User login

Overuse of Hematocrit Testing After Elective General Surgery at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

It is common practice to routinely measure postoperative hematocrit levels at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals for a wide range of elective general surgeries. While hematocrit measurement is a low-cost test, the high frequency with which these tests are performed may drastically increase overall costs.

Numerous studies have suggested that physicians overuse laboratory testing.1-10 Kohli and colleagues recommended that the routine practice of obtaining postoperative hematocrit tests following elective gynecologic surgery be abandoned.1 A similar recommendation was made by Olus and colleagues after studying uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections and by Wu and colleagues after investigating routine laboratory tests post total hip arthroplasty.2,3

To our knowledge, a study assessing routine postoperative hematocrit testing in elective general surgery has not yet been conducted. Many laboratory tests ordered in the perioperative period are not indicated, including complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and coagulation studies.4 Based on the results of these studies, we expected that the routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgeries at VA medical centers would not be cost effective. A PubMed search for articles published from 1990 to 2023 using the search terms “hematocrit,” “hemoglobin,” “general,” “surgery,” “routine,” and “cost” or “cost-effectiveness,” suggests that the clinical usefulness of postoperative hematocrit testing has not been well studied in the general surgery setting. The purpose of this study was to determine the clinical utility and associated cost of measuring routine postoperative hematocrit levels in order to generate a guide as to when the practice is warranted following common elective general surgery.

Although gynecologic textbooks may describe recommendations of routine hematocrit checking after elective gynecologic operations, one has difficulty finding the same recommendations in general surgery textbooks.1 However, it is common practice for surgical residents and attending surgeons to routinely order hematocrit on postoperative day-1 to ensure that the operation did not result in unsuspected anemia that then would need treatment (either with fluids or a blood transfusion). Many other surgeons rely on clinical factors such as tachycardia, oliguria, or hypotension to trigger a hematocrit (and other laboratory) tests. Our hypothesis is that the latter group has chosen the most cost-effective and prudent practice. One problem with checking the hematocrit routinely, as with any other screening test, is what to do with an abnormal result, assuming an asymptomatic patient? If the postoperative hematocrit is lower than expected given the estimated blood loss (EBL), what is one to do?

Methods

This retrospective case-control study conducted at the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) in Albuquerque compared data for patients who received transfusion within 72 hours of elective surgeries vs patients who did not. Patients who underwent elective general surgery from January 2011 through December 2014 were included. An elective general surgery was defined as surgery performed following an outpatient preoperative anesthesia evaluation ≥ 30 days prior to operation. Patients who underwent emergency operations, and those with baseline anemia (preoperative hematocrit < 30%), and those transfused > 72 hours after their operation were excluded. The NMVAHCSInstitutional Review Board approved this study (No. 15-H184).

A detailed record review was conducted to collect data on demographics and other preoperative risk factors, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), race and ethnicity, cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities, tobacco use, alcohol intake, diabetes, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, metabolic equivalent of task, hematologic conditions, and renal disease.

For each procedure, we recorded the type of elective general surgery performed, the diagnosis/indication, pre- and postoperative hemoglobin/hematocrit, intraoperative EBL, length of operation, surgical wound class, length of hospital stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) status, number of hematocrit tests, cardiovascular risk of operation (defined by anesthesia assessment), presence or absence of malignancy, preoperative platelet count, albumin level, preoperative prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalized ratio (INR), hemoglobin A1c, and incidence of transfusion. Signs and symptoms of anemia were recorded as present if the postoperative vital signs suggested low intravascular volume (pulse > 120 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, or vasoactive medication requirement [per anesthesia postoperative note]) or if the patient reported or exhibited symptoms of dizziness or fatigue or evidence of clinically apparent bleeding (ie, hematoma formation). Laboratory charges for hematocrit tests and CBC at the NMAVAHCS were used to assess cost.11

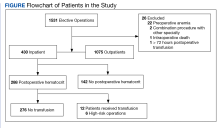

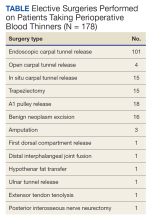

To stratify the transfusion risk, patients were distributed among 3 groups based on the following criteria: discharged home the same day as surgery; admitted but did not have postoperative hematocrit testing; and admitted and had postoperative hematocrit testing. We also stratified operations into low or high risk based on the risk for postoperative transfusion (Figure). Recognizing that the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy places bowel resection in a high-risk category, we designated a surgery as high risk when ≥ 2 patients in the transfusion group had that type of surgery over the 4 years of the study.12 Otherwise, the operations were deemed low risk.

Statistical Analysis

Numeric analysis used t tests and Binary and categorical variables used Fisher exact tests. P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. SAS software was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

From 2011 through 2014, 1531 patients had elective general surgery at NMVAHCS. Twenty-two patients with preoperative anemia (hematocrit < 30%) and 1 patient who received a transfusion > 72 hours after the operation were excluded. Most elective operations (70%, n = 1075) were performed on an outpatient basis; none involved transfusion. Inguinal hernia repair was most common with 479 operations; 17 patients were treated inpatient of which 2 patients had routine postoperative hematocrit checks; (neither received transfusion). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery received transfusion without routine postoperative hematocrit monitoring.

Of 112 partial colon resections, 1 patient had a postoperative transfusion; and all but 3 received postoperative hematocrit monitoring. Nineteen patients undergoing partial colon resection had a clinical indication for postoperative hematocrit monitoring. None of the 5 patients with partial gastrectomy received a postoperative transfusion. Of 121 elective cholecystectomies, no patients had postoperative transfusion, whereas 34 had postoperative hematocrit monitoring; only 2 patients had a clinical reason for the hematocrit monitoring.

Of 430 elective inpatient operations, 12 received transfusions and 288 patients had ≥ 1 postoperative hematocrit test (67%). All hematocrit tests were requested by the attending surgeon, resident surgeon, or the surgical ICU team. Of the group that had postoperative hematocrit monitoring, there was an average of 4.4 postoperative hematocrit tests per patient (range, 1-44).

There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 Five of the 12 patients received intraoperative transfusions while 7 were transfused within 72 hours postoperation. All but 1 patient receiving transfusion had EBL > 199 mL (range, 5-3000; mean, 950 mL; median, 500 mL) and/or signs or symptoms of anemia or other indications for measurement of the postoperative hematocrit. There were no statistically significant differences in patients’ age, sex, BMI, or race and ethnicity between groups receiving and not receiving transfusion (Table 1).

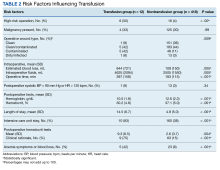

When comparing the transfusion vs the nontransfusion groups (after excluding those with clinical preoperative anemia) the risk factors for transfusion included: relatively low mean preoperative hematocrit (mean, 36.9% vs 42.7%, respectively; P = .003), low postoperative hematocrit (mean, 30.2% vs 37.1%, respectively; P < .001), high EBL (mean, 844 mL vs 109 mL, respectively; P = .005), large infusion of intraoperative fluids (mean, 4625 mL vs 2505 mL, respectively; P = .005), longer duration of operation (mean, 397 min vs 183 min, respectively; P < .001), and longer LOS (mean, 14.5 d vs 4.9 d, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Similarly, we found an increased risk for transfusion with high/intermediate cardiovascular risk (vs low), any wound not classified as clean, ICU stay, and postoperative symptoms of anemia.

