy controls, anti-CD320 seropositivity was 6%, similar to the positivity rate in 132 paired serum and CSF samples from a cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis (5.7%). In this group of patients with multiple sclerosis, anti-CD320 presence in the blood was highly predictive of high levels of CSF methylmalonic acid, a metabolic marker of B12 deficiency.

Researchers also screened for anti-CD320 seropositivity in 408 patients with non-neurologic SLE and 28 patients with neuropsychiatric SLE and found that the autoantibody was nearly four times as prevalent in patients with neurologic symptoms (21.4%) compared with in those with non-neurologic SLE (5.6%).

“The clinical relevance of anti-CD320 in healthy controls remains uncertain,” the authors wrote. However, it is not uncommon to have healthy patients with known autoantibodies.

“There are always people who have autoantibodies who don’t get disease, and why that is we don’t know,” said Dr. Diamond. Some individuals may develop clinical symptoms later, or there may be other reasons why they are protected against disease.

Pluvinage is eager to follow some seropositive healthy individuals to track their neurologic health overtime, to see if the presence of anti-CD320 “alters their neurologic trajectories.”

Alternative Pathways

Lastly, Dr. Pluvinage and colleagues set out to explain why patients with anti-CD320 in their blood did not show any signs of B12 deficiency. They hypothesized that another receptor may be compensating and still allowing blood cells to take up B12. Using CRISPR screening, the team identified the low-density lipoprotein receptor as an alternative pathway to B12 uptake.

“These findings suggest a model in which anti-CD320 impairs transport of B12 across the BBB, leading to autoimmune B12 central deficiency (ABCD) with varied neurologic manifestations but sparing peripheral manifestations of B12 deficiency,” the authors wrote.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Department of Defense, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Laboratory for Cell Analysis Shared Resource Facility, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Valhalla Foundation, and the Westridge Foundation. Dr. Pluvinage is a co-inventor on a patent application related to this work. Dr. Diamond had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Is Screen Time to Blame for Rising Rates of Myopia in Children?

TOPLINE:

More time spent exposed to screens is associated with a higher risk for myopia in children and adolescents; the use of computers and televisions appears to have the most significant effects on eye health.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 19 studies involving 102,360 children and adolescents to assess the association between screen time and myopia.

- Data were collected from studies published before June 1, 2023, in three databases: PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science.

- Screen time was categorized by device type, including computers, televisions, and smartphones, and analyzed using random or fixed-effect models.

- The analysis included both cohort and cross-sectional studies.

TAKEAWAY:

- High exposure to screen time was significantly associated with myopia in both cross-sectional (odds ratio [OR], 2.24; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.47-3.42) and cohort studies (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 2.07-2.76).

- In cohort studies, each extra hour per day spent using screens increased the risk for myopia by 7% (95% CI, 1.01-1.13).

- Subgroup analyses revealed significant associations between myopia and screen time on computers (OR, 8.19; 95% CI, 4.78-14.04) and televisions (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.02-2.10), whereas time spent using smartphones was not significantly associated with myopia.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the development of technology and GDP [gross domestic product], educational pressure may lead students to use screen devices such as smartphones and computers for long periods of time to learn online courses, receive additional tutoring or practice, and increase the incidence of myopia,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Zhiqiang Zong of Anhui Medical University in Hefei, China. It was published online in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The majority of the studies included were cross-sectional, which cannot establish causality. High heterogeneity was found among the included studies, possibly due to differences in research design, population characteristics, and exposure levels. Some studies did not adjust for important confounding factors such as outdoor activities.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Educational Commission of Anhui Province of China, Research Fund of Anhui Institute of Translational Medicine, and National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

More time spent exposed to screens is associated with a higher risk for myopia in children and adolescents; the use of computers and televisions appears to have the most significant effects on eye health.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 19 studies involving 102,360 children and adolescents to assess the association between screen time and myopia.

- Data were collected from studies published before June 1, 2023, in three databases: PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science.

- Screen time was categorized by device type, including computers, televisions, and smartphones, and analyzed using random or fixed-effect models.

- The analysis included both cohort and cross-sectional studies.

TAKEAWAY:

- High exposure to screen time was significantly associated with myopia in both cross-sectional (odds ratio [OR], 2.24; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.47-3.42) and cohort studies (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 2.07-2.76).

- In cohort studies, each extra hour per day spent using screens increased the risk for myopia by 7% (95% CI, 1.01-1.13).

- Subgroup analyses revealed significant associations between myopia and screen time on computers (OR, 8.19; 95% CI, 4.78-14.04) and televisions (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.02-2.10), whereas time spent using smartphones was not significantly associated with myopia.

IN PRACTICE: