User login

Alcohol dependence drug the next antianxiety med?

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN PHARMACOLOGY

Aged black garlic supplement may help lower BP

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

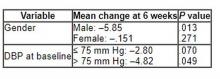

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 6 weeks, consumption of ABG with a high concentration of s-allyl-L-cystine (SAC) was associated with a nearly 6-mm Hg reduction in DBP in men. Other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors were not significantly affected.

“The observed reduction in DBP by ABG extract was similar to the effects of dietary approaches, including the effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH) diet on BP,” say Rosa M. Valls, PhD, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, and colleagues.

“The potential beneficial effects of ABG may contribute to obtaining an optimal DBP” but were “better observed in men and in nonoptimal DBP populations,” they write in the study, published in Nutrients.

Pure SAC and aged garlics have shown healthy effects on multiple targets in in vitro and in vivo tests. However, previous studies in humans have not focused on ABG but rather on other types of aged garlic in patients with some type of CVD risk factor and suffered from methodologic or design weaknesses, the authors note.

To address this gap, Dr. Valls and colleagues randomly assigned 67 individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia (defined as LDL levels of at least 115 mg/dL) to receive one ABG tablet (250 mg ABG extract/1.25 mg SAC) or placebo daily for 6 weeks. Following a 3-week washout, the groups were reversed and the new intervention continued for another 6 weeks.

Participants received dietary recommendations regarding CVD risk factors and had their dietary habits assessed through a 3-day food record at baseline and after 6 weeks during both treatments.

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment or antihypertensives were excluded, as were those with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or higher, those with a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, or active smokers.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The mean systolic and diastolic pressures at baseline were 124/75 mm Hg in the ABG group and 121/74 mm Hg in the placebo group. Their mean age was 53 years.

Adherence with the protocol was “high” at 96.5% in both groups, and no adverse effects were reported.

Reduced risk of death from stroke, ischemic heart disease

Although no significant differences between ABG and placebo were observed at 3 weeks, the decline in DBP after consumption of the ABG extract became significant at 6 weeks (mean change, –3.7 mm Hg vs. –0.10 mm Hg; P = .007).

When stratified by sex and categories of DBP, the mean change in DBP after 6 weeks of ABG consumption was particularly prominent in men and in those with a baseline DBP of at least 75 mm Hg.

The 6-week change in systolic blood pressure with ABG and placebo was 1.32 mm Hg and 2.84 mm Hg, respectively (P = .694).

At week 6, total cholesterol levels showed a “quadratic decreasing trend” after ABG treatment (P = .047), but no other significant differences between groups were observed for lipid profile, apolipoproteins, or other outcomes of interest, including serum insulin, waist circumference, and body mass index.

The authors note that although systolic BP elevation “has a greater effect on outcomes, both systolic and diastolic hypertension independently influence the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, regardless of the definition of hypertension” and that the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles with every 10 mm Hg increase in DBP in people between the ages of 40 and 89 years.

“Thus, reducing DBP by 5 mm Hg results in a 40% lower risk of death from stroke and a 30% lower risk of death from ischemic heart disease or other vascular death,” they state.

Small study

Commenting for this news organization, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RDN, professor and chief of the department of preventive medicine’s nutrition division, Northwestern University, Chicago, said that for many years, garlic has been “reported to be an adjunct to the benefits of a healthy eating pattern, with inconclusive results.”

She noted that ABG is “literally aged for many months to years, and the resulting concentrate is found higher in many organosulfur compounds and phytochemicals that suggest enhanced response.”

Dr. Van Horn, a member of the American Heart Association’s Nutrition Committee, who was not involved with the study, continued: “The data suggest that ABG that is much more highly concentrated than fresh or processed garlic might be helpful in lowering BP in certain subgroups, in this case men with higher BP.”

However, she cautioned, “these results are limited in a small study, and ... potential other issues, such as sodium, potassium, or other nutrients known to be associated with blood pressure, were not reported, thereby raising questions about the exclusivity of the ABG over other accompanying dietary factors.”

The study was funded by the Center for the Development of Industrial Technology of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Two authors are employees of Pharmactive Biotech Products, SL (Madrid), which manufactured the ABG product, but neither played a role in any result or conclusion. The other authors and Dr. Van Horn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRIENTS

New insight into how psychedelics work

What causes the dramatic alterations in subjective awareness experienced during a psychedelic “trip?” A new study maps anatomical changes in specific neurotransmitter systems and brain regions that may be responsible for these effects.

