User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Destructive Facial Granuloma Following Self-Treatment With Vitamin E Oil and an At-Home Microneedling Device

Destructive Facial Granuloma Following Self-Treatment With Vitamin E Oil and an At-Home Microneedling Device

Topical application or injection of cosmeceuticals in conjunction with procedures such as facial microneedling (MN) has been associated with local and systemic complications.1

Although at-home options may be more accessible and affordable for patients, they also increase the risk for improper use and subsequent infection. Additionally, the use of cosmeceuticals such as vitamin E oil in conjunction with MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can lead to further complications. We report the case of a 44-year-old woman who developed a necrotic ulcer on the chin following self-treatment with vitamin E oil and an at-home MN device. While MN has been reported to be relatively safe when performed by board-certified dermatologists, clinicians should be vigilant in correlating clinical history and recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for timely diagnosis and treatment of unusual lesions on the face.

Case Report

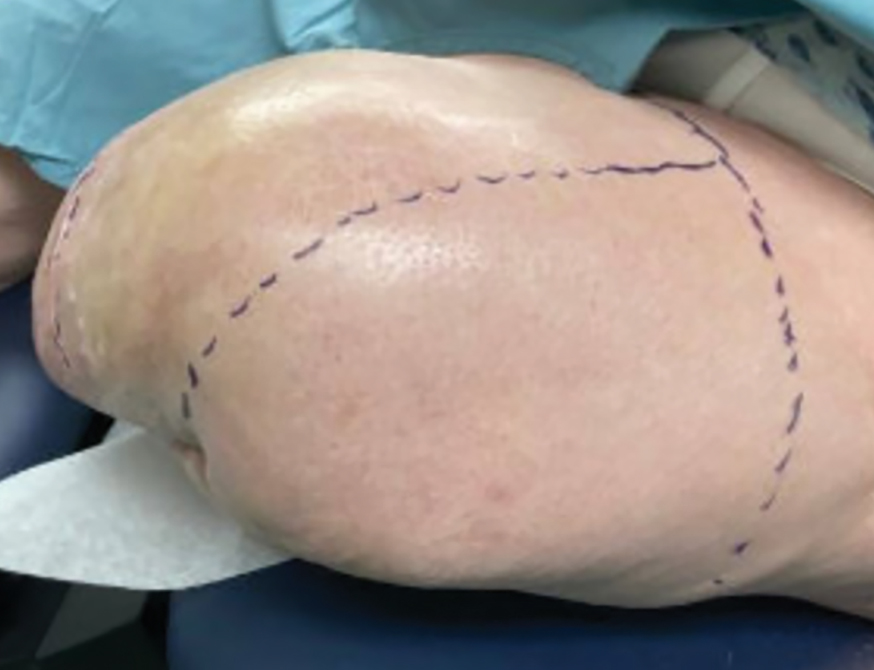

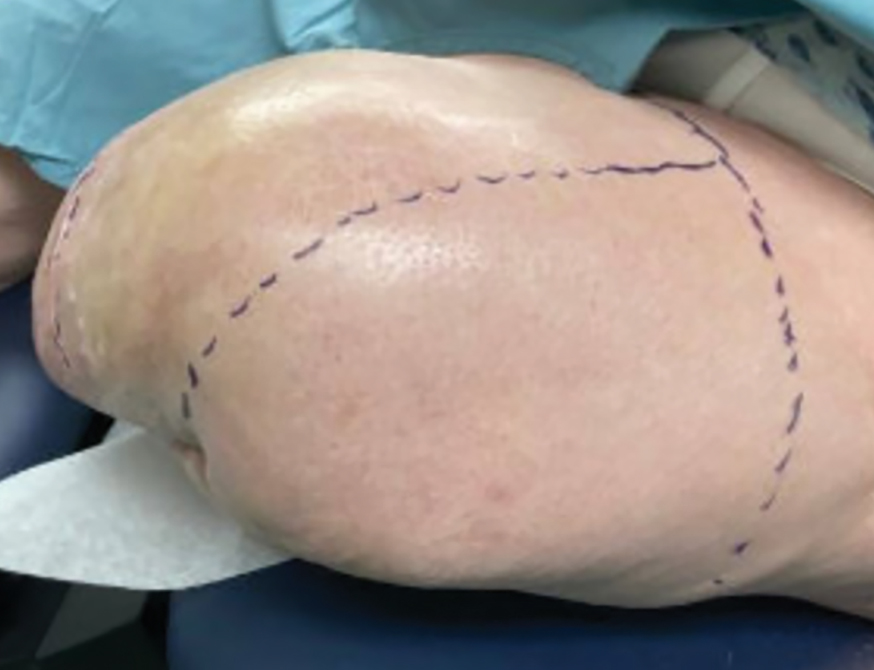

A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a progressively enlarging, necrotic, ulcerative lesion on the midline chin of 4 months’ duration. The patient reported that the lesion started as redness that developed into a painful oozing ulcer following application of vitamin E oil in conjunction with an at-home MN device (Figure 1). She purchased the vitamin E oil and MN device online and performed the procedure herself, applying the vitamin E oil to her whole face before, during, and after using the MN device, which contained 0.25-mm titanium needles. She denied undergoing any other recent cosmetic procedures.

The lesion initially was treated by the patient’s primary care physician with oral doxycycline for 6 weeks, followed by oral cephalexin and clindamycin for 2 weeks. Although the redness stabilized, the lesion continued to enlarge, which prompted her initial visit to our hospital 1 month after seeing her primary care physician. During this visit, the patient was given penicillin, and the ulcer was debrided and biopsied; however, no clinical improvement was seen.

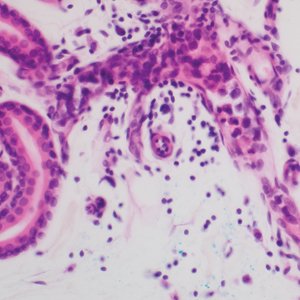

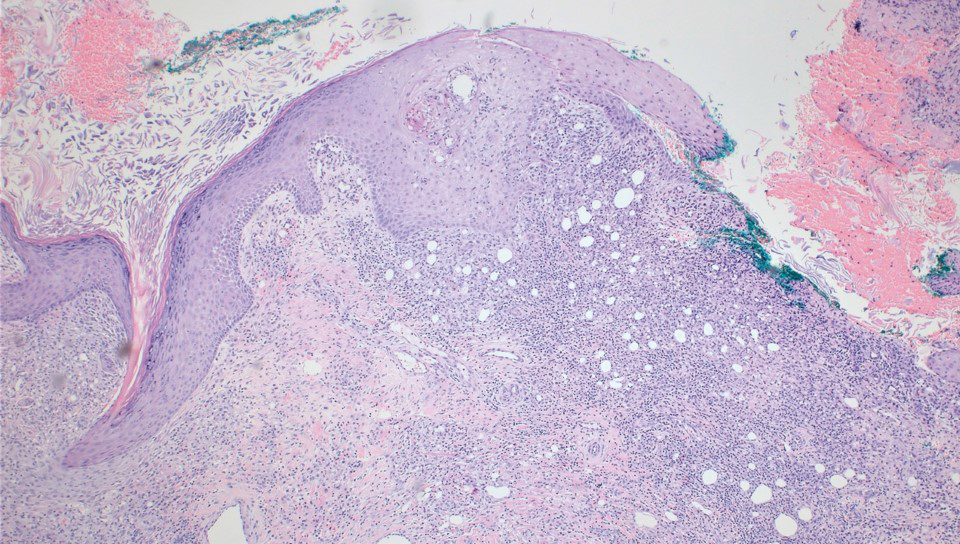

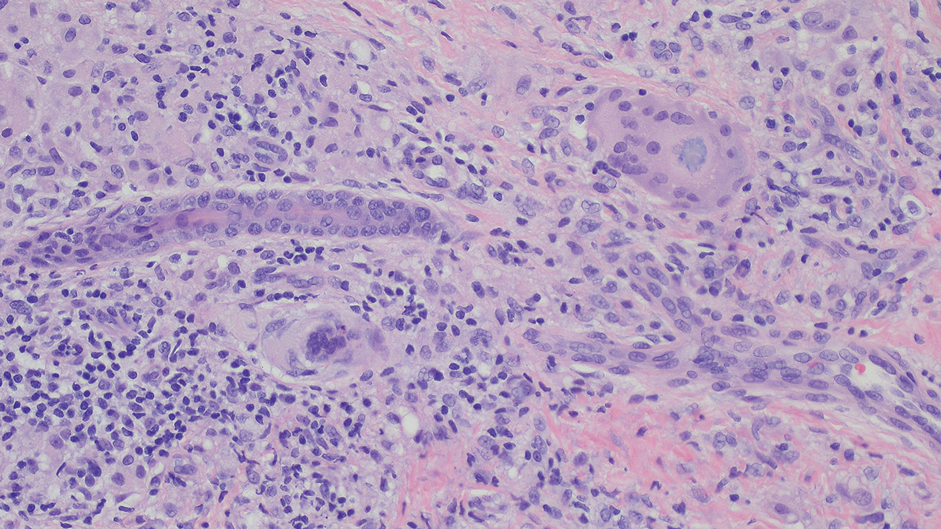

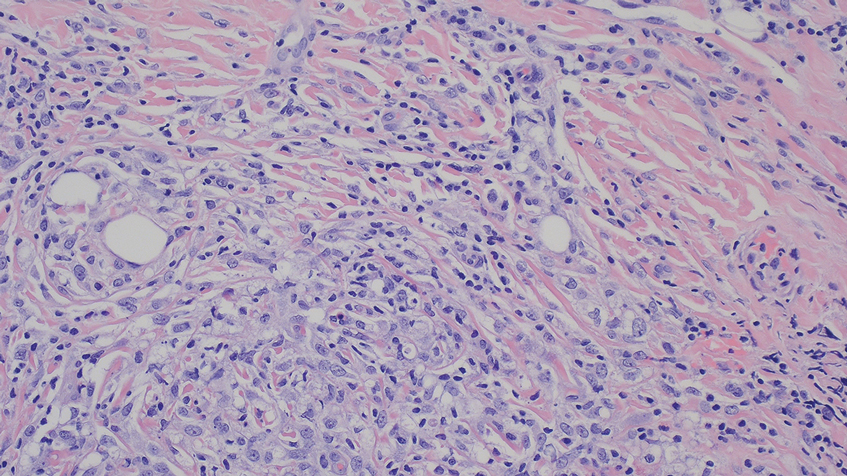

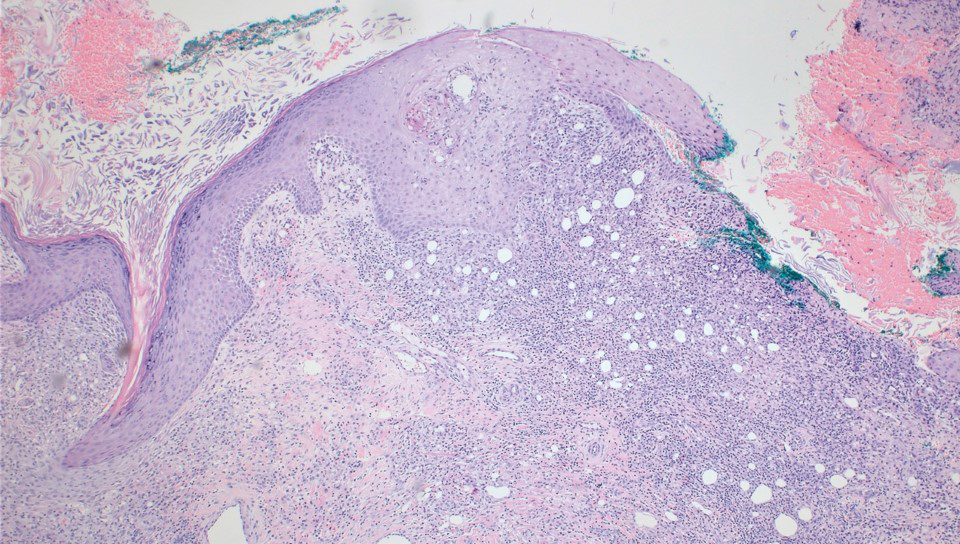

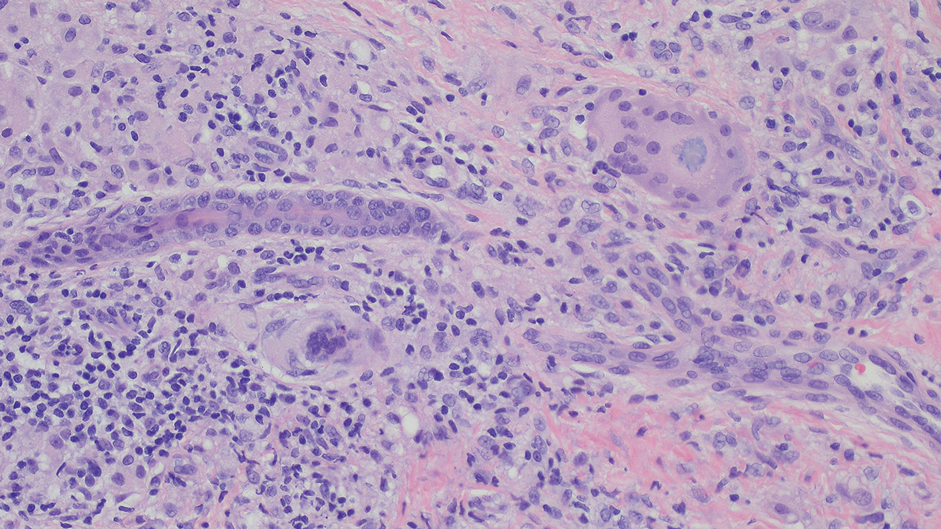

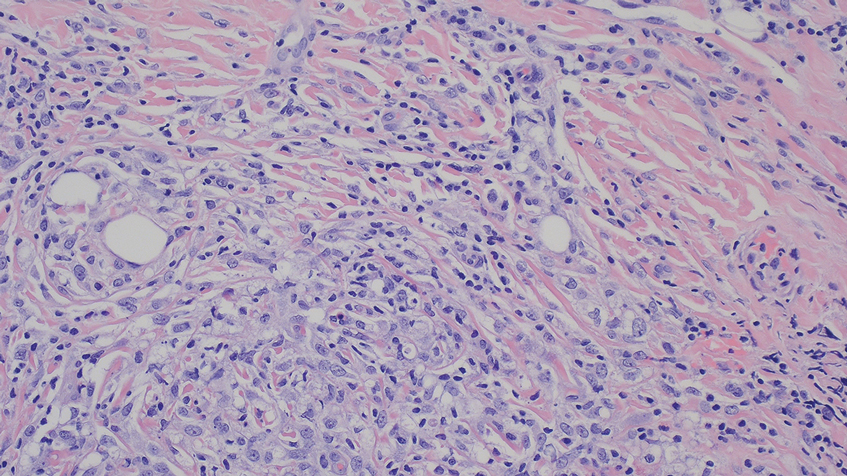

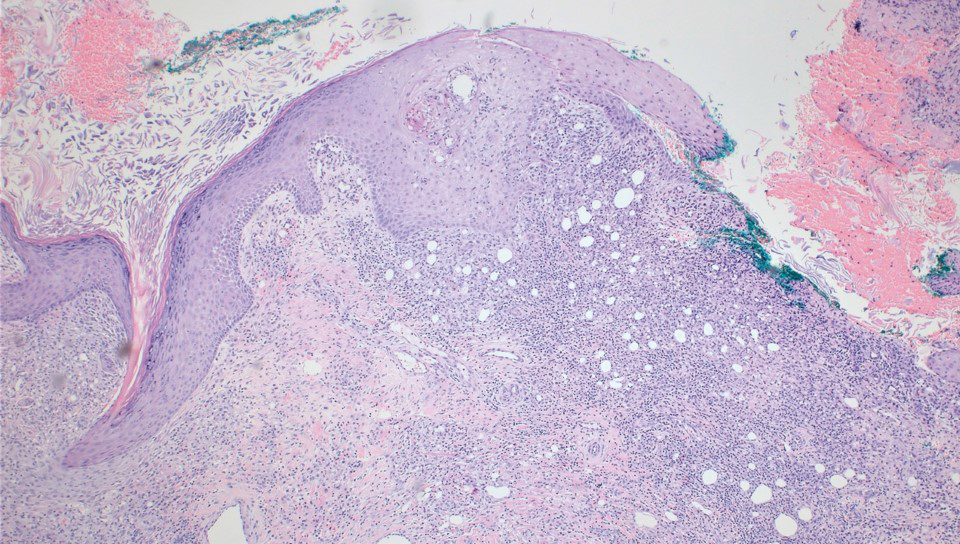

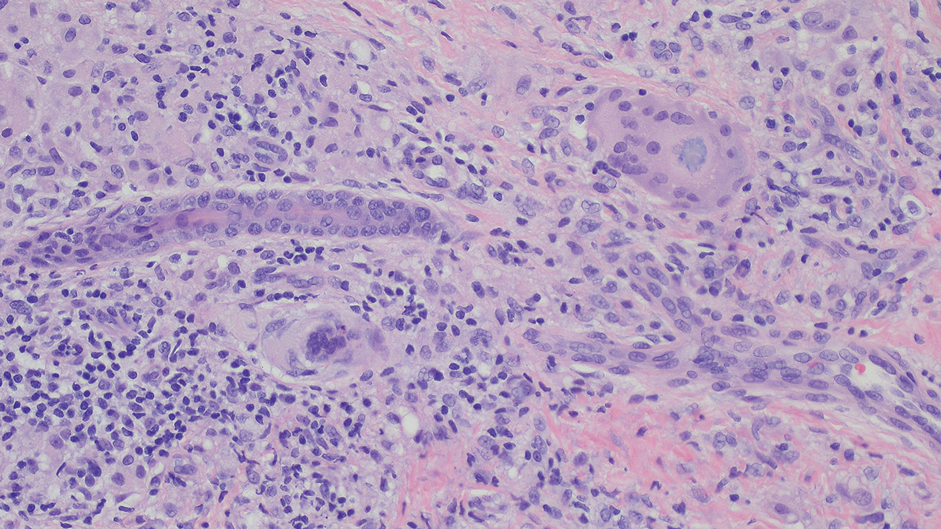

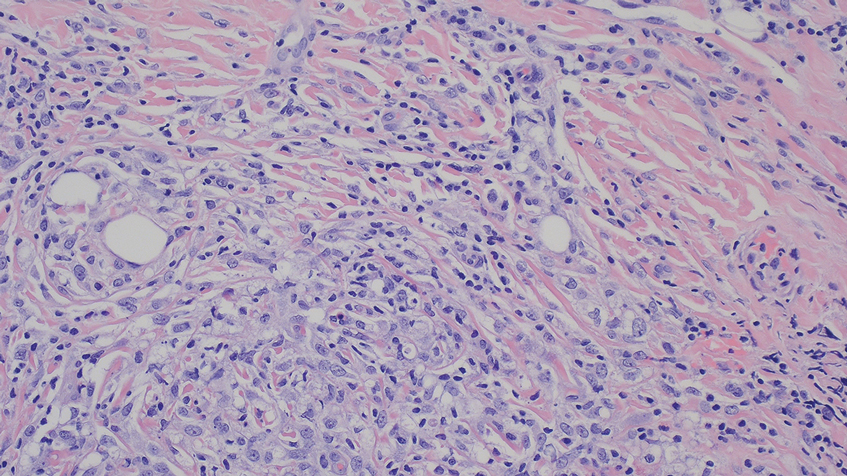

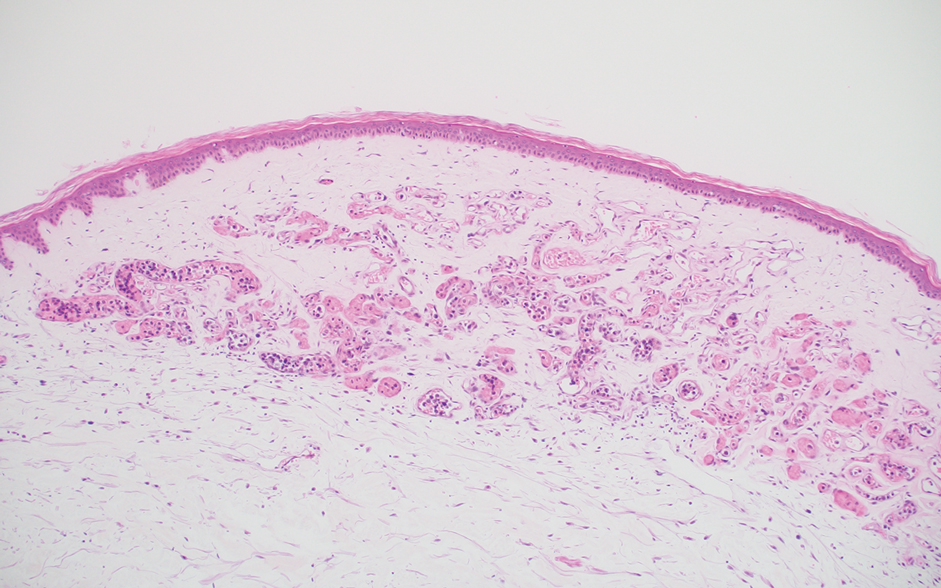

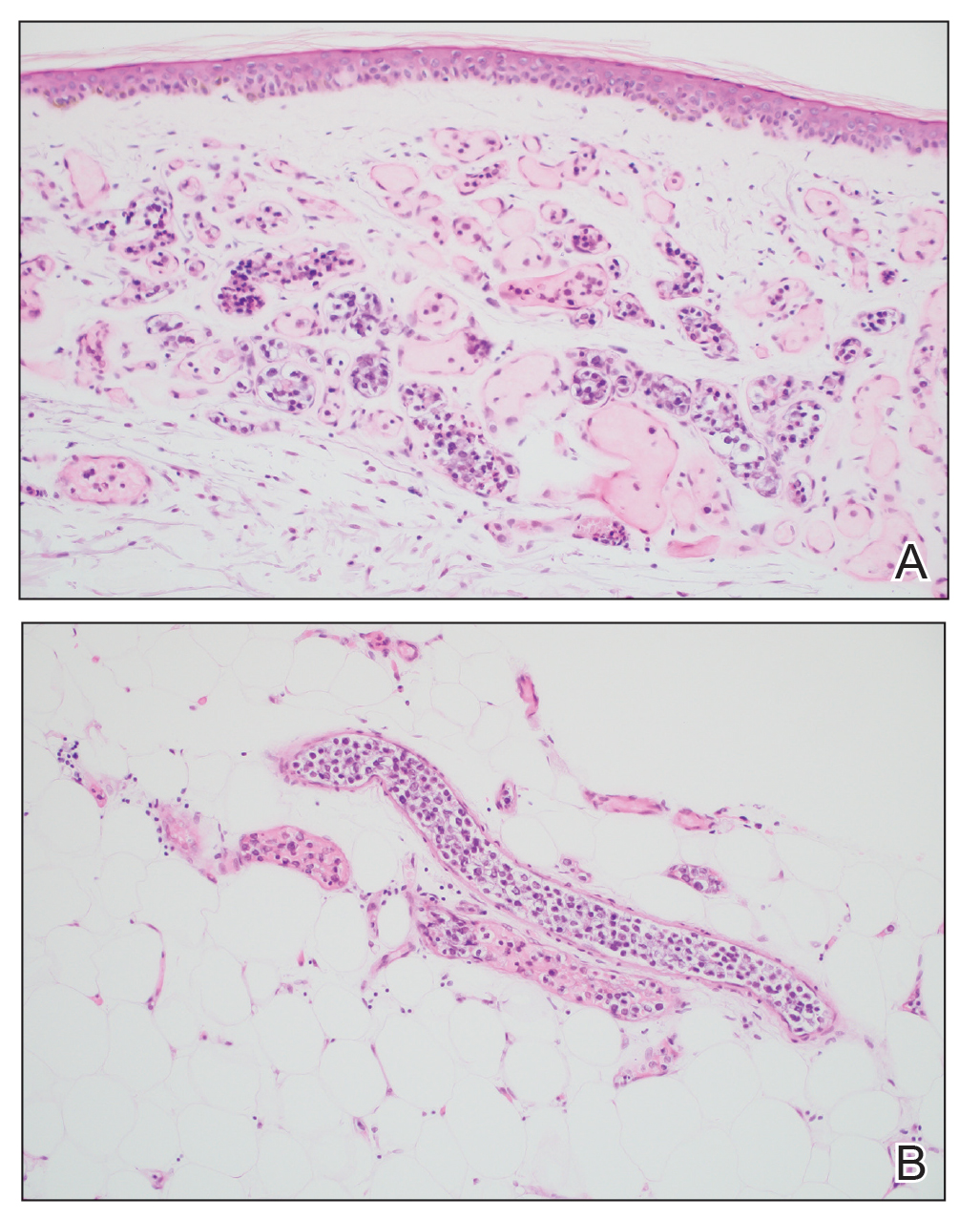

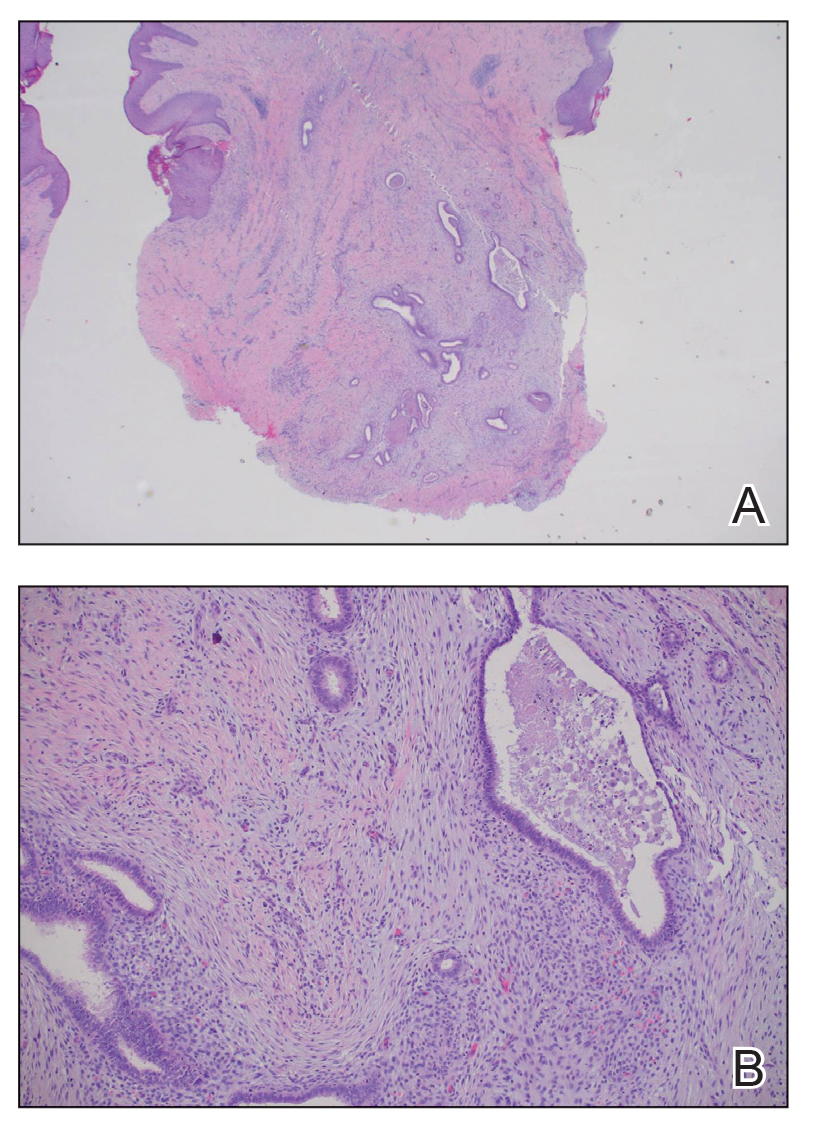

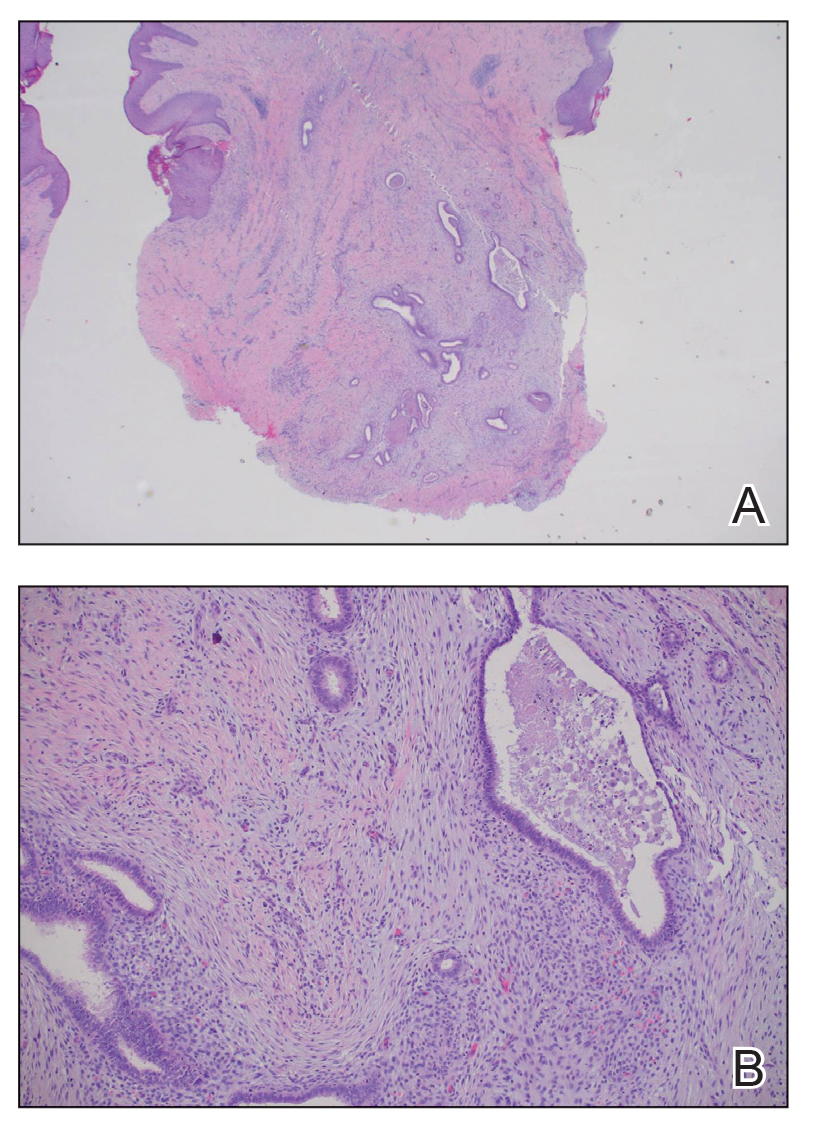

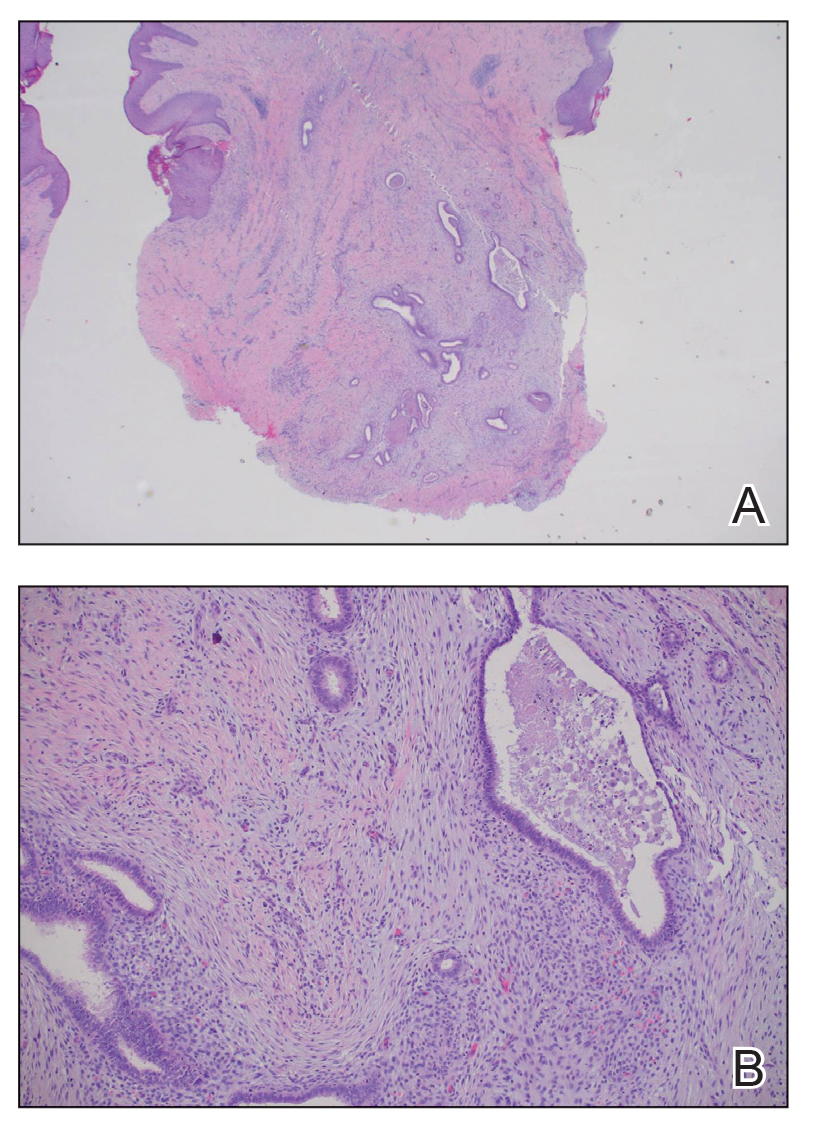

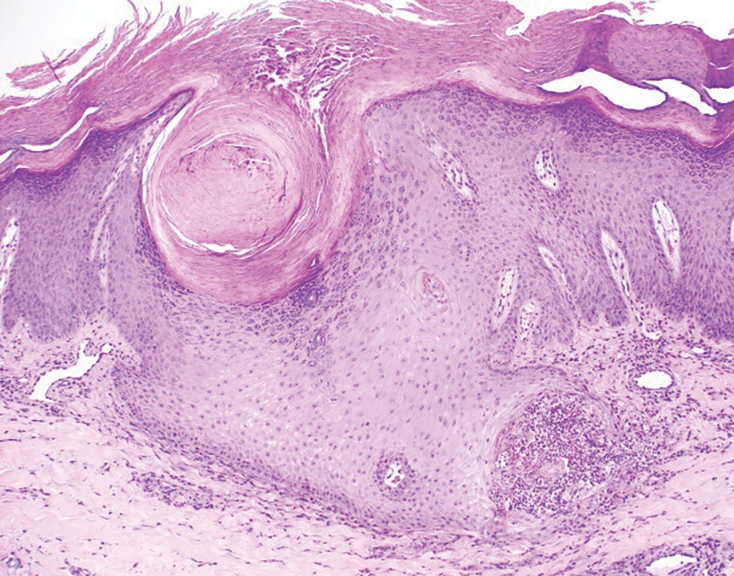

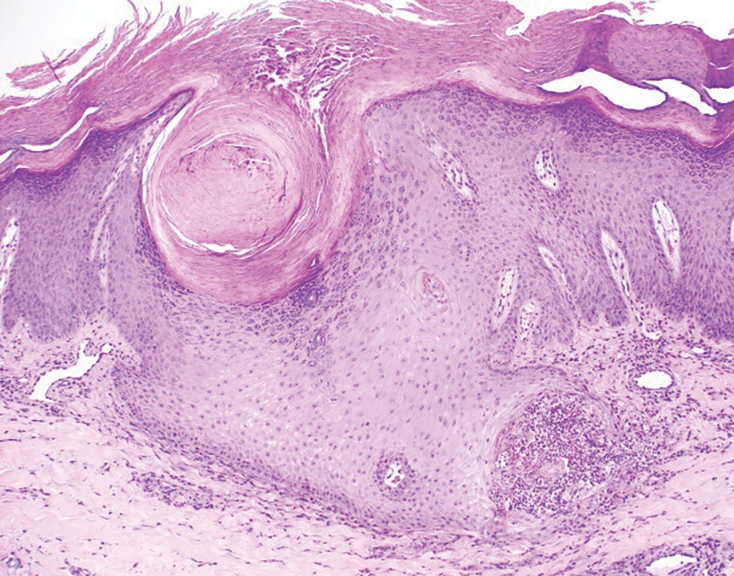

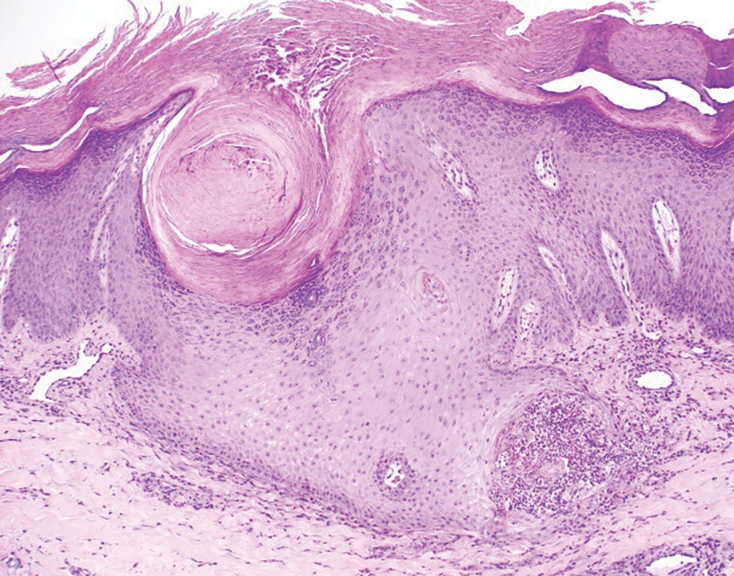

A biopsy during her initial emergency department visit and a repeat biopsy after 1 month showed similar findings of diffuse lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammation in the dermis (Figure 2) with poorly defined granulomas and multinucleated giant cells containing nonpolarizable exogenous material (Figure 3). Similar detached exogenous materials also were identified adjacent to the tissue. Diffuse re-epithelialization was seen, featuring pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in association with the inflammatory process and granulation tissue (Figures 3 and 4). A higher-power view of the dermis showed foci of sclerosing lipogranuloma (Figure 4). Periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott methenamine silver, acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and Wright-Giemsa stains all were negative for microorganisms, and pancytokeratin staining was negative for carcinoma. These findings supported the diagnosis of a foreign body granulomatous reaction to an exogenous material—in this case, the vitamin E oil. Subsequent treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injection over 18 months resulted in progressive and drastic improvement of the lesion (Figure 5). A scar excision was performed, which further improved the lesion’s cosmetic appearance.

Comment

Application of various topical cosmeceuticals before, during, or after MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can introduce particles into the dermis, resulting in local or systemic hypersensitivity reactions. The associated adverse events can be divided into 2 main categories: adverse reactions related to the topical product or to the materials of the MN device itself.

A study showed that topical application of vitamin E oil to wounds on the skin does not improve the cosmetic appearance of scars.3 Instead, it is associated with a high incidence of contact dermatitis. A similar case of vitamin E injection, although without the concurrent use of an MN device, complicated by a facial lipogranuloma has been described.4 Sclerodermoid reaction, subcutaneous nodules, persistent edema, and ulceration at the site of vitamin E injection also have been described following the injection.5,6 Because vitamin E is a lipid-soluble vitamin, its absorption in the human body is dependent on the presence of lipid or oil-like substances. The reactions mentioned above are associated with the vitamin E oil, which acts as a helper vehicle for lipid-soluble vitamins to be absorbed.7 Other ingredients in topical vitamin E oil include a combination of D-alpha-tocopherol, D-alpha-tocopheryl acetate, D-alpha-tocopheryl succinate, or mixed tocopherols.8 These ester conjugate forms of vitamin E also may play a role in its immunogenic properties and

Hyaluronic acid is a relatively safe and commonly used topical treatment that acts as a lubricant during MN procedures to help the needles glide across the skin and prevent dragging. It also can be applied after the procedure for hydration purposes. Other common alternatives include peptides, ceramides, and epidermal growth factors. Topical products to avoid before, during, and 48 hours after undergoing MN include retinoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, exfoliants, serums that contain acids (eg, alpha hydroxy acids, beta hydroxy acids, glycolic acid, and lactic acid), serums that contain fragrance, and oil-based serums because they are associated with similar adverse effects.8-10 A granulomatous reaction after an MN procedure also has been reported with the use of vitamin C serum.11

The

Most MN devices are made of nickel and various other metals. Cases of contact dermatitis and delayed-type hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction with systemic symptoms have been reported after MN procedures due to the material of the MN device.1,13,14

Conclusion

Microneedling is a minimally invasive procedure that causes nominal damage to the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis, stimulating a wound-healing cascade for collagen production.15,16 Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, MN performed at dermatology offices sometimes can be used in conjunction with topical products to enhance their absorption; however, while vitamin E is known for its antioxidant properties and potential skin benefits, the lipid substance acting as the vehicle is not absorbable by the skin and may cause a granulomatous reaction as the body attempts to encapsulate and digest the foreign substance.10,17 Although rarely reported, the use of topical vitamins with MN—through intradermal injection or combined with MN—can be associated with severe complications, including local, sometimes systemic, and life-threatening complications. Clinicians should be vigilant in order to correlate clinical background and history of recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for prompt diagnosis and timely treatment.

- Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong JW, Duffy KL, et al. Facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systemic hypersensitivity associated with microneedle therapy for skin rejuvenation. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:68-72. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6955

- Microneedling market. The Brainy Insights. Published January, 2023. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://www.thebrainyinsights.com/report/microneedling-market-13269

- Baumann LS, Spencer J. The effects of topical vitamin E on the cosmetic appearance of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:311-315. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08223.x

- Abtahi-Naeini B, Rastegarnasab F, Saffaei A. Liquid vitamin E injection for cosmetic facial rejuvenation: a disaster report of lipogranuloma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:5549-5554. doi:10.1111/jocd.15294

- Kamouna B, Litov I, Bardarov E, et al. Granuloma formation after oil-soluble vitamin D injection for lip augmentation - case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1435-1436. doi:10.1111/jdv.13277

- Kamouna B, Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, et al. Complications of injected vitamin E as a filler for lip augmentation: case series and therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:94-97. doi:10.1111/dth.12203

- Kosari P, Alikhan A, Sockolov M, et al. Vitamin E and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2010;21:148-153

- Thiele JJ, Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage S. Vitamin E in human skin: organ-specific physiology and considerations for its use in dermatology. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:646-667. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.06.001

- Spataro EA, Dierks K, Carniol PJ. Microneedling-associated procedures to enhance facial rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2022;30:389-397. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2022.03.012

- Setterfield L. The Concise Guide to Dermal Needling. Acacia Dermacare; 2017.

- Handal M, Kyriakides K, Cohen J, et al. Sarcoidal granulomatous reaction to microneedling with vitamin C serum. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;36:67-69. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.04.015

- Microneedling devices. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published 2020. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/microneedling-devices#risks

- Gowda A, Healey B, Ezaldein H, et al. A systematic review examining the potential adverse effects of microneedling. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:45-54.

- Hou A, Cohen B, Haimovic A, et al. Microneedling: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:321-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000924

- Hogan S, Velez MW, Ibrahim O. Microneedling: a new approach for treating textural abnormalities and scars. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:155-163. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.042

- Schmitt L, Marquardt Y, Amann P, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of microneedling therapy in a human three-dimensional skin model. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204318

- Friedmann DP, Mehta E, Verma KK, et al. Granulomatous reactions from microneedling: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2025;51:263-266. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000004450

Topical application or injection of cosmeceuticals in conjunction with procedures such as facial microneedling (MN) has been associated with local and systemic complications.1

Although at-home options may be more accessible and affordable for patients, they also increase the risk for improper use and subsequent infection. Additionally, the use of cosmeceuticals such as vitamin E oil in conjunction with MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can lead to further complications. We report the case of a 44-year-old woman who developed a necrotic ulcer on the chin following self-treatment with vitamin E oil and an at-home MN device. While MN has been reported to be relatively safe when performed by board-certified dermatologists, clinicians should be vigilant in correlating clinical history and recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for timely diagnosis and treatment of unusual lesions on the face.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a progressively enlarging, necrotic, ulcerative lesion on the midline chin of 4 months’ duration. The patient reported that the lesion started as redness that developed into a painful oozing ulcer following application of vitamin E oil in conjunction with an at-home MN device (Figure 1). She purchased the vitamin E oil and MN device online and performed the procedure herself, applying the vitamin E oil to her whole face before, during, and after using the MN device, which contained 0.25-mm titanium needles. She denied undergoing any other recent cosmetic procedures.

