User login

Median Income and Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Persons With COVID-19 at an Urban Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Median Income and Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Persons With COVID-19 at an Urban Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Large epidemiologic studies have shown disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES). Racial and ethnic minorities and individuals of lower SES have experienced disproportionately higher rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death. In Washington, DC, Black individuals (47% of the population) accounted for 51% of COVID-19 cases and 75% of deaths. In comparison, White individuals (41% of the population) accounted for 21% of cases and 11% of deaths.1 Place of residence, such as living in socially vulnerable communities, has also been shown to be associated with higher rates of COVID-19 mortality and lower vaccination rates.2-4 Social and structural inequities, such as limited access to health care services and mistrust of the health care system, may explain some of the observed disparities.5 However, data are limited regarding COVID-19 outcomes for individuals with equal access to care.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system and operates 123 acute care hospitals. Previous research has demonstrated that disparities in outcomes for other diseases are attenuated or erased among veterans receiving VHA care.6,7 Based on literature from the pandemic, markers of health care inequity relating to SES (eg, place of residence, median income) are expected to impact the outcomes of patients acutely hospitalized with COVID-19.4 We hypothesized that the impact on clinical outcomes of infection would be mitigated for veterans receiving VHA care.

This retrospective cohort study included veterans who presented to Washington Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WVAMC) with the goal of determining whether place of residence as a marker of SES, health care access, and median income were predictive of COVID-19 disease severity.

Methods

The WVAMC serves about 125,000 veterans across the metropolitan area, including parts of Maryland and Virginia. It is a high-complexity hospital with 164 acute care beds, 30 psychosocial residential rehabilitation beds, and an adjacent 120-bed community living center providing long-term, hospice, and palliative care.8

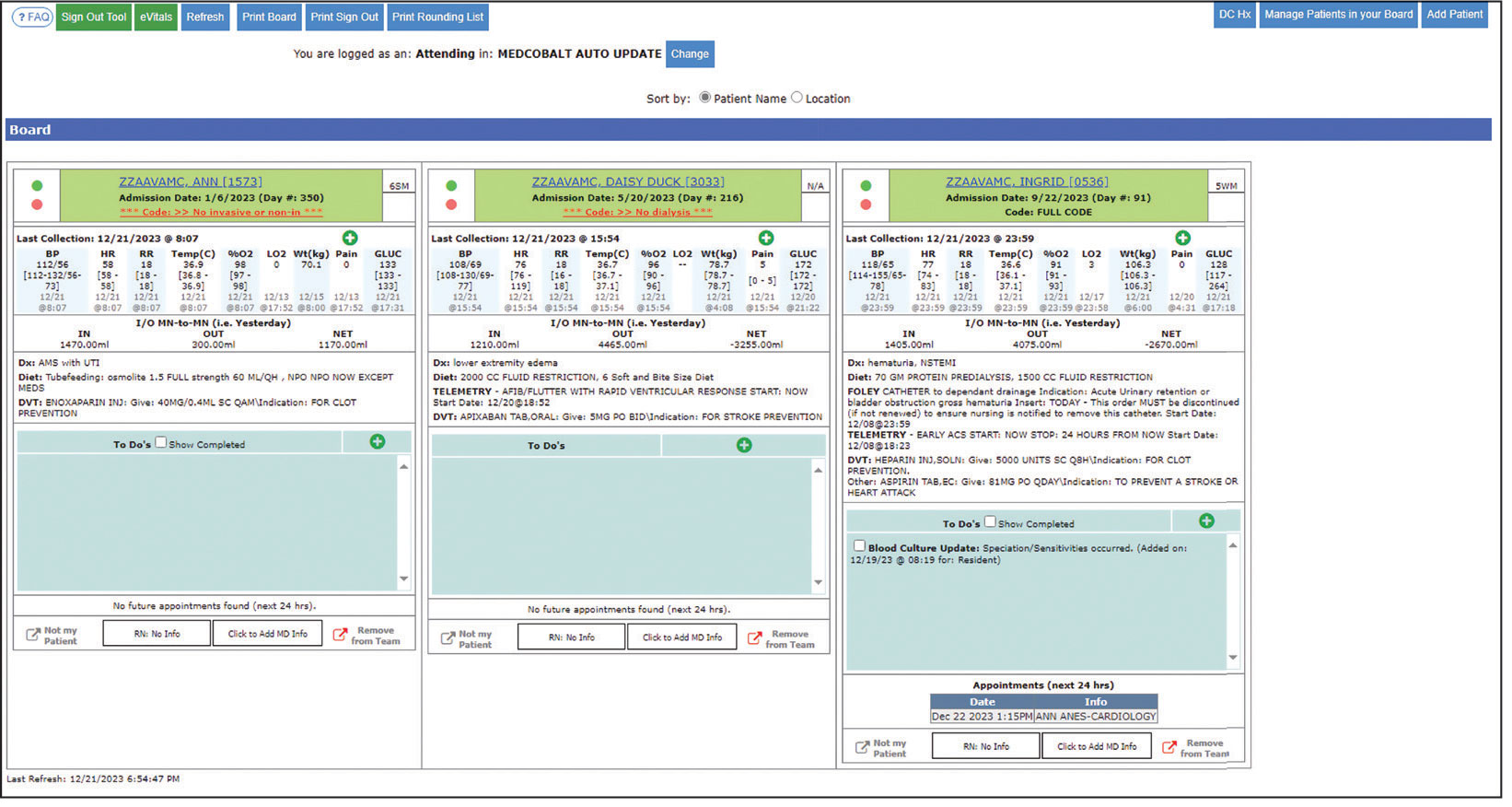

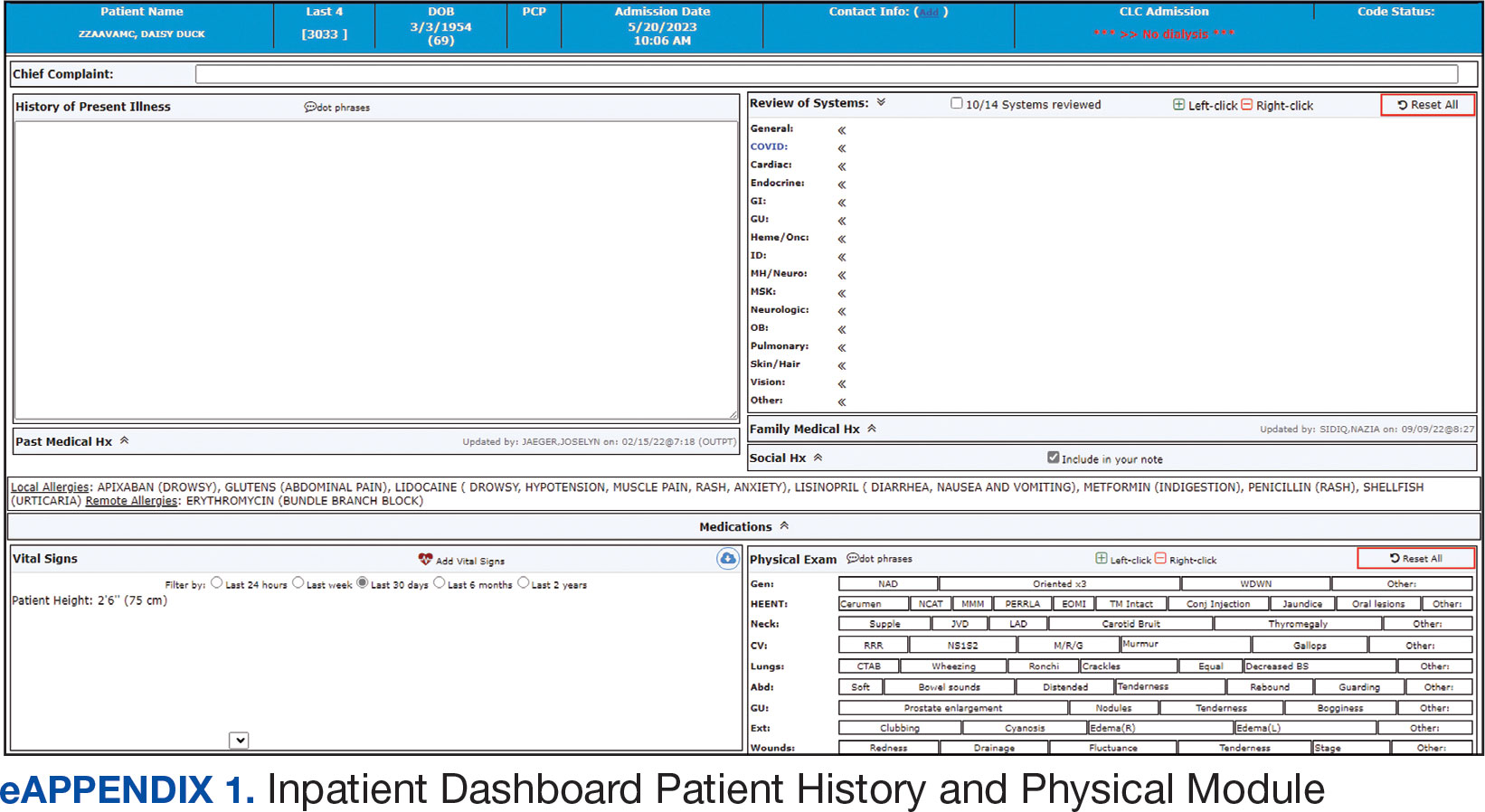

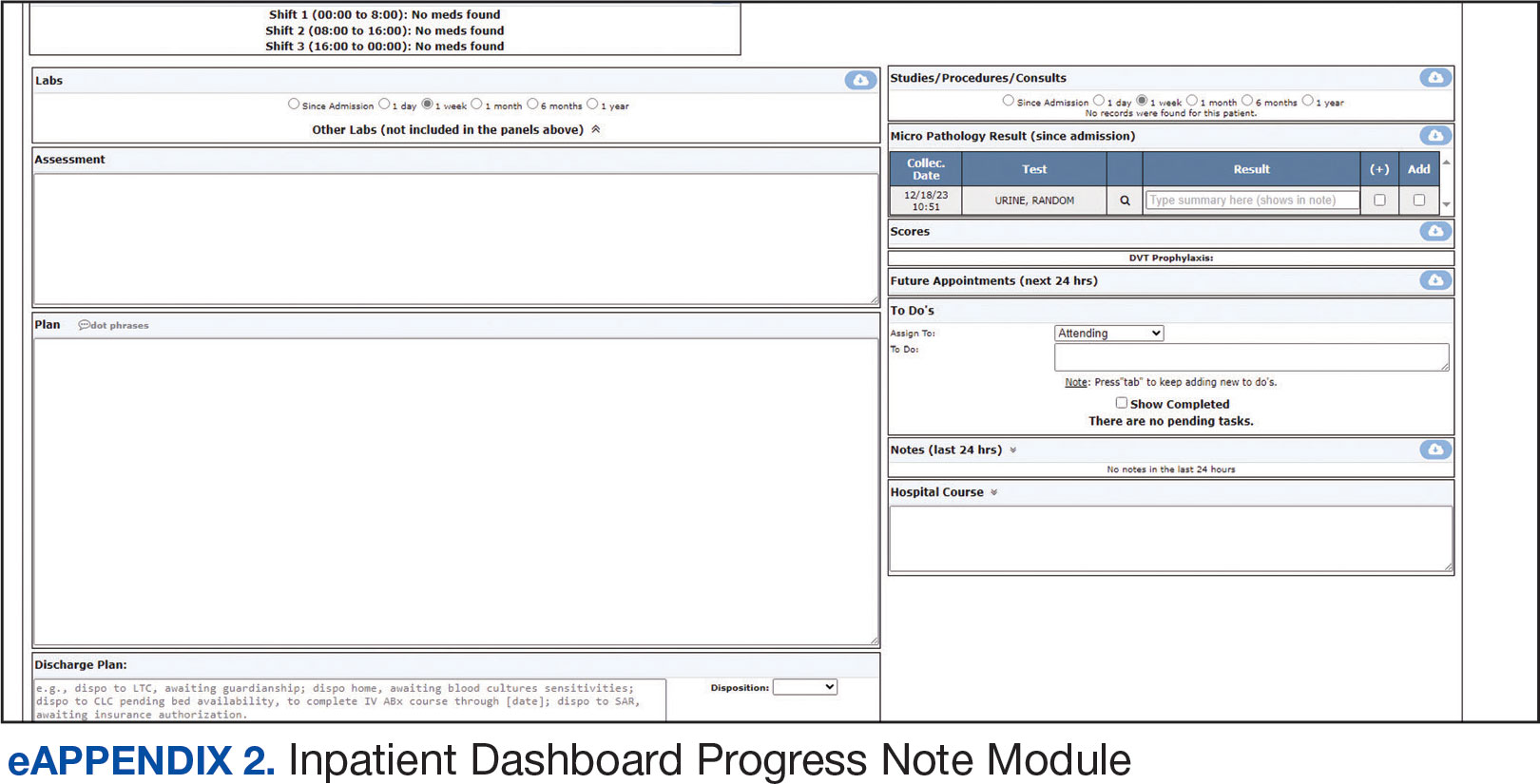

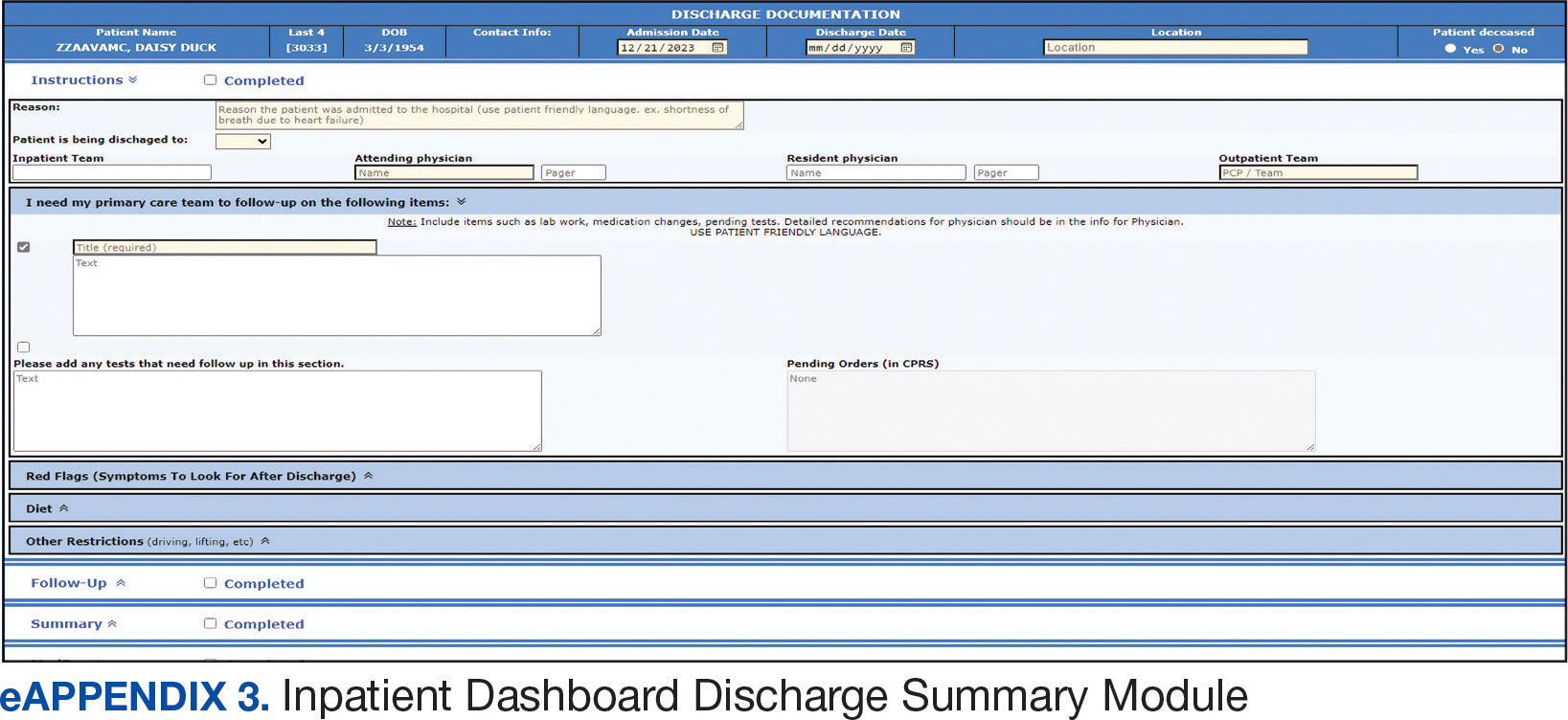

The WVAMC developed a dashboard that tracked patients with COVID-19 through on-site testing by admission date, ward, and other key demographics (PowerBi, Corporate Data Warehouse). All patients admitted to WVAMC with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, were included in this retrospective review. Using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the dashboard, we collected demographic information, baseline clinical diagnoses, laboratory results, and clinical interventions for all patients with documented COVID-19 infection as established by laboratory testing methods available at the time of diagnosis. Veterans treated exclusively outside the WVAMC were excluded. Hospitalization was defined as any acute inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before and 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test. Home testing kits were not widely available during the study period. An ICU stay was defined as any inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before or 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test for which the ward location had the specialty of medical or surgical ICU. Death due to COVID-19 was defined as occurring within 42 days (6 weeks) of a positive COVID-19 test.9 This definition assumed that during the peak of the pandemic, COVID-19 was the attributable cause of death, despite the possible contribution of underlying health conditions.

Patients’ admission periods were based on US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) national data and classified as early 2020 (January 2020–April 2020), mid-2020 (May 2020–August 2020), late 2020 (September 2020–December 2020), and early 2021 (January 2021–April 2021).10 We chose to use these time periods as surrogates for the frequent changes in circulating COVID-19 variants, surges in case numbers, therapies and interventions available during the pandemic. The dominant COVID-19 variant during the study period was Alpha (B.1.17). Beta (B.1.351) variants were circulating infrequently, and Delta and Omicron appeared after the study period.11 Treatment strategies evolved rapidly with emerging evidence, including the use of dexamethasone, beginning in June 2020.12 WVAMC followed the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidance on vaccination rollout beginning in December 2020.13

Patients' income was estimated by the median household income of the zip code residence based on US Census Bureau 2021 estimates and was assessed as both a continuous and categorical variable.14 The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was included in models as a continuous variable.15 Variables contributing to the CCI include myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, hemiplegia or paraplegia, ulcer disease, hepatic disease, diabetes (with or without end-organ damage), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), connective tissue disease, leukemia, lymphoma, moderate or severe renal disease, solid tumor (with or without metastases), and HIV/AIDS. The WVAMC Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB #1573071).

Variables

This study assessed 3 primary outcomes as indicators of disease severity during hospitalization: need for high-flow oxygen (HFO), intubation, and presumed mortality at any time during hospitalization. The following variables were collected as potential social determinants or clinical risk-adjustment predictors of disease severity outcomes: age; sex; race and ethnicity; median income for patient’s zip code residence, state, and county; wards within Washington, DC; comorbidities, CCI; tobacco use; and body mass index.15 Although medications at baseline, treatments during hospitalization for COVID-19, and laboratory parameters during hospitalization are shown in eAppendices 1 and 2, they are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Three types of logistic regression models were calculated for predicting the disease severity outcomes: (1) simple unadjusted models; (2) models predicting from single variables plus age (age-adjusted); and (3) multivariable models using all nonredundant potential predictors with adequate sample sizes (multivariable). Variables were considered to have inadequate sample sizes if there was nontrivial missing data or small numbers within categories, (eg, AIDS, connective tissue disease). Potential predictors for the multivariable model included age, sex, race, median income by zip code residence, CCI, CDC admission period, obesity, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), diabetes, COPD or asthma, liver disease, antibiotics, and acute kidney injury.

For the multivariable models, the following modifications were made to avoid unreliable parameter estimation and computation problems (quasi-separation): age and CCI were included as continuous rather than categorical variables. Race was recoded as a 2-category variable (Black vs other [White, Hispanic, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander]), and ethnicity was excluded because of the small number of patients in this group (n = 16). Admission period was included. Predicted probability plots were generated for each outcome with continuous independent predictors (income and CCI), both unadjusted and adjusted for age as a continuous covariate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Heat Maps

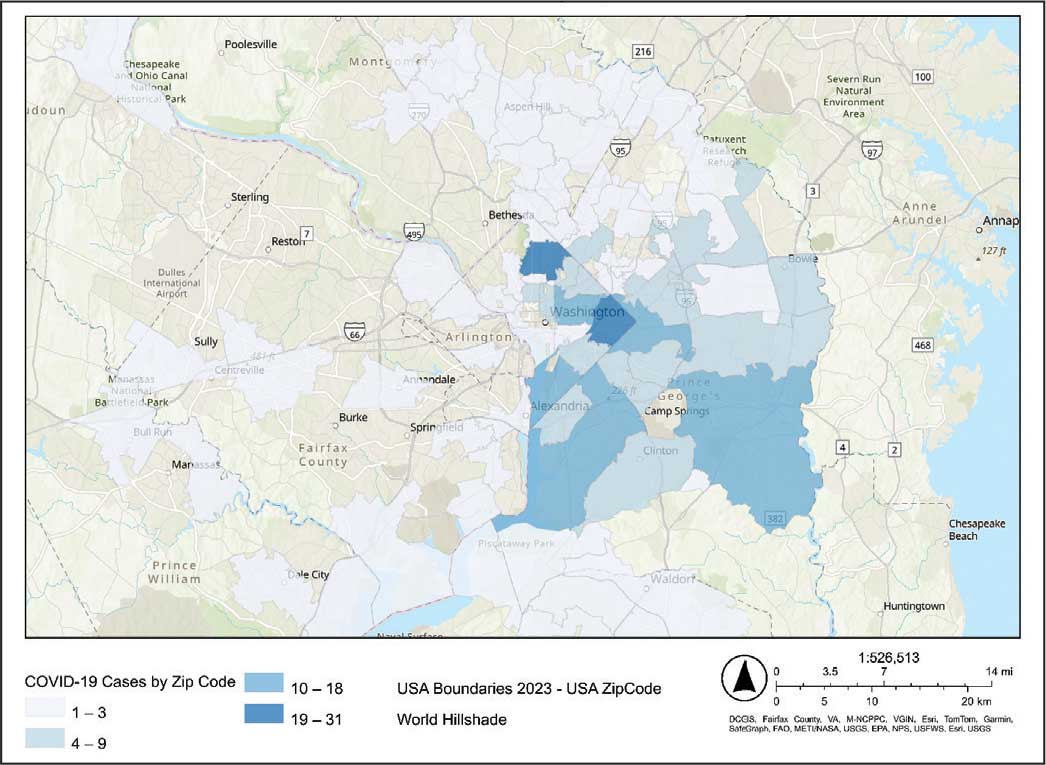

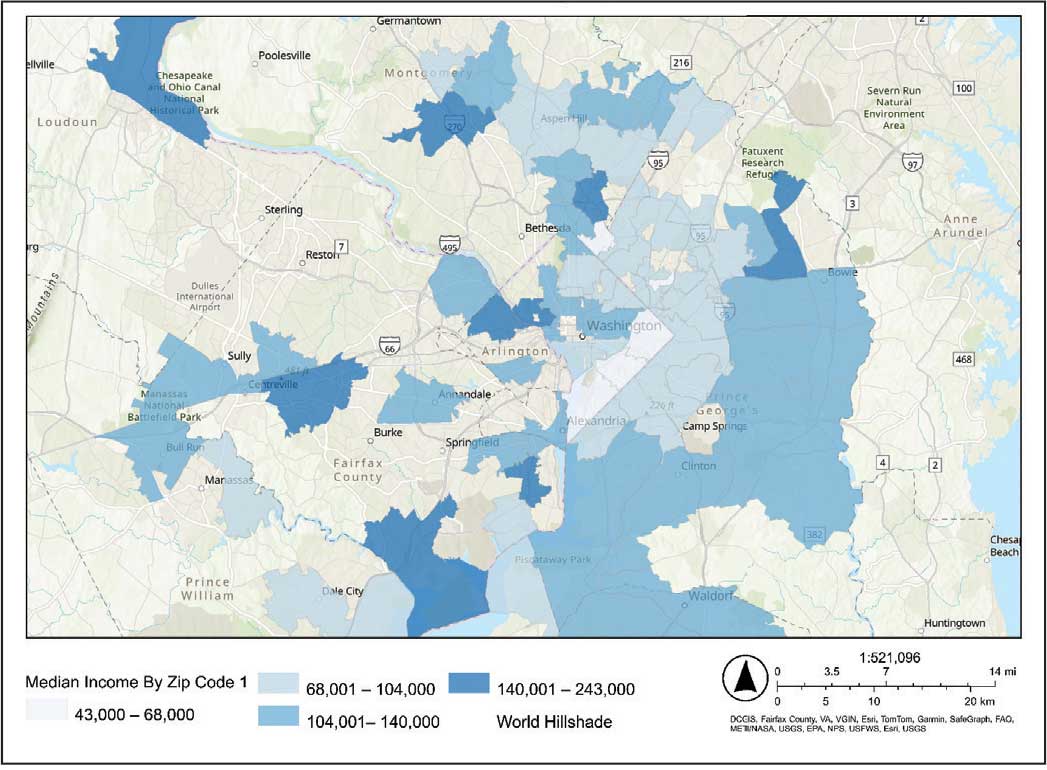

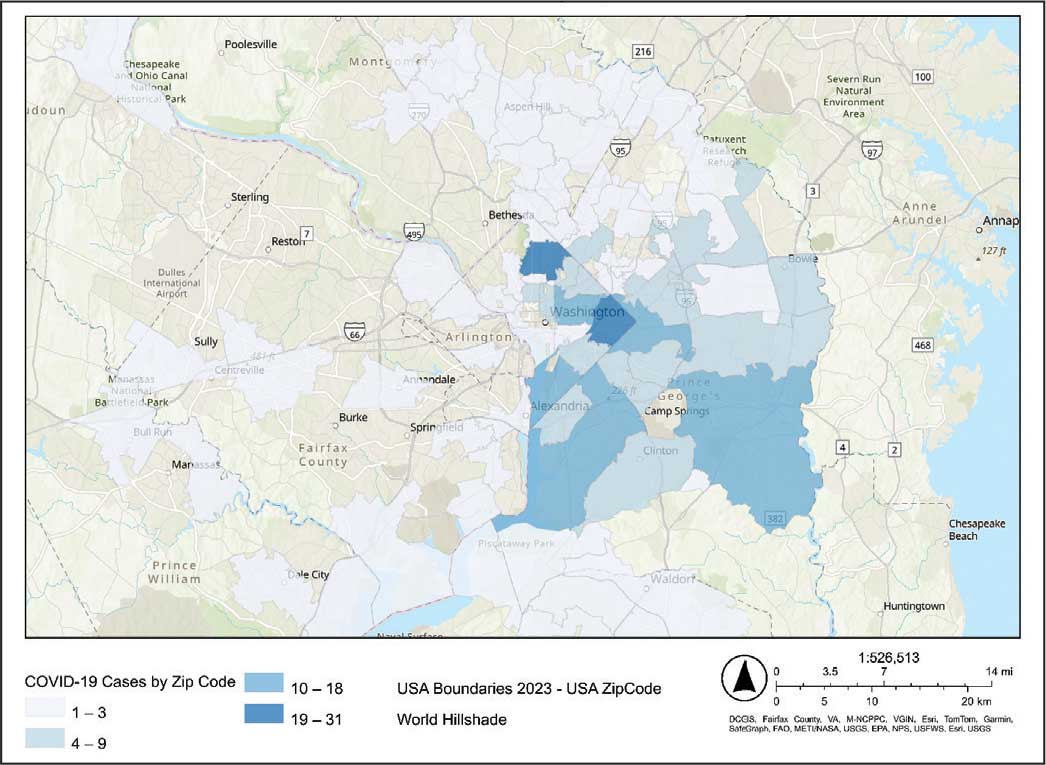

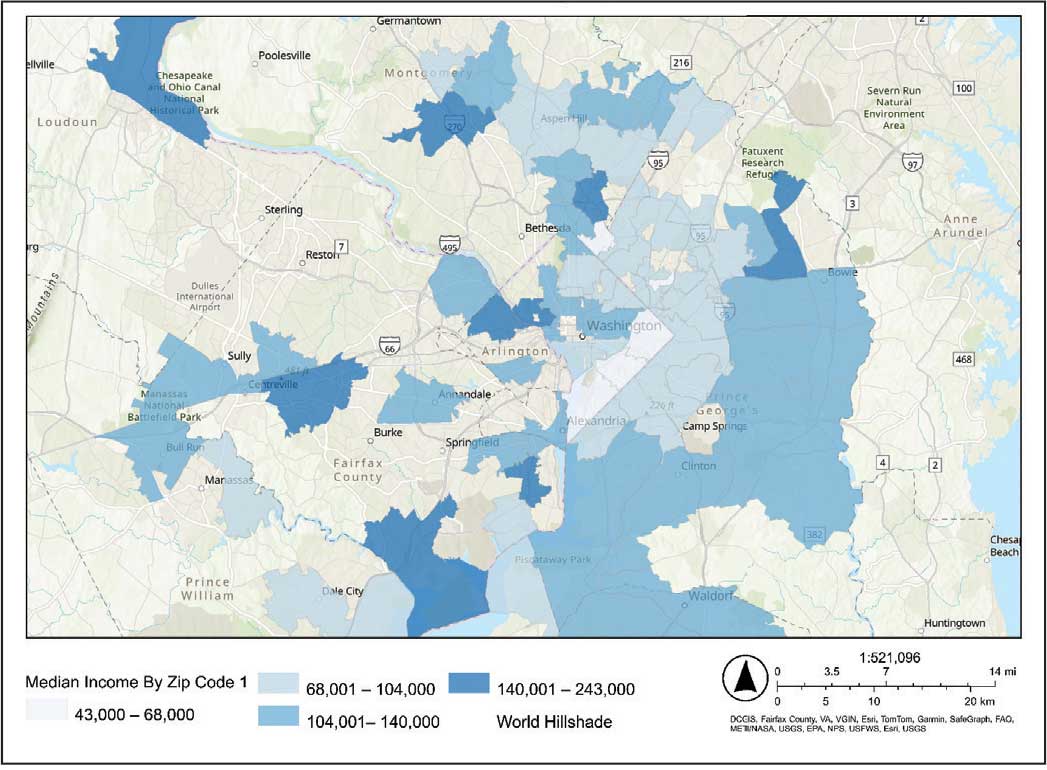

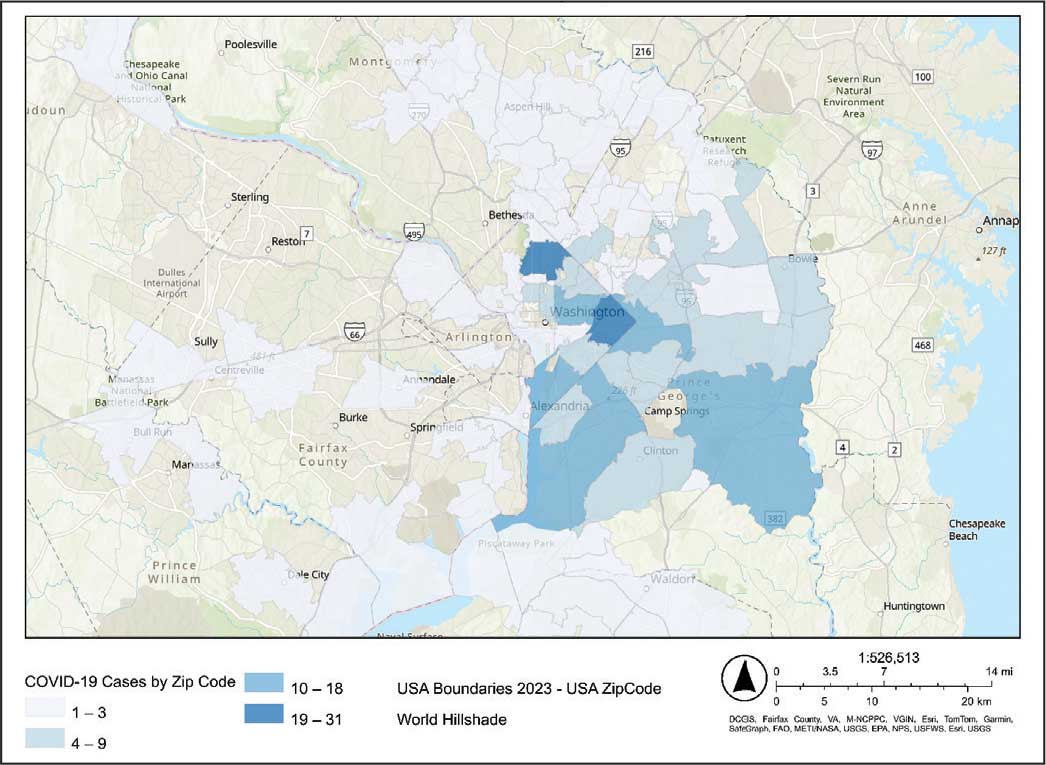

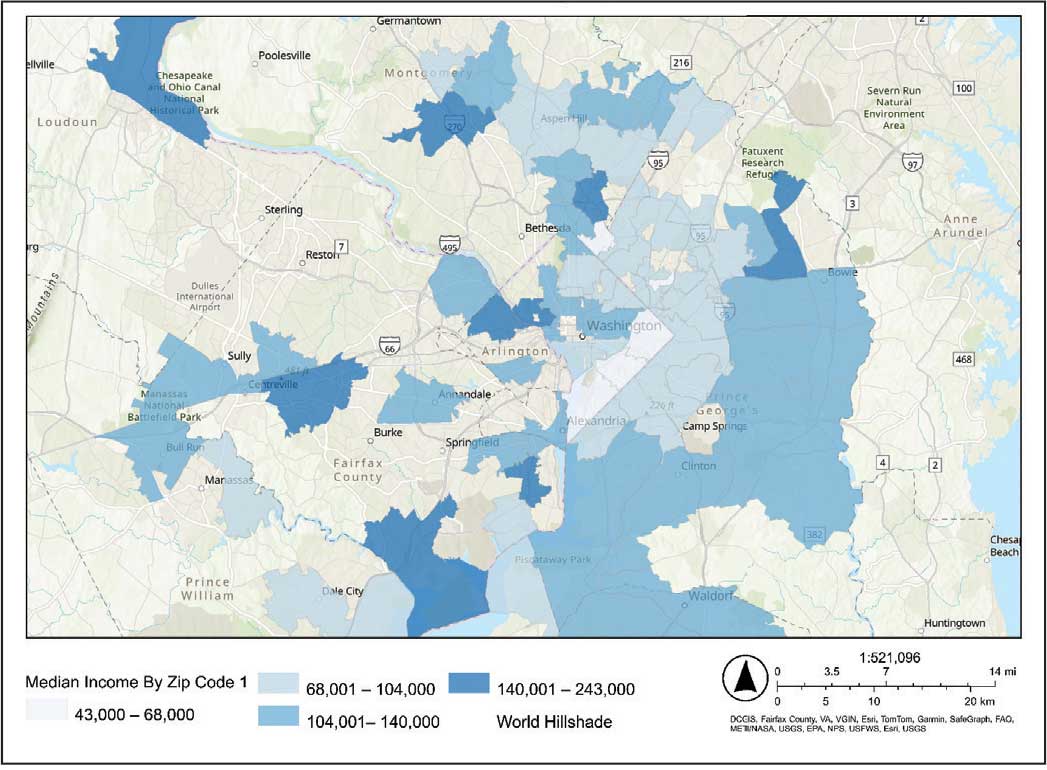

Heat maps were generated to visualize the geospatial distribution of COVID-19 cases and median incomes across zip codes in the greater Washington, DC area. Patient case data and median income, aggregated by zip code, were imported using ArcGIS Online. A zip code boundary layer from Esri (United States Zip Code Boundaries) was used to spatially align the case data. Data were joined by matching zip codes or median incomes in the patient dataset to those in the boundary layer. The resulting polygon layer was styled using the Counts and Amounts (Color) symbology in ArcGIS Online, with case counts or median income determining the intensity of the color gradient.

Results

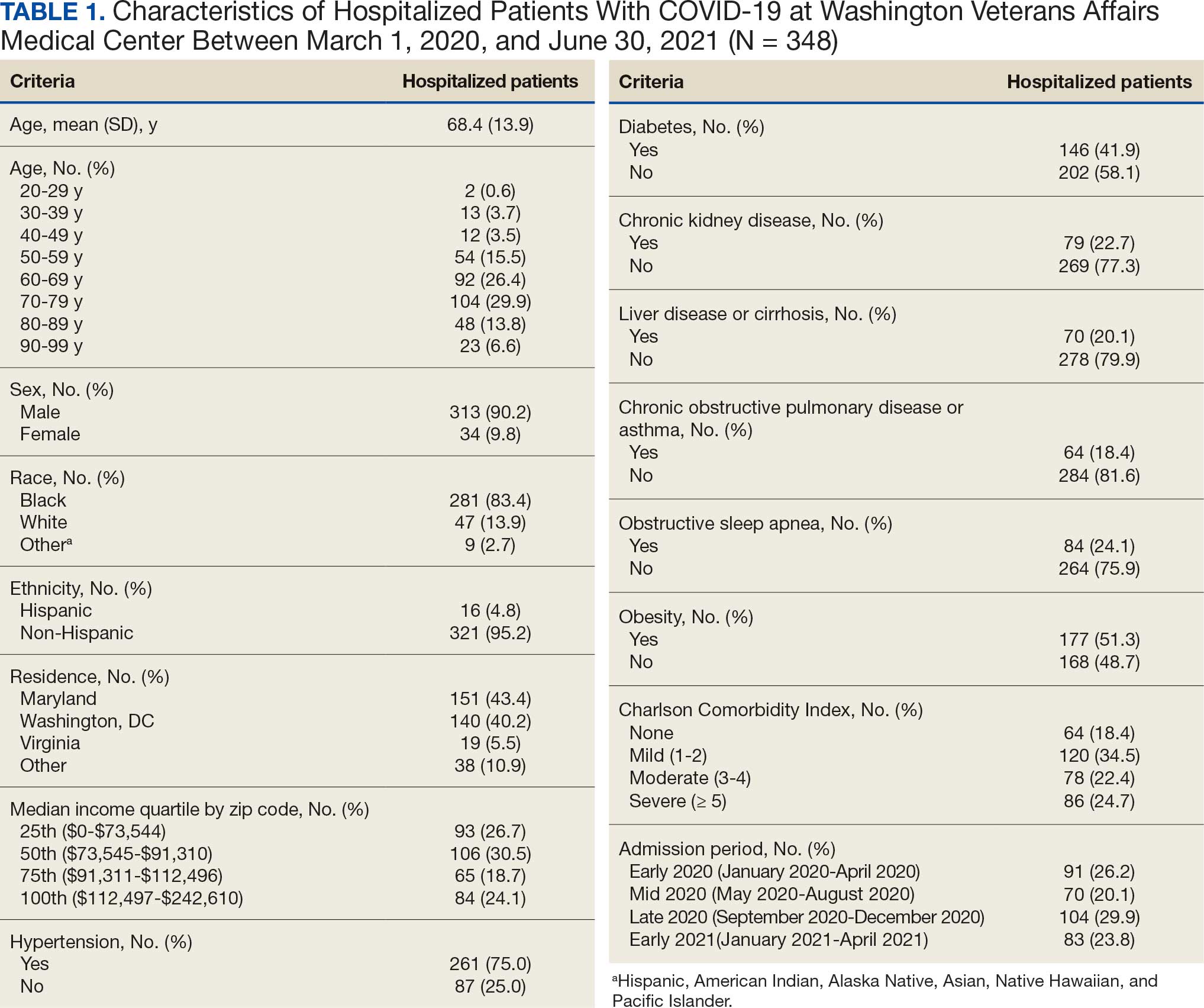

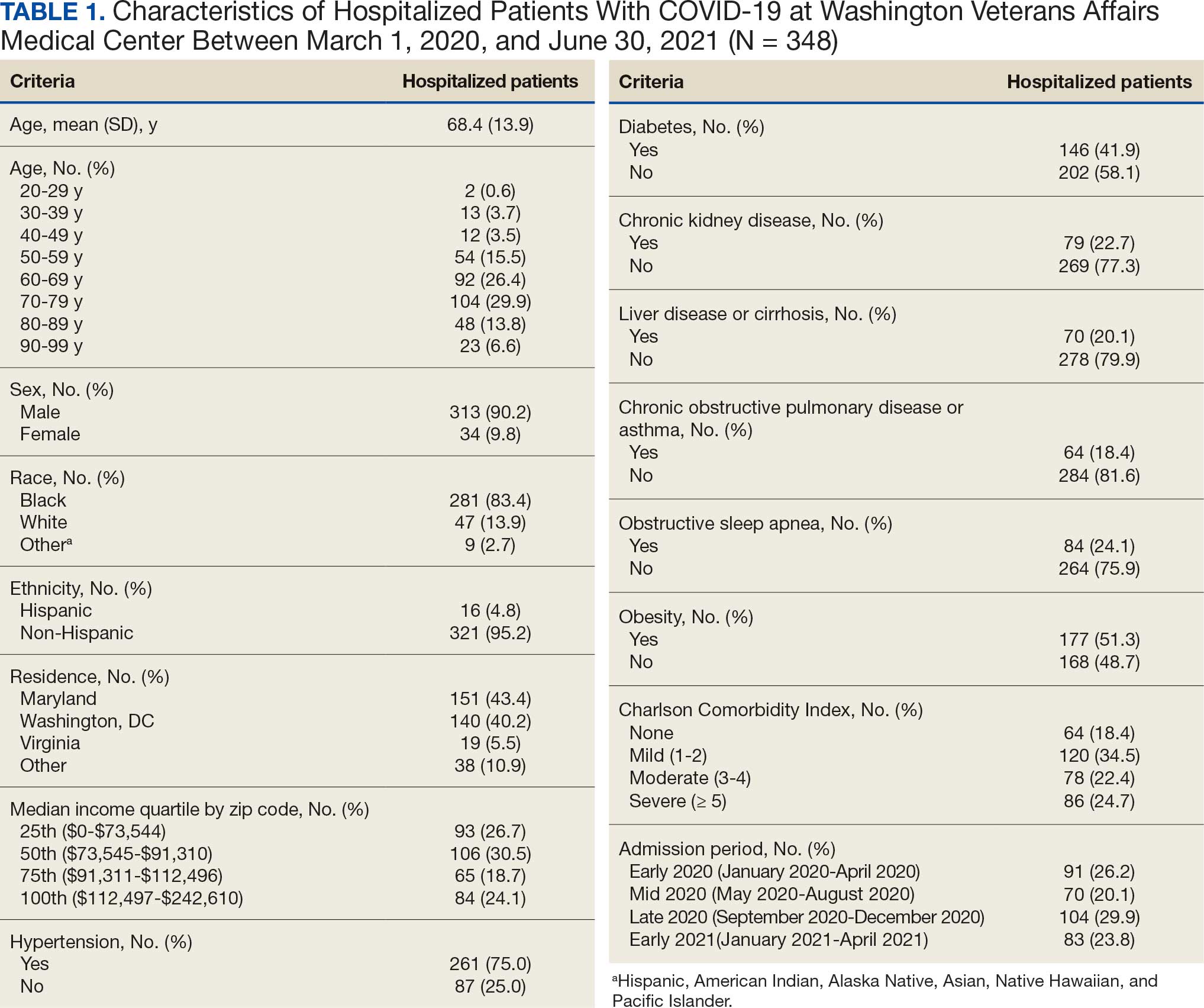

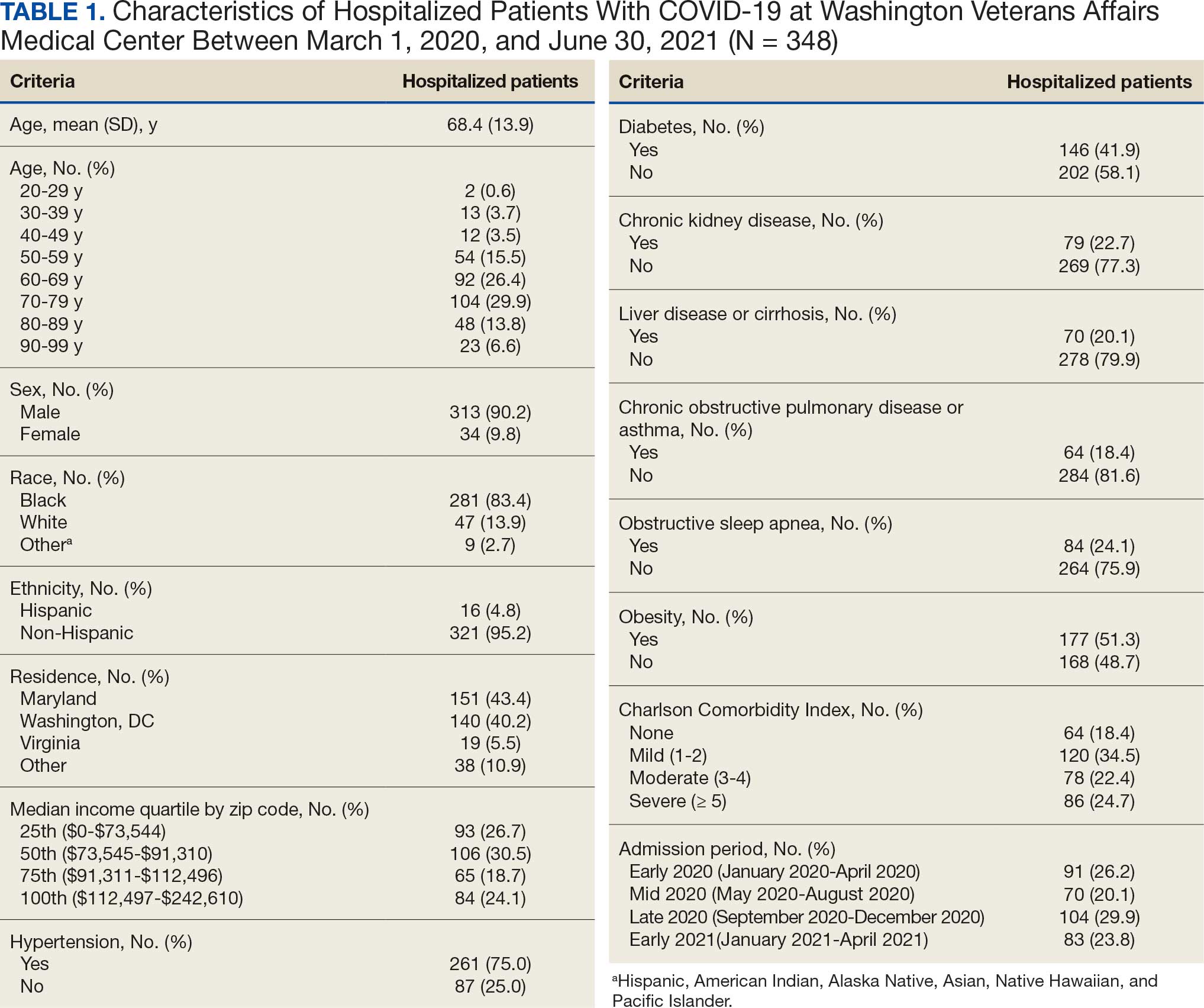

Between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, 348 patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 68.4 (13.9) years, 313 patients (90.2%) were male, 281 patients (83.4%) were Black, 47 patients (13.6%) were White, and 16 patients (4.8%) were Hispanic. One hundred forty patients (40.2%) resided in Washington, DC, 151 (43.4%) in Maryland, and 19 (5.5%) in Virginia. HFO was received by 86 patients (24.7%), 33 (9.5%) required intubation and mechanical ventilation, and 57 (16.4%) died. All intubations and deaths occurred among patients aged > 50 years, with death occurring in 17.8% of patients aged > 50 years.

Demographic characteristics and baseline comorbidities associated with COVID-19 disease severity can be found in eAppendix 2. In unadjusted analyses, age was significantly associated with the risk of HFO, with a mean (SD) age of 72.5 (11.7) years among those requiring HFO and 67.1 (14.4) years among patients without HFO (odds ratio [OR], 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; P = .002). Although age was not associated with the risk of intubation, it was significantly associated with mortality. Patients who died had a mean (SD) age of 76.8 (11.8) years compared with 66.8 (13.7) years among survivors (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09; P < .001).

Compared with patients with no comorbidities, CCI categories of mild, moderate, and severe were associated with increased risk of requiring HFO (eAppendix 3). The adjusted OR (aOR) was highest among patients with severe CCI (aOR, 7.00; 95% CI, 2.42-20.32; P = .0007). In age-adjusted analyses, CCI was not associated with intubation or mortality.

Geospatial Analyses

State of residence, county of residence, and geographic area (including Washington, DC wards, and geographic divisions within counties of residence in Maryland and Virginia) were not associated with the clinical outcomes studied (eAppendix 4). However, zip code-based median income, analyzed as a continuous variable, was associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving HFO (aOR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84-0.99; P = .03). Income was not significantly associated with intubation or mortality.

The majority of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 at WVAMC resided in zip codes in eastern Washington, DC, inclusive of wards 7 and 8, and Prince George’s County, Maryland (Figure 1). These areas also corresponded to the lowest median household income by zip code (Figure 2).

Code

Code

Multivariable Analysis

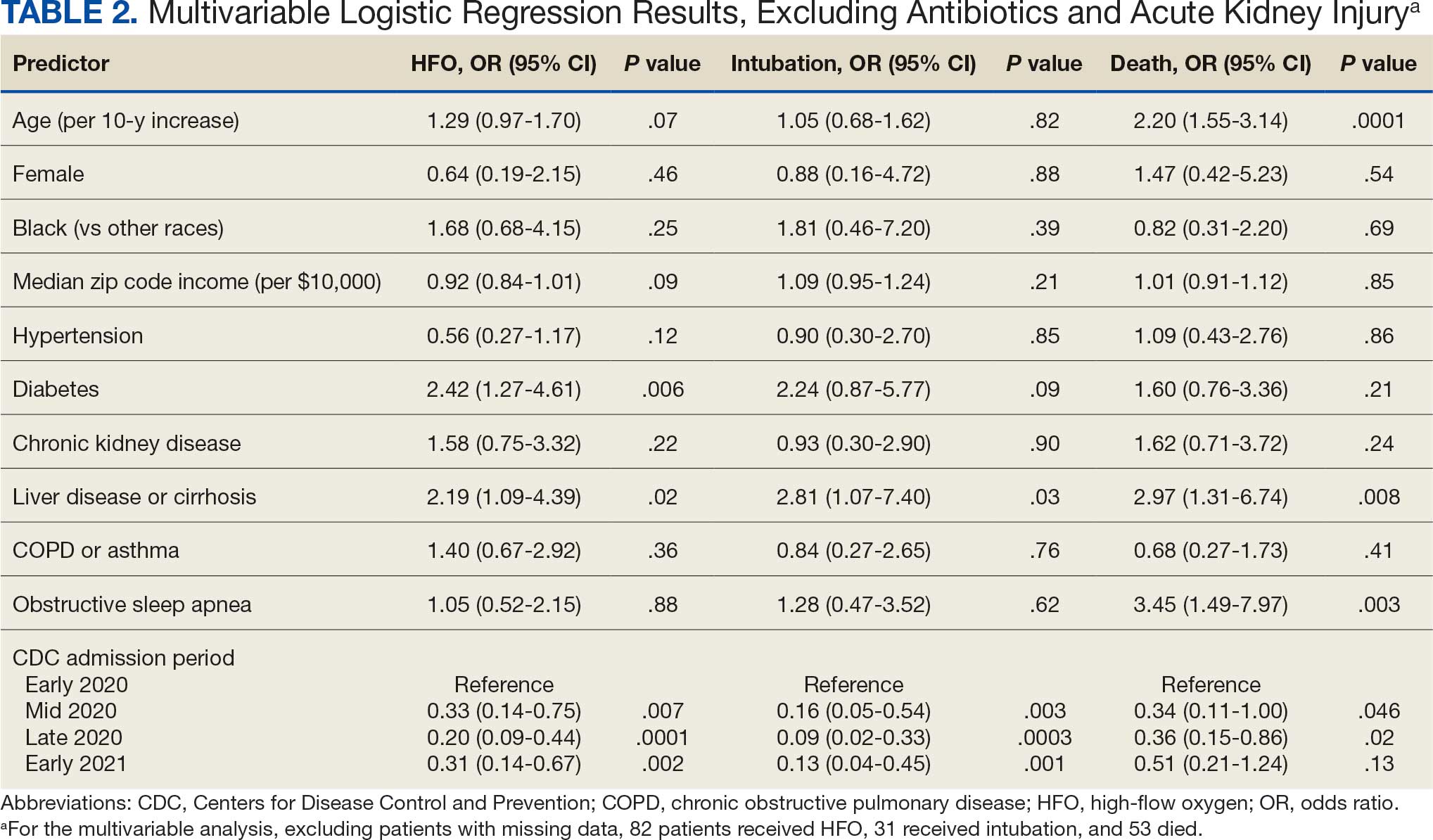

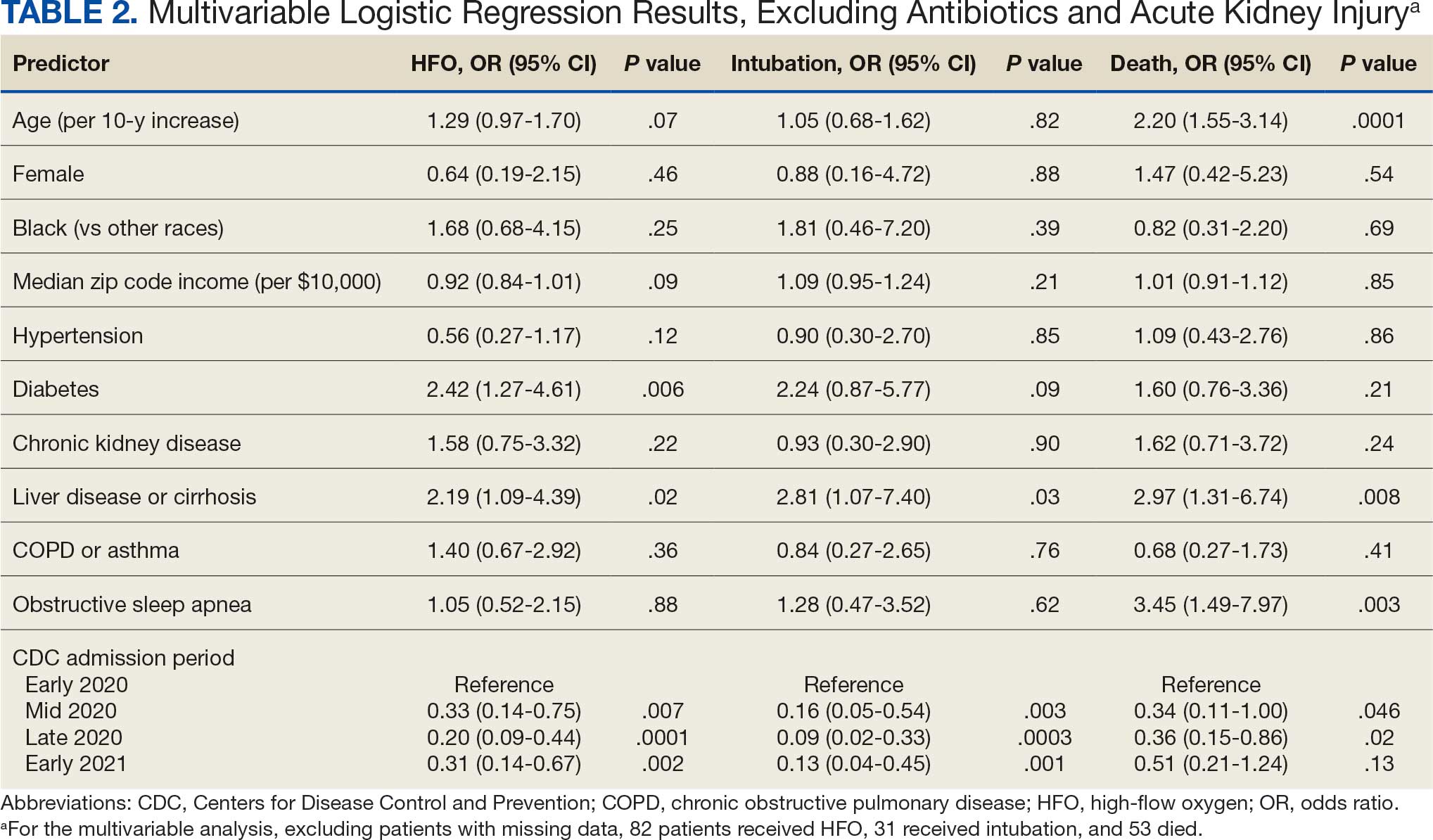

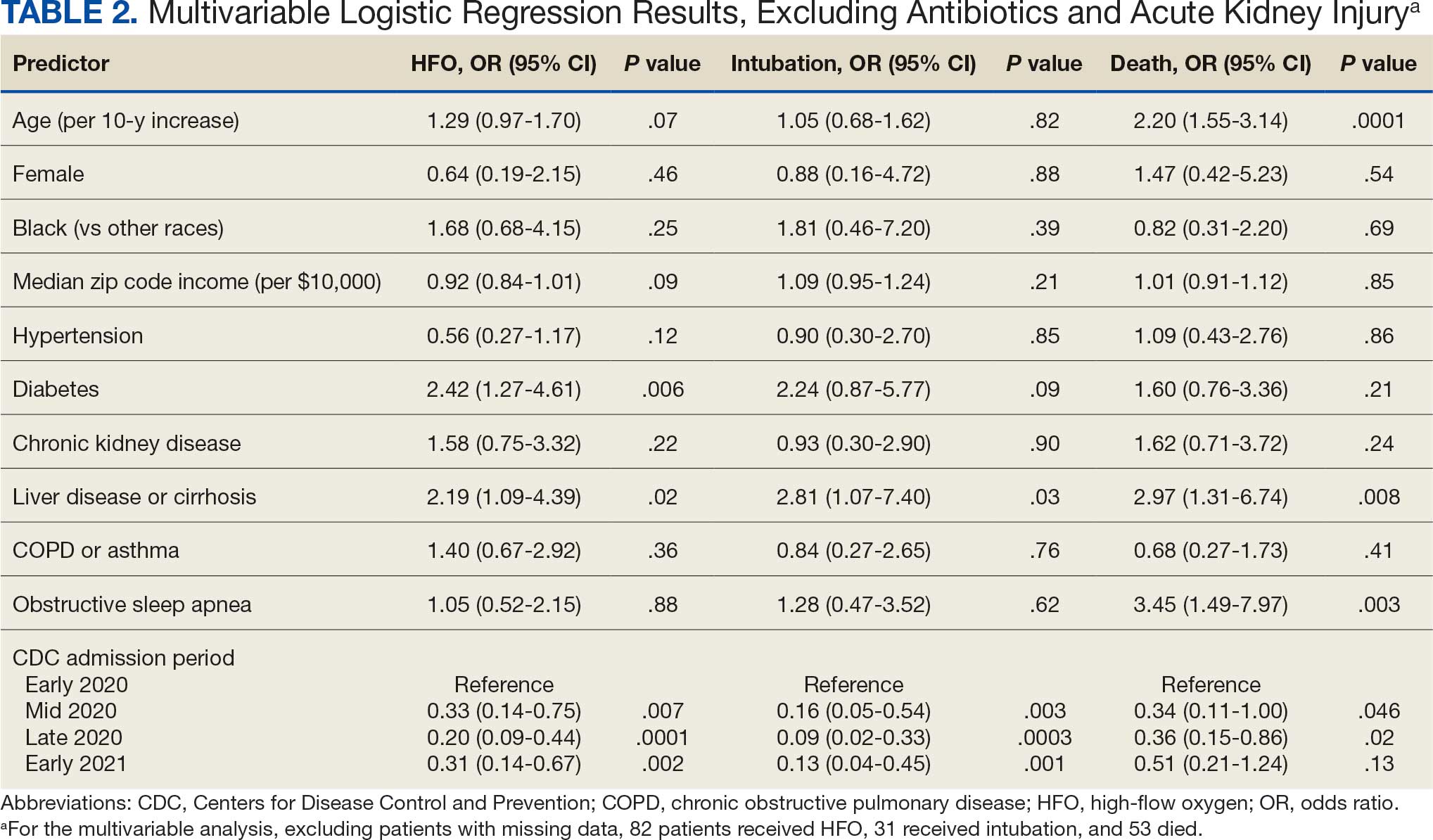

Significant predictors of HFO requirement included comorbid diabetes (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.27-4.61; P = .006) and liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.09-4.39; P = .02) (Table 2). CDC admission period was also associated with HFO need. Patients admitted after early 2020 had lower odds of receiving HFO. Race and median income based on zip code residence were not associated with HFO requirement.

Comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis was a significant predictor of intubation (OR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.07-7.40; P = .03). CDC admission period was associated with intubation with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted after early 2020. Race and median income by zip code were not associated with intubation.

Significant predictors of mortality included age (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.55-3.14; P = .0001), comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.31-6.74; P = .008), and OSA (OR, 3.45; 95% CI, 1.49-7.97; P = .003). CDC admission period was associated with mortality, with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted in mid- and late 2020. Race and median income by zip code residence were not associated with intubation.

Discussion

In this study of COVID-19 disease severity at a large integrated health care system that provides equal access to care, race, ethnicity, and geographic location were not associated with the need for HFO, intubation, or presumed mortality. Median income by zip code residence was associated with reduced HFO use in univariable analyses but not in multivariable models.

These findings support existing literature suggesting that race and ethnicity alone do not explain disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that disparities in health outcomes have been reduced for patients receiving VHA care.6,16-19 However, even within a health care system with assumed equal access, the finding of an association between income and need for HFO in the univariable analysis may reflect a greater likelihood of delays in care due to structural barriers. Multiple studies suggest low SES may be an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease. Individuals with low SES have higher rates of chronic diseases of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and lung disease; thus, they are also at greater risk of serious illness with COVID-19.20-24 Socioeconomic disadvantage may also have limited individuals’ ability to engage in protective behaviors to reduce COVID-19 infection risk, including food stockpiling, social distancing, avoidance of public transportation, and refraining from working in “essential jobs.”21

Beyond SES, place of residence also influences health outcomes. Prior literature supports using zip codes to assess area-based SES status and monitor health disparities.25 The Social Vulnerability Index incorporates SES factors for communities and measures social determinates of health at a zip code level exclusive of race and ethnicity.26 Socially vulnerable communities are known to have higher rates of chronic diseases, COVID-19 mortality, and lower vaccination rates.3 Within a defined geographic area, an individual’s outcome for COVID-19 can be influenced by individual resources such as access to care and median income. Disposable income may mitigate COVID-19 risk by facilitating timely care, reducing occupational exposure, improving housing stability, and supporting health-promoting behaviors.21

Limitations

Due to the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, variants, treatments, and interventions varied throughout the study period and are not included in this analysis. In late December 2020, COVID-19 vaccination was approved with a tiered allocation for at-risk patients and direct health care professionals. Three of the 4 study periods analyzed in this study were prior to vaccine rollout and therefore vaccination history was not assessed. However, we tried to capture the evolving changes in COVID-19 variants, treatments and interventions, and skill in treating the disease through use of CDC-defined time frames. Another limitation is that some studies have shown that use of median income by zip code residence can underestimate mortality.27 Also, shared resources and access to other sources of disposable income can impact the immediate attainment of social needs. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems in Washington, DC assisted vulnerable individuals by providing food, housing, and other resources.28,29 Finally, the modest sample size limits generalizability and power to detect differences for certain variables, including Hispanic ethnicity.

Conclusions

There have been widely described disparities in disease severity and death during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this urban veteran cohort of hospitalized patients, there was no difference in the need for intubation or mortality associated with race. The findings suggest that a lower median income by zip code residence may be associated with greater disease severity at presentation, but do not predict severe outcomes and mortality overall. VHA care, which provides equal access to care, may mitigate the disparities seen in the private sector.

- District of Columbia: All Race & Ethnicity Data. The COVID Tracking Project. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://covidtracking.com/data/state/district-of-columbia/race-ethnicity

- Freese KE, Vega A, Lawrence JJ, et al. Social vulnerability is associated with risk of COVID-19 related mortality in U.S. counties with confirmed cases. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32:245-257. doi:10.1353/hpu.2021.0022

- Saulsberry L, Bhargava A, Zeng S, et al. The social vulnerability metric (SVM) as a new tool for public health. Health Serv Res. 2023;58:873-881. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14102

- Romano SD, Blackstock AJ, Taylor EV, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations, by region - United States, March-December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:560-565. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2

- Kullar R, Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, et al. Racial disparity of coronavirus disease 2019 in African American communities. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:890-893. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa372

- Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic White men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126:1683-1690. doi:10.1002/cncr.32666

- Ohl ME, Richardson Miell K, Beck BF, et al. Mortality among US veterans admitted to community vs Veterans Health Administration hospitals for COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2315902. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15902

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Washington DC Health Care. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.va.gov/washington-dc-health-care/about-us/

- Trottier C, La J, Li LL, et al. Maintaining the utility of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic severity surveillance: evaluation of trends in attributable deaths and development and validation of a measurement tool. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77:1247-1256. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad381

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Updated July 8, 2024. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html#Early-2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Covid-surveillance and data analytics. September 5, 2025. Accessed January 16, 2026. cdc.gov/covid/php/surveillance/index.html12.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

- Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e2

- US Census Bureau. Explore census data. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://data.census.gov/profile?q=Income%20by%20Zip%20code%20tabulation%20area

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale D, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Jackson GL. Examining potential colorectal cancer care disparities in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3579-3584. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4753

- Grubaugh AL, Slagle DM, Long M, Frueh BC, Magruder KM. Racial disparities in trauma exposure, psychiatric symptoms, and service use among female patients in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.001

- Bosworth HB, Parsey KS, Butterfield MI, et al. Racial variation in wanting and obtaining mental health services among women veterans in a primary care clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:231-236.

