User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

When you see something ...

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

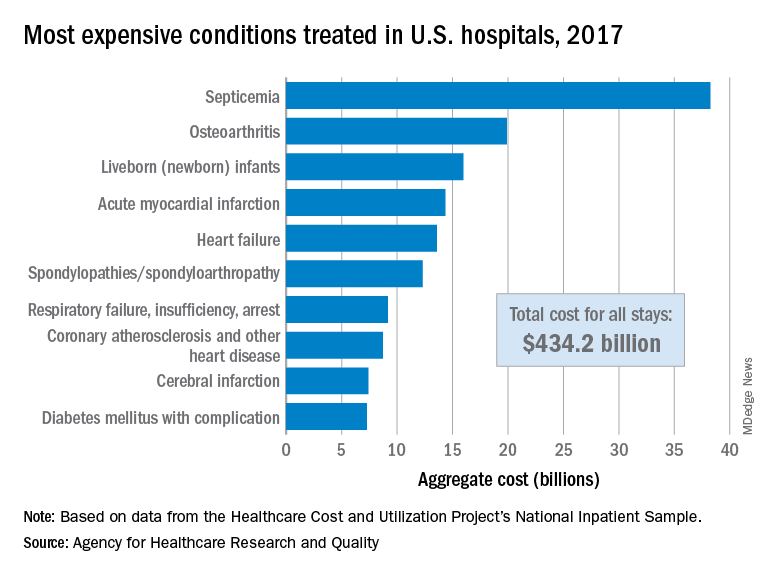

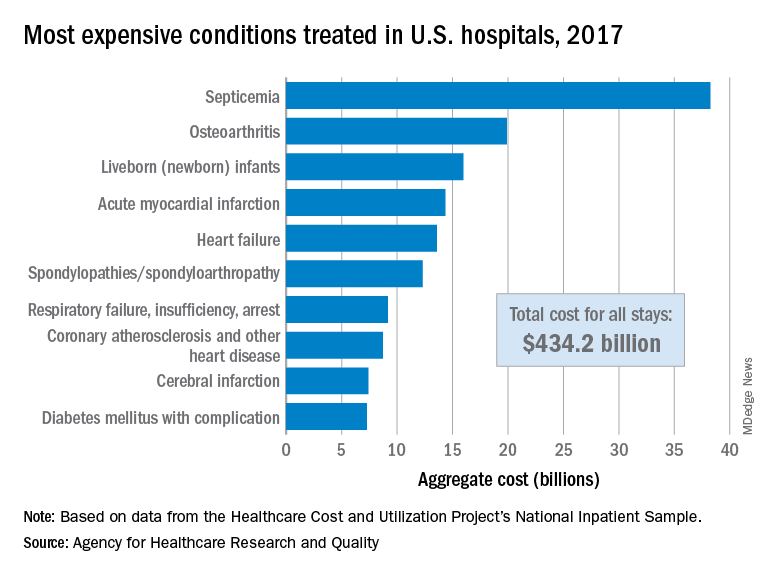

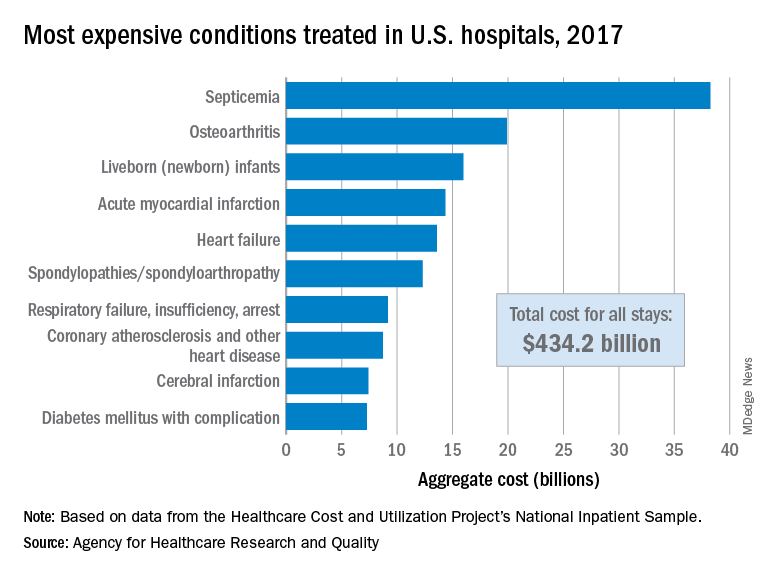

Septicemia first among hospital inpatient costs

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

Hepatitis screening now for all patients with cancer on therapy

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight gain persists as HIV-treatment issue

People living with HIV who put on extra pounds and develop metabolic syndrome or related disorders linked in part to certain antiretroviral agents remain a concern today, even as the drugs used to suppress HIV infection have evolved over the decades.

Linkage of HIV treatment with lipodystrophy and insulin resistance or diabetes began in the 1990s with protease inhibitors (Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Jun;30[suppl 2]:s135-42). Several reports over the years also tied any form of effective antiretroviral therapy to weight gain in HIV patients (Antivir Ther. 2012;17[7]:1281-9). More recently, reports have rattled the HIV-treatment community by associating alarmingly high levels of weight gain with a useful and relatively new drug, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) – a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) approved for use in the United States in late 2016, as well as certain agents from an entirely different antiretroviral therapy (ART) class, the integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). Both TAF and the INSTIs have come to play major roles in the HIV-treatment landscape, despite relevant and concerning recent weight gain observations with these drugs, such as in a 2019 meta-analysis of eight trials with 5,680 treatment-naive patients who started ART during 2003-2015 (Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 14;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz999).

“Weight gain is clearly seen in studies of dolutegravir [DTG] or bictegravir [BTG] with TAF,” wrote W.D. Francois Venter, PhD and Andrew Hill, PhD in a recent published commentary on the topic (Lancet HIV. 2020 Jun 1;7[6]:e389-400). Both DTG and BTG are INSTI class members.

“Excessive weight gain, defined as more than 10% over baseline, has recently been observed among people with HIV initiating or switching to regimens incorporating TAF, an INSTI, or both, particularly DTG,” wrote Jordan E. Lake, MD, an HIV specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, in a recent commentary posted online. Women and Black patients “are at even greater risk for excessive weight gain,” Dr. Lake added.

