User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Best Practices: Protecting Dry Vulnerable Skin with CeraVe® Healing Ointment

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

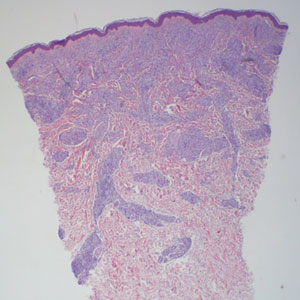

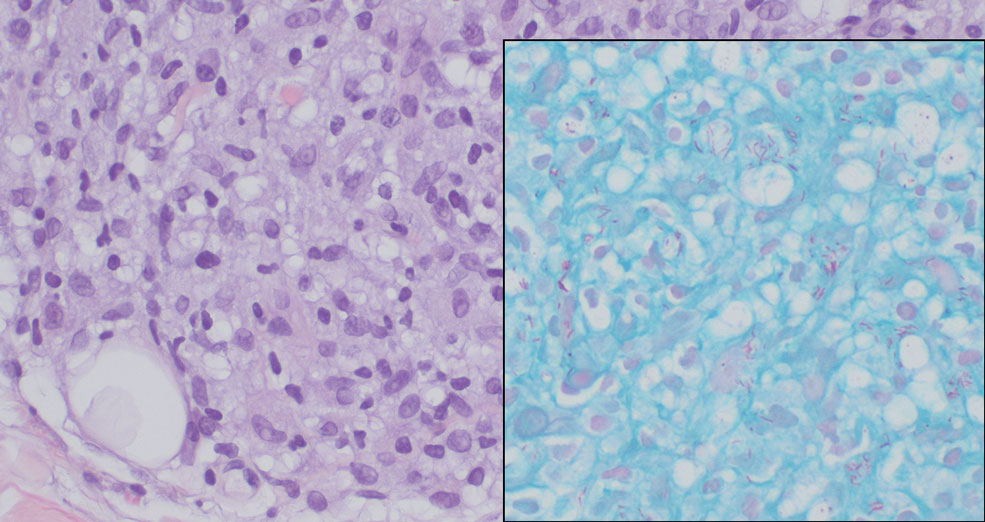

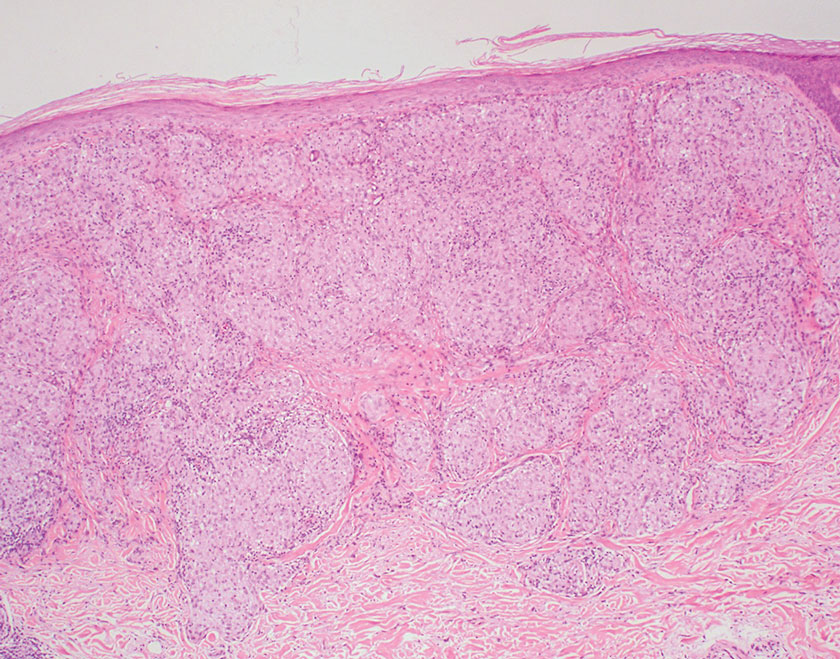

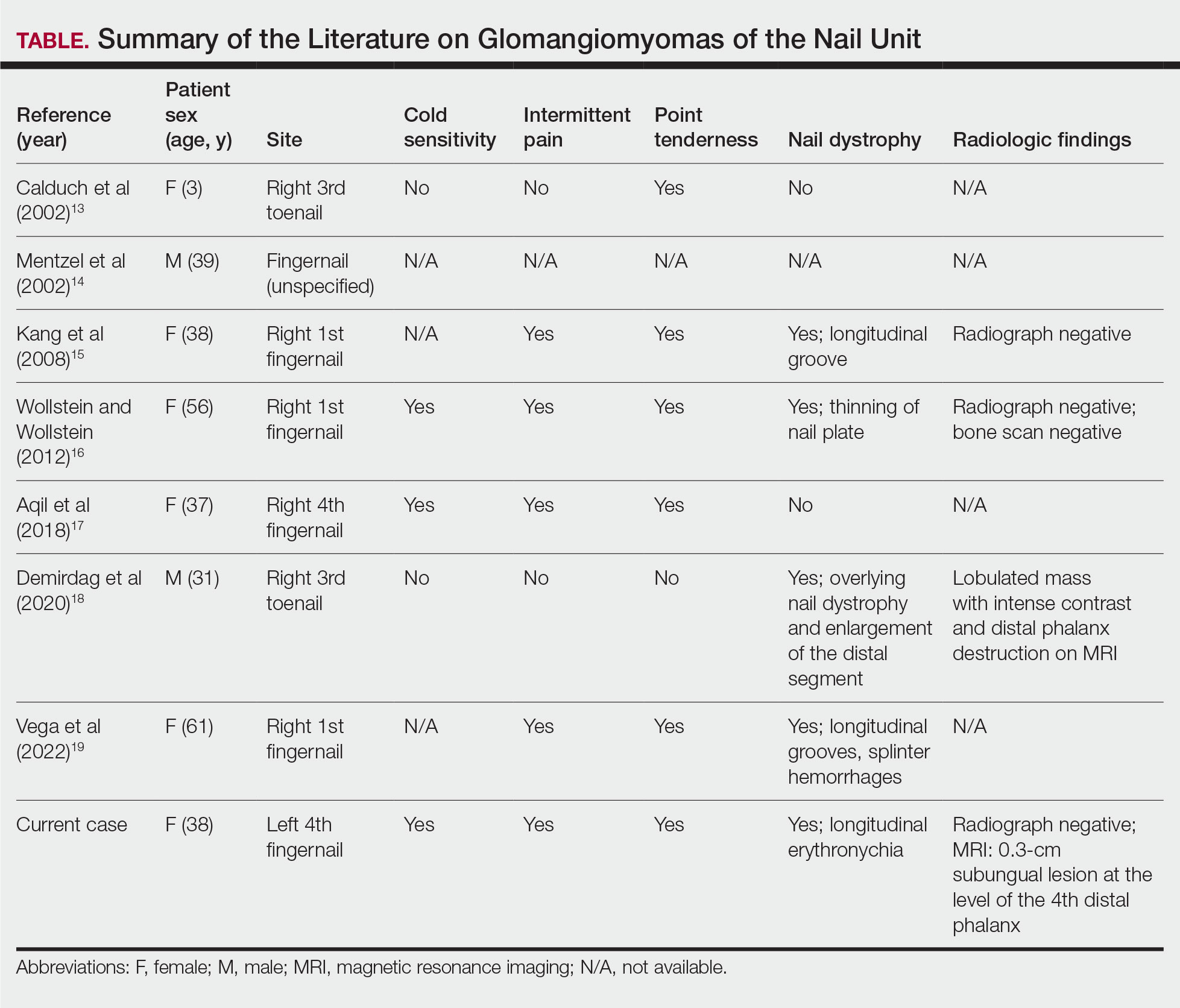

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

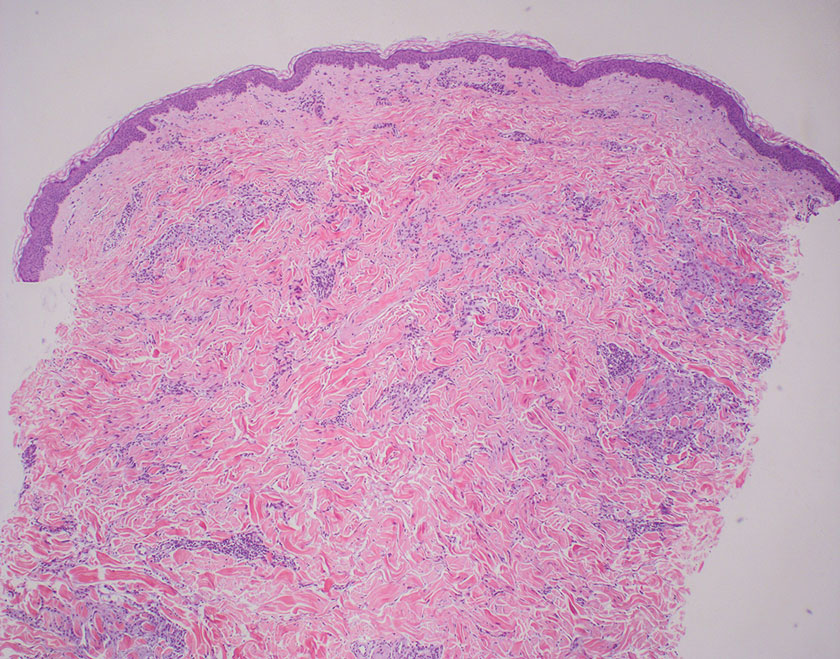