- Luo J, Rosales M, Wei G, et al. Hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and case-fatality outcomes in US veterans with COVID-19 disease between years 2020-2021. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;70:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.04.003

- Kondo K, Low A, Everson T, et al. Health disparities in veterans: a map of the evidence. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S9-S15. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000756

- Grosicki GJ, Bunsawat K, Jeong S, Robinson AT. Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic disease and COVID-19 outcomes in White, Black/African American, and Latinx populations: Social determinants of health. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;71:4-10. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2022.04.004

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U.S.). Division of Viral Diseases. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups: June 4, 2020. CDC Stacks. June 4, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/88770

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891-1892. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6548

- Magesh S, John D, Li WT, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2134147. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147

- Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:398-417. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12229

- Social Vulnerability Index. Agency for Toxicity and Disease Registry. July 22, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

- Moss JL, Johnson NJ, Yu M, Altekruse SF, Cronin KA. Comparisons of individual- and area-level socioeconomic status as proxies for individual-level measures: evidence from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities study. Popul Health Metr. 2021;19:1. doi:10.1186/s12963-020-00244-x

- DC Department of Human Services. Response to COVID-19. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://dhs.dc.gov/page/responsetocovid19

- Wang PG, Brisbon NM, Hubbell H, et al. Is the Gap Closing? Comparison of sociodemographic cisparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations and outcomes between two temporal waves of admissions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10:593-602. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01249-y

Large epidemiologic studies have shown disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES). Racial and ethnic minorities and individuals of lower SES have experienced disproportionately higher rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death. In Washington, DC, Black individuals (47% of the population) accounted for 51% of COVID-19 cases and 75% of deaths. In comparison, White individuals (41% of the population) accounted for 21% of cases and 11% of deaths.1 Place of residence, such as living in socially vulnerable communities, has also been shown to be associated with higher rates of COVID-19 mortality and lower vaccination rates.2-4 Social and structural inequities, such as limited access to health care services and mistrust of the health care system, may explain some of the observed disparities.5 However, data are limited regarding COVID-19 outcomes for individuals with equal access to care.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system and operates 123 acute care hospitals. Previous research has demonstrated that disparities in outcomes for other diseases are attenuated or erased among veterans receiving VHA care.6,7 Based on literature from the pandemic, markers of health care inequity relating to SES (eg, place of residence, median income) are expected to impact the outcomes of patients acutely hospitalized with COVID-19.4 We hypothesized that the impact on clinical outcomes of infection would be mitigated for veterans receiving VHA care.

This retrospective cohort study included veterans who presented to Washington Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WVAMC) with the goal of determining whether place of residence as a marker of SES, health care access, and median income were predictive of COVID-19 disease severity.

Methods

The WVAMC serves about 125,000 veterans across the metropolitan area, including parts of Maryland and Virginia. It is a high-complexity hospital with 164 acute care beds, 30 psychosocial residential rehabilitation beds, and an adjacent 120-bed community living center providing long-term, hospice, and palliative care.8

The WVAMC developed a dashboard that tracked patients with COVID-19 through on-site testing by admission date, ward, and other key demographics (PowerBi, Corporate Data Warehouse). All patients admitted to WVAMC with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, were included in this retrospective review. Using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the dashboard, we collected demographic information, baseline clinical diagnoses, laboratory results, and clinical interventions for all patients with documented COVID-19 infection as established by laboratory testing methods available at the time of diagnosis. Veterans treated exclusively outside the WVAMC were excluded. Hospitalization was defined as any acute inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before and 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test. Home testing kits were not widely available during the study period. An ICU stay was defined as any inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before or 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test for which the ward location had the specialty of medical or surgical ICU. Death due to COVID-19 was defined as occurring within 42 days (6 weeks) of a positive COVID-19 test.9 This definition assumed that during the peak of the pandemic, COVID-19 was the attributable cause of death, despite the possible contribution of underlying health conditions.

Patients’ admission periods were based on US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) national data and classified as early 2020 (January 2020–April 2020), mid-2020 (May 2020–August 2020), late 2020 (September 2020–December 2020), and early 2021 (January 2021–April 2021).10 We chose to use these time periods as surrogates for the frequent changes in circulating COVID-19 variants, surges in case numbers, therapies and interventions available during the pandemic. The dominant COVID-19 variant during the study period was Alpha (B.1.17). Beta (B.1.351) variants were circulating infrequently, and Delta and Omicron appeared after the study period.11 Treatment strategies evolved rapidly with emerging evidence, including the use of dexamethasone, beginning in June 2020.12 WVAMC followed the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidance on vaccination rollout beginning in December 2020.13

Patients' income was estimated by the median household income of the zip code residence based on US Census Bureau 2021 estimates and was assessed as both a continuous and categorical variable.14 The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was included in models as a continuous variable.15 Variables contributing to the CCI include myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, hemiplegia or paraplegia, ulcer disease, hepatic disease, diabetes (with or without end-organ damage), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), connective tissue disease, leukemia, lymphoma, moderate or severe renal disease, solid tumor (with or without metastases), and HIV/AIDS. The WVAMC Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB #1573071).

Variables

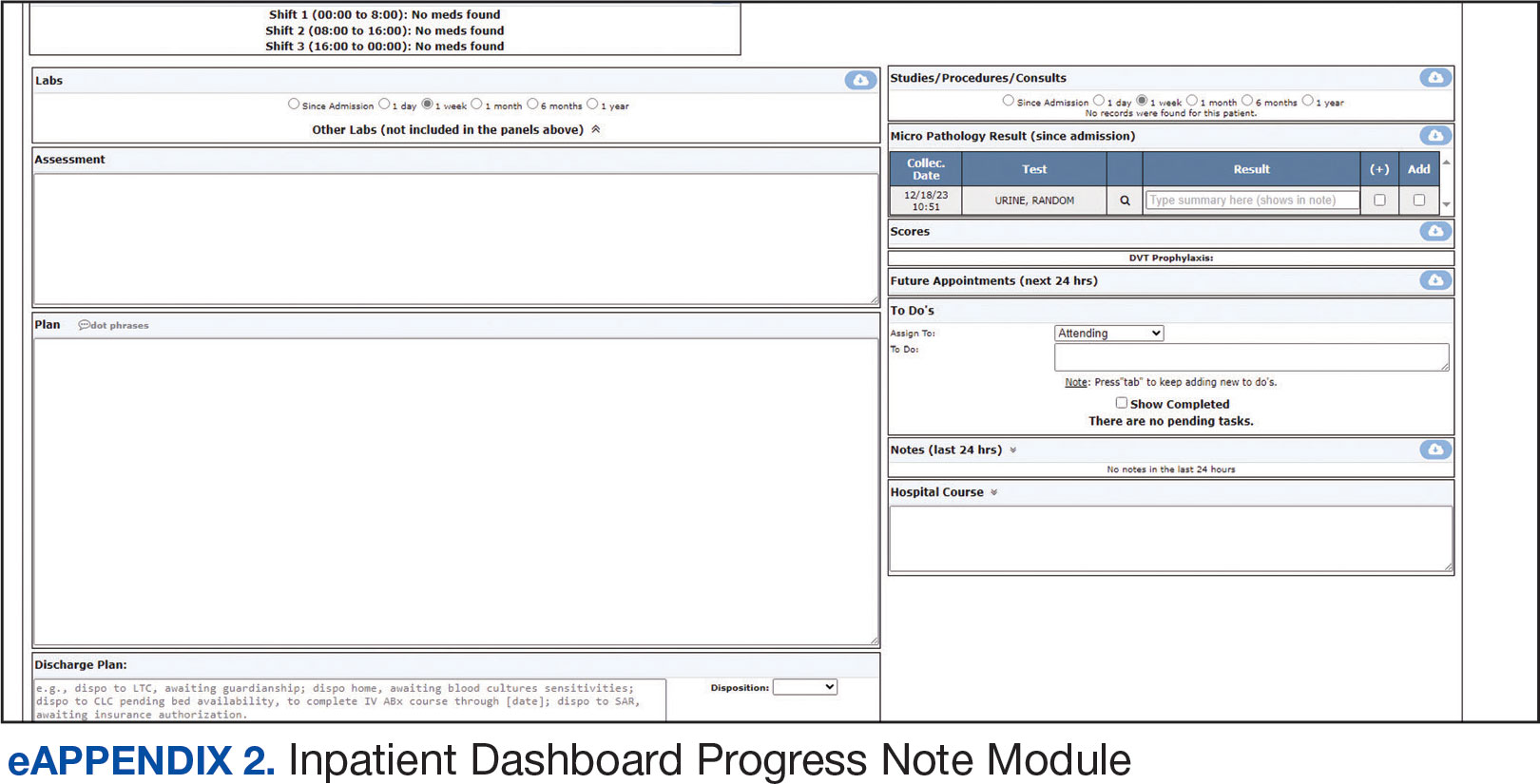

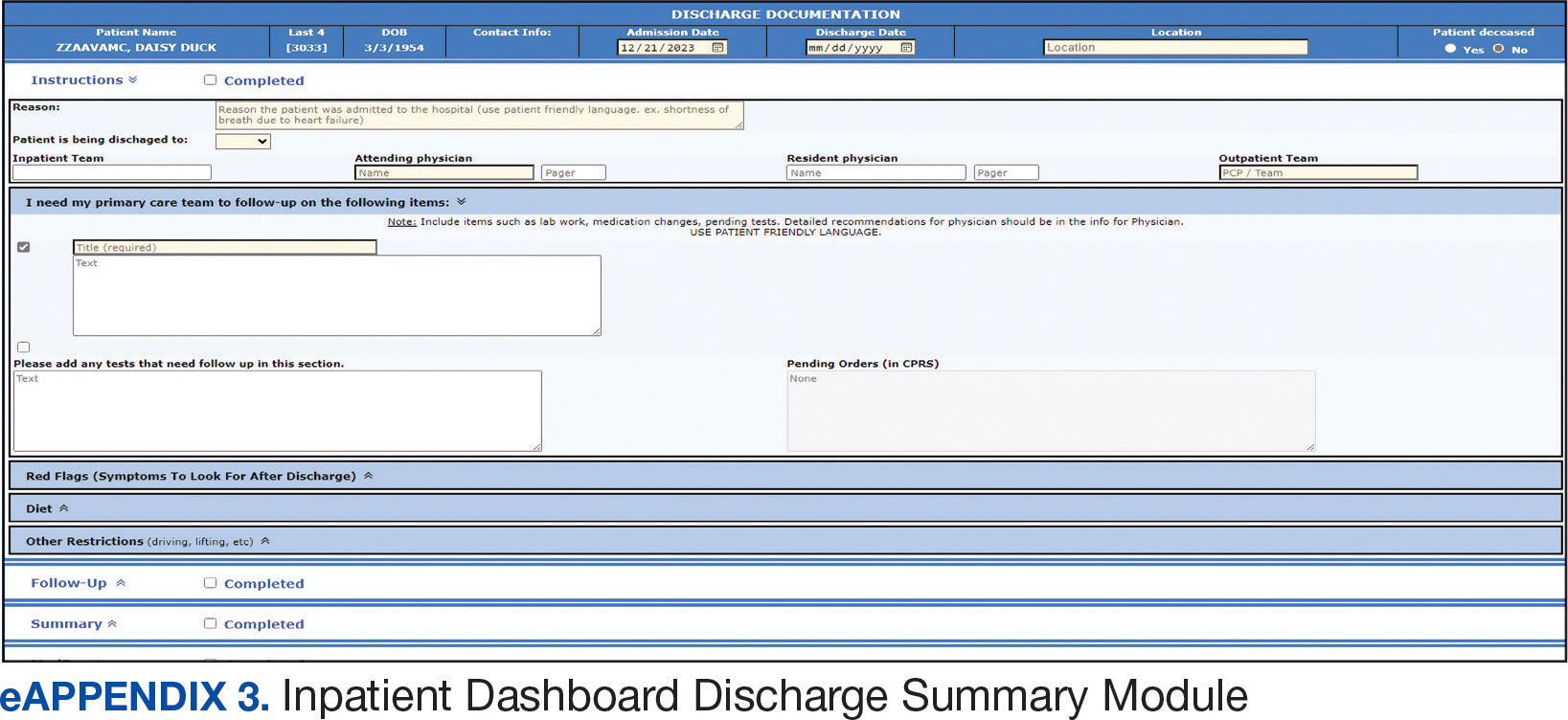

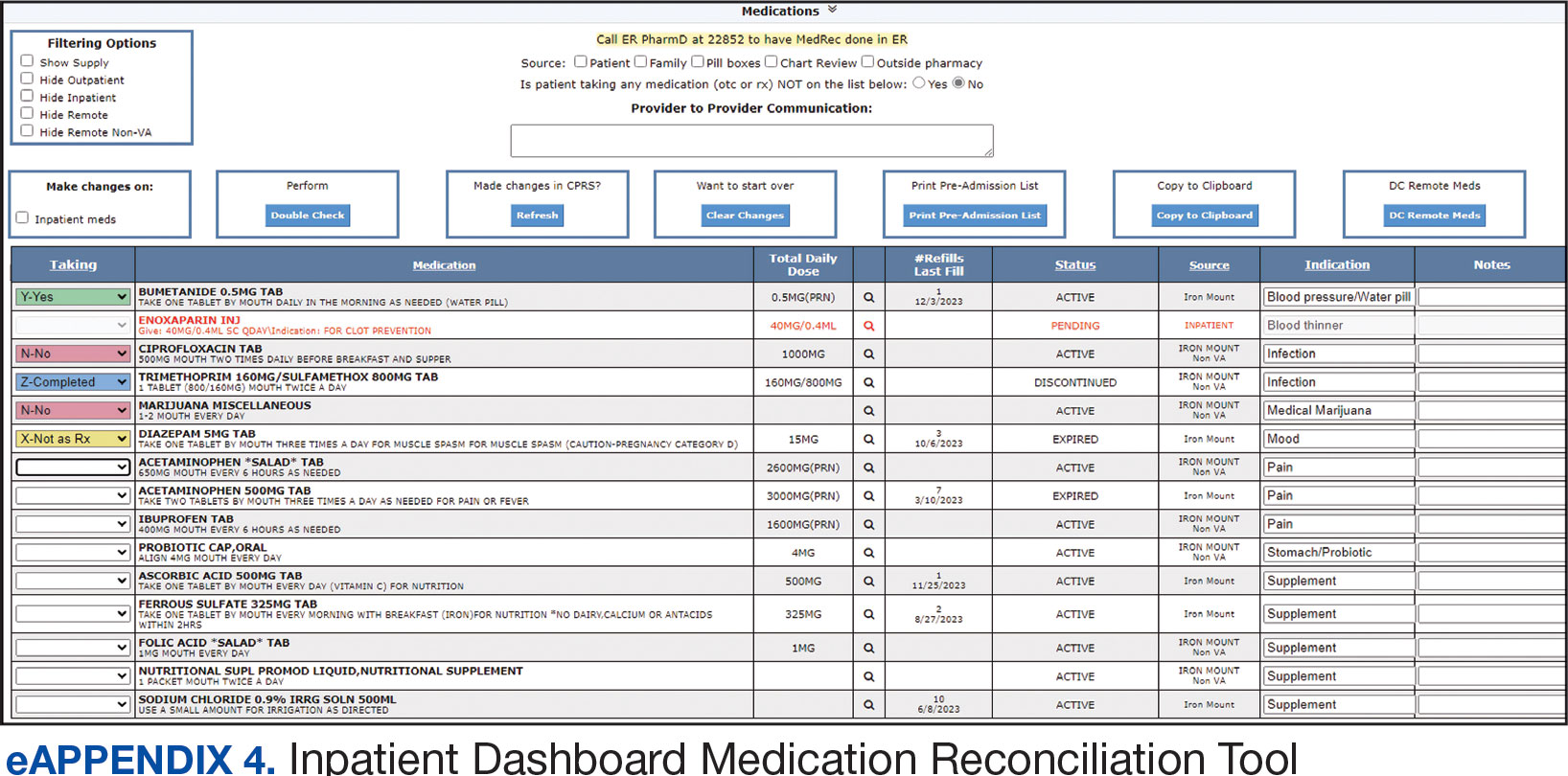

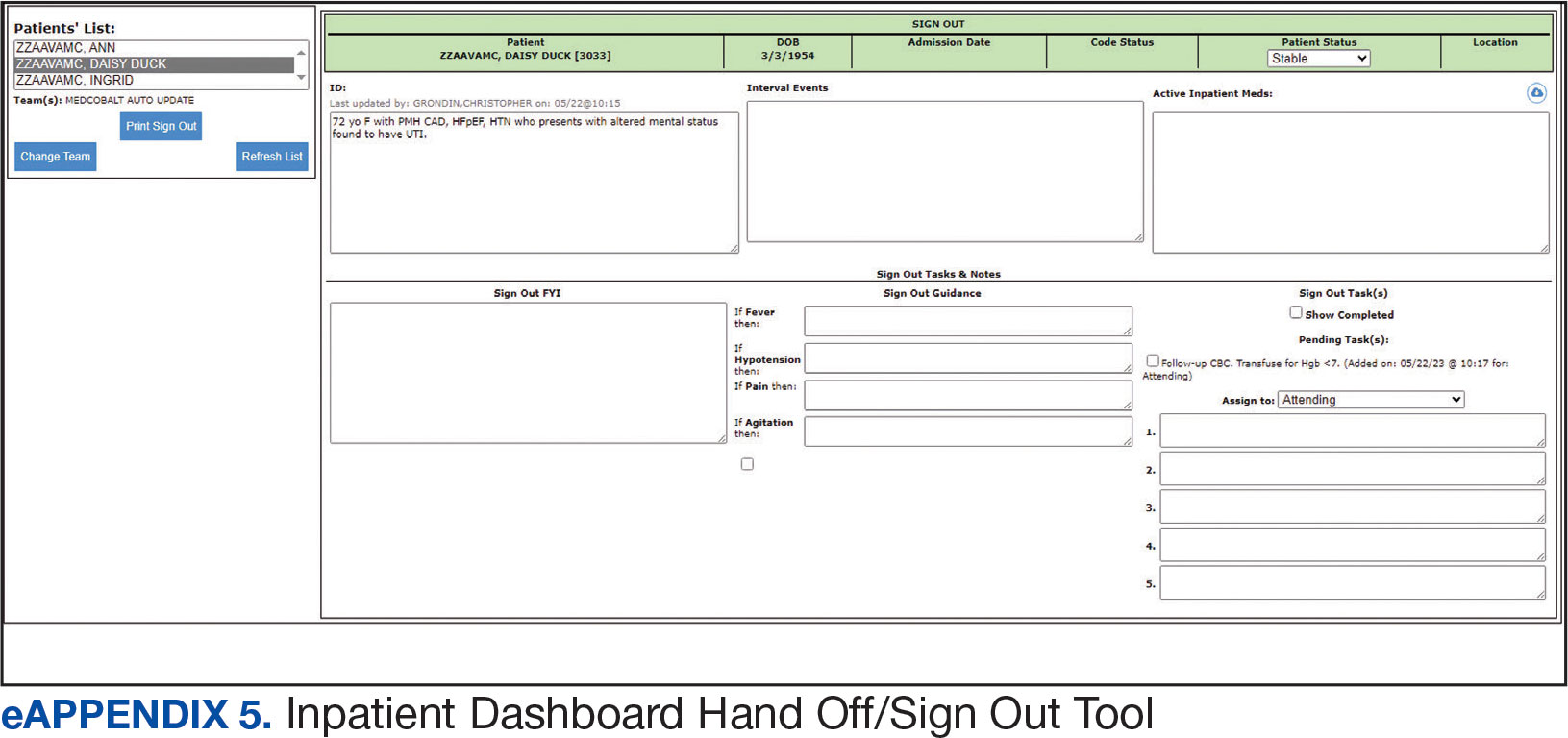

This study assessed 3 primary outcomes as indicators of disease severity during hospitalization: need for high-flow oxygen (HFO), intubation, and presumed mortality at any time during hospitalization. The following variables were collected as potential social determinants or clinical risk-adjustment predictors of disease severity outcomes: age; sex; race and ethnicity; median income for patient’s zip code residence, state, and county; wards within Washington, DC; comorbidities, CCI; tobacco use; and body mass index.15 Although medications at baseline, treatments during hospitalization for COVID-19, and laboratory parameters during hospitalization are shown in eAppendices 1 and 2, they are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Three types of logistic regression models were calculated for predicting the disease severity outcomes: (1) simple unadjusted models; (2) models predicting from single variables plus age (age-adjusted); and (3) multivariable models using all nonredundant potential predictors with adequate sample sizes (multivariable). Variables were considered to have inadequate sample sizes if there was nontrivial missing data or small numbers within categories, (eg, AIDS, connective tissue disease). Potential predictors for the multivariable model included age, sex, race, median income by zip code residence, CCI, CDC admission period, obesity, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), diabetes, COPD or asthma, liver disease, antibiotics, and acute kidney injury.

For the multivariable models, the following modifications were made to avoid unreliable parameter estimation and computation problems (quasi-separation): age and CCI were included as continuous rather than categorical variables. Race was recoded as a 2-category variable (Black vs other [White, Hispanic, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander]), and ethnicity was excluded because of the small number of patients in this group (n = 16). Admission period was included. Predicted probability plots were generated for each outcome with continuous independent predictors (income and CCI), both unadjusted and adjusted for age as a continuous covariate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Heat Maps

Heat maps were generated to visualize the geospatial distribution of COVID-19 cases and median incomes across zip codes in the greater Washington, DC area. Patient case data and median income, aggregated by zip code, were imported using ArcGIS Online. A zip code boundary layer from Esri (United States Zip Code Boundaries) was used to spatially align the case data. Data were joined by matching zip codes or median incomes in the patient dataset to those in the boundary layer. The resulting polygon layer was styled using the Counts and Amounts (Color) symbology in ArcGIS Online, with case counts or median income determining the intensity of the color gradient.

Results

Between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, 348 patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 68.4 (13.9) years, 313 patients (90.2%) were male, 281 patients (83.4%) were Black, 47 patients (13.6%) were White, and 16 patients (4.8%) were Hispanic. One hundred forty patients (40.2%) resided in Washington, DC, 151 (43.4%) in Maryland, and 19 (5.5%) in Virginia. HFO was received by 86 patients (24.7%), 33 (9.5%) required intubation and mechanical ventilation, and 57 (16.4%) died. All intubations and deaths occurred among patients aged > 50 years, with death occurring in 17.8% of patients aged > 50 years.

Demographic characteristics and baseline comorbidities associated with COVID-19 disease severity can be found in eAppendix 2. In unadjusted analyses, age was significantly associated with the risk of HFO, with a mean (SD) age of 72.5 (11.7) years among those requiring HFO and 67.1 (14.4) years among patients without HFO (odds ratio [OR], 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; P = .002). Although age was not associated with the risk of intubation, it was significantly associated with mortality. Patients who died had a mean (SD) age of 76.8 (11.8) years compared with 66.8 (13.7) years among survivors (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09; P < .001).

Compared with patients with no comorbidities, CCI categories of mild, moderate, and severe were associated with increased risk of requiring HFO (eAppendix 3). The adjusted OR (aOR) was highest among patients with severe CCI (aOR, 7.00; 95% CI, 2.42-20.32; P = .0007). In age-adjusted analyses, CCI was not associated with intubation or mortality.

Geospatial Analyses

State of residence, county of residence, and geographic area (including Washington, DC wards, and geographic divisions within counties of residence in Maryland and Virginia) were not associated with the clinical outcomes studied (eAppendix 4). However, zip code-based median income, analyzed as a continuous variable, was associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving HFO (aOR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84-0.99; P = .03). Income was not significantly associated with intubation or mortality.

The majority of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 at WVAMC resided in zip codes in eastern Washington, DC, inclusive of wards 7 and 8, and Prince George’s County, Maryland (Figure 1). These areas also corresponded to the lowest median household income by zip code (Figure 2).

Code

Code

Multivariable Analysis

Significant predictors of HFO requirement included comorbid diabetes (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.27-4.61; P = .006) and liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.09-4.39; P = .02) (Table 2). CDC admission period was also associated with HFO need. Patients admitted after early 2020 had lower odds of receiving HFO. Race and median income based on zip code residence were not associated with HFO requirement.

Comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis was a significant predictor of intubation (OR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.07-7.40; P = .03). CDC admission period was associated with intubation with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted after early 2020. Race and median income by zip code were not associated with intubation.

Significant predictors of mortality included age (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.55-3.14; P = .0001), comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.31-6.74; P = .008), and OSA (OR, 3.45; 95% CI, 1.49-7.97; P = .003). CDC admission period was associated with mortality, with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted in mid- and late 2020. Race and median income by zip code residence were not associated with intubation.

Discussion

In this study of COVID-19 disease severity at a large integrated health care system that provides equal access to care, race, ethnicity, and geographic location were not associated with the need for HFO, intubation, or presumed mortality. Median income by zip code residence was associated with reduced HFO use in univariable analyses but not in multivariable models.

These findings support existing literature suggesting that race and ethnicity alone do not explain disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that disparities in health outcomes have been reduced for patients receiving VHA care.6,16-19 However, even within a health care system with assumed equal access, the finding of an association between income and need for HFO in the univariable analysis may reflect a greater likelihood of delays in care due to structural barriers. Multiple studies suggest low SES may be an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease. Individuals with low SES have higher rates of chronic diseases of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and lung disease; thus, they are also at greater risk of serious illness with COVID-19.20-24 Socioeconomic disadvantage may also have limited individuals’ ability to engage in protective behaviors to reduce COVID-19 infection risk, including food stockpiling, social distancing, avoidance of public transportation, and refraining from working in “essential jobs.”21

Beyond SES, place of residence also influences health outcomes. Prior literature supports using zip codes to assess area-based SES status and monitor health disparities.25 The Social Vulnerability Index incorporates SES factors for communities and measures social determinates of health at a zip code level exclusive of race and ethnicity.26 Socially vulnerable communities are known to have higher rates of chronic diseases, COVID-19 mortality, and lower vaccination rates.3 Within a defined geographic area, an individual’s outcome for COVID-19 can be influenced by individual resources such as access to care and median income. Disposable income may mitigate COVID-19 risk by facilitating timely care, reducing occupational exposure, improving housing stability, and supporting health-promoting behaviors.21

Limitations

Due to the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, variants, treatments, and interventions varied throughout the study period and are not included in this analysis. In late December 2020, COVID-19 vaccination was approved with a tiered allocation for at-risk patients and direct health care professionals. Three of the 4 study periods analyzed in this study were prior to vaccine rollout and therefore vaccination history was not assessed. However, we tried to capture the evolving changes in COVID-19 variants, treatments and interventions, and skill in treating the disease through use of CDC-defined time frames. Another limitation is that some studies have shown that use of median income by zip code residence can underestimate mortality.27 Also, shared resources and access to other sources of disposable income can impact the immediate attainment of social needs. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems in Washington, DC assisted vulnerable individuals by providing food, housing, and other resources.28,29 Finally, the modest sample size limits generalizability and power to detect differences for certain variables, including Hispanic ethnicity.

Conclusions

There have been widely described disparities in disease severity and death during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this urban veteran cohort of hospitalized patients, there was no difference in the need for intubation or mortality associated with race. The findings suggest that a lower median income by zip code residence may be associated with greater disease severity at presentation, but do not predict severe outcomes and mortality overall. VHA care, which provides equal access to care, may mitigate the disparities seen in the private sector.

Large epidemiologic studies have shown disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES). Racial and ethnic minorities and individuals of lower SES have experienced disproportionately higher rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death. In Washington, DC, Black individuals (47% of the population) accounted for 51% of COVID-19 cases and 75% of deaths. In comparison, White individuals (41% of the population) accounted for 21% of cases and 11% of deaths.1 Place of residence, such as living in socially vulnerable communities, has also been shown to be associated with higher rates of COVID-19 mortality and lower vaccination rates.2-4 Social and structural inequities, such as limited access to health care services and mistrust of the health care system, may explain some of the observed disparities.5 However, data are limited regarding COVID-19 outcomes for individuals with equal access to care.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated US health care system and operates 123 acute care hospitals. Previous research has demonstrated that disparities in outcomes for other diseases are attenuated or erased among veterans receiving VHA care.6,7 Based on literature from the pandemic, markers of health care inequity relating to SES (eg, place of residence, median income) are expected to impact the outcomes of patients acutely hospitalized with COVID-19.4 We hypothesized that the impact on clinical outcomes of infection would be mitigated for veterans receiving VHA care.

This retrospective cohort study included veterans who presented to Washington Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WVAMC) with the goal of determining whether place of residence as a marker of SES, health care access, and median income were predictive of COVID-19 disease severity.

Methods

The WVAMC serves about 125,000 veterans across the metropolitan area, including parts of Maryland and Virginia. It is a high-complexity hospital with 164 acute care beds, 30 psychosocial residential rehabilitation beds, and an adjacent 120-bed community living center providing long-term, hospice, and palliative care.8

The WVAMC developed a dashboard that tracked patients with COVID-19 through on-site testing by admission date, ward, and other key demographics (PowerBi, Corporate Data Warehouse). All patients admitted to WVAMC with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, were included in this retrospective review. Using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the dashboard, we collected demographic information, baseline clinical diagnoses, laboratory results, and clinical interventions for all patients with documented COVID-19 infection as established by laboratory testing methods available at the time of diagnosis. Veterans treated exclusively outside the WVAMC were excluded. Hospitalization was defined as any acute inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before and 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test. Home testing kits were not widely available during the study period. An ICU stay was defined as any inpatient admission or transfer recorded within 5 days before or 30 days after the laboratory collection of a positive COVID-19 test for which the ward location had the specialty of medical or surgical ICU. Death due to COVID-19 was defined as occurring within 42 days (6 weeks) of a positive COVID-19 test.9 This definition assumed that during the peak of the pandemic, COVID-19 was the attributable cause of death, despite the possible contribution of underlying health conditions.

Patients’ admission periods were based on US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) national data and classified as early 2020 (January 2020–April 2020), mid-2020 (May 2020–August 2020), late 2020 (September 2020–December 2020), and early 2021 (January 2021–April 2021).10 We chose to use these time periods as surrogates for the frequent changes in circulating COVID-19 variants, surges in case numbers, therapies and interventions available during the pandemic. The dominant COVID-19 variant during the study period was Alpha (B.1.17). Beta (B.1.351) variants were circulating infrequently, and Delta and Omicron appeared after the study period.11 Treatment strategies evolved rapidly with emerging evidence, including the use of dexamethasone, beginning in June 2020.12 WVAMC followed the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidance on vaccination rollout beginning in December 2020.13

Patients' income was estimated by the median household income of the zip code residence based on US Census Bureau 2021 estimates and was assessed as both a continuous and categorical variable.14 The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was included in models as a continuous variable.15 Variables contributing to the CCI include myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, hemiplegia or paraplegia, ulcer disease, hepatic disease, diabetes (with or without end-organ damage), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), connective tissue disease, leukemia, lymphoma, moderate or severe renal disease, solid tumor (with or without metastases), and HIV/AIDS. The WVAMC Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB #1573071).

Variables

This study assessed 3 primary outcomes as indicators of disease severity during hospitalization: need for high-flow oxygen (HFO), intubation, and presumed mortality at any time during hospitalization. The following variables were collected as potential social determinants or clinical risk-adjustment predictors of disease severity outcomes: age; sex; race and ethnicity; median income for patient’s zip code residence, state, and county; wards within Washington, DC; comorbidities, CCI; tobacco use; and body mass index.15 Although medications at baseline, treatments during hospitalization for COVID-19, and laboratory parameters during hospitalization are shown in eAppendices 1 and 2, they are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Three types of logistic regression models were calculated for predicting the disease severity outcomes: (1) simple unadjusted models; (2) models predicting from single variables plus age (age-adjusted); and (3) multivariable models using all nonredundant potential predictors with adequate sample sizes (multivariable). Variables were considered to have inadequate sample sizes if there was nontrivial missing data or small numbers within categories, (eg, AIDS, connective tissue disease). Potential predictors for the multivariable model included age, sex, race, median income by zip code residence, CCI, CDC admission period, obesity, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), diabetes, COPD or asthma, liver disease, antibiotics, and acute kidney injury.

For the multivariable models, the following modifications were made to avoid unreliable parameter estimation and computation problems (quasi-separation): age and CCI were included as continuous rather than categorical variables. Race was recoded as a 2-category variable (Black vs other [White, Hispanic, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander]), and ethnicity was excluded because of the small number of patients in this group (n = 16). Admission period was included. Predicted probability plots were generated for each outcome with continuous independent predictors (income and CCI), both unadjusted and adjusted for age as a continuous covariate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Heat Maps

Heat maps were generated to visualize the geospatial distribution of COVID-19 cases and median incomes across zip codes in the greater Washington, DC area. Patient case data and median income, aggregated by zip code, were imported using ArcGIS Online. A zip code boundary layer from Esri (United States Zip Code Boundaries) was used to spatially align the case data. Data were joined by matching zip codes or median incomes in the patient dataset to those in the boundary layer. The resulting polygon layer was styled using the Counts and Amounts (Color) symbology in ArcGIS Online, with case counts or median income determining the intensity of the color gradient.

Results

Between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, 348 patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 68.4 (13.9) years, 313 patients (90.2%) were male, 281 patients (83.4%) were Black, 47 patients (13.6%) were White, and 16 patients (4.8%) were Hispanic. One hundred forty patients (40.2%) resided in Washington, DC, 151 (43.4%) in Maryland, and 19 (5.5%) in Virginia. HFO was received by 86 patients (24.7%), 33 (9.5%) required intubation and mechanical ventilation, and 57 (16.4%) died. All intubations and deaths occurred among patients aged > 50 years, with death occurring in 17.8% of patients aged > 50 years.