“In recent times, it has emerged that weight gain is more pronounced with the integrase inhibitor class of agents, especially dolutegravir and bictegravir, the so-called second-generation” INSTIs, said Anna Maria Geretti, MD, a professor of clinical infection, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Liverpool, England. ”The effect is more pronounced in women and people of non-White ethnicity, and is of concern because of the associated potential risk of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, etc.,” Dr. Geretti said in an interview.

The unprecedented susceptibility to weight gain seen recently in non-White women may in part have resulted from the tendency of many earlier treatment trials to have cohorts comprised predominantly of White men, Dr. Venter noted in an interview.

Alarming weight gains reported

Perhaps the most eye-popping example of the potential for weight gain with the combination of TAF with an INSTI came in a recent report from the ADVANCE trial, a randomized, head-to-head comparison of three regimens in 1,053 HIV patients in South Africa. After 144 weeks on a regimen of TAF (Vemlidy), DTG (Tivicay), and FTC (emtricitabine, Emtriva), another NRTI, women gained an averaged of more than 12 kg, compared with their baseline weight, significantly more than in two comparator groups, Simiso Sokhela, MB, reported at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS conference. The women in ADVANCE on the TAF-DTG-FTC regimen also had an 11% rate of incident metabolic syndrome during their first 96 weeks on treatment, compared with rates of 8% among patients on a different form of tenofovir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), along with DTG-FTC, and 5% among those on TDF–EFV (efavirenz, Sustiva)–FTC said Dr. Sokhela, an HIV researcher at Ezintsha, a division of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“We believe that these results support the World Health Organization guidelines that reserve TAF for only patients with osteoporosis or impaired renal function,” Dr. Sokhela said during a press briefing at the conference. The WHO guidelines list the first-line regimen as TDF-DTG-3TC (lamivudine; Epivir) or FTC. “The risk for becoming obese continued to increase after 96 weeks” of chronic use of these drugs, she added.

