User login

Monthly or Quarterly Fremanezumab Effective Against Episodic Migraine

Key clinical point: Administration of monthly or quarterly fremanezumab reduced acute medication use and alleviated migraine-associated symptoms in patients with episodic migraine (EM).

Major findings: Fremanezumab, administered monthly vs placebo significantly reduced the acute medication use for headaches (–2.98 vs –0.01; P < .001) and number of days with nausea or vomiting (–1.59 vs –0.66; P = .023) in the first month after initial dosage, with continued benefits till months 2 and 3. Fremanezumab, administered quarterly, also yielded promising outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from an exploratory endpoint analysis of a phase 2b/3 randomized trial including patients with EM who were randomly assigned to receive either monthly fremanezumab (n = 121), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 119), or placebo (n = 117) in monthly intervals.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Five authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Source: Tatsumoto M, Ishida M, Iba K, et al. Effects of fremanezumab on migraine-associated symptoms and medication use in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine: Exploratory endpoint analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14810 Source

Key clinical point: Administration of monthly or quarterly fremanezumab reduced acute medication use and alleviated migraine-associated symptoms in patients with episodic migraine (EM).

Major findings: Fremanezumab, administered monthly vs placebo significantly reduced the acute medication use for headaches (–2.98 vs –0.01; P < .001) and number of days with nausea or vomiting (–1.59 vs –0.66; P = .023) in the first month after initial dosage, with continued benefits till months 2 and 3. Fremanezumab, administered quarterly, also yielded promising outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from an exploratory endpoint analysis of a phase 2b/3 randomized trial including patients with EM who were randomly assigned to receive either monthly fremanezumab (n = 121), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 119), or placebo (n = 117) in monthly intervals.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Five authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Source: Tatsumoto M, Ishida M, Iba K, et al. Effects of fremanezumab on migraine-associated symptoms and medication use in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine: Exploratory endpoint analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14810 Source

Key clinical point: Administration of monthly or quarterly fremanezumab reduced acute medication use and alleviated migraine-associated symptoms in patients with episodic migraine (EM).

Major findings: Fremanezumab, administered monthly vs placebo significantly reduced the acute medication use for headaches (–2.98 vs –0.01; P < .001) and number of days with nausea or vomiting (–1.59 vs –0.66; P = .023) in the first month after initial dosage, with continued benefits till months 2 and 3. Fremanezumab, administered quarterly, also yielded promising outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from an exploratory endpoint analysis of a phase 2b/3 randomized trial including patients with EM who were randomly assigned to receive either monthly fremanezumab (n = 121), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 119), or placebo (n = 117) in monthly intervals.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Five authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Source: Tatsumoto M, Ishida M, Iba K, et al. Effects of fremanezumab on migraine-associated symptoms and medication use in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine: Exploratory endpoint analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14810 Source

Eicosapentaenoic Acid Is an Effective Adjunct Therapy for Chronic Migraine

Key clinical point: Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), used with standard prophylactic pharmacotherapy, significantly reduced migraine headache days (MHD) and migraine attacks in patients with chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: The score relating to headache impact was significantly lower in the EPA vs placebo group at weeks 4 (P = .017) and 8 (P = .042). At 8 weeks, EPA treatment led to a greater reduction in mean MHD (−9.76 vs −4.60; P < .001) and mean number of attacks per month (3 vs 4; P = .012) than placebo. In the EPA group, only three patients experienced nausea and gastrointestinal upset.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 60 adult patients with CM who received 1000 mg EPA or placebo twice daily for 8 weeks and continued their first-line preventive pharmacotherapy throughout the trial.

Disclosure: The study was supported by the research committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mohammadnezhad G, Assarzadegan F, Koosha M, Esmaily H. Eicosapentaenoic acid versus placebo as adjunctive therapy in chronic migraine: A randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14808 Source

Key clinical point: Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), used with standard prophylactic pharmacotherapy, significantly reduced migraine headache days (MHD) and migraine attacks in patients with chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: The score relating to headache impact was significantly lower in the EPA vs placebo group at weeks 4 (P = .017) and 8 (P = .042). At 8 weeks, EPA treatment led to a greater reduction in mean MHD (−9.76 vs −4.60; P < .001) and mean number of attacks per month (3 vs 4; P = .012) than placebo. In the EPA group, only three patients experienced nausea and gastrointestinal upset.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 60 adult patients with CM who received 1000 mg EPA or placebo twice daily for 8 weeks and continued their first-line preventive pharmacotherapy throughout the trial.

Disclosure: The study was supported by the research committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mohammadnezhad G, Assarzadegan F, Koosha M, Esmaily H. Eicosapentaenoic acid versus placebo as adjunctive therapy in chronic migraine: A randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14808 Source

Key clinical point: Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), used with standard prophylactic pharmacotherapy, significantly reduced migraine headache days (MHD) and migraine attacks in patients with chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: The score relating to headache impact was significantly lower in the EPA vs placebo group at weeks 4 (P = .017) and 8 (P = .042). At 8 weeks, EPA treatment led to a greater reduction in mean MHD (−9.76 vs −4.60; P < .001) and mean number of attacks per month (3 vs 4; P = .012) than placebo. In the EPA group, only three patients experienced nausea and gastrointestinal upset.

Study details: This randomized controlled trial included 60 adult patients with CM who received 1000 mg EPA or placebo twice daily for 8 weeks and continued their first-line preventive pharmacotherapy throughout the trial.

Disclosure: The study was supported by the research committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mohammadnezhad G, Assarzadegan F, Koosha M, Esmaily H. Eicosapentaenoic acid versus placebo as adjunctive therapy in chronic migraine: A randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2024 (Sept 2). doi: 10.1111/head.14808 Source

Long-term Safety of Intranasal Zavegepant for Acute Treatment of Migraine

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray, administered as needed for up to eight doses per month, demonstrated long-term safety in the acute treatment of migraine over 1 year.

Major finding: The most common adverse events (AE), reported in ≥5% patients receiving zavegepant, were dysgeusia, nasal discomfort, COVID-19, nausea, nasal congestion, throat irritation, and back pain. In the 1-year period, only 6.8% patients discontinued treatment due to AE; dysgeusia was the most common cause, accounting for 1.5% of discontinuations. No deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2/3, open-label safety study included 603 adults with moderate to severe migraine who had a history of 2 to 8 moderate to severe attacks per month and were treated with intranasal 10 mg zavegepant daily for 1 year.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of or holding stocks of or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared having ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Mullin K, Croop R, Mosher L, et al. Long-term safety of zavegepant nasal spray for acute treatment of migraine: A phase 2/3 open-label study. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 30). doi: 10.1177/033310242412594 Source

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray, administered as needed for up to eight doses per month, demonstrated long-term safety in the acute treatment of migraine over 1 year.

Major finding: The most common adverse events (AE), reported in ≥5% patients receiving zavegepant, were dysgeusia, nasal discomfort, COVID-19, nausea, nasal congestion, throat irritation, and back pain. In the 1-year period, only 6.8% patients discontinued treatment due to AE; dysgeusia was the most common cause, accounting for 1.5% of discontinuations. No deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2/3, open-label safety study included 603 adults with moderate to severe migraine who had a history of 2 to 8 moderate to severe attacks per month and were treated with intranasal 10 mg zavegepant daily for 1 year.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of or holding stocks of or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared having ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Mullin K, Croop R, Mosher L, et al. Long-term safety of zavegepant nasal spray for acute treatment of migraine: A phase 2/3 open-label study. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 30). doi: 10.1177/033310242412594 Source

Key clinical point: Zavegepant nasal spray, administered as needed for up to eight doses per month, demonstrated long-term safety in the acute treatment of migraine over 1 year.

Major finding: The most common adverse events (AE), reported in ≥5% patients receiving zavegepant, were dysgeusia, nasal discomfort, COVID-19, nausea, nasal congestion, throat irritation, and back pain. In the 1-year period, only 6.8% patients discontinued treatment due to AE; dysgeusia was the most common cause, accounting for 1.5% of discontinuations. No deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2/3, open-label safety study included 603 adults with moderate to severe migraine who had a history of 2 to 8 moderate to severe attacks per month and were treated with intranasal 10 mg zavegepant daily for 1 year.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some authors declared being employees of or holding stocks of or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. Some others declared having ties with various sources, including Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Mullin K, Croop R, Mosher L, et al. Long-term safety of zavegepant nasal spray for acute treatment of migraine: A phase 2/3 open-label study. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 30). doi: 10.1177/033310242412594 Source

Migraine and GDM Raise Risk for Major Cerebro- and Cardiovascular Events in Women

Key clinical point: Women with either migraine or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) faced an increased long-term risk for developing major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at a premature age (≤60 years), with the risk being significantly higher among those with both conditions.

Major findings: Women with migraine or GDM had a significantly higher 20-year risk for premature MACCE than women without these conditions (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.65; 95% CI 1.49-1.82 for migraine and aHR 1.64; 95% CI 1.37-1.96 for GDM). The risk was highest among women with both migraine and GDM (aHR 2.35; 95% CI 1.03-5.36).

Study details: This population-based longitudinal cohort study included 1,390,451 women, of which 56,811 had migraine, 24,700 had GDM, 1484 had both migraine and GDM, and 1,307,456 women had neither migraine nor GDM.

Disclosure: The study was funded by Aarhus University. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, et al. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1111/head.14821 Source

Key clinical point: Women with either migraine or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) faced an increased long-term risk for developing major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at a premature age (≤60 years), with the risk being significantly higher among those with both conditions.

Major findings: Women with migraine or GDM had a significantly higher 20-year risk for premature MACCE than women without these conditions (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.65; 95% CI 1.49-1.82 for migraine and aHR 1.64; 95% CI 1.37-1.96 for GDM). The risk was highest among women with both migraine and GDM (aHR 2.35; 95% CI 1.03-5.36).

Study details: This population-based longitudinal cohort study included 1,390,451 women, of which 56,811 had migraine, 24,700 had GDM, 1484 had both migraine and GDM, and 1,307,456 women had neither migraine nor GDM.

Disclosure: The study was funded by Aarhus University. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, et al. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1111/head.14821 Source

Key clinical point: Women with either migraine or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) faced an increased long-term risk for developing major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at a premature age (≤60 years), with the risk being significantly higher among those with both conditions.

Major findings: Women with migraine or GDM had a significantly higher 20-year risk for premature MACCE than women without these conditions (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.65; 95% CI 1.49-1.82 for migraine and aHR 1.64; 95% CI 1.37-1.96 for GDM). The risk was highest among women with both migraine and GDM (aHR 2.35; 95% CI 1.03-5.36).

Study details: This population-based longitudinal cohort study included 1,390,451 women, of which 56,811 had migraine, 24,700 had GDM, 1484 had both migraine and GDM, and 1,307,456 women had neither migraine nor GDM.

Disclosure: The study was funded by Aarhus University. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, et al. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1111/head.14821 Source

Meta-Analysis Shows Increased Neck Pain and Disability in Migraine

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine experienced considerable neck pain–related disability, with the effect being more prominent among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major findings: Patients with migraine reported a mean Neck Disability Index (NDI) score of 16.2, indicative of moderate disability. The NDI scores were 12.1 points higher among patients with migraine vs control individuals without headache (P < .001) and 5.5 points higher among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 33 observational studies including patients with migraine, patients with tension-type headache, and healthy individuals without headache.

Disclosure: The study did not receive any funding. Four authors declared receiving personal fees or honoraria for consultation from or having other ties with various sources; others declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1177/033310242412742 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine experienced considerable neck pain–related disability, with the effect being more prominent among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major findings: Patients with migraine reported a mean Neck Disability Index (NDI) score of 16.2, indicative of moderate disability. The NDI scores were 12.1 points higher among patients with migraine vs control individuals without headache (P < .001) and 5.5 points higher among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 33 observational studies including patients with migraine, patients with tension-type headache, and healthy individuals without headache.

Disclosure: The study did not receive any funding. Four authors declared receiving personal fees or honoraria for consultation from or having other ties with various sources; others declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1177/033310242412742 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine experienced considerable neck pain–related disability, with the effect being more prominent among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major findings: Patients with migraine reported a mean Neck Disability Index (NDI) score of 16.2, indicative of moderate disability. The NDI scores were 12.1 points higher among patients with migraine vs control individuals without headache (P < .001) and 5.5 points higher among patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 33 observational studies including patients with migraine, patients with tension-type headache, and healthy individuals without headache.

Disclosure: The study did not receive any funding. Four authors declared receiving personal fees or honoraria for consultation from or having other ties with various sources; others declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1177/033310242412742 Source

Coffee’s ‘Sweet Spot’: Daily Consumption and Cardiometabolic Risk

Each and every day, 1 billion people on this planet ingest a particular psychoactive substance. This chemical has fairly profound physiologic effects. It increases levels of nitric oxide in the blood, leads to vasodilation, and, of course, makes you feel more awake. The substance comes in many forms but almost always in a liquid medium. Do you have it yet? That’s right. The substance is caffeine, quite possibly the healthiest recreational drug that has ever been discovered.

This might be my New England upbringing speaking, but when it comes to lifestyle and health, one of the rules I’ve internalized is that things that are pleasurable are generally bad for you. I know, I know — some of you love to exercise. Some of you love doing crosswords. But you know what I mean. I’m talking French fries, smoked meats, drugs, smoking, alcohol, binge-watching Firefly. You’d be suspicious if a study came out suggesting that eating ice cream in bed reduces your risk for heart attack, and so would I. So I’m always on the lookout for those unicorns of lifestyle factors, those rare things that you want to do and are also good for you.

So far, the data are strong for three things: sleeping, (safe) sexual activity, and coffee. You’ll have to stay tuned for articles about the first two. Today, we’re brewing up some deeper insights about the power of java.

I was inspired to write this article because of a paper, “Habitual Coffee, Tea, and Caffeine Consumption, Circulating Metabolites, and the Risk of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity,” appearing September 17 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM).

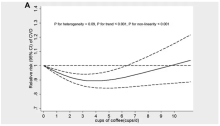

This is not the first study to suggest that coffee intake may be beneficial. A 2013 meta-analysis summarized the results of 36 studies with more than a million participants and found a U-shaped relationship between coffee intake and cardiovascular risk. The sweet spot was at three to five cups a day; people drinking that much coffee had about a 15% reduced risk for cardiovascular disease compared with nondrinkers.

But here’s the thing. Coffee contains caffeine, but it is much more than that. It is a heady brew of various chemicals and compounds, phenols, and chlorogenic acids. And, of course, you can get caffeine from stuff that isn’t coffee — natural things like tea — and decidedly unnatural things like energy drinks. How do you figure out where the benefit really lies?

The JCEM study leveraged the impressive UK Biobank dataset to figure this out. The Biobank recruited more than half a million people from the UK between 2006 and 2010 and collected a wealth of data from each of them: surveys, blood samples, biometrics, medical imaging — the works. And then they followed what would happen to those people medically over time. It’s a pretty amazing resource.

But for the purposes of this study, what you need to know is that just under 200,000 of those participants met the key criteria for this study: being free from cardiovascular disease at baseline; having completed a detailed survey about their coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverage intake; and having adequate follow-up. A subset of that number, just under 100,000, had metabolomic data — which is where this study really gets interesting.

We’ll dive into the metabolome in a moment, but first let’s just talk about the main finding, the relationship between coffee, tea, or caffeine and cardiovascular disease. But to do that, we need to acknowledge that people who drink a lot of coffee are different from people who don’t, and it might be those differences, not the coffee itself, that are beneficial.

What were those differences? People who drank more coffee tended to be a bit older, were less likely to be female, and were slightly more likely to engage in physical activity. They ate less processed meat but also fewer vegetables. Some of those factors, like being female, are generally protective against cardiovascular disease; but some, like age, are definitely not. The authors adjusted for these and multiple other factors, including alcohol intake, BMI, kidney function, and many others to try to disentangle the effect of being the type of person who drinks a lot of coffee from the drinking a lot of coffee itself.