The lesion initially was treated by the patient’s primary care physician with oral doxycycline for 6 weeks, followed by oral cephalexin and clindamycin for 2 weeks. Although the redness stabilized, the lesion continued to enlarge, which prompted her initial visit to our hospital 1 month after seeing her primary care physician. During this visit, the patient was given penicillin, and the ulcer was debrided and biopsied; however, no clinical improvement was seen.

A biopsy during her initial emergency department visit and a repeat biopsy after 1 month showed similar findings of diffuse lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammation in the dermis (Figure 2) with poorly defined granulomas and multinucleated giant cells containing nonpolarizable exogenous material (Figure 3). Similar detached exogenous materials also were identified adjacent to the tissue. Diffuse re-epithelialization was seen, featuring pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in association with the inflammatory process and granulation tissue (Figures 3 and 4). A higher-power view of the dermis showed foci of sclerosing lipogranuloma (Figure 4). Periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott methenamine silver, acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and Wright-Giemsa stains all were negative for microorganisms, and pancytokeratin staining was negative for carcinoma. These findings supported the diagnosis of a foreign body granulomatous reaction to an exogenous material—in this case, the vitamin E oil. Subsequent treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injection over 18 months resulted in progressive and drastic improvement of the lesion (Figure 5). A scar excision was performed, which further improved the lesion’s cosmetic appearance.

Comment

Application of various topical cosmeceuticals before, during, or after MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can introduce particles into the dermis, resulting in local or systemic hypersensitivity reactions. The associated adverse events can be divided into 2 main categories: adverse reactions related to the topical product or to the materials of the MN device itself.

A study showed that topical application of vitamin E oil to wounds on the skin does not improve the cosmetic appearance of scars.3 Instead, it is associated with a high incidence of contact dermatitis. A similar case of vitamin E injection, although without the concurrent use of an MN device, complicated by a facial lipogranuloma has been described.4 Sclerodermoid reaction, subcutaneous nodules, persistent edema, and ulceration at the site of vitamin E injection also have been described following the injection.5,6 Because vitamin E is a lipid-soluble vitamin, its absorption in the human body is dependent on the presence of lipid or oil-like substances. The reactions mentioned above are associated with the vitamin E oil, which acts as a helper vehicle for lipid-soluble vitamins to be absorbed.7 Other ingredients in topical vitamin E oil include a combination of D-alpha-tocopherol, D-alpha-tocopheryl acetate, D-alpha-tocopheryl succinate, or mixed tocopherols.8 These ester conjugate forms of vitamin E also may play a role in its immunogenic properties and

Hyaluronic acid is a relatively safe and commonly used topical treatment that acts as a lubricant during MN procedures to help the needles glide across the skin and prevent dragging. It also can be applied after the procedure for hydration purposes. Other common alternatives include peptides, ceramides, and epidermal growth factors. Topical products to avoid before, during, and 48 hours after undergoing MN include retinoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, exfoliants, serums that contain acids (eg, alpha hydroxy acids, beta hydroxy acids, glycolic acid, and lactic acid), serums that contain fragrance, and oil-based serums because they are associated with similar adverse effects.8-10 A granulomatous reaction after an MN procedure also has been reported with the use of vitamin C serum.11

The

Most MN devices are made of nickel and various other metals. Cases of contact dermatitis and delayed-type hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction with systemic symptoms have been reported after MN procedures due to the material of the MN device.1,13,14

Conclusion

Microneedling is a minimally invasive procedure that causes nominal damage to the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis, stimulating a wound-healing cascade for collagen production.15,16 Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, MN performed at dermatology offices sometimes can be used in conjunction with topical products to enhance their absorption; however, while vitamin E is known for its antioxidant properties and potential skin benefits, the lipid substance acting as the vehicle is not absorbable by the skin and may cause a granulomatous reaction as the body attempts to encapsulate and digest the foreign substance.10,17 Although rarely reported, the use of topical vitamins with MN—through intradermal injection or combined with MN—can be associated with severe complications, including local, sometimes systemic, and life-threatening complications. Clinicians should be vigilant in order to correlate clinical background and history of recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for prompt diagnosis and timely treatment.

Topical application or injection of cosmeceuticals in conjunction with procedures such as facial microneedling (MN) has been associated with local and systemic complications.1

Although at-home options may be more accessible and affordable for patients, they also increase the risk for improper use and subsequent infection. Additionally, the use of cosmeceuticals such as vitamin E oil in conjunction with MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can lead to further complications. We report the case of a 44-year-old woman who developed a necrotic ulcer on the chin following self-treatment with vitamin E oil and an at-home MN device. While MN has been reported to be relatively safe when performed by board-certified dermatologists, clinicians should be vigilant in correlating clinical history and recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for timely diagnosis and treatment of unusual lesions on the face.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a progressively enlarging, necrotic, ulcerative lesion on the midline chin of 4 months’ duration. The patient reported that the lesion started as redness that developed into a painful oozing ulcer following application of vitamin E oil in conjunction with an at-home MN device (Figure 1). She purchased the vitamin E oil and MN device online and performed the procedure herself, applying the vitamin E oil to her whole face before, during, and after using the MN device, which contained 0.25-mm titanium needles. She denied undergoing any other recent cosmetic procedures.

The lesion initially was treated by the patient’s primary care physician with oral doxycycline for 6 weeks, followed by oral cephalexin and clindamycin for 2 weeks. Although the redness stabilized, the lesion continued to enlarge, which prompted her initial visit to our hospital 1 month after seeing her primary care physician. During this visit, the patient was given penicillin, and the ulcer was debrided and biopsied; however, no clinical improvement was seen.

A biopsy during her initial emergency department visit and a repeat biopsy after 1 month showed similar findings of diffuse lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic inflammation in the dermis (Figure 2) with poorly defined granulomas and multinucleated giant cells containing nonpolarizable exogenous material (Figure 3). Similar detached exogenous materials also were identified adjacent to the tissue. Diffuse re-epithelialization was seen, featuring pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in association with the inflammatory process and granulation tissue (Figures 3 and 4). A higher-power view of the dermis showed foci of sclerosing lipogranuloma (Figure 4). Periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott methenamine silver, acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and Wright-Giemsa stains all were negative for microorganisms, and pancytokeratin staining was negative for carcinoma. These findings supported the diagnosis of a foreign body granulomatous reaction to an exogenous material—in this case, the vitamin E oil. Subsequent treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injection over 18 months resulted in progressive and drastic improvement of the lesion (Figure 5). A scar excision was performed, which further improved the lesion’s cosmetic appearance.

Comment

Application of various topical cosmeceuticals before, during, or after MN to enhance the effects of the procedure can introduce particles into the dermis, resulting in local or systemic hypersensitivity reactions. The associated adverse events can be divided into 2 main categories: adverse reactions related to the topical product or to the materials of the MN device itself.

A study showed that topical application of vitamin E oil to wounds on the skin does not improve the cosmetic appearance of scars.3 Instead, it is associated with a high incidence of contact dermatitis. A similar case of vitamin E injection, although without the concurrent use of an MN device, complicated by a facial lipogranuloma has been described.4 Sclerodermoid reaction, subcutaneous nodules, persistent edema, and ulceration at the site of vitamin E injection also have been described following the injection.5,6 Because vitamin E is a lipid-soluble vitamin, its absorption in the human body is dependent on the presence of lipid or oil-like substances. The reactions mentioned above are associated with the vitamin E oil, which acts as a helper vehicle for lipid-soluble vitamins to be absorbed.7 Other ingredients in topical vitamin E oil include a combination of D-alpha-tocopherol, D-alpha-tocopheryl acetate, D-alpha-tocopheryl succinate, or mixed tocopherols.8 These ester conjugate forms of vitamin E also may play a role in its immunogenic properties and

Hyaluronic acid is a relatively safe and commonly used topical treatment that acts as a lubricant during MN procedures to help the needles glide across the skin and prevent dragging. It also can be applied after the procedure for hydration purposes. Other common alternatives include peptides, ceramides, and epidermal growth factors. Topical products to avoid before, during, and 48 hours after undergoing MN include retinoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, exfoliants, serums that contain acids (eg, alpha hydroxy acids, beta hydroxy acids, glycolic acid, and lactic acid), serums that contain fragrance, and oil-based serums because they are associated with similar adverse effects.8-10 A granulomatous reaction after an MN procedure also has been reported with the use of vitamin C serum.11

The

Most MN devices are made of nickel and various other metals. Cases of contact dermatitis and delayed-type hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction with systemic symptoms have been reported after MN procedures due to the material of the MN device.1,13,14

Conclusion

Microneedling is a minimally invasive procedure that causes nominal damage to the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis, stimulating a wound-healing cascade for collagen production.15,16 Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, MN performed at dermatology offices sometimes can be used in conjunction with topical products to enhance their absorption; however, while vitamin E is known for its antioxidant properties and potential skin benefits, the lipid substance acting as the vehicle is not absorbable by the skin and may cause a granulomatous reaction as the body attempts to encapsulate and digest the foreign substance.10,17 Although rarely reported, the use of topical vitamins with MN—through intradermal injection or combined with MN—can be associated with severe complications, including local, sometimes systemic, and life-threatening complications. Clinicians should be vigilant in order to correlate clinical background and history of recent cosmetic procedures with the histologic findings for prompt diagnosis and timely treatment.

- Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong JW, Duffy KL, et al. Facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systemic hypersensitivity associated with microneedle therapy for skin rejuvenation. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:68-72. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6955

- Microneedling market. The Brainy Insights. Published January, 2023. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://www.thebrainyinsights.com/report/microneedling-market-13269

- Baumann LS, Spencer J. The effects of topical vitamin E on the cosmetic appearance of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:311-315. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08223.x

- Abtahi-Naeini B, Rastegarnasab F, Saffaei A. Liquid vitamin E injection for cosmetic facial rejuvenation: a disaster report of lipogranuloma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:5549-5554. doi:10.1111/jocd.15294

- Kamouna B, Litov I, Bardarov E, et al. Granuloma formation after oil-soluble vitamin D injection for lip augmentation - case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1435-1436. doi:10.1111/jdv.13277

- Kamouna B, Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, et al. Complications of injected vitamin E as a filler for lip augmentation: case series and therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:94-97. doi:10.1111/dth.12203

- Kosari P, Alikhan A, Sockolov M, et al. Vitamin E and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2010;21:148-153

- Thiele JJ, Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage S. Vitamin E in human skin: organ-specific physiology and considerations for its use in dermatology. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:646-667. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.06.001

- Spataro EA, Dierks K, Carniol PJ. Microneedling-associated procedures to enhance facial rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2022;30:389-397. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2022.03.012

- Setterfield L. The Concise Guide to Dermal Needling. Acacia Dermacare; 2017.

- Handal M, Kyriakides K, Cohen J, et al. Sarcoidal granulomatous reaction to microneedling with vitamin C serum. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;36:67-69. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.04.015

- Microneedling devices. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published 2020. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/microneedling-devices#risks

- Gowda A, Healey B, Ezaldein H, et al. A systematic review examining the potential adverse effects of microneedling. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:45-54.

- Hou A, Cohen B, Haimovic A, et al. Microneedling: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:321-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000924

- Hogan S, Velez MW, Ibrahim O. Microneedling: a new approach for treating textural abnormalities and scars. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:155-163. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.042

- Schmitt L, Marquardt Y, Amann P, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of microneedling therapy in a human three-dimensional skin model. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204318

- Friedmann DP, Mehta E, Verma KK, et al. Granulomatous reactions from microneedling: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2025;51:263-266. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000004450

- Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong JW, Duffy KL, et al. Facial allergic granulomatous reaction and systemic hypersensitivity associated with microneedle therapy for skin rejuvenation. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:68-72. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6955

- Microneedling market. The Brainy Insights. Published January, 2023. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://www.thebrainyinsights.com/report/microneedling-market-13269

- Baumann LS, Spencer J. The effects of topical vitamin E on the cosmetic appearance of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:311-315. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08223.x

- Abtahi-Naeini B, Rastegarnasab F, Saffaei A. Liquid vitamin E injection for cosmetic facial rejuvenation: a disaster report of lipogranuloma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:5549-5554. doi:10.1111/jocd.15294

- Kamouna B, Litov I, Bardarov E, et al. Granuloma formation after oil-soluble vitamin D injection for lip augmentation - case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1435-1436. doi:10.1111/jdv.13277

- Kamouna B, Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, et al. Complications of injected vitamin E as a filler for lip augmentation: case series and therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:94-97. doi:10.1111/dth.12203

- Kosari P, Alikhan A, Sockolov M, et al. Vitamin E and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2010;21:148-153

- Thiele JJ, Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage S. Vitamin E in human skin: organ-specific physiology and considerations for its use in dermatology. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:646-667. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.06.001

- Spataro EA, Dierks K, Carniol PJ. Microneedling-associated procedures to enhance facial rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2022;30:389-397. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2022.03.012

- Setterfield L. The Concise Guide to Dermal Needling. Acacia Dermacare; 2017.

- Handal M, Kyriakides K, Cohen J, et al. Sarcoidal granulomatous reaction to microneedling with vitamin C serum. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;36:67-69. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.04.015

- Microneedling devices. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published 2020. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/microneedling-devices#risks

- Gowda A, Healey B, Ezaldein H, et al. A systematic review examining the potential adverse effects of microneedling. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:45-54.

- Hou A, Cohen B, Haimovic A, et al. Microneedling: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:321-339. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000924

- Hogan S, Velez MW, Ibrahim O. Microneedling: a new approach for treating textural abnormalities and scars. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:155-163. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.042

- Schmitt L, Marquardt Y, Amann P, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of microneedling therapy in a human three-dimensional skin model. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204318

- Friedmann DP, Mehta E, Verma KK, et al. Granulomatous reactions from microneedling: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2025;51:263-266. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000004450

Destructive Facial Granuloma Following Self-Treatment With Vitamin E Oil and an At-Home Microneedling Device

Destructive Facial Granuloma Following Self-Treatment With Vitamin E Oil and an At-Home Microneedling Device

Practice Points

- Severe complications can potentially arise from at-home microneedling procedures when combined with cosmeceuticals such as vitamin E oil.

- Clinicopathologic correlation with cosmetic procedures is imperative to prompt diagnosis and treatment of these skin reactions.

- Microneedling procedures should be performed under the supervision of a board-certified dermatologist to avoid complications, and clinicians should inquire specifically about skin care routines and cosmetic procedures when patients present with unusual lesions on the face.