Demographic characteristics and baseline comorbidities associated with COVID-19 disease severity can be found in eAppendix 2. In unadjusted analyses, age was significantly associated with the risk of HFO, with a mean (SD) age of 72.5 (11.7) years among those requiring HFO and 67.1 (14.4) years among patients without HFO (odds ratio [OR], 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; P = .002). Although age was not associated with the risk of intubation, it was significantly associated with mortality. Patients who died had a mean (SD) age of 76.8 (11.8) years compared with 66.8 (13.7) years among survivors (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09; P < .001).

Compared with patients with no comorbidities, CCI categories of mild, moderate, and severe were associated with increased risk of requiring HFO (eAppendix 3). The adjusted OR (aOR) was highest among patients with severe CCI (aOR, 7.00; 95% CI, 2.42-20.32; P = .0007). In age-adjusted analyses, CCI was not associated with intubation or mortality.

Geospatial Analyses

State of residence, county of residence, and geographic area (including Washington, DC wards, and geographic divisions within counties of residence in Maryland and Virginia) were not associated with the clinical outcomes studied (eAppendix 4). However, zip code-based median income, analyzed as a continuous variable, was associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving HFO (aOR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84-0.99; P = .03). Income was not significantly associated with intubation or mortality.

The majority of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 at WVAMC resided in zip codes in eastern Washington, DC, inclusive of wards 7 and 8, and Prince George’s County, Maryland (Figure 1). These areas also corresponded to the lowest median household income by zip code (Figure 2).

Code

Code

Multivariable Analysis

Significant predictors of HFO requirement included comorbid diabetes (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.27-4.61; P = .006) and liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.09-4.39; P = .02) (Table 2). CDC admission period was also associated with HFO need. Patients admitted after early 2020 had lower odds of receiving HFO. Race and median income based on zip code residence were not associated with HFO requirement.

Comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis was a significant predictor of intubation (OR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.07-7.40; P = .03). CDC admission period was associated with intubation with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted after early 2020. Race and median income by zip code were not associated with intubation.

Significant predictors of mortality included age (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.55-3.14; P = .0001), comorbid liver disease or cirrhosis (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.31-6.74; P = .008), and OSA (OR, 3.45; 95% CI, 1.49-7.97; P = .003). CDC admission period was associated with mortality, with lower odds of intubation for patients admitted in mid- and late 2020. Race and median income by zip code residence were not associated with intubation.

Discussion

In this study of COVID-19 disease severity at a large integrated health care system that provides equal access to care, race, ethnicity, and geographic location were not associated with the need for HFO, intubation, or presumed mortality. Median income by zip code residence was associated with reduced HFO use in univariable analyses but not in multivariable models.

These findings support existing literature suggesting that race and ethnicity alone do not explain disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that disparities in health outcomes have been reduced for patients receiving VHA care.6,16-19 However, even within a health care system with assumed equal access, the finding of an association between income and need for HFO in the univariable analysis may reflect a greater likelihood of delays in care due to structural barriers. Multiple studies suggest low SES may be an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease. Individuals with low SES have higher rates of chronic diseases of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and lung disease; thus, they are also at greater risk of serious illness with COVID-19.20-24 Socioeconomic disadvantage may also have limited individuals’ ability to engage in protective behaviors to reduce COVID-19 infection risk, including food stockpiling, social distancing, avoidance of public transportation, and refraining from working in “essential jobs.”21

Beyond SES, place of residence also influences health outcomes. Prior literature supports using zip codes to assess area-based SES status and monitor health disparities.25 The Social Vulnerability Index incorporates SES factors for communities and measures social determinates of health at a zip code level exclusive of race and ethnicity.26 Socially vulnerable communities are known to have higher rates of chronic diseases, COVID-19 mortality, and lower vaccination rates.3 Within a defined geographic area, an individual’s outcome for COVID-19 can be influenced by individual resources such as access to care and median income. Disposable income may mitigate COVID-19 risk by facilitating timely care, reducing occupational exposure, improving housing stability, and supporting health-promoting behaviors.21

Limitations

Due to the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, variants, treatments, and interventions varied throughout the study period and are not included in this analysis. In late December 2020, COVID-19 vaccination was approved with a tiered allocation for at-risk patients and direct health care professionals. Three of the 4 study periods analyzed in this study were prior to vaccine rollout and therefore vaccination history was not assessed. However, we tried to capture the evolving changes in COVID-19 variants, treatments and interventions, and skill in treating the disease through use of CDC-defined time frames. Another limitation is that some studies have shown that use of median income by zip code residence can underestimate mortality.27 Also, shared resources and access to other sources of disposable income can impact the immediate attainment of social needs. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems in Washington, DC assisted vulnerable individuals by providing food, housing, and other resources.28,29 Finally, the modest sample size limits generalizability and power to detect differences for certain variables, including Hispanic ethnicity.

Conclusions

There have been widely described disparities in disease severity and death during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this urban veteran cohort of hospitalized patients, there was no difference in the need for intubation or mortality associated with race. The findings suggest that a lower median income by zip code residence may be associated with greater disease severity at presentation, but do not predict severe outcomes and mortality overall. VHA care, which provides equal access to care, may mitigate the disparities seen in the private sector.

- District of Columbia: All Race & Ethnicity Data. The COVID Tracking Project. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://covidtracking.com/data/state/district-of-columbia/race-ethnicity

- Freese KE, Vega A, Lawrence JJ, et al. Social vulnerability is associated with risk of COVID-19 related mortality in U.S. counties with confirmed cases. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32:245-257. doi:10.1353/hpu.2021.0022

- Saulsberry L, Bhargava A, Zeng S, et al. The social vulnerability metric (SVM) as a new tool for public health. Health Serv Res. 2023;58:873-881. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14102

- Romano SD, Blackstock AJ, Taylor EV, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations, by region - United States, March-December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:560-565. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2

- Kullar R, Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, et al. Racial disparity of coronavirus disease 2019 in African American communities. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:890-893. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa372

- Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic White men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126:1683-1690. doi:10.1002/cncr.32666

- Ohl ME, Richardson Miell K, Beck BF, et al. Mortality among US veterans admitted to community vs Veterans Health Administration hospitals for COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2315902. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15902

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Washington DC Health Care. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.va.gov/washington-dc-health-care/about-us/

- Trottier C, La J, Li LL, et al. Maintaining the utility of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic severity surveillance: evaluation of trends in attributable deaths and development and validation of a measurement tool. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77:1247-1256. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad381

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Updated July 8, 2024. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html#Early-2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Covid-surveillance and data analytics. September 5, 2025. Accessed January 16, 2026. cdc.gov/covid/php/surveillance/index.html12.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

- Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e2

- US Census Bureau. Explore census data. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://data.census.gov/profile?q=Income%20by%20Zip%20code%20tabulation%20area

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale D, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Jackson GL. Examining potential colorectal cancer care disparities in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3579-3584. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4753

- Grubaugh AL, Slagle DM, Long M, Frueh BC, Magruder KM. Racial disparities in trauma exposure, psychiatric symptoms, and service use among female patients in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.001

- Bosworth HB, Parsey KS, Butterfield MI, et al. Racial variation in wanting and obtaining mental health services among women veterans in a primary care clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:231-236.

- Luo J, Rosales M, Wei G, et al. Hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and case-fatality outcomes in US veterans with COVID-19 disease between years 2020-2021. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;70:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.04.003

- Kondo K, Low A, Everson T, et al. Health disparities in veterans: a map of the evidence. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S9-S15. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000756

- Grosicki GJ, Bunsawat K, Jeong S, Robinson AT. Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic disease and COVID-19 outcomes in White, Black/African American, and Latinx populations: Social determinants of health. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;71:4-10. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2022.04.004

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U.S.). Division of Viral Diseases. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups: June 4, 2020. CDC Stacks. June 4, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/88770

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891-1892. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6548

- Magesh S, John D, Li WT, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2134147. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147

- Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:398-417. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12229

- Social Vulnerability Index. Agency for Toxicity and Disease Registry. July 22, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

- Moss JL, Johnson NJ, Yu M, Altekruse SF, Cronin KA. Comparisons of individual- and area-level socioeconomic status as proxies for individual-level measures: evidence from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities study. Popul Health Metr. 2021;19:1. doi:10.1186/s12963-020-00244-x

- DC Department of Human Services. Response to COVID-19. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://dhs.dc.gov/page/responsetocovid19

- Wang PG, Brisbon NM, Hubbell H, et al. Is the Gap Closing? Comparison of sociodemographic cisparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations and outcomes between two temporal waves of admissions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10:593-602. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01249-y

- District of Columbia: All Race & Ethnicity Data. The COVID Tracking Project. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://covidtracking.com/data/state/district-of-columbia/race-ethnicity

- Freese KE, Vega A, Lawrence JJ, et al. Social vulnerability is associated with risk of COVID-19 related mortality in U.S. counties with confirmed cases. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32:245-257. doi:10.1353/hpu.2021.0022

- Saulsberry L, Bhargava A, Zeng S, et al. The social vulnerability metric (SVM) as a new tool for public health. Health Serv Res. 2023;58:873-881. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14102

- Romano SD, Blackstock AJ, Taylor EV, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations, by region - United States, March-December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:560-565. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2

- Kullar R, Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, et al. Racial disparity of coronavirus disease 2019 in African American communities. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:890-893. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa372

- Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic White men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126:1683-1690. doi:10.1002/cncr.32666

- Ohl ME, Richardson Miell K, Beck BF, et al. Mortality among US veterans admitted to community vs Veterans Health Administration hospitals for COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2315902. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15902

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Washington DC Health Care. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.va.gov/washington-dc-health-care/about-us/

- Trottier C, La J, Li LL, et al. Maintaining the utility of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic severity surveillance: evaluation of trends in attributable deaths and development and validation of a measurement tool. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77:1247-1256. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad381

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Updated July 8, 2024. Accessed January 16, 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html#Early-2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Covid-surveillance and data analytics. September 5, 2025. Accessed January 16, 2026. cdc.gov/covid/php/surveillance/index.html12.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

- Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e2

- US Census Bureau. Explore census data. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://data.census.gov/profile?q=Income%20by%20Zip%20code%20tabulation%20area

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale D, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Jackson GL. Examining potential colorectal cancer care disparities in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3579-3584. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4753

- Grubaugh AL, Slagle DM, Long M, Frueh BC, Magruder KM. Racial disparities in trauma exposure, psychiatric symptoms, and service use among female patients in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.001

- Bosworth HB, Parsey KS, Butterfield MI, et al. Racial variation in wanting and obtaining mental health services among women veterans in a primary care clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:231-236.

- Luo J, Rosales M, Wei G, et al. Hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and case-fatality outcomes in US veterans with COVID-19 disease between years 2020-2021. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;70:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.04.003

- Kondo K, Low A, Everson T, et al. Health disparities in veterans: a map of the evidence. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S9-S15. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000756

- Grosicki GJ, Bunsawat K, Jeong S, Robinson AT. Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic disease and COVID-19 outcomes in White, Black/African American, and Latinx populations: Social determinants of health. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;71:4-10. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2022.04.004

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U.S.). Division of Viral Diseases. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups: June 4, 2020. CDC Stacks. June 4, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/88770

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891-1892. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6548

- Magesh S, John D, Li WT, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2134147. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147

- Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:398-417. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12229

- Social Vulnerability Index. Agency for Toxicity and Disease Registry. July 22, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

- Moss JL, Johnson NJ, Yu M, Altekruse SF, Cronin KA. Comparisons of individual- and area-level socioeconomic status as proxies for individual-level measures: evidence from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities study. Popul Health Metr. 2021;19:1. doi:10.1186/s12963-020-00244-x

- DC Department of Human Services. Response to COVID-19. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://dhs.dc.gov/page/responsetocovid19

- Wang PG, Brisbon NM, Hubbell H, et al. Is the Gap Closing? Comparison of sociodemographic cisparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations and outcomes between two temporal waves of admissions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10:593-602. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01249-y

Median Income and Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Persons With COVID-19 at an Urban Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Median Income and Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Persons With COVID-19 at an Urban Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Weekends Off on Clinical Rotations? Examining Clinical Opportunity Trends on Weekdays vs Weekends During Internal Medicine Clerkship Rotations in Veterans Health Administration Inpatient Wards

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates an 80-hour weekly work limit for residents.1 In contrast, decisions regarding undergraduate medical education (UME) are strongly influenced locally, with individual institutions setting academic policy for students. These differences in oversight reflect fundamental differences in residents’ and students’ roles in patient care, power, and responsibility. Considering rotation schedules, internal medicine (IM) clerkship directors have discussed the relative value of weekend vs weekday duty during inpatient rotations, a scheduling topic of interest to students as well, though these conversations are limited by a lack of knowledge regarding admission patterns. Addressing this information gap would inform policy decisions.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is uniquely positioned to address questions about UME clinical experiences nationwide: annually, over 118,000 students representing 97% of US medical schools train at VHA facilities.2,3 We aim to compare the number and variety of patient encounter opportunities presenting during inpatient VHA IM rotations on weekdays versus weekends to inform policy decisions for UME rotation schedules.

Innovation

The VHA Corporate Data Warehouse will be queried for all admissions, diagnoses, and length of stay on inpatient IM services at the 420 VHA hospitals affiliated with US medical schools from 2016-2026. We will aggregate case data for day of week, floor, hospital, and Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN), and determine number of admissions by weekday (Monday-Friday) and weekend (Saturday-Sunday). Weekday vs. weekend admission data will be compared using generalized mixed effects models for clustered longitudinal data. Heterogeneity across hospitals and VISNs will be explored to examine unique regional trends.

Results

We have drafted strategies to query and curate relevant datasets, developed a preliminary analysis plan, and await data deployment from VHA data stewards.

Conclusions

We believe this will be the first VHA-wide evaluation of patient encounter trends on IM services to examine potential training experiences for medical students. This will increase understanding of the critical role VHA has in developing the nations’ healthcare workforce, and how patterns of opportunities for clinical education may be distributed over time, informing decisions about rotation schedules to maximize students’ abilities to interact with, learn from, and serve our nation’s veterans

- Dimitris KD, Taylor BC, Fankhauser RA. Resident work-week regulations: historical review and modern perspectives. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(4):290-296. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.05.011

- Health professions education statistics. Veterans Health Administration. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAACurrentStats.pdf

- Medical education at VA: It’s all about the Veterans. VA News. Updated August 16, 2021. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/93370/medical-education-at-va-its-all-about-the-veterans/

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates an 80-hour weekly work limit for residents.1 In contrast, decisions regarding undergraduate medical education (UME) are strongly influenced locally, with individual institutions setting academic policy for students. These differences in oversight reflect fundamental differences in residents’ and students’ roles in patient care, power, and responsibility. Considering rotation schedules, internal medicine (IM) clerkship directors have discussed the relative value of weekend vs weekday duty during inpatient rotations, a scheduling topic of interest to students as well, though these conversations are limited by a lack of knowledge regarding admission patterns. Addressing this information gap would inform policy decisions.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is uniquely positioned to address questions about UME clinical experiences nationwide: annually, over 118,000 students representing 97% of US medical schools train at VHA facilities.2,3 We aim to compare the number and variety of patient encounter opportunities presenting during inpatient VHA IM rotations on weekdays versus weekends to inform policy decisions for UME rotation schedules.

Innovation

The VHA Corporate Data Warehouse will be queried for all admissions, diagnoses, and length of stay on inpatient IM services at the 420 VHA hospitals affiliated with US medical schools from 2016-2026. We will aggregate case data for day of week, floor, hospital, and Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN), and determine number of admissions by weekday (Monday-Friday) and weekend (Saturday-Sunday). Weekday vs. weekend admission data will be compared using generalized mixed effects models for clustered longitudinal data. Heterogeneity across hospitals and VISNs will be explored to examine unique regional trends.

Results

We have drafted strategies to query and curate relevant datasets, developed a preliminary analysis plan, and await data deployment from VHA data stewards.

Conclusions

We believe this will be the first VHA-wide evaluation of patient encounter trends on IM services to examine potential training experiences for medical students. This will increase understanding of the critical role VHA has in developing the nations’ healthcare workforce, and how patterns of opportunities for clinical education may be distributed over time, informing decisions about rotation schedules to maximize students’ abilities to interact with, learn from, and serve our nation’s veterans

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates an 80-hour weekly work limit for residents.1 In contrast, decisions regarding undergraduate medical education (UME) are strongly influenced locally, with individual institutions setting academic policy for students. These differences in oversight reflect fundamental differences in residents’ and students’ roles in patient care, power, and responsibility. Considering rotation schedules, internal medicine (IM) clerkship directors have discussed the relative value of weekend vs weekday duty during inpatient rotations, a scheduling topic of interest to students as well, though these conversations are limited by a lack of knowledge regarding admission patterns. Addressing this information gap would inform policy decisions.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is uniquely positioned to address questions about UME clinical experiences nationwide: annually, over 118,000 students representing 97% of US medical schools train at VHA facilities.2,3 We aim to compare the number and variety of patient encounter opportunities presenting during inpatient VHA IM rotations on weekdays versus weekends to inform policy decisions for UME rotation schedules.