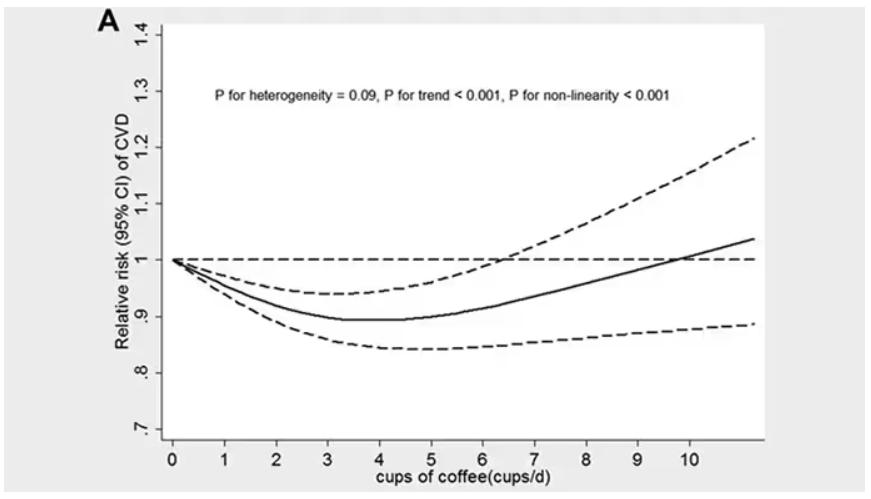

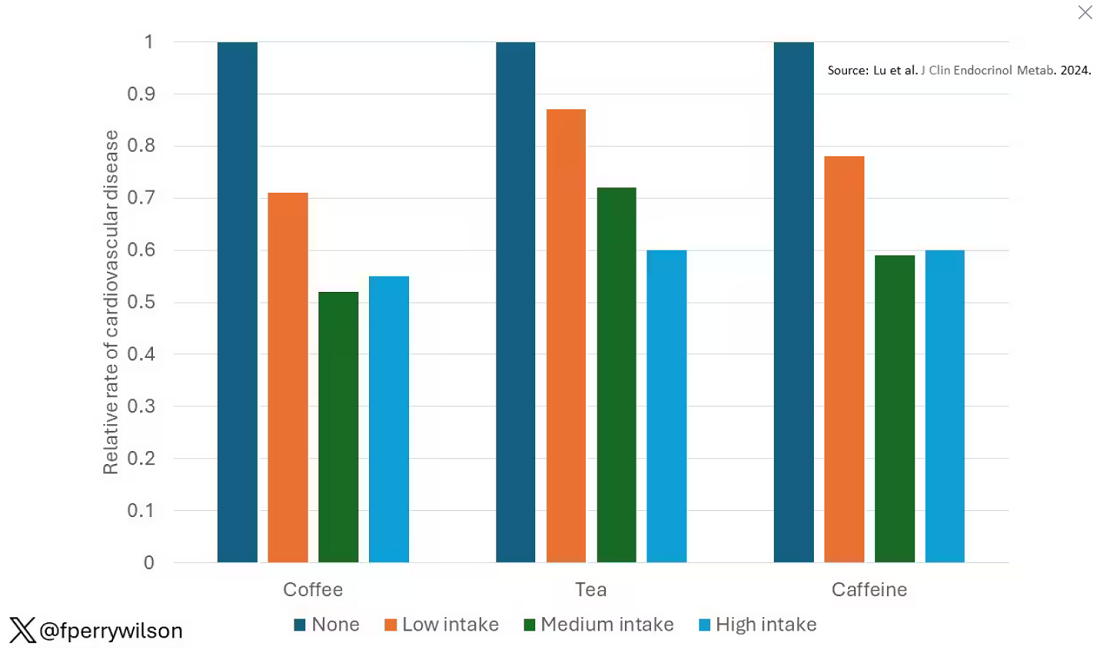

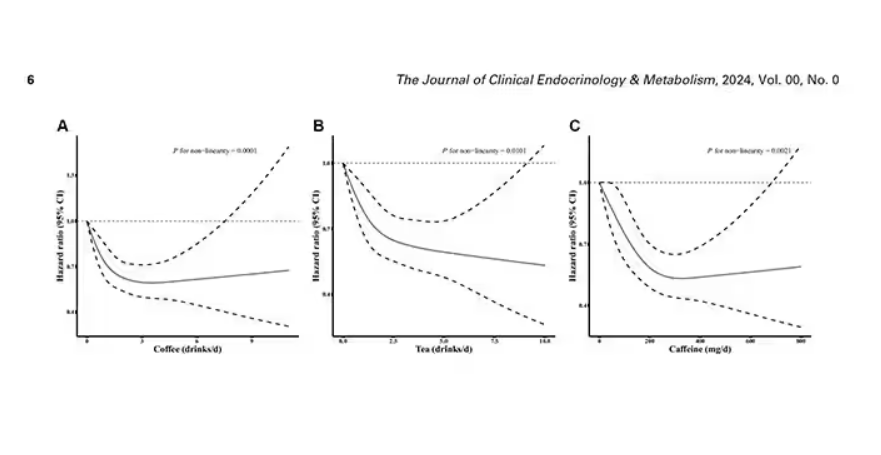

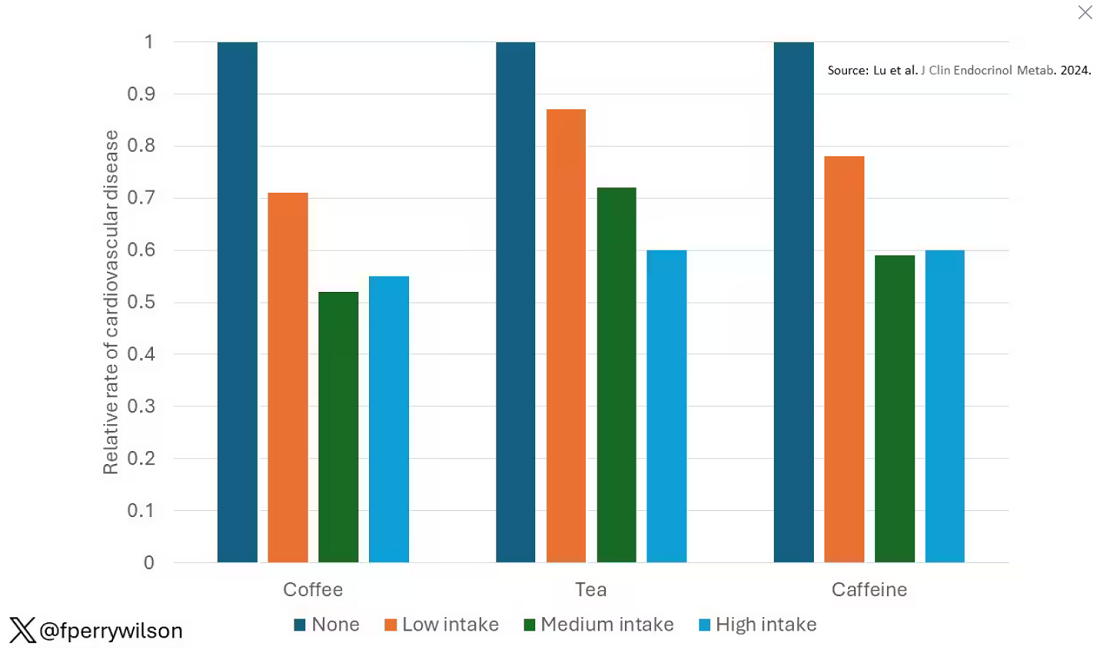

These are the results of the fully adjusted model. Compared with nonconsumers, you can see that people in the higher range of coffee, tea, or just caffeine intake have almost a 40% reduction in cardiovascular disease in follow-up.

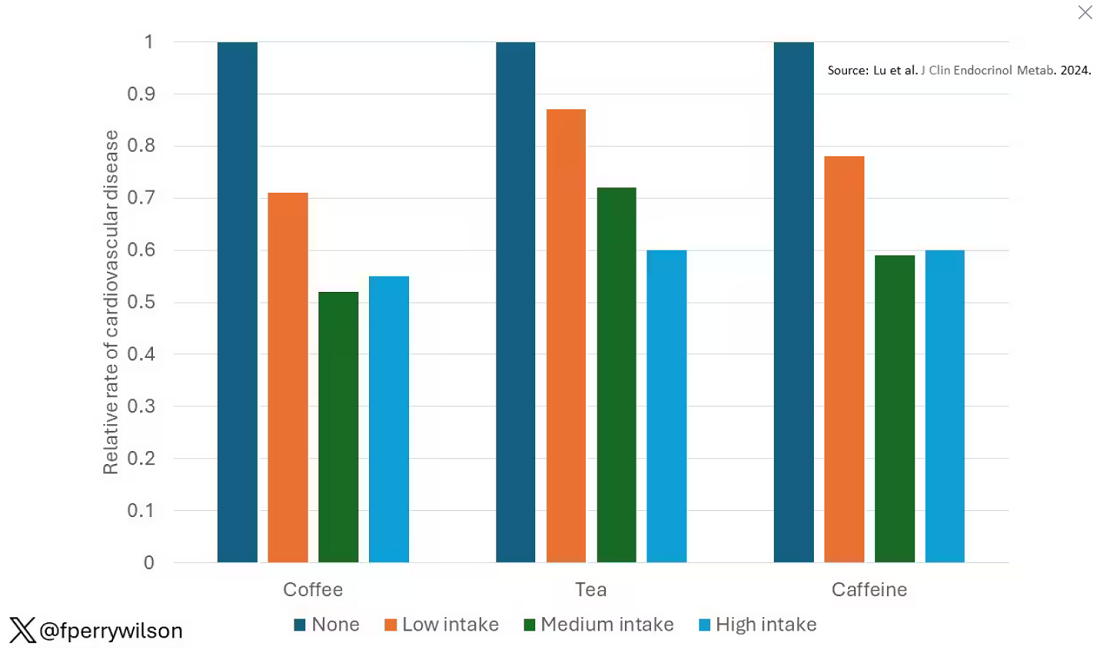

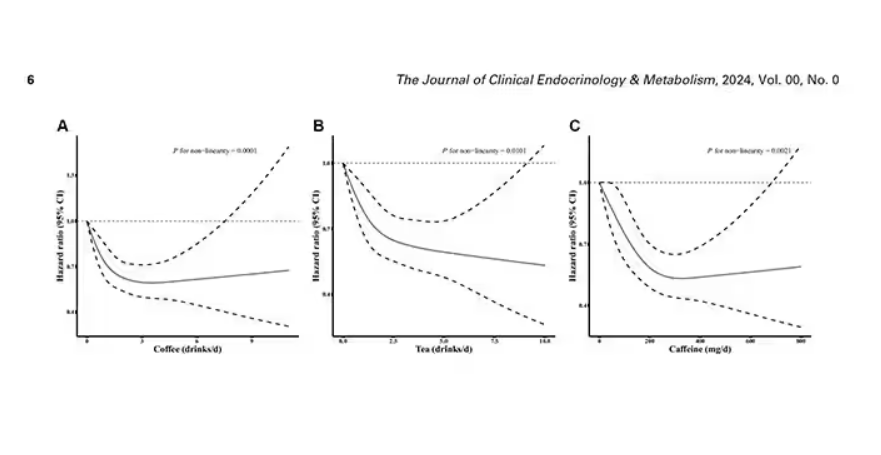

Looking at the benefit across the spectrum of intake, you again see that U-shaped curve, suggesting that a sweet spot for daily consumption can be found around 3 cups of coffee or tea (or 250 mg of caffeine). A standard energy drink contains about 120 mg of caffeine.

But if this is true, it would be good to know why. To figure that out, the authors turned to the metabolome. The idea here is that your body is constantly breaking stuff down, taking all these proteins and chemicals and compounds that we ingest and turning them into metabolites. Using advanced measurement techniques, researchers can measure hundreds or even thousands of metabolites from a single blood sample. They provide information, obviously, about the food you eat and the drinks you drink, but what is really intriguing is that some metabolites are associated with better health and some with worse

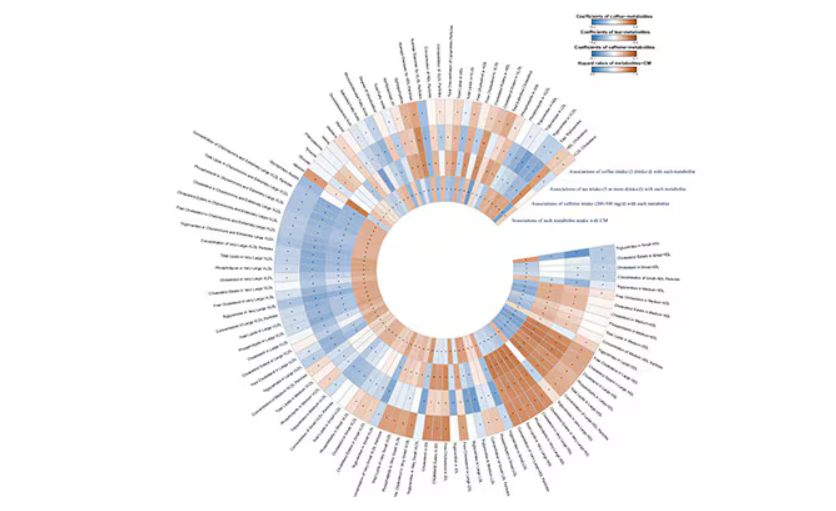

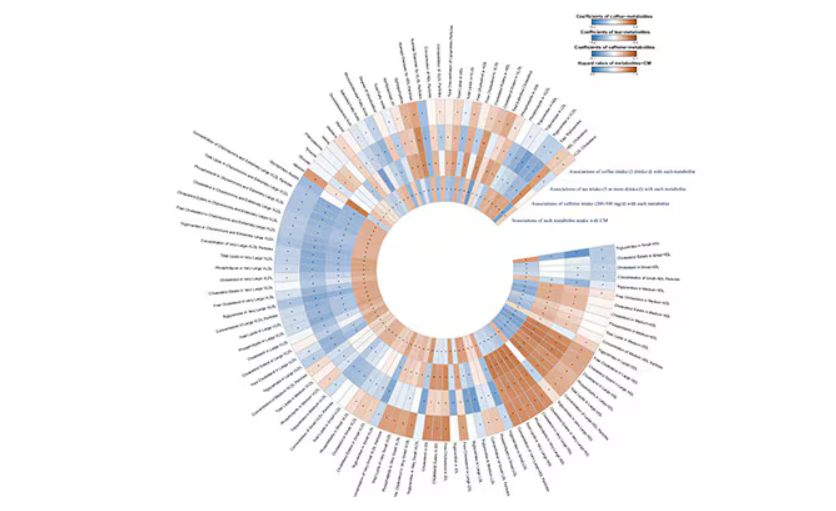

In this study, researchers measured 168 individual metabolites. Eighty of them, nearly half, were significantly altered in people who drank more coffee.

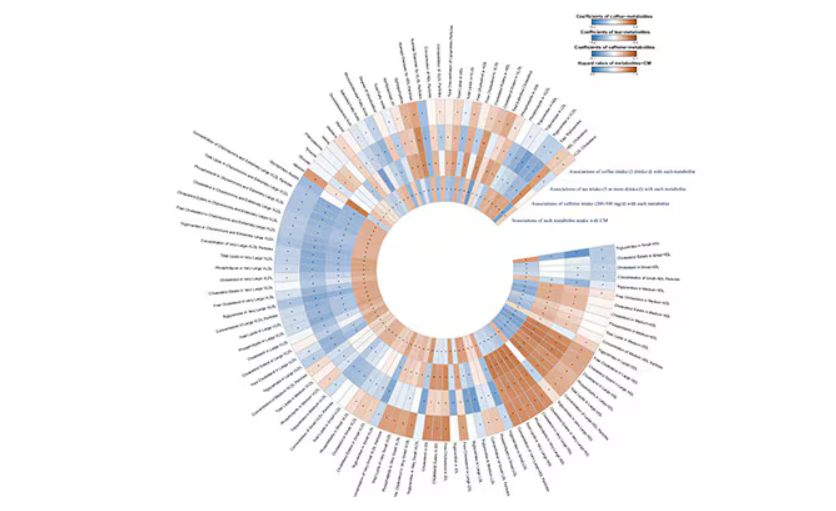

This figure summarizes the findings, and yes, this is way too complicated.