Diagnostic Value of Deep Punch Biopsies in Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma

Diagnostic Value of Deep Punch Biopsies in Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an exceedingly rare aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with tumor cells growing selectively in vascular lumina.1 The annual incidence of IVBCL is fewer than 0.5 cases per 1,000,000 individuals worldwide.2 Only about 500 known cases of IVBCL have been recorded in the literature,3 and it accounts for less than 1% of all lymphomas. It generally affects middle-aged to elderly individuals, with an average age at diagnosis of 70 years.2 It has a predilection for men and commonly develops in individuals who are immunosuppressed.3,4

Multiple variants of IVBCL have been described in the literature, with central nervous system and cutaneous involvement being the most classic findings.5 Bone marrow involvement with hepatosplenomegaly also has been noted in the literature.6,7 Diagnosis of IVBCL and its variants requires a high index of suspicion, as the clinical manifestations and tissues involved typically are nonspecific and highly variable. Even in the classic variant of IVBCL, skin involvement is only reported in approximately half of cases.3 When present, cutaneous manifestations can range from nodules and violaceous plaques to induration and telangiectasias.3 Lymphadenopathy and lymphoma (leukemic) cells are not seen on a peripheral blood smear.2,8,9

The lack of lymphadenopathy or identifiable leukemic cells in the peripheral blood presents a diagnostic dilemma, as sufficient information for accurate diagnosis must be obtained while minimizing invasive procedures and resource expenditure. Because IVBCL cells can reside in the vascular lumina of various organs, numerous biopsy sites have been proposed for diagnosis of lymphoma, including the bone marrow, skin, prostate, adrenal gland, brain, liver, and kidneys.10 While some studies have reported that the optimal diagnostic site is the bone marrow, skin biopsies are more routinely carried out, as they represent a convenient and cost-effective alternative to other more invasive techniques.6,7,10 Studies have shown biopsy sensitivity values ranging from 77.8% to 83.3% for detection of IVBCL in normal-appearing skin, which is comparable to the sensitivities of a bone marrow biopsy.7,8 Although skin biopsy of random sites has shown diagnostic efficacy, some studies have proposed that biopsies taken from hemangiomas and other hypervascular lesions can further improve diagnostic yield, as lymphoma cells often are present in capillaries of subcutaneous adipose tissue.6,10,11 However, no obvious clinicopathologic differences were observed between IVBCL with and without involvement of a cutaneous hemangioma.11

The purpose of this study was to determine the diagnostic efficacy of skin biopsies for detecting IVBCL at various body sites and to establish whether biopsies from hemangiomas yield higher diagnostic value.

Methods

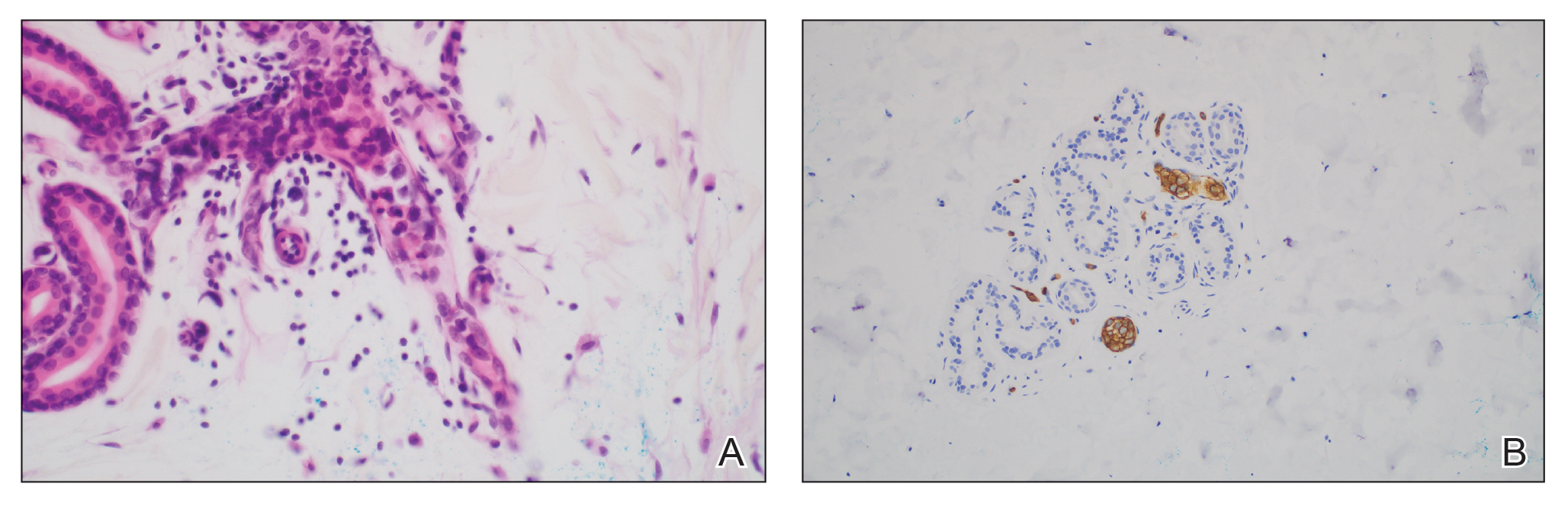

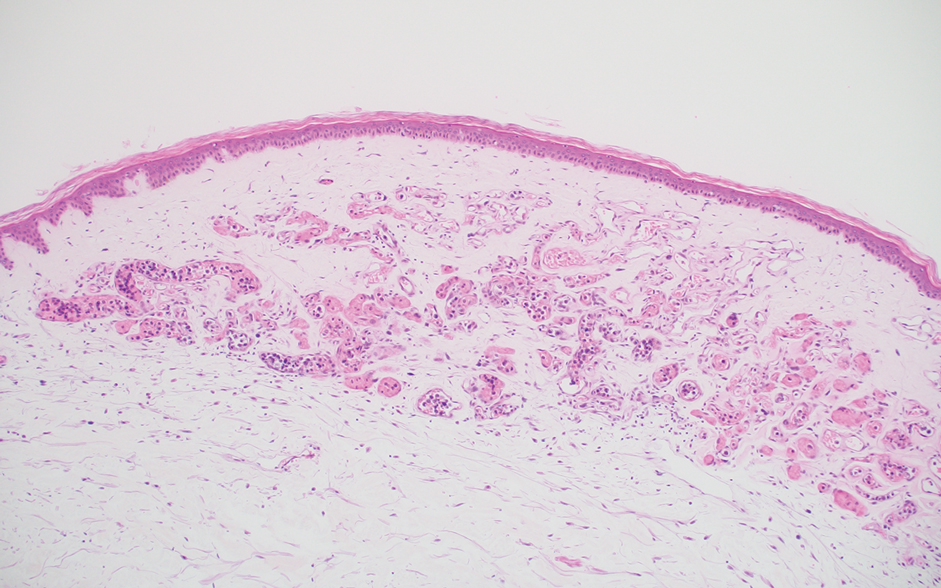

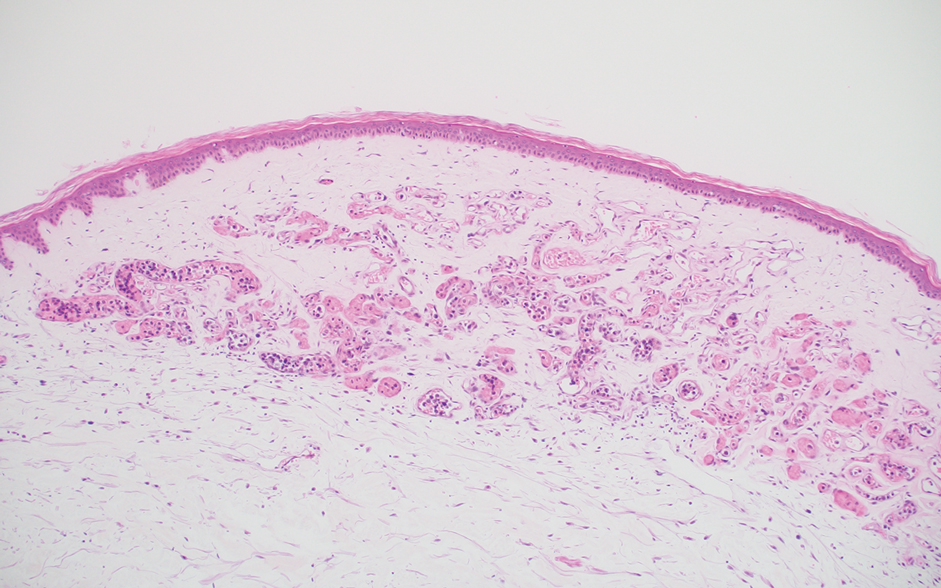

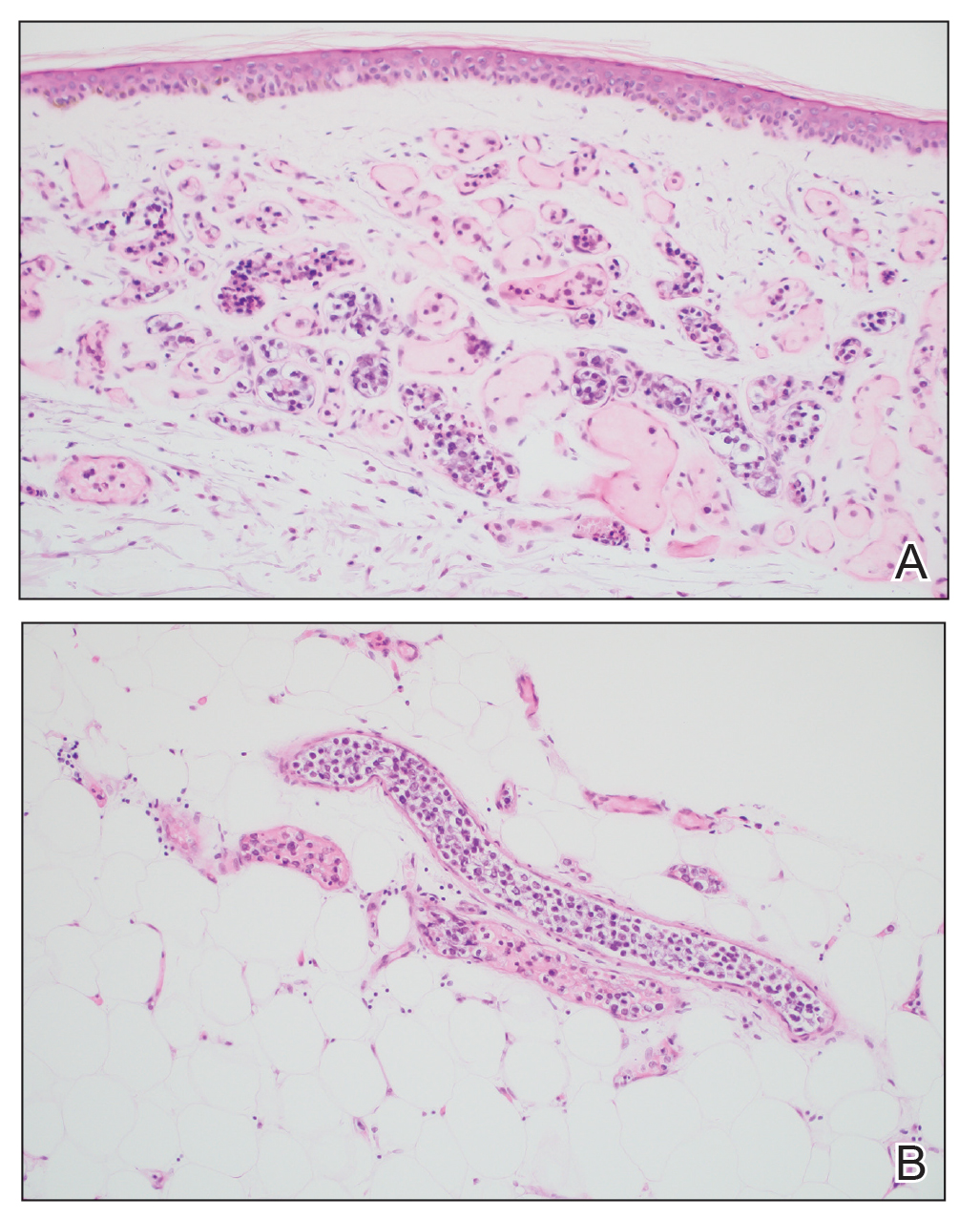

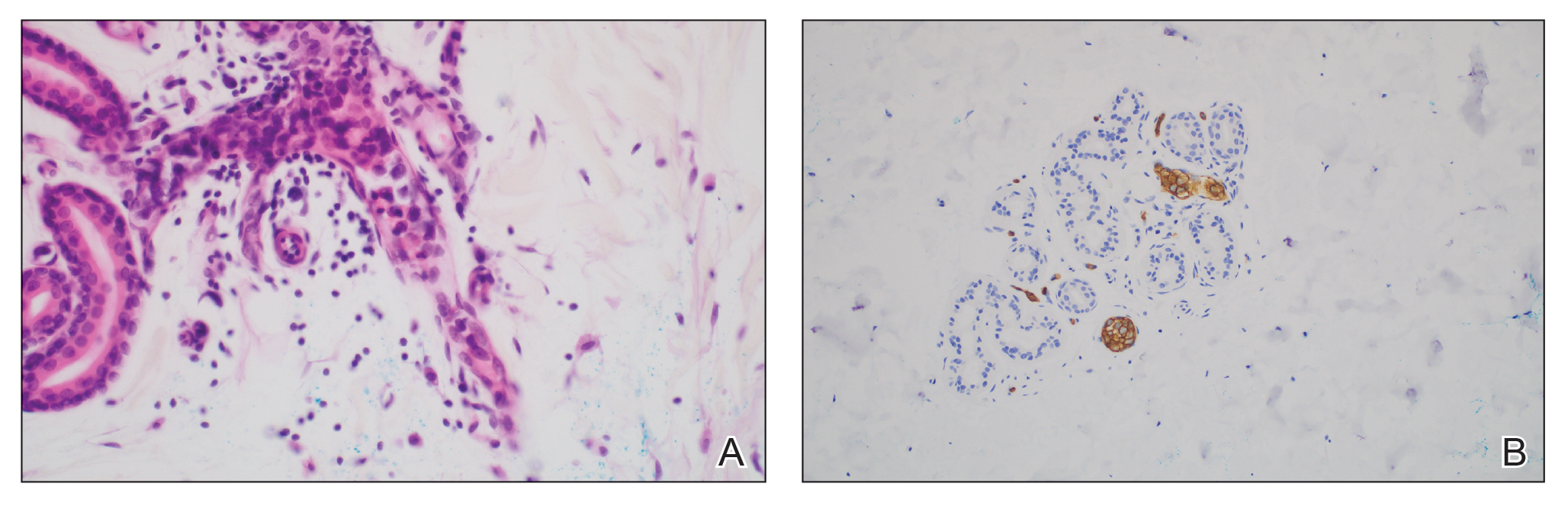

A 66-year-old man recently died at our institution secondary to IVBCL. His disease course was characterized by multiple hospital admissions in a 6-month period for fever of unknown origin and tachycardia unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics and systemic steroids. The patient declined over the course of 3 to 4 weeks with findings suggestive of lymphoma and tumor lysis syndrome, and he eventually developed shock, hypoxic respiratory failure, and acute renal failure. As imaging studies and examinations had not shown lymphadenopathy, bone marrow biopsy was performed, and dermatology was consulted to perform skin biopsies to evaluate for IVBCL. Both bone marrow biopsies and random skin biopsies from the abdomen showed large and atypical CD20+ B cells within select vascular lumina (Figure). No extravascular lymphoma cells were seen. Based on the bone marrow and skin biopsies, a diagnosis of IVBCL was made. Unfortunately, no progress was made clinically, and the patient was transitioned to comfort measures. Upon the patient’s death, his family expressed interest in participating in IVBCL research and agreed to a limited autopsy consisting of numerous skin biopsies to evaluate different body sites and biopsy types (normal skin vs hemangiomas) to ascertain whether diagnostic yield could be increased by performing selective biopsies of hemangiomas if IVBCL was suspected.

