User login

Brain imaging gives new insight into hoarding disorder

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intranasal oxytocin shows early promise for cocaine dependence

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intranasal oxytocin (INOT) is showing early promise as a treatment for cocaine dependence, new research suggests.

Results of a small 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with cocaine use disorder showed a high level of abstinence in those who received INOT beginning 2 weeks after treatment initiation.

“In this population of cocaine-dependent individuals in a community clinic setting, , compared to placebo,” lead author Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, a Teaneck, N.J.–based psychiatrist, said in an interview.

On the other hand, “the findings were paradoxical because there was a greater dropout rate in the intranasal oxytocin group after week 1, suggesting that oxytocin might have a biphasic effect, which should be addressed in future studies,” added Dr. Raby, who was an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, division on substance abuse, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, when the trial was conducted.

The study was published in the March issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports.

‘Crying need’

“Focus on stress reactivity in addiction and on the loss of social norms among drug users has generated interest in oxytocin, due to its purported role in these traits and regulation of stress,” the authors wrote.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that regulates autonomic functions. Previous research in cannabis users suggests it may have a role in treating addiction by reportedly reducing cravings. In addition, earlier research also suggests it cuts stress reactivity and state anger in cocaine users.

A previous trial of INOT showed it decreased cocaine craving, and additional research has revealed recurrent cocaine use results in lower endogenous oxytocin levels and depleted oxytocin in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

“The bias of my work is to look for simple, nonaddictive medicinal approaches that can be used in the community settings, because that’s where the greatest crying need lies and where most problems from drug addiction occur,” said Dr. Raby.

“There has been long-standing interest in how the brain adaptive systems, or so-called ‘stress systems,’ adjust in the face of drug dependence in general, and the main focus of the study has been to understand this response and use the insight from these adaptations to develop medicinal treatments for drug abuse, particularly cocaine dependence,” he added.

To investigate the potential for INOT to promote abstinence from cocaine, the researchers randomized 26 patients with cocaine use disorder (73% male, mean [SD] age, 50.2 [5.4] years). Most participants had been using cocaine on a regular basis for about 25 years, and baseline average days of cocaine use was 11.1 (5.7) during the 30 days prior to study entry.

At a baseline, the researchers collected participants’ medical history and conducted a physical examination, urine toxicology, electrocardiogram, comprehensive metabolic panel, and complete blood count. They used the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview to confirm the diagnosis of cocaine dependence.

The study began with a 7-day inpatient abstinence induction stage, after which participants were randomized to receive either INOT 24 IU or intranasal placebo (n = 15 and n = 11, respectively).

Patients attended the clinic three times per week. At each visit, they completed the cocaine craving scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Clinician Global Inventory (all self-reports), as well as the Time Line Follow Back (TLFB) to document cocaine use.

Participants were trained to self-administer an intranasal solution at home, with compliance monitored in two ways – staff observed self-administration of the randomized medication at the time of clinic visits and weighed the “at home bottle.”

Cocaine use was determined via urine toxicology and TLFB self-report.

Threshold period

INOT did not induce ≥ 3 weeks of continuous abstinence. However, beginning with week 3, the odds of weekly abstinence increased dramatically in the INOT group, from 4.61 (95% confidence interval,1.05, 20.3) to 15.0 (1.18, 190.2) by week 6 (t = 2.12, P = .037).

The overall medication group by time interaction across all 6 weeks was not significant (F1,69 = 1.73, P = .19); but when the interaction was removed, the difference between the overall effect of medication (INOT vs. placebo) over all 6 weeks “reached trend-level significance” (F1,70) = 3.42, P = .07).

The subjective rating outcomes (cravings, perceived stress, cocaine dependence, and depression) “did not show a significant medication group by time interaction effect,” the authors reported, although stress-induced cravings did tend toward a significant difference between the groups.

Half of the patients did not complete the full 6 weeks. Of those who discontinued, 85% came from the INOT group and 15% from the placebo group. Of the 11 who dropped out from the treatment group, seven were abstinent at the time of discontinuation for ≥ 1 week.

There were no significant differences in rates of reported side effects between the two groups.