But here’s how to interpret it. The inner ring shows you how certain metabolites are associated with cardiovascular disease. The outer rings show you how those metabolites are associated with coffee, tea, or caffeine. The interesting part is that the sections of the ring (outer rings and inner rings) are very different colors.

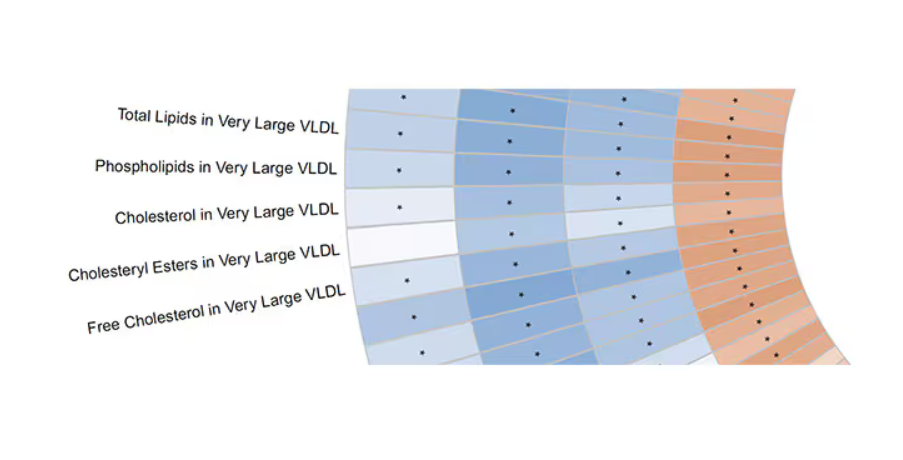

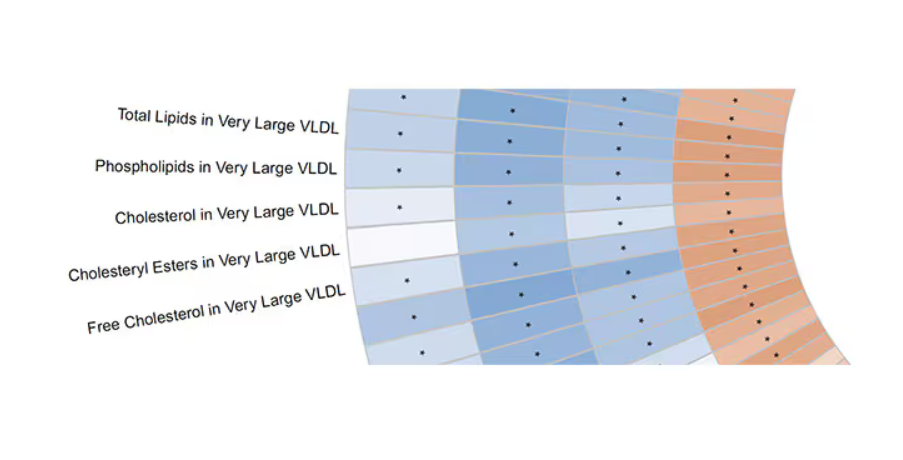

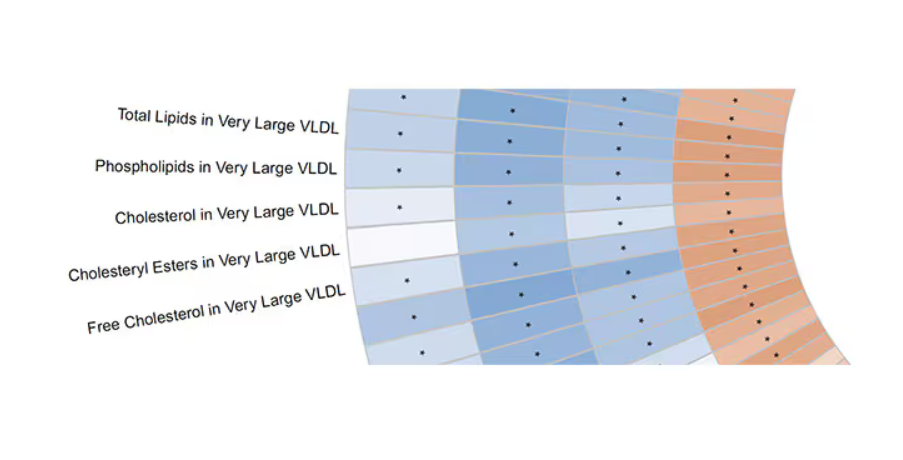

Like here.

What you see here is a fairly profound effect that coffee, tea, or caffeine intake has on metabolites of VLDL — bad cholesterol. The beverages lower it, and, of course, higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease. This means that this is a potential causal pathway from coffee intake to heart protection.

And that’s not the only one.

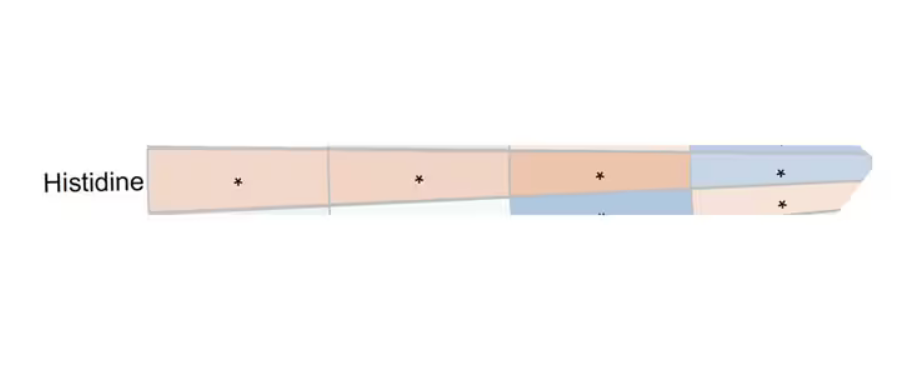

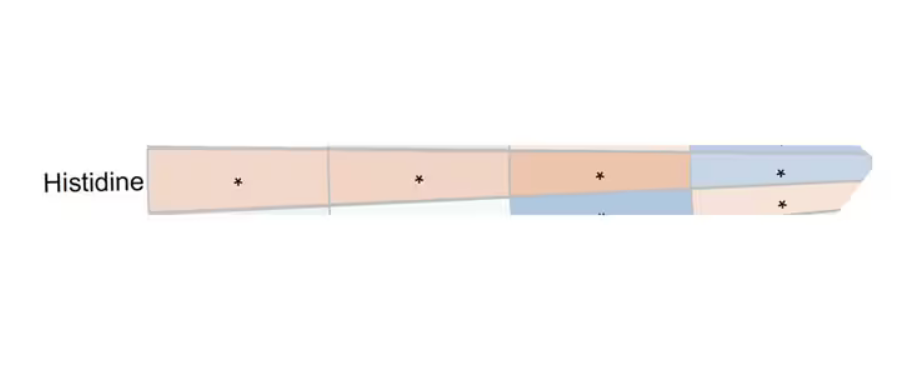

You see a similar relationship for saturated fatty acids. Higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease, and coffee intake lowers levels. The reverse works too: Lower levels of histidine (an amino acid) increase cardiovascular risk, and coffee seems to raise those levels.

Is this all too good to be true? It’s hard to say. The data on coffee’s benefits have been remarkably consistent. Still, I wouldn’t be a good doctor if I didn’t mention that clearly there is a difference between a cup of black coffee and a venti caramel Frappuccino.

Nevertheless, coffee remains firmly in my holy trinity of enjoyable things that are, for whatever reason, still good for you. So, when you’re having that second, or third, or maybe fourth cup of the day, you can take that to heart.

Dr. Wilson, associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Each and every day, 1 billion people on this planet ingest a particular psychoactive substance. This chemical has fairly profound physiologic effects. It increases levels of nitric oxide in the blood, leads to vasodilation, and, of course, makes you feel more awake. The substance comes in many forms but almost always in a liquid medium. Do you have it yet? That’s right. The substance is caffeine, quite possibly the healthiest recreational drug that has ever been discovered.

This might be my New England upbringing speaking, but when it comes to lifestyle and health, one of the rules I’ve internalized is that things that are pleasurable are generally bad for you. I know, I know — some of you love to exercise. Some of you love doing crosswords. But you know what I mean. I’m talking French fries, smoked meats, drugs, smoking, alcohol, binge-watching Firefly. You’d be suspicious if a study came out suggesting that eating ice cream in bed reduces your risk for heart attack, and so would I. So I’m always on the lookout for those unicorns of lifestyle factors, those rare things that you want to do and are also good for you.

So far, the data are strong for three things: sleeping, (safe) sexual activity, and coffee. You’ll have to stay tuned for articles about the first two. Today, we’re brewing up some deeper insights about the power of java.

I was inspired to write this article because of a paper, “Habitual Coffee, Tea, and Caffeine Consumption, Circulating Metabolites, and the Risk of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity,” appearing September 17 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM).

This is not the first study to suggest that coffee intake may be beneficial. A 2013 meta-analysis summarized the results of 36 studies with more than a million participants and found a U-shaped relationship between coffee intake and cardiovascular risk. The sweet spot was at three to five cups a day; people drinking that much coffee had about a 15% reduced risk for cardiovascular disease compared with nondrinkers.

But here’s the thing. Coffee contains caffeine, but it is much more than that. It is a heady brew of various chemicals and compounds, phenols, and chlorogenic acids. And, of course, you can get caffeine from stuff that isn’t coffee — natural things like tea — and decidedly unnatural things like energy drinks. How do you figure out where the benefit really lies?

The JCEM study leveraged the impressive UK Biobank dataset to figure this out. The Biobank recruited more than half a million people from the UK between 2006 and 2010 and collected a wealth of data from each of them: surveys, blood samples, biometrics, medical imaging — the works. And then they followed what would happen to those people medically over time. It’s a pretty amazing resource.

But for the purposes of this study, what you need to know is that just under 200,000 of those participants met the key criteria for this study: being free from cardiovascular disease at baseline; having completed a detailed survey about their coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverage intake; and having adequate follow-up. A subset of that number, just under 100,000, had metabolomic data — which is where this study really gets interesting.