Investigators gathered more than 6,800 accounts from individuals who had taken one of 27 different psychedelic compounds. Using a machine learning strategy, they extracted commonly used words from these testimonials, linking them with 40 different neurotransmitter subtypes that had likely induced these experiences.

The investigators then linked these subjective experiences with specific brain regions where the receptor combinations are most commonly found and, using gene transcription probes, created a 3D whole-brain map of the brain receptors and the subjective experiences linked to them.

“Hallucinogenic drugs may very well turn out to be the next big thing to improve clinical care of major mental health conditions,” senior author Danilo Bzdok, MD, PhD, associate professor, McGill University, Montreal, said in a press release.

“Our study provides a first step, a proof of principle, that we may be able to build machine-learning systems in the future that can accurately predict which neurotransmitter receptor combinations need to be stimulated to induce a specific state of conscious experience in a given person,” said Dr. Bzdok, who is also the Canada CIFAR AI Chair at Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

The study was published online in Science Advances.

‘Unique window’

Psychedelic drugs “show promise” as treatments for various psychiatric disorders, but subjective alterations of reality are “highly variable across individuals” and this “poses a key challenge as we venture to bring hallucinogenic substances into medical practice,” the investigators note.

Although the 5-HT2A receptor has been regarded as a “putative essential mechanism” of hallucinogenic experiences, it is unclear whether the experiential differences are explained by functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A receptor itself or “orchestrated by the vast array of neurotransmitter receptor subclasses on which these drugs act,” they add.

Lead author Galen Ballentine, MD, psychiatry resident, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, told this news organization that he was “personally eager to find novel ways to identify the neurobiological underpinnings of different states of conscious awareness.”

Psychedelics, he said, offer a “unique window into a vast array of unusual states of consciousness and are particularly useful because they can point toward underlying mechanistic processes that are initiated in specific areas of receptor expression.”

The investigators wanted to understand “how these drugs work in order to help guide their use in clinical practice,” Dr. Ballentine said.

To explore the issue, they undertook the “largest investigation to date into the neuroscience of psychedelic drug experiences,” Dr. Ballentine said. “While most studies are limited to a single drug on a handful of subjects, this project integrates thousands of experiences induced by dozens of different hallucinogenic compounds, viewing them through the prism of 40 receptor subtypes.”

Unique neurotransmitter fingerprint

The researchers analyzed 6,850 experience reports of people who had taken 1 of 27 psychedelic compounds. The reports were drawn from a database hosted by the Erowid Center, an organization that collects first-hand accounts of experiences elicited by psychoactive drugs.

The researchers constructed a “bag-of-words” encoding of the text descriptions in each testimonial. Using linguistic calculation methods, they derived a final vocabulary of 14,410 words that they analyzed for descriptive experiential terms.

To shed light on the spatial distribution of these compounds that modulate neuronal activity during subjective “trips,” they compared normalized measurements of their relative binding strengths in 40 sites.

- 5-HT (5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT2B, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT5A, 5-HT6, 5-HT7)

- Dopamine (D1, D2, D3, D4, D5)

- Adrenergic (a-1A, a-1B, a-2A, a-2B, a-2C, b-1, b-2)

- Serotonin transporter (SERT)

- Dopamine transporter (DAT)

- Norepinephrine transporter (NET)

- Imidazoline-1 receptor (I1)

- Sigma receptors (s-1, s-2)

- d-opioid receptor (DOR)

- k-opioid receptor (KOR)

- m-opioid receptor (MOR)

- Muscarinic receptors (M1, M2, M3, M4, M5)

- Histamine receptors (H1, H2)

- Calcium ion channel (CA+)

- NMDA glutamate receptor

To map receptor-experience factors to regional levels of receptor gene transcription, they utilized human gene expression data drawn from the Allen Human Brain Atlas, as well as the Shafer-Yeo brain atlas.

Via a machine-learning algorithm, they dissected the “phenomenologically rich anecdotes” into a ranking of constituent brain-behavior factors, each of which was characterized by a “unique neurotransmitter fingerprint of action and a unique experiential context” and ultimately created a dimensional map of these neurotransmitter systems.

Data-driven framework

Cortex-wide distribution of receptor-experience factors was found in both deep and shallow anatomical brain regions. Regions involved in genetic factor expressions were also wide-ranging, spanning from higher association cortices to unimodal sensory cortices.

The dominant factor “elucidated mystical experience in general and the dissolution of self-world boundaries (ego dissolution) in particular,” the authors report, while the second- and third-most explanatory factors “evoked auditory, visual, and emotional themes of mental expansion.”

Ego dissolution was found to be most associated with the 5-HT2A receptor, as well as other serotonin receptors (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2B), adrenergic receptors a-2A and b-2, and the D2 receptor.

Alterations in sensory perception were associated with expression of the 5-HT2A receptor in the visual cortex, while modulation of the salience network by dopamine and opioid receptors were implicated in the experience transcendence of space, time, and the structure of self. Auditory hallucinations were linked to a weighted blend of receptors expressed throughout the auditory cortex.

“This data-driven framework identifies patterns that undergird diverse psychedelic experiences such as mystical bliss, existential terror, and complex hallucinations,” Dr. Ballentine commented.

“Simultaneously subjective and neurobiological, these patterns align with the leading hypothesis that psychedelics temporarily diminish top-down control of the most evolutionarily advanced regions of the brain, while at the same time amplifying bottom-up sensory processing from primary sensory cortices,” he added.

Forging a new path

Scott Aaronson, MD, chief science officer, Institute for Advanced Diagnostics and Therapeutics and director of the Centre of Excellence at Sheppard Pratt, Towson, Md., said, “As we try to get our arms around understanding the implications of a psychedelic exposure, forward-thinking researchers like Dr. Bzdok et al. are offering interesting ways to capture and understand the experience.”

Dr. Aaronson, an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who was not involved with the study, continued: “Using the rapidly developing field of natural language processing (NLP), which looks at how language is used for a deeper understanding of human experiences, and combining it with effects of psychedelic compounds on neuronal pathways and neurochemical receptor sites, the authors are forging a new path for further inquiry.”

In an accompanying editorial, Daniel Barron, MD, PhD, medical director, Interventional Pain Psychiatry Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Richard Friedman, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, call the work “impressive” and “clever.”

“Psychedelics paired with new applications of computational tools might help bypass the imprecision of psychiatric diagnosis and connect measures of behavior to specific physiologic targets,” they write.

The research was supported by the Brain Canada Foundation, through the Canada Brain Research Fund, a grant from the NIH grant, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Bzdok was also supported by the Healthy Brains Healthy Lives initiative (Canada First Research Excellence fund) and the CIFAR Artificial Intelligence Chairs program (Canada Institute for Advanced Research), as well as Research Award and Teaching Award by Google. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. No disclosures were listed for Dr. Barron and Dr. Friedman. Dr. Aaronson’s research is supported by Compass Pathways.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What causes the dramatic alterations in subjective awareness experienced during a psychedelic “trip?” A new study maps anatomical changes in specific neurotransmitter systems and brain regions that may be responsible for these effects.

Investigators gathered more than 6,800 accounts from individuals who had taken one of 27 different psychedelic compounds. Using a machine learning strategy, they extracted commonly used words from these testimonials, linking them with 40 different neurotransmitter subtypes that had likely induced these experiences.

The investigators then linked these subjective experiences with specific brain regions where the receptor combinations are most commonly found and, using gene transcription probes, created a 3D whole-brain map of the brain receptors and the subjective experiences linked to them.

“Hallucinogenic drugs may very well turn out to be the next big thing to improve clinical care of major mental health conditions,” senior author Danilo Bzdok, MD, PhD, associate professor, McGill University, Montreal, said in a press release.

“Our study provides a first step, a proof of principle, that we may be able to build machine-learning systems in the future that can accurately predict which neurotransmitter receptor combinations need to be stimulated to induce a specific state of conscious experience in a given person,” said Dr. Bzdok, who is also the Canada CIFAR AI Chair at Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

The study was published online in Science Advances.

‘Unique window’

Psychedelic drugs “show promise” as treatments for various psychiatric disorders, but subjective alterations of reality are “highly variable across individuals” and this “poses a key challenge as we venture to bring hallucinogenic substances into medical practice,” the investigators note.

Although the 5-HT2A receptor has been regarded as a “putative essential mechanism” of hallucinogenic experiences, it is unclear whether the experiential differences are explained by functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A receptor itself or “orchestrated by the vast array of neurotransmitter receptor subclasses on which these drugs act,” they add.

Lead author Galen Ballentine, MD, psychiatry resident, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, told this news organization that he was “personally eager to find novel ways to identify the neurobiological underpinnings of different states of conscious awareness.”

Psychedelics, he said, offer a “unique window into a vast array of unusual states of consciousness and are particularly useful because they can point toward underlying mechanistic processes that are initiated in specific areas of receptor expression.”

The investigators wanted to understand “how these drugs work in order to help guide their use in clinical practice,” Dr. Ballentine said.

To explore the issue, they undertook the “largest investigation to date into the neuroscience of psychedelic drug experiences,” Dr. Ballentine said. “While most studies are limited to a single drug on a handful of subjects, this project integrates thousands of experiences induced by dozens of different hallucinogenic compounds, viewing them through the prism of 40 receptor subtypes.”

Unique neurotransmitter fingerprint

The researchers analyzed 6,850 experience reports of people who had taken 1 of 27 psychedelic compounds. The reports were drawn from a database hosted by the Erowid Center, an organization that collects first-hand accounts of experiences elicited by psychoactive drugs.

The researchers constructed a “bag-of-words” encoding of the text descriptions in each testimonial. Using linguistic calculation methods, they derived a final vocabulary of 14,410 words that they analyzed for descriptive experiential terms.

To shed light on the spatial distribution of these compounds that modulate neuronal activity during subjective “trips,” they compared normalized measurements of their relative binding strengths in 40 sites.

- 5-HT (5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT2B, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT5A, 5-HT6, 5-HT7)

- Dopamine (D1, D2, D3, D4, D5)

- Adrenergic (a-1A, a-1B, a-2A, a-2B, a-2C, b-1, b-2)

- Serotonin transporter (SERT)

- Dopamine transporter (DAT)

- Norepinephrine transporter (NET)

- Imidazoline-1 receptor (I1)

- Sigma receptors (s-1, s-2)

- d-opioid receptor (DOR)

- k-opioid receptor (KOR)

- m-opioid receptor (MOR)

- Muscarinic receptors (M1, M2, M3, M4, M5)

- Histamine receptors (H1, H2)

- Calcium ion channel (CA+)

- NMDA glutamate receptor

To map receptor-experience factors to regional levels of receptor gene transcription, they utilized human gene expression data drawn from the Allen Human Brain Atlas, as well as the Shafer-Yeo brain atlas.

Via a machine-learning algorithm, they dissected the “phenomenologically rich anecdotes” into a ranking of constituent brain-behavior factors, each of which was characterized by a “unique neurotransmitter fingerprint of action and a unique experiential context” and ultimately created a dimensional map of these neurotransmitter systems.

Data-driven framework

Cortex-wide distribution of receptor-experience factors was found in both deep and shallow anatomical brain regions. Regions involved in genetic factor expressions were also wide-ranging, spanning from higher association cortices to unimodal sensory cortices.

The dominant factor “elucidated mystical experience in general and the dissolution of self-world boundaries (ego dissolution) in particular,” the authors report, while the second- and third-most explanatory factors “evoked auditory, visual, and emotional themes of mental expansion.”

Ego dissolution was found to be most associated with the 5-HT2A receptor, as well as other serotonin receptors (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2B), adrenergic receptors a-2A and b-2, and the D2 receptor.

Alterations in sensory perception were associated with expression of the 5-HT2A receptor in the visual cortex, while modulation of the salience network by dopamine and opioid receptors were implicated in the experience transcendence of space, time, and the structure of self. Auditory hallucinations were linked to a weighted blend of receptors expressed throughout the auditory cortex.

“This data-driven framework identifies patterns that undergird diverse psychedelic experiences such as mystical bliss, existential terror, and complex hallucinations,” Dr. Ballentine commented.

“Simultaneously subjective and neurobiological, these patterns align with the leading hypothesis that psychedelics temporarily diminish top-down control of the most evolutionarily advanced regions of the brain, while at the same time amplifying bottom-up sensory processing from primary sensory cortices,” he added.

Forging a new path

Scott Aaronson, MD, chief science officer, Institute for Advanced Diagnostics and Therapeutics and director of the Centre of Excellence at Sheppard Pratt, Towson, Md., said, “As we try to get our arms around understanding the implications of a psychedelic exposure, forward-thinking researchers like Dr. Bzdok et al. are offering interesting ways to capture and understand the experience.”

Dr. Aaronson, an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who was not involved with the study, continued: “Using the rapidly developing field of natural language processing (NLP), which looks at how language is used for a deeper understanding of human experiences, and combining it with effects of psychedelic compounds on neuronal pathways and neurochemical receptor sites, the authors are forging a new path for further inquiry.”