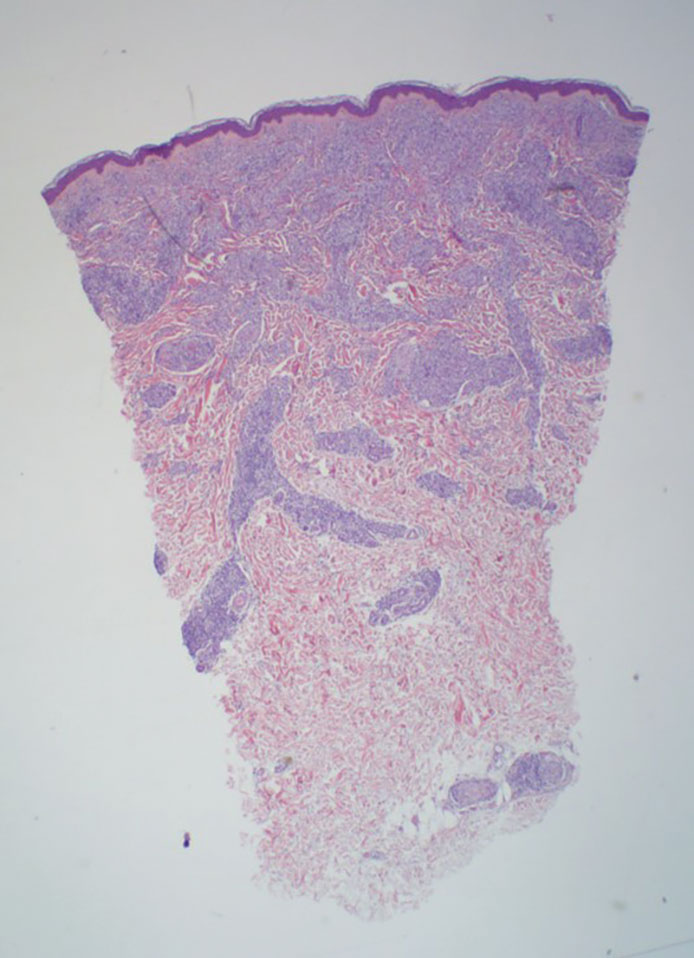

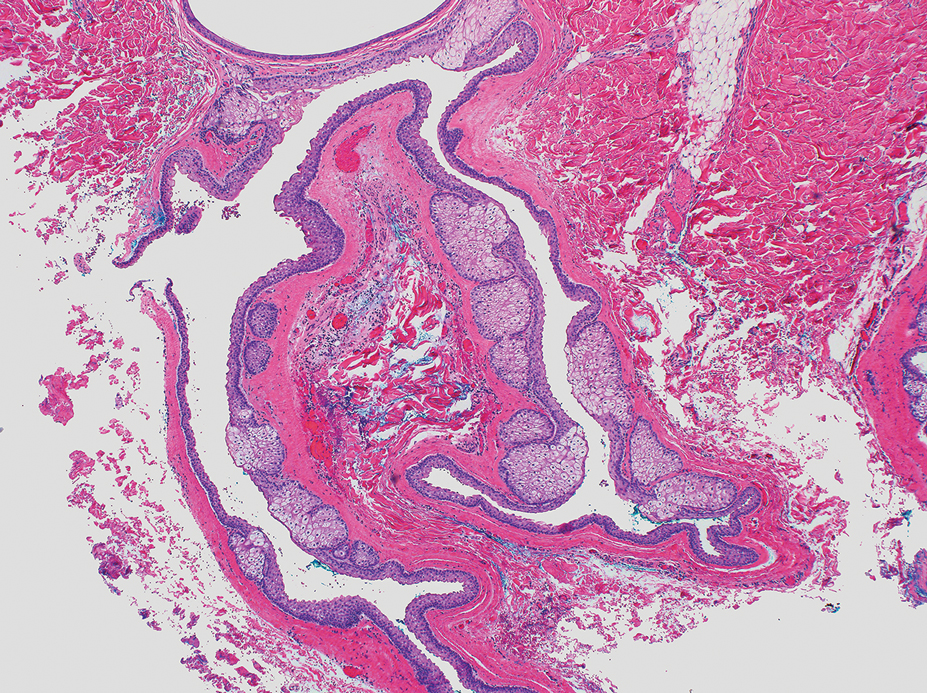

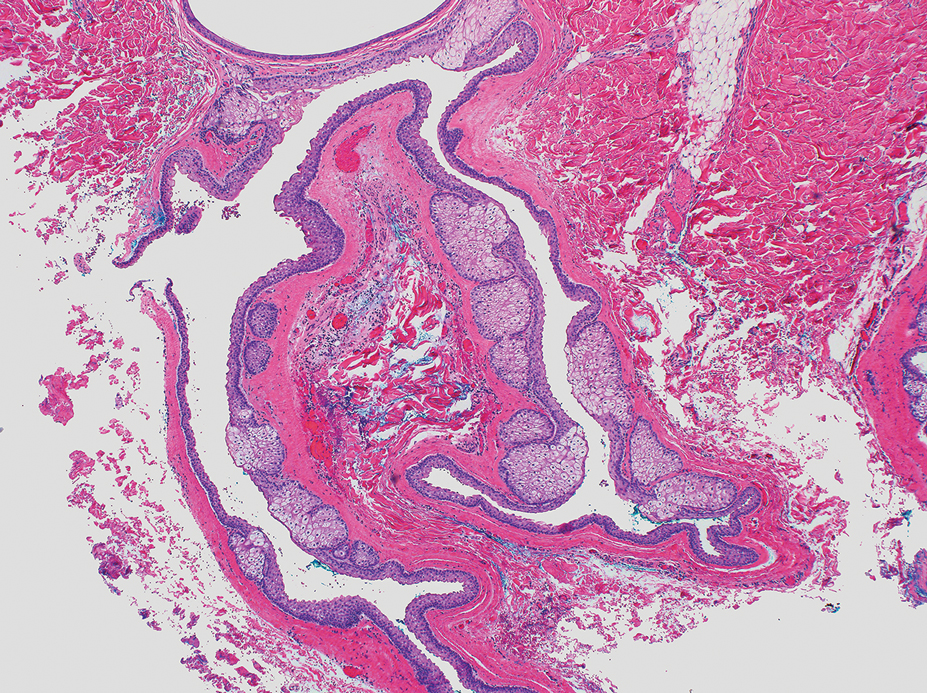

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

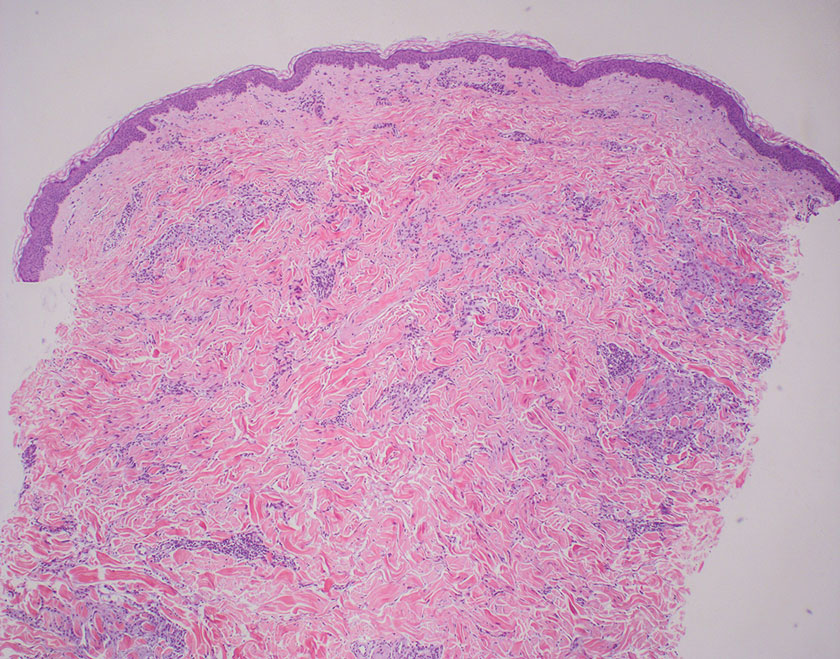

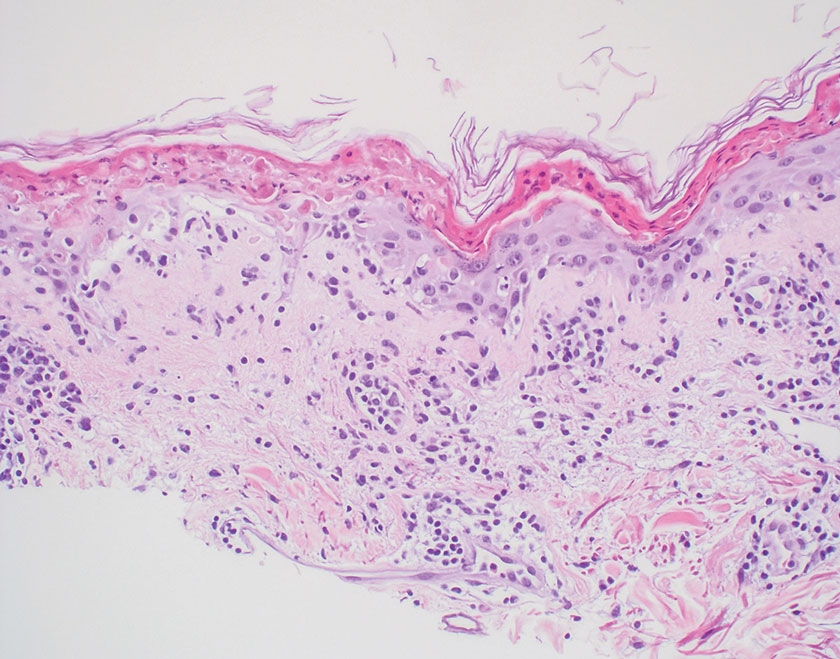

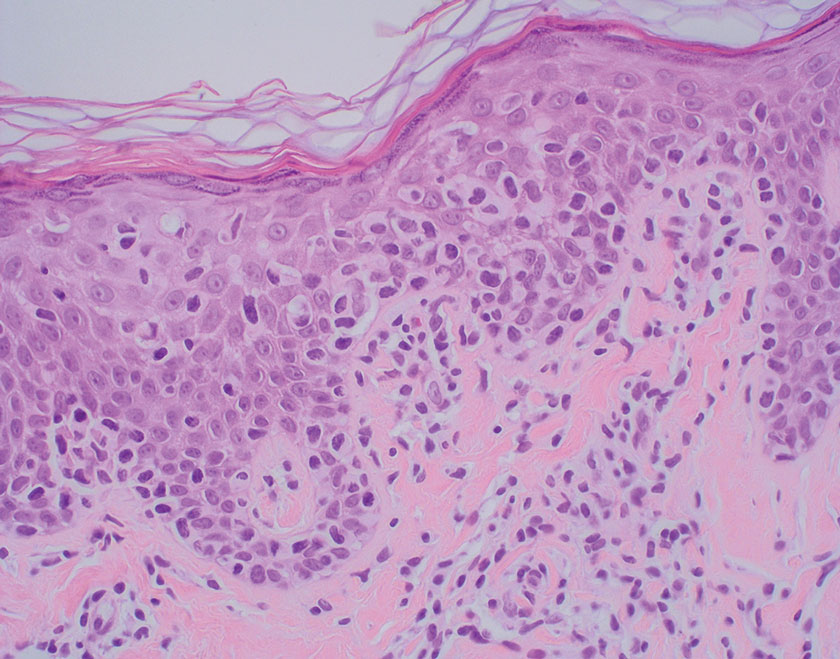

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

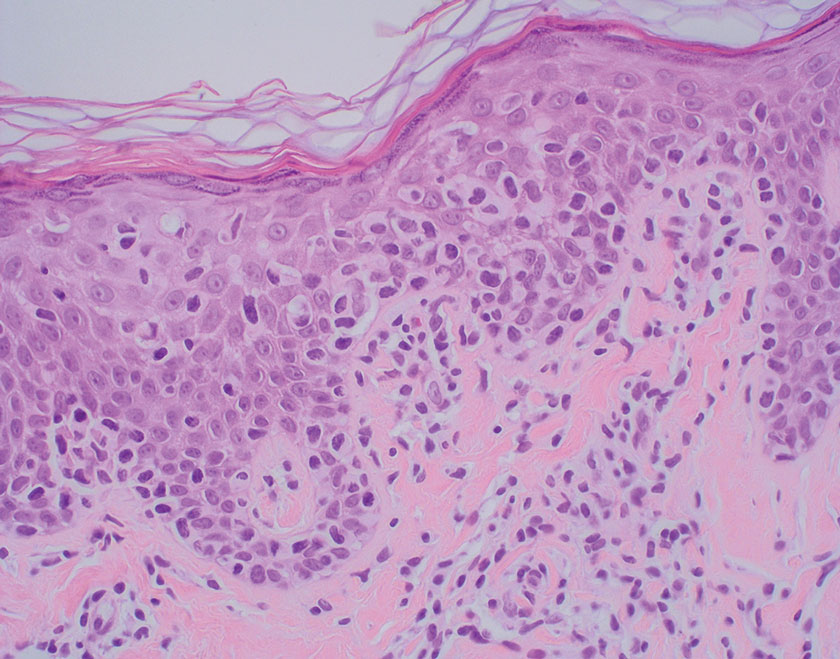

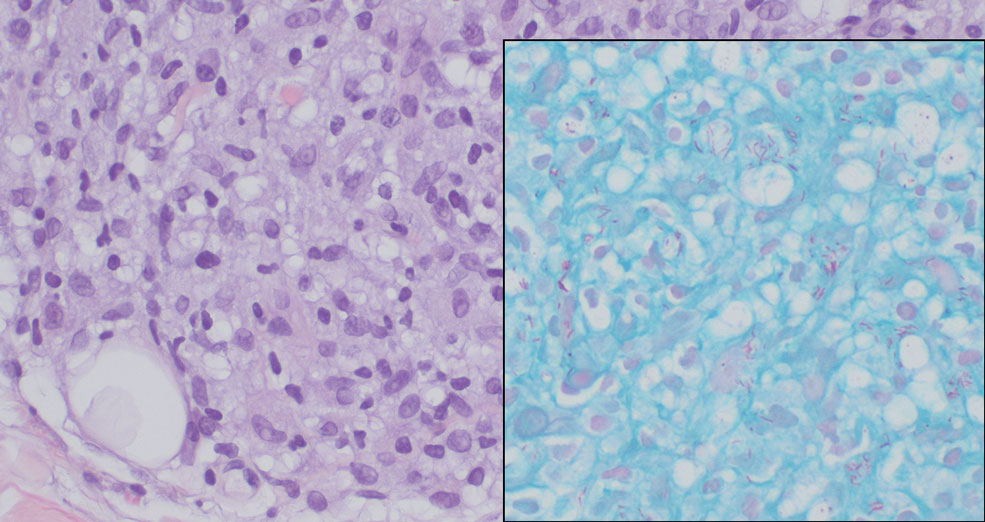

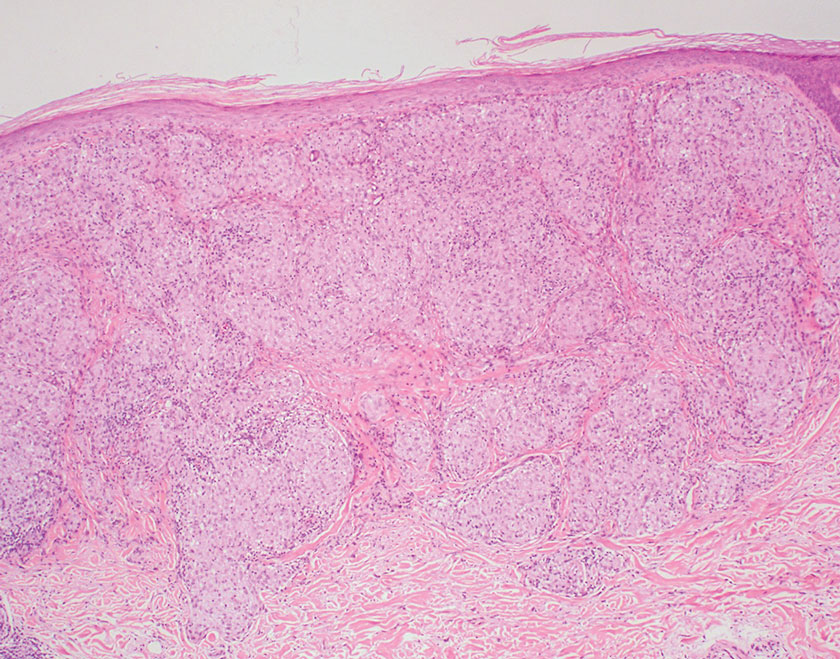

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

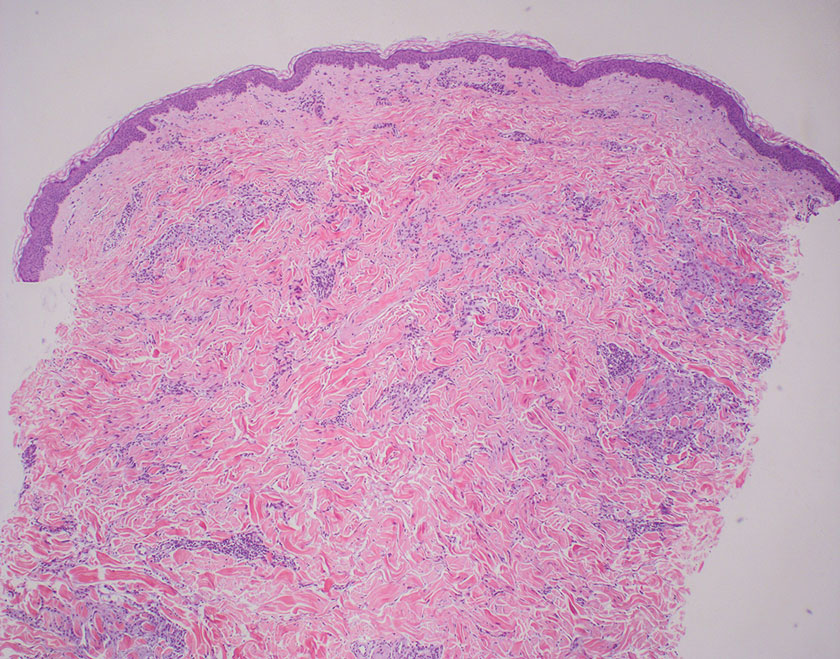

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

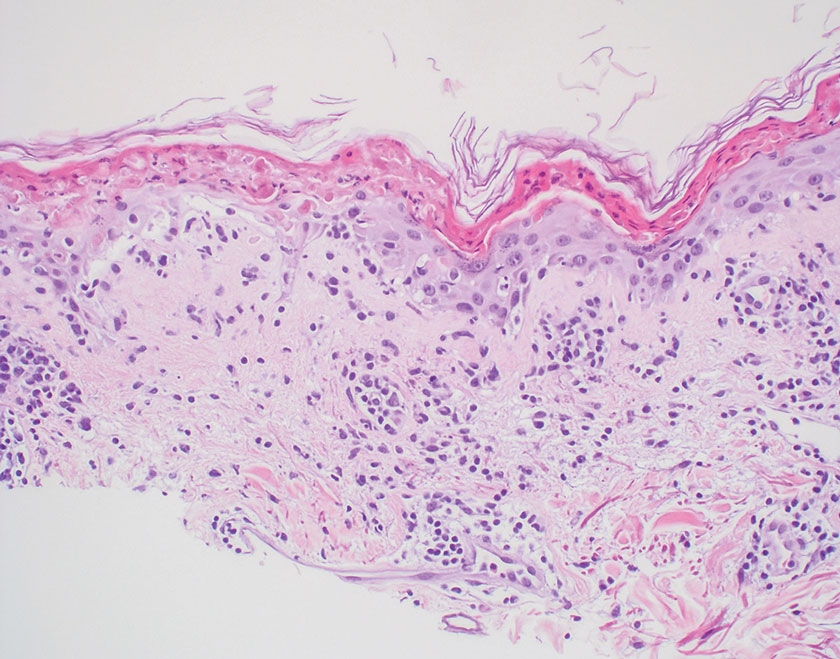

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

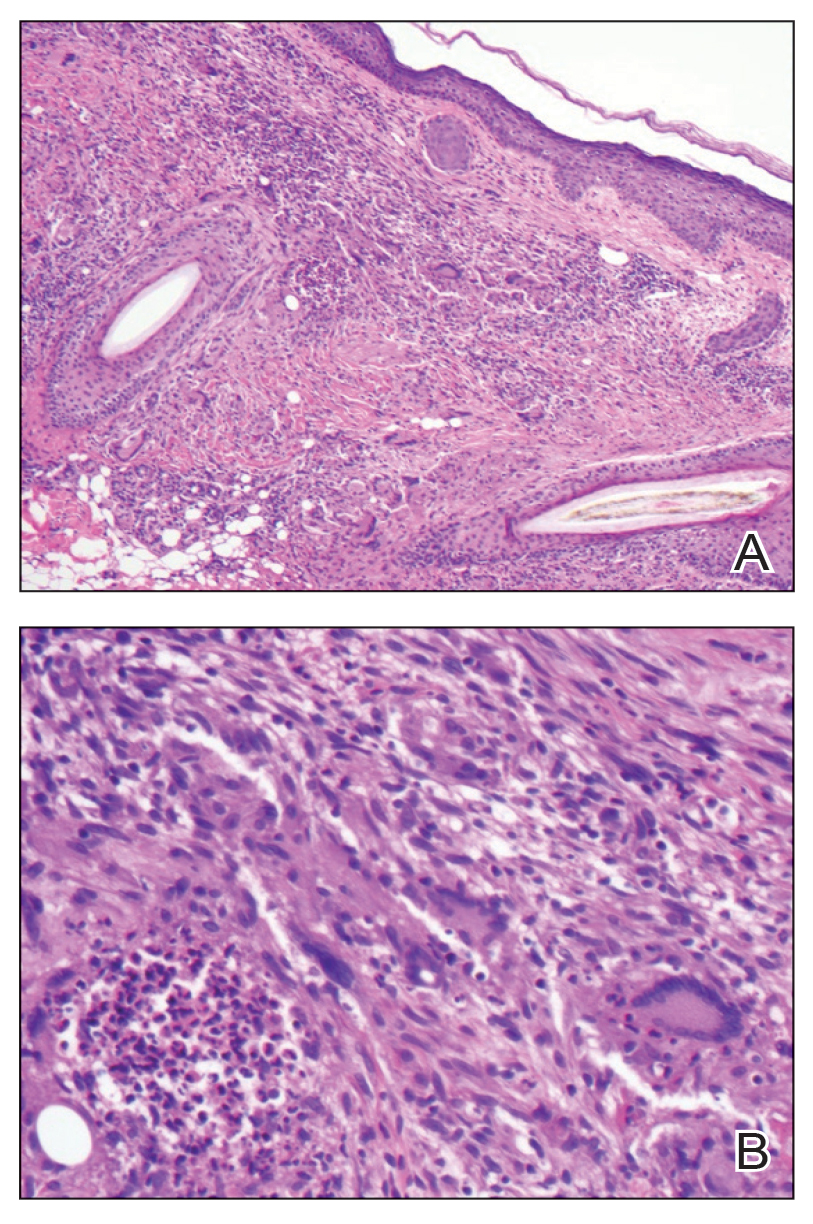

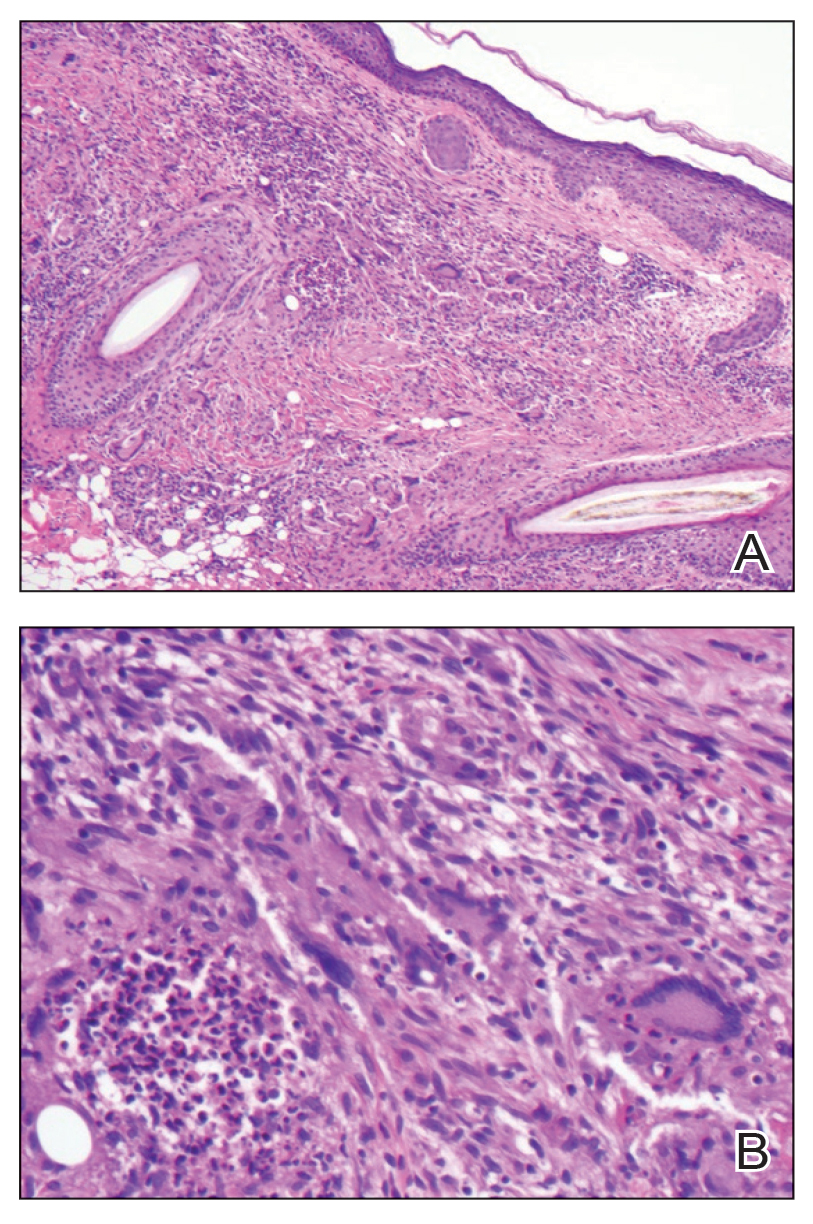

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

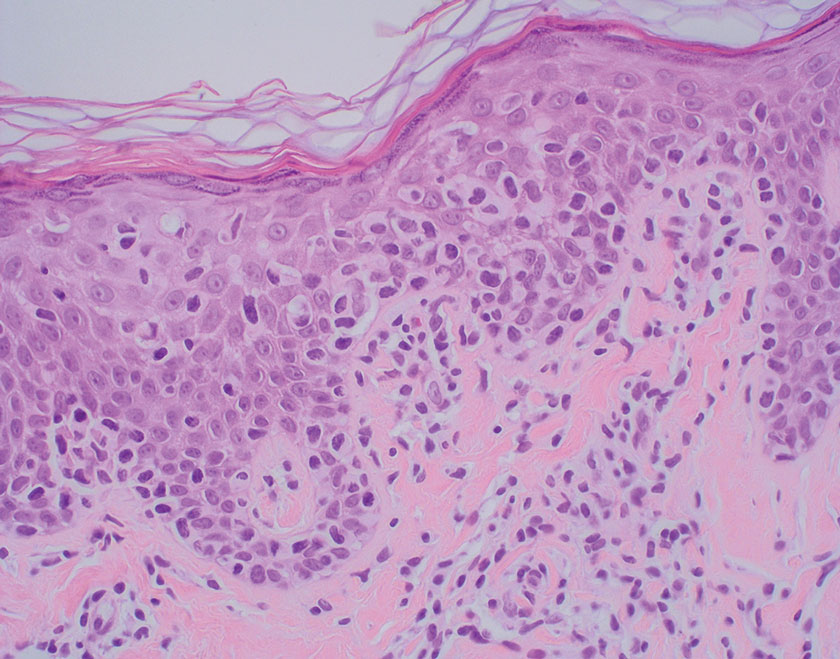

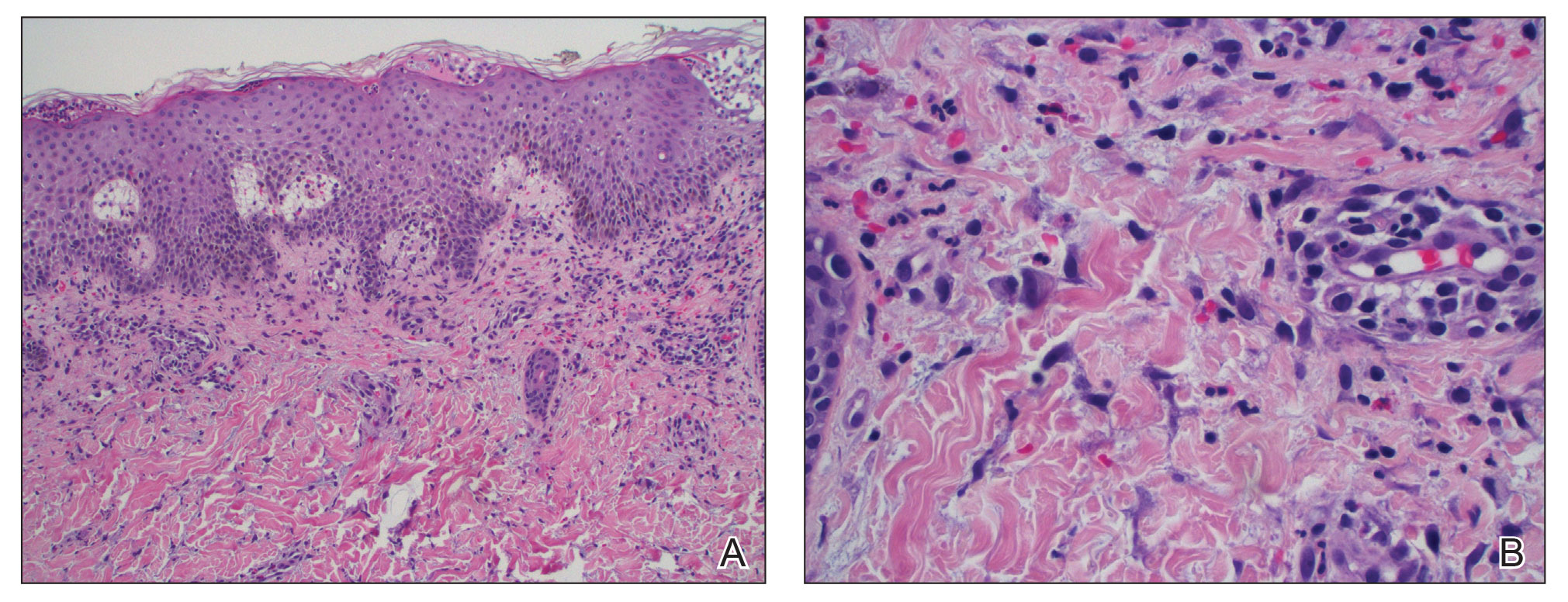

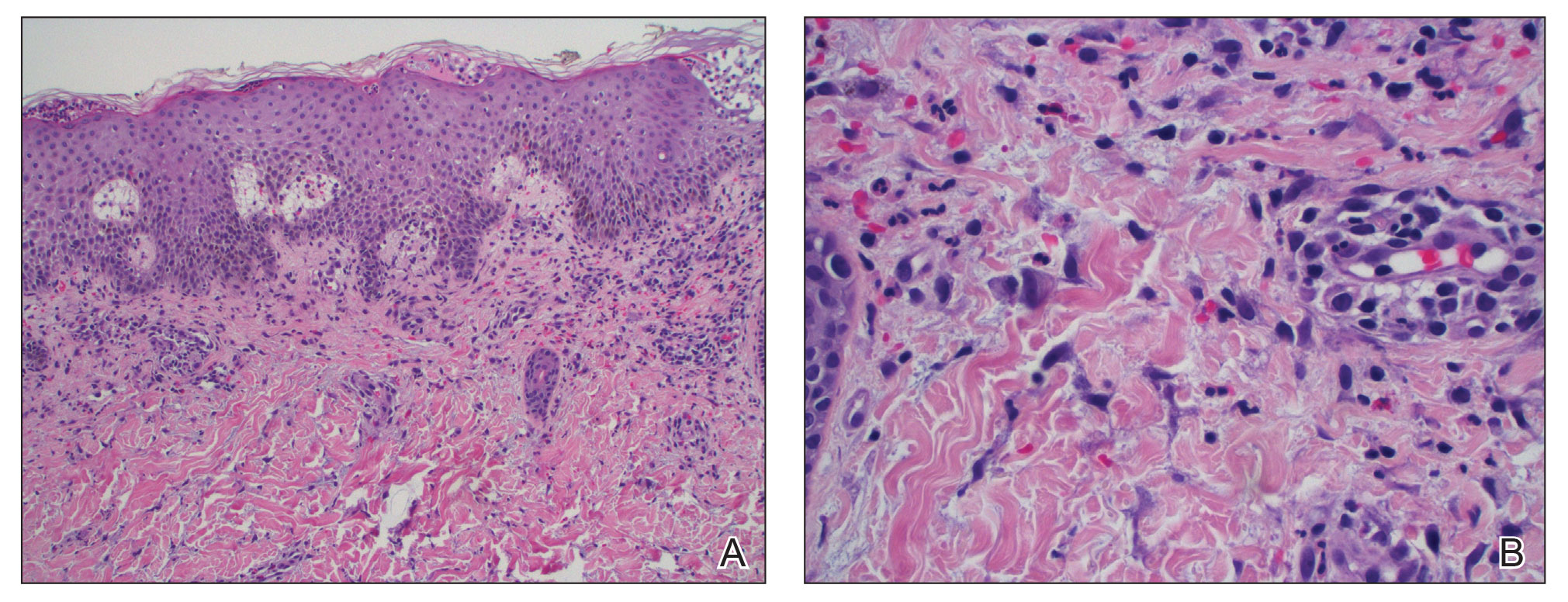

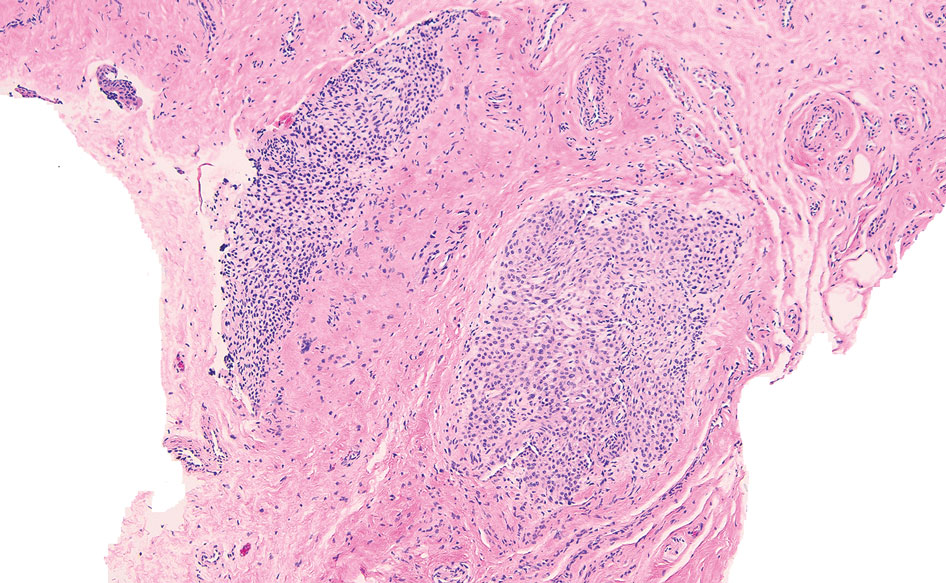

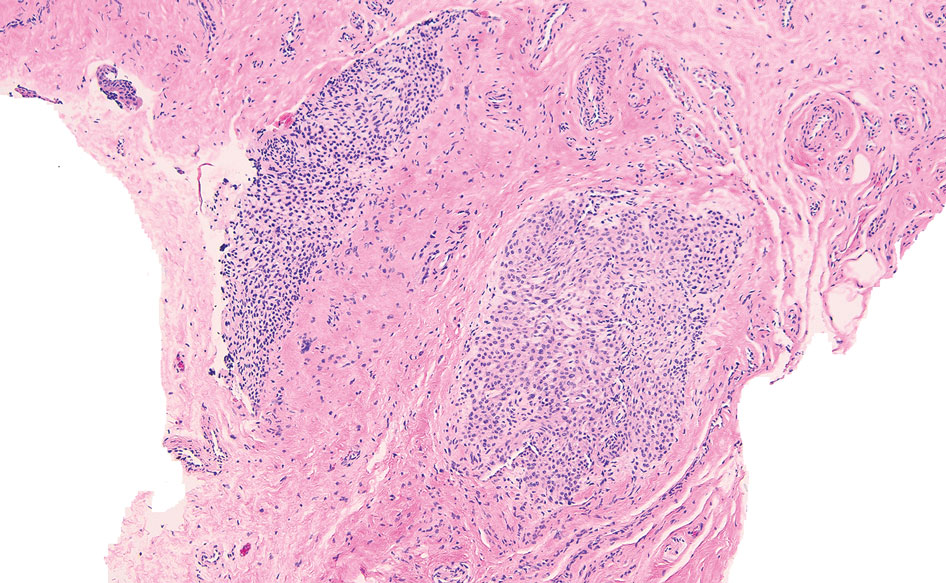

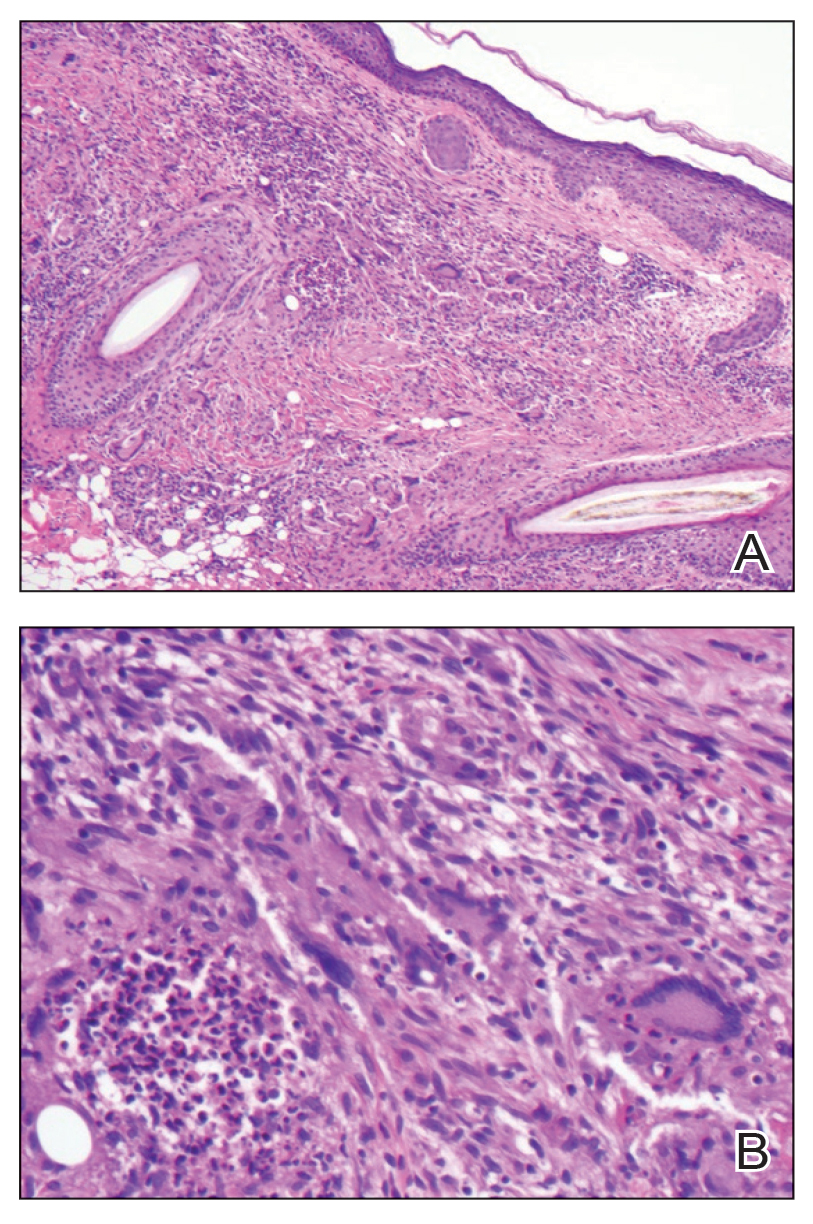

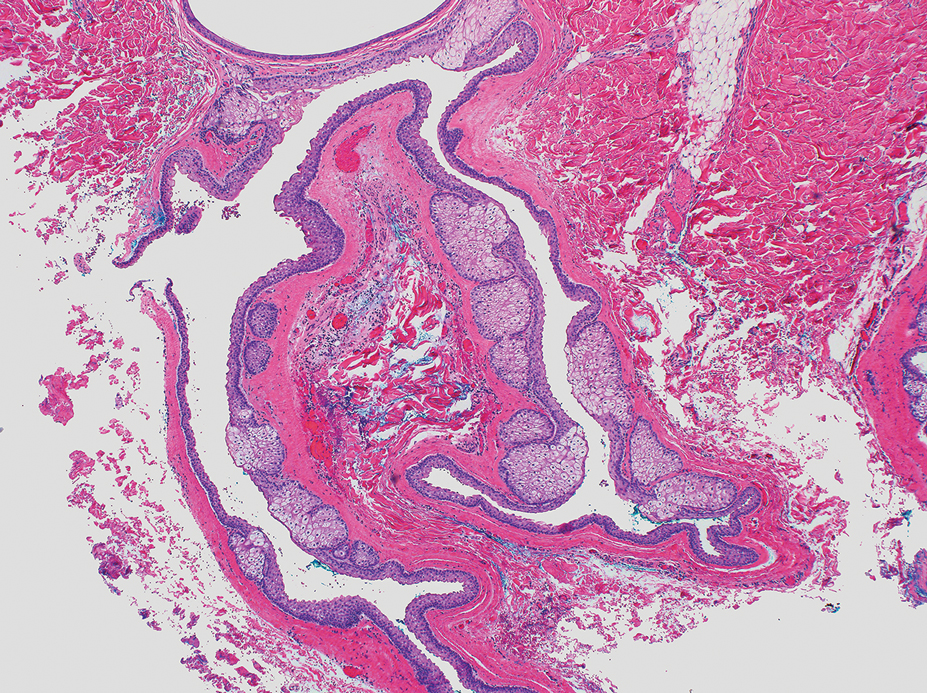

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

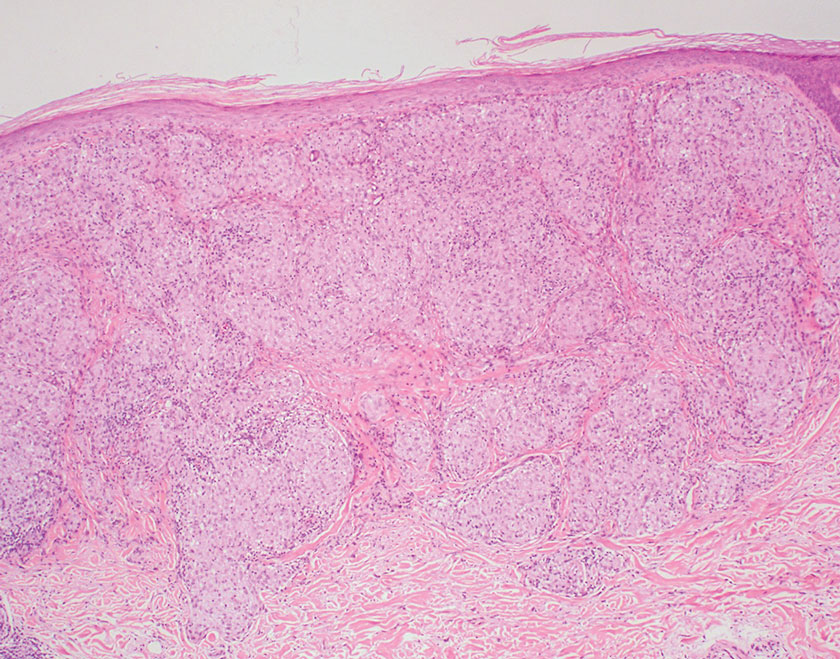

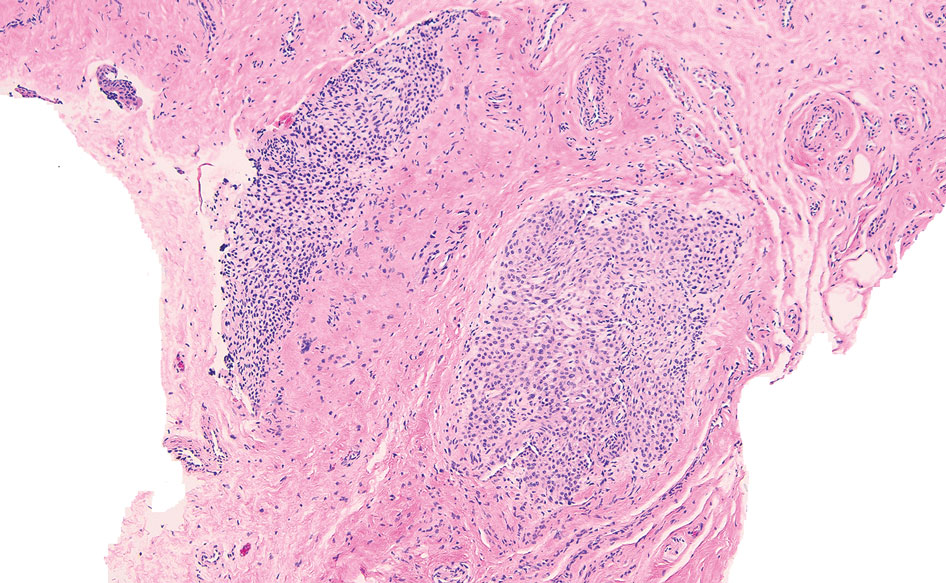

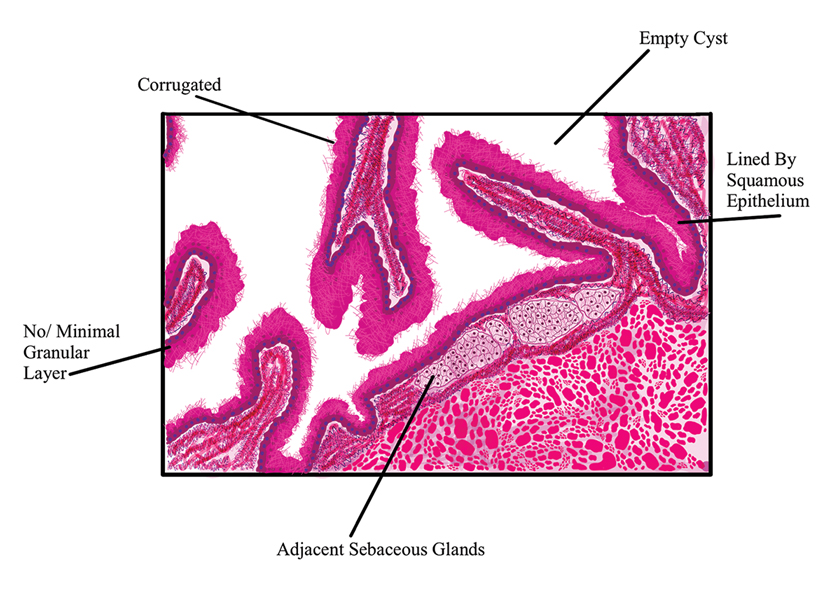

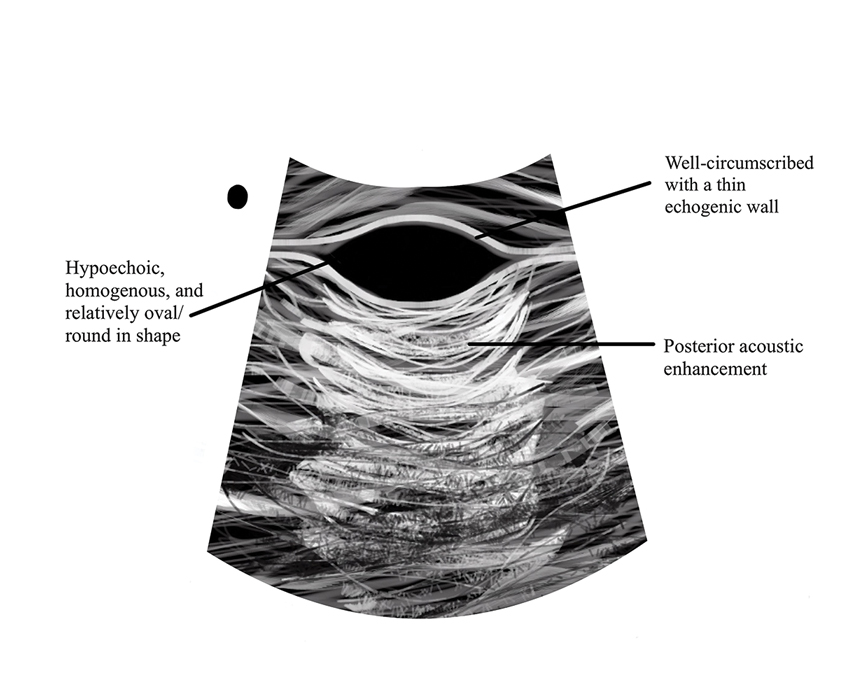

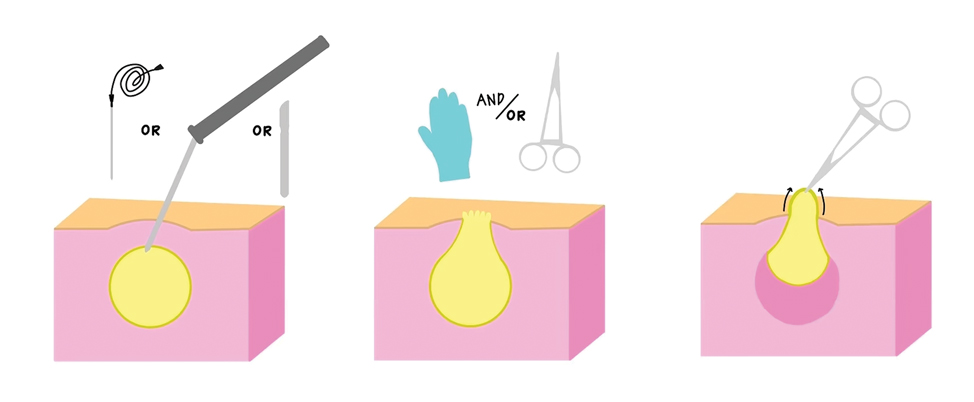

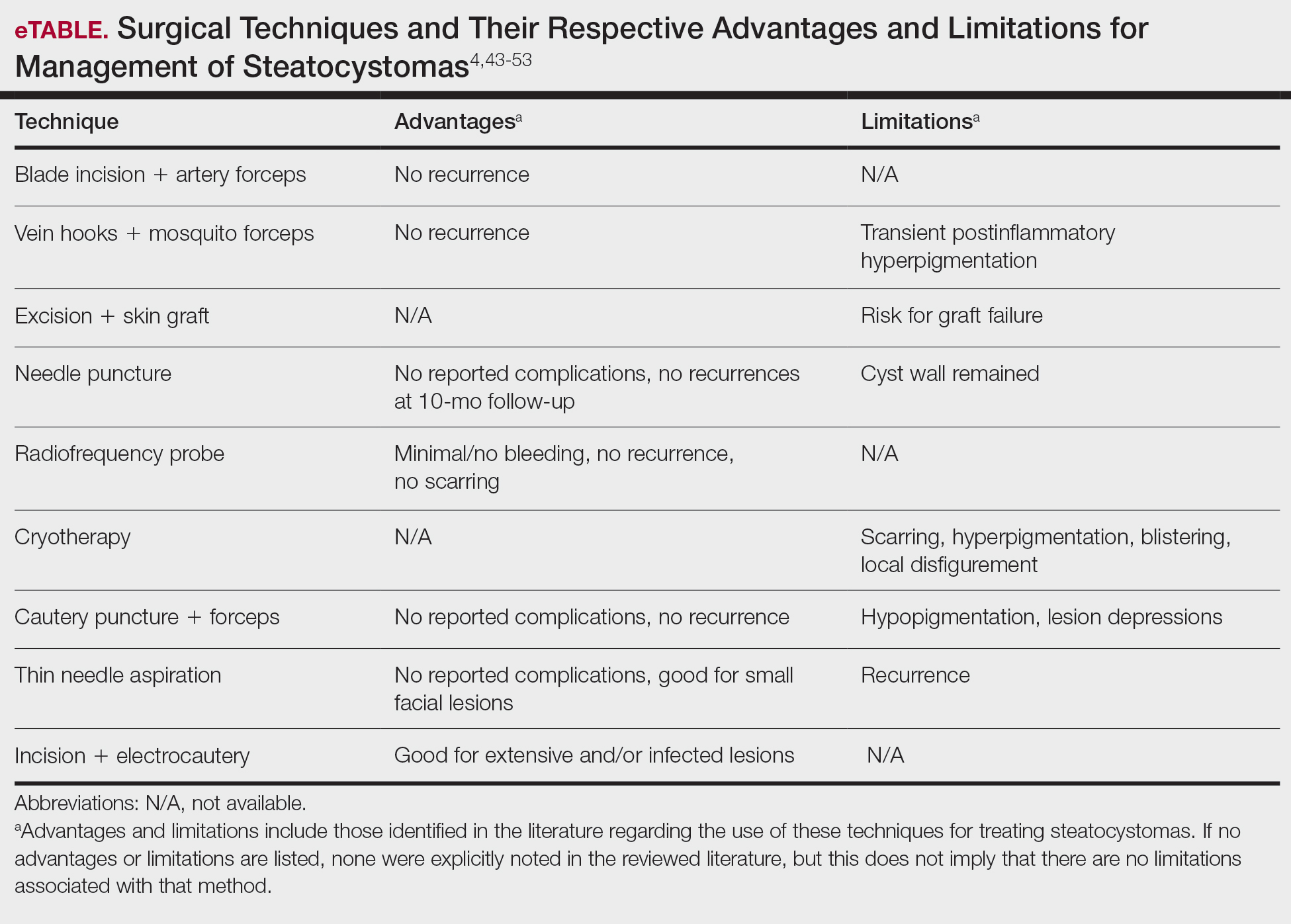

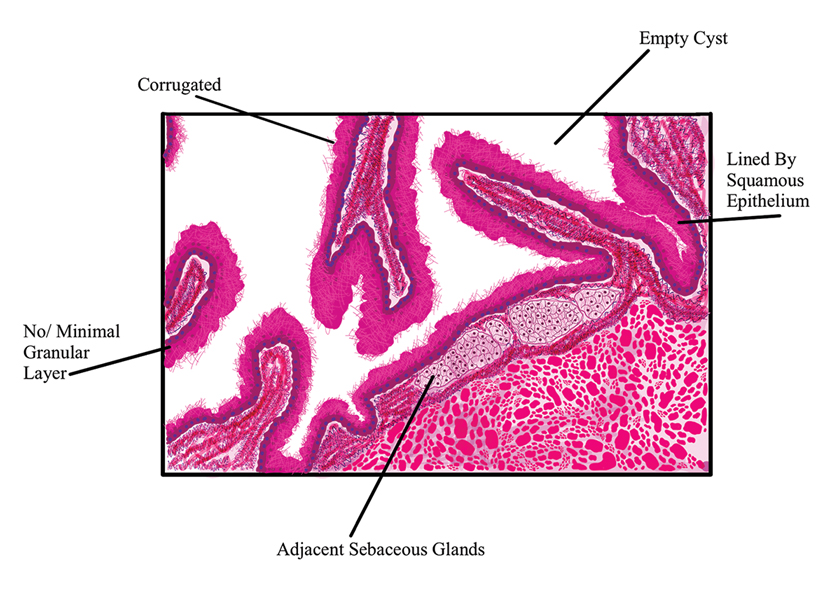

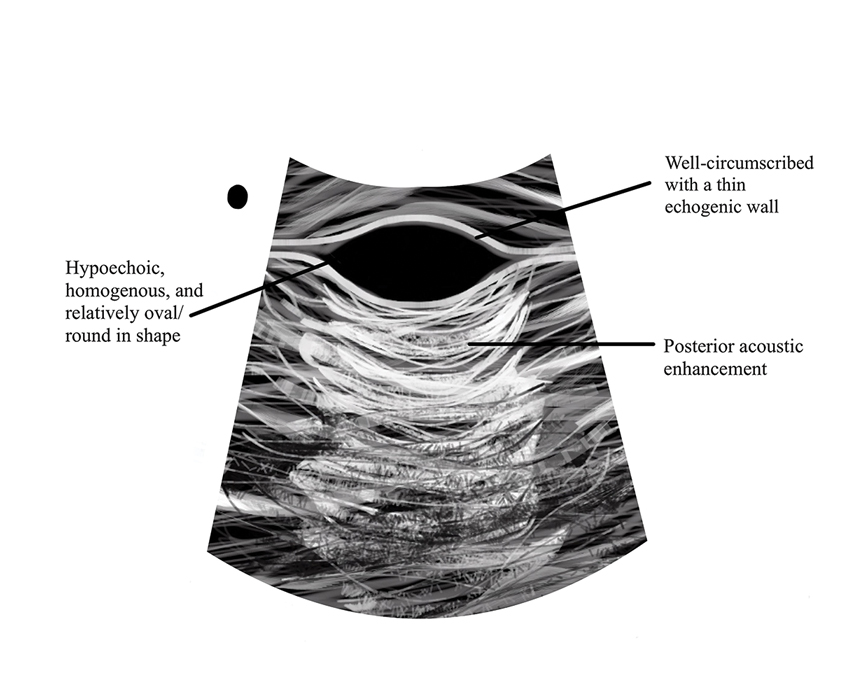

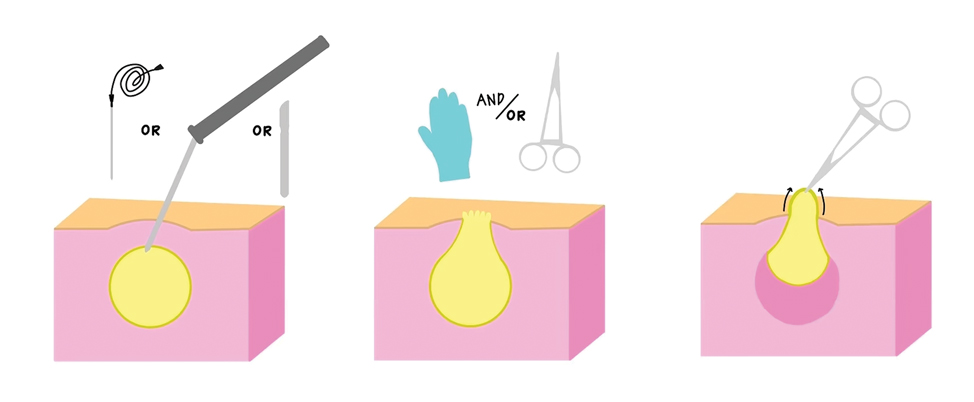

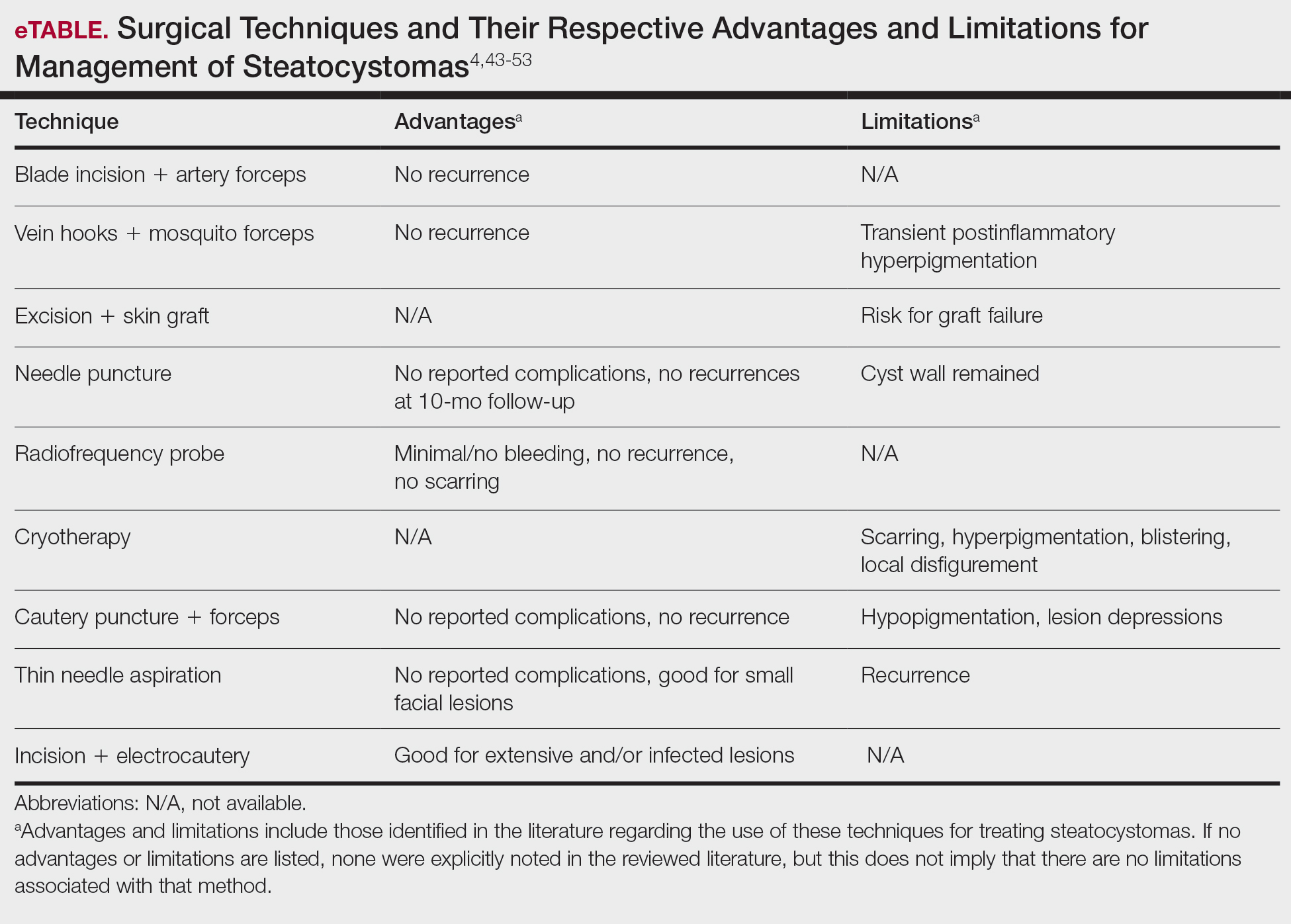

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

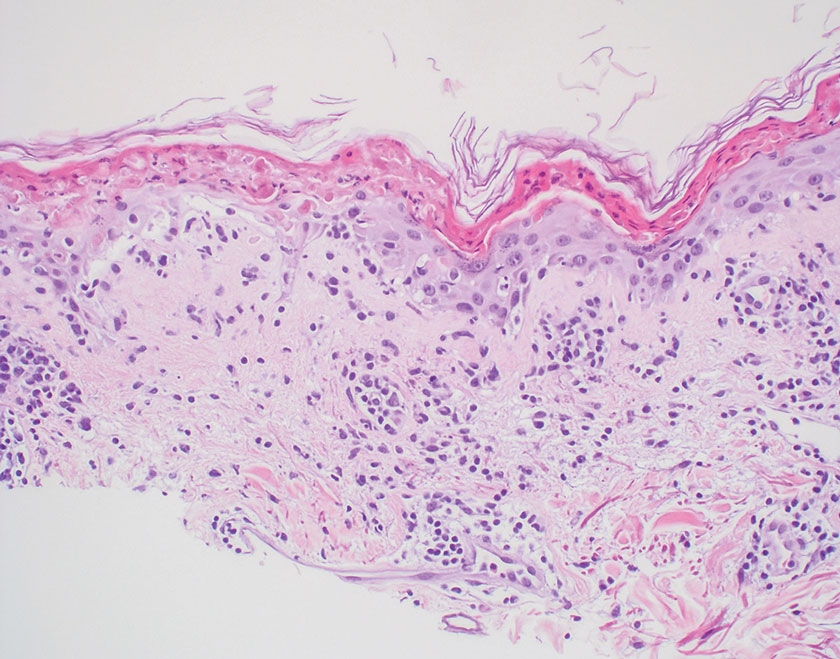

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

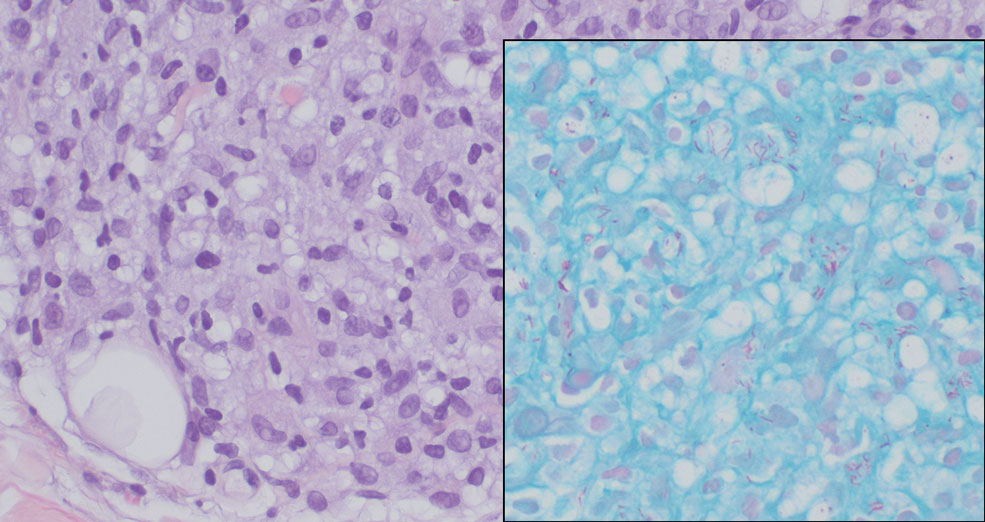

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

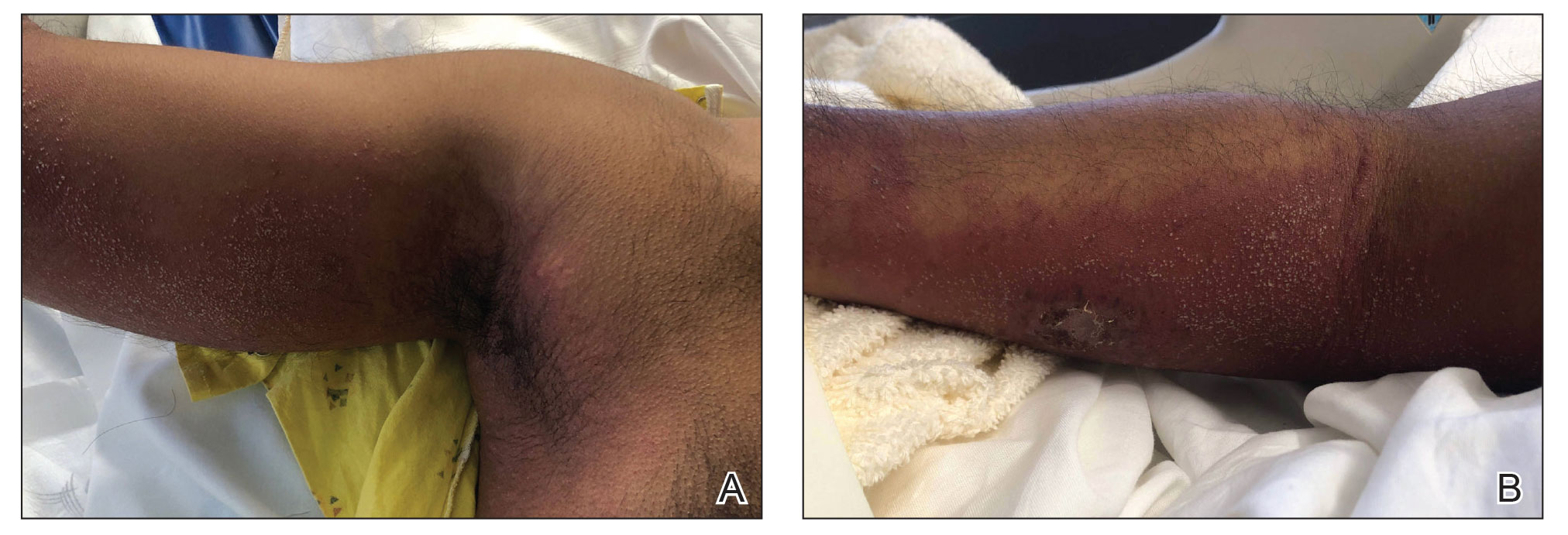

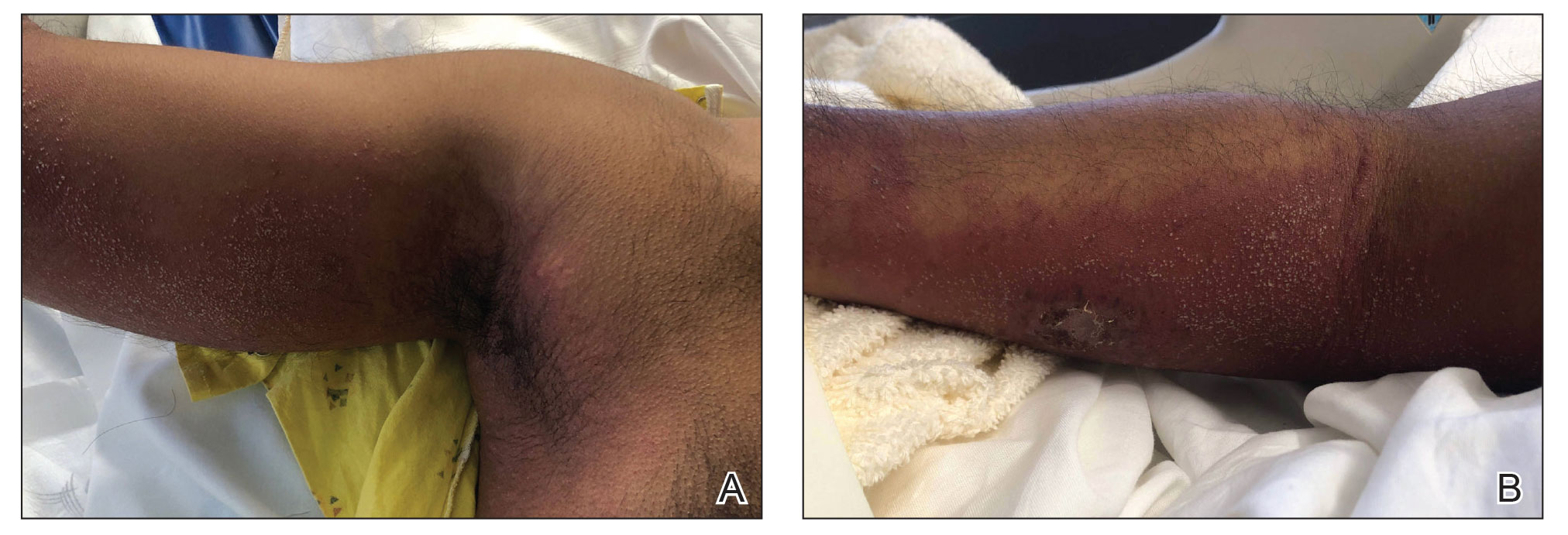

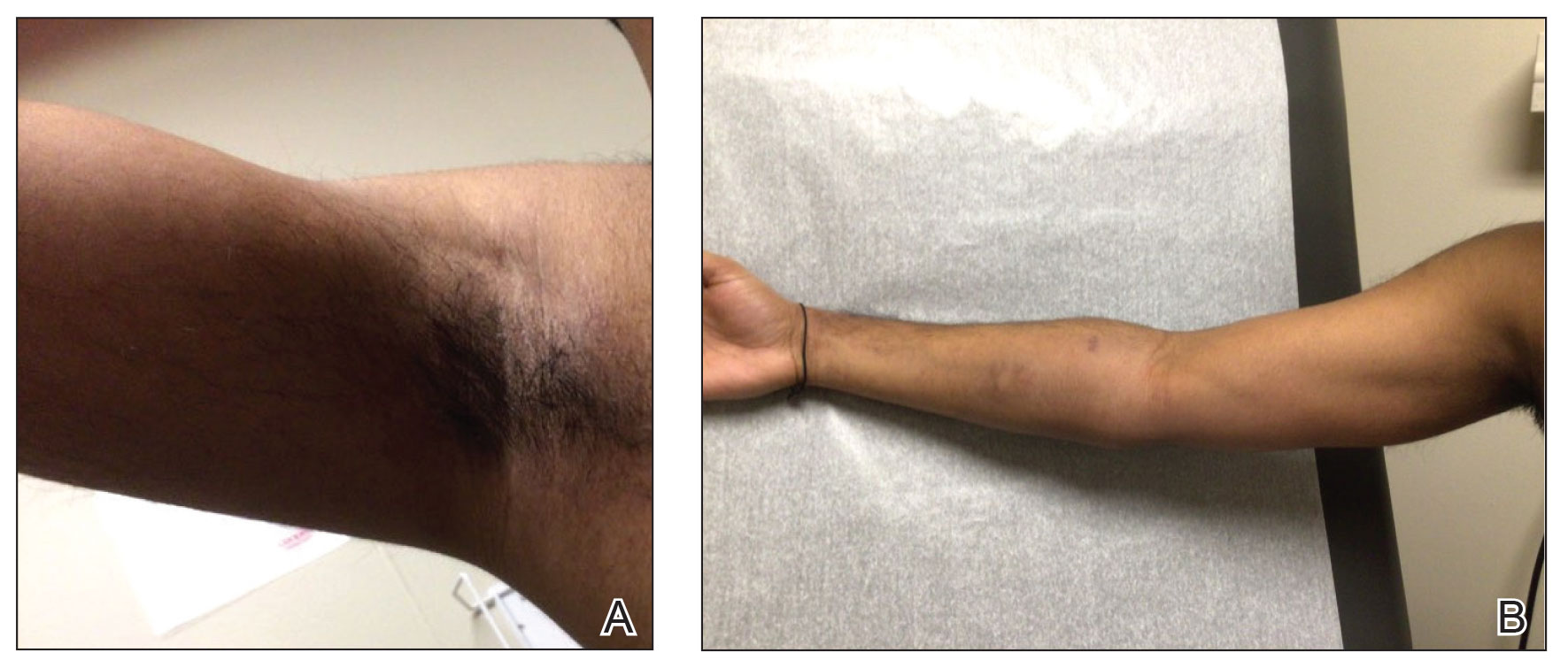

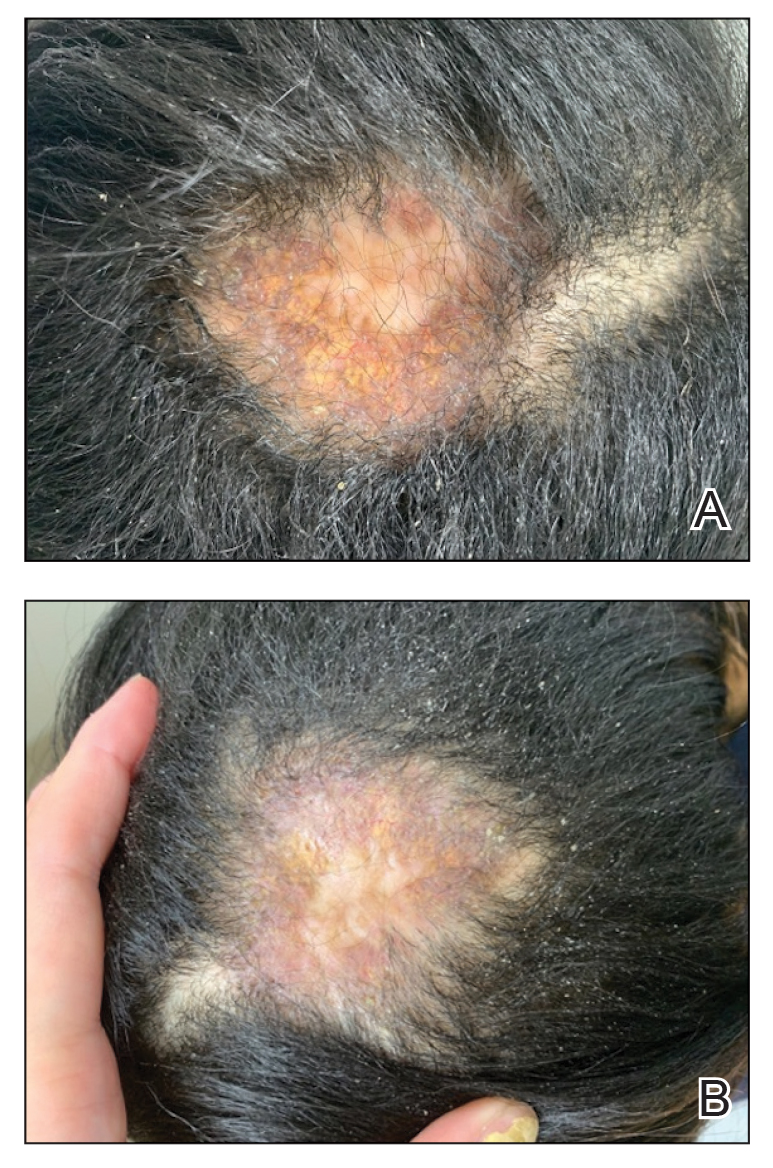

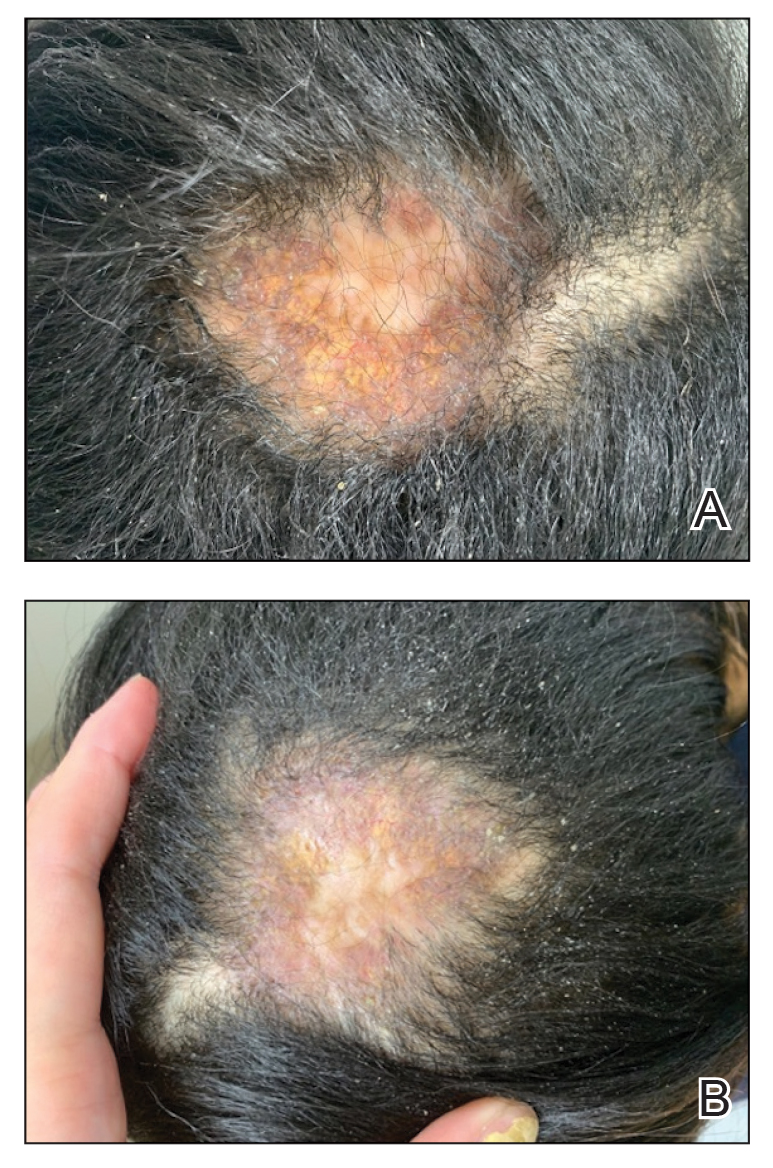

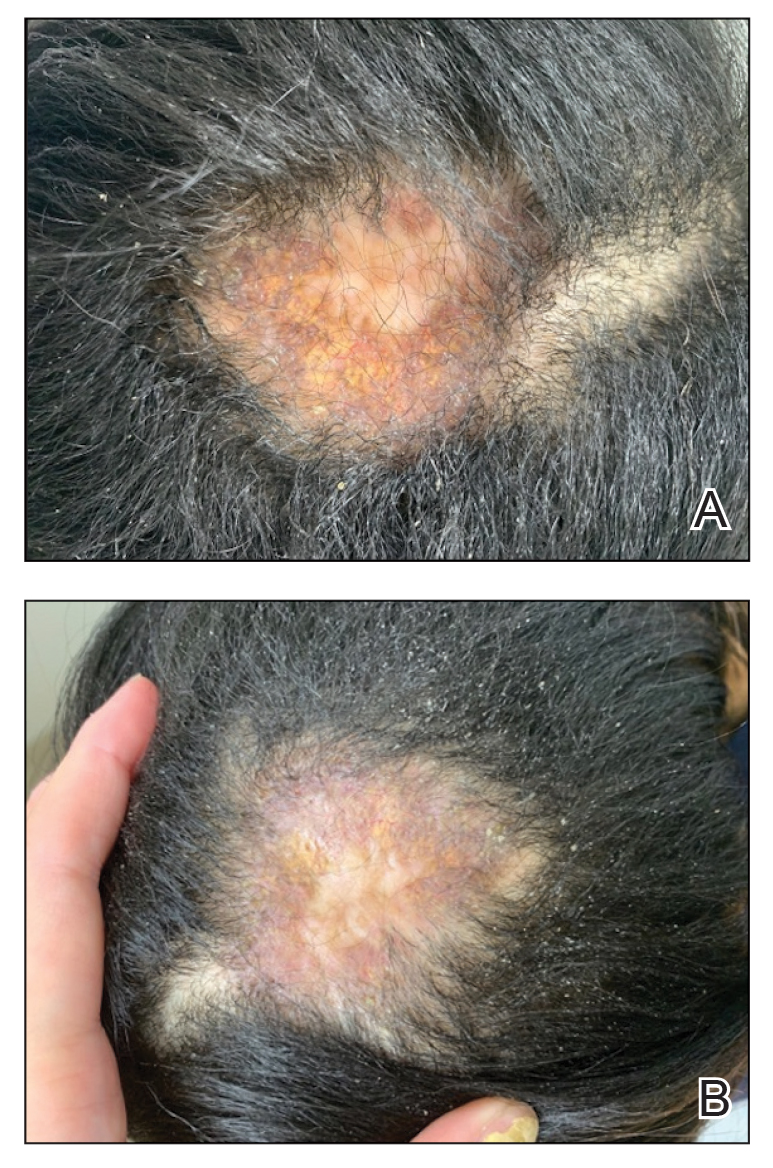

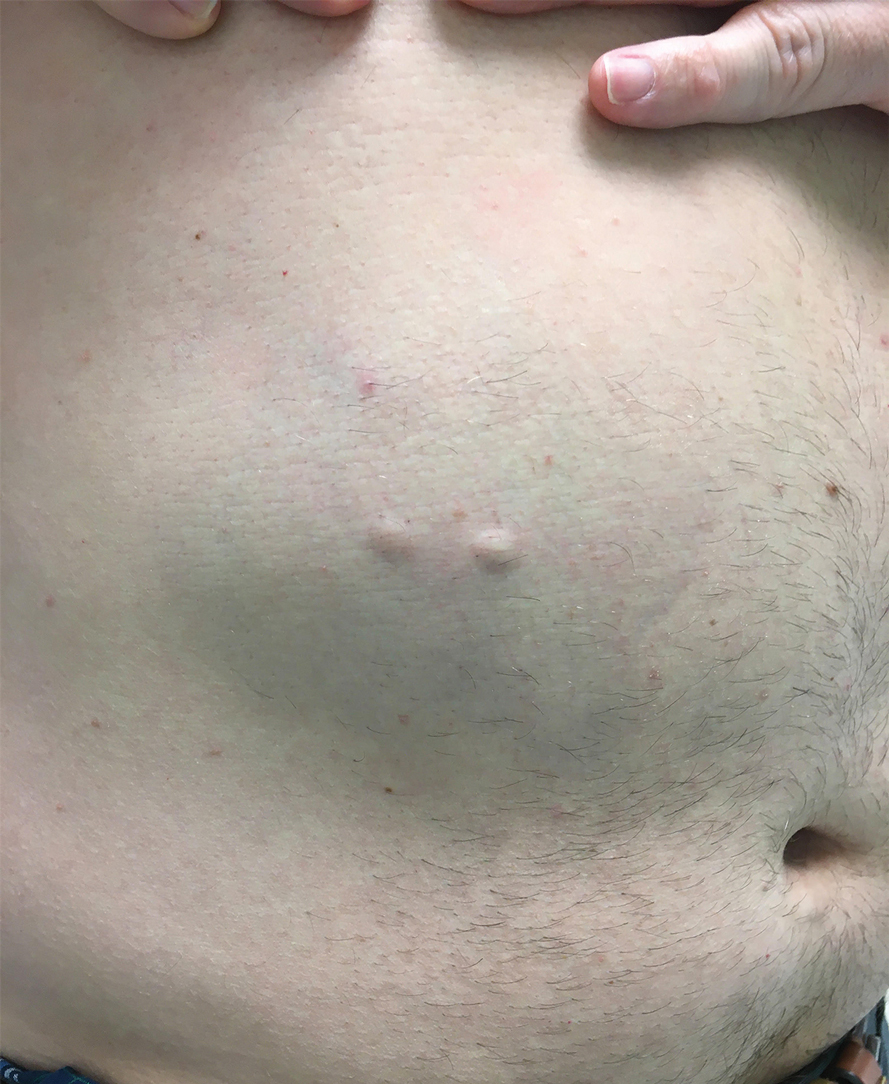

A 44-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a widespread red, itchy, bumpy rash of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed smooth, coalescing, erythematous and edematous plaques on the face (notably the forehead, malar cheeks, and nose), back, arms, and legs. Several plaques on the back had central hypopigmentation. The patient also reported numbness and weakness in the fingers and toes, and hypoesthesia within the lesions was noted. A biopsy of one of the lesions on the left ventral forearm was performed.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