We’ll dive into the metabolome in a moment, but first let’s just talk about the main finding, the relationship between coffee, tea, or caffeine and cardiovascular disease. But to do that, we need to acknowledge that people who drink a lot of coffee are different from people who don’t, and it might be those differences, not the coffee itself, that are beneficial.

What were those differences? People who drank more coffee tended to be a bit older, were less likely to be female, and were slightly more likely to engage in physical activity. They ate less processed meat but also fewer vegetables. Some of those factors, like being female, are generally protective against cardiovascular disease; but some, like age, are definitely not. The authors adjusted for these and multiple other factors, including alcohol intake, BMI, kidney function, and many others to try to disentangle the effect of being the type of person who drinks a lot of coffee from the drinking a lot of coffee itself.

These are the results of the fully adjusted model. Compared with nonconsumers, you can see that people in the higher range of coffee, tea, or just caffeine intake have almost a 40% reduction in cardiovascular disease in follow-up.

Looking at the benefit across the spectrum of intake, you again see that U-shaped curve, suggesting that a sweet spot for daily consumption can be found around 3 cups of coffee or tea (or 250 mg of caffeine). A standard energy drink contains about 120 mg of caffeine.

But if this is true, it would be good to know why. To figure that out, the authors turned to the metabolome. The idea here is that your body is constantly breaking stuff down, taking all these proteins and chemicals and compounds that we ingest and turning them into metabolites. Using advanced measurement techniques, researchers can measure hundreds or even thousands of metabolites from a single blood sample. They provide information, obviously, about the food you eat and the drinks you drink, but what is really intriguing is that some metabolites are associated with better health and some with worse

In this study, researchers measured 168 individual metabolites. Eighty of them, nearly half, were significantly altered in people who drank more coffee.

This figure summarizes the findings, and yes, this is way too complicated.

But here’s how to interpret it. The inner ring shows you how certain metabolites are associated with cardiovascular disease. The outer rings show you how those metabolites are associated with coffee, tea, or caffeine. The interesting part is that the sections of the ring (outer rings and inner rings) are very different colors.

Like here.

What you see here is a fairly profound effect that coffee, tea, or caffeine intake has on metabolites of VLDL — bad cholesterol. The beverages lower it, and, of course, higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease. This means that this is a potential causal pathway from coffee intake to heart protection.

And that’s not the only one.

You see a similar relationship for saturated fatty acids. Higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease, and coffee intake lowers levels. The reverse works too: Lower levels of histidine (an amino acid) increase cardiovascular risk, and coffee seems to raise those levels.

Is this all too good to be true? It’s hard to say. The data on coffee’s benefits have been remarkably consistent. Still, I wouldn’t be a good doctor if I didn’t mention that clearly there is a difference between a cup of black coffee and a venti caramel Frappuccino.

Nevertheless, coffee remains firmly in my holy trinity of enjoyable things that are, for whatever reason, still good for you. So, when you’re having that second, or third, or maybe fourth cup of the day, you can take that to heart.

Dr. Wilson, associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Each and every day, 1 billion people on this planet ingest a particular psychoactive substance. This chemical has fairly profound physiologic effects. It increases levels of nitric oxide in the blood, leads to vasodilation, and, of course, makes you feel more awake. The substance comes in many forms but almost always in a liquid medium. Do you have it yet? That’s right. The substance is caffeine, quite possibly the healthiest recreational drug that has ever been discovered.

This might be my New England upbringing speaking, but when it comes to lifestyle and health, one of the rules I’ve internalized is that things that are pleasurable are generally bad for you. I know, I know — some of you love to exercise. Some of you love doing crosswords. But you know what I mean. I’m talking French fries, smoked meats, drugs, smoking, alcohol, binge-watching Firefly. You’d be suspicious if a study came out suggesting that eating ice cream in bed reduces your risk for heart attack, and so would I. So I’m always on the lookout for those unicorns of lifestyle factors, those rare things that you want to do and are also good for you.

So far, the data are strong for three things: sleeping, (safe) sexual activity, and coffee. You’ll have to stay tuned for articles about the first two. Today, we’re brewing up some deeper insights about the power of java.

I was inspired to write this article because of a paper, “Habitual Coffee, Tea, and Caffeine Consumption, Circulating Metabolites, and the Risk of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity,” appearing September 17 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM).

This is not the first study to suggest that coffee intake may be beneficial. A 2013 meta-analysis summarized the results of 36 studies with more than a million participants and found a U-shaped relationship between coffee intake and cardiovascular risk. The sweet spot was at three to five cups a day; people drinking that much coffee had about a 15% reduced risk for cardiovascular disease compared with nondrinkers.

But here’s the thing. Coffee contains caffeine, but it is much more than that. It is a heady brew of various chemicals and compounds, phenols, and chlorogenic acids. And, of course, you can get caffeine from stuff that isn’t coffee — natural things like tea — and decidedly unnatural things like energy drinks. How do you figure out where the benefit really lies?

The JCEM study leveraged the impressive UK Biobank dataset to figure this out. The Biobank recruited more than half a million people from the UK between 2006 and 2010 and collected a wealth of data from each of them: surveys, blood samples, biometrics, medical imaging — the works. And then they followed what would happen to those people medically over time. It’s a pretty amazing resource.

But for the purposes of this study, what you need to know is that just under 200,000 of those participants met the key criteria for this study: being free from cardiovascular disease at baseline; having completed a detailed survey about their coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverage intake; and having adequate follow-up. A subset of that number, just under 100,000, had metabolomic data — which is where this study really gets interesting.

We’ll dive into the metabolome in a moment, but first let’s just talk about the main finding, the relationship between coffee, tea, or caffeine and cardiovascular disease. But to do that, we need to acknowledge that people who drink a lot of coffee are different from people who don’t, and it might be those differences, not the coffee itself, that are beneficial.

What were those differences? People who drank more coffee tended to be a bit older, were less likely to be female, and were slightly more likely to engage in physical activity. They ate less processed meat but also fewer vegetables. Some of those factors, like being female, are generally protective against cardiovascular disease; but some, like age, are definitely not. The authors adjusted for these and multiple other factors, including alcohol intake, BMI, kidney function, and many others to try to disentangle the effect of being the type of person who drinks a lot of coffee from the drinking a lot of coffee itself.

These are the results of the fully adjusted model. Compared with nonconsumers, you can see that people in the higher range of coffee, tea, or just caffeine intake have almost a 40% reduction in cardiovascular disease in follow-up.

Looking at the benefit across the spectrum of intake, you again see that U-shaped curve, suggesting that a sweet spot for daily consumption can be found around 3 cups of coffee or tea (or 250 mg of caffeine). A standard energy drink contains about 120 mg of caffeine.

But if this is true, it would be good to know why. To figure that out, the authors turned to the metabolome. The idea here is that your body is constantly breaking stuff down, taking all these proteins and chemicals and compounds that we ingest and turning them into metabolites. Using advanced measurement techniques, researchers can measure hundreds or even thousands of metabolites from a single blood sample. They provide information, obviously, about the food you eat and the drinks you drink, but what is really intriguing is that some metabolites are associated with better health and some with worse

In this study, researchers measured 168 individual metabolites. Eighty of them, nearly half, were significantly altered in people who drank more coffee.

This figure summarizes the findings, and yes, this is way too complicated.

But here’s how to interpret it. The inner ring shows you how certain metabolites are associated with cardiovascular disease. The outer rings show you how those metabolites are associated with coffee, tea, or caffeine. The interesting part is that the sections of the ring (outer rings and inner rings) are very different colors.

Like here.

What you see here is a fairly profound effect that coffee, tea, or caffeine intake has on metabolites of VLDL — bad cholesterol. The beverages lower it, and, of course, higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease. This means that this is a potential causal pathway from coffee intake to heart protection.

And that’s not the only one.

You see a similar relationship for saturated fatty acids. Higher levels lead to cardiovascular disease, and coffee intake lowers levels. The reverse works too: Lower levels of histidine (an amino acid) increase cardiovascular risk, and coffee seems to raise those levels.

Is this all too good to be true? It’s hard to say. The data on coffee’s benefits have been remarkably consistent. Still, I wouldn’t be a good doctor if I didn’t mention that clearly there is a difference between a cup of black coffee and a venti caramel Frappuccino.

Nevertheless, coffee remains firmly in my holy trinity of enjoyable things that are, for whatever reason, still good for you. So, when you’re having that second, or third, or maybe fourth cup of the day, you can take that to heart.

Dr. Wilson, associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ubrogepant Effectively Treats Migraine When Administered During Prodrome

Key clinical point: When administered during the prodrome, ubrogepant was more effective than placebo in improving normal functioning, reducing activity limitations, and increasing treatment satisfaction in patients with acute migraine.

Major findings: A significantly higher proportion of patients were able to function normally as early as 2 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo (odds ratio [OR] 1.76; P = .0001), with the effects being sustained through 24 hours. The patients also experienced reduced activity limitations (OR 2.07; P < .0001) and greater treatment satisfaction (OR 2.32; P < .0001) at 24 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo.

Study details: This PRODROME trial included 477 adult patients with acute migraine who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo followed by 100 mg ubrogepant for the first and second prodrome events, respectively, or vice versa.

Disclosure: The study was funded by AbbVie. Seven authors reported being employees of AbbVie and may hold stock in the company. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Lipton RB, Harriott AM, Ma JY, et al. Effect of ubrogepant on patient-reported outcomes when administered during the migraine prodrome: Results from the randomized PRODROME trial. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209745 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1212/WNL.00000000002097 Source

Key clinical point: When administered during the prodrome, ubrogepant was more effective than placebo in improving normal functioning, reducing activity limitations, and increasing treatment satisfaction in patients with acute migraine.

Major findings: A significantly higher proportion of patients were able to function normally as early as 2 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo (odds ratio [OR] 1.76; P = .0001), with the effects being sustained through 24 hours. The patients also experienced reduced activity limitations (OR 2.07; P < .0001) and greater treatment satisfaction (OR 2.32; P < .0001) at 24 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo.

Study details: This PRODROME trial included 477 adult patients with acute migraine who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo followed by 100 mg ubrogepant for the first and second prodrome events, respectively, or vice versa.

Disclosure: The study was funded by AbbVie. Seven authors reported being employees of AbbVie and may hold stock in the company. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Lipton RB, Harriott AM, Ma JY, et al. Effect of ubrogepant on patient-reported outcomes when administered during the migraine prodrome: Results from the randomized PRODROME trial. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209745 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1212/WNL.00000000002097 Source

Key clinical point: When administered during the prodrome, ubrogepant was more effective than placebo in improving normal functioning, reducing activity limitations, and increasing treatment satisfaction in patients with acute migraine.