We found no increased risk for transfusion with ethanol, tobacco, warfarin, or clopidogrel use; polycythemia; thrombocytopenia; preoperative INR; preoperative aPTT; preoperative albumin; Hemoglobin A1c; or diabetes mellitus; or for operations performed for malignancy. Ten patients in the ICU received transfusion (5.8%) compared with 2 patients (0.8%) not admitted to the ICU.

Operations were deemed high risk when ≥ 2 of patients having that operation received transfusions within 72 hours of their operation. There were 15 abdominoperineal resections; 3 of these received transfusions (20%). There were 7 total abdominal colectomies; 3 of these received transfusions (43%). We therefore had 22 high-risk operations, 6 of which were transfused (27%).

Discussion

Routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgery at NMVAHCS was not necessary. There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 We found that routine postoperative hematocrit measurements to assess anemia had little or no effect on clinical decision-making or clinical outcomes.

According to our results, 88% of initial hematocrit tests after elective partial colectomies could have been eliminated; only 32 of 146 patients demonstrated a clinical reason for postoperative hematocrit testing. Similarly, 36 of 40 postcholecystectomy hematocrit tests (90%) could have been eliminated had the surgeons relied on clinical signs indicating possible postoperative anemia (none were transfused). Excluding patients with major intraoperative blood loss (> 300 mL), only 29 of 288 (10%) patients who had postoperative hematocrit tests had a clinical indication for a postoperative hematocrit test (ie, symptoms of anemia and/or active bleeding). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery who received transfusion was taking an anticoagulant and had a clinically indicated hematocrit test for a large hematoma that eventually required reoperation.

Our study found that routine hematocrit checks may actually increase the risk that a patient would receive an unnecessary transfusion. For instance, one elderly patient, after a right colectomy, had 6 hematocrit levels while on a heparin drip and received transfusion despite being asymptomatic. His lowest hematocrit level prior to transfusion was 23.7%. This patient had a total of 18 hematocrit tests. His EBL was 350 mL and his first postoperative HCT level was 33.1%. In another instance, a patient undergoing abdominoperineal resection had a transfusion on postoperative day 1, despite being hypertensive, with a hematocrit that ranged from 26% before transfusion to 31% after the transfusion. These 2 cases illustrate what has been shown in a recent study: A substantial number of patients with colorectal cancer receive unnecessary transfusions.14 On the other hand, one ileostomy closure patient had 33 hematocrit tests, yet his initial postoperative hematocrit was 37%, and he never received a transfusion. With low-risk surgeries, clinical judgment should dictate when a postoperative hematocrit level is needed. This strategy would have eliminated 206 unnecessary initial postoperative hematocrit tests (72%), could have decreased the number of unnecessary transfusions, and would have saved NMVAHCS about $1600 annually.

Abdominoperineal resections and total abdominal colectomies accounted for a high proportion of transfusions in our study. Inpatient elective operations can be risk stratified and have routine hematocrit tests ordered for patients at high risk. The probability of transfusion was greater in high-risk vs low-risk surgeries; 27% (6 of 22 patients) vs 2% (6 of 408 patients), respectively (P < .001). Since 14 of the 22 patients undergoing high-risk operation already had clinical reasons for a postoperative hematocrit test, we only need to add the remaining 8 patients with high-risk operations to the 74 who had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test and conclude that 82 of 430 patients (19%) had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test, either from signs or symptoms of blood loss or because they were in a high-risk group.

While our elective general surgery cases may not represent many general surgery programs in the US and VA health care systems, we can extrapolate cost savings using the same cost analyses outlined by Kohli and colleagues.1 Assuming 1.9 million elective inpatient general surgeries per year in the United States with an average cost of $21 per CBC, the annual cost of universal postoperative hematocrit testing would be $40 million.11,15 If postoperative hematocrit testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 51% of the inpatient general surgeries would be approximately $20.4 million. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our finding that 19% were deemed necessary) results in an annual savings of $30 million. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were 4.4 hematocrit tests per patient; therefore, we have about $132 million in savings.

Assuming 181,384 elective VA inpatient general surgeries each year, costing $7.14 per CBC (the NMVAHCS cost), the VA could save $1.3 million annually. If postoperative HCT testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 50.4% of inpatient general surgery operations would be about $653,000. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our 19%) results in annual VA savings of $330,000. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were on average 4.4 hematocrit levels per patient; therefore, we estimate that annual savings for the VA of about $1.45 million.

Limitations

The retrospective chart review nature of this study may have led to selection bias. Only a small number of patients received a transfusion, which may have skewed the data. This study population comes from a single VA medical center; this patient population may not be reflective of other VA medical centers or the US population as a whole. Given that NMVAHCS does not perform hepatic, esophageal, pancreas, or transplant operations, the potential savings to both the US and the VA may be overestimated, but this could be studied in the future by VA medical centers that perform more complex operations.

Conclusions

This study found that over a 4-year period routine postoperative hematocrit tests for patients undergoing elective general surgery at a VA medical center were not necessary. General surgeons routinely order various pre- and postoperative laboratory tests despite their limited utility. Reduction in unneeded routine tests could result in notable savings to the VA without compromising quality of care.

Only general surgery patients undergoing operations that carry a high risk for needing a blood transfusion should have a routine postoperative hematocrit testing. In our study population, the chance of an elective colectomy, cholecystectomy, or hernia patient needing a transfusion was rare. This strategy could eliminate a considerable number of unnecessary blood tests and would potentially yield significant savings.

1. Kohli N, Mallipeddi PK, Neff JM, Sze EH, Roat TW. Routine hematocrit after elective gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):847-850. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00796-1

2. Olus A, Orhan, U, Murat A, et al. Do asymptomatic patients require routine hemoglobin testing following uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(2):195-199. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1093-1

3. Wu XD, Zhu ZL, Xiao P, Liu JC, Wang JW, Huang W. Are routine postoperative laboratory tests necessary after primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(10):2892-2898. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.097

4. Kumar A, Srivastava U. Role of routine laboratory investigations in preoperative evaluation. J Anesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27(2):174-179. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.81824

5. Aghajanian A, Grimes DA. Routine prothrombin time determination before elective gynecologic operations. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(5 Pt 1):837-839.

6. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Malone JM Jr. A cost-effectiveness evaluation of preoperative type-and-screen testing for vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(5):1201-1203. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70028-5

7. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Hosseini RB. Cost-effectiveness of routine blood type and screen testing before elective laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(3):346-348. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00187-V

8. Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):522-538. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1067

9. Weil IA, Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Schiltz NK, Seicean A. Use and utility of hemostatic screening in adults undergoing elective, non-cardiac surgery. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0139139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139139

10. Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2481-2488. doi:10.1001/jama.297.22.2481

11. Healthcare Bluebook. Complete blood count (CBC) with differential. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.healthcarebluebook.com/page_ProcedureDetails.aspx?id=214&dataset=lab

12. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Murad MH, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: an American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest. 2022;162(5):e207-e243. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.07.025

13. Randall JA, Wagner KT, Brody F. Perioperative transfusions in veterans following noncardiac procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33(10):923-931. doi:10.1089/lap. 2023.0307

14. Tartter PI, Barron DM. Unnecessary blood transfusions in elective colorectal cancer surgery. Transfusion. 1985;25(2):113-115. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25285169199.x

15. Steiner CA, Karaca Z, Moore BJ, Imshaug MC, Pickens G. Surgeries in hospital-based ambulatory surgery and hospital inpatient settings, 2014. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project statistical brief #223. May 2017. Revised July 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb223-Ambulatory-Inpatient-Surgeries-2014.pdf

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Surgery Office. Quarterly report: Q3 of fiscal year 2017. VISN operative complexity summary [Source not verified].