“This study highlights some promise that perhaps there is a threshold period of time you need to cross, after which time oxytocin could really be really helpful as acute or maintenance medication,” said Dr. Raby. The short study duration might have been a disadvantage. “We might have seen better results if the study had been 8 or 12 weeks in duration.”

Using motivational approaches during the early phase – e.g., psychotherapy or a voucher system – might increase adherence, and then “after this initial lag, we might see a more therapeutic effect,” he suggested.

Dr. Raby noted that his group studied stress hormone secretions in the cocaine-dependent study participants during the 7-day induction period and that the findings, when published, could shed light on this latency period. “Cocaine dependence creates adaptations in the stress system,” he said.

‘Nice first step’

Commenting on the study, Jane Joseph, PhD, professor in the department of neurosciences and director of the neuroimaging division at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said it is “nice to see a clinical trial using oxytocin in cocaine dependence [because] preclinical research has shown fairly convincing effects of oxytocin in reducing craving or stress in the context of cocaine seeking, but findings are rather mixed in human studies.”

Dr. Joseph, who was not involved with the study, said her group’s research showed oxytocin to be the most helpful for men with cocaine use disorder who reported childhood trauma, while for women, oxytocin “seemed to worsen their reactivity to cocaine cues.”

She said the current study is a “nice first step” and suggested that future research should include larger sample sizes to “address some of the individual variability in the response to oxytocin by examining sex differences or trauma history.”

The study was supported by an award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Raby and coauthors and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DRUG AND ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE REPORTS

Dramatic increase in driving high after cannabis legislation

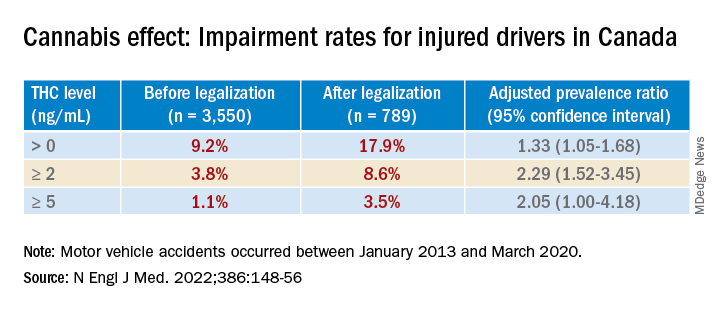

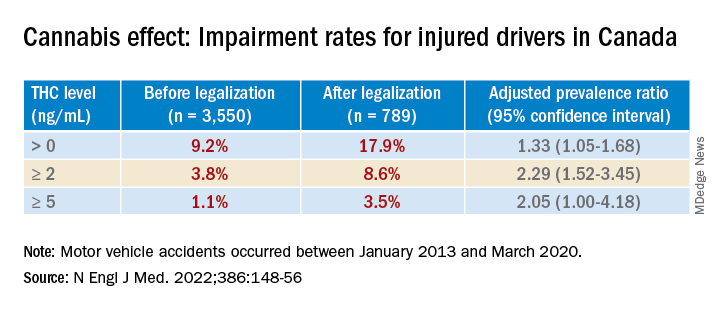

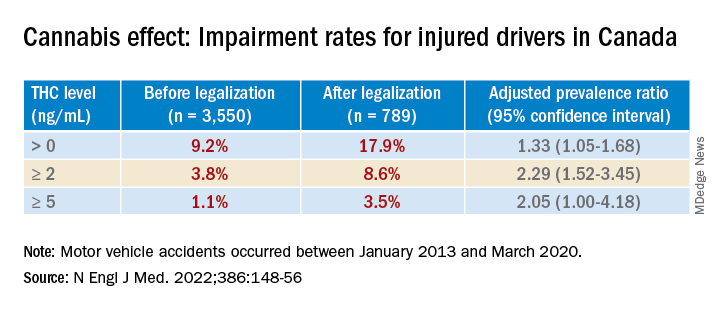

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Antidepressants: Is less more?

When it comes to antidepressant prescribing, less may be more, new research suggests.

