User login

Discharge Summary Completion

Discharge summaries (DS) correlate with rates of rehospitalization1, 2 and adverse events after discharge.3 The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations acknowledges their importance and mandates that certain elements be included.4 Thus far, however, DS are not standardized across institutions and there is no expectation that they be available at postdischarge visits. There have been numerous attempts to improve the quality of DS by using more structured formats or computer generated summaries with positive results in term of comprehensiveness, clarity, and practitioner satisfaction58 but with persistence of serious errors and omissions.9

Postgraduate training is often the first opportunity for physicians to learn information transfer management skills. Unfortunately, DS are created by house staff who have minimal training in this area11 and feel like they have to learn by osmosis,12 resulting in poor quality DS and lack of availability at the point of care.1315

Previous research suggested that individualized feedback sessions for Internal Medicine residents improved the quality of certain aspects of their completed DS.10 We postulated that an audit and feedback educational intervention on DS for first year geriatric medicine fellows would also improve their quality. This technique involves chart or case review of clinical practice behaviors for a specific task followed by recommendation of new behaviors when applicable.16 Audit and feedback incorporates adult learning theory,1719 an essential part of continuous quality improvement that fits within the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency of practice based learning and improvement,20 as an educational activity.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a preintervention post intervention study at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center (MSMC) in New York City between July 1, 2006 and June 30, 2007. The study received an exemption from the MSMC Institutional Review Board. First year geriatric medicine fellows at MSMC were required to complete 2 months of inpatient service; the first during the first 6 months of the academic year and the second during the last 6 months of the year. Fellows dictated all DS, which were transcribed and routed for signature to the attending of record. Prior to our study, a discharge summary template consisting of 21 items was developed for clinical use. Template items, agreed upon by an expert internal panel of geriatricians and interprofessional faculty, were selected for their importance in assuring a safe transition of older adults from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

Participants

All 5 first‐year fellows at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at MSMC were invited to participate in the study.