In an accompanying editorial, Daniel Barron, MD, PhD, medical director, Interventional Pain Psychiatry Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Richard Friedman, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, call the work “impressive” and “clever.”

“Psychedelics paired with new applications of computational tools might help bypass the imprecision of psychiatric diagnosis and connect measures of behavior to specific physiologic targets,” they write.

The research was supported by the Brain Canada Foundation, through the Canada Brain Research Fund, a grant from the NIH grant, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Bzdok was also supported by the Healthy Brains Healthy Lives initiative (Canada First Research Excellence fund) and the CIFAR Artificial Intelligence Chairs program (Canada Institute for Advanced Research), as well as Research Award and Teaching Award by Google. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. No disclosures were listed for Dr. Barron and Dr. Friedman. Dr. Aaronson’s research is supported by Compass Pathways.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What causes the dramatic alterations in subjective awareness experienced during a psychedelic “trip?” A new study maps anatomical changes in specific neurotransmitter systems and brain regions that may be responsible for these effects.

Investigators gathered more than 6,800 accounts from individuals who had taken one of 27 different psychedelic compounds. Using a machine learning strategy, they extracted commonly used words from these testimonials, linking them with 40 different neurotransmitter subtypes that had likely induced these experiences.

The investigators then linked these subjective experiences with specific brain regions where the receptor combinations are most commonly found and, using gene transcription probes, created a 3D whole-brain map of the brain receptors and the subjective experiences linked to them.

“Hallucinogenic drugs may very well turn out to be the next big thing to improve clinical care of major mental health conditions,” senior author Danilo Bzdok, MD, PhD, associate professor, McGill University, Montreal, said in a press release.

“Our study provides a first step, a proof of principle, that we may be able to build machine-learning systems in the future that can accurately predict which neurotransmitter receptor combinations need to be stimulated to induce a specific state of conscious experience in a given person,” said Dr. Bzdok, who is also the Canada CIFAR AI Chair at Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

The study was published online in Science Advances.

‘Unique window’

Psychedelic drugs “show promise” as treatments for various psychiatric disorders, but subjective alterations of reality are “highly variable across individuals” and this “poses a key challenge as we venture to bring hallucinogenic substances into medical practice,” the investigators note.

Although the 5-HT2A receptor has been regarded as a “putative essential mechanism” of hallucinogenic experiences, it is unclear whether the experiential differences are explained by functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A receptor itself or “orchestrated by the vast array of neurotransmitter receptor subclasses on which these drugs act,” they add.

Lead author Galen Ballentine, MD, psychiatry resident, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, told this news organization that he was “personally eager to find novel ways to identify the neurobiological underpinnings of different states of conscious awareness.”

Psychedelics, he said, offer a “unique window into a vast array of unusual states of consciousness and are particularly useful because they can point toward underlying mechanistic processes that are initiated in specific areas of receptor expression.”

The investigators wanted to understand “how these drugs work in order to help guide their use in clinical practice,” Dr. Ballentine said.

To explore the issue, they undertook the “largest investigation to date into the neuroscience of psychedelic drug experiences,” Dr. Ballentine said. “While most studies are limited to a single drug on a handful of subjects, this project integrates thousands of experiences induced by dozens of different hallucinogenic compounds, viewing them through the prism of 40 receptor subtypes.”

Unique neurotransmitter fingerprint

The researchers analyzed 6,850 experience reports of people who had taken 1 of 27 psychedelic compounds. The reports were drawn from a database hosted by the Erowid Center, an organization that collects first-hand accounts of experiences elicited by psychoactive drugs.

The researchers constructed a “bag-of-words” encoding of the text descriptions in each testimonial. Using linguistic calculation methods, they derived a final vocabulary of 14,410 words that they analyzed for descriptive experiential terms.

To shed light on the spatial distribution of these compounds that modulate neuronal activity during subjective “trips,” they compared normalized measurements of their relative binding strengths in 40 sites.

- 5-HT (5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT2B, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT5A, 5-HT6, 5-HT7)

- Dopamine (D1, D2, D3, D4, D5)

- Adrenergic (a-1A, a-1B, a-2A, a-2B, a-2C, b-1, b-2)

- Serotonin transporter (SERT)

- Dopamine transporter (DAT)

- Norepinephrine transporter (NET)

- Imidazoline-1 receptor (I1)

- Sigma receptors (s-1, s-2)

- d-opioid receptor (DOR)

- k-opioid receptor (KOR)

- m-opioid receptor (MOR)

- Muscarinic receptors (M1, M2, M3, M4, M5)

- Histamine receptors (H1, H2)

- Calcium ion channel (CA+)

- NMDA glutamate receptor

To map receptor-experience factors to regional levels of receptor gene transcription, they utilized human gene expression data drawn from the Allen Human Brain Atlas, as well as the Shafer-Yeo brain atlas.