Twenty-four postmortem 4-mm punch biopsies containing subcutaneous adipose tissue were taken within 24 hours of the death of the patient before embalming. The biopsies were taken from all regions of the body except the head and neck for cosmetic preservation of the decedent. Eighteen of the biopsies were taken from random sites of normal-appearing skin; the remaining 6 were taken from clinically identifiable cherry hemangiomas (5 on the trunk and 1 on the thigh). There was a variable degree of livor mortis in the dependent areas of the body, which was included in the random biopsies from the back to ensure any pooling of dependent blood would not alter the findings.

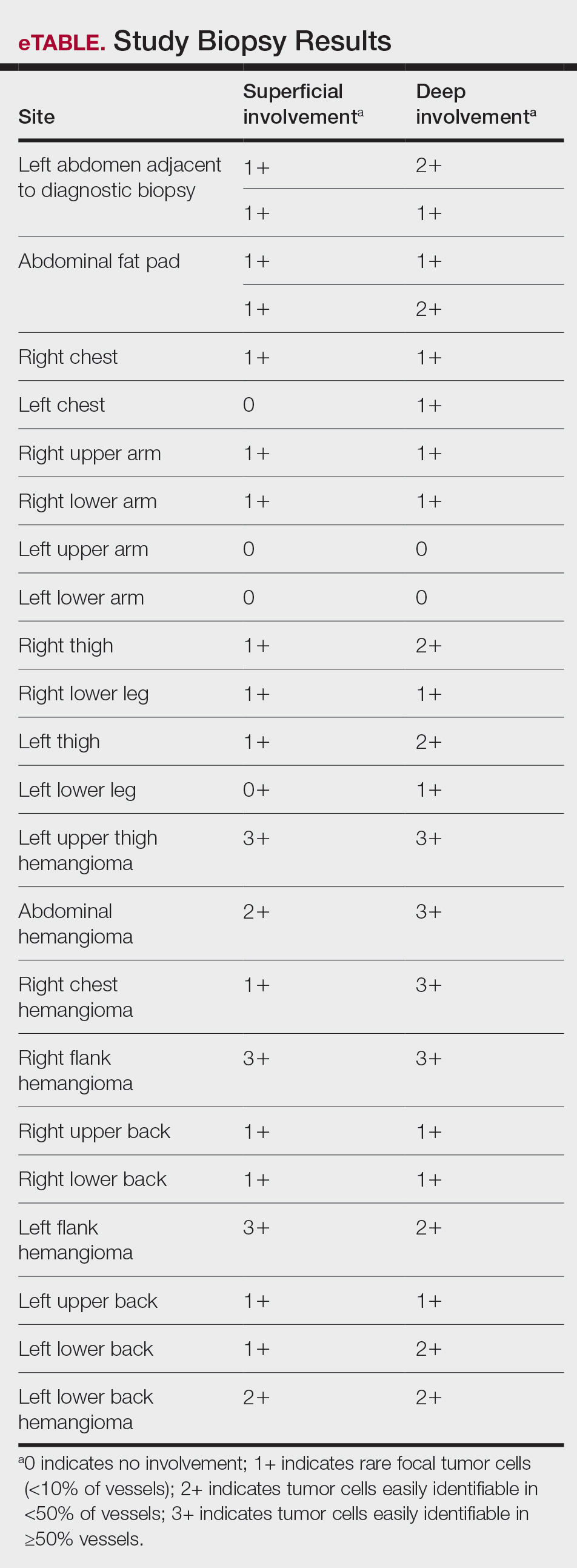

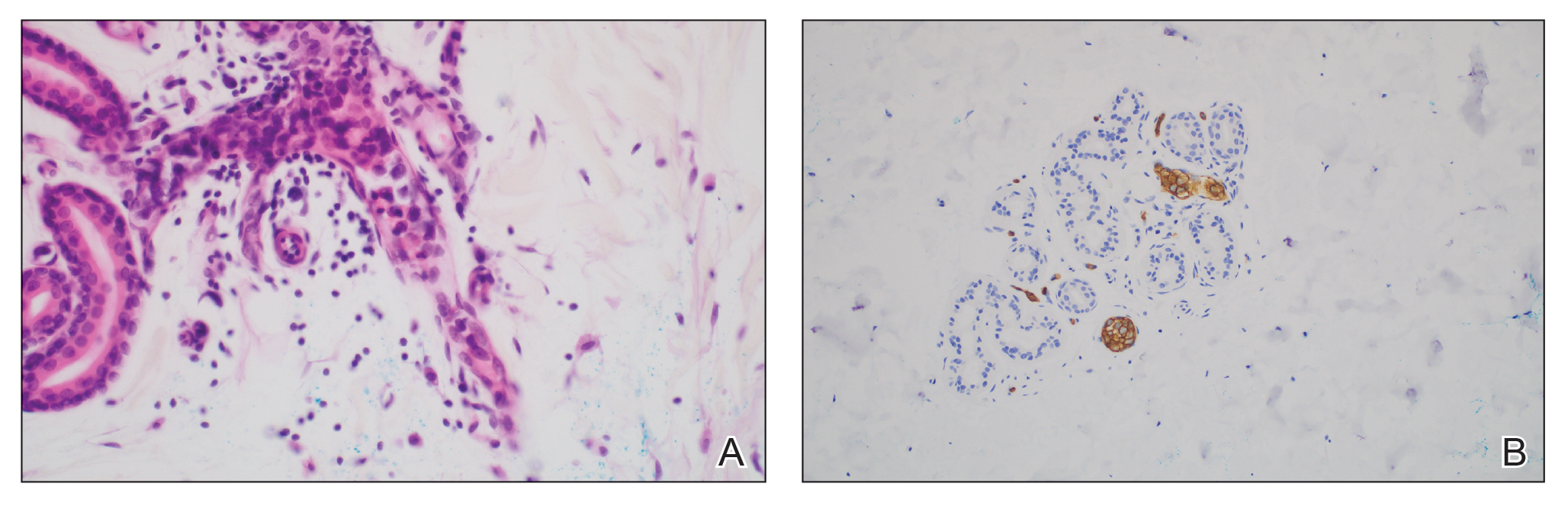

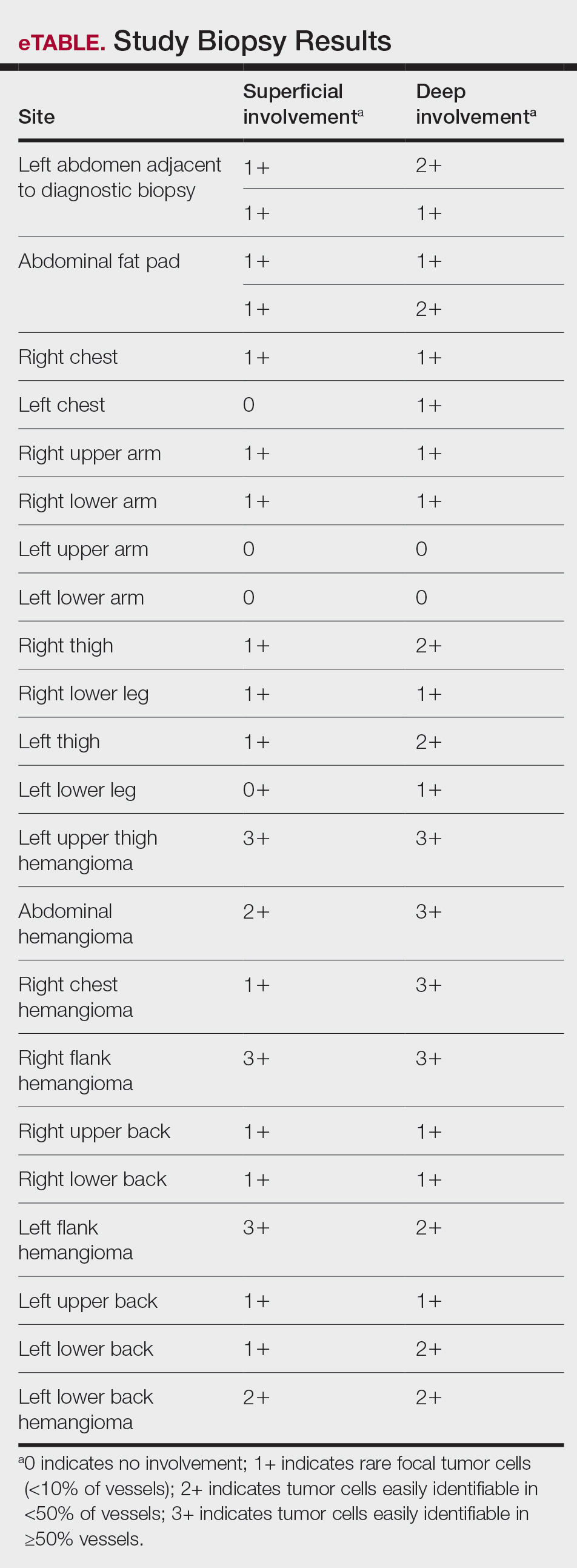

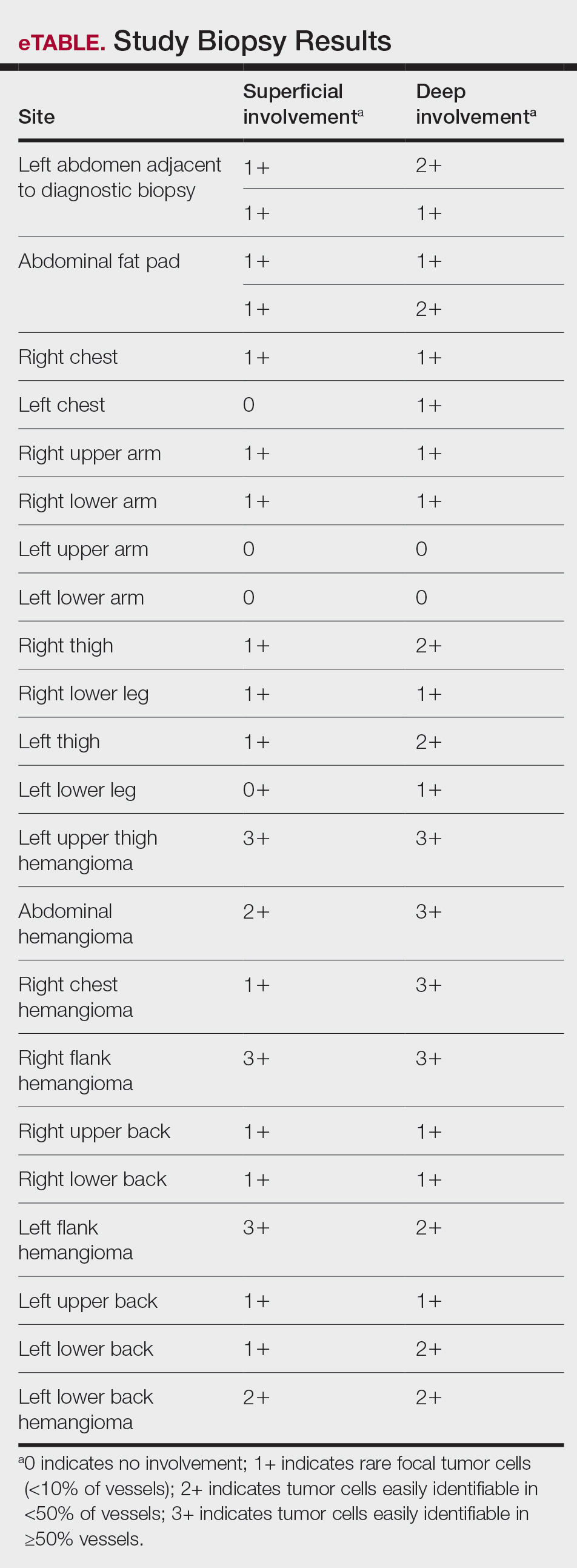

A histopathologic examination by a board-certified dermatopathologist (M.P.) on a single hematoxylin-eosin–stained level was performed to evaluate each biopsy for superficial involvement and deep involvement by IVBCL. Superficial involvement was defined as dermal involvement at or above the level of the eccrine sweat glands; deep involvement was defined as dermal involvement beneath the eccrine sweat glands and all subcutaneous fat present. Skin and bone marrow biopsies used to make the original diagnosis prior to the patient’s death were reviewed, including CD20 immunohistochemistry for morphologic comparison to the study slides. Involvement was graded as 0 to 3+ (eTable).