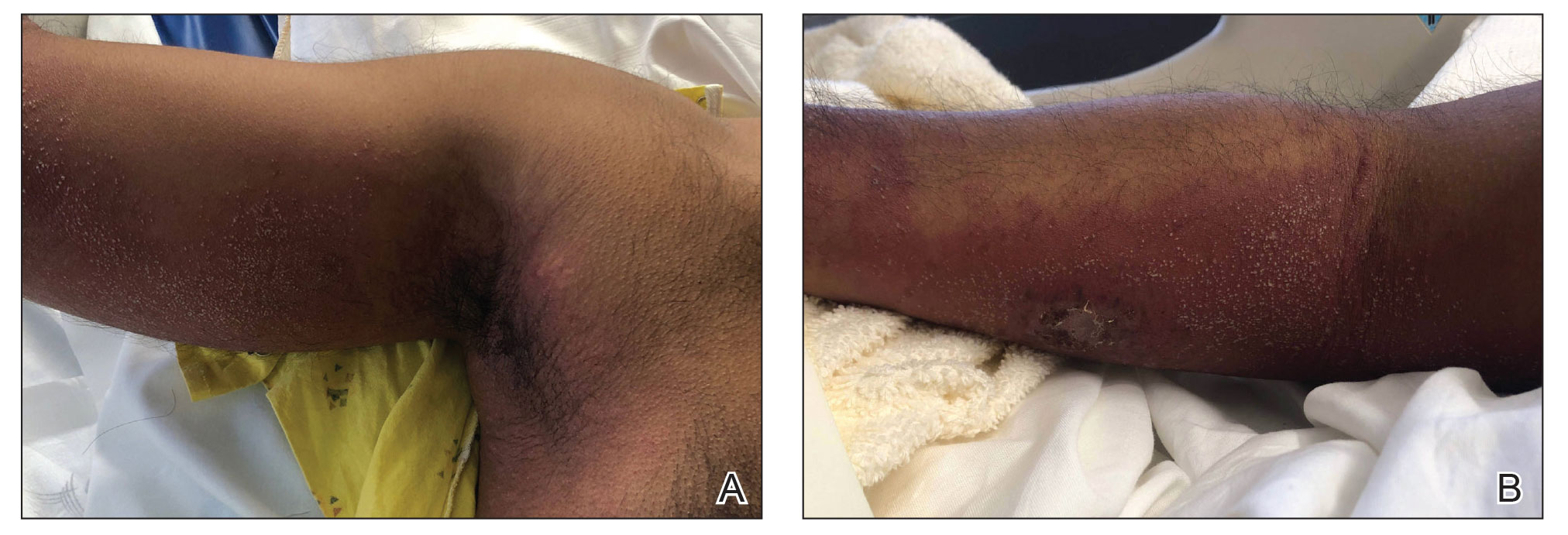

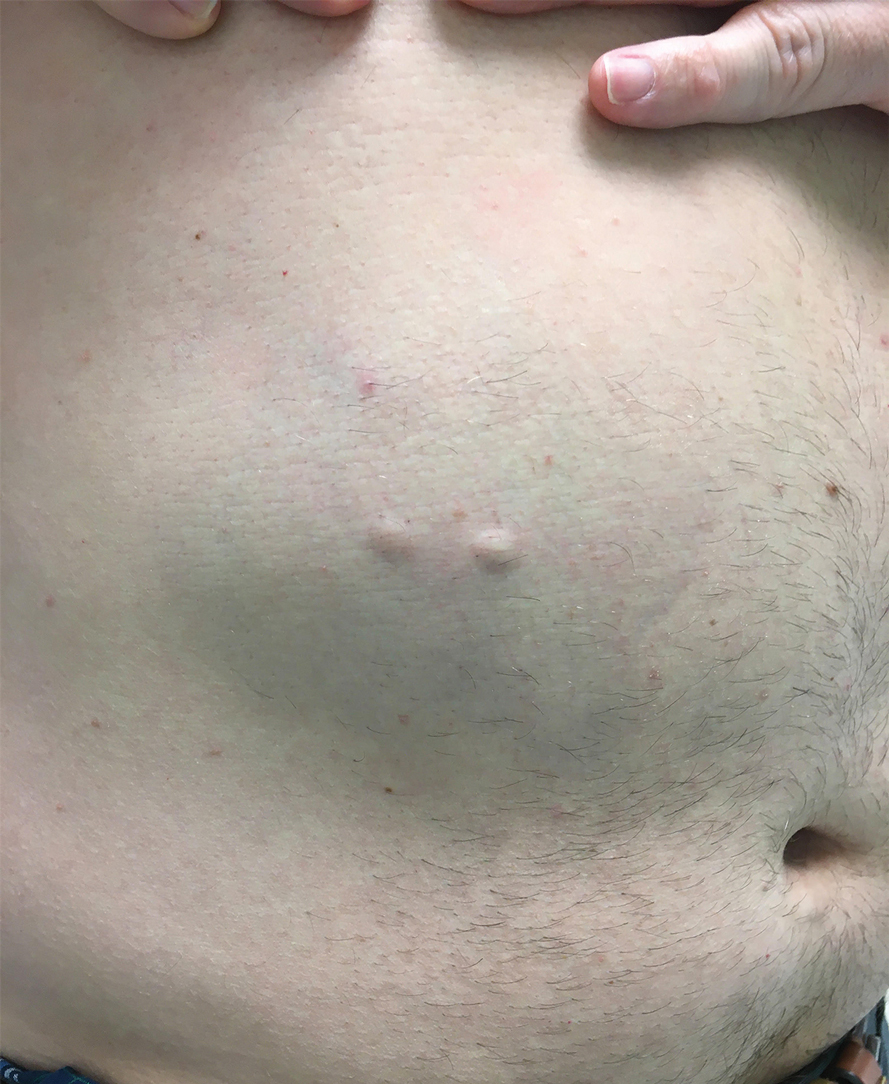

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

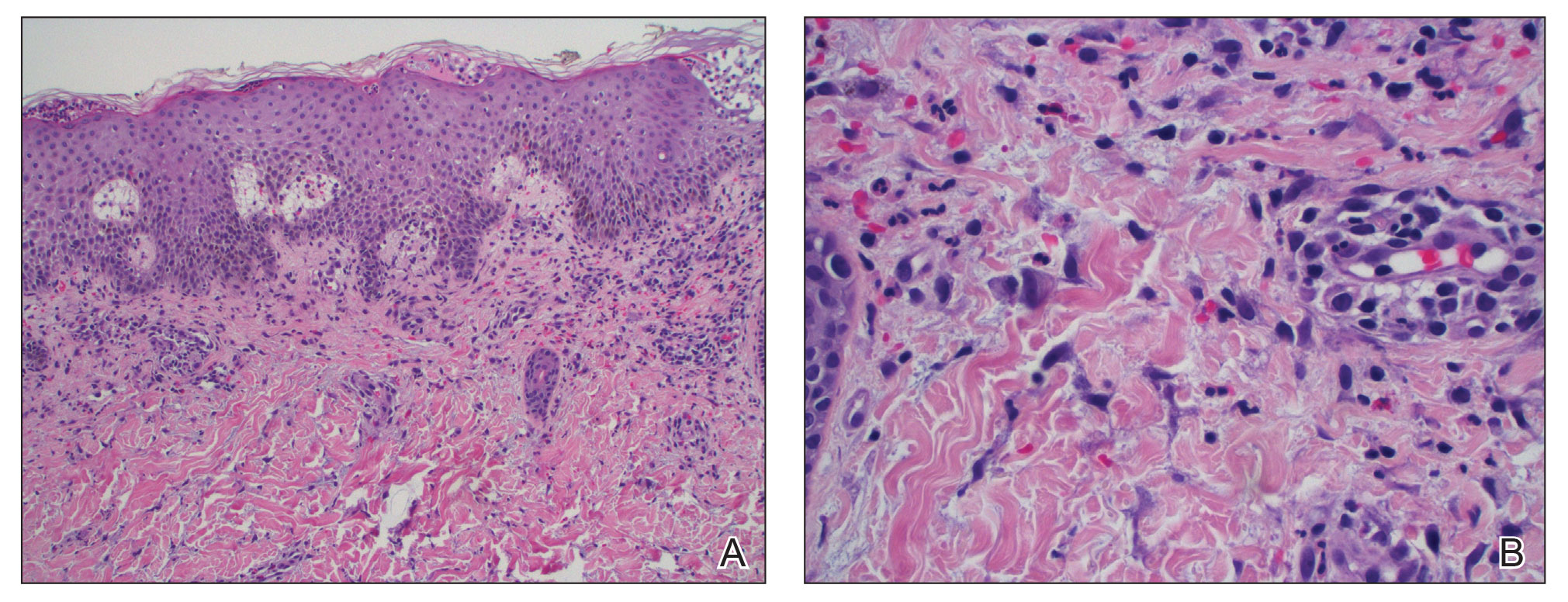

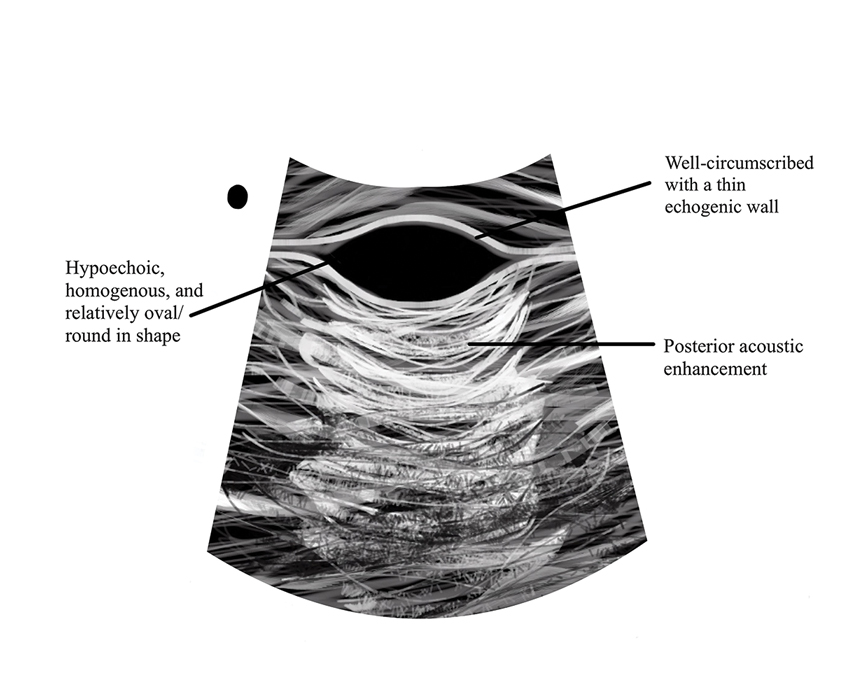

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

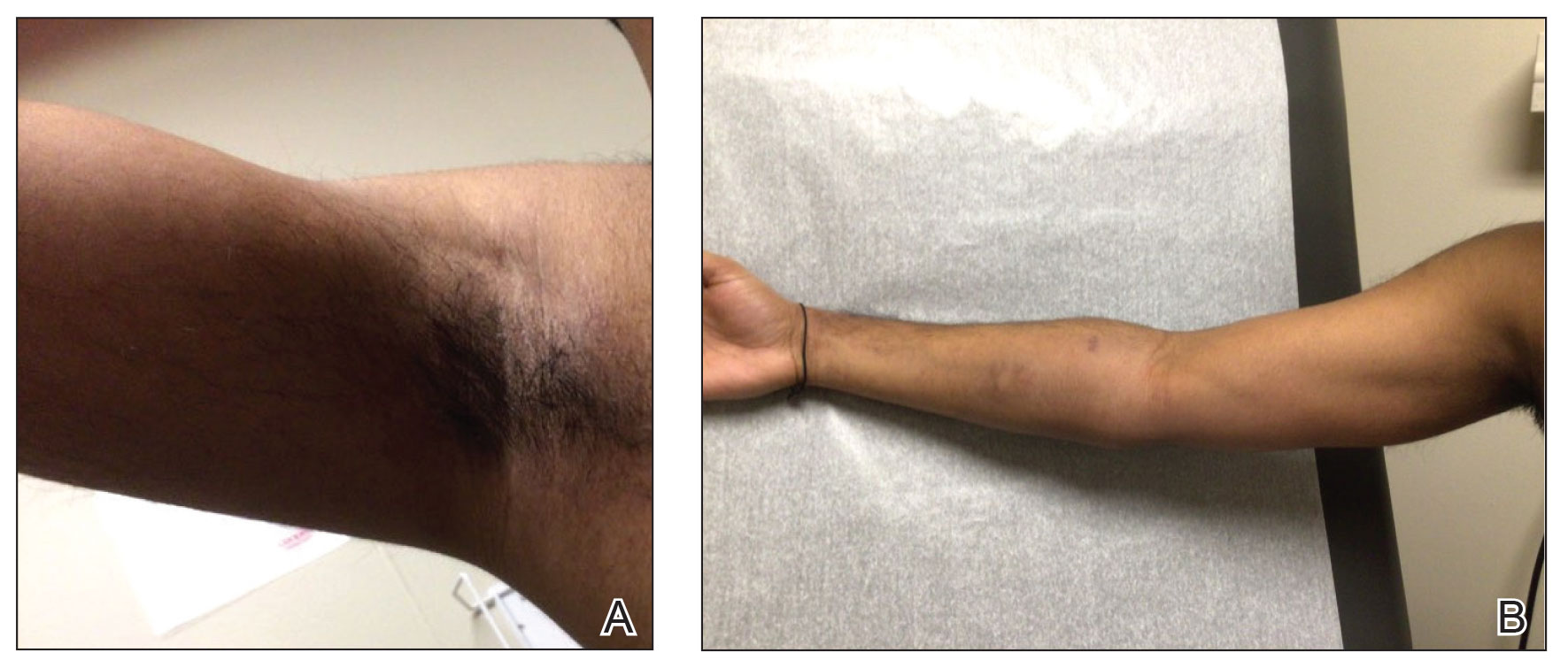

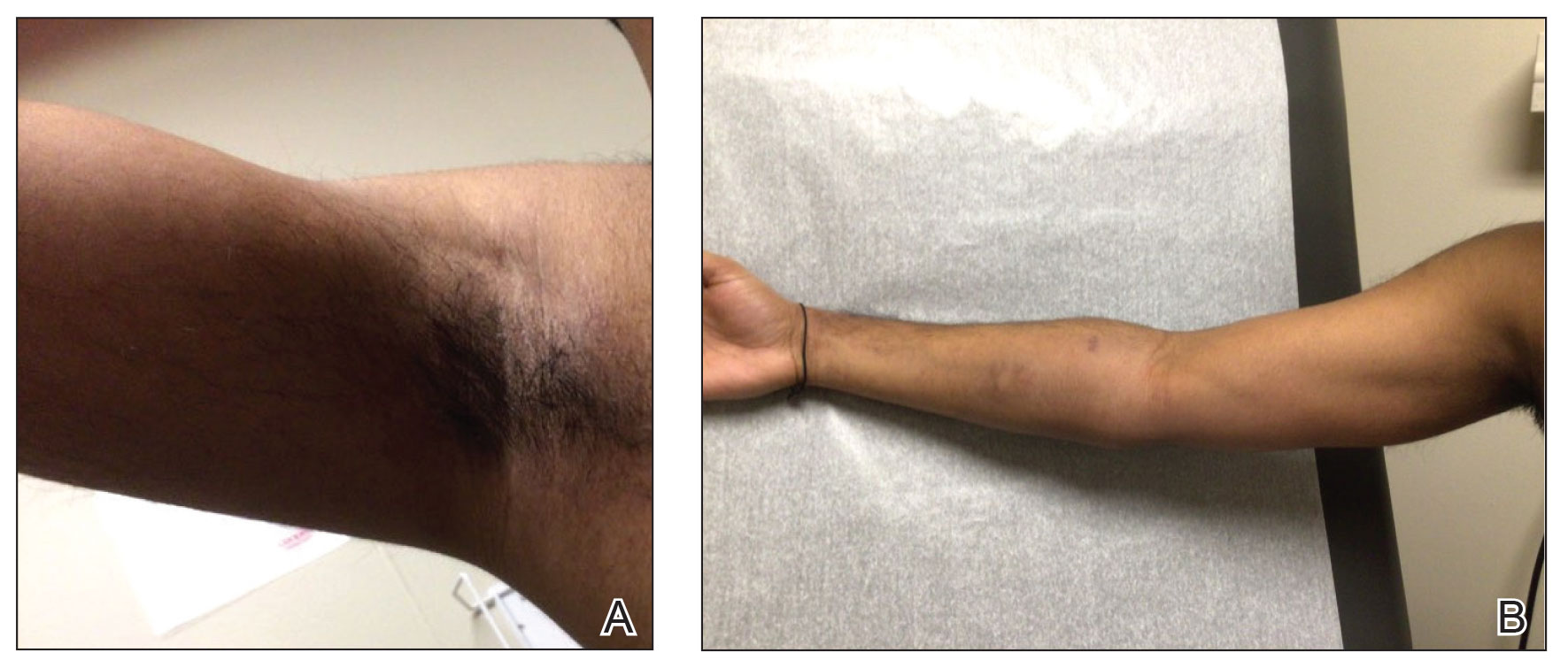

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.