Intervention

Audit #1

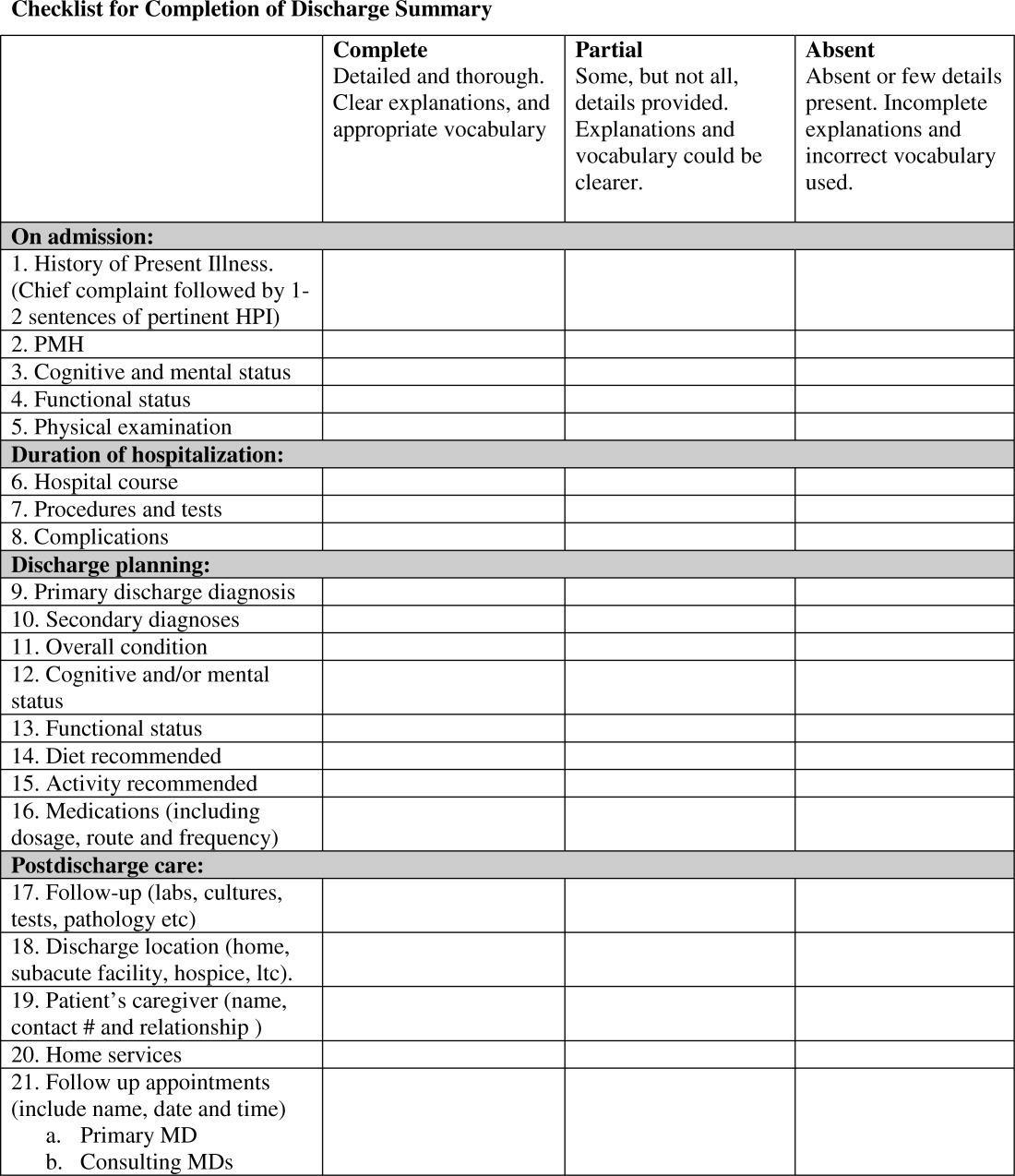

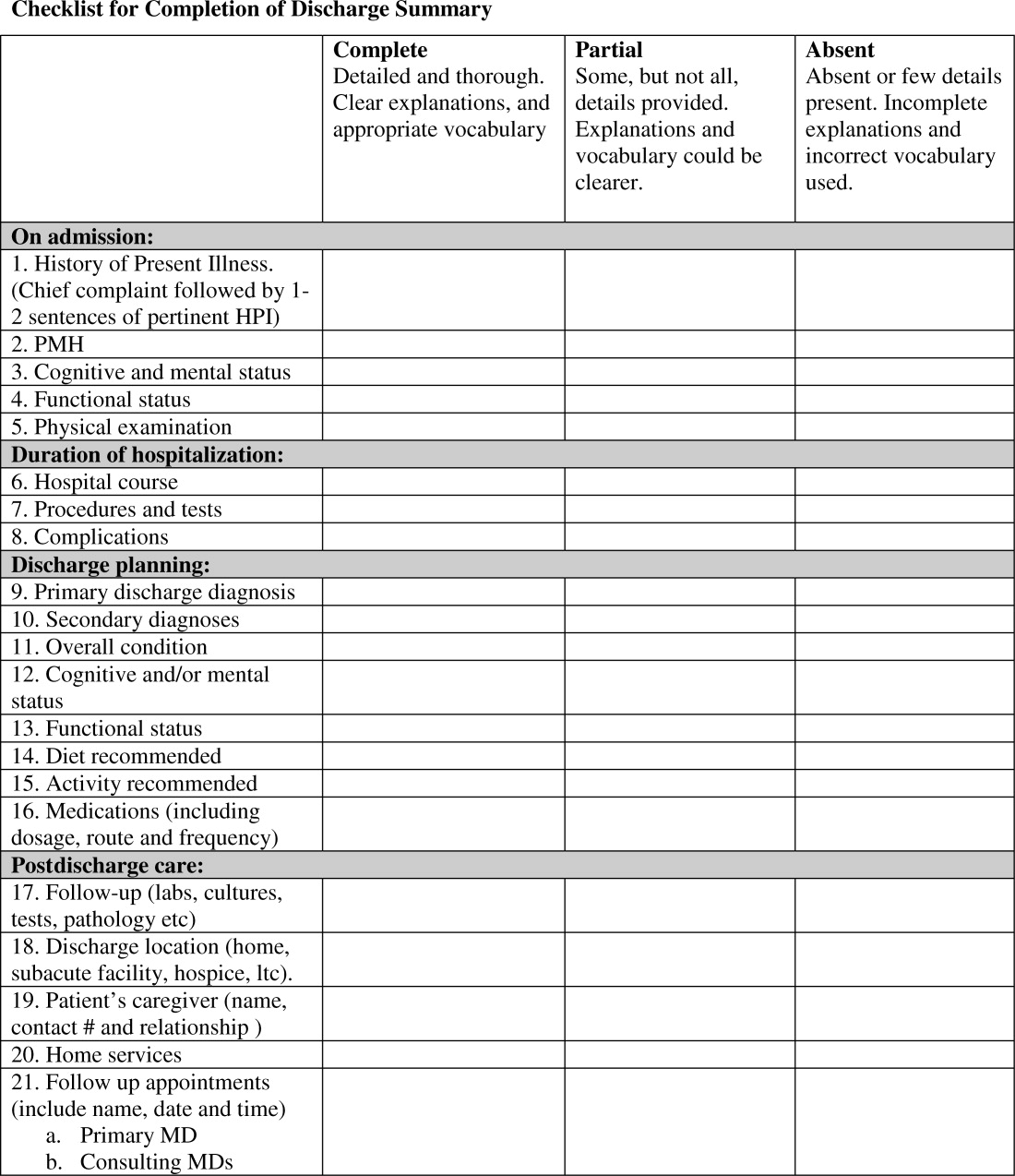

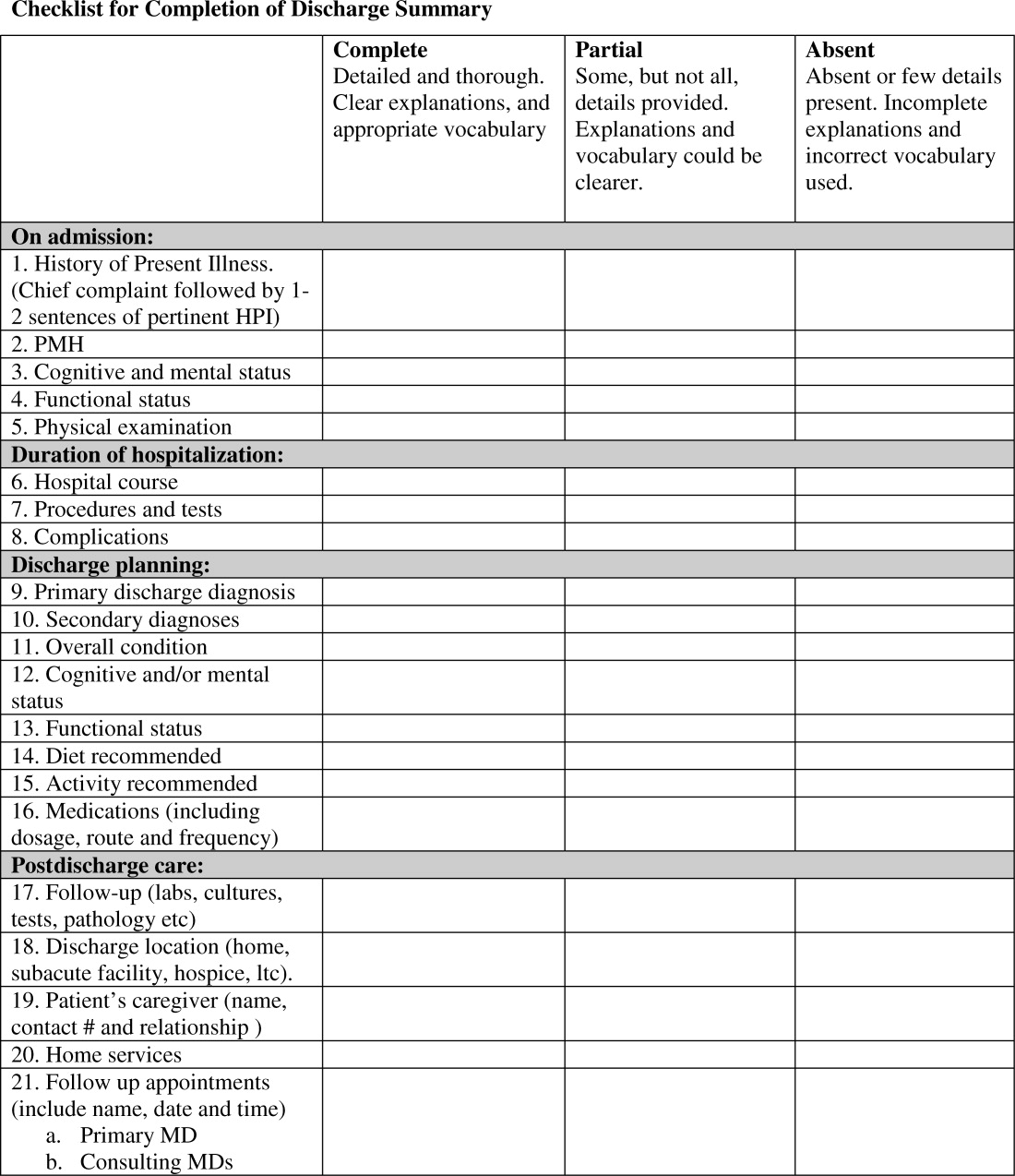

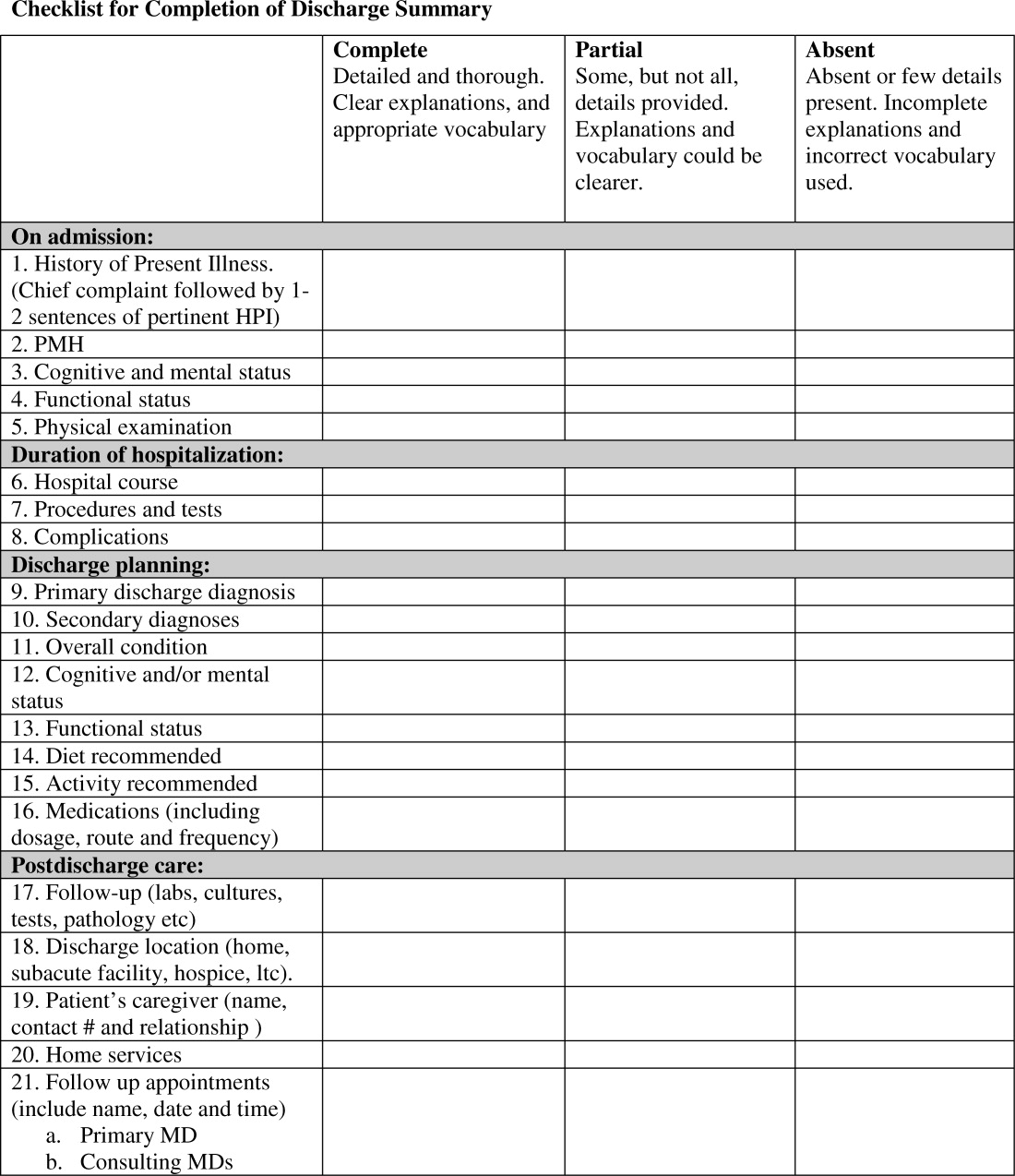

All available DS for each fellow's first month of inpatient service were audited for completeness of the 21 item discharge summary template by 1 author (AD). The 21 items were focused on 4 distinct periods of the hospitalization: admission, hospital course, discharge planning, and postdischarge care (Figure 1).

Content under each of the 21 items was classified as complete, partially complete, or absent. An item was considered complete if most information was present and appropriate medical terms were used, partially complete if information was unclear, and absent if no information was present for that area of the DS. To ensure investigator reliability, a random sample of 25% of each fellow's DS was scored by 2 additional investigators (RK and HF) and all disagreements were reviewed and resolved by consensus.

Feedback

Between December 2006 and January 2007, one‐on‐one formative feedback sessions were scheduled. The sessions were approximately 30 minutes long, confidential, performed by 1 of the authors (AD) and followed a written format. During these sessions, each fellow received the results of their discharge summary audit, each partially complete or absent item was discussed, and the importance of DS was emphasized.