“All regimens are now brilliant at viral control. Finding the ones that don’t make patients obese or have other long-term side effects is now the priority,” noted Dr. Venter, a professor and HIV researcher at University of the Witwatersrand, head of Ezintsha, and lead investigator of ADVANCE. Clinicians and researchers have recently thought that combining TAF and an INSTI plus FTC or a similar NRTI “would be the ultimate regimen to replace the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)” such as EFV, “but now we have a major headache” with unexpectedly high weight gains in some patients, Dr. Venter said.

Weight gains “over 10 kg are unlikely to be acceptable in any circumstances, especially when starting body mass index is already borderline overweight,” wrote Dr. Venter along with Dr. Hill in their commentary. Until recently, many clinicians chalked up weight gain on newly begun ART as a manifestation of the patient’s “return-to-health,” but this interpretation “gives a positive spin to a potentially serious and common side effect,” they added.

More from ADVANCE

The primary efficacy endpoint of ADVANCE was suppression of viral load to less than 50 RNA copies/mL after 48 weeks on treatment, and the result showed that the TAF-DTG-FTC regimen and the TDF-DTG-FTC regimen were each noninferior to the control regimen of TDF-EFV-FTC (New Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 29;381[9]:803-15). Virtually all of the enrolled patients were Black, and 59% were women. Planned follow-up of all patients ran for 96 weeks. After 48 weeks, weight gain among the women averaged 6.4 kg, 3.2 kg, and 1.7 kg in the TAF-DTG, TDF-DTG, and TDF-EFV arms respectively. After 96 weeks, the average weight gains among women were 8.2 kg, 4.6 kg, and 3.2 kg, respectively, in new results reported by Dr. Sokhela at the IAC. Follow-up to 144 weeks was partial and included about a quarter of the enrolled women, with gains averaging 12.3 kg, 7.4 kg, and 5.5 kg respectively. The pattern of weight gain among men tracked the pattern in women, but the magnitude of gain was less. Among men followed for 144 weeks, average gain among those on TAF-DTG-FTC was 7.2 kg, the largest gain seen among men on any regimen and at any follow-up time in the study.

Dr. Sokhela also reported data on body composition analyses, which showed that the weight gains were largely in fat rather than lean tissue, fat accumulation was significantly greater in women than men, and that in both sexes fat accumulated roughly equally in the trunk and on limbs.

An additional analysis looked at the incidence of new-onset obesity among the women who had a normal body mass index at baseline. After 96 weeks, incident obesity occurred in 14% of women on the TAG-DTG-FTC regimen, 8% on TDF-DTG-FTC, and in 2% of women maintained on TDF-EFV-FTC, said Dr. Hill in a separate report at the conference.

Weight starts to weigh in

“I am very mindful of weight gain potential, and I talk to patients about it. It doesn’t determine what regimen I choose for a patient” right now, “but it’s only a matter of time before it starts influencing what we do, particularly if we can achieve efficacy with fewer drugs,” commented Babafemi O. Taiwo, MD, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at Northwestern University in Chicago. “I’ve had some patients show up with a weight gain of 20 kg, and that shouldn’t happen,” he said during a recent online educational session. Dr. Taiwo said his recent practice has been to warn patients about possible weight gain and to urge them to get back in touch with him quickly if it happens.

“Virologic suppression is the most important goal with ART, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services currently recommends INSTI-based ART for most PWH [people with HIV],” wrote Dr. Lake in April 2020. “I counsel all PWH initiating ART about the potential for weight gain, and I discuss their current diet and healthy lifestyle habits. I explain to patients that we will monitor their weight, and if weight gain seems more than either of us are comfortable with then we will reassess. Only a small percentage of patients experience excessive weight gain after starting ART.” Dr. Lake also stressed that she had not yet begun to change the regimen a patient is on solely because of weight gain. “We do not know whether this weight gain is reversible,” she noted.