A new review suggests antidepressants are overprescribed and that the efficacy of these agents is questionable, leading researchers to recommend that, when physicians prescribe these medications, it should be for shorter periods.

“Antidepressants have never been shown to have a clinically significant difference from placebo in the treatment of depression,” study co\investigator Mark Horowitz, GDPsych, PhD, division of psychiatry, University College London, said in an interview.

He added antidepressants “exert profound adverse effects on the body and brain” and can be difficult to stop because of physical dependence that occurs when the brain adapts to them.

“The best way to take people off these drugs is to do so gradually enough that the unpleasant effects are minimized and in a way that means the reductions in dose get smaller and smaller as the total dose gets lower,” Dr. Horowitz said.

However, at least one expert urged caution in interpreting the review’s findings.

“The reality is that millions of people do benefit from these medications, and this review minimizes those benefits,” Philip Muskin, MD, chief of consultation-liaison for psychiatry and professor of psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center and New York–Presbyterian Hospital, said when approached for comment.

The findings were published online Dec. 20, 2021, in the Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin.

Personal experience

Prescribing of newer-generation antidepressants, such as SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), is increasing, with an estimated one in six adults in the United Kingdom receiving at least one prescription in 2019-2020, the investigators noted.

Dr. Horowitz noted a personal motivation for conducting the review. “As well as being an academic psychiatrist, I’m also a patient who has been prescribed antidepressants since age 21, when my mood was poor, due to life circumstances.”

The antidepressant “didn’t have particularly helpful effects,” but Dr. Horowitz continued taking it for 18 years. “I was told it was helpful and internalized that message. I came to understand that much of the information around antidepressants came from the drug companies that manufactured them or from academics paid by these companies.”

Dr. Horowitz is currently discontinuing his medication – a tapering process now in its third year. He said he has come to realize, in retrospect, that symptoms not initially attributed to the drug, such as fatigue, impaired concentration, and impaired memory, have improved since reducing the medication.

“That experience sensitized me to look for these symptoms in my patients and I see them; but most of my patients were told by their doctors that the cause of those problems was the depression or anxiety itself and not the drug,” he said.

Dr. Horowitz collaborated with Michael Wilcock, DTB, Pharmacy, Royal Cornwall Hospitals, NHS Trust, Truro, England, in conducting the review “to provide an independent assessment of benefits and harms of antidepressants.”

“Much of the evidence of the efficacy of antidepressants comes from randomized placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Horowitz said. Several meta-analyses of these studies showed a difference of about two points between the agent and the placebo on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).

“Although this might be statistically significant, it does not meet the threshold for a clinical significance – those aren’t the same thing,” Dr. Horowitz said. Some analyses suggest that a “minimally clinically important difference” on the HAM-D would range from 3 to 6 points.

The findings in adolescents and children are “even less convincing,” the investigators noted, citing a Cochrane review.

“This is especially concerning because the number of children and adolescents being treated with antidepressants is rapidly increasing,” Dr. Horowitz said.

Additionally, the short duration of most trials, typically 6-12 weeks, is “largely uninformative for the clinical treatment of depression.”

Relapse or withdrawal?

The researchers reviewed the adverse effects of long-term antidepressant use, including daytime sleepiness, dry mouth, profuse sweating, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, restlessness, and feeling “foggy or detached.”

“Antidepressants have toxic effects on the brain and cause brain damage when they artificially increase serotonin and modify brain chemistry, which is why people become sick for years after stopping,” Dr. Horowitz said. “When the drug is reduced or stopped, the brain has difficulty dealing with the sudden drop in neurotransmitters, and withdrawal symptoms result, similar to stopping caffeine, nicotine, or opioids.”

He added it is not necessarily the original condition of depression or anxiety that is recurring but rather withdrawal, which can last for months or even years after medication discontinuation.

“Unfortunately, doctors have been taught that there are minimal withdrawal symptoms, euphemized as ‘discontinuation symptoms,’ and so when patients have reported withdrawal symptoms, they have been told it is a return of their underlying condition,” Dr. Horowitz said.

“This has led to many patients being incorrectly told that they need to get back on their antidepressants,” he added.