Audit #2

All available DS for each fellow's second month of inpatient service were audited for completeness, using the same 21 item assessment tool and the same scoring system.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the impact of our audit and feedback intervention, we compared scores before and after formative feedback sessions, both overall and for the composite discharge summary scores for each of the 4 domains of care: admission, hospital course, discharge‐planning, and postdischarge care. Scores were dichotomized as being complete or partially complete or absent. We used generalized estimating equations to account for the clustering of DS within fellows. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2‐tailed and used a type I error rate of 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Five fellows participated, 4 of whom were women; 2 were in postgraduate year 4, 3 in year 5. A total of 158 DS were audited, 89 prefeedback and 79 postfeedback. Each fellow dictated an average of 17 DS during each inpatient month.

During Audit #1, the 21 item DS were complete among 71%, incomplete among 18%, absent among 11%. Admission items, hospital course items, and discharge planning items were complete among 70%, 78%, and 77% of DS respectively, but postdischarge items were complete among only 57%. Examining individual items, the lowest completion rates were found for test result follow‐up (42%), caregiver information (10%), and home services (64%), as well for assessment at admission and discharge of cognitive and mental status (56% and 53% respectively) and functional status (57% and 40%). Of note, all these items are of particular importance to geriatric care.

After receiving the audit and feedback intervention, fellows were more likely to complete all required discharge summary data when compared to prior‐to‐feedback (91% vs. 71%, P 0.001). Discharge summary completeness improved for all composite outcomes examining the four domains of care: admission (93% vs. 70%, P 0.001), hospital course (93% vs. 78%, P 0.001), discharge planning (93% vs. 77%, P 0.02), and postdischarge care (83% vs. 57%., P 0.001) (Table 1).

| Criteria | Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Absent | Complete | Absent | ||

| |||||

| Admission composite (5 items) | 70 (3585) | 30 (1565) | 93 (79100) | 7 (021) | 0.001 |

| HPI | 79 (38100) | 21 (1563) | 100 | 0 | 0.001 |

| PMH | 94 (75100) | 5 (025) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 56 (1979) | 44 (2182) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 57 (2588) | 43 (1375) | 97 (89100) | 2 (010) | 0.001 |

| Physical exam | 63 (19100) | 37 (082) | 72 (0100) | 28 (5100) | 0.27 |

| Hospital course composite (3 items) | 78 (2593) | 22 (775) | 93 (76100) | 7 (023) | 0.001 |

| Hospital course | 84 (25100) | 15 (076) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Procedures and tests | 70 (690) | 30 (1094) | 90 (57100) | 10 (043) | 0.001 |

| Complications | 80 (4490) | 20 (556) | 90 (77100) | 10 (023) | 0.07 |

| Discharge planning composite (8 items) | 77 (4989) | 22 (1151) | 93 (64100) | 7 (036) | 0.02 |

| Primary diagnosis | 93 (75100) | 6 (026) | 100 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Secondary diagnosis | 82 (56100) | 18 (044) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Overall condition | 81 (38100) | 19 (062) | 86 (21100) | 14 (079) | 0.47 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 53 (1380) | 57 (2088) | 97 (93100) | 3 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 40 (1381) | 50 (1988) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Diet | 89 (63100) | 12 (538) | 81 (0100) | 19 (0100) | 0.25 |

| Activity | 89 (69100) | 11 (032) | 82 (0100) | 18 (0100) | 0.49 |

| Medications | 83 (50100) | 17 (050) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Postdischarge care composite (5 items) | 57 (4183) | 43 (1759) | 83 (6998) | 18 (231) | 0.001 |

| F/U results | 42 (1190) | 58 (1089) | 81 (50100) | 20 (050) | 0.02 |

| Discharge location | 92 (88100) | 8 (012) | 100 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Caregiver info | 10 (025) | 89 (75100) | 48 (795) | 52 (584) | 0.001 |

| Home services | 64 (32100) | 35 (068) | 87 (7195) | 12 (029) | 0.001 |

| F/U appointments | 78 (33100) | 23 (067) | 96 (86100) | 4 (014) | 0.001 |

| Overall composite (21 items) | 71 (4287) | 29 (1358) | 91 (7399) | 9 (227) | 0.001 |

Discussion

Our study found that audit and feedback sessions significantly improved the completeness of DS dictated by geriatric medicine fellows at 1 academic medical center. Before feedback, completeness was high in most traditional areas of the DS including admission data, hospital course, and discharge planning, but was low in other areas critical for safe transitions of older adults such as postdischarge care, test follow‐up, caregiver information, and cognitive and functional status changes. These findings were surprising, as using a template should render a completion rate close to 100%. Notably, during feedback sessions, fellows suggested low completion rates were due to lack of awareness regarding the importance of completing all 21 items of the template and missing documentation in patient medical records.

Feedback sessions dramatically improved overall completeness of subsequent DS and in most of areas of specific importance for geriatric care, although we remain uncertain why all areas did not show improvement (for example, caregiver information completion remained low). One possible explanation is the lack of accurate documentation for all necessary items in the hospital medical record. Moreover, we did not observe completion improvement for other items, ie, diet and activity. Overall, we believe that drawing attention to areas of particular importance to geriatric care transitions and providing learners with individual reports on their performance increased their awareness and motivated changes to their practice, improving discharge summary completion.

Our study has limitations. This study was a pilot intervention without a control group, because of time and budgetary constraints. Also, we were unable to assess for sustainability because the fellows studied for this project graduated after the second audit. Third, we studied discharge summary completion; further research should focus on accuracy of discharge summary content. Finally, while we did not use any advanced technologies or materials, faculty time required to conduct the audit and feedback in this study was estimated at 45 hours. In our opinion this estimate would classify our audit and feedback intervention as a low external cost and moderately‐high human cost intervention, which may represent a potential barrier to generalizability. On the other hand, we believe that even an audit of a small sample of DS done by a physician could provide valuable data for feedback and would involve less faculty time.

Our finding that audit and feedback sessions improved the completeness of DS among house‐staff is important for 2 reasons. First, we were able to demonstrate that focused feedback targeted to areas of particular importance to the transition of older adults changed subsequent behavior and resulted in improved documentation of these areas. Second, our study provides evidence of a programmatic approach to address the ACGME competency of practice‐based learning and improvement. We believe that our intervention can be reproduced by training programs across the country and are hopeful that such interventions will result in improved patient outcomes during critical care transitions such as hospital discharge.

- ,Quality assessment of a discharge summary system.CMAJ.1995;152:1437–1442.

- ,,Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries.Intern Med J.2006;36:221–225.

- ,,,,The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org./. The Joint Commission Requirements/Hospitals/Record of Care/Patient safety. Accessed July2010.

- ,,,,General practitioners' attitudes to computer‐generated surgical discharge letters.Med J Aust.1992;157(6):380–382.

- ,,,Do primary care physicians prefer dictated or computer‐generated discharge summaries?Am J Dis Child.1993;147(9):986–988.

- ,,,,,Evaluation of a computer‐generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes.Br J Gen Pract.1998;48(429):1163–1164.

- ,,, et al.Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic dischanrge summary,J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):219–225.

- ,Communication with general practitioners after accident and emergency attendance: computer generated letters are often deficient.Emerg Med J.2003;20(3):256–257.

- ,,Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries.Int J Med Inform.2008;77:613–620.

- ,,,,,Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program.Acad Med.2006;81:S5–S8.

- ,,Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries.BMJ.1996;312:350.

- ,,,,,Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,,Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists.Dis Mon.2002;48:218–229.

- ,,Improving the continuity of care following discharge of patients hospitalized with heart failure: is the discharge summary adequate?Can J Cardiol.2003;19:365–370.

- Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews.Int J Technol Assess Health Care.2005;21:380–385.

- ,,, et al.Impact of feedback and didactic sessions on the reporting behavior of upper endoscopic findings by physicians and nurses.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2007;5:326–330.

- ,,Prospective assessment of the impact of feedback on colonoscopy performance.Aliment Pharmacol Ther.2006;24:313–318.

- ,,, et al.Inpatient care to community care: improving clinical handover in the private mental health setting.Med J Aust.2009;190(11 Suppl):S144–S149.

- Available at: http://www.Acgme.org, Record of care, Treatment, and Serives, Standard RC.02.04.01. Accessed July2010.

Discharge summaries (DS) correlate with rates of rehospitalization1, 2 and adverse events after discharge.3 The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations acknowledges their importance and mandates that certain elements be included.4 Thus far, however, DS are not standardized across institutions and there is no expectation that they be available at postdischarge visits. There have been numerous attempts to improve the quality of DS by using more structured formats or computer generated summaries with positive results in term of comprehensiveness, clarity, and practitioner satisfaction58 but with persistence of serious errors and omissions.9

Postgraduate training is often the first opportunity for physicians to learn information transfer management skills. Unfortunately, DS are created by house staff who have minimal training in this area11 and feel like they have to learn by osmosis,12 resulting in poor quality DS and lack of availability at the point of care.1315

Previous research suggested that individualized feedback sessions for Internal Medicine residents improved the quality of certain aspects of their completed DS.10 We postulated that an audit and feedback educational intervention on DS for first year geriatric medicine fellows would also improve their quality. This technique involves chart or case review of clinical practice behaviors for a specific task followed by recommendation of new behaviors when applicable.16 Audit and feedback incorporates adult learning theory,1719 an essential part of continuous quality improvement that fits within the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency of practice based learning and improvement,20 as an educational activity.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a preintervention post intervention study at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center (MSMC) in New York City between July 1, 2006 and June 30, 2007. The study received an exemption from the MSMC Institutional Review Board. First year geriatric medicine fellows at MSMC were required to complete 2 months of inpatient service; the first during the first 6 months of the academic year and the second during the last 6 months of the year. Fellows dictated all DS, which were transcribed and routed for signature to the attending of record. Prior to our study, a discharge summary template consisting of 21 items was developed for clinical use. Template items, agreed upon by an expert internal panel of geriatricians and interprofessional faculty, were selected for their importance in assuring a safe transition of older adults from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

Participants

All 5 first‐year fellows at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at MSMC were invited to participate in the study.

Intervention

Audit #1

All available DS for each fellow's first month of inpatient service were audited for completeness of the 21 item discharge summary template by 1 author (AD). The 21 items were focused on 4 distinct periods of the hospitalization: admission, hospital course, discharge planning, and postdischarge care (Figure 1).

Content under each of the 21 items was classified as complete, partially complete, or absent. An item was considered complete if most information was present and appropriate medical terms were used, partially complete if information was unclear, and absent if no information was present for that area of the DS. To ensure investigator reliability, a random sample of 25% of each fellow's DS was scored by 2 additional investigators (RK and HF) and all disagreements were reviewed and resolved by consensus.

Feedback

Between December 2006 and January 2007, one‐on‐one formative feedback sessions were scheduled. The sessions were approximately 30 minutes long, confidential, performed by 1 of the authors (AD) and followed a written format. During these sessions, each fellow received the results of their discharge summary audit, each partially complete or absent item was discussed, and the importance of DS was emphasized.

Audit #2

All available DS for each fellow's second month of inpatient service were audited for completeness, using the same 21 item assessment tool and the same scoring system.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the impact of our audit and feedback intervention, we compared scores before and after formative feedback sessions, both overall and for the composite discharge summary scores for each of the 4 domains of care: admission, hospital course, discharge‐planning, and postdischarge care. Scores were dichotomized as being complete or partially complete or absent. We used generalized estimating equations to account for the clustering of DS within fellows. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2‐tailed and used a type I error rate of 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Five fellows participated, 4 of whom were women; 2 were in postgraduate year 4, 3 in year 5. A total of 158 DS were audited, 89 prefeedback and 79 postfeedback. Each fellow dictated an average of 17 DS during each inpatient month.

During Audit #1, the 21 item DS were complete among 71%, incomplete among 18%, absent among 11%. Admission items, hospital course items, and discharge planning items were complete among 70%, 78%, and 77% of DS respectively, but postdischarge items were complete among only 57%. Examining individual items, the lowest completion rates were found for test result follow‐up (42%), caregiver information (10%), and home services (64%), as well for assessment at admission and discharge of cognitive and mental status (56% and 53% respectively) and functional status (57% and 40%). Of note, all these items are of particular importance to geriatric care.

