User login

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Mepolizumab improves asthma after 1 year despite comorbidities

Adults with asthma who were newly prescribed mepolizumab showed significant improvement in symptoms after 1 year regardless of comorbidities, based on data from 822 individuals.

Comorbidities including chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps (CRSwNP), gastroesophageal reflux disease GERD), anxiety and depression, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) are common in patients with severe asthma and add to the disease burden, wrote Mark C. Liu, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Some comorbidities, such as CRSwNP, share pathophysiological mechanisms with severe asthma, with interleukin-5 (IL-5),” and treatments targeting IL-5 could improve outcomes, they said.

In the real-world REALITI-A study, mepolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5, significantly reduced asthma exacerbation and oral corticosteroid use in severe asthma patients, they said.

To assess the impact of mepolizumab on patients with comorbidities, the researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of 822 adults with severe asthma, including 321 with CRSwNP, 309 with GERD, 203 with depression/anxiety, and 81 with COPD. The findings were published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

The main outcomes were the rate of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (CSEs) between the 12 months before and after mepolizumab initiation, and the changes from baseline in the daily maintenance use of oral corticosteroids (OCS).

Across all comorbidities, the rate of CSEs decreased significantly from the pretreatment period to the follow-up period, from 4.28 events per year to 1.23 events per year.

“A numerically greater reduction in the rate of CSEs was reported for patients with versus without CRSwNP, whereas the reverse was reported for patients with versus without COPD and depression/anxiety, although the confidence intervals were large for the with COPD subgroup,” the researchers wrote.

The median maintenance dose of oral corticosteroids decreased by at least 50% across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment; patients with CRSwNP had the greatest reduction (83%).

In addition, scores on the Asthma Control Questionnaire–5 decreased by at least 0.63 points, and least squared (LS) mean changes in forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) increased from baseline across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment by at least 74 mL.

Although patients with versus without CRSwNP had greater improvements, patients without GERD, depression/anxiety, and COPD had greater improvements than did those without the respective conditions with the exception of greater FEV1 improvement in patients with vs. without COPD.

“Patients with severe asthma and comorbid CRSwNP are recognized as having a high disease burden, as demonstrated by more frequent exacerbations,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Mepolizumab may serve to reduce the disease burden of this high-risk group by targeting the common pathophysiological pathway of IL-5 and eosinophilic-driven inflammation because it has proven clinical benefits in treating asthma and CRSwNP separately and together,” and the current study findings support the use of mepolizumab for this population in particular, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the incomplete data for voluntary assessments, the post hoc design and relatively small numbers of patients in various subgroups, notably COPD, and the potential inaccurate diagnosis of COPD, the researchers noted.

“Nevertheless, because the amount of improvement in each outcome following mepolizumab treatment differed depending on the comorbidity in question, our findings highlight the impact that comorbidities and their prevalence and severity have on outcomes,” and the overall success of mepolizumab across clinical characteristics and comorbidities supports the generalizability of the findings to the larger population of adults with severe asthma, they concluded.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Liu disclosed research funding from GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Gossamer Bio, and participation on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GSK, and Gossamer Bio.

Adults with asthma who were newly prescribed mepolizumab showed significant improvement in symptoms after 1 year regardless of comorbidities, based on data from 822 individuals.

Comorbidities including chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps (CRSwNP), gastroesophageal reflux disease GERD), anxiety and depression, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) are common in patients with severe asthma and add to the disease burden, wrote Mark C. Liu, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Some comorbidities, such as CRSwNP, share pathophysiological mechanisms with severe asthma, with interleukin-5 (IL-5),” and treatments targeting IL-5 could improve outcomes, they said.

In the real-world REALITI-A study, mepolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5, significantly reduced asthma exacerbation and oral corticosteroid use in severe asthma patients, they said.

To assess the impact of mepolizumab on patients with comorbidities, the researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of 822 adults with severe asthma, including 321 with CRSwNP, 309 with GERD, 203 with depression/anxiety, and 81 with COPD. The findings were published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

The main outcomes were the rate of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (CSEs) between the 12 months before and after mepolizumab initiation, and the changes from baseline in the daily maintenance use of oral corticosteroids (OCS).

Across all comorbidities, the rate of CSEs decreased significantly from the pretreatment period to the follow-up period, from 4.28 events per year to 1.23 events per year.

“A numerically greater reduction in the rate of CSEs was reported for patients with versus without CRSwNP, whereas the reverse was reported for patients with versus without COPD and depression/anxiety, although the confidence intervals were large for the with COPD subgroup,” the researchers wrote.

The median maintenance dose of oral corticosteroids decreased by at least 50% across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment; patients with CRSwNP had the greatest reduction (83%).

In addition, scores on the Asthma Control Questionnaire–5 decreased by at least 0.63 points, and least squared (LS) mean changes in forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) increased from baseline across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment by at least 74 mL.

Although patients with versus without CRSwNP had greater improvements, patients without GERD, depression/anxiety, and COPD had greater improvements than did those without the respective conditions with the exception of greater FEV1 improvement in patients with vs. without COPD.

“Patients with severe asthma and comorbid CRSwNP are recognized as having a high disease burden, as demonstrated by more frequent exacerbations,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Mepolizumab may serve to reduce the disease burden of this high-risk group by targeting the common pathophysiological pathway of IL-5 and eosinophilic-driven inflammation because it has proven clinical benefits in treating asthma and CRSwNP separately and together,” and the current study findings support the use of mepolizumab for this population in particular, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the incomplete data for voluntary assessments, the post hoc design and relatively small numbers of patients in various subgroups, notably COPD, and the potential inaccurate diagnosis of COPD, the researchers noted.

“Nevertheless, because the amount of improvement in each outcome following mepolizumab treatment differed depending on the comorbidity in question, our findings highlight the impact that comorbidities and their prevalence and severity have on outcomes,” and the overall success of mepolizumab across clinical characteristics and comorbidities supports the generalizability of the findings to the larger population of adults with severe asthma, they concluded.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Liu disclosed research funding from GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Gossamer Bio, and participation on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GSK, and Gossamer Bio.

Adults with asthma who were newly prescribed mepolizumab showed significant improvement in symptoms after 1 year regardless of comorbidities, based on data from 822 individuals.

Comorbidities including chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps (CRSwNP), gastroesophageal reflux disease GERD), anxiety and depression, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) are common in patients with severe asthma and add to the disease burden, wrote Mark C. Liu, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Some comorbidities, such as CRSwNP, share pathophysiological mechanisms with severe asthma, with interleukin-5 (IL-5),” and treatments targeting IL-5 could improve outcomes, they said.

In the real-world REALITI-A study, mepolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5, significantly reduced asthma exacerbation and oral corticosteroid use in severe asthma patients, they said.

To assess the impact of mepolizumab on patients with comorbidities, the researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of 822 adults with severe asthma, including 321 with CRSwNP, 309 with GERD, 203 with depression/anxiety, and 81 with COPD. The findings were published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

The main outcomes were the rate of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (CSEs) between the 12 months before and after mepolizumab initiation, and the changes from baseline in the daily maintenance use of oral corticosteroids (OCS).

Across all comorbidities, the rate of CSEs decreased significantly from the pretreatment period to the follow-up period, from 4.28 events per year to 1.23 events per year.

“A numerically greater reduction in the rate of CSEs was reported for patients with versus without CRSwNP, whereas the reverse was reported for patients with versus without COPD and depression/anxiety, although the confidence intervals were large for the with COPD subgroup,” the researchers wrote.

The median maintenance dose of oral corticosteroids decreased by at least 50% across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment; patients with CRSwNP had the greatest reduction (83%).

In addition, scores on the Asthma Control Questionnaire–5 decreased by at least 0.63 points, and least squared (LS) mean changes in forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) increased from baseline across all comorbidities after mepolizumab treatment by at least 74 mL.

Although patients with versus without CRSwNP had greater improvements, patients without GERD, depression/anxiety, and COPD had greater improvements than did those without the respective conditions with the exception of greater FEV1 improvement in patients with vs. without COPD.

“Patients with severe asthma and comorbid CRSwNP are recognized as having a high disease burden, as demonstrated by more frequent exacerbations,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Mepolizumab may serve to reduce the disease burden of this high-risk group by targeting the common pathophysiological pathway of IL-5 and eosinophilic-driven inflammation because it has proven clinical benefits in treating asthma and CRSwNP separately and together,” and the current study findings support the use of mepolizumab for this population in particular, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the incomplete data for voluntary assessments, the post hoc design and relatively small numbers of patients in various subgroups, notably COPD, and the potential inaccurate diagnosis of COPD, the researchers noted.

“Nevertheless, because the amount of improvement in each outcome following mepolizumab treatment differed depending on the comorbidity in question, our findings highlight the impact that comorbidities and their prevalence and severity have on outcomes,” and the overall success of mepolizumab across clinical characteristics and comorbidities supports the generalizability of the findings to the larger population of adults with severe asthma, they concluded.

The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Liu disclosed research funding from GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Gossamer Bio, and participation on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GSK, and Gossamer Bio.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY: IN PRACTICE

FDA, FTC uniting to promote biosimilars

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

Pregnant women in clinical trials: FDA questions how to include them

Pregnant women are rarely included in clinical drug trials, creating a significant and potentially dangerous gap in knowledge. Now, a new draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration broadens the discussion about these trials, suggesting issues to consider – including ethics and risks – when testing medications in pregnant women.

“The guidance opens the possibility of ethical conduct of trials in pregnant women but carefully lays out the caveats to be considered,” Christina Chambers, PhD, a perinatal epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. “With proper planning and thoughtful consultation with the relevant experts, this change in regulatory limitations will benefit pregnant women and their children.”

Attitudes have evolved toward more acceptance of including pregnant women in drug trials, according to a 2015 committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Still, “concerns about the potential for pregnancy in research trial participants have led to practices involving overly burdensome contraception requirements,” the opinion states. “Although changes have been made to encourage and recruit more women into research studies, a gap still exists in the available data on health and disease in women, including those who are pregnant” (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e100-7).

[polldaddy:9979976]

The draft guidance, released April 6 by the FDA, is “intended to advance scientific research in pregnant women, and discusses issues that should be considered within the framework of human subject protection regulations,” according to posting comments in the Federal Register.

The draft notes that in some cases, the lack of data about drugs may harm pregnant women and their fetuses by leading physicians to be fearful about prescribing medication. Conversely, physicians and pregnant women are often in the dark about the risks and benefits of medications that are prescribed and used, according to the draft.

In terms of research going forward, the guidance says “development of accessible treatment options for the pregnant population is a significant public health issue.”

The guidance, which recommends that clinical trial sponsors consider enlisting ethicists to take part in drug development program, offers these guidelines, among others, to drugmakers:

- It is “ethically justifiable” to include pregnant women in clinical trials under specific circumstances. “Sponsors should consider meeting with the appropriate FDA review division early in the development phase to discuss when and how to include pregnant women in the drug development plan. These discussions should involve FDA experts in bioethics and maternal health.”

- “Pregnant women can be enrolled in clinical trials that involve greater than minimal risk to the fetuses if the trials offer the potential for direct clinical benefit to the enrolled pregnant women and/or their fetuses.”

- A new pregnancy during a randomized, blinded clinical trial should prompt unblinding “so that counseling may be offered based on whether the fetus has been exposed to the investigational drug, placebo, or control.”

- The pregnant woman may continue the trial if potential benefits outweigh the risks.

- In general, pregnant women should not be enrolled in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials. Instead, those trials should be completed first “in a nonpregnant population that include females of reproductive potential.”

- Several types of events may call for the cessation of a clinical trial that includes pregnant women, such as serious maternal or fetal adverse events.

The draft guidance should take note of the fact that birth defects often don’t appear for months or even longer, according to Gerald Briggs, BPharm, FCCP, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco. “Until first year of life or later, the babies need to be monitored,” he said in an interview.

Mr. Briggs, who led a 2015 report examining the role of pregnant women in phase 4 clinical drug trials, added that the document should take note of recommendations from clinical teratologists regarding the design of animal studies that should be performed prior to human trials (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):810-5).

Comments on the draft guidance can be made at www.federalregister.gov and are due by June 8, 2018.

Dr. Chambers and Mr. Briggs reported no relevant disclosures.

Pregnant women are rarely included in clinical drug trials, creating a significant and potentially dangerous gap in knowledge. Now, a new draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration broadens the discussion about these trials, suggesting issues to consider – including ethics and risks – when testing medications in pregnant women.

“The guidance opens the possibility of ethical conduct of trials in pregnant women but carefully lays out the caveats to be considered,” Christina Chambers, PhD, a perinatal epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. “With proper planning and thoughtful consultation with the relevant experts, this change in regulatory limitations will benefit pregnant women and their children.”

Attitudes have evolved toward more acceptance of including pregnant women in drug trials, according to a 2015 committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Still, “concerns about the potential for pregnancy in research trial participants have led to practices involving overly burdensome contraception requirements,” the opinion states. “Although changes have been made to encourage and recruit more women into research studies, a gap still exists in the available data on health and disease in women, including those who are pregnant” (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e100-7).

[polldaddy:9979976]

The draft guidance, released April 6 by the FDA, is “intended to advance scientific research in pregnant women, and discusses issues that should be considered within the framework of human subject protection regulations,” according to posting comments in the Federal Register.

The draft notes that in some cases, the lack of data about drugs may harm pregnant women and their fetuses by leading physicians to be fearful about prescribing medication. Conversely, physicians and pregnant women are often in the dark about the risks and benefits of medications that are prescribed and used, according to the draft.

In terms of research going forward, the guidance says “development of accessible treatment options for the pregnant population is a significant public health issue.”

The guidance, which recommends that clinical trial sponsors consider enlisting ethicists to take part in drug development program, offers these guidelines, among others, to drugmakers:

- It is “ethically justifiable” to include pregnant women in clinical trials under specific circumstances. “Sponsors should consider meeting with the appropriate FDA review division early in the development phase to discuss when and how to include pregnant women in the drug development plan. These discussions should involve FDA experts in bioethics and maternal health.”

- “Pregnant women can be enrolled in clinical trials that involve greater than minimal risk to the fetuses if the trials offer the potential for direct clinical benefit to the enrolled pregnant women and/or their fetuses.”

- A new pregnancy during a randomized, blinded clinical trial should prompt unblinding “so that counseling may be offered based on whether the fetus has been exposed to the investigational drug, placebo, or control.”

- The pregnant woman may continue the trial if potential benefits outweigh the risks.

- In general, pregnant women should not be enrolled in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials. Instead, those trials should be completed first “in a nonpregnant population that include females of reproductive potential.”

- Several types of events may call for the cessation of a clinical trial that includes pregnant women, such as serious maternal or fetal adverse events.

The draft guidance should take note of the fact that birth defects often don’t appear for months or even longer, according to Gerald Briggs, BPharm, FCCP, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco. “Until first year of life or later, the babies need to be monitored,” he said in an interview.

Mr. Briggs, who led a 2015 report examining the role of pregnant women in phase 4 clinical drug trials, added that the document should take note of recommendations from clinical teratologists regarding the design of animal studies that should be performed prior to human trials (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):810-5).

Comments on the draft guidance can be made at www.federalregister.gov and are due by June 8, 2018.

Dr. Chambers and Mr. Briggs reported no relevant disclosures.

Pregnant women are rarely included in clinical drug trials, creating a significant and potentially dangerous gap in knowledge. Now, a new draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration broadens the discussion about these trials, suggesting issues to consider – including ethics and risks – when testing medications in pregnant women.

“The guidance opens the possibility of ethical conduct of trials in pregnant women but carefully lays out the caveats to be considered,” Christina Chambers, PhD, a perinatal epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. “With proper planning and thoughtful consultation with the relevant experts, this change in regulatory limitations will benefit pregnant women and their children.”

Attitudes have evolved toward more acceptance of including pregnant women in drug trials, according to a 2015 committee opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Still, “concerns about the potential for pregnancy in research trial participants have led to practices involving overly burdensome contraception requirements,” the opinion states. “Although changes have been made to encourage and recruit more women into research studies, a gap still exists in the available data on health and disease in women, including those who are pregnant” (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e100-7).

[polldaddy:9979976]

The draft guidance, released April 6 by the FDA, is “intended to advance scientific research in pregnant women, and discusses issues that should be considered within the framework of human subject protection regulations,” according to posting comments in the Federal Register.

The draft notes that in some cases, the lack of data about drugs may harm pregnant women and their fetuses by leading physicians to be fearful about prescribing medication. Conversely, physicians and pregnant women are often in the dark about the risks and benefits of medications that are prescribed and used, according to the draft.

In terms of research going forward, the guidance says “development of accessible treatment options for the pregnant population is a significant public health issue.”

The guidance, which recommends that clinical trial sponsors consider enlisting ethicists to take part in drug development program, offers these guidelines, among others, to drugmakers:

- It is “ethically justifiable” to include pregnant women in clinical trials under specific circumstances. “Sponsors should consider meeting with the appropriate FDA review division early in the development phase to discuss when and how to include pregnant women in the drug development plan. These discussions should involve FDA experts in bioethics and maternal health.”

- “Pregnant women can be enrolled in clinical trials that involve greater than minimal risk to the fetuses if the trials offer the potential for direct clinical benefit to the enrolled pregnant women and/or their fetuses.”

- A new pregnancy during a randomized, blinded clinical trial should prompt unblinding “so that counseling may be offered based on whether the fetus has been exposed to the investigational drug, placebo, or control.”

- The pregnant woman may continue the trial if potential benefits outweigh the risks.

- In general, pregnant women should not be enrolled in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials. Instead, those trials should be completed first “in a nonpregnant population that include females of reproductive potential.”

- Several types of events may call for the cessation of a clinical trial that includes pregnant women, such as serious maternal or fetal adverse events.

The draft guidance should take note of the fact that birth defects often don’t appear for months or even longer, according to Gerald Briggs, BPharm, FCCP, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco. “Until first year of life or later, the babies need to be monitored,” he said in an interview.

Mr. Briggs, who led a 2015 report examining the role of pregnant women in phase 4 clinical drug trials, added that the document should take note of recommendations from clinical teratologists regarding the design of animal studies that should be performed prior to human trials (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):810-5).

Comments on the draft guidance can be made at www.federalregister.gov and are due by June 8, 2018.

Dr. Chambers and Mr. Briggs reported no relevant disclosures.

Preprint publishing challenges the status quo in medicine

Like an upstart quick-draw challenging a grizzled gunslinger, preprint servers are muscling in on the once-exclusive territory of scientific journals.

These online venues sidestep the time-honored but lengthy peer-review process in favor of instant data dissemination. By directly posting unreviewed papers, authors escape the months-long drudgery of peer review, stake an immediate claim on new ideas, and connect instantly with like-minded scientists whose feedback can mold this new idea into a sound scientific contribution.

“The caveat, of course, is that it may be crap.”

That’s the unvarnished truth of preprint publishing, said John Inglis, PhD – and he should know. As the cofounder of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s bioRxiv, the largest-to-date preprint server for the biological sciences, he gives equal billing to both the lofty and the low, and lets them soar or sink by their own merit.

And many of them do soar, Dr. Inglis said. Of the more than 20,000 papers published since bioRxiv’s modest beginning in 2013, slightly more than 60% have gone on to peer-reviewed publication. The four most prolific sources of bioRxiv preprints are the research powerhouses of Stanford, Cambridge, Oxford, and Harvard. The twitterverse is virtually awash with #bioRxiv tags, which alert bioRxiv’s 18,000 followers to new papers in any of 27 subject areas. “We gave up counting 2 years ago, when we reached 100,000,” Dr. Inglis said.

BioRxiv, pronounced “bioarchive,” may be the largest preprint server for the biological sciences, but it’s not the only one. The Center for Open Science has created a preprint server search engine, which lists 25 such servers, a number of them in the life sciences.

PeerJ Preprints also offers a home for unreviewed papers, accepting “drafts of an article, abstract, or poster that has not yet been peer reviewed for formal publication.” Authors can submit a draft, incomplete, or final version, which can be online within 24 hours.

The bioRxiv model is coming to medicine, too. A new preprint server – to be called medRxiv – is expected to launch later in 2018 and will accept a wide range of papers on health and medicine, including clinical trial results.

Brand new or rebrand?

Preprint – or at least the concept of it – is nothing new, Dr. Inglis said. It’s simply the extension into the digital space of something that has been happening for many decades in the physical space.

Scientists have always written drafts of their papers and sent them out to friends and colleagues for feedback before unveiling them publicly. In the early 1990s, UC Berkeley astrophysicist Joanne Cohn began emailing unreviewed physics papers to colleagues. Within a couple of years, physicist Paul Ginsparg, PhD, of Cornell University, created a central repository for these papers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. This repository became aRxiv, a central component of communication in the physical sciences, and the progenitor of the preprint servers now in existence.

The biological sciences were far behind this curve of open sharing, Dr. Inglis said. “I think some biologists were always aware of aRxiv and intrigued by it, but most were unconvinced that the habits and behaviors of research biologists would support a similar process.”

The competition inherent in research biology was likely a large driver of that lag. “Biological experiments are complicated, it takes a long time for ideas to evolve and results to arrive, and people are possessive of their data and ideas. They have always shared information through conferences, but there was a lot of hesitation about making this information available in an uncontrolled way, beyond the audiences at those meetings,” he said.

[polldaddy:9970002]

Nature Publishing Group first floated the preprint notion among biologists in 2006, with Nature Precedings. It published more than 2,000 papers before folding, rather suddenly, in 2012. A publisher’s statement simply said that the effort was “unsustainable as originally conceived.”

Commentators suspected the model was a financial bust, and indeed, preprint servers aren’t money machines. BioRxiv, proudly not for profit, was founded with financial support from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and survives largely on private grants. In April 2017, it received a grant for an undisclosed amount from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, established by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan.

Who’s minding the data?

The screening process at bioRxiv is minimal, Dr. Inglis said. An in-house staff checks each paper for obvious flaws, like plagiarism, irrelevance, unacceptable article type, and offensive language. Then they’re sent out to a committee of affiliate scientists, which confirms that the manuscript is a research paper and that it contains science, without judging the quality of that science. Papers aren’t edited before being posted online.

Each bioRxiv paper gets a DOI link, and appears with the following disclaimer detailing the risks inherent in reading “unrefereed” science: “Because [peer review] can be lengthy, authors use the bioRxiv service to make their manuscripts available as ‘preprints’ before peer review, allowing other scientists to see, discuss, and comment on the findings immediately. Readers should therefore be aware that articles on bioRxiv have not been finalized by authors, might contain errors, and report information that has not yet been accepted or endorsed in any way by the scientific or medical community.”

From biology to medicine

The bioRxiv team is poised to jump into a different pool now – medical science. Although the launch date isn’t firm yet, medRxiv will go live sometime very soon, Dr. Inglis said. It’s a proposed partnership between Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the Yale-based YODA Project (Yale University Open Data Access Project), and BMJ. The medRxiv papers, like those posted to bioRxiv, will be screened but not peer reviewed or scrutinized for trial design, methodology, or interpretation of results.

The benefits of medRxiv will be more rapid communication of research results, increased opportunities for collaboration, the sharing of hard-to-publish outputs like quality innovations in health care, and greater transparency of clinical trials data, Dr. Inglis said. Despite this, he expects the same kind of push-back bioRxiv initially encountered, at least in the beginning.

“I expect we will be turning the clock back 5 years and find a lot of people who think this is potentially a bad thing, a risk that poor information or misinformation is going to be disseminated to a wider audience, which is exactly what we heard about bioRxiv,” he said. “But we hope that when medRxiv launches, it will demonstrate the same kind of gradual acceptance as people get more and more familiar with the preprint platform.”

The founders intend to build into the server policies to mitigate the risk from medically relevant information that hasn’t been peer reviewed, such as not accepting case studies or editorials and opinion pieces, he added.

While many find the preprint disclaimer acceptable on papers that have no immediate clinical impact, there is concern about applying it to papers that discuss patient treatment.

Howard Bauchner, MD, JAMA’s editor in chief, addressed it in an editorial published in September 2017. Although not explicitly directed at bioRxiv, Dr. Bauchner took a firm stance against shortcutting the evaluation of evidence that is often years in the making.

“New interest in preprint servers in clinical medicine increases the likelihood of premature dissemination and public consumption of clinical research findings prior to rigorous evaluation and peer review,” Dr. Bauchner wrote. “For most articles, public consumption of research findings prior to peer review will have little influence on health, but for some articles, the effect could be devastating for some patients if the results made public prior to peer review are wrong or incorrectly interpreted.”

Dr. Bauchner did not overstate the potential influence of unvetted science, as a January 2018 bioRxiv study on CRISPR gene editing clearly demonstrated. The paper by Carsten Charlesworth, a doctoral student at Stanford (Calif.) University, found that up to 79% of humans could already be immune to Crispr-Cas9, the gene-editing protein derived from Staphylococcus aureus and S. pyogenes. More than science geeks were reading: The report initially sent CRISPR stocks tumbling.

Aaron D. Viny, MD, is in general a hesitant fan of bioRxiv’s preprint platform. But he raised an eyebrow when he learned about medRxiv.

“The only pressure that I can see in regulating these reports is social media,” said Dr. Viny, a hematologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering, in New York. “The fear is that it will be misused in two different realms. The most dangerous and worrisome, of course, is for patients using the data to influence their care plan, when the data haven’t been vetted appropriately. But secondarily, how could it influence the economics of clinical trials? There is no shortage of hedge fund managers in biotech. These data could misinform a consultant who might know the area in a way that artificially exploits early research data. Could that permit someone to submit disingenuous data to manipulate the stock of a given pharmaceutical company? I don’t know how you police that kind of thing.”

Who’s loving it – and why?

There are plenty of reasons to support a thriving preprint community, said Jessica Polka, PhD, director of ASAPbio, (Accelerating Science and Publication in biology), a group that bills itself as a scientist-driven initiative to promote the productive use of preprints in the life sciences.

“Preprinting complements traditional journal publishing by allowing researchers to rapidly communicate their findings to the scientific community,” she said. “This, in turn, provides them with opportunities for earlier and broader feedback and a way to transparently demonstrate progress on a project. More importantly, the whole community benefits by having earlier access to research findings, which can accelerate the pace of discovery.”

The disclosures applied to every preprint paper are the publisher’s way of assuring this same awareness, she said. And preprints do need to be approached with some skepticism, as should peer-reviewed literature.

“The veracity of published papers is not always a given. An example is the 1998 vaccine paper [published in the Lancet] by Dr. Andrew Wakefield,” which launched the antivaccine movement. “But the answer to problems of reliability is to provide more information about the research and how it has been verified and evaluated, not less information. For example, confirmation bias can make it difficult to refute work that has been published. The current incentives for publishing negative results in a journal are not strong enough to reveal all of the information that could be useful to other researchers, but preprinting reduces the barrier to sharing negative results,” she said.

Swimming up the (main)stream

Universal peer-reviewed acceptance of preprints isn’t a done deal, Dr. Polka said. Journals are tussling with how to handle these papers. The Lancet clearly states that preprints don’t constitute prior publication and are welcome. The New England Journal of Medicine offers an uncontestable “no way.”

JAMA discourages submitting preprints, and will consider one only if the submitted version offers “meaningful new information” above what the preprint disseminated.

Cell Press has a slightly different take. They will consider papers previously posted on preprint services, but the policy applies only to the original submitted version of the paper. “We do not support posting of revisions that respond to editorial input and peer review or the final published version to preprint servers,” the policy notes.

In an interview, Deborah Sweet, PhD, the group’s vice president of editorial, elaborated on the policy. “In our view, one of the most important purposes of preprint posting is to gather feedback from the scientific community before a formal submission to a journal,” she said. “The ‘original submission’ term in our guidelines refers to the first version of the paper submitted to [Cell Press], which could include revisions made in response to community feedback on a preprint. After formal submission, we think it is most appropriate to incorporate and represent the value of the editorial and peer-review evaluation process in the final published journal article so that is clearly identifiable as the version of record.”

bioRxiv has made substantial inroads with dozens of other peer-reviewed journals. More than 100 – including a number of publications by EMBO Press and PLOS (Public Library of Science) – participate in bioRxiv’s B2J (BioRxiv-to-journal) direct-submission program.

With a few clicks, authors can transmit their bioRxiv manuscript files directly to these journals, without having to prepare separate submissions, Dr. Sweet said. Last year, Cell Press added two publications – Cell Reports and Structure – to the B2J program. “Once the paper is sent, it moves behind the scenes to the journal system and reappears as a formal submission,” she said. “In our process, before transferring the paper to the journal editors, authors have a chance to update the files (for example, to add a cover letter) and answer the standard questions that we ask, including ones about reviewer suggestions and exclusion requests. Once that step is done, the paper is handed over to the editorial team, and it’s ready to go for consideration in the same way as any other submission.”

Who’s reading?

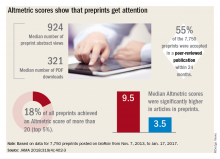

Regardless of whether peer-review journals grant them legitimacy, preprints are getting a lot of views. A recent research letter, published in JAMA, looked at readership and online attention in 7,750 preprints posted from November 2013 to January 2017.

Primary author Stylianos Serghiou then selected 776 papers that had first appeared in bioRxiv, and matched them with 3,647 peer-reviewed articles lacking preprint exposure. He examined several publishing metrics for the papers, including views and downloads, citations in other sources, and Altmetric scores.

Altmetric tracks digital attention to scientific papers: Wikipedia citations, mentions in policy documents, blog discussions, and social media mentions including Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter. An Altmetric “attention score” of more than 20 corresponds to articles in the top 5% of readership, he said in an interview.

“Almost one in five of the bioRxiv preprints were getting these very high Almetric scores – much higher scores than articles that had no preprint posting,” Mr. Serghiou said in an interview.

Other findings include:

- The median number of preprint abstract views was 924, and the median number of PDF downloads was 321.

- In total, 18% of the preprints achieved an Altmetric score of more than 20.

- Of 7,750 preprints, 55% were accepted in a peer-reviewed publication within 24 months.

- Altmetric scores were significantly higher in articles in preprints (median 9.5 vs. 3.5).

The differences are probably related, at least in part, to the digital media savvy of preprint authors, Mr. Serghiou suggested. “We speculate that people who publish in bioRxiv may be more familiar with social media methods of making others aware of their work. They tend to be very good at using platforms like Twitter and Facebook to promote their results.”

Despite the high exposure scores, only 10% of bioRxiv articles get any posted comments or feedback – a key raison d’être for using a preprint service.

“Ten percent doesn’t sound like a very robust [feedback], but most journal articles get no comments whatsoever,” Dr. Inglis said. “And if they do, especially on the weekly magazines of science, comments may be from someone who has an ax to grind, or who doesn’t know much about the subject.”

What isn’t measured, in either volume or import, is the private communication a preprint engenders, Dr. Inglis said. “Feedback comes directly and privately to the author through email or at meetings or on the phone. We hear time and again that authors get hundreds of downloads after posting, and receive numerous contacts from colleagues who want to know more, to point out weaknesses, or request collaborations. These are the advantages we see from this potentially anxiety-provoking process of putting a manuscript out that has not been approved for publication. The entire purpose is to accelerate the speed of research by accelerating the speed of communication.”

Dr. Inglis, Dr. Sweet, and Dr. Polka are all employees of their respective companies. Dr. Viny and Mr. Serghiou both reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

It’s another beautiful day on the upper east side of Manhattan. The sun shines through the window shades, my 2-year-old daughter sings to herself as she wakes up, my wife has just returned from an early-morning workout – all is right as rain.

My phone buzzes. My stomach clenches. It buzzes again. My Twitter alerts are here. I dread this part of my morning ritual – finding out if I’ve been scooped overnight by the massive inflow of scientific manuscripts reported to me by my army of scientific literature–searching Twitter bots.

But this massive data dump now has a #fakenews problem. It’s not Russian election meddling, it’s open source “preprint” publications. Nearly half of my morning list of Twitter alerts now are sourced from the latest uploads to bioRxiv. BioRxiv is an online site run by scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and is composed of posting manuscripts without undergoing a peer-review process. Now, most commonly, these manuscripts are concurrently under review in the bona fide peer-review process elsewhere, but unrevised, they are uploaded directly for public consumption.

There was one recent tweet that highlighted some interesting logistical considerations for bioRxiv manuscripts in the peer-review process. The tweet from an unnamed laboratory complains that a peer reviewer is displeased with the authors citing their own bioRxiv paper, while the tweeter contends that all referenced information, online or otherwise, must be cited. Moreover, the reviewer brings up an accusation of self-plagiarism as the submitted manuscript is identical to the one on bioRxiv. While the latter just seems like a misunderstanding of the bioRxiv platform, the former is a really interesting question of whether bioRxiv represents data that can/should be referenced.

Proponents of the platform are excited that data is accessible sooner, that one’s latest and greatest scientific finding can be “scoop proof” by getting it online and marking one’s territory. Naysayers contend that, without peer review, the work cannot truly be part of the scientific literature and should be taken with great caution.

There is undoubtedly danger. Online media sources Gizmodo and the Motley Fool both reported that a January 2018 bioRxiv preprint resulted in a nearly 20% drop in stock prices of CRISPR biotechnology firms Editas Medicine and Intellia Therapeutics. The manuscript warned of the potential immunogenicity of CRISPR, suggesting that preexisting antibodies might limit its clinical application. Far more cynically, this highlights how a stock price could theoretically be artificially manipulated through preprint data.

The preprint is an open market response to the long, arduous process that peer review has become, but undoubtedly, peer review is an essential part of how we maintain transparency and accountability in science and medicine. It remains to be seen exactly how journal editors intend to use bioRxiv submissions in the appraisal of “novelty.”

How will the scientific community vet and referee the works, and will the title and conclusions of a scientifically flawed work permeate misleading information into the field and lay public? Would you let it influence your research or clinical practice? We will be finding out one tweet at a time.

Aaron D. Viny, MD, is with the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., where he is a clinical instructor, is on the staff of the leukemia service, and is a clinical researcher in the Ross Levine Lab. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him on Twitter @TheDoctorIsVin.

It’s another beautiful day on the upper east side of Manhattan. The sun shines through the window shades, my 2-year-old daughter sings to herself as she wakes up, my wife has just returned from an early-morning workout – all is right as rain.

My phone buzzes. My stomach clenches. It buzzes again. My Twitter alerts are here. I dread this part of my morning ritual – finding out if I’ve been scooped overnight by the massive inflow of scientific manuscripts reported to me by my army of scientific literature–searching Twitter bots.

But this massive data dump now has a #fakenews problem. It’s not Russian election meddling, it’s open source “preprint” publications. Nearly half of my morning list of Twitter alerts now are sourced from the latest uploads to bioRxiv. BioRxiv is an online site run by scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and is composed of posting manuscripts without undergoing a peer-review process. Now, most commonly, these manuscripts are concurrently under review in the bona fide peer-review process elsewhere, but unrevised, they are uploaded directly for public consumption.

There was one recent tweet that highlighted some interesting logistical considerations for bioRxiv manuscripts in the peer-review process. The tweet from an unnamed laboratory complains that a peer reviewer is displeased with the authors citing their own bioRxiv paper, while the tweeter contends that all referenced information, online or otherwise, must be cited. Moreover, the reviewer brings up an accusation of self-plagiarism as the submitted manuscript is identical to the one on bioRxiv. While the latter just seems like a misunderstanding of the bioRxiv platform, the former is a really interesting question of whether bioRxiv represents data that can/should be referenced.