Results

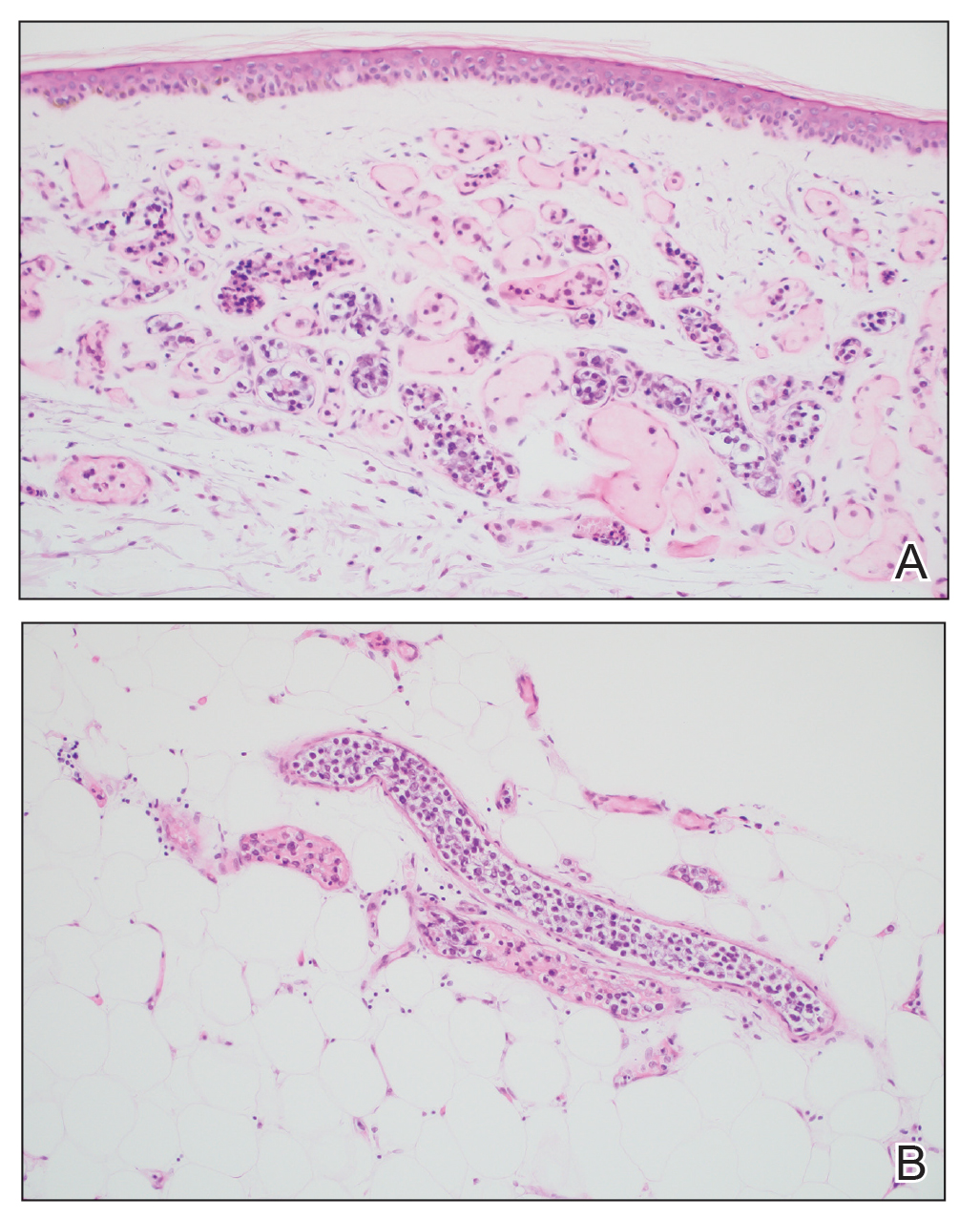

Results from all 24 biopsies are shown in the eTable. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies showed at least focal involvement by IVBCL. Nine (37.5%) biopsies showed more deep vs superficial involvement of the same site. On average, the 6 biopsies from clinically detected hemangiomas showed more involvement by IVBCL than the random biopsies (eFigures 1 and 2A). The superficial involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.33 v 0.78 when compared with the superficial aspect of the random biopsies; the deep involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.67 vs 1.16 when compared with the deep aspect of the random biopsies (eFigure 2B).

Comment

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is an aggressive malignancy that traditionally is difficult to diagnose. Many efforts have been made to improve detection and early diagnosis. As cutaneous involvement is common and sometimes the only sign of disease, dermatologists may be called upon to evaluate and biopsy patients with this suspected diagnosis. The purpose of our study was to improve diagnostic efficacy by methodically performing numerous biopsies and assessing the level of involvement of the superficial and deep skin as well as involvement of hemangiomas. The goal of this meticulous approach was to identify the highest-yield areas for biopsy with minimal impact on the patient. Our results showed that random skin biopsies are an effective way to identify IVBCL. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies contained at least focal lymphoma cells. Although the 2 biopsies that showed no tumor cells at all happened to both be from the left arm, this is believed to be coincidental. No discernable pattern was identified regarding involvement and anatomic region. Even though 20 (83.3%) biopsies showed superficial involvement, deep biopsy is essential, as 9 (37.5%) biopsies showed increased deep involvement compared to superficial involvement. Therefore, a deep punch biopsy is essential for maximum sensitivity.

Hemangiomas provide a potential target that could increase the sensitivity of a biopsy in the absence of clinical findings, when the disease in question is exclusively intravascular. The data gathered in this study support this idea, as biopsies from hemangiomas showed increased involvement compared to random biopsies, both superficially and deep (2.33 vs 0.78 and 2.67 vs 1.16, respectively). Interestingly, the hemangioma biopsy sites showed increased deep and superficial involvement, despite these typical cherry hemangiomas only involving the superficial dermis. One possible explanation for this is that the hemangiomas have larger-caliber feeder vessels with increased blood flow beneath them. It would then follow that this increased vasculature would increase the chances of identifying intravascular lymphoma cells. This finding further accentuates the need for a deep punch biopsy containing subcutaneous fat.

Completing the study in the setting of an autopsy provided the advantage of being able to take numerous biopsies without increased harm to the patient. This extensive set of biopsies would not be reasonable to complete on a living patient. This study also has limitations. Although this patient did fall within the typical demographics for patients with IVBCL, the data were still limited to 1 patient. This autopsy format (on a patient whose cause of death was indeed IVBCL) also implies terminal disease, which may mean the patient had a larger disease burden than a living patient who would typically be biopsied. Although this increased disease burden may have increased the sensitivity of finding IVBCL in the biopsies of this study, this further emphasizes the importance of trying to determine any factors that could increase sensitivity in a living patient with a lower disease burden.

Conclusion

Skin biopsies can provide a sensitive, low-cost, and low-morbidity method to assess a patient for IVBCL. Though random skin biopsies can yield valuable information, deep, 4-mm punch biopsies of clinically identifiable hemangiomas may provide the highest sensitivity for IVBCL.

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Roy AM, Pandey Y, Middleton D, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Cureus. 2021;13:e16459. doi:10.7759/cureus.16459

- Bayçelebi D, Yildiz L, S?entürk N. A case report and literature review of cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting clinically as panniculitis: a difficult diagnosis, but a good prognosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:72-75. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.08.004

- Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:333-338. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0747-RS

- Breakell T, Waibel H, Schliep S, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a review with a focus on the prognostic value of skininvolvement. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:2909-2919. doi:10.3390/curroncol29050237

- Oppegard L, O’Donnell M, Piro K, et al. Going skin deep: excavating a diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3368-3371. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06141-1

- Barker JL, Swarup O, Puliyayil A. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: representative cases and approach to diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e244069. doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-244069

- Matsue K, Asada N, Odawara J, et al. Random skin biopsy and bone marrow biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:417-421. doi:10.1007/s00277-010-1101-3

- Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, et al. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:895-902. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70140-8

- Adachi Y, Kosami K, Mizuta N, et al. Benefits of skin biopsy of senile hemangioma in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:2003-2006. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2017

- Ishida M, Hodohara K, Yoshida T, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma colonizing in senile hemangioma: a case report and proposal of possible diagnostic strategy for intravascular lymphoma. Pathol Int. 2011;61:555-557. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02697.x

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an exceedingly rare aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with tumor cells growing selectively in vascular lumina.1 The annual incidence of IVBCL is fewer than 0.5 cases per 1,000,000 individuals worldwide.2 Only about 500 known cases of IVBCL have been recorded in the literature,3 and it accounts for less than 1% of all lymphomas. It generally affects middle-aged to elderly individuals, with an average age at diagnosis of 70 years.2 It has a predilection for men and commonly develops in individuals who are immunosuppressed.3,4

Multiple variants of IVBCL have been described in the literature, with central nervous system and cutaneous involvement being the most classic findings.5 Bone marrow involvement with hepatosplenomegaly also has been noted in the literature.6,7 Diagnosis of IVBCL and its variants requires a high index of suspicion, as the clinical manifestations and tissues involved typically are nonspecific and highly variable. Even in the classic variant of IVBCL, skin involvement is only reported in approximately half of cases.3 When present, cutaneous manifestations can range from nodules and violaceous plaques to induration and telangiectasias.3 Lymphadenopathy and lymphoma (leukemic) cells are not seen on a peripheral blood smear.2,8,9

The lack of lymphadenopathy or identifiable leukemic cells in the peripheral blood presents a diagnostic dilemma, as sufficient information for accurate diagnosis must be obtained while minimizing invasive procedures and resource expenditure. Because IVBCL cells can reside in the vascular lumina of various organs, numerous biopsy sites have been proposed for diagnosis of lymphoma, including the bone marrow, skin, prostate, adrenal gland, brain, liver, and kidneys.10 While some studies have reported that the optimal diagnostic site is the bone marrow, skin biopsies are more routinely carried out, as they represent a convenient and cost-effective alternative to other more invasive techniques.6,7,10 Studies have shown biopsy sensitivity values ranging from 77.8% to 83.3% for detection of IVBCL in normal-appearing skin, which is comparable to the sensitivities of a bone marrow biopsy.7,8 Although skin biopsy of random sites has shown diagnostic efficacy, some studies have proposed that biopsies taken from hemangiomas and other hypervascular lesions can further improve diagnostic yield, as lymphoma cells often are present in capillaries of subcutaneous adipose tissue.6,10,11 However, no obvious clinicopathologic differences were observed between IVBCL with and without involvement of a cutaneous hemangioma.11

The purpose of this study was to determine the diagnostic efficacy of skin biopsies for detecting IVBCL at various body sites and to establish whether biopsies from hemangiomas yield higher diagnostic value.

Methods

A 66-year-old man recently died at our institution secondary to IVBCL. His disease course was characterized by multiple hospital admissions in a 6-month period for fever of unknown origin and tachycardia unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics and systemic steroids. The patient declined over the course of 3 to 4 weeks with findings suggestive of lymphoma and tumor lysis syndrome, and he eventually developed shock, hypoxic respiratory failure, and acute renal failure. As imaging studies and examinations had not shown lymphadenopathy, bone marrow biopsy was performed, and dermatology was consulted to perform skin biopsies to evaluate for IVBCL. Both bone marrow biopsies and random skin biopsies from the abdomen showed large and atypical CD20+ B cells within select vascular lumina (Figure). No extravascular lymphoma cells were seen. Based on the bone marrow and skin biopsies, a diagnosis of IVBCL was made. Unfortunately, no progress was made clinically, and the patient was transitioned to comfort measures. Upon the patient’s death, his family expressed interest in participating in IVBCL research and agreed to a limited autopsy consisting of numerous skin biopsies to evaluate different body sites and biopsy types (normal skin vs hemangiomas) to ascertain whether diagnostic yield could be increased by performing selective biopsies of hemangiomas if IVBCL was suspected.

Twenty-four postmortem 4-mm punch biopsies containing subcutaneous adipose tissue were taken within 24 hours of the death of the patient before embalming. The biopsies were taken from all regions of the body except the head and neck for cosmetic preservation of the decedent. Eighteen of the biopsies were taken from random sites of normal-appearing skin; the remaining 6 were taken from clinically identifiable cherry hemangiomas (5 on the trunk and 1 on the thigh). There was a variable degree of livor mortis in the dependent areas of the body, which was included in the random biopsies from the back to ensure any pooling of dependent blood would not alter the findings.

A histopathologic examination by a board-certified dermatopathologist (M.P.) on a single hematoxylin-eosin–stained level was performed to evaluate each biopsy for superficial involvement and deep involvement by IVBCL. Superficial involvement was defined as dermal involvement at or above the level of the eccrine sweat glands; deep involvement was defined as dermal involvement beneath the eccrine sweat glands and all subcutaneous fat present. Skin and bone marrow biopsies used to make the original diagnosis prior to the patient’s death were reviewed, including CD20 immunohistochemistry for morphologic comparison to the study slides. Involvement was graded as 0 to 3+ (eTable).

Results

Results from all 24 biopsies are shown in the eTable. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies showed at least focal involvement by IVBCL. Nine (37.5%) biopsies showed more deep vs superficial involvement of the same site. On average, the 6 biopsies from clinically detected hemangiomas showed more involvement by IVBCL than the random biopsies (eFigures 1 and 2A). The superficial involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.33 v 0.78 when compared with the superficial aspect of the random biopsies; the deep involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.67 vs 1.16 when compared with the deep aspect of the random biopsies (eFigure 2B).

Comment

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is an aggressive malignancy that traditionally is difficult to diagnose. Many efforts have been made to improve detection and early diagnosis. As cutaneous involvement is common and sometimes the only sign of disease, dermatologists may be called upon to evaluate and biopsy patients with this suspected diagnosis. The purpose of our study was to improve diagnostic efficacy by methodically performing numerous biopsies and assessing the level of involvement of the superficial and deep skin as well as involvement of hemangiomas. The goal of this meticulous approach was to identify the highest-yield areas for biopsy with minimal impact on the patient. Our results showed that random skin biopsies are an effective way to identify IVBCL. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies contained at least focal lymphoma cells. Although the 2 biopsies that showed no tumor cells at all happened to both be from the left arm, this is believed to be coincidental. No discernable pattern was identified regarding involvement and anatomic region. Even though 20 (83.3%) biopsies showed superficial involvement, deep biopsy is essential, as 9 (37.5%) biopsies showed increased deep involvement compared to superficial involvement. Therefore, a deep punch biopsy is essential for maximum sensitivity.

Hemangiomas provide a potential target that could increase the sensitivity of a biopsy in the absence of clinical findings, when the disease in question is exclusively intravascular. The data gathered in this study support this idea, as biopsies from hemangiomas showed increased involvement compared to random biopsies, both superficially and deep (2.33 vs 0.78 and 2.67 vs 1.16, respectively). Interestingly, the hemangioma biopsy sites showed increased deep and superficial involvement, despite these typical cherry hemangiomas only involving the superficial dermis. One possible explanation for this is that the hemangiomas have larger-caliber feeder vessels with increased blood flow beneath them. It would then follow that this increased vasculature would increase the chances of identifying intravascular lymphoma cells. This finding further accentuates the need for a deep punch biopsy containing subcutaneous fat.

Completing the study in the setting of an autopsy provided the advantage of being able to take numerous biopsies without increased harm to the patient. This extensive set of biopsies would not be reasonable to complete on a living patient. This study also has limitations. Although this patient did fall within the typical demographics for patients with IVBCL, the data were still limited to 1 patient. This autopsy format (on a patient whose cause of death was indeed IVBCL) also implies terminal disease, which may mean the patient had a larger disease burden than a living patient who would typically be biopsied. Although this increased disease burden may have increased the sensitivity of finding IVBCL in the biopsies of this study, this further emphasizes the importance of trying to determine any factors that could increase sensitivity in a living patient with a lower disease burden.