He likened this approach to “telling people that the need to continue smoking because when they stop, they get more anxiety.” Rather, the “correct response would be that they simply need to taper off the antidepressant more carefully,” he said.

Helpful in the short term

Patients should be informed prior to initiation of antidepressant treatment about the risk of withdrawal effects if they stop the drug, the investigators advise. They reference the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ updated guidance, which recommends slow tapering over a period long enough to mitigate withdrawal symptoms to “tolerable levels.”

The guidance suggests that patients start with a small “test reduction.” Withdrawal symptoms should be monitored for the following 2-4 weeks, using a symptom checklist such as the Discontinuation Emergent Signs and Symptoms Scale, with subsequent reductions based on the tolerability of the process.

Gradual dose reductions and very small final doses may necessitate the use of formulations of medication other than those commonly available in tablet forms, the researchers noted. During the tapering process, patients may benefit from increased psychosocial support.

Dr. Horowitz noted that antidepressants can be helpful on a short-term basis, and likened their use to the use of a cast to stabilize a broken arm.

“It’s useful for a short period. But if you leave someone in a plastic cast permanently, their arm will shrivel and you will disable them. These drugs should be prescribed minimally, and for the shortest possible period of time,” he said.

Dr. Horowitz recommended the recent draft National Institute for Health and Care Excellence depression guidance that recommends multiple other options beyond antidepressants, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem solving, counseling, and exercise.

Lack of balance

Dr. Muskin commented that the review is helpful in guiding clinicians on how to approach tapering of antidepressants and making patients aware of discontinuation symptoms.

However, “a lot of people will read this who need treatment, but they won’t get treated because they’ll take away the message that ‘drugs don’t work,’ ” he said.

“As it is, there is already stigma and prejudice toward psychiatric illness and using medications for treatment,” said Dr. Muskin, who was not involved with the research.

The current review “isn’t balanced, in terms of the efficacy of these drugs – both for the spectrum of depressive disorders and for panic or anxiety disorder. And there is nowhere that the authors say these drugs help people,” he added.

Moreover, the investigators’ assertion that long-term use of antidepressants causes harm is incorrect, he said.

“Yes, there are ongoing side effects that impose a burden, but that’s not the same as harm. And while the side effects are sometimes burdensome, ongoing depression is also terribly burdensome,” Dr. Muskin concluded.

Dr. Horowitz, Dr. Wilcock, and Dr. Muskin have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When it comes to antidepressant prescribing, less may be more, new research suggests.

A new review suggests antidepressants are overprescribed and that the efficacy of these agents is questionable, leading researchers to recommend that, when physicians prescribe these medications, it should be for shorter periods.

“Antidepressants have never been shown to have a clinically significant difference from placebo in the treatment of depression,” study co\investigator Mark Horowitz, GDPsych, PhD, division of psychiatry, University College London, said in an interview.

He added antidepressants “exert profound adverse effects on the body and brain” and can be difficult to stop because of physical dependence that occurs when the brain adapts to them.

“The best way to take people off these drugs is to do so gradually enough that the unpleasant effects are minimized and in a way that means the reductions in dose get smaller and smaller as the total dose gets lower,” Dr. Horowitz said.

However, at least one expert urged caution in interpreting the review’s findings.

“The reality is that millions of people do benefit from these medications, and this review minimizes those benefits,” Philip Muskin, MD, chief of consultation-liaison for psychiatry and professor of psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center and New York–Presbyterian Hospital, said when approached for comment.

The findings were published online Dec. 20, 2021, in the Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin.

Personal experience

Prescribing of newer-generation antidepressants, such as SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), is increasing, with an estimated one in six adults in the United Kingdom receiving at least one prescription in 2019-2020, the investigators noted.

Dr. Horowitz noted a personal motivation for conducting the review. “As well as being an academic psychiatrist, I’m also a patient who has been prescribed antidepressants since age 21, when my mood was poor, due to life circumstances.”

The antidepressant “didn’t have particularly helpful effects,” but Dr. Horowitz continued taking it for 18 years. “I was told it was helpful and internalized that message. I came to understand that much of the information around antidepressants came from the drug companies that manufactured them or from academics paid by these companies.”