“I do not anticipate that a risk of weight gain at present will dictate a change in guidelines,” said Dr. Geretti. “Drugs such as dolutegravir and bictegravir are very effective, and they are unlikely to cause drug resistance. Further data on the mechanism of weight gain and the reversibility after a change of treatment will help refine drug selection in the near future,” she predicted.

“I consider weight gain when prescribing because my patients hear about this. It’s a side effect that my patients really care about, and I don’t blame them,” said Lisa Hightow-Weidman, MD, a professor and HIV specialist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, during an on-line educational session. “If you don’t discuss it with a patient and then weight gain happens and the patient finds out [the known risk from their treatment] they may have an issue,” she noted. But weight gain is not a reason to avoid these drugs. “They are great medications in many ways, with once-daily regimens and few side effects.”

Weight gain during pregnancy a special concern

An additional analysis of data from ADVANCE presented at the conference highlighted what the observed weight gain on ART could mean for women who become pregnant while on treatment. Based on a systematic literature review, the ADVANCE investigators calculated the relative risk for six obesity-related pregnancy complications, compared with nonobese women: preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and caesarean delivery. Based on the obesity changes among women on their assigned ART in ADVANCE, the researchers calculated the predicted incidence of these six complications. The analysis showed that for every 1,000 women, those on TAG-DTG-FTC would have an excess of 53 obesity-related pregnancy complications, those on TDF-DTG-FTC would develop 28 excess pregnancy complications, and those on TDG-EFV-FTC would have four excess complications, reported Dr. Hill at the International AIDS conference.

The researchers also ran a similar simulation for the incidence of neonatal complications that could result when mothers are obese because of their ART. The six neonatal complications included in this analysis were small for gestational age, large for gestational age, macrosomia, neonatal death, stillbirth, and neural tube defects. Based on the excess rate of incident obesity, they calculated that for every 1,000 pregnancies women on TAD-DTG-FTC would have 24 additional infants born with one of these complications, women on TDF-DTG-FTC would have an excess of 13 of these events, and women on TDG-EFV-FTC would have an excess of three such obesity-related neonatal complications, Dr. Hill said.

Sorting out the drugs

Results from several additional studies reported at the conference have started trying to discern exactly which ART drugs and regimens pose the greatest weight gain risk and which have the least risk while retaining high efficacy and resistance barriers.

Further evidence implicating any type of ART as a driver of increased weight came from a review of 8,256 adults infected with HIV and members of the Kaiser Permanente health system in three U.S. regions during 2000-2016. Researchers matched these cases using several demographic factors with just under 130,000 members without HIV. Those infected by HIV had half the prevalence of obesity as the matched controls at baseline. During 12 years of follow-up, those infected with HIV had a threefold higher rate of weight gain than those who were uninfected. Annual weight gain averaged 0.06 kg/year among the uninfected people and 0.22 kg/year among those infected with HIV, a statistically significant difference that was consistent regardless of whether people started the study at a normal body mass index, overweight, or obese, reported Michael J. Silverberg, PhD, an epidemiologist with Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif.

Another study tried to focus on the weight gain impact when patients on three-drug ART regimens changed from taking TDF to TAF. This analysis used data collected in the OPERA (Observational Pharmaco-Epidemiology Research & Analysis) longitudinal cohort of about 115,000 U.S. PWH. The observational cohort included nearly 7,000 patients who made a TDF-to-TAF switch, including 3,288 patients who maintained treatment during this switch with an INSTI, 1,454 who maintained a background regimen based on a NNRTI, 1,430 patients who also switched from an INSTI to a different drug, and 747 patients maintained on a boosted dose of a protease inhibitor. All patients were well controlled on their baseline regimen, with at least two consecutive measures showing undetectable viral load.

Patients who maintained their background regimens while changing from TDF to TAF had a 2.0-2.6 kg increase in weight during the 9 months immediately following their switch to TAF, reported Patrick Mallon, MB, a professor of microbial diseases at University College Dublin. Among the patients who both switched to TAF and also switched to treatment with an INSTI, weight gain during the 9 months after the switch averaged 2.6-4.5 kg, depending on which INSTI was started. Patients who switched to treatment with elvitegravir/cobicistat (an INSTI plus a boosting agent) averaged a gain of 2.6 kg during 9 months, those who switched to DTG averaged a 3.1-kg gain, and those who switched to BTG averaged a 4.6-kg increase, Dr. Mallon reported at the conference.

These findings “give us a good sense that the weight gain is real. This is not just overeating or not exercising, but weight changes coincidental with a change in HIV treatment,” commented David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine and site leader of the HIV Prevention and Treatment Clinical Trials Unit at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, during an online educational session.

Contrary to this evidence suggesting a consistent uptick in weight when patients start TAF treatment was a recent report on 629 HIV patients randomized to treatment with TAF-BTG-FTC or abacavir (an NRTI, Ziagen)–DTG-3TC, which found similar weight gains between these two regimens after 144 weeks on treatment (Lancet HIV. 2020 Jun;7[6]:e389-400). This finding had the effect of “strengthening the argument that TAF is simply an innocent bystander” and does not play a central role in weight gain, and supporting the notion that the alternative tenofovir formulation, TDF, differs from TAF by promoting weight loss, Dr. Venter and Dr. Hill suggested in their commentary that accompanied this report.

The new findings from Dr. Mallon raise “serious questions about the way we have moved to TAF as a replacement for TDF, especially because the benefits [from TAF] are for a small subgroup – patients with renal disease or osteoporosis,” Dr. Venter said in an interview. “The question is, will we see weight gain like this” if TAF was combined with a non-INSTI drug? he wondered.

While some study results have suggested a mitigating effect from TDF on weight gain, that wasn’t the case in the AFRICOS (African Cohort Study) study of 1,954 PWH who started treatment with TDF-DTG-FTC (742 patients) or a different three-drug regimen. After a median of 225 days on treatment, those who started on TDF-DTG-FTC had an adjusted, 85% higher rate of developing a high body mass index, compared with patients on a different ART regimen, Julie Ake, MD, reported in a talk at the conference. Her conclusion focused on the possible involvement of DTG: “Consistent with previous reports, dolutegravir was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing high body mass index,” said Dr. Ake, director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program in Bethesda, Md. and leader of AFRICOS.

A potential workaround to some drugs that cause excessive the weight gain is to just not use them. That was part of the rationale for the TANGO study, which took 741 HIV-infected patients with successful viral suppression on a regimen of TAF-FTC plus one or two additional agents and switched half of them to a TAF-less, two-drug regimen of DTG-FTC. This open-label study’s primary endpoint was noninferiority for viral suppression of the DTG-FTC regimen, compared with patients who stayed on their starting regimen, and the results proved that DTG-FTC was just as effective over 48 weeks for this outcome (Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1243).

At the conference, TANGO’s lead investigator, Jean van Wyk, MD, reported the weight and metabolic effects of the switch. The results showed a similar and small weight gain (on average less than 1 kg) during 48 week follow-up regardless of whether patients remained on their baseline, TAF-containing regimen or switched to DTG-FTC, said Dr. van Wyk, global medical lead for HIV treatment at Viiv Healthcare, the company that markets DTG. About three-quarters of patients in both arms received “boosted” dosages of their drugs, and in this subgroup, patients on DTG-FTC showed statistically significant benefits in several lipid levels, fasting glucose level, and in their degree of insulin resistance. Dr. van Wyk said. These between-group differences were not statistically significant among the “unboosted” patients, and the results failed to show a significant between-group difference in the incidence of metabolic syndrome.

Dr. Venter called these results “exciting,” and noted that he already uses the DTG-FTC two-drug combination “a lot” to treat PWH and renal disease.

A second alternative regimen showcased in a talk at the conference used the three-drug regimen of TDF-FTC plus the NNRTI, DOR (doravirine, Pifeltro). The DRIVE-SHIFT trial enrolled 670 HIV patients with successfully suppressed viral load on conventional regimens who were either switched to TDF-DOR-FTC or maintained on their baseline treatment. After 48 weeks, results confirmed the primary efficacy endpoint of noninferiority for maintenance of suppression with the investigational regimen (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019 Aug;81[4]:463-72).

A post-hoc analysis looked at weight changes among these patients after as much as 144 weeks of follow-up. The results showed that patients switched to TDF-DOR-FTC had an average weight increase of 1.2-1.4 kg after more than 2 years on the new regimen, with fewer than 10% of patients having a 10% or greater weight gain with DOR, a “next-generation” NNRTI, reported Princy N. Kumar, MD, professor at Georgetown University and chief of infectious diseases at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington. “Weight gain was minimal, even over the long term,” she noted.

The tested DOR-based regimen also looks “very exciting,” but the populations it’s been tested have also been largely limited to White men, and limited data exist about the regimen’s performance in pregnant women, commented Dr. Venter. The DRIVE-SHIRT patient cohort was about 85% men, and about three-quarters White.

More weight data needed

HIV-treatment researchers and clinicians seem agreed that weight gain and other metabolic effects from HIV treatment need more assessment and evidence because current data, while suggestive, is also inconclusive.

“Clinical trials are desperately needed to understand the mechanisms of and potential therapeutic options for excessive weight gain on ART,” wrote Dr. Lake in her commentary in April. “While more research is needed,” the new data reported at the virtual International AIDS conference “get us closer to understanding the effects of integrase inhibitors and TAF on weight and the potential metabolic consequences,” she commented as chair of the conference session where these reports occurred.

“Further data on the mechanism of weight gain and its reversibility after a change of treatment will help refine drug selection in the near future,” predicted Dr. Geretti.

“It’s hard to understand physiologically how drugs from such different classes all seem to have weight effects; it’s maddening,” said Dr. Venter. “We need decent studies in all patient populations. That will now be the priority,” he declared. “Patients shouldn’t have to choose” between drugs that most effectively control their HIV infection and drugs that don’t pose a risk for weight gain or metabolic derangements. PWH “should not have to face obesity as their new epidemic,” he wrote with Dr. Hill.

ADVANCE was funded in part by Viiv, the company that markets dolutegravir (Tivicay), and received drugs supplied by Gilead and Viiv. TANGO was sponsored by Viiv. DRIVE-SHIFT was funded by Merck, the company that markets doravirine (Pifeltro). Dr. Lake, Dr. Sokhela, Dr. Ake, and Dr. Kumar had no disclosures, Dr. Venter has received personal fees from Adcock Ingraham, Aspen Healthcare, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Mylan, Roche, and Viiv. Dr. Hill has received payments from Merck. Dr. Geretti has received honoraria and research funding from Gilead, Jansse, Roche, and Viiv. Dr. Taiwo has had financial relationships with Gilead, Janssen, and Viiv. Dr. Hightow-Weidman has received honoraria from Gilead and Jansse. Dr. Wohl has been a consultant to Gilead, Johnson and Johnson, and Merck. Dr. Silverberg received research funding from Gilead. Dr. Mallon has been an advisor to and speaker on behalf of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cilag, Gilead, Jansse, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Viiv. Dr. van Wyk is a Viiv employee.

People living with HIV who put on extra pounds and develop metabolic syndrome or related disorders linked in part to certain antiretroviral agents remain a concern today, even as the drugs used to suppress HIV infection have evolved over the decades.

Linkage of HIV treatment with lipodystrophy and insulin resistance or diabetes began in the 1990s with protease inhibitors (Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Jun;30[suppl 2]:s135-42). Several reports over the years also tied any form of effective antiretroviral therapy to weight gain in HIV patients (Antivir Ther. 2012;17[7]:1281-9). More recently, reports have rattled the HIV-treatment community by associating alarmingly high levels of weight gain with a useful and relatively new drug, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) – a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) approved for use in the United States in late 2016, as well as certain agents from an entirely different antiretroviral therapy (ART) class, the integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). Both TAF and the INSTIs have come to play major roles in the HIV-treatment landscape, despite relevant and concerning recent weight gain observations with these drugs, such as in a 2019 meta-analysis of eight trials with 5,680 treatment-naive patients who started ART during 2003-2015 (Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 14;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz999).

“Weight gain is clearly seen in studies of dolutegravir [DTG] or bictegravir [BTG] with TAF,” wrote W.D. Francois Venter, PhD and Andrew Hill, PhD in a recent published commentary on the topic (Lancet HIV. 2020 Jun 1;7[6]:e389-400). Both DTG and BTG are INSTI class members.

“Excessive weight gain, defined as more than 10% over baseline, has recently been observed among people with HIV initiating or switching to regimens incorporating TAF, an INSTI, or both, particularly DTG,” wrote Jordan E. Lake, MD, an HIV specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, in a recent commentary posted online. Women and Black patients “are at even greater risk for excessive weight gain,” Dr. Lake added.

“In recent times, it has emerged that weight gain is more pronounced with the integrase inhibitor class of agents, especially dolutegravir and bictegravir, the so-called second-generation” INSTIs, said Anna Maria Geretti, MD, a professor of clinical infection, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Liverpool, England. ”The effect is more pronounced in women and people of non-White ethnicity, and is of concern because of the associated potential risk of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, etc.,” Dr. Geretti said in an interview.

The unprecedented susceptibility to weight gain seen recently in non-White women may in part have resulted from the tendency of many earlier treatment trials to have cohorts comprised predominantly of White men, Dr. Venter noted in an interview.

Alarming weight gains reported

Perhaps the most eye-popping example of the potential for weight gain with the combination of TAF with an INSTI came in a recent report from the ADVANCE trial, a randomized, head-to-head comparison of three regimens in 1,053 HIV patients in South Africa. After 144 weeks on a regimen of TAF (Vemlidy), DTG (Tivicay), and FTC (emtricitabine, Emtriva), another NRTI, women gained an averaged of more than 12 kg, compared with their baseline weight, significantly more than in two comparator groups, Simiso Sokhela, MB, reported at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS conference. The women in ADVANCE on the TAF-DTG-FTC regimen also had an 11% rate of incident metabolic syndrome during their first 96 weeks on treatment, compared with rates of 8% among patients on a different form of tenofovir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), along with DTG-FTC, and 5% among those on TDF–EFV (efavirenz, Sustiva)–FTC said Dr. Sokhela, an HIV researcher at Ezintsha, a division of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“We believe that these results support the World Health Organization guidelines that reserve TAF for only patients with osteoporosis or impaired renal function,” Dr. Sokhela said during a press briefing at the conference. The WHO guidelines list the first-line regimen as TDF-DTG-3TC (lamivudine; Epivir) or FTC. “The risk for becoming obese continued to increase after 96 weeks” of chronic use of these drugs, she added.

“All regimens are now brilliant at viral control. Finding the ones that don’t make patients obese or have other long-term side effects is now the priority,” noted Dr. Venter, a professor and HIV researcher at University of the Witwatersrand, head of Ezintsha, and lead investigator of ADVANCE. Clinicians and researchers have recently thought that combining TAF and an INSTI plus FTC or a similar NRTI “would be the ultimate regimen to replace the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)” such as EFV, “but now we have a major headache” with unexpectedly high weight gains in some patients, Dr. Venter said.

Weight gains “over 10 kg are unlikely to be acceptable in any circumstances, especially when starting body mass index is already borderline overweight,” wrote Dr. Venter along with Dr. Hill in their commentary. Until recently, many clinicians chalked up weight gain on newly begun ART as a manifestation of the patient’s “return-to-health,” but this interpretation “gives a positive spin to a potentially serious and common side effect,” they added.