It is common practice to routinely measure postoperative hematocrit levels at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals for a wide range of elective general surgeries. While hematocrit measurement is a low-cost test, the high frequency with which these tests are performed may drastically increase overall costs.

Numerous studies have suggested that physicians overuse laboratory testing.1-10 Kohli and colleagues recommended that the routine practice of obtaining postoperative hematocrit tests following elective gynecologic surgery be abandoned.1 A similar recommendation was made by Olus and colleagues after studying uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections and by Wu and colleagues after investigating routine laboratory tests post total hip arthroplasty.2,3

To our knowledge, a study assessing routine postoperative hematocrit testing in elective general surgery has not yet been conducted. Many laboratory tests ordered in the perioperative period are not indicated, including complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and coagulation studies.4 Based on the results of these studies, we expected that the routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgeries at VA medical centers would not be cost effective. A PubMed search for articles published from 1990 to 2023 using the search terms “hematocrit,” “hemoglobin,” “general,” “surgery,” “routine,” and “cost” or “cost-effectiveness,” suggests that the clinical usefulness of postoperative hematocrit testing has not been well studied in the general surgery setting. The purpose of this study was to determine the clinical utility and associated cost of measuring routine postoperative hematocrit levels in order to generate a guide as to when the practice is warranted following common elective general surgery.

Although gynecologic textbooks may describe recommendations of routine hematocrit checking after elective gynecologic operations, one has difficulty finding the same recommendations in general surgery textbooks.1 However, it is common practice for surgical residents and attending surgeons to routinely order hematocrit on postoperative day-1 to ensure that the operation did not result in unsuspected anemia that then would need treatment (either with fluids or a blood transfusion). Many other surgeons rely on clinical factors such as tachycardia, oliguria, or hypotension to trigger a hematocrit (and other laboratory) tests. Our hypothesis is that the latter group has chosen the most cost-effective and prudent practice. One problem with checking the hematocrit routinely, as with any other screening test, is what to do with an abnormal result, assuming an asymptomatic patient? If the postoperative hematocrit is lower than expected given the estimated blood loss (EBL), what is one to do?

Methods

This retrospective case-control study conducted at the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) in Albuquerque compared data for patients who received transfusion within 72 hours of elective surgeries vs patients who did not. Patients who underwent elective general surgery from January 2011 through December 2014 were included. An elective general surgery was defined as surgery performed following an outpatient preoperative anesthesia evaluation ≥ 30 days prior to operation. Patients who underwent emergency operations, and those with baseline anemia (preoperative hematocrit < 30%), and those transfused > 72 hours after their operation were excluded. The NMVAHCSInstitutional Review Board approved this study (No. 15-H184).

A detailed record review was conducted to collect data on demographics and other preoperative risk factors, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), race and ethnicity, cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities, tobacco use, alcohol intake, diabetes, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, metabolic equivalent of task, hematologic conditions, and renal disease.

For each procedure, we recorded the type of elective general surgery performed, the diagnosis/indication, pre- and postoperative hemoglobin/hematocrit, intraoperative EBL, length of operation, surgical wound class, length of hospital stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) status, number of hematocrit tests, cardiovascular risk of operation (defined by anesthesia assessment), presence or absence of malignancy, preoperative platelet count, albumin level, preoperative prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalized ratio (INR), hemoglobin A1c, and incidence of transfusion. Signs and symptoms of anemia were recorded as present if the postoperative vital signs suggested low intravascular volume (pulse > 120 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, or vasoactive medication requirement [per anesthesia postoperative note]) or if the patient reported or exhibited symptoms of dizziness or fatigue or evidence of clinically apparent bleeding (ie, hematoma formation). Laboratory charges for hematocrit tests and CBC at the NMAVAHCS were used to assess cost.11

To stratify the transfusion risk, patients were distributed among 3 groups based on the following criteria: discharged home the same day as surgery; admitted but did not have postoperative hematocrit testing; and admitted and had postoperative hematocrit testing. We also stratified operations into low or high risk based on the risk for postoperative transfusion (Figure). Recognizing that the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy places bowel resection in a high-risk category, we designated a surgery as high risk when ≥ 2 patients in the transfusion group had that type of surgery over the 4 years of the study.12 Otherwise, the operations were deemed low risk.

Statistical Analysis

Numeric analysis used t tests and Binary and categorical variables used Fisher exact tests. P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. SAS software was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

From 2011 through 2014, 1531 patients had elective general surgery at NMVAHCS. Twenty-two patients with preoperative anemia (hematocrit < 30%) and 1 patient who received a transfusion > 72 hours after the operation were excluded. Most elective operations (70%, n = 1075) were performed on an outpatient basis; none involved transfusion. Inguinal hernia repair was most common with 479 operations; 17 patients were treated inpatient of which 2 patients had routine postoperative hematocrit checks; (neither received transfusion). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery received transfusion without routine postoperative hematocrit monitoring.

Of 112 partial colon resections, 1 patient had a postoperative transfusion; and all but 3 received postoperative hematocrit monitoring. Nineteen patients undergoing partial colon resection had a clinical indication for postoperative hematocrit monitoring. None of the 5 patients with partial gastrectomy received a postoperative transfusion. Of 121 elective cholecystectomies, no patients had postoperative transfusion, whereas 34 had postoperative hematocrit monitoring; only 2 patients had a clinical reason for the hematocrit monitoring.

Of 430 elective inpatient operations, 12 received transfusions and 288 patients had ≥ 1 postoperative hematocrit test (67%). All hematocrit tests were requested by the attending surgeon, resident surgeon, or the surgical ICU team. Of the group that had postoperative hematocrit monitoring, there was an average of 4.4 postoperative hematocrit tests per patient (range, 1-44).

There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 Five of the 12 patients received intraoperative transfusions while 7 were transfused within 72 hours postoperation. All but 1 patient receiving transfusion had EBL > 199 mL (range, 5-3000; mean, 950 mL; median, 500 mL) and/or signs or symptoms of anemia or other indications for measurement of the postoperative hematocrit. There were no statistically significant differences in patients’ age, sex, BMI, or race and ethnicity between groups receiving and not receiving transfusion (Table 1).

When comparing the transfusion vs the nontransfusion groups (after excluding those with clinical preoperative anemia) the risk factors for transfusion included: relatively low mean preoperative hematocrit (mean, 36.9% vs 42.7%, respectively; P = .003), low postoperative hematocrit (mean, 30.2% vs 37.1%, respectively; P < .001), high EBL (mean, 844 mL vs 109 mL, respectively; P = .005), large infusion of intraoperative fluids (mean, 4625 mL vs 2505 mL, respectively; P = .005), longer duration of operation (mean, 397 min vs 183 min, respectively; P < .001), and longer LOS (mean, 14.5 d vs 4.9 d, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Similarly, we found an increased risk for transfusion with high/intermediate cardiovascular risk (vs low), any wound not classified as clean, ICU stay, and postoperative symptoms of anemia.

We found no increased risk for transfusion with ethanol, tobacco, warfarin, or clopidogrel use; polycythemia; thrombocytopenia; preoperative INR; preoperative aPTT; preoperative albumin; Hemoglobin A1c; or diabetes mellitus; or for operations performed for malignancy. Ten patients in the ICU received transfusion (5.8%) compared with 2 patients (0.8%) not admitted to the ICU.

Operations were deemed high risk when ≥ 2 of patients having that operation received transfusions within 72 hours of their operation. There were 15 abdominoperineal resections; 3 of these received transfusions (20%). There were 7 total abdominal colectomies; 3 of these received transfusions (43%). We therefore had 22 high-risk operations, 6 of which were transfused (27%).

Discussion

Routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgery at NMVAHCS was not necessary. There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 We found that routine postoperative hematocrit measurements to assess anemia had little or no effect on clinical decision-making or clinical outcomes.

According to our results, 88% of initial hematocrit tests after elective partial colectomies could have been eliminated; only 32 of 146 patients demonstrated a clinical reason for postoperative hematocrit testing. Similarly, 36 of 40 postcholecystectomy hematocrit tests (90%) could have been eliminated had the surgeons relied on clinical signs indicating possible postoperative anemia (none were transfused). Excluding patients with major intraoperative blood loss (> 300 mL), only 29 of 288 (10%) patients who had postoperative hematocrit tests had a clinical indication for a postoperative hematocrit test (ie, symptoms of anemia and/or active bleeding). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery who received transfusion was taking an anticoagulant and had a clinically indicated hematocrit test for a large hematoma that eventually required reoperation.

Our study found that routine hematocrit checks may actually increase the risk that a patient would receive an unnecessary transfusion. For instance, one elderly patient, after a right colectomy, had 6 hematocrit levels while on a heparin drip and received transfusion despite being asymptomatic. His lowest hematocrit level prior to transfusion was 23.7%. This patient had a total of 18 hematocrit tests. His EBL was 350 mL and his first postoperative HCT level was 33.1%. In another instance, a patient undergoing abdominoperineal resection had a transfusion on postoperative day 1, despite being hypertensive, with a hematocrit that ranged from 26% before transfusion to 31% after the transfusion. These 2 cases illustrate what has been shown in a recent study: A substantial number of patients with colorectal cancer receive unnecessary transfusions.14 On the other hand, one ileostomy closure patient had 33 hematocrit tests, yet his initial postoperative hematocrit was 37%, and he never received a transfusion. With low-risk surgeries, clinical judgment should dictate when a postoperative hematocrit level is needed. This strategy would have eliminated 206 unnecessary initial postoperative hematocrit tests (72%), could have decreased the number of unnecessary transfusions, and would have saved NMVAHCS about $1600 annually.

Abdominoperineal resections and total abdominal colectomies accounted for a high proportion of transfusions in our study. Inpatient elective operations can be risk stratified and have routine hematocrit tests ordered for patients at high risk. The probability of transfusion was greater in high-risk vs low-risk surgeries; 27% (6 of 22 patients) vs 2% (6 of 408 patients), respectively (P < .001). Since 14 of the 22 patients undergoing high-risk operation already had clinical reasons for a postoperative hematocrit test, we only need to add the remaining 8 patients with high-risk operations to the 74 who had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test and conclude that 82 of 430 patients (19%) had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test, either from signs or symptoms of blood loss or because they were in a high-risk group.

While our elective general surgery cases may not represent many general surgery programs in the US and VA health care systems, we can extrapolate cost savings using the same cost analyses outlined by Kohli and colleagues.1 Assuming 1.9 million elective inpatient general surgeries per year in the United States with an average cost of $21 per CBC, the annual cost of universal postoperative hematocrit testing would be $40 million.11,15 If postoperative hematocrit testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 51% of the inpatient general surgeries would be approximately $20.4 million. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our finding that 19% were deemed necessary) results in an annual savings of $30 million. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were 4.4 hematocrit tests per patient; therefore, we have about $132 million in savings.

Assuming 181,384 elective VA inpatient general surgeries each year, costing $7.14 per CBC (the NMVAHCS cost), the VA could save $1.3 million annually. If postoperative HCT testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 50.4% of inpatient general surgery operations would be about $653,000. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our 19%) results in annual VA savings of $330,000. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were on average 4.4 hematocrit levels per patient; therefore, we estimate that annual savings for the VA of about $1.45 million.

Limitations

The retrospective chart review nature of this study may have led to selection bias. Only a small number of patients received a transfusion, which may have skewed the data. This study population comes from a single VA medical center; this patient population may not be reflective of other VA medical centers or the US population as a whole. Given that NMVAHCS does not perform hepatic, esophageal, pancreas, or transplant operations, the potential savings to both the US and the VA may be overestimated, but this could be studied in the future by VA medical centers that perform more complex operations.

Conclusions

This study found that over a 4-year period routine postoperative hematocrit tests for patients undergoing elective general surgery at a VA medical center were not necessary. General surgeons routinely order various pre- and postoperative laboratory tests despite their limited utility. Reduction in unneeded routine tests could result in notable savings to the VA without compromising quality of care.

Only general surgery patients undergoing operations that carry a high risk for needing a blood transfusion should have a routine postoperative hematocrit testing. In our study population, the chance of an elective colectomy, cholecystectomy, or hernia patient needing a transfusion was rare. This strategy could eliminate a considerable number of unnecessary blood tests and would potentially yield significant savings.

It is common practice to routinely measure postoperative hematocrit levels at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals for a wide range of elective general surgeries. While hematocrit measurement is a low-cost test, the high frequency with which these tests are performed may drastically increase overall costs.

Numerous studies have suggested that physicians overuse laboratory testing.1-10 Kohli and colleagues recommended that the routine practice of obtaining postoperative hematocrit tests following elective gynecologic surgery be abandoned.1 A similar recommendation was made by Olus and colleagues after studying uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections and by Wu and colleagues after investigating routine laboratory tests post total hip arthroplasty.2,3

To our knowledge, a study assessing routine postoperative hematocrit testing in elective general surgery has not yet been conducted. Many laboratory tests ordered in the perioperative period are not indicated, including complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and coagulation studies.4 Based on the results of these studies, we expected that the routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgeries at VA medical centers would not be cost effective. A PubMed search for articles published from 1990 to 2023 using the search terms “hematocrit,” “hemoglobin,” “general,” “surgery,” “routine,” and “cost” or “cost-effectiveness,” suggests that the clinical usefulness of postoperative hematocrit testing has not been well studied in the general surgery setting. The purpose of this study was to determine the clinical utility and associated cost of measuring routine postoperative hematocrit levels in order to generate a guide as to when the practice is warranted following common elective general surgery.

Although gynecologic textbooks may describe recommendations of routine hematocrit checking after elective gynecologic operations, one has difficulty finding the same recommendations in general surgery textbooks.1 However, it is common practice for surgical residents and attending surgeons to routinely order hematocrit on postoperative day-1 to ensure that the operation did not result in unsuspected anemia that then would need treatment (either with fluids or a blood transfusion). Many other surgeons rely on clinical factors such as tachycardia, oliguria, or hypotension to trigger a hematocrit (and other laboratory) tests. Our hypothesis is that the latter group has chosen the most cost-effective and prudent practice. One problem with checking the hematocrit routinely, as with any other screening test, is what to do with an abnormal result, assuming an asymptomatic patient? If the postoperative hematocrit is lower than expected given the estimated blood loss (EBL), what is one to do?

Methods

This retrospective case-control study conducted at the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) in Albuquerque compared data for patients who received transfusion within 72 hours of elective surgeries vs patients who did not. Patients who underwent elective general surgery from January 2011 through December 2014 were included. An elective general surgery was defined as surgery performed following an outpatient preoperative anesthesia evaluation ≥ 30 days prior to operation. Patients who underwent emergency operations, and those with baseline anemia (preoperative hematocrit < 30%), and those transfused > 72 hours after their operation were excluded. The NMVAHCSInstitutional Review Board approved this study (No. 15-H184).

A detailed record review was conducted to collect data on demographics and other preoperative risk factors, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), race and ethnicity, cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities, tobacco use, alcohol intake, diabetes, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, metabolic equivalent of task, hematologic conditions, and renal disease.

For each procedure, we recorded the type of elective general surgery performed, the diagnosis/indication, pre- and postoperative hemoglobin/hematocrit, intraoperative EBL, length of operation, surgical wound class, length of hospital stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) status, number of hematocrit tests, cardiovascular risk of operation (defined by anesthesia assessment), presence or absence of malignancy, preoperative platelet count, albumin level, preoperative prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalized ratio (INR), hemoglobin A1c, and incidence of transfusion. Signs and symptoms of anemia were recorded as present if the postoperative vital signs suggested low intravascular volume (pulse > 120 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, or vasoactive medication requirement [per anesthesia postoperative note]) or if the patient reported or exhibited symptoms of dizziness or fatigue or evidence of clinically apparent bleeding (ie, hematoma formation). Laboratory charges for hematocrit tests and CBC at the NMAVAHCS were used to assess cost.11

To stratify the transfusion risk, patients were distributed among 3 groups based on the following criteria: discharged home the same day as surgery; admitted but did not have postoperative hematocrit testing; and admitted and had postoperative hematocrit testing. We also stratified operations into low or high risk based on the risk for postoperative transfusion (Figure). Recognizing that the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy places bowel resection in a high-risk category, we designated a surgery as high risk when ≥ 2 patients in the transfusion group had that type of surgery over the 4 years of the study.12 Otherwise, the operations were deemed low risk.

Statistical Analysis

Numeric analysis used t tests and Binary and categorical variables used Fisher exact tests. P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. SAS software was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

From 2011 through 2014, 1531 patients had elective general surgery at NMVAHCS. Twenty-two patients with preoperative anemia (hematocrit < 30%) and 1 patient who received a transfusion > 72 hours after the operation were excluded. Most elective operations (70%, n = 1075) were performed on an outpatient basis; none involved transfusion. Inguinal hernia repair was most common with 479 operations; 17 patients were treated inpatient of which 2 patients had routine postoperative hematocrit checks; (neither received transfusion). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery received transfusion without routine postoperative hematocrit monitoring.

Of 112 partial colon resections, 1 patient had a postoperative transfusion; and all but 3 received postoperative hematocrit monitoring. Nineteen patients undergoing partial colon resection had a clinical indication for postoperative hematocrit monitoring. None of the 5 patients with partial gastrectomy received a postoperative transfusion. Of 121 elective cholecystectomies, no patients had postoperative transfusion, whereas 34 had postoperative hematocrit monitoring; only 2 patients had a clinical reason for the hematocrit monitoring.

Of 430 elective inpatient operations, 12 received transfusions and 288 patients had ≥ 1 postoperative hematocrit test (67%). All hematocrit tests were requested by the attending surgeon, resident surgeon, or the surgical ICU team. Of the group that had postoperative hematocrit monitoring, there was an average of 4.4 postoperative hematocrit tests per patient (range, 1-44).

There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 Five of the 12 patients received intraoperative transfusions while 7 were transfused within 72 hours postoperation. All but 1 patient receiving transfusion had EBL > 199 mL (range, 5-3000; mean, 950 mL; median, 500 mL) and/or signs or symptoms of anemia or other indications for measurement of the postoperative hematocrit. There were no statistically significant differences in patients’ age, sex, BMI, or race and ethnicity between groups receiving and not receiving transfusion (Table 1).

When comparing the transfusion vs the nontransfusion groups (after excluding those with clinical preoperative anemia) the risk factors for transfusion included: relatively low mean preoperative hematocrit (mean, 36.9% vs 42.7%, respectively; P = .003), low postoperative hematocrit (mean, 30.2% vs 37.1%, respectively; P < .001), high EBL (mean, 844 mL vs 109 mL, respectively; P = .005), large infusion of intraoperative fluids (mean, 4625 mL vs 2505 mL, respectively; P = .005), longer duration of operation (mean, 397 min vs 183 min, respectively; P < .001), and longer LOS (mean, 14.5 d vs 4.9 d, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Similarly, we found an increased risk for transfusion with high/intermediate cardiovascular risk (vs low), any wound not classified as clean, ICU stay, and postoperative symptoms of anemia.

We found no increased risk for transfusion with ethanol, tobacco, warfarin, or clopidogrel use; polycythemia; thrombocytopenia; preoperative INR; preoperative aPTT; preoperative albumin; Hemoglobin A1c; or diabetes mellitus; or for operations performed for malignancy. Ten patients in the ICU received transfusion (5.8%) compared with 2 patients (0.8%) not admitted to the ICU.

Operations were deemed high risk when ≥ 2 of patients having that operation received transfusions within 72 hours of their operation. There were 15 abdominoperineal resections; 3 of these received transfusions (20%). There were 7 total abdominal colectomies; 3 of these received transfusions (43%). We therefore had 22 high-risk operations, 6 of which were transfused (27%).

Discussion

Routine measurement of postoperative hematocrit levels after elective general surgery at NMVAHCS was not necessary. There were 12 transfusions for inpatients (2.8%), which is similar to the findings of a recent study of VA general surgery (2.3%).13 We found that routine postoperative hematocrit measurements to assess anemia had little or no effect on clinical decision-making or clinical outcomes.

According to our results, 88% of initial hematocrit tests after elective partial colectomies could have been eliminated; only 32 of 146 patients demonstrated a clinical reason for postoperative hematocrit testing. Similarly, 36 of 40 postcholecystectomy hematocrit tests (90%) could have been eliminated had the surgeons relied on clinical signs indicating possible postoperative anemia (none were transfused). Excluding patients with major intraoperative blood loss (> 300 mL), only 29 of 288 (10%) patients who had postoperative hematocrit tests had a clinical indication for a postoperative hematocrit test (ie, symptoms of anemia and/or active bleeding). One patient with inguinal hernia surgery who received transfusion was taking an anticoagulant and had a clinically indicated hematocrit test for a large hematoma that eventually required reoperation.

Our study found that routine hematocrit checks may actually increase the risk that a patient would receive an unnecessary transfusion. For instance, one elderly patient, after a right colectomy, had 6 hematocrit levels while on a heparin drip and received transfusion despite being asymptomatic. His lowest hematocrit level prior to transfusion was 23.7%. This patient had a total of 18 hematocrit tests. His EBL was 350 mL and his first postoperative HCT level was 33.1%. In another instance, a patient undergoing abdominoperineal resection had a transfusion on postoperative day 1, despite being hypertensive, with a hematocrit that ranged from 26% before transfusion to 31% after the transfusion. These 2 cases illustrate what has been shown in a recent study: A substantial number of patients with colorectal cancer receive unnecessary transfusions.14 On the other hand, one ileostomy closure patient had 33 hematocrit tests, yet his initial postoperative hematocrit was 37%, and he never received a transfusion. With low-risk surgeries, clinical judgment should dictate when a postoperative hematocrit level is needed. This strategy would have eliminated 206 unnecessary initial postoperative hematocrit tests (72%), could have decreased the number of unnecessary transfusions, and would have saved NMVAHCS about $1600 annually.

Abdominoperineal resections and total abdominal colectomies accounted for a high proportion of transfusions in our study. Inpatient elective operations can be risk stratified and have routine hematocrit tests ordered for patients at high risk. The probability of transfusion was greater in high-risk vs low-risk surgeries; 27% (6 of 22 patients) vs 2% (6 of 408 patients), respectively (P < .001). Since 14 of the 22 patients undergoing high-risk operation already had clinical reasons for a postoperative hematocrit test, we only need to add the remaining 8 patients with high-risk operations to the 74 who had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test and conclude that 82 of 430 patients (19%) had a clinical reason for a hematocrit test, either from signs or symptoms of blood loss or because they were in a high-risk group.

While our elective general surgery cases may not represent many general surgery programs in the US and VA health care systems, we can extrapolate cost savings using the same cost analyses outlined by Kohli and colleagues.1 Assuming 1.9 million elective inpatient general surgeries per year in the United States with an average cost of $21 per CBC, the annual cost of universal postoperative hematocrit testing would be $40 million.11,15 If postoperative hematocrit testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 51% of the inpatient general surgeries would be approximately $20.4 million. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our finding that 19% were deemed necessary) results in an annual savings of $30 million. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were 4.4 hematocrit tests per patient; therefore, we have about $132 million in savings.

Assuming 181,384 elective VA inpatient general surgeries each year, costing $7.14 per CBC (the NMVAHCS cost), the VA could save $1.3 million annually. If postoperative HCT testing were 70% consistent with our findings, the annual cost for hematocrit tests on 50.4% of inpatient general surgery operations would be about $653,000. A reduction in routine hematocrit testing to 25% of all inpatient general surgeries (vs our 19%) results in annual VA savings of $330,000. This conservative estimate could be even higher since there were on average 4.4 hematocrit levels per patient; therefore, we estimate that annual savings for the VA of about $1.45 million.

Limitations

The retrospective chart review nature of this study may have led to selection bias. Only a small number of patients received a transfusion, which may have skewed the data. This study population comes from a single VA medical center; this patient population may not be reflective of other VA medical centers or the US population as a whole. Given that NMVAHCS does not perform hepatic, esophageal, pancreas, or transplant operations, the potential savings to both the US and the VA may be overestimated, but this could be studied in the future by VA medical centers that perform more complex operations.

Conclusions

This study found that over a 4-year period routine postoperative hematocrit tests for patients undergoing elective general surgery at a VA medical center were not necessary. General surgeons routinely order various pre- and postoperative laboratory tests despite their limited utility. Reduction in unneeded routine tests could result in notable savings to the VA without compromising quality of care.

Only general surgery patients undergoing operations that carry a high risk for needing a blood transfusion should have a routine postoperative hematocrit testing. In our study population, the chance of an elective colectomy, cholecystectomy, or hernia patient needing a transfusion was rare. This strategy could eliminate a considerable number of unnecessary blood tests and would potentially yield significant savings.

1. Kohli N, Mallipeddi PK, Neff JM, Sze EH, Roat TW. Routine hematocrit after elective gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):847-850. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00796-1

2. Olus A, Orhan, U, Murat A, et al. Do asymptomatic patients require routine hemoglobin testing following uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(2):195-199. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1093-1

3. Wu XD, Zhu ZL, Xiao P, Liu JC, Wang JW, Huang W. Are routine postoperative laboratory tests necessary after primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(10):2892-2898. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.097

4. Kumar A, Srivastava U. Role of routine laboratory investigations in preoperative evaluation. J Anesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27(2):174-179. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.81824

5. Aghajanian A, Grimes DA. Routine prothrombin time determination before elective gynecologic operations. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(5 Pt 1):837-839.

6. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Malone JM Jr. A cost-effectiveness evaluation of preoperative type-and-screen testing for vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(5):1201-1203. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70028-5

7. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Hosseini RB. Cost-effectiveness of routine blood type and screen testing before elective laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(3):346-348. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00187-V

8. Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):522-538. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1067

9. Weil IA, Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Schiltz NK, Seicean A. Use and utility of hemostatic screening in adults undergoing elective, non-cardiac surgery. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0139139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139139

10. Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2481-2488. doi:10.1001/jama.297.22.2481

11. Healthcare Bluebook. Complete blood count (CBC) with differential. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.healthcarebluebook.com/page_ProcedureDetails.aspx?id=214&dataset=lab

12. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Murad MH, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: an American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest. 2022;162(5):e207-e243. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.07.025

13. Randall JA, Wagner KT, Brody F. Perioperative transfusions in veterans following noncardiac procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33(10):923-931. doi:10.1089/lap. 2023.0307

14. Tartter PI, Barron DM. Unnecessary blood transfusions in elective colorectal cancer surgery. Transfusion. 1985;25(2):113-115. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25285169199.x

15. Steiner CA, Karaca Z, Moore BJ, Imshaug MC, Pickens G. Surgeries in hospital-based ambulatory surgery and hospital inpatient settings, 2014. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project statistical brief #223. May 2017. Revised July 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb223-Ambulatory-Inpatient-Surgeries-2014.pdf

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Surgery Office. Quarterly report: Q3 of fiscal year 2017. VISN operative complexity summary [Source not verified].

1. Kohli N, Mallipeddi PK, Neff JM, Sze EH, Roat TW. Routine hematocrit after elective gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):847-850. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00796-1

2. Olus A, Orhan, U, Murat A, et al. Do asymptomatic patients require routine hemoglobin testing following uneventful, unplanned cesarean sections? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(2):195-199. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1093-1

3. Wu XD, Zhu ZL, Xiao P, Liu JC, Wang JW, Huang W. Are routine postoperative laboratory tests necessary after primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(10):2892-2898. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.097

4. Kumar A, Srivastava U. Role of routine laboratory investigations in preoperative evaluation. J Anesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27(2):174-179. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.81824

5. Aghajanian A, Grimes DA. Routine prothrombin time determination before elective gynecologic operations. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(5 Pt 1):837-839.

6. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Malone JM Jr. A cost-effectiveness evaluation of preoperative type-and-screen testing for vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(5):1201-1203. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70028-5

7. Ransom SB, McNeeley SG, Hosseini RB. Cost-effectiveness of routine blood type and screen testing before elective laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(3):346-348. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00187-V

8. Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):522-538. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1067

9. Weil IA, Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Schiltz NK, Seicean A. Use and utility of hemostatic screening in adults undergoing elective, non-cardiac surgery. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0139139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139139

10. Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2481-2488. doi:10.1001/jama.297.22.2481

11. Healthcare Bluebook. Complete blood count (CBC) with differential. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.healthcarebluebook.com/page_ProcedureDetails.aspx?id=214&dataset=lab

12. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Murad MH, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: an American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest. 2022;162(5):e207-e243. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.07.025

13. Randall JA, Wagner KT, Brody F. Perioperative transfusions in veterans following noncardiac procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33(10):923-931. doi:10.1089/lap. 2023.0307

14. Tartter PI, Barron DM. Unnecessary blood transfusions in elective colorectal cancer surgery. Transfusion. 1985;25(2):113-115. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25285169199.x

15. Steiner CA, Karaca Z, Moore BJ, Imshaug MC, Pickens G. Surgeries in hospital-based ambulatory surgery and hospital inpatient settings, 2014. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project statistical brief #223. May 2017. Revised July 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb223-Ambulatory-Inpatient-Surgeries-2014.pdf

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Surgery Office. Quarterly report: Q3 of fiscal year 2017. VISN operative complexity summary [Source not verified].

Graduate Medical Education Financing in the US Department of Veterans Affairs

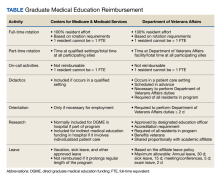

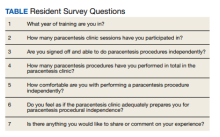

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has partnered with academic medical centers and programs since 1946 to provide clinical training for physician residents. Ranking second in federal graduate medical education (GME) funding to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the $850 million VA GME budget annually reimburses > 250 GME-sponsoring institutions (affiliates) of 8000 GME programs for the clinical training of 49,000 individual residents rotating through > 11,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.1 The VA also distributes $1.6 billion to VA facilities to offset the costs of conducting health professions education (HPE) (eg, facility infrastructure, salary support for VA instructors and preceptors, education office administration, and instructional equipment).2 The VA financial and educational contributions account for payment of 11% of resident positions nationally and allow academic medical centers to be less reliant on CMS GME funding.3,4 The VA contributions also provide opportunities for GME expansion,1,5,6 educational innovations,5,7 interprofessional and team-based care,8,9 and quality and safety training.10,11 The Table provides a comparison of CMS and VA GME reimbursability based on activity.

GME financing is complex, particularly the formulaic approach used by CMS, the details of which are often obscured in federal regulations. Due to this complexity and the $16 billion CMS GME budget, academic publications have focused on CMS GME financing while not fully explaining the VA GME policies and processes.4,12-14 By comparison, the VA GME financing model is relatively straightforward and governed by different statues and VA regulations, yet sharing some of the same principles as CMS regulations. Given the challenges in CMS reimbursement to fully support the cost of resident education, as well as the educational opportunities at the VA, the VA designs its reimbursement model to assure that affiliates receive appropriate payments.4,12,15 To ensure the continued success of VA GME partnerships, knowledge of VA GME financing has become increasingly important for designated institutional officers (DIOs) and residency program directors, particularly in light of recent investigations into oversight of the VA’s reimbursement to academic affiliates.

VA AUTHORITY

While the VA’s primary mission is “to provide a complete hospital medical service for the medical care and treatment of veterans,”early VA leaders recognized the importance of affiliating with the nation’s academic institutions.19 In 1946, the VA Policy Memorandum Number 2 established a partnership between the VA and the academic medical community.20 Additional legislation authorized specific agreements with academic affiliates for the central administration of salary and benefits for residents rotating at VA facilities. This process, known as disbursement, is an alternative payroll mechanism whereby the VA reimburses the academic affiliate for resident salary and benefits and the affiliate acts as the disbursing agent, issuing paychecks to residents.21,22

Resident FUNDING

By policy, with rare exceptions, the VA does not sponsor residency programs due to the challenges of providing an appropriate patient mix of age, sex, and medical conditions to meet accreditation standards.4 Nearly all VA reimbursements are for residents in affiliate-sponsored programs, while just 1% pays for residents in legacy, VA-sponsored residency programs at 2 VA facilities. The VA budget for resident (including fellows) salary and benefits is managed by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the national VA office responsible for oversight, policy, and funding of VA HPE programs.

Resident Salaries and Benefits

VA funding of resident salary and benefits are analogous with CMS direct GME (DGME), which is designed to cover resident salary and benefits costs.4,14,23 CMS DGME payments depend on a hospital’s volume of CMS inpatients and are based on a statutory formula, which uses the hospital’s resident FTE positions, the per-resident amount, and Medicare’s share of inpatient beds (Medicare patient load) to determine payments.12 The per-resident amount is set by statute, varies geographically, and is calculated by dividing the hospital’s allowable costs of GME (percentage of CMS inpatient days) divided by the number of residents.12,24

By comparison, the VA GME payment reimburses for each FTE based on the salary and benefits rate set by the academic affiliate. Reimbursement is calculated based on resident time spent at the VA multiplied by a daily salary rate. The daily salary rate is determined by dividing the resident’s total compensation (salary and benefits) by the number of calendar days in an academic year. Resident time spent at the VA facility is determined by obtaining rotation schedules provided by the academic affiliate and verifying resident clinical and educational activity during scheduled rotations.

Indirect Medical Education Funding

In addition to resident salary and benefits, funds to offset the cost of conducting HPE are provided to VA facilities. These funds are intended to improve and maintain necessary infrastructure for all HPE programs not just GME, including education office administration needs, teaching costs (ie, a portion of VA preceptors salary), and instructional equipment.

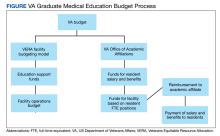

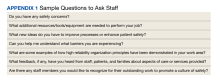

The Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) is a national budgeting process for VA medical facilities that funds facility operational needs such as staff salary and benefits, infrastructure, and equipment.2 The education portion of the VERA, the VERA Education Support Component (VESC), is not managed by the OAA, but rather is distributed through the VERA model to the general budget of VA facilities hosting HPE (Figure). VESC funding in the VA budget is based on labor mapping of physician time spent in education; other labor mapping categories include clinical care, research, and administration. VA facility VESC funding is calculated based on the number of paid health profession trainees (HPTs) from all professions, apportioned according to the number of FTEs for physician residents and VA-paid HPTs in other disciplines. In fiscal year 2024, VA facilities received $115,812 for each physician resident FTE position and $84,906 for each VA-paid, non-GME FTE position.

The VESC is like CMS's indirect GME funding, termed Indirect Medical Education (IME), an additional payment for each Medicare patient discharged reflecting teaching hospitals’ higher patient care costs relative to nonteaching hospitals. Described elsewhere, IME is calculated using a resident-to-bed ratio and a multiplier, which is set by statute.4,25 While IME can be used for reimbursement for some resident clinical and educational activities(eg, research), VA VESC funds cannot be used for such activities and are part of the general facility budget and appropriated per the discretion of the medical facility director.

ESTABLISHING GME PARTNERSHIPS

An affiliation agreement establishes the administrative and legal requirements for educational relationships with academic affiliates and includes standards for conducting HPE, responsibilities for accreditation standards, program leadership, faculty, resources, supervision, academic policies, and procedures. The VA uses standardized affiliation agreement templates that have been vetted with accrediting bodies and the VA Office of General Counsel.

A disbursement agreement authorizes the VA to reimburse affiliates for resident salary and benefits for VA clinical and educational activities. The disbursement agreement details the fiscal arrangements (eg, payment in advance vs arrears, salary, and benefit rates, leave) for the reimbursement payments. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1400.05 provides the policy and procedures for calculating reimbursement for HPT educational activities.26

The VA facility designated education officer (DEO) oversees all HPE programs and coordinates the affiliation and disbursement agreement processes.27 The DEO, affiliate DIO, residency program director, and VA residency site director determine the physician resident FTE positions assigned to a VA facility based on educational objectives and availability of educational resources at the VA facility, such as patient care opportunities, faculty supervisors, space, and equipment. The VA facility requests for resident FTE positions are submitted to the OAA by the facility DEO.

Once GME FTE positions are approved by the OAA, VA facilities work with their academic affiliate to submit the physician resident salary and benefit rate. Affiliate DIOs attest to the accuracy of the salary rate schedule and the local DEO submits the budget request to the OAA. Upon approval, the funds are transferred to the VA facility each fiscal year, which begins October 1. DEOs report quarterly to the OAA both budget needs and excesses based on variations in the approved FTEs due to additional VA rotations, physician resident attrition, or reassignment.