Major findings: A significantly higher proportion of patients were able to function normally as early as 2 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo (odds ratio [OR] 1.76; P = .0001), with the effects being sustained through 24 hours. The patients also experienced reduced activity limitations (OR 2.07; P < .0001) and greater treatment satisfaction (OR 2.32; P < .0001) at 24 hours after receiving ubrogepant vs placebo.

Study details: This PRODROME trial included 477 adult patients with acute migraine who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo followed by 100 mg ubrogepant for the first and second prodrome events, respectively, or vice versa.

Disclosure: The study was funded by AbbVie. Seven authors reported being employees of AbbVie and may hold stock in the company. Other authors declared having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Lipton RB, Harriott AM, Ma JY, et al. Effect of ubrogepant on patient-reported outcomes when administered during the migraine prodrome: Results from the randomized PRODROME trial. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209745 (Aug 28). doi: 10.1212/WNL.00000000002097 Source

Does Migraine Increase the Risk for Parkinson Disease?

Key clinical point: Middle-aged and older women showed no significant association between migraine, and the risk for Parkinson disease (PD), irrespective of migraine subtypes and frequency.

Major findings: Compared to women with without migraine, those with migraine did not show a risk of PD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.07; 95% CI 0.88-1.29) irrespective of the presence of aura. No risk was seen even if patients had monthly migraine frequency (aHR 1.09; 95% CI 0.64-1.87), or a weekly or greater migraine frequency (aHR 1.10; 95% CI 0.44-2.75).

Study details: This study involved 39,312 women (age > 45 years) of whom 7321 had migraines, including 2153 with a history of migraine and 5168 with migraine with or without aura. None had a history of PD.

Disclosure: This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Two authors declared receiving research grants or personal compensation from various sources.

Source: Schulz RS, Glatz T, Buring Jeet al. Migraine and risk of Parkinson disease in women: A cohort study. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209747 (Aug 21). doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209747 Source

Key clinical point: Middle-aged and older women showed no significant association between migraine, and the risk for Parkinson disease (PD), irrespective of migraine subtypes and frequency.

Major findings: Compared to women with without migraine, those with migraine did not show a risk of PD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.07; 95% CI 0.88-1.29) irrespective of the presence of aura. No risk was seen even if patients had monthly migraine frequency (aHR 1.09; 95% CI 0.64-1.87), or a weekly or greater migraine frequency (aHR 1.10; 95% CI 0.44-2.75).

Study details: This study involved 39,312 women (age > 45 years) of whom 7321 had migraines, including 2153 with a history of migraine and 5168 with migraine with or without aura. None had a history of PD.

Disclosure: This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Two authors declared receiving research grants or personal compensation from various sources.

Source: Schulz RS, Glatz T, Buring Jeet al. Migraine and risk of Parkinson disease in women: A cohort study. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209747 (Aug 21). doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209747 Source

Key clinical point: Middle-aged and older women showed no significant association between migraine, and the risk for Parkinson disease (PD), irrespective of migraine subtypes and frequency.

Major findings: Compared to women with without migraine, those with migraine did not show a risk of PD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.07; 95% CI 0.88-1.29) irrespective of the presence of aura. No risk was seen even if patients had monthly migraine frequency (aHR 1.09; 95% CI 0.64-1.87), or a weekly or greater migraine frequency (aHR 1.10; 95% CI 0.44-2.75).

Study details: This study involved 39,312 women (age > 45 years) of whom 7321 had migraines, including 2153 with a history of migraine and 5168 with migraine with or without aura. None had a history of PD.

Disclosure: This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Two authors declared receiving research grants or personal compensation from various sources.

Source: Schulz RS, Glatz T, Buring Jeet al. Migraine and risk of Parkinson disease in women: A cohort study. Neurology. 2024;103(6):e209747 (Aug 21). doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209747 Source

Humanized Monoclonal Antibody Reduces Migraine Frequency in Phase 2 Study

Key clinical point: A single infusion of Lu AG09222, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, was more effective than placebo in reducing migraine frequency over 4 weeks in adults with episodic or chronic migraine.

Major findings: Through week 4, a single infusion of 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo led to a significantly greater reduction in monthly migraine days (−6.2 vs −4.2 days; difference −2 days; P = .02). Most adverse events were mild, with COVID-19, nasopharyngitis, and fatigue being more prevalent in those receiving 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo.

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 237 adults with migraine who did not respond to two to four previous treatments and were assigned to receive either Lu AG09222 (750 mg or 100 mg) or placebo for 4 weeks.

Disclosure: The study was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S. Three authors declared being employees of H. Lundbeck A/S, of whom one held stock options. One author reported receiving consulting, speaker, and advisory board fees from various sources, including H. Lundbeck A/S.

Source: Ashina M, Phul R, Khodaie M, et al. A monoclonal antibody to PACAP for migraine prevention. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(9):800-809 (Sept 4). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2314577 Source

Key clinical point: A single infusion of Lu AG09222, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, was more effective than placebo in reducing migraine frequency over 4 weeks in adults with episodic or chronic migraine.

Major findings: Through week 4, a single infusion of 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo led to a significantly greater reduction in monthly migraine days (−6.2 vs −4.2 days; difference −2 days; P = .02). Most adverse events were mild, with COVID-19, nasopharyngitis, and fatigue being more prevalent in those receiving 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo.

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 237 adults with migraine who did not respond to two to four previous treatments and were assigned to receive either Lu AG09222 (750 mg or 100 mg) or placebo for 4 weeks.

Disclosure: The study was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S. Three authors declared being employees of H. Lundbeck A/S, of whom one held stock options. One author reported receiving consulting, speaker, and advisory board fees from various sources, including H. Lundbeck A/S.

Source: Ashina M, Phul R, Khodaie M, et al. A monoclonal antibody to PACAP for migraine prevention. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(9):800-809 (Sept 4). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2314577 Source

Key clinical point: A single infusion of Lu AG09222, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, was more effective than placebo in reducing migraine frequency over 4 weeks in adults with episodic or chronic migraine.

Major findings: Through week 4, a single infusion of 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo led to a significantly greater reduction in monthly migraine days (−6.2 vs −4.2 days; difference −2 days; P = .02). Most adverse events were mild, with COVID-19, nasopharyngitis, and fatigue being more prevalent in those receiving 750 mg Lu AG09222 vs placebo.

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 237 adults with migraine who did not respond to two to four previous treatments and were assigned to receive either Lu AG09222 (750 mg or 100 mg) or placebo for 4 weeks.

Disclosure: The study was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S. Three authors declared being employees of H. Lundbeck A/S, of whom one held stock options. One author reported receiving consulting, speaker, and advisory board fees from various sources, including H. Lundbeck A/S.

Source: Ashina M, Phul R, Khodaie M, et al. A monoclonal antibody to PACAP for migraine prevention. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(9):800-809 (Sept 4). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2314577 Source

Establishing a Just Culture: Implications for the Veterans Health Administration Journey to High Reliability