Conclusion

Skin biopsies can provide a sensitive, low-cost, and low-morbidity method to assess a patient for IVBCL. Though random skin biopsies can yield valuable information, deep, 4-mm punch biopsies of clinically identifiable hemangiomas may provide the highest sensitivity for IVBCL.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an exceedingly rare aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with tumor cells growing selectively in vascular lumina.1 The annual incidence of IVBCL is fewer than 0.5 cases per 1,000,000 individuals worldwide.2 Only about 500 known cases of IVBCL have been recorded in the literature,3 and it accounts for less than 1% of all lymphomas. It generally affects middle-aged to elderly individuals, with an average age at diagnosis of 70 years.2 It has a predilection for men and commonly develops in individuals who are immunosuppressed.3,4

Multiple variants of IVBCL have been described in the literature, with central nervous system and cutaneous involvement being the most classic findings.5 Bone marrow involvement with hepatosplenomegaly also has been noted in the literature.6,7 Diagnosis of IVBCL and its variants requires a high index of suspicion, as the clinical manifestations and tissues involved typically are nonspecific and highly variable. Even in the classic variant of IVBCL, skin involvement is only reported in approximately half of cases.3 When present, cutaneous manifestations can range from nodules and violaceous plaques to induration and telangiectasias.3 Lymphadenopathy and lymphoma (leukemic) cells are not seen on a peripheral blood smear.2,8,9

The lack of lymphadenopathy or identifiable leukemic cells in the peripheral blood presents a diagnostic dilemma, as sufficient information for accurate diagnosis must be obtained while minimizing invasive procedures and resource expenditure. Because IVBCL cells can reside in the vascular lumina of various organs, numerous biopsy sites have been proposed for diagnosis of lymphoma, including the bone marrow, skin, prostate, adrenal gland, brain, liver, and kidneys.10 While some studies have reported that the optimal diagnostic site is the bone marrow, skin biopsies are more routinely carried out, as they represent a convenient and cost-effective alternative to other more invasive techniques.6,7,10 Studies have shown biopsy sensitivity values ranging from 77.8% to 83.3% for detection of IVBCL in normal-appearing skin, which is comparable to the sensitivities of a bone marrow biopsy.7,8 Although skin biopsy of random sites has shown diagnostic efficacy, some studies have proposed that biopsies taken from hemangiomas and other hypervascular lesions can further improve diagnostic yield, as lymphoma cells often are present in capillaries of subcutaneous adipose tissue.6,10,11 However, no obvious clinicopathologic differences were observed between IVBCL with and without involvement of a cutaneous hemangioma.11

The purpose of this study was to determine the diagnostic efficacy of skin biopsies for detecting IVBCL at various body sites and to establish whether biopsies from hemangiomas yield higher diagnostic value.

Methods

A 66-year-old man recently died at our institution secondary to IVBCL. His disease course was characterized by multiple hospital admissions in a 6-month period for fever of unknown origin and tachycardia unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics and systemic steroids. The patient declined over the course of 3 to 4 weeks with findings suggestive of lymphoma and tumor lysis syndrome, and he eventually developed shock, hypoxic respiratory failure, and acute renal failure. As imaging studies and examinations had not shown lymphadenopathy, bone marrow biopsy was performed, and dermatology was consulted to perform skin biopsies to evaluate for IVBCL. Both bone marrow biopsies and random skin biopsies from the abdomen showed large and atypical CD20+ B cells within select vascular lumina (Figure). No extravascular lymphoma cells were seen. Based on the bone marrow and skin biopsies, a diagnosis of IVBCL was made. Unfortunately, no progress was made clinically, and the patient was transitioned to comfort measures. Upon the patient’s death, his family expressed interest in participating in IVBCL research and agreed to a limited autopsy consisting of numerous skin biopsies to evaluate different body sites and biopsy types (normal skin vs hemangiomas) to ascertain whether diagnostic yield could be increased by performing selective biopsies of hemangiomas if IVBCL was suspected.

Twenty-four postmortem 4-mm punch biopsies containing subcutaneous adipose tissue were taken within 24 hours of the death of the patient before embalming. The biopsies were taken from all regions of the body except the head and neck for cosmetic preservation of the decedent. Eighteen of the biopsies were taken from random sites of normal-appearing skin; the remaining 6 were taken from clinically identifiable cherry hemangiomas (5 on the trunk and 1 on the thigh). There was a variable degree of livor mortis in the dependent areas of the body, which was included in the random biopsies from the back to ensure any pooling of dependent blood would not alter the findings.

A histopathologic examination by a board-certified dermatopathologist (M.P.) on a single hematoxylin-eosin–stained level was performed to evaluate each biopsy for superficial involvement and deep involvement by IVBCL. Superficial involvement was defined as dermal involvement at or above the level of the eccrine sweat glands; deep involvement was defined as dermal involvement beneath the eccrine sweat glands and all subcutaneous fat present. Skin and bone marrow biopsies used to make the original diagnosis prior to the patient’s death were reviewed, including CD20 immunohistochemistry for morphologic comparison to the study slides. Involvement was graded as 0 to 3+ (eTable).

Results

Results from all 24 biopsies are shown in the eTable. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies showed at least focal involvement by IVBCL. Nine (37.5%) biopsies showed more deep vs superficial involvement of the same site. On average, the 6 biopsies from clinically detected hemangiomas showed more involvement by IVBCL than the random biopsies (eFigures 1 and 2A). The superficial involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.33 v 0.78 when compared with the superficial aspect of the random biopsies; the deep involvement of skin with a hemangioma showed an average score of 2.67 vs 1.16 when compared with the deep aspect of the random biopsies (eFigure 2B).

Comment

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is an aggressive malignancy that traditionally is difficult to diagnose. Many efforts have been made to improve detection and early diagnosis. As cutaneous involvement is common and sometimes the only sign of disease, dermatologists may be called upon to evaluate and biopsy patients with this suspected diagnosis. The purpose of our study was to improve diagnostic efficacy by methodically performing numerous biopsies and assessing the level of involvement of the superficial and deep skin as well as involvement of hemangiomas. The goal of this meticulous approach was to identify the highest-yield areas for biopsy with minimal impact on the patient. Our results showed that random skin biopsies are an effective way to identify IVBCL. Twenty-two (91.7%) biopsies contained at least focal lymphoma cells. Although the 2 biopsies that showed no tumor cells at all happened to both be from the left arm, this is believed to be coincidental. No discernable pattern was identified regarding involvement and anatomic region. Even though 20 (83.3%) biopsies showed superficial involvement, deep biopsy is essential, as 9 (37.5%) biopsies showed increased deep involvement compared to superficial involvement. Therefore, a deep punch biopsy is essential for maximum sensitivity.

Hemangiomas provide a potential target that could increase the sensitivity of a biopsy in the absence of clinical findings, when the disease in question is exclusively intravascular. The data gathered in this study support this idea, as biopsies from hemangiomas showed increased involvement compared to random biopsies, both superficially and deep (2.33 vs 0.78 and 2.67 vs 1.16, respectively). Interestingly, the hemangioma biopsy sites showed increased deep and superficial involvement, despite these typical cherry hemangiomas only involving the superficial dermis. One possible explanation for this is that the hemangiomas have larger-caliber feeder vessels with increased blood flow beneath them. It would then follow that this increased vasculature would increase the chances of identifying intravascular lymphoma cells. This finding further accentuates the need for a deep punch biopsy containing subcutaneous fat.

Completing the study in the setting of an autopsy provided the advantage of being able to take numerous biopsies without increased harm to the patient. This extensive set of biopsies would not be reasonable to complete on a living patient. This study also has limitations. Although this patient did fall within the typical demographics for patients with IVBCL, the data were still limited to 1 patient. This autopsy format (on a patient whose cause of death was indeed IVBCL) also implies terminal disease, which may mean the patient had a larger disease burden than a living patient who would typically be biopsied. Although this increased disease burden may have increased the sensitivity of finding IVBCL in the biopsies of this study, this further emphasizes the importance of trying to determine any factors that could increase sensitivity in a living patient with a lower disease burden.

Conclusion

Skin biopsies can provide a sensitive, low-cost, and low-morbidity method to assess a patient for IVBCL. Though random skin biopsies can yield valuable information, deep, 4-mm punch biopsies of clinically identifiable hemangiomas may provide the highest sensitivity for IVBCL.

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Roy AM, Pandey Y, Middleton D, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Cureus. 2021;13:e16459. doi:10.7759/cureus.16459

- Bayçelebi D, Yildiz L, S?entürk N. A case report and literature review of cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting clinically as panniculitis: a difficult diagnosis, but a good prognosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:72-75. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.08.004

- Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:333-338. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0747-RS

- Breakell T, Waibel H, Schliep S, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a review with a focus on the prognostic value of skininvolvement. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:2909-2919. doi:10.3390/curroncol29050237

- Oppegard L, O’Donnell M, Piro K, et al. Going skin deep: excavating a diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3368-3371. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06141-1

- Barker JL, Swarup O, Puliyayil A. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: representative cases and approach to diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e244069. doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-244069

- Matsue K, Asada N, Odawara J, et al. Random skin biopsy and bone marrow biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:417-421. doi:10.1007/s00277-010-1101-3

- Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, et al. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:895-902. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70140-8

- Adachi Y, Kosami K, Mizuta N, et al. Benefits of skin biopsy of senile hemangioma in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:2003-2006. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2017

- Ishida M, Hodohara K, Yoshida T, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma colonizing in senile hemangioma: a case report and proposal of possible diagnostic strategy for intravascular lymphoma. Pathol Int. 2011;61:555-557. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02697.x

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Roy AM, Pandey Y, Middleton D, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Cureus. 2021;13:e16459. doi:10.7759/cureus.16459

- Bayçelebi D, Yildiz L, S?entürk N. A case report and literature review of cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting clinically as panniculitis: a difficult diagnosis, but a good prognosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:72-75. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.08.004

- Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:333-338. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0747-RS

- Breakell T, Waibel H, Schliep S, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a review with a focus on the prognostic value of skininvolvement. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:2909-2919. doi:10.3390/curroncol29050237

- Oppegard L, O’Donnell M, Piro K, et al. Going skin deep: excavating a diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3368-3371. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06141-1

- Barker JL, Swarup O, Puliyayil A. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: representative cases and approach to diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e244069. doi:10.1136/bcr-2021-244069

- Matsue K, Asada N, Odawara J, et al. Random skin biopsy and bone marrow biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:417-421. doi:10.1007/s00277-010-1101-3

- Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, et al. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:895-902. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70140-8

- Adachi Y, Kosami K, Mizuta N, et al. Benefits of skin biopsy of senile hemangioma in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:2003-2006. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2017

- Ishida M, Hodohara K, Yoshida T, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma colonizing in senile hemangioma: a case report and proposal of possible diagnostic strategy for intravascular lymphoma. Pathol Int. 2011;61:555-557. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02697.x

Diagnostic Value of Deep Punch Biopsies in Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma

Diagnostic Value of Deep Punch Biopsies in Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma

Practice Points

- Skin biopsy is an effective method for identifying intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL).

- Deep punch biopsies of sites involving hemangiomas may further heighten sensitivity for detection of IVBCL, as these lesions may harbor increased numbers of intravascular lymphoma cells.

- Deep and strategically placed skin biopsies offer potential improvements in timely diagnosis and outcomes of patients with IVBCL.

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

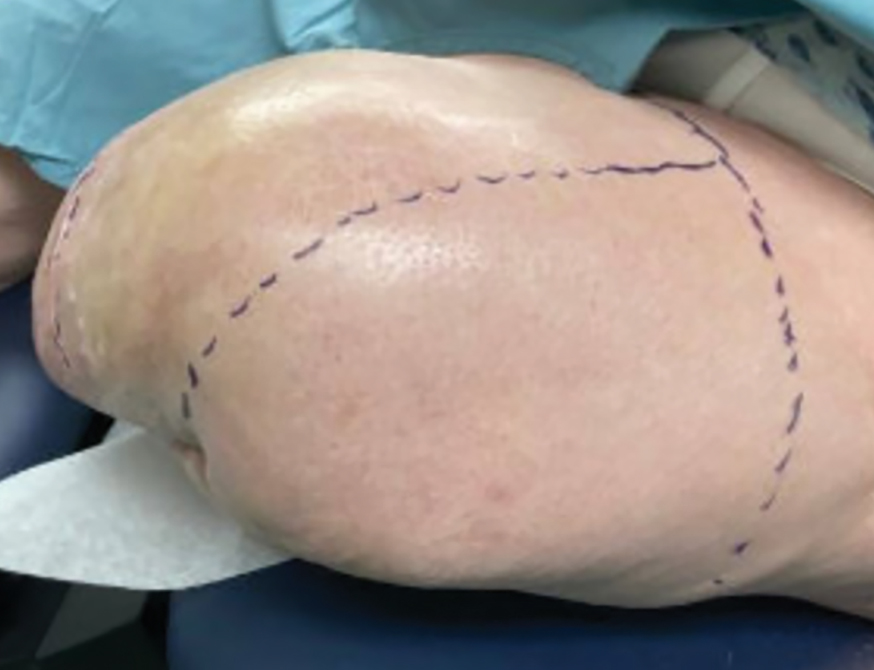

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications

This staged approach to administering BTX ensures even distribution of the injections, optimizes hyperhidrosis control, minimizes the risk for complications, and allows for precise targeting of the affected areas to maximize therapeutic benefit. Following the initial procedure, our patient was scheduled for follow-ups approximately every 3 to 4 months starting from the first set of injections for each area. Over 9 months, the patient successfully completed 3 treatment sessions using this method. The patient reported improved quality of life after starting the BTX injections.

After evaluating the initial treatment outcomes with 100 units per section, the dosage was increased to 200 units per section to reduce the number of visits from 4 every 3 months to cover the entire area to 2 visits every 3 months. This adjustment aimed to optimize results and better manage the patient’s ongoing symptoms. At about 1 to 2 weeks after beginning treatment, the patient noticed decreased sweating and discomfort during his daily activities and reduced friction with his prosthetic leg. No adverse effects were noted with the increased dosage during a clinical visit.

Our case highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to hyperhidrosis treatment. Dermatologists should prioritize patient-centered care by factoring in financial constraints when recommending therapies. In this patient’s case, offering a range of options including over-the-counter antiperspirants and prescription treatments allowed for a management plan tailored to his individual needs and circumstances.

DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known for its longer duration of action compared to other BTX formulations, presents a promising alternative for treating hyperhidrosis.4 However, a gap in care emerged for our patient when prescription antiperspirant was not covered by his insurance, and daxibotulinumtoxinA, which could have offered a more durable solution, was not yet available at our clinic for hyperhidrosis management. Expanding insurance coverage for effective prescription treatments and improving access to newer treatment options are crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and ensuring more equitable care.

Focusing dermatologic care on amputees presents distinct challenges and opportunities for improving their care and decreasing discomfort. Amputees, particularly those with residual limb hyperhidrosis, often experience additional discomfort and difficulty while using prosthetics, as excessive sweating can interfere with fit and function.5,6 Dermatologists should proactively address these specific needs by tailoring treatment accordingly. Incorporating targeted therapies, such as BTX injections, in addition to education on lifestyle modifications and managing treatment expectations, ensures comprehensive care that enhances both quality of life and functional outcomes. Engaging patients in discussions about all available options, including emerging therapies, is essential for improving care for this underserved population.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463–466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03604.x

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Rocha Melo J, Rodrigues MA, Caetano M, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis: a systematic review. Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2023;57:100754. doi:10.1016/j.rh.2022.07.003

- Hansen C, Godfrey B, Wixom J, et al. Incidence, severity, and impact of hyperhidrosis in people with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:31-40. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0108

- Lannan FM, Powell J, Kim GM, et al. Hyperhidrosis of the residual limb: a narrative review of the measurement and treatment of excess perspiration affecting individuals with amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:477-486. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000040

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications