User login

Early RA remission more unstable in the presence of foot synovitis

Clinicians should consider escalating therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who have persistent foot synovitis regardless of disease activity status, Australian rheumatologists have suggested.

The advice comes after the team of doctors from several hospitals in Adelaide, South Australia, found that patients who were in remission according to disease activity (DA) standard measures but had foot synovitis were almost twice as likely to relapse, compared with patients in remission without foot synovitis.

These patients also were more likely to have worse long-term radiographic and functional outcomes, Dr. Mihir D. Wechalekar of Flinders University, Adelaide, and his colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2016. doi: 10.1002/acr.22887).

The research team assessed the disease activity in 266 patients attending the Early Arthritis Clinic at Royal Adelaide Hospital using the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and the simplified disease activity index (SDAI).

Patients also received yearly hand and foot radiographs and their quality of life was measured via the Medical Outcome Study Short–Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire.

Patients were treated initially with triple-DMARD therapy and were escalated to achieve DAS28(ESR) remission by increasing methotrexate or adding a further DMARD or biologic DMARD according to a predefined treatment algorithm.

The researchers discovered that DA scores captured less than 50% of the variation in foot swollen joint count/tender joint count scores, “indicating that assessment of disease activity using these criteria is likely to be insufficient for detecting disease flares in the feet.”

Furthermore, the authors noted that despite the SDAI and CDAI being considered “more stringent” remission criteria, 24% of patients in SDAI remission and 25% of patients in CDAI remission had ongoing foot synovitis.

The sustainability of remission influenced the progression of erosion scores (P = .006); foot synovitis was linked to worse SF-36 physical functioning (P = 0.025).

“Our findings emphasize the importance of examining the ankle and foot as a part of the routine management of patients with RA,” the research team concluded.

“Given the impact of foot synovitis on stability of remission, radiological progression, and independent impact on quality of life, decisions should not be made solely on the basis of DA scores that omit foot joints,” they wrote.

“Presence of foot synovitis despite apparent remission should prompt escalation of therapy to prevent long-term joint damage and improve functional outcomes,” they added.

Clinicians should consider escalating therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who have persistent foot synovitis regardless of disease activity status, Australian rheumatologists have suggested.

The advice comes after the team of doctors from several hospitals in Adelaide, South Australia, found that patients who were in remission according to disease activity (DA) standard measures but had foot synovitis were almost twice as likely to relapse, compared with patients in remission without foot synovitis.

These patients also were more likely to have worse long-term radiographic and functional outcomes, Dr. Mihir D. Wechalekar of Flinders University, Adelaide, and his colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2016. doi: 10.1002/acr.22887).

The research team assessed the disease activity in 266 patients attending the Early Arthritis Clinic at Royal Adelaide Hospital using the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and the simplified disease activity index (SDAI).

Patients also received yearly hand and foot radiographs and their quality of life was measured via the Medical Outcome Study Short–Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire.

Patients were treated initially with triple-DMARD therapy and were escalated to achieve DAS28(ESR) remission by increasing methotrexate or adding a further DMARD or biologic DMARD according to a predefined treatment algorithm.

The researchers discovered that DA scores captured less than 50% of the variation in foot swollen joint count/tender joint count scores, “indicating that assessment of disease activity using these criteria is likely to be insufficient for detecting disease flares in the feet.”

Furthermore, the authors noted that despite the SDAI and CDAI being considered “more stringent” remission criteria, 24% of patients in SDAI remission and 25% of patients in CDAI remission had ongoing foot synovitis.

The sustainability of remission influenced the progression of erosion scores (P = .006); foot synovitis was linked to worse SF-36 physical functioning (P = 0.025).

“Our findings emphasize the importance of examining the ankle and foot as a part of the routine management of patients with RA,” the research team concluded.

“Given the impact of foot synovitis on stability of remission, radiological progression, and independent impact on quality of life, decisions should not be made solely on the basis of DA scores that omit foot joints,” they wrote.

“Presence of foot synovitis despite apparent remission should prompt escalation of therapy to prevent long-term joint damage and improve functional outcomes,” they added.

Clinicians should consider escalating therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who have persistent foot synovitis regardless of disease activity status, Australian rheumatologists have suggested.

The advice comes after the team of doctors from several hospitals in Adelaide, South Australia, found that patients who were in remission according to disease activity (DA) standard measures but had foot synovitis were almost twice as likely to relapse, compared with patients in remission without foot synovitis.

These patients also were more likely to have worse long-term radiographic and functional outcomes, Dr. Mihir D. Wechalekar of Flinders University, Adelaide, and his colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2016. doi: 10.1002/acr.22887).

The research team assessed the disease activity in 266 patients attending the Early Arthritis Clinic at Royal Adelaide Hospital using the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and the simplified disease activity index (SDAI).

Patients also received yearly hand and foot radiographs and their quality of life was measured via the Medical Outcome Study Short–Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire.

Patients were treated initially with triple-DMARD therapy and were escalated to achieve DAS28(ESR) remission by increasing methotrexate or adding a further DMARD or biologic DMARD according to a predefined treatment algorithm.

The researchers discovered that DA scores captured less than 50% of the variation in foot swollen joint count/tender joint count scores, “indicating that assessment of disease activity using these criteria is likely to be insufficient for detecting disease flares in the feet.”

Furthermore, the authors noted that despite the SDAI and CDAI being considered “more stringent” remission criteria, 24% of patients in SDAI remission and 25% of patients in CDAI remission had ongoing foot synovitis.

The sustainability of remission influenced the progression of erosion scores (P = .006); foot synovitis was linked to worse SF-36 physical functioning (P = 0.025).

“Our findings emphasize the importance of examining the ankle and foot as a part of the routine management of patients with RA,” the research team concluded.

“Given the impact of foot synovitis on stability of remission, radiological progression, and independent impact on quality of life, decisions should not be made solely on the basis of DA scores that omit foot joints,” they wrote.

“Presence of foot synovitis despite apparent remission should prompt escalation of therapy to prevent long-term joint damage and improve functional outcomes,” they added.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: The presence of foot synovitis despite apparent remission should prompt escalation of therapy to prevent long-term joint damage and improve functional outcomes.

Major finding: Patients who were in remission according to DA standard measures but had foot synovitis were almost twice as likely to relapse, compared with patients in remission without foot synovitis.

Data source: A study of 266 consecutive patients with early RA attending the Early Arthritis Clinic at Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Disclosures: The study was funded through a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia postgraduate scholarship.

Pushback on Part B drug payment proposal already beginning

Rheumatologists already are voicing concerns regarding a new proposal to test adjustments to how drugs administered in a physician’s office are paid for.

That proposal, published March 11 in the Federal Register, would test a change to the current reimbursement of average sales price plus 6% for Part B drugs with a lower add-on percentage of 2.5% plus $16.50.

In a fact sheet highlighting the proposals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said the change to a lower percentage plus a flat fee “will cover the cost of any drug paid under Medicare Part B.”

However, there are already questions about that.

“While this may seem the way in which CMS will control costs, they fail to recognize the cost to facilities in obtaining approval for these treatments, receiving and storing, and ultimately safely administering these therapies in an environment that provides the best outcomes for patients,” Dr. Norman B. Gaylis, a rheumatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla., said.

In fact, Dr. Gaylis adds that the focus on lowering drug expenses in the Part B space could have the unintended consequence of raising these expenses because it will force a change of venue.

“It has become so prohibitive that ultimately many patients will be referred to more expensive, less efficient outpatient facilities with, in fact, an increase in overall costs,” he said.

More than 300 provider and patient groups covering a range of specialties and including the American College of Rheumatology, the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations, and a number of state rheumatology organizations, are calling on Congress to ask CMS to withdraw the proposal.

In a March 17 letter to the majority and minority leaders in both chambers, the group is challenging the CMS assertion in the proposed rule that the current 6% add-on “may encourage the use of more expensive drugs because the 6% add-on generates more revenues for more expensive drugs.”

“This assumption fails to take into account the fact that providers’ prescribing decisions depend on a variety of factors, including clinical characteristics and the complex needs of the Medicare population,” the letter states. “Most importantly, there is no evidence indicating that the payment changes contemplated by the model will improve quality of care, and may adversely impact those patients that lose access to their most appropriate treatments.”

CMS offered two other pricing models that would be tested: indications-based pricing and reference pricing. The former would set payment rates based on the clinical effectiveness of a drug, while the latter would test the impact of setting a benchmark price for a group of drugs in a similar therapeutic class. Related to that is a proposal that CMS enter into voluntary risk-sharing agreements with drug manufacturers to link outcomes with price adjustments.

Dr. Gaylis suggested that CMS is going after the wrong party if cost containment is the ultimate goal here and should be focusing its efforts on the prices of the drugs themselves rather than how much they spend on physician reimbursement.

“Ironically, the major expense, i.e., the cost of drugs themselves, continues to spiral in the absence of any legitimate mechanism between CMS and pharma to contract prices that could save health care billions of dollars,” he said. “Ultimately, in my opinion, the solution rests in creating a fair and equal price for facilities administering these therapies and creating a pass-through where the drugs are not part of the physician’s risk, cost, or benefit and all payers, including CMS, can negotiate drug costs directly with the manufacturer.”

As part of the proposed rule, CMS also is considering creating feedback and decision-support tools to help, such as offering best practices for prescribing certain medications or providing feedback on prescribing patterns relative to local, regional, and national trends.

On the patient side, CMS is proposing to eliminate any patient cost sharing for office-administered drugs.

Comments on the proposals are due May 9.

Rheumatologists already are voicing concerns regarding a new proposal to test adjustments to how drugs administered in a physician’s office are paid for.

That proposal, published March 11 in the Federal Register, would test a change to the current reimbursement of average sales price plus 6% for Part B drugs with a lower add-on percentage of 2.5% plus $16.50.

In a fact sheet highlighting the proposals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said the change to a lower percentage plus a flat fee “will cover the cost of any drug paid under Medicare Part B.”

However, there are already questions about that.

“While this may seem the way in which CMS will control costs, they fail to recognize the cost to facilities in obtaining approval for these treatments, receiving and storing, and ultimately safely administering these therapies in an environment that provides the best outcomes for patients,” Dr. Norman B. Gaylis, a rheumatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla., said.

In fact, Dr. Gaylis adds that the focus on lowering drug expenses in the Part B space could have the unintended consequence of raising these expenses because it will force a change of venue.

“It has become so prohibitive that ultimately many patients will be referred to more expensive, less efficient outpatient facilities with, in fact, an increase in overall costs,” he said.

More than 300 provider and patient groups covering a range of specialties and including the American College of Rheumatology, the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations, and a number of state rheumatology organizations, are calling on Congress to ask CMS to withdraw the proposal.

In a March 17 letter to the majority and minority leaders in both chambers, the group is challenging the CMS assertion in the proposed rule that the current 6% add-on “may encourage the use of more expensive drugs because the 6% add-on generates more revenues for more expensive drugs.”

“This assumption fails to take into account the fact that providers’ prescribing decisions depend on a variety of factors, including clinical characteristics and the complex needs of the Medicare population,” the letter states. “Most importantly, there is no evidence indicating that the payment changes contemplated by the model will improve quality of care, and may adversely impact those patients that lose access to their most appropriate treatments.”

CMS offered two other pricing models that would be tested: indications-based pricing and reference pricing. The former would set payment rates based on the clinical effectiveness of a drug, while the latter would test the impact of setting a benchmark price for a group of drugs in a similar therapeutic class. Related to that is a proposal that CMS enter into voluntary risk-sharing agreements with drug manufacturers to link outcomes with price adjustments.

Dr. Gaylis suggested that CMS is going after the wrong party if cost containment is the ultimate goal here and should be focusing its efforts on the prices of the drugs themselves rather than how much they spend on physician reimbursement.

“Ironically, the major expense, i.e., the cost of drugs themselves, continues to spiral in the absence of any legitimate mechanism between CMS and pharma to contract prices that could save health care billions of dollars,” he said. “Ultimately, in my opinion, the solution rests in creating a fair and equal price for facilities administering these therapies and creating a pass-through where the drugs are not part of the physician’s risk, cost, or benefit and all payers, including CMS, can negotiate drug costs directly with the manufacturer.”

As part of the proposed rule, CMS also is considering creating feedback and decision-support tools to help, such as offering best practices for prescribing certain medications or providing feedback on prescribing patterns relative to local, regional, and national trends.

On the patient side, CMS is proposing to eliminate any patient cost sharing for office-administered drugs.

Comments on the proposals are due May 9.

Rheumatologists already are voicing concerns regarding a new proposal to test adjustments to how drugs administered in a physician’s office are paid for.

That proposal, published March 11 in the Federal Register, would test a change to the current reimbursement of average sales price plus 6% for Part B drugs with a lower add-on percentage of 2.5% plus $16.50.

In a fact sheet highlighting the proposals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said the change to a lower percentage plus a flat fee “will cover the cost of any drug paid under Medicare Part B.”

However, there are already questions about that.

“While this may seem the way in which CMS will control costs, they fail to recognize the cost to facilities in obtaining approval for these treatments, receiving and storing, and ultimately safely administering these therapies in an environment that provides the best outcomes for patients,” Dr. Norman B. Gaylis, a rheumatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla., said.

In fact, Dr. Gaylis adds that the focus on lowering drug expenses in the Part B space could have the unintended consequence of raising these expenses because it will force a change of venue.

“It has become so prohibitive that ultimately many patients will be referred to more expensive, less efficient outpatient facilities with, in fact, an increase in overall costs,” he said.

More than 300 provider and patient groups covering a range of specialties and including the American College of Rheumatology, the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations, and a number of state rheumatology organizations, are calling on Congress to ask CMS to withdraw the proposal.

In a March 17 letter to the majority and minority leaders in both chambers, the group is challenging the CMS assertion in the proposed rule that the current 6% add-on “may encourage the use of more expensive drugs because the 6% add-on generates more revenues for more expensive drugs.”

“This assumption fails to take into account the fact that providers’ prescribing decisions depend on a variety of factors, including clinical characteristics and the complex needs of the Medicare population,” the letter states. “Most importantly, there is no evidence indicating that the payment changes contemplated by the model will improve quality of care, and may adversely impact those patients that lose access to their most appropriate treatments.”

CMS offered two other pricing models that would be tested: indications-based pricing and reference pricing. The former would set payment rates based on the clinical effectiveness of a drug, while the latter would test the impact of setting a benchmark price for a group of drugs in a similar therapeutic class. Related to that is a proposal that CMS enter into voluntary risk-sharing agreements with drug manufacturers to link outcomes with price adjustments.

Dr. Gaylis suggested that CMS is going after the wrong party if cost containment is the ultimate goal here and should be focusing its efforts on the prices of the drugs themselves rather than how much they spend on physician reimbursement.

“Ironically, the major expense, i.e., the cost of drugs themselves, continues to spiral in the absence of any legitimate mechanism between CMS and pharma to contract prices that could save health care billions of dollars,” he said. “Ultimately, in my opinion, the solution rests in creating a fair and equal price for facilities administering these therapies and creating a pass-through where the drugs are not part of the physician’s risk, cost, or benefit and all payers, including CMS, can negotiate drug costs directly with the manufacturer.”

As part of the proposed rule, CMS also is considering creating feedback and decision-support tools to help, such as offering best practices for prescribing certain medications or providing feedback on prescribing patterns relative to local, regional, and national trends.

On the patient side, CMS is proposing to eliminate any patient cost sharing for office-administered drugs.

Comments on the proposals are due May 9.

Home infusion policies called out in ACR position statement

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

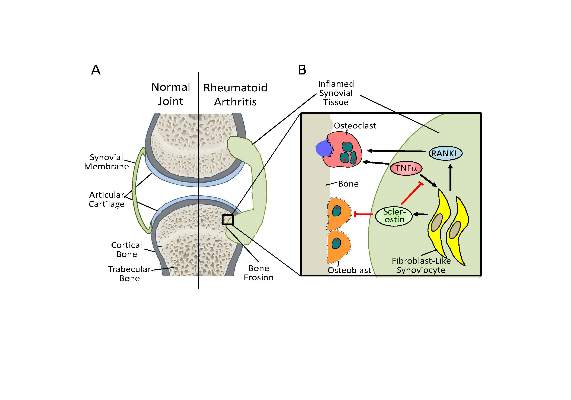

Antisclerostin osteoporosis drugs might worsen or unmask rheumatoid arthritis

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

ACR’s 2016-2020 research agenda built through consensus

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Analysis provides key questions – and answers – regarding future of JAK inhibitors for RA

MAUI, HAWAII – Now is a good time to assess the future of the Janus kinase inhibitor class of oral small-molecule medications for rheumatoid arthritis based on new evidence that addresses many of the key questions rheumatologists have about these agents, Dr. Roy Fleischmann said at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Baricitinib is likely to win Food and Drug Administration approval within a year, and would join tofacitinib (Xeljanz) as the second Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. A once-daily formulation of tofacitinib also was recently approved. Additional investigational agents, filgotinib and ABT-494, are headed for phase III testing, noted Dr. Fleischmann of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and co–medical director of the Metroplex Clinical Research Center, Dallas.

Here’s what rheumatologists want to know about the Janus associated kinase inhibitors, or Jakinibs:

Does Jakinib monotherapy look like a viable strategy?

Yes, according to Dr. Fleischmann, who pointed to the RA-BEGIN baricitinib trial and the DARWIN2 filgotinib trial, both presented at last fall’s American College of Rheumatology annual meeting in San Francisco.

Dr. Fleischmann presented the RA-BEGIN results at the American College of Rheumatology meeting. In this randomized trial conducted in methotrexate-naive rheumatoid arthritis patients, baricitinib 4 mg/day monotherapy outperformed methotrexate in terms of ACR response and demonstrated efficacy similar to baricitinib plus methotrexate, but with fewer side effects. Radiographic disease progression was significantly greater over 52 weeks with methotrexate than with baricitinib monotherapy, and significantly greater with baricitinib monotherapy than with combination therapy. However, baricitinib monotherapy was as effective as baricitinib in combination with methotrexate in slowing disease progression among patients who had elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein before treatment that normalized in response to therapy.

“So if baricitinib is approved and is available, I would use it as monotherapy initially and watch the C-reactive protein. If it drops to normal I’m fine, and if it doesn’t I’d add methotrexate for combination therapy,” according to the rheumatologist.

The randomized DARWIN2 trial included 283 methotrexate inadequate responders and showed that filgotinib is also effective as monotherapy.

“Tofacitinib, baricitinib, and filgotinib all work as monotherapy, and why shouldn’t they? There are no antibodies because these are small molecules,” Dr. Fleischmann commented.

A key safety finding in RA-BEAM, in his view, was that herpes zoster occurred in 1.4% of baricitinib-treated patients as well as in 1.2% of the adalimumab (Humira) arm.

“The message here, I think, is that we should be thinking about zoster in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” he said.

Is there a clinically meaningful efficacy difference between the Jakinibs?

Not so far, but as yet there have been no head-to-head trials.

How about in terms of safety?

“Safety may be the difference between these drugs. Efficacy doesn’t seem that different,” he said.

Based upon the clinical trials data to date, which involves hundreds of patients per Jakinib, it appears there is a hint of a difference, with less lymphopenia and anemia being seen with filgotinib, the most JAK 1–selective of the Jakinibs. Baricitinib is a JAK 1/2 inhibitor, tofacitinib a JAK 3/1/2 inhibitor, and ABT-494 is relatively JAK 1–selective. But definitive answers regarding comparative safety must await the creation of multi-thousand-patient postmarketing registries, in Dr. Fleischmann’s opinion.

Which is more effective: a Jakinib or a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor?

Only one clinical trial has addressed this question with sufficient power to yield a statistically significant answer. This was the RA-BEAM trial presented at the 2015 ACR meeting. RA-BEAM was a randomized head-to-head study of baricitinib plus methotrexate versus adalimumab plus methotrexate in 1,305 methotrexate inadequate responders. Baricitinib was the clear winner, with week 24 ACR 20 and ACR 50 responses of 70% and 45%, respectively, compared with 61% and 35% for adalimumab. Particularly impressive was baricitinib’s outperformance of adalimumab on the pain component of the ACR score.

“This is the first study to show a Jakinib plus methotrexate is actually superior to a TNF inhibitor plus methotrexate. And adalimumab is a really, really good drug. Is it a big difference? It’s not tremendous, but it’s a difference. Is it clinically significant? In that extra 9%-10% of patients, it obviously is; in most it’s probably not,” Dr. Fleischmann said.