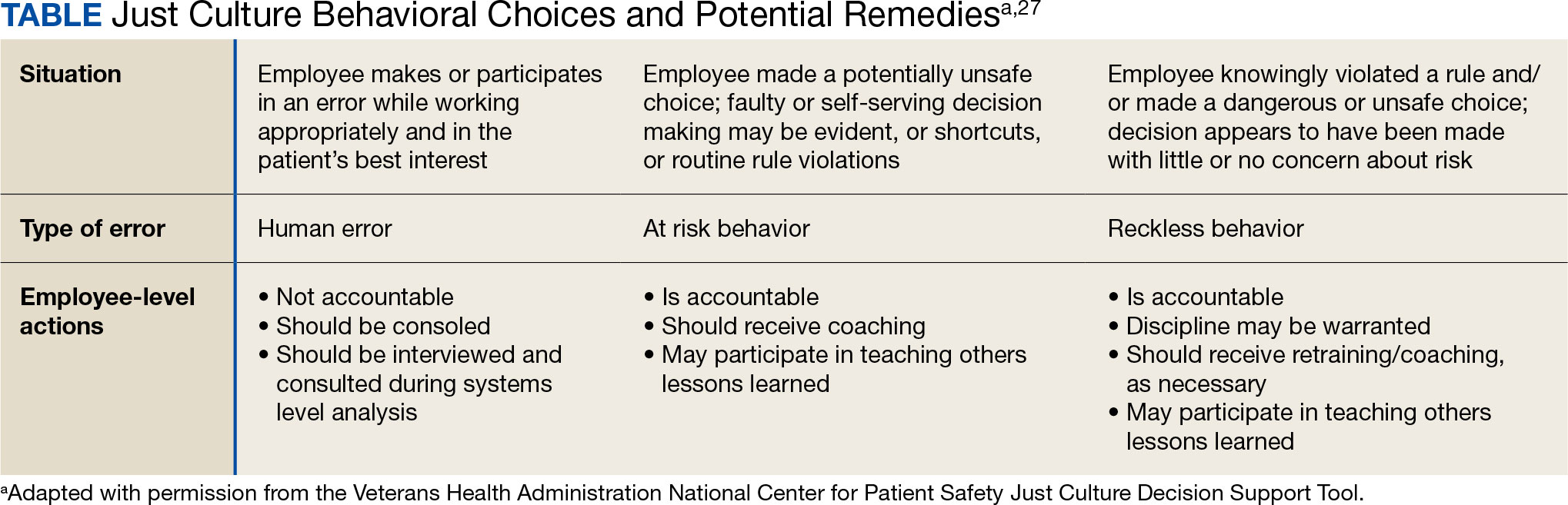

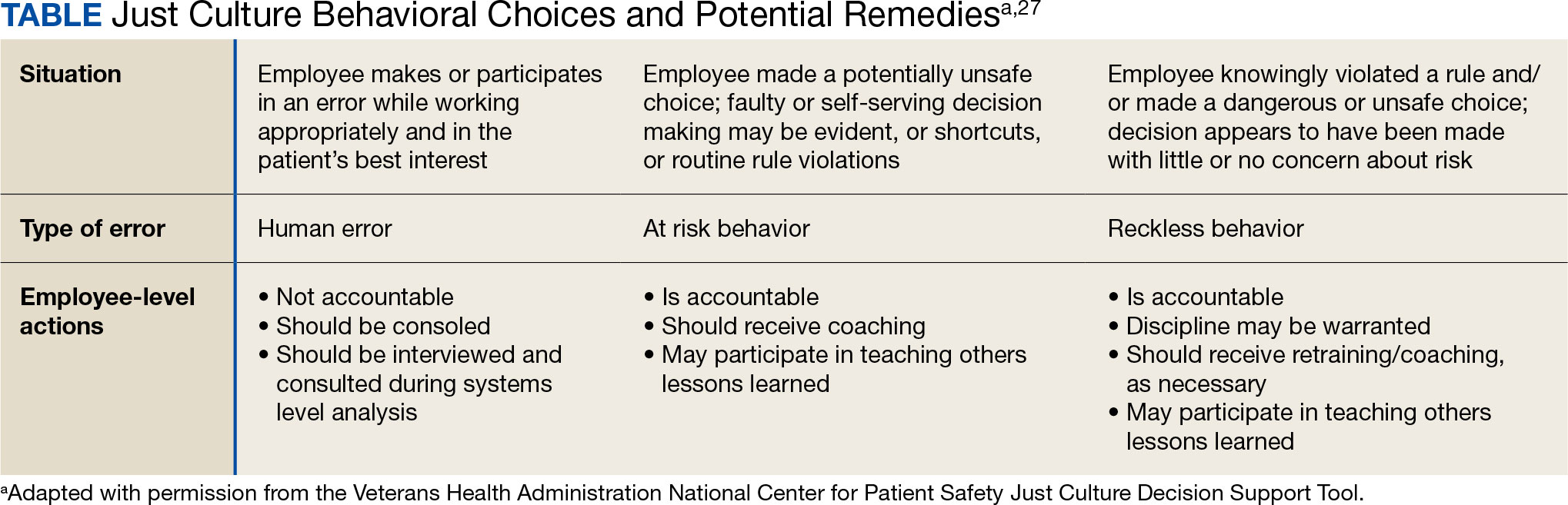

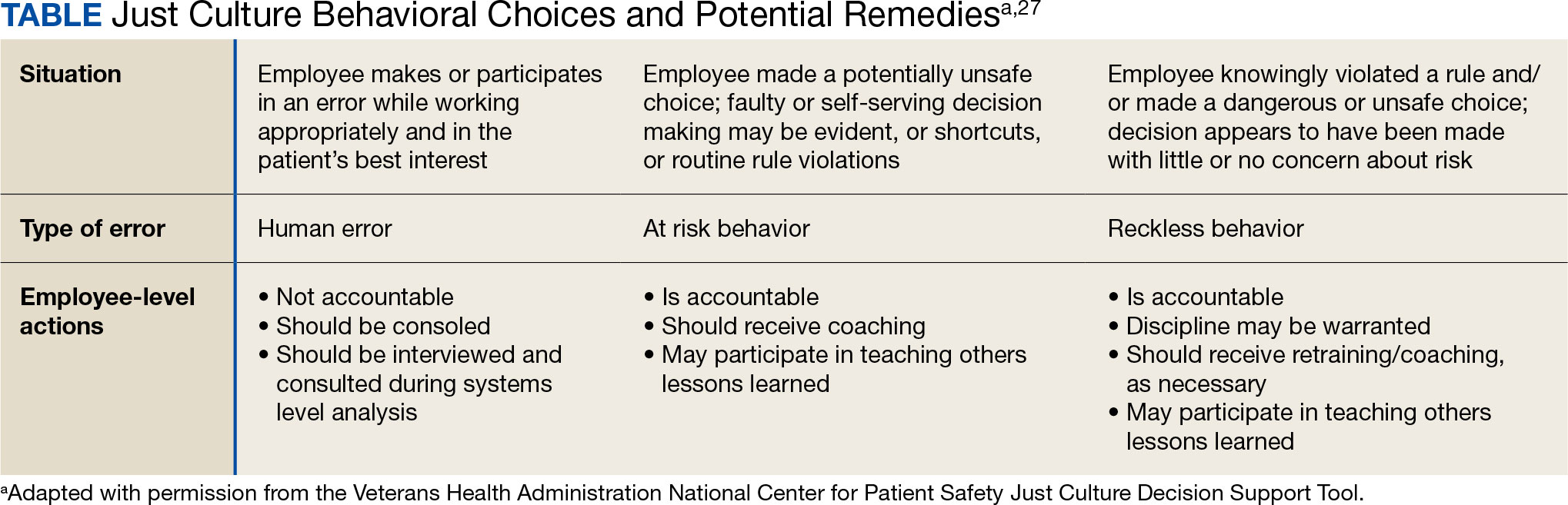

Medical errors are a persistent problem and leading cause of preventable death in the United States. There is considerable momentum behind the idea that implementation of a just culture is foundational to detecting and learning from errors in pursuit of zero patient harm.1-6 Just culture is a framework that fosters an environment of trust within health care organizations, aiming to achieve fair outcomes for those involved in incidents or near misses. It emphasizes openness, accountability, and learning, prioritizing the repair of harm and systemic improvement over assigning blame.7

A just culture mindset reflects a significant shift in thinking that moves from the tendency to blame and punish others toward a focus on organizational learning and continued process improvement.8,9 This systemic shift in fundamental thinking transforms how leaders approach staff errors and how they are addressed.10 In essence, just culture reflects an ethos centered on openness, a deep appreciation of human fallibility, and shared accountability at both the individual and organizational levels.

Organizational learning and innovation are stifled in the absence of a just culture, and there is a tendency for employees to avoid disclosing their own errors as well as those of their colleagues.11 The transformation to a just culture is often slowed or disrupted by personal, systemic, and cultural barriers.12 It is imperative that all executive, service line, and frontline managers recognize and execute their distinct responsibilities while adjudicating the appropriate course of action in the aftermath of adverse events or near misses. This requires a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to errors at the individual and organizational levels to ensure an appropriate response.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is orchestrating an enterprise transformation to develop into a high reliability organization (HRO). This began with a single-site test in 2016, which demonstrated successful results in patient safety culture, patient safety event reporting, and patient safety outcomes.13 In 2019, the VHA formally launched its enterprise-wide HRO journey in 18 hospital facilities, followed by successive waves of 67 and 54 facilities in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The VHA journey to transform into an HRO aligns with 3 pillars, 5 principles, and 7 values. The VHA has emphasized the importance of just culture as a foundational element of the HRO framework, specifically under the pillar of leadership. To promote leadership engagement, the VHA has employed an array of approaches that include education, leader coaching, and change management strategies. Given the diversity among VHA facilities, each with local cultures and histories, some sites have more readily implemented a just culture than others.14 A deeper exploration into potential obstacles, particularly concerning leadership engagement, could be instrumental for formulating strategies that further establish a just culture across the VHA.15

There is a paucity of empirical research regarding factors that facilitate and/or impede the implementation of a just culture in health care settings.16,17 Likert scale surveys, such as the Patient Safety Culture Module for the VHA All Employee Survey and its predecessor, the Patient Safety Culture Survey, have been used to assess culture and climate.18 However, qualitative evaluations directly assessing the lived experiences of those trying to implement a just culture provide additional depth and context that can help identify specific factors that support or impede becoming an HRO. The purpose of this study was to increase understanding of factors that influence the establishment and sustainment of a just culture and to identify specific methods for improving the implementation of just culture principles and practices aligned with HRO.

METHODS

This qualitative study explored facilitators and barriers to establishing and sustaining a just culture as experienced across a subset of VHA facilities by HRO leads or staff assigned with the primary responsibilities of supporting facility-level HRO transformation. HRO leads are assigned responsibility for supporting executive leadership in planning, coordinating, implementing, and monitoring activities to ensure effective high reliability efforts, including focused efforts to establish a robust patient safety program, a culture of safety, and a culture of continuous process improvement.

Virtual focus group discussions held via Microsoft Teams generated in-depth, diverse perspectives from participants across 16 VHA facilities. Qualitative research and evaluation methods provide an enhanced depth of understanding and allow the emergence of detailed data.19 A qualitative grounded theory approach elicits complex, multifaceted phenomena that cannot be appreciated solely by numeric data.20 Grounded theory was selected to limit preconceived notions and provide a more systematic analysis, including open, axial, and thematic coding. Such methods afford opportunities to adapt to unplanned follow-up questions and thus provide a flexible approach to generate new ideas and concepts.21 Additionally, qualitative methods help overcome the tendencies of respondents to agree rather than disagree when presented with Likert-style scales, which tend to skew responses toward the positive.22

Participants must have been assigned as an HRO lead for ≥ 6 months at the same facility. Potential participants were identified through purposive sampling, considering their leadership roles in HRO and experience with just culture implementation, the size and complexity of their facility, and geographic distribution. Invitations explaining the study and encouraging voluntary participation to participate were emailed. Of 37 HRO leads invited to participate in the study, 16 agreed to participate and attended 1 of 3 hour-long focus group sessions. One session was rescheduled due to limited attendance. Participants represented a mix of VHA sites in terms of geography, facility size, and complexity.

Focus Group Procedures

Demographic data were collected prior to sessions via an online form to better understand the participant population, including facility complexity level, length of time in HRO lead role, clinical background, and facility level just culture training. Each session was led by an experienced focus group facilitator (CV) who was not directly involved with the overall HRO implementation to establish a neutral perspective. Each session was attended by 4 to 7 participants and 2 observers who took notes. The sessions were recorded and included automated transcriptions, which were edited for accuracy.

Focus group sessions began with a brief introduction and an opportunity for participants to ask questions. Participants were then asked a series of open-ended questions to elicit responses regardingfacilitators, barriers, and leadership support needed for implementing just culture. The questions were part of a facilitator guide that included an introductory script and discussion prompts to ensure consistency across focus groups.

Facilitators were defined as factors that increase the likelihood of establishing or sustaining a just culture. Barriers were defined as factors that decrease or inhibit the likelihood of establishing or sustaining just culture. The focus group facilitator encouraged all participants to share their views and provided clarification if needed, as well as prompts and examples where appropriate, but primarily sought to elicit responses to the questions.

Institutional review board review and approval were not required for this quality improvement initiative. The project adhered to ethical standards of research, including asking participants for verbal consent and preserving their confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, and prior to the focus group sessions, participants were provided information explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participant identities were kept confidential, and all data were anonymized during the analysis phase. Pseudonyms or identifiers were used during data transcription to protect participant identity. All data, including recordings and transcriptions, were stored on password-protected devices accessible only to the research team. Any identifiable information was removed during data analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim, capturing all verbal interactions and nonverbal cues that may contribute to understanding the participants' perspectives. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the focus group discussions.23 The transcribed data were organized, coded, and analyzed using ATLAS.ti 23 qualitative data software to identify key themes and patterns.

Results

The themes identified include the 5 facilitators, barriers, and recommendations most frequently mentioned by HRO leads across focus group sessions. The nature of each theme is described, along with commonly mentioned examples and direct quotes from participants that illustrate our understanding of their perspectives.

Facilitators

Training and coaching (26 responses). The availability of training around the Just Culture Decision Support Tool (DST) was cited as a practical aid in guiding leaders through complex just culture decisions to ensure consistency and fairness. Additionally, an executive leadership team that served as champions for just culture principles played a vital role in promoting and sustaining the approach: “Training them on the roll-out of the decision support tool with supervisors at all levels, and education for just culture and making it part of our safety forum has helped for the last 4 months.” “Having some regular training and share-out cadences embedded within the schedule as well as dynamic directors and well-trained executive leadership team (ELT) for support has been a facilitator.”