Via a machine-learning algorithm, they dissected the “phenomenologically rich anecdotes” into a ranking of constituent brain-behavior factors, each of which was characterized by a “unique neurotransmitter fingerprint of action and a unique experiential context” and ultimately created a dimensional map of these neurotransmitter systems.

Data-driven framework

Cortex-wide distribution of receptor-experience factors was found in both deep and shallow anatomical brain regions. Regions involved in genetic factor expressions were also wide-ranging, spanning from higher association cortices to unimodal sensory cortices.

The dominant factor “elucidated mystical experience in general and the dissolution of self-world boundaries (ego dissolution) in particular,” the authors report, while the second- and third-most explanatory factors “evoked auditory, visual, and emotional themes of mental expansion.”

Ego dissolution was found to be most associated with the 5-HT2A receptor, as well as other serotonin receptors (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2B), adrenergic receptors a-2A and b-2, and the D2 receptor.

Alterations in sensory perception were associated with expression of the 5-HT2A receptor in the visual cortex, while modulation of the salience network by dopamine and opioid receptors were implicated in the experience transcendence of space, time, and the structure of self. Auditory hallucinations were linked to a weighted blend of receptors expressed throughout the auditory cortex.

“This data-driven framework identifies patterns that undergird diverse psychedelic experiences such as mystical bliss, existential terror, and complex hallucinations,” Dr. Ballentine commented.

“Simultaneously subjective and neurobiological, these patterns align with the leading hypothesis that psychedelics temporarily diminish top-down control of the most evolutionarily advanced regions of the brain, while at the same time amplifying bottom-up sensory processing from primary sensory cortices,” he added.

Forging a new path

Scott Aaronson, MD, chief science officer, Institute for Advanced Diagnostics and Therapeutics and director of the Centre of Excellence at Sheppard Pratt, Towson, Md., said, “As we try to get our arms around understanding the implications of a psychedelic exposure, forward-thinking researchers like Dr. Bzdok et al. are offering interesting ways to capture and understand the experience.”

Dr. Aaronson, an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who was not involved with the study, continued: “Using the rapidly developing field of natural language processing (NLP), which looks at how language is used for a deeper understanding of human experiences, and combining it with effects of psychedelic compounds on neuronal pathways and neurochemical receptor sites, the authors are forging a new path for further inquiry.”

In an accompanying editorial, Daniel Barron, MD, PhD, medical director, Interventional Pain Psychiatry Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Richard Friedman, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, call the work “impressive” and “clever.”

“Psychedelics paired with new applications of computational tools might help bypass the imprecision of psychiatric diagnosis and connect measures of behavior to specific physiologic targets,” they write.

The research was supported by the Brain Canada Foundation, through the Canada Brain Research Fund, a grant from the NIH grant, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Bzdok was also supported by the Healthy Brains Healthy Lives initiative (Canada First Research Excellence fund) and the CIFAR Artificial Intelligence Chairs program (Canada Institute for Advanced Research), as well as Research Award and Teaching Award by Google. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. No disclosures were listed for Dr. Barron and Dr. Friedman. Dr. Aaronson’s research is supported by Compass Pathways.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Pre-death grief’ is a real, but overlooked, syndrome

When an individual develops a terminal illness, those closest to them often start to grieve long before the person dies. Although a common syndrome, it often goes unrecognized and unaddressed.

A new review proposes a way of defining this specific type of grief in the hope that better, more precise descriptive categories will inform therapeutic interventions to help those facing a life-changing loss.

, lead author Jonathan Singer, PhD, visiting assistant professor of clinical psychology, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, told this news organization.

“We proposed the overarching term ‘pre-death grief,’ with the two separate constructs under pre-death grief – anticipatory grief [AG] and illness-related grief [IRG],” he said. “These definitions provide the field with uniform constructs to advance the study of grief before the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness.

“Research examining grief experienced by family members prior to an individual’s death to a life-limiting illness revealed wide variation in the terminology used and characterization of such grief across studies,”

The study was published online Feb. 23 in Palliative Medicine.

‘Typical’ versus ‘impairing’ grief

“Most deaths worldwide are attributed to a chronic or life-limiting Illness,” the authors write. The experience of grief before the loss of a family member “has been studied frequently, but there have been conceptualization issues, which is problematic, as it hinders the potential advancement of the field in differentiating typical grief from more impairing grief before the death,” Dr. Singer said. “Further complicating the picture is the sheer number of terms used to describe grief before death.”

Dr. Singer said that when he started conducting research in this field, he “realized someone had to combine the articles that have been published in order to create definitions that will advance the field, so risk and protective factors could be identified and interventions could be tested.”

For the current study, the investigators searched six databases to find research that “evaluated family members’ or friends’ grief related to an individual currently living with a life-limiting illness.” They excluded studies that evaluated grief after death.

Of 9,568 records reviewed, the researchers selected 134 full-text articles that met inclusion criteria. Most studies (57.46%) were quantitative; 23.88% were qualitative, and 17.91% used mixed methods. Most studies were retrospective, although 14.93% were prospective, and 3% included both prospective and retrospective analyses.

Most participants reported that the family member/friend was diagnosed either with “late-stage dementia” or “advanced cancer.” The majority (58%) were adult children of the individual with the illness, followed by spouses/partners (28.1%) and other relatives/friends (13.9%) in studies that reported the relationship to the participant and the person with the illness.

Various scales were used in the studies to measure grief, particularly the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory (n = 28), the Anticipatory Grief Scale (n = 18), and the Prolonged Grief–12 (n = 13).

A new name

Owing to the large number of articles included in the review, the researchers limited the analysis to those in which a given term was used in ≥ 1 articles.

The researchers found 18 different terms used by family members/friends of individuals with life-limiting illness to describe grief, including AG (used in the most studies, n = 54); pre-death grief (n = 18), grief (n = 12), pre-loss grief (n = 6), caregiver grief (n = 5), and anticipatory mourning (n = 4). These 18 terms were associated with greater than or equal to 30 different definitions across all of the various studies.

“Definitions of these terms differed drastically,” and many studies used the term AG without defining it.

Nineteen studies used multiple terms within a single article, and the terms were “used interchangeably, with the same definition applied,” the researchers report.

For example, one study defined AG as “the process associated with grieving the eventual loss of a family member in advance of their inevitable death,” while another defined AG as “a series of losses based on a loved one’s progression of cognitive and physical decline.”

On the basis of this analysis, the researchers chose the term “pre-death grief,” which encompasses IRG and AG.

Dr. Singer explained that IRG is “present-oriented” and involves the “longing and yearning for the family member to be as they were before the illness.” AG is “future oriented” and is defined as “family members’ grief experience while the person with the life-limiting illness is alive but that is focused on feared or anticipated losses that will occur after the person’s death.”

The study was intended “to advance the field and provide the knowledge and definitions in order to create and test an evidence-based intervention,” Dr. Singer said.

He pointed to interventions (for example: behavioral activation, meaning-centered grief therapy) that could be tested to reduce pre-death grief or specific interventions that focus on addressing IRG or AG. “For example, cognitive behavior therapy might be used to challenge worry about life without the person, which would be classified as AG.”

Dr. Singer feels it is “vital” to reduce pre-death grief, insofar as numerous studies have shown that high rates of pre-death grief “result in higher rates of prolonged grief disorder.”

‘Paradoxical reality’

Francesca Falzarano, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, called the article a “timely piece drawing much-needed attention to an all-too-often overlooked experience lived by those affected by terminal illnesses.”

Dr. Falzarano, who was not involved in the review, said that “from her own experience” as both a caregiver and behavioral scientist conducting research in this area, the concept of pre-death grief is a paradoxical reality – “how do we grieve someone we haven’t lost yet?”

The experience of pre-death grief is “quite distinct from grief after bereavement” because there is no end date. Rather, the person “cycles back and forth between preparing themselves for an impending death while also attending to whatever is happening in the current moment.” It’s also “unique in that both patients and caregivers individually and collectively grieve losses over the course of the illness,” she noted.

“We as researchers absolutely need to focus our attention on achieving consensus on an appropriate definition for pre-death grief that adequately encompasses its complexity and multidimensionality,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Falzarano report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When an individual develops a terminal illness, those closest to them often start to grieve long before the person dies. Although a common syndrome, it often goes unrecognized and unaddressed.