After receiving the audit and feedback intervention, fellows were more likely to complete all required discharge summary data when compared to prior‐to‐feedback (91% vs. 71%, P 0.001). Discharge summary completeness improved for all composite outcomes examining the four domains of care: admission (93% vs. 70%, P 0.001), hospital course (93% vs. 78%, P 0.001), discharge planning (93% vs. 77%, P 0.02), and postdischarge care (83% vs. 57%., P 0.001) (Table 1).

| Criteria | Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Absent | Complete | Absent | ||

| |||||

| Admission composite (5 items) | 70 (3585) | 30 (1565) | 93 (79100) | 7 (021) | 0.001 |

| HPI | 79 (38100) | 21 (1563) | 100 | 0 | 0.001 |

| PMH | 94 (75100) | 5 (025) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 56 (1979) | 44 (2182) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 57 (2588) | 43 (1375) | 97 (89100) | 2 (010) | 0.001 |

| Physical exam | 63 (19100) | 37 (082) | 72 (0100) | 28 (5100) | 0.27 |

| Hospital course composite (3 items) | 78 (2593) | 22 (775) | 93 (76100) | 7 (023) | 0.001 |

| Hospital course | 84 (25100) | 15 (076) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Procedures and tests | 70 (690) | 30 (1094) | 90 (57100) | 10 (043) | 0.001 |

| Complications | 80 (4490) | 20 (556) | 90 (77100) | 10 (023) | 0.07 |

| Discharge planning composite (8 items) | 77 (4989) | 22 (1151) | 93 (64100) | 7 (036) | 0.02 |

| Primary diagnosis | 93 (75100) | 6 (026) | 100 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Secondary diagnosis | 82 (56100) | 18 (044) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Overall condition | 81 (38100) | 19 (062) | 86 (21100) | 14 (079) | 0.47 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 53 (1380) | 57 (2088) | 97 (93100) | 3 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 40 (1381) | 50 (1988) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Diet | 89 (63100) | 12 (538) | 81 (0100) | 19 (0100) | 0.25 |

| Activity | 89 (69100) | 11 (032) | 82 (0100) | 18 (0100) | 0.49 |

| Medications | 83 (50100) | 17 (050) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Postdischarge care composite (5 items) | 57 (4183) | 43 (1759) | 83 (6998) | 18 (231) | 0.001 |

| F/U results | 42 (1190) | 58 (1089) | 81 (50100) | 20 (050) | 0.02 |

| Discharge location | 92 (88100) | 8 (012) | 100 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Caregiver info | 10 (025) | 89 (75100) | 48 (795) | 52 (584) | 0.001 |

| Home services | 64 (32100) | 35 (068) | 87 (7195) | 12 (029) | 0.001 |

| F/U appointments | 78 (33100) | 23 (067) | 96 (86100) | 4 (014) | 0.001 |

| Overall composite (21 items) | 71 (4287) | 29 (1358) | 91 (7399) | 9 (227) | 0.001 |

Discussion

Our study found that audit and feedback sessions significantly improved the completeness of DS dictated by geriatric medicine fellows at 1 academic medical center. Before feedback, completeness was high in most traditional areas of the DS including admission data, hospital course, and discharge planning, but was low in other areas critical for safe transitions of older adults such as postdischarge care, test follow‐up, caregiver information, and cognitive and functional status changes. These findings were surprising, as using a template should render a completion rate close to 100%. Notably, during feedback sessions, fellows suggested low completion rates were due to lack of awareness regarding the importance of completing all 21 items of the template and missing documentation in patient medical records.

Feedback sessions dramatically improved overall completeness of subsequent DS and in most of areas of specific importance for geriatric care, although we remain uncertain why all areas did not show improvement (for example, caregiver information completion remained low). One possible explanation is the lack of accurate documentation for all necessary items in the hospital medical record. Moreover, we did not observe completion improvement for other items, ie, diet and activity. Overall, we believe that drawing attention to areas of particular importance to geriatric care transitions and providing learners with individual reports on their performance increased their awareness and motivated changes to their practice, improving discharge summary completion.

Our study has limitations. This study was a pilot intervention without a control group, because of time and budgetary constraints. Also, we were unable to assess for sustainability because the fellows studied for this project graduated after the second audit. Third, we studied discharge summary completion; further research should focus on accuracy of discharge summary content. Finally, while we did not use any advanced technologies or materials, faculty time required to conduct the audit and feedback in this study was estimated at 45 hours. In our opinion this estimate would classify our audit and feedback intervention as a low external cost and moderately‐high human cost intervention, which may represent a potential barrier to generalizability. On the other hand, we believe that even an audit of a small sample of DS done by a physician could provide valuable data for feedback and would involve less faculty time.

Our finding that audit and feedback sessions improved the completeness of DS among house‐staff is important for 2 reasons. First, we were able to demonstrate that focused feedback targeted to areas of particular importance to the transition of older adults changed subsequent behavior and resulted in improved documentation of these areas. Second, our study provides evidence of a programmatic approach to address the ACGME competency of practice‐based learning and improvement. We believe that our intervention can be reproduced by training programs across the country and are hopeful that such interventions will result in improved patient outcomes during critical care transitions such as hospital discharge.

Discharge summaries (DS) correlate with rates of rehospitalization1, 2 and adverse events after discharge.3 The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations acknowledges their importance and mandates that certain elements be included.4 Thus far, however, DS are not standardized across institutions and there is no expectation that they be available at postdischarge visits. There have been numerous attempts to improve the quality of DS by using more structured formats or computer generated summaries with positive results in term of comprehensiveness, clarity, and practitioner satisfaction58 but with persistence of serious errors and omissions.9

Postgraduate training is often the first opportunity for physicians to learn information transfer management skills. Unfortunately, DS are created by house staff who have minimal training in this area11 and feel like they have to learn by osmosis,12 resulting in poor quality DS and lack of availability at the point of care.1315