More from ADVANCE

The primary efficacy endpoint of ADVANCE was suppression of viral load to less than 50 RNA copies/mL after 48 weeks on treatment, and the result showed that the TAF-DTG-FTC regimen and the TDF-DTG-FTC regimen were each noninferior to the control regimen of TDF-EFV-FTC (New Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 29;381[9]:803-15). Virtually all of the enrolled patients were Black, and 59% were women. Planned follow-up of all patients ran for 96 weeks. After 48 weeks, weight gain among the women averaged 6.4 kg, 3.2 kg, and 1.7 kg in the TAF-DTG, TDF-DTG, and TDF-EFV arms respectively. After 96 weeks, the average weight gains among women were 8.2 kg, 4.6 kg, and 3.2 kg, respectively, in new results reported by Dr. Sokhela at the IAC. Follow-up to 144 weeks was partial and included about a quarter of the enrolled women, with gains averaging 12.3 kg, 7.4 kg, and 5.5 kg respectively. The pattern of weight gain among men tracked the pattern in women, but the magnitude of gain was less. Among men followed for 144 weeks, average gain among those on TAF-DTG-FTC was 7.2 kg, the largest gain seen among men on any regimen and at any follow-up time in the study.

Dr. Sokhela also reported data on body composition analyses, which showed that the weight gains were largely in fat rather than lean tissue, fat accumulation was significantly greater in women than men, and that in both sexes fat accumulated roughly equally in the trunk and on limbs.

An additional analysis looked at the incidence of new-onset obesity among the women who had a normal body mass index at baseline. After 96 weeks, incident obesity occurred in 14% of women on the TAG-DTG-FTC regimen, 8% on TDF-DTG-FTC, and in 2% of women maintained on TDF-EFV-FTC, said Dr. Hill in a separate report at the conference.

Weight starts to weigh in

“I am very mindful of weight gain potential, and I talk to patients about it. It doesn’t determine what regimen I choose for a patient” right now, “but it’s only a matter of time before it starts influencing what we do, particularly if we can achieve efficacy with fewer drugs,” commented Babafemi O. Taiwo, MD, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at Northwestern University in Chicago. “I’ve had some patients show up with a weight gain of 20 kg, and that shouldn’t happen,” he said during a recent online educational session. Dr. Taiwo said his recent practice has been to warn patients about possible weight gain and to urge them to get back in touch with him quickly if it happens.

“Virologic suppression is the most important goal with ART, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services currently recommends INSTI-based ART for most PWH [people with HIV],” wrote Dr. Lake in April 2020. “I counsel all PWH initiating ART about the potential for weight gain, and I discuss their current diet and healthy lifestyle habits. I explain to patients that we will monitor their weight, and if weight gain seems more than either of us are comfortable with then we will reassess. Only a small percentage of patients experience excessive weight gain after starting ART.” Dr. Lake also stressed that she had not yet begun to change the regimen a patient is on solely because of weight gain. “We do not know whether this weight gain is reversible,” she noted.

“I do not anticipate that a risk of weight gain at present will dictate a change in guidelines,” said Dr. Geretti. “Drugs such as dolutegravir and bictegravir are very effective, and they are unlikely to cause drug resistance. Further data on the mechanism of weight gain and the reversibility after a change of treatment will help refine drug selection in the near future,” she predicted.

“I consider weight gain when prescribing because my patients hear about this. It’s a side effect that my patients really care about, and I don’t blame them,” said Lisa Hightow-Weidman, MD, a professor and HIV specialist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, during an on-line educational session. “If you don’t discuss it with a patient and then weight gain happens and the patient finds out [the known risk from their treatment] they may have an issue,” she noted. But weight gain is not a reason to avoid these drugs. “They are great medications in many ways, with once-daily regimens and few side effects.”

Weight gain during pregnancy a special concern