Resident Position Allocation

VA GME financing provides flexibility through periodic needs assessments and expansion initiatives. In August and December, DEOs collaborate with an academic affiliate to submit reports to the OAA confirming their projected GME needs for the next academic year. Additional positions requests are reviewed by the OAA; funding depends on budget and the educational justification. The OAA periodically issues GME expansion requests for proposal, which typically arise from legislation to address specific VA workforce needs. The VA facility DEO and affiliate GME leaders collaborate to apply for additional positions. For example, a VA GME expansion under the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 added 1500 GME positions in 8 years for critically needed specialties and in rural and underserved areas.5 The Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018 authorized a pilot program for VA to fund residents at non-VA facilities with priority for Indian Health Services, Tribes and Tribal Organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and US Department of Defense facilities to provide access to veterans in underserved areas.6

The VA GME financing system has flexibility to meet local needs for additional resident positions and to address broader VA workforce gaps through targeted expansion. Generally, CMS does not fund positions to address workforce needs, place residents in specific geographic areas, or require the training of certain types of residents.4 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 has provided the opportunity to address rural workforce needs.28

Reimbursement

The VA provides reimbursement for clinical and educational activities performed in VA facilities for the benefit of veterans as well as research, didactics, meetings and conferences, annual and sick leave, and orientation. The VA also may provide reimbursement for educational activities that occur off VA grounds (eg, the VA proportional share of a residency program’s didactic sessions). The VA does not reimburse for affiliate clinical duties or administrative costs, although a national policy allows VA facilities to reimburse affiliates for some GME overhead costs.29

CMS similarly reimburses for residency training time spent in patient care activities as well as orientation activities, didactics, leave, and, in some cases, research.4,30,31 CMS makes payments to hospitals, which may include sponsoring institutions and Medicare-eligible participating training sites.4,30,31 For both the VA and CMS, residents may not be counted twice for reimbursement by 2 federal agencies; in other words, a resident may not count for > 1 FTE.4,30-32

GME Oversight

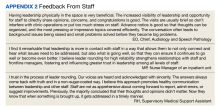

VA GME funding came under significant scrutiny. At a 2016 House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, Representative Phil Roe, MD (R-Tennessee), noted that no process existed at many VA facilities for “determining trainee presence” and that many VA medical centers had “difficulty tracking resident rotations”16 A VA Office of the Inspector General investigation recommended that the VA implement policies and procedures to improve oversight to “ensure residents are fully participating in educational activities” and that the VA is “paying the correct amount” to the affiliate.17 A 2020 General Accountability Office report outlined unclear policy guidance, incomplete tracking of resident activities, and improper fiscal processes for reimbursement and reconciliation of affiliate invoices.18

In response, the OAA created an oversight and compliance unit, revised VHA Directive 1400.05 (the policy for disbursement), and improved resident tracking procedures.26 The standard operating procedure that accompanied VHA Directive 1400.05 provides detailed information for the DEO and VA facility staff for tracking resident clinical and educational activities. FTE counts are essential to both VA and CMS for accurate reimbursement. The eAppendix and the Table provide a guide to reimbursable activities in the VA for the calculation of reimbursement, with a comparison to CMS.33,34 The OAA in cooperation with other VA staff and officers periodically conducts audits to assess compliance with disbursement policy and affiliate reimbursement accuracy.

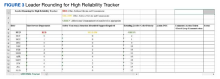

In the VA, resident activities are captured on the VA Educational Activity Record, a standardized spreadsheet to track activities and calculate reimbursement. Each VA facility hosting resident physicians manually records resident activity by the half-day. This process is labor intensive, involving both VA and affiliate staff to accurately reconcile payments. To address the workload demands, the OAA is developing an online tool that will automate aspects of the tracking process. Also, to ensure adequate staffing, the OAA is in the process of implementing an office optimization project, providing standardized position descriptions, an organizational chart, and staffing levels for DEO offices in VA facilities.

Conclusions

This report describes the key policies and principles of VA GME financing, highlighting the essential similarities and differences between VA and CMS. Neither the VA nor CMS regulations allow for reimbursement for > 1 FTE position per resident, a principle that underpins the assignment of resident rotations and federal funding for GME and are similar with respect to reimbursement for patient care activities, didactics, research, orientation, and scholarly activity. While reimbursable activities in the VA require physical presence and care of veteran patients, CMS also limits reimbursement to resident activities in the hospital and approved other settings if the hospital is paying for resident salary and benefits in these settings. The VA provides some flexibility for offsite activities including didactics and, in specific circumstances, remote care of veteran patients (eg, teleradiology).

The VA and CMS use different GME financing models. For example, the CMS calculations for resident FTEs are complex, whereas VA calculations reimburse the salary and benefits as set by the academic affiliate. The VA process accounts for local variation in salary rates, whereas the per-resident amount set by CMS varies regionally and does not fully account for differences in the cost of living.24 Because all patients in VA facilities are veterans, VA calculations for reimbursement do not involve ratios of beds like the CMS calculations to determine a proportional share of reimbursement. The VA GME expansion tends to be more directed to VA health workforce needs than CMS, specifying the types of programs and geographic locations to address these needs.

The VA regularly reevaluates how affiliates are reimbursed for VA resident activity, balancing compliance with VA policies and the workload for VA and its affiliates. The VA obtains input from key stakeholders including DEOs, DIOs, and professional organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.35,36

Looking ahead, the VA is developing an online tool to improve the accuracy of affiliate reimbursement. The VA will also implement a standardized staffing model, organizational structure, and position descriptions for DEO offices. These initiatives will help reduce the burden of tracking and verifying resident activity and continue to support the 77-year partnership between VA and its affiliated institutions.

1. Klink KA, Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM. Veterans Affairs graduate medical education expansion addresses US physician workforce needs. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1144-1150. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004545

2. Andrus CH, Johnson K, Pierce E, Romito PJ, Hartel P, Berrios‐Guccione S, Best W. Finance modeling in the delivery of medical care in tertiary‐care hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Surg Res. 2001;96(2):152-157. doi:10.1006/jsre.1999.5728

3. Petrakis IL, Kozal M. Academic medical centers and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a 75-year partnership influences medical education, scientific discovery, and clinical care. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1110-1113. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004734

4. Heisler EJ, Mendez BH, Mitchell A, Panangala SV, Villagrana MA. Federal support for graduate medical education: an overview (R44376). Congressional Research Service report R44376; version 11. Updated December 27, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44376/11

5. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000795

6. Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

7. Lypson ML, Roberts LW. Valuing the partnership between the Veterans Health Administration and academic medicine. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1091-1093. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004748

8. Harada ND, Traylor L, Rugen KW, et al. Interprofessional transformation of clinical education: the first six years of the Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(suppl 1):S86-S94. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1433642

9. Harada ND, Rajashekara S, Sansgiry S, et al. Developing interprofessional primary care teams: alumni evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519875455. doi:10.1177/2382120519875455

10. Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: experience from 10 years of training quality scholars. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1741-1748. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef

11. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs chief resident in quality and patient safety program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

12. He K, Whang E, Kristo G. Graduate medical education funding mechanisms, challenges, and solutions: a narrative review. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):65-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.007

13. Villagrana M. Medicare graduate medical education payments: an overview. Congressional Research Service report IF10960. Updated September 29, 2022. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10960