Will an oral Jakinib be the first drug physicians prescribe in rheumatoid arthritis patients, or the last?

“The data so far shows that Jakinib monotherapy is very viable, as opposed to biologic monotherapy, which is viable but less so. RA-BEAM showed baricitinib was superior to a TNF inhibitor, and there are studies to suggest but don’t prove that tofacitinib is, too,” he said.

Dr. Fleischmann reported serving as a paid researcher for and/or consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including most of those developing Jakinibs.

MAUI, HAWAII – Now is a good time to assess the future of the Janus kinase inhibitor class of oral small-molecule medications for rheumatoid arthritis based on new evidence that addresses many of the key questions rheumatologists have about these agents, Dr. Roy Fleischmann said at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Baricitinib is likely to win Food and Drug Administration approval within a year, and would join tofacitinib (Xeljanz) as the second Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. A once-daily formulation of tofacitinib also was recently approved. Additional investigational agents, filgotinib and ABT-494, are headed for phase III testing, noted Dr. Fleischmann of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and co–medical director of the Metroplex Clinical Research Center, Dallas.

Here’s what rheumatologists want to know about the Janus associated kinase inhibitors, or Jakinibs:

Does Jakinib monotherapy look like a viable strategy?

Yes, according to Dr. Fleischmann, who pointed to the RA-BEGIN baricitinib trial and the DARWIN2 filgotinib trial, both presented at last fall’s American College of Rheumatology annual meeting in San Francisco.

Dr. Fleischmann presented the RA-BEGIN results at the American College of Rheumatology meeting. In this randomized trial conducted in methotrexate-naive rheumatoid arthritis patients, baricitinib 4 mg/day monotherapy outperformed methotrexate in terms of ACR response and demonstrated efficacy similar to baricitinib plus methotrexate, but with fewer side effects. Radiographic disease progression was significantly greater over 52 weeks with methotrexate than with baricitinib monotherapy, and significantly greater with baricitinib monotherapy than with combination therapy. However, baricitinib monotherapy was as effective as baricitinib in combination with methotrexate in slowing disease progression among patients who had elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein before treatment that normalized in response to therapy.

“So if baricitinib is approved and is available, I would use it as monotherapy initially and watch the C-reactive protein. If it drops to normal I’m fine, and if it doesn’t I’d add methotrexate for combination therapy,” according to the rheumatologist.

The randomized DARWIN2 trial included 283 methotrexate inadequate responders and showed that filgotinib is also effective as monotherapy.

“Tofacitinib, baricitinib, and filgotinib all work as monotherapy, and why shouldn’t they? There are no antibodies because these are small molecules,” Dr. Fleischmann commented.

A key safety finding in RA-BEAM, in his view, was that herpes zoster occurred in 1.4% of baricitinib-treated patients as well as in 1.2% of the adalimumab (Humira) arm.

“The message here, I think, is that we should be thinking about zoster in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” he said.

Is there a clinically meaningful efficacy difference between the Jakinibs?

Not so far, but as yet there have been no head-to-head trials.

How about in terms of safety?

“Safety may be the difference between these drugs. Efficacy doesn’t seem that different,” he said.

Based upon the clinical trials data to date, which involves hundreds of patients per Jakinib, it appears there is a hint of a difference, with less lymphopenia and anemia being seen with filgotinib, the most JAK 1–selective of the Jakinibs. Baricitinib is a JAK 1/2 inhibitor, tofacitinib a JAK 3/1/2 inhibitor, and ABT-494 is relatively JAK 1–selective. But definitive answers regarding comparative safety must await the creation of multi-thousand-patient postmarketing registries, in Dr. Fleischmann’s opinion.

Which is more effective: a Jakinib or a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor?

Only one clinical trial has addressed this question with sufficient power to yield a statistically significant answer. This was the RA-BEAM trial presented at the 2015 ACR meeting. RA-BEAM was a randomized head-to-head study of baricitinib plus methotrexate versus adalimumab plus methotrexate in 1,305 methotrexate inadequate responders. Baricitinib was the clear winner, with week 24 ACR 20 and ACR 50 responses of 70% and 45%, respectively, compared with 61% and 35% for adalimumab. Particularly impressive was baricitinib’s outperformance of adalimumab on the pain component of the ACR score.