Previous research suggested that individualized feedback sessions for Internal Medicine residents improved the quality of certain aspects of their completed DS.10 We postulated that an audit and feedback educational intervention on DS for first year geriatric medicine fellows would also improve their quality. This technique involves chart or case review of clinical practice behaviors for a specific task followed by recommendation of new behaviors when applicable.16 Audit and feedback incorporates adult learning theory,1719 an essential part of continuous quality improvement that fits within the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency of practice based learning and improvement,20 as an educational activity.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a preintervention post intervention study at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center (MSMC) in New York City between July 1, 2006 and June 30, 2007. The study received an exemption from the MSMC Institutional Review Board. First year geriatric medicine fellows at MSMC were required to complete 2 months of inpatient service; the first during the first 6 months of the academic year and the second during the last 6 months of the year. Fellows dictated all DS, which were transcribed and routed for signature to the attending of record. Prior to our study, a discharge summary template consisting of 21 items was developed for clinical use. Template items, agreed upon by an expert internal panel of geriatricians and interprofessional faculty, were selected for their importance in assuring a safe transition of older adults from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

Participants

All 5 first‐year fellows at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at MSMC were invited to participate in the study.

Intervention

Audit #1

All available DS for each fellow's first month of inpatient service were audited for completeness of the 21 item discharge summary template by 1 author (AD). The 21 items were focused on 4 distinct periods of the hospitalization: admission, hospital course, discharge planning, and postdischarge care (Figure 1).

Content under each of the 21 items was classified as complete, partially complete, or absent. An item was considered complete if most information was present and appropriate medical terms were used, partially complete if information was unclear, and absent if no information was present for that area of the DS. To ensure investigator reliability, a random sample of 25% of each fellow's DS was scored by 2 additional investigators (RK and HF) and all disagreements were reviewed and resolved by consensus.

Feedback

Between December 2006 and January 2007, one‐on‐one formative feedback sessions were scheduled. The sessions were approximately 30 minutes long, confidential, performed by 1 of the authors (AD) and followed a written format. During these sessions, each fellow received the results of their discharge summary audit, each partially complete or absent item was discussed, and the importance of DS was emphasized.

Audit #2

All available DS for each fellow's second month of inpatient service were audited for completeness, using the same 21 item assessment tool and the same scoring system.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the impact of our audit and feedback intervention, we compared scores before and after formative feedback sessions, both overall and for the composite discharge summary scores for each of the 4 domains of care: admission, hospital course, discharge‐planning, and postdischarge care. Scores were dichotomized as being complete or partially complete or absent. We used generalized estimating equations to account for the clustering of DS within fellows. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2‐tailed and used a type I error rate of 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Five fellows participated, 4 of whom were women; 2 were in postgraduate year 4, 3 in year 5. A total of 158 DS were audited, 89 prefeedback and 79 postfeedback. Each fellow dictated an average of 17 DS during each inpatient month.

During Audit #1, the 21 item DS were complete among 71%, incomplete among 18%, absent among 11%. Admission items, hospital course items, and discharge planning items were complete among 70%, 78%, and 77% of DS respectively, but postdischarge items were complete among only 57%. Examining individual items, the lowest completion rates were found for test result follow‐up (42%), caregiver information (10%), and home services (64%), as well for assessment at admission and discharge of cognitive and mental status (56% and 53% respectively) and functional status (57% and 40%). Of note, all these items are of particular importance to geriatric care.

After receiving the audit and feedback intervention, fellows were more likely to complete all required discharge summary data when compared to prior‐to‐feedback (91% vs. 71%, P 0.001). Discharge summary completeness improved for all composite outcomes examining the four domains of care: admission (93% vs. 70%, P 0.001), hospital course (93% vs. 78%, P 0.001), discharge planning (93% vs. 77%, P 0.02), and postdischarge care (83% vs. 57%., P 0.001) (Table 1).

| Criteria | Preintervention | Postintervention | P Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Absent | Complete | Absent | ||

| |||||

| Admission composite (5 items) | 70 (3585) | 30 (1565) | 93 (79100) | 7 (021) | 0.001 |

| HPI | 79 (38100) | 21 (1563) | 100 | 0 | 0.001 |

| PMH | 94 (75100) | 5 (025) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 56 (1979) | 44 (2182) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 57 (2588) | 43 (1375) | 97 (89100) | 2 (010) | 0.001 |

| Physical exam | 63 (19100) | 37 (082) | 72 (0100) | 28 (5100) | 0.27 |

| Hospital course composite (3 items) | 78 (2593) | 22 (775) | 93 (76100) | 7 (023) | 0.001 |

| Hospital course | 84 (25100) | 15 (076) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Procedures and tests | 70 (690) | 30 (1094) | 90 (57100) | 10 (043) | 0.001 |

| Complications | 80 (4490) | 20 (556) | 90 (77100) | 10 (023) | 0.07 |

| Discharge planning composite (8 items) | 77 (4989) | 22 (1151) | 93 (64100) | 7 (036) | 0.02 |

| Primary diagnosis | 93 (75100) | 6 (026) | 100 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Secondary diagnosis | 82 (56100) | 18 (044) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Overall condition | 81 (38100) | 19 (062) | 86 (21100) | 14 (079) | 0.47 |

| Cognitive/mental status | 53 (1380) | 57 (2088) | 97 (93100) | 3 (07) | 0.001 |

| Functional status | 40 (1381) | 50 (1988) | 99 (93100) | 1 (07) | 0.001 |

| Diet | 89 (63100) | 12 (538) | 81 (0100) | 19 (0100) | 0.25 |

| Activity | 89 (69100) | 11 (032) | 82 (0100) | 18 (0100) | 0.49 |

| Medications | 83 (50100) | 17 (050) | 100 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Postdischarge care composite (5 items) | 57 (4183) | 43 (1759) | 83 (6998) | 18 (231) | 0.001 |

| F/U results | 42 (1190) | 58 (1089) | 81 (50100) | 20 (050) | 0.02 |

| Discharge location | 92 (88100) | 8 (012) | 100 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Caregiver info | 10 (025) | 89 (75100) | 48 (795) | 52 (584) | 0.001 |

| Home services | 64 (32100) | 35 (068) | 87 (7195) | 12 (029) | 0.001 |

| F/U appointments | 78 (33100) | 23 (067) | 96 (86100) | 4 (014) | 0.001 |

| Overall composite (21 items) | 71 (4287) | 29 (1358) | 91 (7399) | 9 (227) | 0.001 |

Discussion

Our study found that audit and feedback sessions significantly improved the completeness of DS dictated by geriatric medicine fellows at 1 academic medical center. Before feedback, completeness was high in most traditional areas of the DS including admission data, hospital course, and discharge planning, but was low in other areas critical for safe transitions of older adults such as postdischarge care, test follow‐up, caregiver information, and cognitive and functional status changes. These findings were surprising, as using a template should render a completion rate close to 100%. Notably, during feedback sessions, fellows suggested low completion rates were due to lack of awareness regarding the importance of completing all 21 items of the template and missing documentation in patient medical records.

Feedback sessions dramatically improved overall completeness of subsequent DS and in most of areas of specific importance for geriatric care, although we remain uncertain why all areas did not show improvement (for example, caregiver information completion remained low). One possible explanation is the lack of accurate documentation for all necessary items in the hospital medical record. Moreover, we did not observe completion improvement for other items, ie, diet and activity. Overall, we believe that drawing attention to areas of particular importance to geriatric care transitions and providing learners with individual reports on their performance increased their awareness and motivated changes to their practice, improving discharge summary completion.

Our study has limitations. This study was a pilot intervention without a control group, because of time and budgetary constraints. Also, we were unable to assess for sustainability because the fellows studied for this project graduated after the second audit. Third, we studied discharge summary completion; further research should focus on accuracy of discharge summary content. Finally, while we did not use any advanced technologies or materials, faculty time required to conduct the audit and feedback in this study was estimated at 45 hours. In our opinion this estimate would classify our audit and feedback intervention as a low external cost and moderately‐high human cost intervention, which may represent a potential barrier to generalizability. On the other hand, we believe that even an audit of a small sample of DS done by a physician could provide valuable data for feedback and would involve less faculty time.

Our finding that audit and feedback sessions improved the completeness of DS among house‐staff is important for 2 reasons. First, we were able to demonstrate that focused feedback targeted to areas of particular importance to the transition of older adults changed subsequent behavior and resulted in improved documentation of these areas. Second, our study provides evidence of a programmatic approach to address the ACGME competency of practice‐based learning and improvement. We believe that our intervention can be reproduced by training programs across the country and are hopeful that such interventions will result in improved patient outcomes during critical care transitions such as hospital discharge.

- ,Quality assessment of a discharge summary system.CMAJ.1995;152:1437–1442.

- ,,Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries.Intern Med J.2006;36:221–225.

- ,,,,The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org./. The Joint Commission Requirements/Hospitals/Record of Care/Patient safety. Accessed July2010.

- ,,,,General practitioners' attitudes to computer‐generated surgical discharge letters.Med J Aust.1992;157(6):380–382.

- ,,,Do primary care physicians prefer dictated or computer‐generated discharge summaries?Am J Dis Child.1993;147(9):986–988.

- ,,,,,Evaluation of a computer‐generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes.Br J Gen Pract.1998;48(429):1163–1164.

- ,,, et al.Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic dischanrge summary,J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):219–225.

- ,Communication with general practitioners after accident and emergency attendance: computer generated letters are often deficient.Emerg Med J.2003;20(3):256–257.

- ,,Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries.Int J Med Inform.2008;77:613–620.

- ,,,,,Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program.Acad Med.2006;81:S5–S8.

- ,,Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries.BMJ.1996;312:350.

- ,,,,,Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,,Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists.Dis Mon.2002;48:218–229.

- ,,Improving the continuity of care following discharge of patients hospitalized with heart failure: is the discharge summary adequate?Can J Cardiol.2003;19:365–370.

- Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews.Int J Technol Assess Health Care.2005;21:380–385.

- ,,, et al.Impact of feedback and didactic sessions on the reporting behavior of upper endoscopic findings by physicians and nurses.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2007;5:326–330.

- ,,Prospective assessment of the impact of feedback on colonoscopy performance.Aliment Pharmacol Ther.2006;24:313–318.

- ,,, et al.Inpatient care to community care: improving clinical handover in the private mental health setting.Med J Aust.2009;190(11 Suppl):S144–S149.

- Available at: http://www.Acgme.org, Record of care, Treatment, and Serives, Standard RC.02.04.01. Accessed July2010.

- ,Quality assessment of a discharge summary system.CMAJ.1995;152:1437–1442.

- ,,Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries.Intern Med J.2006;36:221–225.

- ,,,,The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org./. The Joint Commission Requirements/Hospitals/Record of Care/Patient safety. Accessed July2010.

- ,,,,General practitioners' attitudes to computer‐generated surgical discharge letters.Med J Aust.1992;157(6):380–382.

- ,,,Do primary care physicians prefer dictated or computer‐generated discharge summaries?Am J Dis Child.1993;147(9):986–988.

- ,,,,,Evaluation of a computer‐generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes.Br J Gen Pract.1998;48(429):1163–1164.

- ,,, et al.Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic dischanrge summary,J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):219–225.

- ,Communication with general practitioners after accident and emergency attendance: computer generated letters are often deficient.Emerg Med J.2003;20(3):256–257.

- ,,Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries.Int J Med Inform.2008;77:613–620.

- ,,,,,Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program.Acad Med.2006;81:S5–S8.

- ,,Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries.BMJ.1996;312:350.

- ,,,,,Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,,Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists.Dis Mon.2002;48:218–229.

- ,,Improving the continuity of care following discharge of patients hospitalized with heart failure: is the discharge summary adequate?Can J Cardiol.2003;19:365–370.

- Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews.Int J Technol Assess Health Care.2005;21:380–385.

- ,,, et al.Impact of feedback and didactic sessions on the reporting behavior of upper endoscopic findings by physicians and nurses.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2007;5:326–330.

- ,,Prospective assessment of the impact of feedback on colonoscopy performance.Aliment Pharmacol Ther.2006;24:313–318.

- ,,, et al.Inpatient care to community care: improving clinical handover in the private mental health setting.Med J Aust.2009;190(11 Suppl):S144–S149.

- Available at: http://www.Acgme.org, Record of care, Treatment, and Serives, Standard RC.02.04.01. Accessed July2010.