Increased transparency (16 responses). Participants consistently highlighted the importance of leadership transparency as a key facilitator for implementing just culture. Open and honest communication from top-level executives fostered an environment of trust and accountability. Approachable and physically present leadership was seen as essential for creating a culture where employees felt comfortable reporting errors and concerns without fear of retaliation: “They’re surprisingly honest with themselves about what we can do, what we cannot do, and they set the expectations exactly at that.”

Approachable leadership (15 responses). Participants frequently mentioned the importance of having dynamic leadership spearheading the implementation of just culture and leading by example. Having a leadership team that accepts accountability and reinforces consistency in the manner that near misses or mistakes are addressed is paramount to promoting the principles of just culture and increasing psychological safety: “We do have very approachable leadership, which I know is hard if you’re trying to implement that nationwide, it’s hard to implement approachability. But I do think that people raise their concerns, and they’ll stop them in the hallway and ask them questions. So, in terms of comfort level with the executive leadership, I do think that’s high, which would promote psychological safety.”

Feedback loops and follow through (13 responses). Participants emphasized the importance of taking concrete actions to address concerns and improve processes. Regular check-ins with supervisors to discuss matters related to just culture provided a structured opportunity for addressing issues and reinforcing the importance of the approach: “One thing that we’ve really focused on is not only identifying mistakes, but [taking] ownership. We continue to track it until … it’s completed and then a process of how to communicate that back and really using closed loop communication with the staff and letting them know.”

Forums and town halls (10 responses). These platforms created feedback loops that were seen as invaluable tools for sharing near misses, celebrating successes, and promoting open dialogue. Forums and town halls cultivated a culture of continuous improvement and trust: “We’ll celebrate catches, a safety story is inside that catch. So, if we celebrate the change, people feel safer to speak up.” “Truthfully, we’ve had a great relationship since establishing our safety forums and just value open lines of communication.”

Barriers

Inadequate training (30 responses). Insufficient engagement during training—limited bandwidth and availability to attend and actively participate in training—was perceived as detrimental to creating awareness and buy-in from staff, supervisors, and leadership, thereby hindering successful integration of just culture principles. Participants also identified too many conflicting priorities from VHA leadership, which contributes to training and information fatigue among staff and supervisors. “Our biggest barrier is just so many different competing priorities going on. We have so much that we’re asking people to do.” “One hundred percent training is feeling more like a ticked box than actually yielding results, I have a very hard time getting staff engaged.”

Inconsistency between executive leaders and middle managers (28 responses). A lack of consistency in the commitment to and enactment of just culture principles among leaders poses a challenge. Participants gave several examples of inconsistencies in messaging and reinforcement of just culture principles, leading to confusion among staff and hindering adoption. Likewise, the absence of standardized procedures for implementing just culture created variability: “The director coming in and trying to change things, it put a lot of resistance, we struggle with getting the other ELT members on board … some of the messages that come out at times can feel more punitive.”

Middle management resistance (22 responses). In some instances, participants reported middle managers exhibiting attitudes and behaviors that undermined the application of just culture principles and effectiveness. Such attitudes and behaviors were attributed to a lack of adequate training, coaching, and awareness. Other perceived contributions included fear of failure and a desire to distance oneself from staff who have made mistakes: “As soon as someone makes an error, they go straight to suspend them, and that’s the disconnect right there.” “There’s almost a level of working in the opposite direction in some of the mid-management.”

Cultural misalignment (18 responses). The existing culture of distancing oneself from mistakes presented a significant barrier to the adoption of just culture because it clashed with the principles of open reporting and accountability. Staff underreported errors or framed them in a way that minimized personal responsibility, thereby making it more essential to put in the necessary and difficult work to learn from mistakes: “One, you’re going to get in trouble. There’s going to be more work added to you or something of that nature."

Lack of accountability for opposition(17 responses). Participants noted a clear lack of accountability for those who opposed or showed resistance to just culture, which allowed resistance to persist without consequences. In many instances, leaders were described as having overlooked repeated instances of unjust attitudes and behaviors (eg, inappropriate blame or punishment), which allowed those practices to continue. “Executive leadership is standing on the hill and saying we’re a just culture and we do everything correctly, and staff has the expectation that they’re going to be treated with just culture and then the middle management is setting that on fire, then we show them that that’s not just culture, and they continue to have those poor behaviors, but there’s a lack of accountability.”

Limited bandwidth and lack of coordination (14 responses). HRO leads often faced role-specific constraints in having adequate time and authority to coordinate efforts to implement or sustain just culture. This includes challenges with coordination across organizational levels (eg, between the hospital and regional Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] management levels) and across departments within the hospital (eg, between human resources and service lines or units). “Our VISN human resources is completely detached. They’ll not cooperate with these efforts, which is hard.” “There’s not enough bandwidth to actually support, I’m just 1 person.” “[There’s] all these mandated trainings of 8 hours when we’re already fatigued, short-staffed, taking 3 other HRO classes.”

Recommendations

Training improvements (24 responses). HRO leads recommended that comprehensive training programs be developed and implemented for staff, supervisors, and leadership to increase awareness and understanding of just culture principles. These training initiatives should focus on fostering a shared understanding of the core tenets of just culture, the importance of error reporting, and the processes involved in fair and consistent decision making (eg, training simulations on use of the Just Culture DST). “We’ve really never had any formal training on the decision support tool. I hope that what’s coming out for next year. We’ll have some more formal training for the tool because I think it would be great to really have our leadership and our supervisors and our managers use that tool.” “We can give a more directed and intentional training to leadership on the 4 foundational practices and what it means to implement those and what it means to utilize that behavioral component of HRO.”

Clear and consistent procedures toincrease accountability (22 responses). To promote a culture of accountability and consistency in the application of just culture principles, organizations should establish clear mechanisms for reporting, investigating, and addressing incidents. Standardized procedures and DSTs can aid in ensuring that responses to errors are equitable and align with just culture principles: “I recommend accountability; if it’s clearly evidenced that you’re not toeing the just culture line, then we need to be able to do something about it and not just finger wag.” “[We need to have] a templated way to approach just culture implementation. The decision support tool is great, I absolutely love having the resources and being able to find a lot of clinical examples and discussion tools like that. But when it comes down to it, not having that kind of official thing to fall back on it can be a little bit rough.”

Additional coaching and consultationsupport (15 responses). To support supervisors in effectively implementing just culture within their teams, participants recommended that organizations provide ongoing coaching and mentorship opportunities. Additionally, third-party consultants with expertise in just culture were described as offering valuable guidance, particularly in cases where internal staff resources or HRO lead bandwidth may be limited. “There are so many consulting agencies with HRO that have been contracted to do different projects, but maybe that can help with an educational program.” “I want to see my executive leadership coach the supervisors up right and then allow them to do one-on-ones and facilitate and empower the frontline staff, and it’s just a good way of transparency and communication.”

Improved leadership sponsorship (15 responses). Participants noted that leadership buy-in is crucial for the successful implementation of just culture. Facilities should actively engage and educate leadership teams on the benefits of just culture and how it aligns with broader patient safety and organizational goals. Leaders should be visible and active champions of its principles, supporting change in their daily engagements with staff. “ELT support is absolutely necessary. Why? Because they will make it important to those in their service lines. They will make it important to those supervisors and managers. If it’s not important to that ELT member, then it’s not going to be important to that manager or that supervisor.”

Improved collaboration with patient safety and human resources (6 responses). Collaborative efforts with patient safety and human resources departments were seen as instrumental in supporting just culture, emphasizing its importance, and effectively addressing issues. Coordinating with these departments specifically contributes to consistent reinforcement and expands the bandwidth of HRO leads. These departments play integral roles in supporting just culture through effective policies, procedures, and communication. “I think it would be really helpful to have common language between what human resources teaches and what is in our decision support tool.”

DISCUSSION

This study sought to collect and synthesize the experiences of leaders across a large, integrated health care system in establishing and sustaining a just culture as part of an enterprise journey to become an HRO.24 The VHA has provided enterprise-wide support (eg, training, leader coaching, and communications) for the implementation of HRO principles and practices with the goal of creating a culture of safety, which includes just culture elements. This support includes enterprise program offices, VISNs, and hospital facilities, though notably, there is variability in how HRO is implemented at the local level. The facilitators, barriers, and recommendations presented in this article are representative of the designated HRO leads at VHA hospital facilities who have direct experience with implementing and sustaining just culture. The themes presented offer specific opportunities for intervention and actionable strategies to enhance just culture initiatives, foster psychological safety and accountability, and ultimately improve the quality of care and patient outcomes.3,25

Frequently identified facilitators such as providing training and coaching, having leaders who are available and approachable, demonstrating follow-through to address identified issues, and creating venues where errors and successes can be openly discussed.26 These facilitators are aligned with enterprise HRO support strategies orchestrated by the VHA at the enterprise VISN and facility levels to support a culture of safety, continuous process improvement, and leadership commitment.

Frequently identified barriers included inadequate training, inconsistent application of just culture by middle managers vs senior leaders, a lack of accountability or corrective action when unjust corrective actions took place, time and resource constraints, and inadequate coordination across departments (eg, operational departments and human resources) and organizational levels. These factors were identified through focus groups with a limited set of HRO leads. They may reflect challenges to changing culture that may be deeply engrained in individual histories, organizational norms, and systemic practices. Improving upon these just culture initiatives requires multifaceted approaches and working through resistance to change.

VHA HRO leads identified several actionable recommendations that may be used in pursuit of a just culture. First, improvements in training involving how to apply just culture principles and, specifically, the use of the Just Culture DST were identified as an opportunity for improvement. The VHA National Center for Patient Safety developed the DST as an aid for leaders to effectively address errors in line with just culture principles, balancing individual and system accountability.27 The DST specifically addresses human error as well as risky and reckless behavior, and it clarifies the delineation between individual and organizational accountability (Table).3

Scenario-based interactive training and simulations may prove especially useful for middle managers and frontline supervisors who are closest to errors. Clear and repeatable procedures for determining courses of action for accountability in response are needed, and support for their application must be coordinated across multiple departments (eg, patient safety and human resources) to ensure consistency and fairness. Coaching and consultation are also viewed as beneficial in supporting applications. Coaching is provided to senior leaders across most facilities, but the availability of specific, role-based coaching and training is more limited for middle managers and frontline supervisors who may benefit most from hands-on support.

Lastly, sponsorship from leaders was viewed as critical to success, but follow through to ensure support flows down from the executive suite to the frontline is variable across facilities and requires consistent effort over time. This is especially challenging given the frequent turnover in leadership roles evident in the VHA and other health care systems.

Limitations