Dr. Horowitz is currently discontinuing his medication – a tapering process now in its third year. He said he has come to realize, in retrospect, that symptoms not initially attributed to the drug, such as fatigue, impaired concentration, and impaired memory, have improved since reducing the medication.

“That experience sensitized me to look for these symptoms in my patients and I see them; but most of my patients were told by their doctors that the cause of those problems was the depression or anxiety itself and not the drug,” he said.

Dr. Horowitz collaborated with Michael Wilcock, DTB, Pharmacy, Royal Cornwall Hospitals, NHS Trust, Truro, England, in conducting the review “to provide an independent assessment of benefits and harms of antidepressants.”

“Much of the evidence of the efficacy of antidepressants comes from randomized placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Horowitz said. Several meta-analyses of these studies showed a difference of about two points between the agent and the placebo on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).

“Although this might be statistically significant, it does not meet the threshold for a clinical significance – those aren’t the same thing,” Dr. Horowitz said. Some analyses suggest that a “minimally clinically important difference” on the HAM-D would range from 3 to 6 points.

The findings in adolescents and children are “even less convincing,” the investigators noted, citing a Cochrane review.

“This is especially concerning because the number of children and adolescents being treated with antidepressants is rapidly increasing,” Dr. Horowitz said.

Additionally, the short duration of most trials, typically 6-12 weeks, is “largely uninformative for the clinical treatment of depression.”

Relapse or withdrawal?

The researchers reviewed the adverse effects of long-term antidepressant use, including daytime sleepiness, dry mouth, profuse sweating, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, restlessness, and feeling “foggy or detached.”

“Antidepressants have toxic effects on the brain and cause brain damage when they artificially increase serotonin and modify brain chemistry, which is why people become sick for years after stopping,” Dr. Horowitz said. “When the drug is reduced or stopped, the brain has difficulty dealing with the sudden drop in neurotransmitters, and withdrawal symptoms result, similar to stopping caffeine, nicotine, or opioids.”

He added it is not necessarily the original condition of depression or anxiety that is recurring but rather withdrawal, which can last for months or even years after medication discontinuation.

“Unfortunately, doctors have been taught that there are minimal withdrawal symptoms, euphemized as ‘discontinuation symptoms,’ and so when patients have reported withdrawal symptoms, they have been told it is a return of their underlying condition,” Dr. Horowitz said.

“This has led to many patients being incorrectly told that they need to get back on their antidepressants,” he added.

He likened this approach to “telling people that the need to continue smoking because when they stop, they get more anxiety.” Rather, the “correct response would be that they simply need to taper off the antidepressant more carefully,” he said.

Helpful in the short term

Patients should be informed prior to initiation of antidepressant treatment about the risk of withdrawal effects if they stop the drug, the investigators advise. They reference the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ updated guidance, which recommends slow tapering over a period long enough to mitigate withdrawal symptoms to “tolerable levels.”

The guidance suggests that patients start with a small “test reduction.” Withdrawal symptoms should be monitored for the following 2-4 weeks, using a symptom checklist such as the Discontinuation Emergent Signs and Symptoms Scale, with subsequent reductions based on the tolerability of the process.

Gradual dose reductions and very small final doses may necessitate the use of formulations of medication other than those commonly available in tablet forms, the researchers noted. During the tapering process, patients may benefit from increased psychosocial support.

Dr. Horowitz noted that antidepressants can be helpful on a short-term basis, and likened their use to the use of a cast to stabilize a broken arm.

“It’s useful for a short period. But if you leave someone in a plastic cast permanently, their arm will shrivel and you will disable them. These drugs should be prescribed minimally, and for the shortest possible period of time,” he said.

Dr. Horowitz recommended the recent draft National Institute for Health and Care Excellence depression guidance that recommends multiple other options beyond antidepressants, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem solving, counseling, and exercise.

Lack of balance

Dr. Muskin commented that the review is helpful in guiding clinicians on how to approach tapering of antidepressants and making patients aware of discontinuation symptoms.