Innovation

The VHA Corporate Data Warehouse will be queried for all admissions, diagnoses, and length of stay on inpatient IM services at the 420 VHA hospitals affiliated with US medical schools from 2016-2026. We will aggregate case data for day of week, floor, hospital, and Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN), and determine number of admissions by weekday (Monday-Friday) and weekend (Saturday-Sunday). Weekday vs. weekend admission data will be compared using generalized mixed effects models for clustered longitudinal data. Heterogeneity across hospitals and VISNs will be explored to examine unique regional trends.

Results

We have drafted strategies to query and curate relevant datasets, developed a preliminary analysis plan, and await data deployment from VHA data stewards.

Conclusions

We believe this will be the first VHA-wide evaluation of patient encounter trends on IM services to examine potential training experiences for medical students. This will increase understanding of the critical role VHA has in developing the nations’ healthcare workforce, and how patterns of opportunities for clinical education may be distributed over time, informing decisions about rotation schedules to maximize students’ abilities to interact with, learn from, and serve our nation’s veterans

- Dimitris KD, Taylor BC, Fankhauser RA. Resident work-week regulations: historical review and modern perspectives. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(4):290-296. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.05.011

- Health professions education statistics. Veterans Health Administration. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAACurrentStats.pdf

- Medical education at VA: It’s all about the Veterans. VA News. Updated August 16, 2021. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/93370/medical-education-at-va-its-all-about-the-veterans/

- Dimitris KD, Taylor BC, Fankhauser RA. Resident work-week regulations: historical review and modern perspectives. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(4):290-296. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.05.011

- Health professions education statistics. Veterans Health Administration. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.va.gov/oaa/docs/OAACurrentStats.pdf

- Medical education at VA: It’s all about the Veterans. VA News. Updated August 16, 2021. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/93370/medical-education-at-va-its-all-about-the-veterans/

Factors Influencing Outcomes of a Telehealth-Based Physical Activity Program in Older Veterans Postdischarge

Factors Influencing Outcomes of a Telehealth-Based Physical Activity Program in Older Veterans Postdischarge

Deconditioning among hospitalized older adults contributes to significant decline in posthospitalization functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity.1-10 Previous hospital-to-home interventions have targeted improving function and physical activity, including recent programs leveraging home telehealth as a feasible and potentially effective mode of delivering in-home exercise and rehabilitation.11-14 However, pilot interventions have shown mixed effectiveness.11,12,14 This study expands on a previously published intervention describing a pilot home telehealth program for veterans posthospital discharge that demonstrated significant 6-month improvement in physical activity as well as trends in physical function improvement, including among those with cognitive impairment.15 Factors that contribute to improved outcomes are the focus of the present study.

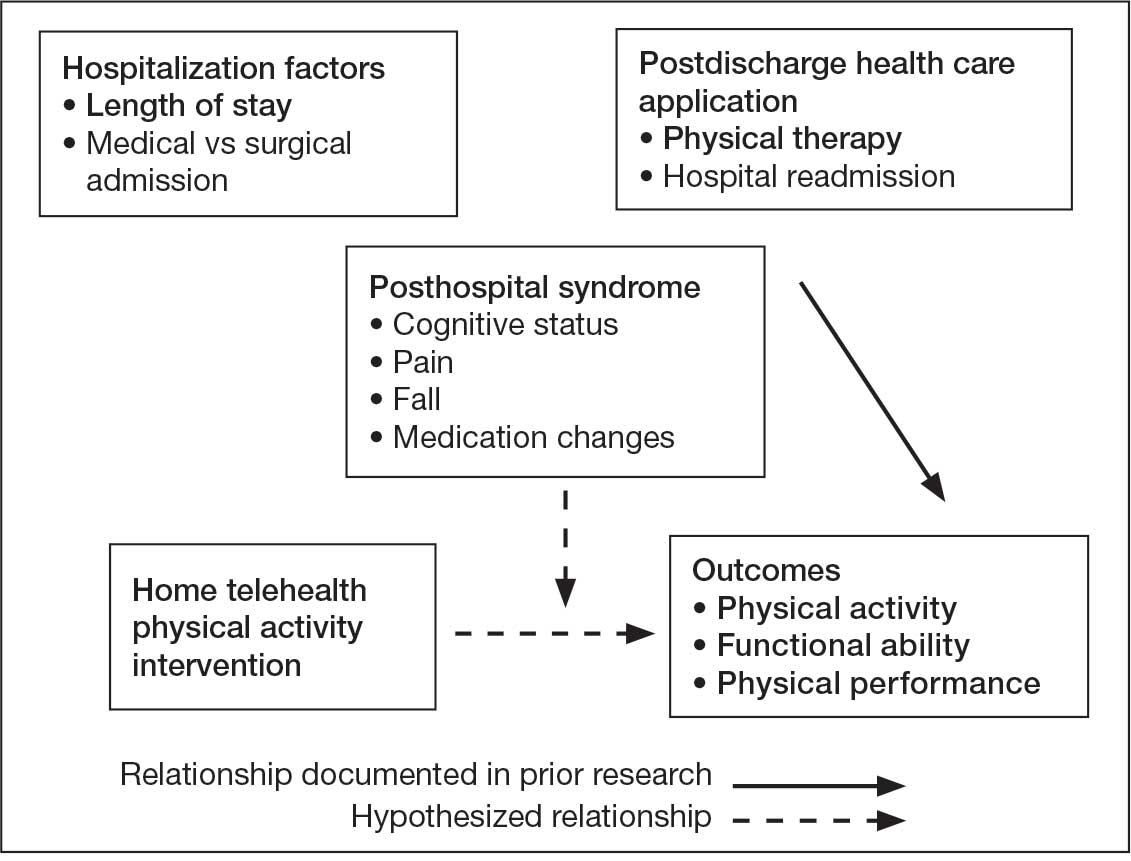

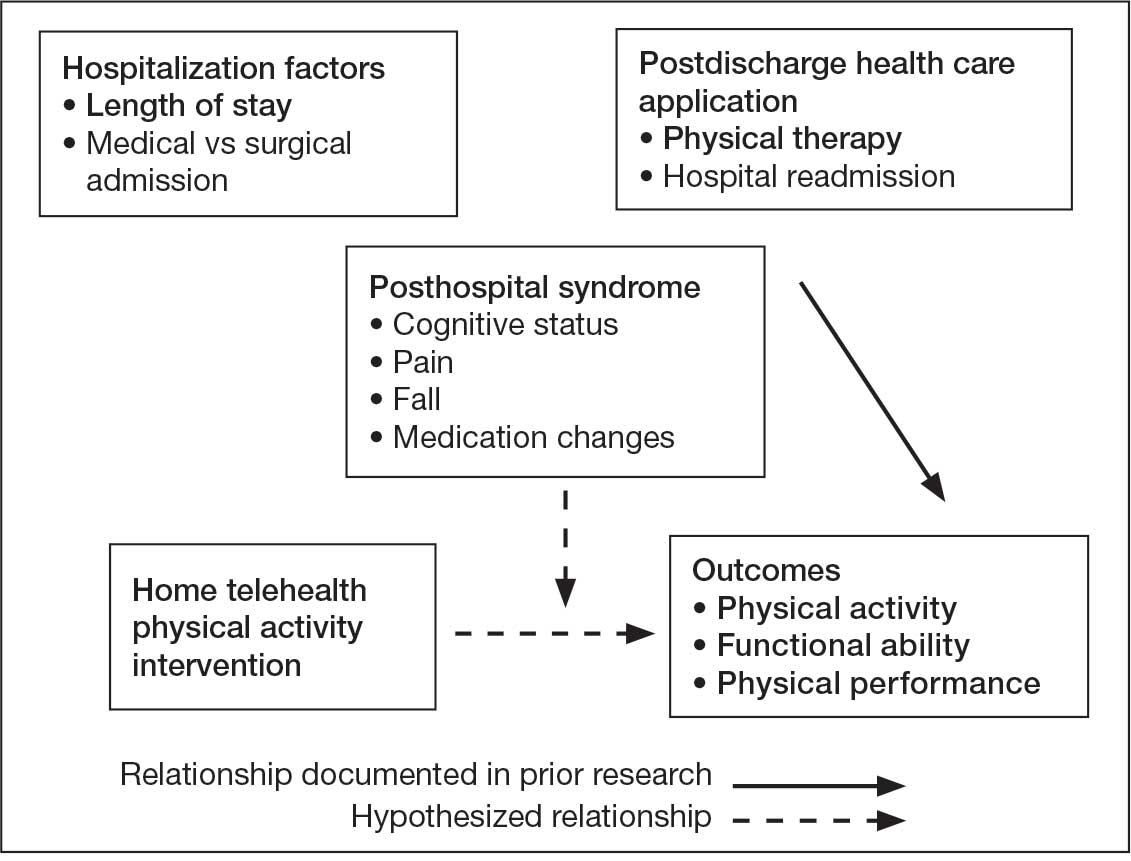

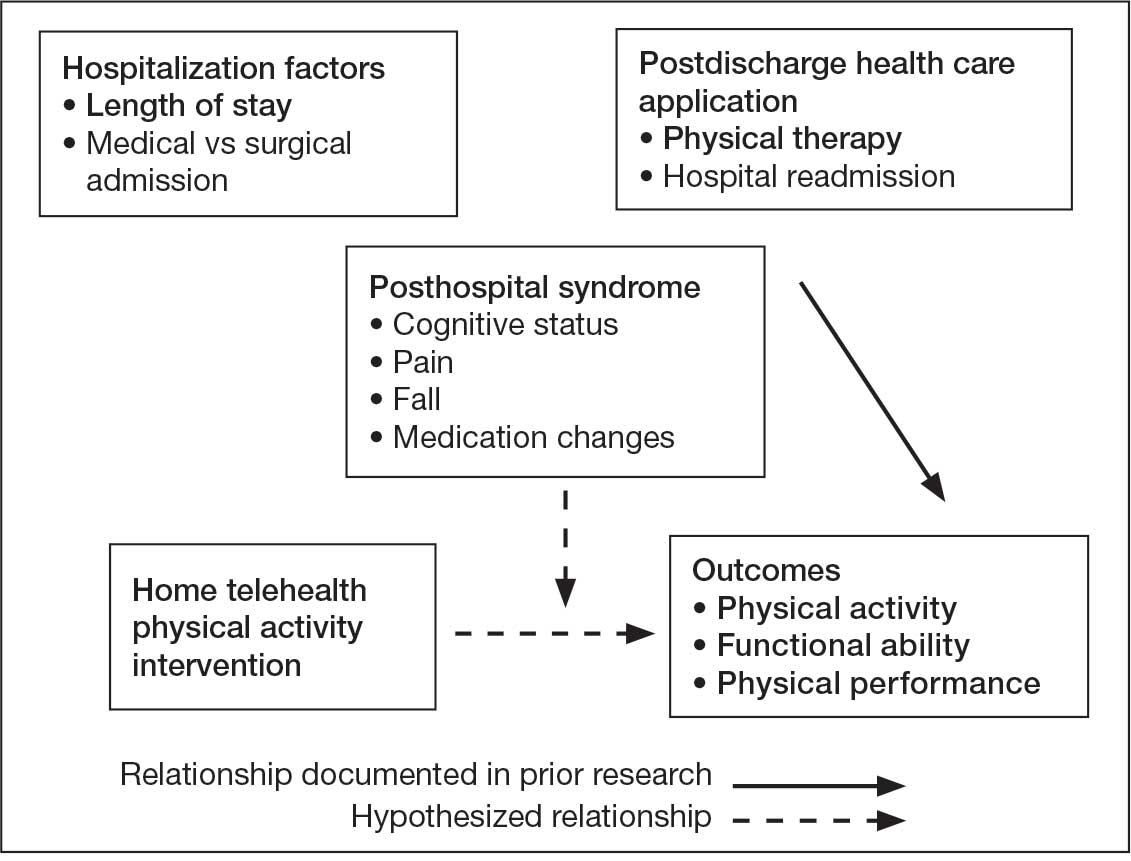

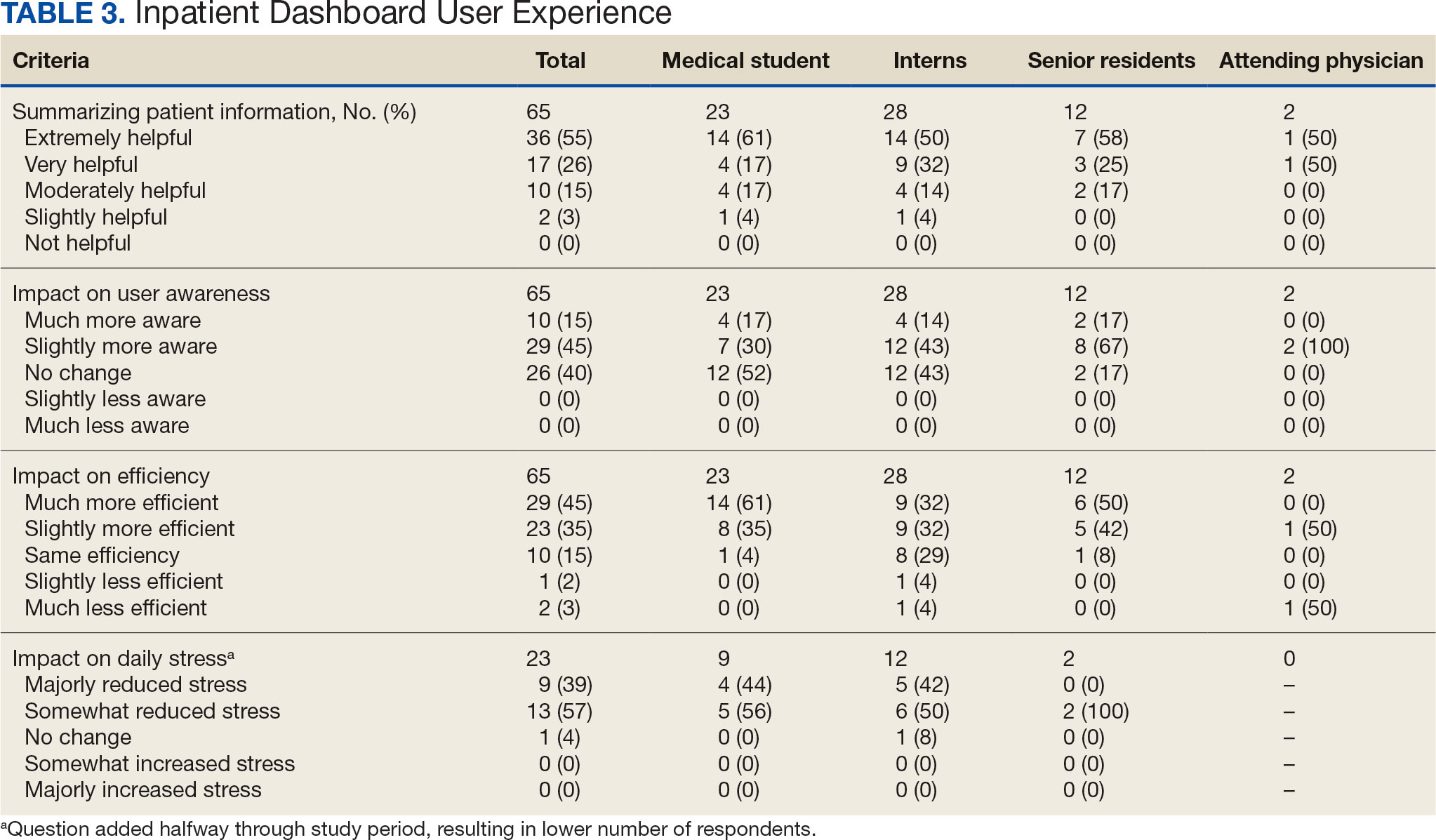

Key factors underlying the complexity of hospital-to-home transitions include hospitalization elements (ie, reason for admission and length of stay), associated posthospital syndromes (ie, postdischarge falls, medication changes, cognitive impairment, and pain), and postdischarge health care application (ie, physical therapy and hospital readmission).16-18 These factors may be associated with postdischarge functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity, but their direct influence on intervention outcomes is unclear (Figure 1).5,7,9,16-20 The objective of this study was to examine the influence of hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors on outcomes of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Video Connect (VVC) intervention to enhance function and physical activity in older adults posthospital discharge.

health care application factors on physical activity, functional ability, and

physical performance intervention outcomes.

Methods

The previous analysis reported on patient characteristics, program feasibility, and preliminary outcomes.13,15 The current study reports on relationships between hospitalization, posthospital syndrome, and postdischarge health care application factors and change in key outcomes, namely postdischarge self-reported functional ability, physical performance, and physical activity from baseline to endpoint.

Participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) Research and Development Committee, and the project was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04045054).

Intervention