A new review proposes a way of defining this specific type of grief in the hope that better, more precise descriptive categories will inform therapeutic interventions to help those facing a life-changing loss.

, lead author Jonathan Singer, PhD, visiting assistant professor of clinical psychology, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, told this news organization.

“We proposed the overarching term ‘pre-death grief,’ with the two separate constructs under pre-death grief – anticipatory grief [AG] and illness-related grief [IRG],” he said. “These definitions provide the field with uniform constructs to advance the study of grief before the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness.

“Research examining grief experienced by family members prior to an individual’s death to a life-limiting illness revealed wide variation in the terminology used and characterization of such grief across studies,”

The study was published online Feb. 23 in Palliative Medicine.

‘Typical’ versus ‘impairing’ grief

“Most deaths worldwide are attributed to a chronic or life-limiting Illness,” the authors write. The experience of grief before the loss of a family member “has been studied frequently, but there have been conceptualization issues, which is problematic, as it hinders the potential advancement of the field in differentiating typical grief from more impairing grief before the death,” Dr. Singer said. “Further complicating the picture is the sheer number of terms used to describe grief before death.”

Dr. Singer said that when he started conducting research in this field, he “realized someone had to combine the articles that have been published in order to create definitions that will advance the field, so risk and protective factors could be identified and interventions could be tested.”

For the current study, the investigators searched six databases to find research that “evaluated family members’ or friends’ grief related to an individual currently living with a life-limiting illness.” They excluded studies that evaluated grief after death.

Of 9,568 records reviewed, the researchers selected 134 full-text articles that met inclusion criteria. Most studies (57.46%) were quantitative; 23.88% were qualitative, and 17.91% used mixed methods. Most studies were retrospective, although 14.93% were prospective, and 3% included both prospective and retrospective analyses.

Most participants reported that the family member/friend was diagnosed either with “late-stage dementia” or “advanced cancer.” The majority (58%) were adult children of the individual with the illness, followed by spouses/partners (28.1%) and other relatives/friends (13.9%) in studies that reported the relationship to the participant and the person with the illness.

Various scales were used in the studies to measure grief, particularly the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory (n = 28), the Anticipatory Grief Scale (n = 18), and the Prolonged Grief–12 (n = 13).

A new name

Owing to the large number of articles included in the review, the researchers limited the analysis to those in which a given term was used in ≥ 1 articles.

The researchers found 18 different terms used by family members/friends of individuals with life-limiting illness to describe grief, including AG (used in the most studies, n = 54); pre-death grief (n = 18), grief (n = 12), pre-loss grief (n = 6), caregiver grief (n = 5), and anticipatory mourning (n = 4). These 18 terms were associated with greater than or equal to 30 different definitions across all of the various studies.

“Definitions of these terms differed drastically,” and many studies used the term AG without defining it.

Nineteen studies used multiple terms within a single article, and the terms were “used interchangeably, with the same definition applied,” the researchers report.

For example, one study defined AG as “the process associated with grieving the eventual loss of a family member in advance of their inevitable death,” while another defined AG as “a series of losses based on a loved one’s progression of cognitive and physical decline.”

On the basis of this analysis, the researchers chose the term “pre-death grief,” which encompasses IRG and AG.

Dr. Singer explained that IRG is “present-oriented” and involves the “longing and yearning for the family member to be as they were before the illness.” AG is “future oriented” and is defined as “family members’ grief experience while the person with the life-limiting illness is alive but that is focused on feared or anticipated losses that will occur after the person’s death.”

The study was intended “to advance the field and provide the knowledge and definitions in order to create and test an evidence-based intervention,” Dr. Singer said.

He pointed to interventions (for example: behavioral activation, meaning-centered grief therapy) that could be tested to reduce pre-death grief or specific interventions that focus on addressing IRG or AG. “For example, cognitive behavior therapy might be used to challenge worry about life without the person, which would be classified as AG.”

Dr. Singer feels it is “vital” to reduce pre-death grief, insofar as numerous studies have shown that high rates of pre-death grief “result in higher rates of prolonged grief disorder.”

‘Paradoxical reality’

Francesca Falzarano, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, called the article a “timely piece drawing much-needed attention to an all-too-often overlooked experience lived by those affected by terminal illnesses.”

Dr. Falzarano, who was not involved in the review, said that “from her own experience” as both a caregiver and behavioral scientist conducting research in this area, the concept of pre-death grief is a paradoxical reality – “how do we grieve someone we haven’t lost yet?”